Respiratory system

Background

Diseases of the respiratory tract are amongst the most common reasons for consulting a GP. The average GP sees approximately 700 to 1000 patients each year with respiratory disease. Although respiratory disease can cause significant morbidity and mortality, the vast majority of conditions are minor and self-limiting.

General overview of the anatomy of the respiratory tract

The basic requirement for all living cells to function and survive is a continuous supply of oxygen. However, a by-product of cell activity is carbon dioxide, which, if not removed, poisons and kills the cells of the body. The principal function of the respiratory system is therefore the exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen between blood and atmospheric air. This exchange takes place in the lungs, where pulmonary capillaries are in intimate contact with the linings of the lung’s terminal air spaces: the alveoli. All other structures associated with the respiratory tract serve to facilitate this gaseous exchange.

The respiratory tract is divided arbitrarily into the upper and lower respiratory tract. In addition to these structures, the respiratory system also includes the oral cavity, rib cage and diaphragm.

Upper respiratory tract

The upper respiratory tract comprises those structures located outside the thorax: the nasal cavity, pharynx and larynx.

Nasal cavity

The internal portion of the nose is classed as the nasal cavity. The nasal cavity is connected to the pharynx through two openings called the internal nares. Besides receiving olfactory stimuli (smell), the nasal cavity plays an important part in respiration because it filters out large dust particles and warms and moistens incoming air.

Pharynx

The pharynx is divided into three sections:

• nasopharynx, which exchanges air with the nasal cavity and moves particulate matter toward the mouth

• oropharynx and laryngopharynx, which serve as a common passageway for air and food

• laryngopharynx, which connects with the oesophagus and the larynx and, like the oropharynx, serves as a common pathway for the respiratory and digestive systems.

Lower respiratory tract

The lower respiratory tract is located almost entirely within the thorax and comprises the trachea, bronchial tree and lungs.

Trachea and bronchi

The trachea connects the larynx with the bronchi. The bronchi divide and subdivide into bronchioles and these in turn divide to form terminal bronchioles, which give rise to alveoli where gaseous exchange takes place. The epithelial lining of the bronchial tree acts as a defence mechanism known as the mucociliary escalator. Cilia on the surface of cells beat upwards in organised waves of contraction thus expelling foreign bodies.

Lungs

The lungs are cone shaped and lie in the thoracic cavity. Enclosing and protecting the lungs are the pleural membranes; the inner membrane covers the lungs and the outer membrane is attached to the thoracic cavity. Between the membranes is the pleural cavity, which contains fluid and prevents friction between the membranes during breathing.

History taking and physical exam

Cough, cold, sore throat and rhinitis often coexist and an accurate history is therefore essential to differentially diagnose a patient who presents with symptoms of respiratory disease. A number of similar questions must be asked for each symptom, although symptom-specific questions are also needed (these are discussed under each heading, below). Currently, examination of the respiratory tract is outside the remit of the community pharmacist, unless they have additional qualifications (e.g. independent prescriber status).

Cough

The main function of coughing is airway clearance. Excess secretions and foreign bodies are cleared from the lungs by a combination of coughing and the mucociliary escalator. (the upward beating of the finger-like cilia in the bronchi that move mucus and entrapped foreign bodies to be expectorated or swallowed). Cough is the most common respiratory symptom and one of the few ways by which abnormalities of the respiratory tract manifest themselves. Cough can be very debilitating to the patients’ well-being and be disruptive to family, friends and work colleagues.

Coughs can be described as either productive (chesty) or non-productive (dry, tight, tickly). However, many patients will say that they are not producing sputum, although they go on to say that they ‘can feel it on their chest’. In these cases the cough is probably productive in nature and should be treated as such.

Coughs are either classed as acute or chronic in nature. The British Thoracic Society Guidelines (2006) recommend that:

The guidelines acknowledge that a ‘grey area’ exists for those coughs lasting between 3 and 8 weeks as it is difficult to define their aetiological basis because all chronic coughs will have started as an acute cough. For community pharmacy practice this ‘grey area’ is rather academic, as any cough lasting longer than the accepted definition of acute should be referred to a medical practitioner for further investigation.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Statistics from general medical practice show that respiratory illness accounts for more patient visits than any other disease category. Acute cough is usually caused by a viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and constitutes 20% of consultations. This translates to 12 million GP visits per year and represents the largest single cause of primary care consultation. In community pharmacy the figures are even higher with at least 24 million visits per year (or 2000 visits per pharmacy per year).

Schoolchildren experience the greatest number of coughs, with an estimated 7–10 episodes per year (as compared to adults with 2–5 episodes per year). Acute viral URTIs exhibit seasonality, with higher incidence seen in the winter months.

Aetiology

A five-part cough reflex is responsible for cough production. Receptors located mainly in the pharynx, larynx, trachea and bifurcations of the large bronchi are stimulated via mechanical, irritant or thermal mechanisms. Neural impulses are then carried along afferent pathways of the vagal and superior laryngeal nerves, which terminate at the cough centre in the medulla. Efferent fibres of the vagus and spinal nerves carry neural activity to the muscles of the diaphragm, chest wall and abdomen. These muscles contract, followed by the sudden opening of the glottis that creates the cough.

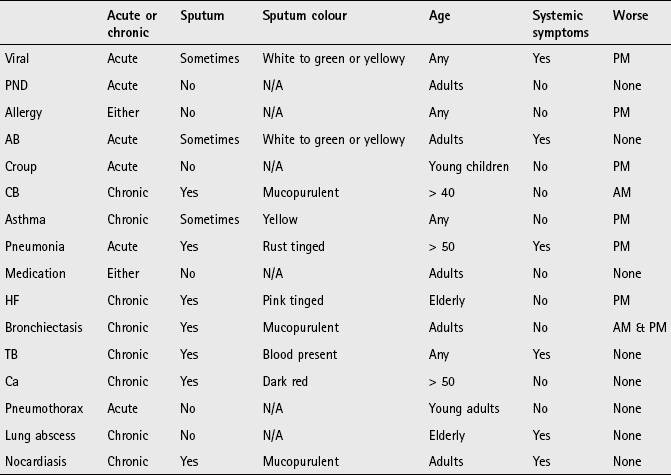

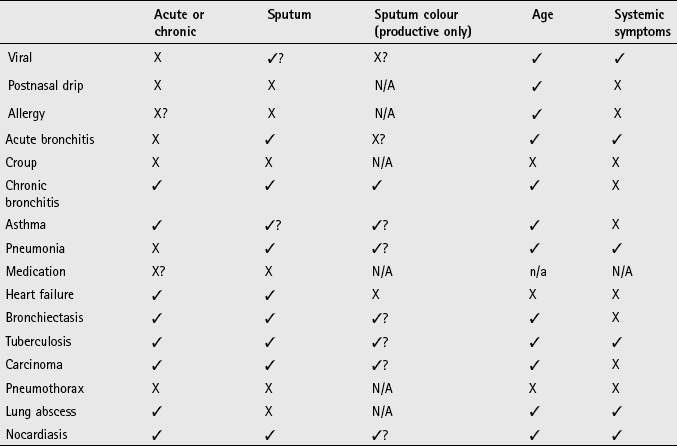

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

The most likely cause of acute cough in primary care for all ages is viral URTI. Recurrent viral bronchitis is most prevalent in preschool and young school-aged children and is the most common cause of persistent cough in children of all ages. Table 1.1 highlights those conditions that can be encountered by community pharmacists and their relative incidence.

Table 1.1

Causes of cough and their relative incidence in community pharmacy

| Incidence | Cause |

| Most Likely | Viral infection |

| Likely | Upper airways cough syndrome (formerly known as postnasal drip and includes allergies), acute bronchitis |

| Unlikely | Croup, chronic bronchitis, asthma, pneumonia, ACE inhibitor induced |

| Very unlikely | Heart failure, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, cancer, pneumothorax, lung abscess, nocardiasis, GORD |

As viral infection is the most likely cause of cough encountered by pharmacists it is logical to ask questions that help to confirm or refute this assumption. However, it is important to differentiate other causes of cough from viral causes and also refer those cases of cough that might have more serious pathology. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 1.2).

![]() Table 1.2

Table 1.2

Specific questions to ask the patient: Cough

| Question | Relevance |

| Sputum colour | Mucoid (clear and white) is normally of little consequence and suggests that no infection is present Yellow, green or brown sputum normally indicates infection. Mucopurulent sputum is generally caused by a viral infection and does not require automatic referral Haemoptysis can either be rust coloured (pneumonia), pink tinged (left ventricular failure) or dark red (carcinoma). Occasionally, patients can produce sputum with bright red blood as one-off events. This is due to the force of coughing causing a blood vessel to rupture. This is non-serious and does not require automatic referral |

| Nature of sputum | Thin and frothy suggests left ventricular failure Thick, mucoid to yellow can suggest asthma Offensive foul-smelling sputum suggests either bronchiectasis or lung abscess |

| Onset of cough | A cough that is worse in the morning may suggest upper airways cough syndrome, bronchiectasis or chronic bronchitis |

| Duration of cough | URTI cough can linger for more than 3 weeks and is termed ‘postviral cough’. However, coughs lasting longer than 3 weeks should be viewed with caution as the longer the cough is present the more likely serious pathology is responsible; for example, the most likely diagnoses of cough are as follows: at 3 days duration will be a URTI; at 3 weeks duration will be acute or chronic bronchitis; and at 3 months duration conditions such as chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis and carcinoma become more likely |

| Periodicity | Adult patients with recurrent cough might have chronic bronchitis, especially if they smoke Care should be exercised in children who present with recurrent cough and have a family history of eczema, asthma or hay fever. This might suggest asthma and referral would be required for further investigation |

| Age of the patient | Children will most likely be suffering from a URTI but asthma and croup should be considered With increasing age conditions such as bronchitis, pneumonia and carcinoma become more prevalent |

| Smoking history | Patients who smoke are more prone to chronic and recurrent cough. Over time this might develop in to chronic bronchitis and COPD |

Clinical features of acute viral cough

Viral coughs typically present with sudden onset and associated fever. Sputum production is minimal and symptoms are often worse in the evening. Associated cold symptoms are also often present; these usually last between 7 and 10 days. Duration of longer than 14 days might suggest ‘post viral cough’ or possibly indicate a bacterial secondary infection but this is clinically difficult to establish without sputum samples being analysed.

Conditions to eliminate

Upper airways cough syndrome (previously referred to as postnasal drip): Postnasal drip has recently (2006) been broadened to include a number of rhinosinus conditions related to cough. The umbrella term of upper airways cough syndrome (UACS) is being adopted.

UACS is characterised by a sinus or nasal discharge that flows behind the nose and into the throat. Patients should be asked if they are swallowing mucus or notice that they are clearing their throat more than usual, as these features are commonly seen in patients with UACS. Allergies are one cause of UACS. Coughs caused by allergies are often non-productive and worse at night. However, there are usually other associated symptoms, such as sneezing, nasal discharge/blockage, conjunctivitis and itching oral cavity. Cough of allergic origin might show seasonal variation, for example hay fever. Other causes include vasomotor rhinitis (caused by odours and changes in temperature/humidity) and post-infectious UACS after an URTI. If UACS is present, it is better to direct treatment at the cause of UACS (e.g. antihistamines or decongestants) rather than just treat the cough.

Acute bronchitis: Most cases are seen in autumn or winter and symptoms are similar to viral URTI but patients also tend to exhibit dyspnoea and wheeze. The cough usually lasts for 7–10 days but can persist for three weeks. The cause is normally viral, but sometimes bacterial. Symptoms will resolve without antibiotic treatment, regardless of the cause.

Unlikely causes

Laryngotracheobronchitis (croup): Symptoms are triggered by a recent viral infection, with parainfluenza virus accounting for 75% of cases, although other viral pathogens implicated include the rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus. It affects infants aged between 3 months and 6 years old and affects 2 to 6% of children. The incidence is highest between 1 and 2 years of age and occurs in boys more than girls; it is more common in autumn and winter months. It often follows on from an URTI and occurs in the late evening and night. The cough can be severe and violent and described as having a barking (seal-like) quality. In between coughing episodes the child may be breathless and struggle to breathe properly. Typically, symptoms improve during the day and often recur again the following night, with the majority of children seeing symptoms resolve in 48 hours. Warm moist air as a treatment for croup has been used since the 19th century. This is either done by moving the child to a bathroom and running a hot bath or shower or by boiling a kettle in the room. However, UK guidelines (Prodigy, 2011) do not advocate humidification as there is no evidence to support its use.

Croup management is based on an assessment of severity. Advice by pharmacists should be that if symptoms persist beyond 48 hours or the child exhibits any symptoms of stridor then medical intervention is required. Standard treatment for those children with stridor would be oral or intra-muscular dexamethasone or nebulised budesonide.

Chronic bronchitis: Chronic bronchitis (CB), along with emphysema, is characterised by the destruction of lung tissue and collectively known as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) The prevalence of COPD in the UK is uncertain. However, figures from the Health and Safety Executive (2010) estimate that over a million individuals currently have a diagnosis of COPD, and accounts for 25 000 deaths each year.

Patients with CB often present with a long-standing history of recurrent acute bronchitis in which episodes become increasingly severe and persist for increasing duration until the cough becomes continual. CB has been defined as coughing up sputum on most days for three or more consecutive months over the previous 2 years. CB is caused by chronic irritation of the airways by inhaled substances, especially tobacco smoke. A history of smoking is the single most important factor in the aetiology of CB. In non-smokers the likely cause of CB is UACS, asthma or gastro-oesophageal reflux. One study has shown that 99% of non-smokers with CB and a normal chest X-ray suffered from one of these three conditions.

CB starts with a non-productive cough that later becomes a mucopurulent productive cough. The patient should be questioned about smoking habit. If the patient is a smoker the cough will usually be worse in the morning. Secondary infections contribute to acute exacerbations seen in CB. It typically occurs in patients over the age of 40 and is more common in men. Pharmacists have an important role to play in identifying smokers with CB as this provides an excellent opportunity for health promotion advice and assessing the patient’s willingness to stop smoking.

Asthma: The exact prevalence of asthma is unknown due to differing terminologies and definitions plus difficulties in correct diagnosis, especially in children, and co-morbidity with COPD in the elderly. Best estimate of asthma prevalence in adults is approximately 4%, but it may be up to 10%. In children the figures are higher (10–15%) because a proportion of children will ‘grow out’ of it and be symptom free by adulthood.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory condition of the airways characterised by coughing, wheeze, chest tightness and shortness of breath. Classically these symptoms tend to be variable, intermittent, worse at night and provoked by triggers. In addition, possible associated features are family or personal history of atopy and worsening symptoms after taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or beta-blockers.

In the context of presentations to a community pharmacist, asthma can present as a non-productive cough, especially in young children where the cough is often worst at night. In these cases pay particular attention to other possible symptoms such as chest tightness, wheeze and difficulty in breathing, which may be frequent and recurrent and occur even when the child does not have a cold.

Pneumonia (community acquired): Bacterial infection is usually responsible for pneumonia and most commonly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (80% of cases), although other pathogens are also responsible, e.g. Chlamydia and Mycoplasma. Initially, the cough is non-productive and painful (first 24 to 48 hours), but rapidly becomes productive, with sputum being stained red. The intensity of the redness varies depending on the causative organism. The cough tends to be worst at night. The patient will be unwell, with a high fever, malaise, headache, breathlessness, and experience pleuritic pain (inflammation of pleural membranes, manifested as pain to the sides) that worsens on inspiration. Urgent referral to the doctor is required as antibiotics should be started as soon as possible.

Medicine-induced cough or wheeze: A number of medicines may cause bronchoconstriction, which presents as cough or wheeze. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are most commonly associated with cough. Incidence might be as high as 16%; it is not dose related and time to onset is variable, ranging from a few hours to more than 1 year after the start of treatment. Cough invariably ceases after withdrawal of the ACE inhibitor but takes 3 to 4 weeks to resolve. Other medicines that are associated with cough or wheeze are NSAIDs and beta-blockers. If an adverse drug reaction (ADR) is suspected then the pharmacist should discuss alternative medication with the prescriber, for example the incidence of cough with angiotension II receptor blockers is half that of ACE Inhibitors.

Very unlikely causes

Cough is a symptom of many other conditions, although the majority will be rarely encountered in community pharmacy. However, it is important to be aware of these rare causes of cough to ensure that appropriate referrals are made.

Heart failure: Heart failure is a condition of the elderly. The prevalence of heart failure rises with increasing age; 3 to 5% of people aged over 65 are affected and this increases to approximately 10% of patients aged 80 and over. Heart failure is characterised by insidious progression and diagnosing early mild heart failure is extremely difficult because symptoms are not pronounced. Often, the first symptoms patients experience are shortness of breath, orthopnoea and dyspnoea at night. As the condition progresses from mild/moderate to severe heart failure patients might complain of a productive, frothy cough, which may have pink-tinged sputum.

Bronchiectasis: Bronchiectasis is caused by irreversible dilation of the bronchi. Characteristically, the patient has a chronic cough of very long duration, which produces copious amounts of mucopurulent sputum (green-yellow in colour) that is usually foul smelling. The cough tends to be worse in the morning and evening. In long-standing cases the sputum is said to display characteristic layering with the top being frothy, the middle clear and the bottom dense with purulent particles.

Tuberculosis: Tuberculosis (TB) is a bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and is transmitted primarily by inhalation. After many decades of decline, the number of new TB cases occurring in industrialised countries is now starting to increase. In 2009, UK figures showed that over 9000 cases were notified – an increase of 4% on the previous year and the highest number for nearly 30 years. The incidence is higher in inner city areas (especially London and the West Midlands), among the elderly and immigrants from developing countries. TB is characterised by its slow onset and initial mild symptoms. The cough is chronic in nature and sputum production can vary from mild to severe with associated haemoptysis. Other symptoms of the condition are malaise, fever, night sweats and weight loss. However, not all patients will experience all symptoms. A patient with a productive cough for more than 3 weeks and exhibiting one or more of the associated symptoms should be referred for further investigation, especially if they fall into one of the groups listed above. Chest X-rays and sputum smear tests can be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Carcinoma of the lung: A number of studies have shown that between 20 and 90% of patients will develop a cough at some point during the progression of carcinoma of the lung. The possibility of carcinoma increases in long-term cigarette smokers who have had a cough for a number of months or who develop a marked change in the character of their cough. The cough produces small amounts of sputum that might be blood streaked. Other symptoms that can be associated with the cough are dyspnoea, weight loss and fatigue.

Lung abscess: A typical presentation is of a non-productive cough with pleuritic pain and dyspnoea. It is more common in the elderly. Signs of infection such as malaise and fever can also be present. Later the cough produces large amounts of purulent and often foul-smelling sputum.

Spontaneous pneumothorax (collapsed lung): Rupture of the bullae (the small air or fluid filled sacs in the lung) can cause spontaneous pneumothorax but normally there is no underlying cause. It affects approximately 1 in 10 000 people, usually tall, thin men between 20 and 40 years old. Cigarette smoking and a family history of pneumothorax are contributing risk factors. This can be a life-threatening disorder causing a non-productive cough and severe respiratory distress. The patient experiences sudden sharp unilateral chest pain that worsens on inspiration. The symptoms often begin suddenly, and can occur during rest or sleep.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) does not usually present with cough but patients with this condition might cough when recumbent (lying down). The patient might show symptoms of reflux or heartburn. Patients with GORD have increased cough reflex sensitivity and respond well to proton pump inhibitors. It should always be considered in all cases of unexplained cough.

Nocardiasis: Nocardiasis is an extremely rare bacterial infection caused by Nocardia asteroides; it is transmitted primarily by inhalation. It is very unlikely a pharmacist will ever encounter this condition and is included in this text for the sake of completeness. It has a higher incidence in the elderly population, especially men. The sputum is purulent, thick and possibly blood tinged. Fever is prominent and night sweats, pleurisy, weight loss and fatigue might also be present.

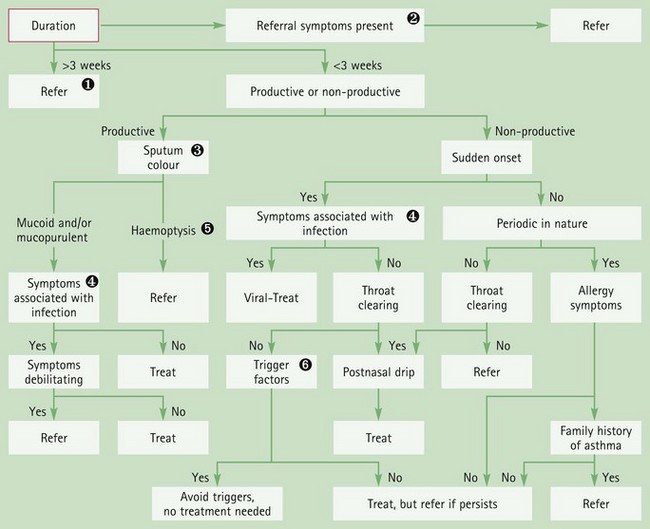

Figure 1.1 will aid the differentiation between serious and non-serious conditions of cough in adults.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Cough is often trivialised by practitioners but coughing can impair quality of life and cause anxiety to parents of children with cough. Patients who exercise self-care will be confronted with a plethora of over-the-counter (OTC) medication and many will find the choice overwhelming. The pharmacist must ensure that the most appropriate medication is selected for the patient, but this must be done on an evidence based approach.

All the active ingredients to treat cough were brought to the market many years ago when clinical trials suffered from flaws in study design compared to today’s standards, thus clinical efficacy is therefore difficult to establish.

Expectorants

A number of active ingredients have been formulated to help expectoration, including guaifenesin, ammonium salts, ipecacuanha, creosote and squill. The majority of products marketed in the UK for productive cough contain guaifenesin, although products containing squill (e.g. Buttercup Syrup) are available. The clinical evidence available for any active ingredient is limited. Older ingredients such as ammonium salts, ipecacuanha and squill were traditionally used to induce vomiting as it was believed that at subemetic doses they would cause gastric irritation, triggering reflex expectoration. This has never been proven and belongs in the annals of folklore. Guaifenesin is thought to stimulate secretion of respiratory tract fluid, increasing sputum volume and decreasing viscosity so assisting in removal of sputum. Guaifenesin is the only active ingredient that has any evidence of effectiveness. Two studies identified by Smith, Schroeder & Fahey (Cochrane Review 2008) found conflicting results for guaifenesin as an expectorant. In the largest study (n = 239) participants stated guaifenesin significantly reduced cough frequency and intensity compared to placebo. In the smaller trial (n = 65) guaifenesin was stated to have an antitussive not expectorant effect.

Summary

Based on studies, guaifenesin is the only expectorant with any evidence of effectiveness. However, trial results are not convincing and guaifenesin is probably little or no better than placebo. Given its proven safety record, absence of drug interactions, placebo properties and the public’s desire to treat productive coughs with a home remedy it would seem reasonable to supply OTC cough medicines containing guaifenesin.

Cough suppressants (antitussives)

Cough suppressants act directly on the cough centre to depress the cough reflex. Their effectiveness has been investigated in patients with acute and chronic cough as well as citric-acid-induced cough. Although trials on healthy volunteers – in whom coughing was induced by citric acid – allowed reproducible conditions to assess the activity of antitussives, they are of little value because they do not represent physiological cough. Of greatest interest to OTC medication are trials investigating acute cough, because patients suffering from chronic cough should be referred to the GP.

Codeine

Codeine is generally accepted as a standard or benchmark antitussive against which all others are judged. A review by Eddy et al (1970) showed codeine to be an effective antitussive in animal models, and cough-induced studies in humans have also shown codeine to be effective. However, these findings appear to be less reproducible in acute and pathological chronic cough. More recent studies have failed to demonstrate a significant clinical effect of codeine compared with placebo in patients suffering with acute cough. Greater voluntary control of the cough reflex by patients has been suggested for the apparent lack of effect codeine has on acute cough.

Pholcodine

Pholcodine, like codeine, has been subject to limited clinical trials, with the majority being either animal models or citric-acid-induced cough studies in man. These studies have shown pholcodine to have antitussive activity. A review by Findlay (1988) concluded that, on balance, pholcodine appears to possess antitussive activity but advocates the need for better, well-controlled studies.

Dextromethorphan

Trial data for dextromethorphan, like that for codeine and pholcodine, are limited. It has been shown to be effective in citric-acid-induced cough and chronic cough but studies assessing the efficacy of dextromethorphan in acute cough have shown it to be no better than placebo. It appears to have limited abuse potential and fewer side effects than codeine.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines have been included in cough remedies for decades. Their mechanism of action is thought to be through the anticholinergic-like drying action on the mucous membranes and not via histamine. There are numerous clinical trials involving antihistamines for the relief of cough and cold symptoms, most notably with diphenhydramine.

Citric-acid-induced cough studies have demonstrated significant antitussive activity compared to placebo and results from chronic cough trials support an antitussive activity for diphenhydramine. However, trials that showed a significant reduction in cough frequency suffered from having small patient numbers, thus limiting their usefulness. Additionally, poor methodological design of trials investigating the antitussive activity of diphenhydramine in acute cough makes assessment of its effectiveness difficult. A recent review concluded ‘Presumptions about efficacy of diphenhydramine against cough in humans are not unequivocally substantiated in literature’ (Bjornsdottir et al 2007). Less-sedating antihistamines, have also not been shown to have any benefit in treating coughs compared to placebo (Smith et al 2008).

Demulcents

Demulcents, such as simple linctus, are pharmacologically inert and are used on the theoretical basis that they reduce irritation by coating the pharynx and so prevent coughing. There is no evidence for their efficacy and they are used mainly for their placebo effect.

Combination cough mixtures

Many of the over-the-counter cough preparations are combinations of agents. Some of these include ingredients targeting other aspects of a common cold such as decongestants. It should be noted that some combination products contain sub-therapeutic doses of the active ingredients, while a few contain illogical combinations such as cough suppressants with an expectorant, or an antihistamine with an expectorant. If possible, these should be avoided.

Summary

Antitussives have been traditionally evaluated for efficacy in animal studies or cough-induced models on healthy volunteers. This presents serious problems in assessing their effectiveness because support for their antitussive activity does not come from patients with acute cough associated with URTI. Furthermore, there appear to be no comparative studies of sound study design to allow judgements to be made on their comparable efficacy. Compounding these problems is the self-limiting nature of acute cough, which further hinders differentiation between clinical efficacy and normal symptom resolution.

Antitussives therefore have a limited role in the treatment of acute non-productive cough. Patients should be encouraged to drink more fluid and told that their symptoms will resolve in time on their own. If medication is recommended then any active ingredient could be selected; side effect profile and abuse tendency rather than clinical efficacy will drive choice. On this basis, pholcodine and dextromethorphan would be first-line therapy and codeine, because of its greater side effect profile and tendency to be abused, should be reserved for second-line treatment. Antihistamines should not be used routinely, unless night-time sedation is perceived as beneficial to aid sleep.

Cough medication for children

Very few well-designed studies have been conducted in children. A review published in the Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin (Anonymous 1999) identified just five trials of sound methodological design. However, of these five trials, one study used illogical drug combinations (expectorant combined with suppressant) and a further three studies used combination products not available on the UK market.

In 2008 a Cochrane review examining the treatment of acute cough in both adults and children concluded there was no good evidence to support the effectiveness of cough medicines in acute cough (Smith et al 2008). In addition, there has been growing evidence of the potential harm that these agents can pose to young children, either due to adverse effects, or from accidental inappropriate dosing (Isbister et al 2010; Vassilev et al 2010). Based on the lack of efficacy and potential harm, the MHRA/CHM (in 2008 and 2009 respectively) recommended that cough and cold mixtures should not be used in children under 6 years of age, and should only be used in children aged 6 to 12 on the advice of a pharmacist or doctor and treatment limited to 5 days or less.

Furthermore, in October 2010, the MHRA announced that the risks associated with OTC oral liquid cough medicines containing codeine outweigh the benefits in children and young people under 18 years and therefore should no longer be used.

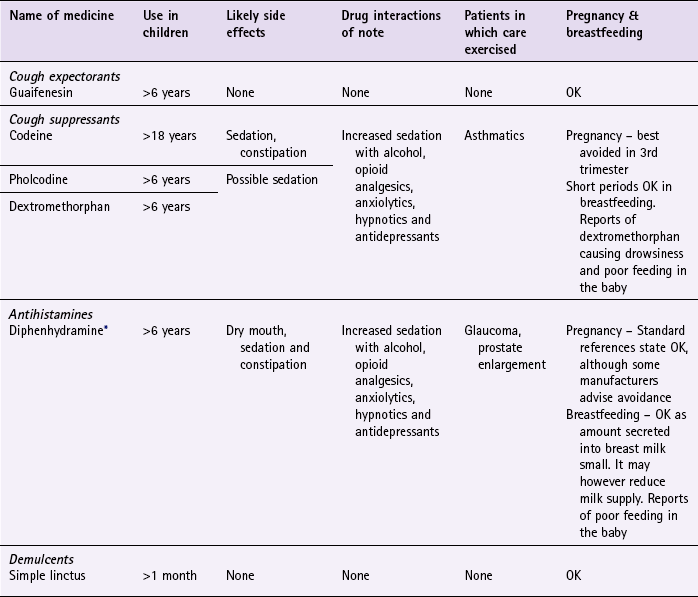

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to the cough medicines reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 1.3; useful tips relating to patients presenting with cough are given in Hints and Tips Box 1.1.

![]() Table 1.3

Table 1.3

Practical prescribing: Summary of cough medicines

*Included in some cough preparations (e.g. Benylin Children’s Night Cough & Benylin 4 Flu).

Cough expectorants

Almost all manufacturers include guaifenesin in their cough product ranges, including Benylin, Robitussin and Vicks. Children aged between 6 and 12 years should take 100 mg four times a day and the dose for adults – if it is going to work – must be 200 mg four times a day. Some products deliver suboptimal doses or the quantity taken in a single dose would be so large that the product only lasts 1 or 2 days. It is therefore advisable to always check the label of any branded guaifenesin product before recommendation to ensure the patient is receiving appropriate treatment. Guaifenesin-based products have no cautions in their use and no side effects; they are also free from clinically significant drug interactions so can be given safely with prescribed medication. Sugar-free versions (e.g. Robitussin range) are available.

Cough suppressants (codeine, pholcodine, dextromethorphan)

Codeine, pholcodine and dextromethorphan are all opiate derivatives and therefore – broadly – have the same interactions, cautions in use and side effect profile. They do interact with prescription-only medications (POMs) and also with OTC medications, especially those that cross the blood-brain barrier. Their combined effect is to potentiate sedation and it is important to warn the patient of this, although short-term use of cough suppressants with the interacting medication is unlikely to warrant dosage modification. Care should be exercised when giving cough suppressants to asthmatics because, in theory, cough suppressants can cause respiratory depression. However, in practice this is very rarely observed and does not preclude the use of cough suppressants in asthmatic patients. However, other side effects can occur (e.g. constipation), especially with codeine. If a cough suppressant is unsuitable, for example in late pregnancy and children, then a demulcent can be offered.

Pholcodine

The adult dose is 5 to 10 mL (5 to 10 mg) three or four times a day. For children aged 6 to 12 years the dose is half the adult dose, 2.5 to 5 mL (2.5 to 5 mg). Sugar-free versions (e.g. Pavacol-D) are available.

Dextromethorphan

Dextromethorphan can also be given in children over the age of 6. One product is commercially available (Vicks Cough Syrup with honey for dry coughs) – the dose being 5 mL every six hours. For adults and children aged over 12, there are a number of products available. (e.g. Benylin dry cough original and non-drowsy; Covonia original Bronchial Balsam and Robitussin for Dry coughs). The dosing is standard – 10 mL four times a day.

Antihistamines

Routine use of antihistamines is unjustified in treating non-productive cough. However, the sedative side effects from antihistamines can, on occasion, be useful to allow the patient an uninterrupted night’s sleep.

All antihistamines included in cough remedies are first-generation antihistamines and associated with sedation. They interact with other sedating medication, resulting in potentiation of the sedative properties of the interacting medicines. They also possess antimuscarinic side effects, which commonly result in dry mouth and possibly constipation. It is these antimuscarinic properties that mean patients with glaucoma and prostate enlargement should ideally avoid their use, because it could lead to increased intraocular pressure and precipitation of urinary retention.

Demulcents

Demulcents, for example simple linctus, provide a safe alternative for at-risk patient groups such as the elderly, pregnant women, young children and those taking multiple medication. They can act as useful placebos when the patient insists on a cough mixture and will not take no for an answer. If recommended they should be given three or four times a day.

References

Bjornsdottir, I, Einarson, TR, Guomundsson, LS, et al. Efficacy of diphenhydramine against cough in humans: a review. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29(6):577–583.

Eddy, NB, Friebel, H, Hahn, KJ, et al. Codeine and its alternatives for pain and cough relief. Geneva: World Health Organ; 1970. [1–253].

Findlay, JWA. Review Articles: Pholcodine. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1988;13:5–17.

Isbister, GK, Prior, F, Kilham, HA. Restricting cough and cold medicines in children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2012;48:91–98.

Smith, SM, Schroeder, K, Fahey, T. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in ambulatory settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008. [Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001831. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub3].

Vassilev, ZP, Kabadi, S, Villa, R. Safety and efficacy of over-the-counter cough and cold medicines for use in children. Expert Opinion Drug Safety. 2010;9(2):233–242.

Dicpinigaitis, PV, Colice, GL, Goolsby, MJ, et al. Acute cough: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Cough. 2009;5:11.

Knutson, D, Aring, A. Viral croup. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:535–540. 541–2

MeReC Bulletin. The management of common infections in primary care Volume 17 Number 3 December 2006.

Morice, AH, McGarvey, L, Pavord, I. Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax. 2006;61:S1–24.

NICE Guidance on TB. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG117, 2011. Available at (accessed 1 November 2012)

Pratter, MR. Overview of common causes of chronic cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 Suppl):59S–62S.

Russell, KF, Liang, Y, O’Gorman, K, et al. Glucocorticoids for croup. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011. Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001955. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001955.pub3

Sahn, S, Heffner, J. Spontaneous pneumothorax. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:868–874.

SIGN and BTS, British guideline on the management of asthma: a national clinical guideline (revised 2011). Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network and The British Thoracic Society 2011. http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/101/index.html. (accessed 1 November 2012)

British Lung Foundation. http://www.lunguk.org/

Asthma, UK. http://www.asthma.org.uk/

Action on Smoking and Health (ASH). http://www.ash.org.uk/

The British Thoracic Society. www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/

The common cold

Background

Colds, along with coughs, represent the largest caseload for primary healthcare workers. Because the condition has no specific cure and is self-limiting with two-thirds of sufferers recovering within a week, it would be easy to dismiss the condition as unimportant. However, because of the very high number of cases seen it is essential that pharmacists have a thorough understanding of the condition so that severe symptoms or symptoms suggestive of influenza are identified.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The common cold is extremely prevalent and like cough is caused by viral URTI. Children contract colds more frequently than adults with on average five to six colds per year compared to two to four colds in adults, although in children this can be as high as 12 colds per year. Children aged between 4 and 8 years are most likely to contract a cold and it can appear to a child’s parents that one cold follows another with no respite. By the age of 10 the number of colds contracted is half that observed in pre-school children. In the UK, colds peak in December and January, possibly due to increased crowding indoors during cold weather, especially among schoolchildren.

Aetiology

More than 200 different virus types can produce symptoms of the common cold, including rhinoviruses (accounting for 30–50% of all cases), coronaviruses, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus and adenovirus. Transmission is primarily by the virus coming into contact with the hands, which then touch the nose, mouth and eyes (direct contact transmission). Droplets shed from the nose coat surfaces such as door handles and telephones. Cold viruses can remain viable on these surfaces for several hours and when an uninfected person touches the contaminated surface transmission occurs. Transmission by coughing and sneezing infected mucus particles does occur, although it is a secondary mechanism. This is why good hygiene (washing hands frequently and using disposable tissues) remains the cornerstone of reducing the spread of a cold.

Once the virus is exposed to the mucosa, it invades the nasal and bronchial epithelia, attaching to specific receptors and causing damage to the ciliated cells. This results in the release of inflammatory mediators, which in turn leads to inflammation of the tissues lining the nose. Permeability of capillary cell walls increases, resulting in oedema, which is experienced by the patient as nasal congestion and sneezing. Fluid might drip down the back of the throat, spreading the virus to the throat and upper chest causing cough and sore throat.

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

It is extremely likely that someone presenting with cold symptoms will have a viral infection. Table 1.4 highlights those conditions that can be encountered by community pharmacists and their relative incidence.

Table 1.4

Causes of cold and their relative incidence in community pharmacy

| Incidence | Cause |

| Most likely | Viral infection |

| Likely | Rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, otitis media |

| Unlikely | Influenza |

Most people will accurately self-diagnose a common cold and it is the pharmacist’s role to confirm this self-diagnosis and assess the severity of the symptoms as some patients, for example the elderly, infirm and those with existing medical conditions might need greater support and care. In the first instance, the pharmacist should make an overall assessment of the person’s general state of health. Anyone with debilitating symptoms that effectively prevents them from doing their normal day-to-day routine should be managed more carefully. Whilst it is likely that a patient will have a common cold, severe colds can mimic the symptoms of flu, which is the only condition of any real significance that has to be eliminated before treatment can be given, although secondary complications can occur. Asking symptom specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 1.5).

![]() Table 1.5

Table 1.5

Specific questions to ask the patient: The common cold

| Question | Relevance |

| Onset of symptoms | Peak incidence of flu is in the winter months; the common cold occurs any time throughout the year Flu symptoms tend to have a more abrupt onset than the common cold – a matter of hours rather than 1 or 2 days Summer colds are common but they must be differentiated from seasonal allergic rhinitis (hay fever) |

| Nature of symptoms | Marked myalgia, chills and malaise are more prominent in flu than the common cold. Loss of appetite is also common with flu |

| Aggravating factors | Headache/pain that is worsened by sneezing, coughing and bending over suggests sinus complications If ear pain is present, especially in children, middle ear involvement is likely |

Clinical features of the common cold

Symptoms of the common cold are well known. However, the nature and severity of symptoms will be influenced by factors such as the causative agent, patient age and underlying medical conditions. Following an incubation period of between 1 and 3 days (although this can be as short as 10–12 hours), the patient develops a sore throat and sneezing, followed by profuse nasal discharge and congestion. Cough and UACS commonly follow. In addition, headache, mild to moderate fever (<38.9°C; 102°F) and general malaise might be present. Most colds resolve in 1 week, but up to a quarter of people will have symptoms lasting 14 days or more.

Conditions to eliminate

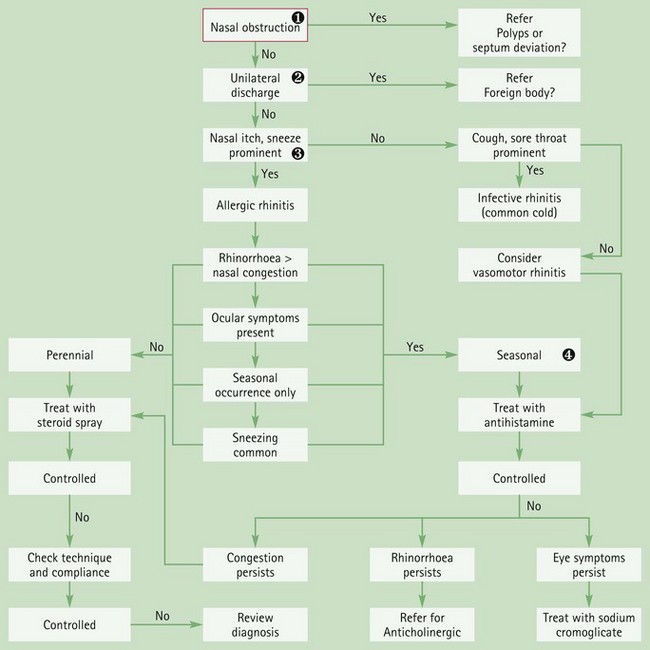

Rhinitis: A blocked or stuffy nose, whether acute or chronic in nature, is a common complaint. Rhinitis is covered in more detail on page 25 and the reader is referred to this section for differential diagnosis of rhinitis from the common cold.

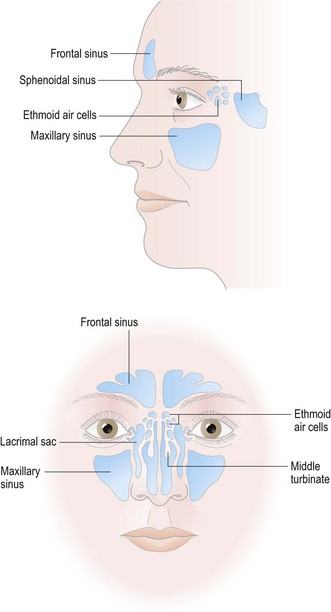

Acute rhinosinusitis: Rhinosinusitis (formerly sinusitis) is inflammation of one or more of the paranasal sinuses. Up to 2% of patients will develop acute rhinosinusitis as a complication of the common cold. Anatomically the sinuses are described in four pairs; frontal, ethmoid, maxillary and sphenoid. (Fig. 1.2) All are air-filled spaces that drain into the nasal cavity. Following a cold, sinus air spaces can become filled with nasal secretions, which stagnate because of a reduction in ciliary function of the cells lining the sinuses. Bacteria – commonly Streptococcus and Haemophilus – can then secondarily infect these stagnant secretions. It is clinically defined by at least two of the following symptoms:

The pain in the early stages tends to be relatively mild and localised, usually unilateral and dull but becomes bilateral and more severe the longer the condition persists. Bending forwards often exacerbates the pain (moving the eyes from side to side, coughing or sneezing can also increase the pain) and sinuses will be tender when gently palpated. If the ethmoid sinuses are involved, retro-orbital pain (behind the eye) is often experienced. Analgesics for pain relief and oral or nasal sympathomimetics can be tried, to remove the nasal secretions. Antibiotics are now not routinely recommended (2011) unless the person is systemically unwell or at risk of complications due to underlying medical conditions. If antibiotics are to be prescribed then amoxicillin is first line (or doxycycline if the patient has a penicillin allergy).

Acute otitis media: This is commonly seen in children following a common cold and results from the virus spreading to the middle ear via the Eustachian tube – an accumulation of pus within the middle ear or inflammation of the tympanic membrane (eardrum) results. The overriding symptom is ear pain but the child may rub or tug at the ear and be more irritable. Referral to the GP would be appropriate for auroscopical examination, unless the pharmacist is competent to perform this procedure. Examination reveals bulging tympanic membrane, loss of normal landmarks and a change in colour (red or yellow). Rupture of the eardrum causes purulent discharge and relieves the pain.

The pharmacist should offer symptomatic relief of pain with either paracetamol or ibuprofen. If symptoms persist referral to the GP for possible antibiotics should be considered. However, prescribing policy of antibiotics across the UK is variable as national guidance (2008) allows for different strategies to be followed (e.g. no prescribing or delayed prescribing policies).

Unlikely causes

Influenza: Patients often use the word ‘flu’ when describing a common cold. However, subtle differences in symptoms between the two conditions should allow differentiation. It is helpful to remember that the ‘flu’ season tends to be between December and March, whereas the common cold, although more common in winter months, can occur at anytime. The onset of influenza is sudden and the typical symptoms are shivering, chills, malaise, marked aching of limbs, insomnia, a non-productive cough (cough in the common cold is usually productive) and loss of appetite. Influenza is therefore normally debilitating and a person with flu is much more likely to send a third party into a pharmacy for medication than present in person.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Many of the active ingredients found in cold remedies are also constituents of cough products. Often they are combined and marketed as cough and cold or flu remedies. For information relating to cough ingredients the reader is referred to the sections on OTC medication for coughs (page 6).

Antihistamines

Data from a Cochrane review conducted by De Sutter et al (2003) found antihistamines when used as monotherapy did not have significant benefit clinically in nasal congestion, rhinorrhoea or sneezing in older children and adults. Additionally, they appeared not to influence subjective improvement. Only two trials were evaluated in young children, the results of which were conflicting. However, the larger study, which was more robustly conducted showed no benefit of antihistamines on the common cold.

Trials that used antihistamines in combination with other products such as decongestants and antitussives do show some beneficial global effects in adults and older children. Unfortunately, in most trials it was not possible to assess the clinical significance of these benefits because of insufficient data.

Sympathomimetics

Trial data specifically looking at the effects of decongestants in the common cold are limited. A Cochrane review (Taverner et al 2007) identified 7 trials that met their inclusion criteria, which involved topical oxymetazoline and oral pseudoephedrine and phenylpropanolamine (no longer used in the UK). Data supports their use in adults when used in single doses. However, data were lacking in children under 12 years. No difference in efficacy was found between topical or systemic products.

Multi-ingredient preparations

There is no shortage of cold and flu remedies marketed. Many combine three or more ingredients. In the majority of cases either the patient will not require all the active ingredients to treat symptoms or the ‘drug cocktail’ administered will not contain active ingredients that have proven efficacy. A more sensible approach to medicine management would be to match symptoms with active ingredients with known evidence of efficacy. In many cases this can be achieved by providing the patient with monotherapy or a product containing two active ingredients. Preparations with multiple ingredients therefore have a very limited role to play in the management of coughs and colds. However, patients might perceive that an ‘all in one’ medicine as better value for money and, potentially, compliance with such preparations might be improved.

Alternative therapies

Many products are advocated to help treat cold symptoms. Three products in particular have received much attention and are widely used.

Zinc lozenges

The argument for zinc as a plausible treatment in ameliorating symptoms of the common cold can be traced back to 1984. Since that time a number of studies have looked at zinc’s effect on treating the common cold. A recent Cochrane review (Singh and Das 2011) identified 15 randomised controlled trials that compared zinc versus placebo. Findings demonstrated that zinc (lozenges or syrup) is beneficial in reducing the duration and severity of the common cold in healthy people, when taken within 24 hours of onset of symptoms. They also reported that people taking zinc lozenges (not syrup or tablet form) were more likely to experience adverse events, including bad taste and nausea. In conclusion the authors were reluctant to make a general recommendation for the use of zinc in the treatment of the common cold because of variability in the dose, formulation and duration of use seen in the trials reviewed.

Vitamin C

Vitamin C has been widely recommended as a ‘cure’ for the common cold by many sources both medical and non-medical. However, controversy still remains whether it is an effective weapon in combating the common cold. A large number of clinical trials have investigated the effect of vitamin C on the prevention and treatment of the common cold.

A Cochrane review examining the role of vitamin C at doses above 200 mg per day in preventing and treating the common cold identified 29 studies involving 11 306 subjects (Hemilä et al 2010). The review found that vitamin C prophylaxis had no effect on the incidence of the common cold in the general community, and a small effect on the duration of a cold (equivalent to approximately 1 day less per year for adults and 4 days for children) in this population. However, they found a halving of the incidence of the common cold in people undergoing high physical stress (marathon runners, skiers and soldiers on subarctic exercises) with the prophylactic use of vitamin C. The review found the use of vitamin C once a cold had started had no consistent effect on the duration or the severity of the cold. The authors concluded that routine prophylaxis with vitamin C in the general community is unjustified, but could be beneficial to those exposed to brief periods of severe physical exercise.

Echinacea

The herbal remedy echinacea is marketed as a treatment for URTIs, including the common cold. Several reviews have reported echinacea’s effect as inconsistent. This is in part due to the limited number of trials that are comparable as different echinacea species are used as well as differing plant parts and extraction methods. A Cochrane review (Linde et al 2006) has attempted to take these factors in to consideration and found some evidence that aerial parts of Echinacea purpurea (either alcoholic extract or pressed juice) might be effective in the early treatment of colds in adults. Following on from the Cochrane review, Shah et al (2007) conducted a further review, which also included experimentally induced colds. From the 14 trials that met the inclusion criteria, results drawn showed that treatment with echinacea reduced the chance of developing a cold by about half and the duration of colds was reduced by 1.4 days. The authors did, however, acknowledge various limitations of the study, including variability in product composition and plant species used, possible bias and problems with heterogeneity.

Vapour inhalation

Steam inhalation has long been advocated to aid symptoms of the common cold, usually with the addition of menthol crystals. Trial data (review of six trials all involving adults) shows conflicting evidence in symptom relief of the common cold (Singh and Singh 2011). However, it is cheap and does not carry any significant risks apart from minor discomfort and irritation of the nose. It appears that steam is the key to symptom resolution, and not any additional ingredient that is added to the water.

Saline sprays

Saline sprays have been shown to work in observational studies. A Cochrane review exploring the use of saline irrigation on acute upper respiratory tract infections identified three randomised controlled trials involving 618 participants (Kassel et al 2010). The studies generally found no difference between saline treatment and control. Although there was some limited evidence of benefit in adults in some studies, the review was constrained by the different interventions used (e.g. nasal irrigations, drops and sprays) and the variety of outcomes measured. The authors noted that there were no serious side effects, but saline irrigation could cause minor irritation and discomfort, with up to 40% of babies not tolerating saline nasal drops.

General summary

Evidence of efficacy for Western and complementary medicines in preventing and treating the common cold are weak. Decongestants used on a when needed basis and zinc (if taken early) probably have the strongest evidence base in treating symptoms, although recent evidence suggests that echinacea might well have beneficial effects.

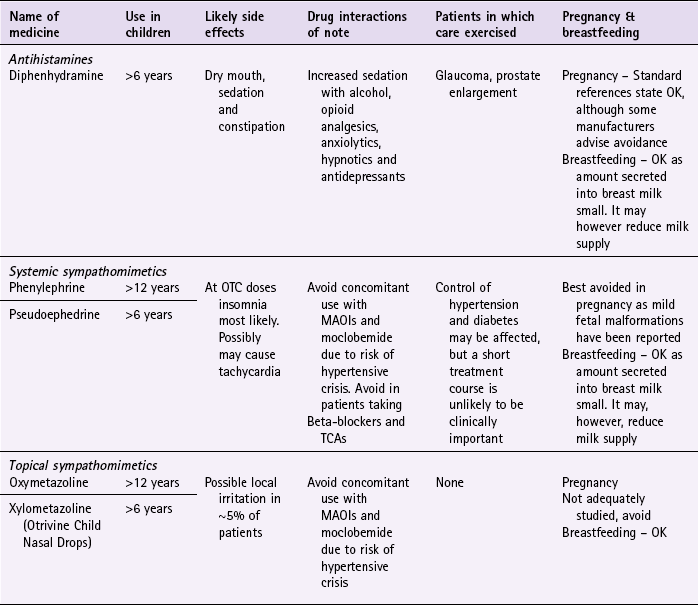

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to the cold medicines reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 1.6 and useful tips relating to patients presenting with a cold are given in Hints and Tips Box 1.2.

![]() Table 1.6

Table 1.6

Practical prescribing: Summary of cold medicines

MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; OTC over-the-counter; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Antihistamines

First-generation antihistamines are now included in relatively few cough and cold remedies. Further information on antihistamines can be found on page 8.

Sympathomimetics

Sympathomimetics serve to constrict dilated blood vessels and swollen nasal mucosa, easing congestion and helping breathing. Sympathomimetics interact with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (e.g. phenelzine, isocarboxazid, tranylcypromine and moclobemide), which can result in a fatal hypertensive crisis. The danger of the interaction persists for up to 2 weeks after treatment with MAOIs is discontinued. In addition, systemic sympathomimetics can also increase blood pressure, which might, although unlikely with short courses of treatment, alter control of blood pressure in hypertensive patients and disturb blood glucose control in diabetics. However, coadministration of medicines such as beta-blockers is probably clinically unimportant and does not preclude patients on beta-blockers from taking a sympathomimetic. A topical sympathomimetic could be given to such patients to negate this potential interaction. The most likely side effects of sympathomimetics are insomnia, restlessness and tachycardia. Patients should be advised not to take a dose just before bed-time because their mild stimulant action can disturb sleep.

As with cough remedies, the MHRA/CHM has stated that sympathomimetics (oral or nasally administered) should not be given to children under 6 years of age and for those aged between 6 and 12 duration of treatment should be limited to a maximum of 5 days. Additionally, maximum pack sizes are limited to 720 mg (the equivalent of 12 tablets or capsules of 60 mg or 24 tablets or capsules of 30 mg) and sales restricted to one pack per person owing to concerns over illicit manufacture of methylamphetamine (crystal meth) from OTC sympathomimetics.

Phenylephrine: Phenylephrine is available in a number of proprietary cold remedies, for example Lemsip and Beechams, in doses ranging between 5 and 12 mg three or four times a day for adults and children over the age of 12.

Pseudoephedrine: Pseudoephedrine is widely available as either a single ingredient (e.g. Sudafed Decongestant Tablets) or in multi-ingredient products in cold and cough remedies (e.g. Benylin Four Flu Tablets). The standard adult dose is 60 mg four times a day and half the adult dose is suitable for children between 6 and 12 years of age.

Nasal sympathomimetics: Nasal administration of sympathomimetics represents the safest route of administration. They can be given to most patient groups, including pregnant women after the first trimester and patients with pre-existing heart disease, diabetes, hypertension and hyperthyroidism. However, a degree of systemic absorption is possible, especially when using drops, as a small quantity might be swallowed, and therefore they should be avoided in patients taking MAOIs. All topical decongestants should not be used for longer than 5 to 7 days (September 2012, BNF 64 states maximum of 7 days) otherwise rhinitis medicamentosa (rebound congestion) can occur.

Ephedrine and phenylephrine: Both are short acting and need to be administered three or four times a day.

Oxymetazoline and xylometazoline: These agents are longer acting than ephedrine and phenylephrine and require less frequent dosing, typically two or three times a day. They are made by a number of manufacturers (e.g. Otrivine range, Sudafed Blocked Nose Spray and Vicks range) who all recommend use from 12 years upwards, except Otrivine Child Nasal Drops, which can be given to children over the age of six (1 or 2 drops into each nostril once or twice daily).

References

De Sutter, AIM, Lemiengre, M, Campbell, H. Antihistamines for the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003. [Issue 3].

Hemilä, H, Chalker, E, Douglas, B. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010. [Issue 3. Art. No.: CD000980. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub3].

Kassel, JC, King, D, Spurling, GKP. Saline nasal irrigation for acute upper respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010. [Issue 3. Art. No.: CD006821. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006821.pub2].

Linde, K, Barrett, B, Bauer, R, et al. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006. [Issue 1. Art. No.: CD000530. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000530.pub2].

Shah, S, Sander, S, White, CM, et al. Evaluation of echinacea for the prevention and treatment of the common cold: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:473–480.

Singh, M, Das, RR. Zinc for the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011. [Issue 2. Art. No.: CD001364. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001364.pub3].

Singh, M, Singh, M. Heated, humidified air for the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011. [Issue 5. Art. No.: CD001728. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001728.pub4].

Taverner, D, Latte, GJ. Nasal decongestants for the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. [Issue 2. Art. No.: CD001953. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001953.pub4].

Ahovuo-Saloranta, A, Rautakorpi, UM, Borisenko, OV, et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008. Issue 2. Art. No.: CD000243. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000243.pub2

Aljazaf, K, Hale, TW, Ilett, KF, et al. Pseudoephedrine: effects on milk production in women and estimation of infant exposure via breastmilk. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;56:18–24.

Chadha, NK, Chadha, R. 10-minute consultation: sinusitis. BMJ. 2007;334:1165. (2 June), doi:10.1136/bmj.39161.557211.47

Sanders, S, Glasziou, PP, Del Mar, CB, et al. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004. Issue 1. Art. No.: CD000219. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000219.pub2

Scadding, GK, Durham, SR, Mirakian, R, et al. BSACI guidelines for the management of rhinosinusitis and nasal polyposis. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 2007;38(2):260–275.

Common Cold Centre. http://www.cf.ac.uk/biosi/associates/cold/

SIGN Guidelines on Diagnosis and management of childhood otitis media in primary care. http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/66/index.html.

Commoncold Inc. http://www.commoncold.org

Sore throats

Background

Any part of the respiratory mucosa of the throat can give rise to symptoms of throat pain. This includes the pharynx (pharyngitis) and tonsils (tonsillitis), yet clinical distinction between pharyngitis and tonsillitis is unclear and the term sore throat is commonly used. Pain can range from scratchiness to severe pain. Sore throats are often associated with the common cold. However in this section, people who present with sore throat as the principal symptom are considered.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Sore throats are extremely common. UK figures show that a GP with a list size of 2000 patients will see about 120 people each year with a throat infection. However, four to six times as many people will visit the pharmacy and self-treat. Figures from other countries such as New Zealand and Australia broadly support UK findings. On average an adult will experience two to three sore throats each year.

Aetiology

Viral infection accounts for between 70 and 90% of all sore throat cases. Remaining cases are nearly all bacterial; the most common cause being Group A beta-haemolytic Streptococcus (also known as Streptococcus pyogenes). A fuller account of the aetiology of viral and bacterial pathogens that affect the upper respiratory tract appears on page 12.

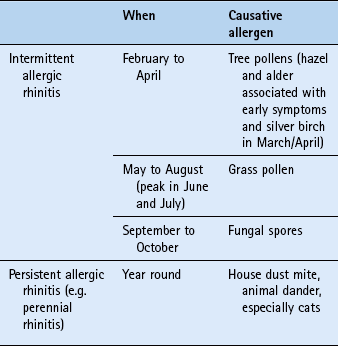

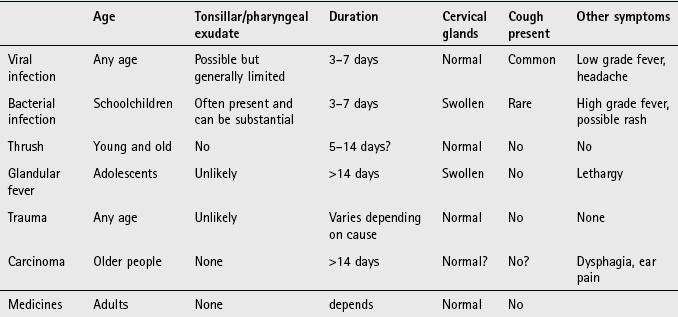

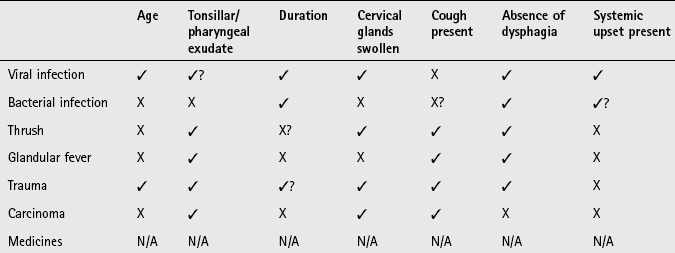

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

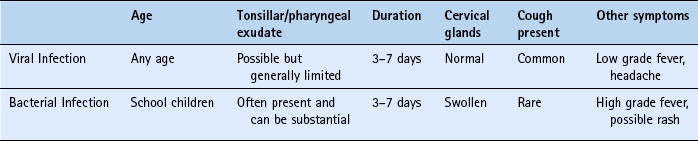

The overwhelming majority of cases will be acute and self-limiting URTI, whether viral or bacterial in origin. Clinically, differentiation between viral and bacterial infection is extremely difficult, although specific symptom clusters are suggestive for sore throat of bacterial origin (see conditions to eliminate) but these are by no means fool proof. Other causes of sore throat also need to be considered and Table 1.7 highlights those conditions that can be encountered by community pharmacists and their relative incidence. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine the cause and whether referral is needed (Table 1.8).

Table 1.7

Causes of sore throat and their relative incidence in community pharmacy

| Incidence | Cause |

| Most likely | Viral infection |

| Likely | Streptococcal infection |

| Unlikely | Glandular fever, trauma |

| Very unlikely | Carcinoma, medicines |

![]() Table 1.8

Table 1.8

Specific questions to ask the patient: Sore throat

| Question | Relevance |

| Age of the patient | Although viruses are the commonest cause of sore throat there are epidemiological variance with age: Under 3 years old Streptococcus is uncommon Streptococcal infections are more prevalent in people under the age of 30, particularly those of school age (5 to 10 years) and young adults (15–25 years old) Viral causes are the commonest cause of sore throat in adults Glandular fever is most prevalent in adolescents |

| Tender cervical glands | On examination, patients suffering from glandular fever and streptococcal sore throat often have markedly swollen glands. This is less so in viral sore throat |

| Tonsillar exudate present | Marked tonsillar exudate is more suggestive of a bacterial cause than a viral cause |

| Ulceration | Herpetiform and herpes simplex ulcers can also cause soreness in the mouth especially in the posterior part of the mouth. |

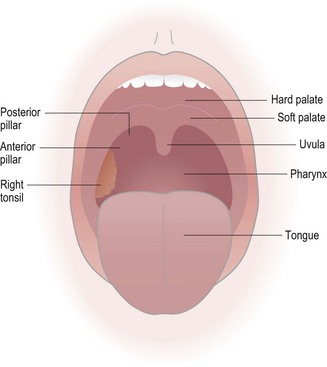

Physical examination

After questioning, the pharmacist should inspect the mouth and cervical glands (located just below the angle of the jaw) to substantiate the differential diagnosis. (Fig. 1.3) Using a good light source (e.g. pen torch) ask the patient to say ‘ah’; this should allow you to see the pharynx well. When examining the mouth pay particular attention to the fauces and tonsils. Are they red and swollen? Is there any exudate present? Is there any sign of ulceration?

Clinical features of sore throat

Many studies have now shown that it is exceedingly difficult to differentiate viral and bacterial infection on patient history and clinical findings. Patients will present with a sore throat as an isolated symptom or as part of a cluster of symptoms that include rhinorrhoea, cough, malaise, fever, headache and hoarseness (laryngitis). Symptoms are relatively short-lived with 40% of people being symptom free after 3 days and 85% of people symptom free after 1 week.

Conditions to eliminate

Streptococcal sore throat: Patients who present with pharyngeal or tonsillar exudates, swollen anterior cervical glands, high grade fever (over 39.4°C; 101°F) and absence of cough are more likely to have a bacterial infection. However, even if the patient exhibits all these four ‘classic’ symptoms up to 40% will not have bacterial infection. To further compound the difficulty of diagnosis the routine use of throat swabs performed by GPs are not recommended as asymptomatic carriage of Streptococcus affects up to 40% of people making it impossible to differentiate between infection and carriage. Table 1.9 summarises the potential distinguishing features of viral and bacterial infection.

If bacterial infection is suspected then referral to the GP is appropriate. The use of antibiotics in such situations is debatable as a Cochrane review (Spinks et al 2006) found that the absolute benefit of antibiotics was modest, with an average reduction in illness time of 1 day. The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence recommend a 10 day course of penicillin or erythromycin (where an allergy to penicillin exists) if the patient has a history of rheumatic fever, increased risk from acute infection, unilateral peritonsillitis and marked systemic upset.

Glandular fever (infectious mononucleosis): Glandular fever is caused by the Epstein–Barr virus and is often called the kissing disease because transmission primarily occurs from saliva. It has a peak incidence in adolescents and young adults. The signs and symptoms of glandular fever can be difficult to distinguish from sore throat because it is characterised by pharyngitis (occasionally with exudates), fever, cervical lymphadenopathy and fatigue. The person can also suffer from general malaise prior to the start of the other symptoms. A macular rash can also occur in a small proportion of patients.

Trauma-related sore throat: Occasionally patients develop a sore throat from direct irritation of the pharynx. This can be due to substances such as cigarette smoke, a lodged foreign body or from acid reflux.

Medicine induced sore throat: A rare complication associated with certain medication is agranulocytosis, which can manifest as a sore throat. The patient will also probably present with signs of infection including fever and chills. Medicines known to cause this adverse event are listed in Table 1.10.

Laryngeal and tonsillar carcinoma: Both these cancers have a strong link with smoking and excessive alcohol intake, and are more common in men than women. Sore throat and dysphagia are the common presenting symptoms. In addition, patients with tonsillar cancer often develop referred ear pain. Any person, regardless of age, that presents with dysphagia should be referred.

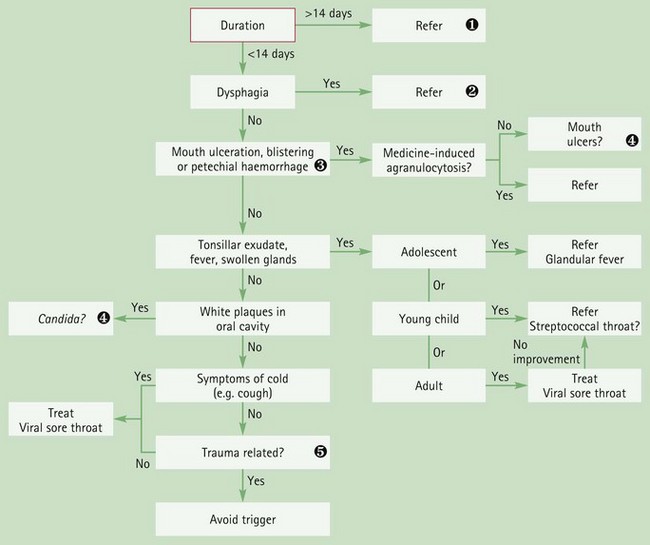

Figure 1.4 will help in the differentiation of serious and non-serious conditions in which sore throat is a major presenting complaint.

Fig. 1.4 Primer for differential diagnosis of sore throat![]() Duration longer than 2 weeks

Duration longer than 2 weeks

The overwhelming majority of cases resolve spontaneously in this time; it is therefore prudent to refer these cases for further investigation.![]() Dysphagia

Dysphagia

True difficulty in swallowing (i.e. not just caused by pain but by a mechanical blockage) should be referred. Most patients with sore throat will find it less easy to swallow but this has to be differentiated from actual difficulty in swallowing. Severe inflammation of the throat can cause restriction of the airways and thus hinder breathing. Additionally, rare causes of sore throat also have associated dysphagia symptoms, such as peritonsillar abscess, thyroiditis and oesophageal carcinoma.![]() Signs of agranulocytosis

Signs of agranulocytosis

A severe reduction in the number of white blood cells can result in neutropenia, which is manifested as fever, sore throat, ulceration and small haemorrhages under the skin.![]() Mouth ulceration and Candida (oral thrush) primers

Mouth ulceration and Candida (oral thrush) primers

See Chapter 6 and Figs 6.6 & 6.7 for further differentiation of these conditions.![]() Trauma related

Trauma related

Simple acts of drinking fluids that are too hot can give rise to ulceration of the pharynx. It is worth asking whether any such factors could have triggered the sore throat.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

The majority of sore throats are viral in origin and self-limiting. Medication therefore aims to relieve symptoms and discomfort whilst the infection runs its course. Lozenge and spray formulations incorporating antibacterial and anaesthetics provide the mainstay of treatment for which there is no shortage on the market. In addition systemic analgesics and antipyretics will help reduce the pain associated with sore throat.

Local anaesthetics

Lidocaine and benzocaine are included in a number of marketed products. Very few published clinical trials involving products marketed for sore throat have been conducted yet local anaesthetics have proven efficacy. It therefore appears manufacturers are using trial data on local anaesthetic efficacy for conditions other than sore throats to substantiate their effect.

Antibacterial and antifungal agents

Antibacterial agents include chlorhexidine, tyrothricin, dequalinium chloride and benzalkonium chloride. In vitro testing has shown that many of the proprietary products do have antibacterial activity, and some inhibit Candida albicans growth. In vivo tests have also shown antibacterial effects.

The use of antibacterial and antifungal agents should not be routinely recommended since the vast majority of sore throats are caused by viral infections for which they have no action against. As adverse effects are rare and stimulation of saliva from sucking the lozenge may confer symptomatic relief, the use of such products may be justified.

Anti-inflammatories

Benzydamine is available as a spray or mouthwash and one small trial involving benzydamine as a gargle resulted in significantly greater relief of pain compared to placebo (Thomas et al 2000).

Analgesia

There is good evidence to show that simple systemic analgesia, for example paracetamol, aspirin and ibuprofen, is effective in reducing the pain associated with sore throat. Thomas et al (2000) undertook a review of treatments other than antibiotics for sore throats. They identified 22 trials, 13 of which involved NSAIDs (primarily ibuprofen) or paracetamol, and found both NSAIDs and paracetamol were effective. However, the authors noted that patients took the medications regularly in the studies, not on an ‘as needed’ basis, and this should be stressed to patients presenting with sore throats. Flurbiprofen lozenges have also been shown to be more effective than placebo in reducing pain associated with sore throat. However, the clinical significance of the benefit is uncertain, and comparisons with active treatments are lacking. In a review in Prescrire in 2007 the conclusion was that ‘flurbiprofen lozenges have a negative risk-benefit balance … it is better to suck real sweets and, if necessary, take paracetamol’ (Anonymous 2007).

Aspirin and salt water gargles

Gargling with aspirin or salt water is a common lay remedy for sore throat. No trials appear to have been conducted on their effectiveness and until such time that evidence becomes available they should not be recommended.

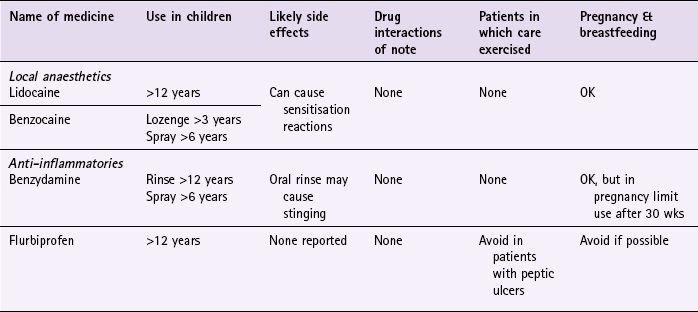

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to the sore throat medicines reviewed under ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 1.11 and useful tips relating to patients presenting with a sore throat are given in Hints and Tips Box 1.3.

Local anaesthetics (lidocaine, benzocaine)

All local anaesthetics have a short duration of action and frequent dosing is required to maintain the anaesthetic effect whether formulated as a lozenge or spray. They appear to be free from any drug interactions, have minimal side effects and can be given to most patients, including pregnant and breastfeeding women. A small number of patients may experience a hypersensitivity reaction with either ingredient although it appears to be more common with benzocaine. Owing to differences in the chemical structure of these products cross sensitivity is unusual and therefore if a patient experiences side effects with one then the other can be tried. Most products do contain a sugar base but the amount of sugar is too small to substantially affect blood glucose control and therefore can be recommended to diabetic patients.

Lidocaine: Lidocaine is available as a spray (Covonia Throat Spray (0.05%) and Dequaspray (2.0%)). Lidocaine is licensed only for adults and is best taken on a when needed basis. As both proprietary products have differing strengths of lidocaine the dosing schedules differ – for Covonia the dose is three to five sprays between six and 10 times a day and for Dequaspray the dose is three sprays every 3 hours when needed up to a maximum of six times per day.

Benzocaine: Unlike lidocaine, benzocaine can be given to children both in lozenge and spray formulations. Lozenges are available and can be given from aged 3 and over (Tyrozets 1 lozenge (5 mg) every 3 hours when needed, maximum six in 24 hours); adults can take up to eight (10 mg) in 24 hours every 2–3 hours when needed (e.g. Tyrozets, Merocaine, Dequacaine). Additionally, children over the age of 6 can also use a spray formulation (Ultra Chloraseptic (0.71%) or AAA Spray (1.5%)), for which the dose is one spray every 2 to 3 hours.

Anti-inflammatories (benzydamine and flurbiprofen)

Anti-inflammatories have the advantage over local anaesthetics in that they do not generally anaesthetise the entire mouth.

Benzydamine (Difflam Sore Throat Rinse, Difflam Spray): The rinse should be used by adults and children over the age of 12 every  to 3 hours when required. It has no drug interactions of note, can be used by all patient groups and only occasionally does the rinse cause stinging, in which case the rinse can be diluted with water. The manufacturers advise that the product should be stored in the box away from direct sunlight, however, the stability of the product is not known to be affected by sunlight.

to 3 hours when required. It has no drug interactions of note, can be used by all patient groups and only occasionally does the rinse cause stinging, in which case the rinse can be diluted with water. The manufacturers advise that the product should be stored in the box away from direct sunlight, however, the stability of the product is not known to be affected by sunlight.

The dosing for the spray is the same as the rinse but unlike the rinse it can be used in children. For those under the age of six the dose is based on mg/kg dosing, for those aged 6 to 12 they should use four puffs and adults four to eight puffs.

Flurbiprofen (Strefen): Strefen lozenges (8.75 mg flurbiprofen) can only be given to adults and children over the age of 12 years. The dose is one lozenge to be sucked every 3 to 6 hours with a maximum of five lozenges in 24 hours. They are contraindicated in patients with peptic ulceration and those patients allergic to flurbiprofen, and must be used with caution in pregnant and breastfeeding women.

References

Anonymous. Flurbiprofen: new indication. Lozenges: NSAIDs are not to be taken like sweets!. Prescrire Int. 2007;16:13.

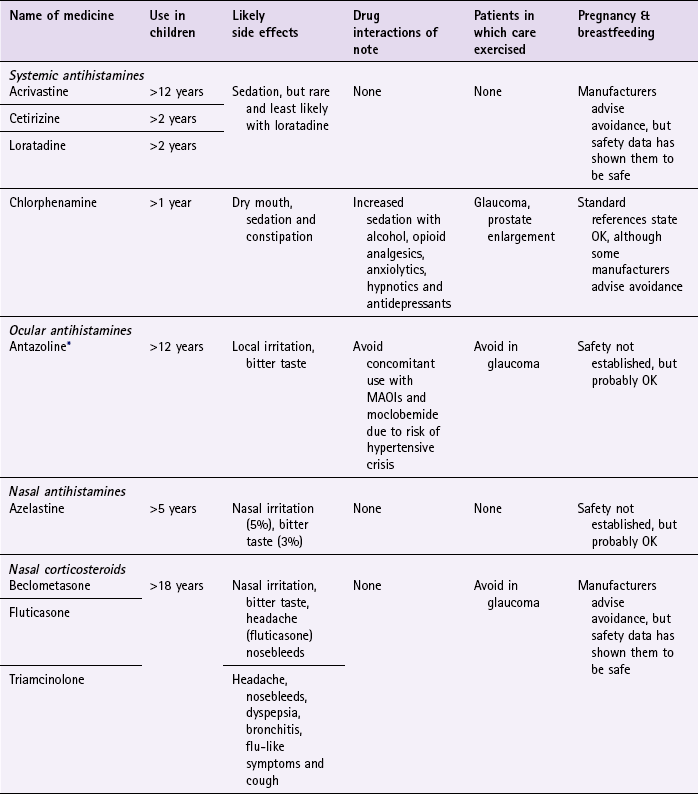

Spinks, A, Glasziou, PP, Del Mar, CB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006. [Issue 4. Art. No.: CD000023. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000023.pub3].