Management of the Hospitalized Patient

Most dentists find that they can practice without hospital facilities, but the ability to care for patients in a hospital setting adds a stimulating dimension to a dentist’s professional life.

As a vital member of a community health care team, the hospital-affiliated dentist is consulted about the dental needs of patients in the emergency room and of those admitted to the hospital by other doctors or the dentist. Dentists who join a hospital medical staff are permitted to perform dental consultations for hospitalized patients and to bring patients to the hospital to perform procedures best done there. In addition, for dentists seeking to provide care with their patients under general anesthesia, community surgery centers are often the ideal answer.

HOSPITAL GOVERNANCE

Hospital organization varies from institution to institution, but most are based on standards of The Joint Commission. The mission of this national organization is to set standards for hospitals and ambulatory care centers, to monitor these facilities to ensure that those standards are being met, and then to accredit hospitals and ambulatory centers meeting the standards.

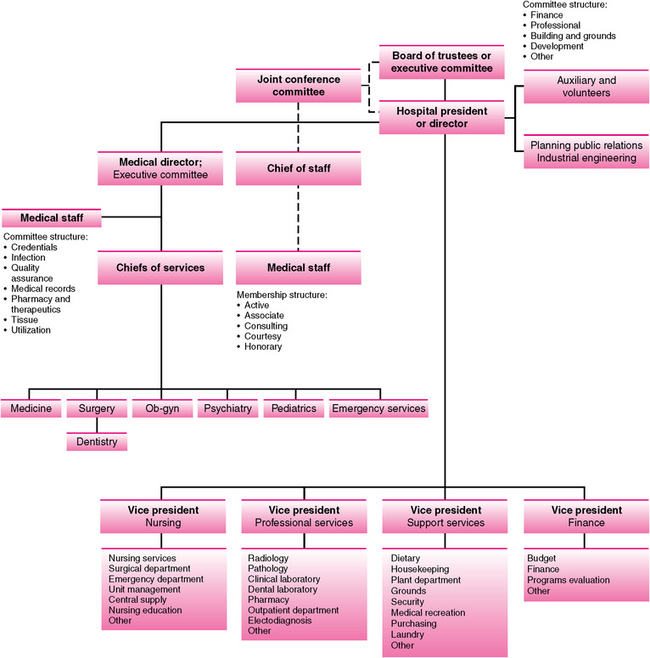

Most general, acute care community hospitals have a board of trustees that include community leaders who make up the highest governing body of the institution. These trustees are advised in health matters by a joint conference committee, which is a liaison group that includes members from hospital management, the medical staff, and the board of trustees. The hospital chief executive officer is in charge of the daily operation of the hospital and typically reports to the board of trustees. Hospital governance from this point is divided into two major organizational bodies: medical staff and hospital administration.

The medical staff includes all the health care professionals who work at the hospital. The chief of staff is the most senior governing member of the medical staff and reports to the hospital president and joint conference committee and chairs the medical board. The medical board or executive committee commonly includes the chiefs of all the medical departments of the hospital and often includes representatives from nursing and hospital administration. Dentists who join the medical staff typically become members of the dental department or division. Although at some large hospitals, dentistry is on equal footing with other major departments, such as psychiatry or pediatrics, it is more often made a division, or section, of the department of surgery, similar to other surgical disciplines, such as urology and neurosurgery. As a member of the medical staff, a dentist is usually asked to serve on committees in which dental expertise is needed, such as on infection control and oversight of the pharmacy and therapeutics.

Hospital administration is managed by the hospital chief executive officer, who has several vice presidents or assistant directors to direct various areas of hospital operations, such as nursing, support services, and finance (Fig. 31-1).

Medical Staff Membership

Membership on a hospital medical staff is not usually gained by simple request. The hospital credentials committee, consisting of physicians and dentists on the medical staff and their administrative support staff, carefully review the qualifications of doctors applying for staff membership to ensure that individuals granted privileges are competent to practice in the hospital environment and have no evidence of criminal, ethical, or other problems in their past.

Various levels of medical staff membership exist (e.g., active, associate, and courtesy), each carrying certain privileges and restrictions. Staff membership, however, never automatically gives the dentist the privilege to admit patients to the hospital or to use the operating room facilities. These privileges are granted based on a review of the applying dentist’s education and experience. Dentists who have completed a general practice residency or dental specialty training that provided hospital experience usually have little difficulty gaining medical staff membership and some admitting privileges.

However, because of hospital regulations, most dental patients admitted to a hospital by dentists other than oral and maxillofacial surgeons require a physician’s participation in the admission process.

HOSPITAL DENTISTRY

The request for consultation carries different connotations among health care professionals. To some, the consultant is only expected to render an opinion and not to begin implementing any advice until given permission by the patient’s attending physician or, in the case of the emergency room, by the patient’s designated emergency department physician. However, many physicians allow consultants to perform any test or procedure necessary to act on their opinion. Therefore the dental consultant must clarify with the requesting doctor whether only an opinion is being sought or whether the dentist can proceed to order tests and render treatment before conducting the consultation. In some cases, the consultation request form provides a section in which the requesting doctor can indicate the type of consultation desired.

Emergency Room Consultations

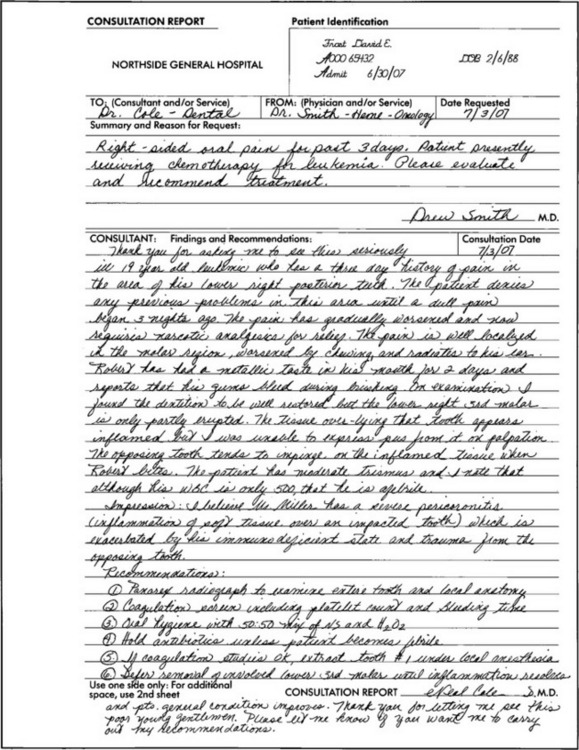

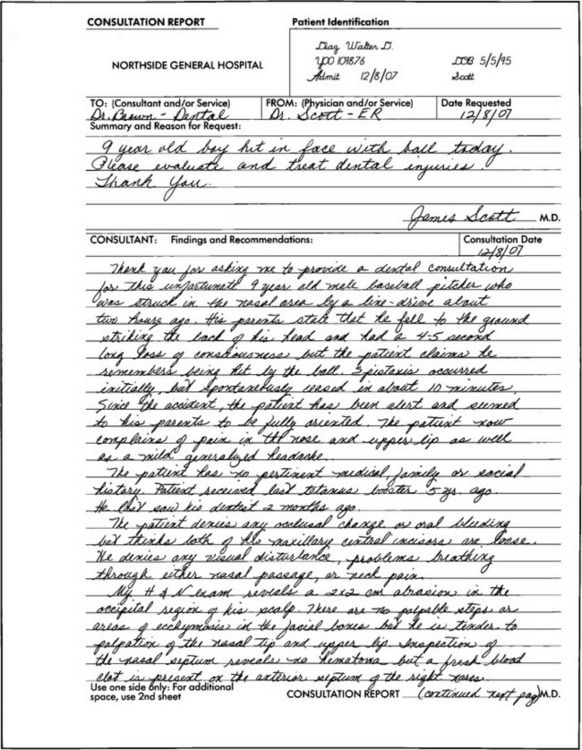

Emergency room consultations are usually requested verbally because of the urgency of the situation. The dentist should make use of any history and physical examination, laboratory, and radiographic results already available to avoid excessive duplication. However, the dentist still needs to do a careful, comprehensive history and physical examination of the oral and maxillofacial region and order special imaging as necessary to allow a complete, well-organized assessment of the patient’s dentofacial problems. All of this information is recorded in the medical record on a consultation form, in the progress notes, or in the emergency room record. A recommendation should be offered that considers other medical problems, acute or long-standing, and the urgency of the treatment. Guidelines for answering consultations are shown in Box 31-1, and a sample of a written emergency suite dental consultation is shown in Figure 31-2.

FIGURE 31-2 Example of dental consultation form written for a patient who suffered sports injury to the face. The dentist was asked to examine the patient in the hospital emergency department.

The way emergency suites are equipped for dental therapy varies. If the dentist cannot offer high-quality care in the emergency setting, the problem should be temporized and an appointment made for definitive care in the dental office. Dentists who are frequently called to hospital emergency rooms sometimes find it useful to carry in their car a set of instruments and supplies necessary for initially handling common oral emergencies.

If more than one dentist serves as a dental consultant to an emergency room, a call schedule is usually established to designate, on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis, which dentist is expected to be available in case of an emergency. When on call, the dentist should keep the hospital aware of how to be contacted quickly.

Inpatient Consultations

Dental consultation for a hospitalized patient is similar to consultations for emergency room patients: the dentist is expected to evaluate the oral and maxillofacial region, offer an assessment, and formulate a dental treatment plan that considers the overall clinical situation. Dental consultation requests should be written on standard hospital consultation forms or in the appropriate portion of the electronic medical record on which the requesting physician states the question or questions to be answered by the dental consultant. The requesting doctor should also provide a brief statement of other active problems the patient may have. If a dentist receives an unwritten or unclearly written consultation request, the dentist should make an effort to clarify what is desired. The dentist should make every attempt to answer all consultation requests within 12 to 24 hours.

The recorded results of consultations should be sufficiently complete to document all significant findings (positive and negative). The assessment should read as a concise dental problem list, and the treatment plan should be clearly recorded, with an indication of the priority and urgency of any necessary care. The terms used should be those physicians and nurses can understand, rather than technical dental terms. Excessive verbiage should be avoided. If the dentist finds it impossible to finish the evaluation without additional tests, arrangements should be made to obtain necessary tests in the near future, and a preliminary consultation note should be made to inform the requesting physician of the findings and preliminary recommendations. After seeing the patient, it is good practice to call the physician who requested the consultation to inform the physician of the findings and recommendations. However, it is still necessary to record a formal answer directly on the consultation form or on a progress note or in the electronic medical record, with an indication in the response of where the answer has been written. In addition, if the consultation request asks for care to be provided, the dentist should carefully document that care. In addition, as in any care provided in the hospital setting, the dentist should collect enough data about the patients to allow the office staff to bill properly for services rendered. Codes for such care and consultations are available in standard medical coding manuals. An example of a dental consultation form is presented in Figure 31-3.

Requesting a Consultation

When a patient has a problem the dentist does not feel qualified to evaluate or manage alone, a formal consultation request can be made. When requesting a medical consultation, the dentist should indicate whether the consultant is free to order necessary tests and to proceed with any necessary treatment. Preferably, the requesting dentist should personally call to ask the consultant for an opinion. Alternatively, an order can be written directing a hospital clerk to call the consultant’s office.

A consultant’s recommendations should be viewed as an educated opinion. A dentist is under no obligation to follow a consultant’s advice in its entirety or at all. The patient’s attending doctor must make the final decision of which diagnostic tests to perform and what care the patient will receive, including when the attending doctor is a dentist.

Hospitalizing Patients for Dental Care

The vast majority of patients needing routine dental care, including oral and maxillofacial surgery, can be safely managed in the dental office. However, occasionally some patients require that dental care be provided in a hospital or surgery center.

A patient may be better treated in a hospital for several reasons. One of the most common reasons is behavioral management. Patients unable to cooperate (e.g., because of mental retardation), unwilling to cooperate (e.g., uncontrollable children), or who refuse dental care while awake can be deeply sedated or placed under general anesthesia; this allows routine dental care to be delivered to these individuals quickly and safely. An operating room setting for dental treatment may also be necessary for the physically handicapped patient who is unable to gain access to a dental office or is unable to remain relatively motionless during procedures.

An operating room is also often needed to provide dental care for patients with high-risk medical conditions, such as patients requiring care that cannot be delayed until the medical condition is alleviated or improved, or patients requiring emergency dental care shortly after a serious myocardial infarction. In some cases a patient’s physician may be able to provide guidance as to the safety of office-based dental care. A final reason for planning a procedure in an operating room is for patients in whom acceptable local anesthesia cannot be attained, such as those requiring care on teeth in an area of severe infection. Usually these patients are best referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, but hospitalization may be an alternative if the dentist feels capable of managing the surgical problem.

Day Surgery Facilities

In the past, operating room facilities were available only in hospitals, and patients had to be admitted the day before dental surgery and remain in the hospital until the dentist believed discharge was indicated (commonly 1 to 2 days postoperatively). However, changes have occurred in methods of delivering operating room care. Free-standing or hospital-based surgical centers now exist that offer staffed operating and recovery rooms and anesthesiologists for patients not needing preoperative or postoperative hospitalization. Many hospitals also offer the use of their operating room and staff without requiring hospital admission. A dentist may find that many patients unable to be cared for in the dental office can be effectively treated in day surgery facilities without hospitalization.

Preoperative Patient Evaluation

Once the decision to use an operating room facility has been made, several steps must be taken before the operation. The operating room staff must be contacted, and the operating time scheduled. Most facilities need some biographic information about the patient, the reason for the procedure, the procedure planned, who will perform the procedure, how long the operating room will be in use, the type of anesthesia required (i.e., sedation only or general anesthesia), and whether special equipment will be required. A hospital-based operating room must also know whether the patient will be admitted; patients to be admitted must have a room reservation made and an estimated length of stay.

All operating room facilities require that a medical history and physical examination be performed before the operation. See Chapter 1 for guidelines for recording the history and physical examination results in the medical record. This recording can be performed by the patient’s physician before the day of the operation or, in some facilities, by the anesthesiologist during the preanesthetic consultation. Most facilities also require that any medically indicated laboratory tests, radiographs, or electrocardiograms be done at a time proximate to the surgery. Requirements vary from place to place, but the usual minimal testing necessary is a hematocrit.

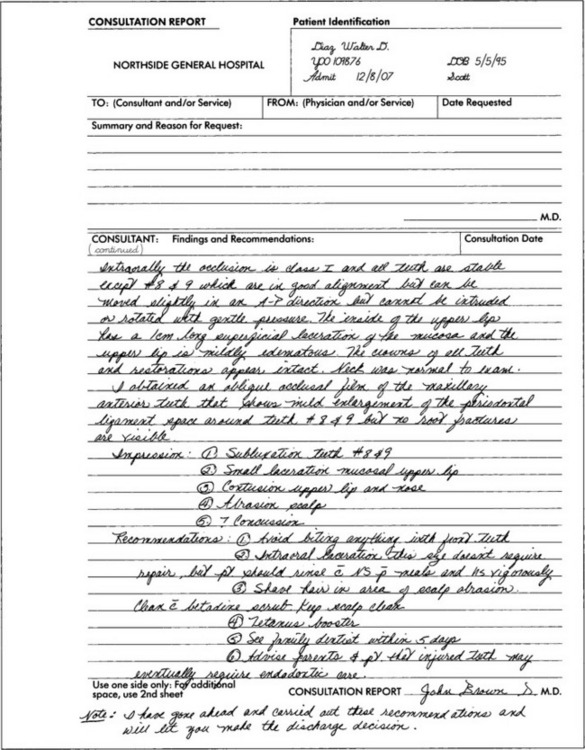

“Doctor’s orders” communicate patient care instructions to nurses and other hospital staff members. The dentist’s orders should be accurate, clearly written if not using an electronic medical record, and comprehensive.

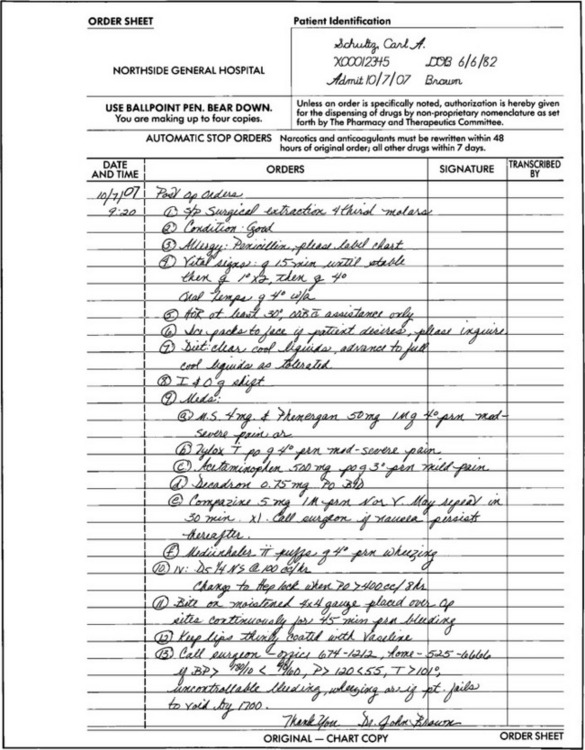

Preoperative orders are necessary for patients being admitted to a hospital or scheduled to be treated in an operating room without hospital admission. Orders are best written by the dentist but may be given to nurses over the telephone (dentists must eventually sign telephone orders). An example of admission and preoperative orders is given in Figure 31-4.

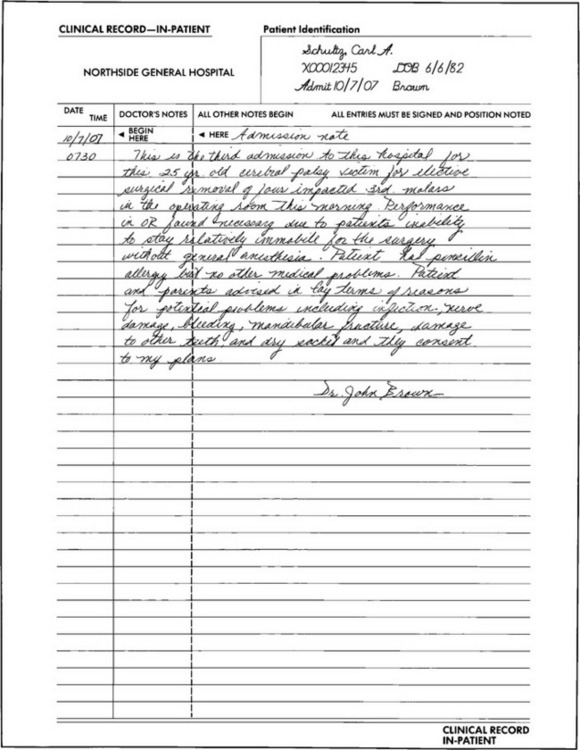

FIGURE 31-4 Example of admission preoperative doctor’s orders written for patient with cerebral palsy admitted to hospital on day of third molar surgery. Because patient is coming to hospital on day of surgery, admission orders and preoperative orders can be combined.

Before surgery the operating dentist should place a note in the patient’s record that briefly describes the nature of the patient’s medical and dental problems and the expected operating room and hospital course. The hospital staff can then use this note to familiarize themselves with the patient’s general condition and reason for admission (Fig. 31-5).

Care of Hospitalized Patient

The patient’s operating dentist bears the ultimate responsibility for any mishaps that occur in the operating room other than those relating to duties relegated to anesthesiology. Therefore the dentist must be meticulous in monitoring all that is done to the patient and should take charge if anything is being done that may harm the patient.

The operating team usually consists of the operating surgeon and an assistant. The assistant should have sufficient familiarity with the planned procedure to help the dentist by suctioning, retracting, and cutting sutures. Many hospitals allow the dentist to bring an office assistant to assist in the operating suite. Anesthesia may be provided by an anesthesiologist (a medical physician) or by an anesthetist (a nurse with special training in anesthesiology who usually must work under an anesthesiologist’s supervision). A scrub nurse, who is sterilely gowned and gloved, passes instruments to the surgeon during the procedure and, among other duties, keeps track of the sponges and needles used. The circulating nurse remains ungowned and assists in setting up equipment, retrieving supplies, and completing nursing records of the operation.

The dentist should try to see the patient in the preoperative area before anesthetic premedication to help clarify any final questions the patient may have, learn whom the patient wants notified at the completion of the operation, and give emotional support to the patient.

During final preanesthetic patient preparation, the dentist should review the operative plans with the anesthesiologist. These plans include surgical site, length of procedure, oral hazards (e.g., loose teeth or restricted opening), route of intubation desired, and whether the patient will be admitted to the hospital. The dentist should remain near the patient’s head during intubation to assist if necessary.

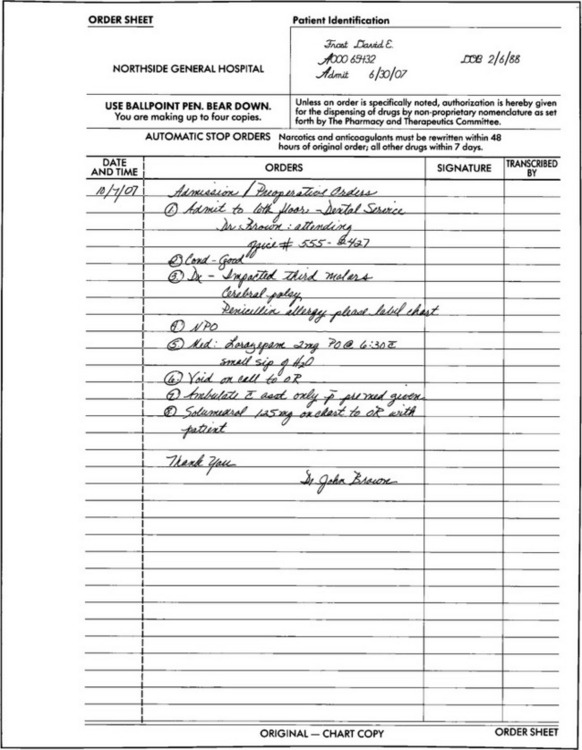

Once the patient is under general anesthesia, the dentist should ensure that steps are taken to prevent accidental injuries. Dental patients are usually operated on in a supine position, with the head end of the operating table raised about 15 degrees. The extremities must be placed in physiologic positions (i.e., positions patients would find comfortable for long periods if they were not anesthetized). Proper positioning helps prevent nerve injuries and excess loading of any part of the anatomy. In addition, padding should be placed in any area of pressure concentration, such as under heels and around elbows, particularly if the dental procedure is likely to last longer than 1 hour. Most hospitals currently place all patients on foam or gel-filled cushions or air mattresses during surgery to help prevent pressure sores. The head should be placed on a contoured cushion to help prevent excessive movement of the head during surgery.

Patient protection during anesthesia is also provided by several other means. If the procedure is expected to last more than 4 hours, a urinary (Foley) catheter should be placed to prevent overdistention of the bladder. The anesthesiologist may want this done even for shorter operations to monitor urinary output. If an electrocautery unit will be used, a grounding pad must be placed. To protect the patient’s eyes, a lubricating ointment should be applied and the eyelids should be taped closed. Patients who are intubated nasally require close attention to proper tube stabilization; tubes that place excess pressure on the nasal alar cartilage can easily cause pressure sores that result in an unsightly deformity (Fig. 31-6).

FIGURE 31-6 Preparing (prepping) patient for operating room oral and maxillofacial surgery. A, Surgeon helps anesthesiologists by guiding placement of tubes and tapes used to secure tubes. Surgeon also helps hold the patient’s head to help stabilize while the device is placed behind the patient’s head. B, Patient before draping, with padding of pressure points. Nasoendotracheal tube is supported to prevent alar damage, eyes are lubricated, pads are placed to protect eyes, and then eyes are covered with a towel. An antiseptic solution is applied on face to reduce number of bacteria not indigenous to patient’s facial region. C, Same patient after draping is complete. Only the operative site is exposed.

The final step before surgery is preparation of the patient’s operative site. If necessary, any facial hair can be shaved. Then the skin in the maxillofacial and anterior neck regions should be prepared by scrubbing with a soap-containing solution and painting with a disinfecting solution, such as iodophor. The patient is then draped with two layers of linen material or one layer of waterproof paper material to cover all portions of the body except the operative site. The oral cavity is prepared for the procedure by first gently suctioning the pharynx, placing a moist throat pack, and using large volumes of irrigation solution to help decrease the bacterial count by dilution. The use of a sterile toothbrush and chlorhexidine improves the effectiveness of oral cavity preparation. The anesthesiologist and circulating nurse should be asked to make a note that the throat has been packed so they can help remind the surgeon to remove the pack after the surgery is complete. Local anesthesia is typically administered even when patients will be under general anesthesia to help lessen the amount of general anesthetic drugs required and delay the onset of postoperative discomfort.

Dental Surgeon and Assistant Preparation

The dental surgeon prepares for surgery by first checking that all instruments and patient records required to perform the surgery successfully are available. This preparation should be done before the day of surgery if the dentist does not regularly use a particular facility (in case any essential equipment or records must be brought from the surgeon’s office on the day of surgery).

Before entering the operating room suite, the surgical team changes from street clothes into surgical scrub uniforms in a locker room. Shoes worn outside of the operating suite are covered with shoe covers. Scalp hair is covered with a cap. Members of the surgical team with long beards should wear head covers that extend across the chin and anterior neck. All jewelry, including watches, rings, necklaces, and earrings, should be removed before scrubbing. A mask that covers the nose and mouth should be tied in place before the surgeon enters the operating room. Before the surgical scrub, the surgeon should check the patient’s records, place radiographs on the view box, adjust overhead lights, check the patient’s position, apply defogging solution to eyeglasses, and adjust the headlight.

The surgical hand and arm scrub is then performed to lessen the chance of contaminating a patient’s wound. Although sterile gloves are worn, gloves are frequently torn during oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures, thereby exposing the patient to the surgeon’s skin. By proper scrubbing with antiseptic solutions, the hand and arm bacterial counts are reduced.

Several acceptable methods may be used to perform a surgical hand and arm scrub. Most hospitals have a surgical scrub protocol that should be followed when doing surgery. Standard in most techniques is the use of an antiseptic soap solution, a moderately stiff brush, and a fingernail cleaner. The hands and forearms are wetted in a scrub sink, keeping the hands above the level of the elbows until the hands and arms are dried. A copious amount of antiseptic soap from a wall dispenser or from an antiseptic-impregnated scrub brush is applied to the hands and arms up to the elbows. The antiseptic soap is allowed to remain on the arms, while all visible debris is removed from underneath each fingernail tip with the sharp-tipped fingernail cleaner. Then more antiseptic soap is applied and scrubbing is begun using repeated firm strokes of the scrub brush on every surface of the hands and arms, stopping about 5 cm below the elbow (Fig. 31-7). Scrub techniques based on the number of strokes to each surface rather than a set time for scrubbing are more reliable. An individual’s scrub technique should follow a set routine designed to ensure that all forearm and hand surfaces are properly prepared. However, scrubbing too long and too firmly can be as detrimental as inadequate scrubbing because skin that is excessively traumatized by scrubbing develops a much higher resident bacterial flora. Once scrubbing is completed, the hands and forearms should be rinsed free of soap solution under running water, moving the arm through the stream from fingertips to elbow. The hands must be kept higher than the elbows during the entire scrub and rinse to allow all excess fluid to drip off the arm at the elbow.

FIGURE 31-7 Technique of hand scrubbing used before gowning and gloving for surgical procedure. A and B, Disposable antiseptic-impregnated scrub brush and nail cleaner are taken out of package, and hands are wetted in scrub sink. While holding scrub brush in one hand, surgeon uses nail cleaner under each fingernail. Nail cleaner is then discarded and scrubbing commences. For conservation, water only turned on when needed. C, Both arms are lathered with antiseptic soap from fingers to area about 5 cm below elbows. Scrub brush is then used to scrub all surfaces of hands and forearms thoroughly, with most brush strokes on each surface of each hand (20 per surface) and fewer strokes on each surface of forearms (10 per surface). D, After scrubbing is completed, brush is discarded and arms are rinsed completely. During rinsing, arm is put through the water, starting at fingertips, then pushing through to elbow. E, Arms are then allowed to drain for several seconds over scrub sink. During scrubbing and rinsing, hands and forearms are kept raised above level of elbows until scrub gown is in place.

Once scrubbing is completed, the surgeon should enter the operating room, taking care to avoid contaminating scrubbed hands and arms. Drying commences with a sterile towel handed to the surgeon by the scrub nurse. The towel is held in one hand to dry the other hand, advancing up the forearm and stopping short of the elbow. The towel is then transferred to the dry hand, and the process is repeated on the wet hand with an unused portion of the towel. Next, the scrub nurse fully opens the sterile surgical gown, and the surgeon introduces the hands into the openings for the arms of the gown.

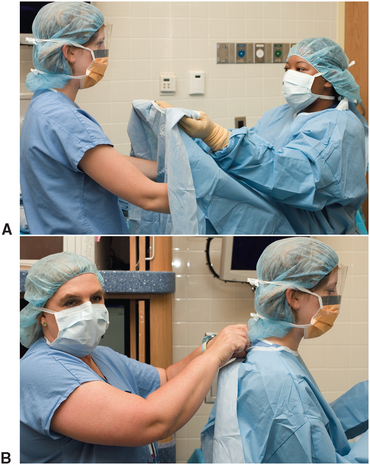

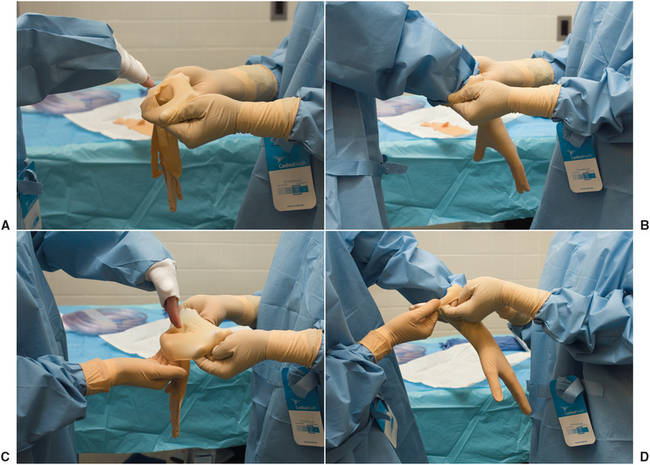

While the scrub nurse helps push the gown up the surgeon’s arm, the circulating nurse pulls the gown on from the rear of the surgeon and ties it securely (Fig. 31-8). The scrub nurse then holds the surgical gloves open while the surgeon places one hand into each glove. The gloves should completely cover the hands and wrists and completely overlap the cuff of the surgical gown (Fig. 31-9). The surgeon must not allow the hands to fall beneath waist level from this point until ungowning (Fig. 31-10).

FIGURE 31-8 Gowning for operating room surgery. A, Scrub nurse holds sterile gown open for surgeon to place arms into sleeves. The scrub nurse has hands on front side of gown to prevent possibility of accidentally touching ungowned surgeon. Surgeon pushes arms into sleeves of gown, taking care not to thrust through cuff of gown, potentially contaminating scrub nurse. While surgeon is placing arms into sleeves, scrub nurse is pushing gown onto surgeon. B, Unsterile circulating nurse then ties back of surgeon’s gown, taking care to touch only inside surfaces of gown.

FIGURE 31-9 Gloving for operating room surgery. A, Scrub nurse holds open first glove to allow surgeon to insert hand into glove while surgeon’s wrist is in flexion. Surgeon pushes hand into glove with fingers adducted, while nurse pulls glove onto surgeon’s hand. B, Once surgeon’s hand is into palm region of glove, fingers are partially abducted and slipped into appropriate finger holes. Nurse continues to pull glove on until cuff of glove is above cuff of surgeon’s gown. Nurse then releases glove. No further adjustments of first glove are made at this time. C, Scrub nurse then holds second glove open in same manner that first glove was presented to surgeon. Surgeon can now help hold cuff of glove open while inserting other hand. D, Hand being gloved is pushed into glove while other hand assists nurse in pulling glove into place. Once both gloves are in place, they can be used to adjust each other, pulling all slack out of area of fingertips.

Postoperative Responsibilities

Once the operative procedure is completed, the oral cavity is again irrigated and cleared by suction of the accumulated fluids. Before throat pack removal, the scrub nurse should be asked whether all sponges and needles used during the surgery are accounted for; if they are not, a search must be made to find them. If necessary, intraoral gauze packs should be placed for hemostasis, and the packs should have long ends that trail out of the mouth for easy retrieval.

Nurses (under the supervision of anesthesiologists) make many of the immediate postoperative decisions in the postanesthesia care unit. However, the dentist should write postoperative orders immediately after the completion of surgery to ensure that any special instructions can be initiated in the postanesthesia care unit.

Postoperative orders should include statements of the diagnosis, procedure performed, patient allergies, and general condition of the patient after surgery. Nursing actions, such as vital sign monitoring, wound care, and medication administration schedule, should be clearly spelled out. The patient’s diet, activity level, bed positioning, and allowable personal hygiene should be delineated. Finally, parameters should be outlined that, if breached, make immediate notification of the dentist or physician mandatory. An outline for postoperative orders is listed in Box 31-2; a sample of postoperative orders is shown in Figure 31-11.

FIGURE 31-11 Example of postoperative orders written after removal of third molars in operating room.

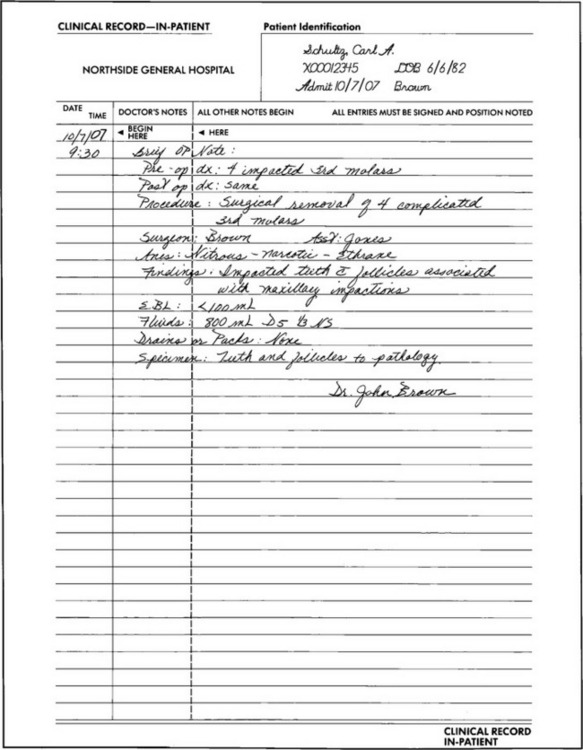

Shortly after the surgical procedure is completed, a brief operative note should be placed in the patient’s record. This note is usually in a relatively standard format that includes listing the preoperative and postoperative diagnoses, the names of the procedures performed during surgery, the name or names of the surgeon or surgeons, the type of anesthesia, the placement of any drains, the estimated blood loss, and whether any specimens were sent for pathologic examination. The hospital staff uses this note to learn quickly the general information about the operative procedure.

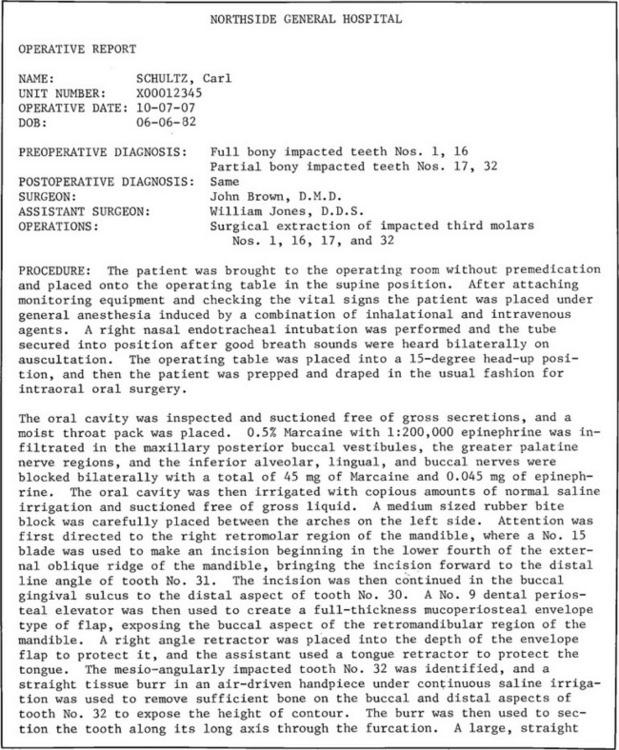

In addition, before leaving the operating suite, a full report of the operation should be dictated using the designated format of the facility at which the surgery was performed. The general outlines and examples of a brief operative note and transcribed operative report are shown in Boxes 31-3 and 31-4 and in Figure 31-12.

FIGURE 31-12 A, Example of brief operative note for quick documentation in hospital record of what was performed, whether in operating room or elsewhere in hospital. B, Example of dictated operative note to describe in detail exact procedure performed in operating room.

Patients generally remain in the postanesthesia care unit until they are sufficiently alert and unlikely to injure themselves and their vital signs are stable within acceptable limits. An anesthesiologist usually makes the decision about discharge to a hospital room or home, unless it is specified that the dentist will make that decision. The discharged patient should be placed directly under the care of a competent adult and not be allowed to go home unescorted.

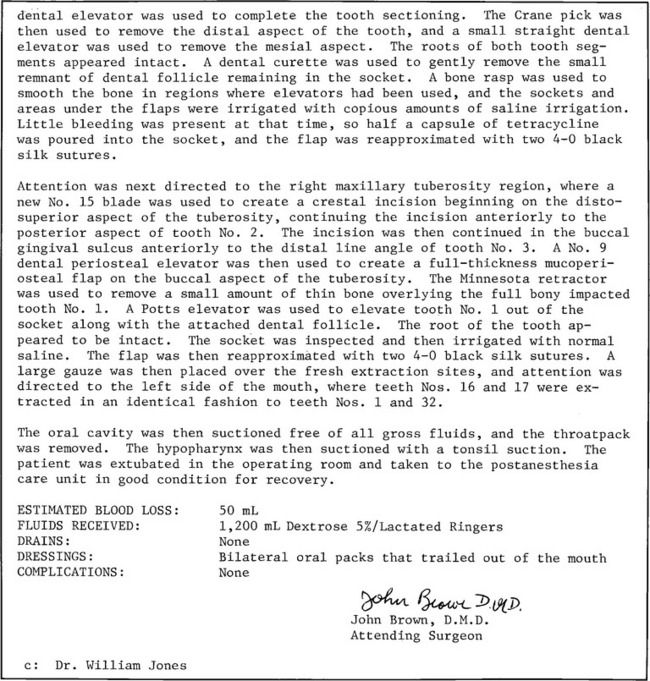

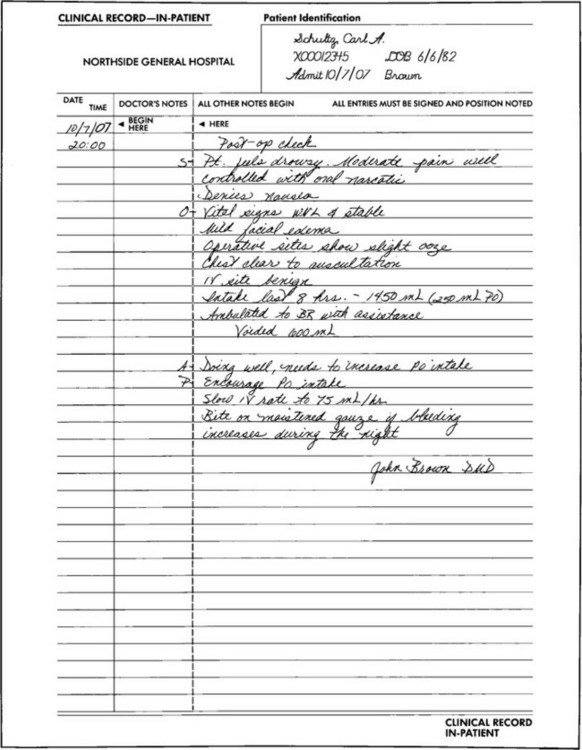

Hospital rounds (i.e., patient visits) give the surgeon the opportunity to check the patient’s postoperative recovery personally and to revise orders as necessary. Unstable hospitalized patients require frequent visits; stable patients are usually seen twice a day during the first week after surgery and once daily thereafter. Each patient visit by the surgeon warrants a brief notation (i.e., progress note) in the record that documents the patient’s progress and any new plans for further care. Notes are usually written using a record format that includes a brief description of how the patient is progressing subjectively and objectively, an assessment of the patient’s condition, and a plan for further care (SOAP). Figure 31-13 shows a typical postoperative progress notation in the SOAP format.

FIGURE 31-13 Example of hospital progress note made to document patient’s course in hospital and to inform others of future plans for patient. Note SOAP format used: S is any comments made by patient (subjective), O is objective findings by dentist, A is assessment by dentist of how patient is doing, and P is plans for future care.

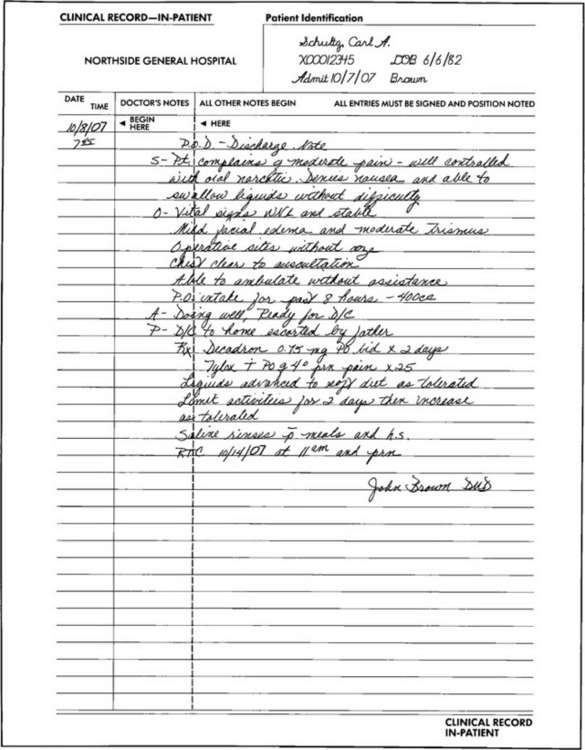

Discharge planning should begin as soon as the surgical procedure is completed and includes making arrangements for any necessary patient education, such as oral hygiene, wound care, and dietary instructions. In addition, the patient should be told of acceptable activity levels and plans for follow-up office visits. Necessary prescriptions for medications should be provided, as well as instructions on how to contact the appropriate physician or dentist should problems arise. A written discharge note should be included in the progress note section of the medical record (Fig. 31-14 and Box 31-5).

FIGURE 31-14 Example of written discharge note in SOAP format to document patient’s progress. Discharge instructions are documented under P.

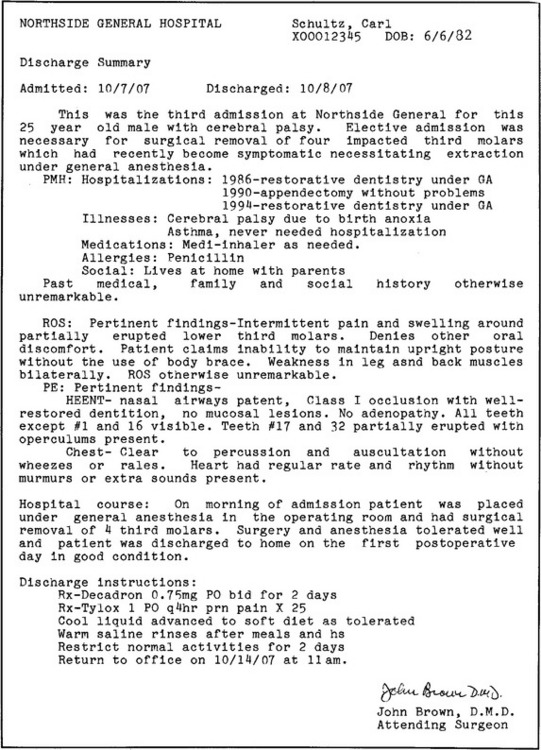

A dictated discharge summary is necessary for hospitalized patients, whereas surgical centers generally accept a written discharge summary on a special form. The dictated summary should include a brief narrative, including the reason for hospital admission and the pertinent history that led to admission. The significant positive and negative findings of the history and physical examination should be described, including any laboratory results. The hospital course, including the name of the operative procedure, should be in the summary. Finally, discharge instructions, prescriptions, and follow-up appointments should be detailed in the report. Arrangements should be made to send copies of the discharge summary to other doctors who may find the information useful, including the patient’s family physician (Fig. 31-15 and Box 31-6).

Management of Postoperative Problems

Routine dentoalveolar surgery is unlikely to cause airway compromise unless a condition such as Ludwig’s angina is present. However, patients in whom an endotracheal tube has been placed during general anesthesia are at risk for postextubation (i.e., after removal of the endotracheal tube) airway narrowing or obstruction, which is caused by trauma to the mucosal lining of the upper respiratory tract that produces edema. The narrowest portion of the upper respiratory tract is the region of the vocal cords through which the endotracheal tube must be passed and on which the tube rests during anesthesia. The amount of respiratory tract mucosal injury depends on the patient’s anatomy, the size of tube used, the type of tube, and care used during placement. Injuries caused by tube type have been lessened by the use of tubes with high-volume, low-pressure cuff designs. Patients generally do well after extubation, except for mild to moderate throat discomfort during swallowing for 1 to 2 days. However, occasionally, laryngeal edema of sufficient severity to compromise the patient’s ability to breathe is produced. The first symptom is usually a crowing sound during attempts to inspire and expire. The patient may also need to use accessory muscles of respiration to force air through the cords.

Prevention of airway trauma is the best form of care. If trauma is known to have occurred during intubation or extubation (or in patients having prolonged intubation), postoperative orders should include the delivery of cooled, humidified air or oxygen, administration of racemic epinephrine through an aerosol, and placement of tracheotomy equipment near the patient’s bed. These patients should be closely monitored, preferably under close supervision by an anesthesiologist, until the dentist is comfortable that airway problems are under control.

Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting occur commonly after general anesthesia, which is part of the rationale for fasting patients preoperatively. The symptoms are primarily related to anesthetic drugs and occasionally to excessive air that might have been forced into the stomach during induction of anesthesia. Nausea and vomiting usually resolve with time but can be a serious problem if the patient is not fully in control of laryngeal reflexes, is in intermaxillary fixation, or is unable to begin taking needed medications and sustenance orally. Swallowed blood can also stimulate nausea and vomiting.

Vomiting in a patient with depressed reflexes is best handled by placing the patient in a horizontal position on the right side until reflexes are recovered. Patients in intermaxillary fixation but with normal airway reflexes should be able to eliminate any vomitus through the nose and mouth because postoperative stomach contents should be of liquid consistency. Even so, constant retching can disrupt a properly set facial fracture or a delicate wound repair, so awake patients in or out of fixation may need to receive antiemetic medications to relieve nausea. However, before giving antiemetic agents, the possibility of depressed gastrointestinal motility or brain injury should be ruled out. If a patient develops airway problems while in intermaxillary fixation, an instrument capable of releasing fixation should be readily available. Many dentists have a pair of wire cutters taped to the head of a patient’s bed.

Fever

Fever is generally defined as an oral temperature of greater than 99° F (37.2° C) or rectal temperature higher than 99.8° F (38° C). A postoperative fever may be produced by a variety of factors. However, based partially on when in the postoperative period fever occurs, it may be attributed to one of a few common causes. For example, fever the night after surgery is usually attributed to bacteremias resulting from organisms in surgical wounds. Fevers occurring in the first or second postoperative day after general anesthesia or major surgery are generally attributed to insufficient depth of breathing, which produces atelectasis (collapse of terminal lung alveoli), or, less commonly, to dehydration. Fever 2 days after surgery can be an early sign of a wound infection or, if the patient had the bladder catheterized or has prolonged atelectasis, it may be caused by a bladder infection or pneumonia.

No matter when a fever arises, an investigation should be undertaken to discover the cause. The patient should be questioned about wound pain, swelling, foul taste, productive cough, and dysuria. On examination, particular reference should be made to the surgical wound, sites of intravenous (IV) catheters, and lungs. Studies such as a white blood cell count, urinalysis, and chest radiographs may be useful in determining an explanation for a postoperative fever, if clinically indicated. A medical consultation may be necessary if a cause for a persistent fever remains obscure. Once it is documented that a fever exists, the patient’s symptoms and increased metabolic expenditure from the fever can be lessened by administration of acetaminophen.

Atelectasis

Atelectasis is a common problem in patients who have undergone abdominal surgery and fail to fill their lungs to normal capacity because of the incisional pain provoked by deep breathing. In patients who have had dentoalveolar surgery under general anesthesia, atelectasis can result from (1) inactivity that allows the patient to breathe without filling the lungs to normal capacity; (2) postoperative narcotic analgesics that depress the sigh reflex, which normally functions to prevent atelectasis; or (3) an endotracheal tube misplacement so that only one lung was aerated during surgery.

Prolonged atelectasis can lead to pneumonia; thus prevention of atelectasis is important. Instructing patients to take deep sustained inspirations periodically during the postoperative period and to begin ambulation as soon as possible after surgery lessens the possibility of developing atelectasis. Limiting the use of unnecessarily large doses of narcotic analgesics can also prevent atelectasis.

Fluids and Electrolytes

Hypovolemia can be found in patients after surgery because of insufficient fluid intake to match fluid loss. Fluids are lost through the obvious routes of urination, vomiting, and nasogastric suctioning, as well as by insensible routes, such as expired air and perspiration. The primary source of replacement fluids is normally oral ingestion. However, postoperative patients who are unable or unwilling to maintain necessary fluid intake orally require IV supplementation until oral fluid intake resumes. The usual volume of fluid intake necessary (combination of oral and IV) for a nonfebrile adult in the postoperative period is between 2500 and 3000 mL daily, with a higher volume for patients with higher-than-normal fluid loss and a lower volume for patients susceptible to fluid overloading, such as those with renal or myocardial insufficiency.

The choice of IV fluid type is based on the knowledge that human serum must have certain electrolytes kept within a narrow range to maintain vital physiologic functions. Sodium, potassium, and chloride are the three electrolytes considered when choosing an IV solution. Three standard IV crystalloid solutions are available for use individually or in combination. Dextrose 5% in water is a 5% glucose solution that provides free water, a source of calories in a fluid that is isotonic with plasma, and no electrolytes. Normal saline, or 0.9% sodium chloride solution, provides 154 mEq each of sodium and chloride per liter of water, which makes the solution roughly isotonic but actually functions to draw interstitial fluid into the intravascular compartment.* Lactated Ringer’s solution contains generally physiologic electrolyte concentrations (Na+, 130 mEq; Cl−, 109 mEq; K+, 3 mEq) and lactate, which buffers serum acidity by providing a substrate that can be metabolized into bicarbonate.

In general, the otherwise healthy patient requires a relatively physiologic IV solution with some calories during and after surgery, which can be provided by combination crystalloid solutions, such as 5% dextrose in a 0.45% sodium chloride solution to which 20 mEq of potassium chloride per liter has been added. Patients with special medical problems likely to cause electrolyte abnormalities, such as those receiving potassium-wasting diuretics or prolonged IV fluid infusions, will need their serum electrolytes monitored to guide IV fluid choice.

Blood Component Transfusion

Blood transfusions are rarely required after dentoalveolar surgery, which is fortunate because of the potential for spread of infectious diseases in the course of transfusions and the risk of incompatibility reactions. The primary reason why transfusions are unnecessary is the nature of oral surgery, which if properly performed, is unlikely to allow significant blood loss. In addition, placement of patients in reverse Trendelenburg’s position* and the use of hypotensive anesthetic techniques have further lessened blood loss.

Occasionally, circumstances arise in which blood components are necessary, such as for trauma patients who have lost blood from serious injuries or patients with thrombocytopenia. In the past, patients requiring transfusions were given whole blood; however, modern blood banks currently separate donated blood into its various components (i.e., plasma, red blood cells, platelets, and white blood cells). Patients with a low hematocrit and therefore lowered oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood can be given only the portion of blood that they require—packed red blood cells. Similarly, patients who are thrombocytopenic from chemotherapy but require emergency oral surgery can be given platelet concentrates.

Another means of transfusion therapy—autogenous blood transfusion—is available in most centers. This technique is used when it is suspected that an intraoperative blood transfusion may be required. Patients can donate a unit of their own blood before surgery. The blood is then stored and made available for their personal use during surgery.

Various criteria exist to help determine when red cell or platelet transfusions are necessary. In general, a healthy patient with normal red cell mass can tolerate an acute fall in hematocrit to 25% to 30% without suffering significant ill effects. A chronically anemic patient can easily tolerate an even lower concentration of red blood cells. Dentists managing patients with thrombocytopenia should seek the advice of a hematologist when deciding whether platelet transfusion is warranted.