Common Psychosocial Care Problems of the Elderly

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Discuss general principles of care for elderly patients with altered cognitive functioning.

2 Assist with assessment of cognitive changes in the elderly patient.

3 Differentiate characteristics of delirium, dementia, and depression.

4 Identify options for keeping the cognitively impaired senior safe.

5 Implement strategies to decrease agitation, wandering, sundowning, and eating problems in patients.

6 Identify the interrelationship between alcoholism, depression, and suicide in the elder.

7 Identify the four main categories of elder abuse.

8 List five crimes commonly occurring to the elderly.

9 Discuss two future psychosocial issues for the elderly.

1 Formulate a plan of care for the cognitively impaired elder.

2 Demonstrate the ability to interact therapeutically with patients with depression and suicidal tendencies.

age-associated memory impairment ( , p. 848)

, p. 848)

Alzheimer’s disease ( , p. 852)

, p. 852)

behavior modification (p. 853)

benign senescent forgetfulness ( , p. 848)

, p. 848)

creative behavioral therapies (p. 850)

delirium ( p. 849)

p. 849)

dementia ( , p. 849)

, p. 849)

depression ( , p. 854)

, p. 854)

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) ( , p. 856)

, p. 856)

nocturnal delirium ( , p. 849)

, p. 849)

paranoia ( , p 854)

, p 854)

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (p. 856)

Several factors influence the psychosocial status of the elderly, including functional limitations and external forces. Cognitive impairments, such as dementia, and physical care problems, such as altered mobility, are two examples of functional limitations. External forces may include economic and environmental factors such as income, housing, technology, geographic area, community resources, and crime. Individual life circumstances, such as loneliness and depression leading to alcohol abuse or the lack of a support system, can also influence the elder’s overall well-being. These factors, individually or in combination, all affect the way elders perceive the health care system and ultimately respond to illness.

CHANGES IN COGNITIVE FUNCTIONING IN THE ELDERLY

There are many misconceptions about the mental functioning of the elderly due to the negative attitudes of our American society toward growing old. People often assume that mental confusion, forgetfulness, and inappropriate behavior are typical of aging. However, very few changes in cognition are attributable to age-related factors alone.

The terms benign senescent forgetfulness and age-associated memory impairment are often used to describe age-related changes in mental processes. These changes include a modest decline in short-term memory and a slight and gradual decline in cognitive skills such as calculation, abstraction, word fluency, verbal comprehension, spatial orientation, and inductive reasoning. The elderly are as capable of learning new things as younger people, but their speed of processing information is slower.

Examples of mental changes that are not due to the normal aging process include confusion, disorientation, inappropriate behavior, depression, and the inability to concentrate or follow directions. Any major declines in cognitive functioning typically result from diseases such as dementia and metabolic disorders; stress, such as relocation; alcohol abuse or undesirable medication effects; and vision or hearing impairments. Dispiritedness and depression can occur from becoming withdrawn and detached from social interaction.

ASSESSMENT OF COGNITIVE CHANGES IN THE ELDERLY

The older adult with significant changes in mental functioning should be given a comprehensive mental status examination using a tool such as the Mental Status Questionnaire (MSQ). A detailed and accurate medical history and physical examination should also be performed prior to making a judgment about the cause of altered mental functioning.

As a nurse, you need to understand that disorientation and other mental symptoms can have a physiologic basis. You should carefully observe elderly and confused patients and question them and significant others about events preceding admission. Be sure to exercise patience and allow enough time for the elder to respond to questions. Compensate for sensory limitations during all interactions. Assess for factors that may contribute to an altered mental state, such as medication effects, a new environment, disease processes such as pneumonia or a urinary tract infection, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, or psychosocial stressors. All information should be accurately and promptly reported to assist in the appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

COMMON COGNITIVE DISORDERS IN THE ELDERLY

Patients with confusion have difficulty remembering, learning, following directions, and communicating their needs. Mental confusion can significantly influence a patient’s dignity, independence, personality, and support system and may complicate diagnosis and treatment of a patient’s illness. It can be caused by delirium, dementia, or numerous other often reversible conditions as listed in Box 41-1.

DELIRIUM

Delirium is an acute confusional state that can occur suddenly or over a long period as a result of an underlying biologic cause or psychological stressor. Some causes include stroke, tumors, systemic infection, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, acute inflammatory disorders, drug reactions, toxins, and sensory deprivation or overload. If left untreated, delirium can lead to coma or death. Nocturnal delirium, or sundown syndrome, is the appearance or increase of symptoms of confusion or agitation associated with the late afternoon or early evening hours and usually continuing into the night (Box 41-2). Little is known about this disorder, which poses a management problem for caregivers. Impaired mental status, dehydration, interruptions in sleep, and recent relocation may contribute to sundowning.

DEMENTIA

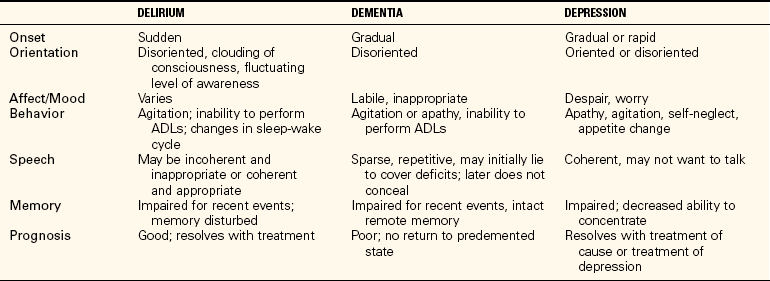

Dementia is generally a permanent condition characterized by several cognitive deficits. It is characterized by a slow, insidious onset that affects memory, intellectual functioning, and the ability to problem-solve. Primarily seen in Alzheimer’s disease, it also occurs with brain tumors or with serious medical or surgical disorders. Symptoms of dementia may mask depression. The reverse is also true: The depressed person may present with symptoms similar to dementia, such as confusion and disorientation. Thus careful assessment is essential to determine the cause of the patient’s symptoms. Table 41-1 differentiates delirium, dementia, and depression.

The cognitive losses associated with dementia, delirium, and depression are similar; however, each person experiences cognitive changes at different rates, and each responds differently to interventions. Thus interventions must be individualized, with ongoing commitment from both the health care team and family. General principles of care for elders with altered cognitive functioning are summarized in Box 41-3.

Specific Interventions for Confusion and Disorientation

Psychosocial Measures.: Because there is little treatment for elders with dementia, a behavioral approach is essential to enhance the elder’s quality of life. Two basic types of behavioral management are psychosocial interventions and medication. The plan of care should also include considerations for the patient’s family.

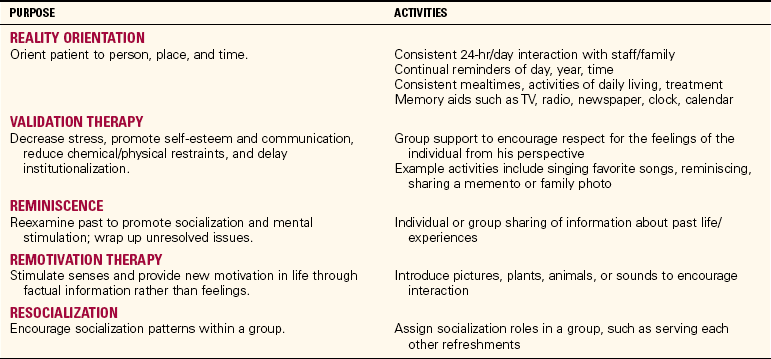

The primary goal of psychosocial interventions is to produce a feeling of well-being in the confused and disoriented elder. Although therapy is usually implemented by a social worker or the activity department, you can support therapy during patient care and evaluate changes in the patient’s behavior to revise the plan of care as needed.

There are a variety of therapies to help patients who are experiencing confusion and disorientation regain their sense of who they are, and what is happening in the environment around them. It is important to note that once a therapy is initiated, it should be used consistently by everyone in contact with the patient, including the family, to avoid further confusion. Table 41-2 presents several types of psychosocial approaches, their purpose, and related activities.

Other psychosocial interventions include creative behavioral therapies such as art, music, and humor that can allow for self-expression and alleviate anxiety and depression. The goal of creative therapies is to slow the rate of deterioration and prevent institutionalization as long as possible. Having pets available can also meet many needs. They can be someone to talk to, care for, and satisfy the need for touch. Pets may help a person deal with the loneliness caused by the many losses experienced in old age, such as decreased income, death of a spouse, and loss of independence (Figure 41-1).

Pharmacotherapy.: Before any drugs are used to deal with problem behaviors, all other types of nursing interventions must first be used, with documentation of their effectiveness. It is important to use drugs for valid psychological problems, and not just for behaviors that are annoying to others.

Adaptation is necessary when using psychotropic drugs with the elderly. Many psychotropic drugs require an extended period of time to have a therapeutic effect. Toxicity and undesirable side effects such as constipation and orthostatic hypotension are not uncommon. Because of chronic health problems in an individual, some medication may be contraindicated or require careful administration. Thus patient and family teaching about medications is essential.

Major tranquilizers, such as chlorpromazine (Thorazine) or haloperidol (Haldol), are often prescribed to manage the anxiety, agitation, hostility, and paranoia associated with dementia. Because these drugs can have many side effects, especially in the elderly, patients need to be closely monitored. Minor tranquilizers may also be used to treat symptoms of agitation and anxiety. Antidepressants such as citalopram (Celexa) or duloxetine (Cymbalta) may be used if depression coexists with dementia. These drugs may improve appetite and sleep habits, enhance socialization, and increase energy levels. Hypnotics, antianxiety drugs, and anticonvulsants may also be helpful.

Family Support.: It is very important to provide emotional and social support to the patient with dementia, as well as to significant others. As caregivers, the entire family often experiences changes in lifestyle, privacy, and socialization. It is not unusual for the caregiver to experience physical and mental exhaustion from providing round-the-clock care.

Adjusting to the reality that dementia is a chronic, nonreversible condition that may result in a lingering death can be very difficult. This places families in a situation of dealing with grief over a long period of time.

Acceptance of a relative with dementia by a loved one depends on personal coping strategies, support, and past experiences. Adjustment can be enhanced by integrating the care of the family into the nursing care plan. Family members will need ongoing support by the entire health care team. They may need an explanation regarding the disease or condition to help them better cope with the days ahead.

Financial problems and multiple role responsibilities add to the burden of caregiving by the spouse or adult children. Caregivers are also subject to loneliness, depression, and social isolation. An assessment of the caregiver’s health and functional status, nutrition, and exercise patterns can allow for developing strategies to help families cope more effectively as caregivers. Caregivers may need to be encouraged to take time out and attend to their own well-being.

Nurses can encourage families to consider adult day services or respite care if the elder resides at home. These types of care can provide for much-needed psychological and physical rest for the caregivers. Families may need guidance in locating resources to explore. Referrals may include health care professionals, community mental health centers, area agencies on aging, or support groups for specific diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Social implications for the resident in long-term care whose abilities continue to deteriorate relate to maintaining interactions with others for as long as possible. It is important to realize the family will continue to require support from the health care team at this time.

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia (70%) in the elderly, and is the fourth leading cause of death in this population. With the graying of America, this disorder may pose a significant public health concern in this new millennium.

The loss of neurons in the frontal and temporal lobes accounts for the AD patient’s inability to process and integrate new information as well as retrieve memory. Although there are many diagnostic tools to rule out some cognitive diseases, few can diagnose AD. Positron emission tomography (PET) has shown reduced lobe activity early in the disease. However, conclusive evidence can be found only at autopsy.

AD has three stages: early, middle, and late. Box 41-4 shows the common behavioral manifestations associated with each stage.

Treatment and Nursing Interventions for Alzheimer’s Disease

Treatment is primarily symptomatic. Four cholinesterase inhibitor drugs–tacrine (Cognex), donepezil(Aricept), galantamine (Reminyl), and rivastigmine, (Exelon) produce modest benefits early in the disease by improving memory, alertness, and social engagement. These drugs work by increasing acetylcholine in the cerebral cortex. Cognex is associated with liver toxicity and must be monitored closely. Aricept is administered once a day, and causes less liver toxicity. Memantine (Namenda), a drug developed in Germany and approved in the United States in 2004, is the first treatment option for moderate to severe AD symptoms. Several new drugs are under development for AD, including nerve growth factor drugs.

Other medications found to enhance cognitive functioning, improve behavioral problems, or delay the effects of the disease include estrogen, vitamin E, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), folic acid, and possibly, the cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. General nursing interventions for AD patients depend on the stage of illness. In the early and middle stages, nursing care for a confused patient as previously discussed is necessary. The end of the middle stage, as well as the last stage, requires primarily supportive care measures. Box 41-5 lists some North American Nursing Diagnosis Association–International (NANDA-I) nursing diagnoses that are appropriate for the cognitively impaired older patient.

SAFETY FOR THE COGNITIVELY IMPAIRED

When a senior is cognitively impaired, home safety becomes an issue. When impairment is very mild, the patient may be able to stay in his own home safely. Otherwise, there must be adjustments to the living situation. When a person with dementia goes to live with relatives, there should be alerting systems attached to outside doors to prevent the person from wandering out by himself. Identification should be sewn into clothes and placed in a wallet or purse. An identification bracelet that is not easily removed is helpful if wandering occurs. Measures need to be taken to alert the household if the person leaves the bedroom area at night so that the stove is not used without supervision. Sometimes a residential placement is needed. Options include an assisted-living facility, a board-and-care facility, or a long-term care facility.

If the person still owns a car, driving becomes another safety issue. No one wants to give up independence. Families have great difficulty getting a senior to give up driving. One helpful way is to suggest that a family member take the person wherever he wants to go for a month so that it becomes apparent that giving up the car doesn’t mean staying at home. Another option is to research what alternative transportation is available and have a family member accompany the person the first couple of times that transportation is used. If that works well, then it can be pointed out that the person doesn’t need to drive anymore to maintain his present lifestyle and independence. Another method is to see if the person will consent to having an outside evaluation by a driver’s education firm to determine safe driving capability. Of course, the person should only drive if confusion about direction is not an issue. Helpful information is available in the American Medical Association guide, Physician’s Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers, available at www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/10791.html. There are driver rehabilitation specialists that can help sharpen driving skills. Information is available at www.driver-ed.org.

BEHAVIORS ASSOCIATED WITH COGNITIVE DISORDERS

Violent behavior in the elderly may be the result of a lifelong psychological pattern, an organic condition, or an adverse reaction to multiple medications. Aggressive behavior may also occur as a self-protective response to confusion, fear, or sensory loss. Frequently it is associated with delirium, AD, other dementias, stroke, metabolic disorders, and hypoxia.

Preventing agitation and managing it can be accomplished by watching carefully for signs of this behavior. Some patients will show signs of increasing irritability before a severe problem occurs. Others may have sudden, explosive outbreaks. Notice if patients are talking very loudly, pacing more or faster, or making threats. Before an actual outburst occurs, try to keep the patient engaged in conversation, using some of the therapeutic communication skills discussed in Chapter 8. If seeing reflections in a mirror causes agitation, cover or remove the mirrors.

Matching the tone of the patient’s voice may be calming. It may be advisable to step back 4 to 6 feet while conversing. With a disoriented patient or if a sensory deficit is present, you may want to approach more closely to maintain eye contact and touch. This must be done cautiously to protect the safety of everyone. Move other patients or visitors out of the way as necessary.

Behavior modification is also an intervention used to change agitated behavior by giving positive feedback for desired behaviors and negative feedback for undesired behaviors. Distraction may be used for the elder not favorably responding to behavior modification.

If a patient becomes violent, you must remember to protect the patient from his own behavior. You need to call for help and, as a team member, decide what intervention will be most helpful.

Points to consider for intervention are the patient’s right to the least restrictive treatment and the federal and state regulations regarding the use of chemical (medication) and physical protective devices. Before giving medications, it is necessary to try behavioral approaches and document their effectiveness. When all else fails and the patient poses a threat to his well-being or others, protective devices may be necessary.

Paranoia can also be caused by dementia as well as psychological conditions such as schizophrenia. Patients with paranoia may misinterpret their environment and believe others are untrustworthy and out to get them. These patients may sound very convincing and logical in their suspicious behaviors.

For the patient with paranoia, developing trust is the most important thing to accomplish. Being consistent and reliable is perhaps the best way to develop trust in the relationship with the paranoid patient. Do not make promises you cannot keep. If you say you will do something, follow up with it. It is of utmost importance not to put any medication in a drink or food without the patient’s knowledge so that trust is not broken.

Wandering

Wandering may be a problem for the patient affected with a cognitive disorder. Wanderers tend to be individuals who were very active people prior to the onset of disease. For some, wandering may be goal directed, such as looking for the bathroom. For others, it may be a need to combat boredom or restlessness. Nursing interventions might include ensuring the environment is safe for wandering, informing/educating others about this problem, making sure the patient has an identification bracelet, frequently checking the patient, observing for behaviors that trigger the wandering, diverting his attention, and maintaining a regular activity program. Many units are designed for wandering patients and may even include gated outside areas in which to commune with nature.

Sundown Syndrome

To alleviate the confusion and fears associated with sundowning, it is important for you to help the patient feel safe in his environment. The use of a night-light, placing the call bell within reach, reducing stimulation in the environment, and moving the patient closer to the nurses’ station can help minimize nocturnal confusion (Box 41-6). Protective devices should be used as a last-resort safety measure because they may add to the patient’s anxiety.

Eating Problems

Adequate nutrition often becomes a problem for the patient with dementia. Common feeding challenges include lack of appetite, refusal to open the mouth, holding food in the mouth, refusal to swallow food, and choking when swallowing. Nutritional Therapies 41-1 lists strategies to overcome such problems.

DEPRESSION/ALCOHOLISM/SUICIDE

Depression (feelings of sadness, despair, or discouragement) in the elderly is often overlooked and untreated. It is the most common functional mental illness in the elderly. As noted in Table 41-1, it can often be mistaken for delirium or dementia.

Depression is often difficult to recognize because symptoms may be attributed to the aging process. Instead of complaining of a depressed mood, the elderly may complain of anorexia, sleep disturbances, lack of energy, and loss of interest and enjoyment in life. Depression in the elderly occurs to a great degree as a result of situational factors such as multiple losses. It is helpful to assess the elderly patient’s mood periodically (Box 41-7). Undiagnosed and untreated, depression is a major contributor to alcoholism and suicide in the elderly. Focused Assessment 41-1 lists common characteristics of depression to assess in the elderly.

Alcohol abuse, suicide, and depression are interrelated in that they each have similar risk factors associated with multiple loss. Loss of status/power, income, spouse, friends, and health contribute to feelings of despair and hopelessness. The elder’s outlook on life is distorted, preventing him from exploring acceptable solutions to his problems.

Alcohol misuse is a serious concern because it can interfere with the management of chronic diseases and heighten the risk of adverse drug reactions due to diminishing liver and kidney function. Alcoholism is often overlooked because so many elder problem drinkers are retired and hidden at home. Clues to alcoholism include depression, insomnia, mental confusion, frequent falls, self-neglect, and uncontrollable hypertension or diabetes, as well as gastritis and anemia.

INTERVENTIONS FOR DEPRESSION, ALCOHOLISM, AND SUICIDE PREVENTION

Patients who are depressed are usually treated with both psychotherapy and antidepressants (Complementary & Alternative Therapies 41-1). Hospitalization may be necessary if the patient is at high risk of suicide.

The three main categories of medications used to treat depression are (1) the tricyclic antidepressants, such as amoxapine (Asendin) and amitriptyline hydrochloride (Elavil); (2) the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), such as phenelzine sulfate (Nardil); and (3) the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine hydrochloride (Prozac), sertraline hydrochloride (Zoloft), paroxetine hydrochloride (Paxil), citalopram (Celexa), duloxetine (Cymbalta), and venlafaxine hydrochloride (Effexor).

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a treatment option for those patients who have severe forms of depression and who have failed to respond to several regimens of medication. ECT consists of electric shock to the brain via electrodes attached to the patient’s temples, producing tonic-clonic seizures. How this mechanism is effective is not clearly understood. The patient usually receives two or three treatments per week for several weeks.

The primary nursing responsibility for a depressed patient is to protect him from self-injury, especially after the patient has initiated antidepressant therapy. Prior to that time, he may not have had the energy to commit suicide.

It may be difficult to communicate with a depressed patient because of his negative thoughts and behaviors. Genuine concern for the patient is essential. You will need to help him set realistic, achievable goals. Start with small goals such as grooming and slowly work toward larger goals. Remember that goal setting and problem solving take concentration and energy that may not be available to the person who is still somewhat depressed. Providing a quiet environment conducive to sleep can help restore energy for individuals who complain of sleep deprivation.

Caregivers need to be alert to signs of potential suicide such as meticulous planning of personal affairs, giving away treasured possessions, sudden euphoria, or statements of death wishes. Assisting the patient to promote self-esteem and meaningful activities may resolve the intent of suicide. It is important for you to build a trusting relationship with the suicidal patient to let him know you care. Spending time with your patient and active listening are very important in showing your concern.

Referrals for outpatient counseling or immediate crisis intervention may be necessary to deter suicidal thoughts or tendencies. However, as with any individual who believes suicide is the only answer, the elder may eventually carry out this act. Thus caregivers and family would need support and possible counseling to resolve their grief.

During patient interviews, health professionals need to assess the use of alcohol by depressed elders. Making the diagnosis of alcohol dependency is not necessarily difficult, but unless there is self-admission of a problem, long-term recovery is unlikely. Initial treatment may consist of detoxification and stabilization of the patient with chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride (Librium). Once the patient is stable, therapy may consist of group or behavioral therapy. Individual therapy may also be instituted for the depressed, alcoholic elder.

Patient and family teaching must include information about the effects of alcohol on medications and on chronic health conditions. Referral to a 12-step program such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) for the patient, and Al-Anon for family members, can also be a beneficial part of treatment.

CRIMES AGAINST THE ELDERLY

Abuse is defined as the intentional infliction of physical or emotional discomfort or the deprivation of basic needs necessary for comfort or survival. It is estimated that only 1 in 14 cases of elder abuse is reported.

Elder abuse is most often inflicted by a spouse or adult children in the home, and is often undetected. It is often related to caregiver stress, unresolved family conflicts, or families with a history of abuse. All forms of abuse are destructive, and at the very least reduce the victim’s self-esteem. Box 41-8 identifies the five different categories of abuse.

Responsibilities of the nurse include identifying those at risk. Assessment of signs and symptoms of suspected elder abuse is described in Focused Assessment 41-2. During assessment of potential abuse, avoid a condescending tone of voice or judgmental expression. The establishment of a confidential, trusting relationship is necessary. Be sure to show a willingness to listen also to the caregiver’s perspective. Assess the caregiver’s early memories of relationships with the elder to learn of possible long-term conflicts.

You have a legal obligation to report elder abuse and are accorded protection from civil and criminal liability in most states that mandate reporting suspected abuse (Jech, 2002). Evidence of suspected abuse should be reported immediately to the appropriate agency for investigation. The standard for reporting is usually a reasonable belief that an individual has been or is likely to be abused, neglected, or exploited.

Be aware that advocacy for the abused may be difficult because you may receive threats from those who resent your involvement. A common frustrating situation is the competent elder with full legal rights who refuses help or desires to remain in an environment that is unsafe or unacceptable. In this case, the health care team must honor the decision after providing counseling about potential dangers. If a person is legally incompetent, steps need to be taken for appropriate guardianship. Testifying in court about an abusive situation can be very stressful for all who are involved.

Individual and/or group psychotherapy is often used to treat both victims and abusers. The victim should be removed from the home before entering treatment to avoid retaliation. Intensive psychotherapy may be necessary for the abuser with psychopathology. Support groups are also available for both victims and abusers. Long-term follow-up is essential to prevent further abuse.

SCAMS/WHITE–COLLAR CRIME

Crime is of particular concern to the elderly because of their sense of vulnerability. Older adults do not suffer any greater physical injury or financial loss than younger people; however, the effects of crime, such as fear, isolation, loneliness, and feelings of powerlessness, may be more detrimental. Location and income are often more significant than age in predicting crime. Some of the various crimes against older adults are listed in Box 41-9.

Nurses can be instrumental in reducing fear of crime and assisting elders in exploring security-conscious behaviors that will decrease vulnerability to victimization (Patient Teaching 41-1).

Nurses also need to learn about referral programs in crime protection, prevention, and victim assistance. Federal programs through the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, the Office of Community Victim Assistance, the Community Services Administration, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development offer crime prevention and victim counseling. State offices of aging and organizations such as the AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons) have also proved beneficial in enhancing awareness of crime prevention.

FUTURE ISSUES OF CONCERN TO THE ELDERLY

It is not easy to predict what the future will bring, but the best word for the older-aged population may be increasing, in both number and age. The elderly will be the fastest growing segment of the population and will have the greatest effect on the delivery of health care. Older adults of the 21st century will be better educated, more involved in community and political activities, and more knowledgeable consumers of health care.

What will be the priorities in the future? How much funding will go toward research of life-threatening diseases of the elderly versus solving environmental problems that affect all populations? With the nation’s long list of priorities, what decisions will be made?

PLANNING FOR THE FUTURE

Expanding present services and developing new delivery systems will be challenges for the future. Safe housing and efficient mass transportation to stores and recreational facilities will continue to be needed, as well as one-stop-shopping senior centers. This concept can allow for the arrangement of multiple services such as home-delivered meals and chore services at a nominal cost, which can make a difference as to whether a person can remain at home or must be institutionalized.

Planning for the future will need to include lifelong learning opportunities that assist the elder with maintaining wellness, preparing for retirement and leisure time, financial planning, and advances in technology. Other considerations are job training and retraining for “early retirees” who wish to remain employed. Health issues to be addressed need to include the rapidly rising rate of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the elderly and the health problems specific to the growing proportion of elderly women.

Healthy People 2010 is a federal campaign designed to encourage people to adopt healthy lifestyles to maintain or improve their health. Emphasis is on health promotion, protection, and prevention. State and local governments, the AARP, and business and local industry have been working together since 1990 to achieve the following goal: “Increase the years of healthy life remaining after age 65.” New goals have been devised for 2010 that include more objectives that specifically address elders.

Will the programs and services discussed become realities? The answer lies partially with the elderly of today. Individuals over 65 form a powerful political group with real voting power that can effectively make change happen. Combined with the advocacy of nursing power to access necessary resources, the new goals of Healthy People 2010 can realistically be achieved.

NCLEX-PN® EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Choose the best answer(s) for each question.

1. When it comes to learning, the elderly are:

1. equally capable as younger persons, but slower to learn.

2. less able to learn than younger people.

3. able to learn equally with younger people.

4. about a third less efficient at learning as a younger person.

2. Confusion is often a reversible condition in patients with:

3. Measures to keep the cognitively impaired elder safe in a home environment include: (Select all that apply.)

1. placing alarms on the outside doors.

2. removing knobs from the stove burners and oven at night.

3. having the person carry a cell phone at all times.

4. Which symptoms is the nurse most likely to observe in a depressed, elderly patient? (Select all that apply.)

5. Medications that work by increasing acetylcholine in the cerebral cortex may produce:

1. a calming effect and less hostility.

2. better ability to organize and carry out tasks.

6. Which strategies are the most helpful in managing sundowning? (Select all that apply.)

1. Keeping lights very low after dark.

2. Keeping a nonstimulating environment in the afternoon and evening.

3. Diverting the person’s attention.

4. Playing soft music in the late afternoon and evening hours.

7. When you suspect an elder is considering suicide, the most appropriate intervention is to:

1. discuss suspicions with a significant other.

2. ask the patient directly about such plans.

8. The usual standard for reporting elder abuse is one:

9. Long-term recovery from alcohol abuse is most likely to occur when:

10. Strategies to help prevent crime include: (Select all that apply.)