Children with special needs

Neeta Prabhu, Wendy J Bellis and Angus C Cameron

Introduction

Although the oral health of people with disabilities is similar to the rest of the population, it is generally accepted that many persons with disabilities have extensive treatment needs, which for a variety of reasons, are not adequately met. Throughout the world, the standards of oral healthcare for this population have failed to achieve what would normally be expected for those without a disability.

What is special care dentistry?

It is a discipline targeted to meet the needs of individuals with a variety of limitations that require more than just routine dental care.

A disability may be:

Barriers to care and philosophies of management

Access to dentistry is often influenced by:

• The attitudes and willingness within the dental team to treat special needs children.

• A perception that the clinician may not have the skills or have the facilities to manage their care.

The successful management of these children depends fundamentally on the dentist’s ability to:

Consent

Providing dental care for people with cognitive impairment who are unable to consent to treatment can raise ethical and legal problems for the practitioner. There is variation in the practice of consent ranging from the ability of an individual to legally consent to their own treatment to the delegation of authority to their parents, caregivers or a guardianship board. Because these ethical predicaments are not obscure, healthcare professionals who routinely care for such patients must complement their clinical skills with their ability to recognize and clearly address these legal responsibilities.

Where are special needs children to be managed?

General dentists have often expressed concerns about a lack of adequate training in appropriately managing these patients in practice, leading to an increase in the number of referrals to the tertiary hospitals. While there has been an overall strategy of integration and normalization of these individuals into mainstream society, unfortunately, most have become reliant on the already stretched hospital-based healthcare system leading to extended waiting times. It must be emphasized that children with special needs require dental appointments that are tailored to make best use of their abilities. The majority of children can be managed successfully in a general practice setting with appropriate training of the dental team. All of the required preventive and maintenance programmes and much of the restorative work can be performed under local anaesthesia and/or sedation. However, there will always be a cohort for whom dental treatment under general anaesthesia is the only alternative. This incurs high costs and has its own problems of access and additional risks and should be recommended only when all other forms of behaviour management have failed or are clearly inappropriate. Additionally, the patient’s ability for oral health maintenance postoperatively must always be factored in the treatment planning process to avoid the misuse of these expensive facilities.

There is no doubt that the provision of care for many children with disabilities is challenging. Clinicians should be aware of their own limitations and should consider who and where the child is best managed.

Prevention

The best means of establishing good oral health is by a combination of early contact with dental services and increasing the awareness of regular dental check-ups. Many studies have demonstrated that certain groups of people with disabilities can be instructed in oral hygiene measures if sufficient encouragement and motivation was provided. It is important to introduce these measures from an early age and clinicians should not be deterred from providing comprehensive preventive programmes.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common developmental disorder affecting about 3–5% of the population. The term ADHD is currently used to describe a range of children with varying functional difficulties, but who share the feature of poorly sustained attention. The exact causes remain unknown, however most theories indicate abnormalities in the brain function that are mostly genetic in origin.

Features of ADHD

• Boys are affected much more commonly than girls.

• They are characterized by developmentally inappropriate degrees of impulsivity, inattention and often hyperactivity.

• The symptoms arise in early childhood, usually well before school entry and are present in all settings.

• Some children are extremely impulsive, some aggressive, others quiet and restless. Many have low self-esteem.

• Comorbidities include developmental language disorders, anxiety, oppositional-defiant behaviours, fine motor and coordination difficulties and specific learning disabilities.

• Virtually all children with ADHD have deficits in short-term auditory memory.

Assessment

The assessment of a child for the diagnosis of ADHD requires a number of essential components including:

• Detailed developmental history.

• Physical, neurological and neurodevelopmental examination.

• Detailed standardized behaviour rating scale data from at least two sources, usually school and home and psychometric testing (e.g. Conners’ Parent and Teacher Rating Scale; ADD-H Comprehensive Teacher’s Rating Scale; Child Behaviour Checklist).

Management

Management of the child with ADHD involves three broad approaches:

Many other approaches are commonly applied to these children, including dietary modification, ‘natural’ or complementary therapies of diverse types and behavioural optometry, however, there is little evidence to support the broad use of any of these interventions, though some individuals report benefits.

Pharmacological management

Psychostimulant medication is the principal pharmacological therapy for ADHD. The two stimulants most commonly prescribed are methylphenidate (Ritalin) and dexamphetamine.

• Onset of behavioural effect is usually noticeable within 30–60 min of ingestion.

• Significant clinical improvements in approximately 75% of correctly diagnosed children.

• Common oral side-effects include dry mouth. Some of the medications can cause adverse interactions with drugs commonly used in dentistry, e.g. local anaesthetics and therefore monitoring vital signs during dental treatment is essential.

• Other medications sometimes used in ADHD include the antihypertensive drug clonidine, antidepressants (selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and tricyclics) and occasionally neuroleptics.

Dental implications

The visit to a dentist is likely to raise anxiety levels in any child and indeed their parents. In a child with ADHD, this anxiety may manifest in overexcited behaviour and many parents worry about the effect of their child’s behaviour on others. They have become accustomed to failure having taken their ‘difficult’ child to dentists only to be told that it is not possible to provide treatment/care. This may result in either an excessively protective/embarrassed parent with constant apologies on behalf of the child or else an overly firm parent exerting inappropriate, heavy-handed disciplinary actions throughout the encounter. In either situation, the child’s behaviour is likely to be reactive towards the parent, thus precluding the establishment of a successful relationship with the dental practitioner.

Successful management of these children may be facilitated using similar strategies to those employed in other disabilities.

• It is important that the patient and the parent are managed positively and with confidence. By creating an atmosphere of confidence, the parental anxiety is often alleviated allowing the child and the dentist to establish a relationship in a more relaxed environment. Similarly, a gentle but firm approach will convey to the child a confidence and structure to the situation within which it is easier for them to conform.

• It is useful for the practitioner to have an understanding of the current management strategies being employed by the family at home and in school and to adopt these techniques in order to maximize success in the dental clinic. For example if a child is used to raising their hand prior to speaking, it is useful for the dentist to employ the same strategy. Clear instructions should be given to the child maintaining eye contact throughout and taking care not to over burden the short-term memory. Such instructions need to be given at a time when the child is not distracted by other activities in the dental surgery.

• The use of the tell-show-do method of behaviour direction has been shown to have value in the management of children with ADHD. Praise and encouragement have an important role in the management of these children and good behaviour should be reinforced and rewarded.

Management strategies

• The current medication scheme should be discussed with both the parents and the prescribing practitioner. It may be helpful to either change the dose or the timing of medication to optimize the action at the time of the dental visit. There is also some suggestion that morning appointments may be more successful, however this may be related to the timing of medication rather than anything else.

• A preventive approach is essential. Tooth brushing and controlling diet both require concentration, motivation and understanding, all of which can be problematic for the child with ADHD. Tooth-brushing charts for the child to take home and mark off daily are more likely to be successful than verbal instructions to brush daily.

• Repetition is important in building up self-confidence in the child.

• Multiple short visits have a higher chance of success than a few, prolonged visits.

• Inhalation sedation can be a particularly useful adjunct to non-pharmacological behaviour management techniques.

• Finally, it is important to realize that oral health is only one of many priorities for the family of a child with ADHD, and the multiple demands made of the parents need to be weighed against the need for dental care. Again, it is important to realize that many of these children are already struggling to master other life skills.

Autistic spectrum disorder

Autism or autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) is defined as a severe developmental disorder characterized by the classic triad of impairments:

ASD is polygenic in origin, however, there are still aspects of the aetiology that are not fully understood. Approximately 50% of affected children also have moderate to severe learning difficulties and there may be other comorbidities such as Fragile X, Rett syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, PKU and epilepsy. As ASD is predominantly a genetic condition, there may be other family members who are affected, including the parents themselves.

Asperger syndrome

Asperger syndrome is a form of autism. These children have fewer problems with speaking and are often of average or above average, intelligence. They do not usually have the accompanying learning disability associated with autism, but they may have specific learning difficulties.

Problems associated with the dental treatment of a child with ASD

The dental management of children with autism can be a huge challenge for the paediatric dentist, mainly because of the child’s behaviour and their impaired communication.

Impaired communication

• Children may have limited speech and language.

• Augmentative communication aids such as Makaton or Pictorial Exchange Communication System (PECS) may be required once the degree of learning disability is ascertained.

• Impaired reciprocal social interaction and lack of eye contact is common. Children with ASD do not understand humour.

• Children are unable to imagine what someone else is feeling (‘theory of mind’).

Impaired behaviour

• Behaviour may be erratic, disruptive and difficult to predict.

• Both the child and parents may be highly anxious about a visit to the dentist.

• The child may be resistant to change, especially in a new and unfamiliar environment and may show signs of self-injurious behaviours.

• Some children may have a persistent occupation with objects like buttons, beads, etc. (sensory stimulus) and can engage in repetitive body movements.

• Remember, in most cases, conventional behaviour management techniques do not seem to apply.

Sensory problems

Many children with ASD have problems with sensory processing and consequently may be hyper- or hyposensitive to sights, sounds, smells and tastes in their environment. They may have an elevated pain threshold and are also known to restrict their diet to certain foods only. Sensory overload and anxiety can result in extreme behaviours such as ‘meltdown’.

Medication

Many medications may cause xerostomia and some may not be sugar-free in some countries.

Trauma

Injury to anterior teeth is not uncommon due to the association with epilepsy and dyspraxia.

Late diagnosis

Difficulties and delays in confirming the diagnosis of ASD often results in a delay in accessing early preventive dental care.

Problems with therapies

Linked to the huge number of proposed therapies, there may be dietary restrictions and limitations imposed on specific dental materials. Confectionery may be being used for the reinforcement of good behaviour and as part of a behavioural approach.

Clinical management

Dentists are one of the few professionals who we permit to enter our personal space. Many people find this uncomfortable but understand that the dentist needs to be so close in order to examine teeth. For children with ASD, this close proximity may well be extremely distressing.

Therefore, prevention is the key element to managing these children. Local anaesthesia and inhalation sedation is limited to the higher functioning children with autism, where their communication is not severely compromised.

General anaesthesia and deep sedation are the most frequently used approaches, especially for those children who are young and present with extensive disease. Such treatment should obviously be definitive and comprehensive, including preventive as well as curative elements.

Important tips for management

• Make contact with the families as soon as possible to encourage early access to services through the local child health networks and development teams.

• Send out a pre-appointment questionnaire-style letter and an information leaflet.

• Familiarize yourself with the different communication aids that the child may be using. Photographs or images can be put together in the form of a storyline/social story, so that the child is prepared for the dental visit. End the social story (book) with a ‘reward picture’. This helps to reduce a build-up of anxiety by making events more predictable for the child.

• Establishing the behaviour of tooth brushing as early as possible is extremely important for these children, not only for oral health and fluoride delivery but also, it is the most successful way of initiating a dental examination.

• Utilize behavioural approaches such as Applied Behavioural Analysis to establish patterns of behaviour around tooth brushing and also to teach the child to accept a dental examination.

• It may not be the actual brushing that the child dislikes, it may be the taste of the paste and the oral sensation. Explore other flavours and low foaming options.

• Some echolalic children (automatic repetition of vocalizations) are able to copy words and expressions, and if this applies to the treating dentist, then the parents can be taught to encourage the child to say ‘AHHHH’. This not only helps the parent to brush, it allows the dentist to examine the teeth visually, and also facilitates examination of the pharynx by the child’s medical practitioner. The sound ‘EEEEEEE’ can help display the upper anterior gingival margins, that are sometimes difficult to access (Figure 13.1).

Figure 13.1 Encouraging echolalic children to copy expressions can aid examination and access to the oral cavity. (A) The ‘AHHHH’ sound helps open the mouth, while the sound ‘EEEEEEE’ (B) helps with access to the anterior teeth.

• Actively look for evidence of trauma because of the association with epilepsy or self-injurious behaviours.

• Frequent visits to the dental setting will provide opportunities to learn about the child and give preventive support (‘Hello visits’).

• Dietary advice must be specific to each individual child. If dietary reinforcers are being used, encourage the use of low-sugar safe snacks and consider the use of sugar-free confectionery.

• Establish time indicators. It is important to help the child realize that this experience does have a time limit. Visual or auditory timers (e.g. sand timers, buzzers, watch alarms), will help them understand this and also to monitor the length of the experience.

Maximizing communication with autistic spectrum children

• Position yourself so that the child can see you.

• Get their attention by using the child’s usual name at the beginning of the sentence.

• Use simple language without jokes, sarcasm or jargon.

• Use a minimum of social language and avoid ‘Childrenese’.

• Speak slowly to allow information to be processed.

• Limit any background noises in the surgery and use the same staff and a secluded dental surgery if possible.

• Positive re-enforcement of desired behaviour should be ‘celebrated’ so that it is repeated. If the patient gets aggressive, maintain an unresponsive facial expression and use a calm tone.

Paediatric dentists who care for a large number of these children need to have a full understanding of the nature of ASD and the specific issues around their care. It is important to remain flexible in order to meet the challenges which these children can present in the dental environment.

Developmental disabilities and intellectual disabilities

Developmental disabilities are described as differences in neurological-based functions that have their onset before birth, or during childhood, and are associated with long-term difficulties. People with intellectual disability have an IQ of <70, deficits in adaptive functioning and an onset before 18 years of age. The term developmental disability includes all people with an intellectual disability; however, not all people with a developmental disability have an intellectual disability. For example, children with cerebral palsy and autism have a developmental disability, but not all of them will be intellectually disabled.

Tips for management

• The first appointment is often one in which to familiarize both the dentist with the child’s condition and the child with the dental environment.

• Consultation with the family and caregivers helps in finding out the patient’s likes, dislikes and behaviour patterns.

• Determine each individual’s level of communication; do not treat them as a ‘homogenous group’. Be aware of your body language (non-verbal communication). Do not patronize but share the same social courtesies.

• Always allow extra time for your patients to familiarize; keep consistency with staff if possible. Short early morning appointments are preferable.

• Allow time for introduction of new concepts; prior explanation (announce each step) has better acceptance with patients as well as parents and caregivers.

• Repeat instructions when needed; offer praise and reinforce good behaviour. Be sensitive to your patient’s gestures. Ask direct closed Yes/No questions.

• Developmental delay is a broad term covering children with a range of medical conditions and syndromes. It is essential that obscure syndromes be researched before performing treatment. Photocopy relevant information for the child’s file.

• Support of the parent or caregivers is extremely important in reinforcing and administering preventive advice, oral hygiene practices and diet modification. Consultation with the school or institution may be required to modify diet.

Problems associated with intellectual disabilities

Management of poor plaque control

Patients with intellectual disabilities require assistance to maintain adequate oral hygiene to prevent gingivitis and periodontal disease. Carers should be trained in techniques to deliver oral care in a safe and effective manner. With some patients that may be tactile-defensive, referral to a speech pathologist for an oral desensitization programme prior to commencement of any oral hygiene programmes may be beneficial. These programmes include vibration and extra-oral massage to treat tactile-defensive behaviour. The upper front teeth and gums are the most sensitive regions and therefore avoiding these areas until after complete desensitization of the oral cavity will assist in increasing compliance with tooth brushing.

Adjuncts to oral care

• When brushing, the parent or carer should stand behind and above the child whenever practicable to facilitate control of the head and the brush. This also aids better visual access. Other positions might include swaddling very young children; brushing while still in the wheelchair/feeding chair or sitting on the floor (Figure 13.2).

Figure 13.2 Sitting on the floor, supporting the child from behind facilitates tooth brushing and oral hygiene for infants and young children with disabilities.

• A flexible ‘3-headed toothbrush’ simultaneously brushes the gums and teeth making it easier for those with limited dexterity. It covers the entire tooth surface and is ideal for use in individuals with short tolerance or attention span. Other toothbrushes with large handles assist patients with disabilities (Figure 13.3).

Figure 13.3 (A) Three-headed toothbrush. (B) A range of toothbrushes designed to facilitate improved brushing for patients with disabilities.

• Although electric toothbrushes have smaller heads and are easy to use, they run the risk of breaking or splitting inside the mouth and should be used with caution.

• Foam oral swabs (Figure 13.4) help to gently remove debris from the mouth in between brushing. They can be dipped into warm water, mouthwash or sodium bicarbonate (0.2%), however, they should not be substituted for regular tooth brushing.

Malocclusion

There is a higher incidence of hypotonicity and hypertonicity of oral musculature in people with intellectual disabilities. These patients may also have unusual oral habits such as tongue thrusting, which creates malocclusions. Many patients with intellectual disabilities will be able to manage conventional orthodontics with an appropriate level of support including with the use of relative analgesia or sedation. However, for those patients with challenging behaviours, conventional orthodontics may not be possible. An orthodontist may consider interceptive orthodontic measures that might reduce the degree of malocclusion and the need for appliance wear. Early referral and consultation is beneficial for all children with a disability, who are developing a malocclusion in the mixed dentition stage.

Management of tooth-wear in the patients with an intellectual disability

Study models should be taken at the earliest signs of tooth-wear to establish the rate of tooth-wear over time. The causes of the tooth-wear should be established and if possible, eliminated. Gastro-oesophageal reflux is common in people with developmental disabilities and must be addressed by appropriate referral to gastroenterology. The incidence of tooth grinding is also higher in this population and should be addressed where possible by appropriate means.

Only treat the tooth-wear restoratively if there is:

The restorative treatment of choice is overlaying of worn teeth using an indirect composite resin material with minimal tooth preparation. Two treatment sessions using sedation will be required for many patients with developmental disabilities to adequately take impressions and maintain isolation for cementation procedures.

Tooth grinding

Many parents and caregivers seek dental consultation because of tooth grinding and the worry or associated dental damage it can cause. It can be a social problem for families, teachers and caregivers and consideration should be given as to whether or not the behaviour has other implications such as attention seeking in changed family circumstances. Tooth grinding is either physiological or pathological. It is quite commonly seen in individuals with neuromuscular and learning difficulties.

Physiological tooth grinding (Figure 13.5)

• Often occurs during times of concentration or at night during sleep, although it may occur at any time.

• Begins early during the development of the primary dentition usually once the primary first molars erupt.

• Usually diminishes once the primary teeth have exfoliated.

• No treatment is usually required other than parental reassurance.

• Use of soft or hard acrylic splints is indicated to protect the teeth, however, if the wear is excessive threatening pulp exposure, then restorations using stainless steel crowns or extractions are indicated.

• Unusual to reflect any generalized systemic condition and dental anthropologists regard this grinding as a phenomenon of ‘tooth sharpening’ termed ‘thegosis’.

Pathological tooth grinding

• The amount of wear exceeds that which is felt to occur normally. Children may lose up to half the crown length in upper anterior teeth. Extensive enamel loss with wear facets and exposed dentine is unusual in posterior teeth.

• Often seen in children with underlying neurological disorders or medical problems such as Down syndrome, cerebral palsy or head injury. It has been hypothesized that tooth grinding in these patients stimulates endorphin production and is perceived to be a pleasurable activity.

• An increase in grinding intensity in these children may reflect other pathology such as otitis, salivary gland infection or generalized pain elsewhere in the body.

Management of tooth grinding

• If there has been extensive loss of tooth structure in the primary dentition, it will be essential to monitor any changes in the first permanent molars. Treatment may involve the placement of stainless steel crowns on the second primary molars. This will not only protect the permanent teeth but preserve the vertical dimension of occlusion and tends to decrease grinding.

• Tooth grinding that is associated with self-mutilation of the soft tissues is extremely difficult to manage and some strategies have been discussed in Chapter 8.

• It must be noted that when, in the more severe cases, extractions of permanent teeth are contemplated, eventually, all teeth will probably be lost. For those cases of intractable grinding and self-mutilation, the removal of only a few (anterior) teeth invariably leads to removal of all teeth in the arch.

• It is also important to identify other intrinsic or extrinsic factors such as reflux or an erosive diet that would contribute to further tooth surface loss.

Self-mutilation (Figure 13.6)

A number of conditions exist which present with self-mutilation:

• Hereditary sensory neuropathies (congenital insensitivity to pain syndrome).

• Lesch–Nyhan syndrome (hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase deficiency).

• Hereditary neuropathies are rare inherited disorders affecting the number and distribution of small myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibres. Most categories in classification systems arise from the varied clinical presentations – terms used have included congenital indifference or insensitivity to pain, dysautonomia, sensory anaesthesia, painless whitlows of the fingers and recurrent plantar ulcers with osteomyelitis.

The term ‘indifference to pain’ in these cases, is a misnomer in that indifference implies a cerebral inattention or cognitive dysfunction. Those patients with ‘indifference’ correctly receive painful stimuli but fail to react in the usual defensive manner by withdrawal. In those patients with ‘insensitivity to pain’, the deep tendon reflexes are preserved, as these are controlled by large-diameter myelinated fibres. The lack of pain perception is due to a true peripheral neuropathy.

Figure 13.6 (A) Self-mutilation in a child with a peripheral sensory neuropathy. This child presented with exfoliation of the anterior teeth. She was investigated for many of the conditions described above until it was discovered that she herself was pulling out her teeth. Having no sensory nerve endings, she could feel no pain. (B) Finger-biting can also be a manifestation of neuropathies. (C) An appliance to prevent self-injury. All cases are different and an appliance that is successful in one patient may not prove to be appropriate in another. (D) A lower acrylic splint to cover the teeth and prevent tongue biting. The holes on the labial aid in retention of the cement.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of these conditions is often made by exclusion and by careful observation of the child. It is not uncommon for many months to pass before a correct diagnosis is made and, in the absence of other pathologies, parents or caregivers may incorrectly be suspected of child abuse or Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Because of an inability to recognize or feel pain, these children may avulse teeth and inflict extensive trauma to the gingivae, tongue or mucosa with their fingers or by biting and chewing. Self-inflicted ulceration (factitious ulceration) may also occur as a habit (akin to nail biting) but may also be a manifestation of psychological disorders.

Management

• Selective grinding of tooth cusps or ‘dome’ build-ups of the occlusal table with composite resin to produce a smooth surface.

• Acrylic splints or cast silver splints to prevent gross laceration of the tongue or fingers.

• Extraction of teeth may be required as a last option in severe cases.

Initial management in young children often necessitates restraint to prevent these children from injuring themselves. Even for the most vigilant parents, constant supervision is impossible and invariably, these children will continue to sustain injuries despite the best care. The involvement of occupational therapists is invaluable to support parents and institute protective measures in the home such as the use of padded clothing, arm splints, helmets and other protective devices. Where lacerations to the tongue and other soft tissues occur, mouth guards and other appliances which prevent the teeth from occluding are required. Lower appliances are generally more suitable than those placed in the upper arch. In severe cases where the mutilation is intractable, botulinum toxin A (Botox) has been used to selectively paralyse the major mandibular elevator muscles (medial pterygoid and masseter).

Prognosis

The prognosis for most children with peripheral sensory neuropathies is poor and, in one case managed by one of the authors, the child died of an undiagnosed pneumonia before 3 years of age. Children tend to have repeated hospital admissions, fractures of long bones, injuries to the extremities and recurrent chronic infections. This pattern of repeated traumatic injuries is characterized in one such patient:

• Premature loss of all lower anterior primary teeth.

• Chronic ulceration of the lower alveolus.

• Second degree burn to right forearm from a radiator.

• Fracture of left humerus (during hospital admission) with subsequent multifocal osteomyelitis.

Cerebral palsy

The cerebral palsies are a heterogeneous group of static encephalopathies that have in common, a disorder of posture and movement. The motor disability is permanent and the clinical manifestations are variable. Cerebral palsy can be simply classified into:

Adverse prenatal and perinatal events that affect the brain account for the known causes of cerebral palsy, although most causes are unknown.

The cognitive ability of a child with cerebral palsy cannot be quickly determined. Time is required with these children to assess their physical and mental abilities. Many patients with cerebral palsy have no cognitive impairment at all and may use a form of verbal communication that requires an electronic aid and operator patience. It is often not necessary to change voice tone or level of language when addressing these children.

Maxillary protrusion and generalized anterior tooth spacing are common sequelae due to abnormal orofacial neuromuscular tone (Figure 13.7). Tongue thrust, dribbling, mouth breathing, and perioral sensitivity are also common clinical presentations. Dental caries and periodontal disease may be severe due to neglect and following surgery to reposition the major saliva gland ducts to reduce drooling.

Figure 13.7 Severe phenytoin gingival enlargement, candidosis and papillary hyperplasia in the palate of a child with cerebral palsy. The hypertonicity of the oral musculature has caused the protrusion of the anterior teeth and an orthopaedic compression of the maxilla.

Dental management

Reflex limb extension patterns may be triggered during dental visits if care is not taken. These contractions may occur during transfer of the patient from wheelchair to the dental chair. Discuss the transfer with the parent or caregivers before offering assistance. Use the hoist option for a safe transfer when available. This reflex may also be stimulated if the child’s head is loose or unsupported. Ensure that the child is stabilized in the chair with blankets and pillows or restrained with a belt or webbing. If a reflex pattern occurs where the limbs are in extension:

Some patients are best treated in their own motorized wheelchairs. Remember to lock the wheels, recline the chair and use adequate head support (Figure 13.8).

Figure 13.8 Motorized wheelchair lift, allowing the patient to remain in the chair during dental treatment.

Gag, cough, bite and swallowing reflexes may be impaired or abnormal in children with cerebral palsy. If the gag reflex is more exaggerated, treat the patient in a more upright position with the neck in slight flexion and the knees bent upwards, if possible. Mouth props may be used, however, for those patients with impaired swallowing, there is an increased risk of aspiration. Hand-held props and a floss ligature help to reduce this possibility. Rubber dam is especially useful in these cases as well. If the patient’s bite reflex to oral stimulation is still present, introduce instruments from the side rather than the front. To allow dental examination, apply gentle pressure with the forefinger on the anterior border of ascending ramus and in the retromolar triangle. This reduces the risk of a bitten finger. Alternatively in some cases, foam mouth props are available to assist in providing a safe oral examination in those patients with unpredictable behaviour who may unexpectedly bite down (Figure 13.9). Nitrous oxide sedation may help to reduce involuntary movements during dental treatment.

Figure 13.9 (A) A foam mouth-prop may also aid oral examination or tooth brushing. (B) It is very important to protect your fingers from being bitten, not least to protect against the risk of infection but also potential damage. By placing the index finger in the buccal sulcus and behind the last molar, the mouth can be opened and the operator’s fingers safe.

Hydrocephalus

Most cases of hydrocephalus result from obstruction to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow, either within the cerebral ventricles or in the subarachnoid space. As the ventricles enlarge due to the accumulation of CSF, intracranial pressure increases, resulting in serious neurological impairment if not decompressed. The postnatal causes of hydrocephalus are varied including bacterial infection, haemorrhage and neoplastic obstruction, but prenatal causes are often undiagnosable. Treatment by insertion of a shunt is usually appropriate in infants with severe hydrocephalus. Many children with hydrocephalus have other developmental deficits such as learning disabilities or paraplegia.

Children with hydrocephalus undergoing dental treatment may require antibiotic prophylaxis if they have shunts that directly empty into the major blood vessels (ventriculoatrial) to prevent septicaemia and shunt infection. It is generally considered that children with ventriculoperitoneal and spinoperitoneal shunts do not require prophylactic antibiotic cover, unless specified by the neurologist. In all instances it is wise to seek advice and manage the patient in consultation with the their attending physician.

Spina bifida

In this condition, there is a herniation (meningomyelocele) of the spinal cord, nerve roots and meninges through a wide deficiency in the laminae and spinous process of one or more vertebrae, usually at the sacral or lumbosacral levels. The exposed cord is dysplastic and almost always non-functional, often resulting in paraplegia. Early operative closure is performed where possible to prevent infection and subsequent orthopaedic and urological management are necessary. Rehabilitation is best provided by coordinated multidisciplinary clinics.

Children with spina bifida have a higher prevalence of latex allergy (gloves, rubber dam) compared with the general paediatric population. The use of vinyl gloves is recommended. Many children are confined to a wheelchair and spinal comfort should be optimized in a similar way as for children with cerebral palsy. Otherwise, routine dental management can be undertaken in the clinic setting.

Muscular dystrophies

Muscular dystrophy is a progressive, genetically determined, primary degenerative myopathy. The clinical features include increasing muscle weakness, poor muscle tone, abnormal body movements, skin changes and progressive joint and skeletal deformity. Duchenne muscular dystrophy and myotonic dystrophy are the two most common forms and current treatment is to slow the effects of disuse atrophy. Ambulation is usually not possible after 12 years of age.

Oral manifestations include craniofacial deformity with protrusive spaced anterior teeth due to poor orofacial tone and associated mouth breathing, tongue thrust and open bite. Poor plaque control, gingivitis and anterior tooth trauma are common oral findings. Dental management strategies are similar to those used in children with cerebral palsy, using head and body supports and mouth props. Do not try and stop your patient’s movements, instead work around them. Use check retractors in patients with loose or rigid oral musculature. Sedation and general anaesthesia are often necessary to manage children with muscular dystrophy due to their inability to tolerate routine procedures in the dental chair.

Sedation and general anaesthesia are often necessary to manage children with muscular dystrophy due to their inability to tolerate routine procedures in the dental chair. Anaesthetic techniques must be modified to minimize intra- and postoperative respiratory and cardiovascular depression and invasive monitoring, and access to intensive care may be warranted. Depolarizing muscle relaxants like succinylcholine should be avoided because of the risk of hyperkalaemia. This may result in the release of large amounts of potassium ions from the muscle cell into the bloodstream with subsequent, rapid increase in potassium concentration in the blood resulting in life-threatening cardiac rhythm disturbances. Malignant hyperthermia occurs relatively frequently in patients with muscular dystrophy in the presence of succinylcholine or inhalation anaesthetics. This is characterized by an extremely elevated metabolism within the muscle cell. As a result, the temperature of the entire body rises to life-threatening levels. It is of tremendous importance that this is promptly diagnosed and appropriate measures are implemented.

Vision impairment

In addition to the obvious barriers to care that present for a child with vision impairment: the inability to see the dentist, the environment and what treatment is being done, is extremely threatening. Again, communication is the key to trust and success in treatment.

• The reception staff should introduce themselves and offer to lead the patient to the surgery and determine the level of assistance your patient needs. If the patient attends with a guide dog in harness, it indicates the dog is working.

• It is vital to assess the degree of visual impairment. Allow the child to make full use of their tactile sense and their sense of smell when familiarizing them with the dental environment and dental procedures.

• Always announce your entry and departure from the room. Offer verbal and physical reassurance to the child once a rapport has been established, as they cannot see non-verbal gestures.

• Paint a picture in the mind of your patients by describing the treatment and the environment throughout the procedure. A startle reflex may occur if patients are not warned before different instruments are introduced into the mouth without warning.

• Many visually impaired people are photophobic. It is important to ask parents and children about light sensitivity. Safety glasses should preferably be tinted.

• All written information, including appointments and oral hygiene instructions, should be provided in large text or Braille.

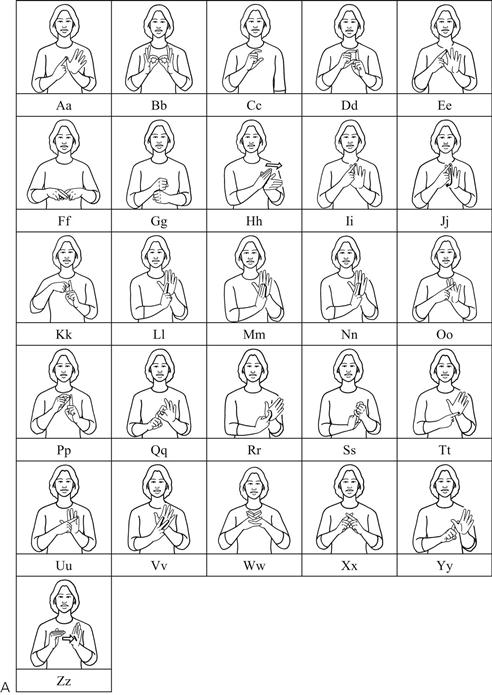

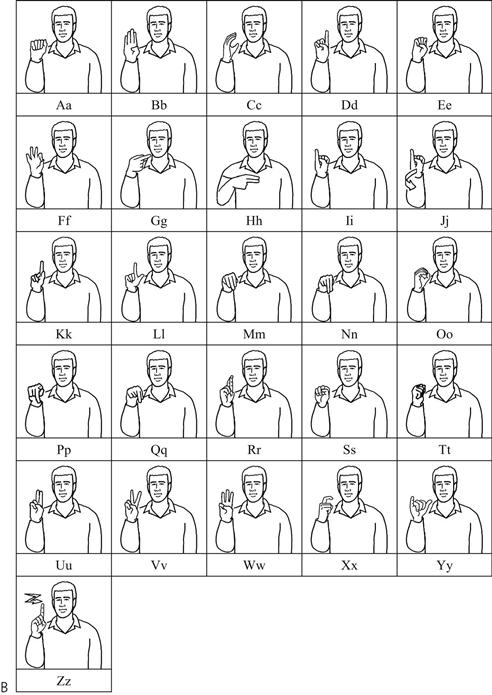

Hearing impairment

Children with hearing impairment present a unique challenge for dentists, as effective communication is the primary basis of successful child management. Hearing impairment may be sensorineural or conductive in origin, and range in degree of hearing loss from mild to profound. Recent advances such as the development of the cochlear implant, new surgical procedures and future stem cell therapy, have improved hearing outcomes significantly for many, but not all, hearing impaired children. It is useful to learn basic sign language or the appropriate manual finger-spelling alphabet (e.g. the two-handed alphabet in Britain, Australia and New Zealand; or the one-handed alphabet in the USA and Canada and, with some variation, many other countries) (see Figure 13.10). It should be noted that even within the English-speaking world, there are different sign languages which are mutually unintelligible (i.e. Auslan in Australia or American Sign Language in the USA and Canada). As with all behaviour management, it is essential to win the trust of the child, be cognizant of their special needs and understand the unique difficulties they have in communication.

• Investigate how the child communicates. If the child uses a sign language as their first or preferred language, use basic signs and finger-spelling if you have previously learned this or, preferably, use the services of a sign language interpreter.

• If the child is hearing-impaired and is able to use their residual hearing with the help of hearing aids or a cochlear implant and lip-reading, use speech. A common fault is to talk loudly rather than slowly. Face the child and speak clearly and slowly. Remove your face mask and eliminate or reduce any background sounds (e.g. radio, etc.) before speaking with the child.

• Make it easy for patients to maintain visual contact, because these children may be startled if they are touched without visual contact.

• Children with hearing difficulties may be very sensitive to vibration, so introduce high-speed and low-speed drills carefully.

• If a hearing aid is worn, the volume may need adjustment. Try to avoid blocking the ears and the hearing aid with the forearms when operating, as this will create feedback.

Oro-motor dysfunction in patients with developmental disabilities

Children with cerebral palsy, trisomy 21 and global developmental delay often present with poor oral functions including:

• Dysphagia – difficulty in swallowing.

• Dysphasia – difficulty in speaking.

• Sialorrhoea – difficulty in swallowing, resulting in drooling.

Drooling

Parents will often present with their primary concern being excessive drooling. The paediatric dentist has a significant role in the management of sialorrhoea. Causes of drooling can range from poor competency of the lip and orofacial musculature, malocclusion, dysphagia, to oral habits.

The options for the management of drooling are:

Pharmacological management

• Trihexyphenidyl hydrochloride (benzhexol hydrochloride; Artane).

• Scopolamine transdermal patches.

• Botulinum toxin A (Botox). It has a short duration of action (2–6 months) and necessitates the need for repeat general anaesthetics for some patients.

Side-effects of medications include:

Oro-motor function therapy

Oro-motor function therapy is carried out by multidisciplinary teams that may include speech pathologists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and dentists. The focus of oro-motor function therapy is to develop the oral motor skills required to manage saliva control. This multifaceted approach may include a number of elements such as:

• Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation.

• Oral screens and dental appliances designed to stimulate oral musculature.

Dental appliances

These are individually designed to produce the desired movement of the tongue, lips or jaw (Figure 13.11). Common goals include:

Further reading

1. Chew LC, King NM, O’Donnell D. Autism: the aetiology, management and implications for treatment modalities from the dental perspective. Dental Update. 2006;33:70–80.

2. Dougall A, Fiske J. Access to special care dentistry Part 4 Education. British Dental Journal. 2008;205:119–130.

3. Estrella MR, Boynton JR. General dentistry’s role in the care for children with special needs: a review. General Dentistry. 2010;58:222–229.

4. Goyette CH, Conners CK, Ulrich RF. Normative data on revised Conners Parent and Teacher Rating Scales. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:221–236.

5. Hussein I, Kershaw AE, Tahmassebi JF, et al. The management of drooling in children and patients with mental and physical disabilities. International Journal of Pediatric Dentistry. 1998;8:3–11.

6. Klein U, Nowak AJ. Autistic disorder: a review for the paediatric dentist. Pediatric Dentistry. 1998;20:312–317.

7. Lawton L. Providing dental care for special patients Tips for the general dentist. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2002;133:1666–1679.

8. Levine MD, Carey WB. Developmental-behavioral paediatrics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1983.

9. Monroy PG, da Fonseca MA. The use of botulinum toxin-a in the treatment of severe bruxism in a patient with autism: a case report. Special Care in Dentistry. 2006;26:37–39.

10. Moursi AM, Fernandez JB, Daronch M, et al. Nutrition and oral health considerations in children with special health care needs: implications for oral health care providers. Pediatric Dentistry. 2010;32:333–342.

11. Nunn J. Disability and oral care International Association for Disability and Oral Health and FDI. London: World Dental Press; 2000.

12. Pilebro C, Bäckman B. Teaching oral hygiene to children with autism. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 2005;15:1–9.

Websites

1. British Society for Disability and Oral Health. In: www.bsdh.org.uk/guidelines.html;.

2. Mun-H Center. In: www.mun-h-center.se;.