6 Gait assessment of neurological disorders

The aim of this chapter is to provide examples of how gait analysis can be used to determine the severity, progression and the efficacy of non-surgical, surgical and pharmaceutical management of neurological disorders. This chapter will consider several common disorders and their management, including cerebral palsy, hemiplegia, Parkinson's disease and muscular dystrophy.

Gait assessment in cerebral palsy

Definition, causes and prevalence

Cerebral palsy is now defined as a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture which can be attributed to brain damage to the fetus or infant (Rosenbaum et al., 2007). The condition is different from other forms of brain damage such as stroke or traumatic brain injury because it happens while the brain is still developing and this affects the subsequent neurological and musculoskeletal development of the child. The motor disorders of cerebral palsy are often accompanied by disturbances of sensation, perception, cognition, communication and behaviour, and by epilepsy. Cerebral palsy is the commonest cause of physical disability affecting children in the developed world with a prevalence of around 2 cases for every 1000 live births (Stanley et al., 2000). Figures for other parts of the world are difficult to ascertain but it is generally assumed to be at least as prevalent.

The brain damage is much more common in infants born prematurely but the precise cause is unknown in the majority of cases. The ultimate cause is a failure of the oxygen supply to an area of the developing brain which may be a consequence of damage to the blood vessels, such as haemorrhage or embolism, or a more general drop in fetal blood pressure. The brain damage, once it has occurred, is static and will not get any better or any worse. The clinical manifestations, however, will continue to develop and change as the child grows and matures. This is particularly true of the musculoskeletal manifestations of cerebral palsy, which are very important in determining whether and how people with the condition will walk.

Classification

Gross motor function classification system

The principal means of classifying children with cerebral palsy is with the Gross Motor Function Classification System GMFCS (Palisano et al., 1997 and 2000). This is, essentially a five-point scale reflecting the severity of the condition as it affects motor function. There are different definitions for different age groups but that for 6–12 year olds is the most relevant to gait analysts (Table 6.1). It can be seen that most children who are suitable for gait analysis will be of levels I–III. More recently descriptors for 12–18 year olds have been produced (Palisano et al., 2008). These are similar to those in Table 6.1 but allow for some deterioration in motor ability that occurs in late childhood. While gait analysis is most often used for children with cerebral palsy it is worth remembering that cerebral palsy is a life-long condition, with between 25% and 50% of adults reporting further deterioration in walking ability in early adulthood (Day et al., 2007; Jahnsen et al., 2004; Murphy et al., 1995).

Table 6.1 Gross Motor Function Classification System for children aged 6–12 years

| Level I | Children walk indoors and outdoors and climb stairs without limitation. Children perform gross motor skills including running and jumping, but speed, balance and coordination are impaired |

| Level II | Children walk indoors and outdoors and climb stairs holding onto a railing but experience limitations walking on uneven surfaces and inclines and walking in crowds or confined spaces and with long distances |

| Level III | Children walk indoors and outdoors on a level surface with an assistive mobility device and may climb stairs holding onto a railing. Children may use a wheelchair for mobility when travelling for long distances or outdoors over uneven terrain. |

| Level IV | Children use methods of mobility that usually require adult assistance. They may continue to walk for short distances with physical assistance at home but rely on wheeled mobility (pushed by adult or operate a powered chair) outdoors, at school and in the community |

| Level V | Physical impairment restricts voluntary control of movement and the ability to maintain anti-gravity head and trunk posture. All areas of motor function are limited. Children have no means of independent mobility and are transported by adults |

Classification by motor disorder and topography

The brain damage that causes cerebral palsy can affect the nervous system in several different ways. In about 85% of people the major limitation is spasticity, which leads to over activity in specific muscles. A further 7% are dyskinetic (dystonic-athetoid) having mixed muscle tone (high or low), which leads to slow sinuous movements superimposed on the intended motor pattern. Another 5% have ataxia which leads to rapid jerky movements and affects balance and depth perception. People with dyskinesia or ataxia tend to have very variable gait patterns, which can limit the usefulness of clinical gait analysis. Outcomes of orthopaedic surgery in people with dyskinesia can be unpredictable. Most children attending for clinical gait analysis are therefore those with a predominantly spastic motor type.

Before the advent of the GMFCS, the primary classification of children with cerebral palsy was with respect to the areas of the body that were most affected. Hemiplegia refers to one side of the body being affected including an arm and leg on the same side. Diplegia refers to the involvement of both legs and quadriplegia to involvement of all four limbs. Monoplegia (involvement of one limb) and triplegia (involvement of three limbs) are also used. Many children do not fall neatly into these categories and the distinction between quadriplegia and diplegia is rarely clear-cut; many diplegic individuals are affected much more on one side than the other. Such issues have led to recent advice that such terms be discontinued until they are defined more precisely. Unilateral and bilateral motor involvements are now the preferred terms for children who can walk with total body involvement being used for non-walkers. Having said this, the original terms are still in widespread use.

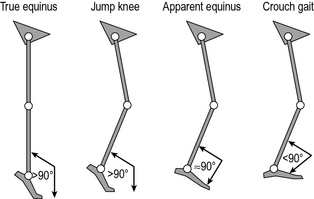

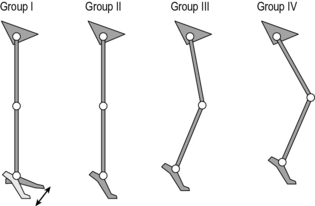

Classification by gait pattern

There have been several attempts to classify cerebral palsy on the basis of the gait pattern (Dobson et al., 2007). Some confusion has arisen because several authors have chosen to re-define terms used by previous authors and it is not always clear which classification system is being referred to by which term. Two classifications for spastic hemiplegic gait have been proposed (Hullin et al., 1996; Winters et al., 1987) of which Winters et al. is more commonly used. This is described in Figure 6.1 and Table 6.2. There is some confusion in how this is applied clinically. The original paper refers exclusively to the sagittal plane and is based purely on the gait pattern. It is not at all uncommon to hear clinicians incorporating consideration of the transverse plane (particularly at the hip) and inferences about the nature of the underlying pathology (rather than just the gait pattern) in classifying children. Agreement between clinicians in applying this classification is substantial (Dobson et al., 2006). A more recent population-based study suggested that groups I, II and IV are far more common than group III.

Fig. 6.1 • Common gait patterns in hemiplegic cerebral palsy

(reproduced with permission and copyright © of the British Editorial Society of Bone and Joint Surgery. (Rodda et al., 2004).

Table 6.2 Classification of gait patterns in hemiplegia*

| Group I | Ankle equinus in the swing phase of gait due to underactivity of the ankle dorsiflexors in relation to the plantarflexors |

| Group II | Plantarflexion throughout stance and swing from either static or dynamic contracture of the triceps surae. Knee is often forced into slight hyperextension in middle or late stance |

| Group III | Findings of type II with reduced range of knee flexion/extension. Reference is now common to sub-types IIIa: reduced knee extension during stance, and IIIb: hyperextension in stance and reduced flexion in swing |

| Group IV | Findings of type III with involvement of the hip musculature† |

* Summary by Thompson et al. (2002) of original by Winters et al. (1987).

† In the original paper, in which measurements were restricted to the sagittal plane, this was attributed to flexor and adductor involvement. A three-dimensional analysis would almost certainly have included increased internal rotation

Classifications of gait patterns in spastic diplegia are less clear cut. One example is the classification by Rodda et al. (2004) in which the whole gait pattern is described (Fig. 6.2 and Table 6.3). There is particular confusion with regard to a number of terms that different people have chosen to define differently. Sutherland and Davids (1993), for example defined ‘jump’ as referring to a pattern in which the knee is flexed in early stance but extends rapidly in a pattern reminiscent of jumping. Rodda et al. (2004) used the same term to refer to a posture of flexed knee and plantarflexed ankle in late stance. ‘Crouch’ gait is another term that has been defined differently by a range of authors. Many studies simply use the term to refer to a gait pattern exhibiting knee flexion of no less than a certain value (30° is commonly used) throughout stance. Gage et al. (2009) used a kinetic definition for patterns in which the internal knee moment is extensor throughout stance, whereas Rodda et al. (2004) required ankle dorsiflexon as well as knee flexion.

Table 6.3 Common gait patterns in spastic diplegic cerebral palsy (Rodda et al., 2004)

| Group I | The ankle is in equinus. The knee extends fully or goes into mild recurvatum. The hip extends fully and the pelvis is within the normal range or tilted anteriorly |

| Group II | The ankle is in equinus, particularly in late stance. The knee and hip are excessively flexed in early stance and then extend to a variable degree in late stance, but never reach full extension. The pelvis is either within the normal range or tilted anteriorly |

| Group III | The ankle has a normal range but the knee and hip are excessively flexed throughout stance. The pelvis is normal or tilted anteriorly |

| Group IV | The ankle is excessively dorsiflexed throughout stance and the knee and hip are excessively flexed. The pelvis is in the normal range or tilted posteriorly |

Classification by gait pattern does not give the whole picture. The two most commonly used schemes are based on sagittal plane data only (Rodda et al., 2004; Winters et al., 1987). Winters et al. proposed their classification system for people who had had no previous orthopaedic intervention and it is not clear how much value the scheme has for people who have had surgery. Rodda et al. did not discuss how surgery, or other interventions, would affect classification by gait pattern. There is considerable variability within grades and some people clearly have patterns on the boundary between one grade and the next. Indeed two studies which include data that can be used to infer whether natural groupings exist (Dobson, 2007; Rozumalski and Schwartz, 2009) would suggest, on the contrary, that gait patterns vary continuously across a multi-dimensional spectrum and groupings will only ever be a rather gross guide to the general pattern of movement. They can, however, still be useful in giving an overall impression of the person's gait pattern particularly if full instrumented gait analysis is not available. A full gait analysis is still essential if we want to be specific about how a person is walking and what is causing them to do so in a particular manner.

Impairments

An impairment is something that is wrong with a person's body structures or the way they function (World Health Organization (WHO), 2001). Examples of impairments include the loss of a limb or loss of vision. These can be complex in people with cerebral palsy. Primary impairments are direct consequences of the brain damage, and thus affect basic neurological function, whereas secondary impairments are indirect consequences arising from the effects of altered neurology on other structures over a long period of time. Thus muscles may become contracted or bones misaligned. Impairments generally fall into four broad categories: spasticity, weakness, muscle contracture and bony malalignment.

Spasticity

The term ‘spasticity’ means different things to different people. Most clinicians working with people with cerebral palsy1 tend to use it to refer to a very specific ‘velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflexes, with exaggerated tendon jerks resulting from hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex’ (Lance, 1980). In other words if a tendon is stretched rapidly then its muscle will become active. Depending on the severity of the spasticity this might be for a short period and the muscle may thus show phasic, but inappropriate activity throughout the gait cycle, or for a longer period in which case the muscle may be inappropriately active throughout the gait cycle. This stretch reflex is present in all of us but in most people is suppressed by signals originating in the brain and passing down the spinal column (descending control). In people with cerebral palsy the brain damage reduces the capacity to send such signals and the reflexes are effectively out of control. Thus, although it is common to hear reference to ‘spastic muscles’, spasticity is really a property of the nervous system.

In cerebral palsy spasticity commonly affects some muscles more than others. In particular the bi- and multiarticular muscles appear to be susceptible (Gage et al., 2009). Thus spasticity is commonly found in the gastrocnemius, hamstrings, rectus femoris and psoas muscles. In more severely affected children, spasticity of the monoarticular hip adductors is a particular issue.

Spasticity, so tightly defined, is not the only alteration to neurological function. In some people with cerebral palsy, particularly those most severely affected, there can be inappropriate muscle activity in the absence of movement as well, and this is generally referred to as resting tone. Dystonia and ataxia are also essentially the manifestation of neurological impairments.

Muscle contracture

Spasticity occurs in a wide range of conditions and in most of these the muscles affected are susceptible to develop contractures. In these the passive length of the muscle and its tendon are reduced and this leads to a restriction in the range of movement that is available at the joints. Most children with cerebral palsy are relatively free from contractures at birth and in infancy and then develop them through childhood. They are commonly named by the position they are held in: for example, a flexion contracture of the knee means that the knee is held in some degree of flexion and cannot fully extend, with the most commonly seen contractures including knee flexion, ankle plantarflexion and hip flexion.

The mechanisms by which contractures develop are not fully understood. In relation to children with cerebral palsy it is quite common to hear contractures talked about as a failure of normal growth, where the bone keeps on growing but the muscle does not. This cannot be the full picture, as some children, particularly those with hemiplegia, can develop contractures over a short period of time which are too severe to be explained simply by failure of growth. Contractures are also common in many adults who have spasticity (in conditions such as stroke). Another common belief is that contractures are a result of immobilisation, which is supported by some early clinical and animal work suggesting that this reduces the length of the muscle fibres (Shortland et al., 2002). Again though, there are many other conditions in which immobilisation of muscles is much more complete than in cerebral palsy, but such severe contractures do not develop. More recent work suggests that a reduction in muscle belly length through shortening of the aponeuroses is much more significant than any reduction in fibre length (Shortland et al., 2002), but no mechanism has been proposed for this. In summary, the development of contractures is probably related to failure of growth, immobilisation and the consequences of spasticity but the relative contributions of these factors remain unknown.

Weakness

It is only relatively recently that the effect of muscle weakness on the gait of people with cerebral palsy has been fully acknowledged. Wiley and Damiano (1998) surveyed the strength of children with cerebral palsy and demonstrated that muscle weakness is also important with the gluteal muscles with the plantarflexors also being particularly weak with respect to those of age-matched able-bodied children. Muscle weakness can arise either because of the anatomy and physiology of the muscles or through reduced neural activity to stimulate contraction. Despite cerebral palsy being an essentially neurological problem there have been few investigations to establish the relative proportions of the muscular and neurological components of weakness.

The weakness has generally been attributed to a muscle's reduced physiological cross-sectional area attributed to short muscle belly length and may therefore be strongly related to the development of contracture in both spastic hemiplegia and diplegia (Elder et al., 2003; Fry et al., 2007). The clinical picture does not always agree with this, with some muscles appearing to be quite weak without evidence of contracture. It is also known, however, that there is more extra-cellular material of lower quality than in normal muscle. Recent evidence suggests that these changes are quite different from those that arise simply through either chronic stimulation or disuse (Foran et al., 2005) but, as with the development of contracture, the underlying mechanisms are not understood. During movement there is a further factor in that contractures or specific walking patterns may result in muscle fibres functioning away from their optimal length to generate contractile force. The clinical picture appears to be that the muscles get weaker with age with respect to those of children without cerebral palsy. A particular issue arises in late childhood and early adolescent when weight increases rapidly and relative weakness becomes significant.

Bony malalignment (and capsular contracture)

Children with cerebral palsy are also susceptible to developing malalignment of the bones. Anteversion of the femur is the most common example of this. It is essentially a twist somewhere along the shaft of the femur which results in the femoral neck pointing too far forwards in relation to the knee joint axis. Although it is commonly referred to as a developmental deformity it is actually a result of persistence of the original bony alignment. At birth most children have anteversion of about 40° but this reduces in normal growth to about 10° at skeletal maturity. This reduction does not occur in many children with cerebral palsy. It is not uncommon for the tibia to be twisted externally along its shaft, tibial torsion, and malalignment of the bones of the foot, particularly the calcaneus is also common. In more severely affected children spinal, thoracic and upper limb deformities are also common.

As with the other impairments the precise mechanisms are unclear but at least three factors need to be considered. Bones grow in length at the growth plates. Most long bones have a growth plate proximally and distally. The rate at which the bones grow is determined by the stress exerted across the growth plate. In areas of the growth plate across which large compressive stresses are exerted, longitudinal growth will be suppressed and elsewhere growth may be stimulated. Thus normal bone growth requires normal stress distributions. Walking is believed to be a major contributor to such stresses and thus if children do not walk normally the bones will not grow normally. Remodelling is another factor. Once bones have grown the bone continues to be replaced on an ongoing basis and this can lead to a change in shape of the bone. Interestingly the opposite law applies here. High compressive stresses tend to stimulate the production of more bone whereas lower stresses suppress this. The third factor is that cartilaginous bone can actually be deformed mechanically and this may be particularly important in the feet where some bones are not fully calcified until around the age of 10 years.

A further common impairment is contracture of the joint capsule. This is particularly common at the knee but may also restrict extension and internal/external rotation of the hip. It results from contracture of the ligaments which form the joint capsule and is thus quite distinct from contracture of the muscle. It is included with bony deformities because the capsule is a deep structure and quite difficult to approach surgically. Management of joint contractures is thus often achieved through bony surgery similar to those used to manage bony malalignment.

Clinical management

Natural history

Establishing the natural history of cerebral palsy is now quite difficult because it is unethical to deprive children of the benefits of modern medicine. Children seen for gait analysis will typically have had delayed motor milestones such as the age at which they first sat, crawled or walked. Spasticity may be evident very early and weakness (particularly around the hips) is also common in early childhood but contracture and bony malalignment are less evident. These tend to develop in middle and late childhood. Although weakness can be a significant issue from quite early on, it becomes much more significant as children increase their bodyweight rapidly through adolescence.

Spasticity management

The focus of management in early childhood is generally on trying to reduce spasticity and a range of options are available. Although there are some anecdotal reports of responses to stem cell implants there is little scientific evidence so far that anything can be done to repair the original brain damage. Botulinum toxin is a chemical that disrupts the neuromuscular junction and thus prevents the neural input to a muscle activating it. If injected into the muscle it is selectively absorbed by these junctions and is an excellent way of suppressing activity in specific muscles. The direct effect of the toxin wears off over a period of between 3 and 9 months (Eames et al., 1999). This can be useful as it is possible to test the effects of injections without the risk of doing permanent harm but does mean that, if successful, injections need to be repeated. In children with cerebral palsy who can walk, the gastrocnemius muscles are the most commonly injected (Baker et al., 2002; Eames et al., 1999). In severe spasticity it may be more effective simply to release specific muscles surgically rather than perform repeat injections.

If spasticity affects many muscles then a specific intervention such as botulinum toxin is less appropriate. Selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR) is surgery to the spine which cuts a proportion of the nerves in the dorsal roots typically in the lumbar and sacral spine. This reduces neural activity in the reflex arc and thus reduces spasticity in all muscles innervated from that level of the spine. The word selective in SDR refers to using electromyography (EMG) during the surgery to select the rootlets to cut and how many. SDR is only suitable for a small number of children and requires highly specialised surgical teams. Another approach is to use baclofen, which is an analogue of a naturally occurring inhibitory neurotransmitter and thus suppresses spasticity generally. It can be taken orally but little of it crosses the blood–brain barrier into the cerebrospinal fluid, therefore large doses are required. Another option is to surgically insert a pump that will deliver the drug directly into the intrathecal space of the spine and is known as intrathecal baclofen (ITB). ITB tends to be used only for more severely involved children (occasionally in GMFCS III but most commonly for GMFCS IV and V).

Muscle and tendon surgery

As children age, muscle contractures generally become more significant. As these are not a direct consequence of neural activity they will not be affected by any of the spasticity reduction techniques. A variety of surgical procedures performed on either muscle or tendon are thus required. Perhaps the most common is the gastrocnemius recession in which the tendon linking the muscle to the Achilles tendon is cut. This is also referred to as Achilles tendon lengthening or heel cord lengthening. Partial releases of muscles such as the hamstrings, psoas and hip adductor muscles can also be performed to allow for more normal gait and posture. If the rectus femoris is contracted it can be useful not just to release it but to transfer its insertion from the patella (where it acts as a knee extensor) to the posterior aspect of the proximal tibia (where it may act as a knee flexor). The longer tendons of the tibialis anterior and posterior can be divided longitudinally and part of the tendon can be transferred to the other side of the foot to provide a ‘stirrup’ that can stabilise the ankle and subtalar joint in the coronal plane.

Bony surgery

Femoral anteversion and tibial torsion are rotational deformities of the bone and can be corrected by surgical procedures such as cutting the bone transversely, untwisting the bone and attaching a metal plate by screws to hold the bone in this new alignment while it heals. External fixation may also be used to correct rotational deformities. Bony malalignment of the feet can be corrected by performing various osteotomies to the bones of the foot. The most common of these is the calcaneal lengthening in which the calcaneus is cut through and a bone graft placed in the gap to lengthen the bone and swing the foot internally.

Joint capsule contractures can also be improved by bony surgery. Thus severe knee capsule contractures can be corrected by taking a wedge out of the anterior aspect of the distal femur. Milder contractures can be managed by guided growth. In this, staples or eight plates are inserted across the anterior aspect of the distal femoral growth plate. This prevents the bone growing anteriorly and the growth that does occur posteriorly negates the effect of the capsular contracture. Placing staples anteriorly and posteriorly can prevent any longitudinal growth and can be useful to correct any leg-length discrepancy.

In the past surgeons tended to perform the different surgical procedures on different occasions. More recently and particularly as surgeons’ confidence has grown there has been a tendency towards performing a range of different procedures, to bone and muscle, within the same operation. This is often known as single event multi-level surgery (SEMLS) acknowledging the intention that only one operation would be required.

Strengthening

Now that the importance of weakness in cerebral palsy has been acknowledged there has been considerable research into physiotherapy programmes to actively strengthen muscles (Damiano and Abel, 1998; Damiano et al., 1995, 2002; Dodd and Taylor, 2005; Dodd et al., 2002, 2003). These generally used the principles of progressive resistive strength training, which have now been demonstrated to result in increases in muscle strength in children with cerebral palsy of up to 25% (which is consistent with their use in many other conditions). Such programmes are now being used more and more routinely.

Gait analysis

Clinical gait analysis

The most obvious use of clinical gait analysis is for planning complex, multilevel orthopaedic surgery. In most cases the surgeon already knows that surgery is required, and the aim of the gait analysis is to determine exactly which combination of surgical procedures will be of most benefit to the individual child. Many centres will also perform follow-up analysis, often between 1 and 2 years after surgery to assess outcomes as part of clinical audit. This allows the clinical team to benefit from the experience in managing each child and is important to maintain and improve levels of service provision. Gait analysis can also be useful in planning botulinum toxin injections, physiotherapy, orthotic interventions and more general monitoring of progress. Unfortunately the cost, availability and time required for the analysis often precludes its use for routine clinical purposes.

We will now focus on how clinical gait analysis is able to support surgical decision making. Gait analysis is only part of this process which includes capturing gait data, performing a comprehensive physical examination and providing a biomechanical analysis of the results. The actual decision as to whether surgery is required and which procedures should be included requires consideration of a number of other issues such as medical imaging, patient's history and psychosocial background and the surgeon's competences and level of support, which are outside the scope of this book.

Clinical gait analysis works within a framework of clinical governance that ensures that the services delivered to patients are both safe and of the highest quality. This includes a commitment to evidence-based practice, which requires that all techniques used should be well established and have been the subject of rigorous research. This is different from gait analysis in an academic environment, where innovation and experimentation are encouraged.

Data capture

Most clinical services focus on obtaining good-quality kinematic and kinetic data based on the measured positions of retro-reflective markers using techniques documented elsewhere in this book. The conventional gait model (CGM) (Baker and Rodda, 2003; Davis et al., 1991; Kadaba et al., 1990; Ounpuu et al., 1996) is by far the best documented and most common approach (see Chapter 4). Other models are used but it is questionable whether they have yet been sufficiently well validated in clinical practice to satisfy the strict demands of clinical governance. Many centres will also capture EMG data either concurrently with full kinematic data or with a reduced marker set.

Children are generally asked to walk up and down in bare feet first and with the minimum walking aids to achieve a reasonable gait pattern. This information gives the best indication of what their body is capable of. They may then be asked to walk when wearing their ankle foot orthoses and any other usual walking aids to give an indication of how they usually walk. As well as capturing full three-dimensional gait analysis data, it is important to capture good-quality standardised video recordings of the child walking.

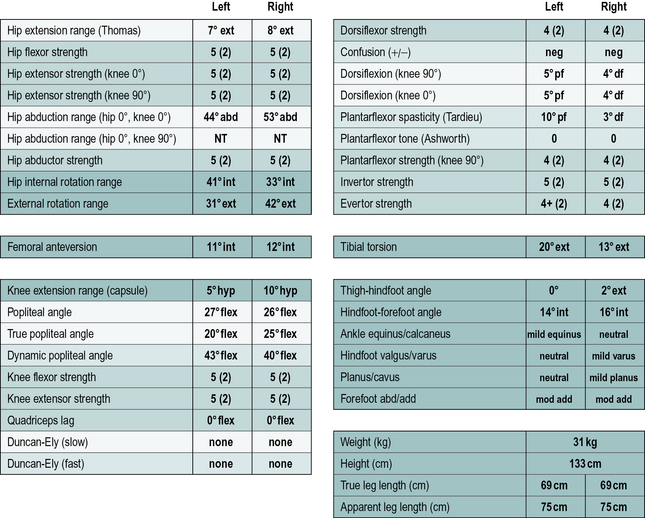

Clinical examination

In addition to the gait analysis, a full clinical examination is also completed. The range of movement of various joints is assessed which helps identify muscle and joint contractures. Muscle testing is generally carried out, grading muscles on the conventional five-point scale (Kendall and Kendall, 1949) and this is often accompanied by a simple assessment of the degree of selectivity with which the child can control muscle activation. The Tardieu test (Boyd and Graham, 1999) is used to measure spasticity and the modified Ashworth scale (Bohannon and Smith, 1987), while often referred to as a measure of spasticity, should probably be regarded as a measure of resting tone. Measures of bony malalignment such as femoral anteversion and tibial torsion are also recorded. An example of the results of such a clinical examination are included in Figure 6.3. The results of the clinical examination give additional information which aids the process of interpreting the gait analysis data to elucidate exactly which impairments are most affecting the gait pattern.

Interpretation

In the context of providing data on which to select appropriate procedures for multilevel surgery the aim of the interpretation is to list the impairments that the child has that are most affecting the walking pattern. This process can be thought of as having four stages: orientation, mark-up, grouping and reporting.

Orientation

The first thing the clinician must do is obtain a general impression of the child and how they are walking. This will require a knowledge of the diagnosis (assumed here to be cerebral palsy), motor type, GMFCS classification and topographical distribution. Scales indicating the child's general level of functions such as the Functional Assessment Questionnaire (Novacheck et al., 2000) or the Functional Mobility Scale (Harvey et al., 2007) may also be useful. It is also important to have an overview of the child's medical and surgical history and of the precise reason they have been referred for gait analysis. The final part of orientation is to look at the video to get an overall impression of the gait pattern. During the assessment the child or family should be asked whether the walking pattern adopted during the analysis is representative of the way they usually walk.

It is also necessary to get orientated to the data. Graphs with data from several walks over-plotted should be reviewed to understand how much variability the child has exhibited. If a representative trial is to be singled out for the definitive analysis then this should be checked to ensure it is representative of all walks. It is also necessary to assess the data (gait data and clinical examination) for any signs of measurement artefacts. Comparing kinematic data with the video is useful here. Video is two-dimensional and the three-dimensional data may be needed to explain what you are seeing but should not contradict it.

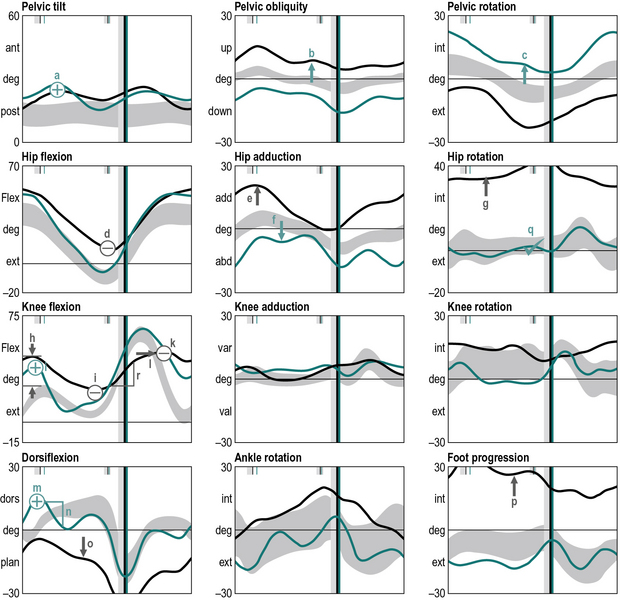

Mark-up

The next stage is to look at the data and identify gait features. These are regions of the traces that are different from reference data from a population that has no neuromusculoskeletal impairments. Many gait analysts do this in their head but it can be extremely useful to actually annotate the graphs to mark-up these features (Figure 6.4), using the symbols that are listed in Table 6.4.

|

|

Too little (during particular phase in gait cycle) |

|

|

Too much (during particular phase in gait cycle) |

|

|

Too little (throughout gait cycle) |

|

|

Too much (throughout gait cycle) |

|

|

Increased range |

|

|

Decreased range |

|

|

Abnormal slope |

|

|

Too late |

|

|

Too early |

|

|

Increased duration |

|

|

Decreased duration |

|

|

Within normal limits |

|

|

Possible artefact |

|

|

Other feature (ring around feature) |

Symbols are written on the charts in green for the right side, and black for the left side. Capital letters indicate bilateral features (including those of the pelvis).

Grouping

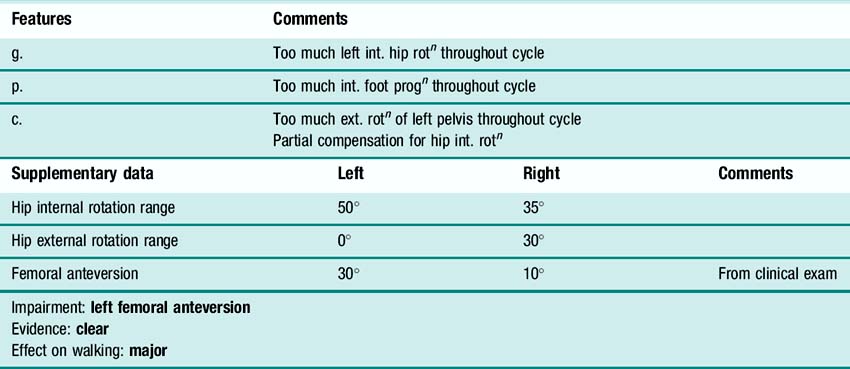

Once the gait features have been identified then the next stage of the process is to group the features that are thought to indicate the presence of a specific impairment and to relate these to relevant aspects of the clinical examination. It can be useful to list the evidence for a particular impairment as illustrated in Table 6.5.

Table 6.5 Lists some of the features and supplementary data identified in Figure 6.3 that suggest the child has femoral anteversion

Conclusion

Gait analysis is now regarded as an essential component of planning surgery for children with cerebral palsy in many parts of the world. Very general gait patterns can be identified visually but gait analysis is important because every child is affected differently by the condition. Although it is caused by brain damage which directly affects the nervous system, children also develop muscle and joint contractures, bony malalignment and muscle weakness. There are now a number of different options for improving walking ability or preventing deterioration including spasticity management, orthotics, physiotherapy and orthopaedic surgery. It is in assessing children for complex surgery that gait analysis is most often used. When a surgeon requests gait analysis he or she is generally confident that surgery is required but needs to know which particular impairments are most affecting that individual child's walking. These can be identified by identifying features within the gait data and associating these with findings from the clinical examination.

Key points

• Cerebral palsy is caused by brain damage but this leads to a wide range of impairments including spasticity, weakness, muscle and joint contracture and bony malalignment.

• Common gait deviations during swing phase include equinus, excessive flexion of the knee and hip, and foot drop.

• Common gait deviations during stance include minimal to no heel contact and excessive hip and knee flexion.

• Each child with cerebral palsy has a distinct and unique gait pattern depending on their impairments and how they compensate for these.

• There are a wide range of options for improving walking ability and preventing deterioration including botulinum toxin, selective dorsal rhizotomy, intrathecal baclofen, physiotherapy, orthotics, strengthening programmes and orthopaedic surgery.

• Gait analysis may be used to plan complex orthopaedic surgery. The goal is to identify which impairments are having the largest effect on walking from features in the gait data and the clinical examination.

Gait assessment in stroke

Worldwide, 15 million people experience a stroke each year. Of these, 5 million experience permanent disability (WHO, 2010). Disability from stroke affects millions of individuals in the USA, with over 700 000 new cases annually. US statistics show that stroke is the third leading cause of death and the leading cause of serious long-term disability. Stroke management is estimated to cost the USA $68.2 billion annually (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010).

Gait dysfunction post-stroke is common, arising from the primary impairments associated with the neurologic event as well as from secondary cardiovascular and musculoskeletal consequences from disuse and physical inactivity. Muscle weakness, tone dysfunction, impaired motor control, decreased soft tissue flexibility and reduced cardiovascular function are major contributors (Carr and Shepherd, 2003). Regaining the ability to walk is the personal rehabilitation goal most frequently declared by persons post-stroke (Bohannon et al., 1988). Walking is considered important for return to independent living and full community access. Thus, whenever, possible rehabilitation professionals provide gait examination and rehabilitation as part of post-stroke management.

Temporal and spatial parameters

Post-stroke gait is frequently characterised as slow and asymmetrical (Hesse et al., 1997; Olney and Richards, 1996; Roth et al., 1997; Woolley, 2001) with reduced cadence (Woolley, 2001) and there is significant inter- and intra-subject variability (Olney and Richards, 1996; Woolley, 2001). Several authors suggest that hemiparetic gait deviations may be related to reduced gait speed (Carlsoo et al., 1974; Lehmann et al., 1987; Mizrahi et al., 1982; Roth et al., 1997; Wagenaar and Beek, 1992; Woolley, 2001). Roth and colleagues (1997) investigated the correlation between gait speed and 18 other temporal gait parameters for 25 people post-stroke. Since post-stroke gait speed was related to most, but not all, other temporal gait characteristics, the authors suggest that clinical gait examination must include gait speed with descriptions of asymmetry and paretic limb stance and swing phase durations and proportions. Many other spatiotemporal parameters frequently change post-stroke, including increased double support time, increased stance time by the non-paretic limb, shortened paretic limb step length, a moderately wider base of support, and slightly greater toe out angles (Carr and Shepherd, 2003; Montgomery, 1987; Olney and Richards, 1996; Perry, 1969; Shumway-Cook and Woollacott, 2007; Woolley, 2001).

Balasubramanian and colleagues (2009) explored temporal and spatial gait characteristics for an age-matched healthy control group and post-stroke groups of varying severity (severe, moderate, mild), step symmetry (longer, shorter, symmetrical) and fall risk (Dynamic Gait Index (DGI) ≤ 19 and DGI > 19). The authors confirmed increased variability in step length, swing, pre-swing and stride times during hemiparetic walking as compared with normal gait. For subjects post-stroke, paretic leg swing time variability was increased compared with the non-paretic limb during gait. Between-leg differences in variability for other spatiotemporal characteristics were revealed in the participants with the most impaired performance. Slower walkers (speed < 0.4 m/s) had significantly reduced step width variability as compared to age-matched controls. Patla et al. (2002) previously suggested that adaptation of step length, width, and height are important gait strategies employed by persons post-stroke to avoid obstacles and maintain balance. Balasubramanian and colleagues (2009) went on to explore gait characteristics’ impact on function, by comparing gait characteristics across groups. They found that the post-stroke groups with increased step length variability and reduced step width variability also had poor performance outcomes (severe hemiparesis, asymmetric step and DGI ≤ 19). The authors ultimately suggest that the presence of decreased step width variability as well as increases in the variability of other gait parameters correlate strongly with impaired walking performance.

Kinematics

Common post-stroke gait deviations have been described (Brandstater et al., 1983; Burdett et al., 1988; Carr and Shepherd, 2003; Lehmann et al., 1987; Moore et al., 1993; Moseley et al., 1993; Olney and Richards, 1996; Pelissier et al., 1997; Perry, 1969; Shumway-Cook and Woollacott, 2007; Woolley, 2001).

For the paretic limb during stance phase these include:

• Decreased forward propulsion

• Forward flexion of the trunk with weak hip extension and/or hip flexion contracture notably contributing to a lack of hip extension in terminal stance

• Decreased or increased lateral pelvic displacement

• Poor hip position in hip adduction and/or flexion

• Trendelenburg limp caused by weak hip abductors

• Leg scissoring caused by spastic hip adductors and/or muscle substitution for weak hip flexors

• Excessive knee flexion in early and/or late stance

• Knee hyperextension during forward progression in mid-stance

• Equinovarus foot position with absent or inadequate heelstrike

• Decreased dorsiflexion with mid-stance forward progression

For the paretic limb during swing phase these include:

• Inadequate forward pelvic rotation

• Vaulting on non-paretic stance limb

• Inadequate and/or delayed hip flexion with abnormal substitutions such as hip circumduction, hip external rotation and/or adduction

• Inadequate knee flexion in early swing

• Poorly controlled knee extension, particularly prior to heelstrike

• Persistent ankle/foot equinus or equinovarus

• Foot drop/toe drag or exaggerated dorsiflexion

• Excessive use of momentum resulting in an uncontrolled swing.

Moseley et al. (1993), Moore et al. (1993) and colleagues collectively hypothesise that both stance and swing phase gait deviations may be the result of an inability to selectively activate and coordinate muscle activity and/or maladaptive muscle shortening.

Olney and colleagues (1991) documented bilateral leg joint angles for individuals post-stroke walking at slow, medium and fast speeds. Joint angle amplitudes or joint ranges of motion differed from norms and present at all gait speeds. Considered clinically significant were the decreased amplitudes of knee flexion during swing and hip extension during stance for the paretic limb. A correlation between walking speed and maximum ankle plantarflexion on the non-paretic side was also documented. Hesse and colleagues (1997) first described significant differences in timing, step length, mediolateral displacement of the centre of pressure and centre of mass movement velocity patterns when persons post-stroke initiated gait with the affected versus the non-affected limb. Bensoussan et al. (2006) extended Hesse's work to assess the kinetic and kinematic gait initiation characteristics of three subjects post-stroke with spastic equinovarus foot and three control subjects. They observed that subjects post-stroke had asymmetrical movement strategies such as decreased support phase of the paretic limb when the non-paretic limb initiated gait; asymmetrical body weight distribution with the non-paretic limb accepting greater weight; more pronounced propulsive forces in the non-paretic versus the paretic limb; increased knee flexion during initial swing phase to accommodate for the equinovarus; and paretic limb flat foot initial contact.

Lu et al. (2010) studied gait during an 8 m walk and crossing obstacles of three different heights for both limbs for high-functioning individuals with chronic stroke (able to walk 100 m without an assistive device and Berg Balance Score > 50). High-functioning individuals post-stroke had significantly different joint kinematics compared with an age-matched healthy control group, including greater leading toe clearance for clearing an obstacle, trailing toe obstacle distance, and posterior pelvic tilt regardless of leading limb. No significant differences were found for gait speed. The authors conclude that individuals post-stroke who are able to function at a high level develop a specific bilateral symmetrical strategy including increasing posterior pelvic tilt and elevating the swing toe. This strategy probably provides a more posterior placement of the trailing limb, increasing leading toe clearance during obstacle clearance, and preventing tripping.

Kinetics

Similar to gait spatiotemporal characteristics, force patterns post-stroke are described as highly variable between individuals as well as between paretic and non-paretic limbs (Carlsoo et al., 1974; Hesse et al., 1993; Marks and Hirschberg, 1958; Woolley, 2001; Wortis et al., 1951). Reduced vertical loading and significant variability of loading on initial contact has been documented for the paretic and non-paretic limbs post-stroke (Marks and Hirschberg, 1958; Wortis et al., 1951). Hesse and colleagues (1993) documented an increase in vertical loading after initial contact on the paretic limb as compared with the non-paretic limb as well as delayed loading after initial contact, premature unloading and reduced vertical push-off forces at terminal stance. Iida and Yamamuro (1987) reported significantly greater post-stroke medial-lateral centre of gravity displacement widths as compared with normal controls. They also described these differences to be more pronounced for individuals with more severe stroke.

Gait muscle activation patterns have been extensively studied in persons post-stroke. Well established is the high variability post-stroke in muscle firing magnitudes and phasic patterns between limbs and between individuals post-stroke (Carlsoo et al., 1974; Dimitrijevic et al., 1981; Peat et al., 1976; Richards and Knutsson, 1974; Takebe and Basmajian, 1976; Woolley, 2001). In a review of hemiplegic gait characteristics, Woolley (2001) concluded that the general muscular firing changes post-stroke include reduced magnitude for paretic limb muscles as well as premature onset and prolonged duration of firing across stance and swing phases for muscles in both limbs. Peat and colleagues (1976) reported a tendency for post-stroke paretic limb muscle activity to collectively peak at the same time after stance weight acceptance. A few studies have resulted in classification systems based on EMG patterns (Dimitrijevic et al., 1981; Knutsson and Richards, 1979; Waters et al., 1982), but none have gained broad translation for practical use in the clinic.

Nasciutti-Prudente and colleagues (2009) examined the relationships between muscular torque and gait speed in individuals post chronic stroke. They only identified one muscle group, paretic knee flexors, to have significant impact for predicting gait speed post-stroke. The paretic knee flexors accounted for 61% of the variation in gait speed, consistent with a previous study which identified paretic knee muscle strength as a moderate to strong predictor of walking ability in individuals post chronic mild to moderate stroke (Flansbjer et al., 2006).

It has been suggested that for the typical person post-stroke, walking requires approximately 50% to 67% more metabolic energy expenditure than that of a healthy person walking at the same speed (Corcoran et al., 1970) and that the paretic leg performs approximately 40% of the mechanical work of walking (Olney et al., 1991). Bowden and colleagues (2006) examined the effect of leg paresis on anterior-posterior ground reaction forces for individuals with varying levels of hemiparetic severity post-stroke. They documented a percentage of total propulsion generated by the paretic leg at 16% for severe hemiparesis, 36% for moderate hemiparesis and 49% for mild hemiparesis.

One clinical point of concern is the possible effect of gait compensation, such as hip hiking, vaulting, or knee hyperextension, on the non-paretic limb post-stroke. Kerrigan and colleagues (1999) estimated the non-paretic limb torques in all three planes about the hip, knee, and ankle for individuals with spastic paresis and stiff-legged gait post-stroke. They compared average stresses of the non-paretic leg with normal controls. In general, average peak non-paretic limb torque was not significantly different from that of controls, suggesting that the risk for biomechanical injury over time was minimal. This is counter to what clinicians might intuitively anticipate. More research is needed before clinicians may accurately anticipate the effects of long-term stroke compensation.

Clinical management

Already established in the rehabilitation community is the criterion of 1.1–1.5 m/s gait speed for safe pedestrian walking across different environmental and social contexts. Unfortunately only approximately 7% of patients post-stroke are discharged from rehabilitation able to walk 500 m continuously at a speed necessary for safe street crossing (Hill et al., 1997). Much more research is needed to establish best practices for regaining safe community-level gait.

Many persons post-stroke are either directed to or independently elect to use a unilateral assistive walking device. Kuan and colleagues (1999) studied the temporal and spatial gait characteristics of 15 subjects post acute stroke and nine age-matched healthy control subjects walking with and without a cane. They found that cane use had more of an effect on gait spatial variables than on temporal variables for subjects post-stroke. Gait phases remained similar regardless of cane use. For subjects post-stroke using a cane, the paretic side had increased pelvic obliquity, hip abduction and ankle eversion during terminal stance; increased hip extension, knee extension, and ankle plantarflexion during pre-swing; and increased hip adduction, knee flexion and ankle dorsiflexion during swing as compared with walking without the cane. The authors concluded that persons post-stroke may have improved spatial gait characteristics, including enhanced centre of mass translation and push-off in stance and decreased circumduction in swing, when using a cane.

Orthoses are also devices commonly considered for prescription post-stroke. Lewallen and colleagues (2010) documented gait characteristics for 13 individuals using an orthosis post-stroke, specifically solid, articulated and posterior leaf spring ankle foot orthoses. They found that gait was most impaired for those individuals wearing the solid ankle foot orthosis with a significant decrease in step length and gait speed. Use of the solid orthosis also resulted in slower decline walking compared with incline and walking over a level surface. Lehmann and colleagues (1987) reported a correlation between improved gait speed and ankle foot orthosis-related stance phase duration. A 5° dorsiflexed orthotic ankle angle contributed to increased walking speed and increase in heelstrike as compared with walking with no orthotic or when the orthotic was set in 5° of plantarflexion. The effect of a neutral ankle orthotic setting was not explored.

Also of interest to clinicians is the potential relevance of footwear choice to gait and balance for individuals post-stroke. Inadequate footwear has been identified as a fall risk factor for the elderly (Menz and Lord, 1999; Menz et al., 2006; Sherrington and Menz, 2003). While much more research is needed, footwear choice is probably important (Hesse et al., 1996; Ng et al., 2010). Ng and colleagues (2010) documented that a majority of their study participants preferred loose-fitting slippers for indoor walking over closed-fitting shoes and barefoot. Only 23% of participants reported that they had received advice about wearing appropriate footwear. The authors concluded that for proper ground contact, stability and proprioceptive input, it is reasonable to recommend shoes with broad flat heels, firm heel counter, thin firm mid-sole, laces or other fixation, and adequate slip resistance.

Key points

• Clinicians should expect high gait variability within and between patients post-stroke.

• Gait speed, using a standardised clinical protocol such as the 10 m walk, is an essential clinical measurement.

• To improve gait speed, knee flexion strength may be an important post-stroke measure as well as an intervention target.

• Gait intervention post-stroke must be individualised and based on the specific patient's demonstrated gait dysfunction.

• Intervention methods will likely involve improving flexibility, strength and task-specific ambulation activities.

• Gait training may incorporate both treadmill and over-ground walking, with specific attention to speed and safety within various functional environments.

• Environmental constraints must be considered when establishing goals for persons post-stroke.

• Devices, including canes, orthotics and footwear, are likely to impact gait characteristics on an individual basis. Exactly which gait characteristics change and to what extent, are yet to be determined. Gait analysis can be helpful to determine optimal use of these devices.

Gait assessment in Parkinson's disease

Parkinsonism is a disorder of the extrapyramidal system, caused by degeneration of the basal ganglia of the brain and is a common condition that affects motor function and gait. Parkinson's disease is a significant cause of morbidity with an estimated prevalence of 1.8% in those over 65 in Europe (de Rijk et al., 2000) with disease progression linked with a significant decline in quality of life (de Boer et al., 1996). The exact causal mechanism is not yet fully understood, however it is associated with a significant decrease in the number of dopaminergic neurons and an increase in the presence of Lewy bodies, tiny spherical protein deposits found in nerve cells whose presence in the brain disrupt the action of important chemical messengers. Diagnosis of Parkinson's disease is based on the presence of two or more of the following symptoms: tremor, rigidity, postural instability and akinesia. Akinesia is defined as a lack, or poverty of movement which can be subdivided into: slowness and unskilful movement secondary to rigidity, a lack or poverty of movement and difficulty in initiation of movement know as freezing.

Early analysis of gait in Parkinson's disease focused on temporal and spatial characteristics such as speed and step length, with Knutsson (1972) being one of the first to use gait analysis techniques to report the temporal and spatial parameters of gait in Parkinson's disease. Murray et al. (1978) conducted the first kinematic assessment of the gait of 44 men with parkinsonism using interrupted-light photography to record the displacement patterns of multiple body segments during free-speed and fast walking to quantitatively characterise their gait patterns and identified the following abnormalities:

1. Stride length and speed were very much reduced, although cycle time and cadence were usually normal

2. The walking base was slightly increased

3. The range of motion at the hip, knee and ankle were all decreased, mainly by a reduction in joint extension

4. The swinging of the arms was much reduced

5. The majority of patients rotated the trunk in phase with the pelvis, instead of twisting it in the opposite direction

6. The vertical trajectories of the head, heel and toe were all reduced, although others have commented on a distinct ‘bobbing’ motion of the head.

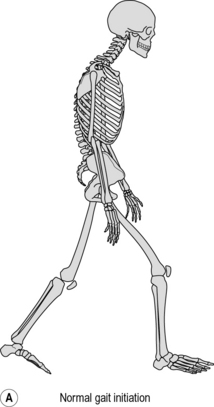

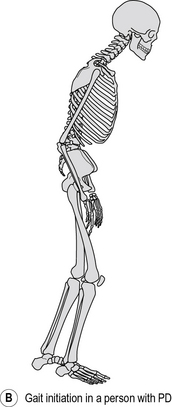

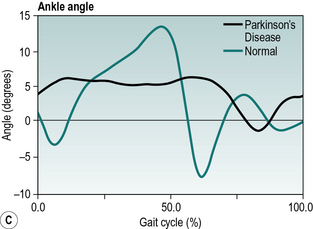

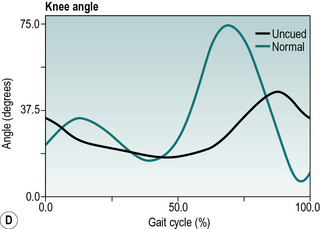

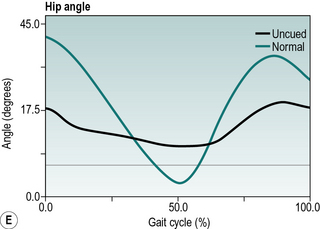

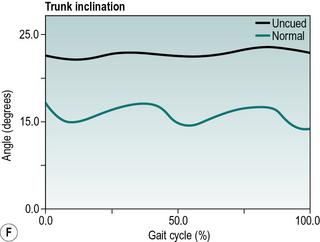

Parkinsonian gait is now widely recognised by a characteristic stooped and shuffling appearance (Samii et al., 2004). This includes a reduction in extension during late stance phase and a reduction in flexion during mid-swing coupled with a forwards inclination of the trunk (Fig. 6.5). The ‘shuffling’ gait occurs because the foot is still moving forward at the time of initial contact. In some patients initial contact is made by the flat foot; in others there is a heelstrike but with the foot being much more horizontal than usual. Some patients also show scuffing of the foot in mid-swing. Unlike most gait patterns, which stabilise within the first two or three steps, the gait of patients with parkinsonism often ‘evolves’ over the course of several strides. Figure 6.5 show steady state walking in an individual with Parkinson's disease compared with an age- and gender-matched normal subject.

Fig. 6.5(A–F) • Ankle, knee, hip and trunk sagittal plane angles during gait in an individual with Parkinson's disease and an age matched normal individual.

Clinical management

One of the most well-validated treatments for Parkinsonism is L-DOPA which is a dietary precursor to dopamine. L-DOPA is converted to dopamine which improves the motor symptoms of rigidity and the ability to start and continue movements (bradykinesia) (Durrieu, 1998; Stowe et al., 2008; van Hilten et al., 2007). L-DOPA is recognised to have a short response (several hours) and a long response (several days or weeks) which both contribute to symptoms relief. Newly treated patients typically experience a ‘honeymoon period’ where the effects of L-DOPA help significantly, typically for several years. As time progresses this honeymoon period ends and the patient becomes more globally affected. As Parkinson's disease progresses patients experience motor fluctuations and other autonomic symptoms as the short response comes to an end (Morris et al., 2001), people with Parkinson's typically experience this as distinct on and off phases.

Morris et al. (1996) found that both gait speed and step length increased while on L-DOPA and although the gait parameters were repeatable when on medication they fluctuated greatly in the off phase of medication. O'Sullivan et al. (1998) found L-DOPA produced a significant increase in walking speed but not cadence, which again indicates that L-DOPA increases stride length, which was further confirmed by Defebvre et al. (2002). Ferrarin et al. (2004) used gait analysis to describe the inclination of the trunk and found a significantly reduced forward inclination or stooped gait pattern in Parkinson's disease patients on L-DOPA.

In addition to gait analysis clinical assessments are used. The Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) which is a validated scale for severity of Parkinson's disease, is commonly used (Box 6.1). The UPDRS has four components which have been largely derived from pre-existing scales. Parts II and III have the greatest relevance to gait analysis. Part II evaluates activities of daily living in both the on and off phases which include falling, freezing when walking and walking. Part III is an assessment of motor capabilities and includes arising from a chair, posture, gait, postural stability, and body bradykinesia and hypokinesia.

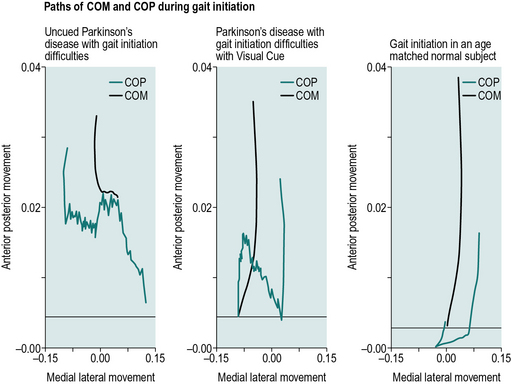

Gait initiation problems in people with Parkinson's disease

Difficulties in initiation of movement known as freezing or motor blocks, remains one of the most debilitating aspects of Parkinson's disease (Halliday et al., 1998). Giladi et al. (1992) studied 990 people with Parkinson's disease and found 318 had motor blocks, 86% of these had blocks in initiation of gait, 45% had blocks in turning, 25% had blocks in doorways, and 23% had blocks in open runways. Therefore gait initiation affected the largest number of subjects with motor blocks, which accounted for 27% of the people with Parkinson's disease investigated.

Hass et al. (2005) investigated gait initiation and dynamic balance control in people with different severities of Parkinson's disease. They found that the peak magnitude of the centre of pressure (COP) to centre of mass (COM) distance was significantly greater during the end of the single-support phase in the less disabled patients than in more balance disabled patients. The differences in COP–COM distances between the groups suggest that people with Parkinson's disease who have impaired postural control produce shorter COM–COP distances than people without a clinically detectable balance impairment, which is an adaptation to prevent falls. Hass et al. (2005) concluded that this method of evaluation could prove a useful quantitative index to examine the impact of interventions designed to improve ambulation and balance in Parkinson's disease.

Jiang and Norman (2006) investigated the effects of visual and auditory cues on gait initiation in people with Parkinson's disease. Jiang and Norman found a mean difference in the maximum forward propulsive force between people with Parkinson's disease who freeze and do not freeze. Jiang and Norman also found a difference in the maximum horizontal force between the different cues. The auditory cues were rhythmic sounds with an interval matching the subject's average step time. The visual cues were high-contrast transverse lines on the floor adjusted for the subject's first step length and overall height. They found that transverse line visual cues improved gait initiation, while auditory cues had no effect. Although the use of high-contrast transverse lines on the floor can be applied to the home setting these are not readily available in the community setting.

Portable cueing aids aimed at helping people overcome difficulties in initiating walking or ‘freezing’ are becoming more common. McCandless et al. (2011) studied the effectiveness and acceptability of several of these devices on people with Parkinson's disease with gait initiation difficulties. Five randomised conditions were tested: laser cane, sound metronome, vibrating metronome, walking stick and uncued. Significant differences were seen in step length and COM and COP movement in the anterior/posterior and medial/lateral directions between freezing and non-freezing episodes. Significant improvements were seen in the COM and COP movement when using the laser cane and the walking stick and greater step length when using the laser cane during the freezing episodes. Participants rated the perceived effectiveness of the devices, which showed a significant improvement in satisfaction when using the laser cane for both starting and maintaining walking. Figure 6.6 shows the COM and COP patterns for uncued, cued using a laser cane and age- and gender-matched gait initiation. The cued condition improves the medial lateral movement of the COP and the anterior movement of the COM, however, there is still substantially less movement forwards when compared to the age- and gender-matched normal individual.

Conclusion

Gait analysis for both steady state gait and gait initiation is becoming more widely accepted as a sensitive tool for assessing Parkinson's disease. While general gait patterns can be identified, there is considerable variability of patients in particular when in the off treatment phase. However, the use of clinically based gait analysis is restricted to a small number of specialist clinics.

Key points

• Trunk inclination and hip flexion/extension are useful clinical outcome measures, however, temporal and spatial parameters are also good clinical markers.

• Clinicians should expect considerable gait variability between patients and between the on and off phases of the same patient.

• It is important to assess both steady-state gait and gait initiation in people with Parkinson's disease.

• L-DOPA improves the motor symptoms of rigidity and the ability to start and continue movements.

• Devices including walking aids and visual cues have been shown to improve gait characteristics and gait initiation. However, further work is required to determine the most effective devices in the community setting.

Gait assessment in muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy (MD) describes a diagnostic subgrouping of progressive neuromuscular diseases resulting from genetically linked, non-inflammatory, myopathic disease. Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), the most common paediatric-onset neuromuscular disease with an incidence of 1:3500–6000 males, leads to progressive deterioration of gait mechanics as the disease progresses (Bushby et al., 2010). The combined effect of weakness resulting from the death of healthy muscle tissue and the hypoextensibility caused by deposition of fatty and fibrous tissue within the muscle produce relatively predictable changes in posture and movement patterns of children with DMD during the first two decades of life (Rahbek et al., 2005).

Considerable variance has been documented in timing of onset and speed of progression of DMD, however the typical clinical presentation is a functional deterioration of movement capacity in the lower extremities usually presenting 2–3 years before weakness in the upper extremities. This contributes significantly to the early compensatory patterns observed in children with DMD as they learn to accommodate for weaker muscle groups by modifying joint alignment and muscle firing patterns. Early in the disease progression, children with DMD will reduce their walking speed as a subtle means of altering gait kinematics to more easily advance the leg during swing phase and to reduce the energy expenditure of walking (Campbell et al., 2012; Perry and Burnfield, 2010). A classic motor adaptation strategy demonstrated by children with DMD is the Gower's sign, where the arms are used to push against the thigh to assist with hip extension upon rising from sitting (Campbell et al., 2012).

The insidious nature of onset of this disorder between 2 and 5 years of age combined with these compensatory movement patterns may contribute to delayed identification of the early impairments associated with DMD. Monitoring changes in muscle strength and range of motion over time are essential examination components to help distinguish age-related variances in typical development from the atypical developmental trajectory demonstrated by children with DMD. Goniometric measurements or analysis of functional movement patterns can provide relatively objective assessments of change in joint mobility across all ages. However, obtaining reliable objective strength measures in very young children can be challenging. In children older than 5 years of age, classic manual muscle testing (MMT) can generally be applied to obtain serial strength measures. In older children, an alternative method for measuring decline in strength of specific muscle groups over time to more precisely interpret altered gait mechanics is quantitative muscle testing (QMT). QMT measures isometric force production capacity by using a force gauge to directly assess contractile activity in a particular muscle group while ensuring constancy of muscle length, joint angle and velocity (Stuberg and Metcalf, 1988). In addition to the specialised equipment required, the child must also demonstrate qualities of cooperation, motivation, attention and understanding of instructions to support reliable application of the QMT.

The diagnosis of DMD is most often made between 2 and 5 years of age, with the lack of gait maturation being one of the early hallmark signs. Early gait pathomechanics coupled with reports of walking reluctance, increased clumsiness with frequent falls, laboured efforts required to come to stand (as compared with age-matched peers) and absent heelstrike are common early clinical presentations (Campbell et al., 2012). Sutherland et al. (1981) categorized gait disturbances of children with DMD into three groups: early, transitional and late ambulators. When examining the gait variables of 21 youngsters with DMD across these groups, these researchers identified three gait characteristics as predictors of disease progression with 91% accuracy: cadence, dorsiflexion in swing and anterior pelvic tilt. Apart from the positive Gower's sign, the most notable early gait changes include altered cadence, a slight increase in hip flexion during swing phase and a decreased ankle dorsiflexion with foot drop occurring as the cadence continues to decrease. Associated with these gait pattern changes, the ground reaction force passes anterior to the knee joint during early single limb support with muscle weakness, most notably in the quadriceps. When examining gait patterns of a relatively homogeneous group of 21 children with DMD with a mean age of 72 ± 8.2 months, D'Angelo et al. (2009) confirmed previously reported data demonstrating excessive anterior tilt of the pelvis and abnormal knee pattern loading response. Additionally, these researchers reported significantly lower stride length values, significantly higher step width values with higher flexion and abduction movement patterns used to advance the limb during swing phase as compared with age-matched peers. When examining the effects of gait velocity on gait patterns of an older cohort of children with DMD between 7 and 15 years of age, Gaudreault et al. (2010) reported higher cadence, shorter step length, a lower hip extension moment, a minimal or absent knee extension moment and reduced or absent dorsiflexion moment at heelstrike when compared with age- and gender-matched peers. Gaudreault et al. (2009) had previously examined the contribution of plantar flexion contractures during the gait of 11 children with a confirmed diagnosis of DMD with a mean age of 9.2 ± 2.6 and reported that increased net plantar flexion moments at the end of the lengthening phase of the plantar flexors and forward shift of the COP served to help the children ambulate independently despite significant weakness in extensor forces.

During the late stage of ambulation, children with DMD demonstrate a marked increase in work output associated with a marked exaggeration of gait pathomechanics. Functional compensation for the increasing weakness in the gluteus maximus muscle produces an exaggerated anterior pelvic tilt with associated restricted hip extension during stance phase. Inability to maintain pelvic alignment during stance phase due to gluteus medius muscle weakness results in a positive Trendelenburg's sign (where the non-weight-bearing hip drops during single leg stance) and emergence of Trendelenburg gait pattern characterised by lateral flexion of the trunk towards the weight-bearing side resulting in increased shoulder sway and widened base of support. These gait alterations make it possible for the child with DMD to maintain the force line behind the hip joint and in front of the knee joint throughout single-limb support, thereby helping to rely on deep joint structures to assist in the maintenance of upright stance as a compensation for increasing weakness in hip and knee extensor muscles.

Reliable prediction of cessation of independent ambulation is an important management consideration for individuals with DMD. Sienko-Thomas et al. (2010) suggested that the loss of knee flexion in loading response may be an indicator of impending loss of ambulation while Bakker et al. (2002) found that strength loss in hip extension and dorsiflexion are the primary predictors. Siegel (1986) found that when the combined lag angle of active antigravity hip extension in prone (starting with hip flexed to 90°) and active knee extension in sitting (starting with the knee flexed to 90°) exceeds 90°, loss of independent ambulation is likely to occur within a few months. Other reported clinical methods to identify impending cessation of independent ambulation include a manual muscle test (MMT) of below grade 3 for hip extensor or below grade 4 for ankle dorsiflexors (McDonald et al., 1995), reduction in lower extremity strength by greater than 50% and prolonged time to ascend four standard steps (Brooke et al., 1989).

Clinical management

Advances in medical and pharmaceutical management of children with DMD have resulted in a change of the natural history of the disease process with increasing numbers of the children diagnosed with DMD surviving to adulthood. Advances have included delayed cessation of ambulation, delayed development of contractures and reduced numbers of surgical corrections, reduced use of long leg orthotics, decreased incidence of scoliosis and corrective back alignment surgeries, delayed pulmonary function decline, and increased survival into early adulthood. Moxley et al. (2010) reported an increase in mean survival to 30 years of age during the decade of the 2000s, with the potential for that age to further increase in the present decade. This represented an increase of almost 5 years between 1990 and 1999 as compared with 2000 and 2009. As preventive management of children with DMD becomes more precise, and as the survival likelihood continues to increase, it is important for clinicians to monitor gait pattern carefully for signs of impending degeneration.

To better understand the management needs of children with DMD across the lifespan, the International Standard of Care Committee for Congenital Muscular Dystrophy convened a 3-day workshop in Brussels, Belgium, in November 2009, to develop a consensus statement based on input from experts in the field and from families directly impacted by DMD (Wang et al., 2010). Management recommendations to meet the emerging needs of individuals with DMD across the lifespan drawn from the consensus statement on standard for care for congenital muscular dystrophies developed during that meeting include: coordinating transition of care from paediatric to adult services; identifying and planning for post-secondary educational and vocational needs; preparing patients to manage their own healthcare needs; supporting patients and families in making decisions regarding advance care directives; and advocating for services to meet independent living needs, aide services and healthcare coverage (Wang et al., 2010).

DMD is a representative example of multiple progressive neuromuscular disorders that result in altered gait characteristics. Understanding the underlying factors impacting gait pathomechanics in clients with muscular dystrophy provides essential information to support optimal quality of life and promote prolonged independent ambulation for these individuals.

Key points

• Quadriceps insufficiency is the key factor influencing compensatory postural adaptations of increased anterior pelvic tilt, restricted hip extension in stance and equinus posturing.

• Displacement of the weight-bearing force line anterior to the knee joint and posterior to the hip joint coupled with plantarflexion muscle tightness helps support independent ambulation despite significantly reduced extensor force generation capacity.

• Timing of cessation of independent ambulation may be reliably predicted.

• Advances in medical management leading to increasing life expectancy warrants inclusion of transition services as children with DMD transition from paediatric to adult services.

Baker R., Rodda J. All you ever wanted to know about the conventional gait model but were afraid to ask (CD-ROM). Melbourne: Women and Children's Health; 2003.

Baker R., Jasinski M., Maciag-Tymecka I., et al. Botulinum toxin treatment of spasticity in diplegic cerebral palsy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol.. 2002;44(10):666–675.

Bakker J.P., de Groot I.J., Beelen A., et al. Predictive factors of cessation of ambulation in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil.. 2002;81:906–912.

Balasubramanian C.K., Neptune R.R., Kautz S.A. Variability in spatiotemporal step characteristics and its relationship to walking performance post-stroke. Gait Posture. 2009;29:408–414.

Bensoussan L., Mesure S., Viton J., et al. Kinematic and kinetic asymmetries in hemiplegic patients’ gait initiation patterns. J. Rehabil. Med.. 2006;38:281–294.

Bohannon R.W., Smith M.B. Interrater reliability of a modified Ashworth scale of muscle spasticity. Phys. Ther.. 1987;67(2):206–207.

Bohannon R.W., Andrews A.W., Smith M.B. Rehabilitation goals of patients with hemiplegia. Int. J. Rehabil. Res.. 1988;11:181–183.

Bowden M.G., Balasbramanian C.K., Neptune R.R., et al. Anterior-posterior ground reaction forces as a measure of paretic leg contribution in hemiparetic walking. Stroke. 2006;37:872–876.

Boyd R.N., Graham H.K. Objective measurement of clinical findings in the use of botulinum toxin type A for the management of children with cerebral palsy. Eur. J. Neurol.. 1999;45(Suppl. 96):10–14.

Brandstater M.E., de Bruin H., Gowland C., et al. Hemiplegic gait: analysis of temporal variables. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.. 1983;64:583–587.

Brooke M.H., Fenichel G.M., Grigs R.C., et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: patterns of clinical progression and clinical effects of supportive therapy. Neurology. 1989;39:475–481.

Burdett R.G., Borello-France D., Blatchly C., et al. Gait comparison of subjects with hemiplegia walking unbraced, with ankle-foot orthosis, and with Air-Stirrup Brace. Phys. Ther.. 1988;68:1197–1203.

Bushby K., Finkel R., Birnkrant D.J., et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy Part 1. Lancet Neurol.. 2010;9:177–189.

Campbell S.K., Palisano R.J., Orlin M.N. Physical Therapy for Children, fourth ed. St. Louis, MO: WB Saunders/Elsevier; 2012.