Fluoride and dental health

Anthony Blinkhorn and Kareen Mekertichian

Introduction

Fluoride has made an incredible impact on the oral health of millions of adults and children. Physiologically, fluoride is a unique member of the halogen family, in that it is termed a ‘seeker of mineralized tissue’. It is this affinity with mineralized tissues which explains how fluoride can strengthen the teeth and prevent or heal dental caries.

Mechanism of action

Concepts of how fluoride prevents caries have changed markedly since the first water fluoridation schemes were introduced in the USA in the late 1940s and early 1950s. When ingested systemically, fluoride is incorporated into developing tooth enamel. The fluoride ion displaces some hydroxyl groups in hydroxyapatite to form fluorapatite. The smaller anion causes crystal stress but results in a significantly less soluble material. Initially, researchers focused on the systemic effect of fluoride as the key factor in the reduction of dental caries. However, the evidence for the systemic effect has been superseded by the realization that the reaction of the fluoride at the microenvironment of the plaque enamel interface encouraging remineralization is of major significance in terms of reducing the levels of dental caries (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001).

The important points to remember are:

• Fluoride acts topically, promoting remineralization and reducing demineralization.

• The mode of action is predominantly post-eruptive and prevention of caries requires lifelong presence of fluoride.

• When remineralization takes place in the presence of fluoride, the remineralized enamel is more resistant to caries because of increased fluorapatite within the enamel matrix.

• Only low levels of fluoride are required at the plaque enamel interface to promote effective remineralization.

• Fluoride has some effect on the glycolytic pathway of oral microorganisms reducing acid production and interfering with the enzymatic regulation of carbohydrate metabolism. This reduces the accumulation of intracellular and extracellular polysaccharides and leads to lower volumes of plaque.

Community fluoridation

There are three ways to offer fluoride on a community-wide basis: utilizing water, salt and milk.

Water fluoridation

The natural level of fluoride in drinking water is very variable. However, in reticulated community water supplies that are fluoridated, the concentration of fluoride is adjusted to approximately 0.8–1 ppm.

The majority of International Health Agencies agree with the World Health Organization in support of the continuation of community water fluoridation, as it is an effective, efficient, socially equitable and safe population approach to caries prevention.

The reduction in dental caries in fluoridated communities ranges from 20% to 40%, which is considerably less than was the case when it was first introduced in the USA because of the general increase in availability of fluoride from other sources (Downer and Blinkhorn, 2007). However, when fluoridation programmes have been discontinued, there is rapid increase in dental caries within a short time frame (Burt et al., 2000).

There are a number of points of which many members of the public are unaware when considering the value of water fluoridation:

• Fluoride benefits adults as well as children.

• There is a decreased prevalence of root-surface caries in lifelong inhabitants of areas with fluoridated water.

• The preferred source of fluoride is from community water fluoridation, as it benefits all the population and is a cost-effective intervention.

• The continuing existence of approximately 20% of children with a high caries experience indicates the need to maximize protection through the use of community water fluoridation.

The market for bottled water has grown rapidly in the last decade, and for many individuals water consumption from this source may have fully replaced reticulated water. The fluoride content of bottled water is usually very low, and consumers of bottled water in fluoridated communities will miss out on the benefits of fluoride.

Some water filters may remove fluoride, although this is mostly limited to those with reverse osmosis, bone or charcoal filters, distillation or ion exchange. Normal membrane filters will not remove a small ion such as fluoride. Ceramic and carbon filters retain fluoride in the filtered water. Filters that do not remove fluoride should be clearly labelled.

Salt fluoridation

Salt enriched with iodide has been used in many countries as an effective means of preventing goitre. It was a logical step to include fluoride in domestic table salt. It has the advantage of offering choice and does not encourage salt consumption as it is marketed as an alternative to the standard product. The amount of fluoride added is 250 mg F−/kg salt (250 ppm).

Switzerland was the first nation to pioneer salt fluoridation and it is now available in Spain, Hungary, France and parts of Brazil. It is certainly a practical alternative to water fluoridation, but the research base is much more limited on its absolute effectiveness, especially now that fluoride toothpaste is readily available.

Milk fluoridation

Bovine milk is used as a food for babies and young children, plus in many countries free milk is offered to children at school. These positive points were noted by researchers as a potential way to supplement children’s fluoride intake.

Despite its practical simplicity, milk fluoridation has not been implemented on a wide scale, mainly because of logistical difficulties and the fact that fluoride toothpaste is readily available. It may well have a place in developing countries, where the milk will improve nutrition as well as offering the benefits of fluoride.

Topical fluorides for home use

Lifetime protection against dental caries results from the continuous presence of fluoride in low concentrations, that will enhance the remineralization of white spot lesions, control initial invasive carious lesions and limit lesions occurring around existing restorations for both adults and children (Adair, 2006). An optimal concentration of fluoride each day at both the plaque/enamel interface and in saliva, will help minimize the risk of caries. Factors that should be considered when advising on a fluoride regimen include:

• The number of carious lesions or areas of demineralization.

• The frequency of consumption of sugary foods and drinks.

• Patient’s compliance with oral health advice.

Fluoride toothpastes

Of all the different ways of offering topical fluoride, the most common and simplest way in which to maintain elevated fluoride concentrations at the plaque/enamel interface, is the use of a toothpaste containing fluoride. Fluoride is added to toothpastes in one of the following forms:

The use of fluoride toothpastes has led to a 25% reduction in the prevalence of caries in many countries (Davies et al., 2002). It is recommended that children should brush twice a day with a toothpaste containing an appropriate concentration of fluoride, preferably last thing at night before bed and on one other occasion, ideally after breakfast. It is essential to ensure all parents are aware that vigorous rinsing after brushing will reduce the preventive effect of the toothpaste because the active agent ‘Fluoride’ will be washed away.

Advice on the type of toothpaste which young children should use, in terms of fluoride concentration is problematic (Franzman et al., 2006), as international guidelines differ. Members of the dental team must familiarize themselves with the guidelines appropriate for their own country and practice location. In Australia and the USA, fluoridation of public water supplies is quite common, whereas in Europe there are only a few community water fluoridation schemes (Walsh et al., 2010). However, there are a number of factors that health professionals must consider when offering advice to parents on fluoride toothpaste usage, namely:

• Low fluoride toothpastes (<1000 ppm) should not be used in areas where the water supply is not fluoridated, as they have a greatly reduced caries preventive effect.

• The age when parents are advised to begin brushing their children’s teeth varies between countries and members of the dental team should be familiar with the appropriate national policy.

• General advice is that children aged 6–36 months should use only a smear of toothpaste on the brush.

• Brushing with fluoride toothpaste before 12 months of age offers larger reductions in dental caries; but parents must supervise and only a smear of toothpaste should be placed on the brush.

• Parents of children aged over 6 years should be advised to place a ‘pea’ sized amount of toothpaste on the brush.

• Children over 6 years of age should use a ‘family’ toothpaste (1000–1450 ppm). However, earlier use of a ‘family’ paste is indicated if children are at risk of developing dental caries.

• Young children (up to the age of 7 years) should be supervised when brushing as this monitors toothpaste usage, has been associated with greater reductions in dental caries and reduces the chances of fluorosis in the upper anterior teeth.

• Children over 10 years of age and considered to be at high risk of developing caries or have active carious lesions may be prescribed a toothpaste containing >1400 ppm fluoride. The availability of these high fluoride toothpastes varies from country to country. They may only be available on prescription in some locations.

• Safe storage of all fluoride toothpastes is important to ensure young children do not eat paste from the tube. This advice to parents should be reinforced on a regular basis.

• Brushing with a fluoride toothpaste is at the heart of any preventive programme. There is no ‘right way’ to brush. The important goal is to make sure the toothpaste is used twice a day and not washed away by rigorous rinsing.

Fluoride mouth rinses

In some countries, school-based daily fluoride mouthrinse (0.05% sodium fluoride) programmes have been used to offer protection from dental caries. While rinses do offer a benefit, their use as a public health measure has declined for a number of reasons:

• The widespread use of fluoride toothpaste has reduced the potential benefits for the average child.

• Rinse programmes are labour-intensive, as children need to be supervised whilst rinsing.

• Schools may not want the inconvenience of a daily rinsing programme.

Nevertheless, in some countries where people live in remote locations and toothpaste is expensive, local school-based fluoride rinsing programmes can be an effective public health measure. Members of the dental team may also offer fluoride rinses to individual patients with active caries, provided they are over 6 years of age.

Two types of rinses are available.

Weekly

The most popular rinse is the daily one as it is simpler to rinse on a regular basis than trying to remember to use a product just once a week. Also maintaining a low level of fluoride in the mouth on a daily basis fits in with our understanding of the mode of action of fluoride on the remineralization of enamel.

It is important to use the rinse at a different time to brushing with a fluoride toothpaste as using them together does not offer an additive effect. A good time to rinse is when a child returns home from school, as there will be plaque present which incorporates the fluoride and releases it slowly over time.

There are a number of patient groups who will benefit from the prescription of a daily fluoride rinse:

• Children undergoing orthodontic treatment. The rinse can reduce demineralization around the brackets.

• Patients with hyposalivation due to medications or those with congenital absence of the major salivary glands.

• Children with medical problems for whom caries could be a serious problem, e.g. cardiac patients and individuals with bleeding disorders.

• Children with active dental caries.

• Some individuals who find toothbrushing difficult (but in many cases they will also find rinsing a problem).

Fluoride rinses are not recommended for children before the eruption of the permanent incisors because many younger patients will swallow the rinse and this may cause fluorosis.

Tooth mousse or casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate crèmes

CPP-ACP and CPP-ACPF are available as crèmes for topical application at home (Tooth Mousse®; Tooth Mousse Plus®, GC Corp, Japan) to be applied to surfaces at risk of caries, erosion or with white spot lesions. CPP-ACPF releases fluoride, calcium and phosphate ions for local remineralization of enamel (Reynolds, 2008).

The crème is applied to teeth after brushing by smearing across tooth surfaces with a clean finger or cotton-tipped applicator. The crème should not be rinsed out.

Fluoride tablets

At one time, fluoride tablets were widely recommended as a useful caries preventive measure. However, they have been superseded, as fluoride toothpastes now dominate the market and offer a better level of protection from dental caries. In addition, research has shown that compliance with tablet taking regimes is very poor and the consumption of up to 1 mg of fluoride in 1 tablet is linked to fluorosis. Thus fluoride tablets are no longer routinely recommended (Den Besten, 1999; Tubert-Jeannin et al., 2011).

Stannous fluoride gel

A stannous fluoride (SnF2) treatment gel in a methylcellulose and glycerine carrier (marketed as Gel Kam® by Colgate Oral Care) can be used at home for the remineralization of white spot and hypomineralization lesions of enamel (e.g. molar or incisor hypomineralization). Anecdotal clinical reports support the efficacy of this product, e.g. where localized remineralization is desirable prior to the placement of definitive restorations. The 0.4% stannous fluoride gel has also proved effective in arresting root caries and has been incorporated into a synthetic saliva solution to reduce caries in post-irradiation cancer patients.

Professionally applied fluoride products

Fluoride varnish

Varnishes were developed many years ago in order to prolong the contact time between the fluoride and dental enamel. As with fluoride rinses, varnishes have been used as both a public health prevention agent and as a specific treatment for individual patients in general dental practice (American Dental Association, 2006).

The efficacy of fluoride varnish in population health programmes to reduce dental caries has been called into question by recent research (Milsom et al., 2011), but a systematic review concluded that fluoride varnishes can offer a more than 40% reduction in dental caries (Marinho et al., 2009). However, the studies included in the review were undertaken before fluoride toothpaste had achieved total market dominance. The general presence of fluoride from toothpaste means that the use of varnish on a population basis does not offer an added advantage to the majority of participants enrolled in a varnish-based preventive programme.

The evidence on the value of varnishes for use on individual patients in primary dental care is not available but the ongoing relationship between a family and the dental team could be a positive factor in their efficacy. Varnishes can therefore be part of a prevention plan for individual patients, and indications for their use are:

• Hypersensitive areas of enamel and dentine.

• An alternative to fissure sealants on occlusal surfaces of permanent molars for apprehensive children until such time that effective sealant placement can be undertaken.

• Acclimatization for nervous children.

• Local remineralization of white spot lesions.

• As part of a preventive programme for children with active caries in the primary and/or permanent dentitions.

• A routine preventive measure for medically compromised and other special needs patients.

It must be stressed that the use of fluoride varnish for the control or prevention of dental caries is a long-term commitment (Sköld et al., 2005). It offers little value when used as a ‘one off’ intervention, and therefore should be applied at least three times per year for optimal effect. Varnishes are simple to apply; prophylaxis of the teeth is not required routinely as fluoride uptake is not reduced by surface plaque. In fact, plaque can serve as a recycling reservoir for fluoride and allow prolonged exposure to enamel. Drying teeth before application facilitates adhesion and may also be beneficial for fluoride uptake.

With such highly concentrated fluoridated products, great care must be taken to avoid using liberal amounts of varnish on young children. The manufacturer of Duraphat® (Colgate Oral Care) recommends application of the following amounts of varnish, which should not be exceeded:

Two readily available varnishes are:

• Duraphat® (Colgate Oral Care) – an alcoholic solution of natural varnishes containing 50 mg NaF/ml (5% NaF, 22 600 ppm F−). This varnish resin remains on the teeth for up to 12–48 h after application, slowly releasing fluoride from the wax-like film.

• Fluor Protector® (Ivoclar Vivadent) is a clear varnish which contains 0.9% difluorsilane in a polyurethane varnish base with ethyl acetate and isoamyl propionate solvents. The fluoride content is equivalent to 0.1% or 1000 ppm in solution. As the solvents evaporate, the fluoride concentration will increase to much higher values.

Concentrated fluoridated gels, foams, solutions and cremes

Concentrated fluoridated gels are marketed as both caries-preventive and treatment gels. There is recent clinical evidence that concentrated fluoridated gels are more effective in the permanent dentition than the primary dentition, benefiting particularly the first permanent molars. Variable dosage during application, followed by inadvertent swallowing, can result in the ingestion of large amounts of fluoride, which may contribute to mild fluorosis of mineralizing permanent teeth. Therefore, these products need to be used with great care and should not be offered to children under 10 years of age.

High concentration fluoride gels (e.g. 9000–12 300 ppm F−) should be limited to professional use in the dental practice and not dispensed for home use. Lower concentration gels (e.g. 1000 ppm F−) can be used at home following careful professional instruction. The use of these products has declined as fluoride varnishes are simpler to use and can be targeted on specific teeth.

Acidulated phosphate fluoride gels

Acidulated phosphate fluoride (APF) gels, containing 12 300 ppm F− (1.23% APF) consist of a mixture of sodium fluoride, hydrofluoric acid and orthophosphoric acid. There are also gels containing 5000 ppm F− which contain sodium fluoride, phosphoric acid and sodium phosphate monobasic.

• Such highly concentrated fluoride gels should be limited to professional use and should not be dispensed for home use.

• The incorporation of a water-soluble polymer (sodium carboxymethyl cellulose) into aqueous APF produces a viscous solution that improves the ease of application using custom-made trays.

• Thixotropic gels in trays flow under pressure, facilitating gel penetration between teeth.

Neutral sodium fluoride gels

A neutral pH gel (e.g. 2% w/v neutral NaF gel, 9000 ppm F−) can be used for cases of enamel erosion, exposed dentine, carious dentine or where very porous enamel surfaces (such as hypomineralization) exist.

• Sodium fluoride is chemically very stable, has an acceptable taste and is non-irritating to the gingivae. It does not discolour teeth, composite resin or porcelain restorations, in contrast to APF or stannous fluoride, which may cause discolouration.

• A neutral pH fluoridated gel or solution is preferred where restorations of glass ionomer cement, composite resin or porcelain are present as acidic preparations may etch these restorations.

Stannous fluoride solution

• 10% stannous fluoride may be used to target local ‘at-risk’ surfaces of teeth such as deep fissures and pits or white spot lesions on accessible proximal surfaces.

• Rapid penetration of tin and fluoride into enamel and the formation of a highly insoluble tin fluorophosphate complex coating on the enamel is the main mechanism of its action. The stannous ion may cause discolouration of teeth and staining on margins of restorations, particularly in hypocalcified areas.

Planning a preventive programme in the practice

Twice-daily tooth brushing with a fluoridated toothpaste beginning before 2 years of age together with dietary advice to reduce the frequency of consumption of sugary foods and drinks is the cornerstone of a preventive programme to ensure minimal caries activity. Reviews of epidemiological data in non-fluoridated communities indicate that the twice-daily use of a toothpaste containing fluoride will prevent new caries development in approximately 80% of children, and an estimated 60–70% of adults.

Members of the dental team offer care to many different families with varying levels of dental disease. It is important to tailor advice to maximize the benefit for each individual child. The aetiological factors leading to the development of caries are multifactorial, so risk assessment should involve all the likely key factors. Understanding the social, behavioural, microbiological, environmental and clinical factors still remain essential in the determination of caries risk during specific time periods.

Some authorities suggest that caries risk can be subdivided into moderate and high. Such definitions are somewhat arbitrary and it is more practical to focus on changing behaviour and prescribing appropriate preventive products for all children at risk of caries.

The scope of a preventive programme will be influenced by the following factors:

• white spot demineralization on cervical surfaces.

• visible deposits of dental plaque and/or gingivitis.

• new carious lesions visible on clinical examination or on radiographs.

• patients with orthodontic appliances.

• individuals who have chronic medical problems.

• children with special needs.

• frequent consumption of sugary foods and drinks.

Patients with these signs will alert clinicians to the importance of concentrating on preventive advice and therapies (Threlfall et al., 2007). The failure to guide and inform families on how to control and prevent caries may lead a child to suffer pain and require more clinical intervention. The preventive program can be a team effort utilizing the skills of the dentist, hygienist and dental therapist, each playing a part in the delivery of appropriate advice.

The preventive plan will have two themes:

Preventive products

It is well-known that all preventive plans must include a fluoride component in order to successfully control or prevent dental caries. The specific products will depend on the severity of the caries problem and the age of the child.

It is important to note that Early Childhood Caries in children under 3 years of age is primarily a dietary problem and fluoride products, whilst helpful, cannot overcome the constant intake of sugary foods and drinks. With that caveat in mind the preventive products at our disposal are:

• Fluoride toothpaste – children must brush twice a day with a family toothpaste. Parents are advised to use a smear of paste on the brush for children under 6 years of age.

• High strength fluoride toothpastes – these can contain 2800 to 5000 ppm fluoride and are usually only available on prescription or can only be purchased from pharmacies. These pastes offer a high level of caries protection but must be reserved for children over ten years of age and used as recommended by the dental team. May not be available in some countries.

• Fluoride varnishes – these are easy to apply and can be directed to specific lesions. They have a high concentration of fluoride so should be used sparingly. Varnishes need to be part of an ongoing programme and should be placed at least three times a year. Once the caries is under control the varnish applications will no longer be required.

• Fluoride gels/solutions – these can be used in a similar way to varnishes. They are not straightforward to apply and varnish has superseded their general use.

• Fluoride mouthrinses – these offer a proven benefit, but rinsing should not take place at the same time as brushing. Arriving home from school is a good time for rinsing. Not suitable for children under 6 or those individuals who cannot spit out the rinse.

• Fissure sealants – these are of great value especially on the vulnerable surfaces of first and second adult molars. The enamel structure of primary molars may compromise sealant adhesion as etching is not as effective. Resin based sealants are very technique sensitive so are of little value if moisture control is difficult to achieve.

• Tooth Mousse® – this product may have preventive benefits with ongoing use in controlling demineralization lesions, such as around orthodontic appliances.

Behaviour change

Whilst fluoride products have revolutionized the success of caries preventive programmes it is still important to explain to parents/carers the multifactorial nature of the caries process. Our focus should be on diet and toothbrushing.

• Diet – reducing the frequency of consumption of sugary foods and drinks is the dietary goal. How this is achieved is dependent on the age of the child and the cooperation of the parents. This chapter is essentially focusing on fluoride products, but dietary analysis is a key skill for the dental team, hence it being highlighted here.

• Toothbrushing – this is a behaviour which if embedded early in a child’s life offers a proven benefit because it delivers fluoride toothpaste twice daily on a regular basis. In addition, as the child matures, removing plaque and controlling gingivitis becomes more important. For caries control however, the dental team needs to make sure a child brushes twice a day. There are different strategies for achieving this such as disclosing plaque, using toothbrushing charts and suggesting electric toothbrushes. The essential point is to make sure parents and carers monitor the brushing.

However, dental caries for many of our child patients will not be a major problem and our strategy should be to encourage healthy behaviour and highlight possible risk factors to parents and carers. These families can be classified as low risk, but must be given advice to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

The helpful pointers to low risk are:

• No new carious lesions within last 12 months.

• Little plaque noted on the cervical regions of the teeth.

• Parents report that child brushes twice a day with a fluoride toothpaste.

• Visits your practice once per year.

• Frequency of consumption of sugary drinks and foods is controlled.

Although a child may be at ‘low risk’ to caries, there are some standard actions which will be helpful in maintaining the status quo:

• Reinforce diet advice concentrating on limiting sugary snacks and drinks between meals.

• Appropriate fissure sealants on newly erupted first and second permanent molars are helpful.

• Children over 6 years of age should be advised to use a family strength fluoride toothpaste.

These simple behaviours will ensure your patients remain at very low risk of developing dental caries. Research suggests that a child with one carious lesion is five times more likely to develop further disease when compared with a child who is caries-free and as such, timely advice to parents is extremely important. This huge difference in risk highlights the importance of primary prevention and should be an essential part of the practice policy.

Techniques for toothbrushing

There are many ways advocated to clean teeth and remove plaque. In reality, the horizontal ‘scrub’ technique is the one usually employed by most people. It should be simply put that the plaque should be removed from:

• The ‘biting surfaces’ (occlusal) – using a vigorous scrubbing technique.

• All the gum margins (gingival margin) using a circular motion.

• Both sides of the teeth (labial/buccal and lingual/palatal) using a circular motion similar to above.

The one spot most poorly cleaned are the labial gingival margins of the lower anterior teeth. This is a naturally sensitive and difficult area to access, which children and parents need to be taught how to clean. It should be stressed that gingival tissues should not bleed following brushing at any age and this sign highlights the need to clean these areas more effectively. Furthermore, the current recommendation should be that children do NOT rinse following brushing. They may spit out at the end of brushing but be encouraged to swallow the residue (Figure 5.2). This is based on the qualification that the appropriate amount of fluoride toothpaste has been placed on the brush.

Figure 5.1 Different severities of fluorosis. (A) Very mild fluorosis with opacities following the outline of the perikymata. The primary teeth are unaffected. In younger children, the enamel is generally more opaque. (B) In an older child, the translucency of the incisal edge is evident but the opacities follow the same horizontal lines of the perikymata. (C) Mild fluorosis with white flecking through the crowns of the incisors. Note that the lower incisors are only minimally affected. This is still a surface opacity that will improve over time or may be conducive to treatment with microabrasion. (D) Moderate opacity affecting the whole crown. Note that the pits and brown mottling is secondary to tooth-surface wear and the acquisition of stains. (E) Score 6; Staining of intact enamel and discrete pitting. (F) Score 6; A more severe appearance with significant loss of enamel.

Dental fluorosis

Dental fluorosis is a qualitative defect of enamel resulting from an increase in fluoride concentration within the micro-environment of the ameloblasts during enamel formation (Aoba & Fejerskov, 2002). Mild fluorosis is characterized by opaque lines following the perikymata. With increasing severity, the opaque lines merge and more irregular cloudy areas become visible. More severe cases will have a totally opaque chalky appearance. In a small number of cases, there will be punched out pits and the outermost enamel will be gradually lost (Figure 5.1).

The dental profession must consider very carefully their fluoride regimes for children aged 1–6 years, as this is when the enamel of the upper anteriors is forming and the appearance can be compromised. It is interesting to note that most studies show people do not notice mild fluorosis.

Parents of children under 6 years of age should:

• Supervise brushing to check on fluoride toothpaste usage.

• Place a smear of paste on the brush.

• Store the toothpaste out of reach, so that a child will be unable to eat or suck the toothpaste.

• Avoid giving children 1 mg fluoride supplements.

• Not give baby vitamin drops containing a fluoride supplement.

• Carefully check with a member of the dental team why a high fluoride treatment is being suggested in their child’s care plan.

A number of indices have been developed to record dental fluorosis. The earliest widely accepted index was developed by Trendley Dean and published in 1942 (Dean, 1942). His index of Dental Fluorosis recorded the appearance of the teeth ‘wet’. The dentition was not air dried prior to assessment. This is extremely important, as it records the appearance of the teeth in their natural state. Subsequent indices dry the teeth and fluorosis will become more apparent as the enamel becomes desiccated.

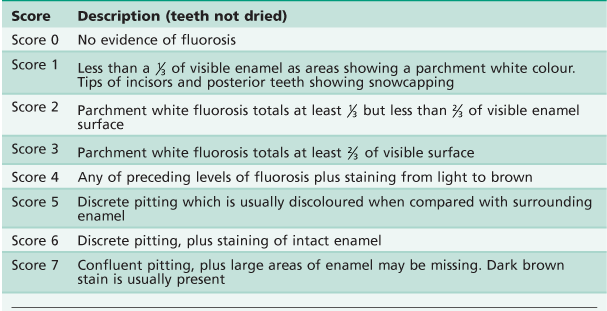

Dean’s index has been modified by a number of researchers over the years, to give greater sensitivity; in particular Horowitz and others (1984) improved the index (see Table 5.1).

The other index that has found favour was developed by Thylstrup and Fejerskov in 1978. However, it is assessed when the teeth are dry and this may exaggerate the appearance of fluorosis. Nevertheless, as a research tool investigating the impact of fluoride on enamel development, it has been very useful.

Dean used his index to suggest that the 1 ppm level of fluoride in reticulated public water supplies would give the best reductions in dental caries with the least fluorosis. The appearance of fluorotic enamel changes over time with natural abrasion of the outer surface of the teeth, especially in cases of mild fluorosis.

Dental fluorosis primarily affects permanent teeth and is a dose-related condition. A diagnosis of dental fluorosis requires a detailed history of fluoride exposure. Excessive fluoride may have several detrimental actions on enamel formation including:

• Alteration of the production or composition of enamel matrix during ameloblastic secretory phase.

• Interference in the initial mineralization process caused by changes in ion-transport mechanisms.

• Disruption of ameloblast function affecting the withdrawal of protein and water from initial mineralization of enamel during the maturation phase.

• Disruption of nucleation and crystal growth in all stages of enamel formation, resulting in various degrees of enamel porosity (hypomineralization).

• Enamel mineralization appears uniquely sensitive to fluoride, and high doses of fluoride can affect breakdown and withdrawal of enamel matrix proteins (e.g. enamelins, amelogenins), resulting in permanent hypomineralization of enamel (subsurface and surface porosity). High doses of fluoride also seem to affect the activity of the ameloblasts.

• Excessive fluoride intake is of particular concern, especially during the first 36 months of life when crowns of the maxillary permanent incisors are undergoing mineralization or enamel maturation.

Clinically, dental fluorosis can be managed by remineralization, microabrasion or restorative replacement of the affected discoloured enamel and is discussed in more detail in Chapter 11.

Fluoride toxicity

Overwhelming evidence exists for the safety of fluorides at low concentration but high concentrations increase the possibility of toxic overdose. It is important to use high strength fluoride products with great care, especially in children under 4 years of age, but it is also prudent to advise parents about the safe storage of fluoride toothpastes.

Estimated probable toxic dose

• Gastrointestinal symptoms have been noted following ingestion of 3–5 mg F−/kg by young children and very frail adults.

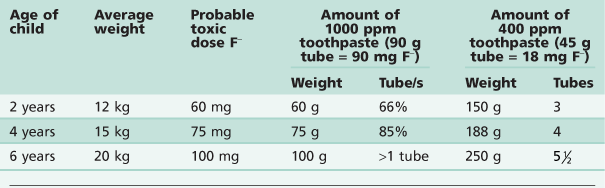

• For a 10 kg child, this corresponds to all the contents of a 45 g tube of toothpaste. Therefore, young children should not be allowed unsupervised access to fluoride toothpastes or fluoride supplements. Table 5.2 gives information on the amount of toothpaste which will cause a probable toxic fluoride dose.

Probable toxic dose (Table 5.2)

• 32–60 mg F−/kg of body weight.

• Fatalities in children have been reported at doses of 16 mg F−/kg of body weight. A number of concentrated topical preparations could provide such levels for young children if used in a single dose.

The inappropriate prescription of home-fluoride treatments with high concentration fluoridated gels for very young children (e.g. in the management of early childhood caries) and inappropriate use of high fluoride products in the dental office, are of concern (Evans & Stamm, 1991). It must be emphasized that fluoride cannot control ECC in very young children without a change in diet, especially modification of the use of a night-time bottle or the use of bottle during the day as a comforter.

The management of acute fluoride toxicity consists of:

• Estimating the amount of fluoride ingested.

• Minimizing further absorption.

If vomiting has not occurred spontaneously:

• Give as much milk as can be ingested or.

• Administer orally 5% calcium gluconate or calcium lactate or milk of magnesia.

While this immediate action is being taken, the hospital should be advised that a case of acute fluoride poisoning is in progress so that preparation for the appropriate therapeutic intervention can be made.

Note that while previous protocols advocated the use of an emetic, there has been a move away from encouraging vomiting because of the risk of aspiration of vomitus and burning the oesophagus by the hydrofluoric acid formed in the stomach, by the interaction of fluoride with hydrochloric acid. Modern emergency department protocols advocate the use of activated charcoal or gastric lavage in most poisonings.

Clinical implications

The practice of paediatric dentistry requires the dental team to be reflective and spend time carefully evaluating clinical problems prior to action. Once a diagnosis has been made, there are two key themes which must be part of practical care plans.

Further reading

1. Adair SM. Evidence-based use of fluoride in contemporary pediatric dental practice. Pediatric Dentistry. 2006;28:133–142.

2. American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Professionally applied topical fluoride: evidence-based clinical recommendations. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2006;137:1151–1159.

3. Aoba T, Fejerskov O. Dental fluorosis: chemistry and biology. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 2002;13:155–170.

4. Burt BA, Keels MA, Heller KE. The effects of a break in water fluoridation on the development of dental caries and fluorosis. Journal of Dental Research. 2000;79:761–769.

5. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. MMWR. 2001;50(RR14):1–42.

6. Davies GM, Worthington HV, Ellwood RP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of providing free fluoride toothpaste from the age of 12 months on reducing caries in 5–6 year old children. Community Dental Health. 2002;19:131–136.

7. Dean HT. The investigation of physiological effects by the epidemiological method. In: America Association for the Advancement of Science. Washington DC: Publication Number; 1942;23–31. Moulton FR, ed. America Association for the Advancement of Science vol. 19.

8. Den Besten PK. Biological mechanisms of dental fluorosis relevant to the use of fluoride supplements. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 1999;27:41–47.

9. Downer MC, Blinkhorn AS. The next stages in researching water fluoridation: Evaluation and surveillance. Health Education Journal. 2007;66:212–221.

10. Evans RW, Stamm JW. An epidemiologic estimate of the critical period during which human maxillary central incisors are most susceptible to fluorosis. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 1991;51:251–259.

11. Franzman MR, Levy SM, Warren JJ, et al. Fluoride dentifrice ingestion and fluorosis of the permanent incisors. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2006;137:645–652.

12. Horowitz HS, Heifetz SB, Driscoll WS, et al. A new method for assessing the prevalence of dental fluorosis: the Tooth Surface Index of Fluorosis. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1984;109:37–41.

13. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Logan S, et al. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009;(109):CD002279.

14. Milsom KM, Blinkhorn AS, Walsh T, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial Fluoride varnish in school children. Journal of Dental Research. 2011;90(11):1306–1311.

15. Reynolds EC. Calcium phosphate based remineralization systems – scientific evidence. Australian Dental Journal. 2008;53:268–273.

16. Sköld UM, Peterson LG, Litt A, et al. Effects of school based fluoride varnish programs on approximal caries in adolescents from different risk areas. Caries Research. 2005;39:273–279.

17. Threlfall AG, Hunt CM, Milsom KM, et al. Exploring the factors that influence general dental practitioners when providing advice to help prevent caries in children. British Dental Journal. 2007;202(4):E10.

18. Thylstrup A, Fejerskov O. Clinical appearance of dental fluorosis in permanent teeth in relation to histological changes. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 1978;6:315–318.

19. Tubert-Jeannin S, Auclair C, Amsallem E, et al. Fluoride supplements (tablets, drops, lozenges or chewing gums) for preventing dental caries in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011.

20. Walsh T, Worthington HV, Glenny AM, et al. Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010.