Communication and the Nurse-Patient Relationship

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Describe the components of the communication process.

2 List three factors that influence the way a person communicates.

3 Compare effective communication techniques with blocks to communication.

4 Describe the difference between a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship and a social relationship.

5 Discuss the importance of communication in the collaborative process.

6 List three guidelines for effective communication with a physician by telephone.

7 Identify four ways to delegate effectively.

8 Discuss five ways in which the computer is used for communication within the health care agency.

1 Use interviewing skills to obtain an admission history from a patient.

2 Interact therapeutically in a goal-directed situation with a patient.

3 Communicate effectively with a patient who has an impairment of communication.

4 Give an effective report on assigned patients to your team leader or charge nurse.

active listening (p. 105)

aphasia ( , p. 113)

, p. 113)

body language (p. 104)

communication ( , p. 104)

, p. 104)

confidentiality ( , p. 112)

, p. 112)

congruent ( , p. 104)

, p. 104)

delegate ( , p. 116)

, p. 116)

empathy ( , p. 112)

, p. 112)

feedback (p. 105)

incongruent ( , p. 106)

, p. 106)

input (p. 116)

nonverbal ( , p. 104)

, p. 104)

perception ( , p. 105)

, p. 105)

rapport ( , p. 111)

, p. 111)

SBAR (p. 115)

shift report (p. 114)

therapeutic ( , p. 108)

, p. 108)

therapeutic communication (p. 107)

verbal ( , p. 104)

, p. 104)

THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

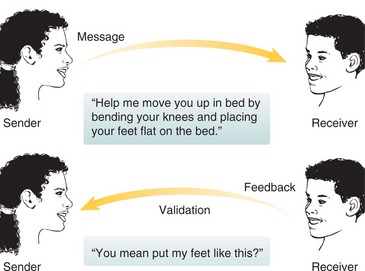

Communication occurs when one person sends a message to another person who receives it, processes it, and indicates that the message has been interpreted (Figure 8-1). The receiver must acknowledge that the message has been received and comprehended for the communication to be complete. By its nature, communication is a continuous, circular process and occurs in two ways, verbal (in words) and nonverbal (without words). Verbal communication consists of words either spoken or written. Nonverbal communication is conveyed without words by gesture, expression, body posture, intonation, and general appearance. Nonverbal communication is often referred to as body language. Nonverbal communication conveys more of what a person feels, thinks, and means than what is actually stated in words (Figure 8-2). Sometimes the person’s nonverbal communication is not congruent (in agreement) with the verbal communication. If you state that you want to sit and talk for a while and then sit with legs crossed and a foot bouncing rapidly during the conversation, the message is one of impatience rather than attentive listening.

FIGURE 8-2 Nonverbal communication signals that the nurse is interested in the patient and what she is saying.

You can learn more about patients by observing nonverbal behavior. Anxiety, fear, and pain are often expressed by nonverbal cues. Wincing when turning, a pinched expression, or nervously picking at the bed covers may indicate what patients are really feeling, although they say they are fine. Experience will increase your ability to assess nonverbal communication. Rigid body posture or slow movements often indicate pain. Restless movements may indicate anxiety. Validate perception (recognition and interpretation of sensory stimuli) of nonverbal communication with the patient. This can be done by asking about feelings and thoughts. For, example, “Mrs. Lopez, you seem a little restless [and anxious] today. Would you like to talk about something?”

Good communication requires active listening (mind and senses are focused on what is being said), timely feedback (responding), and validation of assumptions about nonverbal cues.

FACTORS AFFECTING COMMUNICATION

Culture, past experience, emotions, mood, attitude, perceptions of the individual, and self-concept all contribute to the way people communicate. Every culture has norms for appropriate communication. The norms include the distance between communicators, whether eye contact should be established, the tone of voice, and the amount of gestures used.

Cultural Differences

Individuals differ in the amount of personal space they need between them and the person with whom they are speaking. In the United States, 18 inches to 4 feet is the amount of distance that individuals place between themselves and a new acquaintance. This distance is called personal space. The distance lessens when people converse with someone with whom they are intimate. When people are not acquainted, they maintain a social distance of 4 to 12 feet if they have a choice. In general, American Indians, northern Europeans, and Asians maintain more distance from others than do Hispanic, southern European, or Middle Eastern people. Cultural Cues 8-1 presents cultural considerations of making eye contact during communication.

Past Experience

All of our experiences affect how we perceive what is communicated to us. Interpretation of messages is influenced by cultural values, level of education, familiarity with the topic, occupation, and type of previous life experiences.

Emotions and Mood

Emotions and mood can drastically affect the way messages are sent or interpreted. A highly anxious person may not correctly hear what is said, or may interpret the message totally differently than the sender intended. A depressed person tends to use few words. A person who is upset or stressed may speak in a loud, harsh tone or be more abrupt than usual.

Attitude

A person’s attitude affects how a message is worded and the body language that accompanies it. When your attitude is one of acceptance of the patient, caring and concern are displayed by open, attentive body language. If you disapprove of the patient’s behavior, you may use a closed body stance and stern expression and be somewhat distant during interactions. Someone with an accepting attitude will make an effort to understand what a person is trying to convey during the communication.

You should try to be open and attentive to patients’ communications, to maintain a nonjudgmental attitude, and to remember not to take personally the unpleasant things a patient might say when upset or frightened.

COMMUNICATION SKILLS

Some people are more effective communicators than others. Effective communication can be learned by improving basic communication skills.

Active Listening

Active listening requires great concentration and focused energy. All the senses are used to interpret verbal and nonverbal messages, attention is on what the speaker is saying, and the mind is focused on the interaction. Listen for feelings as well as words. It takes practice to tune out other thoughts that try to intrude and not to start formulating a response until the speaker is finished. When you are an active listener, you demonstrate interest in the patient, and a trusting relationship can be built. An active listener maintains eye contact without staring, gives the patient full attention, and makes a conscious effort to block out other sounds and distractions. The active listener does not interrupt the speaker and waits for the full message before interpreting what is said. Responding to the content and feelings of the message by stating what you, as the listener, understand was said by the patient completes the process. Nonverbal cues that indicate active listening are leaning forward, focusing on the speaker’s face, nodding slightly to indicate the message is being heard, and maintaining an open body posture.

Interpreting Nonverbal Messages

The speaker’s posture, gestures, tone, facial expression, and eye movements should be observed. A smile or frown, hunched-down posture, or hand-wringing all express feelings. When taking in nonverbal messages, it is important to remember that they must be interpreted in the context of the speaker’s culture, not the listener’s. The listener must decide if the nonverbal messages are congruent with the spoken message. Mixed messages, in which the words do not fit the nonverbal indications, leave an uneasy feeling about an interaction. When the verbal and nonverbal messages are incongruent (do not agree), the listener should explore what the speaker really desires to communicate.

Obtaining Feedback

A vital part of communication is checking to see if you interpreted a message in the way the speaker meant it. This can be accomplished by rephrasing the meaning of the message or directly asking a feedback question, such as “Is your headache severe?” “Are you uncertain about having this surgery?” or “Does the idea of having anesthesia scare you?” The response received from the question should verify whether the original message sent was interpreted correctly.

Focusing

Keeping attention focused on the communication task at hand can save time. The effective communicator refocuses the other person gently to the issue at hand when the focus has wandered. Occasionally the approach, “We’ll come back to that later, but right now I need to know…” will quickly refocus the communication. At other times, commenting “I think we were talking about…” is what is needed.

Adjusting Style

The patient’s style and level of usual communication should be considered when interacting. If the person is a slow, calm communicator, adjust to that pace. If a response is slow in coming, allow plenty of time for consideration and a response; try not to display impatience. If it is comfortable for the patient to display feelings only in the context of telling a story about a related topic, allow enough time for full development of the topic so that the feelings can be adequately expressed (Cultural Cues 8-2).

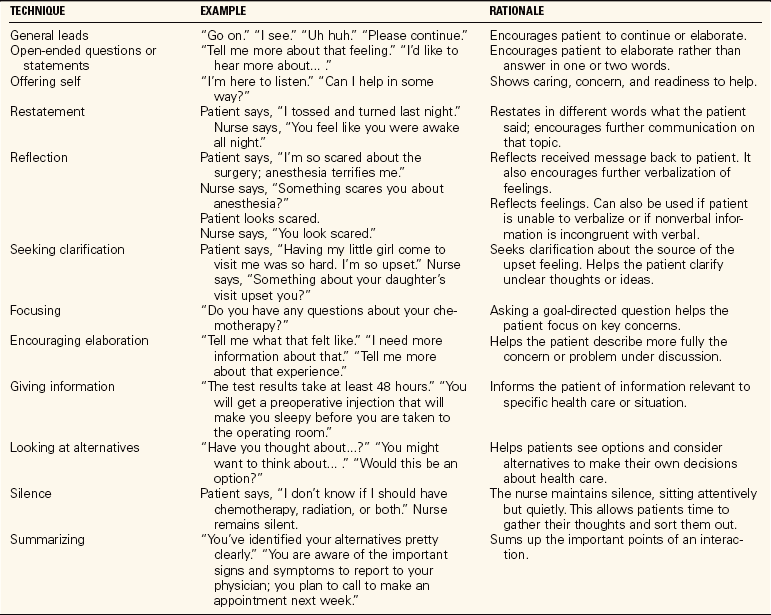

THERAPEUTIC COMMUNICATION TECHNIQUES

Therapeutic communication (communication that is focused on the needs of the patient) promotes understanding between the sender and the receiver. There are various phrases or cues that may be used to promote such understanding or facilitate an interaction between a patient and the nurse. These techniques should be used judiciously and in a varied manner or the interaction will feel stilted and uncomfortable. Common therapeutic communication techniques are presented in Table 8-1.

SILENCE

Appropriate use of silence is one of the hardest techniques for most students to develop. The new nurse is often uncomfortable with silence, and so tends to be too quick to end it. Silence gives the patient time to think and respond. When the nurse remains attentive and uses body language indicating patience and interest, the patient is encouraged to verbalize feelings or thoughts.

OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONS

An open-ended question is broad, indicating only the topic, and it requires an answer of more than a word or two. Use of an open-ended question or statement allows the patient to elaborate on a subject or to choose aspects of the subject to be discussed. Open-ended questions or statements are helpful to open up the conversation or to proceed to a new topic. They usually cannot be answered with one word or just “yes” or “no.” “Tell me about your day” versus “Did you have a good day?” or “How did you sleep?” versus “Did you sleep well?” are examples of open-ended versus closed questions. The closed question forces the listener to stick directly to the topic and to be concise. Open-ended questions create an inviting atmosphere for sharing thoughts, feelings, and concerns.

RESTATING

You listen for the basic message the patient is conveying and then rephrase the heart of the message. If the patient states, “My son hasn’t been to see me in months,” responses that restate the thought in different words might be as follows: “Your son hasn’t been around much lately,” or “You miss your son’s visits.” Restating is used to encourage the patient to continue with information on a topic.

Reflection is another way to restate the message. The same words the patient has said are reflected back. A patient says, “I’m worried about cancer,” and the nurse replies, “You are worried about cancer.” The idea is simply reflected back to the speaker in a statement to encourage continued dialogue on the topic. Restating and reflection should be used sparingly and skillfully. If overused, the patient will quickly recognize that you are repeatedly saying her words back to her; you do not want to sound like a parrot or an automaton. Patients tend to find that annoying.

CLARIFYING

Clarifying helps verify that the message heard is what the patient intended. It is particularly useful when the dialogue has rambled. If a patient says that family members visited and that they all sat around and drank coffee, and then says that sleeping was difficult last night, the nurse might say, “Are you saying that the coffee kept you awake?” This asks for confirmation that it was the caffeine in the coffee that prevented sleep, and not a problem brought in by the family that might have caused the sleeplessness.

TOUCH

Gentle touch that indicates caring is therapeutic (effective or curative). It may be used to signify support for the person or when appropriate words are hard to find. Touch must be used judiciously, taking into consideration the patient’s cultural and personal feelings about being touched by a stranger. You should have verbal or implied permission from the patient for touch to occur. Messages accompanied by touch can add a feeling of caring and comfort. Touching the patient warmly on the shoulder and saying, “I’m glad the medicine has relieved your pain” indicates that you really care. Touch needs to be beneficial for the patient; it should not be done to meet a need of the nurse. The nurse must consider how the patient will perceive and interpret touching before caring is expressed in this manner. Cultural Cues 8-3 presents additionally information about how to use touch with patients from different cultures.

GENERAL LEADS

General leads or broad openings are used to get the interaction under way. If a patient says, “I feel so guilty for breaking my leg,” a general lead would be “Tell me more about that.” A general lead that is useful first thing in the morning is “Tell me how your night was.” General leads are statements or questions that cannot be answered with a “yes” or “no” and require more than a few words in response. “Perhaps you’d like to talk about your chemotherapy,” “I noticed the doctor came after I left yesterday; perhaps you’d like to talk about what he said,” and “I hear you are being discharged today; what do you think about that?” are other examples.

OFFERING OF SELF

Being available to the patient is one way of offering yourself. Answering call lights quickly or checking on something right away states that you are available to the patient, but this is not always possible. Letting the patient know when you will return or when you will be able to get the desired information conveys availability. Fulfilling such promises to obtain information or return at a particular time helps establish trust. Another form of offering yourself is to tell the patient, “I’ll just sit here with you for a while,” and then remain with the patient.

ENCOURAGING ELABORATION

Statements such as “You said you have had a difficult time with pain these last few months” or “Tell me more about that” encourage the patient to share feelings about what has been happening. “I’m not certain that I follow what you mean” is another way to encourage the patient to continue. Encouraging elaboration is used to elicit further information about a topic. This technique might be used rather than restatement or reflection.

GIVING INFORMATION

Nurses must give patients information about medications, procedures, diagnostic tests, and self-care. Giving information concisely and allowing time for questions is therapeutic for the patient. Pay attention to nonverbal signals and ask for feedback to verify that the patient has understood the information given.

LOOKING AT ALTERNATIVES

Nurses help patients solve problems. To accomplish this, they are sometimes directive in assisting the patient to look at alternative solutions to a problem. Some helpful leads for this purpose are “You might think about…,” “Have you thought of your options?” or “What do you think are possible solutions?” The focus is on assisting patients to look at things from their point of view while you refrain from giving advice.

SUMMARIZING

Summarizing what has occurred during the interaction is helpful. A summary of alternative solutions to a problem, decisions made, plans for action, or feelings that have been expressed provides closure to the interaction. “You’ve indicated that you have a choice between undergoing surgery and trying medication for your problem. We’ve discussed the potential side effects and benefits of both treatments, and now you want some time to think about it” would be a summarizing statement.

BLOCKS TO EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION

Just as there are phrases and cues that encourage effective communication, there are phrases that tend to block or terminate interaction. Table 8-2 summarizes blocks to effective communication.

Table 8-2

Blocks to Effective Communication

| TECHNIQUE | EXAMPLE | RATIONALE |

| Changing the subject | Patient says, “I’m so worried about my husband.” Nurse says, “It is time for your bath now.” | Deprives the patient of the chance to verbalize concerns. |

| Giving false reassurance | “I’m sure it will turn out fine.” “You don’t need to worry.” | Negates the patient’s feelings and may give false hope, which, when things turn out differently, can destroy trust in the nurse. |

| Judgmental response | “I don’t think that was a good thing for you to do considering you have diabetes.” | Nurse is judging the patient’s action. Implies that the patient must take on the nurse’s values and is demeaning to the patient. |

| Defensive response | Patient says, “My doctor never seems to know what is going on.” Nurse says, “Dr. Smith is a very good doctor; he’s here every day.” | Nurse responds by defending the doctor. Prevents patients from feeling that they are free to express their feelings. |

| Asking probing questions | “Why were you there at that hour?” “What did you intend to prove?” | Pries into the patient’s motives and therefore invades privacy. |

| Using clichés | “Cheer up, you’ll be home soon.” “This won’t hurt for long.” “You have a long life ahead of you.” | Negates the patient’s individual situation; stereotypes the patient. This type of response sounds flippant and prevents the building of trust between patient and nurse. |

| Giving advice | “If I were you, I would….” “I think you should….” “Why don’t you….” | Tends to be controlling and diminishes patients’ responsibility for taking charge of their own health. |

| Inattentive listening | Turning your back when the patient is sharing feelings or pertinent information; showing impatience with body language (i.e., tapping your foot or having your hand on the door to go out). | Indicates that the patient is not important, that the nurse is bored, or that what is being said does not matter. |

CHANGING THE SUBJECT

When a patient is speaking and you change the subject, it indicates that there is discomfort, disinterest, or anxiety on your part. There is avoidance of listening to a patient’s pain, distress, fear, or perception of problems. If you change the subject in an effort to keep the patient’s thoughts off unpleasant things, you deny the patient’s desire to express feelings. Sometimes the patient will talk about an experience that is similar to something that happened to you. It is tempting to relate your experience, directing the conversation away from the patient. Students often make this mistake. Over time, you’ll learn to consider whether the information is of real value to the patient before sharing your personal experiences.

OFFERING FALSE REASSURANCE

Giving reassurance not based on fact is damaging because it discounts the patient’s concerns and destroys trust. Saying “Don’t worry; everything is going to be fine” when a patient has valid concerns indicates a lack of understanding. The nurse who tells a woman who has just had breast surgery that she should not think that her husband will find her scar distasteful because she is “still a beautiful woman” is offering inappropriate reassurance about someone else’s feelings. This type of comment conveys the message that you do not care about the patient’s fears and feelings about her new body image and jeopardizes the professional relationship. Reassurance should be based on fact. Informing a patient that there will be some discomfort after a diagnostic procedure but that analgesic medication will be available to relieve that discomfort is much better than saying that it is a simple procedure and not to worry. A realistic approach helps maintain trust.

GIVING ADVICE

Giving advice is another area that prevents many novice nurses from being more therapeutic. Giving advice places the focus on the nurse rather than the patient. Also, many patients often think that they must do what you say because you are the authority figure. Your role is to guide patients to alternative choices for solving their own problems.

DEFENSIVE COMMENTS

Becoming defensive when a patient has a complaint interferes with effective communication. If a patient complains that the call light is not promptly answered in the evenings and you state, “You should realize how short-staffed we are in the evenings,” the patient is denied the right to a valid view and complaint. By taking a position opposite to the patient’s point of view, you take on the role of adversary rather than helper. Acknowledge the patient’s feelings by saying something like, “It’s upsetting when no one can get here promptly.”

PRYING OR PROBING QUESTIONS

Probing questions may place the patient on the defensive. This occurs when you ask questions about the patient’s private business, and these questions have no relation to the treatment or clinical condition. Questioning why the patient did or did not do a particular thing makes the patient defensive about the action and may cause feelings of discomfort. If you ask a patient who has been injured in an automobile accident, “Why were you driving so fast in the rain?,” you are inappropriately probing.

USING CLICHÉS

A cliché is an overused expression that may have no real relation to the current situation. Comments such as “You’ll be fine,” “Don’t worry, it will turn out OK,” or “There will be a light at the end of the tunnel” are clichés. They show a lack of respect for the patient as an individual. These comments discount what the particular patient might feel. If you use clichés, patients will feel that their individual situations are not being addressed. It is better to express that you are available to listen to the patient’s concerns and feelings and to be supportive as needed.

INATTENTIVE LISTENING

Failing to really listen to what the patient has to say is a block to communication. If you continue to straighten the room and turn away while the patient is trying to express feelings or something of importance, your actions express to the patient that you are not interested. Interrupting or jumping in before the patient has finished speaking also indicates inattentive listening. Frequently changing the subject or focusing the conversation away from the patient’s concerns expresses that you are not interested in listening.

INTERVIEWING SKILLS

An interview is more directed than a therapeutic communication interaction. It is planned and has a definite purpose. It is important to establish rapport (a relationship of mutual trust or affinity) with the patient before beginning an interview (Communication Cues 8-1). Introduce yourself and ask how the patient wishes to be addressed. Include the family in your greeting. Explain the purpose of the interview and provide privacy. Ask patients if they wish their family or friends to remain during the interview by saying, “Would it be better if we are alone for this interview?” Eliminate excess noise by turning off the television or radio. Be certain that the patient is comfortable, draw up a chair to within 3 to 4 feet, and sit down facing the patient (Figure 8-3). Chapter 5 contains more information about the interview.

For an admission interview in which a health history is to be obtained, take control of the interaction and initially ask closed questions that call for specific data. This type of direct interview does not allow the patient to ask questions or discuss concerns until all the necessary information has been collected. Examples of questions might include the following:

After taking the history, use open-ended questions to find out how the patient feels about the hospitalization. Examples of useful open-ended questions include “What brought you to the hospital?” “What are your concerns about this hospitalization?” and “Do you have any questions?” This last question indicates that the interview is coming to an end. A brief summary statement, ending with “I think I have the information I need,” closes the interview. Thank the patient for supplying the information collected before leaving the room. An example of the nursing admission history form is found in Chapter 5.

THE NURSE-PATIENT RELATIONSHIP

The nurse-patient relationship focuses on the patient, has goals, and is defined by specific boundaries. The relationship takes place in the health care setting, and boundaries are defined by the patient’s problems, the help needed, and the nurse’s professional role. When the patient is discharged, the relationship ends.

Good communication skills establish a therapeutic relationship between you and the patient that assists in the patient’s healing process. In this relationship, you are in a helper role rather than a social role. Interaction between you and the patient should build trust. Without trust, the patient will discount much of what you say.

A social relationship differs from a therapeutic one in that the focus is on both participants and the usual goal is to meet one’s own needs. The social relationship is established for mutual enjoyment, and there is considerable sharing of experiences, life events, and thoughts. Social relationships are terminated when one or the other person does not feel that the relationship meets perceived needs any longer.

Characteristics in the nurse that facilitate a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship include effective communication skills, the quality of empathy (ability to understand by seeing the situation from another’s perspective), a desire to help, honesty, a nonjudgmental attitude, genuineness, acceptance, and respect for the individual. Confidentiality on your part must be maintained for trust to endure. Confidentiality means keeping all information about a patient private and not discussing any patient information with those who are not involved in the patient’s care.

EMPATHY

Empathy is the ability to place oneself in another’s position. It involves being able to see situations through another person’s eyes and perceive them as that person does. If empathy is present, the other person’s feeling is understood. Empathy is different from sympathy. With sympathy, concern and perhaps sorrow are felt, indicating that the person is experiencing something difficult. Warmth, a nonjudgmental attitude, and a focus on the patient’s feelings are present when empathy is expressed. Be careful about saying “I know how you feel” or “I understand what you are going through” because no one can really know or feel what someone else is experiencing. State an interpretation of the patient’s feeling and then seek validation that the interpretation is accurate.

BECOMING NONJUDGMENTAL

Becoming nonjudgmental takes considerable practice and discipline and is directly related to the degree of empathy a person is capable of generating. It is far easier to accept people as they are if things can be truly seen through their eyes. Patients come from all kinds of backgrounds and have many different sets of values. To be nonjudgmental, you must look at the patient in reference to her values rather than your own.

Be genuine in what is said and done with patients because this helps establish trust. Try to keep promises. A statement such as “I’ll be back in 30 minutes” requires that you return to the room at the appointed time. Write down notes on information to be obtained for patients so that the task is not forgotten, and keep interactions focused on the patient. Personal revelations and anecdotes are out of place unless they directly apply to the patient’s problems and can be helpful.

MAINTAINING HOPE

Maintaining hope is an important part of the nurse-patient relationship. There is always hope, even if the direction of hope changes. The dying patient can hope for less pain, peace, a pleasant moment, and a good laugh. A patient with cancer can hope for a positive prognosis, a healing outcome from surgery or therapy, or emotional growth from the illness experience. The patient should be helped to establish realistic hopes, but even unrealistic hopes should not be totally dismissed. Hope is what helps a patient cope in a difficult situation.

Application of the Nursing Process

Assess the language ability of the patient during the first encounter. Consider the following questions when gathering data about the communication needs of the patient:

• Is English spoken and understood?

• Is the vocabulary level equivalent to that of the average person of this age, or will it be necessary to simplify language to achieve comprehension of communication?

• Does the patient have a neurologic impairment that causes problems with the comprehension of oral or written communication or with the ability to hear or speak?

• What cultural factors affect the way in which this patient is accustomed to interacting verbally?

• How much personal space does the person need in order not to feel threatened or intimidated?

• If the person is unable to speak but can communicate in writing, what provisions need to be made to accommodate this?

Patients who have problems with communication are given the nursing diagnosis of Impaired verbal communication. If the problem is related to difficulty with hearing, the nursing diagnosis of Disturbed sensory perception is used.

Besides writing individual expected outcomes, you must plan appropriate amounts of time with the patient for a communication interaction. An assessment interview should not take more than one-half hour. If thepatient has communication impairment, varying amounts of time will be needed for each interaction. When a patient does not speak English, plan ahead and try to locate an interpreter before beginning an interaction with the patient. If the patient has aphasia (difficulty expressing or understanding language), obtain the assistance of a speech therapist to determine methods that facilitate communication. A white erasable board is handy for those who can write (Figure 8-4).

There are some techniques that can be helpful when communicating with a patient who has aphasia as a result of neurologic damage from a stroke or head injury. The use of appropriate nonverbal gestures sometimes helps. Guidelines presented in Box 8-1 can assist you in communicating more effectively with the aphasic patient. (See Nursing Care Plan 8-1 on the Companion CD-ROM for care of the patient with impaired communication.)

NURSE-PATIENT COMMUNICATION

COMMUNICATING WITH THE HEARING-IMPAIRED PATIENT

When a patient is identified as being hearing impaired, determine how to interact with the patient to promote the best level of communication. If the patient has hearing aids, see that they are used, that the batteries are functioning, and that the device is turned on before trying to communicate. A hearing aid does not guarantee that the individual will hear really well. The following techniques promote comprehension for a hearing-impaired person:

• Speak very distinctly. Do not shout because this can distort speech and does not make the message any clearer.

• Speak slowly and keep the voice pitch at mid-range, neither low nor high.

• Get the person’s attention, making sure the person is aware that verbalization is going to take place.

• The best distance for speaking to a hearing-impaired person is 2½ to 4 feet. Face the person at eye level. If the person is seated, sit down or bend down. Never speak directly into the person’s ear. This can distort the message and hide all visual cues.

• Be aware of nonverbal communication. Facial expressions, gestures, and lip and body movements all give cues to the meaning of the message.

• Use short, simple sentences. If the patient does not appear to understand or responds inappropriately, rephrase the statement. Try to limit each sentence to one subject and one verb. Give the person time to respond to questions.

• Ask for rephrasing to make sure the patient has understood important information.

COMMUNICATING WITH THE ELDERLY

The elderly vary greatly in their communication abilities, interests, and capabilities. Healthy older adults sometimes require more time to think and formulate a response. Other older adults may have hearing, sensory, or motor impairments that interfere with communication. It is best to be certain you have the person’s attention before beginning a purposeful interaction. Eliminate outside distractions. Try to introduce one idea at a time. Do not rush the person because this may cause confusion.

It is especially important to obtain feedback from an older adult that the message has been clearly understood. If people have difficulty comprehending, they may just nod their head, pretending to understand, for fear of appearing dense or forgetful. Many are embarrassed about their hearing deficiency.

Wait for an answer to one question before asking another. Try not to introduce more than one subject at a time in the conversation, and give only one instruction in any one sentence. It is also important for all members of the health care team to communicate in a consistent manner with elderly patients (Assignment Considerations 8-1).

COMMUNICATING WITH CHILDREN

The influence of development on language and thought processes must be taken into account to communicate effectively with children. Young children are very responsive to nonverbal messages. A young child may become frightened by sudden movements or gestures. Approach the child at eye level and use a calm, quiet, friendly voice when communicating.

When interacting with an infant, try to keep the mother within the baby’s view. With a toddler or a preschooler, focus on the child’s needs and concerns. Use simple, short sentences, and concrete explanations with familiar words.

For the school-age child, give simple explanations and demonstrate how equipment works. Allow the child to handle the equipment if possible. Listen carefully to the child’s fears or concerns.

An adolescent needs time to talk. Use active listening, avoid interrupting, and show acceptance. Try not to give advice, and avoid embarrassing questions if at all possible.

Above all, with any child, be honest and tell the child what to expect.

COMMUNICATING WITH PEOPLE FROM OTHER CULTURES

Determine if the person speaks and understands English. If not, obtain an interpreter if possible. Be accepting; do not show impatience with lack of ability to speak English. Most health care agencies have a list of interpreters that can be called for assistance with translation (Figure 8-5).

Follow the patient’s lead about the use of eye contact. If the patient is not comfortable making eye contact, respect this cultural difference. The same is true for the use of distance between you and the patient when speaking. Watch how much distance is maintained between the patient and other people when they interact. Cultural Cues 8-4 presents strategies to use when teaching older adults from other cultures.

For the nurse who is from another culture and whose primary language is not English, it is very important to work on English language skills and correct pronunciation. Your patients are dependent on good communication with you. If you cannot communicate well in English, you may miss catching important signs and symptoms of a change in a patient’s condition. Inability to communicate well with the nurse adds further stress to the patient’s situation and leads to dissatisfaction with care. Most communities have classes for students who wish to improve their English.

COMMUNICATION WITHIN THE HEALTH CARE TEAM

Communication within the health care team occurs through writing and reading nurses’ notes, physicians’ orders, the dietitian’s notes, and notes and orders of the respiratory, physical, speech, and occupational therapists, as well as listening to and giving a shift report (a verbal communication on the details of a patient’s condition and treatment). Filling out a wide variety of forms for the laboratory, radiology, and other departments is another method of communication. Entering information on the computer is an essential tool for communication among hospital departments. Clear communication is necessary when consulting with the physician about orders and when delegating tasks to ancillary workers.

END-OF-SHIFT REPORT

Many different formats are used to give a report. Sometimes the report is given as the nurses from the off-going and on-coming shifts walk around from room to room together. This method is termed walking rounds. If the report is recorded on an audiotape or if computerized sheets are used, there must be an opportunity to ask and respond to questions. Whatever format is used, the same essential information is necessary for each patient. Get in the habit of organizing the report in the same way each day. A full report on each patient should take about 1 to 3 minutes. Give only essential information. It takes practice to give a logical, organized, concise report on a group of patients. Practicing at home with a tape recorder can help you gain confidence and present information more concisely. Box 8-2 presents the information usually given in an end-of-shift report. One style that can be used for reporting is the SBAR (situation, background, assessment, and recommendation) format (Safety Alert 8-1). If the initial information is handed out on a computer printout, it need not be repeated. The room number and name of the patient are sufficient as a starting point.

Computer-printed Kardex-type information sheets are available at the beginning of the shift for the oncoming nurse in most hospitals. This sheet can be taken and used as a work organization sheet. If notes are added to the sheet during the shift, all the information needed for the report at the end of the shift should be readily at hand.

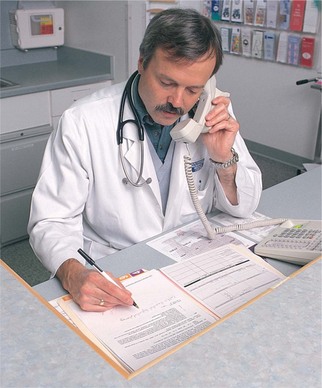

TELEPHONING PHYSICIANS

Physicians must be telephoned from time to time. Orders may be unclear, the patient’s condition may change, the patient may have a particular request, or further information about the patient may be needed from the physician.

If a physician is called regarding a change in a patient’s condition or in any situation in which new orders are anticipated, certain steps should be followed. Have current data on the patient at hand, including data from the last vital signs assessment, pertinent laboratory data, information on urinary output, and medications received. Keep the chart handy, have a pencil and paper ready, and anticipate the information that the physician might need to make a decision. Know what allergies the patient has. Perform a quick assessment before calling, and prepare a concise statement of the problem or concern. Document the call, and note the health care provider’s statement that the order is correct as read (Safety Alert 8-2).

In addition to its use for the end-of-shift report, SBAR can also be used when communicating with or telephoning physicians (Box 8-3).

The student nurse should have an instructor or another registered nurse standing by to take the new orders from the physician because students cannot legally take telephone orders.

ASSIGNMENT CONSIDERATIONS AND DELEGATING

You must communicate well in order to assign tasks and delegate (authorize another person to do something) to others effectively. Give clear, concise messages and listen carefully to feedback. Include the desired results and the time constraints for completion of the task. It is better to say “Let me know if Mrs. Hope’s noon temperature is above 101.2° F” than to say “Let me know if Mrs. Hope’s temperature is high.” Ask the person to whom you are assigning a task if there are any questions about what is to be done, and ask for a summary of what is understood about the task to be done.

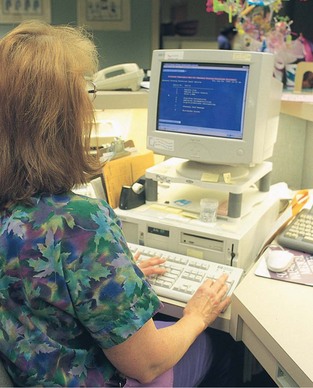

COMPUTER COMMUNICATION

The computer is used to transmit requests for laboratory, dietary, radiology, physical therapy, respiratory therapy, and other services. Medication orders from the physician are entered into the computer in the pharmacy, and the orders are communicated to the nurse on a patient medication administration record. Supplies for patient care are ordered on the computer, and patient care plans are updated using the keyboard or a touch screen (Figure 8-6). Legal & Ethical Considerations 8-1 includes additional tips regarding computer usage in health care settings.

Many hospitals and home care agencies are converting to a computerized form of charting. In some agencies a hand-held computer is used to note medications given, input (put in information) vital signs, chart assessment data, and record the nurse’s observations. The ability to use a computer for communication is essential for today’s nurse.

COMMUNICATION IN THE HOME AND COMMUNITY

Nurses who work in home care often have both a professional role and a social role with their patients and families. Often, the nurse is the only person whom the patient sees on the day of a visit. Because of the social aspects of the visit, it is essential to state when instructions are about to be given so that active listening can occur. Home Care Considerations 8-1 gives additional tips to help you maximize your interview time. Leave written step-by-step instructions with the patient whenever possible. This can prevent many problems. The primary nurse will often call between visits to see how treatment is progressing and to assess for any problems. Safety Alert 8-3 gives additional information that applies to home care phone communication.

Office and clinic nurses often assess patients who call in to see if they have an urgent need for medicalattention. Such assessment requires good communication to obtain the data needed to make such a decision (Figure 8-7). The office nurse gives telephone instructions to patients on how to treat minor illnesses or injuries. It is important in these situations to obtain feedback so that there is no doubt that the patient understands the instructions.

NCLEX-PN® EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Choose the best answer(s) for each question.

1. The nurse is using therapeutic communication to establish rapport. The nurse says, “How are you feeling this morning?” Which nonverbal behavior is congruent with the nurse’s verbal question?

1. Looks at patient; stands with a relaxed body position

2. Nods head up and down; arms folded across chest

3. Smiles at patient and makes the bed while patient answers

2. A patient expresses serious concerns about the outcomes of a scheduled surgical procedure. Which of following indicates that the nurse is using active listening while the patient is speaking?

1. Nurse tells the patient not to worry about the surgery.

2. Nurse asks the patient to take her medication before continuing.

3. The patient says, “I don’t know whether chemotherapy or radiation would be best to treat this cancer.” Correct restatement would be:

1. “You think radiation would be best.”

2. “You’d prefer to have the chemotherapy.”

3. “You wondering if chemotherapy or radiation brings the best survival results.”

4. “Tell me what you think about each one of those treatments.”

4. A patient says, “I don’t know what to do about the problem.” The most therapeutic response would be:

1. “You should define the problem and make a plan.”

2. “What options are you considering?”

5. The patient is aphasic. Which of the following communication strategies would be appropriate in working with this patient? (Select all that apply.)

1. Lean forward and say “Go on….”

2. Face the patient, establish eye contact, and speak slowly.

3. Use pantomime to enhance the words.

4. Give the person time to respond to questions.

5. Explain procedures to the family member instead of the patient.

6. The patient is about to undergo surgery. Which of the following is an example of false reassurance?

1. “Your surgery will take about 5½ hours.”

2. “You’ll come through this procedure just fine.”

3. “Your family will be allowed to see you as soon as you are awake.”

7. Which of the following elements characterizes a therapeutic relationship?

1. Focus is on the patient’s needs and there are specific goals.

2. The patient and the nurse get satisfaction from the relationship.

3. The patient and the nurse equally exchange information.

4. The relationship is terminated if needs are not being satisfied.

8. When you are conducting a home care admission interview, time will be saved by:

1. informing the patient of the purpose of the interview.

2. calling the patient and asking her to make a list of her medications.

9. A way to promote trust with a patient is to:

1. allow family members to visit whenever they want.

2. assure the patient that her doctor is excellent.

3. follow through when you say you will do something.

4. talk with her at length, about her life, likes, and dislikes.

10. A nurse is assigning a task to the nursing assistant. Which of the following is the best example of how to communicate the task to the assistant?

1. “Please do all the vital signs for my patients, and pay special attention to Mrs. Hondo and Mr. Takedo.”

2. “Please report any abnormal vital signs throughout the day, and keep an eye on Mrs. Hondo and Mr. Takedo.”

3. “Please check Mrs. Hondo’s and Mr. Takedo’s blood pressure and pulse as ordered by the physician. Call me if you have problems.”

4. “Please do vitals signs at 8 A.M. on Mrs. Hondo and Mr. Takedo, and if the pulse is more than 85 per minute, let me know.”

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES ? Read each clinical scenario and discuss the questions with your classmates.

You are working with a patient who is very quiet and withdrawn. When you walk into her room, she appears tearful and upset, but she tells you that there is nothing wrong. How would deal with this situation?