Paediatrics

Background

A number of conditions are encountered much more frequently in children than the rest of the population. It is these conditions that this chapter focuses on. A small number of conditions that affect all age groups but are often associated with children are not included, for example middle ear infection. Such conditions are covered in other chapters and where appropriate will be cross-referenced to the relevant sections within the text.

History taking

In the majority of cases pharmacists will be heavily dependent on getting details about the child’s problem from their parents or an adult responsible for the child’s welfare. This presents both benefits and problems to the pharmacist. Parents will know when their child is not well and asking the parent about the child’s general health will help to determine how poorly the child actually is. For example, a child who is running around and lively is unlikely to be acutely ill and referral to a GP is less likely. The major problem faced by all healthcare professionals is the difficulty in gaining an accurate history of the presenting complaint. This poses difficulties in assessing the quality and accuracy of the information as children find it hard to articulate their symptoms. If the child can be asked questions, these often have to be posed in either closed or leading formats to elicit information.

As a rule of thumb, any child who appears visibly ill should always be seen by the pharmacist and referral might well be needed, whereas children who are acting normally and appear generally well will often not need to see the GP and can be managed by the pharmacist.

Head lice

Humans act as hosts to three species of louse; Pediculus capitis (head lice), Pediculus corporis (body lice) and Pediculus pubis (pubic lice). Only head lice are discussed in this section.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Head lice affect all ages, although they are much more prevalent in children aged 4 to 11 years, especially girls. Studies conducted in schools show wide variation of current lice infestation ranging from 4 to 22% of pupils. Head lice can occur at any time and do not show any seasonal variation. Most parents will have experienced a child who has head lice, or received letters from school alerting parents to head lice infestation within the school.

Aetiology

Head lice can only be transmitted by head-to-head contact. Fleeting contact will be insufficient for lice to be transferred between heads. Once transmitted lice begin to reproduce. The adult louse lives for approximately 1 month. Throughout this time the female louse lays several eggs at the base of a hair shaft each night. Eggs hatch after 7 to 10 days, leaving the egg case attached to the hair shaft (known as a ‘nit’). In the course of maturing to adulthood the young louse (the nymph) undergoes three moults. Shortly after maturing, the female louse is sexually mature and able to mate.

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

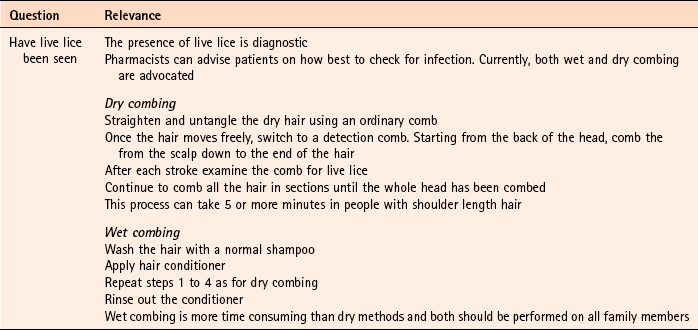

Most parents will diagnose head lice themselves or be concerned that their child has head lice because of a recent local outbreak at school. Occasionally parents will also want to buy products to prevent their child contracting head lice. It is the role of the pharmacist to confirm a self-diagnosis and stop inappropriate sales of products. It should also be remembered that an itching scalp in children is not always due to head lice and other causes should be eliminated. Asking a number of symptom-specific questions should enable a diagnosis of head lice to be easily made (Table 9.1).

Clinical features of head lice

Unless live lice have been found, most patients will present with scalp itching. Itching is caused due an allergic response of the scalp to the saliva of the lice and can take weeks to develop. However, only a third of patients experience itching. Head lice are most commonly found in the occipital and auricular areas.

Conditions to eliminate

Dandruff can cause irritation and itching of the scalp. However, the scalp should be dry and flaky. Skin debris might also be present on clothing.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Typically, seborrhoeic dermatitis will affect areas other than the scalp, most notably the face. If only scalp involvement is present then the child might complain of severe and persistent dandruff. In infants the child will have large yellow scales and crusts of the scalp (cradle cap).

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Treatment options include insecticides, wet combing and physical agents. All treatments available in the UK have shown varying degrees of clinical effectiveness. It is however difficult to assess which treatment is most effective as very few comparative trials have been performed, and insecticidal resistance varies from region to region. No treatment is 100% effective and failure has been linked with poor adherence to each treatment regimen. Of the treatment approaches, insecticides have been most studied. These include malathion, permethrin, carbaryl and phenothrin – the latter two are now not commercially available. Cure rates of 70 to 80% are reported with insecticides in recent clinical trials, although resistance to insecticides is now a serious problem and appears to be increasing. Wet combing is an alternative treatment option, however, cure rates are reported to be only 40 to 60% with the low cure rates attributed to poor adherence (Roberts et al 2000; Hill et al 2005).

Dimeticone is a recent introduction to the market, and is thought to work by coating the lice both internally and externally, which leads to disruption in water excretion causing the gut of the lice to rupture from osmotic stress (Burgess 2009). Its inclusion in treatment options seems to stem from 1 robust trial conducted by Burgess et al (2005). Dimeticone was compared against phenothrin with cure rates determined at days 9 and 14. Dimeticone was shown to have comparable cure rates to phenothrin (69% compared to 78%). The study has been criticised for using dry detection methods and using different detection days (days 5 and 12 as recommended by the department of health), however a further trial in 2007 supports the 2005 trial results. In the latter study, 4% dimeticone lotion, applied for 8 hours or overnight was compared to 0.5% malathion liquid applied for 12 hours or overnight. The results found dimeticone was significantly more effective than malathion, with 30/43 (70%) participants cured using dimeticone compared with 10/30 (33%) using malathion.

Isopropyl myristate is a recent introduction to the UK market. Like dimeticone it is pharmacologically inert but works by blocking the tracheal breathing system and coating the surface of lice with a thin film of fluid (Drugs and Therapeutics Bulletin 2009). Evidence of efficacy comes from 2 trials that compared isopropyl myristate against permethrin. Results found isopropyl myristate was significantly more effective than permethrin (82% vs 19%). Although these results seem impressive, the comparator drug was permethrin – a product not recommended due to its poor efficacy.

Other non-insecticidal methods of eradication are also promoted. These include herbal remedies such as tea tree oil or essential oils (e.g. Lyclear SprayAway), coconut oil (Lice Attack, Nitlotion) and electric combs. No credible evidence exists on the effectiveness of these products and should not be recommended until such time that data supports their use.

In summary, treatment used will be driven by individual preference, the patient’s medical history and previous exposure to treatment regimens. Wet combing (available as bug busting kits) is time consuming and requires patient motivation but is helpful in areas of high insecticidal resistance. Insecticides, dimeticone and isopropyl myristate are simpler to use than bug-busting kits and appear to have higher cure rates. Based on current evidence it seems dimeticone is treatment of choice.

Practical prescribing and product selection

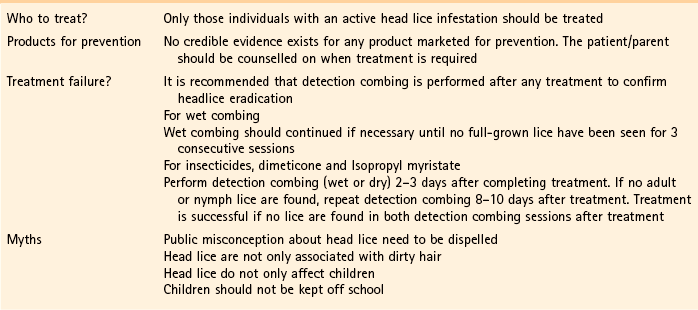

Prescribing information relating to medicines for head lice reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 9.2; useful tips relating to patients presenting with head lice are given in Hints and Tips Box 9.1. All products have to be used more than once; insecticides have to be repeated 7 days after first application (this is based on expert opinion, as the second application is intended to kill nymphs emerging from eggs that have survived the first application); wet combing every 4 days for at least 2 weeks. Coating agents, dimeticone and isopropyl myristate also have to be repeated after 7 days.

All products, except isopropyl myristate, can be used on children older than 6 months. Dimeticone or wet combing is recommended for pregnant and breastfeeding women. When applying all products, pay particular attention to the areas behind the ears and at the nape of the neck, as these areas are where lice are most often found.

Permethrin (Lyclear Creme Rinse)

Before application the hair should be washed with a mild shampoo and towelled dry. Enough Lyclear should be applied to the hair to ensure the hair and scalp is thoroughly saturated. It should be left on the hair for 10 min before rinsing the hair thoroughly with water. One bottle is sufficient for shoulder length hair of average thickness. It rarely causes scalp reddening and irritation.

Malathion (Derbac-M liquid)

Malathion used to be available as a liquid, lotion or shampoo. However, lotions and shampoos are now no longer available. Derbac-M should be applied to dry hair and left for 12 hours before washing off.

Dimeticone 4% Lotion (Hedrin)

Hedrin is applied to dry hair and the scalp ensuring that the scalp is fully covered. The lotion should be spread evenly from the hair root to the tips. It has to be left on for a minimum of 8 hours (over night is preferable) before being washed out with shampoo. (Note, a product containing 92% dimeticone, NYDA spray, is available.)

References

Anon. Update on treatments for headlice. DTB. 2009;47:50–52.

Burgess, IF. The mode of action of dimeticone 4% lotion against head lice, Pediculus capitis. BMC Pharmacol. 2009;9(1):3.

Burgess, IF, Brown, CM, Lee, PN. Treatment of head louse infestation with 4% dimeticone lotion: randomised controlled equivalence trial. Br Med J. 2005;330:1423–1425.

Hill, N, Moor, G, Cameron, MM, et al. Single blind, randomised, comparative study of the Bug Buster kit and over the counter pediculicide treatments against head lice in the United Kingdom. Br Med J. 2005;331:384–387.

Roberts, RJ, Casey, D, Morgan, DA, et al. Comparison of wet combing with malathion for treatment of head lice in the UK: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:540–544.

Anon. Management of headlice in primary care. MeReC Bulletin. 2008;18(4):2–7.

Burgess, IF, Brown, CM, Peock, S, et al. Head lice resistant to pyrethroid insecticides in Britain. Br Med J. 1995;311:752.

Burgess, IF, Lee, PN, Matlock, G. Randomised, controlled, assessor blind trial Comparing 4% dimeticone lotion with 0.5% malathion liquid for head louse infestation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(11):e1127. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001127

Connolly, M. Current recommended treatments for headlice and scabies. The Prescriber. 2011;Jan:26–39.

Dodd, CS. Interventions for treating headlice. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2006. (Status withdrawn Issue 2, 2012, pending update)

Community Hygiene Concern. http://www.chc.org/bugbusting/

Pediculosis.com. http://www.pediculosis.com/

Once a week – take a peek. http://www.onceaweektakeapeek.com/.

Threadworm (Enterobius vermicularis)

Background

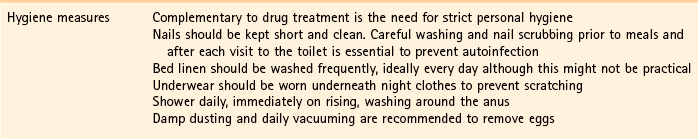

Worm infections are extremely common both in the developed and developing world. In Western countries the most common worm infection is threadworm (known in some countries as pinworm), which is a condition that causes inconvenience and embarrassment. Social stigma surrounds the diagnosis of threadworm, with many patients believing that infection implies a lack of hygiene. This belief is unfounded as infection occurs in all social strata. The patient might benefit from reassurance from the pharmacist, explaining that the condition is very common and is nothing to be ashamed or embarrassed about.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Threadworm is the most common helminth infection throughout temperate and developed countries. Threadworm prevalence is difficult to establish due to the high number of people who self medicate or are asymptomatic. However, UK prevalence rates have been estimated at 20% in the community, rising to 65% in institutionalised settings. Threadworms are much more common in school or pre-school children than adults, because of their inattention to good personal hygiene.

Aetiology

Eggs are transmitted to the human host primarily by the faecal–oral route (autoinfection) but also by retroinfection and inhalation. Faecal–oral transmission involves eggs lodging under fingernails, which are then ingested by finger sucking after anal contact. Retroinfection occurs when larvae hatch on the anal mucosa and migrate back into the sigmoid colon. Finally, threadworm eggs are highly resistant to environmental factors and can easily be transferred to clothing, bed linen and inanimate objects (e.g. toys) resulting in dust-borne infections. Once eggs are ingested, duodenal fluid breaks them down and releases larvae, which migrate into the small and large intestines. After mating, the female migrates to the anus, usually at night, where eggs are laid on the perianal skin folds, after which the female dies. Once laid, eggs are infective almost immediately. Transmission back into the gut can then take place again via one of three mechanisms outlined above and so the cycle is perpetuated.

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Threadworm diagnosis should be one of the more simple conditions to diagnose as patients present with very specific symptoms.

Clinical features of threadworm

Night-time perianal itching is the classic presentation (caused from the mucus produced by females when laying eggs). However, patients might experience symptoms ranging from a local ‘tickling’ sensation to acute pain. Any child with night-time perianal itching is almost certain to have threadworm. Itching can lead to sleep disturbances resulting in irritability and tiredness the next day. Diagnosis can be confirmed by observing threadworm on the stool, although they are not always visible.

Complicating factors such as excoriation and secondary bacterial infection of the perianal skin can occur due to persistent scratching. The parent should be asked if the perianal skin is broken or weeping.

Conditions to eliminate

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

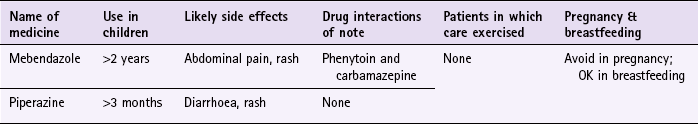

Mebendazole and piperazine are available OTC for the treatment of threadworm. There is a large body of evidence to support the effectiveness of mebendazole in roundworm infections but for other worm infections, including threadworm, cure rates are lower. For threadworm, cure rates between 60 and 82% for single-dose treatment of mebendazole have been reported (Rafi et al 1997; Sorensen et al 1996).

Piperazine appears to have less evidence supporting its effectiveness than mebendazole. One study has compared piperazine against mebendazole and found mebendazole to have a higher cure rate than piperazine; although the number of patients in the trial was low.

The difference in cure rates might be, in part, due to their respective mechanism of action. Mebendazole inhibits the worm’s uptake of glucose, thus killing them, whereas piperazine only paralyses the worm (if paralysis wears off then the worm might be able to migrate back into the colon and thus treatment would fail). To optimise worm clearance from the gut piperazine formulations also contain senna.

Practical prescribing and product selection

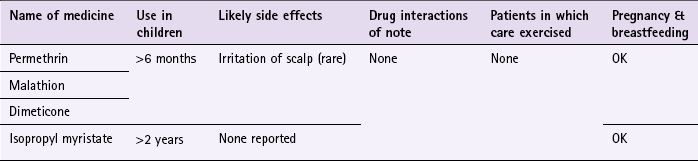

Prescribing information relating to medicines for threadworm reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 9.3; useful tips relating to patients presenting with threadworm are given in Hints and Tips Box 9.2.

Treatment should ideally be given to all family members and not only the patient with symptoms, as it is likely that other family members will have been infected even though they might not show signs of clinical infection. A repeated dose 14 days later is often recommended to ensure worms maturing from ova at the time of the first dose are also eradicated.

Mebendazole and piperazine should be avoided in pregnancy because foetal malformations have been reported but appear safe in breastfeeding. Pregnant women should be advised to practise hygiene measures for 6 weeks to break the cycle of infestation. If treatment is absolutely essential, piperazine has been used, although this should not be in the first trimester.

Mebendazole (e.g. Ovex, Pripsen Mebendazole)

The dose for adults and children over 2 is 100 mg (either a single tablet or 5 mL of suspension). Young children might prefer to chew the tablet and it has been formulated to taste of orange. Side effects reported include abdominal pain, diarrhoea and rash but are very rare. It does interact with cimetidine, increasing mebendazole plasma levels but this is of little clinical consequence. However, phenytoin and carbamazepine decrease mebendazole plasma levels and the dose of mebendazole may need to be increased.

Piperazine (e.g. Pripsen Piperazine Phosphate Powder)

Piperazine is available as a sachet. It can be given from 3 months of age upwards. The dose for children should be given in the morning (for adults the dose is recommended to be taken at night). From 3 months to 1 year, half a 5 mL spoonful should be taken; for children aged 1 to 6 years the dose is one 5 mL spoonful and for children over 6 years (and adults) 1 sachet should be taken. The sachets can be taken in water or milk.

A number of side effects have been reported with piperazine but all are of GI origin such as diarrhoea or allergic reactions, for example rash.

Albonico, M, Smith, PG, Hall, A, et al. a randomized controlled trial comparing mebendazole and albendazole against Ascaris, Trichuris and hookworm infections. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:585–589.

Anon. Merec Bulletin. Management of threadworms in primary care. 1998;18:11–13.

Zaman, V. Other gut nematodes. In: Weatherall DJ, Ledingham JGG, Warrell DA, eds. Oxford textbook of medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Colic

Background

There is no universally agreed definition of colic. A widely used definition of colic is that proposed by Wessel et al (1954) and has come to be known as the ‘rule of threes’. Wessel proposed that an infant could be considered to have colic if it cries for more than 3 hours a day for more than 3 days a week for more than 3 weeks. However, the definition by Wessel is arbitrary and few parents are willing to wait 3 weeks to see if the infant meets the criteria for colic. As a result the third criterion is usually dropped in the clinical setting. In addition, some authors have defined crying for as little as 90 minutes per day as excessive. Regardless of which definition is used, persistent crying is a cause of stress and anxiety to parents.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Due to no universally accepted definition of colic its prevalence is difficult to determine, and estimates vary widely from 3 to 40% dependent on which definition is used. Studies reporting lower figures strictly applied Wessel’s criteria, whilst higher figures used wider definitions. It is likely that prevalence falls between the two extremes and affects 10 to 20% of infants.

Colic starts in the first few weeks of life and usually resolves by the age of 3 to 5 months.

Aetiology

The cause of colic is poorly understood but seems to be multifactorial. It has been linked to a disorder of the GI tract, where spasmodic contraction of smooth muscle causes pain and discomfort, which might be caused by allergy to cow’s milk or lactose intolerance. It has also been suggested that it might stem from emotional, behavioural and social problems that include underdeveloped parenting skills, inadequate social network, postpartum depression, and parental anxiety and stress.

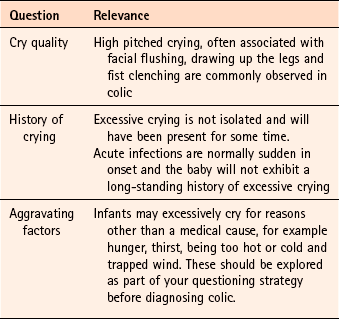

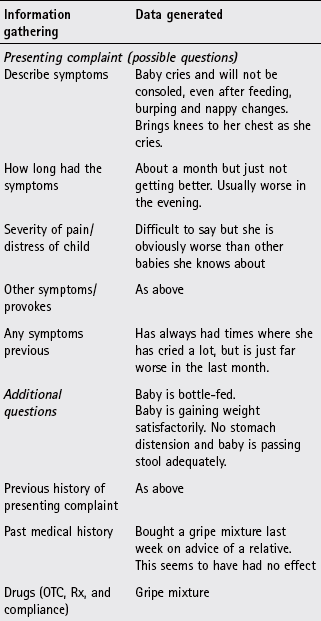

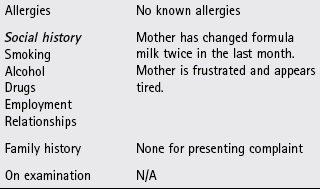

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

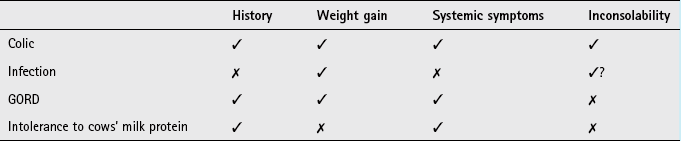

It can be difficult to determine if the baby has colic or is just excessively crying, as the diagnosis of the condition is dependent on qualitative descriptions. However, the term colic is often wrongly applied to any infant who cries more than usual. Asking a number of symptom specific questions should enable a diagnosis of colic to be made (Table 9.4).

Clinical features of colic

Excessive crying and inconsolable crying are obvious clinical features. Pain may be mild, merely causing the child to be restless in the evenings or severe resulting in rhythmical screaming attacks lasting a few minutes at a time, alternating with equally long quiet periods in which the child almost goes to sleep, before another attack starts. Attacks appear to be more common in the early evening, giving rise to the name 6.00pm colic. However, normal infant crying and the crying in colic both peak in the late afternoon and early evening and is therefore of limited value. The infant will be healthy and thriving.

Conditions to eliminate

Colic and acute infections of the ear or urinary tract can present with almost identical symptoms. However, in acute infection the child should have no previous history of excessive crying and have signs of systemic infection such as fever.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

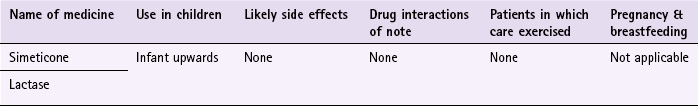

Parents should be reassured that the child’s symptoms will subside over time, that their baby is well and they are not doing something wrong. Most parents will want to buy some form of medical treatment. Treatments include simeticone, lactase enzymes, low-lactose milk formulas and gripe mixtures. None have a credible evidence base.

Simeticone is reported to have antifoaming properties, reducing surface tension and allowing easier elimination of gas from the gut by passing flatus or belching. It is widely used yet has very limited evidence of efficacy. Of three trials reported, only one found a small improvement in the number of crying attacks. This trial was small (n = 26) and suffered from methodological flaws and so results should be viewed with caution.

Lactase enzymes

Lactase breaks down lactose present in milk to glucose and galactose. This reduction in lactose concentration is reported to improve colic symptoms but four small trials investigating its effect were inconclusive.

Low-lactose formulas should not be recommended as studies conducted to date have been of poor methodological quality. No trial data exists for gripe mixtures and therefore should be avoided.

Summary

Although evidence for simeticone and lactase enzymes is not strong it would seem unreasonable not to let parents try either for a trial period of a week if they are finding it difficult to cope. If no response is seen then referral to the GP for an alternative formula feed would be advisable.

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to dimethicone is discussed and summarised in Table 9.5; useful tips relating to colic are given in Hints and Tips Box 9.3.

Simeticone (e.g. Infacol and Dentinox)

Simeticone is pharmacologically inert; it has no side effects, drug interactions or precautions in its use and can therefore be safely prescribed to all infants. It should be given with or just after each feed. Products contain different strengths of simeticone, however the dose administered to the child is almost equivalent, for example Infacol 0.5 to 1 mL (20 to 40 mg) and Dentinox 2.5 mL (21 mg).

Lactase enzyme (Colief)

The dose of Colief differs depending if the baby is formula or breast fed: if breastfeeding, four drops should be added to a small amount of expressed milk and the baby breast fed as normal; if using an infant formula then the feed should be made up as usual and four drops added to warm, but not hot, formula. If making the formula up in advance then add two drops of Colief and store in the fridge for 4 hours.

Barr, RG, Lessard, J. Excessive crying. In: Bergman AB, ed. 20 Common Problems in Paediatrics. USA: McGraw-Hill, 2001.

Garrison, MM, Christakis, DA. A systematic review of treatments for infant colic. Pediatrics. 2000;106:184–190.

Lucassen, PL, Assendelft, WJ, Gubbels, JW, et al. Effectiveness of treatments for infantile colic: systematic review. Br Med J. 1998;316:1563–1569.

Kanabar, D. Current treatment options in the management of infantile colic. The Prescriber. 2008;5th April:24–29.

NCCPC – Postnatal Care. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/10988/30146/30146.pdf

CRY-SIS. www.cry-sis.org.uk

The Breastfeeding Network. http://www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/

General sites on colic. http://www.colichelp.com/. http://www.infacol.co.uk/home and http://www.colief.co.uk/

Atopic dermatitis

Background

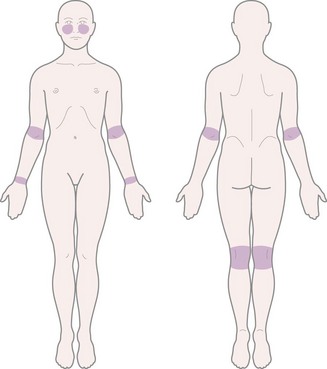

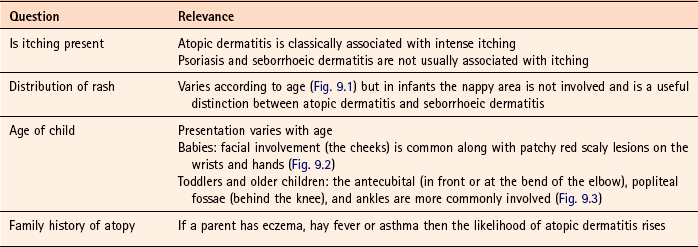

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic non-infective inflammatory skin condition which is characterised by an itchy red rash. It usually starts within the first 6 months of life and predominantly affects young children. The majority (60–70%) of patients will ‘grow out’ of the condition by their early teens. However, in a small number of patients atopic dermatitis persists into adulthood where the condition becomes chronic. Atopic dermatitis can impair the quality of life of patients and their families. Typical distribution of atopic dermatitis is illustrated in Fig. 9.1.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis is unclear. Rates vary from country-to-country. In the UK prevalence rates have been rising, and it now affects 15 to 20% of children, although over 80% are reported to have mild disease. The condition usually presents in infants aged between 2 and 6 months, but it can occur in older children. Upward of 60% of children will have onset within the first year, rising to 80% within the first 5 years. Atopic dermatitis is much less common in adults affecting only 1 to 3% of people.

Aetiology

Atopic dermatitis has a strong genetic component, although the precise genetic cause is unknown. Two-thirds of people with the disease have a family history of atopic dermatitis, asthma or hay fever. Atopic dermatitis is present in approximately 80% of children where both parents are affected and in 60% if one parent is affected. In addition a number of environmental factors have been implicated in the development or worsening of the condition and include certain foods (e.g. dairy products), stress, extremes of heat and humidity, and irritants such as detergents and chemicals.

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

To help with diagnosis, criteria based protocols are available, for example those produced by the British Journal of Dermatology and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), which state atopic dermatitis can be diagnosed if the person has had an itchy skin condition in the past 12 months plus three or more of the following:

• onset before age of 2 years (Fig. 9.2)

Fig. 9.2 Atopic dermatitis in an infant. Reproduced from B J Zitelli, H W Davis, 1997, Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis, 3rd edition, Mosby, with permission.

• history of eczema in the skin creases (and also the cheeks in children under 10 years)

• visible flexural eczema (inside elbows, behind knees (Fig. 9.3) or involvement of the cheeks/forehead and outer limbs in children under 4 years)

Asking a number of symptom-specific questions should enable a diagnosis of atopic dermatitis to be made (Table 9.6).

Clinical features of atopic dermatitis

A typical presentation of a child with atopic dermatitis is an irritable, scratching child with dermatitis of varying severity. Itching is the predominant symptom which can induce a vicious cycle of scratching, leading to skin damage, which in turn leads to more itching - the so called ‘itch scratch itch’ cycle. The child might have had the symptoms for some time and the parent has often already tried some form of cream to help control the itch and rash. Scratching can lead to broken skin, which can become infected. There is a tendency to a dry sensitive skin even in those who have ‘grown out’ of the disease.

Once a diagnosis has been established and before treatment is considered it is important to make an assessment on the severity and social impact of the condition (Table 9.7).

Table 9.7

Severity and social impact of atopic dermatitis

| Severity* | Psychological impact* |

| Clear: normal skin, no evidence of active eczema. | None: no impact on quality of life. |

| Mild: areas of dry skin, infrequent itching (with or without small areas of redness). | Mild: little impact on everyday activities, sleep, and psychosocial well-being. |

| Moderate: areas of dry skin, frequent itching, redness (with or without excoriation and localised skin thickening). | Moderate: moderate impact on everyday activities and psychosocial well-being, and frequently disturbed sleep. |

| Severe: widespread areas of dry skin, incessant itching, redness (with or without excoriation, extensive skin thickening, bleeding, oozing, cracking, and alteration of pigmentation). | Severe: severe limitation of everyday activities and psychosocial functioning, and loss of sleep every night. |

Conditions to eliminate

Seborrhoeic dermatitis in infants typically occurs in the first 6 months. Itching is generally not present and the condition usually spontaneously resolves after a few weeks and seldom recurs. It usually affects the scalp, face and napkin area. Large yellow scales and crusts often appear on the scalp and are often referred to as cradle cap (Fig. 7.10).

Psoriasis

Psoriasis can be mistaken for atopic dermatitis, because the rash is erythematous and can occur on parts of the body such as the scalp, elbows and knees, which is a common location for atopic dermatitis in older children. However, the rash is raised, has well defined boundaries with a silvery-white scaly appearance that are typically symmetrical. Itch, if present, is mild (Fig. 7.3).

Contact dermatitis

Seen as a red itchy skin rash seen at any site related to exposure border (Fig. 7.27).

Fungal infection

The rash is pink or red, itchy, slightly raised annular patch with a well defined inflamed border (Fig. 7.14). It can occur on all body surfaces.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

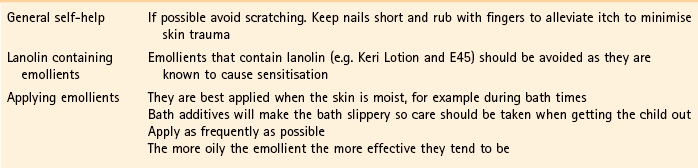

The mainstay of treatment for atopic dermatitis consists of avoiding potential irritants, managing dry skin, controlling itching and using topical corticosteroids to treat flare ups. Unfortunately, the latter option is not available to children under the age of 10 due to OTC license restrictions.

Avoiding irritants

Where practical, factors that worsen dermatitis should be avoided. The use of highly perfumed soaps and detergents should be discouraged and replaced with soap substitutes (e.g. Alpha Keri, Neutrogena, Dove). Patients should be told to have lukewarm not hot baths, because in some patients hot water can aggravate the problem. In addition a bath additive should be used (e.g. Balneum, Oilatum, Emulsiderm) to help hydration of the skin.

Emollients

It is believed emollients add moisture to the skin and repair the lipid barrier function whilst also helping to prevent penetration by irritants and decrease the need for steroids. Despite a lack of high quality randomised controlled trials, emollients are well established as first line treatment for atopic dermatitis. In addition, no trials appear to have addressed whether one emollient is superior to another. Patients might have to try several emollients before finding one that is most effective for their skin.

Antihistamines

There appears to be no clinical trial data on the use of sedative antihistamine for reducing pruritus in atopic dermatitis; however, they are often prescribed to children to help with itching. The American Academy of Dermatology guidelines on the treatment of atopic dermatitis report there is little evidence for the use of antihistamines; however, they suggest that sedating antihistamines may be useful where there is significant sleep disruption due to itching (Hanifin et al 2004).

Corticosteroids

A substantial body of evidence exists for corticosteroids in controlling all types of dermatitis, including atopic dermatitis. If the symptoms warrant corticosteroid therapy then the patient needs to be referred to the GP. Usually mild steroids such as hydrocortisone (1 to 2.5%), preferably in an ointment base should be prescribed twice daily.

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to medicines for atopic dermatitis reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 9.8; useful information regarding emollients containing lanolin is given in Hints and Tips Box 9.4.

Emollients

There are a plethora of emollient products marketed and which one a patient uses will be dictated by patient response and acceptability. All emollients should be regularly and liberally applied with no upper limit on how often they can be used. All are chemically inert and therefore can be safely used from birth upwards. For a summary of emollient products see Table 7.32.

Sedating antihistamines

Although no sedating antihistamine products, except hydroxyzine (POM), have a specific product license for the treatment of pruritus, they are frequently prescribed by GPs and could be given OTC. However, it must be remembered that if recommended then the person concerned is acting outside the product license and will be therefore liable for any clinical consequence associated with the use of the product. The doses that can be given for the various sedating antihistamines are listed below.

Chlorphenamine (Piriton): Chlorphenamine can be given from the age of 1 year. Children up to the age of 2 years should take 2.5 mL of syrup (1 mg) twice a day. For children aged between 2 and 5 the dose is 2.5 mL (1 mg) three or four times a day and those over the age of 6 should take 5 mL (2 mg) three or four times a day.

Clemastine (Tavegil): Clemastine is taken twice a day by children over the age of 1 year. Those aged between 1 and 3 should take 250 to 500 µg, children aged between 3 and 6 should take 500 µg and for those over 6 the dose is 500 µg to 1 mg. Tavegil is only available as 1 mg tablets and so dosing in young children is difficult.

Reference

Hanifin, JM, Cooper, KD, Ho, VC, et al. Guidelines of care for atopic dermatitis, developed in accordance with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)/American Academy of Dermatology Association ‘Administrative Regulations for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines’. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(3):391–404.

Brown, S, Reynolds, NJ. Atopic and non-atopic eczema. Br Med J. 2006;332:584–588.

Clark, C, Hoare, C. Making the most of emollients. Pharm J. 2001;266:227–229.

National Eczema Society. http://www.eczema.org/

General dermatology site. http://www.dermatologist.co.uk/index.html

Fever

Background

Fever is simply a rise in body temperature above normal. Normal oral temperature is 37°C (98.6°F), plus or minus 1°C, although rectal temperature is about 0.5°C higher and under arm temperature 0.5°C lower than oral temperature. During the course of 24 hours minor fluctuations in temperature are observed. Fever is often classified as being either mild (low-grade) (up to 39°C) or high (above 39°C).

In a practice setting, for those aged under 5 years of age, the best temperature to take is under the arm using an electronic or chemical dot thermometer. Infrared tympanic thermometers are also advocated (NICE guidance No. 47, May 2007) but a systematic review by Dodd et al (2006) questioned their reliability. Forehead strip thermometers are popular because they are easy to use, but should not be used as they are unreliable.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Fever is a common symptom of many conditions, and in children viral, and to a lesser extent bacterial, causes are most commonly implicated. It has been reported that fever is probably the commonest reason for a child to be taken to a doctor.

Aetiology

Body temperature is regulated closely because temperature changes can significantly alter cellular functions and, in extreme cases, lead to death. Thermoregulation is a balance between heat production and heat loss. Cellular metabolism produces heat and this means that energy – in the form of heat – is produced continually by the body. This heat production is lost through the skin by radiation, evaporation, conduction and convection. The thermoregulation centre located in the hypothalamus controls the whole process. When body temperature reaches its ‘set point’ (approximately 37°C) mechanisms to lose or conserve heat are activated. When a person suffers from a fever this suggests that there is some defect in the temperature regulating control system. In fact the system is functioning normally but with an adjusted higher ‘set point’. This process is complex but involves the production of pyrogens (fever-causing substances) that alter the set point.

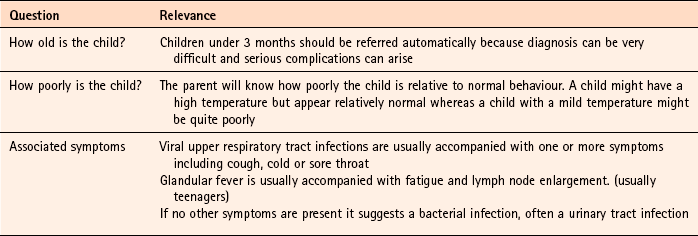

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

The parent, in nearly every instance, will diagnose fever in the child. This is usually a subjective perception by the parent that the child feels warm or is off colour. The importance of the parent’s perception should not be underestimated or dismissed if the child’s temperature has not been taken. Many healthcare professionals often place too much value on an empirical figure when in many instances the look of the child is more important than the height of the fever. Asking a number of symptom specific questions should enable the pharmacist to treat or refer the child with fever (Table 9.9).

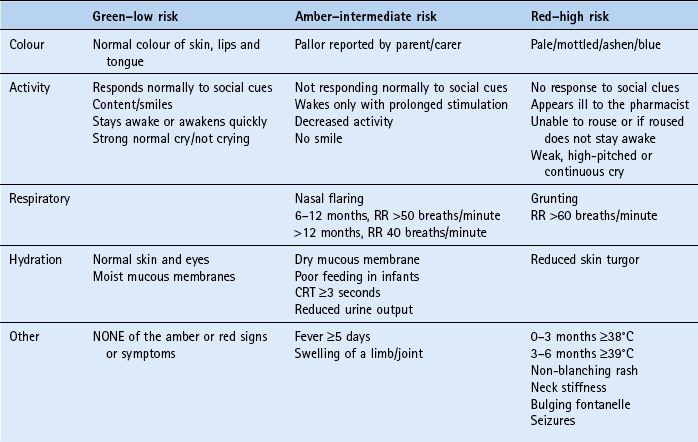

NICE in the UK recommend using a ‘traffic light’ system to assess the risk of serious disease (Table 9.10). In a pharmacy setting any child that show symptoms or signs of intermediate (amber) or high (red) risk should be referred to the GP

Table 9.10

Assessment of the seriousness of fever in children under 5 years of age

CRT, capillary refill time; RR, respiration rate.

Table adapted from NICE. CG 47 Feverish illness in children: assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 years. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007. Reproduced with permission. Guidelines are accurate at time of going to press. Latest guidelines are available at http://www.nice.org.uk/CG47

Clinical features of fever

A child with fever will generally be irritable, off his or her food and seek greater parental attention. Other signs that might be seen include facial flushing and shivering.

Conditions to eliminate

One of the most common causes of fever in children is urinary tract infection. Often the child will present only with fever. Other symptoms can be present and include irritability, poor feeding, vomiting or abdominal pain. Referral is needed.

Upper respiratory tract infections

It is rare for upper respiratory tract infections to present with fever alone. Cough, cold or sore throat is usually present. Treatment can be offered and referral is generally not needed unless secondary bacterial infection is suspected; earache symptoms might suggest this.

Roseola infantum (sixth disease)

Roseola infantum is probably caused by a neurodermotropic virus and is most prevalent in children under 1 year of age. Onset is with a sudden high fever (40°C) that usually subsides by the third or fourth day once the rash, which blanches when pressed, appears on the trunk and limbs. The condition is self-limiting.

Medicine-induced fever

A number of medicines can elevate body temperature and should be considered if no other cause can be determined. Penicillins, cephalosporins, macrolides, tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants and anti-inflammatory medicines, when associated with hypersensitivity, have all been associated with increasing temperature.

Meningitis

Meningitis should be considered in any child with fever and non-blanching rash, especially if the child looks ill and has other symptoms such as severe headache, photophobia, lethargy, drowsiness and neck stiffness. However, non-blanching rash is often seen late in symptom presentation so children with fever who exhibit decreased levels of consciousness or neck stiffness must be referred. Further information can be found on page 300.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Paracetamol and ibuprofen have been used for many years to treat fever in children. A number of reviews have looked at pharmacological and non-pharmacological intervention in reducing temperature. Two reviews by Meremikwu and Oye-Ita (2002, 2003) looked at the effect of paracetamol and tepid sponging in reducing fever. Conclusions from both reviews were guarded in stating they were effective, due to the small number of trials reviewed that met their inclusion criteria. This of course does not mean to say that these approaches are ineffective but that better, larger trials are required, although Watts et al (2001) concluded sponging does not seem to have a long-term effect. A further review by Perrott et al (2004) compared paracetamol and ibuprofen and concluded that single doses of ibuprofen were superior to paracetamol.

NICE guidance recommends that routine use of antipyretics should be avoided, although if deemed necessary (if the child is unwell or distressed) either paracetamol or ibuprofen can be used as monotherapy. Alternation of paracetamol and ibuprofen is not recommended; however, if the first drug used fails to control the temperature the other drug can be tried.

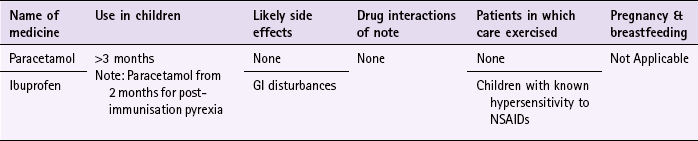

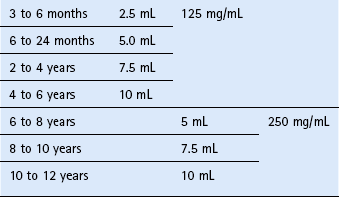

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to medicines for fever reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 9.11; useful tips relating to patients presenting with fever are given in Hints and Tips Box 9.5.

Paracetamol (e.g. Calpol, Disprol, Medinol)

Paracetamol is available as liquid, soluble tablets, sachets and melt tabs, although the most frequently purchased formulation is liquid. In addition paracetamol antihistamine combinations (Medised for children (diphenhydramine)) are available.

In 2011, the MHRA issued guidance on an updated dosing schedule for paracetamol. The updated dosing has a larger number of narrower age bands and defined a single dose per age band (Table 9.12).

For all age bands the maximum number of doses per day is four. Paracetamol has no commonly occurring side effects, does not interact with any medicines and so can be safely taken by all children.

Ibuprofen (e.g Nurofen, Calprofen)

Ibuprofen can be given to children over 3 months old. Doses for ibuprofen, like paracetamol, are age dependant as shown below:

• Age 3 months to 5 months: 50 mg three times a day.

• Age 6 months to 1 year: 50 mg three to four times a day.

• Age 1 year to 4 years: 100 mg three times a day.

• Age 4 years to 7 years: 150 mg three times a day.

Ibuprofen can cause gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea and diarrhoea and also interacts with many other medicines, although those medicines that interact with ibuprofen are very unlikely to be taken by children. Any child who has previously taken an NSAID and had an allergic reaction to it should avoid ibuprofen.

References

Dodd, SR, Lancaster, GA, Craig, JV, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of aural compared with rectal thermometers: a meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(4):354–357.

Meremikwu, MM, Oyo-Ita, A. Paracetamol versus placebo or physical methods for treating fever in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2002. [Art. No.: CD003676. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003676].

Meremikwu, M, Oyo-Ita, A. Paracetamol for treating fever in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2003.

Perrott, DA, Piira, T, Goodenough, B, et al. Review: Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen vs ibuprofen for treating children’s pain or fever: a meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:521–526.

Watts, R, Robertson, J, Thomas, G. The nursing management of fever in children. http://espace.library.curtin.edu.au/R/?func=dbin-jump-full&object_id=19279&local_base=gen01-era02, 2001. [Available from (accessed 22 November 2012)].

http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG47. (accessed 29 November 2012)

Nowak, TJ, Handford, AG. Essentials of Pathophysiology. USA: McGraw-Hill; 2000.

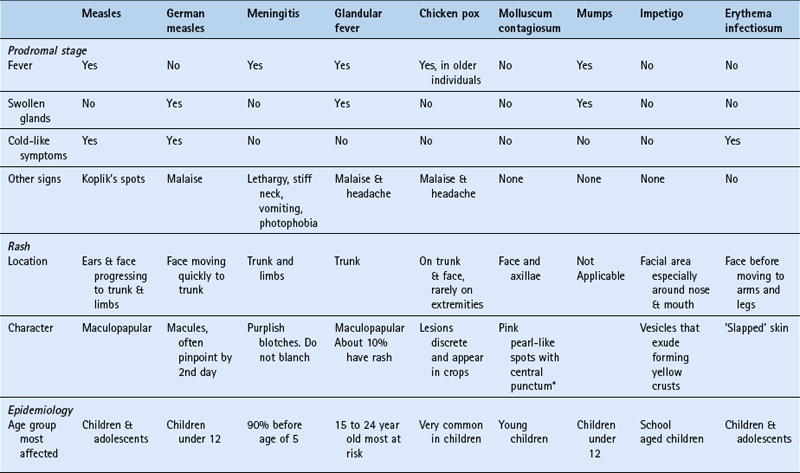

Infectious childhood conditions

Background

A number of infectious diseases are more prevalent in children than the rest of the population. Many of these diseases are now vaccine preventable and the provision of immunisation programmes has almost eradicated them from developed countries. However, some conditions have no vaccine or incomplete vaccine cover is provided, which means contraction of the disease is still possible. This usually results in the child suffering from mild symptoms from which a full and speedy recovery is made but in some circumstances, for example meningitis, infection can result in death. In addition, a report in The Lancet (1998) linking the triple vaccine for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) with autism (subsequently discredited) saw vaccination rates fall in the early 2000s. This has led to an increase in measles cases and even today (2012) vaccination rates in the UK for MMR are lower than for other vaccines. Mention of measles, mumps and rubella is therefore made at the end of this section for completeness.

Meningitis

Meningitis is usually caused by bacterial or viral infection. Viral meningitis is much more common than bacterial meningitis but – thankfully – viral infections are much less serious than bacterial causes. The peak incidence of contracting meningitis is between 6 and 12 months.

Signs and symptoms are non-specific in the early stages of the disease and are similar to flu. Symptoms range from fever, nausea, vomiting, headache and irritability. Symptoms can develop quickly – in a matter of hours - and be unpredictable, especially in infants and young children. Symptoms of fever, lethargy, vomiting and irritability are common in children aged between 3 months and 2 years. In infants, floppiness and the dislike of being handled are also common features. Symptoms which are more common in older children include severe headache, stiff neck and photophobia. Any child who experiences neck pain when asked to place their chin on their chest must be immediately referred.

In the latter stages of the disease a petechial or purpuric non-blanching rash characteristically develops in meningococcal infection.

The number of cases in the UK is now at their lowest ever levels due to the introduction of two vaccines into the UK vaccination schedule. The Hib vaccine was introduced in 1992 (active against Haemophilus influenzae) and the meningococcal C conjugate vaccine introduced in 1999 (active against serogroup C Meningococcus).

Chicken pox

Chicken pox is very common and is probably the most likely infectious childhood rash seen in community pharmacy. It is the primary infection observed when the patient contracts the varicella zoster virus, which is transmitted either by droplet infection or with contact with vesicular exudates. The incubation period ranges from 10 to 20 days and prior to the rash developing the patient might experience up to 3 days of prodromal symptoms that could include fever, headache and sore throat. The rash typically begins on the face and scalp, and spreads to the trunk and limbs. Initially, they appear as small red lumps that rapidly develop into vesicles, which crust over after 3 to 5 days. New lesions tend to occur in crops of 3 to 5 for the first 4 days so that at its height of infectivity lesions appear in all stages of development (Fig. 9.4). The vesicles are often extremely itchy and secondary bacterial infection due to the vesicles being scratched is not unusual. Chicken pox is highly contagious, from a few days prior to the onset of rash until all lesions have crusted over. Reinfection results in people suffering from shingles (Fig. 9.5). A vaccination has been available since the mid 1990s and shown to be 70 to 90% effective. It is part of standard vaccination schedules in countries such as the USA and Australia but currently not the UK.

Molluscum contagiosum

Caused by a pox virus, molluscum contagiosum is usually transmitted by indirect contact, for example sharing towels, although it is not very contagious. The face and axillae are common sites of infection. They generally appear in crops and appear as pink pearl-like spots usually less than 0.5 cm in diameter. All lesions have a central punctum that is a diagnostic feature (Fig. 9.6). Confusion should not arise with other conditions other than viral warts (for further information on warts see page 222). The condition will spontaneously resolve but if the parent or child is anxious then referral to the GP should be made because liquid nitrogen can be used to remove the lesions.

Impetigo

Impetigo is caused by a bacterial infection, most notably Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes. It presents mainly on the face, around the nose and mouth. It usually starts as a small red itchy patch of inflamed skin that quickly develops into vesicles that rupture and weep. The exudate dries to a brown, yellow sticky crust. (Fig. 9.7) It is contagious and children should be kept off school until the rash clears. General hygiene measures should include not sharing towels, which will help to stop household contacts contracting the infection. The child’s nails should be kept short to stop him or her from scratching the lesions. Treatment involves topical or systemic antibiotics (e.g. fusidic acid or flucloxacillin), which currently are not available OTC in most Western countries.

Measles

Since 1968 all infants in the UK have routinely been offered vaccination against measles. It is caused by an RNA virus and spread by droplet inhalation. It is the most dangerous of childhood diseases because of the complications that can occur. Approximately 7% of patients develop respiratory complications such as otitis media and pneumonia but encephalitis is seen in about one in every 600 to 1000 cases of measles.

Measles has an incubation period of between 7 to 14 days, which is then followed by 3 or 4 days of prodromal symptoms where the child will have a fever, head cold, cough and conjunctivitis. On the inner cheek and gums small white spots are visible, like grains of salt and are known as Koplik’s spots; these are diagnostic for measles. A blotchy red rash appears around the ears before moving on to the trunk and limbs. Immediate referral to the GP is needed.

German measles (rubella)

Rubella is caused by an RNA virus and spread by either close personal contact or airborne droplets. It is less contagious than measles and if contracted many people suffer from mild symptoms and the infection passes undiagnosed. After the incubation period of 14 to 21 days the child experiences up to 5 days of prodromal symptoms, which include cold-like symptoms and swollen glands in the neck before a rash appears on the face that quickly moves on to the trunk and extremities. The rash tends to be pinpoint and macular. The biggest threat posed by rubella is to women in early pregnancy, as foetal damage is possible.

Mumps

Mumps is caused by a paramyxovirus and is transmitted by airborne droplets from the nose and throat. It is the least contagious of the childhood diseases and requires close personal contact before infection can occur. There is an incubation period of 16 to 21 days followed by fever; this is followed by swelling of one or both parotid glands and the child will experience pain when the mouth is opened.

Mumps is much more unpleasant if contracted as an adult and in 20 to 30% of men the disease affects the testicles, with a serious infection possibly causing sterility. The most serious complication from mumps is meningitis (seen in approximately 10% of people).

Erythema infectiosum

Erythema infectiosum is also called ‘slapped cheek disease’ or ‘fifth disease’. It is caused by parvovirus B19 and predominantly affects children between the ages of 3 and 15. Cold-like symptoms appear a couple of days before the rash appears. Typically the rash appears on the cheeks that are red and inflamed (like the person has been slapped). Itch is often present and the rash can spread to the arms and legs.

Glandular fever (infectious mononucleosis)

Glandular fever is caused by the Epstein–Barr virus and is most commonly seen in patients aged between 15 and 24. In Western countries it is rare in children under 5 and less frequent in those aged between 5 and 14.

It is transmitted from close salivary contact and is also known as the kissing disease and has an incubation period of 4 to 7 weeks. Symptoms are vague but characterised by fatigue, headache, sore throat and swollen and tender lymph glands. A macular rash can also occur in a small proportion of patients. The symptoms tend to be mild but can linger for many months.

To aid the differential diagnosis of childhood conditions see Table 9.13.

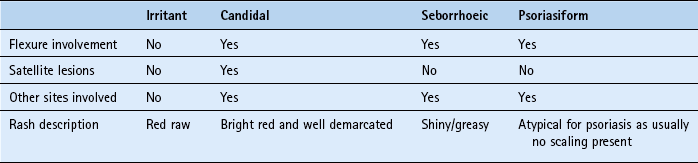

Nappy rash

Background

Napkin rash (also known as nappy dermatitis or diaper rash) is a non-specific term used to describe inflammatory eruptions in the napkin area.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of napkin rash is difficult to determine because of variability between studies. Napkin rash is most commonly seen between 6 and 12 months of age and in one UK study 25% of infants aged under 1 month had an episode of nappy rash.

Aetiology

Nappy rash is caused by a number of contributory factors. Friction and maceration of the skin are key to its cause. This is compounded by excessive heat and moisture combined with the effect of faecal and urinary enzymes when in prolonged contact with the skin (faeces breakdown produces ammonia, and is considered a contributory cause, as ammonia is only irritant when in contact with damaged skin). Greater exposure of skin surfaces to moisture impairs the skin’s barrier function and makes the skin more susceptible to secondary infection.

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

The diagnosis is straight forward although identifying the cause is slightly more difficult. There are four forms of nappy rash, with irritant nappy rash being the most common. Table 9.14 highlights the key differences in symptom presentation between the four forms.

Clinical features of irritant nappy rash

The rash affects primarily the buttocks (i.e. the area in contact with the irritant) but can involve the lower abdomen, and upper thighs. The flexures, which are protected from exposure, are usually spared.

Conditions to eliminate

An environment that is wet and warm creates an ideal breeding ground for opportunistic infections. Most commonly secondary infections are caused by Candida albicans (but other pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus are involved). Candidiasis is associated with satellite lesions (i.e. away from the main skin involvement). The lesions tend to be papular or pustular.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Seborrhoeic dermatitis presents as a rash, which is bright red and confluent. The flexures are not spared and the rash can take on a diffuse, red shiny or greasy look. It is common for other sites to be involved, such as the scalp and face.

Psoriasiform napkin eruptions

Infants usually develop this form of nappy rash within the first 4 months of life. It presents as well demarcated erythematous plaques. It can show scaling that resembles psoriasis, although this is uncommon. Involvement away from the napkin area is common and affects the limbs, face and scalp. A small proportion, approximately 10%, of infants go on to develop psoriasis.

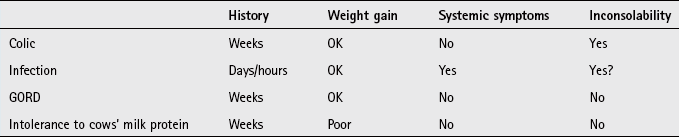

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Management centres on skin care of the nappy area by reducing skin irritation – either by removing occlusion or changing the nappy frequently; applying a protective layer of barrier cream and reducing the inflammation and/or eliminating infection.

Barrier creams are frequently used to help with irritant causes of nappy rash. They are designed to rehydrate and soothe the skin. A number of chemical constituents are formulated into barrier creams, and include silicone, antiseptics and protectorants. Many proprietary products are available and often consist of a combination of ingredients. Secondary infection with Candida can be treated with imidazole products.

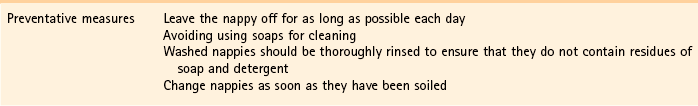

Practical prescribing and product selection

Before recommending a product it is worthwhile knowing if the nappy rash is causing the baby any obvious discomfort. Nappy rash where the child shows no sign of discomfort should be advised on skin care (see Hints and Tip Box 9.6) and be advised on the use of a barrier-type cream/protectorant. Products marketed as barrier creams/protectorants can be given to all children. They should be applied to all skin surfaces, including the skin folds after each nappy change. They have no side effects, although some products do contain potential sensitising agents and it is best to patch test an area of skin before application. Commonly prescribed products include Drapolene, Metanium and Sudocrem.

For cases causing discomfort (in general those that are secondarily infected with Candida) the use of an imidazole twice a day is recommended. Parents should be told not to use a barrier cream until the infection has settled. Where the child is distressed, and there are obvious signs of inflammation then referral is needed for steroids.

The following questions are intended to supplement the text. Two levels of questions are provided; multiple choice questions and case studies. The multiple choice questions are designed to test factual recall and the case studies allow knowledge to be applied to a practice setting.

Multiple choice questions

9.1. The common name of nits refers to:

9.2. Which antihistamine has a license for pruritus?

9.3. A high grade fever is defined as a temperature above?

9.4. Which infection is most likely to present with fever as the major symptom in children?

9.5. Fever in children with no associated symptoms or signs is usually due to:

9.6. What are the usual age children present with atopic dermatitis?

9.7. Mebendazole can be given to patients from what age?

9.8. How many days after initial treatment should a second application of insecticide be used to eradicate head lice?

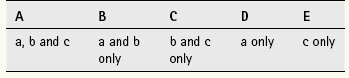

Questions 9.9 to 9.11 concern the following conditions:

Select, from A to E, which of the above conditions:

Questions 9.12 to 9.14 concern the following medicines:

Select, from A to E, which of the above medicines:

Questions 9.15 to 9.17: for each of these questions one or more of the responses is (are) correct. Decide which of the responses is (are) correct. Then choose:

9.15. Napkin dermatitis caused by an irritant presents with

9.16. Atopic dermatitis can be defined as itchy skin plus

9.17. Which statement(s) about head lice treatment is/are true

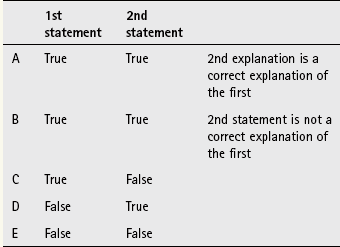

Questions 9.18 to 9.20: these questions consist of a statement in the left-hand column followed by a statement in the right-hand column. You need to:

A If both statements are true and the second statement is a correct explanation of the first statement

B If both statements are true but the second statement is NOT a correct explanation of the first statement

C If the first statement is true but the second statement is false

D If the first statement is false but the second statement is true

| First Statement | Second statement |

| 9.18 Emollients are the mainstay of treatment of atopic dermatitis | Products with lanolin should be avoided |

| 9.19 Oral temperature is the most accurate measure of temperature | Normal body temperature is 37°C |

| 9.20 Measles is vaccine preventable | It is usually given as a triple vaccine |