Specific product requests

Background

Many patients will present in the pharmacy requesting a specific product rather than wanting advice on symptoms. They might have seen the product advertised on the television or been told to purchase it from their doctor. Regardless of the reason why they are asking for the product, it is the responsibility of the pharmacist to ensure that the patient receives the most appropriate therapy. This chapter therefore deals with situations where patients ask for a particular product or class of product but the pharmacist needs to elicit more information from the patient before complying with the request.

Motion sickness

Motion sickness is a symptom complex that is characterised by nausea, pallor, vague abdominal discomfort and occasionally, vomiting. Symptoms of fatigue, weakness, inability to concentrate can also be observed prior to nausea. Over prolonged exposure to motion, symptoms tend to resolve. For example, sea sickness at the beginning of a voyage disappears over time – a characteristic called adaptation or habituation. Pharmacists are frequently asked to recommend a product, especially by anxious parents. Motion sickness can affect any individual and involve any form of movement, from moving vehicles to fairground rides.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The exact prevalence of motion sickness is unknown. Children between the ages of 2 and 12 are most commonly affected and it tends to affect women more than men. However, certain sectors of the population understandably show a higher prevalence rate than the normal population, for example naval crew and pilots.

Aetiology

It is widely believed that motion sickness results from the inability of the brain to process conflicting information received from sensory nerve terminals concerning movement and position, the sensory conflict hypothesis. Motion sickness can occur when motion is expected but not experienced, or the pattern of motion differs from that previously experienced.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

First generation antihistamines (cyclizine, cinnarizine, meclozine and promethazine) and anticholinergics (hyoscine and scopolamine) are routinely recommended to prevent motion sickness. All have shown various degrees of effectiveness. A Cochrane review of scopolamine identified 14 studies (n = 1025) and found scopolamine to be superior to placebo and some other treatments (metoclopramide), and as good as antihistamines (Spinks et al 2011).

Ginger has long been advocated for use as an anti-emetic. A review by Chrubasik and colleagues (2005) identified four exploratory studies of ginger in the prevention of motion sickness. The results of these studies suggested ginger was better than placebo, and similar in efficacy to other pharmacological agents. However, the studies were often in small numbers of patients, and of uncertain quality; the authors of the review concluded that further studies are required to confirm the effectiveness of ginger for motion sickness.

Non-pharmacological approaches to the prevention of motion sickness using acupressure are also available OTC. Bruce et al (1990) investigated the use of Sea Band acupressure bands versus hyoscine and placebo. Eighteen healthy volunteers were subjected to simulated conditions to induce motion sickness. The findings showed that whilst hyoscine exerted a preventative effect, Sea Bands were no more effective than placebo. Further trials have confirmed these findings, although 1 small trial by Stern et al (2001) reported positive findings. However, accurate placement of the Sea Band seems to be important, and further trials are needed as acupressure has shown positive effects for nausea and vomiting associated with pregnancy.

Practical prescribing and product selection

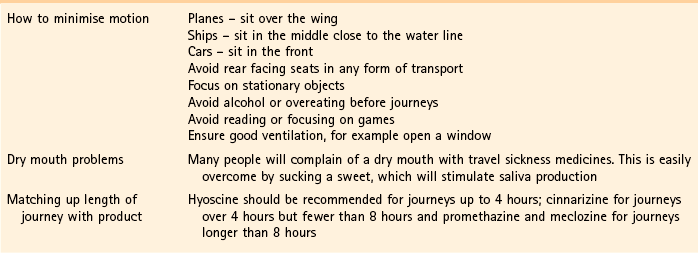

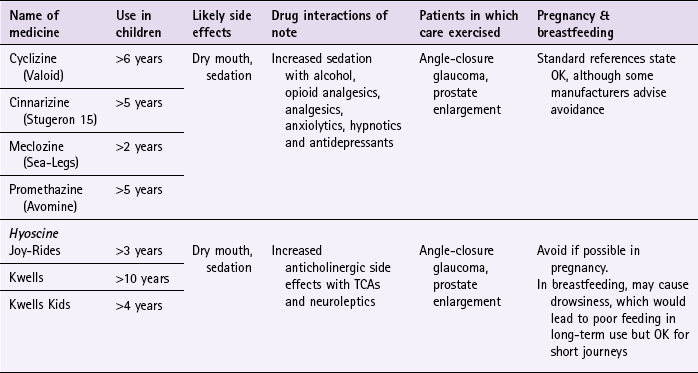

Prescribing information relating to medicines for motion sickness reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 10.1. They are most effective when given prior to exposure and products should be selected based on matching the length of the journey with the duration of action of each medicine (see Hints and Tips Box 10.1).

Antihistamines

Antihistamines used in products for motion sickness are first generation H1 antagonists and are associated with sedation. They therefore have the same side effects, interactions and precautions in use as other first generation antihistamines used in cough and cold remedies. For further information see page 8.

Cyclizine (Valoid)

Cyclizine is prescribed very rarely. It is subject to abuse by drug misusers and many pharmacies do not stock it. If taken, adults and children over 12 should take one tablet (50 mg) three times a day. The dose for children over the age of 6 is half the adult dose.

Cinnarizine (Stugeron 15)

Adults and children over 12 should take two tablets 2 hours before travel. The dose can be repeated every 8 hours (1 tablet) if needed. For children aged between 5 and 12 the dose is half the adult dose.

Meclozine (Sea-Legs)

Adults and children over 12 years should take two tablets (25 mg) 1 hour prior to travel, however as activity lasts 24 hours the dose can be taken the night before travel. Children aged between 6 and 12 years should take half the adult dose (one tablet, 12.5 mg) and for children over 2, half a tablet (6.25 mg) should be taken. The dose can be repeated every 24 hours if needed.

Promethazine (Avomine)

Avomine can be given for both prevention and treatment of travel sickness. For prevention, adults and children over the age of 10 should take one tablet at least 1 or 2 hours before travel. For treatment, 1 tablet should be taken as soon as sickness is felt followed by a second tablet 6 to 8 hours later. For children over 5 the dose should be half that of the adult dose in both prevention and treatment. Promethazine is also available as Phenergan, and can be given to children from the age of 2 years.

Hyoscine

Hyoscine can be taken either orally (e.g. Joy Rides and Kwells) or transdermally (e.g. Scopolamine patches – although these were discontinued in September 2006). Products should be taken 20 to 30 minutes before the time of travel; because they have a short half life they have a short duration of action and the dose might therefore have to be repeated on journeys longer than 4 hours. Anticholinergic side effects are more obvious than with antihistamines and it does interact with other medicines that have anticholinergic side effects and should therefore not be co-prescribed. Because hyoscine hydrobromide crosses the blood–brain barrier it can cause sedation. It appears to be safe in pregnancy, although the manufacturers state it should be avoided.

Joy-Rides: Joy rides can be given from age 3 upwards. Children aged between 3 and 4 years should take half a tablet (75 µg) and no more than 1 tablet (150 µg) in 24 hours. Children between the age of 4 and 7 should take one tablet (150 µg) with a maximum of 2 tablets (300 µg) in 24 hours and children aged between 7 and 12 should take one to two tablets.

Kwells: Kwells can only be given to children aged 10 and over. Children over 10 should take  to 1 tablet. For adults the dose is one tablet. The dose can be repeated every 6 hours when needed. Tablets should be taken 30 min before travel.

to 1 tablet. For adults the dose is one tablet. The dose can be repeated every 6 hours when needed. Tablets should be taken 30 min before travel.

Kwells Kids: Kwells Kids contain half the amount of hyoscine (150 µg) than Kwells and are marketed at children under the age of 10, although older children can take them. Children aged between 4 and 10 should take half to one tablet. Like Kwells, the dose can be repeated every 6 hours when needed and be taken 30 minutes before travel.

References

Bruce, DG, Golding, JF, Hockenhull, N, et al. Acupressure and motion sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1990;61:361–365.

Chrubasik, S, Pittler, M, Roufogalis, B. Zingiberis rhizoma: a comprehensive review on the ginger effect and efficacy profiles. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:684–701.

Spinks, A, Wasiak, J. Scopolamine (hyoscine) for preventing and treating motion sickness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011. [Issue 6. Art. No.: CD002851. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002851.pub4].

Stern, RM, Jokerst, MD, Muth, ER, et al. Acupressure relieves the symptoms of motion sickness and reduces abnormal gastric activity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2001;7:91–94.

Dahl, E, Offer-Ohlsen, D, Lillevold, PE, et al. Transdermal scopolamine, oral meclizine and placebo in motion sickness. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;36:116–120.

Klocker, N, Hanschke, W, Toussaint, S, et al. Scopolamine nasal spray in motion sickness: a randomised, controlled and crossover study for the comparison of two scopolamine nasal sprays with oral dimenhydrinate and placebo. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;13:227–232.

Pingree, BJ, Pethybridge, RJ. A comparison of the efficacy of cinnarizine with scopolamine in the treatment of seasickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1994;65:597–605.

Emergency hormonal contraception

Background

Emergency hormonal contraception (EHC) is one of only a handful of deregulated products, which targets preventative health care and fits with UK government public health policy. Like other Western countries, the UK has high teenage pregnancy rates and associated high abortion rates.

The intention of UK government policy on making EHC available through pharmacies was to improve access for patients requiring EHC at times when other providers might be closed, for example at weekends and evenings. This policy appears to have been effective. Since its launch in the UK in 2001 the percentage of EHC provided through community pharmacies has steadily increased (NHS Statistics 2011). Community pharmacists are now the main provider of EHC, and studies have consistently demonstrated that women obtain EHC more quickly from community pharmacies than from other providers. This is relevant as EHC is more effective the sooner it is taken after unprotected sex. The weekend and Mondays are particularly associated with increased demand for EHC services from community pharmacy.

Aetiology

The active ingredient in EHC is levonorgestrel. Its exact mechanism of action is not clear and appears to have more than one mode of action at more than one site. It is thought to work mainly by preventing ovulation and fertilisation if intercourse has taken place in the pre-ovulatory phase, when the likelihood of fertilisation is the highest. It is also suggested that it causes endometrial changes that discourage egg implantation.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

The effectiveness of levonorgestrel is hard to establish because many women will not become pregnant regardless if EHC is taken or not. However, trial data has found it to prevent 86% of expected pregnancies when treatment was initiated within 72 hours. Levonorgestrel is more effective the earlier it is taken after unprotected sex; it prevents 95% of pregnancies if taken within 24 hours of unprotected sex, 85% between 24 and 48 hours, and 58% if used within 48 to 72 hours.

Studies have shown that most women have heard of EHC (>90%), although their knowledge on when it can be taken and its effectiveness is lower; for example, less than half of women are aware of how long EHC remains effective and less than two-thirds are aware it was most effective the sooner it was taken after intercourse.

Some concerns have been raised about women abusing the EHC because of its greater accessibility. However, a review of international experience with pharmacy supply of EHC found only a small proportion of women use EHC repeatedly (6.8% using it twice in 6 months, and 4.1% using it three times) (Anderson & Blenkinsopp 2006). Further, the review found improved access of the EHC through pharmacies resulted in fewer visits to Accident and Emergency, and did not result in increased transmission of sexually transmitted diseases or risky sexual behaviours.

Practical prescribing and product selection

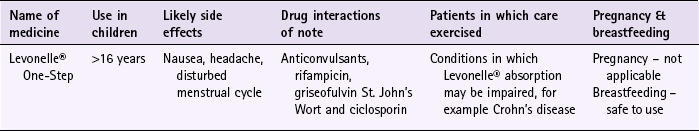

Prescribing information relating to EHC is discussed and summarised in Table 10.2.

Assessing patient suitability

Prior to any sale or supply of EHC the pharmacist has to be in a position to determine if the patient is suitable to take the medicine. To do this an assessment has to be made on the likelihood that the patient is pregnant:

• First, has the patient had unprotected sex, contraceptive failure or missed taking contraceptive pills in the last 72 hours? EHC can only be given to patients who present within 72 hours. If more than 72 hours have elapsed but less than 120 hours (5 days) then the patient can have an intrauterine device fitted or be prescribed ulipristal.

• Is the patient already pregnant? Details about the patient’s last period should be sought. Is the period late, and if so how many days late? Was the nature of the period different or unusual. If pregnancy is suspected a pregnancy test could be offered.

• What method of contraception is normally used? Patients who take combined oral contraceptives might not need EHC. Guidelines from the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (2011) state:

The patient should take the last pill they missed (even if this means taking two pills in one day) and continue taking the rest of the pack as usual. An additional method of contraception for the next seven days should be used. If the person has had unprotected sex in the previous seven days, and missed two or more pills (i.e. more than 48 hours late) in the first week of a pack, emergency contraception may be needed.

If pills are missed in the first week (Pills 1–7). EHC should be considered if unprotected sex occurred in the pill-free interval or in the first week of pill-taking.

If pills are missed in the second week (Pills 8–14). No indication for EHC if the pills in the preceding 7 days have been taken consistently and correctly (assuming the pills thereafter are taken correctly and additional contraceptive precautions are used).

If pills are missed in the third week (Pills 15–21). OMIT THE PILL-FREE INTERVAL by finishing the pills in the current pack (or discarding any placebo tablets) and starting a new pack the next day.

If the patient uses a progestogen-only form of contraception. After a missed or late pill a woman should be advised to abstain or use additional contraception such as condoms for the next 2 days (48 hours after the pill has been taken). Emergency contraception may be indicated if unprotected sex occurs during this 48-hour period.

A number of useful checklists have been produced and are used in practice. Many pharmacists ask patients to complete one of these forms, instead of asking potentially embarrassing questions in the pharmacy. Once the details of the form are completed, the pharmacist can decide whether EHC can be supplied to the patient.

Levonelle® One Step

Levonelle® should be taken as soon as possible after unprotected sex or contraceptive failure. The dose consists of a single tablet (levonorgestrel 1500 µg). About one in five patients experience nausea but only 1 in 20 go on to vomit. If the patient vomits within 3 hours of the first dose she should be advised that a further supply of EHC would be needed. Taking EHC can affect the timing of the next menstrual period and patients should be told that their period might be earlier or later than usual. However, if the period is different than normal or more than 5 days late then she should be advised to have a pregnancy test. A number of medicines do, theoretically, interact with Levonelle®, most notably those that are enzyme inducers and include anticonvulsants, rifampicin, griseofulvin and St. John’s Wort, although the clinical significance of the interactions appear low as only a handful of drug interaction reports have been received by the manufacturers. It seems prudent, until such time that more substantial evidence is available, that patients taking these medicines are best referred to the GP. In such circumstances, increasing the dose of Levonelle® is commonly practised (although not licensed). If this is not the preferred option then an alternative form of EHC can be given.

Advanced sale of EHC is also permitted. However, pharmacists must consider the clinical appropriateness of a supply, and should consider declining repeated requests for advance supply and advise patients to use more reliable methods of contraception. See Hints and Tips Box 10.2.

1998. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Lancet. 1998;352:428–433.

Piaggio, G, von Hertzen, H, Grimes, DA, et al. Timing of emergency contraception with levonorgestrel or the Yuzpe regimen. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Lancet. 1999;353:721.

British Pregnancy Advisory Service. http://www.bpas.org

Brook Advisory Centres. http://www.brook.org.uk/

Family Planning Association. http://www.fpa.org.uk

Marie Stopes International. http://www.mariestopes.org.uk

Bayer site. http://www.levonelle.co.uk/index.htm

Nicotine replacement therapy

Background

Smoking represents the single greatest cause of preventable illness and premature death worldwide. In 2010, over 80 000 people in the UK died as a result of smoking; putting this in context, smoking caused about 30% of all cancer deaths, 14% of all circulatory deaths and over 35% of all respiratory disease deaths.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The number of smokers over the age of 16 in the UK is falling – from a high of 45% in 1974 to 21% (21% of men and 20% of women) in 2010. Smoking is most common in those aged under 35; 32% in people aged between 20 and 24, and 27% in those aged 25 to 34. It is least common (12%) in people over 60. Prevalence of smoking amongst people in the routine and manual socio-economic group continues to be greater than amongst those in the managerial and professional group (29 and 14%, respectively).

Recent legislation changes to ban smoking in public places (the first country was the Republic of Ireland in 2004, and others now include England, Scotland, Finland, Italy, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, France and Malta) has been championed as having potential positive impact on smoking rates; for example, by decreasing exposure to passive smoking and increasing quit rates. To establish any effect will take time but statistical data from Ireland has shown a fall in cigarette sales and surveys in Italy show a decrease in tobacco consumption. A study in England that compared smoking prevalence a year after legislation was passed (2007) found no significant difference in the level of smoking (http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/003_Health_Lifestyles/Statistics%20on%20Smoking%202011/Statistics_on_Smoking_2011.pdf; accessed 22 November 2012).

Aetiology

Hundreds of compounds have been identified in tobacco smoke, however only three compounds are of real clinical importance:

• tar-based products, which have carcinogenic properties

• carbon monoxide, which reduces the oxygen-carrying capacity of the red blood cells

• nicotine, which produces dependence by activation of dopaminergic systems.

Tolerance to the effects of nicotine is rapid. Once plasma nicotine levels fall below a threshold, patients begin to suffer nicotine withdrawal symptoms and will crave another cigarette. Treatment is therefore based on maintaining plasma nicotine just above this threshold.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) has established itself as an effective treatment option. A 2008 Cochrane review (Stead et al 2008) found 111 trials (n > 40 000) comparing NRT to placebo or non-NRT treatments, and the results indicated that NRT increases rates of quitting smoking by 50-70%. It is not possible to say if one delivery system is better than another because comparative trials between delivery systems have not been conducted. Personal choice will therefore be the determining factor in which is chosen as being most suitable. In addition, the effectiveness of NRT is also affected by the level of additional support provided to the smoker and many smoking cessation services are offered through pharmacy as part of their contractual arrangements with local commissioners.

Numerous intervention strategies have been used involving NRT. These include nurse-led services, workplace interventions, GP services and pharmacy-based services. A Cochrane review (Sinclair et al 2004) of pharmacy intervention assessed two trials that met the authors’ inclusion criteria. Findings suggested that trained community pharmacists, providing a counselling and record keeping support programme may have a positive effect on smoking cessation rates. A 2012 review, which included the Cochrane review, reported that there was good evidence that community pharmacists can deliver effective smoking cessation campaigns, and that structured interventions and counselling were better than opportunistic intervention (Brown et al 2012).

It should be noted that relapse is a normal part of the quitting process, and occurs on average three to four times. If a smoker has made repeated attempts to stop and failed, or has experienced severe withdrawal, or has requested more intensive help, then referral to a specialist smoking cessation service should be considered.

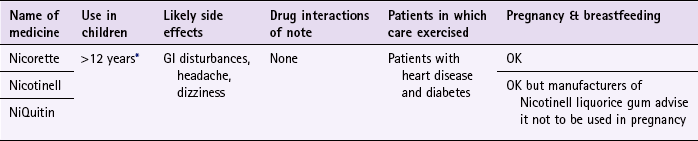

Practical prescribing and product selection

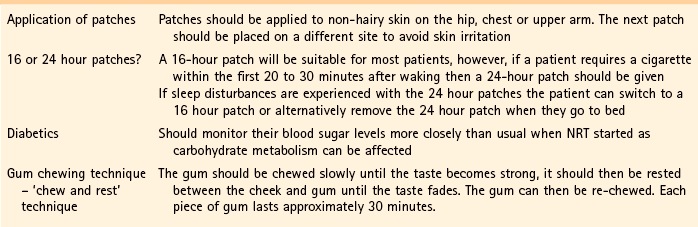

Prescribing information relating to medicines for NRT reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 10.3.

![]() Table 10.3

Table 10.3

Practical prescribing: Summary of medicines used as nicotine replacement therapy

*Note: some formulations are only licensed for people over 18 years of age, for example Nicotinell and NiQuitin lozenges.

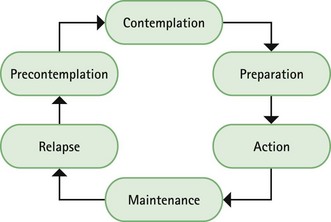

Prior to instigation of any treatment it is important that the patient does want to stop smoking. Work has shown that motivation is a major determinant for successful smoking cessation and interventions based on the transtheoretical model of change put forward by Prochaska and colleagues have proved effective (Fig. 10.1). The model identifies six stages, progress through which is cyclical, and patients need varying types of support and advice at each stage.

Most patients who ask directly for NRT will be at the preparation stage of the model and ready to enter the action stage. However, a small number of patients may well be buying NRT to please others and are actually in the precontemplation stage and do not want to stop smoking. Several studies have shown that approximately two-thirds of current smokers want to give up smoking, with three-quarters having tried to give up smoking at some point in the past.

NRT is formulated as gum, lozenges, patches, nasal spray, inhalator and sublingual tablets; therefore there should be a treatment option to suit all patients. When first deregulated, product licence restrictions did not allow OTC sale to certain patient groups such as those with heart disease, diabetes or pregnancy. However, in 2006, the Department of Health decided to lift the restrictions on NRT to these patient groups and people over the age of 12. The recommendation, according to the DoH, was based on strong evidence that it is ‘far more harmful’ for these groups to continue smoking than to use NRT. For those people under 18 years old treatment is generally limited to no more than 12 weeks, after which they should seek medical advice if treatment is still needed.

A number of approaches to NRT regimens are advocated. In general, the strength of the formulation is tailored to the number of cigarettes smoked and one form of NRT is tried at a time. However, it is possible for patients to use both patches and nicotine gum together, and there is evidence that this produces better results in patients with a high level of dependence. Additionally, patients can now use NRT to ‘cut down’ on the number of cigarettes smoked.

Side effects with NRT are rare and are either normally limited to gastrointestinal (GI) problems associated with accidental ingestion of nicotine when chewing gum, or local skin irritation and vivid dreams associated with patches. Headache, nausea and diarrhoea have also been reported. NRT appears to have no significant interactions with other medicines.

Nicorette

Nicorette is available as gum (2 and 4 mg), inhalation cartridge (10 and 15 mg), microtab (2 mg), nasal spray (10 mg) patches (5, 10 and 15 mg or ‘invisipatches’ 10, 15 and 25 mg) mouth spray (1 mg/spray) lozenge (2 mg) and combination packs (patch and gum).

Gum: Nicorette gum is available as either fruit or mint flavours (unflavoured gum leaves a bitter taste in the mouth). The strength of gum used will depend on how many cigarettes are smoked each day. In general, if the patient smokes less than 20 then the 2 mg gum should be used. If more than 20 cigarettes per day, then the 4 mg strength may be needed. A maximum of 15 pieces of gum can be chewed in any 24-hour period.

Inhalation cartridge: The inhalator can be particularly helpful to those smokers who still feel they need to continue the hand-to-mouth movement. Each cartridge is inserted into the inhalator and air is drawn into the mouth through the mouthpiece. Inhalators can be used to either reduce the number of cigarettes smoked or as part of a quit attempt. For the 10 mg inhalator a maximum of 12 cartridges per day can be used. Each cartridge can be used for approximately four sessions, with each cartridge lasting approximately 20 minutes of intense use. For the 15 mg inhalator a maximum of six cartridges can be used. Each cartridge can be used for approximately eight 5-minute sessions, with each cartridge lasting approximately 40 minutes of intense use.

The amount of nicotine from a puff is less than that from a cigarette. To compensate for this it is necessary to inhale more often than when smoking a cigarette.

Microtabs (2 mg): Microtabs are licensed for either smoking cessation or smoking reduction. For smoking cessation, the standard dose is one tablet per hour in patients who smoke less than 20 cigarettes a day (doubled for heavy smokers). This can be increased to two tablets per hour if the patient fails to stop smoking with the one tablet per hour regimen or for those whose nicotine withdrawal symptoms remain so strong they believe they will relapse. Most patients require between 8 and 24 tablets a day, although the maximum is 40 tablets in 24 hours. Treatment should be stopped when daily consumption is down to 1 or 2 tablets a day.

For those reducing the number of cigarettes smoked, the tablets should be used in between cigarettes to try and prolong the smoke-free period.

Nasal spray (each spray delivers 0.5 mg nicotine): At the start of treatment one spray should be put into each nostril, twice an hour to treat cravings. The maximum daily limit is 64 sprays; equivalent to two sprays in each nostril every hour for 16 hours. A 3-month treatment programme is advocated in smoking cessation attempts. For the first 8 weeks the patient uses the spray on a when needed basis. After which the patient should aim to reduce usage by half in the next 2 weeks and finally to nothing after a further 2 weeks.

Patches: Nicorette patches are marketed as either Nicorette ‘Invisi-patches’ (strengths of 25, 15 and 10 mg) or Nicorette patches (strengths of 15, 10 and 5 mg). The patches are usually applied in the morning and removed at bedtime (a 16 hour patch). Dosing for either product range is the same. Patients who want to stop smoking should start on the highest strength patch for 8 weeks before stepping down to the middle strength for a further 2 weeks. The lowest strength patch should be finally worn for another 2 weeks.

Mouth spray (each spray delivers 1 mg nicotine): The mouth spray can be used for either smoking cessation or smoking reduction. Smokers wanting to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked should use the mouth spray, as needed, between smoking episodes to prolong smoke-free intervals. For smoking cessation, one spray should be used when cravings emerge. If this first spray fails to control cravings a second spray can be used. Most smokers will require one to two sprays every 30 minutes to 1 hour. The maximum number of sprays in a 24 hour period is 64.

Lozenge (2 mg): Lozenges, like other dose forms, can be used for either smoking cessation or smoking reduction. Most smokers require 8 to 12 lozenges per day (maximum 15 lozenges per day). Reduction strategies are the same as other dose forms in that the lozenges are used when needed between smoking cigarettes to prolong smoke-free intervals and with the intention to reduce smoking as much as possible.

Nicotinell

Nicotinell is available as gum (2 or 4 mg), patches (7, 14 and 21 mg) and lozenge (1 and 2 mg). The Nicotinell range is promoted for smoking cessation rather than smoking reduction.

Nicotinell gum: Nicotinell gum is flavoured and available as fruit, mint or liquorice. The dosage and administration of Nicotinell gum is the same as that for Nicorette gum, except that a maximum of 25 pieces can be chewed in any 24 hour period.

Patches: The patches are worn continuously and changed every 24 hours, thus Nicotinell patches are suitable for those smokers who must have a cigarette as soon as they wake up, as nicotine levels will be above the threshold of nicotine withdrawal. Treatment is based on a stepwise reduction over a maximum period of 3 months. People who smoke more than 20 cigarettes a day should use the highest strength patch (TTS 30 patch, 21 mg) for 3 to 4 weeks, after which the strength of the patch should be reduced to the middle strength (TTS 20 patch, 14 mg) for a further 3 to 4 weeks before finally using the lowest patch (TTS 10 patch, 7 mg). If the patient smokes less than 20 cigarettes a day then they should start on the middle strength patch.

Lozenge: Low strength lozenges (1 mg) are recommended for those who smoke less than 20 cigarettes a day, whilst heavy smokers should use the higher strength (2 mg). Patients should be instructed to suck one lozenge every 1–2 hours when they have the urge to smoke. The usual dosage is 8 to 12 lozenges per day, with a maximum of 15 lozenges in 24 hours. Patients should be advised to gradually reduce the number of lozenges needed until they are only using one to two lozenges per day. At this point they should stop treatment.

Lozenges are mint flavoured and should be sucked until the taste becomes strong and then placed between gum and cheek (similar to the gum) until the taste fades, when sucking can recommence. Each lozenge takes approximately 30 minutes to dissolve completely.

NiQuitin

NiQuitin is available as gum (2 or 4 mg), patches (7, 14 and 21 mg) and lozenge (2 and 4 mg or NiQuitin minis, 1.5 and 4 mg).

Patches: Like Nicotinell, patches are designed to be worn continuously (24 hour patch) and dosing is based on a sequential reduction of nicotine over time. Patients who smoke more than 10 cigarettes a day should use the 21 mg patch (Step 1) for 6 weeks, followed by the 14 mg patch (Step 2) for 2 weeks and finally the 7 mg patch (Step 3) for the last 2 weeks. If the person smokes less than 10 cigarettes each day the patient should start on Step 2 for 6 weeks followed by Step 3 for a final 2 weeks.

NiQuitin lozenge: Lozenges can be used for smoking cessation or smoking reduction. The low strength lozenge (2 mg) is aimed at smokers who have their first cigarette of the day more than 30 minutes after waking up and the higher strength (4 mg) for those who smoke within 30 minutes of waking. Like patches the dose of lozenges are marketed as Steps. For smoking cessation the dosing schedule is:

| Step 1 × 6 weeks | 1 lozenge every 1 to 2 hours |

| Step 2 × 3 weeks | 1 lozenge every 2 to 4 hours |

| Step 3 × 3 weeks | 1 lozenge every 4 to 8 hours |

After this programme patients can use one to two lozenges a day over the next 12 weeks when strongly tempted to smoke.

For smoking reduction, as with other products, the lozenges should be used in between cigarettes to try and prolong the smoke-free period.

Niquitin Minis lozenge: Dosing of this version of the lozenge does vary from NiQuitin lozenges. The low strength (1.5 mg) is marketed for people who smoke less than 20 cigarettes a day and the high strength (4 mg) for those that smoke more than 20 cigarettes a day. For smoking cessation, it is recommended in either strength that the person should use between 8 and 12 lozenges per day (up to a maximum of 15 per day) and stop altogether when only using one or two lozenges per day.

For smoking reduction, as with NiQuitin lozenges, the lozenges should be used in between cigarettes to try and prolong the smoke-free period.

Gum: Gum can be used for smoking cessation or smoking reduction. Like lozenges, the lower strength (2 mg) is aimed at smokers who have their first cigarette of the day more than 30 minutes after waking up and the higher strength (4 mg) for those who smoke within 30 minutes of waking. The ‘chew and rest’ technique, as with Nicorette and Nicotinell, is used. For smoking cessation, it is recommended in either strength that the person should use between 8 and 12 pieces of gum per day (up to a maximum of 15 per day) and stop altogether when only using one or two pieces of gum per day.

For smoking reduction, as with NiQuitin lozenges, the gum should be used in between cigarettes to try and prolong the smoke-free period.

See Hints and Tips Box 10.3 for tips on nicotine replacement therapy.

Further reading

Chaplin, S, Hajek, P. Nicotine replacement therapy options for smoking cessation. The Prescriber. 2010;5th October:62–65.

Sinclair, HK, Bond, CM, Stead, LF. Community pharmacy personnel interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004. [Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003698. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003698.pub2].

Stead, LF, Perera, R, Bullen, C, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008. [Issue 1. Art. No.: CD000146. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub3].

2010. NHS Information centre: statistics on smoking. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/Health%20and%20Lifestyles/Statistics_on_Smoking_2010.pdf, 2010.

NICE PH10 Smoking cessation services. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11925/39596/39596.pdf

NICE Pathways. http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/smoking

Action on Smoking and Health (ASH). http://www.ash.org/

QUIT (UK charity). http://www.quit.org.uk/

Malaria prophylaxis

Background

Malaria is a parasitic disease spread by the female Anopheles mosquito. Four species of the protozoan Plasmodium produce malaria in humans; P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae and P. falciparum. P. falciparum is the most virulent form of malaria and is attributable for the majority of deaths associated with malaria infection.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Malaria is a leading cause of death in areas of the world where the infection is endemic, with an estimated 650 000 deaths in 2010 (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/). However, malaria is not only confined to endemic malarial areas and the number of cases reported in Western countries, for example the UK, is on the increase as more and more people travel to countries where malaria is common. There are between 1500 and 2000 cases reported in the UK each year. In 2010, there were 1761 cases that resulted in 7 deaths. Figures for that year show that P. falciparum accounted for 71% of cases (1261), P. vivax 20% (350), P. ovale 6% (99) and just 2% (37) for P. malariae.

For people travelling to countries where malaria is present, the risk of contracting malaria varies greatly. It depends on the area visited, the time of year, altitude (parasite maturation cannot take place above 2000 metres) and how many infectious bites are received. In general, risk tends to increase in more remote areas than in urban/tourist areas, after rainy or monsoon seasons and at low altitude. It is therefore possible to have a different risk of contracting malaria within the same country; for example, visiting the southern lowlands of Ethiopia after the rainy season would pose a very high risk whereas trekking in the Simien mountains in the north of the country during the dry season would pose minimal risk.

Aetiology

Malarial parasites are transmitted to humans when an infected female anopheles mosquito bites its host. Once in the human host, the parasites (which at this stage of their life-cycle are known as sporozoites) are transported via the bloodstream to the liver. In the liver they divide and multiply (they are now known as merozoites). After 5 to 16 days the liver cells rupture, to release up to 400 000 merozoites, which invade the human host’s erythrocytes. The merozoites reproduce asexually in the erythrocytes before causing them to rupture and release yet more merozoites into the blood stream to invade yet more erythrocytes. Any mosquito that bites an infected person at this stage will ingest the parasites and the cycle will begin again. It is worth noting that P. vivax and P. ovale parasites can remain dormant in the liver, which explains why malarial symptoms can manifest months after return from an infected region.

Clinical symptoms

The most common symptom is fever, although it may initially present with chills, general malaise, nausea, vomiting and headache. Malaria should be considered as a differential diagnosis in anyone who presents with a febrile illness whilst in or recently left a malarious area. P. falciparum is unlikely to present more than 3 months after exposure but symptoms associated with P. vivax malaria can take up to a year to manifest themselves.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Effective bite prevention should be the first-line of defence against malarial infection. Total avoidance of being bitten is not practical and patients must ensure that protective measures from being bitten are always taken.

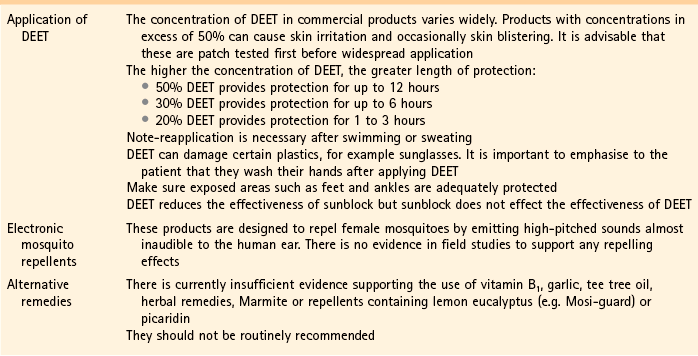

Insect repellents containing N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) in high concentrations is recommended (see Hints and Tips Box 10.4). In controlled laboratory studies DEET provides the longest protection compared to other products. Evidence for other insect repellents suggest they have comparable efficacy to low concentrations of DEET but have shorter duration of protection than DEET (Fradin & Day 2002).

Besides applying DEET, other preventative measures to reduce the chance of being bitten include wearing long, loose-fitting, sleeved shirts and trousers, especially at dawn and dusk. Protection of ankles appears to be particularly important. Hotel windows should be checked to make sure they have adequate screening, windows and doors should remain closed and ideally the bed should have a mosquito net. Mosquito nets do reduce the incidence of being bitten. Ideally they should be impregnated with insecticide as they are more effective than non-impregnated nets (Lengeler 2004). If the person is travelling to more remote areas they should purchase their own mosquito net that has been impregnated with an insecticide. There are a number of travel centres and specialist outdoor shops where such products, including insecticidal impregnated clothes, can be bought.

Chemoprophylaxis

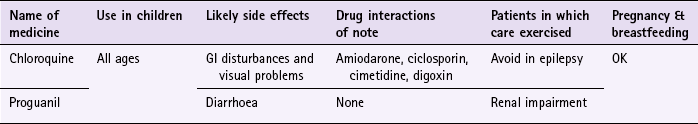

In addition to taking precautions to avoid being bitten, travellers should also take antimalarial medication. Chloroquine and proguanil are licensed for pharmacy sale when used for prophylaxis of malaria and have proven efficacy but drug resistance to these two medicines (e.g. chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum) is now widespread, and limits their usefulness.

It is important to check current guidelines for the destination the person is travelling to or through. Two easily available UK reference sources in which recommendations can be found are the British National Formulary and MIMS. In addition a number of organisations produce reference material (e.g. the National Pharmacy Association’s vaccination updates). In most instances the MIMS would be a first-line reference source as the guidelines are updated monthly (compared to the British National Formulary’s biannual publication) and are more likely to be still up to date. For people who are travelling to very high risk areas (usually sub-Saharan Africa or south-east Asia) or for long periods of time it might be better to refer the person to a specialist centre.

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to medicines for malaria reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 10.4; useful tips relating to patients travelling to regions where malaria is endemic are given in Hints and Tips Box 10.4.

Medicine regimens

Antimalarials need to be taken at least 1 week before departure, during the stay in the malaria endemic region and for 4 weeks on leaving the area. Taking the medication prior to departure allows the patient to know whether they are going to experience side effects and, if they do, still have enough time to obtain a different antimalarial before departure. It also helps to establish a medicine-taking routine that will, hopefully, help with compliance. Medicine taking for a further 4 weeks after leaving the region is to ensure that any possible infection that could have been contracted during the final days of the stay does not develop into malaria.

Chloroquine (e.g. Avloclor, Nivaquine)

Chloroquine, as a single agent, is now almost obsolete against P. falciparum but still remains effective against the other forms of malaria.

Adults and children over 13 should take 300 mg of chloroquine base each week; this is equivalent to two tablets. Chloroquine can be given to children of all ages and is based on a milligram per kilogram basis. Nivaquine is formulated as a syrup (50 mg of base/5 mL) and should be recommended for children because an accurate dose can be given according to their weight.

Chloroquine is associated with a number of side effects including nausea, vomiting, headaches and visual disturbances. Most patient groups, including pregnant women can take chloroquine, although it is contraindicated in epilepsy because it might lower the seizure threshold and tonic-clonics seizure have been reported with prophylactic doses. Patients with psoriasis might notice a worsening of their condition. Chloroquine should be avoided in patients taking amiodarone because there is a risk of QT prolongation and ventricular arrhythmia. It should also be avoided with ciclosporin (increased ciclosporin levels), cimetidine (increased chloroquine levels) and possibly digoxin (increased digoxin levels).

Proguanil (Paludrine)

Proguanil is always used in combination with chloroquine unless the patient is contraindicated from taking chloroquine. Adults and children over the age of 13 should take 200 mg (two tablets) daily. Like chloroquine, it can be given to children of all ages and the dose ideally should be on a milligram per kilogram basis. To aid compliance a travel pack suitable for adults on a 2-week holiday is available that combines 14 chloroquine tablets with 98 proguanil tablets. Side effects associated with proguanil are usually mild and include diarrhoea. Patients with known mild renal impairment should take 100 mg daily and the dose should be further reduced if renal impairment is moderate or severe.

References

Fradin, MS, Day, JF. Comparative efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:13–18.

Lengeler, C. Insecticide-treated bed nets and curtains for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004. [Issue 2. Art. No.: CD000363. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000363.pub2].

Fit for travel – provided by NHS Scotland. http://www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk/home.aspx

The National Travel Health Network and Centre. http://www.nathnac.org/travel/index.htm

Malaria Reference Laboratory. http://www.malaria-reference.co.uk

Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. http://www.liv.ac.uk/lstm

Bites and stings

Background

A whole host of animals (and plants) have the capacity to cause injury to the skin, and depending on the severity can result in systemic symptoms. The majority of cases are caused by insects and are of nuisance value.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The prevalence of bites and stings is largely unknown. Most people self-treat and never seek advice. Biting and stinging insects are generally more common in warmer climates, and in warmer months, with summer being the peak time.

Aetiology

Stinging insects are broadly defined as those that use some sort of venom as a defence mechanism or to immobilise their prey. Examples include bees, wasps and ants. The venom is usually ‘injected’ using a stinger and include proteins and substances that help break down cells and increase the penetration of the venom, e.g. phospholipase A and hyaluronidase. People can develop allergic reactions to these substances and, unlike most biting insects, can occasionally suffer significant reactions, including anaphylaxis, to stings. The severity of the reaction depends on the quantity of the venom injected and the person’s predisposition to hypersensitivity.

Biting insects are those that feed off the blood supply of humans and other creatures. They include mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas. Apart from having some sort of apparatus to draw the blood, these insects usually secrete anticoagulant-like substances to facilitate feeding. It is these anticoagulant substances that people will react to. However, it is only after repeated bites that sensitivity occurs.

Clinical features of bites and stings

Itching papules, which can be intense, is the hallmark symptom of insect bites. Weals, bullae and pain can occur, especially in sensitised individuals. Lesions are often localised and grouped together and occur on exposed areas, e.g. hands, ankles and face. Scratching can cause excoriation, which might lead to secondary infection. In contrast, stings are associated with intense burning pain. Erythema and oedema follow but usually subside within a few hours. If systemic symptoms are experienced, they occur within minutes of the sting.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Avoiding bites and stings in the first place is obviously important. This means using an effective insect repellant and avoiding times and places when insects are about. DEET is the most effective insect repellant and found in most commercial preparations. For avoidance measures and more information on DEET see page 323.

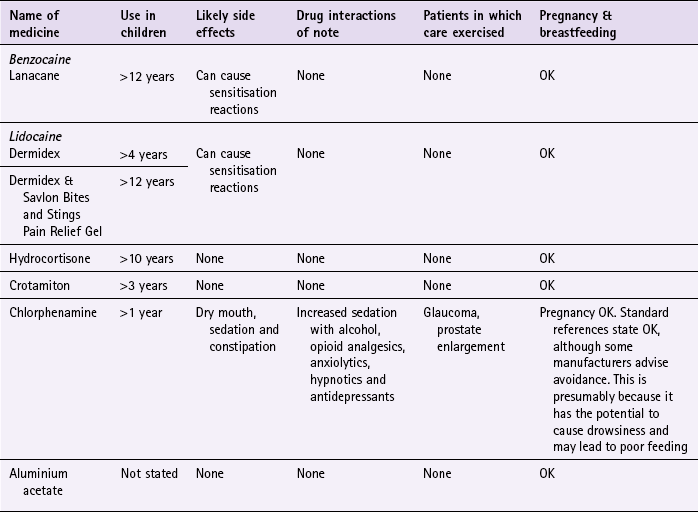

Topical OTC treatments for bites and stings include local anaesthetics, corticosteroids and antihistamines. For local anaesthetics, there is a lack of clinical data to support the use for stings and bites, either alone or in combination with antihistamines. However, their use in practice is well established as a local anaesthetic and is appropriate on theoretical grounds. Hydrocortisone, like lidocaine, has a lack of clinical data for bites and stings, but the use could be justified on theoretical grounds. Crotamiton is also marketed for conditions associated with itching. Prodigy guidance (February 2013) recommends crotamiton for local reactions to control itching, but there is a lack of evidence to support this and is based on expert opinion.

Stingose is a 20% aluminium acetate solution marketed for the treatment of bites and stings. The proposed mechanism of action is that aluminium ions cause denaturing of the proteins and bind polysaccharides in bites and stings resulting in inactivation of the venom. There are no randomised comparative or placebo controlled trials. However, a large case series of over 1000 patients found it to be effective in treating a range of marine, plant and animal bites and stings in over 99% of cases (Henderson & Easton 1980).

Antihistamines (both topical and systemic) have been used for their antipruritic properties. There are limited studies in the treatment of insect bites and stings. Some studies, with systemic antihistamines, have shown efficacy of the less sedating antihistamines for mosquito bites (Foëx & Lee 2006). They are probably most useful for their sedating properties when itching is disturbing sleep.

Practical prescribing and product selection

Prescribing information relating to products for bites and stings is reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 10.5.

Before OTC treatment is offered, the severity of symptoms should be assessed, because small local reactions can be managed primarily with topical products whereas large local reactions will generally require systemic treatment. Patients with systemic symptoms should be referred.

If the person has been stung and the stinger is still in situ then this should be removed. The best way of removal is to scrape the stinger away with a sharp edge (e.g. card or knife blade) or alternatively a finger nail.

Small local reactions

Local pain and swelling is best treated with cold compresses/ice and, if needed, oral pain killers (ibuprofen or paracetamol). Local itching can be treated with topical crotamiton or low potency corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 1%). If itching interferes with sleep then an oral sedating antihistamine might be helpful at night.

Large local reactions

Occasionally, severe pain and swelling can extend beyond the immediate surroundings of the lesion. They should be managed with oral pain killers and antihistamines.

Local anaesthetics (e.g. benzocaine (Lanacane), lidocaine (Dermidex & Savlon Vites and Stings Pain Relief Gel)): Local anaesthetics can be used in adults and children over 4 years (see Table 10.5) and are in general applied three times a day. They are safe to use in pregnancy and are generally well tolerated. Local anaesthetics are known to be skin sensitisers and can produce contact dermatitis.

Local anaesthetic/antihistamine combination (Wasp-Eze Spray): This product contains benzocaine 1% and mepyramine 0.5%. It can be used on people over the age of 2 years. The dose is one spray on to the affected area of skin for two to three seconds. This dose can be repeated after 15 minutes if required.

Hydrocortisone (e.g. Dermacort): Hydrocortisone is applied once or twice a day to the affected areas. It can be used in adults and children over 10 years of age. It can be used for a maximum of 7 days.

Sedating antihistamines (e.g. chlorphenamine): Chlorphenamine, as all antihistamines, are associated with sedation. They interact with other sedating medication, resulting in potentiation of the sedative properties of the interacting medicines. They also possess antimuscarinic side effects, which commonly result in dry mouth and possibly constipation. It is these antimuscarinic properties that mean patients with glaucoma and prostate enlargement should ideally avoid their use, because it could lead to increased intraocular pressure and precipitation of urinary retention.

Chlorphenamine (e.g. Piriton): Chlorphenamine can be given from the age of 1 year. Children up to the age 2 should take 2.5 mL of syrup (1 mg) twice a day. For children aged between 2 and 5 the dose is 2.5 mL (1 mg) three or four times a day and those over the age of 6 should take 5 mL (2 mg) three or four times a day. Adults should take 4 mg (one tablet) three or four times a day.

Crotamiton (Eurax): Adults and children over 3 years of age should apply crotamiton two or three times a day. A combination product containing hydrocortisone is available (Eurax HC) but is best avoided if possible. This is to decrease the exposure of patients to unnecessary corticosteroids and their potential adverse effects.

Aluminium acetate (Stingose): Aluminium acetate is safe to use with any age and comes in a spray and gel. It should be applied as soon as possible after the sting, and is unlikely to be effective if used more than 30 minutes after the sting or bite. It has no significant side effects. However, some local skin reactions are possible.

Coronary heart disease

Background

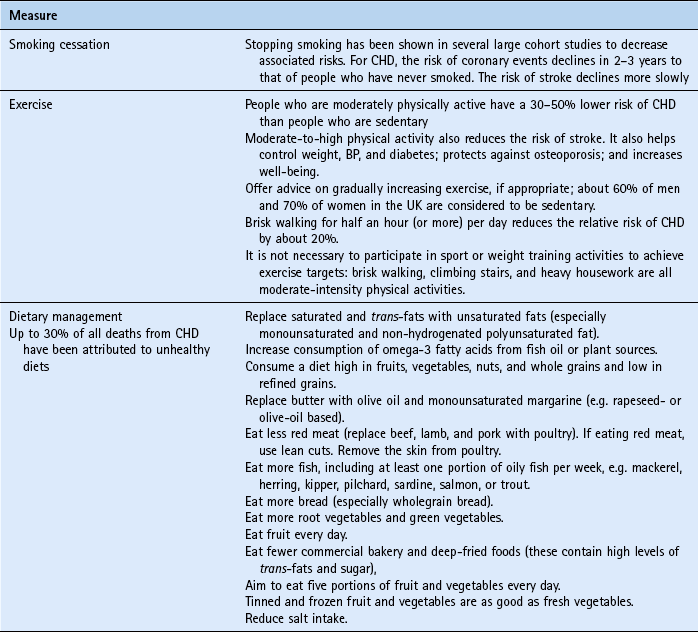

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the biggest preventable cause of mortality in the UK. In 2000, the UK government launched the National Service Framework (NSF) for CHD. This 10-year programme set ambitious targets to reduce the death rate from CHD, stroke and related diseases in people under 75 by at least 40% by 2010. The NSF prioritised interventions to those at greatest risk of CHD – all patients who have had an event (secondary prevention) and those who have a high risk of developing CHD (primary prevention). High risk is defined as a 10-year CHD event risk greater than 30%. The UK government has indicated that as resources permit this value should be lowered to 15%. Standard intervention for CHD includes: smoking cessation, reducing modifiable risk factors, controlling blood pressure to agreed targets and use of medication (especially statins for both primary and secondary prevention).

In 2004 simvastatin (Zocor Heart-Pro) was reclassified to pharmacy sale. The deregulation of simvastatin represented an important milestone for pharmacists because it was the first medicine to become available that targeted a chronic rather than acute condition. The intention of the reclassification was to target the moderate risk group (i.e. those the government have excluded – people with a 10–15% chance of developing CHD in the next 10 years). The deregulation of simvastatin was met with strong resistance from the medical profession and unenthusiastically received by community pharmacists. Consequently, sales of Zocor Heart-Pro were low and presumably was the basis for its discontinuation in 2010. Simvastatin is however still available through some multiple pharmacy chains (July 2012).

Prevalence and epidemiology

Figures for 2010 showed that 65 000 people in England died from CHD. Despite these alarming figures, CHD is in decline in the UK. For example, in people aged under 65 the number of deaths has fallen from approximately 80 deaths per 100 000 in 1980 to approximately 30 deaths per 100 000 in 2000. Much of this fall can be attributed to modifying risk factors (e.g. stopping smoking) and drug intervention. However, within the population there are major health inequalities. For example, people from lower social classes are more likely to suffer from CHD – working men in social class V (unskilled occupations) are 50% more likely to die than men in the population as a whole. People from some ethnic backgrounds have a much higher risk for developing CHD. In the UK, people of south Asian descent have a 40% greater risk of CHD than white people. Geography also plays a part with people from southern England having lower death rates than northern England and Scotland.

Aetiology

Atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries is responsible for CHD. This usually begins before adulthood and is a complex process. Exactly how atherosclerosis begins or what causes it is not known. Current thinking is the innermost layer of the artery (endothelium) becomes damaged. Over time fats, cholesterol, platelets, cellular debris and calcium are deposited in the artery wall. Collagen is synthesised and makes a fibrous cap around damaged tissue and is known as a plaque. This narrows the coronary artery and the reduced supply of oxygen to the heart muscle causes coronary ischaemia. This can present as angina, myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or sudden death.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Simvastatin was deregulated to OTC sale based on POM trial data. There have been no trials conducted with simvastatin on the group of patients that the OTC product is designed to target. However, based on evidence from clinical trials, simvastatin is considered likely to confer benefits in terms of reducing CHD events. It has been shown to lower low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol by about 27% in practice.

Practical prescribing and product selection

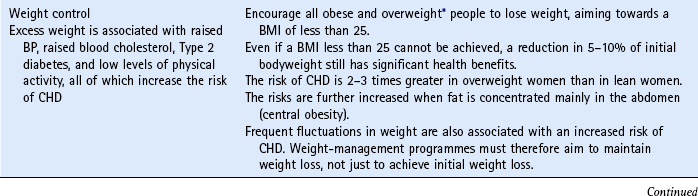

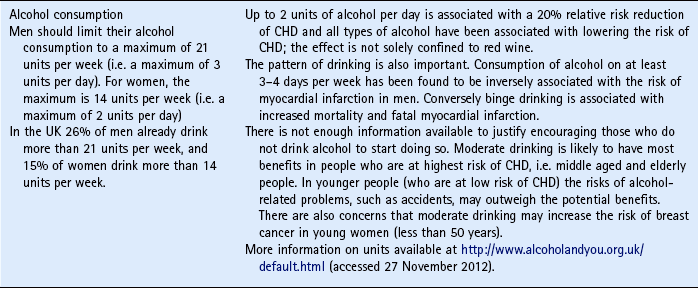

The pharmacist has an important role in getting people to understand the risk factors associated with CHD and what they can do to reduce their risk. The main advice to give people is summarised in Table 10.6.

Recommendation of simvastatin is not based on the person’s cholesterol measurements but on their risk factors. OTC sale of simvastatin can be made to:

• all men aged between 55 and 70 years

• men aged between 45 and 55, and women aged over 55, who have one or more of the following risk factors: family history of CHD, smoker, overweight or of South Asian family origin.

The dose is one tablet per day, preferably in the evening. It has very few side effects (even at high doses) and are classed as rare (>1/10 000, <1/1000), and include GI upset (e.g. abdominal pain, flatulence, nausea and vomiting) and central nervous system effects such as dizziness, blurred vision and headache. Simvastatin can also cause reversible myositis (unexplained generalised muscle pain, tenderness or weakness not associated with flu, exercise or recent strain or injury) and if suspected treatment should be discontinued. It can interact with other fibrates, azole antifungals, ciclosporin, nefazadone and macrolide antibiotics (increased risk of myopathy). It also can affect warfarin levels and should not be given with grapefruit juice (grapefruit juice inhibits cytochrome P450 3A4 and increases simvastatin levels).

Simvastatin is not intended for those who are known to have existing CHD, diabetes, history of stroke or peripheral vascular disease, familial hypercholesterolaemia or hypertension. These people should be referred to their GP.

UK Department of Health information on CHD. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Policyandguidance/Healthandsocialcaretopics/Coronaryheartdisease/index.htm

Weight loss

Background

Obesity is a growing epidemic, particularly in Western countries. As a consequence the risk of diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease are also increasing, resulting in a situation where the current and future generations could have a shorter life span than their parents. Although a number of measures of obesity have been proposed, the internationally accepted measure is the body mass index (BMI). This is calculated as the weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). A BMI of over 25 is classified as overweight and for obesity the value is 30.

Prevalence and epidemiology

In 2010, just over a quarter of adults (26%) in England were classified as obese and is almost double the values seen in 1993. Figures are even higher for those classed as overweight – 42% of men 32% of women. This equates to 63% of adults being overweight or obese. Figures for Wales and Scotland are similar.

Aetiology

Although a number of causes of obesity have been proposed, and genetics may play an important role, for a significant proportion of the population it results from an imbalance between energy intake (food and beverages) and energy expenditure (exercise). Other factors associated with obesity include cultural norms, socioeconomic status, gender and ethnicity. See Hints and Tips Box 10.5 for guidance on weight loss.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Diet and exercise are still considered the first-line treatment of obesity. Orlistat inhibits pancreatic and gastric lipase, which reduces the absorption of fat from the gut. Clinical trials have shown that orlistat produces a modest weight loss of approximately 5–10% of body weight (Hill et al 1999). The best results with orlistat are seen in the short term (6–12 months); long-term results rely heavily on lifestyle changes.

Practical prescribing and product selection

Orlistat is indicated for weight loss in adults (18 or over) who are overweight (body mass index ≥28 kg/m2) and should be taken in conjunction with a mildly hypocaloric, lower-fat diet.

The recommended dose of orlistat is one 60 mg capsule three times daily. The capsule should be taken immediately before, during or up to 1 hour after each main meal. If a meal is missed or contains no fat, the dose of orlistat should not be taken. If weight loss has not been achieved after 12 weeks then the patient should stop taking orlistat.

Side effects are largely GI and include faecal urgency and incontinence, oily evacuation and spotting, flatus and abdominal pain. These can be minimised by restricting fat intake to less than 20 g per meal. Supplementation with fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K) is recommended and can be achieved by taking a multivitamin. Because of the effect on vitamin K levels, patients on warfarin should avoid using orlistat. Orlistat may decrease ciclosporin levels and requires close monitoring. There is limited data of orlistat being used in pregnant and breastfeeding women and is therefore not recommended.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (symptoms of)

Background

Tamsulosin was reclassified from POM to P in the UK in spring 2010. This represents the first UK medicine to treat a chronic, progressive symptomatic condition available without a prescription. This deregulation is also notable for the fact that it may encourage men to take more of an interest in their welfare through community pharmacies, especially as the majority of men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) do not consult their doctor when experiencing symptoms.

Prevalence and epidemiology

Men over the age of 50, commonly experience lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). It is estimated that 30% suffer from symptoms, with the commonest cause being benign prostatic enlargement.

Aetiology

LUTS in men can be caused by structural or functional abnormalities in one or more parts of the lower urinary tract. Often the prostate gland is enlarged, which places pressure on the bladder and urethra. Symptoms can also be caused via peripheral or central nervous system abnormalities that affect control of the bladder and sphincter.

Lower urinary tract symptoms

Patients will present with a range of symptoms, typically symptoms such as hesitancy, weak stream and urgency. Symptoms are often classified as being either ‘obstructive’ or irritative’. Obstructive symptoms are related to bladder emptying and experienced by the patient as incomplete emptying, intermittency and straining. Patients may use terms such as ‘stopping and starting’ or ‘dribbling’. Irritative symptoms are related to bladder filling and involve increased frequency, urgency and nocturia. These symptoms, along with issues affecting quality of life are used in the manufacturer’s ‘Symptoms check Questionnaire’.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Studies show that tamsulosin is significantly better than placebo in improving urinary flow and reducing symptoms. Tamsulosin is an alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonist blocker that binds selectively and competitively to postsynaptic alpha1-receptors, in particular to the subtype alpha1a. Alpha1-blockers relax smooth muscle in BPH producing an increase in urinary flow-rate and an improvement in obstructive symptoms.

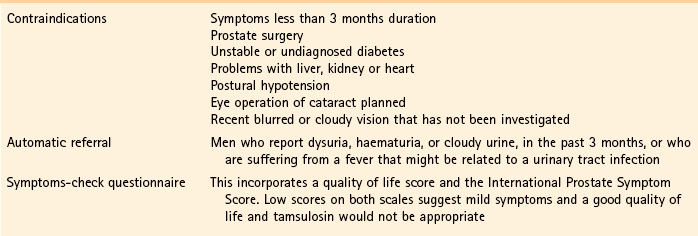

Practical prescribing and product selection

Tamsulosin is indicated for treatment of functional symptoms of BPH in men aged 45 to 75 years old. Men presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms, who appear to be suitable for OTC tamsulosin (see Hints and Tips Box 10.6) can be supplied an initial 14-day supply. Patients must be told that they will have to see a doctor for confirmation of the cause of their symptoms. If this takes longer than the supply of 14 days treatment then the pharmacist can provide a further 28 days treatment. In addition, if symptoms have not improved within 14 days of starting treatment, or are getting worse, the patient should stop taking tamsulosin and be referred to a doctor.

A maximum of 6 weeks treatment of tamsulosin can be supplied without an assessment by a doctor. If long-term OTC treatment is deemed appropriate then every 12 months, the patient should consult a doctor for a clinical review.

The dose is 400 µg daily (one capsule). Dizziness is the most frequently reported side effect (1.3% of patients). Other less common side effects reported include GI disturbances, headache and rash. As it is alpha-blocker it should not be given to patients receiving antihypertensive medicines with significant alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonist activity (e.g. doxazosin, indoramin, prazosin, terazosin and verapamil).

Royal Pharmaceutical Society Guidance. http://www.rpharms.com/practice–science-and-research-full-guidance/otc-tamsulosin-full-guidance.asp

OTC tamsulosin: Information for pharmacists – Implementing NICE guidance. http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=nice%20tamsulosin&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CFMQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.nice.org.uk%2Fnicemedia%2Flive%2F12984%2F48572%2F48572.doc&ei=IfcXUM6yL4fI0QX58oD4Dg&usg=AFQjCNEtTWWBC-SsnOoUtpvGMlcxAroX6g

Prostate Help Association. www.prostatehelp.me.uk

Chlamydia treatment

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common sexually transmitted bacterial infection in the UK, and the incidence is increasing and in part due to it being asymptomatic. At least 70% of women and 50% of men infected are asymptomatic. In 2010, young people, aged less than 25 years, accounted for 65% of chlamydia diagnoses. In response to the growing problem, the DoH introduced the National Chlamydia Screening Programme (http://www.chlamydiascreening.nhs.uk/; accessed 27 November 2012).

Practical prescribing and product selection

Azithromycin was reclassified in 2008. It is indicated for men and women 16 years of age or older who are asymptomatic and have tested positive for genital chlamydia infection. It is also indicated for treatment of their sexual partners without the need for a test. The dose is a single stat. dose of 1 g (2 × 500 mg tablets). Side effects that might be experienced are GI upset, namely nausea, vomiting and abdominal discomfort.

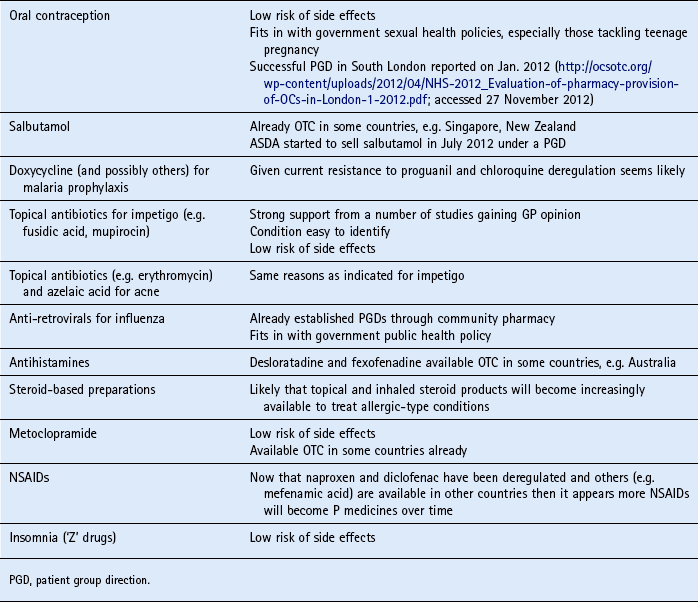

Future deregulations

Current UK government policy promotes self-care and consistently advocates the greater deregulation of medicines. However, the number of POM to P deregulations in the last few years has slowed. There have been a number of reasons cited for the recent lack of POM to P switches, which include over burdensome regulatory processes. This is evidenced by just nine switches between 2009 and 2012, with only orlistat, tranexamic acid and tamsulosin coming from new therapeutic classes. Recent applications for oral antibiotics (trimethoprim and nitrofurantoin to treat uncomplicated cystitis in women) were ultimately withdrawn in 2010 due to concerns over increasing antibiotic resistance. It appears that, for the time being, oral antibiotics, other than azithromycin will not be deregulated from POM control. Looking to the immediate future, it seems likely that more medicines to treat acute conditions will become P medicines.

Table 10.7 highlights some future candidates that are potential POM to P switches.

The following questions are intended to supplement the text. Two levels of questions are provided; multiple choice questions and case studies. The multiple choice questions are designed to test factual recall and the case studies allow knowledge to be applied to a practice setting.

Multiple choice questions

10.1. Which antihistamine used for motion sickness is subject to abuse?

10.2. What is the main side effect of Levonelle® One step?

10.3. In which group of the population is smoking on the increase?

10.4. Which patients should use 24-h patches?

a. People who smoke more than 20 cigarettes a day

b. People who smoke more than 40 cigarettes a day

c. People who need a cigarette within 20 minutes of waking up

10.5. Which dermatological condition can be worsened by taking chloroquine?

10.6. How long after unprotected sex can EHC be given?

10.7. What is regarded as the most important smoking-related disease?

10.8. Patients with which condition should care be taken when recommending promethazine for motion sickness?

Questions 10.9 to 10.11 concern the following NRT products:

Select, from A to E, which of the above products:

10.9. Is most suitable for patients in which compliance may be an issue

10.10. Delivers constant levels of plasma nicotine

10.11. Is useful for those people who need to have their hands occupied

Questions 10.12 to 10.14 concern the following medicines:

Select, from A to E, which of the above medicines:

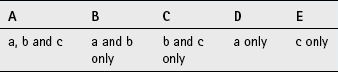

Questions 10.15 to 10.17: for each of these questions one or more of the responses is (are) correct. Decide which of the responses is (are) correct. Then choose:

10.15. When using DEET, the following rule(s) should be followed:

10.16. Plasmodium falciparum is associated with:

a. High levels of drug resistance

b. The highest incidence of death compared to other forms of malaria

10.17. What side effects can be seen in patients chewing nicotine gum?

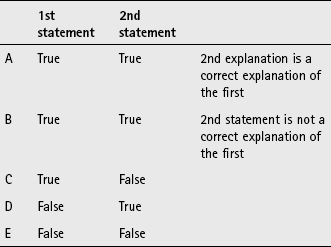

Questions 10.18 to 10.20: these questions consist of a statement in the left-hand column followed by a statement in the right-hand column. You need to:

A If both statements are true and the second statement is a correct explanation of the first statement

B If both statements are true but the second statement is NOT a correct explanation of the first statement

C If the first statement is true but the second statement is false

D If the first statement is false but the second statement is true

| First statement | Second statement |

| 10.18 Antimalarials have to be taken before travel | Side effects may preclude patients from taking antimalarials |

| 10.19 Malaria can be contracted months after return from an endemic area | The liver holds a reservoir of parasites that are hard to eradicate |

| 10.20 Pregnancy is a contraindication for malaria prophylaxis | Infants cannot take antimalarials |

a tablet. As Jessica has narcolepsy it is necessary to see if she takes any medication to help with the condition. If she does then checks would have to be made to ensure that Jessica could still take hyoscine.

a tablet. As Jessica has narcolepsy it is necessary to see if she takes any medication to help with the condition. If she does then checks would have to be made to ensure that Jessica could still take hyoscine.