Growth and Development: Infancy through Adolescence

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Describe prenatal development.

2 Compare the development of the male and the female.

3 Discuss Freud’s theory of personality and the mind.

4 Explain the stages of Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development.

5 Explain the stages of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.

6 Discuss moral development according to Kohlberg.

7 Identify the principles of growth and development.

8 Describe the physical development of children.

9 Identify two pros and two cons of early childhood education.

10 Discuss age-appropriate discipline measures for children.

11 Explain the male and female physical changes of puberty.

12 Identify developmental tasks of adolescence.

13 Discuss at least three concerns related to adolescence.

1 Explain the importance of regular prenatal health care.

2 Discuss recommended feeding patterns for newborns and older infants.

3 Explain the importance of screening young children for physical development.

4 Provide health promotion teaching to parents and school-age children.

5 Explain how parents and other caregivers can encourage age-appropriate cognitive and psychosocial development.

abortion (p. 142)

autonomy ( , p. 146)

, p. 146)

bonding (p. 145)

cephalocaudal ( , p. 144)

, p. 144)

cognitive (p. 137)

conception (p. 139)

ego (p. 139)

egocentric ( , p. 146)

, p. 146)

embryonic ( , p. 142)

, p. 142)

fetal (p. 142)

gender (p. 141)

gender roles (p. 147)

genes ( , p. 142)

, p. 142)

germinal ( , p. 142)

, p. 142)

id (p. 139)

ideology ( , p. 153)

, p. 153)

initiative ( , p. 146)

, p. 146)

intelligence (p. 149)

morals (p. 147)

Moro reflex (p. 143)

neonate ( , p. 143)

, p. 143)

peers (p. 147)

prepuberty ( , p. 148)

, p. 148)

psychosocial ( , p. 137)

, p. 137)

puberty (p. 151)

reflexes ( , p. 143)

, p. 143)

self-concept (p. 149)

sensorimotor ( , p. 144)

, p. 144)

sexual orientation (p. 153)

siblings (p. 141)

social competence ( , p. 149)

, p. 149)

superego (p. 139)

theory (p. 139)

time-out (p. 147)

trimesters ( , p. 142)

, p. 142)

vernix caseosa ( , p. 143)

, p. 143)

viable ( , p. 142)

, p. 142)

zygote ( , p. 142)

, p. 142)

The study of human development is fascinating. It is the study of how people change, and stay the same, over time. Each of us is a unique person who continues to develop throughout life. The more you learn about human development, the more you will appreciate the complexity of life. Studying human development may help you better understand yourself and others.

In some ways, people show consistency from one stage of life to another. Some personality traits, for example, appear early in childhood and persist through life. In other ways, such as physical development, people change as they get older. The chapters in this unit focus on three aspects of human development: physical, cognitive (knowledge and thinking processes), and psychosocial (personality, getting along in society). The physical aspect is easy to understand; we can see children grow. Physical development begins at conception (union of ovum and sperm), continues into young adulthood, and includes the normal changes of later adulthood. Cognitive and psychosocial development also begin early in life and continue throughout the life span.

These three facets of human development, physical, cognitive, and psychosocial, are not separated. Each interacts with the others. Every person is a combination of all three. They are discussed separately for the purposes of study and observation.

People do change over time. We influence our own development through choices that we make. Only humans can do that! We are resilient and flexible; we can bounce back, adapt, and get stronger.

AGE-GROUPS

The growth and development of children and adolescents can be divided into these common age groupings:

• Prenatal = conception to birth

• Infancy = birth to 18 months

• Early childhood = 18 months to 6 years

These divisions are only for the purpose of study. Each individual’s development is unique. You cannot judge someone’s development without considering physical, cognitive and psychosocial aspects. Family and cultural factors must also be included when trying to make an assessment. Boundaries of each group should be considered flexible when assessing an individual.

THEORIES OF DEVELOPMENT

A theory (an idea formed by reasoning from facts), especially about human development and behavior, is based primarily on observations. Theories are attempts to explain something; they are always being adapted to new information. More information about the following theorists can be found in psychology references.

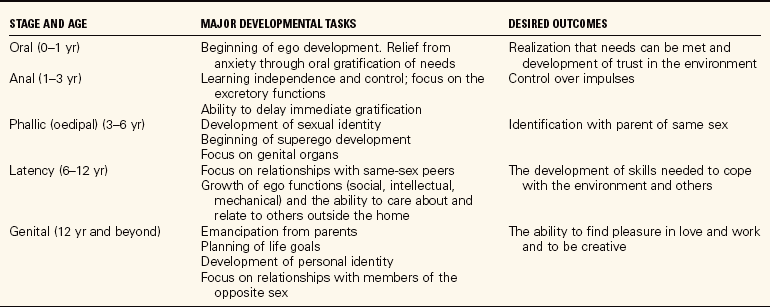

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) made contributions to the understanding of personality development. His psychoanalytic theory has three parts that include levels of awareness, components of the personality or mind, and psychosexual stages of development. The levels of awareness consist of the conscious, subconscious, and unconscious mind. The conscious mind is based in reality and what is sensed, perceived, and thought. The subconscious stores thoughts, feelings, and memories. These are easily brought into the conscious mind. The unconscious level is the part of the mind that is not accessible to one’s awareness. The unconscious mind stores memories that are usually painful and are stored here to prevent anxiety and stress. Freud stated that there are three functional components of the mind. The first is the id (body’s basic primitive urges). The id is concerned with satisfaction and pleasure. The pleasure principle, or libido, is the main force driving human behavior. At birth we are all id. The ego is considered the “executive of the mind.” It emerges in the fourth or fifth month of life. It is the problem solver and reality tester and develops with the person’s interaction with the environment and the demands of the id. In this way, the child learns to delay immediate satisfaction of needs. The superego is a further development of the ego and represents the moral component. This is the portion of the mind that judges, controls, and punishes. It dictates what is right and what is wrong and acts much as a conscience. These three components of the mind are constantly in conflict with each other according to Freud. Unrestrained id dominance can lead to a personality breakdown in which the person demonstrates childlike behavior persisting throughout adult life. A harsh superego can cause blocking of reasonable needs and drives and prevent full development of the personality in a healthy way. Table 11-1 shows Freud’s stages of psychosexual development.

Table 11-1

Freud’s Psychosexual Stages of Development

Adapted from Varcarolis, E.M., Carson, V.B., and Shoemaker, N.C. (2006). Foundations of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing: A Clinical Approach (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; and Polan, E., & Taylor D. (2007). Journey Across the Life Span (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis.

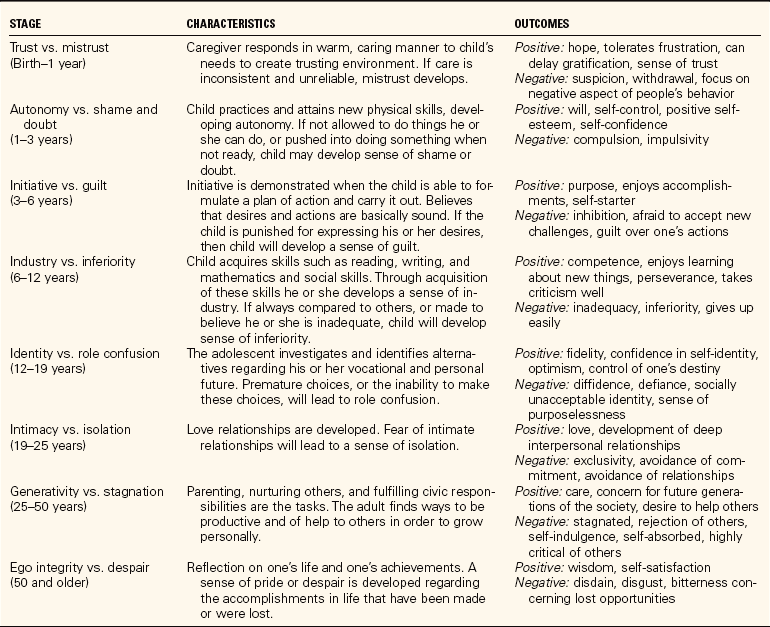

Erik Erikson (1902–1994) was a psychologist interested in the psychosocial aspect of development. He defined eight psychosocial stages. Each is identified by a psychosocial task that must be successfully mastered before the person can progress to the next stage. This growth aids development of a healthy ego. Erikson also believed that cultural, social, biologic, and environmental factors contribute to development. Table 11-2 summarizes this theory for children, adolescents, and adults. In the names of the stages, the first term listed is the desired psychosocial task to be mastered. The second term listed is the opposite, which Erikson considered a negative result.

Table 11-2

Psychosocial Development According to Erikson

From Bowden, V.R., Dickey, S.B., and Greenberg, C.S. (1998). Children and Their Families: The Continuum of Care (pp. 207–208). Philadelphia: Saunders.

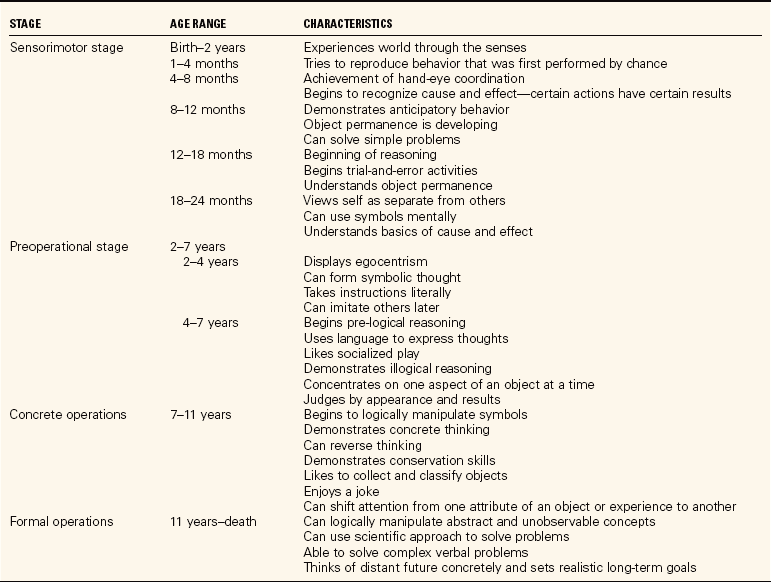

Jean Piaget (1896–1980) was a psychologist who developed a theory about how children learn. He said that all people are born with a need to adapt to the environment, and that the ability to use knowledge increases as a child grows. Piaget stressed two principles that allow this to happen: (1) organization’we try to make sense of our world; and (2) adaptation’we discover new information and adjust our thinking patterns. The four stages of Piaget’s theory are given in Table 11-3 on p. 141. As children develop, each stage helps them understand the world more thoroughly.

Table 11-3

Cognitive Development According to Piaget

From Bowden, V.R., Dickey, S.G., and Greenberg, C.S. (1998). Children and Their Families: The Continuum of Care (pp. 207–208). Philadelphia: Saunders.

Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–1987) developed a theory of moral development. He defined three levels of moral development occurring along with cognitive growth:

• Preconventional reasoning. Young children obey rules to avoid punishment. Moral values are not internalized. Most children are in this stage until about age 9.

• Conventional reasoning. At this level, children and adults conform to social standards to avoid disapproval or to avoid guilt. Decisions are based on understanding the social order, laws, justice, and duty. Children begin using conventional reasoning at around 11 and may remain in this stage throughout life.

• Postconventional reasoning. People at this level have internalized moral principles. They are law abiding and follow their conscience. Kohlberg believes that only a minority of adults operate at this level.

PRINCIPLES OF GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

Many factors influence growth and development. Heredity is a major factor, as is the environment. Some developmental psychologists have tried to determine which is more important. So far, there is not much agreement.

Family structure is also important. Are there two parents in the home? What parenting style is seen? What is the family’s socioeconomic situation? Some people think that ordinal position (birth order) also plays a part. Even gender (male or female) can influence how a child is raised.

Even with all the variables that can affect growth and development, some basic principles exist:

• Growth occurs in orderly and predictable ways. Patterns and stages can be anticipated.

• The rate of growth and development is individual. Even siblings (brothers and sisters) develop at different rates.

• Development is lifelong. People continue to change throughout life. Physical growth is seen in childhood, but normal changes continue.

• Development is multidimensional. It involves many processes, including physical, cognitive, and psychosocial aspects.

• Development is continual, but may occur at different rates. There may be times when development seems static.

PRENATAL DEVELOPMENT

Prenatal development begins at the time of conception, when the mother’s ovum is fertilized by the father’s sperm and a new and unique cell is formed. This cell, the zygote (fertilized egg), will, under healthy circumstances, become a baby.

Among the many influences on prenatal development is genetics. Genes (segments of DNA that carry the blueprints of development) pass from parents to child through the sperm and the ovum. The nucleus of the individual cells contains 23 unpaired chromosomes. The chromosomes are filled with tightly coiled strands of DNA. The zygote contains 23 chromosomes from the father and 23 chromosomes from the mother, thus once joined the human cells contain 46 chromosomes. These 46 chromosomes become a unique combination that will almost certainly never occur again. That is why each of us is different from everyone else.

EVENTS IN PRENATAL DEVELOPMENT

There are three stages of prenatal development: germinal (initial), embryonic (early formation), and fetal (late). An overview of prenatal development is provided here.

Pregnancy is divided into three trimesters (periods of 3 months). A full-term pregnancy lasts 40 weeks. Birth within 2 weeks on either side of the estimated date is considered normal. If the baby is delivered earlier than 38 weeks’ gestation, it is called premature. Premature babies can survive if their systems are mature enough to support life and if the delivery occurs in a safe place. When a pregnancy ends before the fetus is viable (able to survive outside of the womb), it is called an abortion. A naturally occurring abortion is often called a miscarriage.

MATERNAL INFLUENCES

The single most important factor in maintaining a healthy pregnancy is early and regular prenatal health care. Visits with health professionals help expectant mothers understand what is happening and how they can contribute to healthy fetal growth. This care also allows the health professional to detect signs of potential problems and intervene before the problems become serious. A healthy outcome for both mother and child is always the goal. Lack of prenatal care is a serious problem for some women. This can occur because of economics, fear, ignorance, lack of access, or other reasons. Healthy People 2010’s objective of “increase the proportion of persons appropriately counseled about health behaviors,” and the goal of increasing access to health care for all people in the United States, make it imperative to refer pregnant women to an agency that can provide prenatal care regardless of their economic position (Health Promotion Points 11-1).

A second influence in prenatal development is the mother’s health. Women with a chronic illness who are pregnant are usually considered high risk. This especially includes women with diabetes or rheumatic heart disease. Contracting a communicable disease during pregnancy also presents a risk to fetal health. German measles (rubella) is one communicable disease known to cause harm to a fetus.

Another influence can be the mother’s age. Pregnancy before the mother reaches her adult growth, at about age 16, can be a high-risk situation. At the other extreme, a woman experiencing her first pregnancy after age 35 is considered high risk. Any pregnancy when the mother is over 40 is also high risk.

A fourth influence is the mother’s nutritional state. Women need to be well nourished before pregnancy begins as well as throughout the pregnancy. The mother’s nutrition is vital for healthy fetal development. A woman who begins a pregnancy at a healthy weight should gain approximately 30 pounds; less than that endangers fetal growth. Excessive weight gain can complicate the delivery and can also make it hard for her to lose weight later. A Healthy People 2010 objective is to “increase the proportion of mothers who achieve a recommended weight gain during their pregnancies.”

Emotional stresses may also influence the pregnancy. Women who experience severe emotional stresses may put the fetus at risk. This is because stress affects the physiology of blood flow and may restrict blood to the placenta. Prolonged stress interferes with adequate nutrition and oxygen to the fetus.

The sixth influence is the use of chemicals. Chemicals known to interfere in some way with fetal development include alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, some medications, and street drugs. As scientists study babies with problems, it is becoming apparent that even casual use of any of these chemicals may be risky. Another Healthy People 2010 objective is to “increase abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes, and illicit drugs among pregnant women.” This will help in the achievement of another goal, to “reduce the occurrence of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS).”

INFANTS

For the first month of life, the baby is a neonate (newborn). This month is a period of adjustment for the infant and the new parents. Infancy extends through the first 18 months (Health Promotion Points 11-2).

APPEARANCE AND CAPABILITIES OF NEWBORNS

At birth, the skin and scalp are often covered with vernix caseosa (a cheesy, waxy substance that protects the skin in fetal life). This wears off in a day or two. Babies’ heads appear large in comparison to their bodies, and may be temporarily misshapen. They move their arms and legs aimlessly; the hands and feet may appear slightly cyanotic for a while. Newborns should cry spontaneously after birth. They will usually be quiet when wrapped tightly in a blanket and held as this provides a feeling of security.

A newborn may appear helpless but really has many capabilities. Reflexes (instinctive protective actions) present at birth include blinking, yawning, grasping, stepping, hiccoughing, sucking, and swallowing. The Moro reflex (startle response) can be elicited by making a loud noise near the baby, who will react by arching his or her back and assuming a typical posture with flexion and adduction of the extremities and fingers fanned initially.

Newborns can also express themselves by crying; it usually does not take long for new parents to know the meaning of the different cries they make. Newborns also watch everything and everyone. Their response to people and surroundings is the way they communicate.

A typical newborn sleeps from 16 to 20 hours per day. This time is important for growth and development. Eating and being loved and cared for usually fill the waking hours. Wakefulness increases as they get older. By 1 year of age, most infants need only a morning and afternoon nap.

NUTRITION

Healthy newborns can manage without calories for the first 12 to 24 hours, but usually are breast or bottle fed sooner. After that, they need to have caloric intake to survive. Most pediatricians recommend breast-feeding; breast milk is perfectly designed for the newborn’s digestive system. It also provides the newborn with protective antibodies for the first few months. There is a Healthy People 2010 objective directed at increasing the number of women who breast-feed their infants.

Women who choose to use infant formula, either initially or later, should know that it closely resembles human milk. The physician will recommend the type of formula. Cow’s milk is not advised for babies until 11 to 12 months of age because of possible allergicreactions.

The stomach of newborns holds only an ounce or two at first; that is why they need to eat often. Babies grow rapidly; by 1 month they are eating larger amounts. Feeding time should provide emotional closeness. Infants should be held and talked to while being fed.

For the first 6 months, babies need only breast milk or infant formula. The first solids are usually baby cereals, strained vegetables, and strained fruits. It is best to add new foods slowly in order to see how well the baby tolerates them. Older infants enjoy finger foods. Most babies can eat table food by 1 year of age. They should not be given pieces of sausage, peanuts, or hard candies that could be aspirated.

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT

The average white newborn weighs 7 to 7½ pounds and is 20 to 21 inches long. Dark-skinned babies may be a little smaller at birth. Newborns between 5½ and 11 pounds are considered equally healthy. There are two categories of low-birth-weight babies. The first is preterm babies who are born before 37 weeks of gestation and weigh less than 5 pounds. The second category is small-for-dates babies. These infants are born at term but weigh less than 90% of what they should weigh.

All babies should double their birth weight at 5 to 6 months, and triple it by 1 year. They should also grow 11 to 12 inches in the first year (Health Promotion Points 11-3).

The newborn’s eyes are dark blue or gray. The permanent eye color will develop by 9 to 11 months. Newborns can see light and darkness, and seem to prefer bright colors. Their vision is focused best at 8 to 15 inches from their eyes. Visual acuity increases in harmony with their growing awareness of their surroundings.

Newborns can hear well and are afraid of loud noises. Infants prefer their mother’s voice to that of other women, and they often recognize voices of other family members.

The sense of touch is not well differentiated at birth, but babies need to be touched and held. They can feel pain, although it is more generalized than specific for the first few months.

The baby’s first teeth, the bottom incisors, usually appear at 5 to 11 months. By 12 months, many babies have six to eight temporary teeth.

The brain grows rapidly in infancy and early childhood. Neurons present at birth are not fully developed. As the baby grows, the neurons continue to extend, grow, and make connections. A newborn’s brain weighs 25% of an adult’s brain; this increases to 66% in the first year alone. By age 2, the brain weighs 80% of an adult’s brain. Infants and young children need a healthy diet, including fats, for brain growth to occur. They also need stimulation for neuron connections to form.

MOTOR DEVELOPMENT

Motor development occurs in a typical pattern. The pattern is consistent, though the rate may vary from one child to another.

Cephalocaudal (proceeding from head to tail) development means that babies can lift their head before they can lift their chest. They can sit before they can stand. Development also proceeds from the center of the body toward the outside. They control their shoulders before they control their arms and fingers. Large muscles develop coordination before smaller ones. For example, they can walk before they can draw.

Milestones in motor development are shown in Box 11-1. Parents may need reassurance if one child develops more slowly than another. Children perform motor skills only when they are developmentally ready.

Several environmental factors influence a child’s motor development. Children need good nutrition, health care, emotional support, and the opportunity to practice motor skills. Deprivation of any of these factors may cause developmental delay. Safety for the helpless infant is a primary concern (Safety Alert 11-1).

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

According to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, babies actively construct their own cognitive world. They organize experiences and observations and then make adaptations in thinking when new situations occur. Newborns display this process by eagerly sucking on everything that comes near their mouth. Later, they learn that some things, such as a nipple or thumb, are suitable for sucking. These items provide satisfaction, either nutritionally or emotionally. Sucking on a blanket or a toy does not provide the same satisfaction.

The first cognitive stage is sensorimotor. This begins with babies experiencing things about themselves’becoming aware of the sensations of their body, discovering their toes, etc. Then babies move on to learn about other people and objects in their world.

By the time babies are about 8 months old, they realize that an object still exists even when they cannot see it. This is called object permanence. It is demonstrated when an infant is shown an object that is then hidden, and the baby looks for it.

Authorities debate whether an infant’s intelligence can be accurately measured. One measure that is sometimes used is language development. Most infants begin babbling at 3 to 6 months, the cooing, gurgling stage. Babies learn language by listening to people around them and imitating the sounds they hear. Parents who talk to their babies and spend time with them stimulate language development. Babies often say their first word at 11 to 13 months and begin using two-word sentences at 18 to 24 months. The same sequence exists all over the world.

An infant’s efforts at discovery are dependent on the assistance and guidance of the adults in his or her life. Caregivers can stimulate cognitive development by spending time with the baby, talking, singing, playing, and loving. Many kinds of experiences should be provided. Babies thrive on receiving lots of attention and being part of family activities (Figure 11-1).

PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Infants learn to interact with other people by experience with their caregivers. Bonding (sense of attachment between two people) occurs with one or two primary caregivers first, usually the mother and/or father. The infant’s need for stimulation and love grows during the first 3 months. Physical contact, caring, and familiarity are important aspects in bonding. By 5 or 6 months, the baby is ready to include other people in relationships.

Bonding gives babies the security they need to develop the sense of trust. Erikson believed that infants learn to trust others when they receive warm, consistent care. To develop trust, infants need to feel comfortable and secure and believe that the caregiver will always meet their needs. Infants who have a sense of trust will have confidence to explore new situations and can usually handle short separations from parents. This will help them develop relationships with other people throughout their lives.

A healthy baby recognizes family members and shows insecurity with strangers by 6 to 7 months of age. Studies show that infants with a secure attachment to another human are happier and less frustrated at 2 years of age than infants with a less secure attachment.

YOUNG CHILDREN

Young children are defined as those between 18 months and 6 years of age. This group is sometimes divided into toddlers (1 to 3 years) and preschoolers (4 to 5 years). Many developmental milestones occur in these years.

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT

The rate of growth in early childhood is slower than in infancy. Young children lose their baby fat and appear slimmer as their trunk lengthens. Most young children grow 2 to 3 inches in height and gain 4 to 6 pounds each year. Boys are slightly larger than girls during this period. The size of muscles and bones increases, which can lead to greater strength. Heart and lungs become more efficient, and the child’s immunity improves.

Heredity and the environment have been shown to influence this physical development. The primary environmental influence is nutrition. Young children need 1400 to 1800 calories per day. Sometimes when the child doesn’t eat much, it concerns parents; at this age some children are fussy about what they will eat. Children over 2 years of age need less fat and sugar in their diets than they are usually fed.

Vision improves during the early childhood years. By 2 years, visiual acuity is usually 20/40. Vision may be checked during a preschool physical exam in the physician’s office, but this is usually done during the kindergarten physical examination or at the beginning of the first grade (Health Promotion Points 11-4). Visual screening is often a function of the school nurse.

During early childhood new teeth continue to erupt. A full set of deciduous teeth numbers 24 and should be present by age 3. Supervised toothbrushing and flossing should begin as soon as a child has teeth. The first dental visit may be made when a child is 2 to 3 years old.

A growth chart can monitor the child’s physical growth. Height and weight are plotted on the graph and compared with those of the average child. Most children will fall within the guidelines of the curve. A child who falls below the 5th percentile or above the 95th percentile may need further evaluation as something physical may be wrong. It is important to monitor the child’s growth so that any problems can be treated before they become serious. Growth progress should be steady.

MOTOR DEVELOPMENT

Motor development proceeds as growth occurs. Neuromuscular maturation is needed for motor skills to develop. A milestone of this age-group is toilet training, the age for which varies from culture to culture. Most children are physiologically ready to be bowel trained between 1½ and 2 years, but successful toilet training also depends on psychological readiness. Daytime bladder control usually occurs later than bowel control; nighttime bladder control occurs later than that.

Young children also learn to feed themselves, dress themselves, and become independent in many activities. Improving neuromuscular skills leads to better coordination. For example, at age 2, children usually hold someone’s hand to go up a stairway and take only one step at a time. At 3, they can climb stairs using alternate steps, though they may still need to hold on. By age 4, they can climb a stairway alone. At 5, they will run upstairs without even thinking about it.

A commonly used assessment tool is the Denver Developmental Screening Test, also known as the Denver II. It is a simple and rapid way to assess developmental maturity of young children before they start school. The test giver spends time with the child to observe gross and fine motor skills, language, and social ability. Some gross motor skills measured include walking, jumping, using a tricycle, throwing and catching a ball, hopping on one foot, and balancing on one foot. Fine motor skills include stacking a pile of blocks, drawing people, and drawing houses.

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

Expanding neuron connections result in increasing learning and thinking skills. Piaget called the ages of 2 to 7 years the stage of preoperational thought, defined as learning how to organize thoughts. This stage is subdivided into symbolic function and intuitive thought.

In the symbolic function substage, children can think about objects, people, and events in their absence by using mental symbols of them. Watch a child draw a picture or play a game of pretend. The child can think about objects even though they are not currently present.

There are some interesting normal occurrences during these years. Children have vivid imaginations, and many cannot easily distinguish between reality and fantasy. Cartoon characters are real to the young child, and stuffed toys are alive. Young children engage in magical thinking. Because they do not understand cause and effect, they may think that events occur magically.

Another phenomenon is the child’s egocentric (I am the center of the world) belief. Young children believe that they are the most important person in the world. They think that their desires should be fulfilled on demand. They also believe that their thoughts influence events, and they cannot grasp another person’s viewpoint.

In the intuitive thought substage, thinking abilities expand, thoughts are better organized, and early problem solving occurs. Abstractions such as time and numbers often remain hazy.

One highlight in young children’s cognitive development is their curiosity. This often surpasses their caution, making safety a concern. The home and play environment should be free of lead contamination to protect against lead poisoning. Children lack the experience and knowledge to understand possible dangers. Childproofing a home (keeping cleaning supplies, medicines, and other potential hazards out of reach) is essential. Health Promotion Points 11-5 presents safety considerations. Children at this age need instruction about dangers: cars, crossing streets, strangers, acceptable ways to touch and be touched. Parents and other caregivers are primary safety teachers by example and concern.

Attention spans begin to lengthen during these years. A 5-year-old can sit still much longer for a story than can his or her 2-year-old sister. This makes conversations interesting. A child’s memory also improves.

Language develops rapidly during childhood. Most 6-year-olds know 8000 to 14,000 words. Sentence length usually increases proportionately to age. The speed with which a child learns to talk is not necessarily indicative of intelligence. Girls often begin to talk sooner than boys, and firstborn children may talk at a younger age than their siblings.

Young children have lively imaginations. Some develop an imaginary friend who accompanies them everywhere. This friend can conveniently be blamed for minor problems, too. The playmate usually disappears when the child is 5 or 6. Pretend play is also imaginative. Pretending is important between 3 and 8 years, as the child experiments with various roles.

PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Erikson’s second stage of development occurs from 18 months to 3 years. Autonomy (being independent) develops as children learn to feed themselves and to do other things without help. Children are also more verbal, and can say “no,” often with great conviction.

Caregivers who are impatient and do everything for the child may cause feelings of shame and doubt to develop. If parents are overprotective and critical, for example, children may be ashamed of themselves and doubt their ability to accomplish things.

Erikson’s stage for ages 3 to 6 is called initiative (willingness to try). Young children are energetic, eager, and curious. They know no fear and want to explore the world. They are also beginning to develop a conscience and to learn what is right and wrong. Will the child be successful in this stage of initiative, or will he or she be plagued by guilt, by not doing the right thing? Parents can aid children through this stage by giving them freedom to explore within safe limits, by encouraging their questions and ideas, by supporting successes, and by helping the preschooler develop self-esteem.

Young children do need to learn discipline. Many parents find that enforcing time-out (quiet time alone without toys) is often effective. It is recommended that 1 minute be used for each year of age. This must occur immediately after the offense or the child will not relate the behavior to the punishment.

Children learn gender roles (behaviors and attitudes a culture expects and approves for males or females) during this stage. They observe the behaviors expected of boys and girls and how they differ. By 3, children know their own gender, and by 6 they can usually identify another person’s gender by watching appearance and behavior. Some psychologists believe that sex hormones, even in young children, strongly influence a child’s behavior. Others believe that the gender roles children adopt are more influenced by their environment. Parents and other adults provide strong influences in the child’s gender role adaptation. This occurs through their examples, the toys they provide, and the way they treat children.

A new sibling often arrives in a family during an older child’s early years. There is a natural rivalry when children think they must compete for their parents’ attention. Parents should make every effort to give adequate attention to each child and to treat each as an individual. A young child can be somewhat prepared for the arrival of a new baby through talking with the parents, reading story books about babies, and participating in special sibling classes. Older children will continue to need much reassurance that they are still loved.

Morals (values of right and wrong) are developed during young childhood. Young children are developing a conscience. They start to understand other people’s feelings, which is the beginning of empathy.

The importance of peers (others of similar age and background) increases as children get older. The young child is first influenced in the home by parents and other family members. By age 3, the child needs exposure to other children. It is important for parents to realize that children naturally begin to seek friendships and experiences outside the home by the time they are 6.

Play contributes to cognitive and psychosocial development. Children’s play helps them learn and understand the world around them. Several types of play are shown in Box 11-2. Play should be spontaneous and voluntary. Most preschoolers prefer playing with same-gender children. Children also enjoy playing with adults.

DAY CARE AND EARLY EDUCATION

Many young children in the United States are cared for by adults other than their parents some of the time. According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census (2007), over 10 million American mothers with young children are employed outside of their homes. Child care may be provided in a home setting or in a group setting. Topics considered when choosing appropriate care are the approach to discipline, general child-rearing practices and beliefs, provision of appropriate activities for the child, attention to safety and health, and a nurturing atmosphere. Parents should carefully check a day care situation before entrusting their child to it.

Group settings provide stimulation for the child in areas that may not be available in the home setting. The day care center or preschool also provides an opportunity for the child to adjust to leaving home for a period of time before the beginning of regular school years (Figure 11-2). The child also learns socialization skills. The government provides funds for Head Start, a preschool program for children in lower income families. The child’s behavior should be monitored for signs of stress when in a child care setting because some children are maturationally too young to adapt.

MIDDLE AND OLDER CHILDREN

Middle and older children are those from age 7 to 11. Children move through elementary school, join in group activities, and become more grown up. They are filled with energy and enthusiasm. They begin to express their own ideas with confidence and are interesting people.

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT

Growth continues to be slow and steady. Children grow an average of 2 to 3 inches in height, and gain 3 to 5 pounds in weight each year. There may be periods of several months without apparent growth, followed by periods of rapid growth. Change is most noticeable in leg length, while the body trunk becomes slimmer. By age 11, some children begin to show signs of prepuberty (beginning sexual development).

Children can run, hit a baseball, swim, and perform many other physical activities. This demonstrates increasing coordination skills.

One health concern for this age-group includes regular dental care, because this is the time when permanent teeth are erupting. Children in this age range often need orthodontic treatment. Immunization boosters are given when the child begins school (Figure 11-3). Vision screening exams are often done for the first time when a child begins formal schooling. Getting adequate sleep is another concern; a child at this age is often energetic and busy. Parents should monitor schedules so that children do not become overly busy. Education about healthy nutrition is also important because habits formed now will influence future diet and health. There has been a large increase in obesity among children related to fast food, calorie-laden juices and sodas, and large servings. Young people who are properly nourished throughout their childhood tend to be healthier as adults. There are Healthy People 2010 objectives directed at increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables, maintaining weight within recommended limits, increasing calcium consumption to promote healthy bones, and diminishing the amount of unhealthy snacks eaten by children.

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

Piaget called this stage of cognitive development concrete operational thought. Mental operations are mental activities that can be reversed. Children think in concrete ways about real things, and they draw conclusions based on what they see and know. Ideas are organized and fixed. This demonstrates early problem-solving skills. Children think in black and white; they may have trouble accepting “maybe” situations. They are able to classify things and identify relationships. Children often enjoy collecting things and can spend hours organizing their stamps, rocks, or baseball cards.

Cognition is also apparent in intelligence (a combination of verbal ability, reasoning, memory, imagination, and judgment). No one knows whether heredity or environment is the greater influence on intelligence; certainly both are important. Most children are given some type of intelligence test during their elementary school experience. Scores are given as an intelligence quotient (IQ). IQ tests often emphasize language and mathematical skills. The average person has an IQ of 110, with ranges of 80 to 120 considered normal. Children and their parents need to understand that IQ measurements are only estimates of academic abilities and are not measures of a person’s worth or potential for academic success.

Other tests may be used to measure aspects of intelligence. Most people probably possess many kinds of intelligence and should be encouraged to discover and nurture their individual strengths and talents. Kinds of intelligence and talent include linguistic, mathematic, spatial, musical, bodily kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal.

It is often during the early school years that children with learning problems are identified. Special programs can be helpful for children whose mental development is delayed. Children with an IQ below 70 and who have problems adapting to everyday life are often considered to have special learning needs. This may be an inherited, organic problem, or it may be a result of illness, malnutrition, or lack of mental stimulation.

Numerous types of learning disabilities can be identified through testing and screening procedures. Many children can be aided to develop study habits and alternative learning methods in order to reach their full potential in the education experience.

The other extreme in the range of intelligence is the gifted child, who has an IQ well above the average (140+) and/or possesses a superior talent. Gifted children also need individualized programs. Traditional educational systems may not provide adequate challenge.

Studies of successful adults have led to the concept of emotional intelligence. This consists of six components (Box 11-3). Parents need to model healthy emotional skills. Adults should help children learn to talk about feelings. This requires taking children’s feelings seriously and helping them find healthy ways to cope with their feelings.

PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Children in the middle years are continuing to develop their self-concept (the way one views oneself). Children need to feel that they are valuable and important. A comfortable relationship with parents and other adults is vital for development of a healthy self-concept.

They also begin developing social competence (being comfortable in public, able to get along). They learn to cope with minor stressors. They can see that their behavior may influence others, and they become aware of how they appear to other people.

Erikson called the middle to late childhood psychosocial development stage industry vs. inferiority. Children are energetic and capable; they want to accomplish things. They are interested in how things are made and work. Parents and teachers can aid the child through this stage by encouraging ideas, complimenting accomplishments, and helping a little at times. Every child can be complimented on some accomplishment; positive reinforcement helps them thrive. Children need support in facing their problems; they learn that problems can be managed.

The importance of peers increases as children grow. Middle and older children often organize clubs or teams. Belonging to a group builds self-esteem. Group activities are usually with same-gender children. Friendships are vital. Most children have one best friend with whom they share secrets and special times (Box 11-4).

PARENTING

Parents of middle and older children must adjust their expectations and degree of control. It is natural for children to begin spending more time with friends and less with family. Yet parents should remain interested in and involved with their children.

Children at this age can be given more responsibility, including household chores. They need to have opportunities to make decisions. Parents may need guidance in gradually decreasing the amount of supervision.

Some children must spend time alone before and/or after school because of their parents’ schedules. The decision of when this can be permitted will depend on the length of time involved, the child’s age and degree of responsibility, and the living situation. Most children under 11 should not be left alone for more than an hour. Each family makes this decision, when necessary, on its own.

Middle and older children can no longer be disciplined by a time-out. Denial of privileges is often a better tool. Because of the importance of friends and social events, restricting those activities is often effective.

Three parenting styles have been identified by psychologists: permissive, authoritarian, and authoritative (Table 11-4). The authoritative parent is often considered the ideal.

Table 11-4

| STYLE | PARENT BEHAVIORS | CHILD MAY BECOME |

| Authoritative | Firm, in control, have rules; warm, loving, encouraging | Self-reliant, responsible, socially competent |

| Authoritarian | Firm, in control, have rules; emotionally distant | Socially anxious |

| Permissive | Rules, if present, are flexible; may be emotionally warm or not | Impulsive, aggressive, lacking self-control |

The reality is that most parents do not use only one style. Two parents in the family may use different styles. Styles may also change with additional children in the family and as the parents mature.

CHILD ABUSE

Abuse of children by parents or others can occur at any age. There are many types of abuse: physical, sexual, emotional, neglect, and verbal. Each is damaging to the child’s development.

Psychologists have determined that many abusers were themselves victims of abuse and have poor self-concepts. They may not know how to maintain a healthy relationship. This does not excuse their behavior but serves as a warning that the cycle may continue unless someone intervenes. Health care workers are required, in many states, to report signs of abuse to social agencies or law enforcement authorities (see Chapter 3).

ADOLESCENTS

The adolescent years begin at age 12 and continue through the teens, to age 18. The actual years are less significant than the experiences and development that occur. Because development is different for each individual, some 12-year-olds appear more physically mature than their peers. Another person may be 18 or even a few years older, yet still behave in adolescent ways at times.

Young children often talk about growing up, and older children may express eagerness to become teenagers. Many changes occur and this can be a very confusing time in the young person’s life.

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT

Adolescents experience major physical changes with the onset of puberty (sexual maturation) which occurs gradually over several years. The normal development of the reproductive system depends on the health of the entire body, especially the endocrine system. Genetics and nutrition are the primary influences on the age at which puberty occurs. (See “Overview of Structure and Function” on p. 138 for the physical changes in puberty.)

Puberty also stimulates a growth spurt in adolescents and growth periods may lead to fatigue. Both boys and girls usually continue to gain weight while they are growing in height. Girls usually reach their adult stature by the time they are 18; boys may continue to grow taller well into their 20s.

The difference in the rate of physical development is often a concern to adolescents. Two friends may be the same age, but one may be more developed than the other. Because girls mature at a younger age, they are often taller than boys their age. Adolescents seldom think they compare favorably to their peers. They are preoccupied with their bodies and pay a lot of attention to their appearance. Safety is a concern as adolescents expand their social networks and activities (Safety Alert 11-2).

SEXUALITY

Because the sex hormones also influence thoughts and desires, it is natural that adolescents may seek sexual activity. The media and entertainment industries also encourage sexual thoughts. In 2002, the National Center for Health Statistics reported that 47% of girls and 46% of boys had experienced intercourse by age 18. Reports indicate sexual activity is occurring at younger ages. Although the body is capable of intercourse in adolescence, many young people are not prepared for the emotional aspects of sexual activity (Health Promotion Points 11-6).

Studies show that adolescents actually know much less about sexuality than they pretend or think they know. More sex education is direly needed to prevent early pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection. Parents remain the best teachers, but often they do not take on that role. Schools are often expected to teach about sex. Adolescents need factual information about physical changes and sexual development. Even when adolescents have been taught the basic facts about sexual behavior, they often do not think that such facts will apply to their own circumstances. The United States has a high rate of adolescent pregnancy. Parents, churches, and other organizations can help adolescents develop strategies for saying “no” to sexual activity.

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

Adolescents are learning to think in creative, abstract, logical, and idealistic ways. They begin to examine their own thoughts and try to analyze the thoughts of others. Piaget labeled this stage formal operations. Beginning between ages 11 and 14, thought becomes more abstract; the adolescent can think about ideas. Some enjoy becoming quite philosophical.

Young people may analyze how they want to be, how their parents should be, and how the world should be in the future. Sometimes this idealism becomes frustrating for them as they encounter reality. This growth in brainpower is seen in increasing communication skills as they organize their thoughts in logical ways.

Adolescents also become more aware of other people and of what others think about them. They want to fit into society. They also become egocentric again. Young people think that others are as interested in them as they are. They may indulge in attention-seeking behavior.

Another part of egocentrism is believing that their own experiences are unique. They may not realize that other people have faced disappointments and problems, too. Adolescents may also believe that they are immortal. They cannot imagine that anything bad would happen to them, so they may avoid using contraception and lack concern about drinking and driving.

The role of schools in the cognitive development of adolescents remains significant. Schools that address the individual learning needs of students can aid young people in their search for meaning and identity. Teachers who understand adolescents can help them figure out the world, as well as stimulate their intellectual growth. School is also important for the social activity it provides.

PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

The psychosocial development of adolescents can be turbulent. Emotions may be erratic when hormones are newly released. The young person has to learn how to handle those emotions and how to get along with other people.

Change continues to occur in the relationships between adolescents and their families. Teens seek to be autonomous and to be free of parental control. Yet many adolescents also yearn to have rules and to know that parents care about and for them. Parents should gradually allow young people to make more of their own decisions; both parents and teens also have to learn to live with the consequences.

Time spent as a family unit often lessens when the child becomes an adolescent. It is natural for the teen to want to spend more time with peers. Parents should allow more freedom for peer interaction, but should monitor the teen’s activities and friends. Parents who try to hold the teen too closely may discover they cause estrangement from their teen. Many people admit only later in their lives that family relationships are important during adolescence.

Serious conflict between parents and teens is most common, when it occurs, during early adolescence. This corresponds to the time of major hormonal shifts and helps explain why the junior high or middle school years may be difficult. When conflict has existed, it usually becomes less acute as the adolescent matures. By age 17 or 18, relationships with parents often become smoother. The daily negotiations and minor conflicts that occur are natural results of development and help adolescents find their own identity.

Adolescents continue to learn about the world and other people during time spent with their peers. In early adolescence, there is a strong need for young people to conform to a peer group. Young people often want to dress alike, behave alike, and do the same things that their group does.

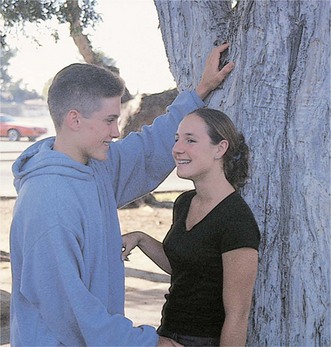

Dating is an important adolescent experience that also helps young people discover their individual identity. Dating serves many other purposes such as recreation, status, and achievement. Most adolescents become interested in the opposite sex early in puberty (Figure 11-4). The interest grows as they mature. Young people’s groups include both boys and girls, gradually evolving into group-dating events.

Erikson’s stage for adolescence is identity vs. role confusion. The adolescent struggles with questions: Who am I? What am I about? What will I do with my life? The teen who is successful in coping with these questions develops an acceptable sense of self. The teen who is not successful may remain confused, withdraw from society, or passively follow the crowd. Some teens conquer this challenge during adolescence, whereas others struggle longer. A healthy identity is open to change as time goes on.

Some adolescents experiment with a variety of roles in society. This may cause conflicts with parents, as teens explore alternative lifestyles and/or value systems. The types of jobs that adolescents may try can also aid them in discovering who they are. Contemporary theorists agree that the resolution of this identity search may extend into adulthood. This is especially true with young people who continue their education after high school.

Parents of adolescents can aid them in successful psychosocial development by supporting their decisions, acknowledging the struggles that occur, and respecting them as they mature. Parents and teens who have had open communication and mutual respect during their earlier years should navigate this challenging time with less trouble than those whose prior relationship was shaky.

TASKS OF ADOLESCENCE

Discovering their identity is a primary psychosocial task for adolescents. They also begin making decisions that will affect the rest of their lives. One of these is choosing a vocation. Although teens are seldom expected to decide on a lifetime vocation, they should have some ideas about the kind of work they would enjoy.

Ideology (a belief or value system) should be fairly well established by the end of adolescence. A moral code begins to be incorporated. One’s sexual orientation (sexual preference) should also be set. Approximately 8% of adolescents have had a sexual encounter with a person of the same sex, but that does not mean they are homosexual. Studies report that about 5% of the population is homosexual (Behrman et al., 2004). All need to accept and understand their own preference.

Some theorists claim that mate selection is also part of adolescent development. In the United States, many young people prefer to postpone marriage until later in their lives.

CONCERNS IN ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT

When an adolescent becomes pregnant, she needs assistance in discussing options. It is difficult to decide whether to place the child up for adoption, to keep the child and remain single, to keep the child and marry, or to abort the pregnancy. Often the father contributes little to the financial and emotional support of the infant of an adolescent mother. Sometimes, adolescents who are unmarried keep the baby, and the grandparents end up with the responsibility of raising the child. This is becoming a significant burden for the older generation. Often the adolescent mother does not continue her education and then has trouble becoming a self-sufficient adult.

The U.S. Bureau of the Census (2007) reported that, in the year 2004, 41,100 girls between ages 15 and 19 delivered babies. This was a 1% decrease from the previous year. It is predicted that 18% of 15-year-olds will have a baby before age 20, and 80% of teens who have a baby will live at the poverty level for 10 years or more (National Coalition for the Protection of Children & Families). Adolescent pregnancy is a high-risk pregnancy, because the young expectant mother is still physically growing. Younger mothers more often have premature babies with low birth weight. Pregnant adolescents must be guided toward early prenatal care, parenting classes, and psychosocial counseling. The social problems generated by adolescent pregnancy are significant as many become single mothers and end up needing welfare for themselves and their child.

Employment

Many adolescents seek part-time work. Most authorities agree that there are positive and negative aspects of adolescent employment. First jobs can be valuable in teaching work ethics and money management. Some adolescents need to work to help supplement the family income. Others want to pay for special clothes or a car. Depending on the number of hours worked, school grades may suffer. Sleep may suffer as well, just when the body needs more sleep for growing, and family interactions also may be affected.

Chemical Abuse

Alcohol is the most common drug used, followed by marijuana and amphetamines. Young people do not achieve positive development in cognitive and psychosocial aspects when they abuse chemicals. Alcohol use contributes to risky sexual behavior and is often a factor in teen pregnancy. Depression may become a problem as the teen isolates from usual activities and school as a result of the chemical abuse.

Eating Disorders

Adolescents who are obsessed with body image (particularly females) may develop severe eating disorders. Anorexia nervosa is a disorder in which food intake is severely limited, large amounts of water are consumed, and strenuous exercise may be used to control body weight. The body becomes emaciated and sexual development is delayed. Anorexia nervosa may result in death if left untreated. Bulimia is characterized by binge eating followed by inducing vomiting or using laxatives to eliminate the foods from the body. Bulimia may accompany anorexia nervosa or may be a disorder by itself. Bulimic individuals tend to maintain a more normal weight. Both disorders are psychological illnesses that present as physical symptoms, and both can have long-term negative physical effects. Growing up in a dysfunctional family may contribute to the development of eating disorders.

Depression

Mental health disorders are sometimes undiagnosed in adolescence. Untreated depression may be the cause of attempted or successful suicide. At other times, depression seems to be a sudden reaction to a change in one’s life (Safety Alert 11-3).

NCLEX-PN® EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Choose the best answer(s) for each question.

1. According to Freud’s theory, the part of the mind that acts as one’s conscience is the ____________________________. (Fill in the blank.)

2. Milestones in infant development indicate that infants begin using two-word sentences at:

3. When considering the principles of growth and development, remember that:

1. although development occurs in an orderly sequence, the rate may vary between individuals.

2. development occurs evenly, with periods of no growth occurring every third year.

3. all children should grow at the same rate; all 4-year-olds should weigh within 11 pounds of each other.

4. The purpose of play during infancy is to:

5. According to Erikson, a sense of initiative is best explained as:

6. In Piaget’s theory, using language to express thoughts occurs at age __________________________. (Fill in the blank.)

7. Bonding is necessary for the child to develop:

8. Parents of children ages 3 to 6 may need guidance in:

1. making the child feel secure when a newborn arrives.

2. helping the child cope with peers.

9. A parent who insists that the child stay in his room for the full 11-minute time-out and then smiles and hugs the child when the time is up is showing a parenting style that is:

10. Growth and development should be monitored regularly for every child in order to:

1. provide statistics needed for proper research.

2. detect abnormal growth patterns so that early care and treatment of problems can begin.

3. provide data to establish norms for growth and development at various ages.

11. An effective discipline measure for adolescents is:

1. restricting social activities for a limited time.

2. grounding them to the house for several weeks.

12. Egocentrism as a characteristic of adolescence is displayed by the teen feeling that:

1. parents only have to be obeyed when it is convenient.

2. a big disappointment like what just happened has never happened to anyone else in this way.

3. his peers are much smarter than his parents.

4. he can visualize a world in the future that will be far better than the world now.

13. The adolescent who is thinking in logical and abstract ways as he completes a term paper shows:

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES ? Read each clinical scenario and discuss the questions with your classmates.

A single mother whose 7-year-old daughter has a bad cold brings the child to the clinic where you are working. The child is smaller than average. As you interview them you learn that because of the mother’s work schedule, the girl is home alone every school morning for 2 hours and does not always eat breakfast. What concerns about this situation might you have?

Scenario B

The math teacher at the high school told the parents of 17-year-old John that he is surly in class, falls asleep often, is not consistently handing in homework, and made a “D” on the last test. John’s mother has asked you what to do. When she tried to talk with John, he became sarcastic and walked out. John has a part-time job at the local fast-food restaurant.