Facial Neuropathology

The dentist is frequently called on to diagnose pain in the oral and maxillofacial region. Although pain in the mouth is most frequently of odontogenic origin, many facial pains arise from other sources. The diversity of structures in the head and neck region (e.g., eyes, ears, salivary glands, muscle, joints, sinus membranes, intracranial blood vessels) can make arriving at an accurate diagnosis challenging. Even typical toothache symptoms may occur in a healthy tooth because of referred pain or a damaged pain transmission system.

BASICS OF PAIN NEUROPHYSIOLOGY

Pain is a complex human psychophysiologic experience. The sensory-discriminative aspect enables dentists to localize and quantify the pain, but it should be appreciated that this unpleasant experience is influenced by factors such as past experience, cultural behaviors, and emotional and medical states. As the term implies, the pain experience has psychological and physiologic aspects. The physiologic aspects involve several processes: transduction, transmission, and modulation. The sum of these processes, when integrated with higher thought and emotional centers, yields the human experience of pain. Transduction refers to activation of specialized nerves, namely A-delta and C fibers, which transmit information to the spinal cord, or in the case of the trigeminal nerve, to the trigeminal nucleus.

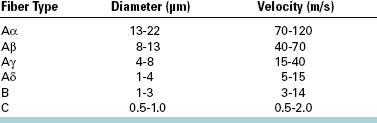

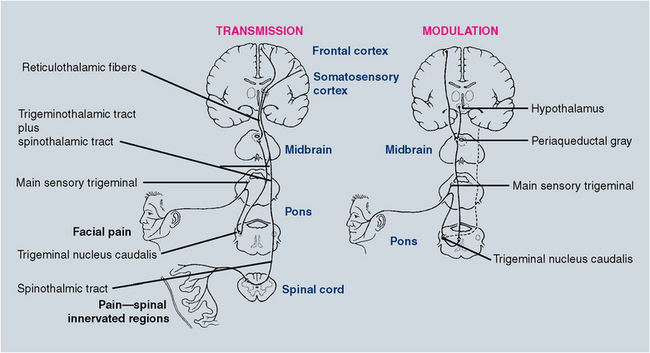

Table 29-1 lists peripheral nerve fibers and their individual characteristics. Chemical, thermal, and mechanical stimuli can activate the free nerve endings of nociceptors, the peripheral nerves indicated previously that transmit pain information. Once in the central nervous system (CNS), information regarding pain is transmitted to the thalamus and hence to cortical centers that process the sensory-discriminative and the emotional-affective aspects of the experience. Modulation systems are activated with pain transmission to varying degrees. The pain modulation system limits the rostral flow of pain information from the spinal cord and trigeminal nucleus to higher cortical centers. A schematic representation of these pain pathways is shown in Fig. 29-1. The chemical and receptor milieu in which transmission and modulation activity occurs is complex. The primary neurochemicals for transmission pathways involve glutamate and substance P, although dozens of neurochemicals have been implicated in pain transmission. The brainstem and spinal cord are the predominant structures involved in modulation. The related primary chemicals include the endogenous opioids, along with serotonin and norepinephrine. Alterations in receptor function are now thought to be critical to the generation of many chronic painful states.

FIGURE 29-1 Trigeminal and spinal pain transmission pathways (left). Trigeminal pain modulation system (right). Dotted line indicates decreased pain transmission.

Although the system appears hardwired as described previously, the psychological influences on pain perception should not be underestimated. For the dentist, this influence is a daily part of clinical practice. All dentists are well aware of the extensive variability of the pain response that different patients display to similar procedures. For instance, for some patients, the sound of the dental drill evokes true pain perception, despite the fact that the bur has not yet touched the tooth. Psychological influences are particularly important in determining perceived pain intensity and patient response to pain. When pain becomes chronic, generally defined as greater than 4 to 6 months in duration, attention to psychological influences can become particularly important when treating the pain experience.

CLASSIFICATION OF OROFACIAL PAINS

Numerous classification systems exist for orofacial pain conditions. At the most basic level, it is appropriate to classify orofacial pains as primarily somatic, neuropathic, or psychological.

Somatic pain arises from musculoskeletal or visceral structures interpreted through an intact pain transmission and modulation system. Common orofacial examples of musculoskeletal pains are temporomandibular disorders or periodontal pain. Examples of visceral orofacial pains include salivary gland pain and pain caused by dental pulpitis, the tooth pulp behaving like a visceral structure. Neuropathic pain arises from damage or alteration to the pain pathways, most commonly a peripheral nerve injury from surgery or trauma. Other causes may involve CNS injury as in thalamic stroke.

Orofacial pains of true psychological origin are so rare as not to be included in the differential diagnosis of orofacial pain for the general practitioner. Although psychological influences frequently modify the patient’s perception of pain intensity and the patient’s response to pain, an actual pain symptom generated by intrapsychic disturbance (e.g., conversion disorder or psychotic delusion) is exceedingly rare. Malingering, a term used to identify behavior in which a patient consciously feigns illness or the extent of illness for personal gain, can and does occur, although the literature suggests that the incidence is low. However, a dental patient complaining of chronic pain should be presumed to have a real pain problem unless definitively proved otherwise.

The term atypical facial pain is still seen in the literature and is used as a diagnosis primarily by physicians and some dentists; therefore a medical diagnosis code (i.e., International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, code) is associated with it. When reviewing the literature regarding atypical facial pain, a psychological cause is frequently implied. Because true psychogenic pain is rare, this term should be abandoned. For those undiagnosed facial pains, the appropriate term should be facial pain of unknown cause until a definitive diagnosis has been established. As a practical matter, these patients unfortunately continue to be labeled with the diagnosis of atypical facial pain for coding purposes, but the dentist should be aware that this is a “diagnosis” awaiting further clarification.

This chapter covers neuropathic facial pains and common headache disorders. Temporomandibular disorders are discussed in Chapter 30. A glossary of pain terminology is listed in Box 29-1.

NEUROPATHIC FACIAL PAINS

Neuropathic pains arise from an injured pain transmission or modulation system. Surgical intervention or trauma is frequently the cause. For example, trauma to the infraorbital region may lead to numbness or pain in the distribution of the infraorbital nerve. In oral and maxillofacial surgery, extraction of mandibular third molars carries a slight but measurable risk of nerve damage to the mandibular or lingual nerves. In the majority of these cases, damage leads to paresthesia, an abnormal sensation in the dermatome of the affected nerve. Typically, this sensation is one of mild numbness or tingling. Loss of all sensation may occur when the nerve is transected. In a subset of cases, dysesthesia—an abnormal, unpleasant sensation—can result; it is often described as a burning or sharp electric shocklike sensation. When a patient complains of burning or sharp shocklike pain in the face or mouth, pain of neuropathic origin should be included in the differential diagnosis. One should appreciate that the oral cavity is the most common site of amputation, if one recognizes amputations to include the teeth and the dental pulp (i.e., endodontics). As in phantom limb pain after extremity amputation, “phantom” sensations can also arise, albeit rarely, after dental and pulpal trauma or extraction. Neuropathic pains may also give rise to the sensation of tooth pain, which often is a diagnostic dilemma for the dentist. Referral of patients for management of these disorders to dentists focusing on orofacial pain diagnosis and management or to the patient’s personal physician or a neurologist is customary.

Neuropathic Facial Pains Presenting as Toothache

The prototypic neuropathic facial pain is trigeminal neuralgia (TN; Box 29-2), literally nerve pain arising from the trigeminal nerve. Although this could refer to any neuropathic pain of trigeminal nerve origin, TN or tic douloureux (i.e., painful tic) has specific inclusion criteria. Occurring most frequently in patients over 50 years of age (incidence 8:100,000; female-to-male ratio 1.6:1.0), TN usually occurs with sharp, electric shocklike pain in the face or mouth. The pain is intense, lasting for brief periods of seconds to 1 minute, after which there is a refractory period during which the pain cannot be reinitiated. At times, a background aching or burning pain is present. Usually a trigger zone is present where mechanical stimuli such as soft touch may provoke an attack. Firm pressure to the region is generally not as provocative. Common cutaneous trigger zones include the corner of the lips, cheek, ala of the nose, or lateral brow. Any intraoral site may also be a trigger zone for TN, including the teeth, gingivae, or tongue. Trigger zones in the V2 and V3 distributions are most common, after which they occur alone (and in decreasing order of incidence) in the V3, V2, and V1 distributions. The pain of TN illustrates an important distinction of many neuropathic pains as opposed to somatic pains—the lack of a typical graded response to increasing stimulation. If light stimulation produces a pain response out of proportion to the stimulus, a neuropathic process should be considered. This also holds true for pain that has a burning or electric shocklike quality. Sometimes a background aching pain accompanies TN, making it difficult to distinguish from the pain of acute pulpitis or possibly periapical periodontitis. Importantly, local anesthetic block of the trigger zone arrests the pain of TN for the duration of anesthesia and sometimes longer, which can lead the dentist to ascribe a “dental” cause to the pain complaint.

The cause of TN is not entirely clear, but the consensus is that pressure on the root entry zone of the trigeminal nerve by a vascular loop leads to focal demyelination. This demyelination in turn precipitates ectopic or hyperactive discharge of the nerve. The site of demyelination determines the trigeminal division involved and hence the clinical presentation. Other diseases such as multiple sclerosis, tumors, and Lyme disease can produce pain similar to that produced by TN. The treatment of TN is medical or surgical. Medical treatment is generally undertaken with anticonvulsants.

The classical medication for the condition is carbamazepine, but newer anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin and oxcarbazepine) and the antispastic baclofen, are commonly used as well. Table 29-2 lists commonly used TN and neuropathic facial pain medications. Many of these medications have significant, even life-threatening, side effects; therefore, only dentists focusing on orofacial pain diagnosis and management use them in dental practice. Surgical treatment includes microvascular decompression of the offending vascular loop (so-called Janetta procedure), GammaKnife radiosurgery, percutaneous needle thermal rhizotomy, or balloon compression of the root entry zone. For the dentist, the critical issue is recognizing TN so that unneeded dental treatment or extraction is avoided. Unfortunately, when the trigger zone is located in an intraoral, dental, or periodontal site, unnecessary dental treatment is common.

TABLE 29-2

Common Medications for Trigeminal Neuralgia and Neuropathic Facial Pains

| Medications | Dosage (mg/d) |

| ANTICONVULSANTS | |

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol) | 400-1200 |

| Gabapentin (Neurontin) | 600-3200 |

| Clonazepam (Klonopin) | 2-8 |

| Divalproex (Depakote) | 500-2000 |

| Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal) | 300-2400 |

| Lamotrigine (Lamictal) | 50-500 |

| Topiramate (Topamax) | 50-400 |

| Phenytoin (Dilantin) | 300-600 |

| TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS | |

| Amitriptyline | 10-300 |

| Doxepin | 10-300 |

| Nortriptyline | 10-150 |

| Imipramine | 10-300 |

| ANTISPASTIC | |

| Baclofen (Lioresal) | 15-80 |

Pretrigeminal Neuralgia

Although a rare condition, pretrigeminal neuralgia (pre-TN) has been recognized for some time. The presenting condition is typically an aching dental pain in a region where physical and radiographic examination reveals no abnormality. Local anesthetic block of the tooth (or extraction site, if applicable) arrests pain for the duration of anesthetic action. A number of patients with this condition have been demonstrated to go on to have typical TN symptoms (i.e., sharp electric shock pains the area). Pre-TN responds to similar treatments as TN, beginning with anticonvulsant therapy. To avoid unnecessary dental treatment, the dentist must have a high index of suspicion for secondary diagnoses for those pains that are inconsistent with physical examination or do not respond in a predictable way after treatment. Clinical features of pre-TN are listed in Box 29-3.

Odontalgia Resulting from Deafferentation (Atypical Odontalgia)

Pain resulting from deafferentation refers to pain that occurs when there has been damage to the afferent pain transmission system. Usually this condition is caused by trauma or surgery, including extraction and endodontic treatment. By definition, extraction and endodontics are deafferentating because they involve amputation of tissue that contains the nerve supply of a human structure, the tooth. Limb amputation is another example of a deafferentation procedure. As with phantom limb pain, a similar picture of oral deafferentation pain may occur, but only in a small subset of patients are the symptoms severe enough to warrant treatment. These pains may be maintained by various mechanisms, some readily appreciated and others complex and not yet completely understood. Peripheral hyperactivity at the site of nerve damage is easily understandable. At the site of dental alveolar nerve damage, neuronal hyperactivity leading to persistent pain occurs. In this form, the pain is frequently arrested with local anesthetic block. CNS hyperactivity, however, also can be responsible for persistent pain experienced in the tooth site. In this model, peripheral neural damage leads to changes in the second-order nerve in the trigeminal nucleus that synapsed with the primary peripheral nociceptor. Changes occur centrally in which ongoing pain transmission to higher cortical centers can occur despite minimal or even no peripheral input. Local anesthetic block does not arrest pain in this circumstance.

Additionally, patients may exhibit both forms of compromise simultaneously (i.e., only a portion of pain may be arrested by local anesthetic block). Sympathetic nervous system activity has also been shown to augment some of these complex neuropathic processes. Clinical features of deafferentation pains are listed in Box 29-4. Interestingly, for many deafferentation pains, further peripheral surgical procedures frequently intensify symptoms and lead to a broader area of perceived pain. If pain resulting from deafferentation is suspected, further surgical procedures should be undertaken cautiously.

The key to recognizing all of these conditions, and avoiding unnecessary and potentially harmful dental treatment, frequently lies in obtaining an excellent description of the chief complaint, including quality of pain, duration, alleviating factors, and aggravating factors. The history of the complaint and how the symptoms have changed over time can also be valuable. A more complete discussion follows in the section Evaluation of Patient with Orofacial Pain.

Other Neuropathic Facial Pains

Although the following pains share common mechanisms with those discussed previously, it is appropriate to list them separately because they possess some unique characteristics.

Postherpetic Neuralgia

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is a potential sequela of herpes zoster infection. Shingles, or herpes zoster, may occur at any stage in a person’s life. Herpes zoster is the clinical manifestation of the reactivation of a lifelong latent infection with varicella zoster virus, usually contracted after an episode of chicken pox in early life. Herpes zoster occurs more commonly in later life and in immunocompromised patients. Each year in the United States, shingles strikes at least 850,000 persons. Most are over 60 years of age. By age 85, 50% of persons will have had a bout. Of those who do, 60% to 70% will have PHN. Varicella zoster virus tends to be reactivated only once in a lifetime, with the incidence of second attacks being less than 5%. PHN occurs after reactivation of the virus, which can lay dormant in the ganglia of a peripheral nerve. Most commonly, this is a thoracic nerve, but approximately 10% to 15% of the time the trigeminal nerve is involved, with the V1 dermatome affected in approximately 80% of cases. When reactivated, the virus travels along the nerve and is expressed in the cutaneous dermatome of that nerve. For a thoracic nerve, for example, the patient has a unilateral patch of vesicular eruption closely outlining the classical dermatome for that nerve. In the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, the V1 dermatome is outlined by rash. In the V2 or V3 distribution, intraoral and cutaneous expression is commonly seen. The acute phase is painful but subsides within 2 to 5 weeks. However, a subset of patients develops a deafferentation pain that, as discussed previously, can have peripheral, central, or mixed features. The pain is typically burning, aching, or shocklike (consistent with a pain caused by a neuropathic condition). Treatment is undertaken with anticonvulsants or the tricyclic or other antidepressants. Tramadol, a mild opioid with mild antidepressant effects, can be a useful adjunct. Local injection of painful sites, sympathetic block, or both is sometimes of value. Most importantly, preventive treatment of PHN with antivirals, analgesics, and frequently corticosteroids very early after rash presentation can significantly reduce the expression of PHN.

A related condition, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, is a herpes zoster infection of the sensory and motor branches of the facial nerve (VII) and in some cases the auditory nerve (VIII). Symptoms include facial paralysis, vertigo, deafness, and herpetic eruption in the external auditory meatus.

Neuroma

After peripheral nerve transection, the proximal portion of the nerve generally forms sprouts in an effort to regain communication with the severed distal component. When sprouting occurs without distal segment communication, a stump of neuronal tissue, Schwann cells, and other neural elements can form. This stump, or neuroma, can become exquisitely sensitive to mechanical and chemical stimuli.

The pain is commonly burning or shocklike. Frequently, a positive Tinel’s sign is present. In this test, tapping over the suspected neuroma produces sharp, shooting electric shocklike pain. Damage to the mandibular or lingual nerve after third molar surgery is another source for neuroma formation. Some oral and maxillofacial surgeons provide microneurosurgical treatment, which can be beneficial for some patients.

Although it is difficult to predict which patients will benefit from nerve repair, clearly neurosurgical intervention should be accomplished within 3 to 6 months to improve the likelihood of success. Again, the commonality of symptom presentation in multiple nerve injury models suggests the importance of eliciting the patient’s description of pain when facing a diagnostic dilemma.

Burning Mouth Syndrome

In this condition the patient perceives a burning or aching sensation in all or part of the oral cavity. The tongue is the most frequently involved site. Perceived dry mouth and altered taste are common. The cause is unknown, but a defect in pain modulation may be the most promising theory. Most patients are postmenopausal women, although hormone replacement therapy does not consistently affect symptoms. Approximately 50% of patients improve without treatment over a 2-year period, indicating the importance of placebo-controlled trials when scientifically testing any treatment modality. The predominant treatment approach is with anticonvulsants or antidepressants, although neither avenue, even in combination, shows consistent results.

Other Cranial Neuralgias

As with TN, any of the cranial nerves with a sensory component appears capable of a neuralgic presentation. The most common of the other cranial nerves to present this way is the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX). The presenting symptom is typically sharp, electric shocklike pain on swallowing with a trigger zone in the oropharynx or the base of the tongue. Pain is usually experienced in the throat or tongue but may be referred to the lower jaw. The facial nerve (VII) has a small somatic component on the anterior wall of the external auditory meatus in which shocklike pains are experienced (sometimes associated with symptoms of tinnitus, dysgeusia, and dysequilibrium). The vagus nerve (X) also has the potential for neuralgic activity manifesting as pain in the laryngeal region shooting deep to the mandibular ramus or even to the region of the temporomandibular joint. Most often, treatment of cranial neuralgias, like TN, involves the use of anticonvulsants; however, in some cases intracranial surgery is necessary.

CHRONIC HEADACHE

Headache has many causes and is one of the most common complaints made to the primary care physician. When headaches recur regularly, the majority are diagnosed as one of the primary (no other cause) headaches: migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. Although most headaches are centered in the orbits and temples, many may present in the lower half of the face, teeth, or jaws.

Migraine

Migraine is a common headache afflicting approximately 18% of woman and 8% of men. The first migraine headache typically occurs in the teenage years or in young adulthood but may begin in very young children as well. Before puberty, migraine occurs equally in both sexes. After puberty the ratio changes so that women are at least twice as likely as men to have migraines. Migraine headaches are unilateral in approximately 40% of cases. An “aura” may develop several minutes to 1 hour before headache onset in approximately 40% of patients. The aura is a neurologic disturbance, frequently expressed as flashing or shimmering lights or a partial loss of vision.

Complicated auras may produce transient hemiparesis, aphasia, or blindness. Upward of 80% of migraineurs have nausea and photophobia (intolerance to light) during attacks. Migraines typically last 4 to 72 hours. The International Headache Society criteria for migraine are listed in Boxes 29-5 and 29-6. Headache triggers include menstruation, stress, certain vasoactive foods or drugs and certain musculoskeletal disorders that produce pain in the trigeminal system (e.g., temporomandibular disorders). The mechanism for migraine headache, although not completely understood, appears to involve neurogenic inflammation of intracranial blood vessels resulting from neurotransmitter imbalance in certain brainstem centers. Migraine is a referred pain process, and the intracranial vessel involved determines the site of perceived pain (e.g., the orbit, temple, jaw, or vertex of the head). Preventive treatment is directed at normalizing neurotransmitter imbalance with antidepressants, anticonvulsants, β-blockers, and other drugs. Biofeedback and other therapies are also helpful. Treatment of acute attacks is with the “triptans” (e.g., sumatriptan [Imitrex], zolmitriptan [Zomig], rizatriptan [Maxalt], naratriptan [Amerge], and almotriptan [Axert]), ergots, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, opioid analgesics, antiemetics, and other agents.

For the dentist, knowledge of migraine is important because temporomandibular disorders may precipitate a migraine attack in a migraine-prone patient. Likewise, cervical spine and cervical muscular disorders may precipitate migraine. Also important is for the dentist to recognize that cervical and masticatory muscle hyperactivity often occurs during a migraine headache. Migraine may therefore be a perpetuating factor in some temporomandibular disorders or a reason for misdiagnosis. Although toothache and jaw pains are not a common expression of migraine, a number of cases have been reported in the literature and are seen with some frequency by pain specialists. When migraine is a cause of jaw or face pain, the key to the diagnosis is recognizing that nausea, sonophobia, and photophobia are not accompaniments of masticatory musculoskeletal disorders or jaw and tooth pain of dental origin.

Tension-Type Headache

The majority of patients who report to the physician with a chief complaint of headache are diagnosed with tension-type headache. The name can be misleading because “muscle tension” or “tension from stress” is not always present, alone or in combination. Tension-type headache is common in the general population, and most individuals experience at least one tension-type headache at some point.

Chronic tension-type headache is more common in women than in men. The headache is generally bilateral. Pain is frequently bitemporal or frontal-temporal in distribution. Patients commonly describe their pain as though their head is “in a vice” or a “squeezing hatband” is around their head. Headache can occur with or without “pericranial muscle tenderness” (i.e., tenderness to palpation of the masticatory and occipital muscles). To be defined as chronic tension-type headache, symptoms must be present longer than 15 days per month. The International Headache Society criteria for tension-type headache are listed in Box 29-7. Treatment of tension-type headache is commonly with tricyclic or other antidepressants. When tension-type headache occurs in migraineurs, migraine treatments are usually beneficial.

Psychosocial factors are often a contributing factor influencing tension-type headache. In this situation, cognitive-behavioral and other psychological therapies are frequently beneficial.

For the dentist, it is important to distinguish tension-type headache from masticatory myofascial pain. This can be confusing because both conditions have similar symptoms. It is significant that in myofascial pain, pressure to various head or neck muscles refers to the site of head pain, whereas in tension-type headache, pressure identifies the site of pain. Importantly for either condition, identifying the site of pain does not always imply the source of pain. Additionally, in tension-type headache, pain does not proportionally increase with increasing pressure to the headache site nor refer pain to other areas.

Cluster Headache

Cluster headache is an overwhelmingly unilateral head pain typically centered around the eye and temporal regions. The pain is intense, frequently described as a stabbing sensation (i.e., as if an ice pick was being driven into the eye). Some component of parasympathetic overactivity is present (commonly lacrimation, conjunctival injection, ptosis, or rhinorrhea). Headaches last 15 to 180 minutes and may occur once or multiple times per day, commonly with precise regularity (e.g., awakening the patient at the same time night after night). The headaches occur in clusters such that they may be present for some months and then remit for several months or even years. Alcohol ingestion consistently triggers headache, but only during cluster episodes. As opposed to most other chronic headaches, men are much more likely to have cluster headaches than are women (Box 29-8). International Headache Society criteria are listed in Box 29-9. Treatment, as in migraine, is preventive or symptomatic. Preventive treatment is accomplished with verapamil, lithium salts, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, and certain ergot compounds. Symptomatic treatment is with “triptans,” ergots, and analgesics. Oxygen inhalation at 7 to 10 L/min may be an effective abortive treatment.

Dentists must be aware that cluster headache frequently produces pain in the posterior maxilla, mimicking severe dentoalveolar pain in the posterior maxillary teeth. The pain is frequently stabbing and intense, although background aching may occur. Unnecessary dental therapy is, unfortunately, common. Common features can distinguish a toothache resulting from cluster headache from a toothache produced by a dental problem:

OTHER CHRONIC HEAD PAINS OF DENTAL INTEREST

Temporal Arteritis (Giant Cell Arteritis)

Temporal arteritis, more properly termed giant cell arteritis, is literally an inflammation (i.e., vasculitis) of the cranial arterial tree that can affect any or all vessels of the aortic arch and its branches. The condition is most prevalent in those over 50 years of age. The inflammation results from a giant cell granulomatous reaction. Polymyalgia rheumatica, the most common nonarticular rheumatologic condition causing diffuse muscle inflammation, is frequently a comorbid condition. Dull aching or throbbing temporal or head pain is a common complaint affecting 70% of patients and is the presenting symptom in one third of patients. Jaw claudication (i.e., increasing weakness and pain in the jaw or tongue with ongoing mastication) may lead the patient to visit the dentist for diagnosis. Any older patient reporting jaw or face pain not obviously of odontogenic origin and whose symptoms suggest temporal arteritis should be referred for an erythrocyte sedimentation rate test—a standard laboratory blood test. Although a negative test does not rule out temporal arteritis, a significantly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate may help confirm the diagnosis. A temporal artery biopsy may also be obtained, but again a negative test does not conclusively rule out the condition. Treatment is with high-dose corticosteroids, frequently for many months, and early treatment is necessary to avoid blindness caused by extension of the disease process to the ophthalmic artery.

Indomethacin-Responsive Headaches

A number of head pains respond primarily or exclusively to the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug indomethacin. One of these headaches, chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, is similar in presentation to cluster headache, although the attacks are short lived (lasting several minutes) and occur many times per day. Unlike cluster headaches, women are more often affected than men. Again toothache may be the initial presentation. Exertional headaches, as in weight lifting or during intercourse, may also produce intense, rapid-onset headache responsive to indomethacin. Hypnic headache, waking the patient from sleep generally within 2 to 4 hours of sleep onset and lasting 15 minutes to 3 hours, is frequently indomethacin responsive, but hypnic headache is not accompanied by symptoms of parasympathetic overactivity.

EVALUATION OF PATIENT WITH OROFACIAL PAIN

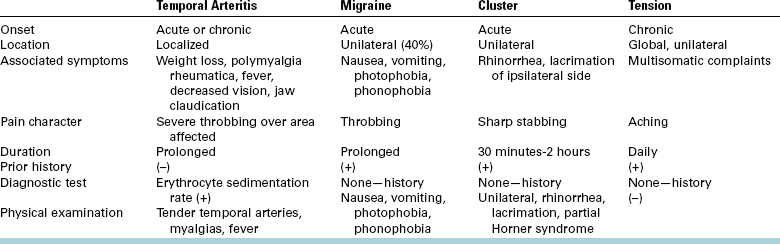

Evaluation of the dental patient who has jaw or face pain of nonodontogenic origin is an important skill for the dentist to master. Obtaining an accurate history is the most important component of information gathering. For chronic headache disorders and many neuropathic disorders, such as TN, pre-TN, and other cranial neuralgias, as well as burning mouth syndrome, generally no abnormality is found on physical examination; therefore the clinician must rely on the verbal history to arrive at an accurate diagnosis. Chronic headache disorders based on symptom description are presented in Table 29-3.

The pain history should include the chief complaint, including the current description of pain quality (e.g., aching, throbbing, burning, shocklike, paroxysmal, or some combination), intensity, when it occurs, how long it lasts, if it changes in character over time, precipitating factors, and alleviating factors. The history of the present illness should include date of onset, circumstances surrounding onset, how the pain evolved over time, diagnostic tests undertaken, diagnoses rendered, what treatments were instituted in the past, and the response to those treatments. Finally, a comprehensive medical and dental history should be taken. Most commonly a short differential diagnostic list can be made at this time. The physical examination attempts to narrow this list to obtain a working diagnosis.

The physical evaluation should include all aspects of the normal dental evaluation, including vital signs determination, intraoral examination with oral cancer screening, and head and neck examination with an evaluation of the temporal and carotid arteries, lymph nodes, skin, head, and neck, as well as myofascial and temporomandibular joint examination. In addition, a cranial nerve screening examination should be performed. It is understood that most dentists would not include all aspects of the formal neurologic examination, such as fundoscopic examination and testing of ability to smell, in this screening. See Table 29-4 for cranial screening evaluation. This latter examination is frequently an attempt to detect areas of hyperesthesia or hyperalgesia, allodynia, a trigger zone for TN, or an area of decreased sensation. In addition, it is important to define whether the pain follows normal neuroanatomic boundaries and, if so, to define these areas. Diagnostic anesthetic testing, usually with a vasoconstrictor-free solution, is appropriate to help define whether a suspected neuropathic pain condition has a significant peripheral component perpetuating pain.

TABLE 29-4

Rapid Cranial Nerve Examination for the General Dentist

| The examination begins with patient seated in the dental chair. The clinician asks if patient has any severe problems with seeing, hearing, or dizziness and observes patient for signs of visual or auditory problems, including whether the eyes move consensually. The clinician also checks for eyelid ptosis and mouth symmetry when patient smiles. |

| Next, the patient tries to hold eyelids tightly closed while the clinician tries to open them with the fingers. While patient’s eyes are closed, the clinician holds coffee or cloves to the patient’s nose and asks patient to identify the odor. The patient then opens the eyes widely while raising the eyebrows. The clinician shines a bright light into each eye individually and observes the reaction of each pupil. The patient looks directly left and right and then tries to look at each shoulder without moving the head. |

| The clinician then asks the patient to show the teeth, then pucker, and then evert the lower lip. Next the patient clenches the jaw closed while the clinician palpates each masseter muscle. The patient then opens the mouth and sticks the tongue straight out. While the tongue is out, the clinician uses a cotton-tipped applicator to stroke each side of the uvula briefly. With the clinician’s hands on the lateral aspects of the patient’s chin, the patient then tries to push fingers in front laterally against the hands. The clinician then rubs the fingers in front of each of the patient’s ears and asks what the patient hears. |

| Finally, areas of hypoesthesia or hyperesthesia should be identified and recorded. Areas of the pain complaint should receive special attention if nerve injury is suspected. Trigger areas for trigeminal neuralgia should also be investigated if symptoms warrant. |

| Cranial Nerve (CN) | Abnormal Test Results |

| I—Olfactory | Failure to identify odor may indicate nasal obstruction or CN I problem. |

| II—Optic | Failure of pupil to constrict or presence of nonconsensual gaze may indicate CN II problem. |

| III—Oculomotor | Failure of pupil to constrict or presence of ptosis may indicate CN III problem. |

| IV—Trochlear | Inability of eye to look to ipsilateral shoulder may indicate CN IV problem. |

| V—Trigeminal | Inability to feel light touch may indicate sensory CN V problem. Weakness of masseter may indicate motor CN V problem. Areas of hypoesthesia or hyperesthesia should be identified and recorded. Areas of pain complaint should receive special attention if nerve injury is suspected. Trigger areas for trigeminal neuralgia should also be investigated if symptoms warrant. |

| VI—Abducent | Inability of eye to look to ipsilateral side may indicate CN VI problem. |

| VII—Facial | Inability to raise eyebrows, hold eyelids closed, symmetrically smile, pucker, or evert lower lip may indicate CN VII problem. |

| VIII—Acoustic | Poor hearing or symptoms of vertigo may indicate CN VIII problem. |

| IX—Glossopharyngeal | Failure of uvula to elevate on stroked side may indicate CN IX problem. |

| X—Vagus | Failure of uvula to elevate on stroked side may indicate CN X problem. |

| XI—Accessory | Weakness in turning head against resistance may indicate CN XI problem. |

| XII—Hypoglossal | Deviation of tongue to one side may indicate CN XII problem on that side. |

When a peripheral component occurs, local anesthesia may arrest the pain for the duration of anesthesia. Most commonly, local anesthesia is applied to increasingly larger neuroanatomic regions. For instance, with a pain in the region of the mandibular canine, topical anesthesia in the anterior mandibular gingiva is applied. If pain is not arrested, the response to infiltration anesthesia is assessed. If no response is seen, a mental block (sparing the lingual nerve) is attempted, and finally, inferior alveolar and lingual nerve block anesthesia is undertaken if pain has not yet been alleviated. At each test, any alteration in pain response is noted.

Imaging is appropriate for many disorders to rule out an odontogenic, sinus, or bony pathologic conditions. The orthopantograph is helpful when supported by selected dental periapical radiographs as needed. For most neuropathic and headache disorders, intracranial imaging is important to rule out a CNS demyelinating process (e.g., multiple sclerosis in which TN may be the presenting symptom), vascular malformation, tumor, or other abnormality. Except for specially trained dentists, it is appropriate for the primary care physician or neurologist to order these studies. Other specialized studies (e.g., magnetic resonance arteriography, bone scan, and scintigraphy) may be indicated. With the information obtained from these studies, the dentist may elect to treat the patient or refer the patient to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, general dentist focusing on orofacial pain diagnosis and management, or an appropriate physician. The role of the primary care dentist is mainly to establish a proper diagnosis and avoid unnecessary treatment, which may jeopardize the patient’s health.

Bibliography

Bates, RE, Stewart, CM. Atypical odontalgia: phantom tooth pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:479.

Campbell, RL, Parks, KW, Dodds, RN. Chronic facial pain associated with endodontic neuropathy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1990;69:287.

Dalessio, DJ, Silberstein, SD. Wolff’s headache and other head pain, ed 6. New York: Oxford University, 1996.

Delcanho, RE, Graff-Radford, SB. Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania presenting as toothache. J Orofac Pain. 1993;7(3):300.

Diamond, ML. Emergency department treatment of the headache patient. Headache Quarterly. 1992;3(suppl):28.

Fromm, GH, Graff-Radford, SB, Terrence, CF, et al. Pre-trigeminal neuralgia. Neurology. 1990;40:1493.

Fromm, GH, Sessle, BJ. Trigeminal neuralgia. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1991.

Graff-Radford, SB, Solberg, WK. Atypical odontalgia. J Craniomandib Disord. 1992;6:260.

Headache Classification Committee of the IHS. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8:1.

Loeser, JD, Butler, SH, Chapman, CR, et al. Bonica’s management of pain, ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000.

Maciewicz, R. Neurologic aspects of chronic facial pain. Anesth Prog. 1990;37:129.

Mitchell, RG. Pretrigeminal neuralgia. Br Dent J. 1980;149:167.

Moncada, E, Graff-Radford, SB. Benign indomethacin-responsive headaches presenting in the orofacial region: eight case reports. J Orofac Pain. 1995;9:276.

Moncada, E, Graff-Radford, SB. Cough headache presenting as a toothache: a case report. Headache. 1993;33:240.

Okeson, JP. Bell’s orofacial pains, ed 5. Carol Stream, IL: Quintessence, 1995.

Okeson, JP. Orofacial pain: guidelines for assessment, classification and management. Carol Stream, IL: Quintessence, 1996.

Raskin, NH. Headache, ed 2. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1988.