Preoperative Health Status Evaluation

The extent of the medical history and the physical examination and laboratory evaluation of patients requiring ambulatory dentoalveolar surgery differs from that necessary for a patient requiring hospital admission for surgical procedures. A patient’s primary care physician typically performs comprehensive histories and physical examinations of patients; it is impractical and of little value for the dentist to duplicate this process. However, the dental health care provider must discover the presence or history of medical problems that may affect the safe delivery of care, as well as any conditions specifically affecting the health of the oral and maxillofacial region.

Dentists are educated in the basic sciences and preclinical medical sciences, particularly as they relate to the maxillofacial region. This special expertise in medical topics as they relate to the oral region makes dentists valuable resources in a community health care delivery team. The responsibility that this designation carries is that dentists must be capable of recognizing and appropriately managing pathologic oral conditions. To maintain this expertise, a dentist must keep informed of new developments in medicine, be vigilant when treating patients, and be prepared to communicate a thorough but succinct evaluation of the oral health of patients to other health care providers.

MEDICAL HISTORY

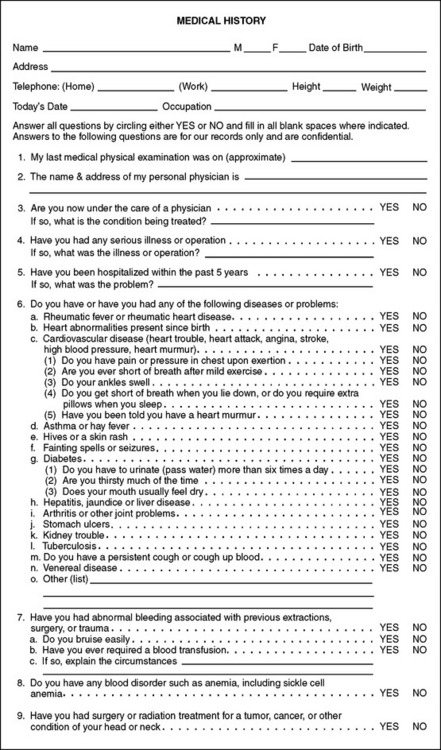

An accurate medical history is the most useful information a clinician can have when deciding whether a patient can safely undergo planned dental therapy. The dentist must also be prepared to predict how a medical problem will alter a patient’s response to planned anesthetic agents and surgery. If obtaining the history is done well, the physical examination and laboratory evaluation of a patient usually play minor roles in the presurgical evaluation. The standard format used for recording the results of medical histories and physical examinations is illustrated in Box 1-1.

The medical history interview and the physical examination should be tailored to each patient, considering the patient’s medical problems, age, intelligence, and lifestyle; the complexity of the planned procedure; and the anticipated anesthetic methods.

Biographic Data

The most important information to obtain initially from a patient is biographic data. These data include the patient’s full name, address, age, gender, and occupation, as well as the name of the patient’s primary care physician. The clinician uses this information, along with an impression of the patient’s intelligence and personality, to assess the patient’s reliability. This is important because the validity of the medical history provided by the patient depends primarily on the reliability of the patient as a historian. If the identification data or patient interview gives the clinician reason to suspect that the medical history will be unreliable, alternative methods of obtaining the necessary information should be found. A reliability assessment should continue throughout the entire history interview and physical examination, with the interviewer looking for illogical, improbable, or inconsistent patient responses that might suggest the need for corroborating information.

Chief Complaint

Every patient should be asked to state the chief complaint. This can be accomplished on a form the patient completes, or the patient’s answers should be transcribed (preferably verbatim) into the dental record during the initial interview by a staff member or dentist. This statement helps the clinician establish priorities during history taking and treatment planning. In addition, by having patients formulate a chief complaint, one encourages them to clarify for themselves and the clinician why they desire treatment. Occasionally a hidden agenda may exist for the patient, consciously or subconsciously. In such circumstances, subsequent information elicited from the patient interview may reveal the true reason the patient is seeking care.

History of Chief Complaint

The patient should be asked to describe the history of the present complaint or illness, particularly its first appearance, any changes since its first appearance, and its influence on or by other factors. Descriptions of pain should include onset, intensity, duration, location, and radiation, as well as factors that worsen and mitigate the pain. In addition, an inquiry should be made about constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, lethargy, anorexia, malaise, and weakness associated with the chief complaint.

This portion of the health history may be straightforward, such as a 2-day history of pain and swelling around an erupting third molar. However, the chief complaint may be relatively involved, such as a lengthy history of a painful, nonhealing extraction site in a patient who received therapeutic irradiation. In this case a more detailed history of the chief complaint is necessary.

Medical History

Most dental practitioners find health history forms (questionnaires) to be an efficient means of initially collecting the medical history. When a credible patient completes a health history form, the dentist can use pertinent answers to direct the interview. Properly trained dental assistants can “red flag” important patient responses on the form (e.g., circling allergies to medications in red) to bring positive answers to the attention of the dentist.

Health questionnaires should be written clearly, be in lay language, and not be too lengthy. To lessen the chance of patients giving incomplete or inaccurate responses and to comply with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, the form should include a statement that assures the patient of the confidentiality of the information and a consent line identifying those individuals the patient approves of having access to the dental record, such as the primary care physician and other clinicians in the practice. The form should also include a place for the patient signature to verify that the patient has understood the questions and the accuracy of the answers. Numerous health questionnaires designed for dental patients are available from sources such as the American Dental Association, dental schools, and dental textbooks (Fig. 1-1). The dentist should choose a prepared form or formulate an individualized one.

FIGURE 1-1 Example of health history questionnaire useful for screening dental patients. (Modified from a form provided by the American Dental Association.)

The items listed in Box 1-2 (collected on a form or verbally) help establish a suitable health history database for patients; if the data are collected verbally, written documentation of the results of the inquiry is important.

In addition to this basic information, it is helpful to inquire specifically about common medical problems that are likely to alter dental management of the patient. These problems include angina, myocardial infarction (MI), heart murmurs, rheumatic heart disease, bleeding disorders (including anticoagulant use), asthma, lung disease, hepatitis, sexually transmitted disease, renal disease, diabetes, corticosteroid use, seizure disorder, stroke, and implanted prosthetic devices such as artificial joints or heart valves. Patients should be asked specifically about allergies to local anesthetics, aspirin, and penicillin. Female patients in the appropriate age group must also be asked at each visit whether they may be pregnant.

A brief family history can be useful and should focus on relevant inherited diseases, such as hemophilia (Box 1-3). The medical history should be updated periodically, at least annually. Many dentists have their assistants specifically ask each patient at checkup appointments whether there has been any change in health since the last dental visit. The dentist is alerted if a change has occurred, and changes are documented in the record.

Review of Systems

The review of systems is a sequential, comprehensive method of eliciting patient symptoms on an organ system basis. The review of systems may reveal undiagnosed medical conditions. This review can be extensive when performed by a physician for a patient with complicated medical problems. However, the review of systems conducted by the dentist before oral surgery should be guided by pertinent answers obtained from the history. For example, the review of the cardiovascular system in a patient with a history of ischemic heart disease includes questions concerning chest discomfort (during exertion, eating, or at rest), palpitations, fainting, and ankle swelling. Such questions help the dentist decide whether to perform surgery at all or to alter the surgical or anesthetic methods. If anxiety-controlling adjuncts such as intravenous (IV) and inhalation sedation are planned, the cardiovascular, respiratory, and nervous systems should always be reviewed; this can disclose previously undiagnosed problems that may jeopardize successful sedation. In the role of the oral health specialist, the dentist is expected to perform a quick review of the head, ears, eyes, nose, mouth, and throat on every patient, regardless of whether other systems are reviewed. Items to be reviewed are outlined in Box 1-4.

The need to review organ systems in addition to those in the maxillofacial region depends on clinical circumstances. The cardiovascular and respiratory systems commonly require evaluation before oral surgery or sedation (Box 1-5).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination of the dental patient focuses on the oral cavity and to a lesser degree on the entire maxillofacial region. Recording the results of the physical examination should be an exercise in accurate description rather than a listing of suspected medical diagnoses. For example, the clinician may find a mucosal lesion inside the lower lip that is 5 mm in diameter, raised and firm, and not painful to palpation. These physical findings should be recorded in a similarly descriptive manner; the dentist should not jump to a diagnosis and record only “fibroma on lip.”

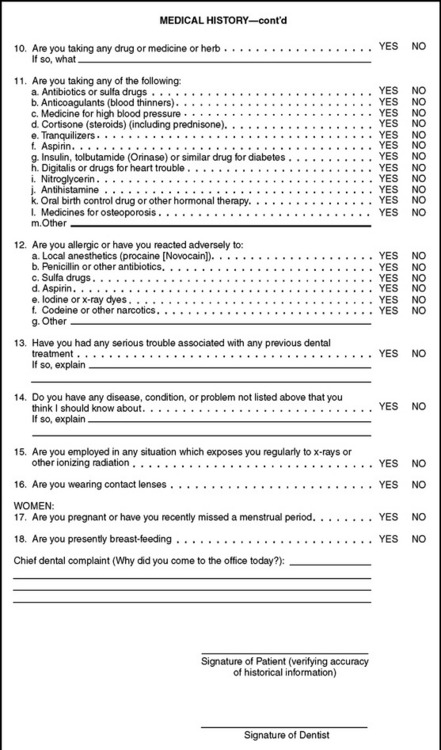

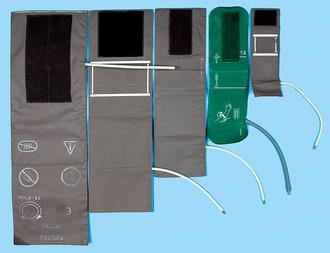

Any physical examination should begin with the measurement of vital signs. This serves as a screening device for unsuspected medical problems and as a baseline for future measurements. The techniques of measuring blood pressure and pulse rates are illustrated in Figures 1-2 and 1-3.

FIGURE 1-2 A, Measurement of systemic blood pressure. Cuff of proper size placed securely around upper arm so that lower edge of cuff lies 2 to 4 cm above antecubital fossa. Branchial artery is palpated in fossa, and stethoscope diaphragm is placed over artery and held in place with fingers of left hand. Squeeze bulb is held in palm of right hand, and valve is screwed closed with thumb and index finger of that hand. Bulb is then repeatedly squeezed until pressure gauge reads approximately 220 mm Hg. Air is allowed to escape slowly from cuff by partially opening valve while dentist listens through stethoscope. Gauge reading at point when faint blowing sound is first heard is systolic blood pressure. Gauge reading when sound from artery disappears is diastolic pressure. Once diastolic pressure reading is obtained, valve is opened to deflate cuff completely. B, Pulse rate and rhythm most commonly are evaluated by using tips of middle and index fingers of right hand to palpate radial artery at the wrist. Once rhythm has been determined to be regular, number of pulsations to occur during 30 seconds is multiplied by 2 to give number of pulses per minute. If weak pulse or irregular rhythm is discovered while palpating radial pulse, heart should be auscultated directly to determine heart rate and rhythm.

FIGURE 1-3 Blood pressure cuffs of varying sizes for patients with arms of different diameters (ranging from infant through obese patients). Use of an improper cuff size can jeopardize the accuracy of blood pressure results. Too small a cuff causes readings to be falsely high, and too large a cuff causes artificially low readings. Blood pressure cuffs typically are labeled as to the type and size of patient for whom they are designed.

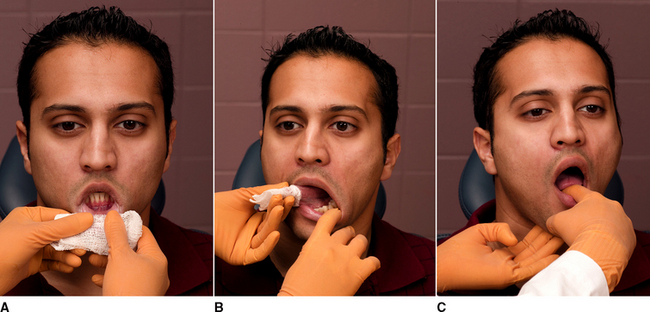

The physical evaluation of various parts of the body usually involves one or more of the following four primary means of evaluation: (1) inspection, (2) palpation, (3) percussion, and (4) auscultation. In the oral and maxillofacial regions, inspection should always be performed. The clinician should note hair distribution and texture, facial symmetry and proportion, eye movements and conjunctival color, nasal patency on each side, the presence or absence of skin lesions or discoloration, and neck or facial masses. A thorough inspection of the oral cavity is necessary, including the oropharynx, tongue, floor of the mouth, and oral mucosa (Fig. 1-4).

FIGURE 1-4 A, Lip mucosa examined by everting upper and lower lips. B, Tongue examined by having patient protrude it. Examiner then grasps tongue with cotton sponge and gently manipulates it to examine lateral borders. Patient also is asked to lift tongue to allow visualization of ventral surface and floor of mouth. C, Submandibular gland examined by bimanually feeling gland through floor of mouth and skin under floor of mouth.

Palpation is important when examining temporomandibular joint function, salivary gland size and function, thyroid gland size, presence or absence of enlarged or tender lymph nodes, and induration of oral soft tissues, as well as for determining pain or the presence of fluctuance in areas of swelling.

Physicians commonly use percussion during thoracic and abdominal examinations, and the dentist can use it to test teeth and paranasal sinuses. The dentist uses auscultation primarily for temporomandibular joint evaluation, but it is also used for cardiac, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal systems evaluations (Box 1-6). A brief maxillofacial examination that all dentists should be able to perform is described in Box 1-7.

The results of the medical evaluation are used to assign a physical status classification. A few classification systems exist, but the one most commonly used is the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) physical status classification system (Box 1-8).

Once an ASA physical status class has been determined, the dentist can decide whether required treatment can be safely and routinely performed in the dental office. If a patient is not ASA class I or a relatively healthy class II patient, the practitioner generally has the following four options: (1) modifying routine treatment plans by anxiety-reduction measures, pharmacologic anxiety-control techniques, more careful monitoring of the patient during treatment, or a combination of these methods (this is usually all that is necessary for ASA class II); (2) obtaining medical consultation for guidance in preparing patients to undergo ambulatory oral surgery (e.g., not fully reclining a patient with congestive heart failure); (3) refusing to treat the patient in the ambulatory setting; or (4) referring the patient to an oral-maxillofacial surgeon. Modifications to the ASA system designed to be more specific to dentistry are available but are not yet widely used among health care professionals.

MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH COMPROMISING MEDICAL CONDITIONS

Patients with medical conditions sometimes require modifications of their perioperative care when oral surgery is planned. This section discusses those considerations for the major categories of health problems.

Cardiovascular Problems

ANGINA PECTORIS.: Obstruction of the arterial supply to the myocardium is one of the most common health problems dentists encounter. This condition occurs primarily in men over age 40 and is also prevalent in postmenopausal women. The basic disease process is a progressive narrowing or spasm (or both) of one or more of the coronary arteries. This leads to a discrepancy between the myocardial oxygen demand and the ability of the coronary arteries to supply oxygen-carrying blood. Myocardial oxygen demand can be increased, for example, by exertion, anxiety, or during digestion of a large meal. Angina is a symptom of ischemic heart disease produced when myocardial blood supply cannot be sufficiently increased to meet the increased oxygen requirements that result from coronary artery disease.* The myocardium becomes ischemic, producing a heavy pressure or squeezing sensation in the patient’s substernal region that can radiate into the left shoulder and arm and into the mandibular region. The patient may complain of an intense sense of being unable to breathe adequately. Stimulation of vagal activity commonly occurs with nausea, sweating, and bradycardia. The discomfort typically disappears once the myocardial work requirements are lowered or the oxygen supply to the heart muscle is increased.

The practitioner’s responsibility to a patient with a history of angina is to use all available preventive measures, thereby reducing the possibility that the surgical procedure will precipitate an anginal episode. Preventive measures begin with taking a careful history of the patient’s angina. The patient should be questioned about the events that produce angina; the frequency, duration, and severity of angina; and the response to medications or diminished activity. The patient’s physician can be consulted concerning the cardiac status.

If the patient’s angina arises only during moderately vigorous exertion and responds readily to oral nitroglycerin administration, and if no recent increase in severity has occurred, ambulatory oral surgery procedures are usually safe when performed with proper precautions.

However, if anginal episodes occur with only minimal exertion, if several doses of nitroglycerin are needed to relieve chest discomfort, or if the patient has unstable angina (i.e., angina present at rest or worsening in frequency, severity, ease of precipitation, duration of attack, or predictability of response to medication), elective surgery should be deferred until a medical consultation is obtained. Alternatively, the patient can be referred to an oral-maxillofacial surgeon if emergency surgery is necessary.

Once the decision is made that ambulatory elective oral surgery can safely proceed, the patient should be prepared for surgery and the patient’s myocardial oxygen demand should be lowered or prevented from rising. The increased oxygen demand during ambulatory oral surgery is the result primarily of patient anxiety. An anxiety-reduction protocol should therefore be used (Box 1-9). In addition, during surgery the patient can be given supplemental oxygen and can be premedicated with nitroglycerin (if the patient is extremely prone to angina). Profound local anesthesia is the best means of limiting patient anxiety. Although some controversy exists over the use of local anesthetics containing epinephrine in patients with angina, the benefits (e.g., prolonged and accentuated anesthesia) outweigh the risks. However, care should be taken to avoid excessive epinephrine administration by using proper injection techniques. Some clinicians also advise giving no more than 4 mL of a local anesthetic solution with a 1:100,000 concentration of epinephrine for a total adult dose of 0.04 mg in any 30-minute period.

Before and during surgery, vital signs should be monitored periodically. In addition, regular verbal contact with the patient should be maintained. The use of nitrous oxide or other conscious sedation methods for anxiety control in patients with ischemic heart disease should be considered. Fresh nitroglycerin should be nearby for use if necessary (Box 1-10).

The introduction of balloon-tipped catheters into narrowed coronary arteries for the purpose of reestablishing adequate blood flow and stenting arteries open is becoming commonplace. If the angioplasty has been successful (based on cardiac stress testing), oral surgery can proceed soon thereafter, with the same precautions as those used for patients with angina.

MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION.: MI occurs when ischemia (resulting from an oxygen demand and supply mismatch) causes cellular dysfunction and death. The infarcted area of myocardium becomes nonfunctional and eventually necrotic and is surrounded by an area of usually reversibly ischemic myocardium that is prone to serve as a nidus for dysrhythmias. During the early hours and weeks after an MI, treatment consists of limiting myocardial work requirements, increasing myocardial oxygen supply, and suppressing the production of dysrhythmias by irritable foci in ischemic tissue. In addition, if any of the primary conduction pathways are involved in the infarction, pacemaker insertion may be necessary. If the patient survives the early weeks after an MI, the variably sized necrotic area is gradually replaced with scar tissue, which is unable to contract or properly conduct electrical signals.

The management of an oral surgical problem in a patient who has had an MI begins with a consultation with the patient’s physician. Generally, it is recommended that elective major surgical procedures be deferred until at least 6 months after an infarction. This delay is based on statistical evidence that the risk of reinfarction after an MI drops to as low as it will ever be by about 6 months, particularly if the patient is properly supervised medically. The advent of thrombolytic-based treatment strategies and improved MI care make an automatic 6-month wait to do dental work unnecessary. Straightforward oral surgical procedures typically performed in the dental office may be performed less than 6 months after an MI if the procedure is unlikely to provoke significant anxiety and the patient had an uneventful recovery from the MI. In addition, other dental procedures may proceed if cleared by the patient’s physician via a medical consult.

Patients with a history of MI should be carefully questioned concerning their cardiovascular health. An attempt to elicit evidence of undiagnosed dysrhythmias or congestive heart failure (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) should be made. Some patients who have had an MI take aspirin and other anticoagulants to decrease coronary thrombogenesis; this information should be sought because it can affect surgical decision making.

If more than 6 months have elapsed or physician clearance is obtained, the management of the patient who has had an MI is similar to care of the patient with angina. An anxiety-reduction program should be used. Supplemental oxygen can also be considered. Prophylactic nitroglycerin administration should be done only if directed by the patient’s primary care physician, but nitroglycerin should be readily available. Local anesthetics containing epinephrine are safe to use if given in proper amounts using an aspiration technique. Vital signs should be monitored throughout the perioperative period (Box 1-11).

In general, with respect to major oral surgical care, patients who have had coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) are treated in a manner similar to patients who have had an MI. Before major elective surgery is performed, 3 months are allowed to elapse. If major surgery is necessary before 3 months after the CABG, the patient’s physician should be consulted. Patients who have had CABG usually have a history of angina, MI, or both and therefore should be managed as previously described. Routine office surgical procedures may be safely performed in patients less than 6 months after CABG surgery if their recovery has been uncomplicated and anxiety is kept to a minimum.

Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke)

Patients who have had a cerebrovascular accident are always susceptible to further neurovascular accidents. These patients are generally prescribed anticoagulants and, if hypertensive, are taking blood pressure–lowering agents. If such a patient requires surgery, clearance by the patient’s physician is desirable, as is a delay until significant hypertensive tendencies have been controlled. The patient’s baseline neurologic status should be assessed and documented preoperatively. The patient should be treated by a nonpharmacologic anxiety-reduction protocol and have vital signs carefully monitored during surgery. If pharmacologic sedation is necessary, low concentrations of nitrous oxide can be used. Techniques to manage patients taking anticoagulants are discussed later in this chapter.

Dysrhythmias

Patients who are prone to or who have cardiac dysrhythmias usually have a history of ischemic heart disease requiring dental management modifications. Many advocate limiting the total amount of epinephrine administration to 0.04 mg. However, in addition, these patients may have been prescribed anticoagulants or have a permanent cardiac pacemaker. Pacemakers pose no contraindications to oral surgery, and no evidence exists that shows the need for antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with pacemakers. Electrical equipment, such as electrocautery and microwaves, should not be used near the patient. As with other medically compromised patients, vital signs should be carefully monitored.

Heart Abnormalities Predisposed Toward Infective Endocarditis

The internal cardiac surface, or endocardium, can be predisposed toward infection when abnormalities of its surface allow pathologic bacteria to attach and multiply. A complete description of this process and recommended means of possibly preventing it are discussed in Chapter 16.

Congestive Heart Failure (Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy)

Congestive heart failure occurs when a diseased myocardium is unable to deliver the cardiac output demanded by the body or when excessive demands are placed on a normal myocardium. The heart begins to have an increased end-diastolic volume that, in the case of the normal myocardium, increases contractility through the Frank-Starling mechanism. However, as the normal or diseased myocardium further dilates, it becomes a less efficient pump, causing blood to back up into the pulmonary, hepatic, and mesenteric vascular beds. This eventually leads to pulmonary edema, hepatic dysfunction, and compromised intestinal nutrient absorption. The lowered cardiac output causes generalized weakness, and impaired renal clearance of excess fluid leads to vascular overload.

Symptoms of congestive heart failure include orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and ankle edema. Orthopnea is a respiratory disorder that exhibits shortness of breath when the patient is in the supine position. Orthopnea usually occurs as a result of the redistribution of blood pooled in the lower extremity when a patient assumes the supine position (as when sleeping). The ability of the heart to handle the increased cardiac preload is overwhelmed, and blood backs up into the pulmonary circulation, producing pulmonary edema. Patients with orthopnea usually sleep with their upper body supported on several pillows.

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea is a symptom of congestive heart failure that is similar to orthopnea. The patient has respiratory difficulty 1 or 2 hours after assuming a supine position. The disorder occurs when pooled blood and interstitial fluid reabsorbed into the vasculature from the legs are redistributed centrally, overwhelming the heart and producing pulmonary edema. Patients suddenly wake awhile after lying down to sleep feeling short of breath and are compelled to sit up to try to catch their breath.

Lower extremity edema usually appears as a swelling of the foot, the ankle, or both that is caused by an increase in interstitial fluid. Usually the fluid collects as a result of any problem that increases venous pressure or low serum protein, allowing increased amounts of plasma to remain in the tissue spaces of the feet. The edema is detected by pressing a finger into the swollen area for a few seconds; if an indentation in the soft tissue is left after the finger is removed, pedal edema is present. Other symptoms of congestive heart failure include weight gain and dyspnea on exertion.

Patients with congestive heart failure who are under a physician’s care are usually following low-sodium diets to reduce fluid retention and are receiving diuretics to reduce intravascular volume; cardiac glycosides, such as digoxin, to improve cardiac efficiency; and sometimes afterload-reducing drugs, such as nitrates, β-adrenergic antagonists, or calcium channel antagonists, to control the amount of work the heart is required to do. In addition, patients with chronic atrial fibrillation caused by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are usually prescribed anticoagulants to prevent atrial thrombus formation.

Patients with congestive heart failure that is well compensated through dietary and drug therapy can safely undergo ambulatory oral surgery. The anxiety-reduction protocol and supplemental oxygen are helpful. Patients with orthopnea should not be placed supine during any procedure. Surgery for patients with uncompensated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is best deferred until compensation is achieved or procedures can be performed in the hospital setting (Box 1-12).

Pulmonary Problems

When a patient relates a history of asthma, the dentist should first determine through further questioning whether the patient truly has asthma or has a respiratory problem such as allergic rhinitis that carries less significance for dental care. True asthma involves the episodic narrowing of small airways, which produces wheezing and dyspnea as a result of chemical, infectious, immunologic, or emotional stimulation, or a combination of these. Patients with asthma should be questioned concerning precipitating factors, frequency and severity of attacks, medications used, and response to medications. The severity of attacks can often be gauged by the need for emergency room visits and hospital admissions. Asthmatic patients should be questioned specifically about aspirin allergy because of the relatively high frequency of generalized nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) allergy in asthmatic patients.

Physicians prescribe medications for patients with asthma according to the frequency, severity, and causes of their disease. Patients with severe asthma require xanthine-derived bronchodilators, such as theophylline, and corticosteroids. Cromolyn may be used to protect against acute attacks, but it is ineffective once bronchospasm occurs. Many patients carry sympathomimetic amines, such as epinephrine or metaproterenol, in an aerosol form that can be self-administered if wheezing begins.

Oral surgical management of the patient with asthma involves recognition of the role of anxiety in bronchospasm initiation and of the potential adrenal suppression in patients receiving corticosteroid therapy (see previous discussion). Elective oral surgery should be deferred if a respiratory tract infection or wheezing is present. When surgery is performed, an anxiety-reduction protocol must be followed; if the patient takes steroids, the patient’s primary care physician can be consulted concerning the possible need for corticosteroid augmentation during the perioperative period if a major surgical procedure is planned. Nitrous oxide is safe to administer to persons with asthma and is especially indicated for patients whose asthma is triggered by anxiety. The patient’s own inhaler should be available during surgery, and drugs such as injectable epinephrine and theophylline should be kept in an emergency kit. The use of NSAIDs should be avoided because they often precipitate asthma attacks in susceptible individuals (Box 1-13).

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Obstructive and restrictive pulmonary diseases are usually grouped together under the heading of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In the past the terms emphysema and bronchitis were used to describe clinical manifestations of COPD, but COPD has been recognized to be a blend of pathologic pulmonary problems. COPD is usually caused by long-term exposure to pulmonary irritants, such as tobacco smoke, that cause metaplasia of pulmonary airway tissue. Airways are disrupted, lose their elastic properties, and become obstructed because of mucosal edema, excessive secretions, and bronchospasm, producing the clinical manifestations of COPD. Patients with COPD frequently become dyspneic during mild to moderate exertion. They have a chronic cough that produces large amounts of thick secretions, frequent respiratory tract infections, and barrel-shaped chests, and they may purse their lips to breathe and have audible wheezing during breathing.

Bronchodilators, such as theophylline, are usually prescribed for patients with significant COPD; in more severe cases, patients are given corticosteroids. Only in the most severe chronic cases is supplemental portable oxygen used.

When dentally managing patients with COPD who are receiving corticosteroids, the dentist should consider the use of additional supplementation before major surgery. Sedatives, hypnotics, and narcotics that depress respiration should be avoided. Patients may need to be kept in an upright sitting position in the dental chair to enable them to better handle their commonly copious pulmonary secretions. Finally, supplemental oxygen during surgery should not be used in patients with severe COPD unless the physician advises it. In contrast with healthy persons in whom an elevated arterial CO2 level is the major stimulation to breathing, the patient with COPD becomes acclimated to elevated arterial CO2 levels and comes to depend entirely on depressed arterial oxygen levels to stimulate breathing. If the arterial oxygen concentration is elevated by the administration of oxygen in a high concentration, the hypoxia-based respiratory stimulation is removed and the patient’s respiratory rate may become critically slowed (Box 1-14).

Renal Problems

Patients in renal failure require periodic renal dialysis. These patients need special consideration during oral surgical care. Chronic dialysis treatment typically requires the presence of an arteriovenous shunt (i.e., a large, surgically created junction between an artery and vein), which allows easy vascular access and heparin administration, allowing blood to move through the dialysis equipment without clotting. The dentist should not use the shunt for venous access except in an emergency.

Elective oral surgery is best undertaken the day after a dialysis treatment has been performed. This allows the heparin used during dialysis to disappear and the patient to be in the best physiologic status with respect to intravascular volume and metabolic by-products.

Drugs that depend on renal metabolism or excretion should be avoided or used in modified doses to prevent systemic toxicity. Drugs removed during dialysis will also necessitate special dosing regimens. Relatively nephrotoxic drugs, such as NSAIDs, should also be avoided in patients with seriously compromised kidneys.

Because of the higher incidence of hepatitis in renal dialysis patients, dentists should take the necessary precautions. The altered appearance of bone caused by secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients with renal failure should also be noted. Metabolic radiolucencies should not be mistaken for dental disease (Box 1-15).

Renal Transplant and Transplant of Other Organs

The patient requiring surgery after renal or other major organ transplantation is usually receiving a variety of drugs to preserve the function of the transplanted tissue. These patients receive corticosteroids and may need supplemental corticosteroids in the perioperative period (see discussion on adrenal insufficiency later in this chapter).

Most of these patients also receive immunosuppressive agents that may cause otherwise self-limiting infections to become severe. Therefore a more aggressive use of antibiotics and early hospitalization for infections are warranted. The patient’s primary care physician should be consulted concerning the need for prophylactic antibiotics.

Cyclosporine A, an immunosuppressive drug administered after organ transplantation, may cause gingival hyperplasia. The dentist performing oral surgery should recognize this so as not to wrongly attribute gingival hyperplasia entirely to hygiene problems.

Patients who have had renal transplants occasionally have problems with severe hypertension. Vital signs should be obtained before oral surgery is performed in these patients (Box 1-16).

Hypertension

Chronically elevated blood pressure for which the cause is unknown is called essential hypertension. Mild or moderate hypertension (i.e., systolic pressure of less than 200 mm Hg or diastolic pressure of less than 110 mm Hg) is usually not a problem in the performance of ambulatory oral surgical care.

Care of the poorly controlled hypertensive patient includes use of an anxiety-reduction protocol and monitoring of vital signs. Epinephrine-containing local anesthetics should be used cautiously; after surgery, patients should be advised to seek medical care for their hypertension.

Elective oral surgery for patients with severe hypertension (i.e., systolic pressure of 200 mm Hg or more or diastolic pressure of 110 mm Hg or more) should be postponed until the pressure is better controlled. Emergency oral surgery in severely hypertensive patients should be performed in a wellcontrolled environment or in the hospital to allow the patient to be carefully monitored during surgery and then to arrange for acute blood pressure control (Box 1-17).

Hepatic Disorders

The patient with severe liver damage resulting from infectious disease, ethanol abuse, or vascular or biliary congestion requires special consideration before oral surgery is performed. An alteration of dose or avoidance of drugs that require hepatic metabolism may be necessary.

The production of vitamin K–dependent coagulation factors (II, VII, IX, X) may be depressed in severe liver disease; therefore, obtaining an international normalized ratio (INR; prothrombin time [PT]) or partial thromboplastin time may be useful before surgery in patients with more severe liver disease. Portal hypertension caused by liver disease may also cause hypersplenism, a sequestering of platelets causing thrombocytopenia. Finding a prolonged Ivy’s bleeding time reveals this problem. Patients with severe liver dysfunction may require hospitalization for dental surgery because their decreased ability to metabolize the nitrogen in swallowed blood may cause encephalopathy. Finally, unless documented otherwise, a patient with liver disease should be presumed to carry hepatitis virus (Box 1-18).

Endocrine Disorders

Diabetes mellitus is caused by an underproduction of insulin, a resistance of insulin receptors in end-organs to the effects of insulin, or both. Diabetes is commonly divided into insulin-dependent and non–insulin-dependent diabetes. Insulin-dependent diabetes usually begins during childhood or adolescence. The major problem in this form of diabetes is an underproduction of insulin, which results in the inability of the patient to use glucose properly. The serum glucose rises above the level at which renal reabsorption of all glucose can take place, causing glucosuria. The osmotic effect of the glucose solute results in polyuria, stimulating patient thirst and causing polydipsia (frequent consumption of liquids). In addition, carbohydrate metabolism is altered, leading to fat breakdown and the production of ketone bodies. This can produce ketoacidosis and the attendant tachypnea with somnolence and eventually coma.

Persons with insulin-dependent diabetes must strike a balance between caloric intake, exercise, and insulin dose. Any decrease in regular caloric intake or increase in activity, metabolic rate, or insulin dose can lead to hypoglycemia and vice versa.

Patients with non–insulin-dependent diabetes usually produce insulin but in insufficient amounts because of decreased insulin activity, insulin receptor resistance, or both. This form of diabetes typically begins in adulthood, is exacerbated by obesity, and does not usually require insulin therapy. This form of diabetes is treated by weight control, dietary restrictions, and the use of oral hypoglycemics. Insulin is required only if the patient is unable to maintain acceptable serum glucose levels using the usual therapeutic measures. Severe hyperglycemia in non–insulin-dependent diabetic patients rarely produces ketoacidosis but leads to a hyperosmolar state with altered levels of consciousness.

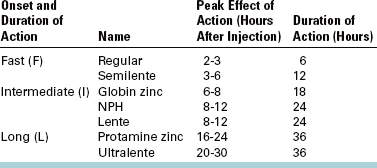

Short-term, mild to moderate hyperglycemia is usually not a significant problem for persons with diabetes. Therefore when an oral surgical procedure is planned, it is best to err on the side of hyperglycemia rather than hypoglycemia; that is, it is best to avoid an excessive insulin dose and to give a glucose source. Ambulatory oral surgery procedures should be performed early in the day, using an anxiety-reduction program. If IV sedation is not being used, the patient should be asked to eat a normal meal and take the usual morning amount of regular insulin and a half dose of neutral protamine hagedorn (NPH) insulin (Table 1-1). The patient’s vital signs should be monitored; if signs of hypoglycemia, such as hypotension, hunger, drowsiness, nausea, diaphoresis, tachycardia, or a mood change, occur, an oral or IV supply of glucose should be administered. Ideally, offices have an electronic glucometer available with which the clinician or patient can readily determine serum glucose with a drop of the patient’s blood. This device may avoid the need to steer the patient toward mild hyperglycemia. If the patient will be unable to eat temporarily after surgery, any delayed-action insulin (most commonly NPH) normally taken in the morning should be eliminated and restarted only after normal caloric intake resumes. The patient should be advised to monitor serum glucose closely for the first 24 hours postoperatively and adjust insulin accordingly.

TABLE 1-1

Types of Insulin*

*Insulin sources are pork—F, I; beef—F, I, L; beef and pork—F, I, L; and recombinant DNA—F, I, L.

If a patient must miss a meal before a surgical procedure, the patient should be told to skip any morning insulin and only resume insulin once the patient is able to receive a supply of calories. Regular insulin should then be used, with the dose based on serum glucose monitoring and as directed by the patient’s physician. Once the patient has resumed normal dietary habits and physical activity, the usual insulin regimen can be restarted.

Persons with well-controlled diabetes are no more susceptible to infections than persons without diabetes, but they have more difficulty containing infections. This is caused by altered leukocyte function or by other factors that affect the ability of the body to control an infection. Difficulty in containing infections is more significant in persons with poorly controlled diabetes. Therefore, elective oral surgery should be deferred in patients with poorly controlled diabetes until control is accomplished. However, if an emergency situation or a serious oral infection exists in any person with diabetes, consideration should be given to hospital admission to allow for acute control of the hyperglycemia and aggressive management of the infection. Many clinicians also believe that prophylactic antibiotics should be given routinely to patients with diabetes undergoing any surgical procedure. However, this position is controversial (Box 1-19).

Adrenal Insufficiency

Diseases of the adrenal cortex may cause adrenal insufficiency. Symptoms of primary adrenal insufficiency include weakness, weight loss, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation of skin and mucous membranes. However, the most common cause of adrenal insufficiency is chronic therapeutic corticosteroid administration (secondary adrenal insufficiency). Often, patients who regularly take corticosteroids have moon facies, buffalo humps, and thin, translucent skin. Their inability to increase endogenous corticosteroid levels in response to physiologic stress may cause them to become hypotensive, syncopal, nauseated, and feverish during complex, prolonged surgery.

If a patient with primary or secondary adrenal suppression requires complex oral surgery, the primary care physician should be consulted regarding the potential need for supplemental steroids. In general, minor procedures require only the use of an anxiety-reduction protocol. Thus supplemental steroids are not needed for most dental procedures. However, more complicated procedures, such as orthognathic surgery in an adrenally suppressed patient, usually necessitate steroid supplementation (Box 1-20).

Hyperthyroidism

The thyroid gland problem of primary significance in oral surgery is thyrotoxicosis because thyrotoxicosis is the only thyroid gland disease in which an acute crisis can occur. Thyrotoxicosis is the result of an excess of circulating triiodothyronine and thyroxine, which is caused most frequently by Graves’ disease, a multinodular goiter, or a thyroid adenoma. The early manifestations of excessive thyroid hormone production include fine, brittle hair, hyperpigmentation of skin, excessive sweating, tachycardia, palpitations, weight loss, and emotional lability. Patients frequently, although not invariably, have exophthalmos (a bulging forward of the globes caused by increases of fat in the orbit). If hyperthyroidism is not recognized early, the patient may have heart failure. The diagnosis is made by the demonstration of elevated circulating thyroid hormones, using direct or indirect laboratory techniques.

Thyrotoxic patients are usually treated with agents that block thyroid hormone synthesis and release, with a thyroidectomy, or with both. However, patients left untreated or incompletely treated can have a thyrotoxic crisis caused by the sudden release of large quantities of preformed thyroid hormones. Early symptoms of a thyrotoxic crisis include restlessness, nausea, and abdominal cramps. Later symptoms are a high fever, diaphoresis, tachycardia, and, eventually, cardiac decompensation. The patient becomes stuporous and hypotensive, with death resulting if no intervention occurs.

The dentist may be able to diagnose previously unrecognized hyperthyroidism by taking a complete medical history and performing a careful examination of the patient, including thyroid gland inspection and palpation. If severe hyperthyroidism is suspected from the history and inspection, the gland should not be palpated because that manipulation alone can trigger a crisis. Patients suspected of being hyperthyroid should be referred for medical evaluation before oral surgery.

Patients with treated thyroid gland disease can safely undergo ambulatory oral surgery. However, if a patient is found to have an oral infection, the primary care physician should be notified, particularly if the patient shows signs of hyperthyroidism. Atropine and excessive amounts of epinephrine-containing solutions should be avoided if a patient is thought to have incompletely treated hyperthyroidism (Box 1-21).

Hypothyroidism

The dentist can play a role in the initial recognition of hypothyroidism. Early symptoms of hypothyroidism include fatigue, constipation, weight gain, hoarseness, headaches, arthralgia, menstrual disturbances, edema, dry skin, and brittle hair and fingernails. If the symptoms of hypothyroidism are mild, no modification of dental therapy is required.

Hematologic Problems

Patients with inherited bleeding disorders are usually aware of their problem, allowing the clinician to take the necessary precautions before any surgical procedure. However, in many patients, prolonged bleeding after the extraction of a tooth may be the first evidence that a bleeding disorder exists. Therefore, all patients should be questioned concerning coagulation after previous injuries and surgery. A history of epistaxis (nosebleeds), easy bruising, hematuria, heavy menstrual bleeding, and spontaneous bleeding should alert the dentist to the possible need for a presurgical laboratory coagulation screening. A PT is used to test the extrinsic pathway factors (II, V, VII, and X), whereas a partial thromboplastin time is used to detect intrinsic pathway factors. To better standardize PT values within and between hospitals, the INR method has been developed. This technique adjusts the actual PT for variations in agents used to run the test, and the value is presented as a ratio between the patient’s PT and a standardized value from the same laboratory.

Platelet inadequacy usually causes easy bruising and is evaluated by a bleeding time and platelet count. If a coagulopathy is suspected, the primary care physician or a hematologist should be consulted about more refined testing to better define the cause of the bleeding disorder and to help manage the patient in the perioperative period.

The management of patients with coagulopathies who require oral surgery depends on the nature of the bleeding disorder. Specific factor deficiencies—such as hemophilia A, B, or C or von Willebrand’s disease—are usually managed by the perioperative administration of factor replacement and by the use of an antifibrinolytic agent such as aminocaproic acid (Amicar). The physician decides the form in which factor replacement is given, based on the degree of factor deficiency and on the patient’s history of factor replacement. Patients who receive factor replacement sometimes contract hepatitis or human immunodeficiency virus. Therefore, appropriate staff protection measures should be taken during surgery.

Platelet problems may be quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative platelet deficiency may be a cyclic problem, and the hematologist can help determine the proper timing of elective surgery. Patients with a chronically low platelet count can be given platelet transfusions. Counts must usually dip below 50,000/mm3 before abnormal postoperative bleeding occurs. If the platelet count is between 20,000/mm3 and 50,000/mm3, the hematologist may wish to withhold platelet transfusion until postoperative bleeding becomes a problem. However, platelet transfusions may be given to patients with counts higher than 50,000/mm3 if a qualitative platelet problem exists. Platelet counts under 20,000/mm3 usually require presurgical platelet transfusion or a delay in surgery until platelet numbers rise. Local anesthesia should be given by local infiltration rather than by field blocks to lessen the likelihood of damaging larger blood vessels, which can lead to prolonged postinjection bleeding and hematoma formation. Consideration should be given to the use of topical coagulation-promoting substances in oral wounds, and the patient should be carefully instructed in ways to avoid dislodging blood clots once they have formed (Box 1-22). See Chapter 11 for additional means of preventing or managing postextraction bleeding.

Therapeutic Anticoagulation

Therapeutic anticoagulation is administered to patients with thrombogenic implanted devices, such as prosthetic heart valves; with thrombogenic cardiovascular problems, such as atrial fibrillation or after MI; or with a need for extracorporeal blood flow, such as for hemodialysis. Patients may also take drugs with anticoagulant properties, such as aspirin, for secondary effect.

When elective oral surgery is necessary, the need for continuous anticoagulation must be weighed against the need for blood clotting after surgery. This decision should be made in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician. Drugs such as aspirin do not usually need to be withdrawn to allow routine surgery. Patients taking heparin usually can have their surgery delayed until the circulating heparin is inactive (6 hours if heparin is given IV, 24 hours if given subcutaneously). Protamine sulfate, which reverses the effects of heparin, can also be used if emergency oral surgery cannot be deferred until heparin is naturally inactivated.

Patients requiring warfarin for anticoagulation but who also need elective oral surgery benefit from close cooperation between the patient’s physician and dentist. Warfarin has a 2- to 3-day delay in the onset of action; therefore, alterations of warfarin anticoagulant effects appear several days after the dose is changed. The INR is used to gauge the anticoagulant action of warfarin. Most physicians will allow the INR to drop to about 2.0 during the perioperative period, which usually allows sufficient coagulation for safe surgery. Patients should stop taking warfarin 2 or 3 days before the planned surgery. On the morning of surgery, the INR value should be checked; if it is between 2 and 3 INR, routine oral surgery can be performed. If the PT is still greater than 3 INR, surgery should be delayed until the PT approaches 3 INR. Surgical wounds should be dressed with thrombogenic substances, and the patient should be given instruction in promoting clot retention. Warfarin therapy can be resumed the day of surgery (Box 1-23).

Neurologic Disorders

Patients with a history of seizures should be questioned about the frequency, type, duration, and sequelae of seizures. Seizures can result from ethanol withdrawal, high fever, hypoglycemia, or traumatic brain damage, or they can be idiopathic. The dentist should inquire about medications used to control the seizure disorder, particularly about patient compliance and any recent measurement of serum levels. The patient’s physician should be consulted concerning the seizure history and to establish whether oral surgery should be deferred for any reason. If the seizure disorder is well controlled, standard oral surgical care can be delivered without any further precautions (except for the use of an anxiety-reduction protocol; Box 1-24). If good control cannot be obtained, the patient should be referred to an oral-maxillofacial surgeon for treatment under deep sedation in the office or hospital.

Ethanolism (Alcoholism)

Patients volunteering a history of ethanol abuse or in whom ethanolism is suspected and then confirmed through means other than history taking require special consideration before surgery. The primary problems ethanol abusers have in relation to dental care are hepatic insufficiency, ethanol and medication interaction, and withdrawal phenomena. Hepatic insufficiency has already been discussed (see p. 14). Ethanol interacts with many of the sedatives used for anxiety control during oral surgery. The interaction usually potentiates sedation and suppresses the gag reflex.

Finally, ethanol abusers may undergo withdrawal phenomenon in the perioperative period if they have acutely lowered their daily ethanol intake before seeking dental care. This phenomenon may exhibit mild agitation, tremors, seizure, diaphoresis, or rarely, delirium tremens with hallucinosis, considerable agitation, and circulatory collapse.

Patients requiring oral surgery who exhibit signs of severe alcoholic liver disease or signs of ethanol withdrawal should be treated in the hospital setting. Liver function tests, a coagulation profile, and medical consultation before surgery are desirable. In patients able to be treated on an ambulatory basis, the dose of drugs metabolized in the liver should be altered and the patients should be monitored closely for signs of oversedation.

MANAGEMENT OF PREGNANT AND POSTPARTUM PATIENTS

Although not a disease state, pregnancy is still a situation in which special considerations are necessary when oral surgery is required. The primary concern when providing care for a pregnant patient is the prevention of genetic damage to the fetus. Two areas of oral surgical management with potential for creating fetal damage are (1) dental radiography and (2) drug administration. It is virtually impossible to perform an oral surgical procedure properly with neither radiographs nor the administration of medications; therefore, one option is to defer any elective oral surgery until after delivery to avoid fetal risk. Frequently, temporary measures can be used to delay surgery.

However, if surgery during pregnancy cannot be postponed, efforts should be made to lessen fetal exposure to teratogenic factors. In the case of imaging, use of protective aprons and taking digital periapical films of only the areas requiring surgery can accomplish this (Fig. 1-5). The list of drugs thought to pose little risk to the fetus is short. For purposes of oral surgery, the following drugs are believed least likely to harm a fetus when used in moderate amounts: lidocaine, bupivacaine, acetaminophen, codeine, penicillin, and cephalosporins. Although aspirin is otherwise safe to use, it should not be given late in the third trimester because of its anticoagulant property. All sedative drugs are best avoided in pregnant patients. Nitrous oxide should not be used during the first trimester but if necessary can be used in the second and third trimesters as long as it is delivered with at least 50% oxygen (Boxes 1-25 and 1-26). The Food and Drug Administration created a system of drug categorization based on the known degree of risk to the human fetus posed by particular drugs. When required to give a medication to a pregnant patient, the clinician should check that the drug falls into an acceptable risk category before administering it to the patient (Box 1-27).

Pregnancy can be emotionally and physiologically stressful; therefore an anxiety-reduction protocol is recommended. Patient vital signs should be obtained, with particular attention paid to any elevation in blood pressure (a possible sign of preeclampsia). A patient nearing delivery may need special positioning of the chair during care, because if the patient is placed in a nearly supine position, the uterine contents may cause compression of the inferior vena cava, compromising venous return to the heart and thereby cardiac output. The patient may need to be in a more upright position or have her torso turned slightly to one side during surgery. Frequent breaks to allow the patient to void are commonly necessary late in pregnancy because of fetal pressure on the urinary bladder. Before performing any oral surgery on a pregnant patient, the clinician should consult the patient’s obstetrician.

Postpartum

Special considerations should be taken when providing oral surgical care for the postpartum patient who is breast-feeding a child. Avoiding drugs that are known to enter breast milk and to be potentially harmful to infants is prudent (the child’s pediatrician can provide guidance). Information about some drugs is provided in Table 1-2. However, in general, all the drugs common in oral surgical care are safe to use in moderate doses, with the exception of corticosteroids, aminoglycosides, and tetracyclines, which should not be used.

TABLE 1-2

Effect of Dental Medications in Lactating Mothers

| No Apparent Clinical Effects in Breast-Feeding Infants | Potentially Harmful Clinical Effects in Breast-Feeding Infants |

| Acetaminophen | Ampicillin |

| Antihistamines | Aspirin |

| Cephalexin | Atropine |

| Codeine | Barbiturates |

| Erythromycin | Chloral hydrate |

| Fluoride | Corticosteroids |

| Lidocaine | Diazepam |

| Meperidine | Metronidazole |

| Oxacillin | Penicillin |

| Pentazocine | Propoxyphene |

| Tetracyclines |