Speech, language and swallowing

Sarah Starr

Introduction

The ability to communicate effectively is vital to a person’s functioning in society. Speech and language acquisition is a developmental process occurring most dramatically in the first years of life but one that proceeds throughout a person’s lifetime. Difficulties may be encountered at any point during the language acquisition process. Children may experience problems acquiring the sounds of the language, learning how to combine words meaningfully or comprehending others’ questions and instructions. In all cases, a speech and language pathologist is the primary healthcare professional responsible for the identification and treatment of individuals with communication problems. Paediatric dentists should be aware of the symptoms and problems associated with communication impairment, particularly when it relates to orofacial or dentofacial anomalies. They should know how to refer children and their families to a speech pathologist.

Communication begins at birth and continues throughout a child’s life through adolescence and into adult life. A child’s communication development is influenced by many variables, including neurological status and motor development, oromotor status (anatomical and physiological), cognition, hearing, birth order, environment, communication modelling and experiences, as well as their personality.

This chapter will briefly describe some of the main communication disorders that can present with particular focus for paediatric dentists.

Communication disorders

There are six main areas to be considered when assessing a child’s communication:

Oral motor and feeding problems

Problems in this area constitute the earliest at which children are referred to a speech pathologist. Significant problems can result when an infant does not develop control of the oral mechanism sufficient for successful feeding. Early reflex development typically facilitates feeding behaviour, but neuromotor factors, prematurity, cleft lip and palate, long-term non-oral feeding and other reasons may interfere with a child’s development of the movement patterns essential for sucking, swallowing and feeding. Since these patterns form the scaffolding of movement for early speech sound development, children with a history of feeding difficulties may have subsequent difficulties in producing sounds for speech.

Reasons for referral

• Sucking, swallowing or chewing difficulties.

• Gagging, coughing or choking with feeds.

• Moist vocal quality during or after feeds.

• Persistent drooling (not coincident with teething).

• Presence of a craniofacial malformation.

• Parental report of feeding difficulty or refusal.

• Poor oral intake and associated poor weight gain in infants and young children.

Articulation

Articulation refers to the production of speech sounds by modification of the breath stream using the various valves along the vocal tract: lips, tongue, teeth and palate. Problems in these areas can vary from a fairly mild distortion of sounds such as a lisp, where the child’s speech is still easy to understand, through to a more severe speech production problem where all speech attempts are unintelligible or where the child makes very few speech attempts. Errors can be classified in the following ways:

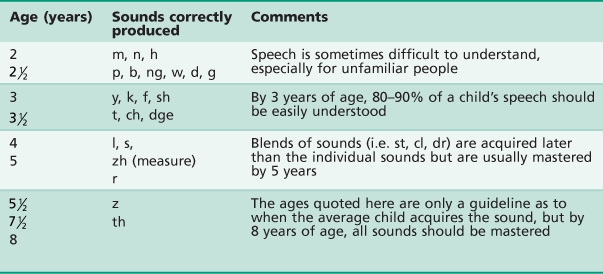

Children learn to produce sounds in a developmental sequence, with adult-like sound systems expected by 8 years of age (Table 16.1). For example, it is quite acceptable for a 2-year-old to mispronounce an ‘s’ sound, but it would be considered a problem if a similar error were made by a 7-year-old child.

Language

In contrast to the fairly straightforward examples listed above to illustrate speech sound learning, language development is much more complex. Skills emerge in two parallel levels.

Receptive language

This is the ability to understand language.

Expressive language

This refers to the ability to produce verbal and non-verbal communication in the form of words and sentences and may include speech and written language.

A child with a language disorder may present with difficulties in both comprehension and expression of language or in only one area of language learning. Language learning proceeds in a predictable order but there is more variability in the emergence of these skills than the acquisition of speech sounds. Vocabulary grows as does a child’s ability to progressively understand more complex language. Words are combined into phrases and eventually sentences, and comprehension becomes more adult-like over time. Eventually, language that is heard and said becomes the language of literacy, reading and writing. School success is highly correlated with language learning, especially in the early years.

Children may experience language learning problems at any stage of the acquisition process. There may be:

• Difficulties interpreting the meaning of words and gestures.

• Delays in the production of first words and phrases.

• A lack of understanding of questions and instructions.

• An inability to produce sentences that are grammatically correct.

A delay at any single stage may not necessarily constitute a longstanding problem, although it should be investigated further. Problems with language acquisition are the most subtle indicators of difficulties with childhood development and therefore, should never be ignored.

Voice

Voice is produced when the vocal cords in the larynx are vibrated. Changes in air flow and the shape of the vocal folds can affect loudness, pitch and voice quality. Once voice is produced, its tone (resonance) and quality is modified by the throat, oral and nasal cavities. A child with a voice problem may present with the following:

Abnormal voice quality

Rough, breathy or hoarse voice in the absence of upper respiratory tract infection.

Abnormal resonance

Hypernasality (excessive nasal tone usually due to problems closing the velopharyngeal port during speech) or hyponasality (lack of nasal resonance usually due to some type of nasopharyngeal obstruction).

Inappropriate loudness levels

Voice too soft to be heard or so loud that it is distracting from the message of the speaker.

Problems with pitch

Pitch too high or low for age or sex.

Voice problems may be caused by:

• Poor vocal use, e.g. excessive yelling or screaming (in some cases producing vocal nodules).

• Neurological problems (e.g. cerebral palsy).

• Vocal pathology such as polyps or cysts.

• Vocal irritants such as exposure to smoking, chemicals or aerosol sprays.

• Physical conditions including cleft palate, laryngectomy and hearing loss.

Fluency

Fluency refers to the smooth flow of speech. Where there are interruptions in the flow of speech, stuttering occurs. Many children experience brief periods of stuttering as they learn to speak in longer sentences and this early form of disfluency is not considered a disordered pattern, as it will usually pass. Early developmental disfluency is best resolved by reacting to the message the child is attempting to convey rather than the disfluency. When stuttering persists beyond the normal time period of approximately 3–6 months, and/or there is strong family history of stuttering or when it is becoming stressful for the child, referral to a speech pathologist is indicated.

A child or an adult with a stutter experiences involuntary repetition of words, prolongations of sounds in words and blocks where no sound is produced at all. Some speakers with a stutter will use words like ‘um’ to help them initiate speaking. Sometimes secondary features such as eye blinking and facial grimacing occur with the stutter.

Stutterers do not have more emotional or psychological problems when compared with the general population, nor is there evidence of decreased mental aptitude. Approximately 3% of the population stutter, with a predominance in males (3 : 1). The disorder usually has its onset in the early years of life and treatment is most successful in the preschool years. Hence, the importance of prompt and early referral.

Pragmatics

Pragmatics refers to how we communicate with others through our verbal and non-verbal language as well as our tone of voice, stress, pausing, pitch and loudness. Pragmatics relates to our social use of language, including how we initiate, engage and maintain others in a communication dialogue through our eye contact, body language, physical space, choice and use of words, conversational turn taking and responses to others.

Pragmatic skills allow us to develop friendships and effectively communicate our messages in a social, educational and workplace setting. They are crucial to effective communication and develop from birth throughout our adult life. Pragmatic skills develop as part of normal cognitive development and are influenced by environmental and cultural modelling. Disorders in pragmatic skills can be isolated or part of a language, developmental, psychological or specific condition (e.g. autism).

Structural anomalies and their relationship to speech production and eating and drinking

The speech language pathologist is actively involved in the evaluation of orofacial, pharyngeal and laryngeal structures and functioning important for speech production and deglutition. Evaluation techniques may be perceptual or instrumental (e.g. video-fluoroscopic X-ray studies of swallowing) and are often a combination of both, with input from other members of a multidisciplinary team. Results of diagnostic structural and/or functional testing direct which management strategies are available to the patient.

Speech sounds may be acoustically or visually distorted due to abnormal structure and/or function of the articulators (most commonly the lips, tongue, teeth and palate). There are three main ways in which speech sound production is influenced and these can coexist, thus differential diagnosis is important in decision-making for management.

1. Speech sounds may be omitted, substituted or added during early childhood, as mature speech patterns are mastered. For example, 3-year-old children often substitute alveolar sounds for velar sounds (cap → tap; go → do). Some children continue these substitutions for longer than expected and need speech therapy to learn mature speech patterns.

2. Speech sounds may be distorted due to underlying neurological impairment or oro-motor planning/coordination problems. Speech may be termed dysarthric (neurological) or dyspraxic (motor planning), depending on the aetiology and characteristics noted.

3. Structural problems may affect speech (and swallowing) in a number of ways. These are outlined below.

Dental anomalies

Malocclusion has the potential to greatly affect speech production although the ability of patients to compensate for abnormal dental relationships should never be underestimated. However, there is no definite proof that altering the position of a tooth may improve speech (Johnson & Sandy 1999).

Hypodontia/missing teeth causing interdental spacing

Chewing difficulties may result and a lateral or forward displacement of tongue during speech may occur, resulting in distortion of sounds. The presence or absence of teeth and the position of these teeth in the dental arch is thought to be more significant for speech production than the condition, size or texture of the teeth (Shprintzen & Bardach 1995). In general, lingual-alveolar sounds (e.g. /s/, /z/) followed by lingual-palatal sounds (‘j’, ‘sh’, ‘ch’) are most affected by spaces in the dental arch. The tongue tends to move forwards into the interdental space causing a central or lateral ‘lisp’. The speech sounds most resistant to changes in the dental arch are the velar consonants /k/ and /g/ (Bloomer 1971).

Class III malocclusion

A severe Class III malocclusion may be associated with distortion or interdentalization (‘lisping’) of sibilant and alveolar speech sounds (/s/, /z/, /t/, /d/, /n/, /l/) due to difficulty elevating the tongue tip to the alveolar ridge. The sound most likely to be affected is /s/. This is probably because production relies on precise placement of the tongue tip and blade in addition to sufficient space being available anterior to the tip in the anterior portion of the palate (Bloomer 1971). Forward tongue placement can also be associated with a tongue thrust swallow and more cumbersome oral preparation of food with poor lateral tongue transfers and imprecise tongue tip elevation during swallowing.

Class II malocclusion

A severe Class II malocclusion may interfere with lip closure during eating and drinking. Bilabial speech sounds (/p/, /b/, /m/) may be distorted or produced in a labiodental manner (with the upper incisors articulating with the lower lip). The speech sounds may be ‘visually’ distorted, that is they may look different but be acoustically acceptable (sound near normal).

Anterior open bite

An anterior open bite allows the tongue to move forward into the interdental space, causing interdentalization (‘lisping’) or distortion of speech sounds, particularly those which involve the tongue tip contacting the alveolar ridge (/t/, /d/, /n/, /l/) and palate (/s/, /z/).

Swallowing may also be different for children with an anterior open bite, compared with those with a normal occlusion. For example, genioglossus muscle activity is significantly higher in patients with anterior open bite than those without (Alexander & Sudha 1997). Difficulty biting with middle incisors is common when an anterior open bite is present with overfilling of the mouth, tearing of food or compensatory biting with more lateral teeth noted.

Maxillary collapse

This condition sometimes occurs after cleft palate surgery and leads to distortion of sounds requiring tongue and palatal contact (‘s’, ‘z’, ‘sh’, ‘ch’, ‘j’).

Speech and feeding problems are not always associated with these dental conditions. Each patient must be considered individually in light of their abilities to compensate for dental or occlusal anomaly. In cases where problems are identified, speech therapy is coordinated with dental and orthodontic management. Some children may not be able to improve their speech or feeding until their dental treatment is complete.

Lip anomalies

Cleft lip

Sometimes, tissue deficiency and excessive tightness or scarring of tissue affect speech. The speech sounds most likely to be affected are the bilabials (/p/, /b/, /m/). Problems with the facial nerve affecting speech have been reported in syndromes such as hemifacial microsomia and Moebius syndrome (Shprintzen & Bardach 1995).

Depending on the nature of the lip abnormality and range of lip movement, lip closure and protrusion during drinking (e.g. cup/straw drinking) or speech may be affected. Poor lip closure may relate to imprecise labial sounds (p, b, m) and poor lip protrusion associated with distortion of sounds such as ‘w’, ‘oo’, ‘er’.

Palatal anomalies

The soft palate and pharyngeal walls work simultaneously to close the nasopharynx during speech production and swallowing (i.e. velopharyngeal closure). This action prevents excessive airflow into the nasal cavity during speech, maintains negative intra-oral pressure during sucking and swallowing and prevents nasal regurgitation of food or fluid during the swallow. If there is a palatal abnormality, velopharyngeal closure cannot take place efficiently, and there is often associated poor sucking, slow feeding and possible escape of food and liquid into the nose. Speech is nasal and breathy, sounds are unclear and volume may be reduced.

Palatal anomalies may include:

• Cleft palate (with or without cleft lip).

• Submucous cleft palate, characterized by a bifid uvula, notching of the posterior margin of the hard palate, zona pellucida and abnormal insertion of the levator musculature into the free bony edge of the hard palate.

• Congenital palatal anomalies, including short palate, deep nasopharynx, uncoordinated or inefficient velopharyngeal movement.

• Acquired palatal abnormalities resulting from neurological damage, surgery or neoplasms.

• Neurological abnormalities influencing palatal movement (e.g. cerebral palsy, cranial nerve IX and X abnormalities, muscular dystrophy).

Children with palatal anomalies are best referred to a specialist cleft palate clinic where they can receive coordinated multidisciplinary assessment and management (see Chapter 12).

Lingual anomalies

Abnormalities of the tongue may affect the precision, range and speed of tongue movement, resulting in speech or feeding difficulties. The most common problem is ankyloglossia or tongue tie.

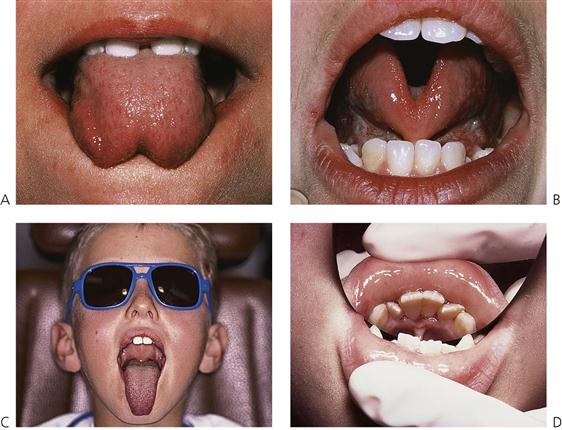

Ankyloglossia (Figure 16.1)

Tongue tie may occur with varying degrees of severity, which does not always correlate with severity of functional impairment. Some children have no problems with eating/drinking or speech and others do. Some of the possible are:

• Feeding difficulties such as difficulty sucking in infancy, poor tongue movement and chewing due to restricted tongue movement laterally and persistent messy eating (due to the child being unable to clear food from the buccal cavities and the lips).

• Substitution and distortion of tongue tip (alveolar) sounds /l/, /t/, /d/, /n/, /s/, /z/ caused by restricted elevation of the tongue tip.

• Slower than normal speech rate or reduced speech intelligibility in conversational speech.

• Reduced speech precision during shouting. (Shouting requires the mouth to open more widely and thereby may result in the tongue tie having a more negative effect on speech precision.)

• Difficulty breast-feeding in infancy and persistent messy eating in later childhood (due to the child being unable to clear food from the buccal cavities and the lips).

If a child’s speech or feeding appears to be affected by tongue tie, an assessment by a speech pathologist and a paediatric dentist is useful to determine whether lingual frenectomy is required.

Figure 16.1 Ankyloglossia. (A,B) Notice the tethering of the frenum to the anterior tip of the tongue restricting elevation and protrusion. It is important to assess the position of the frenum into the body of the tongue as well as any attachment into the gingival margin that may cause periodontal complications. (C) Extent of protrusion after lingual frenectomy. (D) Another indication for frenectomy is where the attachment inserts into the free gingival margin, causing potential periodontal problems.

Macroglossia

An abnormally large tongue may be associated with syndromes such as Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Children with macroglossia may have difficulty correctly articulation dento–lingual sounds (e.g. ‘th’), lingual–alveolar sounds /t/, /d/, /n/, /l/ and palatal–lingual sounds (e.g. ‘ch’, ‘j’, ‘sh’) In severe cases, the blade of the tongue may contact the upper lip affecting vowels and glides (e.g. /r/ and /w/).

Microglossia

An abnormally small tongue may be associated with syndromes such as hypoglossia-hypodactyly. In these cases, the tongue tip may not contact the teeth, palate or alveolus sufficiently for precise consonant production. Compensatory articulation of sounds may need to be developed.

Maxillofacial surgery and its relation to speech production

When orthognathic surgery is being considered, a consultation with a speech pathologist should be made to determine the possible consequences of the procedure on speech production.

Maxillary advancement procedures

When the maxilla is advanced anteriorly, the hard palate and soft palate are also displaced forwards, increasing the distance that the soft palate must move to achieve velopharyngeal closure. Most patients seem able to compensate for this alteration in nasopharyngeal relationships and their speech and swallowing are not affected. Some patients, however, are ‘at risk’ for deterioration in speech and swallowing characteristics (e.g. those with a repaired cleft palate). Forward displacement of the palatal structures may result in velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) and hypernasal speech production. Forward placement of the maxilla also means that the tongue contact on the palate may be altered for some sounds. Therefore, tongue placement and sound production may be improved in cases with severe Class III malocclusion.

Given the potential impact of surgical interventions on velopharyngeal function, the careful timing and selection of surgical techniques is recommended (Jacques et al 1997). Post-surgical speech review and possible speech therapy may also be warranted.

Referral to a speech pathologist

When the presence of a communication or feeding problem is suspected, referral should be made as soon as possible.

Dentists should refer any child who experiences the difficulties outlined below.

Language

• Is not understanding simple instructions and questions by 18 months.

• Is not using single words by 18 months.

• Is not combining two words by 2 years (i.e. ‘more drink’).

• Has difficulty following instructions or answering questions.

• Gives inappropriate answers or frequently ignores language spoken to them.

• Is constructing sentences that are incorrect or immature by 3–4 years (i.e. ‘me go to him house’).

Pragmatics

Referral procedures

It will be necessary to locate the most appropriate service to meet your patient’s needs. Most often, access to a speech pathologist through a local community health centre or hospital will be all that is required. Some patients may require a more specialized service such as a developmental disability service, cleft palate clinic, feeding specialist or feeding clinic. Some patients may prefer the services of a private practitioner.

Referral is most efficient when the dentist provides a written referral outlining the areas of concern. Following an assessment, a treatment plan will be devised according to the individual needs of the patient. Treatment can be provided in individual or group sessions and it may extend over a period of time, depending on the nature and severity of the condition. Most speech, language and feeding problems are best treated with parental participation. Preschool or school-based programmes are important for older children.

Further reading

1. Alexander S, Sudha P. Genioglossus muscle electrical activity and associated arch dimensional changes in simple tongue thrust swallow pattern. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 1997;21:213–222.

2. Bloomer JH. Speech defects associated with dental malocclusions and related abnormalities. In: Travis LE, ed. Handbook of speech pathology and audiology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1971.

3. Jacques B, Herzog G, Muller A, et al. Indications for combined orthodontic and surgical (orthognathic) treatments of dentofacial deformities in cleft lip and cleft palate patients and their impact on velopharyngeal function. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. 1997;49:181–193.

4. Johnson NC, Sandy JR. Tooth position and speech – is there a relationship? Angle Orthodontist. 1999;69:306–310.

5. Shprintzen RJ, Bardach J. Cleft palate speech management: a multidisciplinary approach. St Louis: Mosby; 1995.