Gastroenterology

Background

The main function of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is to break food down in to a suitable energy source to allow normal physiological function of cells. Needless to say, the process is complex and involves many different organs. Consequently, there are many conditions that affect the GI tract, some of which are acute and self-limiting and respond well to OTC medication and others that are serious and require referral.

General overview of the anatomy of the GI tract

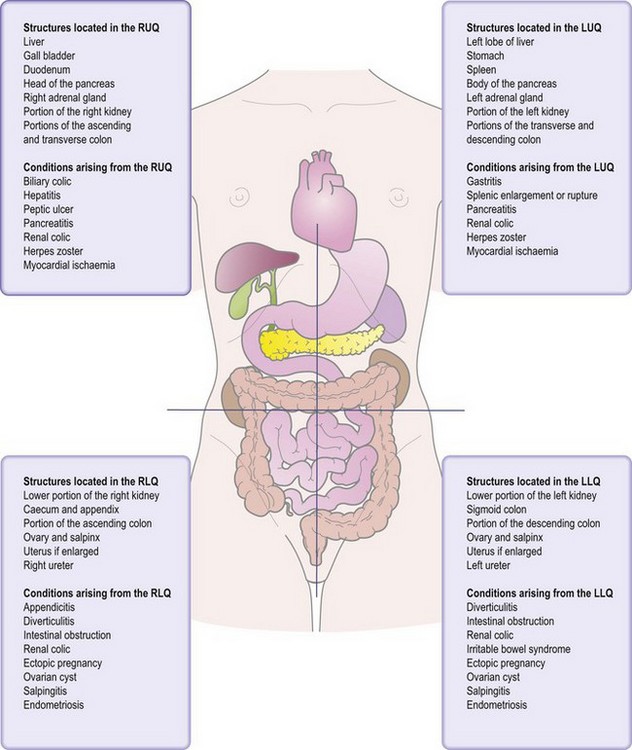

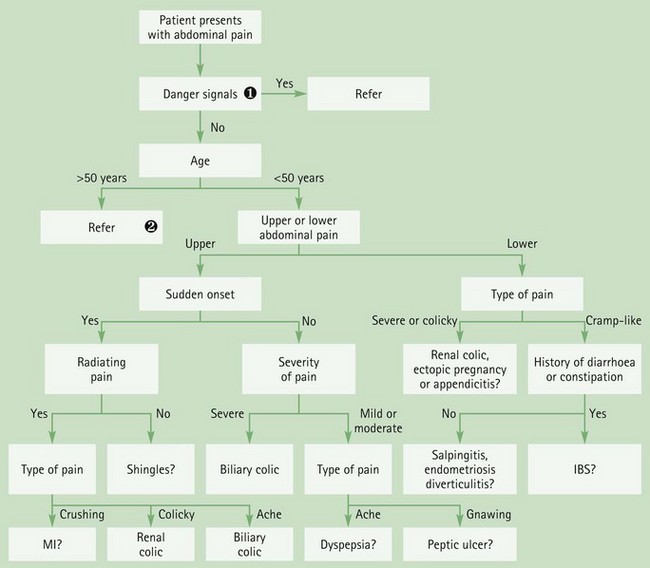

It is vital that pharmacists have a sound understanding of GI tract anatomy. Many conditions will present with similar symptoms and from similar locations, for example abdominal pain, and the pharmacist will need a basic knowledge of GI tract anatomy – and in particular of where each organ of the GI tract is located – to facilitate a correct differential diagnosis.

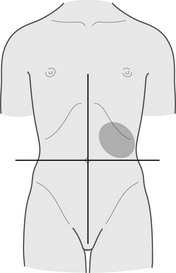

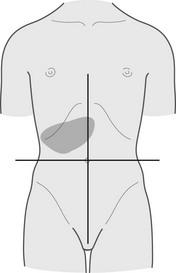

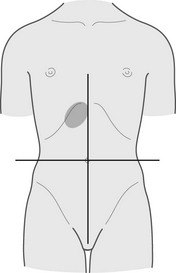

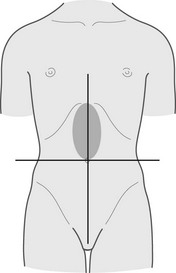

Stomach

The stomach is roughly ‘J’ shaped and receives food and fluid from the oesophagus. It empties into the duodenum. It is located slightly left of midline and anterior (below) to the rib cage. The lesser curvature of the stomach sits adjacent to the liver.

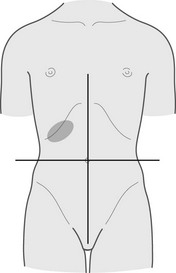

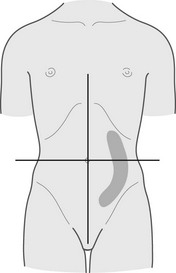

Liver

The liver is located below the diaphragm and located mostly right of midline in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen. The liver performs many functions, including carbohydrate, lipid and protein metabolism and the processing of many medicines.

History taking and physical exam

A thorough patient history is essential as physical examination of the GI tract in a community pharmacy is limited to inspection of the mouth. This should allow confirmation of the diagnoses for conditions such as mouth ulcers and oral thrush. A description of how to examine the oral cavity appears in the following section.

Conditions affecting the oral cavity

The process of digestion starts in the oral cavity. The tongue and cheeks position large pieces of food so that the teeth can tear and crush food into smaller particles. Saliva moistens, lubricates and begins the process of digesting carbohydrates (by secreting amylase enzymes) prior to swallowing.

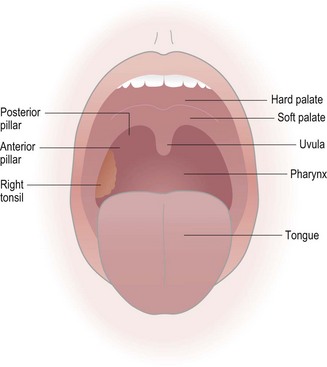

The physical exam

The oral cavity can easily be observed in the pharmacy provided the mouth can be viewed with a good light source, preferably a pen torch (Fig 6.1). The patient will usually present with some form of oral lesion and/or pain in a particular part of the mouth. The pharmacist should examine this area carefully, but the rest of the oral cavity should also be inspected. Checks for periodontal disease (bleeding gums) and other sites of mouth soreness should be performed.

The floor of the mouth and underside of the tongue can be viewed by asking the patient to curl the tongue toward the roof of the mouth; the buccal mucosa is best observed when the patient half opens the mouth.

Mouth ulcers

Aphthous ulcers, more commonly known as mouth ulcers, is a collective term used to describe various different clinical presentations of superficial painful oral lesions that occur in recurrent bouts at intervals between a few days to a few months. The majority of patients (80%) who present in a community pharmacy will have minor aphthous ulcers (MAU). It is the community pharmacists’ role to exclude more serious pathology, for example, systemic causes and carcinoma.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The prevalence and epidemiology of MAU is poorly understood. They occur in all ages but it has been reported that they are more common in patients aged between 20 and 40, and up to 66% of young adults give a history consistent with MAU. Lifetime prevalence is estimated to affect one in five of the general population.

Aetiology

The cause of MAU is unknown. A number of theories have been put forward to explain why people get MAU, including a genetic link, stress, trauma, food sensitivities, nutritional deficiencies (iron, zinc and vitamin B12) and infection, but none have so far been proven.

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

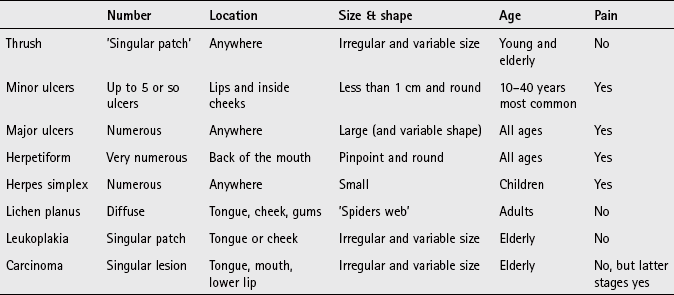

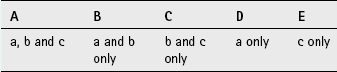

There are three main clinical presentations of ulcers: minor, major or herpetiform. Although it is most likely the patient will be suffering from MAU (Table 6.1) it is essential that these and other causes are recognised and referred to the GP for further evaluation.

Table 6.1

Causes of ulcers and their relative incidence in community pharmacy

| Incidence | Cause |

| Most likely | Minor aphthous ulcers (MAU) |

| Likely | Major aphthous ulcers, Trauma |

| Unlikely | Herpetiform ulcers, herpes simplex, oral thrush medicine-induced |

| Very unlikely | Oral carcinoma, erythema multiforme (Steven’s Johnson syndrome), Behçet’s syndrome |

A number of ulcer-specific questions should always be asked of the patient (Table 6.2) and an inspection of the oral cavity should also be performed to help aid the diagnosis.

![]() Table 6.2

Table 6.2

Specific questions to ask the patient: Mouth ulcers

| Question | Relevance |

| Number of ulcers | MAU occur singly or in small crops. A single large ulcerated area is more indicative of pathology outside the remit of the community pharmacist Patients with numerous ulcers are more likely to be suffering from major or herpetiform ulcers rather than MAU |

| Location of ulcers | Ulcers on the side of the cheeks, tongue and inside of the lips are likely to be MAU Ulcers located toward the back of the mouth are more consistent with major or herpetiform ulcers |

| Size and shape | Irregular-shaped ulcers tend to be caused by trauma. If trauma is not the cause then referral is necessary to exclude sinister pathology If ulcers are large or very small they are unlikely to be caused by MAU |

| Painless ulcers | Any patient presenting with a painless ulcer in the oral cavity must be referred. This can indicate sinister pathology such as leukoplakia or carcinoma |

| Age | MAU in young children (<10 years old) is not common and other causes such as primary infection with herpes simplex should be considered If ulcers appear for the first time after adolescence then the diagnostic probability is increased for them to be caused by things other than MAU |

Clinical features of minor aphthous ulcers

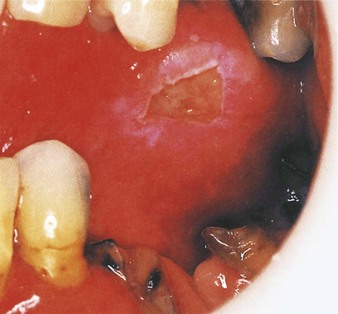

The ulcers of MAU are roundish, grey-white in colour and painful. They are small – usually less than 1 cm in diameter – and shallow with a raised red rim. Pain is the key presenting symptom and can make eating and drinking difficult, although pain subsides after three or four days. They rarely occur on the gingival mucosa and occur singly or in small crops of up to five ulcers. It normally takes 7 to 14 days for the ulcers to heal but recurrence typically occurs after an interval of 1 to 4 months (Fig. 6.2).

Conditions to eliminate

Major aphthous ulcers: These are characterised by large (greater than 1 cm in diameter), numerous ulcers, occurring in crops of 10 or more. The ulcers often coalesce to form one large ulcer. The ulcers heal slowly and can persist for many weeks (Fig. 6.3).

Trauma: Trauma to the oral mucosa will result in damage and ulceration. Trauma may be mechanical (e.g. tongue biting) or thermal resulting in ulcers with an irregular border. Patients should be able to recall the traumatic event and have no history of similar ulceration or signs of systemic infection (Fig. 6.4).

Unlikely causes

Herpetiform ulcers: Herpetiform ulcers are pinpoint and occur in large crops of up to 100 at a time. They usually heal within a month and often occur in the posterior part of the mouth, an unusual location for MAU (Fig. 6.5). Both herpetiform and major aphthous ulcers are approximately ten times less common than MAU.

Oral thrush

Oral thrush usually presents as creamy-white soft elevated patches. It is covered in more detail in the next section and the reader is referred to page 139 for differential diagnosis of thrush from other oral lesions.

Herpes simplex

Herpes simplex virus is a common cause of oral ulceration in children. Primary infection results in ulceration of any part of the oral mucosa, especially the gums, tongue and cheeks. The ulcers tend to be small and discrete and many in number. Prior to the eruption of ulcers the person might show signs of systemic infection such as fever and pharyngitis.

Medicine-induced ulcers

A number of case reports have been received of medication causing ulcers. These include cytotoxic agents, nicorandil, alendronate, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and beta-blockers. Ulcers are often seen at the start of therapy or when the dose is increased.

Very unlikely causes

Carcinoma: In 2009, over 6000 cases of oral cancer were confirmed. It is twice as common in men than women. Incidence rates increase sharply beyond 45 years of age. In men the highest incidence is seen in those aged 60–69, and in women it peaks in the over 80s. Smoking and excess alcohol consumption are two major risk factors.

The majority of cancers are noted on the side of the tongue, mouth and lower lip. Initial presentation ranges from painless spots, lumps or ulcers in the mouth or lip area that fail to resolve. Over time these become painful, change colour crust over or bleed. The painless nature of early symptoms leads people to seek help only when other symptoms become apparent. Symptoms therefore can be present for a number of weeks before the patient presents to a health care practitioner. Urgent referral is needed as survival rates increase dramatically if the disease is diagnosed in its early stages.

Erythema multiforme: Infection or drug therapy can cause erythema multiforme, although in about 50% of cases no cause can be found. Symptoms are sudden in onset causing widespread ulceration of the oral cavity. In addition the patient can have annular and symmetric erythematous skin lesions located toward the extremities. Conjunctivitis and eye pain is also common.

Behcet’s syndrome: Most patients will suffer from recurrent, painful major aphthous ulcers that are slow to heal. Lesions are also observed in the genital region and eye involvement (iridocyclitis) is common.

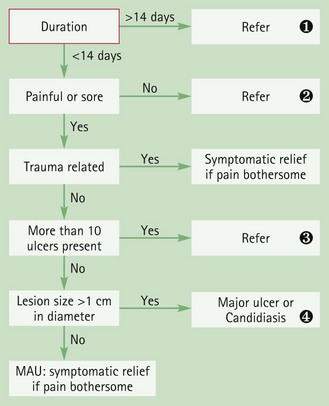

Figure 6.6 will aid the differentiation between serious and non-serious conditions that cause mouth ulcers.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

A wide range of products are used for the temporary relief and treatment of mouth ulcers. These products contain corticosteroids, local anaesthetics, antibacterials, astringents and antiseptics. Until, recently, corticosteroids were available OTC (triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% in Orabase and hydrocortisone sodium succinate pellets) but these have been discontinued by the manufacturers. This is unfortunate as a review in BMJ Clinical Evidence found corticosteroids did reduce the duration of pain with MAU (http://exodontia.info/files/BMJ_Clinical_Evidence_2007_Recurrent_Aphthous_Ulcers.pdf; accessed 22 November 2012).

Antibacterial agents (e.g. chlorhexidine)

A number of random controlled trials have investigated antibacterial mouthwashes containing chlorhexidine gluconate. Data from some, but not all studies, have found that they reduced the pain and severity of each episode of ulceration.

Products containing anaesthetic or analgesics

There is very little trial data to support the pain-relieving effect of anaesthetics or analgesics in MAU, apart from choline salicylate. However, these preparations are clinically effective in other painful oral conditions. It is therefore not unreasonable to expect some relief of symptoms to be shown when using these products to treat MAU.

Choline salicylate

Choline salicylate has been shown to exert an analgesic effect in a number of small studies. However, only one study by Reedy (1970) involving 27 patients evaluated choline salicylate in the treatment of oral aphthous ulceration. No significant differences were found between choline salicylate and placebo in ulcer resolution but choline salicylate was found to be significantly superior to placebo in relieving pain.

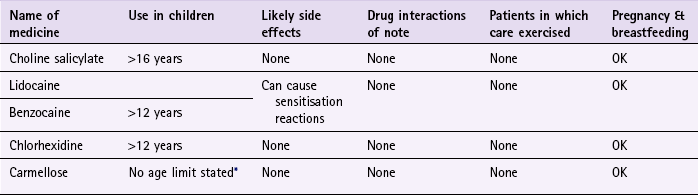

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to the medicines used for ulcers reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 6.3; useful tips relating to patients presenting with ulcers are given in Hints and Tips Box 6.1.

![]() Table 6.3

Table 6.3

Practical prescribing: Summary of medicines for ulcers

*Children should not be routinely given products as ulcers are rare in this age group.

Antibacterial agents (e.g. chlorhexidine)

Chlorhexidine (e.g. Corsodyl) mouthwash is indicated as an aid in the treatment and prevention of gingivitis and in the maintenance of oral hygiene, which includes the management of aphthous ulceration. Ten mL of the mouthwash should be rinsed around the mouth for about 1 minute twice a day. It can be used by all patient groups, including those who are pregnant and breastfeeding. Side effects associated with its use include reversible tongue and tooth discolouration, burning of the tongue and taste disturbance.

Choline salicylate (Bonjela Cool)

Adults and children over 16 years old should apply the gel, using a clean finger, over the ulcer when needed, but limit this to every 3 hours. It is a safe medicine and can be given to all patient groups. It is not known to interact with any medicines or cause any side effects.

Local anaesthetics (lidocaine e.g. Anbesol range, Iglu gel, Medijel) and benzocaine (e.g. Oralgel & Oralgel Extra Strength).

All local anaesthetics have a short duration of action; frequent dosing is therefore required to maintain the anaesthetic effect. They are thus best used on a when needed basis although the upper limit on the number of applications allowed does vary depending on the concentration of anaesthetic included in each product. They appear to be free from any drug interactions, have minimal side effects and can be given to most patients. A small percentage of patients might experience a hypersensitivity reaction with lidocaine or benzocaine; this appears to be more common with benzocaine.

Carmellose sodium (Orabase Protective Paste)

Orabase can be applied as frequently as requred. It is important that it is dabbed on, and not rubbed on, for it to stick correctly. Also, patients should be discouraged from putting too much on as the excess can peel off leaving the lesion exposed. There are no apparent interactions, and Orabase can be used in all patient groups.

Browne, RM, Fox, EC, Anderson, RJ. Topical triamcinolone acetonide in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. A clinical trial. Lancet. 1968;1:565–567.

MacPhee, IT, Sircus, W, Farmer, ED, et al. Use of steroids in treatment of aphthous ulceration. Br Med J. 1968;2(598):147–149.

Scully, C. Aphthous ulceration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:165–172.

Truelove, SC, Morris-Owen, RM. Treatment of aphthous ulceration of the mouth. Br Med J. 1958;1:603–607.

Zakrzewska, JM. Fortnightly review: oral cancer. Br Med J. 1999;318:1051–1054.

British Association of Dermatologists. Multi-professional Guidelines for the Management of the Patient with Primary Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. http://www.bad.org.uk/Portals/_Bad/Guidelines/Clinical%20Guidelines/SCC%20Guidelines%20Final%20Aug%2009.pdf, 2009.

General site on oral health. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/mouthandteeth.html

The Behçet’s Syndrome Society. http://www.behcets.org.uk/menus/main.asp

The British Dental Health Foundation. http://www.dentalhealth.org.uk/

Oral thrush

Background

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (oral thrush) is an opportunistic mucosal infection and is unusual in healthy adults. If oral thrush is suspected in this population community pharmacists should determine if any identifiable risk factors. A healthy adult with no risk factors generally requires referral to the GP.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The very young (neonates) and the very old are most likely to suffer from oral thrush. It has been reported that 5% of newborn infants and 10% of debilitated elderly patients suffer from oral thrush. Most other cases will be associated with underlying pathology such as diabetes, xerostomia (dry mouth), patients who are immunocompromised or be attributable to identifiable risk factors such as recent antibiotic therapy, inhaled corticosteroids, and ill-fitting dentures.

Aetiology

It is reported that Candida albicans is found in the oral cavity of 30–60% of healthy people in developed countries (Gonsalves et al 2007). Prevalence in denture wearers is even higher. It is transmitted directly between infected people or via objects that can hold the organism. Changes to the normal environment in the oral cavity will allow C. albicans to proliferate.

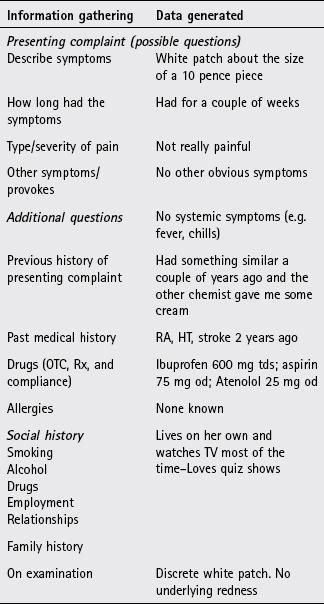

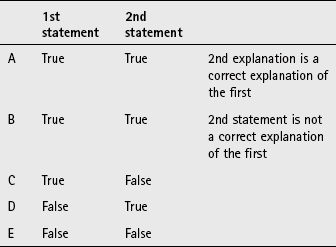

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Oral thrush is not difficult to diagnose provided a careful history is taken and an oral examination performed. It is the role of the pharmacist to eliminate underlying pathology and exclude risk factors. A number of other conditions need to be considered (Table 6.4) and specific questions asked of the patient (Table 6.5). After questioning the pharmacist should inspect the oral cavity to confirm the diagnosis.

Table 6.4

Causes of oral lesions and their relative incidence in community pharmacy

| Incidence | Cause |

| Most likely | Thrush |

| Likely | Minor aphthous ulcers, medicine induced, ill-fitting dentures |

| Unlikely | Lichen planus, underlying medical disorders, e.g. diabetes, xerostomia (dry mouth) and immunosuppression, major & herpetiform ulcers, herpes simplex |

| Very Unlikely | Leukoplakia, squamous cell carcinoma |

![]() Table 6.5

Table 6.5

Specific questions to ask the patient: Oral thrush

| Question | Relevance |

| Size and shape of lesion | Typically, patients with oral thrush present with ‘patches’. They tend to be irregularly shaped and vary in size from small to large |

| Associated pain | Thrush usually causes some degree of discomfort or pain. Painless patches, especially in people aged over 50, should be referred to exclude sinister pathology such as leukoplakia |

| Location of lesions | Oral thrush often affects the tongue and cheeks, although if precipitated by inhaled steroids the lesions appear on the pharynx |

Clinical features of oral thrush

The classical presentation of oral thrush is of creamy-white soft elevated patches that can be wiped off revealing underlying erythematous mucosa (Fig. 6.7). Pain, soreness, altered taste and a burning tongue can be present. Lesions can occur anywhere in the oral cavity but usually affect the tongue, palate, lips and cheeks. Patients sometimes complain of malaise and loss of appetite. In neonates, spontaneous resolution usually occurs but can take a few weeks.

Conditions to eliminate

Minor aphthous ulcers: Mouth ulcers are covered in more detail on page 134 and the reader is referred to this section for differential diagnosis of these from oral thrush.

Unlikely causes

Lichen planus: Lichen planus is a dermatological condition with lesions similar in appearance to plaque psoriasis. In about 50% of people the oral mucous membranes are affected. The cheeks, gums or tongue develop white, slightly raised painless lesions that look a little like a spider’s web. Other symptoms can include soreness of the mouth and a burning sensation. Occasionally, lichen planus of the mouth occurs without any skin rash.

Underlying medical disorders: As stated previously, oral thrush is unusual in the adult population. Patients are at greater risk of developing thrush if they suffer from medical conditions such as diabetes, xerostomia (dry mouth) or are immunocompromised.

Other forms of ulceration (e.g. major and herpetiform ulcers, herpes simplex): These are covered in more detail on page 135 and the reader is referred to this section for differential diagnosis of these from oral thrush.

Very unlikely causes

Leukoplakia: Leukoplakia is a predominantly white lesion of the oral mucosa that cannot be characterised as any other definable lesion and is therefore a diagnosis based on exclusion (Fig. 6.8). It is often associated with smoking and is a precancerous lesion, although epidemiological data suggests that annual transformation rate to squamous cell carcinoma is approximately 1%. Patients present with a symptomless white patch that develops over a period of weeks on the tongue or cheek. The lesion cannot be wiped off, unlike oral thrush. Most cases are seen in people over the age of 40; it is more common in men. Suspected cases require referral.

Squamous cell carcinoma: Squamous cell carcinoma is covered in more detail on page 137 and the reader is referred to this section for differential diagnosis of these from oral thrush.

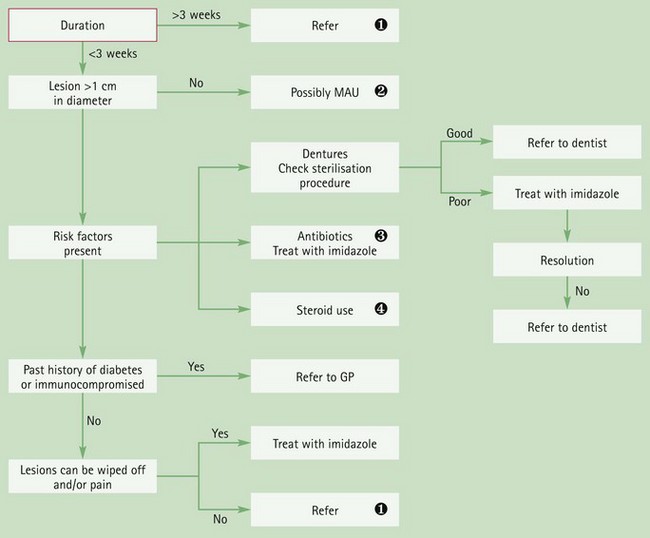

Figure 6.9 will aid the differentiation of thrush from other oral lesions.

Fig. 6.9 Primer for differential diagnosis of oral thrush.![]() Duration

Duration

Any lesion lasting more than 3 weeks must be referred to exclude sinister pathology.![]() MAU

MAU

See Figure 6.6 for primer for differential diagnosis of mouth ulcers.![]() Antibiotics

Antibiotics

Broad-spectrum antibiotics, e.g. amoxicillin and macrolides, can precipitate oral thrush by altering normal flora of the oral cavity.![]() Inhaled corticosteroids

Inhaled corticosteroids

High-dose inhaled corticosteroids can cause oral thrush. Patients should be encouraged to use a spacer and wash their mouth out after inhaler use to minimise this problem.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Only Daktarin oral gel (miconazole) is available OTC to treat oral thrush. It has proven efficacy and appears to have clinical cure rates between 80 and 90%. In comparative trials, Daktarin appears to have superior cure rates than the POM Nystatin.

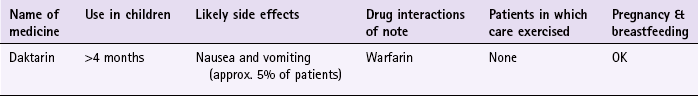

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to Daktarin Oral gel reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 6.6; useful tips relating to the application of Daktarin are given in Hints and Tips Box 6.2.

The dose of gel varies dependent on the age of patient. For adults and children over 6 years, the gel should be applied four times a day and those under six the dose is twice a day. The gel should be applied directly to the area with a clean finger. In May 2008 Jansen-Cilag, the manufacturers of Daktarin, chose to vary the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) to recommend that it is not used in infants under 4 months and only with care below the age of 6 months. This change appears to originate from a published report (De Vries et al 2006) documenting a 17-day-old baby who choked when exposed to miconazole oral gel.

It can occasionally cause nausea and vomiting. The manufacturers state that it can interact with a number of medicines, namely mizolastine, cisapride, triazolam, midazolam, quinidine, pimozide, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and anticoagulants. However, there is a lack of published data to determine how clinically significant these interactions are except with warfarin. Co-administration of warfarin with miconazole increases warfarin levels markedly and the patient’s (internationalised normalised ratio) INR should be monitored closely. The manufacturers advise that Daktarin should be avoided in pregnancy but published data does not support an association between miconazole and congenital defects. It appears to be safe to use whilst breastfeeding.

Hoppe, JE, Hahn, H. Randomized comparison of two nystatin oral gels with miconazole oral gel for treatment of oral thrush in infants. Antimycotics Study Group. Infection. 1996;24:136–139.

Hoppe, JE. Treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in immunocompetent infants: a randomized multicenter study of miconazole gel vs. nystatin suspension. The Antifungals Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:288–293.

Parvinen, T, Kokko, J, Yli-Urpo, A. Miconazole lacquer compared with gel in treatment of denture stomatitis. Scand J Dent Res. 1994;102:361–366.

Gingivitis

Background

Gingivitis simply means inflammation of the gums and is usually caused by an excess build-up of plaque on the teeth. The condition is entirely preventable if regular tooth brushing is undertaken.

Prevalence and epidemiology

It is estimated 50% of the UK population are affected by gum disease and that more than 85% of people over 40 will experience gingival disease. Men more than women tend to suffer from severe gingivitis.

Aetiology

Following tooth brushing, the teeth soon become coated in a mixture of saliva and gingival fluid, known as pellicle. Oral bacteria and food particles adhere to this coating and begin to proliferate forming plaque; subsequent brushing of the teeth removes this plaque build up. However, if plaque is allowed to build up for 3 or 4 days, bacteria begin to undergo internal calcification producing calcium phosphate better known as tartar (or calculus). This adheres tightly to the surface of the tooth and retains bacteria in situ. The bacteria release enzymes and toxins that invade the gingival mucosa, causing inflammation of the gingiva (gingivitis). If the plaque is not removed the inflammation travels downwards, involving the periodontal ligament and associated tooth structures (periodontitis). A pocket forms between the tooth and gum and, over a period of years, the root of the tooth and bone are eroded until such time that the tooth becomes loose and lost. This is the main cause of tooth loss in people over 40 years of age.

A number of risk factors are associated with gingivitis and periodontitis; these include diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, poor nutritional status and poor oral hygiene.

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Gingivitis often goes unnoticed because symptoms can be very mild and painless. This often explains why a routine check-up at the dentist reveals more severe gum disease than patients thought they had. A dental history needs to be taken from the patient, in particular details of their tooth brushing routine and technique, as well as the frequency of visits to their dentist. The mouth should be inspected for tell-tale signs of gingival inflammation. A number of gingivitis-specific questions should always be asked of the patient to aid in diagnosis (Table 6.7).

![]() Table 6.7

Table 6.7

Specific questions to ask the patient: Gingivitis

| Question | Relevance |

| Tooth brushing technique | Overzealous tooth brushing can lead to bleeding gums and gum recession. Make sure the patient is not ‘over cleaning’ their teeth. An electric tooth brush might be helpful for people who apply too much force when brushing teeth |

| Bleeding gums | Gums that bleed without exposure to trauma and is unexplained or unprovoked need referral to exclude underlying pathology |

Clinical features of gingivitis

Gingivitis is characterised by swelling and reddening of the gums, which bleed easily with slight trauma, for example when brushing teeth. Plaque might be visible; especially on teeth that are difficult to reach when tooth brushing. Halitosis might also be present.

Conditions to eliminate

If gingivitis is left untreated it will progress into periodontitis. Symptoms are similar to gingivitis but the patient will experience spontaneous bleeding, taste disturbances, halitosis and difficulty while eating. Periodontal pockets might be visible and the patient might complain of loose teeth. Referral to a dentist is needed for evaluation and removal of tartar.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Put simply, there is no substitute for good oral hygiene. Prevention of plaque build-up is the key to healthy gums and teeth. Twice daily brushing is recommended to maintain oral hygiene at adequate levels. Brushing teeth, with a fluoride toothpaste, to prevent tooth decay, should preferably take place after eating. Flossing is recommended, three times a week, to access areas that a toothbrush might miss. A Cochrane review (Robinson et al 2005) concluded that powered tooth brushes (with rotation oscillation action – where brush heads rotate in one direction and then the other) are more effective than manual brushing at plaque removal.

There is a plethora of oral hygiene products marketed to the public. These products should be reserved for established gingivitis or in those patients who have poor toothbrushing technique.

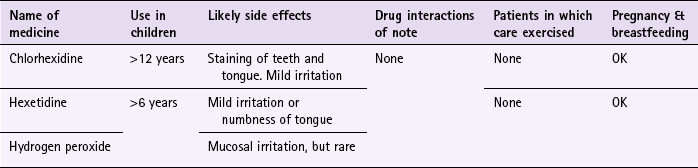

Mouthwashes contain chlorhexidine, hexetidine and hydrogen peroxide. Of these, chlorhexidine in concentrations of either 0.1 or 0.2% has been proven the most effective antibacterial in reducing plaque formation and gingivitis (Ernst et al 1998). In clinical trials it has been shown to be consistently more effective than placebo and comparator medicines, and there appears to be no difference in effect between concentrations. It has even been used as a positive control.

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to the medicines used for gingivitis reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 6.8; useful tips relating to products for oral care are given in Hints and Tips Box 6.3.

All mouthwashes, have minimal side effects and can be used by all patient groups. They are rinsed around the mouth between 30 seconds and 1 minute then spat out.

Chlorhexidine gluconate (e.g. Corsodyl 0.2%, Eludril 0.1%)

The standard dose for adults and children over 12 years old is 10 mL twice a day. Although it is free from side-effects, patients should be warned that prolonged use may stain the tongue and teeth brown. This can be reduced or removed by brushing teeth before use. If this fails to remove the staining then it can be removed by a dentist. Corsodyl is also available as a spray (0.2%) and gel (1%) and used twice a day.

References

Ernst, CP, Prockl, K, Willershausen, B. The effectiveness and side effects of 0.1% and 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthrinses: a clinical study. Quintessence Int. 1998;29:443–448.

Robinson, P, Deacon, SA, Deery, C, et al. Manual versus powered toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2005. [Art. No.: CD002281. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002281.pub2].

Brecx, M, Brownstone, E, MacDonald, L, et al. Efficacy of Listerine, Meridol and chlorhexidine mouthrinses as supplements to regular tooth cleaning measures. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:202–207.

Hase, JC, Ainamo, J, Etemadzadeh, H, et al. Plaque formation and gingivitis after mouthrinsing with 0.2% delmopinol hydrochloride, 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate and placebo for 4 weeks, following an initial professional tooth cleaning. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:533–539.

Jones, CM, Blinkhorn, AS, White, E. Hydrogen peroxide, the effect on plaque and gingivitis when used in an oral irrigator. Clin Prev Dent. 1990;12:15–18.

Kelly, M. Adult Dental Health Survey: Oral Health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: TSO; 2000.

Lang, NP, Hase, JC, Grassi, M, et al. Plaque formation and gingivitis after supervised mouthrinsing with 0.2% delmopinol hydrochloride, 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate and placebo for 6 months. Oral Dis. 1998;4:105–113.

Maruniak, J, Clark, WB, Walker, CB, et al. The effect of 3 mouthrinses on plaque and gingivitis development. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:19–23.

The British Dental Association. http://www.bda.org/

The British Fluoridation Society. http://www.bfsweb.org/

The British Dental Health Foundation. http://www.dentalhealth.org.uk/

The American Academy of Periodontology. http://www.perio.org/

Dyspepsia

Background

Confusion surrounds the terminology associated with upper abdominal symptoms and the term dyspepsia is used by different authors to mean different things. It is therefore an umbrella term generally used by healthcare professionals to refer to a group of upper abdominal symptoms that arise from five main conditions:

• non-ulcer dyspepsia/functional dyspepsia (indigestion)

These five conditions represent 90% of dyspepsia cases presented to the GP.

In August 2004, The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued clinical guidance on the management of dyspepsia in adults in primary care (see web sites at end of section). This guidance has specific information on pharmacist management of dyspepsia. This is still current (July 2012) and specific reference is made to this guidance.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The exact prevalence of dyspepsia is unknown. This is largely because of the number of people who self-medicate or do not report mild symptoms to their GP. However, it is clear that dyspepsia is extremely common. Between 25 and 40% of the general population in Western society are reported to suffer from dyspepsia and virtually everyone at some point in their lives will experience an episode. Estimates suggest that 10% of people suffer on a weekly basis and that 5% of all GP consultations are for dyspepsia. The prevalence of dyspepsia is modestly higher in women than men.

Aetiology

The aetiology of dyspepsia differs depending on its cause. Decreased muscle tone leads to lower oesophageal sphincter incompetence (often as a result of medicines or overeating) and is the principal cause of GORD. Increased acid production results in inflammation of the stomach (gastritis) and is usually attributable to Helicobacter pylori infection, or acute alcohol indigestion. The presence of H. pylori is central to duodenal and gastric ulceration – H. pylori is present in 95% of duodenal ulcers and 80% of gastric ulcers. The exact mechanism by which it causes ulceration is still unclear but the bacteria does produce toxins that stimulate the inflammatory cascade. Increasingly common are medicine induced ulcers, most notably NSAIDs and low-dose aspirin.

Finally, when no specific cause can be found for a patient’s symptoms the complaint is said to be non-ulcer dyspepsia. (Some authorities do not advocate the use of this term, preferring the term ‘functional dyspepsia’.)

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Overwhelmingly, patients who present with dyspepsia are likely to be suffering from GORD, gastritis or non-ulcer dyspepsia (Table 6.9). Research has shown that even those patients who meet NICE guidelines for endoscopical investigation are found to have either gastritis/hiatus hernia (30%), oesophagitis (10–17%) or no abnormal findings (30%). It has also been reported that a medical practitioner with an average list size will only see one new case of oesophageal cancer and one new case of stomach cancer every four years. Despite these statistics, a thorough medical and drug history should be taken to enable the community pharmacist to rule out serious pathology. ALARM symptoms (see Trigger points for referral), which would warrant further investigation are surprisingly common and it is important that patients exhibiting these symptoms are referred. A number of dyspepsia specific questions should always be asked of the patient to aid in diagnosis (Table 6.10).

Table 6.9

Causes of upper GI symptoms and their relative incidence in community pharmacy

| Incidence | Cause |

| Most likely | Non-ulcer dyspepsia |

| Unlikely | Medicine induced, peptic ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome |

| Very unlikely | Gastric and oesophageal cancers, atypical angina |

![]() Table 6.10

Table 6.10

Specific questions to ask the patient: Dyspepsia

| Question | Relevance |

| Age | The incidence of dyspepsia decreases with advancing age and therefore young adults are likely to suffer from dyspepsia with no specific pathologic condition, unlike patients over 50 years of age, in which a specific pathologic condition becomes more common |

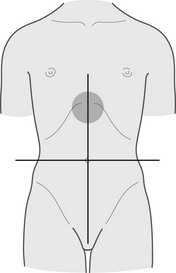

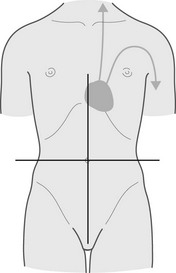

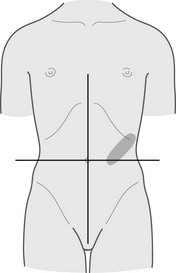

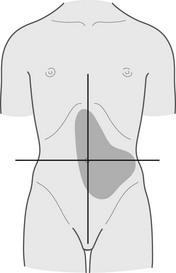

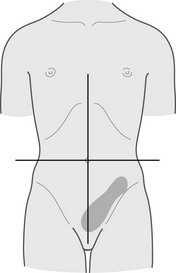

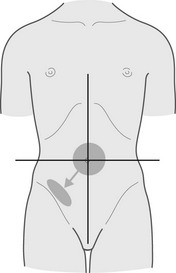

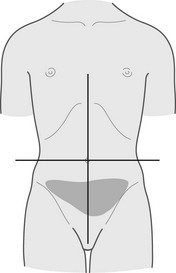

| Location | Dyspepsia is experienced as pain above the umbilicus and centrally located (epigastric area). Pain below the umbilicus will not be due to dyspepsia Pain experienced behind the sternum (breastbone) is likely to be heartburn If the patient can point to a specific area of the abdomen then it is unlikely to be dyspepsia |

| Nature of pain | Pain associated with dyspepsia is described as aching or discomfort. Pain described as gnawing, sharp or stabbing is unlikely to be dyspepsia |

| Radiation | Pain that radiates to other areas of the body is indicative of more serious pathology and the patient must be referred. The pain might be cardiovascular in origin, especially if the pain is felt down the inside aspect of the left arm |

| Severity | Pain described as debilitating or severe must be referred to exclude more serious conditions |

| Associated symptoms | Persistent vomiting with or without blood is suggestive of ulceration or even cancer and must be referred Black and tarry stools indicate a bleed in the GI tract and must be referred |

| Aggravating or relieving factors | Pain shortly after eating (1 to 3 hours) and relieved by food or antacids are classic symptoms of ulcers Symptoms of dyspepsia are often brought on by certain types of food, for example caffeine containing products and spicy food |

| Social history | Bouts of excessive drinking are commonly implicated in dyspepsia. Likewise, eating food on the move or too quickly is often the cause of the symptoms. A person’s job is often a good clue to whether these are contributing to their symptoms |

Clinical features of dyspepsia

Patients with dyspepsia present with a range of symptoms commonly involving:

Although, dyspeptic symptoms are a poor predictor of disease severity or underlying pathology, retrosternal heartburn is the classic symptom of GORD.

Conditions to eliminate

Peptic ulceration: Ruling out peptic ulceration is probably the main consideration for community pharmacists when assessing patients with symptoms of dyspepsia. Ulcers are classed as either gastric or duodenal. They occur most commonly in patients aged between 30 and 50, although patients over the age of 60 account for 80% of deaths even though they only account for 15% of cases. Typically the patient will have well localised mid-epigastric pain described as ‘constant’, ‘annoying’ or ‘gnawing/boring’. In gastric ulcers the pain comes on whenever the stomach is empty, usually 30 minutes after eating and is generally relieved by antacids or food and aggravated by alcohol and caffeine. Gastric ulcers are also more commonly associated with weight loss and GI bleeds than duodenal ulcers. Patients can experience weight loss of 5 to 10 kg and although this could indicate carcinoma, especially in people aged over 40, on investigation a benign gastric ulcer is found most of the time. NSAID use is associated with a three- to fourfold increase in gastric ulcers.

Duodenal ulcers tend to be more consistent in symptom presentation. Pain occurs 2 to 3 hours after eating and pain that wakes a person at night is highly suggestive of duodenal ulcer. If ulcers are suspected referral to the GP is necessary as peptic ulcers can only be conclusively diagnosed by endoscopy.

Medicine-induced dyspepsia: A number of medicines can cause gastric irritation leading to or provoking GI discomfort or they can decrease oesophageal sphincter tone resulting in reflux. Aspirin and NSAIDs are very often associated with dyspepsia and can affect up to 25% of patients. Table 6.11 lists other medicines commonly implicated in causing dyspepsia.

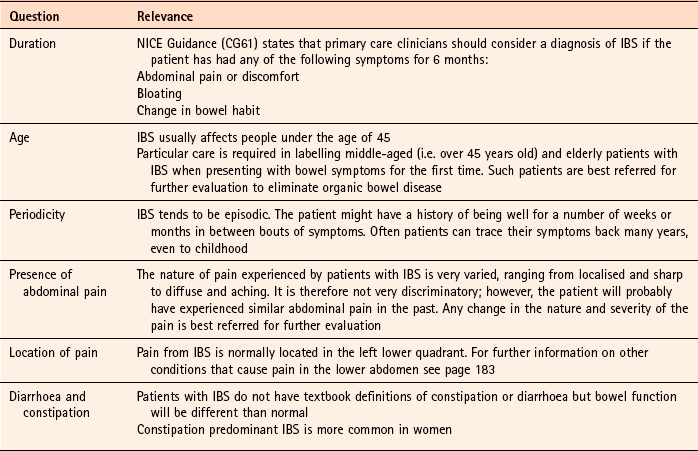

Irritable bowel syndrome: Patients younger than 45, who have uncomplicated dyspepsia and also lower abdominal pain and altered bowel habits are likely to have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). For further details on IBS see page 168.

Very unlikely causes

Gastric carcinoma: Gastric carcinoma is the third most common GI malignancy after colorectal and pancreatic cancer. However, only 2% of patients who are referred by their GP for an endoscopy have malignancy. It is therefore a rare condition and community pharmacists are extremely unlikely to encounter a patient with carcinoma. One or more ALARM symptoms should be present plus symptoms such as nausea and vomiting.

Oesophageal carcinoma: In its early stages, oesophageal carcinoma might go unnoticed. Over time, however, as the oesophagus becomes constricted, patients will complain of difficulty in swallowing and experience a sensation of food sticking in the oesophagus. As the disease progresses weight loss becomes prominent despite the patient maintaining a good appetite.

Atypical angina: Not all cases of angina have classical textbook presentation of pain in the retrosternal area with radiation to the neck, back or left shoulder that is precipitated by temperature changes or exercise. Patients can complain of dyspepsia-like symptoms and feel generally unwell. These symptoms might be brought on by a heavy meal. In such cases antacids will fail to relieve symptoms and referral is needed.

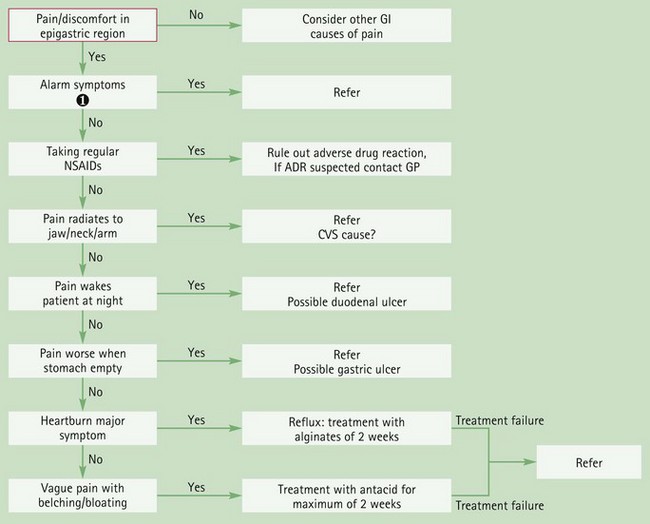

Figure 6.10 will aid differentiation of the causes of dyspepsia.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

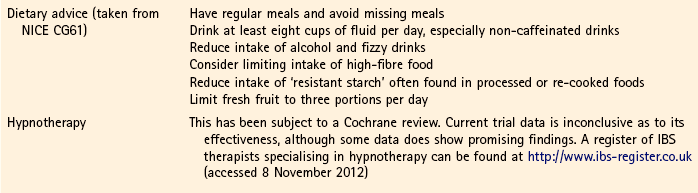

In accordance with NICE guidelines the group of patients that should be treated by pharmacists are classed as having ‘uninvestigated dyspepsia’ (i.e. those that have not had endoscopical investigation). OTC treatment options consist of antacids, H2 antagonists and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Before treatment is instigated lifestyle advice should be given where appropriate. Although there is no strong evidence that dietary changes will lessen dyspepsia symptoms, a general healthier lifestyle will have wider health benefits. The patient should be assessed in terms of diet and physical activity:

It might also be possible to identify factors that precipitate or worsen symptoms. Commonly implicated foods that precipitate dyspepsia are spicy or fatty food, caffeine, chocolate and alcohol. Bending is also said to worsen symptoms.

Antacids

Antacids have been used for many decades to treat dyspepsia and have proven efficacy in neutralising stomach acid. However, the neutralising capacity of each antacid varies dependent on the metal salt used. In addition, the solubility of each metal salt differs, which affects their onset and duration of action. Sodium and potassium salts are the most highly soluble, which makes them quick but short acting. Magnesium and aluminium salts are less soluble so have a slower onset but greater duration of action. Calcium salts have the advantage of being quick acting yet have a prolonged action.

It is therefore commonplace for manufacturers to combine two or more antacid ingredients together to ensure a quick onset (generally sodium salts e.g. sodium bicarbonate) and prolonged action (aluminium, magnesium or calcium salts).

Alginates

For patients suffering from GORD an alginate product should be first-line treatment. When in contact with gastric acid the alginate precipitates out, forming a sponge-like matrix that floats on top of the stomach contents. Alginate preparations are also commonly combined with antacids to help neutralise stomach acid. In clinical trials alginate-containing products have demonstrated superior symptom control compared to placebo and antacids. However, PPIs and H2 antagonists do have superior efficacy to alginates.

H2 antagonists

Two H2 antagonists are currently available OTC in the UK; ranitidine and famotidine. Cimetidine was also available OTC but withdrawn by the manufacturer and nizatidine has exemption from POM control but currently there is no marketed product.

H2 antagonists are effective at POM doses but OTC licensed indications use lower doses. The question is, at these lower doses are they still effective? There is a paucity of publicly available trial data supporting their use at non-prescription doses. Famotidine appears to have the greatest body of accessible trial data. A number of trials have been conducted in patients suffering from heartburn and who regularly self-medicate with antacids. Famotidine was shown to be more effective than placebo and equally effective to antacids. No trials involving ranitidine could be found on public databases that involved patients taking OTC doses.

However, the inhibitory effects of OTC doses of ranitidine on gastric acid have been investigated in healthy volunteers. Trials showed conclusively that ranitidine, and its comparator drug famotidine, did significantly raise intragastric pH compared to placebo, although antacids (calcium carbonates) had a significantly quicker onset of action but with shorter duration.

Proton pump inhibitors

A number of trials have compared PPIs with H2 antagonists for non-ulcer dyspepsia and GORD-like symptoms (Moayyedi et al 2006; Talley et al 2002; van Pinxteren 2006). Results indicate that PPIs, even at half the standard POM dose, are generally superior to H2 antagonists in treating dyspeptic symptoms.

Summary

Antacids will work for the majority of people presenting at the pharmacy with mild dyspeptic symptoms. They can be used as first-line therapy unless heartburn predominates then an alginate or alginate/antacid combination can be used. H2 antagonists appear to be equally effective to antacids but are considerably more expensive. Proton pump inhibitors are the most effective and could be considered first-line, especially for those patients that suffer from moderate to severe or recurrent symptoms. Like H2 antagonists they are expensive in comparison to simple antacids and might influence patient choice or pharmacist recommendation.

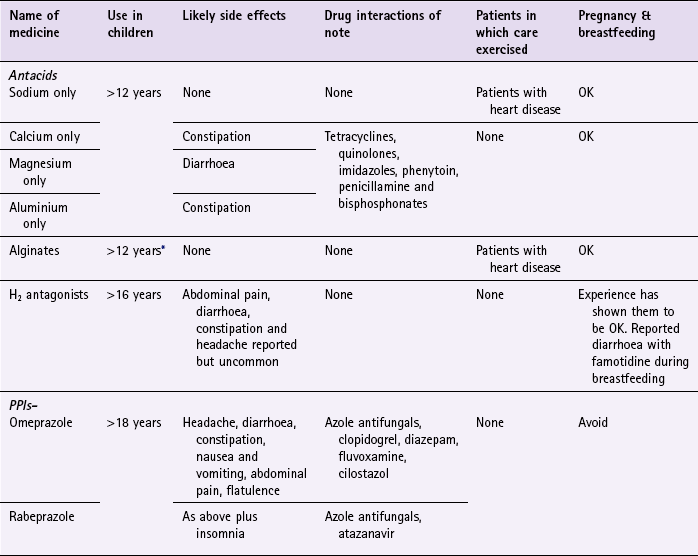

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to the medicines used for dyspepsia reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication is discussed and summarised in Table 6.12.

![]() Table 6.12

Table 6.12

Practical prescribing: Summary of medicines for dyspepsia

*Certain products can be given to children but dyspepsia unusual in children and it might be prudent to refer such patients to their GP.

Antacids

The majority of marketed antacids are combination products containing two, three or even four constituents. The rationale for combining different salts together appears to be twofold. First, to ensure the product has quick onset (containing sodium or calcium) and a long duration of action (containing magnesium, aluminium or calcium). Second, to minimise any side effects that might be experienced from the product. For example, magnesium salts tend to cause diarrhoea and aluminium salts constipation, however, if both are combined in the same product then neither side effect is noticed. Useful tips relating to antacids are given in Hints and Tips Box 6.4.

Antacids can affect the absorption of a number of medications via chelation and adsorption. Commonly affected medicines include tetracyclines, quinolones, imidazoles, phenytoin, penicillamine and bisphosphonates. In addition, the absorption of enteric-coated preparations can be affected due to antacids increasing the stomach pH. The majority of these interactions are easily overcome by leaving a minimum gap of 1 hour between the respective doses of each medicine.

Most patient groups can take antacids, although patients on salt-restricted diets (e.g. patients with coronary heart disease) should ideally avoid sodium-containing antacids. In addition, antacids should not be recommended in children because dyspepsia is unusual in children under 12. Indeed, most products are licensed for use only for children aged 12 and over. However, there are a few exceptions (e.g. Acidex, Topal), which have product licences for use in children.

Alginates (e.g. the Gaviscon range)

Products containing alginates are combination preparations that contain an alginate with antacids. They are best given after each main meal and before bedtime, although they can be taken on a when-needed basis. They can be given during pregnancy and breastfeeding and to most patient groups but, as with antacids, patients on salt-restricted diets should ideally avoid sodium-containing alginate preparations. They are reported not to have any side effects or interactions with other medicines.

H2 antagonists

Sales of H2 antagonists are restricted to adults and children over the age of 16. They possess no clinically important drug interactions and side effects are rare. Safety concerns were raised on deregulation of H2 antagonists about the potential to mask serious underlying conditions and the possibility of increased adverse reactions. These fears appear to have been unfounded as follow-up studies and post marketing surveillance has not shown any increase in risk associated with greater availability. Indeed, H2 antagonists are now available as general sales list medicines. They have been used in pregnancy and breastfeeding, with ranitidine having been used most. Data suggests that there are no significant increases in any major malformations in pregnancy and can be used whilst breastfeeding and manufacturers of OTC products advise patients to speak to the doctor or pharmacist before taking.

Famotidine (PepcidTwo): The dose for famotidine is 10 mg (one tablet) at the onset of symptoms; however, if symptoms persist an additional dose can be repeated after 1 hour. The maximum dose is 20 mg (two tablets) in 24 hours. A dose can be taken 1 hour prior to consuming food or drink that are known to bring on symptoms. PepcidTwo is a combination of famotidine, calcium carbonate and magnesium hydroxide. The antacid component of the product provides quick onset of action helping to relieve symptoms before famotidine exerts its action, which can take 2 hours.

Ranitidine (e.g. Zantac range, Gavilast and Gavilast P, Ranzac): Dosing for ranitidine (Zantac 75) is similar to famotidine in that one tablet should be taken straight away but if symptoms persist then a further tablet should be taken 1 hour later. The maximum dose is 300 mg (four tablets) in 24 hours. The General Sales List versions of ranitidine (Zantac 75 Relief and Ranzac), have slightly different license in that they cannot be used for prevention of heartburn and the maximum dose is only two tablets in 24 hours.

Omeprazole (Zanprol): Zanprol is licensed for the relief of reflux-like symptoms (e.g. heartburn) associated with acid-related dyspepsia in patients aged over 18 years of age. The initial dose is two 10 mg tablets once daily. Once symptoms improve the dose can be reduced to one tablet (10 mg). If symptoms return then the dose can be stepped back up to 20 mg. Patients should be referred to their GP if symptoms do not resolve in 2 weeks or they need to use omeprazole for more than 4 weeks continuously. Omeprazole can cause a number of common side effects (>1 in 100), which include headache, diarrhoea, constipation, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting and flatulence. Drug interactions with omeprazole are possible because it is metabolised in the liver by cytochrome P450 isoenzymes. These include ‘azole’ antifungals (decrease in azole bioavailability), diazepam (enhanced diazepam side effects), fluvoxamine (increased omeprazole levels), cilostazol (increased cilostazol levels – and UK manufacturers advise against co-administration) and clopidogrel (reduced clopidogrel levels). Other interactions listed in the manufacturer’s literature include phenytoin and warfarin but their clinical significance appears low.

It appears to be safe in pregnancy and excreted in only small amounts of breast milk and is not contraindicated when used as a POM medicine, however for pharmacy use it is not recommended.

Rabeprazole (Pariet Pharmacy): The MHRA have recently approved the deregulation of rabeprazole from POM to P. Its product license is very similar to that of omeprazole: it has a license for the short-term symptomatic treatment of GORD-like symptoms (e.g. heartburn) in adults aged 18 and over; if symptoms have not been controlled within 2 weeks or if continuous treatment for more than 4 weeks is required, then the patient should be referred to their doctor; and it should be avoided in pregnant and breastfeeding women. The dose is one 10 mg tablet each day. Side effects commonly seen include insomnia, headaches, dizziness, cough, diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, abdominal pain and constipation. It interacts with oral ‘azole’ medicines and on theoretical grounds should not be co-administered with atazanavir.

References

Moayyedi, P, Soo, S, Deeks, J, et al. Pharmacological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2006. [Art. No.: CD001960. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001960.pub3.].

Talley, NJ, Moore, MG, Sprogis, A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of pantoprazole versus ranitidine for the treatment of uninvestigated heartburn in primary care. Med J Aust. 2002;177(8):423–427.

van Pinxteren, B, Sigterman, KE, Bonis, P, Lau, J, et al. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2006. [Art. No.: CD002095. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002095.pub3].

Castell, DO, Dalton, CB, Becker, D, et al. Alginic acid decreases postprandial upright gastroesophageal reflux. Comparison with equal-strength antacid. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:589–593.

Dowswell, T, Neilson, JP. Interventions for heartburn in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2008. Art. No.: CD007065. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007065.pub2

Drake, D, Hollander, D. Neutralizing capacity and cost effectiveness of antacids. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:215–217.

Feldman, M. Comparison of the effects of over-the-counter famotidine and calcium carbonate antacid on postprandial gastric acid. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275:1428–1431.

Halter, F. Determination of neutralization capacity of antacids in gastric juice. Z Gastroenterol. 1983;21:S33–S40.

Netzer, P, Brabetz-Hofliger, A, Brundler, R, et al. Comparison of the effect of the antacid Rennie versus low dose H2 receptor antagonists (ranitidine, famotidine) on intragastric acidity. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:337–342.

Reilly, TG, Singh, S, Cottrell, J, et al. Low dose famotidine and rantidine as single post-prandial doses: a three-period placebo-controlled comparative trial. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:749–755.

Smart, HL, Atkinson, M. Comparison of a dimethicone/antacid (Asilone gel) with an alginate/antacid (Gaviscon liquid) in the management of reflux oesophagitis. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:554–556.

NICE Guidance on management of dyspepsia in primary care. http://publications.nice.org.uk/dyspepsia-cg17.

British Society of Gastroenterology. http://www.bsg.org.uk/

CORE. research charity. http://www.corecharity.org.uk/.

American Gastroenterological Association. http://www.gastro.org/

Diarrhoea

Background

Diarrhoea can be defined as an increase in frequency of the passage of soft or watery stools relative to the usual bowel habit for that individual. It is not a disease but a sign of an underlying problem such as an infection or gastrointestinal disorder. It can be classed as acute (less than 7 days), persistent (more than 14 days) or chronic (lasting longer than a month). Most patients will present to the pharmacy with a self-diagnosis of acute diarrhoea. It is necessary to confirm this self-diagnosis because patients’ interpretations of their symptoms might not match up with the medical definition of diarrhoea.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The exact prevalence and epidemiology of diarrhoea is not well known. This is probably due to the number of patients who do not seek care or who self-medicate. However, acute diarrhoea does generate high GP consultation rates. It has been reported that children under the age of 5 years have between one and three bouts of diarrhoea per year and adults, on average, just under one episode of diarrhoea per year. Many of these cases are thought to be food related.

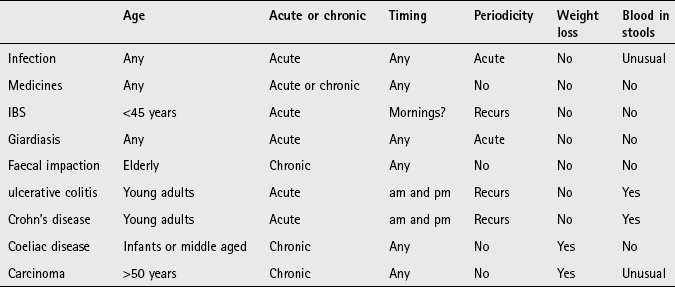

Aetiology

The aetiology of diarrhoea depends on its cause. Acute gastroenteritis, the most common cause of diarrhoea in all age groups, is usually viral in origin. In the UK rotavirus and small round structured virus (SRSV) are the most common identified causes of gastroenteritis in children, and in adults, Campylobacter followed by rotavirus are the most common. Other pathogens identified include Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella; viruses such as adenovirus; and the protozoa Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Viral causes tend to cause diarrhoea by blunting of the villi of the upper small intestine decreasing the absorptive surface. Bacterial causes of diarrhoea are normally a result of eating contaminated food or drink and cause diarrhoea by a number of mechanisms. For example, enterotoxigenic E. coli produce enterotoxins that affect gut function with secretion and loss of fluids; enteropathogenic E. coli interferes with normal mucosal function; and enteroinvasive E. coli, Shigella and Salmonella species cause injury to the mucosa of the small intestine and deeper tissues.

Other organisms, for example Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus, produce preformed enterotoxins which on ingestion stimulate the active secretion of electrolytes into the intestinal lumen.

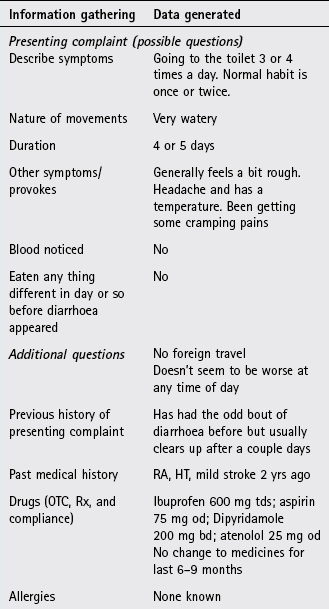

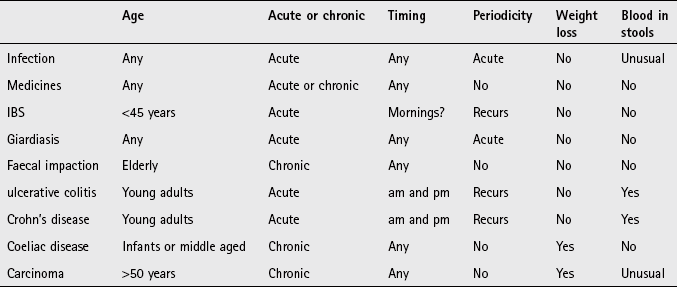

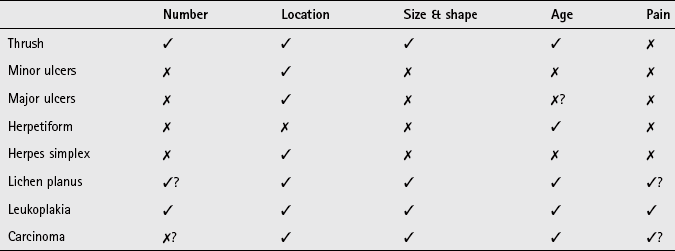

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

The most common causes of diarrhoea are viral or bacterial infection (Table 6.13) and the community pharmacist can appropriately manage the vast majority of cases. The main priority is identifying those patients that need referral and how quickly they need to be referred. Dehydration is the main complicating factor, especially in the very young (see page 297) and very old. A number of diarrhoea specific questions should always be asked of the patient to aid in diagnosis (Table 6.14).

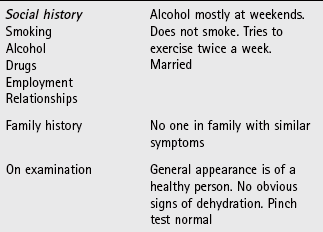

Table 6.13

Causes of diarrhoea and their relative incidence in community pharmacy

| Incidence | Cause |

| Most likely | Viral and bacterial infection |

| Likely | Medicine induced |

| Unlikely | Irritable bowel syndrome, giardiasis, faecal impaction |

| Very unlikely | Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, colorectal cancer, malabsorption syndromes |

![]() Table 6.14

Table 6.14

Specific questions to ask the patient: Diarrhoea

| Question | Relevance |

| Frequency and nature of the stools | Patients with acute self-limiting diarrhoea will be passing watery stools more frequently than normal Diarrhoea associated with blood and mucus (dysentery) requires referral to eliminate invasive infection such as Shigella, Campylobacter, Salmonella or E. coli O157 Bloody stools is also associated with conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease |

| Periodicity | A history of recurrent diarrhoea of no known cause should be referred for further investigation |

| Duration | A person who presents with a history of chronic diarrhoea should be referred. The most frequent causes of chronic diarrhoea are IBS, inflammatory disease and colon cancer |

| Onset of symptoms | Ingestion of bacterial pathogens can give rise to symptoms in a matter of a few hours (toxin producing bacteria) after eating contaminated food or up to 3 days later. It is therefore important to ask about food consumption over the last few days, establish if anyone else ate the same food and to check the status of his or her health |

| Timing of diarrhoea | Patients who experience diarrhoea first thing in the morning might well have underlying pathology such as IBS Nocturnal diarrhoea is often associated with inflammatory bowel disease |

| Recent change of diet | Changes in diet can cause changes to bowel function, for example when away on holiday. If the person has recently been to a non-Western country then giardiasis is a possibility |

| Signs of dehydration | Mild (<5%) dehydration can be vague but include tiredness, anorexia, nausea and light-headedness Moderate (5 to 10%) dehydration is characterised by dry mouth, sunken eyes, decreased urine output, moderate thirst and decreased skin turgor (pinch test of 1 to 2 seconds or longer) |

Clinical features of acute diarrhoea

Symptoms are normally rapid in onset, with the patient having a history of prior good health. Nausea and vomiting might be present prior to or during the bout of acute diarrhoea. Abdominal cramping, flatulence and tenderness is also often present. If rotavirus is the cause the patient might also experience viral prodromal symptoms such as cough and cold. Acute infective diarrhoea is usually watery in nature with no blood present. Complete resolution of symptoms should be observed in 2 to 4 days. However, diarrhoea caused by the rotavirus can persist for longer.

Conditions to eliminate

Medicine-induced diarrhoea: Many medicines (both POM and OTC) can induce diarrhoea (Table 6.15). If medication is suspected as the cause of the diarrhoea the GP should be contacted and an alternative suggested.

![]() Table 6.15

Table 6.15

Examples of medicines known to cause diarrhoea (defined as very common [>10%] or common [1–10%])

| α-blocker | Prazosin |

| ACE inhibitor | Lisinopril, perindopril |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | Telmisartan |

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor | Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine |

| Antacid | Magnesium salts |

| Antibacterial | All |

| Antidiabetic | Metformin, acarbose |

| Antidepressant | SSRIs, clomipramine, venlafaxine |

| Anti-emetic | Aprepitant, dolasetron |

| Anti-epileptic | Carbamazepine, oxcarbamazepine, tiagabine, zonisamide, pregabalin, levetiracetam |

| Antifungal | Caspofungin, fluconazole, flucytosine, nystatin (in large doses), terbinafine, voriconazole |

| Antimalarial | Mefloquine |

| Antiprotozoal | Metronidazole, sodium stibogluconate |

| Antipsychotic | Aripiprazole |

| Antiviral | Abacavir, emtricitabine, stavudine, tenofovir, zalcitabine, zidovudine, amprenavir, atazanavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, saquinavir, efavirenz, ganciclovir, valganciclovir, adefovir, oseltamivir, ribavirin, fosamprenavir |

| Beta-blocker | Bisoprolol, carvedilol, nebivolol |

| Bisphosphonate | Alendronic acid, disodium etidronate, ibandronic acid, risedronate, sodium clodronate, disodium pamidronate, tiludronic acid |

| Cytokine inhibitor | Adalimumab, infliximab |

| Cytotoxic | All classes of cytotoxics |

| Dopaminergic | Levodopa, entacapone |

| Growth hormone antagonist | Pegvisomant |

| Immunosuppressant | Ciclosporin, mycophenolate, leflunomide |

| NSAID | All |

| Ulcer healing | Proton pump inhibitors |

| Vaccines | Pediacel (5 vaccines in 1), haemophilus, meningococcal |

| Miscellaneous | Calcitonin, strontium ranelate, colchicines, dantrolene, olsalazine, anagrelide, nicotinic acid, pancreatin, eplerenone, acamprosate |

Reproduced with permission from R Walker and C Whittlesea, Clinical pharmacy and therapeutics, 5th edition, 2011, Churchill Livingstone.

Unlikely causes

Irritable bowel syndrome: Patients younger than 45 with lower abdominal pain and a history of alternating diarrhoea and constipation are likely to have IBS. For further details on IBS see page 168.

Giardiasis: Giardiasis, a protozoan infection of the small intestine, is contracted through drinking contaminated drinking water. It is an uncommon cause of diarrhoea in Western society. However, with more people taking exotic foreign holidays, enquiry about recent travel should be made. The patient will present with watery and foul-smelling diarrhoea accompanied with symptoms of bloating, flatulence and epigastric pain. If giardiasis is suspected the patient must be referred to the GP quickly for confirmation and appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Faecal impaction: Faecal impaction is most commonly seen in the elderly and those with poor mobility. Patients might present with continuous soiling as a result of liquid passing around hard stools and mistakenly believe they have diarrhoea. On questioning, the patient might describe the passage of regular poorly formed hard stools that are difficult to pass. Referral is needed as manual removal of the faeces is often needed.

Very unlikely causes

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: Both conditions are characterised by chronic inflammation at various sites in the GI tract and follow periods of remission and relapse. They can affect any age group, although peak incidence is between 20 and 30 years of age. In mild cases of both conditions, diarrhoea is one of the major presenting symptoms, although blood in the stool is usually present. Patients might also find that they have urgency, nocturnal diarrhoea and early morning rushes. In the acute phase patients will appear unwell and have malaise.

Malabsorption syndromes: Lactose intolerance is often diagnosed in infants under 1 year old. In addition to more frequent loose bowel movements symptoms such as fever, vomiting, perianal excoriation and a failure to gain weight might occur.

Coeliac disease has a bimodal incidence: first, in early infancy when cereals become a major constituent of the diet, and second, during the fourth and fifth decades. Steatorrhoea (fatty stools) is common and might be observed by the patient as frothy or floating stools in the toilet pan. Bloating and weight loss in the presence of a normal appetite might also be observed.

Colorectal cancer: Any middle-aged patient presenting with a longstanding change of bowel habit must be viewed with suspicion. Persistent diarrhoea accompanied by a feeling that the bowel has not really been emptied is suggestive of neoplasm. This is especially true if weight loss is also present.

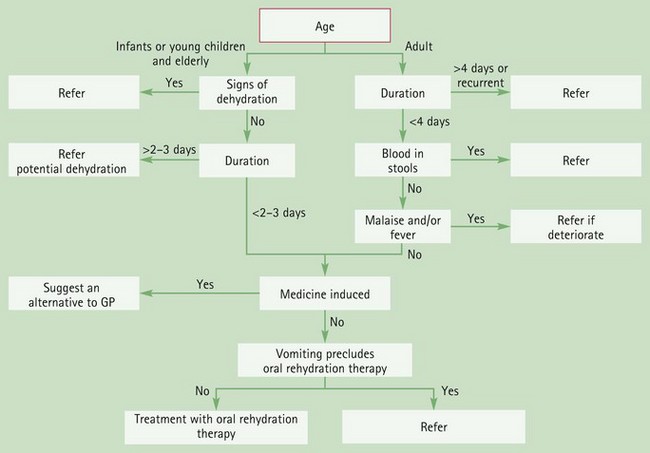

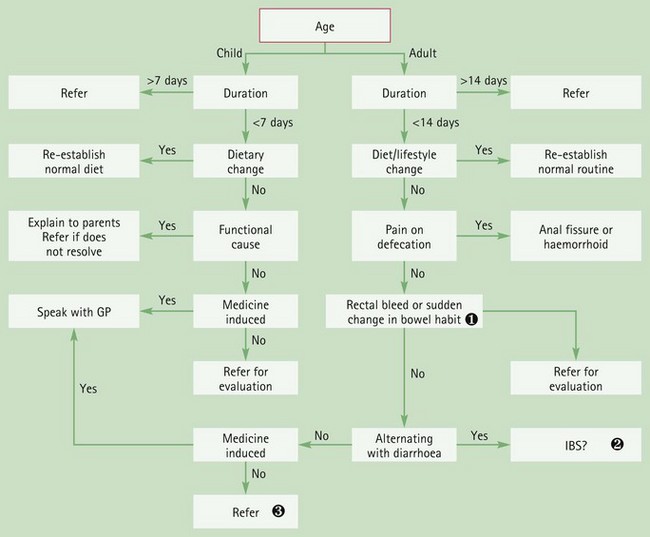

Figure 6.11 will aid differentiation of diarrhoeal cases that require referral.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Acute infectious diarrhoea still remains one of the leading causes of death in developing countries, despite advances in its treatment. In developed and Western countries diarrhoeal disease is primarily of economic and socially disruptive significance. Goals of OTC treatment in the UK are therefore concentrated on relief of symptoms.

Before considering treatment it is important to stress to patients the importance of hand washing. Interventions that promote hand washing can reduce diarrhoea episodes by about one-third.

Oral rehydration solution (ORS)

ORS represents one of the major advances in medicine. It has proved to be a simple highly effective treatment, which has decreased mortality and morbidity associated with acute diarrhoea in developing countries. The formula recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) contains glucose (75 mmol/L), sodium (75 mmol/L), potassium (20 mmol/L), chloride (65 mmol/L) and citrate (10 mmol/L) in an almost isotonic fluid. Until recently, the WHO oral rehydration solution contained 90 mmol/L sodium but a systematic review (Hahn et al 2002) concluded that ORS with a reduced osmolarity compared to the standard WHO formula were associated with fewer complications in children with mild to moderate diarrhoea. Based on this, and other findings, the WHO oral rehydration solution now has a reduced osmolarity of 245 mm/L, which contains 75 mmol of sodium. A number of similar preparations are available commercially in the form of sachets that require reconstitution in clean water before use; however, commercially available solutions in the UK contain lower sodium concentrations as diarrhoea tends to be isotonic, and therefore replacement of large quantities of sodium is less important.

Rice-based ORS

In many developing countries a glucose substitute was added to electrolytes because of glucose unavailability. These products were found to be quite successful. Clinical trials have subsequently shown rice-based ORS to be highly efficacious, well tolerated and potentially more effective than conventional ORS.

Loperamide

Loperamide is a synthetic opioid analogue and is thought to exert its action via opiate receptors slowing intestinal tract time and increasing the capacity of the gut. It has been extensively researched, with many published trials investigating its effectiveness in acute infectious diarrhoea. The majority of well-designed double-blind placebo-controlled trials have consistently shown it to be significantly better than placebo and comparable to diphenoxylate. Loperamide is also available compounded with simeticone. However, there is little evidence of better efficacy in terms of diarrhoeal symptoms with the combination.

Bismuth subsalicylate

Bismuth-containing products have been used for many decades. Its use has declined over time as other products have become more popular. However, bismuth subsalicylate has been shown to be effective in treating traveller’s diarrhoea. A review paper by Steffen (1990) concluded that bismuth subsalicylate was clinically superior to placebo, decreasing the number of unformed stools and increasing the number of patients who were symptom free. However, two of the trials reviewed showed bismuth subsalicylate to be significantly slower in symptom resolution than its comparator drug loperamide.

Kaolin and morphine

The constipating side effect of opioid analgesics can be used to treat diarrhoea. However, kaolin and morphine products have no evidence of efficacy and should not be recommended. It remains a popular home remedy, especially with the elderly.

Rotavirus vaccine

In 2006, two new oral vaccines (Rotarix, and RotaTeq) were licensed by the European Medicines Agency and the US Food and Drug Administration. Clinical trials have shown them to be effective (Soares-Weiser et al 2012).

From 2013, the rotavirus vaccine will be added to the routine UK childhood vaccination schedule.

Summary

Since diarrhoea results in fluid and electrolyte loss it is important to re-establish normal fluid balance and so ORS is first line treatment for all age groups, especially children and the frail elderly. Loperamide is a useful adjunct in reducing the number of bowel movements but should be reserved for those patients who will find it inconvenient to have to go to the toilet.

Practical prescribing and product selection

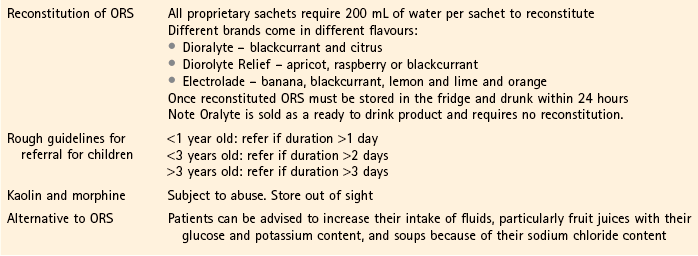

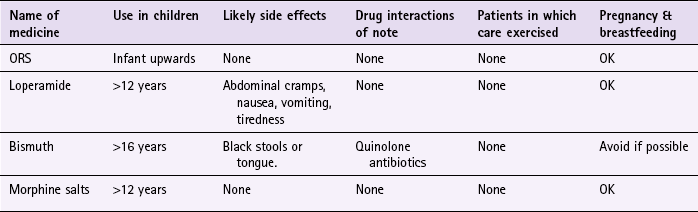

Prescribing information relating to the medicines used for diarrhoea reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 6.16; useful tips relating to patients presenting with diarrhoea are given in Hints and Tips Box 6.5.

ORS (Dioralyte, Dioralyte Relief (rice-based), Electrolade, Oralyte)

ORS can be given to all patient groups, has no side effects or drug interactions. The volume of solution given is dependent on how much fluid is lost. As infants and the elderly are more at risk of developing dehydration they should be encouraged to drink as much ORS as possible. In adults, 2 L of ORS should be given in the first 24 hours, followed by unrestricted normal fluids with 200 mL of rehydration solution per loose stool or vomit. The solution is best sipped every 5–10 min rather than drunk in large quantities less frequently. In infants, 1 to  times the usual feed volume should be given.

times the usual feed volume should be given.

Loperamide (e.g. Diocalm Ultra, Diah-Limit, Imodium range)

The dose is two capsules immediately, followed by one capsule after each further bout of diarrhoea. It has minimal CNS side effects, although CNS depressant effects and respiratory depression have been reported at high doses. OTC doses are therefore limited to 16 mg a day and cannot be used in children under 12. The excellent safety record of loperamide has seen it granted General Sales List status, although abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting, tiredness, drowsiness, dizziness and dry mouth have been reported. Loperamide is available in a range of formulations, such as dispersible tablets, melt-tabs and liquid.

Bismuth (Pepto-Bismol Liquid 87.6 mg/5 mL bismuth subsalicylate and Chewable tablet 262.5 mg)

Pepto-Bismol should only be given to people over the age of 16. The dose is 30 mL or two tablets taken every 30 min to 1 hour when needed, with a maximum of eight doses in 24 hours. Bismuth subsalicylate is well tolerated and has a favourable side-effect profile, although black stools are commonly observed (caused by unabsorbed bismuth compound). Occasional use is not known to cause problems during pregnancy and breastfeeding but the manufacturers state it should not be used. Bismuth can decrease the bioavailability of quinolone antibiotics therefore a minimum 2-hour gap should be left between doses of each medicine.

Morphine (e.g. Kaolin and morphine, Diocalm Dual Action)

Morphine is generally well tolerated at OTC doses, with no side effects reported. The products can be given to all patient groups, including pregnant and breastfeeding women. There are no drug interactions of note. Morphine is available as a non-proprietary product (Kaolin and morphine) and J Collis Browne’s products.

References

Soares-Weiser, K, MacLehose, H, Bergman, H, et al. Vaccines for preventing rotavirus diarrhoea: vaccines in use. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2012. [Art. No.: CD008521. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008521.pub2].

Steffen, R. Worldwide efficacy of bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:S80–S86.

American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] Committee on Quality Improvement SoAG. Practice Parameter. The management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. Pediatrics. 1996;97:4224–4433.

Amery, W, Duyck, F, Polak, J, et al. A multicentre double-blind study in acute diarrhoea comparing loperamide (R 18553) with two common antidiarrhoeal agents and a placebo. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1975;17:263–270.

Chassany, O, Michaux, A, Bergman, JF. Drug-induced diarrhoea. Drug Safety. 2000;22:53–72.

Cornett, JWD, Aspeling, RL, Mallegol, D. A double blind comparative evaluation of loperamide versus diphenoxylate with atropine in acute diarrhea. Curr Ther Res. 1977;21:629–637.

Ejemot-Nwadiaro, RI, Ehiri, JE, Meremikwu, MM, et al. Hand washing for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2008. Art. No.: CD004265. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004265.pub2

Gavin, N, Merrick, N, Davidson, B. Efficacy of glucose-based oral rehydration therapy. Pediatrics. 1996;98:45–51.

Hahn, S, Kim, Y, Garner, P. Reduced osmolarity oral rehydration solution for treating dehydration caused by acute diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2002. Art. No.: CD002847. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002847

Islam, A, Molla, AM, Ahmed, MA, et al. Is rice based oral rehydration therapy effective in young infants? Arch Dis Child. 1994;71:19–23.

Molla, AM, Sarker, SA, Hossain, M, et al. Rice-powder electrolyte solution as oral-therapy in diarrhoea due to Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli. Lancet. 1982;1(8285):1317–1319.

Nelemans, FA, Zelvelder, WG. A double-blind placebo controlled trial of loperamide (Imodium) in acute diarrhea. J Drug Res. 1976;2:54–59.

Patra, FC, Mahalanabis, D, Jalan, KN, et al. Is oral rice electrolyte solution superior to glucose electrolyte solution in infantile diarrhoea? Arch Dis Child. 1982;57:910–912.

Selby, W. Diarrhoea – differential diagnosis. Aust Fam Physician. 1990;19:1683–1686.

Soares-Weiser, K, Goldberg, E, Tamimi, G, et al. Rotavirus vaccine for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2004. Art. No.: CD002848. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002848.pub2

Steffen, R. Worldwide efficacy of bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:S80–S86.

National Association for Colitis and Crohn’s disease (NACC) – Crohn’s and Colitis UK. http://www.nacc.org.uk

Constipation

Background

Constipation, like diarrhoea, means different things to different people. Constipation arises when the patient experiences a reduction in their normal bowel habit accompanied with more difficult defecation and/or hard stools. In Western populations 90% of people defecate between three times a day and once every three days. However, many people still believe that anything other than one bowel movement a day is abnormal.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Constipation is very common. It occurs in all age groups but is especially common in the elderly. It has been estimated that 25 to 40% of all people over the age of 65 have constipation. The majority of the elderly have normal frequency of bowel movements but strain at stool. This is probably a result of sedentary lifestyle, a decreased fluid intake, poor nutrition, avoidance of fibrous foods and chronic illness. Women are two to three times more likely to suffer from constipation than men and 40% of women in late pregnancy experience constipation.

Aetiology

The normal function of the large intestine is to remove water and various salts from the colon, drying and expulsion of the faeces. Any process that facilitates water resorption will generally lead to constipation. The commonest cause of constipation is an increase in intestinal tract transit time of food which allows greater water resorption from the large bowel leading to harder stools that are more difficult to pass. This is most frequently caused by a deficiency in dietary fibre, a change in lifestyle and/or environment and medication. Occasionally, patients ignore the defecatory reflex as it maybe inconvenient for them to defecate.

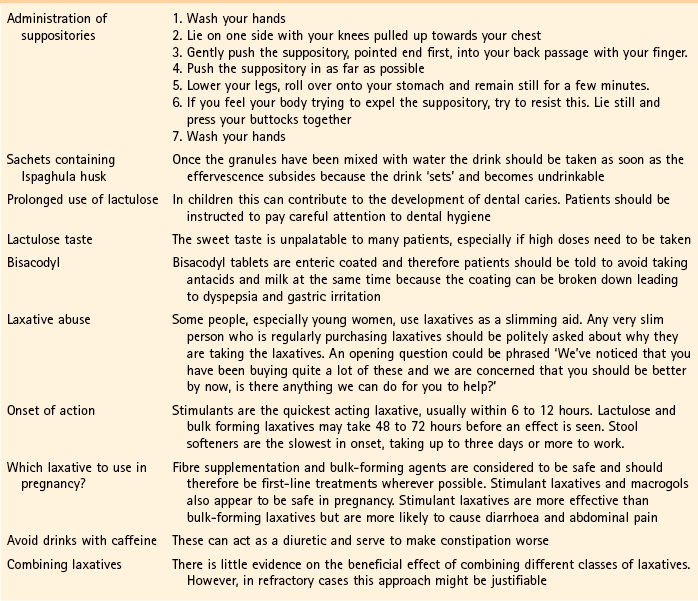

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

The first thing a pharmacist should do is to establish the patient’s current bowel habit compared to normal. This should establish if the patient is suffering from constipation. Questioning should then concentrate on determining the cause because constipation is a symptom and not a disease and can be caused by many different conditions. Constipation does not usually have sinister pathology and the commonest cause in the vast majority of non-elderly adults will be a lack of dietary fibre (Table 6.17). However, constipation can be caused by medication and many disease states including neurological disorders (e.g. multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease), metabolic and endocrine conditions (diabetes, hypothyroidism) and neoplasm. A number of constipation-specific questions should always be asked of the patient to aid in diagnosis (Table 6.18).

Table 6.17

Causes of constipation and their relative incidence in community pharmacy

| Incidence | Cause |

| Most likely | Eating habits/lifestyle |

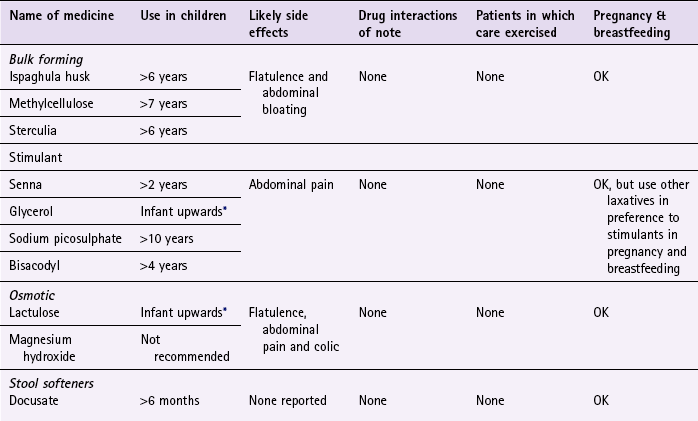

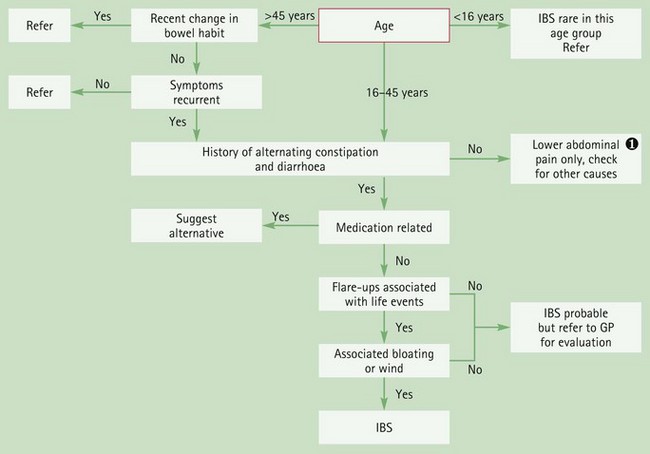

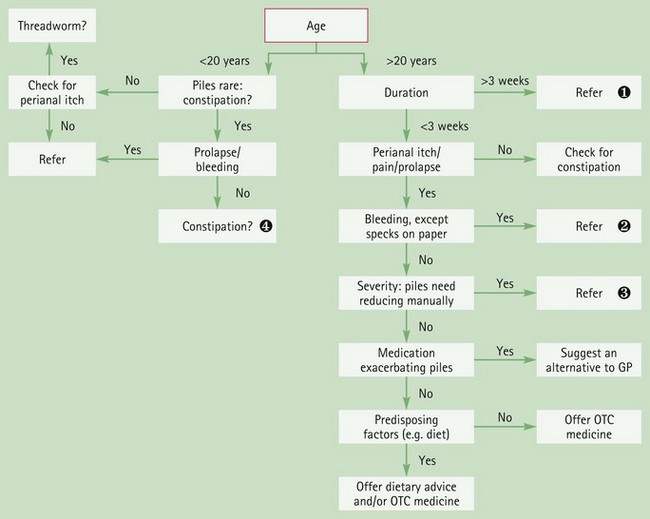

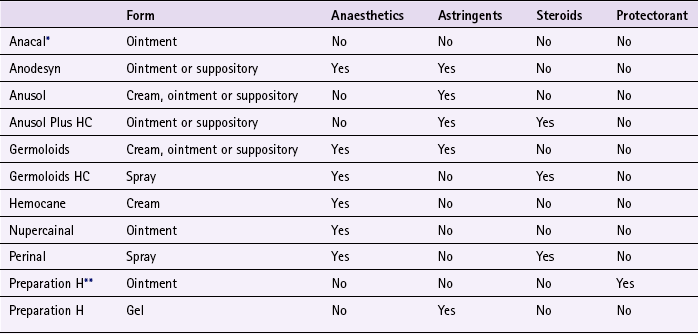

| Likely | Medication |