Facial Esthetic Surgery

Patients are increasingly seeking procedures that enhance their appearance for personal and professional reasons. Esthetic oral and maxillofacial surgery is often included in a comprehensive treatment plan to complement restorative, prosthetic, and orthodontic treatment. Dental treatment plans, especially ones involving cosmetic therapy, are enhanced if dentists remain aware of the wide variety of esthetic surgical options available to patients. Orthodontists planning orthognathic surgery complete a careful evaluation of facial proportions that frequently includes the diagnosis of external nasal deformities and other hard and soft tissue abnormalities. Prosthetic rehabilitation often involves attempts to increase support to the perioral region and can be enhanced with facial rejuvenation procedures. Cosmetic restorative dentistry may provide the finishing touch to cosmetic surgical treatment. Pediatric dentistry patients with traumatic scars or congenital deformities can also be helped. Patients with oral and head and neck pathologic conditions such as skin cancers can be treated, reconstructed, and restored to adequate function and socially acceptable appearance.

Advances in medicine and nutrition, combined with increased public awareness of personal health care, enable patients to live longer, healthier, and more active lives. However, social pressure to maintain a youthful appearance as one ages encourages more individuals each year to undergo some form of esthetic enhancement. This trend is evident in members of the baby boomer generation, now in their 40s, 50s, and 60s, who have grown increasingly interested in these procedures.

Research from the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery indicates that the number of patients undergoing esthetic procedures continues to increase yearly. Body liposuction is the most frequent surgical procedure, and it is surpassed by Botox (botulinum toxin) injections as the most popular nonsurgical cosmetic procedure. Facial procedures, such as eyelid rejuvenation, face-lifts, and facial skin rejuvenation, also continue to increase.

Women seeking esthetic surgery outnumber men approximately 9:1. However, men are increasingly seeking esthetic procedures, including eyelid and forehead rejuvenation and hair restoration. As expected, the popularity of specific procedures is age related. Patients under 35 years of age usually desire liposuction, rhinoplasty, chemical peels, and laser skin resurfacing. As patients age into their 40s, 50s and 60s, they seek liposuction, eyelid and forehead rejuvenation, face-lifts, and chemical or laser skin resurfacing.

Surgical technical advances also contribute to the growth of esthetic surgery. New techniques and technical advances in equipment reduce surgical risks, recovery time, and incision visibility. Technical innovations include endoscopic or minimally invasive procedures that use small incisions, liposuction with barely noticeable access sites, and lasers that enhance hemostasis and allow precise control over depth of skin removal.

Appearance matters more than many wish to admit, and interpersonal reactions are often influenced by appearance. Improved self-confidence occurs in many patients who have undergone successful esthetic surgical and cosmetic dental procedures. One commonly notices patients altering their wardrobe, makeup, and hairstyle after surgery; patients often are delighted in how others respond to their new image. However, it is important during the esthetic surgery consultation for the surgeon to attempt to determine whether the patient’s desires for surgery are based on personal motivation, without undue outside influences or unrealistic expectations. Patients with external pressures and unrealistic expectations are more likely to be dissatisfied with the treatment outcome despite successful technical results.1,2

FACIAL AGING

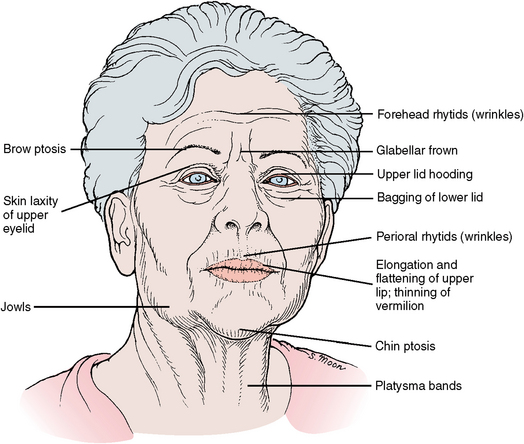

Facial aging involves the changes to the skin itself and resultant effects on the appearance of the skin and on the underlying soft tissues. Natural aging combined with sun exposure produces a wide range of skin changes. Natural aging results in loss of skin elasticity and collagen, melanocyte pigmentations, and fat atrophy. Sun exposure adds photoaging caused by ultraviolet light. Ultraviolet light from sun tanning damages the skin and eventually causes a wrinkled, pigmented, and weathered appearance. Solar radiation also leads to an increased incidence of skin cancers. Gravitational changes on the skin and underlying tissues cause deep forehead lines, drooping brows, eyelid skin laxity and puffiness, loss of cheek roundness, and sagging neck and jaw lines (Fig. 26-1).

Although aging is an individual phenomenon, many factors can influence the appearance and rate of aging. These factors include general health, sedentary lifestyle, sun exposure, genetic influences, nutritional balance, alcohol consumption, and cigarette smoking. Cigarette use, with its vasoactive effects of nicotine, accelerates skin aging and reduces the ability of the body to repair wounds. The vasoactive effects can lead to poor healing in some esthetic surgical procedures.3,4

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

The procedures described in the following sections are presented as isolated surgical techniques. However, in practice, several of these are often combined and performed during a single surgical appointment.

Blepharoplasty

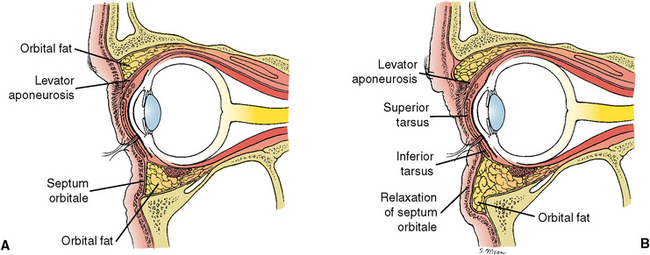

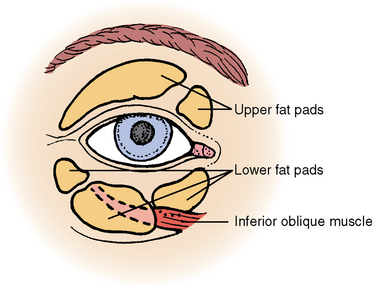

Blepharoplasty (i.e., eyelid rejuvenation) is one of the most common facial esthetic procedures performed on women and men. Aging eyelids exhibit a puffy, drooping, and baggy appearance. These effects are the result of eyelid skin laxity, orbicularis muscle hypertrophy, and orbital fat herniation out into the eyelids (Fig. 26-2). Redundant and folded skin of the upper eyelids is referred to as dermatochalasis. When extreme, the folded skin can extend beyond the eyelash margin and create a mechanical block to vision. Patients typically notice this later in the day when their “eyes are tired.” This sagging, redundant, and folded upper eyelid skin over the lashes is termed hooding. The main cause of baggy lower eyelids is gradual thinning and laxity of the fine collagenous orbital septum. This structure normally separates the internal orbital contents from the eyelid. Over time this curtainlike structure bows outward like a sail, and then the intraorbital fat begins to herniate into the lower eyelids. The upper eyelid has two fat pads and the lower has three (Fig. 26-3). Besides the pouchlike filling of the lower eyelid, the outward shift of the orbital fat can create a subtle posterior settling of the globe (i.e., eyeball). This adds to the appearance of sunken in, tired, and baggy eyes.

FIGURE 26-2 A, Normal sagittal view of the orbit and eyelids. B, With aging, orbital fat protrusion extends out into the upper and lower eyelids. This is due to a lax orbital septum. This gives a baggy appearance of the lids.

FIGURE 26-3 Orbital fat pads of the right eye. Upper, Medial and central. Lower, Medial, central, and lateral.

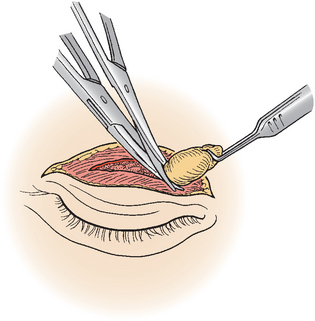

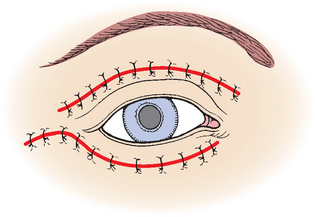

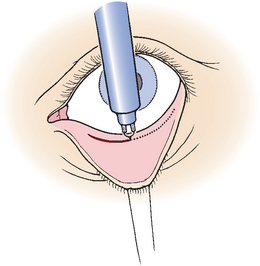

During a blepharoplasty procedure, the surgeon removes excess skin and orbicularis oculi muscle and an appropriate amount of protruding orbital fat behind the bulging orbital septum (Fig. 26-4). The upper eyelid incision is hidden in the upper lid crease. The lower eyelid surgery can be performed in two ways: (1) with an incision just below the eyelashes (i.e., subciliary) or (2) from inside the lower lid (i.e., transconjunctival; Figs. 26-5 and 26-6). With the transconjunctival approach, the surgeon removes fat but does not excise any skin, and relies on a skin-tightening procedure, such as chemical peel or laser resurfacing, to treat any remaining skin laxity.

Recovery time from eyelid surgery is usually 7 to 10 days (Fig. 26-7).5,6 Blepharoplasty can result in complications, which include excessive or inadequate skin removal, excessive or inadequate fat removal, dry-eye sensation, and intraorbital bleeding with rare but possible blindness.

Forehead and Brow Lift

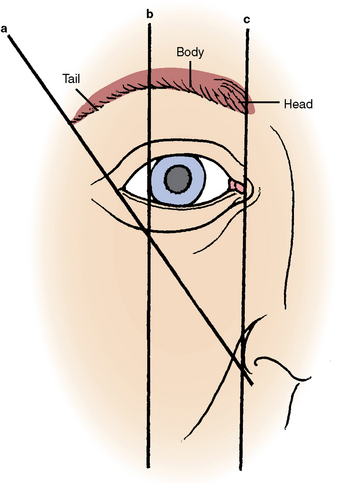

A drooping forehead results in drooping eyebrows (i.e., brow ptosis), lateral upper eyelid fullness or hooding, and accentuated upper eyelid bagginess. Removing eyelid skin with blepharoplasty alone does not adequately address this problem if the brows are also ptotic. The normal or youthful eyebrow has the lower edge positioned at or slightly above the palpated bony supraorbital rim. The ideal esthetic female brow gently arches above the orbital rim lateral to the iris (Fig. 26-8). The peak of the arch of the brow should be aligned over the junction of the lateral edge of the iris and the sclera. Women often pluck their brows to reproduce this pattern. Male brows are generally flatter without an arch. Elevation of the brows to a rejuvenated position may eliminate or reduce the need to remove upper eyelid skin with blepharoplasty. Often a forehead and brow lift and upper lid blepharoplasty are combined during a single operation. Brow lifting reduces upper lid hooding by elevating the brow. Additionally, brow lifting reduces forehead and nasal bridge creases.

FIGURE 26-8 Right female eyebrow. The highest part of arch of brow occurs within the body (along line b), which transects the lateral limbus of the eye.

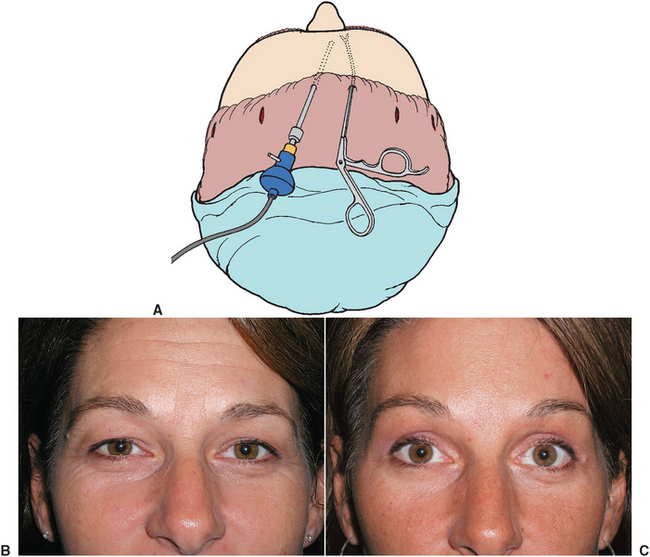

Most brow elevation surgeries are presently performed endoscopically with video camera assistance. This approach uses multiple small scalp incisions for access. After the scalp is undermined and mobilized, the forehead soft tissues are suspended and anchored in their new position (Fig. 26-9). A continuous full-thickness scalp incision within or at the hairline (i.e., pretrichial approach) is still used when required, such as with extreme brow ptosis or when one does not wish to elevate the hairline (Fig. 26-10). Care is taken to prevent injury to the sensory nerves (i.e., supraorbital and supratrochlear) and facial nerve branches of the scalp that supply motor innervation to the eyebrow region.

FIGURE 26-9 A, Endoscopic forehead surgery with lighted endoscope (left) and scissors inserted on right. B, Preoperative view. C, Postoperative view after endoscopic forehead/brow lift. (Photos courtesy Dr. Todd Owsley.)

FIGURE 26-10 The coronal forehead lift incision is placed several centimeters behind the frontal hairline.

Postoperative recovery is 7 to 10 days (see Fig. 26-7).7 Possible complications of brow lifting include asymmetric appearance, paresthesia, facial nerve deficits, and excessive lifting resulting in a “surprised” look.

Rhytidectomy

Rhytids are skinfolds, creases, or wrinkles. Rhytids can be referred to as coarse or fine depending on the depth and anatomic cause. Rhytidectomy, or “removal of skin wrinkles,” is more commonly called face-lift surgery. This procedure rejuvenates sagging neck skin, jowls (i.e., sagging skin and fat posterior to the labiomental crease), nasolabial folds, and cheek laxity. Face-lift surgery can result in an elevated cheek contour and a refined mandibular neckline.

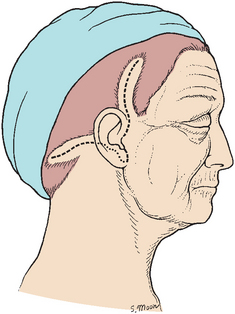

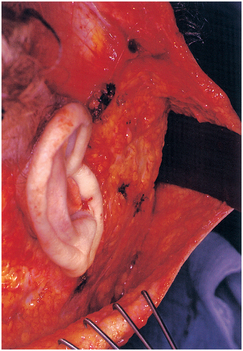

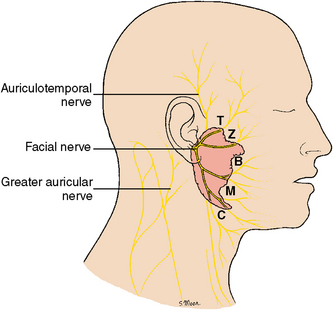

Numerous techniques are used for face-lift surgery. The most common technique uses a type of lazy S incision from the temple, around the ear, and into the posterior hairline (Fig. 26-11). The facial and neck skin is dissected and elevated in an upward and backward direction, and the underlying fascial layers are tightened (Fig. 26-12). The facial nerve must be protected during the dissection of the various layers (Fig. 26-13).

FIGURE 26-12 Face-lift dissection: Right posterior view of supine patient. A malleable retractor and tissue rake are seen adjacent to the ear.

FIGURE 26-13 Nerves associated with face-lift surgery. Motor: facial nerve and branches—temporal (T), zygomatic (Z), buccal (B), marginal mandibular (M), and cervical (C). Sensory: auriculotemporal and greater auricular nerve.

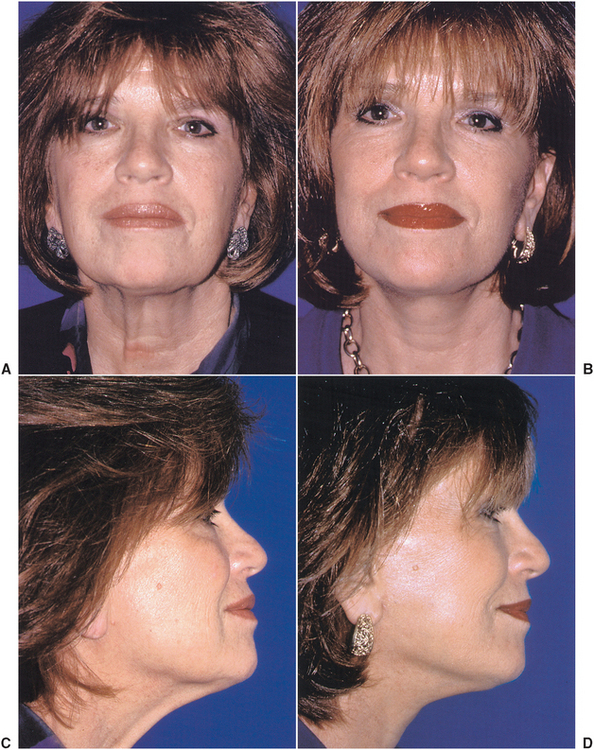

Frequently, the submuscular aponeurotic system layer is partially resected or is suspended superiorly (or both) and posteriorly to provide additional and longer-lasting effects. The excess skin is removed during wound closure (Fig. 26-14). To enhance neck contours, face-lift surgery often includes submental liposuction and platysma muscle tightening.

FIGURE 26-14 Face-lift surgery. A, Preoperative frontal view. B, Postoperative frontal view. C, Preoperative lateral view. D, Postoperative lateral view.

Recovery from face-lift surgery takes about 14 days.8,9 Potential complications include hematoma, facial nerve injury, and hypertrophic scar formation.

Septorhinoplasty

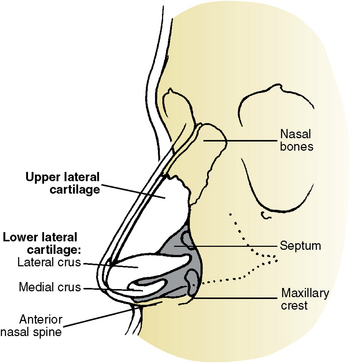

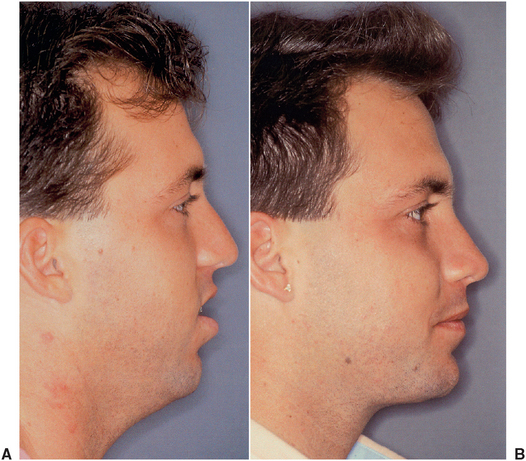

Nasal surgery, or rhinoplasty, can alter a patient’s nasal appearance and correct nasal obstructive symptoms. When the nasal septum is also modified, the procedure is called a septorhinoplasty. Appearance changes may include modifying the nasal profile, the nasal bridge width, removing a dorsal hump, or improving nasal tip definition (Fig. 26-15). Patients of all ages may undergo nasal surgery. Younger patients usually seek to balance their nasal proportions with their existing facial features and eliminate nasal obstructive symptoms. Older patients often have rhinoplasty to rejuvenate a drooping nasal profile. With aging the upper lateral cartilages can separate and drift away from the nasal bones above them, causing an apparent nose lengthening and drooping nasal tip. This occurs more commonly in men.

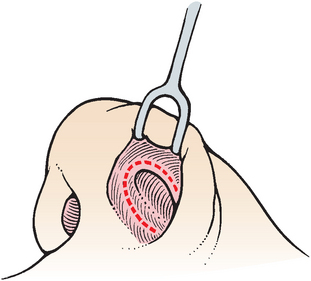

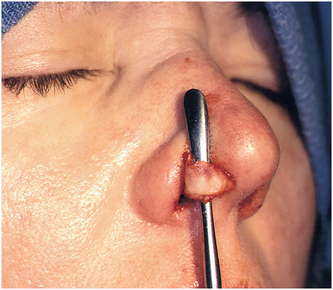

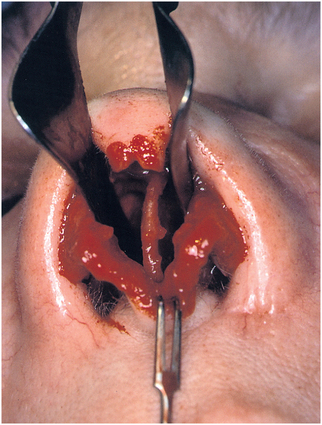

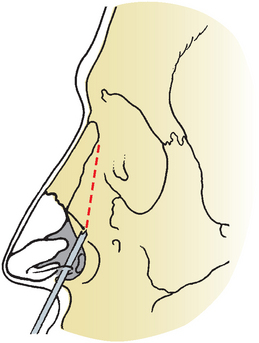

Nasal surgery is performed most often with all internal nasal incisions (Fig. 26-16). More extensive nasal surgical procedures may require an open approach, which uses an additional columellar skin extension incision (Fig. 26-17). During nasal surgery, the nasal tip cartilages are refined and the dorsal profile is improved with hump reduction and thinning. This is accomplished with a combination of trimming the nasal cartilages and shaping of the nasal bones, with rasping and bony osteotomies (Fig. 26-18 and 26-19). Nasal dressings postoperatively include an external supportive splint and internal packing as required. These dressings are removed in 3 to 7 days depending on the surgery.

FIGURE 26-17 Open rhinoplasty with nasal speculum in place showing nasal septum and lower lateral cartilages.

FIGURE 26-19 Lateral nasal osteotomy (dotted line) performed with an osteotome from the bony piriform rim to the proximal edge of the nasal bone. The nasal bones are then infractured, which narrows the nasal dorsum.

Initial recovery is 7 to 10 days, with final results more fully appreciated in about 3 months (Fig. 26-20).10 Potential complications include bleeding, asymmetry, infection, septal hematoma, and overcorrection or undercorrection.

Skin Resurfacing

Skin resurfacing eliminates wrinkles and pigmentary discoloration and significantly tightens the skin, resulting in a more youthful appearance. Patients may begin to notice perioral rhytids during restorative or prosthetic treatment. They may complain to their dentist that anterior prosthetic restorations do not adequately fill out their lips. Women may remark that their lipstick “bleeds” or runs outward into the skin of the lips. This occurs in the fine channels of the vertical perioral rhytids. The dentist is limited by the supporting jaws and occlusal relationships as to how far the underlying frame (i.e., teeth) can stretch and support the overlying canvass (i.e., lips). Although excision methods such as blepharoplasty or face-lift eliminate skin excess and contours, skin resurfacing treats the fine rhytids or wrinkles. Skin resurfacing is often performed after forehead lifts and face-lifts and blepharoplasties to achieve even more dramatic results.

Skin resurfacing collectively refers to chemical peels, dermabrasion, or laser skin resurfacing. Chemical peels use agents such as trichloroacetic acid, glycolic acid, or phenol. These chemicals cause the old superficial skin to peel off as if it were sunburned. This occurs after the new skin has reformed beneath the more superficial sloughing layers. Dermabrasion is a mechanical sanding performed with a diamond wheel or small wire wheel. Laser resurfacing vaporizes the skin and superficial layer of the dermis, usually with a carbon dioxide or erbium laser. Dermabrasion and laser have the advantage of recontouring irregular skin surfaces, such as traumatic or acne scars.

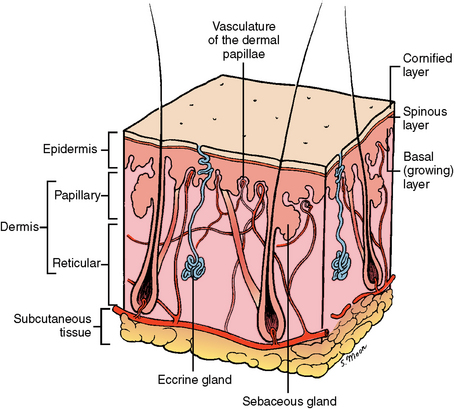

The chemical peel or laser or mechanical dermabrader typically penetrates from the papillary to midreticular layer of the skin (Fig. 26-21). The newly formed epithelium arises from the pores of the preserved deeper pilosebaceous units (i.e., hair, sebum, and sweat glands). The skin from these areas sprouts outward over the fresh, smooth, tightened surface. Surgeons frequently combine peeling with laser or dermabrasion on the same patient.

After the skin-resurfacing procedures are completed, various facial dressings are used to protect the skin during healing. The skin is healed or resurfaced in 5 to 14 days, depending on the method used and the depth of the treatment. The new, more youthful skin is tighter, smoother, and less irregularly pigmented. The tightening is due to new collagen formation within the dermis. The color of the fresh skin progresses from red to pink and returns to normal as it fully matures in 2 to 3 months. Makeup can be used after initial healing to camouflage the fading erythema.

Possible complications of these procedures include hyperpigmentation with postoperative sun exposure, hypopigmentation, hypertrophic scarring, and infection (Fig. 26-22).11,12

Facial Liposuction

Facial liposuction is used to reduce submental and neck fullness. These excessive fat deposits are typically located superficial to the platysma. This can be detected by having patients “tense their neck” or attempt to move their chin inferiorly against finger resistance and then gently grasping the submental area or neck fold with the thumb and forefinger (i.e., pinch test). The purpose of liposuction is to remove the underlying coalesced fatty deposits, allowing the overlying skin to redrape over a newly formed neckline. This occurs partially because of the direct removal of fat. Further “shrinkage” of fat deposits occurs as a result of circumferential scarring of the fat as a result of instrumentation with the suction cannula during fat removal. Younger patients often have facial liposuction as a single procedure because they have good skin tone that redrapes and adapts well. Older patients with skin laxity can also benefit from facial liposuction but often also need additional face-lift and neck lift surgery to tighten the skin or a platysmal muscle plication (i.e., corsetlike tightening by suturing techniques) to repair or tighten a central platysmal dehiscence. Only small incisions are necessary under the chin or behind the ear lobes to reach the entire neck. The fat is removed using a tubular cannula under vacuum suction (Fig. 26-23).

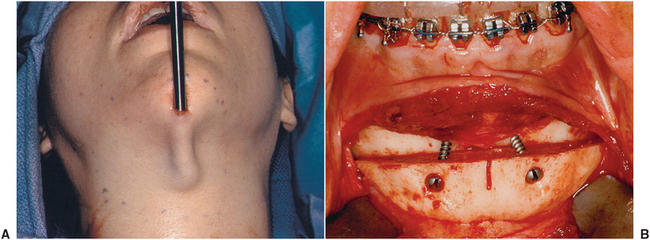

FIGURE 26-23 A, Submental liposuction with a cannula. B, Advancement genioplasty that can be done simultaneously with submental liposuction to enhance further the submental cervical form and definition.

After surgery a tight pressure dressing is applied to eliminate dead space and allow overlying skin to adapt closely to underlying soft tissue. Surgical recovery is 7 to 10 days, but 3 to 6 months are needed for the final results to be fully appreciated. This delay is due to the gradual process of remaining fat atrophy, remodeling, and skin tightening (Fig. 26-24).13,14 Potential complications include uneven contours, infection, or marginal mandibular nerve injury (i.e., facial nerve motor branch).

Cheek Augmentation

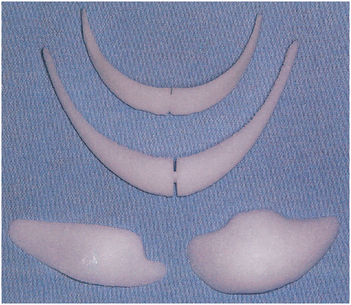

Cheek augmentation provides for higher, more defined, prominent cheek bones and more youthful cheek fullness. Cheek augmentation is usually accomplished using a synthetic or alloplastic implant placed through a maxillary vestibular incision. The malar or cheek implants are supplied precontoured by the manufacturers and are available in varying sizes, thicknesses, and configurations (Fig. 26-25). These implants can also be custom made from three-dimensional models of the patient’s facial bone structure made from reconstructed computed tomography scans. The surgeon selects the implants based on the patient’s existing anatomy and desired result. Generally, the implants are partially malleable and can be custom contoured in situ and then stabilized with bone screws to the underling maxilla and zygoma or suture retained within the soft tissue pocket that has been created.

FIGURE 26-25 High-density porous polyethylene implants. Precontoured shapes for chin augmentation (top, middle) and cheek augmentation (bottom, side by side).

Surgical recovery is 1 to 2 weeks with final results fully appreciated in about 2 months.15 Complications may include infection, overcontouring or undercontouring, or asymmetry. Transient infraorbital nerve paresthesia can be anticipated.

Chin Augmentation or Reduction

Chin projection and contour influences neck definition and nasal size appearance. Noses look larger if the chin is recessive and necklines are more defined with a more prominent chin. Decisions to augment or reduce the chin are decided by evaluating the facial proportions, similar to the treatment planning that takes place with orthognathic surgery or a patient undergoing comprehensive prosthetic rehabilitation that alters the vertical dimension.

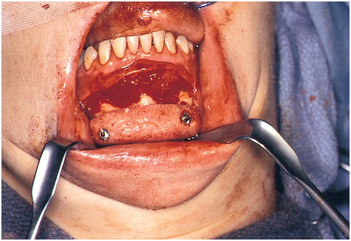

Augmentation of the chin can be performed using alloplastic implants or by advancement of the inferior border of the mandible (i.e., genioplasty) (see Fig. 26-23, B). Advancement genioplasty is discussed in Chapter 25. Alloplastic chin augmentation is not as popular with oral and maxillofacial surgeons because of lack of remodeling (i.e., edges may be felt), potential for underlying bone resorption, and increased risk of infection. Figure 26-26 demonstrates the use of an alloplastic implant for chin augmentation. Simultaneous liposuction can enhance the esthetic results of chin advancements.

FIGURE 26-26 Placement and screw fixation of an alloplastic chin implant through a vestibular incision.

Potential genioplasty complications include infection and lip numbness. Recovery time is about 1 week, with the final result fully appreciated in about 6 weeks.16,17

Otoplasty

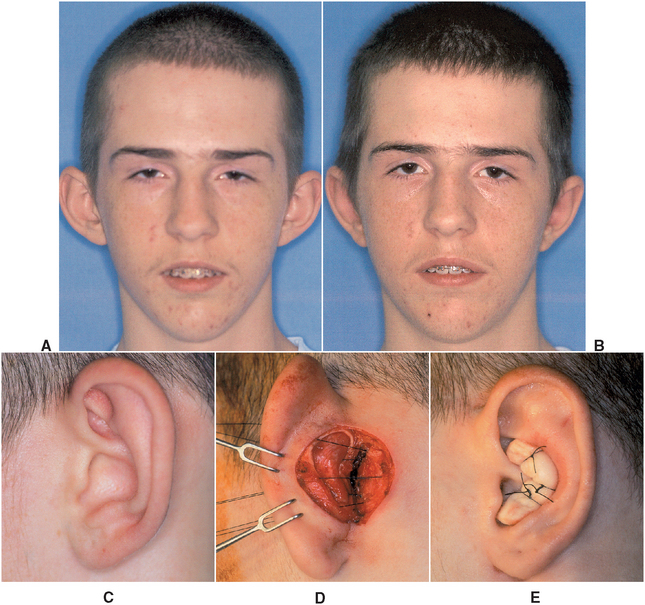

Otoplasty is altering the appearance of the ears. The most common ear deformity is overly prominent or protruding cupped ears. This deformity can be a source of awkwardness, especially in school-age children. Adults may also choose otoplasty for ear deformities not addressed while they were younger. Overly prominent ears are caused by hypertrophy of the conchal bowl cartilage (i.e., lower one half of the base) or lack of formation of the antihelical fold (Fig. 26-27, A and B).

FIGURE 26-27 Teenage boy with prominent ears caused by conchal bowl hypertrophy. A, Preoperative frontal view. B, Postoperative frontal view. C, Lateral view of right ear before surgery. D, Postauricular dissection with excess cartilage removed. E, Sterile cotton roll sutured into place to bolster the shape and serve as part of the pressure dressing.

Surgical correction involves exposing the ear cartilage through a postauricular incision. The cartilage is then partially excised or reshaped using cartilage scoring, sculpting techniques, and retention sutures (Fig. 26-27, C to E). A molded protective dressing is worn for 1 week, and the patient then uses a headband to protect the ears during sleeping for a number of months. Possible complications of otoplasty include infection, asymmetry, hematoma, and recurrence of the initial deformity.18

Lip Augmentation or Reduction

Lip augmentation can increase the thickness and vertical exposure of either the upper or lower lip. However, this procedure is most commonly performed on the upper lip to accent the perioral region. Generally, the lower lip is 30% larger in vertical dimension (i.e., vermilion to wet line) than the upper lip. Many methods for lip augmentation are available and include implantation of synthetic materials, bovine collagen, human cadaveric dermis, and autologous fat or dermis. Each material has its own advantages and disadvantages. The selected material is placed to plump the lip’s central vermilion and to define the vermilion border (Fig. 26-28).

FIGURE 26-28 Lip augmentation. A, Preoperative view. B, Postoperative photo. Note the increased vertical dimension of the upper lip. (Photos courtesy Dr. Todd Owsley.)

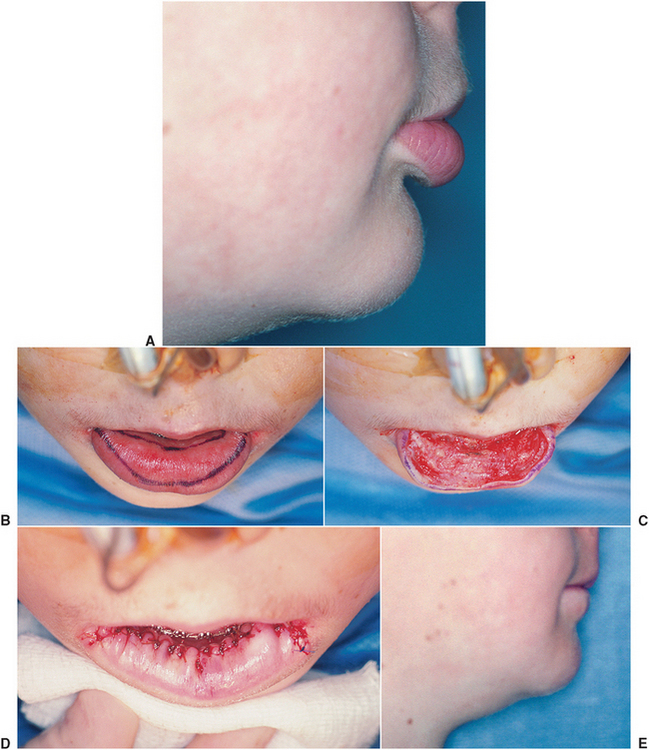

Although less commonly performed, lip reduction, or cheiloplasty, is also possible. Excess tissue is removed from the intraoral portion of the protuberant lip, and the lip mucosa is undermined and sutured in a more internally rotated position (Fig. 26-29). Recovery ranges from days to weeks, depending on the method used.5

FIGURE 26-29 A, Profile view of severe protrusion/eversion of lower lip. B, Outline of mucosal tissue to be removed. C, Surgical site after excision of mucosa. D, Wound closure. E, Postoperative profile view showing improved lip position.

Potential complications include infection, asymmetry, and overcorrection and undercorrection. Additionally, many of the natural materials placed in the lips resorb with time and may require further augmentation.

Botulinum Neurotoxin Therapy

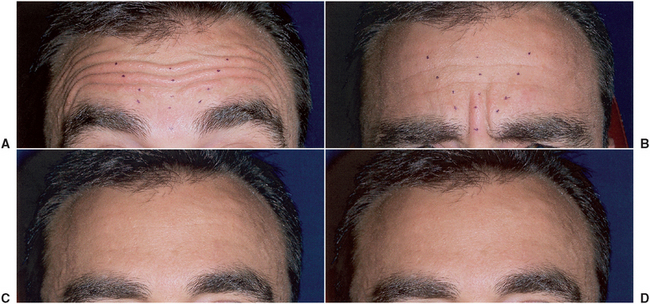

Although first used for treatment of eye muscle spasms and eye muscle dysfunction, botulinum neurotoxin can also be used to reduce facial wrinkles of the forehead and the crow’s-foot region (i.e., wrinkles emanating from the lateral canthus) around the eyes. Botulinum toxin is produced by the anaerobic microorganism Clostridium botulinum and is responsible for botulism food poisoning. The toxin blocks neurotransmitter release at the neuromuscular junction and thus temporarily paralyzes the muscle. The temporary paralysis creates long-term muscle weakness and atrophy. The most common region injected for facial rhytids is the forehead and glabellar region.

Very dilute doses can be safely injected with a 30-gauge needle selectively to paralyze specific facial muscles the animation of which has caused overlying skin wrinkles. The desired muscle paralysis occurs in 3 to 7 days and persists for 4 to 6 months (Fig. 26-30).

FIGURE 26-30 Botulinum toxin injection. A, Preoperative frontal view with eyebrows raised, accentuating heavy horizontal rhytids. Dots indicate planned injection sites. B, Forehead animated, causing vertical furrows in the glabellar region. C, Six weeks postinjection, showing residual upper forehead creases. D, Additional selective injection of the upper forehead yielded this 6-month postoperative result.

Retreatment with botulinum toxin injection may be necessary to further weaken or decrease muscle activity. Potential complications include diffusion into unintended muscles that can cause undesired eyebrow drooping or diplopia (i.e., double vision).19,20

Scar Revision

Facial scars can be caused by severe acne, facial trauma, or incisions needed for other surgery. Factors making scars noticeable include hypertrophy or keloids, uneven margins that cast shadows, color mismatch with surrounding skin, and tethering to underlying soft tissues that accentuates the scar during facial animation. Although a scar can never be totally eliminated, it can be altered and blended to significantly camouflage its appearance. Depending on the scar, it can be improved in appearance by reexcision, altered by redirecting its alignment to better hide it in a natural facial crease, or blended with a skin-resurfacing procedure (Fig. 26-31). Recovery time varies with the extent of the scar and the method of treatment.21,22 Possible complications include infection and hypertrophic scarring.

FIGURE 26-31 A, Patient who sustained multiple facial fractures and a full-thickness oblique laceration of the right cheek (has a tethered, thick, residual scar in this area). B, Intraoperative view of geometric outline. C, Excision of the scar that was undermined and sutured. D, Six weeks later the area was mechanically dermabraded. E, Postoperative appearance at 3 months.

Hair Restoration

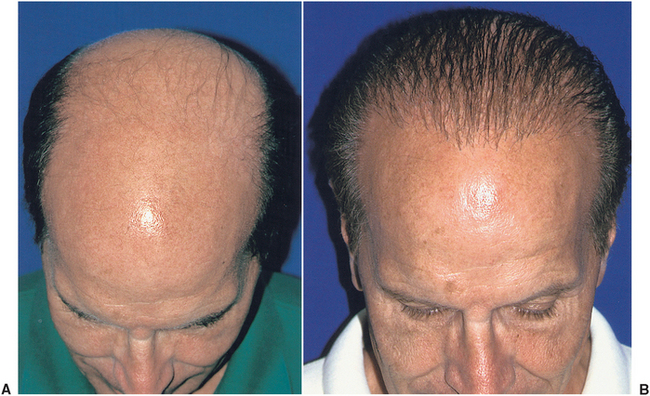

Although predominately associated with male pattern baldness, hair restoration can also be performed on women with alopecia. With improvement of surgical techniques that avoid a “plugged” appearance, hair restoration has increased in popularity.

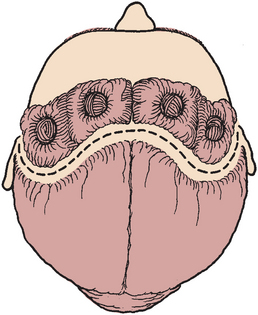

Hair follicles are harvested from the posterior scalp below the vertex and are prepared into micrografts and minigrafts of one to four hairs per graft (Fig. 26-32). The grafts are then meticulously placed into the desired locations to restore the hairline. Preoperative planning is important to avoid an inappropriate looking hairline as the patient ages, and to ensure that the patient has adequate hair density to obtain a good result. Surgical treatment may need to be performed in stages to complete the treatment plan. The grafted hair units are typically more resistant to the balding hormonal effects of testosterone and androgens.

Postoperative healing is complete in about 2 weeks, but the transplanted hairs do not begin to grow until about 3 months, and a final mature result is not achieved until 9 to 12 months after surgery (Fig. 26-33, A and B).23,24 Complications can include infection, loss of preexisting hair, poor graft growth, inappropriate hairline placement, and scarring.

SUMMARY

The current demand for facial esthetic surgery and cosmetic dentistry will continue to grow in popularity. The magnitude and appropriateness of any given comprehensive esthetic treatment plan should be carefully considered by the patient and dentist before initiation of any phase of the treatment. The oral and maxillofacial surgeon, trained in esthetic procedures and working with dental practitioners, can enhance the overall final esthetic result, leading to increased patient satisfaction.

REFERENCES

1. von Soest, T, Kvalem, IL, Skolleborg, KC, et al. Psychosocial factors predicting the motivation to undergo cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:51.

2. Rankin, M, Borah, GL, Perry, AW, et al. Quality of life outcomes after cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:2139.

3. Rees, TD, Liverett, DM, Guy, CL. The effect of cigarette smoking on skin flap survival in the facelift patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:911.

4. Rohrich, RJ. Cosmetic surgery patients who smoke: should we operate? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;5:1137.

5. Niamtu, J. Cosmetic oral and maxillofacial surgery options. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:756.

6. Werther, JR. Periorbital surgery as an adjunct to orthognathic surgery. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1996;8:77.

7. Niamtu, J. Endoscopic brow and forehead lift: a case for new technology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1129.

8. Alexander, RW. Cosmetic alteration of the aging neck-rhytidectomy. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1990;2:247.

9. Fulton, JE, Saylan, Z, Helton, P, et al. The S-lift facelift featuring the U-suture and the O-suture combined with skin resurfacing. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:18.

10. Kuhn, BS, Taylor, CO. Rhinoplasty: contemporary management of the nasal tip. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:947.

11. Demas, PN, Braun, TW. Chemical skin resurfacing. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1998;6:1.

12. Demas, PN, Bridenstine, JB, Braun, TW. Pharmacology of agents used in the management of patients having skin resurfacing. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:1255.

13. Alexander, RW. Liposculpture of the cervicofacial region. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1998;6:73.

14. Ota, BG. Cervicomental lipectomy as an adjunct to orthognathic surgery. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1996;8:67.

15. Zide, MF, Epker, BN. Cosmetic augmentation of the cheeks: alloplasty. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1990;2:359.

16. Strauss, RA, Abubaker, AO. Genioplasty: a case for advancement osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:783.

17. Aziz, SR, Ziccardi, VB, Zweig, BE. Biomaterials for post-traumatic maxillofacial reconstruction. In: Fonseca RJ, Betts NJ, Barber HD, eds. Oral and maxillofacial trauma. ed. 3. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:1017–1033.

18. Donlon, WC, Truta, M. Simultaneous otoplasty and temporomandibular arthroplasty. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:951.

19. Niamtu, J. Botulinum toxin A: a review of 1,085 oral and maxillofacial patient treatments. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:317.

20. Niamtu, J. Aesthetic uses of botulinum toxin A. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:1228.

21. Horswell, BB. Scar modification-techniques for revision and camouflage. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1998;6:55.

22. Slavkin, HC. The body’s skin frontier and the challenges of wound healing: keloids. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:362.

23. Hendler, BH. Hair restoration surgery-hair transplantation and micrografting. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1998;6:39.

24. Martin, RJ, Mangubat, EA. Hair transplantation: a review and case presentation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:654.