Chapter 36 Asian medicine

HISTORY OF ASIAN MEDICINE SYSTEMS

Many medical systems have emerged from Asia over the centuries, including Unani, Siddha and Ayurveda. When looking in detail at these systems, obvious similarities exist—the main one being the holistic approach each of them takes in treating patients. However, differences arise when one looks at how the development of each system has been affected by non-Asian medical systems over the centuries.

Unani medicine

Unani can be literally translated from the Arabic language as meaning ‘Greek’, from the Arabic word for Greece: ‘al-Yunaan’. As an alternative medicine, Unani has found favour in Asia, especially India. In India, Unani practitioners can practise as qualified doctors, as the Indian government approves their practice. The principles of Unani medicine are based on the teachings of Hippocrates, Galen and Avicenna, and are based on the four humours (elements: phlegm (Balgham), blood (Dam), yellow bile (Safra) and black bile (Sauda). Although the principles of Unani can be traced back to year AD 2 the knowledge and teachings of the medical system were not documented until AD 1025, when Hakim Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in the West) wrote The Canon of Medicine in Persia. The development of Unani medicine, as documented in this medical encyclopaedia, was influenced by Greek and Islamic medicine, and also by the Indian medical teachings of Sushruta and Charaka, the main texts of Ayurvedic medicine; both systems are based on the theory of the presence of elements in the human body, and the balance of these elements determines the state of a person’s health. Each person’s unique mixture of these substances determines his or her temperament: a predominance of blood gives a sanguine temperament; a predominance of phlegm makes one phlegmatic; yellow bile, bilious (or choleric); and black bile, melancholic. In Unani medicine, many medicines are based on honey, which is considered to have healing properties. Real pearls and metal are also used in the making of Unani medicine based on the kind of ailment it is aimed to heal. In today’s modern medical world, honey is often used in wound dressings to kill bacteria because the high sugar content causes movement of water from inside bacterial cells by osmosis, leading to massive dehydration and the eventual death of the infecting organisms.

Ayurveda

Ayurveda is the ancient and sacred (Hindu) system of health care, originating in India over 5000 years ago. It is purely Indian in origin and has not been influenced by other countries or their medical systems. The literal translation of the word ‘Ayurveda’ from two words in Sanskrit—āyus, meaning ‘life principle’ and veda, referring to a ‘system of knowledge’—accurately portrays the complexity and depth into which this medical system goes. A more overreaching translation can be taken as ‘The knowledge (or science) of life’. The Charaka Samhita—an ancient Indian Ayurvedic text on internal medicine defines ‘life’ as a ‘combination of the body, sense organs, mind and soul, the factor responsible for preventing decay and death, which sustains the body over time, and guides the processes of rebirth’ and is one of the earliest written texts of Ayurveda, dating back to about 300 BC (see Chattopadhyaya, Further reading). It is believed to be the oldest of three ancient treatises of Ayurveda and is central to the modern-day practice of Ayurvedic medicine. Ayurveda is concerned with measures to protect ‘āyus’, which includes healthy living along with therapeutic measures that relate to physical, mental, social and spiritual harmony. It is also one among the few traditional systems of medicine to contain a sophisticated system of surgery (which is referred to as ‘salya-chikitsa’). In today’s Western society, theemergence of holistic health systems such as Ayurveda has led to the accommodation of modern science, especially in relation to the testing of medicines, in which research and adaptation are actively encouraged. Indeed, it is perfectly possible to evaluate Ayurvedic medicines using conventional clinical trials, and this is being carried out increasingly. At present, there are only a few Ayurvedic practitioners (‘vaid’) in the West, but the rapidly increasing popularity of more holistic approaches to health—where each patient is considered unique and therefore must be treated individually—has led to the emergence of schools of Ayurveda, Ayurvedic treatment centres and more Ayurvedic medicines being imported. This approach is in contrast to Western medicine where populations are generalized and ‘normal’ means what is applicable to the majority. Many ethnic populations from India and Pakistan continue to use their own traditional remedies while living in Europe, Australia or the US. Philosophically, Ayurveda has similarities with Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). The familiar yin and yang—the opposing life forces identified in TCM, can be likened to the three ‘humours’ of Ayurveda—the tridosha.

Siddha medicine

Siddha, from the Tamil word for ‘achievements’, is said to have been developed by eighteen siddhars (beings who have achieved a high degree of physical as well as spiritual perfection or enlightenment), led by the great Siddha Ayastiyar. Some of his works are still standard books of medicine and surgery in daily use among the Siddha medical practitioners of today. Siddha literature is written in Tamil and the medicine is practised largely in Tamil-speaking parts of India and abroad. Like Ayurvedic medicine, this system believes that all objects in the universe, including the human body, are composed of five basic elements: earth, water, fire, air and sky. Siddha medicine is largely therapeutic in nature, and is a form of treatment of disease using substances of all possible origins in a way that balances the possible harmful effects of each substance. The principles and doctrines of this system, both fundamental and applied, have a close similarity to Ayurveda. Additionally, this system also considers the human body as a conglomeration of three humours, seven basic tissues and the waste products of the body. As in both Unani and Ayurvedic medical systems, the equilibrium of humours is considered as a healthy state, and its disturbance or imbalance leads to disease or sickness. Ancient siddhars wrote their recipes on palm-leaves for the use of future generations, and details include preparations that are made mainly out of the parts of the plants and trees, such as leaves, bark, stem, root, etc., but also include mineral and some animal substances. The use of metals like gold, silver and iron powders in some preparations is a special feature of Siddha medicine, which claims it can detoxify metals to enable them to be used for stubborn diseases. The use of mercury in the Siddha medical system is well documented and not uncommon, so patients prescribed medicines containing purified mercury should be treated only by highly qualified practitioners of the art. Over the centuries, the system has developed a rich and unique treasure of drug knowledge in which use of metals and minerals is very much advocated. The depth of knowledge required by practitioners of Siddha medicine is summarized below:

Most medicines and remedies (often common herbs and foods) used in Unani medicine (and Siddha medicine to a lesser extent) are also used in Ayurveda. Whereas Unani was influenced by Islam and Siddha by Alchemy, Ayurveda is associated with Vedic culture, and is generally considered to be the most ‘original’ form of traditional Asian medicine. The Materia medica of all these medical systems consists of many herbs made into pills, syrups, confections and alcoholic extracts, and also some metals. These traditional systems are still practised in rural communities in India and Pakistan—much more so than in cities.

COMMON TERMS AND CONCEPTS USED IN AYURVEDA

Ayurveda is dealt with in more detail because it has influenced the other Asian systems of medicine and remains the philosophical base for them. It is becoming increasingly popular in the West, although the term ‘Ayurveda’ is often misused. For example, recent newspaper headlines in the US included statements such as:

Ayurveda continues to grow rapidly as one of the most important systems of mind–body medicine, natural healing and traditional medicine as the need for natural therapies, disease prevention and a more spiritual approach to life becomes ever more important in this ecological age.

before going on to calculate the success of this ‘eco-friendly science’ in material terms—in 2007 the ‘global herbal market’ was worth US$120 billion, with Ayurvedic treatments and products accounting for 50% of the total (The Hindu, 27 October 2007). There can be no argument about the increasing popularity of Ayurveda—clinics and treatment centres exist thousands of miles from India, and the term ‘Ayurvedic tourism’ is now recognized in many holiday resorts. Unfortunately, the high-class beauty and pampering packages offered in such places are centuries away from the ‘real’ Ayurveda, and disappoint professional vaids, who consider the use of a holistic system of medicine, meant to diagnose and treat a whole person, being reduced to superficial treatments intended to focus on a single part of the body as a travesty.

Prana is known as the ‘life energy’ and activates both the body and mind in Ayurvedic medicinal systems. It is contained in the head and controls the main functions of the mind, including emotions, memory and thought. Additionally, prana kindles the bodily fire ‘Agni’ and therefore controls the function of the heart and, via the bloodstream, other vital organs (dhatus).

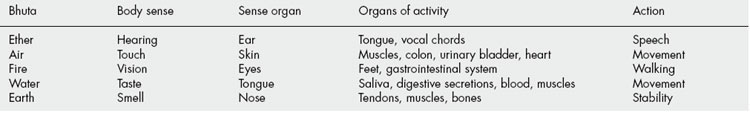

Bhutas are the five basic elements of Ayurveda—ether (or space), air, fire, water and earth. They are seen as manifestations of energy and can be equated to the five senses of hearing, vision, touch, taste and smell. In turn, these senses are associated with a particular sense organ (or organs) of the body, which impact on other ‘organs of activity’ and result in actions being carried out by the body. Table 36.1 summarizes some of the associations between the bhutas and the activities they govern.

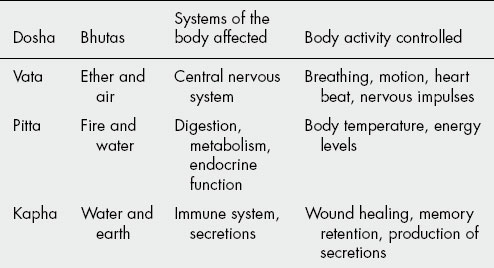

Tridosha are the three humours or basic forces that manifest in the human body. They are formed from the five bhutas and are known as vata, pitta and kapha. The tridosha govern all functions of the body and mind and, by understanding the relationship between them, a vaid may make a diagnosis of the disease affecting a patient. Table 36.2summarizes how the bhutas combine to form each of the dosha, and how each dosha affects the human body.

It should be noted the tridosha govern basic human emotions such as fear, anger and greed, and are involved in more complex emotions such as empathy, compassion and love. It is thought that when the tridosha are in equilibrium, the body and mind are healthy and a sense of well-being exists within a person. It is difficult to draw similarities between this philosophy and modern science, but most readers will agree that a sense of well-being exists in most of us when we are rested, well-fed and exercised.

Prakruti is a description of the human constitution—the ‘type’ of person you are. It is believed the individual’s prakruti is determined by the parents’ prakruti at the time of conception. A vaid can analyse a patient’s constitution by looking at how his or her tridosha combine. Most people are a combination of dosha elements, and can be described as vata-pitta or pitta-kapha for instance. Table 36.3 shows the dosha characteristics associated with different parts of the human constitution.

Table 36.3 A summary of constitutional characteristics associated with different dosha.

| Dosha | Body characteristics |

|---|---|

| Vata | Lean build, with cool, dry and occasionally rough skin. These types often have small dark eyes and dark, curly hair. They may have a poor appetite, but variable thirst and are often mentally restless. They have a tendency to be emotionally insecure and unpredictable, lots of nervous energy, a fast mode of speech and poor, often interrupted sleep patterns |

| Pitta | Tend towards a medium build, with soft, warm skin, sharp (often grey or green) eyes and fair, sometimes oily hair. They have a good appetite (sometimes excessive) and are often thirsty. They tend towards sharp, aggressively intelligent mentality, causing a short temper and irritability. They have a strong method of speech, a moderate exercise level, but require little sleep, as it is always very sound |

| Kapha | Can be overweight, with cool, slightly oily skin. These types often have big blue eyes and thick hair. Often they have a low appetite for food or liquids, and tend to have a calm, considerate mentality. Emotionally they are calm and acquisitive, and tend to think carefully before they speak. They have an aversion to exercise and tend to have deep and lengthy sleep patterns |

As well as the vata, pitta and kapha type of personalities, three attributes provide the basis for distinctions in human temperament, individual differences and psychological and moral dispositions. These basic attributes are satva, rajas and tamas. In brief, satva expresses essence, understanding, purity, clarity, compassion and love; rajas describes movement, aggressiveness and extroversion; and tamas manifests in ignorance, inertia, heaviness and dullness.

Agni is known as the ‘digestive fire’ and governs metabolic processes. It is essentially pitta in nature. Agni can become impaired by an imbalance in the tridosha and therefore affect metabolism. In these circumstances, food will not be digested or absorbed properly, and toxins will be produced in the intestines and may find their way into the circulation.

Ama are the waste products of the body—faeces, urine and sweat—and are the root cause of disease. Their appearance and properties can give many indications of the state of the tridosha and therefore health. For example, a patient suffering from a pitta disorder, such as fever or jaundice, may have dark urine. Additionally, substances such as coffee and tea, which stimulate urination, also aggravate pitta and render the urine dark yellow. If a patient has overactive ama production, the overcombustion of nutrients may occur, leading to vata disorders and emaciation (e.g. overactive thyroid).

Dhatus are the seven tissues or organs of which the human body is composed. Therefore any imbalance in the tridosha directly affects the dhatus. Dhatus are those substances that are retained in the body and always rejuvenated or replenished. The dhatus do not correspond to our definition of anatomy, but are more a tissue type than an individual organ. Table 36.4 provides an approximate relationship between dhatus and parts of the body.

Table 36.4 The Sanskrit name for each of the seven dhatus and the tissues or organs with which they are associated.

| Dhatu | Associated organ or tissue |

|---|---|

| Rasa | Nutritional fluid: plasma |

| Rakta | Blood: life force |

| Mamsa | Muscles: cover bones |

| Meda | Adipose tissue: lubrication |

| Asthi | Bone: help to stand and walk |

| Majja | Bone marrow: nerve tissue nourishment |

| Shukra | Testes/ovaries: reproduction |

Gunas Charaka, author of the Charaka Samhita, wrote that all material, both organic and inorganic, as well as thought and action, have ‘attributes’—qualities that contain potential energy, while the actions with which they are associated express kinetic energy. This is possibly the first reference to the concept of potential and kinetic energy. Vata, pitta and kapha each have their own attributes, and substances having similar attributes will tend to aggravate the related bodily humour. Table 36.5 gives a brief summary of the three gunas.

Table 36.5 A summary of the three Gunas and their effects upon the body.

| Guna | Definition | Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Sattva | Essence/subtle | Provision of necessary energy for the body without taxing it |

| Raja | Activity | Sensuality, sexuality, greed, avarice, fantasies, egotism |

| Tamas | Inertia/gross | Dullness, drowsiness, pessimism, lack of common sense, laziness, doubt |

PRINCIPLES OF AYURVEDA

In addition to the in-depth analysis of a patient’s prakruti that a vaid will undertake to diagnose the patient’s ailment, astrological considerations and karma must also be considered. Finally a thorough medical examination, not dissimilar to that undertaken by a TCM practitioner, including the appearance of the tongue, properties of the urine, sweat, sputum and faeces will also be carried out. Once the vaid has ascertained the disease and the likely cause of the problem, a complex treatment regimen will be prescribed. As health can be maintained by taking steps to keep vata-pitta-kapha in balance through a proper diet, herbal treatment and exercise programme, this is likely to be the first line of action. The concepts governing the pharmacology, therapeutics and food preparation in Ayurveda are based on the action and reaction of the gunas to and upon one another. Through understanding of these gunas, the balance of the tridosha can be maintained. The diseases and disorders ascribed to vata, pitta and kapha are treated with the aid of medicines possessing the opposite attribute, to try and correct the deficiency or excess. Many of the medicines prescribed in Ayurvedic medicine are herbs and patients may have to take them as medicines (tinctures, inhalations, pills, capsules or powders) or by combining them into their diet in a prescribed fashion. Table 36.6 provides a brief summary of the herb types used to treat different dosha-related illnesses.

Table 36.6 A summary of herb classes used to treat different dosha-related illnesses.

| Dosha-related illness | Herbs types used |

|---|---|

| Vata | Sweet (madhur), sour (amla) or warm (lavana) |

| Pitta | Sweet (madhur), bitter (katu) or astringent and cooling (kashaya) |

| Kapha | Pungent (tikta), bitter (katu) or astringent and dry (kashaya) |

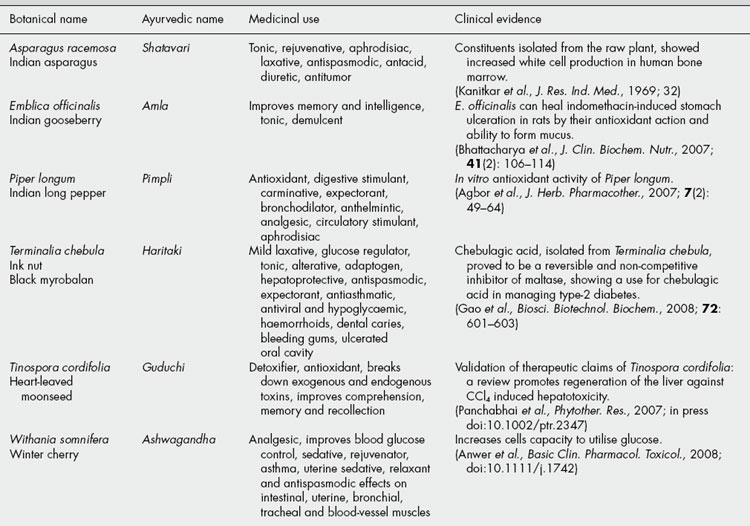

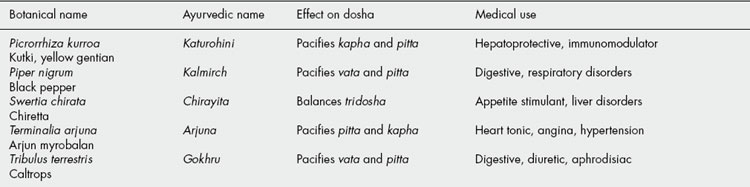

Rasayana—widely used herbs

Rasayana (literal translation ‘longevity enhancer’) are remedies considered to have diverse action and, therefore, affect many systems of the body leading to a positive effect on health—panaceas in other words. The most important are summarized in a Table 36.7 and are included in many recipes to strengthen the tissues of the body. In general, modern research has found them to have antioxidant, immunomodulating and various other activities.

Preparation of Ayurvedic medicines

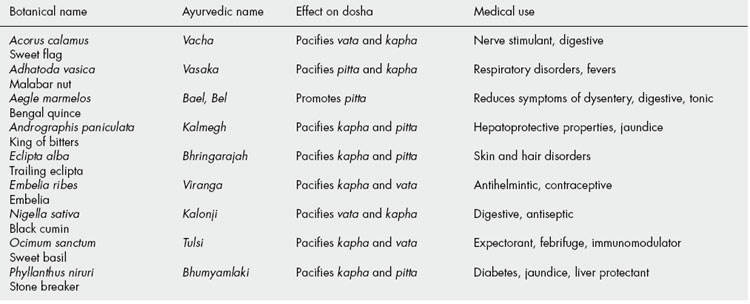

In addition to the rasayanas, many other herbs are used in Ayurvedic medicines. Table 36.8 summarizes some of the best documented. Readers should consider that although documented clinical evidence for the activity of some of these herbs can be fairly scarce, practising vaids stress the importance of the combinations of the herbs—suggesting a synergistic effect between them. Indeed, the main principles that guide Ayurvedic medicinal formulation are: synergy, opposition, enhancement, protection and, as always in holistic systems, balance. Each of these principles is summarized below:

The preparation of Ayurvedic medicines follows the general Ayurvedic philosophy that emphasizes the whole; that is, substances are combined in such a way that their natural attributes synergistically enhance the action of the whole formula. Traditional formulae are often named, and may denote a specific combination of herbs and other products prepared in a prescribed way, or instead, for their major ingredient(s). In some instances, the name denotes the person who first devised the formula, the therapeutic action of the medicine, or the part of the plant used. For example, Triphala powder is a mixture of powders of three fruits—amla, baheda and hirda—whilst Chyavanprash is a semi-solid formulation named after a sage, ‘Chyavan’, who first devised the formula.

Preparative methods

As discussed previously, single drugs are rarely used in Ayurvedic practice. The formulations usually contain heterogeneous mixtures of herbs and minerals that have undergone a complex process of purification and preparation. Traditional methods used to prepare Ayurvedic drugs are based on the principles of extraction, concentration and purification, and the choice of preparation method depends on the part of the plant to be used, on its condition (fresh or dried), and on the drug’s expected use. For example, cold decoctions are preferred for conditions attributed to an excess of pitta. Table 36.9 gives a summary of some of the most common methods of preparation of herbal material used to produce Ayurvedic medicines. For a more extensive list of herbal ingredients of Asian medicine in general, covering 97 families of plants, see M. Aslam, in the 15th edition of this book,p. 471.

Table 36.9 Methods of preparing Ayurvedic medicines.

| Formulation | Method of production |

|---|---|

| Juice (Swaras) | Cold-pressed plant juice |

| Powder (Churna) | Shade-dried, powdered plant material |

| Cold infusion (Sita kasaya) | Herb : water 1 : 6, macerated overnight and filtered |

| Hot infusion (Phanta) | Herb : water 1 :4, steeped for a few minutes and filtered |

| Decoction (Kathva) | Herb : water 1 : 4 (or 8, 16 then reduced to 1 : 4) boiled |

| Poultice (Kalka) | Plant material pulped |

| Milk extract (Ksira paka) | Plant boiled in milk and filtered |

Shodhana (purification) is the process by which toxic substances are purified; that is, rendered less toxic. For example, detoxification of mercury involves a drawn-out process of heating and cooling the mercury salt, grinding it and then suspending and re-suspending the substance in a variety of liquids. Specific products that facilitate the process are added at each stage of preparation and the instructions might call for the use of a specific vessel at different stages of preparation. The instructions can be so detailed, up to the point of stating from which direction the heat is to be applied. It is left to the experience of Ayurvedic practitioners to decide, at the conclusion of an appropriate purification process, that the toxic substances are no longer poisonous but therapeutic. From this brief summary, it can be seen that the classical Ayurvedic methods of preparation are complex and tedious, and that short-cuts in preparation may make a significant difference in the efficacy and safety of the resulting product. Because of this, it may be beyond the scope of the average scientific paper to exactly describe the method by which an herb is prepared, especially if a formula is used, which may go some way as to explaining why such problems exist in replicating the results of other researchers.

Chattopadhyaya D, editor. Case for a critical analysis of the Charaka Samhita. In: Studies in the history of science in India. Vol 1. Editorial Enterprises, New Delhi, 1982:209-236

Kapoor LD. Handbook of Ayurvedic medicinal plants. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1990.

Lad V. Ayurveda the science of self-healing. Wisconsin, USA: Lotus Press, 1990.

Puri HS. Rasayana Ayurvedic herbs for longevity and rejuvenation. In: Hardman RH, editor. Traditional herbal medicine for modern times. London: Taylor and Francis, 2003. (series ed)

Rankin-Box D, Williamson EM. Herbal medicine, phytotherapy and nutraceuticals. In: Complementary medicines, a guide for pharmacists. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2006:52-68.

Sairam TV. Home remedies. Vols I, II and III. Mumbai, India, 2000.

Williamson EM, editor. Major herbs of Ayurveda. The Dabur Foundation. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.