Dermatology

Background

The skin is the largest organ of the body. It has a complex structure and performs many important functions. These include protecting underlying tissues from external injury, overexposure to ultraviolet light, barring entry to microorganisms and harmful chemicals, acting as a sensory organ for pressure, touch, temperature, pain and vibration and maintaining the homeostatic balance of body temperature.

It has been reported that dermatological disorders account for up to 15% of the workload of UK GPs, with similar findings reported from community pharmacy. It is therefore important that community pharmacists are able to differentiate between common dermatological conditions that can be managed appropriately without referral to the GP and those that require further investigation or treatment with a prescription-only medicine.

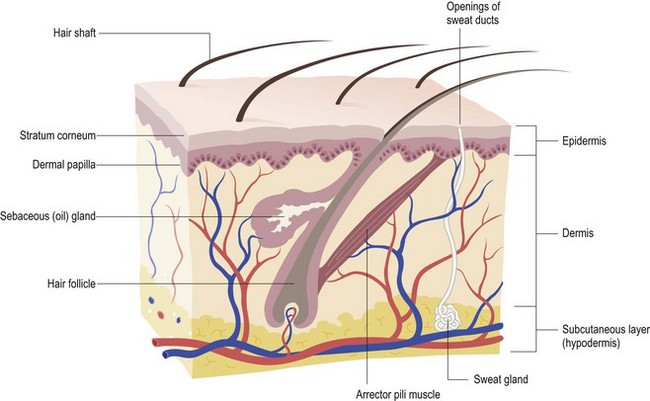

General overview of skin anatomy

Principally the skin consists of two parts, the outer and thinner layer called the epidermis and an inner, thicker layer named the dermis. Beneath the dermis lies a subcutaneous layer, known as the hypodermis (Fig. 7.1).

The epidermis

The epidermis is the major protective layer of the skin and has four distinct layers when viewed under the microscope. The basal layer actively undergoes cell division, forcing new cells to move up through the epidermis and form the outer keratinised horny layer. This process is continual and takes approximately 35 days. Pathological changes in the epidermis produce a rash or a lesion with abnormal scale, loss of surface integrity or changes to pigmentation.

The dermis

The dermis is the layer below the epidermis. The majority of the dermis is made of connective tissue; collagen for strength, and elastic fibres to allow stretch. It provides support to the epidermis as well as its blood and nerve supply. Also located in the dermis are the hair follicle, sebaceous and sweat glands and arrector pili muscle. Under cold conditions the arrector pili muscle contracts, pulling the hair in to a vertical position and causing ‘goosebumps’. Conditions of the dermis usually result in changes in the elevation of the skin, e.g. papules and nodules.

The hair

The primary function of hair is one of protection. Each hair consists of a shaft, the visible part of the hair, and a root. Surrounding the root is the hair follicle, the base of which is enlarged into a bulb structure.

Sebaceous glands

Sebaceous glands are found in large numbers on the face, chest and upper back. Their primary role is to produce sebum which keeps hair supple and the skin soft. During puberty these glands become large and active due to hormonal changes. Frequently, sebum will accumulate in the sebaceous gland, and is one of the factors that lead to acne formation.

Sweat glands

These are the most numerous of the skin glands and are classed as apocrine or eccrine. Eccrine glands are located all over the body and play a role in elimination of waste products and maintaining a constant core temperature. Apocrine sweat glands are mainly located in the axilla and begin to function at puberty.

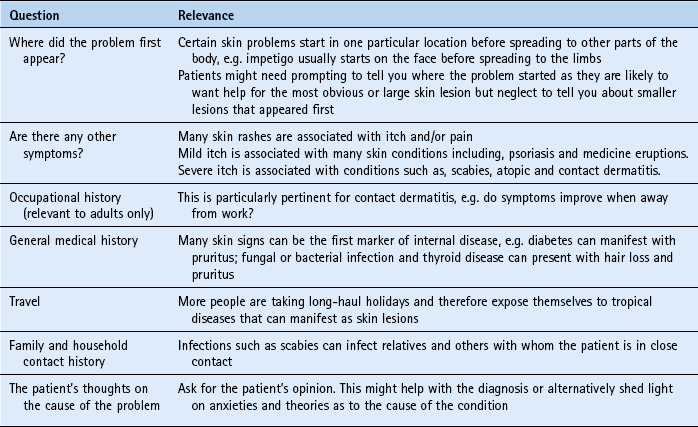

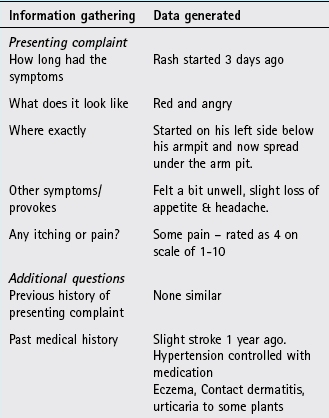

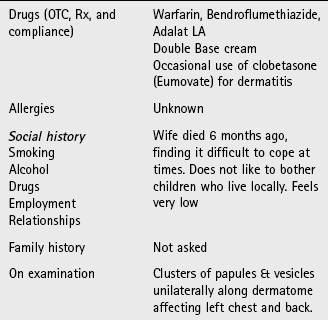

History taking

Unlike internal medicine, the majority of dermatological complaints presenting in community pharmacy can be seen. This affords the community pharmacist an excellent opportunity to base his or her differential diagnosis not only on questioning but also on physical examination. General questions that should be considered when dealing with dermatological conditions are listed in Table 7.1. Terminology describing skin lesions can be confusing and the more common terms used are shown in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2

Common terms used to describe skin lesions

| Term | Description |

| Macule | A flat lesion which is less than 1 cm in diameter |

| Patch | A flat lesion which is greater than 1 cm in diameter |

| Papule | A raised solid lesion less than 1 cm in diameter |

| Nodule | A raised solid lesion greater than 1 cm in diameter |

| Vesicle | A clear fluid filled lesion lasting a few days which is less than 1 cm in diameter |

| Bulla | A clear fluid filled lesion lasting a few days which is greater than 1 cm in diameter |

| Pustule | A pus filled lesion lasting a few days which is less than 1 cm in diameter |

| Comedone | A papule which is ‘plugged’ with keratin and sebum |

| Erythema | Redness due to dilated blood vessels that blanch when pressed |

| Excoriation | Localised damage to the skin due to scratching |

| Lichenification | Thickening of the epidermis with increased skin markings due to scratching |

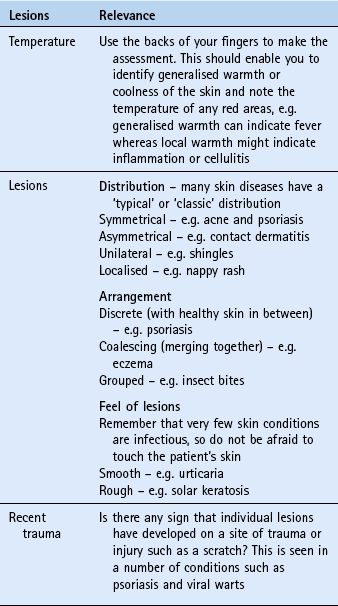

Physical examination

A more accurate differential diagnosis will be made if the pharmacist actually sees the person’s athlete’s foot or ‘rash’ on the back. Providing adequate privacy can be obtained there is no reason why the majority of skin complaints cannot be seen. If examinations are performed, clearly explain the procedure you want to perform and gain their consent. Examinations should be conducted in consultation rooms. It is worth remembering that many patients will be embarrassed by skin conditions and might be ashamed of their appearance. When performing an examination of the skin, a number of things should be looked for (Table 7.3). There is no substitute for experience when recognising skin problems. This is normally gained through seeing multiple cases; however, a free image bank (http://www.dermnet.com/) is available where familiarity can be gained of different presentations of skin conditions.

Hyperproliferative disorders

Hyperproliferative disorders are characterised by a combination of increased cell turnover rate and a shortening of the time it takes for cells to migrate from the basal layer to the outer horny layer. Typically, cell turnover rate is ten times faster than normal and cell migration takes 3 or 4 days rather than 35 days.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic relapsing inflammatory disorder characterised by a variety of morphological lesions that present in a number of forms. The commonest form of psoriasis is plaque psoriasis and will be the form most familiar to pharmacists. Depending on the extent and severity of lesions, psoriasis can have a profound affect on the person’s work and social life.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Psoriasis is a common skin disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence between 1 and 3%. In the UK it has been reported to affect 1–2% of the population. However, this is probably an underestimate, as many patients with mild psoriasis do not present to their GP.

Psoriasis can present at any time in life, although it appears to be more prevalent in the second and fifth decade. It is rare in infants and uncommon in children. The sexes are equally affected but it is more common in Caucasians.

Aetiology

The exact aetiology of psoriasis still remains unclear but it is known that inherited factors are important. For example, if the patient has one parent with psoriasis then they have a 25 to 30% chance of developing psoriasis and if both parents suffer from psoriasis then the figure rises to 50–60%. However, studies in twins also suggest that environmental factors might be needed for clinical expression of the disease because only 70% of genetically identical twins both develop the condition. Studies have identified a region on chromosome 6 as a contributor to psoriasis susceptibility (known as PSORS1) and has been associated with at least 50% of psoriasis cases in several populations.

Psoriasis lesions also develop at sites of skin trauma, such as sunburn and cuts (known as the Koebner phenomenon), following streptococcal throat infection and during periods of stress.

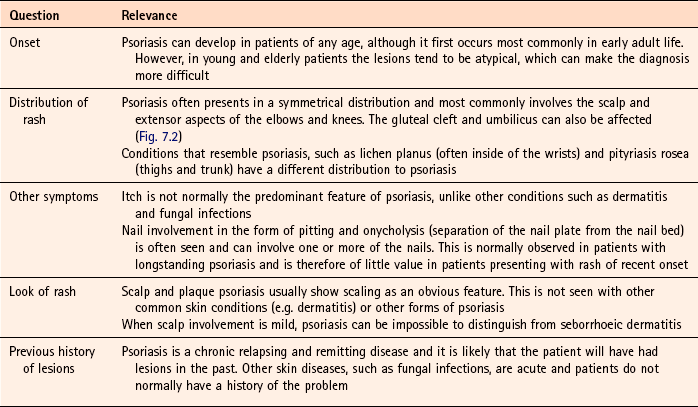

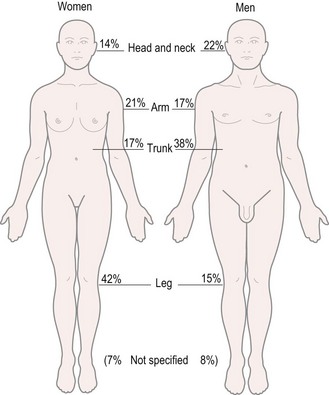

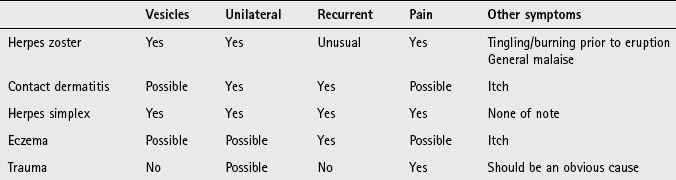

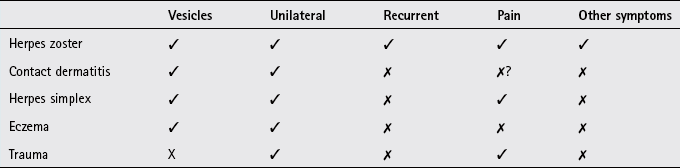

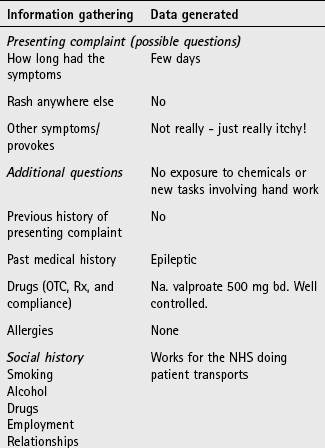

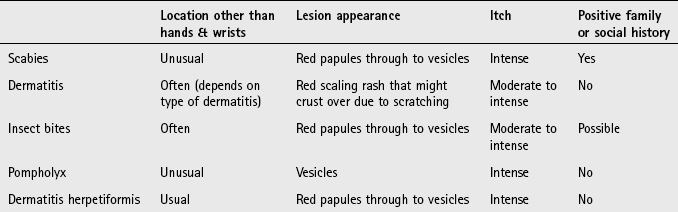

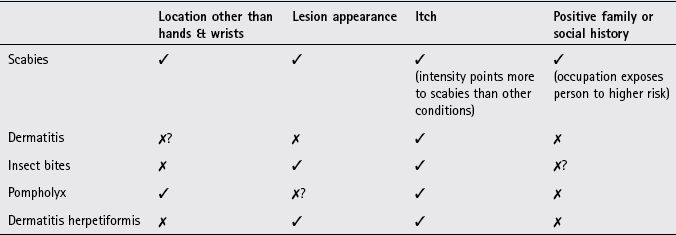

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

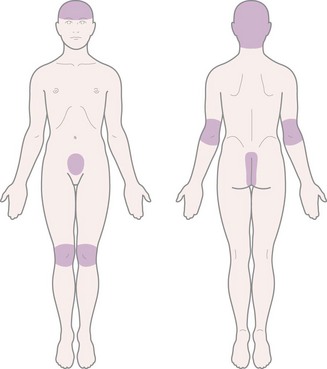

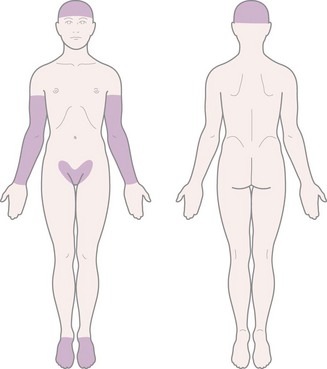

Psoriasis can be located on various parts of the body (Fig. 7.2) and presents in a variety of different forms. Plaque and scalp psoriasis are the only forms of the condition that can be managed by the community pharmacist. It is therefore necessary that other forms of psoriasis, and conditions that look like psoriasis, can be recognised and distinguished. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 7.4).

Clinical features of plaque psoriasis

Plaque psoriasis classically presents with characteristic salmon-pink lesions with slivery-white scales and well defined boundaries (Fig. 7.3). Lesions can be single or multiple and vary in size from pinpoint to covering extensive areas. If the scales on the surface of the plaque are gently removed and the lesion is then rubbed, it reveals pinpoint bleeding from the superficial dilated capillaries. This is known as the Auspitz’ sign and is diagnostic.

Clinical features of scalp psoriasis

Scalp psoriasis can be mild, exhibiting slight redness of the scalp through to severe cases with marked inflammation and thick scaling (Fig. 7.4). The redness often extends beyond the hair margin and is commonly seen behind the ears.

Conditions to eliminate for plaque psoriasis

In this rare form of psoriasis sterile pustules are an obvious clinical feature. The pustules tend to be located on the advancing edge of the lesions and typically occur on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet (Fig. 7.5).

Seborrhoeic psoriasis (also known as flexural psoriasis)

Seborrhoeic psoriasis refers to classic lesions that affect the scalp but with less typical lesions (lack scaling) in the body folds, especially the groins and axillae. Often, in mild cases the scalp might be the only part of the body involved. Itch, in this form, can be prominent.

Guttate psoriasis (also known as raindrop psoriasis)

Guttate psoriasis is characterised by crops of scattered small lesions (less than 1 cm) covered with light flaky scales that often affects the trunk and proximal part of the limbs (Fig. 7.6). This form of psoriasis usually occurs in adolescents and often follows a streptococcal throat infection and in people genetically predisposed to psoriasis. The condition is usually self-limiting.

Erythrodermic psoriasis

Erythrodermic psoriasis presents as an extensive erythema and shows very few classical lesions. It is therefore difficult to diagnosis. The condition is serious and can even be life threatening. Systemic symptoms can be severe and include fever, joint pain and diarrhoea. Patients are extremely unlikely to present at a community pharmacy.

Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis can superficially look like plaque psoriasis. For further information on tinea infection see page 210.

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is an uncommon condition and is reported to only account for 0.2 to 0.8% of dermatological outpatient consultations. The lesions are similar in appearance to plaque psoriasis but are itchy and are normally located on the inner surfaces of the wrists and on the shins, an atypical distribution for psoriasis. Additionally, oral mucous membranes are normally affected with white, slightly raised lesions that look a little like a spider’s web. The person will not have a family history of psoriasis.

Pityriasis rosea

The condition is characterised by erythematous scaling mainly on the trunk, but also on the thighs and upper arms. The colour of the rash tends to be a lighter pink colour than psoriasis and can be mildly itchy. A ‘target’ disc lesion, often misdiagnosed as ringworm, is followed 1 week later with an extensive rash. It most commonly affects young adults. The condition usually remits spontaneously after 4 to 8 weeks. An accurate history will normally eliminate pityriasis rosea from psoriasis, as the condition is acute in onset and the patient can often identify the initial ‘target’ lesion.

Medication-exacerbated psoriasis

A number of medicines can worsen or aggravate existing psoriasis. Medication most commonly associated are lithium, antimalarials and beta-blockers. Other less commonly implicated include digoxin, amiodarone, clonidine, penicillin, tetracycline, terbinafine, bupropion and sulphonamides. In addition systemic corticosteroids have been shown to induce flares in psoriasis patients.

Conditions to eliminate for scalp psoriasis

Mild scalp psoriasis can be very difficult to distinguish from seborrhoeic dermatitis. However, in practice this is rarely a problem since treatment for both conditions is often the same. For further information on seborrhoeic dermatitis see page 207.

Tinea capitis (fungal infection of the scalp)

Tinea capitis is an uncommon infection but if the patient has scaling skin, broken hairs and a patch of alopecia then a tinea infection should be considered.

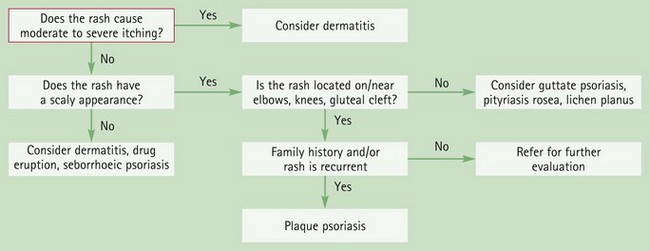

Figure 7.7 will aid in the differentiation of plaque psoriasis.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Before any treatment is offered to the patient it is first worth noting that simple OTC remedies should be limited to mild to moderate plaque psoriasis and scalp psoriasis, as these are most likely to respond to such measures. A patient who presents with severe plaque psoriasis or another form of psoriasis should be referred.

Any treatment recommended should also be in conjunction with patient education. Reassurance should be given about its benign, non-contagious nature but it should be emphasised that the condition is chronic and long-term that has periods of remission and relapse.

Treatment OTC is limited to the use of emollients, keratolytics, coal tar (or dithranol), although there is limited published literature supporting efficacy of these treatments. Other topical treatments and systemic agents available on prescription have evidence of efficacy if OTC options are ineffective. A future candidate for deregulation to Pharmacy status is calcipotriol (Dovonex) as it has proven efficacy for mild to moderate plaque psoriasis and has few side effects.

Emollients

No published literature appears to have addressed either emollient efficacy or whether one emollient is superior to another in treating psoriasis. Subjective evidence over a long period of time has shown that emollients are useful and are an important aspect of psoriasis treatment. Emollients are frequently prescribed and used to help soften scaling and soothe the skin so reducing irritation, cracking and dryness. On current evidence there is no way of knowing if one emollient is superior to another. Patients might have to try several emollients before finding one that is most effective for their skin.

Keratolytics

Keratolytics, such as salicylic acid and lactic acid have been incorporated into emollients to aid clearing scale and are often used for scalp psoriasis where very thick scaling can occur. Although there appears to be no published evidence for their efficacy in clearing scale, clinical practice suggests that they should be used first when significant scaling is present before using other treatments.

Coal tar

Goeckerman demonstrated the effectiveness of coal tar as early as 1925. This remained the mainstay of treatment until the introduction of dithranol, corticosteroids, and more recently, vitamin D and A analogues. A number of clinical studies have confirmed the beneficial effect coal tar has on psoriasis, although a major drawback in assessing the effectiveness of coal tar preparations is the variability in their composition making meaningful comparisons between studies difficult. Comparisons between coal tar and other treatment regimens have been conducted. Tham et al (1994) compared the effectiveness of calcipotriol 50 µg twice daily versus 15% coal tar solution each day. Both treatments were shown to be effective, although calcipotriol was significantly better than the coal tar solution. Harrington (1989) compared two pharmacy-only products, Psorin and Alphosyl. Findings showed that both helped in the treatment of psoriasis but Psorin (which includes 0.11% dithranol) was significantly more effective.

Dithranol

Dithranol was first used in the 1950s and has become an established treatment option as clinical trials have established its efficacy. A systematic review in 2009 identified three placebo-controlled trials with dithranol, all demonstrating a statistically significant improvement over placebo (Mason et al 2009). There appears to be no definitive answer as to which strength is most appropriate, however, current practice dictates starting on the lowest possible concentration and gradually increasing the concentration until improvement is noticed. In addition, short contact regimens are advocated. However, one review of published studies involving short-contact dithranol therapy concluded that due to methodological flaws in many of the trials it is impossible to objectively determine the efficacy of this regimen (Naldi et al 1992).

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to the medicines used to treat psoriasis discussed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is summarised in Table 7.5; useful tips relating to patients presenting with psoriasis are given in Hints and Tips Box 7.1.

Emollients

All emollients should be regularly and liberally applied with no upper limit on how often they can be used. All are chemically inert and can therefore be safely used from birth onwards by all patients. They do not have any interactions with other medicines. For more information on emollients see page 242.

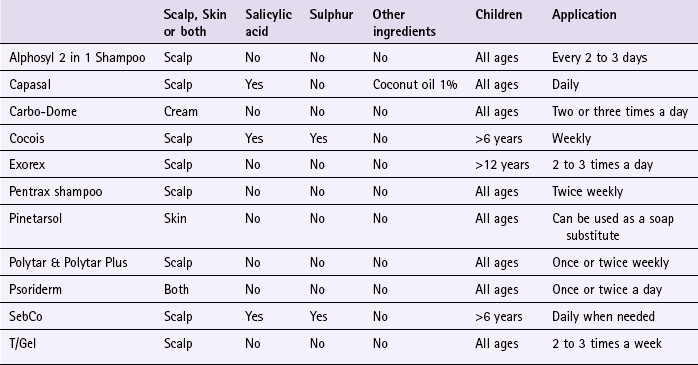

Tar-based products

All patient groups, including pregnant and breastfeeding women, can use the majority of products on either the skin or scalp. They have no drug interactions but can cause local skin or scalp irritation and stain skin and clothes. There has been recent concern over topical tar products association with an increased risk of skin cancer, although there is at present no firm epidemiological evidence (http://www.bad.org.uk/site/1114/default.aspx; accessed 13 November 2012).

Dithranol (e.g. Dithrocream)

Dithranol preparations are pharmacy-only medicines so long as the strength does not exceed a maximum of 1.0%. Although dithranol has evidence of efficacy, recommendation is not advocated in a pharmacy context due to its adverse effects, even at low concentrations. When used, short-contact therapy is often advocated because prolonged exposure can lead to irritation and burning skin. This involves using the lowest strength for the shortest period, which controls symptoms.

References

Harrington, CI. Low concentration dithranol and coal tar (Psorin) in psoriasis: a comparison with alcoholic coal tar extract and allantoin (Alphosyl). Br J Clin Pract. 1989;43:27–29.

Mason, AR, Mason, J, Cork, M, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. [Issue 2. Art. No.: CD005028. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005028.pub2].

Naldi, L, Carrel, CF, Parazzini, F, et al. Development of anthralin short-contact therapy in psoriasis: survey of published clinical trials. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:126–130.

Tham, SN, Lun, KC, Cheong, WK. A comparative study of calcipotriol ointment and tar in chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:673–677.

Clark, C. Psoriasis: first-line treatments. Pharm J. 2004;274:623–626.

Dodd, WA. Tars. Their role in the treatment of psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:131–135.

Freeman, K. Psoriasis: not just a skin disease. The Prescriber. 2007;5th June:42–45. 49

Gelfand, JM, Weinstein, R, Porter, SB, et al. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1537–1541.

Leary, MR, Rapp, SR, Herbst, KC, et al. Interpersonal concerns and psychological difficulties of psoriasis patients: effects of disease severity and fear of negative evaluation. Health Psychol. 1998;17:530–536.

MacKie, RM. Clinical Dermatology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1999.

Nevitt, GJ, Hutchinson, PE. Psoriasis in the community: prevalence, severity and patients’ beliefs and attitudes towards the disease. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135(4):533–537.

Scon, P, Henning-Boehncke, W, Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1899–1912.

Tristani-Firouzi, P, Kruegger, CG. Efficacy and safety of treatment modalities for psoriasis. Cutis. 1998;61:11–21.

The Psoriasis Association. http://www.psoriasis-association.org.uk/

Psoriatic Arthropathy Alliance. http://www.paalliance.org/

Dandruff (pityriasis capitis)

Background

Dandruff is a chronic relapsing non-inflammatory hyperproliferative skin condition that is often seen as socially unsightly and a source of embarrassment. Consequently, there are many products marketed to help with the problem.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Dandruff is very common and affects both sexes and all age groups, although it is unusual in pre-pubescent children. It has been estimated to affect 1–3% of the population (Gupta et al, 2004).

Aetiology

Increased cell turnover rate is responsible for dandruff but the reason why cell turnover increases is unknown. Increasingly, research has focused on the role that micro-organisms have on the pathogenesis of dandruff, and in particular the yeast Malassezia (previously known as Pityrosporum) ovale, although the evidence is inconclusive as to whether M. ovale is the primary cause of dandruff or is a contributory factor. It has been shown that M. ovale makes up more of the scalp flora of dandruff sufferers and might explain why dandruff improves in the summer months (fungal organisms thrive in warm and moist environments that exist on the scalp due to wearing of hats and caps). Further evidence to support a role of M. ovale in the aetiology of dandruff is the positive effect that antifungal therapy has on the resolution of dandruff.

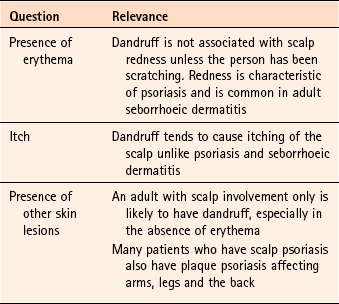

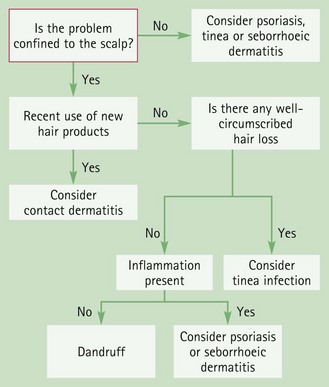

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Most patients will diagnose and treat dandruff without seeking medical help. However, for those patients that do ask for help and advice it is important to differentiate dandruff from other scalp conditions. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 7.6).

Clinical features of dandruff

The scalp will be dry, itchy and flaky. Flakes of dead skin are usually visible in the hair close to the scalp and are visible on the shoulders and collars of clothing.

Conditions to eliminate

Typically, seborrhoeic dermatitis will affect areas other than the scalp. In adults, the trunk is commonly involved, as are the eyebrows, eyelashes and external ear. If only scalp involvement is present then the patient might complain of severe and persistent dandruff and the skin of the scalp will be red. For further information on seborrhoeic dermatitis see page 207.

Contact dermatitis

Enquiry should be made to the use of new hair products such as dyes and perms. These can cause irritation and scaling. Avoidance of the irritant should see an improvement in the condition. If improvement is not observed after avoidance of 1 to 2 weeks then a re-assessment of the condition is needed.

Tinea capitis

If the problem is persistent and associated with hair loss then fungal infection of the scalp should be considered.

Figure 7.8 will aid the differentiation of dandruff from other scalp disorders.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

The use of a hypoallergenic shampoo on a daily basis will usually control mild symptoms. In more persistent and severe cases a ‘medicated’ shampoo can be used to control the symptoms. Treatment options include coal tar, selenium sulphide, zinc pyrithione and ketoconazole.

Coal tar

The mechanism of action for crude coal tar in the management of dandruff is unclear, although it appears that tars affect DNA synthesis and have an antimitotic effect. There are virtually no published studies in the literature to assess the efficacy of coal tars in the treatment of dandruff. A review in Clinical Evidence identified one study comparing coal tar to placebo (Manrìquez & Uribe 2007). The study involving 111 people with seborrhoeic dermatitis or dandruff found coal tar reduced dandruff scores and redness compared to placebo at 29 days. Despite the lack of evidence, tar derivatives are found in a plethora of OTC medicated shampoos and have been granted FDA approval in America as an antidandruff agent.

Selenium sulphide

Selenium is thought to work by its antifungal action. It is accepted that selenium is effective as an antidandruff agent and studies have shown it to be significantly better than placebo and non-medicated shampoos.

Zinc pyrithione

Zinc pyrithione, like selenium, exhibits antifungal properties but also reduces cell turnover rates. It is believed that one or both of these properties confers its effectiveness in treating dandruff. Few trials have been conducted with zinc pyrithione although trials have shown significant improvement in dandruff severity scores.

Ketoconazole

Ketoconazole, an azole antifungal, inhibits M. ovale replication by interfering with cell membrane formation. It helps in controlling the itching and flaking associated with dandruff. Studies have shown it to be an effective treatment. It has been demonstrated that ketoconazole is significantly better than zinc pyrithione and has similar efficacy to selenium, although it is better tolerated than selenium. Ketoconazole has also been shown to act as a prophylactic agent in preventing relapse.

In addition to the ingredients listed, salicylic acid is an ingredient in some combined products (e.g. Capasal and Meted) and included for its keratolytic properties, although trials are lacking to substantiate its effect.

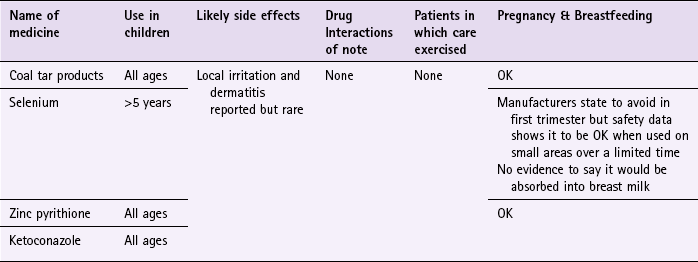

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to the specific products used to treat dandruff and discussed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 7.7; useful tips relating to dandruff shampoo are given in Hints and Tips Box 7.2.

All antidandruff shampoos can cause local scalp irritation. If this is severe the product should be discontinued. Any patient group can use them, although some manufacturers state products should be avoided during the first 3 months of pregnancy. However, there appears to be no data to substantiate this precaution during pregnancy.

Coal tar products

Products containing coal tar are discussed under practical prescribing for psoriasis. For further information on coal tar products see page 203.

Selenium sulphide (e.g. Selsun)

Adults and children over the age of 5 should use the product twice a week for the first 2 weeks and then once a week for the next 2 weeks. The hair should be thoroughly wet before applying the shampoo and left in contact with the scalp for 2 to 3 minutes before rinsing out. Selenium should be avoided if the patient has inflamed or broken skin because irritation can occur. Selenium can also cause discolouration of the hair and alter the colour of hair dyes.

Zinc pyrithione (e.g. Head and Shoulders)

Zinc-based products can be used by all patients and at any age. It should be used on a daily basis until dandruff clears. Dermatitis has been reported with zinc pyrithione and should be borne in mind when treating patients with pre-existing dermatitis.

Ketoconazole (Nizoral Dandruff and Nizoral Anti-Dandruff Shampoo)

Nizoral can either be used to treat acute flare-ups of dandruff or as prophylaxis. To treat acute cases adults and children should wash the hair thoroughly, leaving the shampoo on for 3 to 5 minutes before rinsing it off. This should be repeated every 3 or 4 days (twice a week) for between 2 and 4 weeks. If used for prophylaxis, the shampoo should be used once every 1 to 2 weeks. It can cause local itching or a burning sensation on application and may rarely discolour hair.

References

Gupta, AK, Batra, R, Bluhm, R, et al. Skin diseases associated with Malassezia species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:785–798.

Manriquez, JJ, Uribe, P, Seborrhoeic dermatitis. 2007. Clinical Evidence. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. www.clinicalevidence.com

Arrese, JE, Pierard-Franchimont, C, De-Doncker, P, et al. Effect of ketoconazole-medicated shampoos on squamometry and Malassezia ovalis load in pityriasis capitis. Cutis. 1996;58:235–237.

Danby, FW, Maddin, WS, Margesson, LJ, et al. A randomized double-blind controlled trial of ketoconazole 2% shampoo versus selenium sulfide 2.5% shampoo in the treatment of moderate to severe dandruff. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:1008–1012.

Nigam, PK, Tyagi, S, Saxena, AK, et al. Dermatitis from zinc pyrithione. Contact Dermatitis. 1988;19:219.

Orentreich, N. Comparative study of two antidandruff preparations. J Pharm Sci. 1969;58:1279–1284.

Pereira, F, Fernandes, C, Dias, M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from zinc pyrithione. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:131.

Peter, RU, Richarz-Barthauer, U. Successful treatment and prophylaxis of scalp seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff with 2% ketoconazole shampoo: Results of a multicentre, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:441–445.

Pierard-Franchimont, C, Goffin, V, Decroix, J, et al. A multicenter randomized trial of ketoconazole 2% and zinc pyrithione 1% shampoos in severe dandruff and seborrhoeic dermatitis. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol. 2002;15(6):434–441.

Rigoni, C, Toffolo, P, Cantu, A, et al. 1% econazole hair shampoo in the treatment of pityriasis capitis; a comparative study versus zinc pyrithione shampoo. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1989;124:67–70.

Van Custem, J, Van Gerven, F, Fransen, J, et al. The in vitro antifungal activity of ketoconazole, zinc pyrithione and selenium sulfide against Pityrosporum and their efficacy as a shampoo in the treatment of experimental pityrosporosis in guinea pigs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:993–998.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Background

There are two distinct types of seborrhoeic dermatitis: an infantile form, often referred to as cradle cap, and an adult form. Seborrhoeic dermatitis can present with varying degrees of severity, ranging from mild dandruff to a severe and explosive form in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Estimates of the prevalence of clinically significant seborrhoeic dermatitis range from 1 to 5% of the population, although cradle cap is reported to be more prevalent than the adult form (Naldi & Rebora 2009). Cradle cap usually starts in infancy, before the age of 6 months and is usually self-limiting; the adult form tends to be chronic and persistent. Seborrhoeic dermatitis is more common in adult men than women, and also more common in people with underlying neurological illness, for example, Parkinson’s disease (Johnson & Nunley 2000).

Aetiology

Despite its name, there appears to be no changes in sebum secretion. Like psoriasis and dandruff, seborrhoeic dermatitis is characterised by an increased cell turnover rate. The precise cause of seborrhoeic dermatitis remains unknown and several theories have been put forward, ranging from immunological, hormonal and nutritional mechanisms. Like dandruff, Malassezia ovale plays an important role in the development of seborrhoeic dermatitis; however, it has not yet been established whether it has a primary or secondary role in the clinical presentation of seborrhoeic dermatitis.

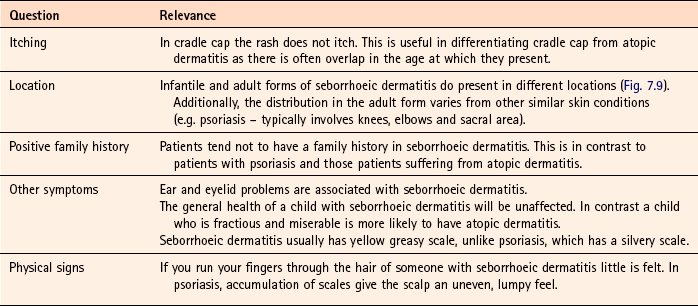

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Infantile seborrhoeic dermatitis is relatively easy to recognise but can sometimes be confused with atopic dermatitis. Arriving at a differential diagnosis of the adult form is more problematic as the condition can affect different areas and present with different degrees of severity. In mild cases it needs to be differentiated from dandruff and in more severe forms from allergic contact dermatitis, psoriasis and pityriasis versicolor. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 7.8).

Clinical features of seborrhoeic dermatitis

Cradle cap appears as large yellow, greasy scales and crusts on the scalp. This can become thick and cover the whole scalp (Fig. 7.10). Other areas can be involved such as the face and napkin area.

Fig. 7.10 Infantile seborrhoeic dermatitis. Reproduced from R Kliegman, R E Behrman, W Emerson Nelson and H B Jenson, 2007, Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, Saunders Elsevier with permission.

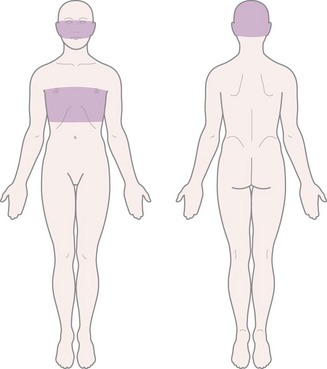

The adult form of seborrhoeic dermatitis is characterised by a history of intermittent skin problems. The distribution of rash is synonymous with skin areas with high numbers of sebaceous glands, typically the central part of the face, scalp, eyebrows, eyelids, ears, nasolabial folds and mid chest (Fig. 7.11). The rash is red with greasy looking scales and is mildly itchy. Blepharitis and otitis externa are also common secondary complications.

Conditions to eliminate

In infants, atopic dermatitis usually presents as itchy lesions on the face and trunk. Scalp involvement is less common and the nappy area is usually spared. A positive family history of the atopic triad of dermatitis, asthma or hay fever is common. For further information on differentiating atopic dermatitis see page 291.

Psoriasis

Adults with scalp psoriasis can be confused with those patients who present with severe and persistent dandruff caused by seborrhoeic dermatitis. However, in scalp psoriasis the plaques tend to be crusty and extend away from the hairline where as seborrhoeic dermatitis causes scaling with underlying redness. It also affects the eyebrows and eyelids, unlike psoriasis.

Pityriasis versicolor (meaning bran-like scaly rash of various colour)

Pityriasis versicolor, a yeast infection, can be mistaken for adult seborrhoeic dermatitis because the lesions exhibit fine superficial scale and are located on the upper trunk. The lesions are usually small (less than 1 cm) but can join together to form larger plaques. The condition is associated with warm climates and most people will have picked the infection up when on holiday. The rash does not itch significantly and the face is usually spared. It can be treated with antifungal lotions and shampoos (see Dandruff page 206), or if a small number of lesions with imidazole creams (see Fungal infections page 213). Antifungal shampoos such as ketoconazole, and selenium sulphide (2.5%) are applied for 10 minutes and then washed off, and this is repeated daily for 10 days. Imidazole creams are applied daily for 10 days.

Rosacea

Rosacea predominately affects the face – an area usually involved in adult seborrhoeic dermatitis. For more information on rosacea see page 233 under the acne section.

Medication that can trigger or aggravate seborrhoeic dermatitis

A number of medicines are associated with triggering or aggravating existing seborrhoeic dermatitis. These include: buspirone, cimetidine, gold, griseofulvin, haloperidol, interferon alfa, lithium, methyldopa and phenothiazines.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Treatment options for seborrhoeic dermatitis are the same as dandruff. Unfortunately, seborrhoeic dermatitis tends to be more resistant to therapy and often recurs whatever treatment is chosen.

For infants with cradle cap simple measures are usually only required in most cases. Daily use of a baby shampoo followed by gentle brushing will improve the condition. If this fails, the scales can be removed by applying olive oil to the scalp overnight followed by using a baby shampoo the next morning. If symptoms persist a medicated shampoo containing a keratolytic (e.g. Meted) or keratolytic-tar combination (e.g. Capasal) could be tried. If this fails the child should be referred to the GP.

In adults, OTC preparations should only be used on mild to moderate seborrhoeic dermatitis involving the scalp. In mild cases of scalp involvement zinc pyrithione can be tried, reserving selenium and ketoconazole for resistant or more moderate disease. For involvement on the face and torso antifungals and corticosteroids are effective but OTC product licences preclude their use.

Bergbrant, IM, Faergemann, J. The role of Pityrosporum ovale in seborrheic dermatitis. Semin Dermatol. 1990;9:262–268.

Danby, FW, Maddin, WS, Margesson, LJ, et al. A randomized double-blind controlled trial of ketoconazole 2% shampoo versus selenium sulfide 2.5% shampoo in the treatment of moderate to severe dandruff. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:1008–1012.

Go, IH, Wientjens, DP, Koster, M. A double-blind trial of 1% ketoconazole shampoo versus placebo in the treatment of dandruff. Mycoses. 1992;35:103–105.

Gupta, AK, Bluhm, R. Seborrhoeic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:13–26.

McGrath, J, Murphy, GM. The control of seborrhoeic dermatitis and dandruff by antipityrosporal drugs. Drugs. 1991;41:178–184.

Fungal skin infections

Background

Two main groups of fungi infect man: Candida yeasts and the dermatophytes. However, in this section only dermatophyte infections are considered. Fungal infections are commonly and inaccurately referred to as ringworm. Dermatophyte skin infections are classed by anatomical location, for example: Athlete’s foot (tinea pedis); groin infection (tinea cruris or ‘jock itch’); ‘ringworm’ of the skin (tinea corporis) and scalp ‘ringworm’ (tinea capitis).

Prevalence and epidemiology

Globally, dermatophytic fungi are more prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas because fungal organisms prefer high temperatures and high humidity. Having said this, dermatophyte infections are commonly met in more temperate Western countries. Tinea pedis (athlete’s foot) is the most common fungal infection, although prevalence rates vary depending on the population studied and whether diagnosis is made by clinical symptoms or culture confirmation. Athlete’s foot is said to affect about 15% of the UK population and is common in people of all ages.

Other tinea infections such as tinea corporis and tinea cruris might present in the community pharmacy but are uncommon Tinea unguium (nail infection) is covered separately on page 216. Tinea capitis is the commonest infection in children Worldwide but in Western nations is rare (for further information on fungal scalp infection see page 203).

Aetiology

Dermatophyte infections are contagious and transmitted directly from one host to another. They invade the stratum corneum of the skin, hair and nails but do not generally infiltrate living tissues. The fungus then begins to grow and proliferate in the non-living cornified layer of keratinised tissue of the epidermis. Transmission of athlete’s foot is thought to be commonly acquired from communal rooms (e.g. changing rooms) whereas infection of the groin can be acquired from contaminated towels and bed sheets, or by autoinoculation from an existing foot infection.

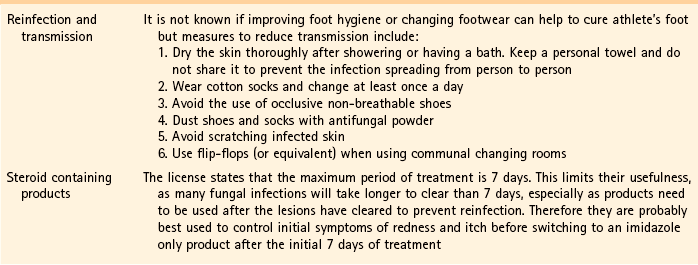

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Dependent on the area affected the infection will manifest itself in a variety of clinical presentations (Fig. 7.12). Recognition of symptoms for each site affected will facilitate recognition and accurate diagnosis. All forms of tinea infection should be relatively easy to recognise, perhaps with the exception of isolated lesions on the body.

Patients with athlete’s foot will often accurately self-diagnose the condition. However, the pharmacist should still confirm this self-diagnosis through a combination of questions (Table 7.10) and inspection of the feet. This is important as it also provides an opportunity to check for fungal nail involvement.

Clinical features of tinea infections

Athlete’s foot is characterised by itching, flaking and fissuring of the skin and will appear white and ‘soggy’ due to maceration of the skin (Fig. 7.13). The feet often smell. The usual site of infection is in the toe webs, especially the fourth web space (web space next to the little toe).

Fig. 7.13 Athlete’s foot. Reproduced from AB Fleischer et al 2000, 20 Common Problems, with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies.

Once acquired the infection can spread to other sites including the sole and instep of the foot. Over time this can infect the nails (see page 216 for fungal nail infection). Cases of tinea infection where the plantar surface has become involved may be persistent and difficult to treat.

Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis is defined as an infection of the major skin surfaces that do not involve the face, hands, feet, groin or scalp. The usual clinical presentation is of itchy pink or red scaly slightly raised patches with a well-defined inflamed border (Fig. 7.14). Over time the lesions often show ‘central clearing’ as the central area is relatively resistant to colonisation. This appearance led to the term ringworm. Lesions can occur singly, be numerous or overlap to produce a single large lesion and appear polycyclic (several overlapping circular lesions).

Conditions to eliminate

Fungal infections on the face are rare and are consequently often mistaken for other facial skin conditions. The lesions are similar in appearance to tinea corporis in that they will normally have a sharp well-defined border, show scaling and be itchy. Conditions such as acne, rosacea and lupus need to be considered in its differential diagnosis.

Tinea manuum

Tinea manuum is often misdiagnosed as eczema or psoriasis due to its atypical tinea appearance. The patient usually suffers from chronic diffuse scaling of one palm. Often athlete’s foot will be present, as the infection has spread to the hands from the feet due to the patient scratching their feet. The condition is not common and if no foot involvement is implicated then the diagnosis strongly points to dermatitis.

Psoriasis

Isolated fungal body lesions can be difficult to distinguish from plaque psoriasis. However, if the patient has psoriasis there will normally be a family history of psoriasis and the lesions tend not to itch, exhibit more scaling and do not show central clearing.

Dermatitis-allergic and contact forms

Both fungal infections and dermatitis exhibit red itchy lesions and therefore can be difficult to distinguish from one another. Patients with dermatitis will often have a family and personal history of dermatitis or be able to describe an event that triggered the onset of the rash. Misdiagnosis of a fungal infection for dermatitis and subsequent treatment with a steroid-based cream will diminish the itch, redness and scaling but the infecting organism will proliferate. On withdrawal of the steroid cream the visible signs of the infection will return and be worse than before, often in a papular form (tinea incognito).

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Superficial dermatophyte infections can be treated effectively with topical OTC preparations. Six classes of medicines have proven efficacy in their treatment.

Allylamines

Terbinafine has been exempt from POM control in the UK since 2000. It inhibits the biosynthesis of ergosterol – an essential component of fungal cell membranes. Reviews have shown terbinafine to have high cure rates, slightly better than the imidazoles (Crawford & Hollis 2007).

Benzoic acid

Benzoic acid acts by lowering intracellular pH of dermatophytes and is combined with salicylic acid (Whitfield’s ointment). Although Whitfield’s ointment has been on the market for nearly a century it still has a role to play as an effective antifungal, but newer products, with higher cure rates, quicker resolution and more cosmetically acceptable formulations have replaced its widespread use in Western society.

Imidazoles

Imidazoles, like allylamines, act by inhibiting ergosterol production but at a later stage in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway. They have largely replaced benzoic acid, undecenoates and tolnaftate, because they have greater efficacy and an excellent safety record (Crawford & Hollis 2007). There appears to be no clinically significant differences in cure rates between the different imidazoles and treatment choice will probably be driven by patient acceptability and cost.

Griseofulvin

Griseofulvin (as a 1% spray) works by inhibiting cellular mitosis. It has proven effectiveness when taken orally but has only limited trial data as a topical formulation. One trial reported an 80% mycological cure rate after 4 weeks with once daily application (Aly et al 1994).

Tolnaftate

Tolnaftate is thought to work by distorting fungal hyphae. It appears to have the least amount of trial data supporting its efficacy. Low patient numbers involved in the studies further compounds the difficulty in assessing its efficacy.

Undecenoates

The exact mechanism of action for undecenoates is not understood. They have been used to treat athlete’s foot for over 30 years and features in the most recent United States Pharmacopoeia. In a recent Cochrane review, undecenoic acid was said to be efficacious in treating fungal infections for skin and nail infections of the foot (Crawford & Hollis 2007).

Summary

On current evidence, an imidazole or terbinafine would be first-line treatment for superficial fungal infection. Both have similar mycological and symptom cure rates, although terbinafine might be preferred because it clears symptoms in a shorter space of time, although it is more expensive.

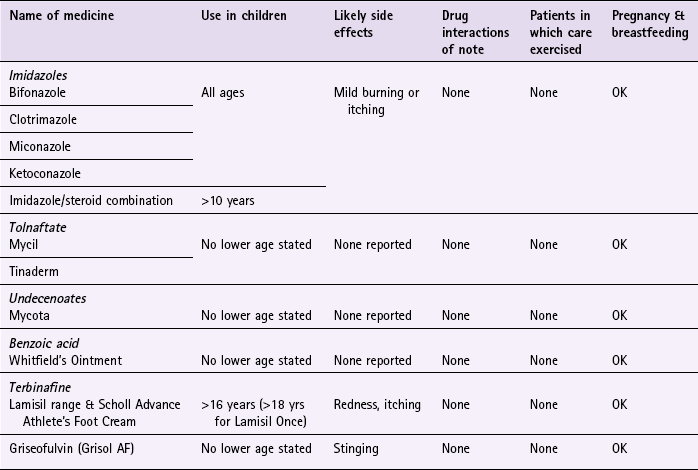

Practical prescribing and product selection

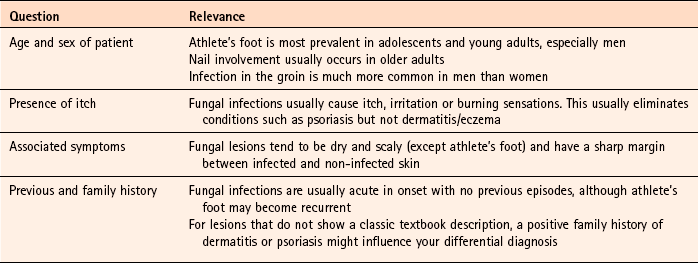

Prescribing information relating to specific products used to treat fungal infections and discussed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is summarised in Table 7.11 and products available summarised in Table 7.12; useful tips relating to patients presenting with fungal infections are given in Hints and Tips Box 7.3.

Table 7.12

Summary of antifungal products and formulations

| Active ingredient | Brand | Formulations |

| Bifonazole | Canesten Bifonazole Once Daily | Cream |

| Clotrimazole 1% | Canesten AF | Cream, spray |

| Canesten | Cream, spray, solution | |

| Clotrimazole 1% & Hydrocortisone 1% | Canesten Hydrocortisone | Cream |

| Miconazole 2% | Daktarin Activ | Cream, spray, powder |

| Daktarin | Cream and powder | |

| Miconazole 2% & hydrocortisone 1% | Daktacort Hydrocortisone | Cream |

| Ketoconazole | Daktarin Gold | Cream |

| Terbinafine | Lamisil AT | Spray, cream, gel |

| Lamisil Once | Solution | |

| Scholl Advance Athlete’s Foot Cream | Cream | |

| Tolnaftate | Mycil | Ointment, spray, powder |

| Scholl Athlete’s foot | Cream, spray, powder | |

| Tinaderm | Cream | |

| Undecenoic acid | Mycota | Cream, spray, powder |

Imidazoles

All topical imidazoles have excellent safety records and can be used by all patient groups, including pregnant and breastfeeding women. They do not have any drug interactions and the major side effect associated with their use is irritation on application. To prevent reinfection, imidazoles should be used after the lesions have cleared, although, the length of time varies from product to product.

Clotrimazole (e.g. Canesten range): Clotrimazole-containing products can be used for all dermatophyte and candida infections. Canesten and Canesten AF cream should be applied two or three times a day, where as Canesten Hydrocortisone can only be used twice a day.

Bifonazole (Canesten Bifonazole Once Daily 1% w/w Cream): Bifonazole is licensed for athlete’s foot. For all patients the cream should be applied once daily.

Ketoconazole (Daktarin Gold): Ketoconazole has a license for athlete’s foot, groin infection and candidal intertrigo. For athlete’s foot the cream should be applied twice a day for 1 week. For groin infections and candidal intertrigo, the cream should be applied once or twice daily. If no improvement in symptoms is experienced after 4 weeks treatment then the patient should be referred to the GP. For all conditions treatment should be continued for 2 to 3 days after all signs of infection have disappeared to prevent relapse.

Miconazole (e.g. Daktarin range, Daktacort Hydrocortisone): Products containing miconazole only are suitable for patients of all ages and should be used twice a day. Treatment should continue for 10 days after all lesions have disappeared to prevent relapse. Daktacort hydrocortisone is suitable for children aged over 10 and is licensed for sweat rash and athlete’s foot.

Tolnaftate (e.g. Mycil, Tinaderm, Scholl Athlete’s Foot Powder, liquid & cream)

Products containing tolnaftate have no interactions or side effects and can be used by all patients. They can be used for athlete’s foot and infections of the groin and should be used twice a day with treatment continuing for at least 1 week after the infection has cleared up.

Undecenoates (e.g. Mycota)

Products containing undecenoates have no interactions and can be used by all patients. They are licensed for athlete’s foot and should be used twice a day and treatment continued for at least 1 week after the infection has cleared up. Local irritation has been reported.

Benzoic acid (e.g. Whitfield’s ointment)

Benzoic acid (in combination with salicylic acid) is now rarely used. However, it is a safe medicine and can be used by all patients.

Terbinafine (Lamisil range & Scholl Advance Athlete’s Foot Cream)

Terbinafine can be used to treat athlete’s foot, groin infection and tinea corporis. The cream should be applied once or twice a day whereas the spray and gel should be used only once daily. It has no interactions, has few reported side effects and can be used by all patients. All products are licensed for people aged over 16, except Lamisil Once, which is for use in people aged over 18 years of age.

Griseofulvin (Grisol AF spray)

Licensed for athlete’s foot, Grisol should be applied to the area once daily. Each spray delivers 400 µg of griseofulvin with a maximum of three sprays in 24 hours for more extensive or severe infection. The spray should be used for 10 days after the lesions clear to prevent reinfection. It has no interactions, has few reported side effects and can be used by all patients.

References

Aly, R, Bayles, CI, Oakes, RA, et al. Topical griseofulvin in the treatment of dermatophytoses. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:43–46.

Crawford, F, Hollis, S. Topical treatments for fungal infections of the skin and nails of the foot. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007. [Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001434. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001434.pub2].

Drake, LA, Dinehart, SM, Farmer, ER, et al. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea faciei, tinea manuum, and tinea pedis. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:282–286.

Elewski, B. Tinea capitis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:23–31.

Moriarty, B, Hay, R, Morris-Jones, R. The diagnosis and management of tinea. BMJ. 2012;345:e4380.

Fungal nail infection (onychomycosis)

Background

The deregulation of amorolfine in the UK and other Western countries (e.g. Australia) now makes it possible for community pharmacists to treat infection affecting the toenails. Onychomycosis is defined as a chronic fungal infection of the fingernails or toenails, although only infection of the toenail is covered in the text. The infection is common but is probably under reported because of patient embarrassment or ignorance that they have an infection. If left untreated it can lead to pain and discomfort, which can make wearing shoes difficult. Nails, over time, will disfigure and crumble away.

Prevalence and epidemiology

It is estimated that over 10% of the general population suffer from onychomycosis (Thomas et al 2010). The incidence of infection increases with increasing age and is particularly common in people aged over 70 years of age (e.g. estimated at up to 50%).

Aetiology

Over 90% of cases are caused by dermatophytes (Trichophyton rubrum and T. interdigitale), with the remainder caused by yeasts and moulds. In most cases predisposing factors can be determined in the development of nail infection: for example, an initial skin infection (tinea pedis), in immunocompromised patients, or poor peripheral circulation and neuropathies (e.g. diabetes).

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

There are a number of different types of onychomycosis and it is important to be able to differentiate between them because amorolfine is only licensed for the treatment of distal lateral subungual onychomycosis. Taking a history of the presenting symptom will be helpful but a visual inspection of the toenails is strongly advocated.

Clinical features of distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO)

DLSO is usually asymptomatic and people often seek medical help because of concerns about the appearance of the nail. The nail takes on a dull opaque and yellow appearance. Over time the nail thickens and distorts and as infection spreads and worsens the nail becomes brittle and crumbles away or falls off (Fig. 7.15). The key clinical symptoms that differentiate DLSO from other types of onychomycosis are summarised in Table 7.13. (For more images of fungal nail infection visit http://www.dermnetnz.org/fungal/onychomycosis.html; accessed 13 November 2012.)

Table 7.13

| Type | Key characteristics | Spread of infection |

| DLSO | Mainly big toe | Note yellowing starts at distal part of toe or side of nail |

| Proximal subungual onychomycosis (PCO) | Immunocompromised patients | Yellow spots appear at the base of the nail (i.e. in the half-moon area of the nail) |

| Superficial white onychomycosis | Often occurs in previously damaged nails Chalky-white in appearance and can be scraped off the nail surface |

Located on the surface of the nail |

Other conditions to eliminate

Psoriasis, eczema and trauma can affect the nail and need to be considered; in psoriasis, nail pitting is visible; for trauma there should be an identifiable event which affected the nail; and in eczema and psoriasis the skin should be affected, either near and around the feet (eczema) or remotely (psoriasis plaques on areas such as knees and elbows).

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Amorolfine is a broad-spectrum antifungal agent that works by inhibiting ergosterol synthesis. An open-labelled, non-randomised trial has shown it to be effective, producing clinical cure in 37% of toenail infections (Zaug 1992). However, the study suffered from large drop-out rates (nearly 30%), and there was no comparisons with other available topical antifungal treatments. A further trial, comparing once versus twice weekly application of amorolfine reported similar cure rates (46%) with weekly application (Reinel 1992). A Cochrane review found limited evidence for the efficacy of any topical treatments for nail infections, but suggested that cure rates may be better with amorolfine, although based on small trials (Crawford & Hollis 2007). Prodigy guidance (July 2012) advocate the use of amorolfine when the infection is mild and superficial.

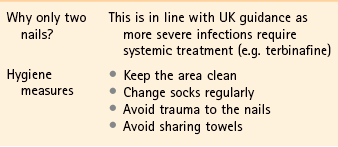

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to amorolfine is summarised in Table 7.14; useful tips relating to patients presenting with fungal nail infection are given in Hints and Tips Box 7.4.

Amorolfine (Curanail)

Amorolfine is available as a 5% nail lacquer. It is used weekly and treatment lasts until the affected nail(s) have regrown and are clear of infection. This takes approximately 6 months for fingernails and 9 to 12 months for toenails. Each pack of Curanail gives 3 months treatment which affords the pharmacist an opportunity to review treatment before further medication is given. The product licence restricts use to no more than two nails in people aged 18 or over and have no underlying medical conditions that predispose them to fungal infection (e.g. immunocompromised and diabetics). The manufacturer states it should not be used in pregnant or breastfeeding women. To apply amorolfine the nail must be first filed and cleaned. Files and cleaning pads are provided in the treatment pack and are not reusable. The lacquer should then be evenly applied and left to dry. Amorolfine is unlikely to cause side effects, but skin irritation has been reported.

References

Crawford, F, Hollis, S. Topical treatments for fungal infections of the skin and nails of the foot. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007. [Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001434. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001434.pub2].

Reinel, D. Topical treatment of onychomycosis with amorolfine 5 per cent nail lacquer: comparative efficacy and tolerability of once and twice weekly use. Dermatology. 1992;184(Suppl):21–24.

Thomas, J, Jacobson, GA, Narkowicz, CK, et al. Toenail onychomycosis: an important global disease burden. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2010;35(5):497–519.

Zaug, M, Bergstraesser, M. Amorolfine in the treatment of onychomycosis an dermatomycoses (an overview). Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;179(Suppl. 1):61–70.

Hair loss (androgenetic alopecia)

Background

Each hair consists of a shaft, made up of dead keratinised cells, and a root (Fig. 7.1) and is found on most skin surfaces (hands, feet and lips being notable exceptions). Each hair follicle goes through a growth cycle, which consists of a long growing phase (anagen) followed by a short resting phase (telogen). At the end of resting phase, the hair falls out (catagen) and a new hair starts growing in the follicle, beginning the cycle again. The hair cycle occurs randomly for each follicle so that normal hair loss from the adult scalp is approximately 100 hairs per day; where the rate is greater than this then the clinical signs of hair loss can be observed. Hair loss affects both men and women and is associated with strong emotional and psychological consequences. People have been socialised to link a full head of hair with youth and vitality, whereas baldness portrays a feeling of unattractiveness and loss of youth. Hair loss can be due to a number of aetiologies; however, this section concentrates on androgenetic alopecia (male pattern baldness) because it is the most common cause of hair loss.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Men are more susceptible than women to androgenetic alopecia and usually experience more severe hair loss. Men tend to be affected from the second decade onwards (30% of men by 30 years old will be affected to some degree) and the prevalence of male pattern baldness in Caucasians who reach old age approaches 100%. In women the condition becomes more pronounced after menopause.

Patients usually have a positive family history. The nature and extent of hair loss will follow identical patterns to those seen in the patient’s immediate parents and grandparents, which can be used as a predictor to the patient’s potential hair-loss pattern.

Aetiology

Hair is classed as either terminal or vellus hair. Terminal hair is longer and thicker and found on the scalp and eyebrows. Vellus hair covers the remainder of the body and is shorter and downy. In androgenetic alopecia terminal hair follicles transform in to more vellus-like hair follicles as a result of preferential binding by dihydrotestosterone (produced from the conversion of androgen by 5-alpha-reductase) to hair follicle receptors. Eventually the follicle ceases activity completely with resulting hair loss.

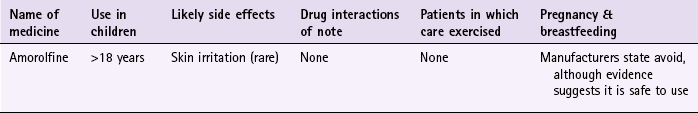

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Hair loss is obviously easy to detect. Empathy and understanding toward the patient needs to be exercised. Although androgenetic alopecia is the most common form of hair loss, other causes need to be eliminated (Fig. 7.16). Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 7.15).

![]() Table 7.15

Table 7.15

Specific questions to ask the patient: Hair loss

| Question | Relevance |

| Hair loss accompanied with other symptoms | Androgenic alopecia is not associated with other symptoms. Itch and/or erythema are indicators that another cause, e.g. fungal scalp infection, psoriasis or seborrhoeic dermatitis, might be responsible for the hair loss |

| Pattern of hair loss | In men, hair loss begins at the front of the head and recedes backwards or at the crown. In women, hair loss tends to be generalised and diffuse. Presentations that differ to this or are sudden in onset suggest another cause of hair loss |

| Deficiency states | There is now strong evidence that iron deficiency in women can cause hair loss |

| Underlying pathology | A number of endocrine conditions can cause hair loss, most notably thyroid disorders |

| Medicine induced hair loss | A number of medicines can cause hair loss (Table 7.16) |

| Hair loss triggered by a specific event | Hair loss can be caused by a stressful event or following surgery or after childbirth |

Clinical features of androgenetic alopecia

Men initially notice a thinning of the hair and a frontal receding hairline that might or might not be accompanied with hair loss at the crown. In women the frontal hairline is maintained with diffuse hair loss that is somewhat accentuated at the crown.

Conditions to eliminate

Telogen effluvium represents a shift of more hairs in to the resting phase (telogen) of the hair cycle, which results in shedding of hair. This can be caused by a number of factors:

Postpartum

During pregnancy, circulating levels of oestrogen increase, with a resulting rise in the number of follicles in anagen (growth phase); the hair therefore thickens. However, after delivery the hair follicles return to the resting phase and the hair is shed. Women might believe that they are experiencing hair loss when in reality the hair is returning to the normal pre-pregnancy state. Reassurance should be given that this is a temporary and self-limiting problem.

Stress

Stress is known to induce hair loss. The reason behind this is poorly understood. Enquiry to ascertain lifestyle factors that might have caused recent stress and anxiety to the patient should be explored.

Nutritional factors

Iron deficiency is associated with female hair loss. If iron deficiency is the cause, a 2-month course of iron supplementation should result in thickening of the hair. If the patient fails to respond to treatment then the patient should be reassessed.

Underlying endocrine disorder

Diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism can result in poor hair growth. In hypothyroidism the hair is thin and brittle and the patient might be lethargic and have a history of recent weight gain. Referral to the GP for blood tests should be considered.

Fungal scalp infection (tinea capitis)

The first signs of infection are the appearance of a well-circumscribed round patch of alopecia that is associated with itch and scaling. Common areas of involvement include the occipital, parietal and crown region. Inspection of the area might reveal erythema and ‘black dots’ on the scalp as a result of infected hairs.

Alopecia areata

Refers to hair loss of unknown origin, although there is often an association with atopy and autoimmune disease and a positive family history is found in up to 25% of patients. It is relatively uncommon affecting 0.1 to 0.2% of the UK population. Unlike androgenetic alopecia the hair loss is sudden and mainly affects children and adolescents (60% will have had their first episode before the age of 20). It most commonly involves only small patches of hair loss although the whole scalp can be affected. The condition is usually self-limiting and regrowth of hair is often observed but repeated episodes are not unusual.

Traction alopecia

Most commonly seen in women, traction alopecia refers to hair loss due to excess and sustained tension on the hair, usually as a result of styling hair with rollers or a particular type of hairstyle. It is reversible if the tension on the hair is removed.

Medicine-induced causes

Many medicines can interfere with the hair cycle and cause transient hair loss, cytotoxic medicines being one of the most obvious examples. However, many medicines have been associated with hair loss. Table 7.16 lists some of the more commonly implicated medicines. If medicines other than cytotoxics are suspected of causing hair loss, the prescriber should be contacted to discuss other possible treatment options.

![]() Table 7.16

Table 7.16

Medicines known to cause hair loss

| Medicine or medicine class | Incidence of hair loss |

| Antineoplastics | Almost 100% (to varying degrees) |

| Anticoagulants | Telogen effluvium in approximately 50% |

| Lithium carbonate | Telogen effluvium in approximately 10% |

| Interferons | Telogen effluvium in 20 to 30% |

| Oral contraceptives | Seen 2 to 3 months after stopping |

| Retinoids | Approximately 20% of patients |

| Colchicine, carbimazole | Rare |

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Currently, minoxidil is the only product marketed for androgenetic alopecia. It is available as either a 2 or 5% solution.

A number of clinical trials have investigated the efficacy and safety of minoxidil at 2 and 5% concentrations. The majority of these have been conducted on precisely the population that would respond the best to treatment; men aged between 18 to 50, with mild to moderate thinning of the hair at the vertex. Despite this, trial results are not totally convincing. Minoxidil is superior to placebo (although placebo does invoke a large initial response) and promotes a small increase in re-growth of vellus hair and increases the diameter of the hair shaft. However, longitudinal studies show that less than half of patients treated experience moderate to marked hair growth. Hair counts appear to be greatest after 12 months of treatment but, by 30 months, hair counts have decreased (albeit still above baseline) and the bald area increases back in size to its initial diameter.

Minoxidil therefore appears to delay and slow down hair loss in less than half of its target patient population. Furthermore, if treatment is stopped any hair growth achieved is lost within 6 to 8 weeks on discontinuation of therapy and baldness returns to pretreatment levels.

The situation in women is not too dissimilar, although the 5% solution offers no advantage over the 2% solution and has therefore not been granted a product licence at that strength.

Summary

Minoxidil will not significantly help the majority of balding individuals. It will promote hair growth in approximately 50% of minimally balding young men but, over time, the effect tails off. After 30 months the effect is still greater than baseline but, on the whole, will not achieve cosmetically acceptable hair growth. In other words the use of minoxidil is useful for specific patients who want to ‘buy’ themselves time from the inevitable balding process.

Oral finasteride (1 mg per day) can be used to treat androgenic alopecia in men but currently there is no good quality evidence that it is superior to minoxidil.

Practical prescribing and product selection

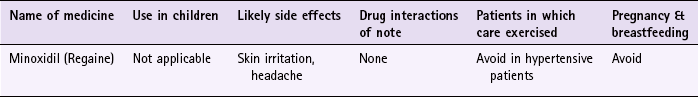

Prescribing information relating to minoxidil is discussed and summarised in Table 7.17; useful tips relating to the treatment of patients with minoxidil are given in Hints and Tips Box 7.5.

Minoxidil (e.g. Regaine range as either solution or foam)

The dose for minoxidil is 1 mL of solution (or 1 g of foam – equivalent to half a capful) applied to dry hair to the total affected areas of the scalp twice daily. If fingertips are used to facilitate drug application, hands should be washed afterwards. Although minoxidil is applied topically, absorption into the systemic circulation can occur and result in chest pain, rapid heartbeat, faintness or dizziness, although these are rare. If these occur the patient should stop using the product immediately. Other less important adverse effects associated with topical minoxidil are local irritation, redness and itching but these appear to be related to the vehicle – propylene glycol – rather than minoxidil. Changes in blood pressure should not occur because the serum level of minoxidil after topical application is below that needed to cause changes to blood pressure, however as a precaution minoxidil should be avoided in hypertensive patients if possible. Some patients also report a temporary increase in hair shedding 2 to 6 weeks after beginning treatment. This subsides and is most likely due to the action of minoxidil, shifting hairs from the resting telogen phase to the growing anagen phase.

Burke, KE. Hair loss. What causes it and what can be done about it. Postgrad Med. 1989;85:52–58. 67–73, 77

Gilhar, A, Etzioni, A, Paus, R. Alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1515–1525.

Katz, HI, Hien, NT, Prawer, SE, et al. Long-term efficacy of topical minoxidil in male pattern baldness. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:711–718.

Koperaki, JA, Orenberg, EK, Wilkinson, DL. Topical minoxidil therapy for androgenetic alopecia: a 30 month study. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1483–1487.

Price, VH, Menefee, E, Strauss, PC. Changes in hair weight and hair count in men with androgenetic alopecia, after application of 5% and 2% topical minoxidil, placebo, or no treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:717–721.

Rietschel, RL, Duncan, SH. Safety and efficacy of topical minoxidil in the management of androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:677–685.

Roberts, JL. Androgenetic alopecia in men and women: an overview of cause and treatment. Dermatol Nurs. 1997;9:379–388.

Tosti, A, Misciali, C, Piraccini, BM, et al. Drug-induced hair loss and hair growth: incidence, management and avoidance. Drug Saf. 1994;10:310–317.

2012. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of alopecia areata. http://www.bad.org.uk/Portals/_Bad/Guidelines/Clinical%20Guidelines/Alopecia%20areata%20guidelines%202012.pdf, 2012.

Warts and verrucas

Background

Warts and verrucas are benign growths of the skin caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV). Certain types of HPV have an affinity for certain body locations, for example hands, face, anogenital region and feet. Spontaneous resolution is seen in 30% of people within 6 months and two-thirds of cases within 2 years. Despite their self-limiting nature they are cosmetically unacceptable to many patients and with nearly 60% of people trying an OTC treatment before visiting a GP the pharmacist has a major role to play in their management.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The prevalence of warts has not been accurately documented and published prevalence data varies widely. However, it is clear children are most affected, having been reported to affect between 2 and 20% of schoolchildren, with a peak incidence between 12 and 16 years old. Warts are uncommon in infants and the elderly and caution should be exercised if an elderly patient presents to the pharmacy with a self-diagnosed wart.

Aetiology

HPV gain entry to the host by epithelial defects in the epidermis. It is transmitted by direct skin-to-skin contact, although contact with an infected person’s shed skin can also transmit the virus. Infection via the environment is more likely to occur if the skin is macerated and in contact with roughened surfaces, for example in swimming pools and communal washing areas. Once established in the epithelial cells, the virus stimulates basal cell division to produce the characteristic lesion.

Patients, especially children, should be warned not to pick, bite or scratch warts as this can allow viral particle shedding to penetrate skin breaks. This process is known as autoinoculation and is responsible for multiple lesions becoming established and transferred to other parts of the body.

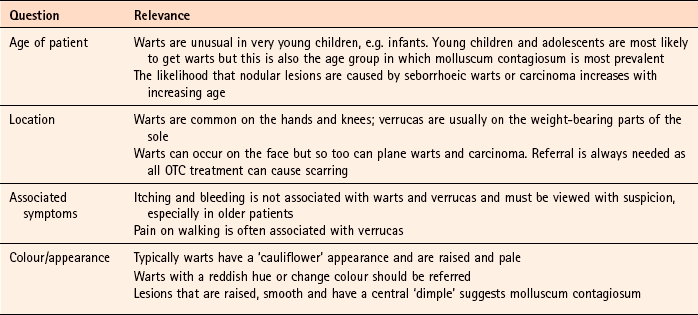

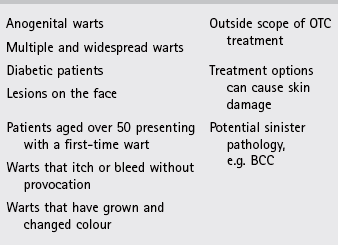

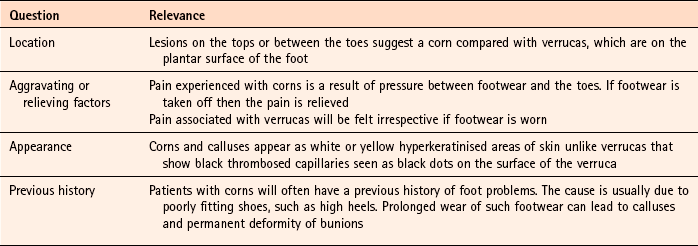

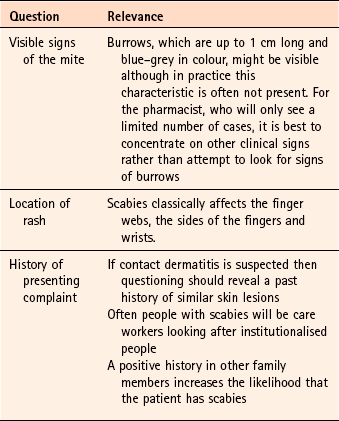

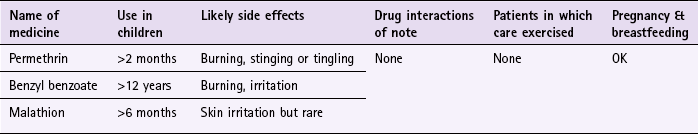

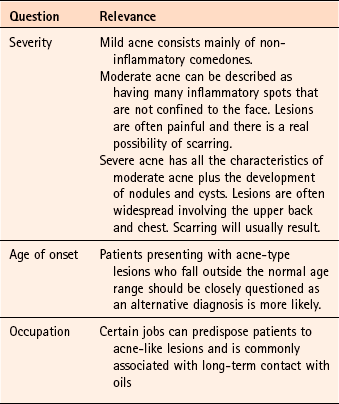

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Warts and verrucas are not difficult to diagnose. However, pharmacists must be able to recognise other similar conditions that superficially look like warts and verrucas. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 7.18). HPV infections involving the anogenital area are outside the remit of community pharmacists and must be referred.

Clinical features of warts and verrucas

Warts most often occur on the backs of the hands, fingers and knees, either singly or in crops. When examined the wart appears as a raised, hyperkeratotic papule with thrombosed, black vessels often visible as black dots within the wart. They tend to be rough textured, skin-coloured and are usually less than 1 cm in diameter (Fig. 7.17).

Verrucas

Verrucas are found on the sole of the foot, usually in weight-bearing areas, for example on the metatarsal heads or heel. Owing to constant pressure imparted on the sole of the foot the normal outward expansion of the wart is thwarted and instead grows inward. Pressure on nerves can then cause considerable pain and patients often complain of pain when walking. Inspection of the lesion will normally reveal tiny black dots (thrombosed capillaries) on the surface (Fig. 7.18). Owing to keratin build-up this characteristic sign might not be visible unless the hardened skin is first shaved away. Verrucas, like warts, are rarely larger than 1 cm in diameter and can occur singly or in crops. A number of closely located plantar warts can coalesce to form a large single plaque and is termed a mosaic wart.

Conditions to eliminate

Plane warts (flat warts or verruca plana)

These most frequently occur in groups on the face and the back of the hands. They are small in size (1 to 5 mm in diameter), slightly raised and can take on the skin colour of the patient (Fig. 7.19). As drug treatment is destructive in nature, plane warts located on the face should be referred to avoid the risk of scarring.

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum primarily affects children under 5 years old. It is not particularly common and a GP with a list size of 2000 will probably see 5 new cases per year. It is caused by a pox virus and patients present with multiple lesions usually on the face and neck, although the trunk can be involved. The lesions resemble common warts but each raised papule tends to be smooth and have a central dimple, the latter is a useful diagnostic point (see Fig. 9.6, page 301). Lesions tend to be between 1 to 5 mm in diameter. The condition is self-limiting and will resolve without medical intervention. Patients should be told this, but if they believe treatment is necessary, referral to the GP is advisable.

Corns

Corns and plantar warts can be confused. The reader is referred to page 228 on corns and calluses for information on differentiating corns from verrucas.

Basal cell papilloma (seborrhoeic wart)

Basal cell papillomas are benign growths that are increasingly common with increasing age. They usually occur on the trunk and present as raised often multiple lesions that have a superficial ‘stuck on’ or waxy appearance (Fig. 7.20). Lesions are usually brown but can range in colour from pink to black.

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma is the commonest form of skin cancer and its incidence is related to sunlight exposure. It typically occurs in older people especially where there is a history of prolonged skin exposure. Men are twice as likely to be affected. The usual site where lesions develop is the face. Any wart-like lesion that is itchy, has an irregular outline, prone to bleeding and exhibits colour change should be referred to eliminate serious pathology. For more information on skin cancers see page 245.

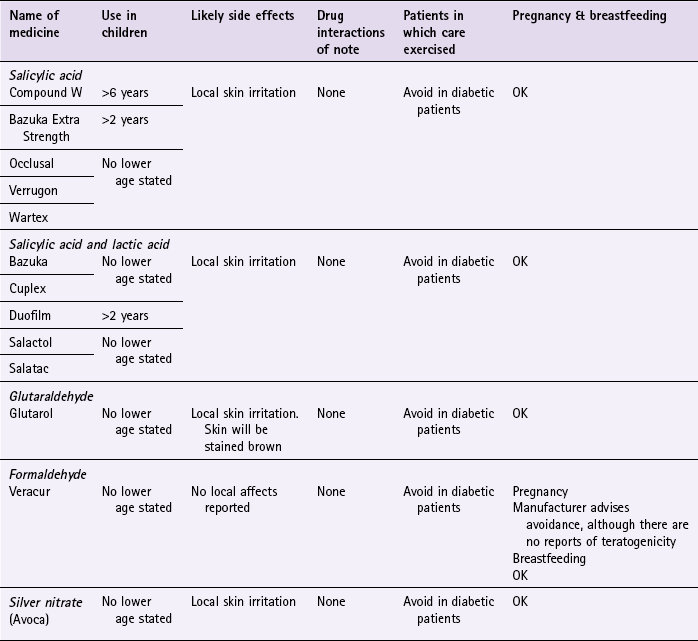

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

A number of ingredients are used to treat warts and verrucas, although salicylic acid is the most commonly used agent and can be found in many OTC treatments, both alone and combined with lactic acid.

A recent Cochrane review (Gibbs & Harvey 2006) investigated topical treatments for the cure of warts. This review identified 60 trials that met their inclusion criteria. Overall, the quality of the trials was low due to poor methodology and reporting. However, placebo was found to have a substantial effect although salicylic acid in comparison was significantly more effective. Cure rates for salicylic acid (from pooled data) showed 73% cure rates compared to control cure rates of 48% over a 6 to 12 week period. However, there appears to be no evidence to suggest which concentration of salicylic acid is most effective.

In addition, there is some evidence to show that common warts are more responsive to keratolytic therapy than plantar warts and resolution might be enhanced by soaking the wart or verruca prior to application and/or occlusion of the site (by use of plasters or collodion-like vehicle) to aid penetration.

Compliance with treatment has been identified as a limiting factor in the cure rate for warts and verrucas. One study that investigated Occlusal reported an 80% cure rate after only 2 weeks of therapy. This might be an alternative option for patients whose compliance could be questioned. However, the study suffered from poor design and had only a small number of patients and the results must be viewed with caution.

Salicylic acid is often combined with other ingredients, in particular lactic acid. However, there is no evidence to support additionally efficacy when lactic acid is added. Monochloroacetic acid has also been combined with salicylic acid. Cure rates for this combination are comparable to cure rates of salicylic acid alone or when monochloroacetic acid is used singly. It therefore appears that the combination has no additional benefit than when active ingredients are used as monotherapy. As far as the author is aware, no commercially available preparation contains monochloroacetic acid.

Other agents commercially available include, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde and silver nitrate pencils. Information regarding their effectiveness stems from small-scale or poorly designed studies, and they should not be routinely recommended.

Cryotherapy using liquid nitrogen has been used for many years as a treatment of recalcitrant or widespread warts. However, the limited comparisons between topical salicylic acid and cryotherapy have failed to show any difference in response rates (Gibbs et al 2002). OTC products containing volatile hydrocarbons are marketed as home cryotherapy solutions for the treatment of warts (e.g. Wartner). There is a lack of data comparing salicylic acid preparations with home cryotherapy. However, comparisons between home cryotherapy solutions and cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen have suggested liquid nitrogen is superior (Gibbs et al 2002).