Pelvis and Retroperitoneal Space

Pelvis and Retroperitoneal Situs

The pelvis (Pelvis) is designed to fulfil two purposes: On the one hand, it has to bear the weight of the viscera in humans exhibiting an erected posture. Hence, a solid, weight bearing, possibly bony floor would be reasonable at the caudal aspect of the abdominal cavity (Cavitas abdominalis). On the other hand, with regards to the elimination of products by the intestines and the kidneys, the act of procreation, and in particular childbirth, a rigid closure is not practical. The “constructive” compromise is the Diaphragma pelvis: a funnel-shaped group of muscles at the bottom of the pelvis, which is perforated in the midsagittal plane by the Urethra, the Rectum, and the Vagina in females.

To review the retroperitoneal situs of the abdomen – including the organs, which are not situated in the abdominal cavity, but at the dorsal wall – along with the pelvis, has a good (ontogenetic) reason. The kidneys, the major organs of the retroperitoneal space, initially originate from the pelvis and ascend to a level just inferior to the ribs. Conversely, the gonads, i.e. testicles (Testes) and ovaries (Ovaria), descend from the abdomen into the pelvis and in men even further down into the Scrotum. Thus, the subperitoneal (see below) connective tissue spaces of the pelvis and the retroperitoneal space form a continuum.

In order to gain insight into the regions addressed in the following, radical dissection steps are necessary to some extent: The small and large intestines have to be removed or at least mobilised so that they can be cleared from the posterior abdominal wall. Some dissectors even remove all organs of the epigastric region at once.

The View into the Pelvis

The so-called greater pelvis (Pelvis major, between the wings of the ilium) seems to be almost empty after the removal of the intestines. The psoas major muscle (M. psoas major) is accompanied by the Vasa iliaca externa and spans from the lumbar spine down to the inguinal region flanking the entrance to the lesser pelvis (Pelvis minor).

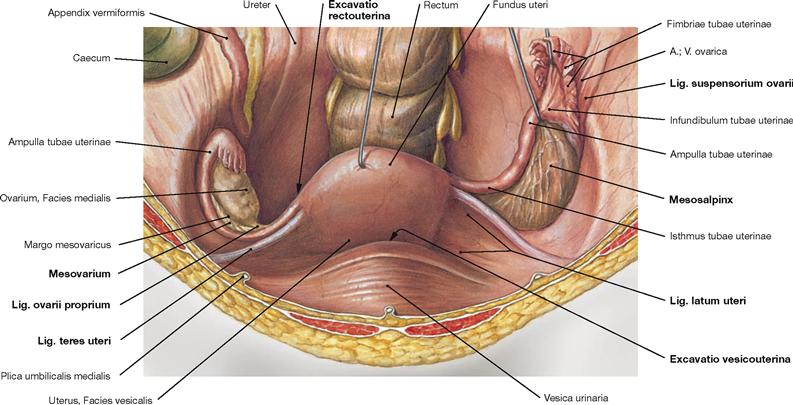

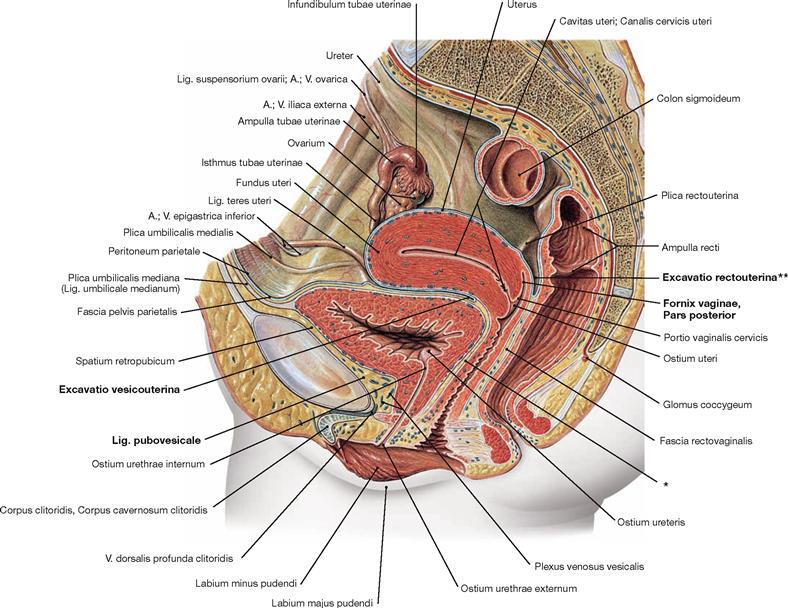

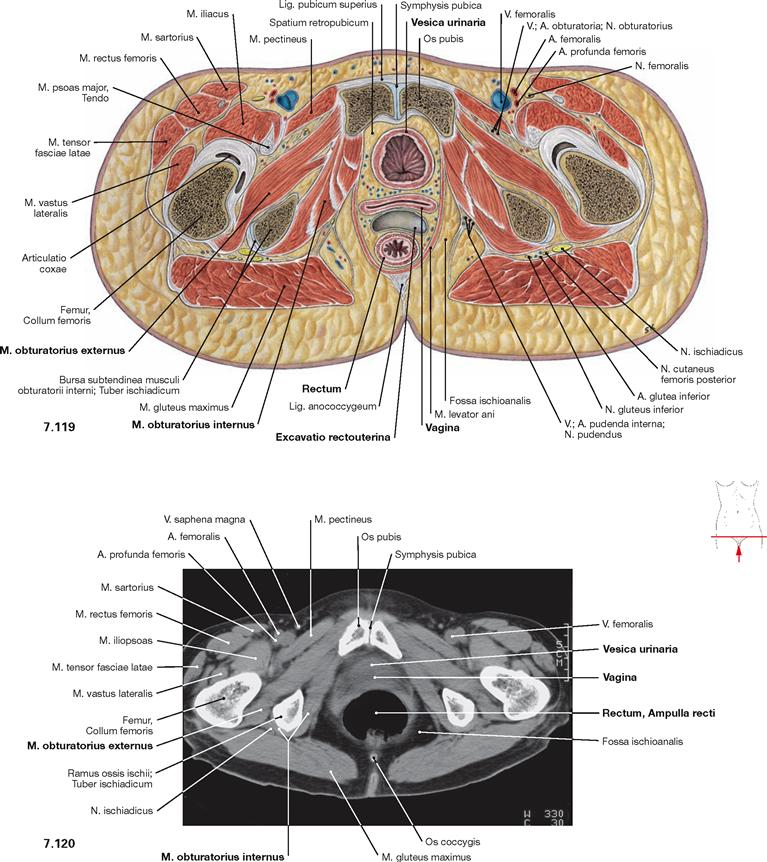

In contrast, the caudally narrowing funnel-shaped lesser pelvis is not vacant, especially in women. Ventrally, immediately behind the Symphysis pubica, lies the fundus of the urinary bladder (Vesica urinaria). In women, the Fundus of the Uterus is located immediately posterior to the urinary bladder. Bilaterally, two uterine (FALLOPIAN) tubes (Tubae uterinae) ascend from the Uterus towards the ovaries (Ovaria), which they embrace with their fimbriated projections. The ovaries are located bilaterally at the pelvic wall, just inferior to the boundary between the greater and the lesser pelvis. The rectum (Rectum) is positioned between the urinary bladder, the Uterus, and the dorsal pelvic wall (i.e. the sacrum), respectively.

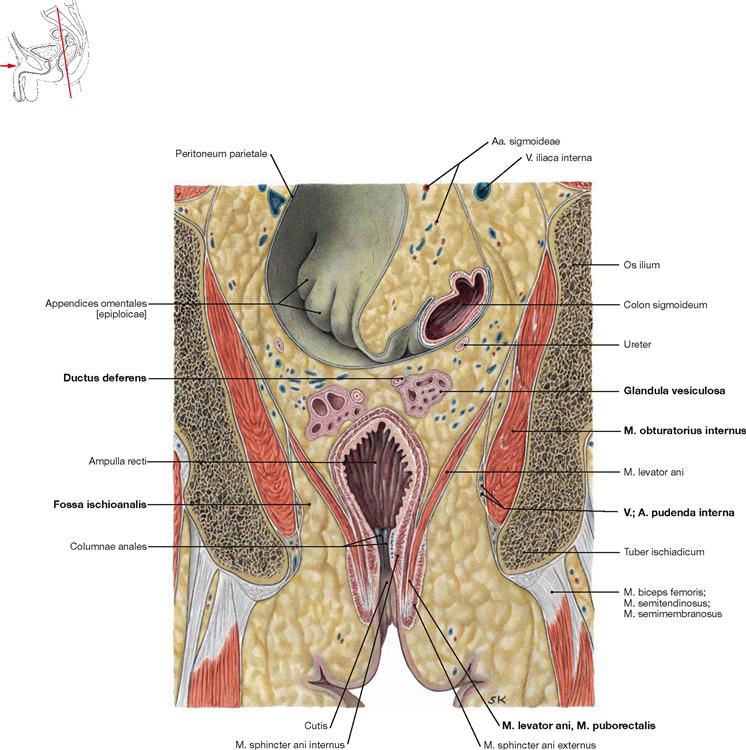

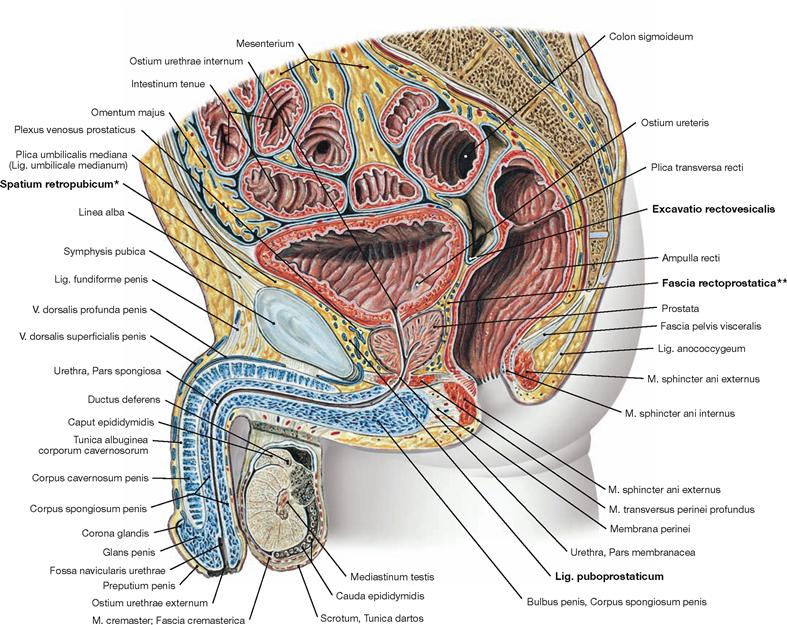

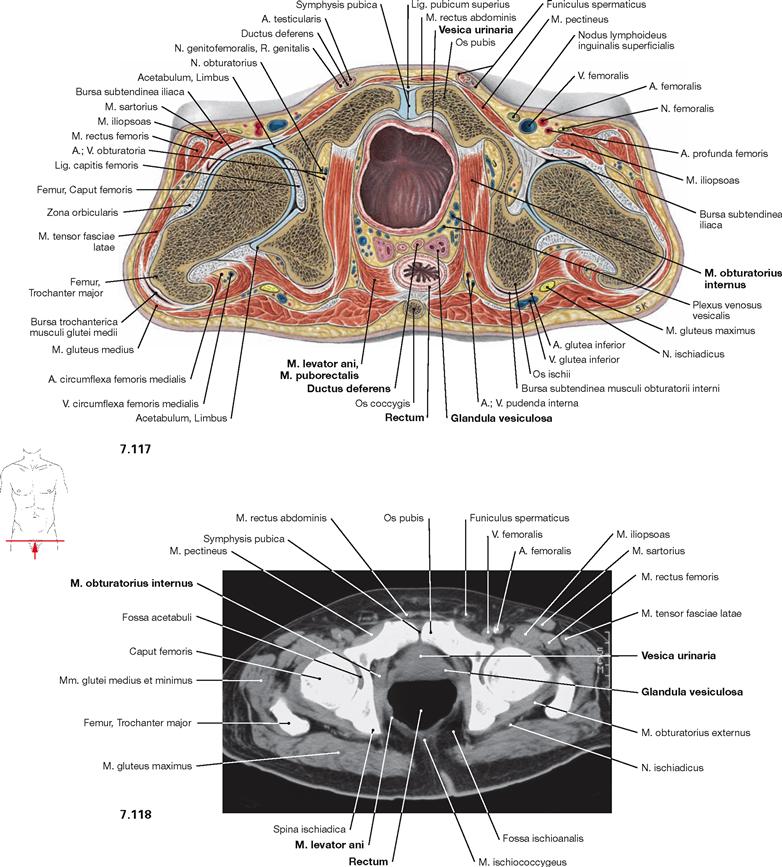

The body of the Uterus as well as the uterine tubes and the ovaries are located in separate peritoneal duplicatures/mesenteries (“Mesos”) in the abdominopelvic cavity (Cavitas peritonealis pelvis) which project at various depths towards the actual pelvic floor. In women, there is a particularly deep recess between the rear wall of the Uterus and the frontal wall of the Rectum, the Excavatio rectouterina. The fundus of the bladder and the upper portion of the Rectum are covered by peritoneum. Incising the peritoneum and dissecting the above-mentioned pelvic organs reveals the subperitoneal space of the pelvis (Spatium extraperitoneale pelvis). The lower parts of urinary bladder, Uterus, and Rectum are located within this connective tissue, as well as the female Vagina and the male accessory sex glands (in particular the

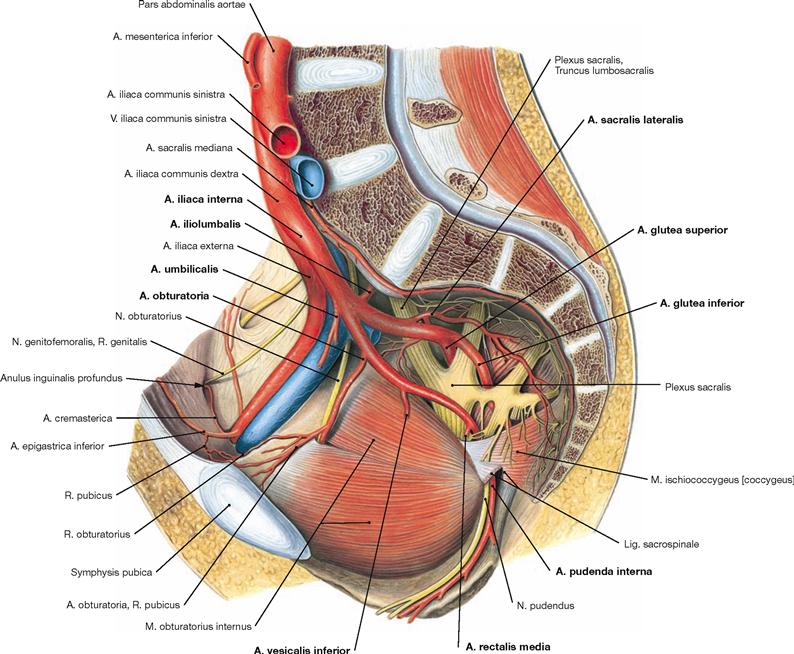

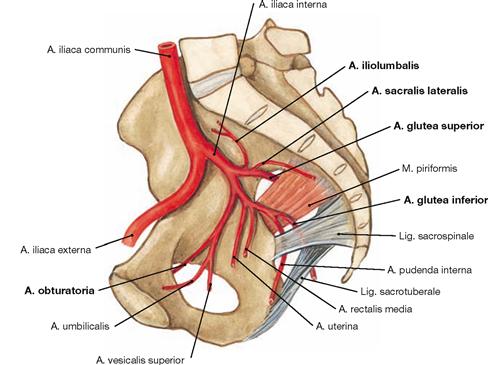

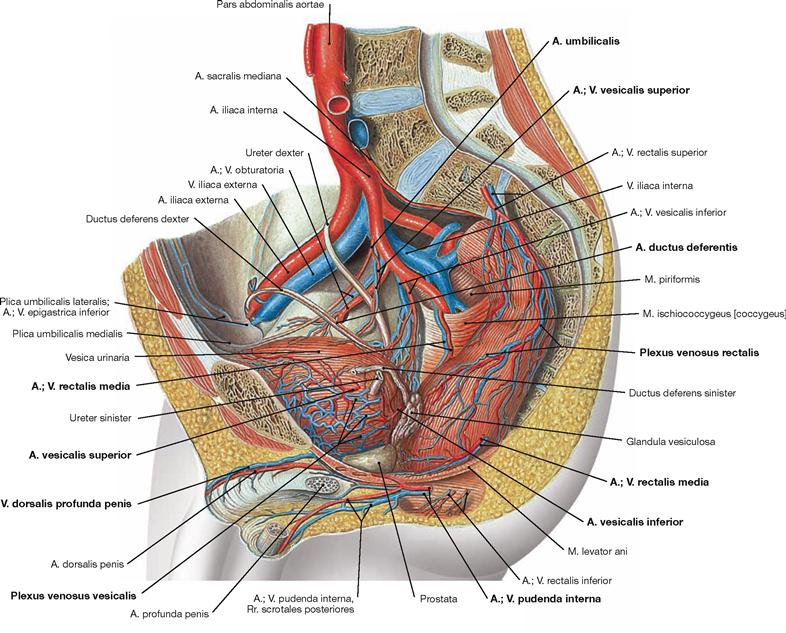

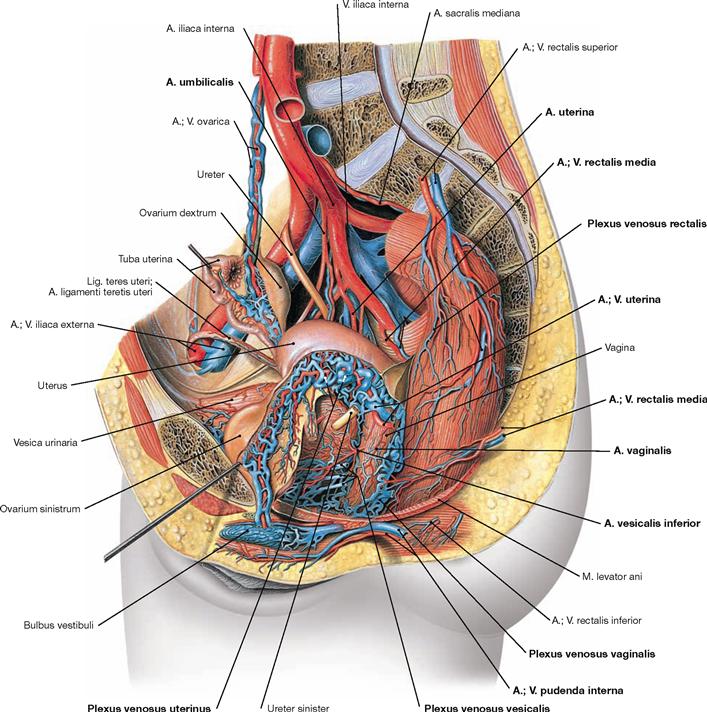

prostate gland [Prostata] and the seminal vesicles [Glandulae vesiculosae]), respectively. Branches of the A. iliaca interna and numerous nerves that supply the pelvic organs, but also the lower extremities, extend into this subperitoneal connective tissue.

Mobilisation of the blood vessels and organs exposes a muscular pelvic floor, the Diaphragma pelvis, which is perforated by the Urethra and Vagina (if present). It is like a deep, laterally compacted funnel. At the deepest point of the cone, the Rectum perforates the funnel. The M. levator ani is the muscle that forms a large part of the pelvic floor, and is able to (voluntarily!) raise and lower the Anus by a few centimetres.

Below the walls of the pelvic diaphragm, virtually in the “basement” of the pelvis, lies the perineal region (Regio perinealis): Tracing the urethra (Urethra) one reaches the anterior perineum, the urogenital triangle (Regio urogenitalis). The roots of the cavernous bodies of the Penis, which bears the male Urethra, originate in and protrude from this region. This region also encompasses the cavernous bodies of the Clitoris enclosing the opening of the short female Urethra. The posterior perineum, the anal triangle (Regio analis), is located below the pelvic diaphragm to the right or left side of the Rectum. It contains large, adipose-filled pits called Fossae ischioanales. They resemble cranially pointing pyramids with their bases directed caudally with respect to the Rectum. Major nerves and blood vessels are traceable in the Fossae ischioanales, supplying the organs of the perineal region (i.e. Penis, Clitoris, Labia majora and minora, Vestibulum vaginae, and Anus).

View of the Retroperitoneal Situs

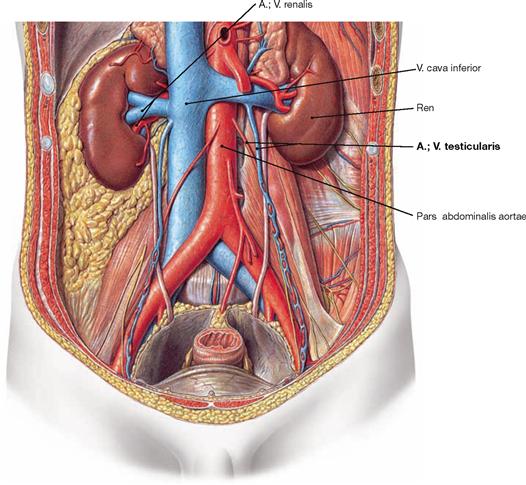

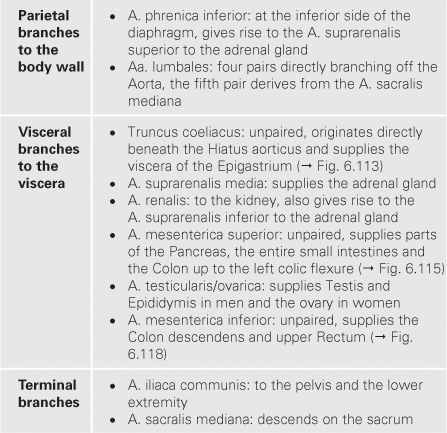

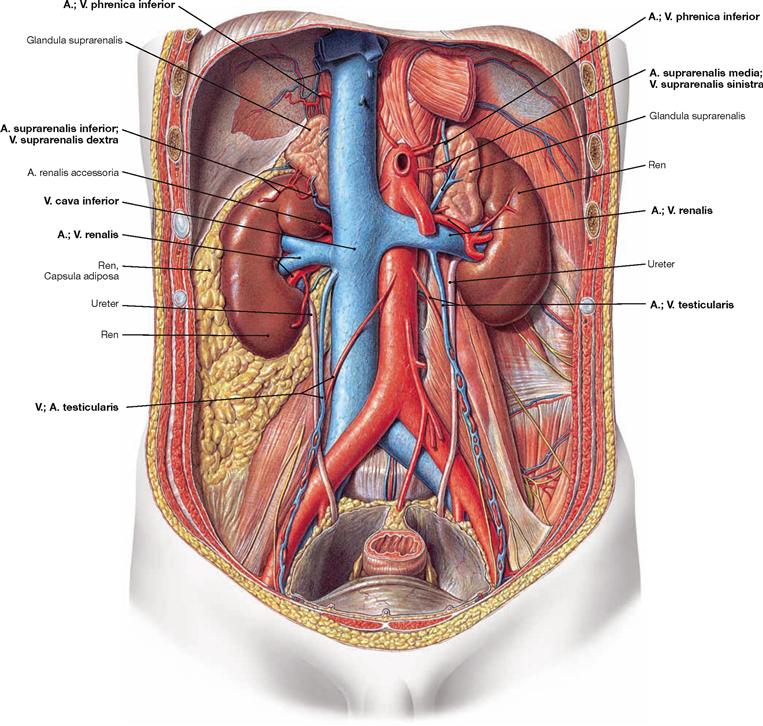

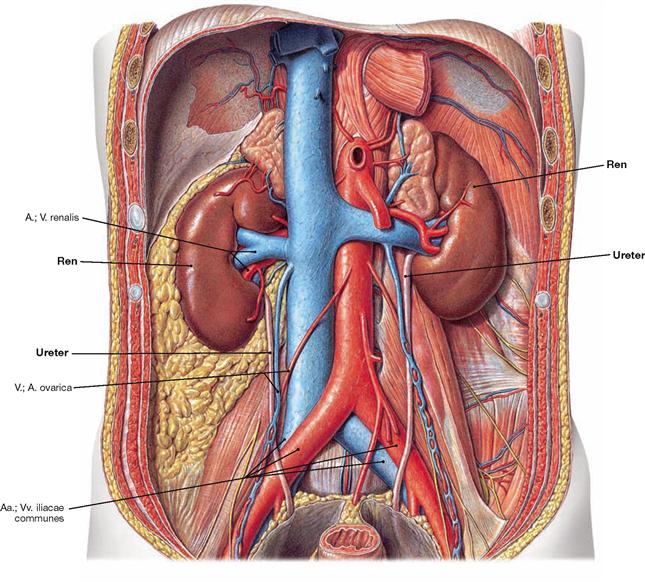

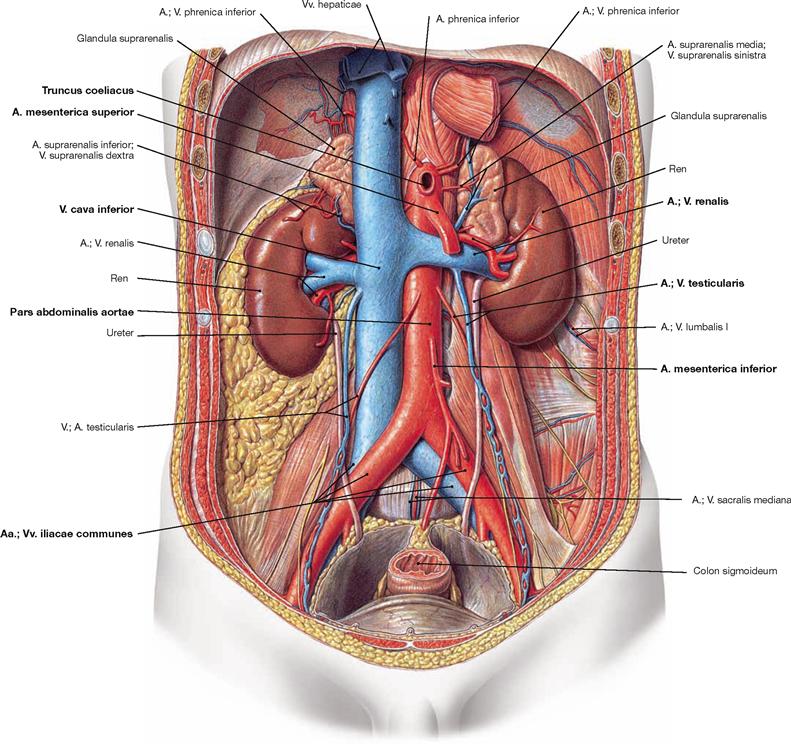

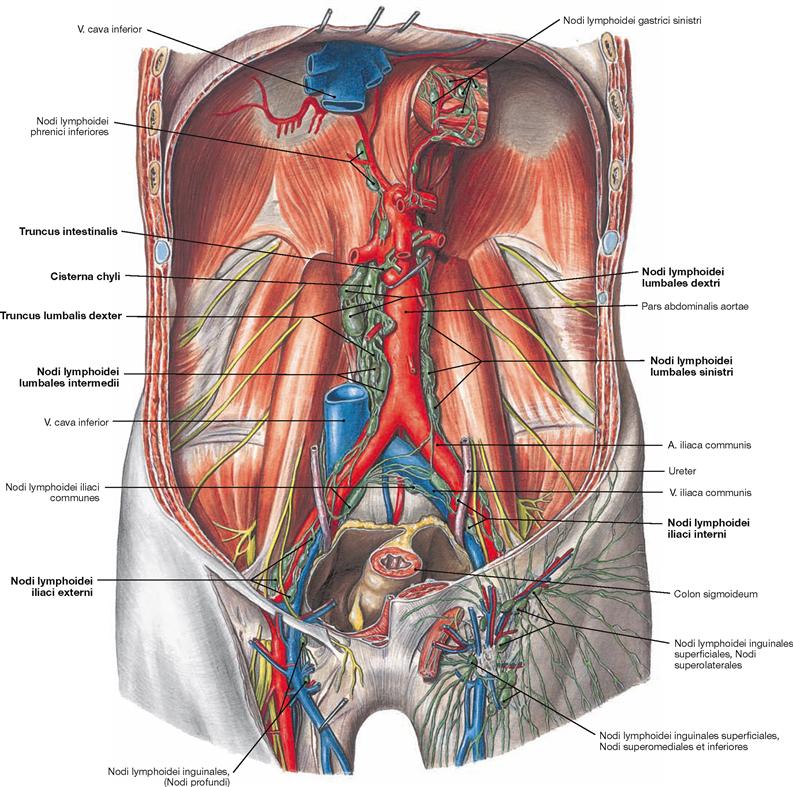

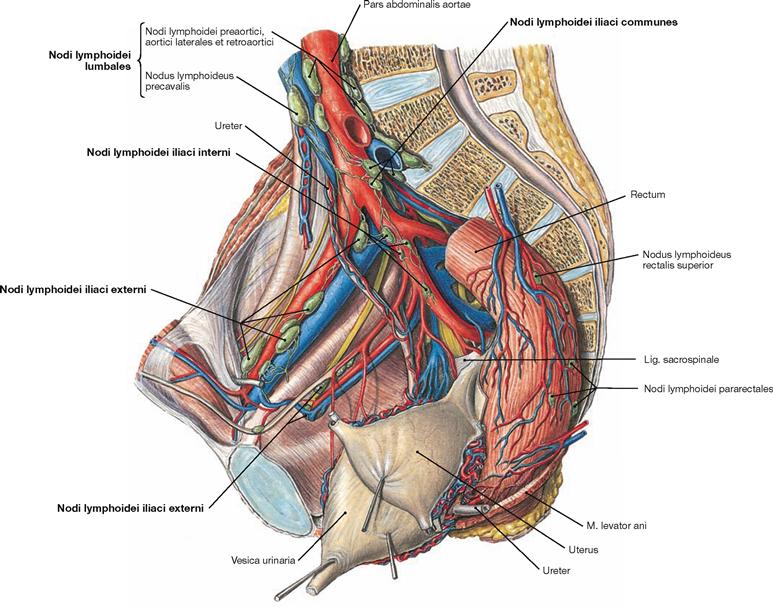

Removal of the parietal peritoneum and the underlying adipose tissue first reveals the inferior vena cava (V. cava inferior, slightly to the right side of the vertebral column) and the abdominal aorta (Aorta abdominalis, immediately to the left side). Both are reminiscent of an “upside-down Y”, bifurcating at the level of the lower lumbar vertebrae into the Aa. and Vv. iliacae communes, i.e. the iliac arteries and veins. The V. cava inferior has several tributaries; in the upper third especially the two renal veins (Vv. renales) and the short hepatic veins (Vv. hepaticae) are remarkable. The Aorta abdominalis has likewise many branches. The large vessels are densely covered with lymph nodes and lymph vessels that rise as paired Trunci lumbales from the pelvis. At the level of the branching renal vessels, the Trunci lumbales merge in the Cisterna chyli, which also receives the lymph of the intestines, to form the thoracic duct (Ductus thoracicus).

The kidneys (Renes) and the adrenal glands are located bilaterally in a perirenal fat capsule (Capsula adiposa) just below the diaphragmatic dome. Dorsal to the upper pole of each kidney lies rib XII. Medially, the Vasa renalia enter the kidneys at the hilum. The Ureter exits at the hilum descending into the pelvis along with the vessels of the gonads. The vessels of the gonads arise from the Aorta and enter – in a fascinating asymmetrical fashion (and therefore popular as an exam question) – the left renal vein and the V. cava inferior. Above and medial to the upper pole of the kidneys are the adrenal (suprarenal) glands (Glandulae suprarenales) which constitute endocrine glands that produce steroid hormones (e.g. cortisol) and catecholamines (adrenaline [epinephrine]).

→ Dissection Link

It is useful to dissect the pelvis from the outside and from the inside in order to trace pathways that emerge from the pelvis. The Regio glutealis, the Regio perinealis with the Fossa ischioanalis, and the perineal cavities including all pathways are dissected from the outside. From the inside, the parietal peritoneum is removed together with the perirenal fat capsule including the anterior fascia up to the lesser pelvis. Kidneys and adrenal glands are exposed from the Capsula adiposa; the Ureter and the retroperitoneal neurovascular strucktures with their branches are traced. For proper dissection of the pelvis, it is useful to perform a midsagittal cut in order to split the pelvis into two equal parts. The urinary bladder and the Rectum are mobilised from the connective tissue of the subperitoneal space but remain attached to the blood vessels. The branches of the A. iliaca interna are to be presented as a whole. Some branches exit the pelvis via the Foramina suprapiriforme and infrapiriforme and enter the Regio glutealis and the Regio perinealis. At last, the pelvic floor with its muscle layers is exposed.

Pelvis and Retroperitoneal Space

Organisation of the urinary system

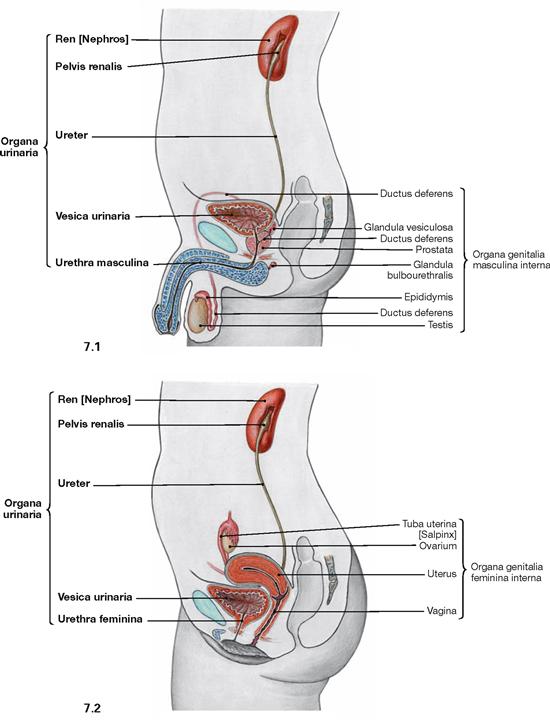

Fig. 7.1 and Fig. 7.2 Organisation of the male (→ Fig. 7.1) and the female (→ Fig. 7.2) urinary system; lateral view from the left side.

The urinary system comprises the paired kidneys (Ren [Nephros]), producing the urine, and the efferent urinary tracts. These consist of:

Except for the Urethra, the urinary system is constructed identically in both sexes. The Urethra within the male penis provides the exit of urine as well as semen. Thus, the male Urethra also belongs to the external male genitalia.

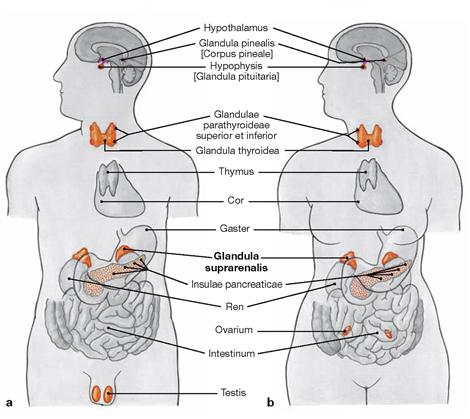

Figs. 7.3a and b Male and female endocrine organs; ventral view.

The adrenal gland (Glandula suprarenalis) does not belong to the urinary organs but to the endocrine glands. Several vital steroid hormones such as aldosterone (mineralocorticoid) and cortisol (glucocorticoid), as well as catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) are produced in the cortex and medulla, respectively, and released into the blood.

Since the adrenal glands are adjacent to the kidneys and are, in part, supplied by the same neurovascular structures, the adrenal gland is discussed here, too.

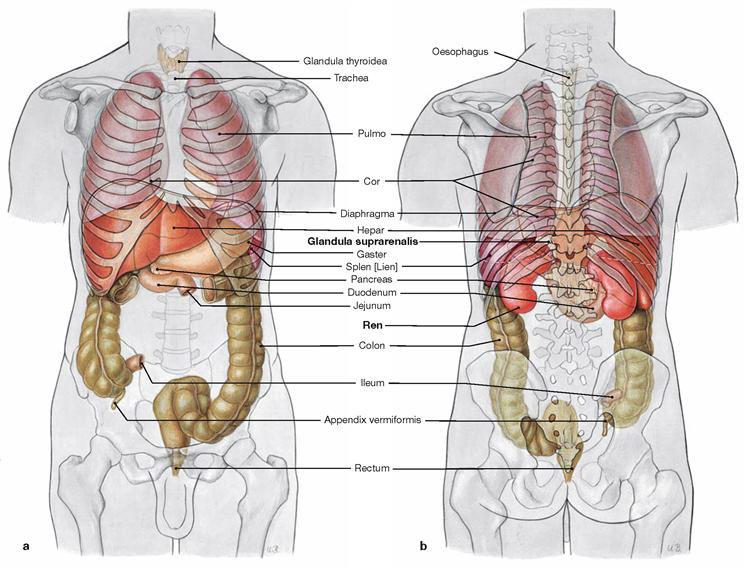

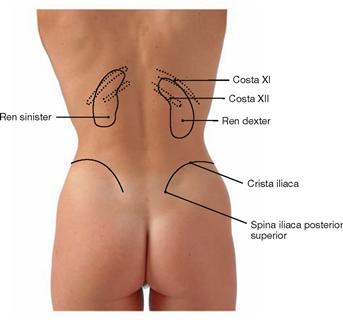

Projection of kidney and adrenal gland

Figs. 7.4a and b Projection of the viscera onto the body surface; ventral (a) and dorsal (b) views.

Kidneys and adrenal glands are located in a retroperitoneal position. The adrenal glands are adjacent to the superior pole of the kidneys and are embedded in the common adipose capsule (Capsula adiposa), which is further enclosed in a sheath of connective tissue (Fascia renalis, GEROTA‘s fascia).

Fig. 7.5 Projection of the kidney onto the dorsal body wall.

These positions only apply for the left kidney.

Due to the size of the liver, the right kidney is located about half a vertebra further down. The superior pole is thus positioned just below rib XI

Because of the proximity of the diaphragm, the position of both kidneys changes during respiration and moves about 3 cm lower during inspiration. The adrenal glands project onto the heads of ribs XI and XII.

Kidney and adrenal gland

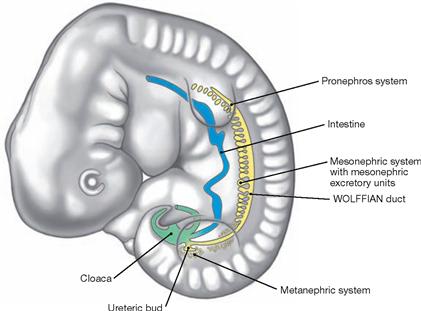

Development of the kidney

Fig. 7.6 Development of the kidneys in week 5. (according to [1])

The kidneys and the efferent urinary tract derive from the mesoderm which, next to the somites, forms nephrogenic cell clusters referred to as nephrotomes. These successively give rise to three kidney generations which are from cranial to caudal:

• pronephros: first generation of a rudimentary kidney which completely regresses.

• mesonephros: temporary excretory tubules are formed, but with the exception of the mesonephric duct (WOLFFIAN duct) the mesonephros also regresses. Its distal part contributes to the formation of the efferent ductules between Testis and Epididymis.

• metanephros: beginning in week 5, the ureteric bud from the WOLFFIAN duct induces the development of the parenchyma of the permanent kidney (nephrons) in the metanephric mesoderm.

The collecting ducts and the proximal parts of the efferent urinary tract (renal pelvis and Ureter) develop from the ureteric bud.

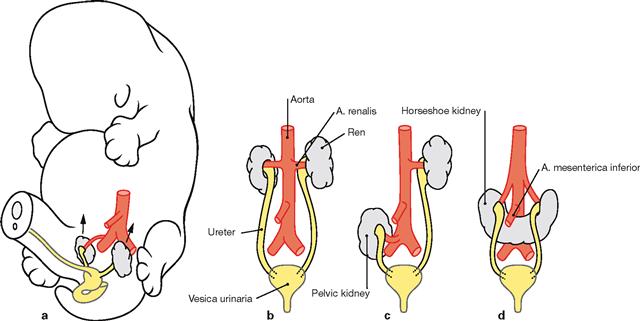

Figs. 7.7a to d Ascensus of the kidneys. (according to [1])

The metanephros develops at the level of the 1st to 4th sacral vertebrae and ascends during weeks 6 to 9 of development. In fact, this is a relative ascensus since the part of the developing body caudal to the inferior pole of the kidney grows faster (a and b). If the kidneys fail to ascend, a pelvic kidney (c) is present. A horseshoe kidney develops if both inferior renal poles position in close proximity to each other and fuse (d). The horseshoe kidney does not fully ascend because the root of the A. mesenterica inferior presents an obstacle.

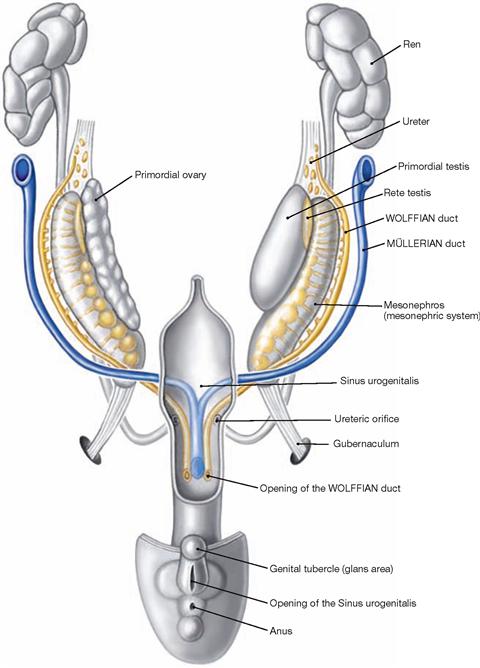

Development of the urogenital organs

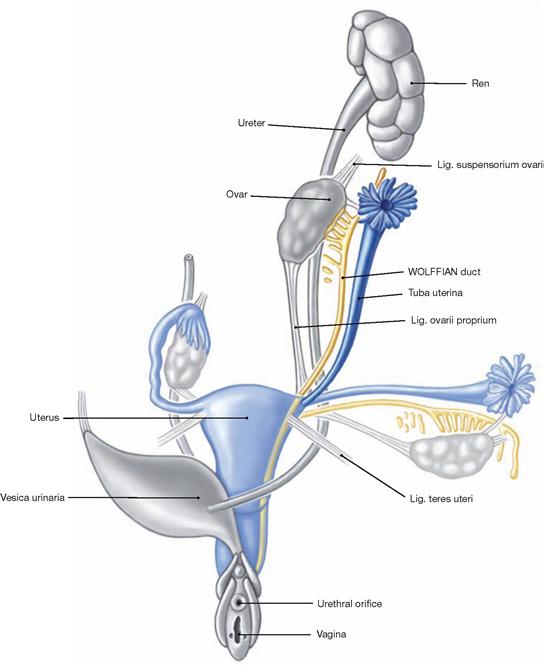

Fig. 7.8 Development of the urinary organs and early development of the internal genital organs in both sexes during week 8. (according to [1])

The kidneys develop from the metanephros and the ureteric bud which arises from the WOLFFIAN duct. The ureteric bud gives rise to the proximal efferent urinary tract (renal pelvis and Ureter) whereas the urinary bladder and the Urethra develop from the Sinus urogenitalis (ventral part of the cloaca of the hindgut).

Until week 7, the internal genitalia develop in a similar manner in men and women (sexually indifferent stage). Besides the indifferent gonads, two parallel duct systems exist: the Ductus mesonephricus or WOLFF-IAN duct and the Ductus paramesonephricus or MÜLLERIAN duct. In contrast to the WOLFFIAN duct, the distal ends of the MÜLLERIAN duct fuse prior to entering the Sinus urogenitalis. At the end of week 7 the indifferent gonad develops into the Testis and into the ovary, respectively. The hormones produced in the Testis (testosterone and anti-MÜLLERIAN hormone) induce the differentiation of the WOLFFIAN duct to the male internal genitalia (→ Fig. 7.43) and the suppression of the further development of the MÜLLERIAN duct. If both hormones are not present, female internal genitalia develop (→ Fig. 7.73).

Topography of the kidney and adrenal gland

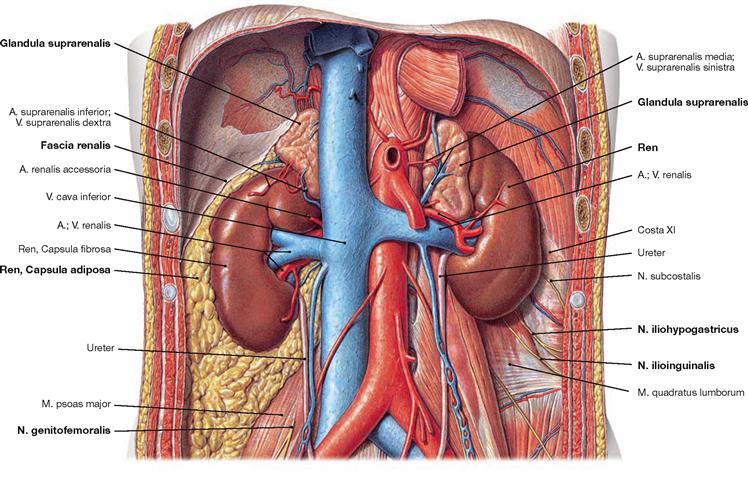

Fig. 7.9 Position of the kidney, Ren [Nephros], and adrenal gland, Glandula suprarenalis, in the retroperitoneal space; ventral view.

Kidney and adrenal gland are located in the retroperitoneal space ventrally of the M. psoas and the M. quadratus lumborum.

Fascial systems: The surface of the kidney is covered by a organ capsule of dense connective tissue (Capsula fibrosa). Together with the adrenal gland, the kidney is covered by a capsule of perinephric fat (Capsula adiposa). The perinephritic adipose tissue is surrounded by a connective tissue sheath (Fascia renalis). Medially and inferiorly, the renal fascia remains open for the passage of the Ureter and the blood vessels. The anterior lamina of the renal fascia is referred to by clinicians as GEROTA’s fascia.

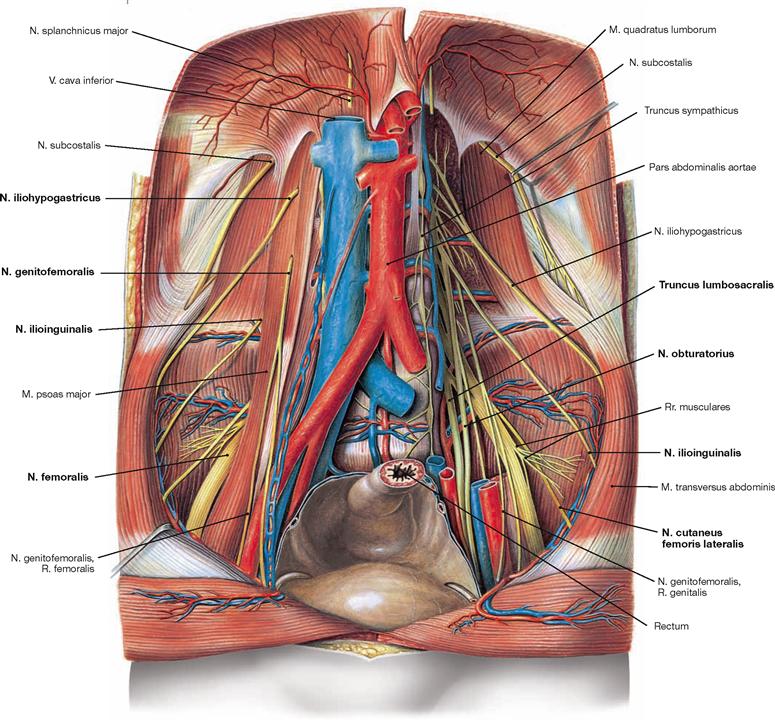

Proximity to the nerves of the Plexus lumbalis: Between the renal fascia in the area of the inferior renal pole and the muscles of the dorsal abdominal wall, the N. iliohypogastricus and the N. ilioinguinalis from the Plexus lumbosacralis descend. They provide sensory innervation to the skin of the inguinal region. The N. genitofemoralis courses further caudally and therefore has no contact to the kidney, but to the Ureter.

Further cranially, the 11th and 12th intercostal nerves (12th intercostal nerve = N. subcostalis) course beneath the lower ribs along the posterior side of the kidney.

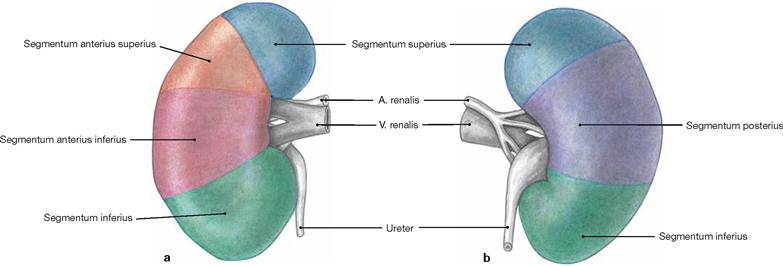

Segments and topographical relationships of the kidney

Figs. 7.10a and b Renal segments, Segmenta renalia, right side; ventral (a) and dorsal (b) views.

The renal artery (A. renalis) divides at the hilum of the kidney into a R. principalis anterior, which supplies the superior, the two anterior and the inferior renal segments with several branches, and the R. principalis posterior for the posterior segment. In the case of occlusion of one of the branches of the A. renalis, the extent of renal infarction correlates to the area of the affected renal segments. However, the branching patterns are highly variable among individuals.

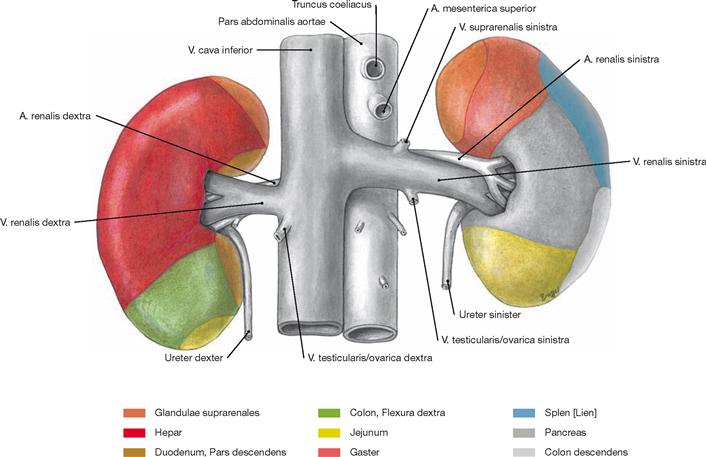

Fig. 7.11 Contact areas of the kidney, Ren [Nephros], with adjacent organs; ventral view.

The dorsal side of the kidney is adjacent to the dorsal abdominal wall. The anterior side has contact to several other organs. Together with the adrenal glands, the kidneys are separated from the other abdominal organs by the parietal peritoneum, the renal fascia, and the adipose capsule. Thus, the anterior contact areas have no clinical relevance.

Organisation of the kidney

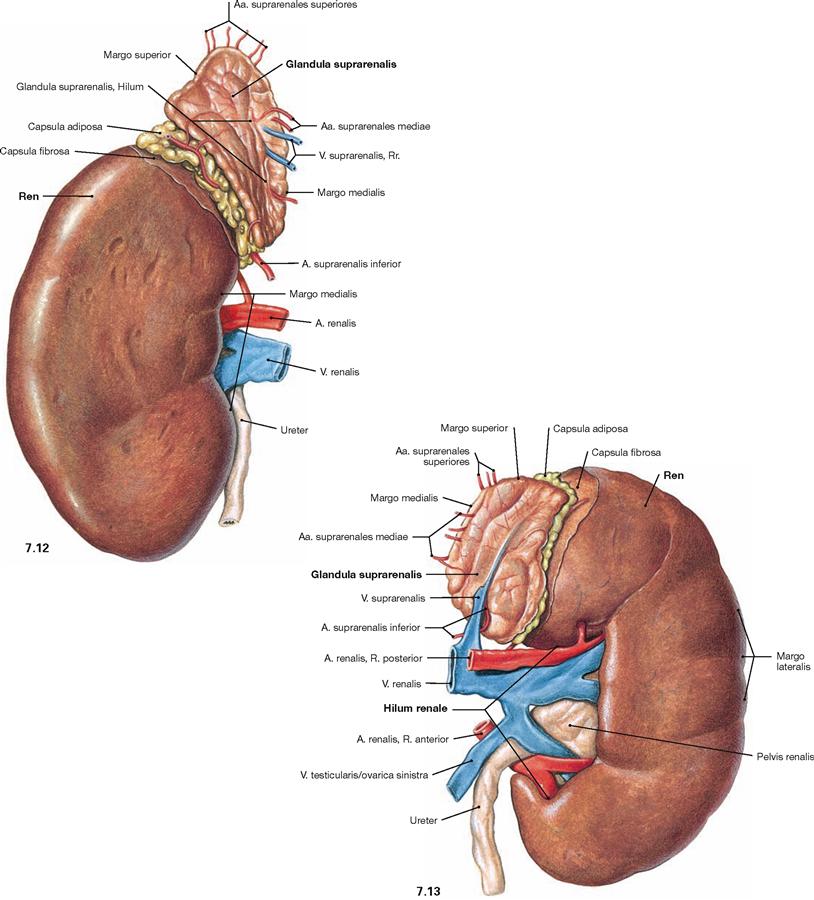

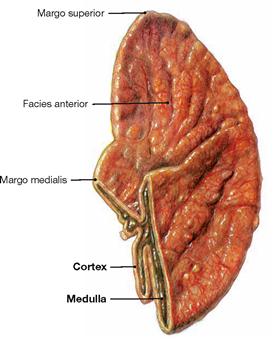

Fig. 7.12 and Fig. 7.13 Kidney, Ren [Nephros], and adrenal gland, Glandula suprarenalis, right side (→ Fig. 7.12) and left side (→ Fig. 7.13); ventral view.

The bean-shaped kidney has a superior and an inferior pole. Located between the poles and oriented medially is the hilum of the kidney (Hilum renale) which connects to the inner space of the kidney (Sinus renalis) and contains the renal blood vessels and the Ureter. The adrenal gland is adjacent to the superior pole of the kidney. The entrance of the blood vessels at the medial margin is sometimes also referred to as the hilum.

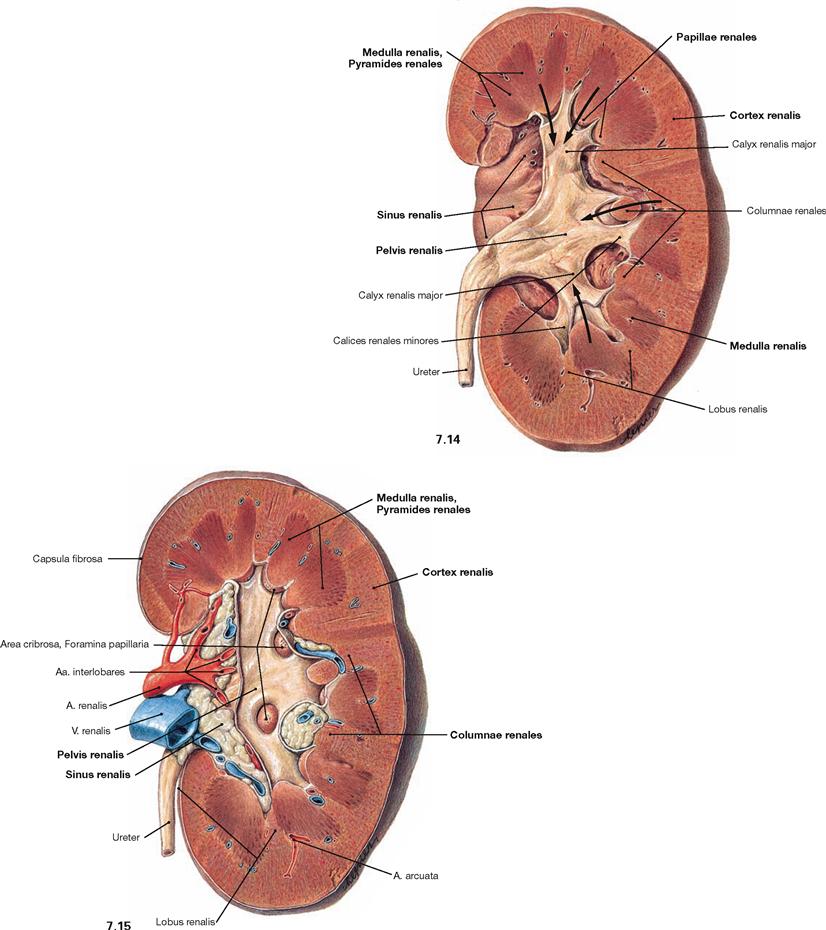

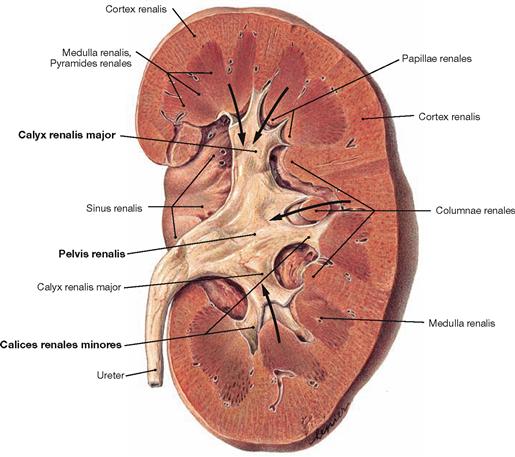

Fig. 7.14 and Fig. 7.15 Kidney, Ren [Nephros], left side; ventral view; after vertical bisection (→ Fig. 7.14) and opening of the renal pelvis (→ Fig. 7.15).

The kidney consists of a cortex (Cortex renalis) and a medulla (Medulla renalis). The medulla is subdivided into several parts which, according to their shape, are referred to as renal pyramids (Pyramides renales). Located between these renal pyramids are the renal columns

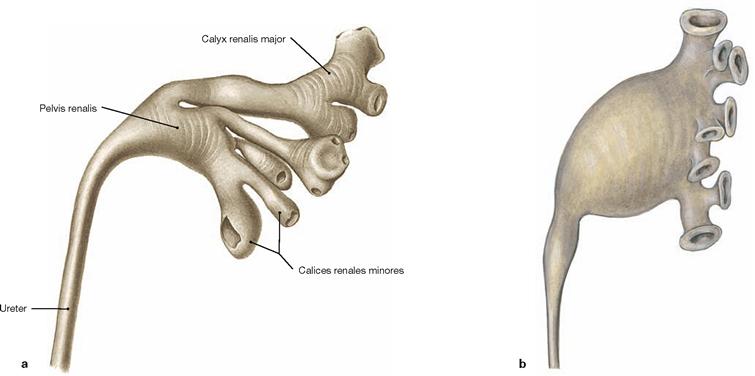

(Columnae renales). One pyramid and its adjacent cortical area is called a renal lobe (Lobus renalis). The border between the 14 lobes is not visible at the surface of an adult human kidney. The tips of the pyramids (Papillae renales) enter the renal calyces (Calices renales majores and minores) to release the urine (arrows). Together with adipose tissue and the renal blood vessels, the renal pelvis (Pelvis renalis) is located in a medial recess of the parenchyma of the kidney (Sinus renalis).

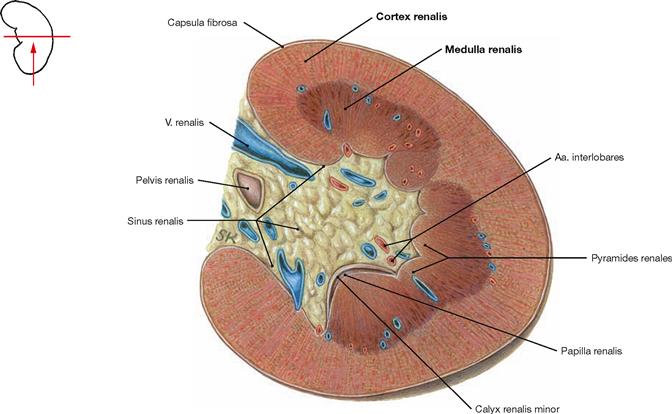

Fig. 7.16 Kidney, Ren [Nephros]; transverse section through the renal sinus (Sinus renalis); caudal view.

The parenchyma of the kidney is composed of a cortex (Cortex renalis) and a medulla (Medulla renalis).

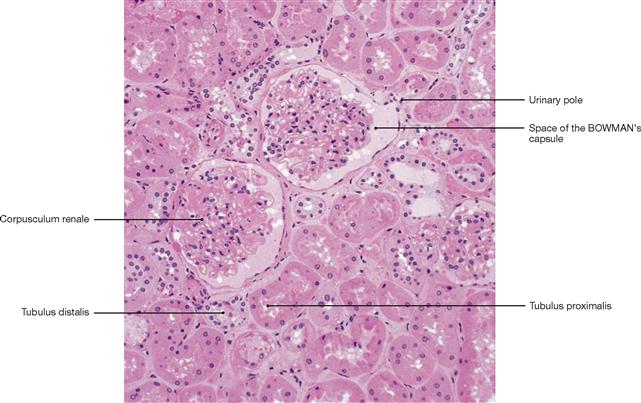

Fig. 7.17 Renal cotex (Cortex renalis); microscopic section, 100-fold. [26]

The entire parenchyma of the kidney consists of nephrons and collecting ducts. Nephrons comprise renal corpuscles and a tubular system. Renal corpuscles (Corpuscula renalia) are located in the renal cortex, but not in the renal medulla. In the renal corpuscles, water and low molecular weight constituents from the plasma are filtered into the space of the BOWMAN‘s capsule (primary urine, 170 l/day). From the urinary pole of the BOWMAN‘s capsule, the primary urine enters the proximal tubule (Tubulus proximalis). In the tubular system and the collecting ducts the major part of the primary urine is reabsorbed and the urine composition is altered by secretion before the final urine is released into the renal papillae and the renal pelvis (1.7 l/day).

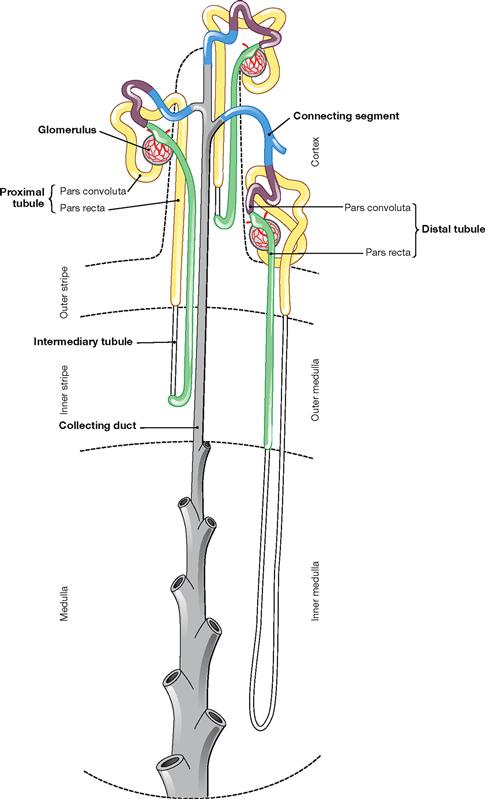

Fig. 7.18 Organisation of nephron and collecting duct; schematic illustration. (according to [1])

At the renal corpuscle, where the primary urine is produced, the proximale tubule begins with a convoluted part (Pars convoluta) and a consecutive straight part (Pars recta). This is continued by the intermediate tubule which consists of a descending (Pars descendens) and an ascending limb (Pars ascendens) followed by the distal tubule (again with Pars recta and Pars convoluta). The connecting segment (collecting tubule) is the transition to the collecting duct which finally releases the urine into the renal pelvis.

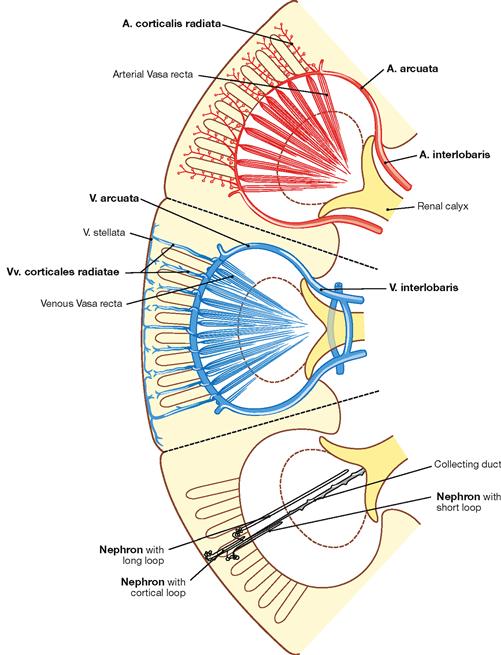

Fig. 7.19 Course of arteries (red), veins (blue), and nephrons (grey) in the renal parenchyma; schematic illustration. (according to [1])

The A. and V. renalis divide at the hilum and ascend as A. and V. interlobaris at the edge of the pyramids. They arch around the base of the pyramids as A. and V. arcuata and from there give rise to the A. and V. corticalis radiata to reach the capsule. In contrast to the communicating veins, the arteries are terminal arteries. Therefore, the occlusion of an artery, for example by a blood clot (embolism), will cause a renal infarction.

Within the lobes of the kidney the nephrons are arranged radially.

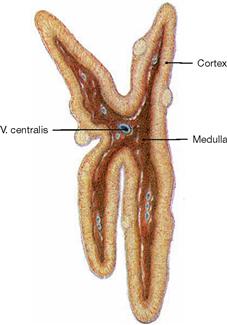

Organisation of the adrenal gland

Fig. 7.20 Adrenal gland, Glandula suprarenalis, right side; ventral view.

The adrenal gland consists of cortex and medulla. Both have different developmental origins and functions. The cortex develops from the mesoderm of the dorsal abdominal cavity (intra-embryonic coeloma), the medulla, however, derives from neural crest cells and is equivalent to a modified sympathetic ganglion.

Fig. 7.21 Adrenal gland, Glandula suprarenalis, right side; sagittal section; lateral view.

The adrenal gland is a vital endocrine gland. The cortex produces steroid hormones (mineralocorticoids, glucocorticoids, androgens), the medulla produces catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) for the regulation of metabolism and blood pressure.

Blood vessels of the kidney

Fig. 7.22 Course of the A. and V. renalis; ventral view.

The paired Aa. renales arise from the abdominal aorta and course dorsal to the veins to the hilum of the kidney. The right A. renalis crosses the V. cava inferior posteriorly. At the hilum, they divide into several branches.

The Vv. renales drain into the V. cava inferior on both sides. The left V. renalis receives blood from three tributaries, whereas on the right side these veins enter the V. cava inferior directly:

The regional lymph nodes of the kidney are the Nodi lymphoidei lumbales around the aorta and the V. cava inferior.

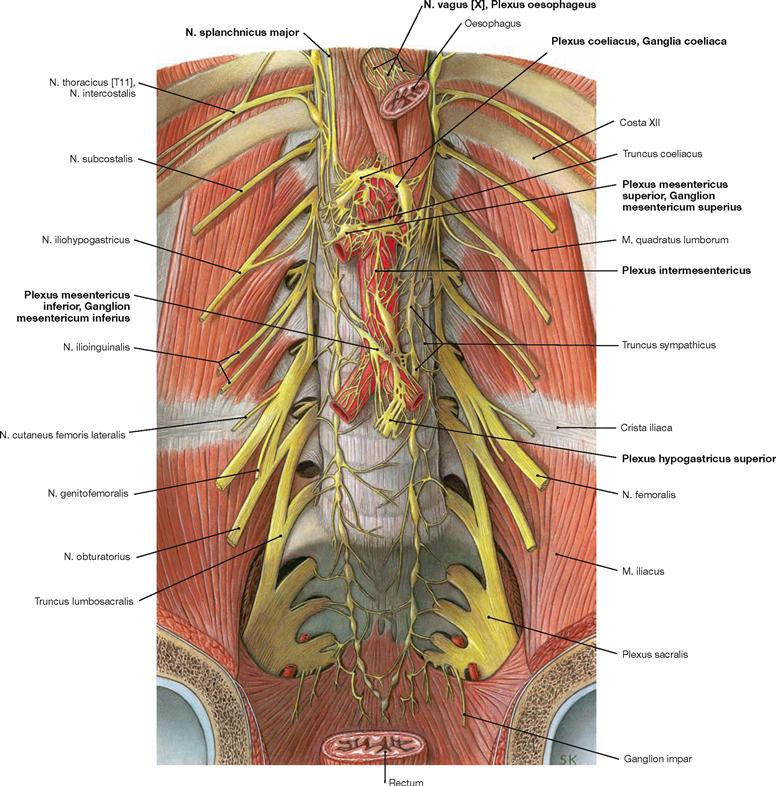

The postganglionic sympathetic nerves to the kidney derive from the Ganglion aorticorenale and form the Plexus renalis around the A. renalis.

Blood vessels of kidney and adrenal gland

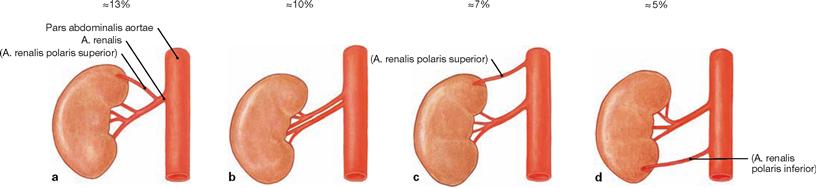

Figs. 7.23a to d Variations of the arterial supply of the kidney; ventral view.

Polar arteries do not enter the kidney at the hilum, but reach the renal parenchyma directly. Accessory arteries independently arise from the Aorta.

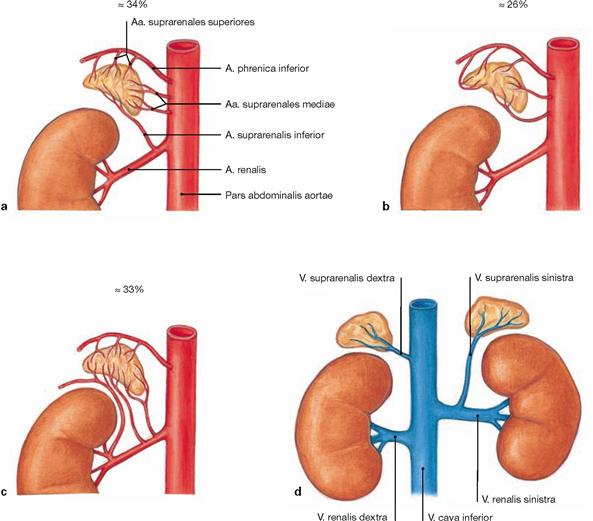

Fig. 7.24a to d Suprarenal arteries, Aa. suprarenales, and suprarenal vein, V. suprarenalis; ventral view.

Usually there are three arteries to the adrenal gland:

• A. suprarenalis superior: derives from the A. phrenica inferior

This “luxurious” arterial supply prevents infarctions of the vital adrenal gland.

Variations of the arteries to the adrenal gland:

a. arterial supply via three arteries (textbook case)

In contrast, only one suprarenal vein exists for each adrenal gland. The V. suprarenalis collects the blood from the adrenal gland and drains into the V. cava inferior on the right side, and into the V. renalis sinistra on the left side (d).

The regional lymph nodes of the adrenal gland are the Nodi lymphoidei lumbales around the aorta and V. cava inferior.

The autonomic innervation derives from preganglionic (!) sympathetic nerve fibres from the Nn. splanchnici (the adrenal medulla represents a sympathetic paraganglion).

Kidney, imaging

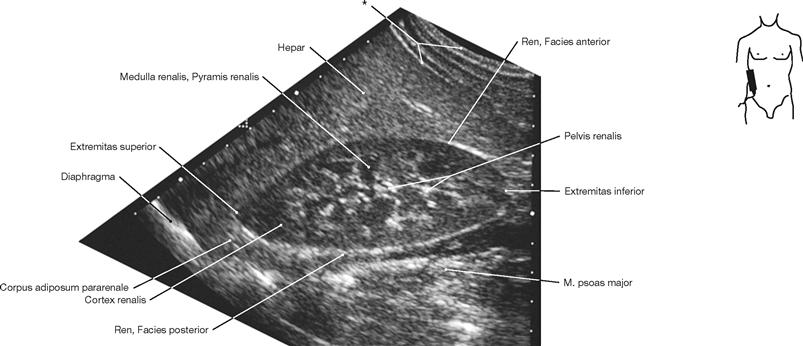

Fig. 7.25 Kidney, Ren [Nephros], right side; ultrasound image; lateral view; transducer positioned almost vertically.

* abdominal wall

Fig. 7.26 Kidney, Ren [Nephros]; right side; computed tomographic transverse section (CT); caudal view.

CT-guided renal biopsies are performed to obtain tissue specimens for diagnostic purposes in cases of obscure dysfunctions of the kidney.

* direction of the needle for renal biopsy, also named fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB).

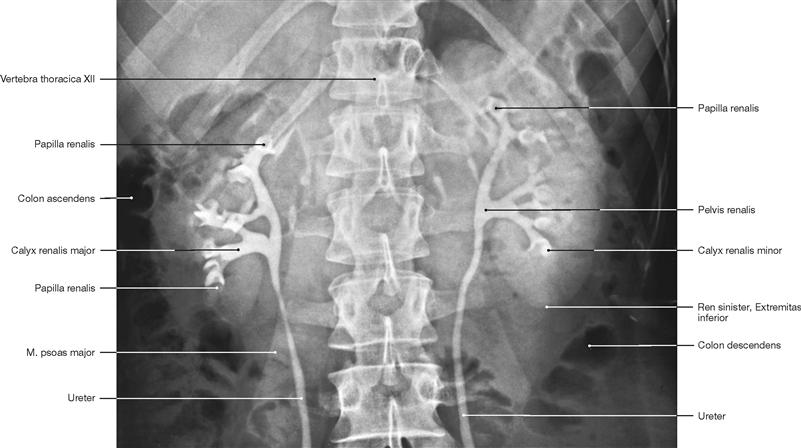

Renal pelvis and ureter

Fig. 7.27 Renal pelvis, Pelvis renalis, left side; ventral view.

Urine is released from the renal pyramids to the renal calyces (Calices renales; arrows).

Ureter

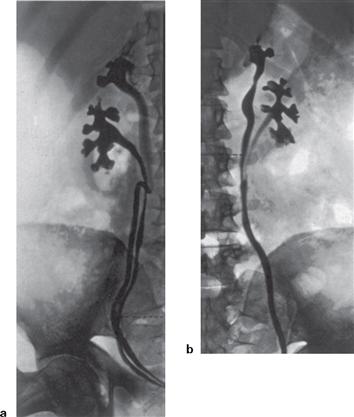

Fig. 7.29 Parts, constrictions, and course of the ureter; ventral view.

Parts:

• Pars abdominalis: in the retroperitoneal space

• Pars pelvica: in the lesser pelvis

• Pars intramuralis: traverses the wall of the urinary bladder

• at the exit from the renal pelvis

• at the crossing of the A. iliaca communis or A. iliaca externa

• at the passage through the wall of the urinary bladder (most narrow part)

Course:

the ureter first crosses over the N. genitofemoralis, courses under the A. and V. testicularis/ovarica, crosses over the A. and V. iliaca and then crosses under and passes beneath the Ductus deferens in men and the A. uterina in women.

Renal pelvis and ureter, imaging

Fig. 7.30 Renal pelvis, Pelvis renalis, and ureter, Ureter; radiograph in anteroposterior (AP) beam projection after retrograde injection of contrast medium via both ureters; ventral view.

Figs. 7.31a and b Common variations of the ureter, Ureter; radiographs in anteroposterior (AP) beam projection after retrograde injection of contrast medium via both ureters; ventral view. [18]

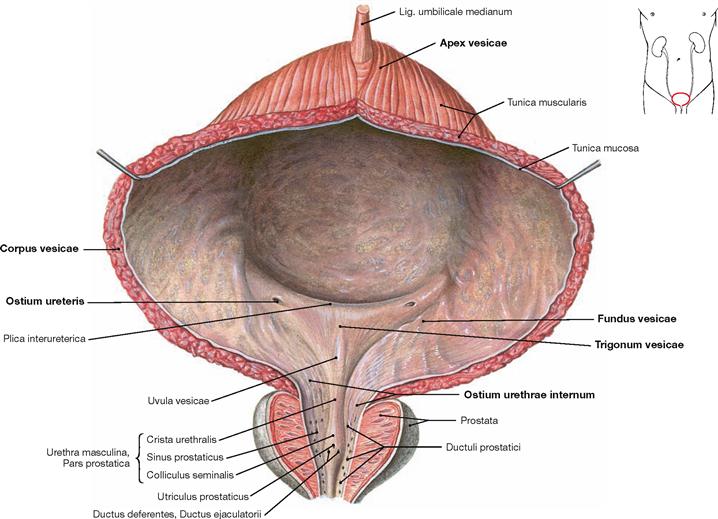

Structure of the urinary bladder

Fig. 7.32 Urinary bladder, Vesica urinaria, and opening into the male urethra, Urethra; ventral view.

The urinary bladder is located in the subperitoneal space and is composed of a body (Corpus vesicae), apex (Apex vesicae), and an inferior fundus (Fundus vesicae). At the fundus, the internal urethral orifice (Ostium urethrae internum) and the two ureteric orifices (Ostium ureteris) form the trigone of the bladder (Trigonum vesicae). The urinary bladder holds about 500–1500 ml of urine, although the urge to urinate starts when a volume of 250–500 ml is reached. The wall consists of the internal mucosal layer (Tunica mucosa) followed by three layers of smooth muscles with parasympathetic innervation (Tunica muscularis = M. detrusor vesicae), and the external Tunica adventitia or the cranial Tunica serosa (peritoneum), respectively.

The urinary bladder is surrounded by paravesical adipose tissue and stabilised by several ligaments. At the apex, the Lig. umbilicale medianum (contains the urachus, a remnant of the embryonic connection of the allantois) connects to the Umbilicus. In women, the bilateral Lig. pubovesicale (→ Fig. 7.116) and in men the bilateral Lig. puboprostaticum (→ Fig. 7.115) anchor the bladder to the bony pelvis. In men, the prostate gland is located directly beneath the fundus of the bladder and is traversed by the Urethra.

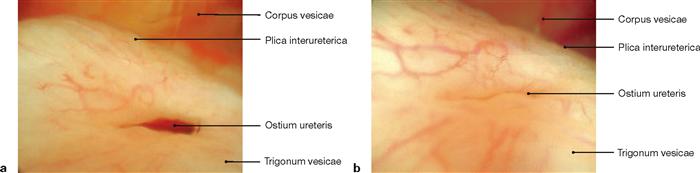

Figs. 7.33 a and b Ureteric orifice, Ostium ureteris; cystoscopy.

The valve-like shape of the ureteric orifice contributes substantially to the prevention of urine backflow which may endanger the kidneys via ascending urinary tract infections.

Urinary bladder and urethra in men

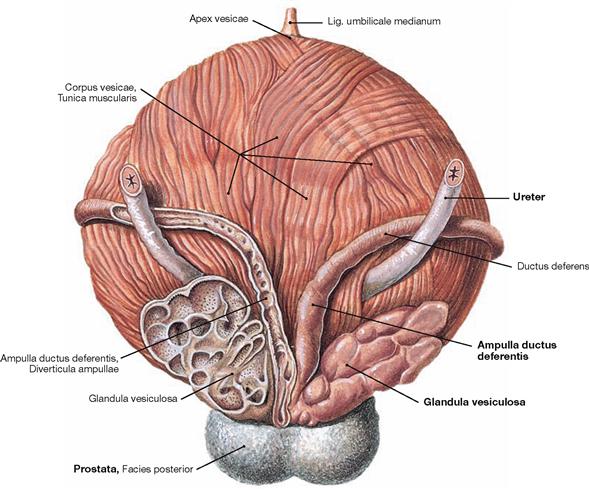

Fig. 7.34 Urinary bladder, Vesica urinaria, vas deferens, Ductus deferentes, seminal vesicle, Glandula vesiculosa, and prostate gland, Prostata; dorsal view.

In men, the following paired anatomical structures are positioned posterior and adjacent to the bladder, from medial to lateral:

• dilated part of the vas deferens (Ampulla ductus deferentis)

The urinary bladder is positioned directly superior to the prostate gland.

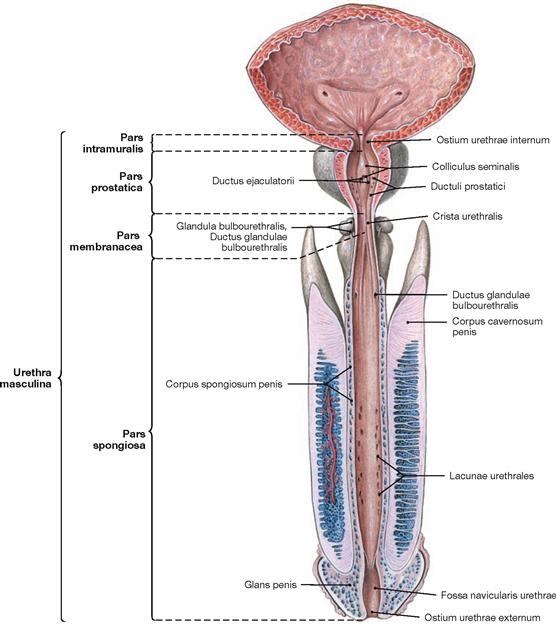

Fig. 7.35 Urinary bladder, Vesica urinaria, and male urethra, Urethra masculina; ventral view; urinary bladder and Urethra opened ventrally.

Parts of the Urethra:

• Pars intramuralis (1 cm): within the wall of the urinary bladder

• Pars prostatica (3.5 cm): traverses the prostate gland. Here the following ducts enter the Urethra: Ductus ejaculatorii (common duct of vas deferens and seminal vesicle) on the Colliculus seminalis and the prostatic ducts on both sides.

• Pars membranacea (1–2 cm): traverses the pelvic floor.

• Pars spongiosa (15 cm): embedded in the Corpus spongiosum of the Penis, runs to the external urethral orifice (Ostium urethrae externum). COWPER‘s glands (Glandulae bulbourethrales) and LITTRÉ‘s glands (Glandulae urethrales) enter here. The terminal part is dilated to form the Fossa navicularis.

Urethra in men

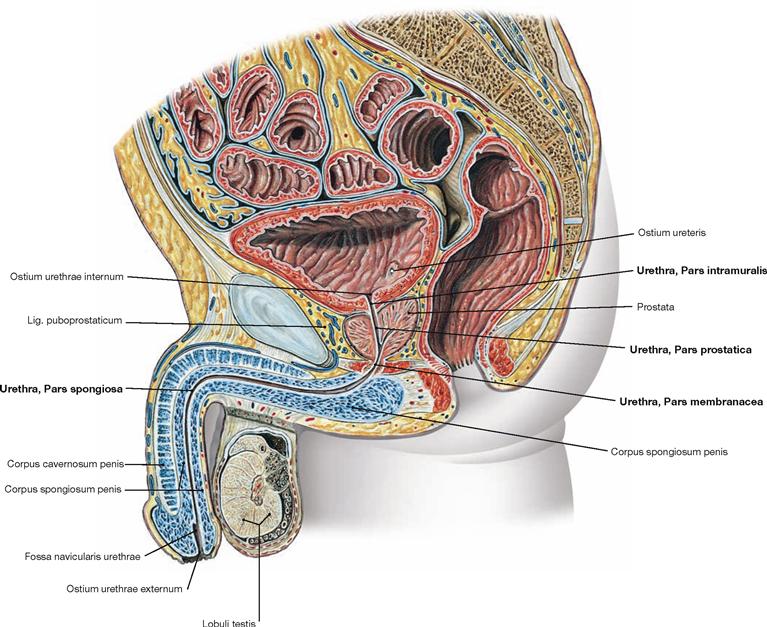

Fig. 7.36 Male pelvis, Pelvis; median section; view from the left side.

The illustration shows the course and the parts of the male Urethra (Urethra masculina):

Urethra in women

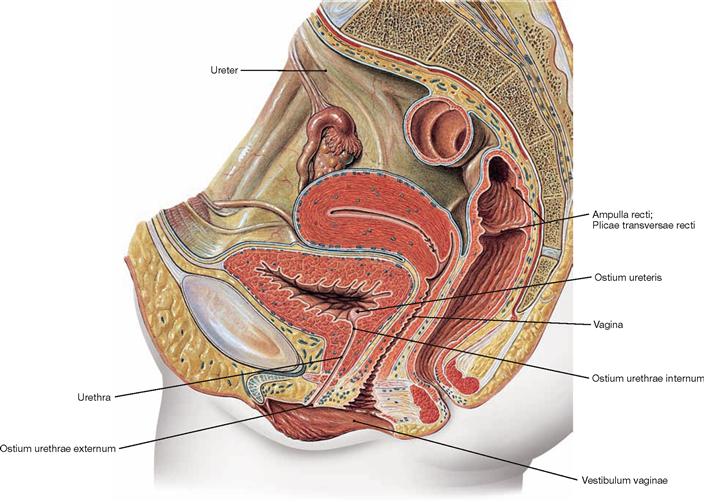

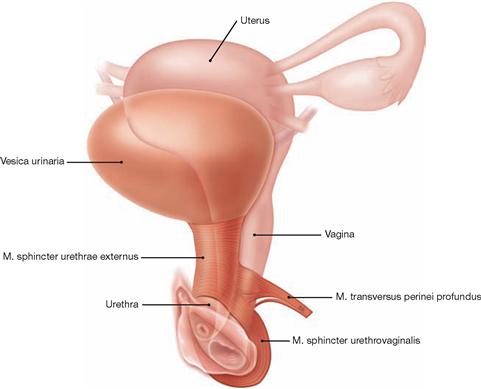

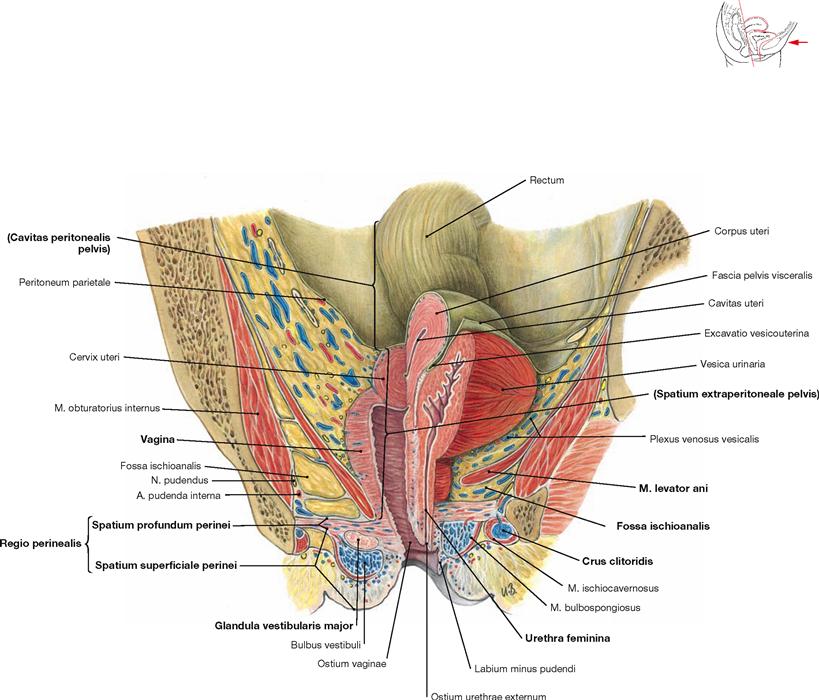

Fig. 7.37 Female pelvis, Pelvis; median section; view from the left side.

The illustration shows the course and the external orifice of the female urethra. The female urethra is 3–5 cm long and enters directly in front of the Vagina in the vestibule (Vestibulum vaginae).

Sphincter mechanisms of the urinary bladder

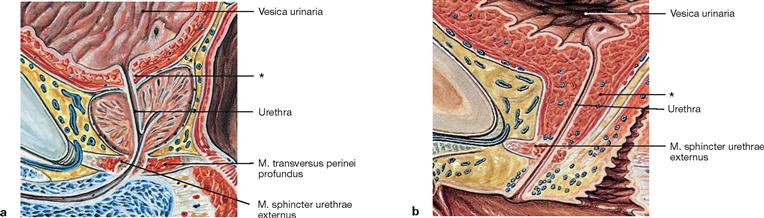

Figs. 7.38a and b Sphincter mechanisms of urinary bladder, Vesica urinaria, and urethra, Urethra, in men (a) and in women (b); median section; view from the left side.

Contributing to the sphincter mechanisms are not only smooth muscle fibres in the wall of the urinary bladder but also striated muscles of the perineum:

• smooth muscles of the circular muscle layer of the Urethra (“M. sphincter urethrae internus“): morphologically, a true sphincter muscle is not identified.

• M. sphincter urethrae externus: in men a separation of the M. transversus perinei profundus which often does not exist in women.

In addition, the shape of the pelvic floor (Diaphragma pelvis) is important in supporting the urinary bladder, and thus ensuring urinary continence.

During urination (micturition) the smooth muscles of the wall of the bladder (M. detrusor vesicae) contract following parasympathetic activation. At the same time, the striated muscles of the pelvic floor relax allowing the bladder to descend, the sphincter muscles to relax, and urination to occur.

* smooth muscles of the Urethra

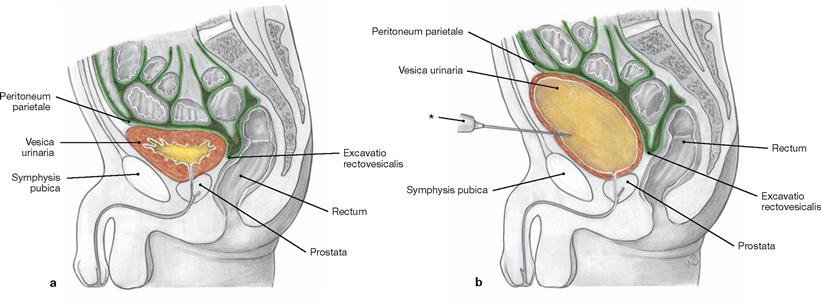

Figs. 7.39a and b Urinary bladder, Vesica urinaria, empty (a) and urine-filled (b); schematic median section; view from the left.

The urinary bladder is located in the subperitoneal space and is covered by parietal peritoneum on its upper surface. The empty bladder is positioned behind the pubic symphysis (Symphysis pubica). When filled,

the bladder rises above the pubic sumphysis and can be accessed without opening the peritoneal cavity (suprapubic cystostomy) for cystoscopy or insertion of a suprapubic catheter.

* puncture needle

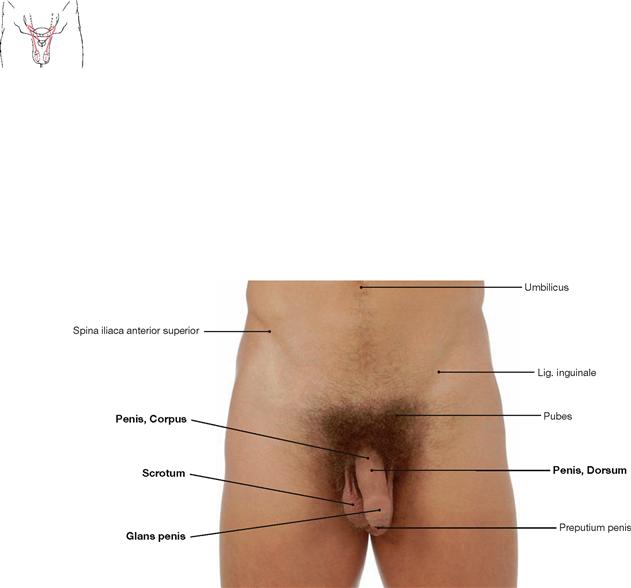

External male genitalia

Fig. 7.40 External male genitalia, Organa genitalia masculina externa; ventral view.

The male genitalia are categorised as external genitalia (Organa genitalia masculina externa) and internal genitalia (Organa genitalia masculina interna → Fig. 7.41).

The external male genitalia comprise:

The external genitalia are the sexual organs. The Penis serves intercourse.

The Urethra is described with the efferent urinary system (→ pp. 178 and 179).

Genitalia

Internal male genitalia

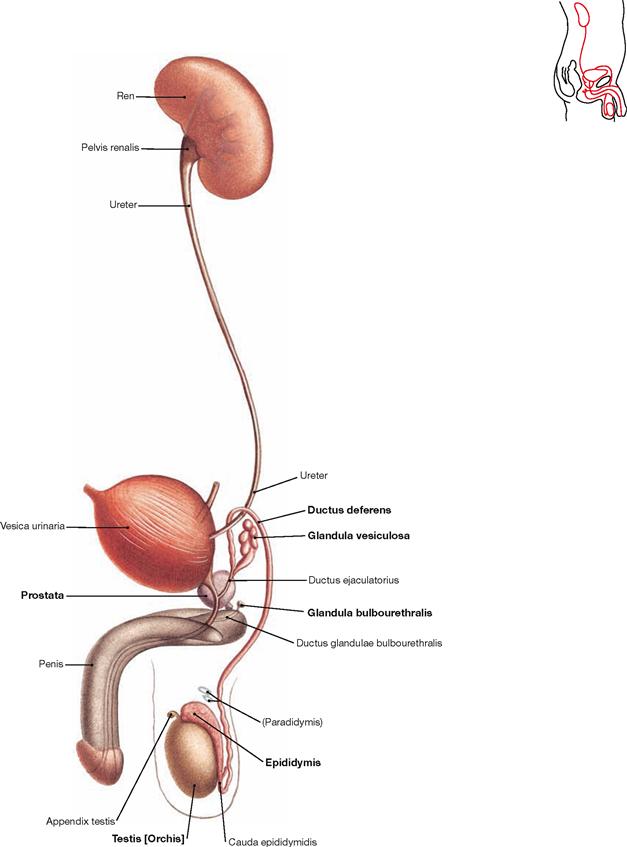

Fig. 7.41 Male urinary and sex organs, Organa urogenitalia masculina; view from the right side.

The inner male genitalia comprise:

Testis and Epididymis belong to the internal genitalia because during development they were relocated from the intra-abdominal cavity into the Scrotum together with a peritoneal covering (forming the Cavitas serosa scroti).

The internal genitalia are reproductive organs and serve the production, maturation, and transport of spermatozoa and the production of seminal fluid. The testes also produce male sex hormones (testosterone).

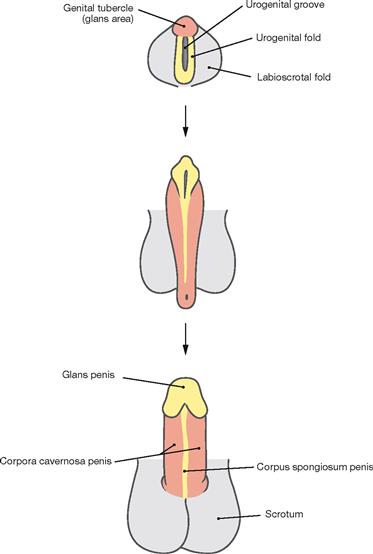

Development of the external male genitalia

Fig. 7.42 Development of the external male genitalia, Organa genitalia masculina externa.

The external genitalia develop from the caudal part of the Sinus urogenitals. The Sinus urogenitalis develops from the cloaca of the hindgut and gives rise to the urinary bladder and parts of the Urethra (→ Fig. 7.8). Also contributing are the ectoderm and the connective tissue (mesenchyme) beneath. The first part in the development of the external genitalia is identical in both sexes (indifferent gonad). The anterior wall of the Sinus urogenitalis indents to form the urethral groove which is bordered on both sides by the urethral folds. Lateral to those the labioscrotal folds are located and anterior to the groove lie the genital tubercles. Subsequently, in men the genital tubercle develops into the Penis (Corpora cavernosa) due to the influence of the male sex hormone testosterone which is produced in the Testes. The genital folds merge above the urethral groove to form the Corpus spongiosum and the Glans penis. This way, simultaneously the Pars spongiosa of the Urethra develops. The Pars prostatica and the Pars membranacea of the Urethra derive further proximally from the Sinus urogenitalis. The labioscrotal folds enlarge and fuse to form the Scrotum.

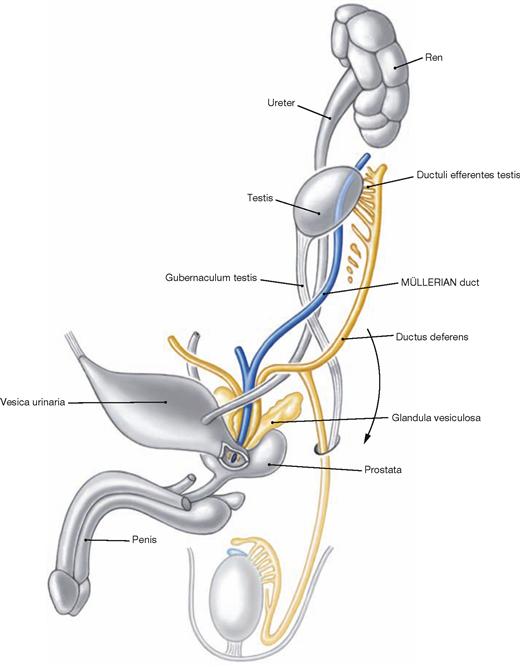

Development of the internal male genitalia

Fig. 7.43 Development of the internal male genitalia, Organa genitalia masculina interna. (according to [1])

Up to week 7, development of the internal genitalia is identical in both sexes (sexual indifferent stage, → Fig. 7.8). In the male, the primordium of the primitive gonad then develops into the Testis. The Testis develops in the lumbar region at the level of the mesonephros which contributes several canaliculi as a connection between the Testis and the Epididymis. Due to the longitudinal growth of the body the Testis is then relocated caudally (Descensus testis) but remains connected to its vascular structures. Along the inferior mesenchymal gubernaculum (Gubernaculum testis) a peritoneal pouch is formed (Proc. vaginalis peritonei) which reaches down to the future Scrotum and serves in guiding the descent of the Testis, a process normally completed at birth. At birth, the Proc. vaginalis peritonei closes and obliterates in the area of the Funiculus spermaticus. The distal part of the Proc. vaginalis remains and forms a part of the testicular coverings (Tunica vaginalis testis).

The sex hormones of the Testis (mainly testosterone) induce the final differentiation of the WOLFFIAN duct to the internal male genitalia (Epididymis, Ductus deferens), the seminal vesicles, and other accessory sex glands (prostate gland, COWPER’s glands) from the Sinus urogenitalis. The anti-MÜLLERIAN hormone suppresses the differentiation of the MÜLLERIAN ducts into female genitalia.

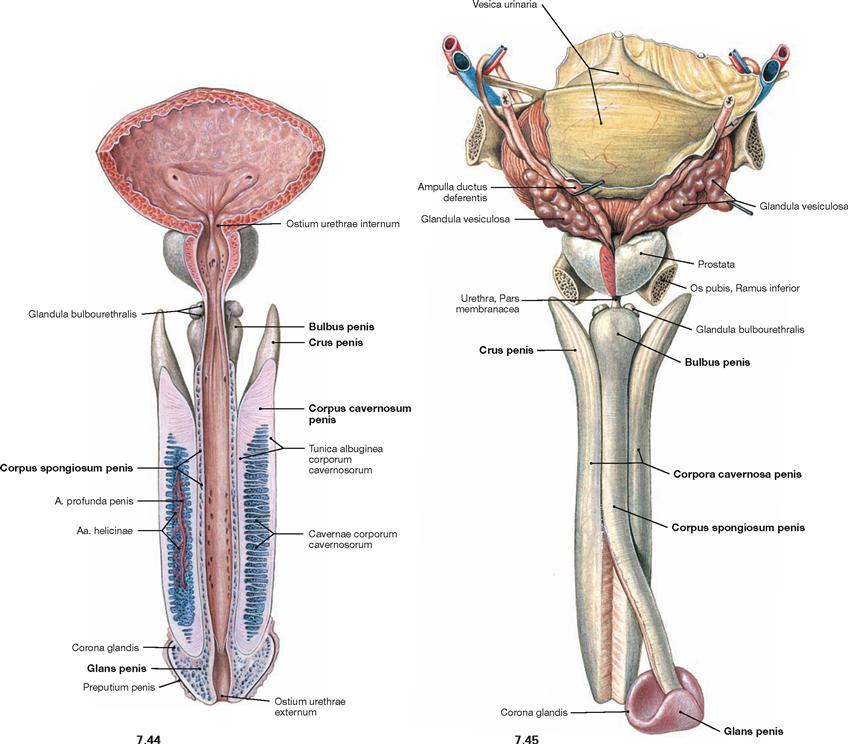

Penis

Fig. 7.44 and Fig. 7.45 Urinary bladder, Vesica urinaria, prostate gland, Prostata, and penis, Penis, with exposed cavernous bodies; ventral view, urinary bladder and Urethra opened (→ Fig. 7.44) and dorsal view (→ Fig. 7.45).

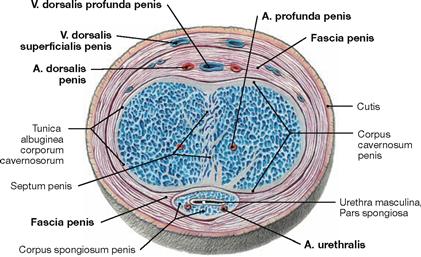

In a flaccid state, the Penis is usually about 10 cm long and divided into the body (Corpus penis), glans (Glans penis), and base or root (Radix penis). It consists of the paired Corpora cavernosa which are enclosed in a dense fibrous covering (Tunica albuginea) and separated by a Septum penis. The other component is the Corpus spongiosum surrounding the Urethra. The proximal parts (Crura penis) of the Corpora cavernosa are fixed to the inferior pubic rami. The proximal and distal parts of the Corpus spongiosum are dilated to form the Bulbus penis and the Glans penis, respectively. All cavernous bodies together are ensheathed by the fascia of the Penis (Fascia penis), which was removed in this illustration.

For the different parts of the male Urethra (Urethra masculina) → Figs. 7.35 and 7.36.

Genitalia

Penis and scrotum

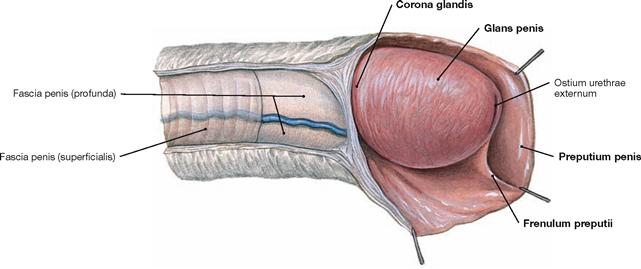

Fig. 7.46 Penis with glans, Glans penis, and prepuce, Preputium penis; view from the right side.

The distal end of the Penis is enlarged to form the Glans penis and shows a ridge (Corona glandis) at its base. In the flaccid state, the glans is covered by the prepuce (Preputium penis). At its underside, the prepuce is connected by a small ligament (Frenulum preputii).

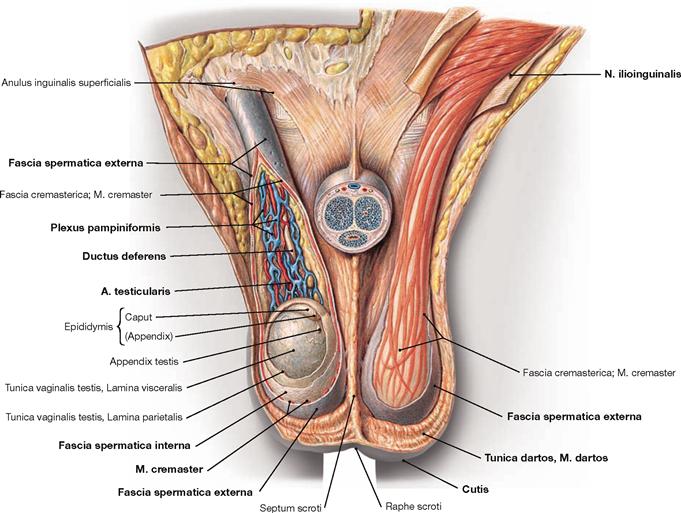

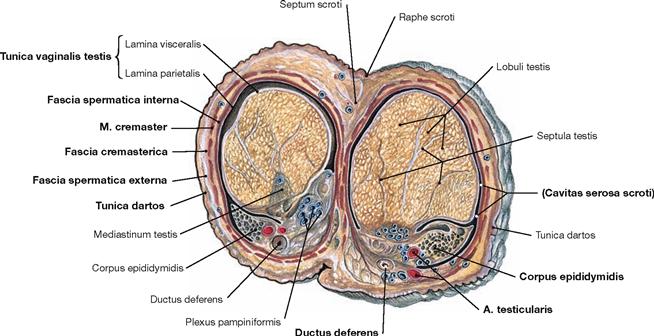

Fig. 7.47 Scrotum, Scrotum; ventral view; the Scrotum opened and the Penis sectioned in the front.

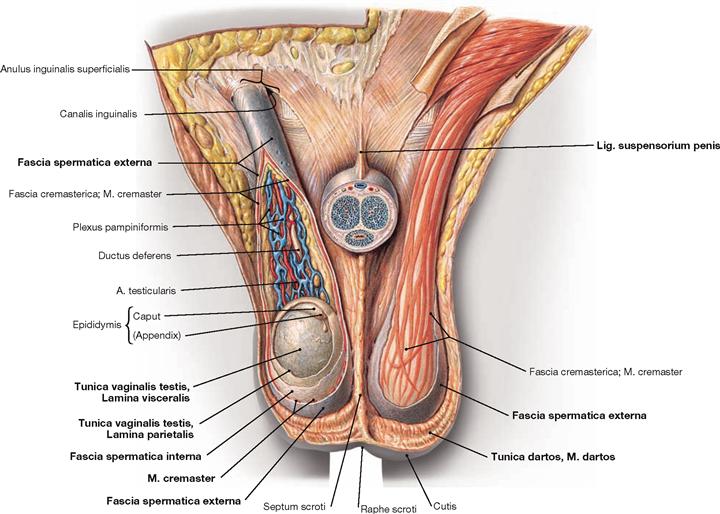

The root of the Penis is attached to the anterior body wall by the superficial Lig. fundiforme penis and the deep Lig. suspensorium penis. The Scrotum is divided internally by a septum which at the outside corresponds to the Raphe scrotum of the skin.

Testis and Funiculus spermaticus have the following coverings:

• Tunica dartos: subcutaneous layer with smooth muscles

• Fascia spermatica externa: continuation of the superficial body fascia (Fascia abdominalis superficialis)

• M. cremaster with Fascia cremasterica

• Fascia spermatica interna: continuation of the Fascia transversalis

In addition, the testis is covered with the Tunica vaginalis testis which consists of an external Lamina parietalis (periorchium) and an inner Lamina visceralis (epiorchium). Both are connected by the mesorchium and create between them the Cavitas serosa scroti.

Testis and epididymis

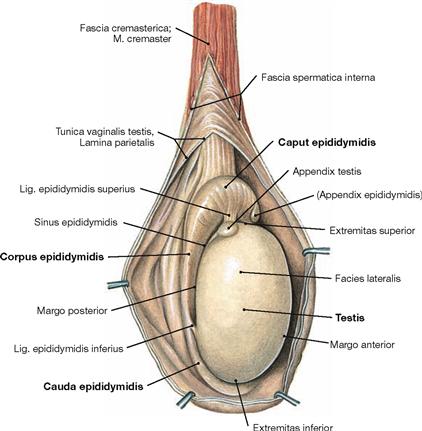

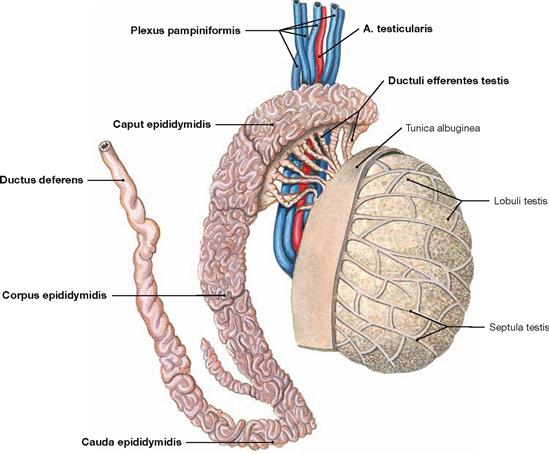

Fig. 7.48 Testis, Testis [Orchis], and epididymis, Epididymis; view from the right side.

The Testis is egg-shaped and 4 × 3 cm in size (20–30 g). It has a superior and an inferior pole (Extremitas superior and inferior). The Epididymis is located adjacent to the superior and dorsal aspect of the Testis and is attached to it by a superior and an inferior ligament (Ligg. epididymidis superius and inferius). The Epididymis has the following parts: head (Caput), body (Corpus), and tail (Cauda) which continues as vas deferens.

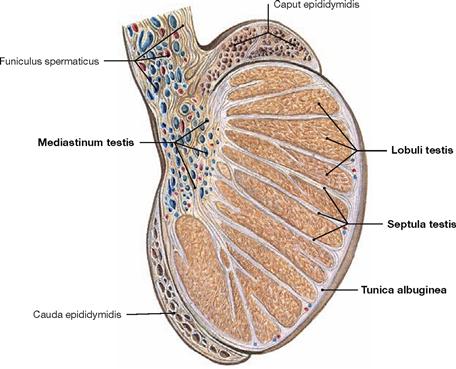

Fig. 7.49 Testis, Testis [Orchis], and epididymis, Epididymis; sagittal section; view from the right side.

The dense Tunica albuginea surrounding the Testis sends septa into the parenchyma of the Testis and, thus, subdivides the parenchyma into 370 lobules (Lobuli testis). The seminiferous tubules within these lobules are the site of sperm production. The interstitial tissue between the seminiferous tubules harbours the testosterone producing testicular LEYDIG’s cells. At the Mediastinum testis neurovascular structures enter and exit the testis and here the seminiferous tubules are connected to the head of the Epididymis.

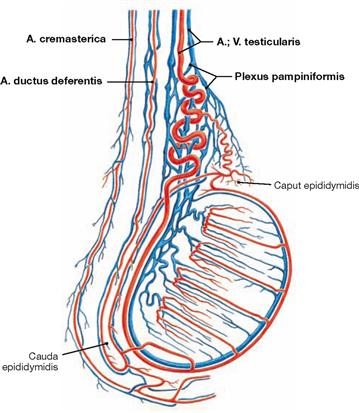

Fig. 7.50 Testis, Testis [Orchis], and epididymis, Epididymis, with blood vessels; view from the right side.

The testis is connected to the head of the Epididymis (Caput epididymis) via tiny tubules (Ductuli efferentes testis). The Epididymis itself consists of a 6 m long convoluted duct which continues as vas deferens (Ductus deferens) at the tail of the Epididymis. With a length of 35–40 cm and a thickness of 3 mm, the vas deferens is located within the spermatic cord and courses through the inguinal canal to the dorsal aspect of the urinary bladder. The terminal part of the vas deferens combines with the excretory duct of the seminal vesicle to form the Ductus ejaculatorius, which enters the Pars prostatica of the male Urethra. Testis and Epididymis are supplied by the A. testicularis and a plexus of veins (Plexus pampiniformis).

Fig. 7.51 Testis, Testis [Orchis], and epididymis, Epididymis; transverse section; cranial view.

In addition to the testicular coverings (→ Fig. 7.55), the vascular structures and the vas deferens (Ductus deferens) are sectioned.

Accessory sex glands in the male

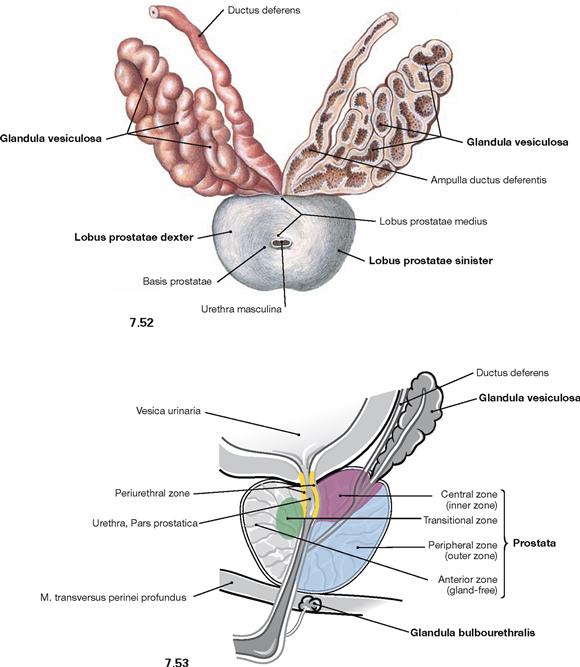

Fig. 7.52 and Fig. 7.53 Seminal vesicles, Glandulae vesiculosae, and prostate gland, Prostata; cranial view (→ Fig. 7.52) and view from the left side; median section (→ Fig. 7.53).

The accessory sex glands consist of:

• prostate gland: unpaired gland beneath the base of the bladder. The prostate gland measures 4 × 3 × 2 cm (20 g) and has a superior base and an inferior apex. It consists of a right lobe and a left lobe (Lobus dexter and Lobus sinister), demarcated by a small groove, and a middle lobe (Lobus medius). The prostate gland discharges its secretions into the centrally traversing Urethra (Pars prostatica).

• seminal vesicle (Glandula vesiculosa): paired gland at the dorsal aspect of the urinary bladder (→ Fig. 7.34). The seminal vesicles are elongated oval glands (5 × 1 × 1 cm). Their excretory ducts combine with the Ductus deferens to form the Ductus ejaculatorius and enter the Pars prostatica of the Urethra.

• COWPER’s gland (Glandula bulbourethralis): paired gland located within the perineal muscles (→ Fig. 7.35). The excretory ducts of the lentil-sized COWPER’s glands enter the Pars spongiosa of the Urethra.

Seminal vesicles and prostate gland produce the liquid component of the ejaculate which nurtures the spermatozoa. The secretion of the COWPER’s glands enters the Urethra prior to ejaculation and functions in lubrication.

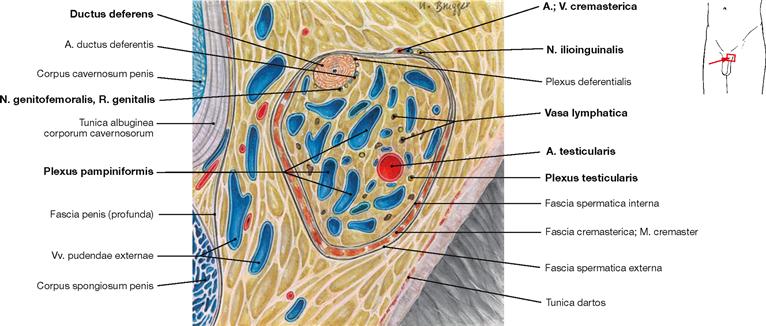

Spermatic cord

Fig. 7.54 Spermatic cord, Funiculus spermaticus, left side; frontal section; ventral view, magnification 2,5-fold.

The spermatic cord contains the following structures:

• vas deferens (Ductus deferens) with A. ductus deferentis (from the A. umbilicalis)

• A. testicularis from the abdominal aorta and the Plexus pampiniformis as accompanying veins

• N. genitofemoralis, R. genitalis (→ Fig. 7.56)

• lymph vessels (Vasa lymphatica) to the lumbar lymph nodes

• autonomic nerve fibres (Plexus testicularis) from the aortic plexus

Externally, the N. ilioinguinalis and the A. and V. cremasterica are adjacent to the spermatic cord (→ Figs. 7.55 and 7.56).

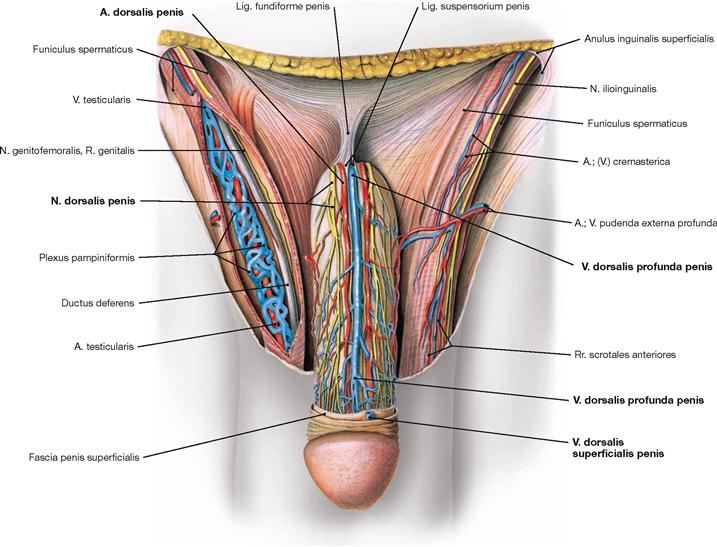

Blood vessels and nerves of the penis

Fig. 7.56 External male genitalia, Organa genitalia masculina externa, with neurovascular structures; ventral view; after removal of the fascia of the Penis.

The Penis receives its arterial blood supply from three paired arteries arising from the A. pudenda interna:

• A. dorsalis penis: subfascial course, supplies the skin of the Penis and the glans penis

• A. profunda penis: located within the Corpora cavernosa; regulates the filling of the corpora cavernosa

• A. bulbi penis: enters the Bulbus penis, supplies the Glandula bulbourethralis and as A. urethralis it supplies the Urethra and the Corpus spongiosum

The venous blood is collected by three venous systems:

• V. dorsalis superficialis penis: paired or unpaired, epifascial course, drains blood from the penile skin to the V. pudenda externa

• V. dorsalis profunda penis: unpaired, subfascial course, drains blood from the Corpora cavernosa to the Plexus venosus prostaticus

• V. bulbi penis: paired, drains blood from the Bulbus penis to the V. dorsalis profunda penis

• sensory: N. dorsalis penis (from the N. pudendus)

• autonomic: Nn. cavernosi penis (from the Plexus hypogastricus inferior) penetrate the pelvic floor and course adjacent to the N. dorsalis penis (sympathetic stimulation causes vasoconstriction; parasympathetic stimulation causes vasodilation and consecutive erection).

Fig. 7.57 Penis, Penis; cross-section at the midlevel of the penile body; ventral view.

The location of the blood vessels is important for the erection of the Penis. Following parasympathetic innervation, dilation of the A. profunda penis causes the filling of the Corpora cavernosa. These compress the V. dorsalis profunda penis beneath the tough Fascia penis and prevent venous drainage. Supported by the contraction of the Mm. ischiocavernosi (innervated by the N. pudendus), this results in penile erection.

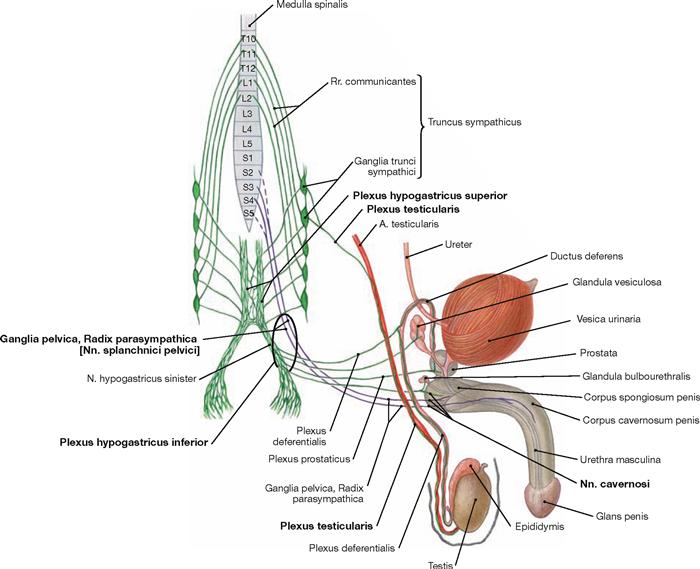

Innervation of the male genitalia

Fig. 7.60 Innervation of the male genitalia; ventral and lateral view; schematic illustration. The Plexus hypogastricus inferior contains sympathetic (green) and parasympathetic (purple) nerve fibres.

The preganglionic sympathetic fibres (T10–L2) descend from the Plexus aorticus abdominalis via the Plexus hypogastricus superior and from the sacral ganglia of the sympathetic trunk (Truncus sympathicus) via the Nn. splanchnici sacrales. They are predominantly synapsed to postganglionic sympathetic neurons in the Plexus hypogastricus inferior. These postganglionic fibres reach the pelvic viscera, including the accessory sex glands. Sympathetic fibres to the vas deferens (Plexus deferentialis) activate smooth muscle contractions for the emission of spermatozoa into the Urethra. Some fibres also join the Nn. cavernosi and penetrate the pelvic floor to reach the Corpora cavernosa of the Penis. The (mostly) postganglionic sympathetic fibres to the Testis and Epididymis course in the Plexus testicularis alongside the A. testicularis after being already synapsed in the Ganglia aorticorenalia or the Plexus hypogastricus superior.

Preganglionic parasympathetic fibres derive from the sacral division of the parasympathetic nervous system (S2–S4) via the Nn. splanchnici pelvici and reach the ganglia of the Plexus hypogastricus inferior. They are synapsed either here or in the vicinity of the pelvic organs (Ganglia pelvica) to postganglionic neurons for the accessory glands. The Nn. cavernosi penetrate the pelvic floor and course to the Corpora cavernosa (partly adjacent to the N. dorsalis penis) to induce erection upon parasympathetic stimulation.

Somatic innervation via the N. pudendus conveys sensory innervation to the Penis via the N. dorsalis penis and aids in ejaculation of spermatozoa through the motor innervation to the M. bulbospongiosus and M. ischiocavernosus via the Nn. perineales in the perineum.

Parasympathetic stimulation induces erection, while sympathetic fibres initiate the emission, and the N. pudendus is involved in ejaculation.

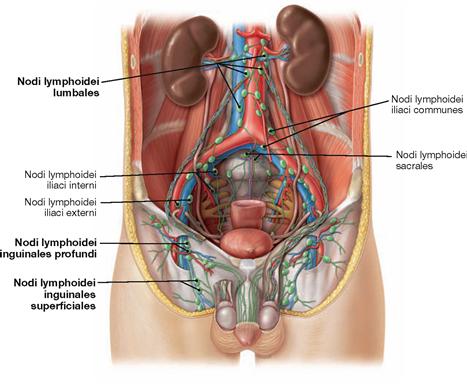

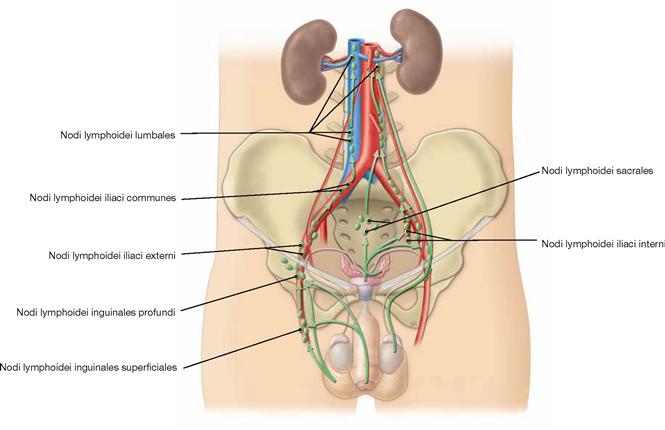

Lymph vessels of the male genitalia

Fig. 7.61 Lymph vessels and lymph nodes of the external and internal male genitalia; ventral view.

The regional lymph nodes for the external genitalia are the inguinal nodes (Nodi lymphoidei inguinales). In contrast, the first regional lymph nodes for the Testes and Epididymis are located in the retroperitoneal space at the level of the kidneys (Nodi lymphoidei lumbales).

Fig. 7.62 Lymphatic drainage pathways of the external and internal male genitalia; ventral view.

In men, external and internal genitalia have completely different lymphatic drainage pathways.

External genitalia:

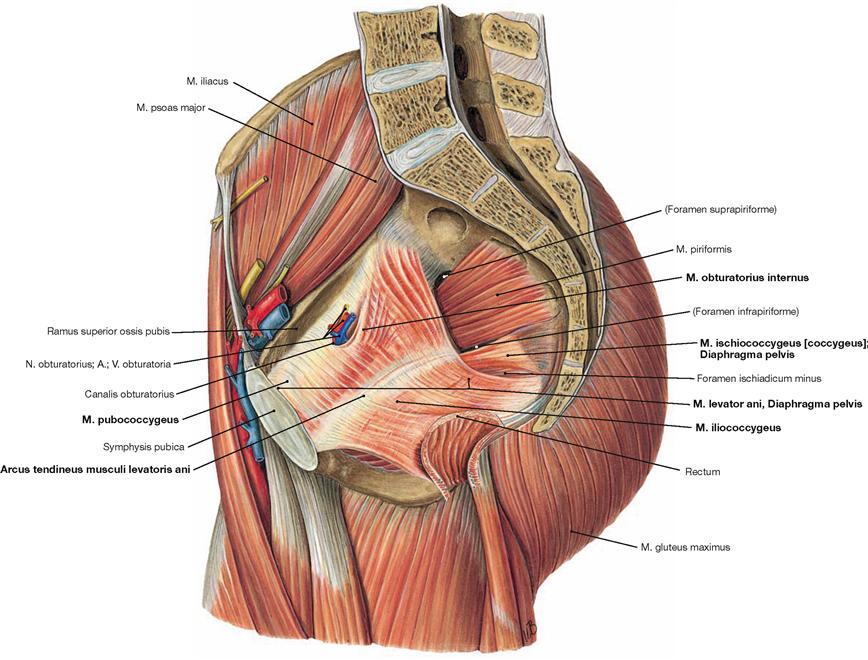

Pelvic floor in men

Fig. 7.63 Muscles of the pelvic floor, Diaphragma pelvis, thigh and hip in men; view from the left side.

The pelvic floor closes the pelvic cavity caudally.

Organisation:

In contrast to the M. pubococcygeus and the M. ischiococcygeus, the M. iliococcygeus does not originate from the Os coxae but from the Arcus tendineus musculi levatoris ani, a reinforcement of the fascia of the M. obturatorius internus.

The muscles of both sides spare the levator hiatus between them (Hiatus levatorius) (→ Fig. 7.87). This muscular gap is divided by the connective tissue of the Corpus perineale (Centrum perinei) into the anterior Hiatus urogenitalis and the posterior Hiatus analis for the passage of Urethra and Rectum, respectively.

The pelvic floor is innervated by direct branches of the Plexus sacralis (S3–S4).

Function: The pelvic floor stabilises the position of the pelvic viscera and, thus, is essential for urinary and fecal continence. Pelvic floor insufficiency with resulting incontinence is rare in men since potential injuries due to repetitive strain during childbirth is lacking.

→ T20a

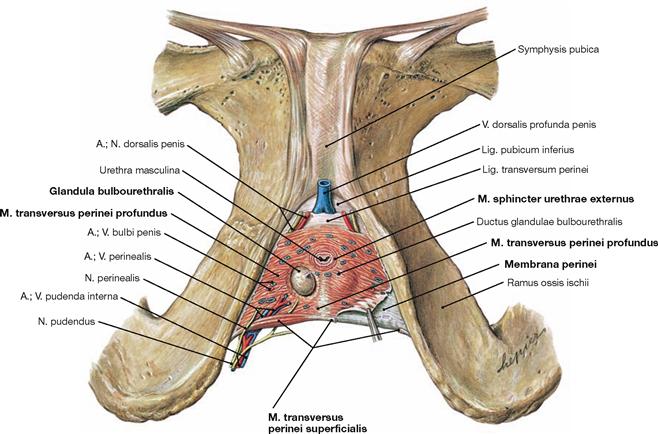

Perineal muscles in men

Fig. 7.64 Perineal muscles in men; caudal view; after removal of all other muscles.

In men, the muscular gap of the levator hiatus (Hiatus levatorius) is almost entirely closed by the perineal muscles beneath which leave only the passage for the Urethra masculina.

The perineal muscles in men comprise the strong M. transversus perinei profundus and the thin M. transversus perinei superficialis located at its posterior margin. These muscles have formerly been referred to as “Diaphragma urogenitale” analogous to the Diaphragma pelvis. Since a true diaphragm does not exist and because a similar muscular plate is missing in women, this term is not used any more.

The voluntary sphincter muscle of the urinary bladder, the M. sphincter urethrae externus, is a part of the M. transversus perinei profundus.

The M. transversus perinei profundus is covered by a fascia on both sides. The stronger inferior fascia is referred to as perineal membrane (Membrana perinei).

The space between both fascias is the deep perineal space (Spatium profundum perinei) and is entirely occupied by the M. transversus perinei profundus. This space also contains the Urethra and the COWPER’s glands (Glandulae bulbourethrales) and is traversed by deep branches of the N. pudendus as well as the A. and V. pudenda interna before they reach the Radix penis.

The superficial perineal space (Spatium superficiale perinei) lies caudal to the perineal membrane and contains amongst others the M. transversus perinei superficialis.

→ T20b

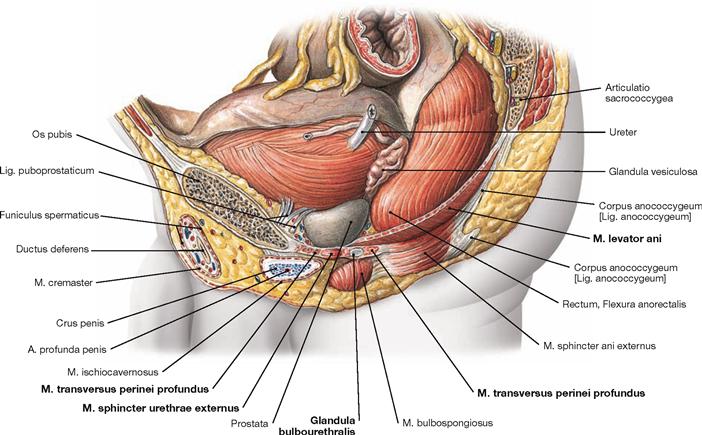

Pelvic floor and perineal muscles in men

Fig. 7.65 Pelvic floor, Diaphragma pelvis, and perineal muscles in men; view from the left side.

At its anterior and posterior aspect, the pelvic floor consists of the M. levator ani and the M. ischiococcygeus, respectively. Located beneath the pelvic floor is the deep perineal muscle (M. transversus perinei profundus). A partition of the latter, the M. sphincter urethrae externus, functions as sphincter of the urinary bladder. Embedded within the M. transversus perinei profundus are the COWPER‘s glands.

→ T20

Perineal region in men

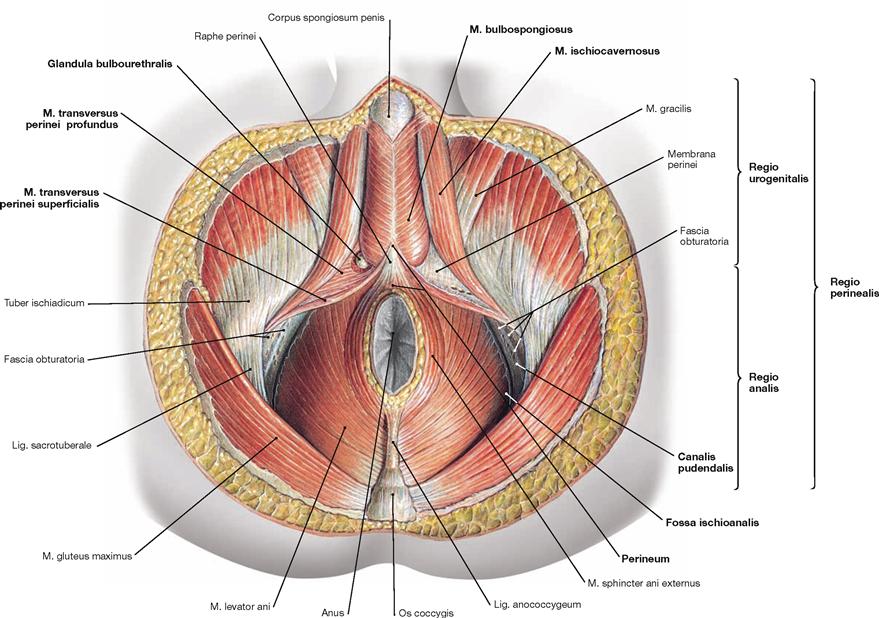

Fig. 7.66 Perineal region, Regio perinealis, in men; caudal view; after removal of all neurovascular structures.

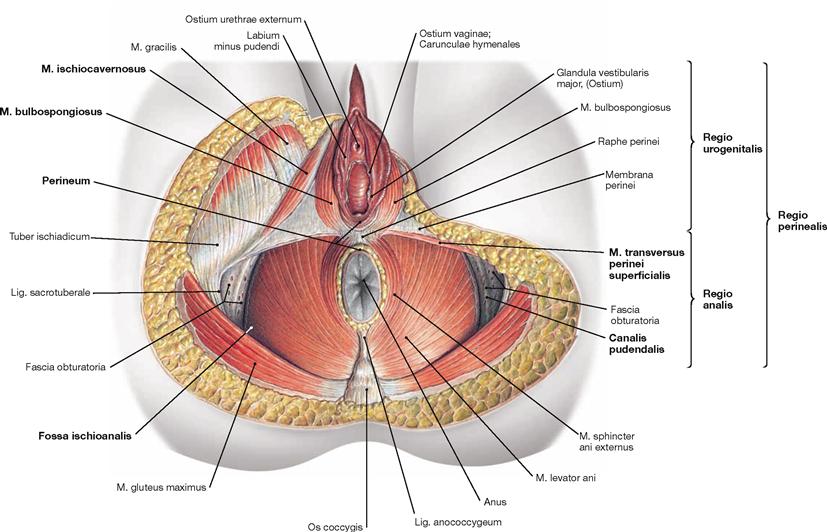

The perineal region extends from the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis (Symphysis pubica) to the tip of the coccyx (Os coccygis). The term perineum in men, however, exclusively describes the small connective tissue bridge between the Radix penis and the Anus. The perineal region is subdivided into the anterior Regio urogenitalis (urogenital triangle), containing the external genitalia and the Urethra, and the posterior Regio analis (anal triangle) around the Anus. The following spaces can be found within these triangles:

• The Regio analis contains the Fossa ischioanalis (→ Table), which constitutes a pyramid-shaped space on both sides of the Anus. The cranial border is the M. levator ani of the pelvic floor. The lateral wall encloses the fascial duplicature of the M. obturatorius internus (Fascia obturatoria), the pudendal canal (ALCOCK’s canal). The pudendal canal contains the A. and V. pudenda interna, and the N. pudendus after their passage from the gluteal region through the Foramen ischiadicum minus.

The Regio urogenitalis has two perineal spaces:

• The deep perineal space (Spatium profundum perinei) comprises the M. transversus perinei profundus and the COWPER‘s glands (Glandulae bulbourethrales).

• The superficial perineal space (Spatium superficiale perinei) comprises the M. transversus perinei superficialis, the M. bulbospongiosus, and the M. ischiocavernosus, which stabilise the cavernous bodies of the Radix penis and enable ejaculation.

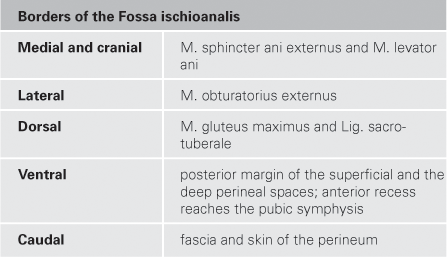

Fig. 7.67 Blood vessels and nerves of the perineal region, Regio perinealis, in men; caudal view.

Covered by a fascial duplicature of the M. obturatorius internus, the Canalis pudendalis (ALCOCK’s canal), the neurovascular structures enter the Fossa ischioanalis from a dorsolateral direction. The pyramid-shaped fossa is filled with adipose tissue. Branches to the Anus and the anal canal come off first and cross the ischio-anal fossa to reach the anus. The neurovascular structures then continue ventrally to the Radix penis and the two perineal spaces.

Contents of the Fossa ischioanalis:

Perineal spaces in men

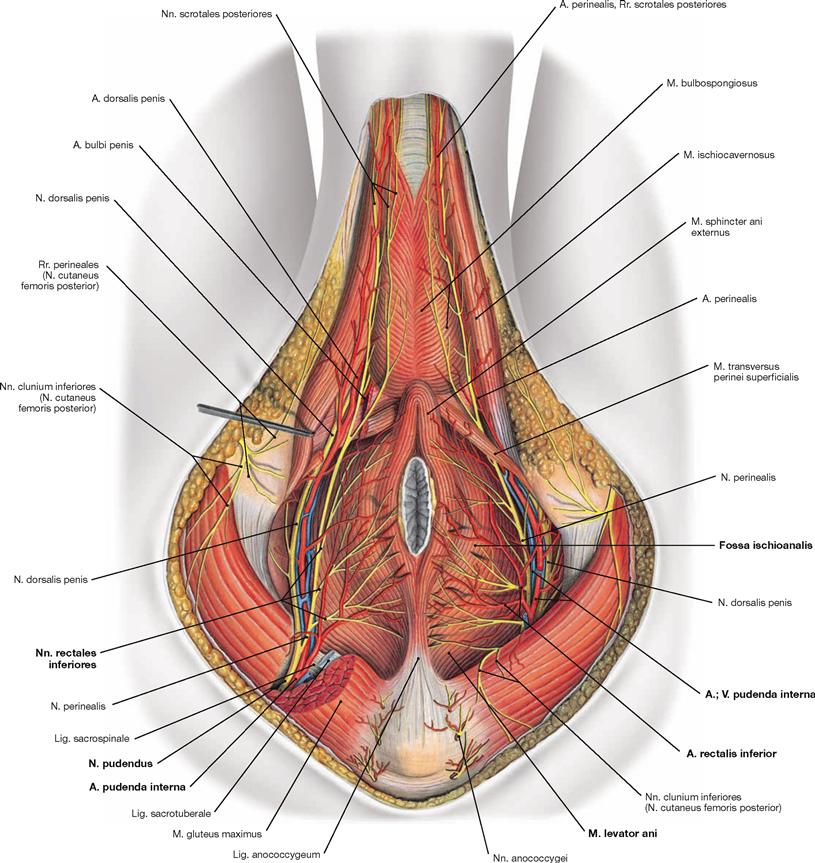

Fig. 7.68 Perineal spaces in men; left side; frontal section at the level of the femoral head; dorsal view.

The frontal section shows three levels of the male pelvis:

• peritoneal cavity of the pelvis (Cavitas peritonealis pelvis), caudally bordered by the parietal peritoneum

• subperitoneal space (Spatium extraperitoneale pelvis), caudally bordered by the M. levator ani of the pelvic floor

• perineal region (Regio perinealis) inferior to the pelvic floor. The anterior portion contains the two perineal spaces, and includes the variably expanded anterior recess of the ischio-anal fossa (illustrated here in different ways for the right side and the left side).

The deep perineal space (Spatium profundum perinei) consists of the M. transversus perinei profundus. It also contains the COWPER’s glands (Glandulae bulbourethrales) and the passage of the Urethra (Urethra masculina). It is traversed by the deep branches of the N. pudendus (N. dorsalis penis), and the A. and V. pudenda interna (A. bulbi penis, A. dorsalis penis, A. profunda penis) before reaching the Radix penis. The Nn. cavernosi penis pierce the perineum and enter the Corpora cavernosa of the Penis.

The superficial perineal space (Spatium superficiale perinei) is located between the perineal membrane (Membrana perinei) at the underside of the M. transversus perinei profundus and the body fascia (Fascia perinei). It contains the M. transversus perinei superficialis and the proximal parts of the Corpora cavernosa of the Penis. The Bulbus penis is ensheathed by the M. bulbospongiosus, the Crura penis by the M. ischiocavernosus. The superficial branches of the N. pudendus (N. perinealis with Nn. scrotales posteriores) and the A. and V. pudenda interna (A. perinealis with Rr. scrotales posteriores) also traverse this space to reach the Scrotum.

External female genitalia

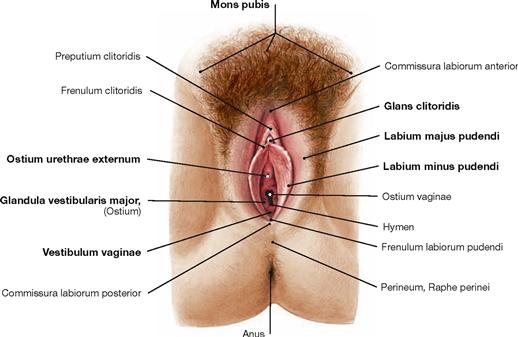

Fig. 7.69 External female genitalia, Organa genitalia feminina externa; caudal view.

The female genitalia can be categorised into external genitalia (Organa genitalia feminina externa) and internal genitalia (Organa genitalia feminina interna → Fig. 7.71).

The external genitalia are referred to as Vulva and comprise:

The vestibule extends to the hymen at the vaginal orifice (Ostium vaginae). Ventral thereof is the external urethral orifice (Ostium urethrae externum).

The external genitalia are the sex organs and serve for intercourse.

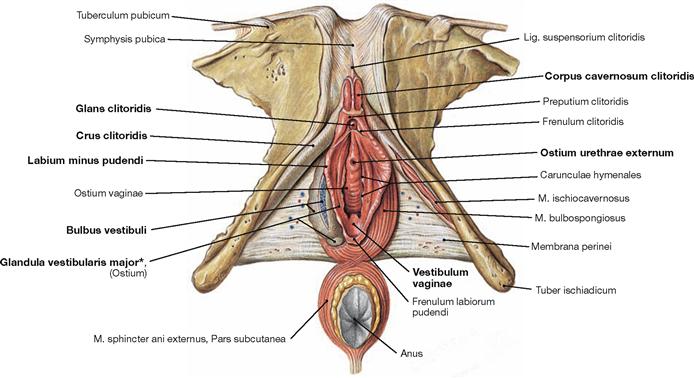

Fig. 7.70 External female genitalia, Organa genitalia feminina externa; caudal view; after removal of body fascia and neurovascular structures.

The Labia majora pudendi are removed in this illustration. They contain the cavernous body of the vestibule (Bulbus vestibuli). The Labia minora pudendi surround the vestibule (Vestibulum vaginae) and continue anteriorly as Frenulum clitoridis to the glans of the clitoris (Glans clitoridis). The vestibular glands (Glandulae vestibulares majores [BARTHOLIN’s glands] and minores) enter the vestibule from lateral. The Clitoris is the sensory organ for sexual arousal. The Corpora cavernosa clitoridis form a short body (Corpus clitoridis) with the glans at the inferior end. The crura of the clitoris (Crura clitoridis) are attached to the inferior ischiopubic rami and covered by the M. ischiocavernosus on both sides. The M. bulbospongiosus stabilises the bulb of the vestibule.

Developmentally, the organisation of the Penis and the Clitoris is similar including the presence of the prepuce (Preputium clitoridis). The filling mechanisms of the cavernous bodies and the process of erection are also similar in both sexes.

* clinical term: BARTHOLIN’s gland

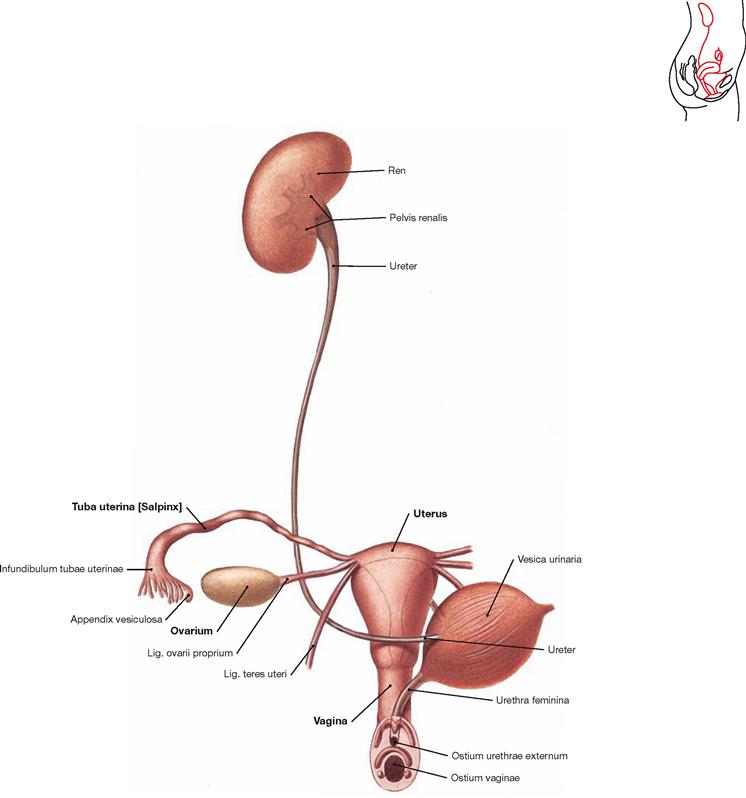

Internal female genitalia

Fig. 7.71 Female urinary and genital organs, Organa urogenitalia feminina; ventral view.

The internal genitalia comprise:

Uterine tube and ovary are paired organs and are collectively referred to as uterine adnexa.

The internal genitalia in women are reproductive and sex organs. Functionally, the ovary serves for the maturation of follicles (and ova) and the production of female sex hormones (oestrogens and progesterone). The uterine tube provides the place for the fertilisation of ova and transports the zygote to the Uterus where the embryo/fetus develops and grows during pregnancy. The Vagina serves the sexual intercourse and is part of the birth canal.

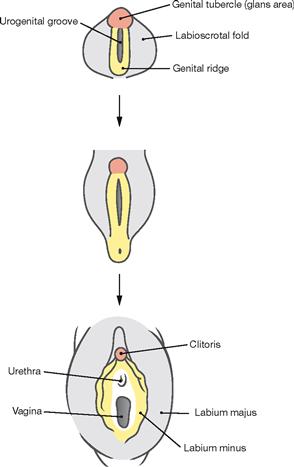

Development of the external female genitalia

Fig. 7.72 Development of the external female genitalia, Organa genitalia feminina externa.

The external genitalia develop from the caudal part of the Sinus urogenitalis. The Sinus urogenitalis develops from the cloaca of the hindgut and gives rise to the urinary bladder and parts of the Urethra (→ Fig. 7.6). Contributing to these structures are also the ectoderm and the connective tissue (mesenchyme) located beneath the Sinus urogenitalis. First, the external genitalia develop identically in both sexes (indifferent gonad). The anterior wall of the Sinus urogenitalis indents to form the urethral groove, and is bordered on both sides by the urethral folds. Lateral of those are the labioscrotal folds and anterior the genital tubercle. Subsequently, the genital tubercle develops into the Clitoris (Corpora cavernosa) under the influence of the female sex hormone oestrogen which is produced in the ovary. In contrast to the development in men, the genital folds and the labioscrotal folds do not merge. The genital folds develop into the Labia minora and the labioscrotal folds into the Labia majora. The short female Urethra and the BARTHOLIN’s glands develop from the Sinus urogenitalis.

Development of the internal female genitalia

Fig. 7.73 Development of the internal female genitalia, Organa genitalia feminina interna. (according to [1])

The internal genitalia develop identically in both sexes up to week 7 (sexual indifferent stage, → Fig. 7.8). In the female, the primordium of the primitive gonad then develops into the ovary. Similar to the Testis, the ovary also develops in the lumbar region at the level of the mesonephros. Due to the longitudinal growth of the body the ovary is then relocated caudally to the lesser pelvis without leaving the peritoneal cavity. Thus, ovary and uterine tube have an intraperitoneal position.

Without the suppressing effects of the anti-MÜLLERIAN hormone from the Testis, the MÜLLERIAN ducts differentiate into female genitalia. Beginning in week 12, the MÜLLERIAN ducts form the uterine tube. Their distal portions merge and give rise to the Uterus and the upper Vagina. The lower Vagina develops from the Sinus urogenitalis. If the MÜLLERIAN ducts fail to fuse, a septate uterus (Uterus septus or subseptus) or a double uterus (Uterus duplex, Uterus didelphys) may result.

Uterus, uterine tube and ovary

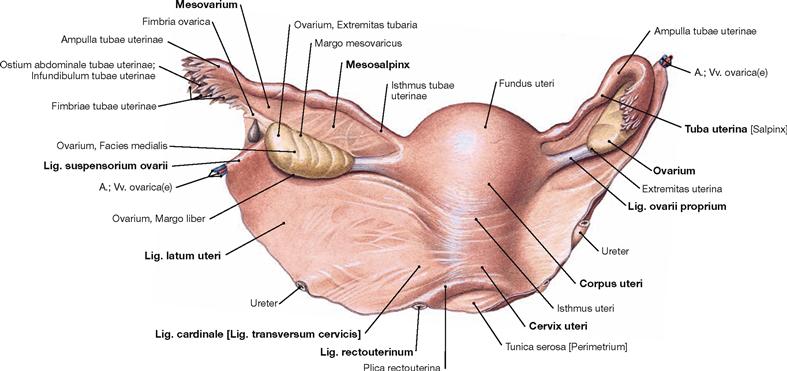

Fig. 7.74 Uterus, Uterus, ovary, Ovarium, and uterine tube, Tuba uterina, with peritoneal duplications; dorsal view.

The Uterus (Metra) is 8 cm long, 5 cm wide and 2–3 cm thick. It consists of the body (Corpus uteri) with a superior fundus (Fundus uteri) and a neck (Cervix uteri). A constriction (Isthmus uteri) marks the transition between body and neck of the Uterus. The uterine tube (Tuba uterina) extends on both sides from the uterine body to connect to the ovaries.

The uterine tube (Tuba uterina) is 10 – 14 cm long and has several parts:

• Infundibulum tubae uterinae: 1 – 2 cm long, contains the opening to the peritoneal cavity (Ostium abdominale tubae uterinae) and the fimbriae (Fimbriae tubae uterinae) for the collection of ovulated ova.

• Ampulla tubae uterinae: 7 – 8 cm long, crescent-shaped around the ovary

• Isthmus tubae uterinae: 3 – 6 cm long, constriction at the transition to the Uterus

• intramural part (Pars uterina tubae), enters the Uterus (Ostium uterinum)

The ovary (Ovarium) is 3 × 1.5 × 1 cm in size and oval. A tubal extremity (Extremitas tubaria) and an uterine extremity (Extremitas uterina) are distinguished. The mesovarium is attached to the anterior margin (Margo mesovaricus), but the posterior margin is loose (Margo liber).

Uterus, uterine tube, and ovary have an intraperitoneal position and thus, have individual peritoneal duplicatures covered by a Tunica serosa. The following ligaments and attachments are relevant for gynaecological surgical procedures:

• Lig. latum uteri: broad ligament as frontal peritoneal fold

• Mesovar and Mesosalpinx: peritoneal duplicatures of ovary and uterine tube, respectively, connected to the Lig. latum

• Lig. cardinale (Lig. transversum cervicis): connective tissue connecting the Cervix to the lateral pelvic wall

• Lig. rectouterinum (clinical term: Lig. sacrouterinum): connective tissue attaching the Cervix dorsally

• Lig. teres uteri (clinical term: Lig. rotundum): the round ligament coursing from the uterotubal junction through the inguinal canal to the Labia majora

• Lig. ovarii proprium: the ovarian ligament connects ovary and Uterus

• Lig. suspensorium ovarii (clinical term: Lig. infundibulopelvicum): connects ovary and lateral pelvic wall, carries the A. and V. ovarica

Uterus and vagina

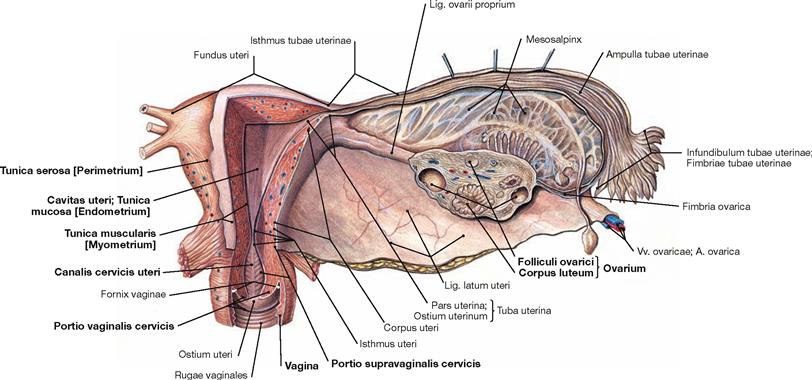

Fig. 7.75 Uterus, Uterus, vagina, Vagina, ovary, Ovarium, and uterine tube, Tuba uterina; frontal section; dorsal view.

The space inside the Uterus is divided into the Cavitas uteri in the body and the Canalis cervicis uteri in the uterine cervix. The lower portion of the Cervix enters the Vagina and is referred to as Portio vaginalis cervicis. The upper portion is the Portio supravaginalis cervicis. The Vagina is a hollow muscular organ of about 10 cm length in a subperitoneal location. The Fornix vaginae surrounds the Portio vaginalis cervicis. At the inner surface, both the anterior and posterior walls (Paries anterior and Paries posterior) of the Vagina reveal transverse mucosal folds (Rugae vaginales).

The frontal section also shows the structure of the uterine wall: the internal mucosal layer (Tunica mucosa; endometrium), then the strong muscular layer (Tunica muscularis; myometrium) of smooth muscles, and the outermost peritoneal lining (Tunica serosa; perimetrium).

Embedded in the stroma of the ovary are the ovarian follicles (Folliculi ovarici) which contain the ova and develop into the Corpus luteum following ovulation. Follicles and Corpora lutea produce the female sex hormones (oestrogens and progesterone) which regulate the cycle-dependent differentiation of the endometrium.

Position of the uterus and adnexa

Fig. 7.76 Uterus, Uterus, ovary, Ovarium, and uterine tube, Tuba uterina, with peritoneal duplicatures; ventral view.

Uterus, uterine tubes, and ovary have an intraperitoneal position. Their peritoneal duplicatures (Lig. latum uteri, Mesosalpinx, Mesovarium) form a transverse fold in the lesser pelvis. The Lig. teres uteri reaches ventral from the uterotubal junction to the lateral wall of the lesser pelvis and traverses the inguinal canal to merge with the connective tissue of the Labia majora. The Lig. ovarii proprium connects Uterus and ovary. The Lig. suspensorium ovarii connects ovary and lateral pelvic wall and contains the A. and V. ovarica.

The close topographical relationship between the adnexa (ovary and uterine tube) and the Appendix vermiformis of the Colon explain why inflammations of the appendix (appendicitis) as well as those of the uterine tube (salpingitis) may cause similar pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant. The peritoneal pouch between the Uterus and the urinary bladder is called Excavatio vesicouterina. The Excavatio rectouterina (pouch of DOUGLAS) behind the Uterus is the most caudal extension of the peritoneal cavity in women and may collect fluids and pus in cases of inflammatory processes in the lower abdomen.

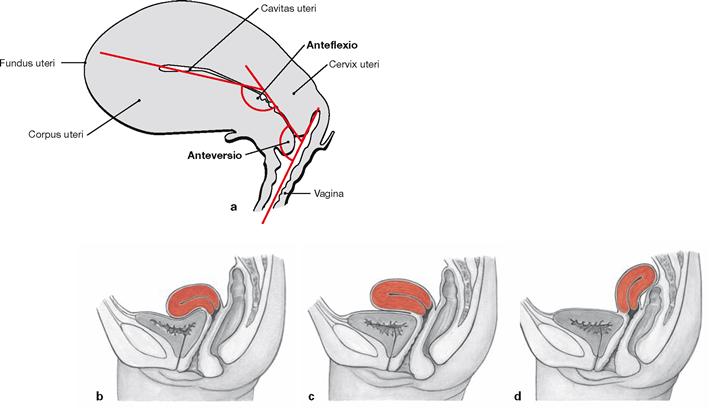

Figs. 7.77a to d Position of uterus, Uterus, and vagina, Vagina; view from the right side.

a. Normally, the Uterus is angled in its ventral aspect in relation to the Vagina (anteversion) and the body is tilted anteriorly in relation to the neck (anteflexion). This position prevents a prolapse of the Uterus through the Vagina during increased intra-abdominal pressure (coughing, sneezing).

b. anteversion, anteflexion = normal position

Position of the uterus and connective tissue spaces

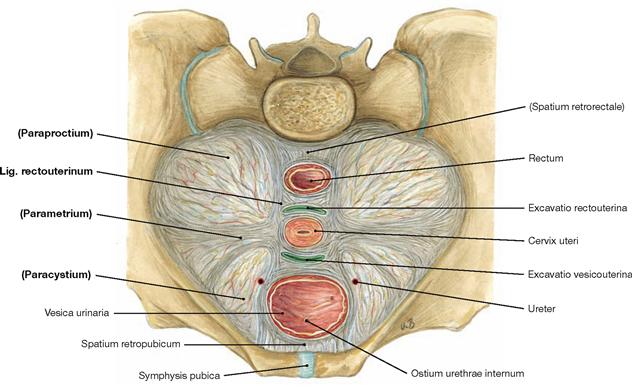

Fig. 7.78 Ligaments and connective tissue spaces of the uterus, Uterus; transverse section at the level of the Cervix uteri; caudal view; semischematic illustration.

The connective tissue in the lesser pelvis is categorised according to the relation to adjacent organs. Some of the connective tissue strands are referred to as ligaments in clinical terms although an anatomical demarcation is not possible.

• parametrium: connective tissue from the cervix to the pelvic wall (Lig. cardinale)

• paraproctium: connective tissue around the Rectum

The Lig. rectouterinum between the Cervix uteri and the dorsal pelvic wall is the only separable ligament and is preserved during gynaecological surgery to protect the autonomic nerves of the Plexus hypogastricus inferior.

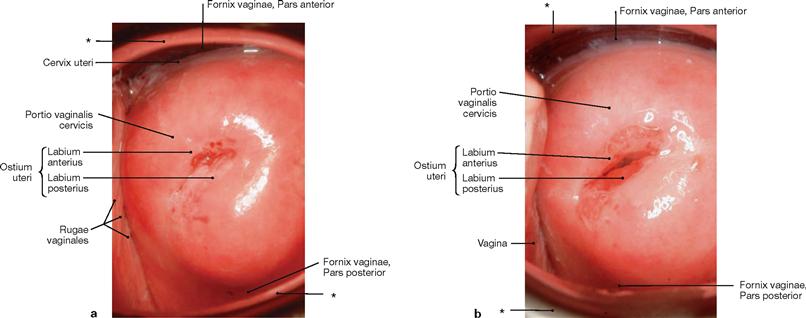

Figs. 7.79 a and b Uterine neck, Portio vaginalis cervicis; caudal view.

a. uterine neck of a young woman who has not yet delivered a child (nullipara)

b. uterine neck of a young woman who has delivered two children

For the inspection of the Portio vaginalis cervicis the Vagina is distended by two specula.

* speculum

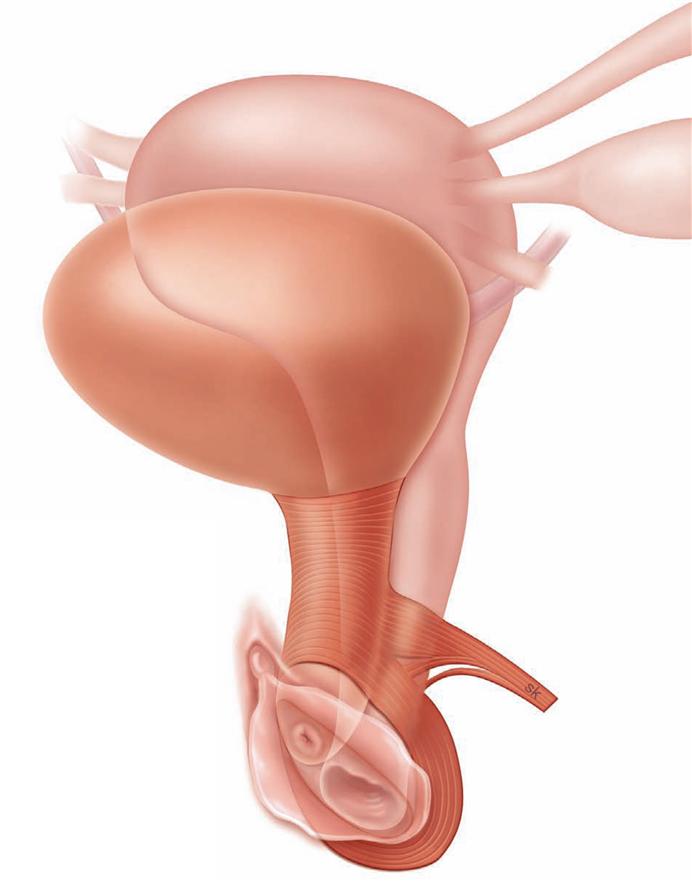

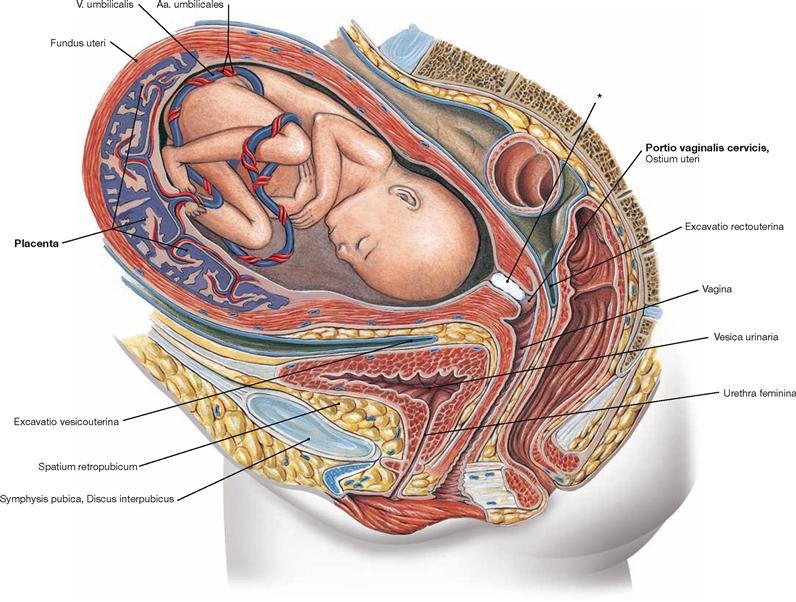

Uterus in pregnancy

Fig. 7.80 Uterus, Uterus with placenta, Placenta, and fetus; median section of the pelvis except for the fetus; view from the left side.

The developing child in the Uterus is nourished via the Placenta which develops from maternal and fetal tissues after implantation. The Cervix uteri is closed during pregnancy by the KRISTELLER’s mucous plug (*).

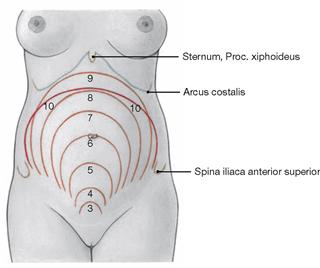

Fig. 7.81 Level of the Fundus uteri during pregnancy; ventral view.

The numbers represent the end of the respective month of pregnancy. In the 6th month (week 24) the Fundus uteri is at the level of the umbilical region, in the 9th month (week 36) at the costal margin. Up to parturition, the uterine volume increases 800 – 1200 times and the uterine weight increases from 30 – 120 g to 1000 – 1500 g.

Arteries of the internal female genitalia

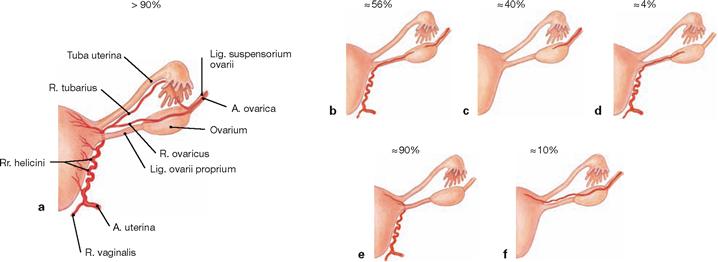

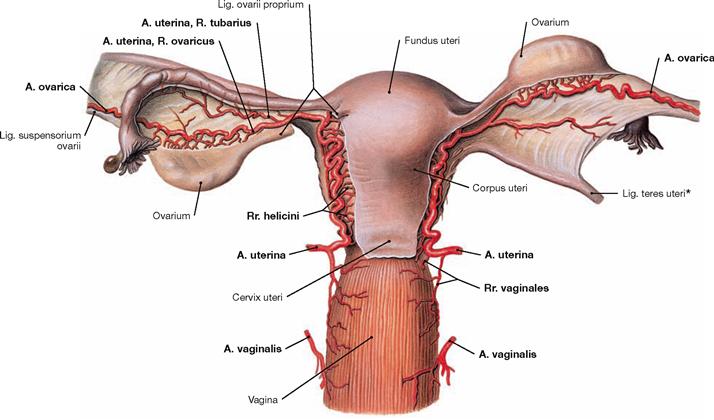

Fig. 7.82 Arteries of the internal female genitalia; dorsal view.

The internal female genitalia are supplied by three paired arteries:

• Uterus: A. uterina (from the A. iliaca interna) with Rr. helicini

• Ovarium: A. ovarica (from the abdominal aorta) and A. uterina with R. ovaricus

• Tuba uterina: A. uterina with R. tubarius and A. ovarica

• Vagina: A. vaginalis (from the A. iliaca interna) and A. uterina with Rr. vaginales

Innervation of the female genitalia

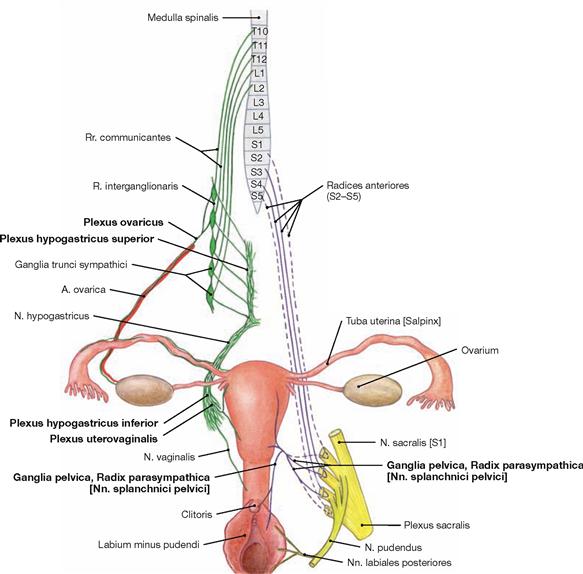

Fig. 7.84 Innervation of the female genitalia; ventral view; schematic illustration. Plexus hypogastricus inferior and Plexus uterovaginalis contain sympathetic (green) and parasympathetic (purple) nerve fibres.

Preganglionic sympathetic nerve fibres (T10 – L2) descend from the Plexus aorticus abdominalis via the Plexus hypogastricus superior and from the sacral ganglia of the sympathetic trunk (Truncus sympathicus) via the Nn. splanchnici sacrales to be synapsed to postganglionic neurons in the ganglia of the Plexus hypogastricus inferior. Axons of the postganglionic neurons continue to the pelvic target organs and reach the Plexus uterovaginalis (FRANKENHÄUSER’s plexus) for the innervation of Uterus, Tuba uterina, and Vagina. The (predominantly) postganglionic sympathetic nerve fibres to the ovary have already been synapsed in the Ganglia aorticorenalia or in the Plexus hypogastricus superior and descend within the Plexus ovaricus alongside the A. ovarica.

Preganglionic parasympathetic nerve fibres derive from the sacral parasympathetic division (S2–S4) and reach the ganglia of the Plexus hypogastricus inferior via the Nn. splanchnici pelvici. They are synapsed to postganglionic neurons either here or in close vicinity to the pelvic viscera (Ganglia pelvica) to innervate the Uterus, Tuba uterina and Vagina.

Somatic innervation by the N. pudendus conveys sensory innervation to the lower part of the Vagina and the Labia minora and majora via the Rr. labiales posteriores and to the Clitoris via the N. dorsalis clitoridis.

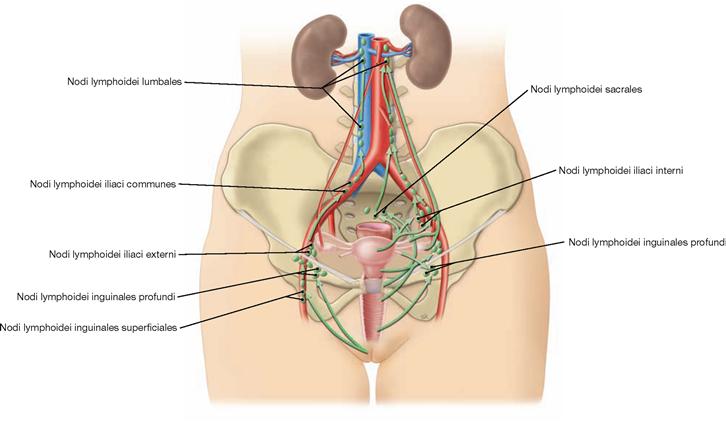

Lymph vessels of the female genitalia

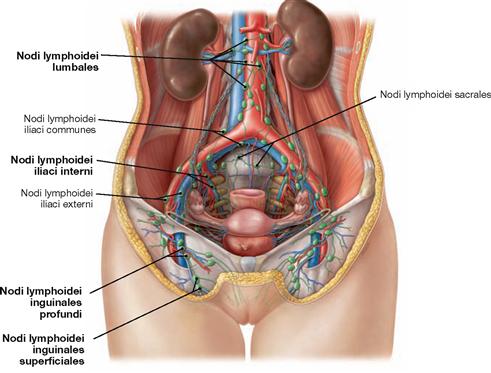

Fig. 7.85 Lymph vessels and lymph nodes of the external and internal female genitalia; ventral view.

The regional lymph nodes for the external female genitalia are the inguinal nodes (Nodi lymphoidei inguinales). In contrast, the first regional lymph node station of the ovary is located retroperitoneally at the level of the kidneys (Nodi lymphoidei lumbales) and the regional lymph nodes of the Uterus are in the lesser pelvis (Nodi lymphoidei iliaci interni).

Fig. 7.86 Lymphatic drainage pathways of the external and internal female genitalia; ventral view.

Unlike the situation in men, the lymphatic drainage pathways of the external and internal female genitalia are not completely separate, and parts of the lymph of the internal genitalia also drain into the inguinal lymph nodes.

External genitalia:

• Nodi lymphoidei lumbales at the level of the kidneys: Ovarium, Tuba uterina, Uterus (uterotubal junction), lymphatic vessels within the Lig. suspensorium ovarii

• Nodi lymphoidei iliaci interni/externi and Nodi lymphoidei sacrales: Uterus, Vagina, Tuba uterina

• Nodi lymphoidei inguinales: lower Vagina, Uterus (uterotubal junction), lymph vessels within the Lig. teres uteri

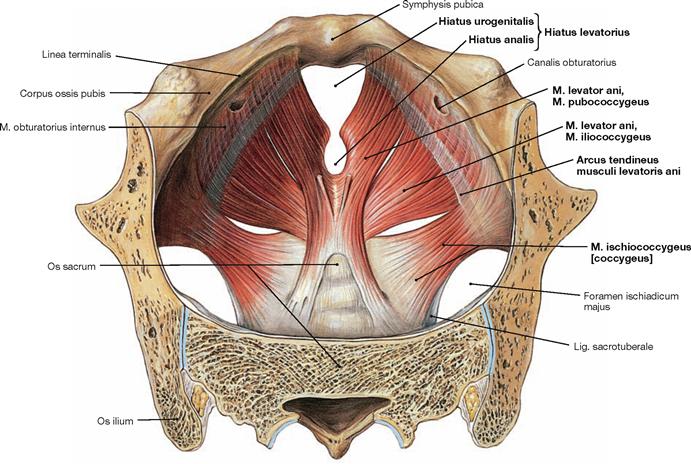

Pelvic floor in women

Fig. 7.87 Pelvic floor, Diaphragma pelvis, in women; cranial view.

The organisation of the pelvic floor in women is similar to men. The pelvic floor closes the pelvic cavity caudally.

Organisation:

In contrast to the M. pubococcygeus and M. ischiococcygeus, the M. iliococcygeus does not originate from the bone of the hip but from the Arcus tendineus musculi levatoris ani, a reinforcement of the fascia of the M. obturatorius internus.

The muscles of both sides spare the levator hiatus between them (Hiatus levatorius) This muscular gap is subdivided by the connective tissue of the perineum (Centrum perinei) into the anterior Hiatus urogenitalis for the passage of Urethra and Vagina and the posterior Hiatus analis for the passage of the Rectum.

The pelvic floor is innervated by direct branches of the Plexus sacralis (S3–S4).

Function: The pelvic floor stabilises the position of the pelvic viscera and, thus, is essential for urinary and faecal continence.

→ T20a

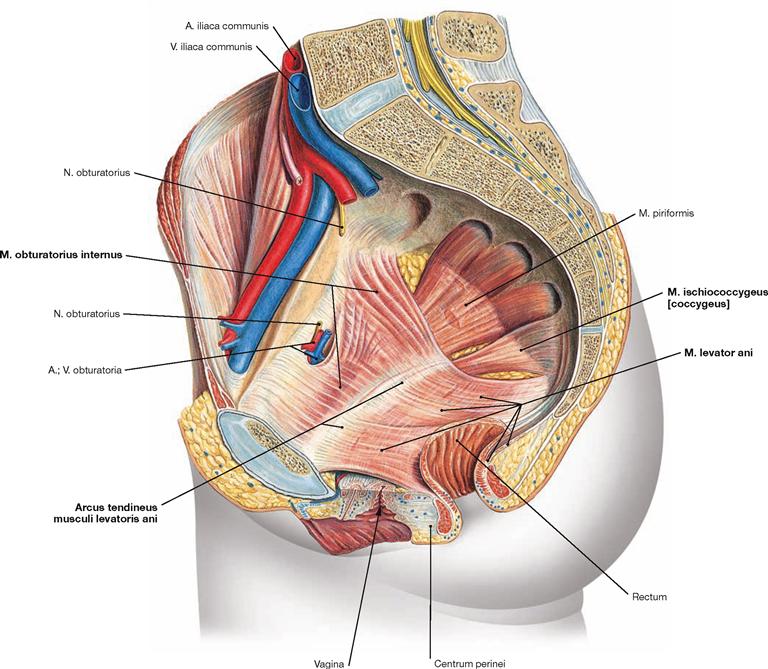

Fig. 7.88 Pelvic floor, Diaphragma pelvis, in women; view from the left side.

The pelvic floor consists of the M. levator ani and the M. ischiococcygeus. The M. iliococcygeus of the M. levator ani originates from the Arcus tendineus musculi levatoris ani. The latter is a reinforcement of the fascia of the M. obturatorius internus. One of the origins of the M. obturatorius internus is the superior pubic ramus where it is pierced by the Canalis obturatorius with the A. and V. obturatoria and the N. obturatorius. The M. obturatorius internus then exits the pelvis laterally through the Foramen ischiadicum minus. The M. levator ani extends to the sacrum and the coccyx and closes the pelvic cavity caudally.

→ T20a

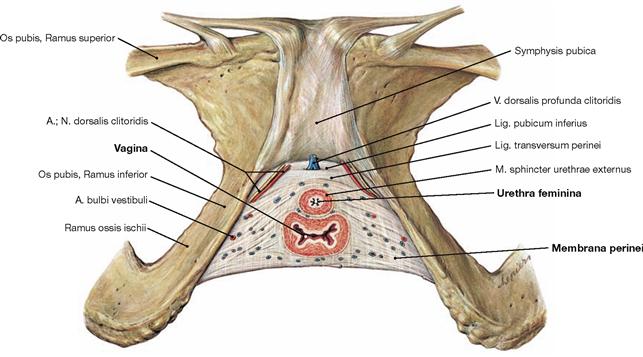

Perineal muscles in women

Fig. 7.89 Perineal muscles in women; caudal view; after removal of all other muscles.

In women, the muscular gap of the levator hiatus (Hiatus levatorius) is almost entirely closed by connective tissue which leaves only the passage for the Vagina and the Urethra feminina. Unlike in men, the perineal muscles in women are weak (→ Fig. 7.64). The weak M. transversus perinei profundus, which only consists of single muscle fibres embedded within connective tissue (→ Fig. 7.90), and the M. transversus perinei superficialis do not form a muscular plate. Therefore, the term “Diaphragma urogenitale” is not used anymore.

While in men the deep perineal space (Spatium profundum perinei) is filled with the M. transversus perinei profundus, the separation of the

perineal spaces is more difficult in women. However, similar to men the female deep perineal space is confined inferiorly by the perineal membrane (Membrana perinei). In addition, it contains the Vagina and the Urethra and is traversed by deep branches of the N. pudendus and A. and V. pudenda interna before they reach the Vulva.

The superficial perineal space (Spatium superficiale perinei) is located caudal to the perineal membrane and, amongst others, contains the M. transversus perinei superficialis.

Fig. 7.90 Voluntary sphincter muscles of the urinary bladder.

The M. transversus perinei profundus in women does not form a continuous muscular plate. Instead, individual striated muscle fibres around the Urethra form the M. sphincter urethrae externus which constitutes the voluntary sphincter muscle of the urinary bladder (→ Fig. 7.89). Some distal fibres continue to surround the distal Vagina and are referred to as M. sphincter urethrovaginalis.

→ T20b

Perineal region in women

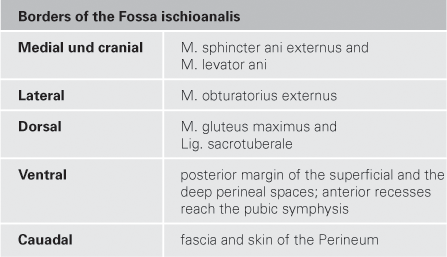

Fig. 7.91 Perineal region, Regio perinealis, in women; caudal view; after removal of all neurovascular structures.

The perineal region reaches from the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis (Symphysis pubica) to the tip of the coccyx (Os coccygis). The term perineum in women, however, describes exclusively the small connective tissue bridge between the posterior margin of the Labia majora and the Anus. The perineal region is subdivided into the anterior Regio urogenitalis (urogenital triangle) containing the external genitalia and the Urethra and the posterior Regio analis (anal triangle) around the Anus. The following spaces can be found within these triangles:

• The Regio analis contains the Fossa ischioanalis (→ Table) which constitutes a pyramid-shaped space on both sides of the Anus. The Fossa ischioanalis is similar in men and women. The lateral wall contains in a fascial duplicature of the M. obturatorius internus (Fascia obturatoria) the pudendal canal (ALCOCK’s canal). The pudendal canal harbours the A. and V. pudenda interna, and the N. pudendus after their passage from the gluteal region through the Foramen ischiadicum minus.

• The Regio urogenitalis has two perineal spaces:

– The deep perineal space (Spatium profundum perinei) is bordered inferiorly by the perineal membrane (Membrana perinei) and, in women, contains the weak M. transversus perinei profundus and the M. sphincter urethrae externus.

– The superficial perineal space (Spatium superficiale perinei) between the Membrana perinei and the body fascia (Fascia perinei) contains the M. transversus perinei superficialis, the M. bulbospongiosus, the M. ischiocavernosus. These three muscles stabilise the cavernous bodies of vestibule and Clitoris.

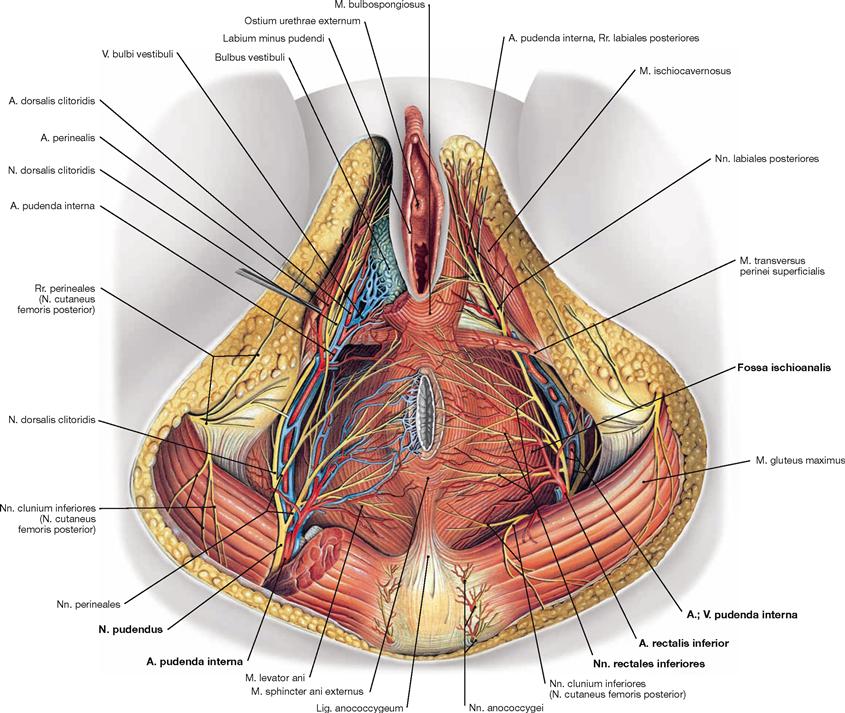

Perineal spaces in women

Fig. 7.92 Blood vessels and nerves of the perineal region, Regio perinealis, in women; caudal view.

The Fossa ischioanalis has a very similar anatomy in men and women. The pyramid-shaped fossa is filled with adipose tissue. Covered by a fascial duplicature of the M. obturatorius internus, the Canalis pudendalis (ALCOCK’s canal), the neurovascular structures enter the Fossa ischioanalis from dorsolateral. At first branches to the Anus and the anal canal exit and cross the ischio-anal fossa to reach the Anus. The neurovascular structures then continue ventrally to the Vulva and the two perineal spaces.

Contents of the Fossa ischioanalis:

Fig. 7.93 Perineal spaces in women; median section, and frontal section on the right side; ventral view.

The frontal section shows three levels of the female pelvis:

• peritoneal cavity of the pelvis (Cavitas peritonealis pelvis) bordered caudally by the parietal peritoneum

• subperitoneal space (Spatium extraperitoneale pelvis), caudally bordered by the M. levator ani of the pelvic floor

• perineal region (Regio perinealis) inferior to the pelvic floor. The anterior portion contains the two perineal spaces, and includes the variably expanded anterior recesses of the ischio-anal fossa (illustrated here in two different ways for the right and left sides).

The deep perineal space (Spatium profundum perinei) consists of connective tissue and single muscle fibres of the M. transversus perinei profundus. It also contains the passage of the Vagina and the Urethra. The deep perineal space is traversed by the deep branches of the N. pudendus (N. dorsalis clitoridis), and the A. and V. pudenda interna (A. bulbi vestibuli, A. dorsalis clitoridis, A. profunda clitoridis) before they reach the Vulva. The Nn. cavernosi clitoridis pierce the Perineum and enter the Corpora cavernosa of the Clitoris.

The superficial perineal space (Spatium superficiale perinei) is located between the perineal membrane (Membrana perinei) and the body fascia (Fascia perinei). It contains the M. transversus perinei superficialis, the proximal parts of the Corpora cavernosa clitoridis, the Glandulae vestibulares majores (BARTHOLIN‘s glands), and the vestibular bulb (Bulbus vestibuli). The bulb of the vestibule is embraced by the M. bulbospongiosus, the Crura clitoridis by the M. ischiocavernosus on both sides. The superficial branches of the N. pudendus (N. perinealis with Nn. labiales posteriores), and of the A. and V. pudenda interna (A. perinealis with Rr. labiales posteriores) also traverse this space to reach the labia.

Projection of the rectum and anal canal

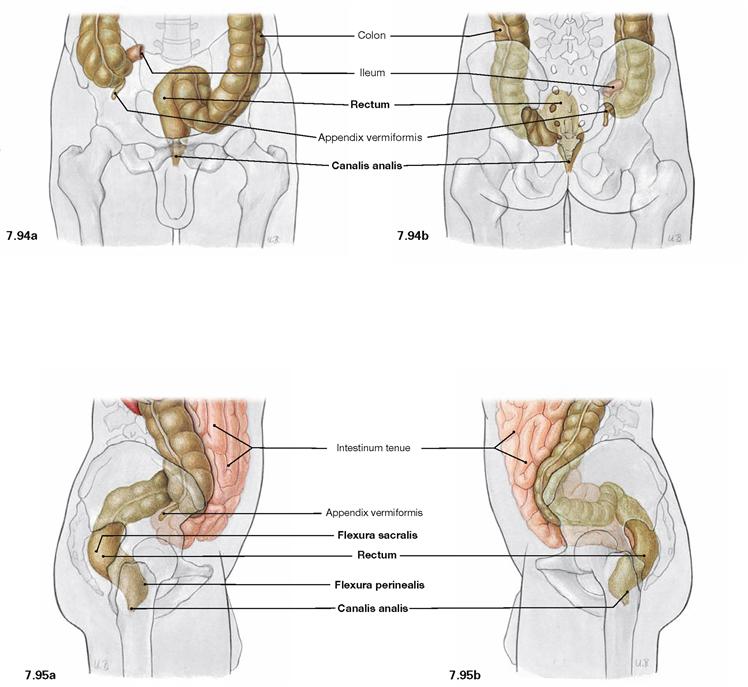

Fig. 7.94 and Fig. 7.95 Projection of the rectum, Rectum, and of the anal canal, Canalis analis, onto the body surface; ventral (→ Fig. 7.94a), dorsal (→ Fig. 7.94b), and lateral (→ Figs. 7.95a and b) views.

The Rectum begins at the level of the 2nd or 3rd sacral vertebrae and ends on the pelvic floor which is traversed by the anal canal. In the sagittal plane, the Rectum has two bends: the dorsally convex Flexura sacralis and the ventrally convex Flexura perinealis. The upper portion of the Rectum above the Flexura sacralis is a secondarily retroperitoneal organ, the distal portion and the anal canal have a subperitoneal position.

Position of the rectum

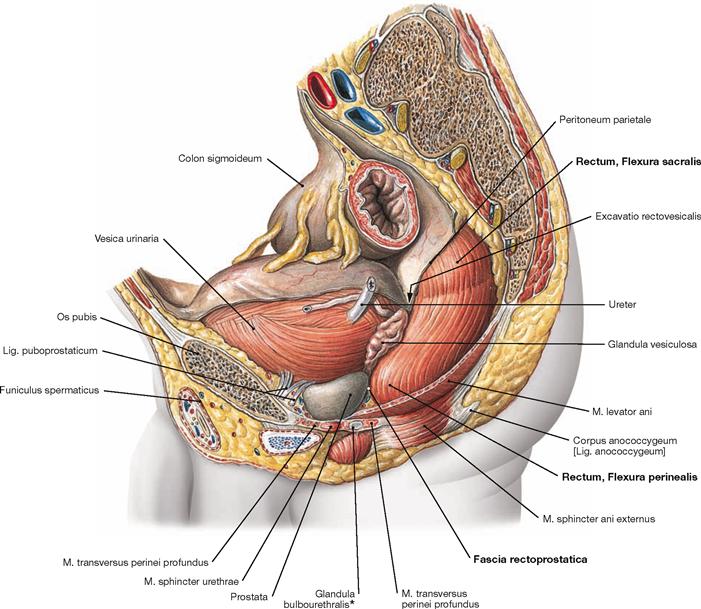

Fig. 7.96 Rectum, Rectum, in the male pelvis; view from the left side.

The illustration shows the two bends of the Rectum in the sagittal plane. In the upper secondary retroperitoneal portion, the Rectum adjusts to the curvature of the sacrum and displays the dorsally convex Flexura sacralis. Inferior to this part, the Rectum is not covered by parietal peritoneum, but has a subperitoneal position. The ventrally convex Flexura perinealis is at the level of the pelvic diaphragm. Inferior to the pelvic diaphragm, the Rectum continues as the anal canal in an inferior and dorsal direction. In men, the anterior aspect of the Rectum is adjacent to the posterior wall of the urinary bladder (Vesica urinaria) and the seminal vesicles (Glandulae vesiculosae) and further caudally to the prostate gland. Here, the Rectum is separated from the prostate gland only by the thin Fascia rectoprostatica (DENONVILLIER’s fascia). In women, the Rectum is closely adjacent to the posterior aspect of the Vagina and only separated from the Vagina by the Fascia rectovaginalis (→ Fig. 7.116).

* clinical term: COWPER’s glands

Structure of the rectum

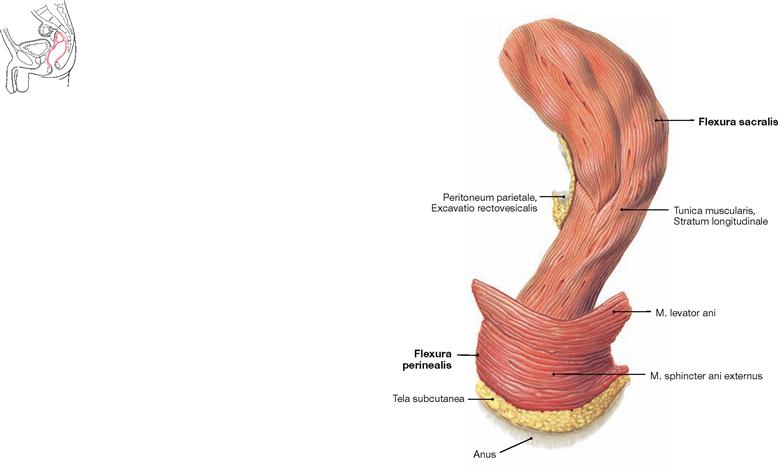

Fig. 7.97 Rectum, Rectum; view from the left side.

Cranially, the Rectum forms the dorsally convex Flexura sacralis and caudally, at the level of the passage through the pelvic floor, the ventrally convex Flexura perinealis.

Unlike the Colon, the muscular layer (Tunica muscularis) of the Rectum not only contains the circular layer (Stratum circulare) but also a continuous longitudinal layer (Stratum longitudinale).

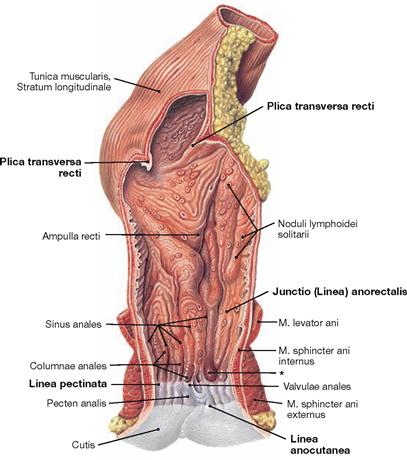

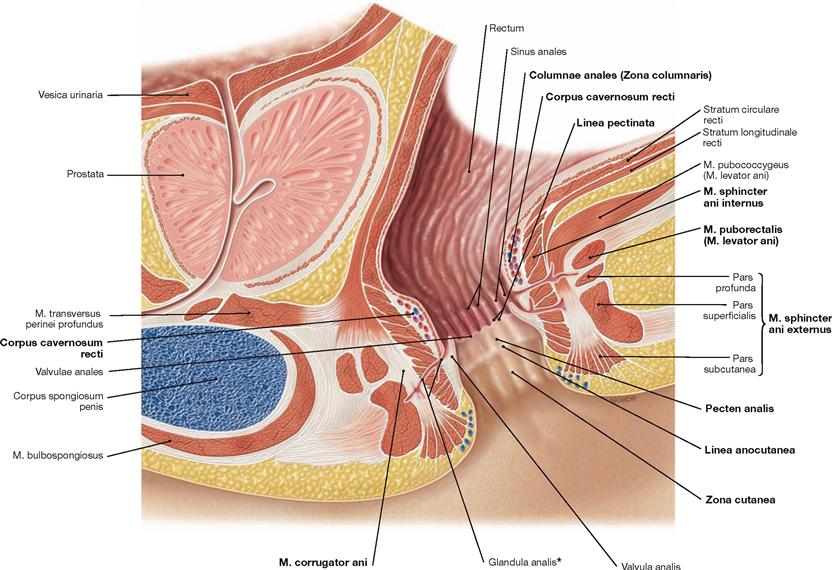

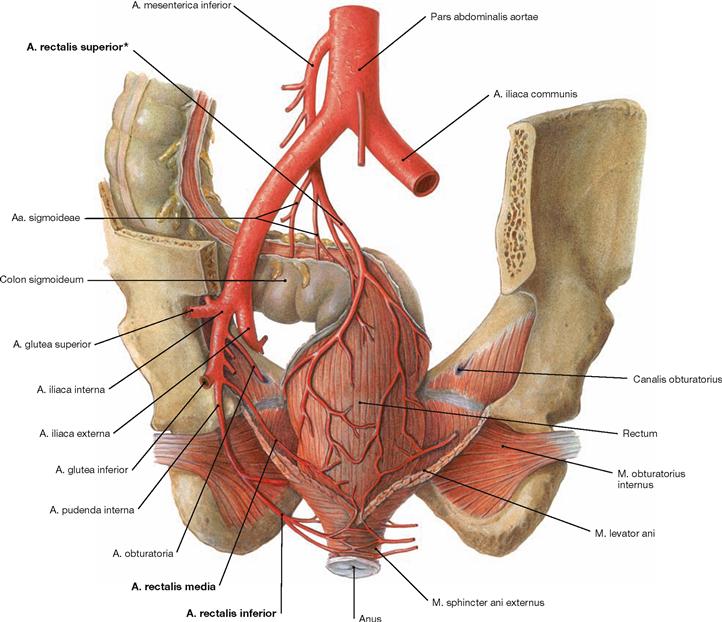

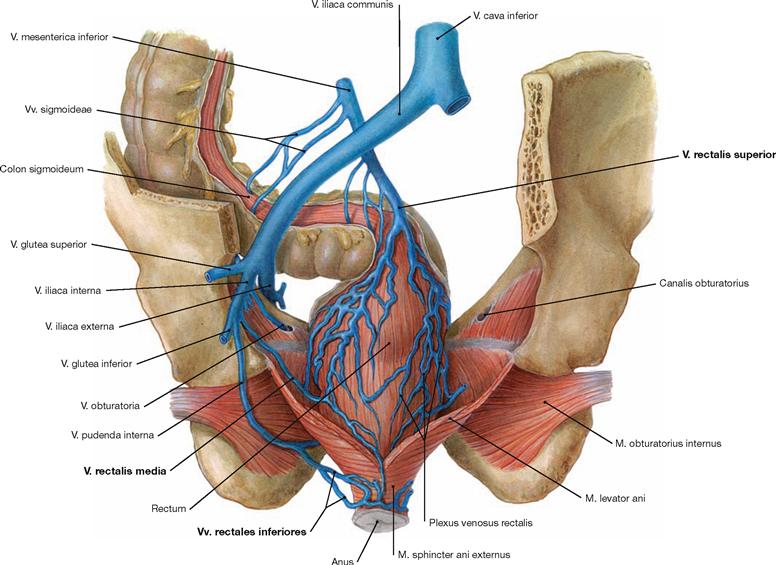

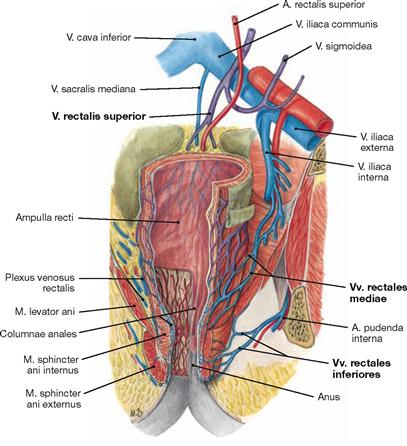

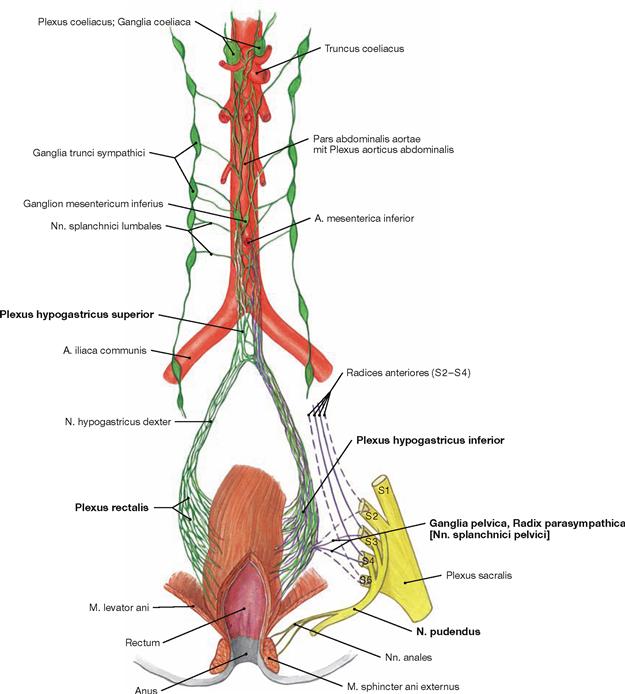

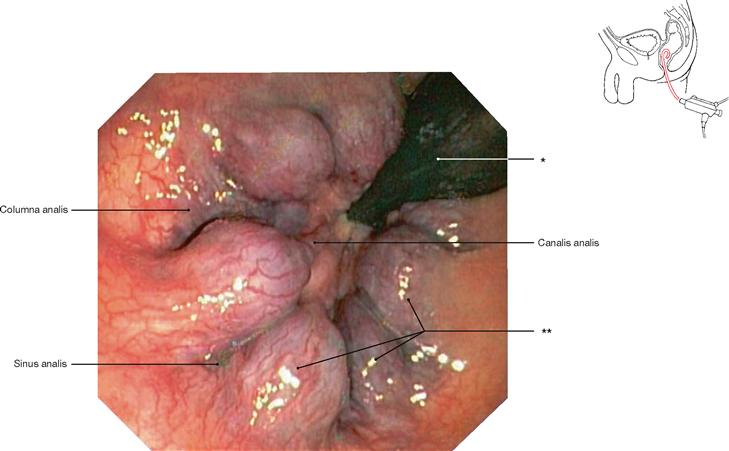

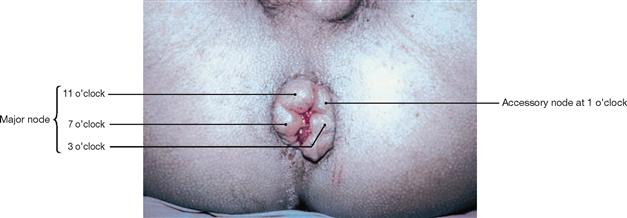

Fig. 7.98 Rectum, Rectum, and anal canal, Canalis analis; ventral view.