CHAPTER 17 Diagnostic Tests for the Larynx and Pharynx

RADIOGRAPHY AND ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Radiographs of the pharynx and larynx should be evaluated in animals with suspected upper airway disease (Figs. 17-1 and 17-2). They are particularly useful in identifying radiodense foreign bodies such as needles, which can be embedded in tissues and may be difficult to find during laryngoscopy, and adjacent bony changes. Soft tissue masses and soft palate abnormalities may be seen, but apparent abnormal opacities are often misleading, particularly if there is any rotation of the head and neck, and overt abnormalities are often not identified. Abnormal soft tissue opacities or narrowing of the airway lumen identified radiographically must be confirmed with laryngoscopy or endoscopy and biopsy. Laryngeal paralysis cannot be detected radiographically.

FIG 17-1 Lateral radiograph of the neck, larynx, and pharynx showing normal anatomy. Note that the patient’s head and neck are not rotated. Excellent visualization of the soft palate and epiglottis are possible. Images obtained from poorly positioned patients often result in the appearance of “lesions” such as masses or abnormal soft palate because normal structures are captured at an oblique angle or are superimposed on one another.

A lateral view of the larynx, caudal nasopharynx, and cranial cervical trachea is usually obtained. The vertebral column interferes with airway evaluation on dorsoventral or ventrodorsal (VD) projections. In animals with abnormal opacities identified on the lateral view, a VD or oblique view may confirm the existence of the abnormality and allow further localization of it. When radiographs of the laryngeal area are obtained, the head is held with the neck slightly extended. Padding under the neck and around the head may be needed to avoid rotation. Radiodense foreign bodies are readily identified. Soft tissue masses that are within the airway or that distort the airway are apparent in some animals with neoplasia, granulomas, abscesses, or polyps, and elongated soft palate is sometimes detectable.

Ultrasonography provides another noninvasive imaging modality for evaluating the pharynx and larynx, and laryngeal motion can be assessed. Because air interferes with sound waves, accurate assessment of this area can be difficult. Nevertheless, ultrasonography was found to be useful in the diagnosis of laryngeal paralysis in dogs (Rudorf et al., 2001). Localization of mass lesions and guidance of needle aspiration can also be performed.

Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging can be performed in patients with mass lesions to better determine extent of disease.

LARYNGOSCOPY AND PHARYNGOSCOPY

Laryngoscopy and pharyngoscopy allow visualization of the larynx and pharynx for assessment of structural abnormalities and laryngeal function. The procedures are indicated in any dog or cat with clinical signs that suggest upper airway obstruction or laryngeal or pharyngeal disease. It should be noted that patients with increased respiratory efforts resulting from upper airway obstruction might have difficulty during recovery from anesthesia. For a period of time between removal of the endotracheal tube and full recovery of neuromuscular function, the patient may be unable to maintain an open airway. Therefore laryngoscopy should not be undertaken in these patients unless the clinician is prepared to perform whatever surgical treatments may be indicated during the same anesthetic period.

The animal is placed in sternal recumbency. Anesthesia is induced and maintained with a short-acting injectable agent without prior sedation. Propofol, sodium thiopental, or sodium thiamylal is commonly used. Depth of anesthesia is carefully titrated, with just enough drug administered to allow visualization of the laryngeal cartilages; some jaw tone is maintained, and spontaneous deep respirations occur. Gauze is passed under the maxilla behind the canine teeth, and the head is elevated by hand or by tying the gauze to a stand (Fig. 17-3). This positioning avoids external compression of the neck. Retraction of the tongue with a gauze sponge should allow visualization of the caudal pharynx and larynx. A laryngoscope is also helpful in illuminating this region and enhancing visualization.

FIG 17-3 Dog positioned with the head held off the table by gauze passed around the maxilla and hung from an intravenous pole. The tongue is pulled out, and a laryngoscope is used to visualize the pharyngeal anatomy and laryngeal motion.

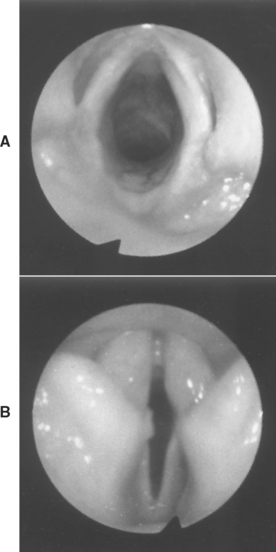

The motion of the arytenoid cartilages is evaluated while the patient takes several deep breaths. An assistant is needed to verbally report the onset of each inspiration and expiration by observing chest wall movements. Normally the arytenoid cartilages abduct symmetrically and widely with each inspiration and close on expiration (Fig. 17-4). Laryngeal paralysis resulting in clinical signs is usually bilateral. The cartilages are not abducted during inspiration. In fact, they may be passively forced outward during expiration and/or sucked inward during inspiration, resulting in paradoxical motion.

FIG 17-4 Canine larynx. A, During inspiration, arytenoid cartilages and vocal folds are abducted, resulting in wide symmetric opening to trachea. B, During expiration, cartilages and vocal folds nearly close the glottis.

If the patient fails to take deep breaths, doxapram hydrochloride (1.1-2.2mg/kg, administered intravenously) can be given to stimulate breathing. In a study by Tobias et al. (2004), none of the potential systemic side effects of the drug were noted, but some dogs required intubation when increased breathing efforts resulted in significant obstruction to airflow at the larynx.

If no laryngeal motion is observed, examination of the arytenoid cartilages should be continued as long as possible while the animal recovers from anesthesia. Effects of anesthesia and shallow breathing are the most common causes for an erroneous diagnosis of laryngeal paralysis.

After evaluation of laryngeal function, the plane of anesthesia is deepened and the caudal pharynx and larynx are thoroughly evaluated for structural abnormalities, foreign bodies, or mass lesions; appropriate diagnostic samples should be obtained for histopathologic analysis and perhaps culture. The length of the soft palate should be assessed. The soft palate normally extends to the tip of the epiglottis during inhalation. An elongated soft palate can contribute to signs of upper airway obstruction.

As described in Chapter 14, the caudal nasopharynx should be evaluated for nasopharyngeal polyps, mass lesions, and foreign bodies. Needles or other sharp objects may be buried in tissue, and careful visual examination and palpation are required for detection.

Neoplasia, granulomas, abscesses, or other masses can occur within or external to the larynx or pharynx, causing compression or deviation of normal structures or both. Severe, diffuse thickening of the laryngeal mucosa can be caused by infiltrative neoplasia or obstructive laryngitis. Biopsy specimens for histologic examination should be obtained from any lesions to establish an accurate diagnosis because the prognoses for these diseases are quite different. The normal diverse flora of the pharynx makes culture results difficult or impossible to interpret. Bacterial growth from abscess fluid or tissue obtained from granulomatous lesions may represent infection.

Obliteration of most of the airway lumen by surrounding mucosa is known as laryngeal collapse. With prolonged upper airway obstruction, the soft tissues are sucked into the lumen by the increased negative pressure created as the dog or cat struggles to get air into its lungs. Eversion of the laryngeal saccules, thickening and elongation of the soft palate, and inflammation with thickening of the pharyngeal mucosa can occur. The laryngeal cartilages can become soft and deformed, unable to support the soft tissues of the pharynx. It is unclear whether this chondromalacia is a concurrent or secondary component of laryngeal collapse. Collapse most often occurs in dogs with brachycephalic airway syndrome but can also occur with any chronic obstructive disorder.

The trachea should be examined radiographically or visually with an endoscope if abnormalities are not identified on laryngoscopy in the dog or cat with signs of upper airway obstruction. For these animals, the laryngeal cartilages can be held open with an endotracheal tube for a cursory examination of the proximal trachea at the time of laryngoscopy if an endoscope is not available.

Rudorf H, et al. The role of ultrasound in the assessment of laryngeal paralysis in the dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2001;42:338.

Tobias KM, et al. Effects of doxapram HCl on laryngeal function of normal dogs and dogs with naturally occurring laryngeal paralysis. Vet Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 2004;31:258.