Legal and Ethical Aspects of Nursing

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Explain the legal requirements for the practice of nursing, and how they relate to a student nurse.

2 Identify the consequences of violating the nurse practice act.

3 Examine the issue of professional accountability, professional discipline, and continuing education for licensed nurses.

4 Compare and contrast the terms negligence and malpractice.

5 Discuss what you can do to protect yourself from lawsuits or the damages of lawsuits.

6 Differentiate a code of ethics from laws or regulations governing nursing, and compare the similarities of the codes of ethics from the NFLPN, NAPNES, and ANA.

7 Describe the NAPNES standards of practice.

1 Reflect on how laws relating to discrimination, workplace safety, child abuse, and sexual harassment affect your nursing practice.

2 Discuss the National Patient Safety Goals and identify where these can be found.

3 Interpret rights that a patient has in a hospital, nursing home, community setting, or psychiatric facility.

4 Describe three factors necessary for informed consent.

5 Explain advance directives and the advantage of having them written out.

accountability ( , p. 31)

, p. 31)

advance directive (p. 38)

assault ( , p. 40)

, p. 40)

assignment (p. 31)

battery (p. 40)

competent (p. 38)

confidential ( , p. 35)

, p. 35)

consent (p. 37)

defamation ( , p. 40)

, p. 40)

delegation (p. 31)

discrimination (p. 34)

do not resuscitate (DNR) ( , p. 39)

, p. 39)

ethical codes, ethical principles, ethics committee (p. 29)

ethics (p. 44)

euthanasia ( , p. 45)

, p. 45)

false imprisonment (p. 41)

health care agent (p. 39)

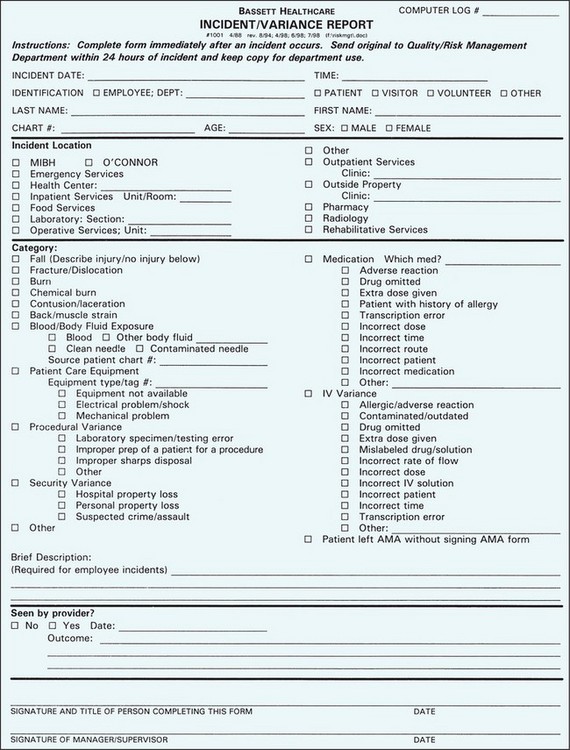

incident report (p. 42)

invasion of privacy (p. 40)

laws (p. 30)

liability ( , p. 38)

, p. 38)

libel ( , p. 40)

, p. 40)

living will (p. 38)

malpractice ( , p. 39)

, p. 39)

negligence (p. 39)

nurse practice act (p. 31)

Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) ( , p. 32)

, p. 32)

patient advocate ( , p. 39)

, p. 39)

privilege ( , p. 29)

, p. 29)

protective devices (p. 41)

prudent (p. 39)

reciprocity ( , p. 31)

, p. 31)

release (p. 38)

sentinel event (p. 35)

sexual harassment ( , p. 34)

, p. 34)

slander (p. 40)

standards of care (p. 32)

statutes (p. 30)

tort (p. 30)

whistle-blowing (p. 45)

An understanding of legal and ethical codes is essential for nurses to practice safely and to protect the rights of patients and co-workers. Nurses work in situations that give them privilege (permission to do what is usually not permitted in other circumstances) to a patient’s body and emotions. Laws define the boundaries of that privilege and make clear the nurse’s rights and responsibilities. Ethical codes (actions and beliefs approved of by a particular group of people) are different from laws, and are important because not all situations are covered by a law, and there may not be one right action. In these situations, ethical principles (rules of right and wrong from an ethical point of view) are applied, often by an ethics committee (a committee formed to consider ethical problems).

SOURCE OF LAW

Laws are rules of conduct that are established by our government (the specialized vocabulary used in reference to legal terms is defined in Box 3-1). In the United States, law comes from three sources: the Constitution and Bill of Rights; laws made by elected officials; and regulations made by agencies created by these elected officials. Constitutional laws, both federal and state, provide for basic rights and create the legislative bodies (senate and assembly) that write laws governing our lives.

Judicial law results when a law or court decision is challenged in the courts and the judge affirms or reverses the decision. This is called “establishing a precedent,” because in the future other judges will base their decisions on the preceding or earlier decision. Our federal Supreme Court is the highest court to which an appeal of a court decision can be brought. A well-known health care issue that has been ruled on by the Supreme Court was Roe v. Wade (1972), which established a woman’s right to obtain an elective abortion. More recently, state courts are hearing cases challenging laws that deal with abortion, euthanasia, and assisted suicide.

Administrative law comes from agencies created by the legislature. In health care, agencies such as the Department of Health and Human Services or Office of Professional Licensing oversee nursing and the other health care professions. These agencies write regulations or rules that control the profession and its practice. Administrative law governs schools of nursing, licensure, hospitals, nursing homes, and home health agencies, as well as health care insurance such as Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance company policies.

CIVIL AND CRIMINAL LAW

Statutes (laws) may be either civil or criminal. Civil law guarantees individual rights, and a tort is a violation of civil law. You may be guilty of a tort if you harm a patient, for example, by administering the wrong dose or type of medication. A lawsuit may result, and, if the defendant is found guilty, a monetary award may be given to the plaintiff.

A crime is a wrong against society, and imprisonment and/or fines may result if one is convicted of a crime. Criminal action charges in nursing could come about if a nurse was involved in drug diversion, patient abuse, intentional death, or mercy killing. Serious crimes are called felonies and are punished with long prison terms of a year of more, or even the death penalty; less serious crimes are misdemeanors, and may result in prison terms of less than a year, monetary fines, or both.

LAWS RELATED TO NURSING PRACTICE AND LICENSURE

State licensure is required to practice nursing in the United States, and each state writes its own laws and regulations regarding licensure, in what is called a nurse practice act. This law defines the scope of nursing practice, and provides for the regulation of the profession by a state board of nursing.

SCOPE OF PRACTICE

The nurse practice act in each state sets forth the scope of practice in that state. This includes the definition of nursing for the registered professional nurse (RN) and the licensed practical or vocational nurse (LPN or LVN) and may include definitions for advanced practice nurses such as nurse practitioners or nurse anesthetists. Nurse practice acts regulate the degree of dependence or independence of a licensed nurse with regard to other nurses, physicians, and health care providers. For example, an LPN/LVN practices under the direction of an RN, physician, or dentist. Nurses must follow the lawful order of a physician unless it is harmful to the patient, and must have a physician order to perform certain functions, such as administering prescription drugs or placing a patient in a protective device.

LICENSURE

Eligibility for licensure is determined by each state’s board of nursing, usually involving completion of an approved educational program. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing, which develops the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX), has a representative from each of the state boards of nursing in the United States who has input on the exam. A passing score on this computer-adapted test is accepted by the states for initial licensure when all other state requirements for eligibility are met. A current issue regarding licensure involves national licensure, or automatic reciprocity (recognition of one state’s nursing license by another state). Although a growing number of states have developed reciprocity agreements, nurses who wish to practice in more than one state may need to apply for the nursing license in each state in which they practice. National licensure would recognize a state license in all other states.

Student Nurses

Student nurses, although they are not yet licensed, are held to the same standards as a licensed nurse. This means that although a student nurse may not perform a task as quickly or as smoothly as the licensed nurse, the student will achieve the same outcome without harm to the patient. The student is legally responsible for her own actions or inaction, and many schools require the student to carry malpractice insurance. The instructor who supervises a student is responsible for proper instruction and adequate supervision and evaluation of a student. Instructors are responsible for assigning students to patients of an appropriate level of complexity so that they do not jeopardize patient safety. A student’s responsibility is to consult with the instructor when she is unsure in a situation, or when a patient’s condition is changing rapidly. Student nurses need to know the nurse practice act and its definition of nursing in the state in which they are practicing, and not exceed the scope of practice for their state. It is not legal to do something beyond the scope of nursing practice just because you were told to do so. Hospitals or health care agencies may impose limitations on student practice, but they may not add duties or responsibilities beyond the scope of practice in that state.

PROFESSIONAL ACCOUNTABILITY

Accountability is taking responsibility for one’s actions. Professional accountability is a nurse’s responsibility to meet the health care needs of the patient in a safe and caring way. In order to do so, students must prepare themselves in the classroom with theory’ the textbook description of patient needs and nursing interventions’and then apply that information in the clinical setting. Accountability means asking for assistance when unsure, performing nursing tasks in the safe and prescribed manner, reporting and documenting assessments and interventions, and evaluating the care given and the patient’s response to that care. As a licensed nurse, accountability means all of the above, plus a commitment to continuing education to stay current and knowledgeable.

Delegation

Delegation is the assignment of duties to another person. Some states differentiate between delegation (only to another licensed person) and assignment, which can be done to an unlicensed person, such as a nursing assistant. An LPN may supervise nursing assistants, technicians, or other LPNs (Assignment Considerations 3-1). The nurse is responsible for ensuring patient safety and the observation of patient rights. It is the delegating nurse’s duty to supervise and evaluate the care a licensed or unlicensed person provides.

Standards of Care

Legally, you are responsible for your actions under the nurse practice act and according to the standards of care that are approved by the profession. These standards are defined in nursing procedure books, institutional manuals of policies and procedures or protocols, and nursing journals that outline current skills or techniques. On a national level, standards of care have been identified and published for clinical practice and specialty areas by professional nursing organizations. These standards provide a way of judging the quality and effectiveness of patient care, and in legal cases determine whether a nurse acted correctly (see Boxes 1-1 and 1-2). Standards of care are continually being revised as better treatments and techniques are continually being updated and revised with nursing research. What is the standard today may not be the standard of care next year; therefore, it is crucial that the LPN/LVN keep abreast of current standards with continuing education.

PROFESSIONAL DISCIPLINE

State boards of nursing are also responsible for discipline within the profession. When a licensed nurse is charged with a violation of the nurse practice act, there will be a hearing to determine if the charges are true. The most common charges brought against nurses include substance abuse (drug and alcohol related), incompetence (doing something that can or did harm a patient, such as medication errors), and negligence (discussed later). It is considered negligence not to report another professional’s misconduct. When a nurse is found guilty of professional misconduct, the penalties may result in a temporary suspension or loss of licensure.

CONTINUING EDUCATION

Many states have adopted laws that require evidence of continuing education after a nurse has passed the licensing exam. Once licensed, it is expected that the nurse will function safely in any nursing situation. Therefore, it is necessary for nurses to continue their education about changes in health care practice, pharmacology, and technology in order to practice safely. Nurses may stay current by attending programs provided by their employer; through participation in their professional organization; by attending workshops, seminars, or presentations on health care topics; by reading professional nursing journals; by formal continuing education in colleges; or by correspondence courses.

LAWS AND GUIDELINES AFFECTING NURSING PRACTICE

When a licensed nurse accepts employment with an agency or individual, the nurse is bound to work within the law and regulations governing nursing in that state. There are also federal laws that regulate safety and health in the workplace, and forbid discrimination and sexual harassment. Although not law, the “Patient Care Partnership: Understanding Expectations, Rights, and Responsibilities” provides ethical guidelines for nursing practice (Box 3-2).

OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ACT (OSHA)

The Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) was passed in 1970 to improve the work environment in areas that affect workers’ health or safety. It includes regulations for handling infectious or toxic materials, radiation safeguards, and the use of electrical equipment. Health care agencies, as a result of OSHA requirements, provide mandatory orientation and continuing education regarding a wide range of topics from isolation procedures and blood-borne pathogen (disease-producing organism) exposure, to fire or bomb threats and lifting and evacuation procedures.

Safe storage and handling of toxic chemicals and drugs are important parts of OSHA. Each facility is required to keep a record of hazardous substances, which includes seemingly harmless liquids such as bleach and disinfectants, as well as obviously dangerous chemicals. The facility must store them properly in designated areas, and maintain material safety data sheets (MSDS), which outline the hazard the substance can pose. Employees must be updated on these workplace hazards and know the location of the MSDS collection.

CHILD ABUSE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT ACT (CAPTA)

The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) is a federal law. It was passed in 1973 and was rewritten in October 1996. This law defines child abuse and neglect as “any recent act, or failure to act, that results in imminent risk of serious harm, death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, or exploitation of a child by a parent or caretaker who is responsible for the child’s welfare.” A child is a person under the age of 18 unless state law specifies a younger age. Many children who are victims of abuse are too young to speak for themselves. CAPTA states that licensed health care personnel are required to report child abuse. Each facility usually has guidelines on how to report child abuse.

DISCRIMINATION

Discrimination is making a decision or treating a person based on a class or group to which he belongs, such as race, religion, or sex, rather than on his individual qualities. In 1964, federal legislation made it illegal for employers to discriminate (to hire, promote, or fire employees on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin). The law has been amended to include protection for people with disabilities, as well as discrimination based on age. Disability has been broadly interpreted to include physical or mental impairment that seriously interferes with a person’s ability to carry on one or more life activities. It particularly protects people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), or those who are recovering from drug or alcohol addiction. It is not legal for employers to ask questions on an employment application that would indicate race or other protected categories, or health status. It also requires employers to make reasonable accommodations for persons with a disability.

SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Sexual harassment is defined by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) as “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature.” Sexual harassment is illegal when it is used as a condition of employment or promotion or when it interferes with job performance. Sexual harassment prohibition has been further applied in schools and in the clinical setting. Student nurses and their instructors need to recognize what sexual harassment is; to refrain from conversation or actions that create a hostile, intimidating, or offensive atmosphere; and to report actions that are sexually harassing in the classroom or clinical setting. In our society, in which sexual comments and activities are commonplace on television or in movies, we must be aware of the right time and place for sexually suggestive or explicit words or touch. It is appropriate to state, “I am offended by your language (conversation, inappropriate touch).” If the sexually explicit or harassing behavior continues, it should be reported to your supervisor.

GOOD SAMARITAN LAWS

Good Samaritan laws are those that protect a health care professional from liability if she stops to provide aid in an emergency. In most states there is no legal requirement for a nurse to provide aid in an emergency, but if a nurse does provide care in an emergency, liability is limited unless there is evidence of gross negligence or intentional misconduct. These laws do not apply to employed emergency response workers.

PATIENT’S RIGHTS

In 1972, with revision in 1992, the American Hospital Association (AHA) developed the “Patient’s Bill of Rights,” a list of rights the patient could expect and responsibilities that the hospital may not violate. In 2003, this document was revised into “The Patient Care Partnership: Understanding Expectations, Rights, and Responsibilities” (see Box 3-2). Although this is an ethical, not a legal, document, state legislators have written laws that prohibit certain actions or guarantee particular rights. Since the first patient bill of rights, which was hospital oriented, many others have been published, particularly for residents of nursing homes and those in psychiatric units. These documents emphasize that patients continue to have rights even if they are helpless and sick. They seek to preserve the dignity, privacy, freedom of movement, and information needs of the patient.

Under some legally specified conditions, certain rights may be temporarily suspended, such as in an emergency when the patient is unconscious or unable to communicate. Other conditions would include the patient who is in danger of injury and cannot protect himself from harm, or to protect the public from harm. However, patients with psychiatric disorders in most states cannot be held against their will for more than 2 or 3 days, unless they are a distinct danger to self or others, or are gravely disabled, which means unable to provide for their basic needs of food, shelter, or clothing. The current principle is to protect the rights of harmless individuals to be different, to disagree with the majority, to live their own lives, and to seek their own solutions to private difficulties.

NATIONAL PATIENT SAFETY GOALS

The International Center for Safety of The Joint Commission (formerly known as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations [JCAHO]) has developed goals to promote specific improvements in patient safety. The goals attempt to provide evidence-based and expert-based solutions to areas that have been problematic in terms of patient safety. The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals are updated every year, and are available on their website (www.jcipatientsafety.org). It is in the best interest of patient safety and quality nursing care for all nurses to review these goals on an annual basis.

A sentinel event is an unexpected patient care event that results in death or serious injury (or risk thereof) to the patient. One of the National Patient Safety Goals is to improve the effectiveness of communication among caregivers, since the most frequently cited cause of a sentinel event by The Joint Commission is communication (Safety Alert 3-1). During “handoff” communication, there is a risk that critical patient care information might be lost due to lack of communication. One form of communication, termed the SBAR method of communication, is a strategy that reduces the likelihood of critical patient details being lost. SBAR is an acronym that stands for situation, background, assessment, and recommendation (Communication Cues 3-1).

SBAR is also useful when communicating with physicians, because nurses and physicians are taught different ways to communicate patient information in their educational processes. Nurses are taught to communicate in narrative form, and to include every possible detail, whereas physicians are taught to communicate using brief “bullet” points. This SBAR format encourages caregivers to communicate in a way that is concise, yet complete.

The National Patient Safety Goals and requirements apply to nearly 15,000 hospitals and health care organizations that are accredited by The Joint Commission. There are specific goals for numerous types of patient care areas, such as ambulatory care, assisted living, behavioral health, home care, long-term care, and others. The goals for hospitals are listed in Box 3-3.

LEGAL DOCUMENTS

When a person enters the health care system to visit a physician, clinic, hospital, or emergency room, or to receive home health care, a record is begun (or continued) that documents that person’s health status or problem and the care given. That record is a legal document that includes records of all assessments, tests, and care provided. The chart, or medical record, is confidential (kept private), meaning that only people directly associated with the care of that patient have legal access to the information in the chart. The chart is the property of the hospital or agency or physician, not the patient. However, the patient does have the right of access to the chart, and copies of information in the chart may be authorized by the patient to be provided to other agencies’for example, if a patient transfers from one physician or health care facility to another. Health care researchers and insurance companies may also gain access to chart information with the patient’s permission.

Student nurses must protect the confidentiality of their patients. Charts may not be copied by students to use for report purposes. Reports or notes on patients used for school purposes (case studies, nursing care plans, student task or skills lists) should not identify the patient by name. Case discussion should indicate “a 67-year-old man” rather than “Mr. Joe Morales.”

As a legal document, the chart is used to determine the truth of what happened’what was done or not done’to a patient during a period of time. Therefore, its contents always need to be accurate, pertinent, and timely. Erasures or changes to a patient’s chart may suggest covering up or dishonesty. Charting should be focused on the patient, and the nursing care provided. Remember that the chart may be introduced as evidence in a court case, and do not make inappropriate chart notations. Charting guidelines are covered in Chapter 7.

HEALTH INSURANCE PORTABILITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY ACT (HIPAA)

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) called for the creation of regulations regarding patient privacy and electronic medical records. Failure to comply with the rules may lead to civil penalties. Intentional violation of the regulations can lead to sizable fines and time in jail. Box 3-4 presents the six patient rights covered in these regulations.

A considerable amount of information about patients is shared among health care professionals within an agency each day. The new federal privacy regulations took effect in April 2003. The privacy rules, which are part of HIPAA, protect the way patient information is conveyed and stored. HIPAA also dictates to whom information may be revealed. Many nurses are now afraid to share any patient information with family members for fear of violating the HIPAA privacy rule. The rule states that disclosing medical information to family members, close personal friends, or other individuals identified by the patient for involvement in the patient’s care is permitted if the patient does not object. It is important, then, to make certain you have the patient’s consent to relay information about his health care to family members. It is also important to know and follow the hospital’s policies as well.

The HIPAA rules also give patients the right to the information in their medical records as well as the right to emend an erroneous record. Privacy and confidentiality of patient information have always been part of the ethical code of nurses, physicians, and health care facilities; the new rules have simply increased awareness of the need for confidentiality and imposed new guidelines. Charts and flow sheets must be secured and not left where they may be viewed by others. Public displays of patient information (on a white board in the nurse’s station for example) are not acceptable. Nurses need to be careful with printouts, such as the Kardex sheet or Care Plan, and be certain that they are shredded or disposed of properly when the shift is over. When working with a patient in a double room or multiple-bed ward, voices need to be lowered to prevent others from hearing what is said. Patients must sign a specific release form if they desire information be sent to another agency, physician, or insurance company (Legal & Ethical Considerations 3-1).

CONSENTS AND RELEASES

A consent is permission given by the patient or his legal representative. Consents or releases are legal documents that record the patient’s permission to perform a treatment or surgery, or to give information to insurance companies or other health care providers (Box 3-5).

Informed consent indicates the patient’s participation in the decision-making process. The person signing must have knowledge of what the consent allows and be able to make a knowledgeable decision. In a consent for surgery or treatment, the patient must be told, in terms he can understand, the risks and benefits of the proposed treatment, what the consequences may be of not having the procedure done, and the name of the health care professional who will perform the procedure. This information is usually provided by the professional performing the procedure. If the patient has any questions, they should be satisfactorily answered before the patient signs the consent. It is important to determine that proper consent has been obtained, both legally and ethically. Failure to obtain a valid informed consent may lead to charges of assault and battery, or invasion of privacy. (These charges are fully explained later in this chapter.)

In order to be valid, a consent must be signed by the person or the legal agent for that person. Consents must be freely signed without threat or pressure, and must be witnessed by another adult. Consent can be withdrawn at any time before the procedure or treatment is started. When a person is older than 18 years and competent, he must sign the consent for treatment. A competent person is one who is legally fit (mentally and emotionally). A person is considered incompetent if he is unconscious, under the influence of mind-altering drugs (including alcohol or narcotics, such as “premedication” for the procedure), or declared legally incompetent, such as in cases of chronic dementia or mental deficiency. In these situations, a next of kin, appointed guardian, or one who holds a durable power of attorney (discussed later) has legal authority to give consent. Minors (younger than 18 years) may not give legal consent; their parents or guardians have this right. If a child’s parents are divorced, the custodial parent is the legal representative. Stepparents usually cannot give consent unless they have legally adopted the child. An emancipated minor, or one who has established independence by moving away from parents or through service in the armed forces, marriage, or pregnancy, is considered legally capable of signing a consent.

Implied consent is assumed when, in a life-threatening emergency, consent cannot be obtained from the patient or family. The law agrees with this. Consent may be obtained by telephone if it is witnessed by two persons who hear the consent of the family member.

A release is a legal form used to excuse one party from liability (responsibility). A commonly used release is a Leave Against Medical Advice (or Leave AMA). This form is used by a hospital or facility when a patient does not accept the physician’s recommendation for hospitalization, and leaves the agency. The form documents that the reasons for continuing hospitalization or treatment, and risks of leaving without treatment, have been explained to the patient. If the patient refuses to sign the release, that is noted and witnessed. The term release may also refer to forms used to authorize an agency to send confidential health care information to another agency, school, or insurance company.

WITNESSING WILLS OR OTHER LEGAL DOCUMENTS

Occasionally, nurses may be asked to witness a will or other legal document. Although there is no legal reason not to do so, most hospitals and health care agencies have policies against this. The reason is that wills or legal documents may be contested, and the nurse who witnessed the document can be called to court to testify regarding the patient’s health or mental condition, or relationship to visitors. To avoid this conflict, hospitals often provide business office personnel or a notary public to witness the signature. To witness the signing of a legal document, you need not know the content of the document. Legally, it is necessary only that the witness confirms that the signature or mark is made under no influence (drug or otherwise) and that the person knows what he is signing.

ADVANCE DIRECTIVES

An advance directive, sometimes called a “living will,” is a consent that has been constructed before the need for it arises. It spells out a patient’s wishes regarding surgery as well as diagnostic and therapeutic treatments. Clear direction for making decisions is then present if the patient suffers an accident or illness that results in the patient being unresponsive or incompetent, and unable to make the decision. This has become very important because technology in health care allows the prolonging and maintaining of life with sophisticated treatments that may cause conflict among family members or between the health care professionals and the family as to how the patient would want to live (or die) in this situation. When a person puts in writing his wishes regarding life support and the use of medical technology, both the medical community and the family have clear direction. A durable power of attorney is a document that gives legal power to a health care agent (surrogate decision maker), who is a person chosen by the patient to follow the patient’s advance directives and make medical decisions on his behalf.

All 50 states recognize advance directives, but each state regulates advance directives differently, and an advance directive from one state may not be recognized in another, depending on the similarities or differences in their laws. Advance directives do not expire; it is a good idea for the patient to review his advance directive periodically, to be certain it still reflects his wishes. Historically, emergency medical technicians (EMTs) have not been able to honor advance directives. Therefore, if a patient had an advance directive limiting the types of care he wanted, and a loved one called 9-1-1, the EMTs had to perform any and all procedures to stabilize the patient and bring him to the hospital. Many states have enacted laws to allow EMTs to honor DNR orders and/or advance directives, provided documentation is available at the scene.

Do not resuscitate (DNR) orders are written by a physician when the patient has indicated a desire to be allowed to die if he stops breathing or his heart stops. In this situation, no cardiac compressions or assisted breathing (cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR]) would be started. It is very important for nursing personnel to know who is to be resuscitated and who is NOT. A nurse who attempts to resuscitate a patient who has a physician’s DNR order would be acting without the patient’s consent, and committing battery.

It is also illegal to call for or participate in a “slow code.” In a slow code, there is no DNR order but staff do not respond quickly to a patient who has stopped breathing or whose heart has stopped, so that the CPR will not be effective. This is usually done because the patient has a terminal condition.

VIOLATIONS OF LAW

There are a number of civil laws that nurses need to know about in order to practice safely and within the legal system. A nurse needs to know not only the law in regard to her own practice but also how to act as a patient advocate, one who speaks for and protects the rights of the patient.

NEGLIGENCE AND MALPRACTICE

Negligence is simply defined as failing to do something a reasonably prudent (sensible and careful) person would do, or doing something a reasonably prudent person would NOT do.

Malpractice is negligence by a professional person. The person does not act according to professional standards of care as a reasonably prudent professional would. In nursing malpractice, a reasonably prudent person is a similarly educated, licensed, and experienced nurse. An example of nursing malpractice would be if a nurse did not check the patient’s vital signs and condition after surgery, there was hemorrhage, and the patient went into shock and died.

In order to prove malpractice, there are four elements that must be present: duty, a breach of duty, causation, and injury (Box 3-6). If even one of these four elements is not present, the nurse was not guilty of malpractice. For example, if a nurse made a clinical error that did not result in harm to the patient, the event would not be considered to be malpractice; however, it would be a deviation from the standard of care, and as such could be grounds for discipline by the employer, the licensing board, or both.

COMMON LEGAL ISSUES

Nurses have access to private information and personal contact that is permitted by their professional caregiver role. With that right to information and touch come legal responsibilities to respect the patient’s privacy, to protect the patient’s safety, and to ensure the patient’s right to make decisions. When legal boundaries are violated, and injury occurs, nurses may be subject to litigation (a lawsuit).

Assault and Battery

Assault is the threat to harm another, or even to threaten to touch another without that person’s permission. The person being threatened must believe that the nurse has the ability to carry out the threat. Battery is the actual physical contact that has been refused or that is carried out against the person’s will. An example of assault would be the nurse who says “If you don’t let me give you this injection, two other nurses will hold you down so I can give it to you.” Battery would occur when a patient is held down to receive an injection he has refused. It would also include the rough physical handling of an excited, confused, or psychotic patient in ways that would be described as angry, violent, or negligent.

Adults who are alert and oriented have the right to refuse medications, baths, treatments, dressing changes, irrigations, insertion of a catheter, and diagnostic tests as well as surgery. Even if the test or procedure is necessary for the well-being or comfort of the patient, the patient has the legal right to refuse. It is the nurse’s responsibility to explain the reason why a particular drug or treatment is important. However, if the patient still refuses, the nurse should obtain a release from liability because the treatment is not done or the drug is not taken. Performing a procedure without the proper consent is battery (except in emergency situations when the patient is unable to give consent).

Defamation

Defamation is when one person makes remarks about another person that are untrue, and the remarks damage that other person’s reputation. There are two forms of defamation: slander (oral) and libel (written). Two nurses may be overheard talking about a physician in a way that holds the physician up to ridicule or contempt. If another person decides never to use that physician because of the derogatory comments, the physician’s reputation is damaged and the nurses may be guilty of slander. An example of libel is a letter or newspaper article quotation that states that a person is incompetent or dishonest. The loss of respect for and trust of the person may result in damage to his reputation and loss of business. A person sued for slander or libel may be found innocent if the statements made were true, or were said or written with no intent to harm the person, but for a justified purpose.

Invasion of Privacy

Invasion of privacy occurs when there has been a violation of the confidential and privileged nature of a professional relationship. When patients entrust themselves to our care, it is with the expectation of confidentiality’that what is told to the health care professional and what is learned about the patient’s health and personal history is private information to which no one else should have access.

Invasion of privacy occurs when unauthorized persons learn of the patient’s history, condition, or treatment from the professional caregiver. It might include the nurse’s giving information over the telephone to a caller who asks about the patient’s condition. It occurs when health care workers are overheard carelessly discussing their patients in the elevator or cafeteria. It occurs when a next-door neighbor asks about another neighbor who is in the hospital and the nurse tells him about the patient’s condition. It occurs when a nurse, out of curiosity, reads the chart of a public figure who has been admitted to her unit, but to whom the nurse is not assigned or responsible. Releasing information to a newspaper, another health care agency, an insurance company, or a person without the patient’s valid consent is invasion of privacy. However, nurses are required by law in most states to report information regarding child or elder abuse, sexual abuse, or violent acts that may be crimes (stab or gunshot wounds). When such reporting is done in good faith, the nurse cannot be held liable for invasion of privacy. Nurses must be aware of the required reporting procedures for abuse or crime where they work.

Invasion of privacy extends to leaving the curtains or door open while a treatment or procedure is being done, or to leaving patients in a position that might cause them loss of dignity or embarrassment. Exposing the patient’s body more than necessary, or leaving a confused and agitated patient in a hallway where he might behave in ways that would be embarrassing if he were not confused and agitated, are also examples of invasion of privacy. Interviewing a patient or family member in a room with only a curtain between the patients, or where conversation can be overheard, allows confidential information to be heard by unauthorized persons. The reasonable and prudent nurse does for the patient what the patient cannot do for himself’covers the patient’s body, protects him from public exposure, and preserves his dignity.

A growing area of concern regarding privacy has to do with computerized data banks and the Internet. Many health care agencies are computerizing their records, and nurses (as well as physicians, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, dietitians, and unit clerks) can enter information about patients in that facility as well as retrieve it. Nurses must be careful to ensure the patient’s privacy when entering or using data in a computer network. HIPAA, discussed earlier in the chapter, sets rules governing transmission of patient data (electronic, telephone, fax), such as the requirement that the sending facility must have reasonable safeguards in place to ensure the data are sent where they were intended to be sent and are treated in a confidential manner. A national data bank is envisioned in the future that could allow health care practitioners to access a patient’s medical record wherever that patient sought care’from California to New York, from a clinic to a major medical center, from a private practice physician to a pharmacist at the local drugstore’but the need for safeguards to prevent unauthorized access, as well as the reluctance of many people to have confidential health information so readily accessible, may delay this from becoming a reality very soon.

False Imprisonment

Just as a patient has the right to refuse medications or tests or treatments, a patient has the right to leave a hospital or health care facility or to move about in it. Preventing such a person from leaving, or restricting his movements in the facility, is false imprisonment. When a person wants to leave the hospital against the advice of the physician, a release to leave “against medical advice” (AMA) is used. The patient, by signing the form, releases the hospital and staff of any consequences that occur as a result of the patient’s leaving. It is also important to follow your facility’s policies regarding a competent adult who wishes to leave AMA. The policy may include finding out the reason why the patient wishes to leave, informing the physician, informing the patient of the risks of refusing treatments, and carefully documenting all aspects of the situation.

Persons who have psychiatric disorders may be admitted to a psychiatric unit on a voluntary or involuntary basis. A person who is admitted voluntarily agrees to the admission and can refuse or accept any treatment, and can leave the facility as a regular discharge. If the physician believes the patient should not be discharged, the patient can sign an AMA release.

An involuntary admission is made against the patient’s wishes, to protect him from self-harm or from harming others. There is a limit to the time (usually 72 hours) a person can be detained without consent. During that time, if the patient does not agree to a voluntary admission, and there remains the belief that the person is a threat to self or others, two psychiatrists can petition a judge to issue a court order for the patient to be held in the psychiatric facility for a specific period of time.

Protective Devices.: The inappropriate use of devices that limit a person’s mobility is a nursing action that can result in charges of false imprisonment. Protective devices may be mechanical, such as locks, rails, belts, or garments that prevent a person from getting out of a room, bed, or chair, or they may be chemical: drugs such as sedatives or tranquilizers that so sedate the patient that he is unable to move about. A physician order is necessary for any protective device, mechanical or chemical. Creative nurses and health care facilities have developed ways of allowing for mobility while protecting the confused or agitated person from danger. Nurses must be alert to the abuse of protective devices when other less restrictive techniques may be effective. Clearly a reasonable and prudent nurse will carefully assess a patient’s potential for falls or other harm, and document the need for and proper application of physician-ordered protective devices to ensure the patient’s safety. Nurses should consult with their supervisor about using protective devices in an emergency situation when no physician order is available. Documentation of the need to protect the patient from harm and securing the physician order as soon as possible protect the nurse from liability for charges of false imprisonment or malpractice.

DECREASING LEGAL RISK

Although nurses cannot prevent a lawsuit from being filed, several nursing actions can reduce the likelihood of a suit (Box 3-7). First and most important is competent and well-documented nursing care. Nursing competence is defined as possessing the suitable skill, knowledge, and experience necessary to provide adequate nursing care. Establishing rapport and effective communication skills can create a relationship in which patient anger or misunderstanding can be resolved rather than grow to lawsuit proportions. Competence in nursing also includes following the proper policies and procedures and upholding the standards of care. Sometimes in nursing you may observe another nurse “bending the rules” in an unsafe way to save time; as a novice in the field, you may feel peer pressure to do things in a way that is “the way things are done on this unit.” Rule bending might appear to be the only solution on a unit that is chronically understaffed, but it only provides a temporary solution. What is more likely needed is a permanent change in the situation that will make rule bending unnecessary. If there are hospital rules that are out-of-date or unrealistic, it is important to get involved (e.g., on the hospital’s policy committee) to change these rules, rather than work around them.

Situations sometimes occur in which a patient believes he has suffered an injury or loss. Documentation is the key element in proving that nursing actions used were appropriate, thus protecting the nurse from liability.

Potential lawsuits may be avoided by early identification of dissatisfied patients. Many facilities have risk management teams composed of people specially trained to deal with situations that may put the facility at risk for a lawsuit. Part of a comprehensive risk management program would include in-service programs to promote safety, preventive maintenance for equipment and the physical plant, and counseling and interventions in situations that pose potential for lawsuits.

Incident or Occurrence Reports

If there is an occurrence that is out of the ordinary, an incident (occurrence) report is often used to document what happened, the facts about the incident, and who was involved or witnessed it. The incident report is a tool used by the risk management department (see Chapter 10). This report is useful for several reasons. It allows the facility to note dangerous patterns’for example, if several visitors or staff have tripped and fallen in the same location, or if a change in the appearance of a medication might have been a factor in several recent similar medication errors. The incident report also serves as an immediate recall of an occurrence that may result in injury or damages and future lawsuit. Some examples of when an incident report might be written include when a medication error is made, a patient falls out of bed, or a visitor faints in the hall (Figure 3-1). Incident reports are generally not filed as part of the patient’s chart; no reference to the incident report is made in the patient’s chart, although the medically relevant details about the incident, if they relate to patient care, should be included in the progress notes. Incident reports should be timely, factual, and concise, and should not contain unnecessary details, such as explanations about why the event might have occurred.

Liability Insurance

Liability insurance does not provide protection from being sued. It can, however, protect the livelihood and assets of a nurse should the nurse get sued. If a nurse is sued, liability insurance pays for the expenses of a lawyer to defend the nurse and pays any award won by the plaintiff up to the limits of the policy. It may also pay for attorney costs and related costs if the nurse is subjected to review by the state board of nursing. Having liability insurance does not increase the nurse’s chances of being sued, and most authors agree that it is unwise to rely on your employer’s liability insurance policy to protect you, because there may be situations in which the interests of the institution are at odds with your legal interests. Nursing liability insurance is relatively inexpensive, and is available through nursing organizations as well as private insurance companies.

ETHICS IN NURSING

Ethics or ethical principles are rules of conduct that have been agreed to by a particular group. They are based on the consensus (agreement) of the group that these rules are believed to be morally right or proper for that group. Professional groups such as physicians, nurses, and lawyers have developed codes of ethics that guide the person in that profession to act in ways approved by the group. Ethics are different from laws, in that they are voluntary. There are no prescribed legal penalties for violating a code of ethics, although in many instances, violation of a professional code of ethics may result in disciplinary action by a licensing or regulating agency. In some cases, ethics and the law overlap’for example, in dealing with issues of confidentiality. But in many cases, ethics deal with ideals or situations in which there is no right or wrong solution to a problem and about which thoughtful, caring people may hold opposing views. Areas of debate continue about life-and-death issues such as abortion, life support, and euthanasia.

Ethics are closely linked with values, the worth or importance of an action or belief to an individual. An ethical dilemma (problem or conflict) may result when people hold differing values. Codes of ethics attempt to provide a framework for making professional decisions.

CODES OF ETHICS

The International Council of Nurses (ICN), the American Nurses Association (ANA), the National Association for Practical Nurse Education and Service (NAPNES), and the National Federation of Licensed Practical Nurses (NFLPN) have developed codes of ethics for nurses (Box 3-8). Although the codes are worded differently, they have many commonalities. They all indicate the following:

• A respect for human dignity, the individual, and provision of nursing care that is not affected by race, religion, lifestyle, or culture.

• A commitment to continuing education, to maintaining competence, and to contributing to improved practice.

• The confidential nature of the nurse-patient relationship, outlining behaviors that bring credit to the profession and protect the public.

In addition, NAPNES has set standards for nursing practice since 1941 (Box 3-9). The standards represent the foundation for the provision of safe and competent nursing practice. Competency implies knowledge, understanding, and skills that transcend specific tasks and is guided by a commitment to ethical/legal principles. Box 3-10 refers to the NFLPN Code for Licensed Practical/Vocational Nurses (see also Appendix 4).

ETHICS COMMITTEES

Many health care facilities have ethics committees that are composed of people from various departments such as nursing, medicine, surgery, psychiatry, pharmacy, legal, economics, spiritual, and social work. Together they develop policies, address issues in their facility, and come to a better understanding of ethical dilemmas from different viewpoints.

ETHICAL DILEMMAS

Many ethical dilemmas may face the nurse today. A current issue revolves around life-and-death decisions. When a patient is diagnosed with a terminal illness, there are often conflicting opinions among family members and even the health care team about seeking life-prolonging treatment versus refusing such treatment. Patients have the right to information about alternative as well as conventional treatment options, with their risks, consequences, and benefits. Nurses must honor the right of the patient to choose or refuse any treatment or procedure, even if it would not be the nurse’s choice.

Perhaps even more difficult is the choice to initiate or terminate life support or treatment. Questions of whether to allow a patient to stop artificial feedings, or not to treat an infection with antibiotics in a terminally ill person, often raise uncomfortable feelings in nurses. Respecting and supporting a patient’s informed choice regarding treatment is respecting the patient’s right to self-determination. Providing compassionate care at the end of life honors the person’s decision to live his remaining time in the way he chooses.

Another ethical issue involves assisted suicide, which is aiding a person (providing the means) to end his life. The Supreme Court in June 1997 held that there was no constitutional right to physician-assisted suicide. Legally, at this time assisted suicide is a crime except in Oregon, which has enacted an assisted suicide law. Assisted suicide is often confused with euthanasia, or mercy killing. Euthanasia is the act of ending another person’s life, with or without the person’s consent, to end actual or potential suffering. It is not legal in any state.

Yet nurses may have to deal with a patient who asks for help to die. Participation in assisted suicide is a violation of the ANA Code for Nurses, as well as the ethical tradition of “do no harm.” The issue remains very controversial, with caring people holding different values.

On a daily basis, nurses face personal ethical decisions involving honesty, whistle-blowing (reporting illegal or unethical actions), and provision of care. Our professional code of ethics dictates that we act as patient advocates and safeguard our patients from harm. Who will know if a nurse gives a wrong medication, or fails to assess an unconscious patient? Should a nurse report suspected incompetence or impairment of a fellow nurse or physician? What care can be omitted in a short-staffed unit where all the needs are urgent? How does a nurse treat difficult patients’those who are abusive or who arouse feelings of anger or hatred, such as a person convicted of brutal crimes?

Nursing codes of ethics provide guidelines for behavior that promote excellence in patient care and the profession. They promote values such as dignity, honesty, integrity, and compassion.

On an institutional level, the question of “which of many patients is chosen for the liver transplant?” may occupy an ethics committee. On a state and national level, legislators choose where to spend money, and write laws that affect health care. Those decisions are influenced by ethics and values, and nurses can have an impact by sharing their ethical concern for patients and speaking up for patients’ rights.

Nurses can consciously consider what is right or wrong for them, in light of personal values. When a nurse feels confused or conflicted about the right course of action in a situation, talking with other nurses, the unit supervisor, or the ethics committee in the agency can assist the nurse to solve the problem from an ethical viewpoint.

NCLEX-PN® EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Choose the best answer(s) for each of the following questions.

1. The practice of nursing is regulated by:

2. Which of the following actions would be considered an invasion of a patient’s privacy? (Select all that apply.)

1. Discussing the comatose patient’s condition with his father-in-law.

2. Discussing the outcome of a patient’s test with another nurse from the unit while in an elevator with other people.

3. Relaying information about the patient’s concerns to the nurse who will care for him on the next shift.

4. Relaying a complaint by the patient’s wife to the charge nurse.

5. Posting a blog on your personal website about a difficult clinical day, including information about the hospital and patient’s diagnosis but NOT stating the patient’s name.

3. Which of the following actions would be classed as assault? (Select all that apply.)

1. Telling the patient for the second time that you will bring the pain medication as soon as it is time for it.

2. Restraining the patient’s feet because he is kicking the nurse when an injection is to be administered.

3. Threatening not to bring a meal tray if the patient won’t behave.

4. Grasping the patient’s upper arm snugly when administering a subcutaneous insulin injection.

5. Informing the patient that if he attempts to get out of bed one more time, he will be restrained.

4. For a nurse to be found guilty of malpractice when a patient has been injured, it would have to be shown that she did not:

1. take responsibility for a medication error.

2. do what a reasonably prudent nurse would have done in a similar patient care situation.

3. remember to put up the side rails on the bed to prevent the patient from falling out of bed.

4. keep the details of a patient’s diagnosis and care private.

5. An advance directive is a consent that:

1. gives a relative the power of attorney over financial affairs.

2. spells out the incapacitated patient’s wishes regarding tests and treatments.

3. provides consent for specific organs to be donated in the event of death.

4. puts the burden of medical decisions on a close relative or friend.

6. The visitor of one of your patients, stops you in the hall and says, “I hope you will not try to revive my neighbor if her heart stops.” The correct response is:

1. “That decision is up to the physician.”

2. “We are all trained in CPR.”

3. “I understand your concern, but I can’t discuss your neighbor’s care with you.”

7. A physician advises a patient to accept intravenous fluids, which she refuses. The nurse says to the patient, “You must have the fluids if you want to stay in the hospital and have us take care of you.” The nurse is:

1. correct in insisting on fluid replacement.

2. violating the patient’s right to refuse treatment.

3. not providing specific enough information about the options available for fluid replacement.

4. giving information so the patient can make an informed refusal of fluids.

5. wrong in speaking to the patient; the daughter should make the decision for or against fluid replacement.

8. Your newly admitted patient is found wandering in the hall. An aide helps her back to bed, and asks you if the patient should be placed in a protective device to keep her from wandering. You tell the aide to use a protective device. By providing this instruction, you are:

9. Your patient asks you, “What do you think of my physician?” You mention that the physician doesn’t seem to care about her patients, or how well their symptoms are managed. As a result, the patient switches to another physician. The physician may have grounds to sue you for:

10. For a patient to successfully win a malpractice claim, which of the following elements must be proven? (Select all that apply.)

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES ? Read each clinical scenario and discuss the questions with your classmates.

Jose Morales is a 46-year-old husband and father of two grown children. He has painful metastatic bone cancer. He is being discharged with a pain management program that still does not completely ease his pain. He tells you that he plans to “end it all” once he is at home, and asks you to help him with information about what kind and how much medication it would take so his death did not look like suicide. He also warns you not to tell anyone of his plans, because of “confidentiality.”

Scenario B

You are a staff nurse at a skilled nursing facility on the evening shift. One 66-year-old woman who is very confused and agitated is pacing in the halls, entering other residents’ rooms, and attempting to leave the building. Another nurse grabs the patient roughly and shouts at her, “If you don’t stay in your room, I’m going to tie you in that bed.” The nurse escorts the patient to her room, pushes her into a chair, and ties a sheet across the patient’s lap to prevent her from getting out of the chair.