Cysts and Cystlike Lesions of the Jaws

A cyst is a pathologic cavity filled with fluid, lined by epithelium, and surrounded by a definite connective tissue wall. The cystic fluid either is secreted by the cells lining the cavity or derives from the surrounding tissue fluid.

Clinical Features

Cysts occur more often in the jaws than in any other bone because most cysts originate from the numerous rests of odontogenic epithelium that remain after tooth formation. Cysts are radiolucent lesions, and the prevalent clinical features are swelling, lack of pain (unless the cyst becomes secondarily infected or is related to a nonvital tooth), and association with unerupted teeth, especially third molars.

Radiographic Features

Cysts may occur centrally (within bone) in any location in the maxilla or mandible but are rare in the condyle and coronoid process. Odontogenic cysts are found most often in the tooth-bearing region. In the mandible, they originate above the inferior alveolar nerve canal. Odontogenic cysts may grow into the maxillary antrum. Some nonodontogenic cysts also originate within the antrum (see Chapter 27). A few cysts arise in the soft tissues of the orofacial region.

PERIPHERY

Cysts that originate in bone usually have a periphery that is well defined and corticated (characterized by a fairly uniform, thin, radiopaque line). However, a secondary infection or a chronic state can change this appearance into a thicker, more sclerotic boundary or make the cortex less apparent.

SHAPE

Cysts usually are round or oval, resembling a fluid-filled balloon. Some cysts may have a scalloped boundary.

INTERNAL STRUCTURE

Cysts often are totally radiolucent. However, long-standing cysts may have dystrophic calcification, which can give the internal aspect a sparse, particulate appearance. Some cysts have septa, which produce multiple loculations separated by these bony walls or septa. Cysts that have a scalloped periphery may appear to have internal septa. Occasionally the image of bony ridges produced by the peripheral scalloping are positioned so that their image overlaps the internal aspect of the cyst, giving the false impression of internal septa.

EFFECTS ON SURROUNDING STRUCTURE

Cysts grow slowly, sometimes causing displacement and resorption of teeth. The tooth resorption often has a sharp, curved shape. Cysts can expand the mandible, usually in a smooth, curved manner, and change the buccal or lingual cortical plate into a thin cortical boundary. Cysts may displace the inferior alveolar nerve canal in an inferior direction or invaginate into the maxillary antrum, maintaining a thin layer of bone that separates the internal aspect of the cyst from the antrum.

Odontogenic Cysts

Definition

A radicular cyst is a cyst that most likely results when rests of epithelial cells (Malassez) in the periodontal ligament are stimulated to proliferate and undergo cystic degeneration by inflammatory products from a nonvital tooth.

Clinical Features

Radicular cysts are the most common type of cyst in the jaws. They arise from nonvital teeth (i.e., teeth that have lost vitality because of extensive caries, large restorations, or previous trauma). Often radicular cysts produce no symptoms unless secondary infection occurs. A cyst that becomes large may cause swelling. On palpation the swelling may feel bony and hard if the cortex is intact, crepitant as the bone thins, and rubbery and fluctuant if the outer cortex is lost. The incidence of radicular cysts is greater in the third to sixth decades and shows a slight male predominance.

Radiographic Features

Location.: In most cases the epicenter of a radicular cyst is located approximately at the apex of a nonvital tooth (Fig. 21-1). Occasionally it appears on the mesial or distal surface of a tooth root, at the opening of an accessory canal, or infrequently in a deep periodontal pocket. Most radicular cysts (60%) are found in the maxilla, especially around incisors and canines. Because of the distal inclination of the root, cysts that arise from the maxillary lateral incisor may invaginate the antrum. Radicular cysts may also form in relation to a nonvital deciduous molar and be positioned buccal to the developing bicuspid.

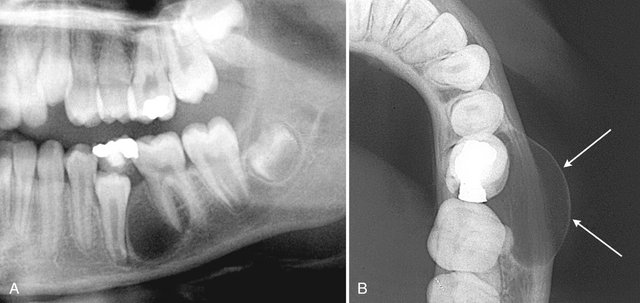

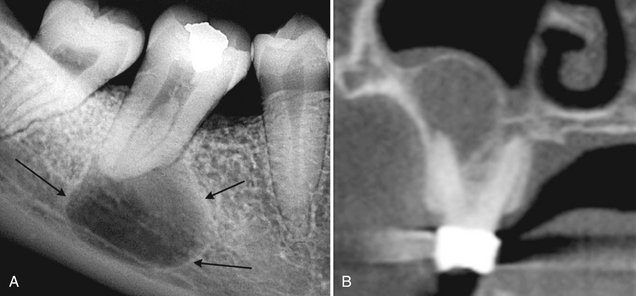

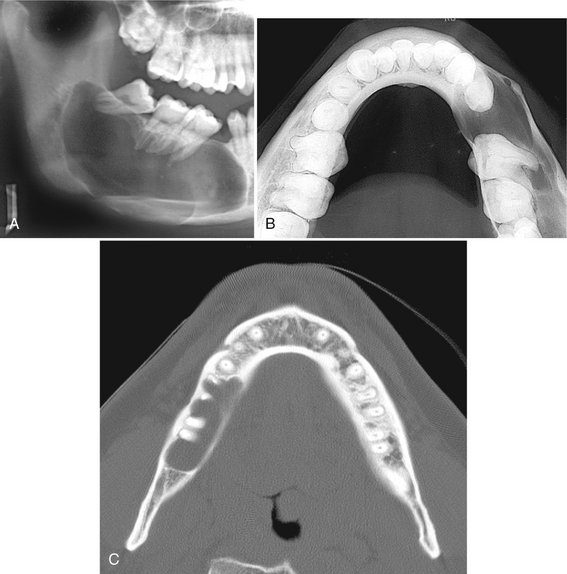

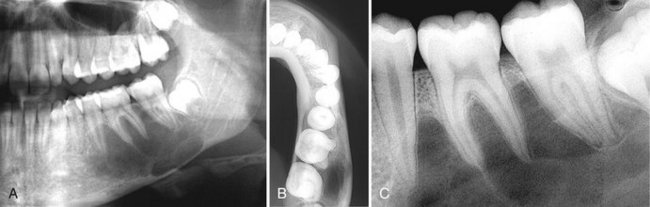

FIG. 21-1 Radicular cysts.

In A note that the epicenter is apical to the lateral incisor and the presence of a peripheral cortex (arrows). In B note the lack of a well-defined peripheral cortex because this cyst was secondarily infected and that the root canal of the lateral incisor is abnormally wide and it is visible at the root apex.

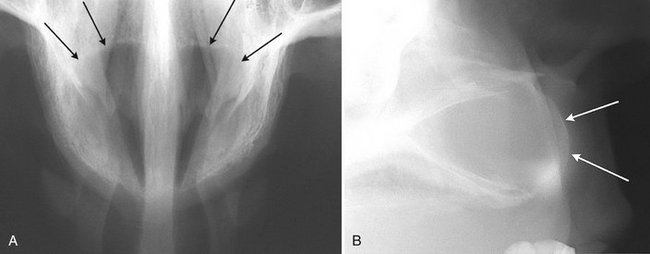

Periphery and Shape.: The periphery usually has a well-defined cortical border (Fig. 21-2). If the cyst becomes secondarily infected, the inflammatory reaction of the surrounding bone may result in loss of this cortex (see Fig. 21-1, B) or alteration of the cortex into a more sclerotic border. The outline of a radicular cyst usually is curved or circular unless it is influenced by surrounding structures such as cortical boundaries.

FIG. 21-2 A, A periapical film of a radicular cyst reveals a lesion with a well-defined cortical boundary (arrows). Note that the presence of the inferior cortex of the mandible has influenced the circular shape of the cyst. B, A coronal cone beam CT image of a radicular cyst related to the buccal root of a maxillary molar. Note the circular shape of the cyst as it invaginates the maxillary sinus. (Courtesy Dr. Bernard Friedland, Harvard University.)

Internal Structure.: In most cases the internal structure of radicular cysts is radiolucent. Occasionally, dystrophic calcification may develop in long-standing cysts, appearing as sparsely distributed, small particulate radiopacities.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: If a radicular cyst is large, displacement and resorption of the roots of adjacent teeth may occur. The resorption pattern may have a curved outline. In rare cases the cyst may resorb the roots of the related nonvital tooth. The cyst may invaginate the antrum, but there should be evidence of a cortical boundary between the contents of the cyst and the internal structure of the antrum (Fig. 21-2, B). The outer cortical plates of the maxilla or mandible may expand in a curved or circular shape (Fig. 21-3). Cysts may displace the mandibular alveolar nerve canal in an inferior direction.

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiation of a small radicular cyst from an apical granuloma may be difficult and in some cases impossible. A round shape, a well-defined cortical border, and a size greater than 2 cm in diameter are more characteristic of a cyst. Other periapical radiolucencies to consider are an early stage of periapical cemental dysplasia and an apical scar or a surgical defect because in such cases, normal bone may never fill in the defect completely. The patient’s history helps with the differentiation. Radicular cysts that originate from the maxillary lateral incisor and are positioned between the roots of the lateral incisor and the cuspid may be difficult to differentiate from an odontogenic keratocyst or a lateral periodontal cyst. The vitality of the involved tooth should be tested. A nonvital tooth may have a larger pulp chamber than neighboring teeth because of the lack of secondary dentin, which normally forms with time in the pulp chamber and canal of a vital tooth (see Fig. 21-1).

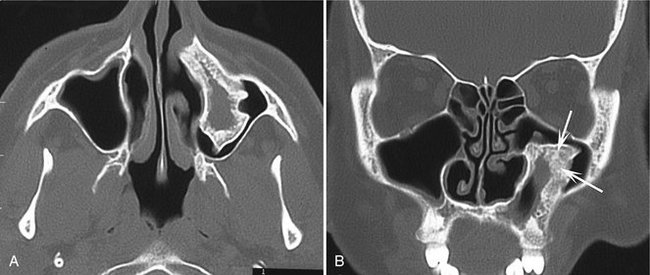

A large radicular cyst that has invaginated the maxillary antrum may collapse and start filling in with new bone (Fig. 21-4). With biopsy, the histologic analysis may result in an erroneous diagnosis of ossifying fibroma or a benign fibro-osseous lesion. Radiographically, the important feature is that the new bone always forms first at the periphery of the cyst wall as the cyst shrinks and not in the center of the cyst; this is a different pattern of bone formation than is seen with benign fibro-osseous lesions.

FIG. 21-4 Axial (A) and coronal (B) CT images with use of a bone algorithm of a collapsing radicular cyst within the sinus. Note the unusual shape and the fact that new bone is being formed from the periphery (arrows) toward the center. (Courtesy Drs. S. Ahing and T. Blight, University of Manitoba.)

Management

Treatment of a tooth with a radicular cyst may include extraction, endodontic therapy, and apical surgery. Treatment of a large radicular cyst usually involves surgical removal or marsupialization. The radiographic appearance of the periapical area of an endodontically treated tooth should be checked periodically to make sure that normal healing is occurring (Fig. 21-5). Characteristically, new bone grows into the defect from the periphery, sometimes resulting in a radiating pattern resembling the spokes of a wheel. However, in a few cases normal bone may not completely fill the defect, especially if a secondary infection or a considerable amount of bone destruction, including the buccal and lingual cortical plates, has occurred. Recurrence of a radicular cyst is unlikely if it has been removed completely.

Definition

A residual cyst is a cyst that remains after incomplete removal of the original cyst. The term residual is used most often for a radicular cyst that may be left behind, most commonly after extraction of a tooth.

Clinical Features

A residual cyst usually is asymptomatic and often is discovered on radiographic examination of an edentulous area. However, there may be some expansion of the jaw or pain in the case of secondary infection.

Radiographic Features

Location.: Residual cysts occur in both jaws, although they are found slightly more often in the mandible. The epicenter is positioned in the former periapical region of the involved and missing tooth. In the mandible the epicenter is always above the inferior alveolar nerve canal (Fig. 21-6).

Periphery and Shape.: A residual cyst has a cortical margin unless it becomes secondarily infected. Its shape is oval or circular.

Differential Diagnosis

Without the patient’s history and previous radiographs, the clinician may have difficulty determining whether a solitary cyst in the jaws is a residual cyst. Other examples of common solitary cysts include odontogenic keratocysts. A residual cyst has greater potential for expansion compared with an odontogenic keratocyst. The epicenter of a Stafne developmental salivary gland defect is located below the mandibular canal (and thus is unlikely to be odontogenic in nature).

Management

The treatment for residual cysts is surgical removal or marsupialization, or both, if the cyst is large.

Definition

A dentigerous cyst is a cyst that forms around the crown of an unerupted tooth. It begins when fluid accumulates in the layers of reduced enamel epithelium or between the epithelium and the crown of the unerupted tooth. An eruption cyst is the soft tissue counterpart of a dentigerous cyst.

Clinical Features

Dentigerous cysts are the second most common type of cyst in the jaws. They develop around the crown of an unerupted or supernumerary tooth. The clinical examination reveals a missing tooth or teeth and possibly a hard swelling, occasionally resulting in facial asymmetry. The patient typically has no pain or discomfort. Dentigerous cysts around supernumerary teeth account for about 5% of all dentigerous cysts, most developing around a mesiodens in the anterior maxilla.

Radiographic Features

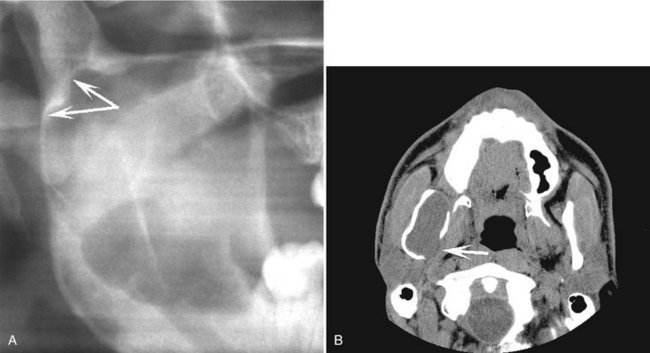

Location.: The epicenter of a dentigerous cyst is found just above the crown of the involved tooth, most commonly the mandibular or maxillary third molar or the maxillary canine (Fig. 21-7). An important diagnostic point is that this cyst attaches at the cementoenamel junction. Some dentigerous cysts are eccentric, developing from the lateral aspect of the follicle so that they occupy an area beside the crown instead of above the crown (see Fig. 21-7, D). Cysts related to maxillary third molars often grow into the maxillary antrum and may become quite large before they are discovered. Cysts attached to the crown of mandibular molars may extend a considerable distance into the ramus.

Periphery and Shape.: Dentigerous cysts typically have a well-defined cortex with a curved or circular outline. If infection is present, the cortex may be missing.

Internal Structure.: The internal aspect is completely radiolucent except for the crown of the involved tooth.

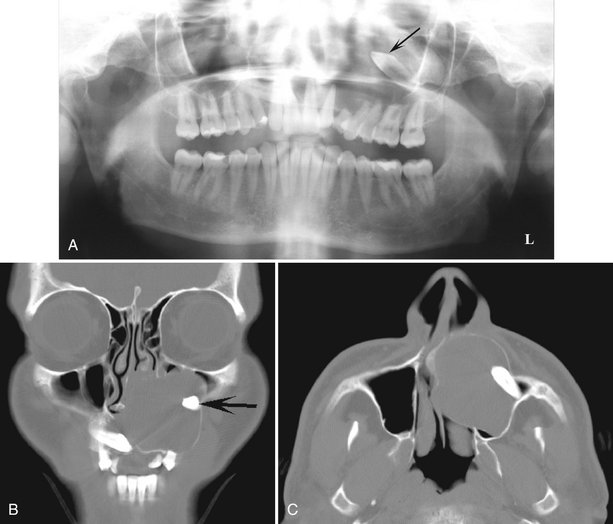

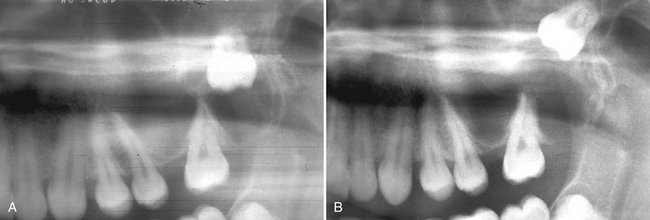

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: A dentigerous cyst has a propensity to displace and resorb adjacent teeth (Figs. 21-7 and 21-8). It commonly displaces the associated tooth in an apical direction (Fig. 21-9). The degree of displacement may be considerable. For instance, maxillary third molars or cuspids may be pushed to the floor of the orbit (see Fig. 21-8), and mandibular third molars may be moved to the condylar or coronoid regions or to the inferior cortex of the mandible. The floor of the maxillary antrum may be displaced as the cyst invaginates the antrum (Fig. 21-10), and the cyst may displace the inferior alveolar nerve canal in an inferior direction. This slow-growing cyst often expands the outer cortical boundary of the involved jaw.

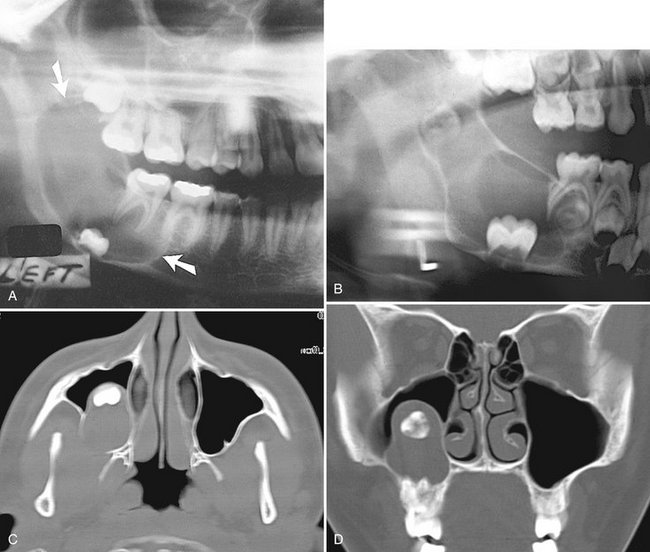

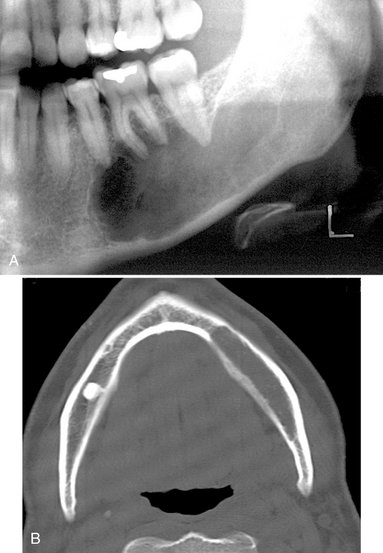

FIG. 21-8 A, This panoramic image reveals the presence of a large dentigerous cyst associated with the left maxillary cuspid (arrow), which has been displaced. Notice the displacement and resorption of other teeth in the left maxilla. B and C, Coronal and axial CT images of the same case showing superior-lateral displacement of the cuspid, expansion of the anterior wall of the maxilla, and expansion of the cyst into the nasal fossa.

FIG. 21-9 A and B, These panoramic films of the same case taken several years apart demonstrate superior-posterior displacement of a maxillary third molar by a dentigerous cyst.

FIG. 21-10 Dentigerous cysts displacing teeth. A, The third molar has been displaced to the inferior cortex. B, The developing second molar has been displaced into the ramus by a cyst associated with the first molar. Axial (C) and coronal (D) CT images with bone algorithm reveal a maxillary third molar displaced into the space occupied by the maxillary antrum; note the presence of a cortex between the cyst and the antrum.

Differential Diagnosis

Because the histopathologic appearance of the lining epithelium is not specific, the diagnosis relies on the radiographic and surgical observation of the attachment of the cyst to the cementoenamel junction. However, histopathologic examination must always be done to eliminate other possible lesions in this location.

One of the most difficult differential diagnoses to make is between a small dentigerous cyst and a hyperplastic follicle. A cyst should be considered with any evidence of tooth displacement or considerable expansion of the involved bone. The size of the normal follicular space is 2 to 3 mm. If the follicular space exceeds 5 mm, a dentigerous cyst is more likely. If uncertainty remains, the region should be reexamined in 4 to 6 months to detect any increase in size or any influence on surrounding structures characteristic of cysts.

The differential diagnosis also may include an odontogenic keratocyst, an ameloblastic fibroma, and a cystic ameloblastoma. An odontogenic keratocyst does not expand the bone to the same degree as a dentigerous cyst, is less likely to resorb teeth, and may attach further apically on the root instead of at the cementoenamel junction. It may not be possible to differentiate a small ameloblastic fibroma or cystic ameloblastoma from a dentigerous cyst if there is no internal structure. Other rare lesions that may have a similar pericoronal appearance are adenomatoid odontogenic tumors and calcified odontogenic cysts, both of which can surround the crown and root of the involved tooth. Evidence of a radiopaque internal structure should be sought in these two lesions. Occasionally a radicular cyst at the apex of a primary tooth surrounds the crown of the developing permanent tooth positioned apical to it, giving the false impression of a dentigerous cyst associated with the permanent tooth. This occurs most often with the mandibular deciduous molars and the developing bicuspids. In these cases the clinician should look for extensive caries or large restorations in a primary tooth that would indicate a radicular cyst.

Management

Dentigerous cysts are treated by surgical removal, which may include the tooth as well. Large cysts may be treated by marsupialization before removal. The cyst lining should be submitted for histologic examination because ameloblastomas have been reported to occur in the cyst lining. In addition, squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to arise from the cyst lining of chronically infected cysts. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma also has been reported.

Definition

The source of epithelium probably is the epithelial cell rests in the periodontal membrane of the buccal bifurcation of mandibular molars. The histopathologic characteristics of the lining are not distinctive. The etiology of proliferation is unknown; one theory holds that inflammation is the stimulus, but inflammation is not always present. The World Health Organization includes these cysts under inflammatory cysts.

It is possible that the paradental cyst of the third molar and the buccal bifurcation cyst (BBC) (associated with first and second molars) are the same entity. The BBC is certainly a distinct clinical entity. An associated enamel extension into the furcation region of third molars with paradental cysts has not been documented with molars involved in a BBC. Also, the inflammatory component associated with paradental cysts is not always present with BBCs.

Clinical Features

A common sign is the lack of or a delay in eruption of a mandibular first or second molar. On clinical examination the molar may be missing or the lingual cusp tips may be abnormally protruding through the mucosa, higher than the position of the buccal cusps. The first molar is involved more frequently than is the second molar. The teeth are always vital. A hard swelling may occur buccal to the involved molar, and if it is secondarily infected, the patient has pain. The age of detection is younger, within the first two decades for a BBC rather than the third decade with a paradental cyst of the third molar.

Radiographic Features

Location.: The mandibular first molar is the most common location of a BBC, followed by the second molar. The cyst occasionally is bilateral. It is always located in the buccal furcation of the affected molar (Fig. 21-11). On periapical and panoramic films the lesion may appear to be centered a little distal to the furcation of the involved tooth.

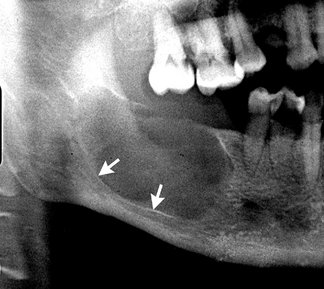

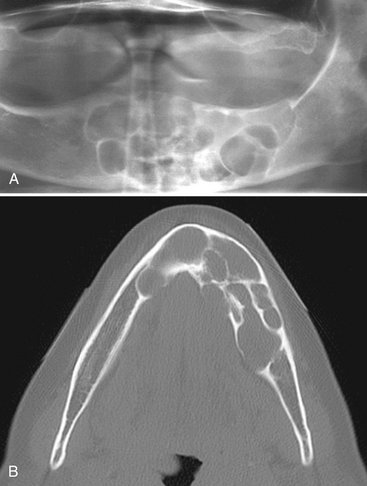

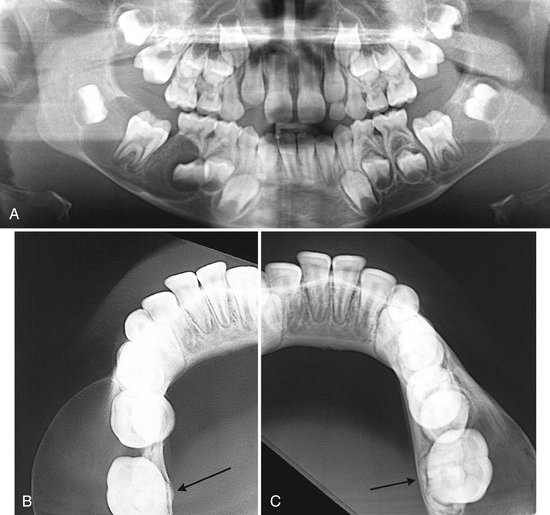

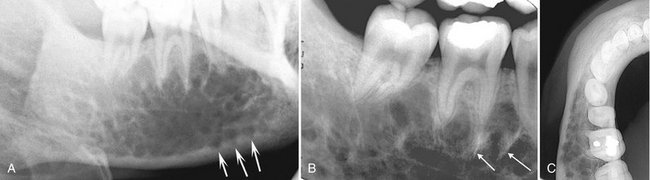

FIG. 21-11 Bilateral Buccal Bifurcation Cysts.

A, A panoramic image showing cysts related to the mandibular first molars. The occlusal surface of each tooth has been tipped in relation to the other teeth and adjacent teeth have been displaced. B and C, Occlusal films of the same case. Note the smooth curved expansion of the buccal cortex and the displacement of the roots of the first molars into the lingual cortical plate (arrows).

Periphery and Shape.: In some cases the periphery is not readily apparent, and the lesion may be a very subtle radiolucent region superimposed over the image of the roots of the molar. In other cases the lesion has a circular shape with a well-defined cortical border. Some cysts can become quite large before they are detected.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: The most striking diagnostic characteristic of a BBC is the tipping of the involved molar so that the root tips are pushed into the lingual cortical plate of the mandible (see Fig. 21-11, B and C) and the occlusal surface is tipped toward the buccal aspect of the mandible (see Fig. 21-11, A). This accounts for the lingual cusp tips being positioned higher than the buccal tips. This tipping may be detected in a panoramic or periapical film if the image of the occlusal surface of the affected tooth is apparent whereas the unaffected teeth are not. The best diagnostic film is the cross-sectional (standard) mandibular occlusal projection, which demonstrates the abnormal position of the tooth roots. If the cyst is large enough, it may displace and resorb the adjacent teeth and cause a considerable amount of smooth expansion of the buccal cortical plate. If the cyst is secondarily infected, periosteal new bone formation is seen on the buccal cortex adjacent to the involved tooth (Fig. 21-12).

FIG. 21-12 Occlusal views of two examples of buccal bifurcation cysts that have been secondarily infected; note the laminated periosteal new bone formation on the buccal aspect of the first molars and also the abnormal position of the roots of the first molar in B. (Courtesy Dr. Doug Stoneman, University of Toronto.)

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a BBC relies entirely on clinical and radiographic information. The major differential diagnosis includes lesions that could elicit an inflammatory periosteal response on the buccal aspect of mandibular molars, such as a periodontal abscess or Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (see Fig. 21-12). The fact that only a BBC tilts the molar as described helps to differentiate it from other lesions. Also in the differential diagnosis is the dentigerous cyst. However, the epicenter of a dentigerous cyst is different because a BBC starts near the bifurcation region of the tooth and does not surround the crown, as does a dentigerous cyst.

Management

A BBC usually is removed by conservative curettage, although some cases have resolved without intervention. The involved molar should not be removed. BBCs do not recur.

Definition

The World Health Organization has reclassified this cystic lesion into a unicystic or multicystic odontogenic tumor on the basis of the tumorlike characteristics of the lining epithelium. Because the gross and radiographic appearance of keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KOT) is cystic in nature, this neoplasm is presented in this chapter. Unlike most cysts, which are thought to grow solely by osmotic pressure, the epithelium in the KOT appears to have innate growth potential, consistent with a benign tumor. This difference in the mechanism of growth gives KOT a different radiographic appearance from cysts. The epithelial lining is distinctive also because it is keratinized (hence the name) and thin (four to eight cells thick). Occasionally budlike proliferations of epithelium grow from the basal layer into the adjacent connective tissue wall. Also, islands of epithelium in the wall may give rise to satellite microcysts. The inside of the cyst often contains a viscous or cheesy material derived from the epithelial lining.

Clinical Features

KOTs account for about one tenth of all cystic lesions in the jaws. They occur in a wide age range, but most develop during the second and third decades, with a slight male predominance. The cysts sometimes form around an unerupted tooth. KOTs usually have no symptoms, although mild swelling may occur. Pain may occur with secondary infection. Aspiration may reveal a thick, yellow, cheesy material (keratin). It is important to note that, unlike cysts, KOTs have a high propensity for recurrence, possibly because of small satellite cysts or fragments of epithelium left behind after surgical removal of the cyst.

Radiographic Features

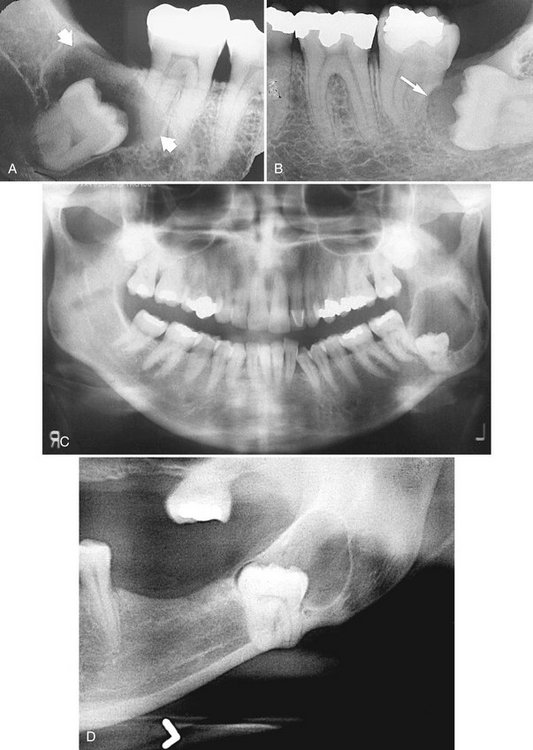

Location.: The most common location of KOT is the posterior body of the mandible (90% occur posterior to the canines) and ramus (more than 50%) (Fig. 21-13). The epicenter is located superior to the inferior alveolar nerve canal. This type of cyst occasionally has the same pericoronal position as, and is indistinguishable from, a dentigerous cyst (Fig. 21-13, B).

FIG. 21-13 In panoramic image A a large keratocystic odontogenic tumor occupies the ramus and body of the mandible; note the septa (black arrow), inferiorly displaced mandibular canal (white arrow), and the root resorption. The keratocyst in B has a pericoronal position relative to the impacted third molar and the distal margin has a scalloped shape.

Periphery and Shape.: As with cysts, KOTs usually show evidence of a cortical border unless they have become secondarily infected. The cyst may have a smooth round or oval shape identical to that of other cysts, or it may have a scalloped outline (a series of contiguous arcs) (see Figs. 21-13 and 21-15, C).

Internal Structure.: The internal structure is most commonly radiolucent. The presence of internal keratin does not increase the radiopacity. In some cases curved internal septa may be present, giving the lesion a multilocular appearance (see Figs. 21-13 and 21-14, A).

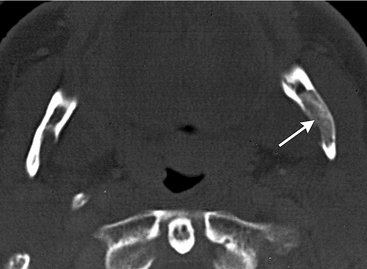

FIG. 21-14 A, Cropped panoramic image of a keratocystic odontogenic tumor occupying the mandibular ramus; note the septa (arrow). B and C, Two axial CT images with bone algorithm of the same case demonstrating very little expansion in the body (B) but significant expansion in the upper ramus in C (arrows).

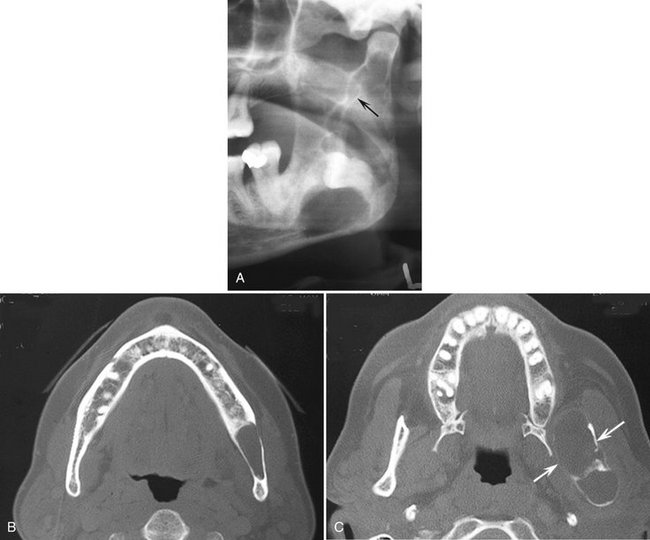

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: An important characteristic of the KOT is its propensity to grow along the internal aspect of the jaws, causing minimal expansion (Fig. 21-15). This occurs throughout the mandible except for the upper ramus and coronoid process, where considerable expansion may occur (Fig. 21-14, C). Occasionally the expansion of large lesions may exceed the ability of the periosteum to form new bone, thus allowing the cystic wall to contact soft tissue peripheral to the outer cortex of the mandible (Fig. 21-16). The relatively slight expansion common with these lesions probably contributes to their late detection, which occasionally allows them to reach a large size. KOTs can displace and resorb teeth but to a slightly lesser degree than dentigerous cysts. The inferior alveolar nerve canal may be displaced inferiorly. In the maxilla this cyst can invaginate and occupy the entire maxillary antrum.

FIG. 21-15 A large keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KOT) occupying most of the right body and ramus of the mandible. A, Despite the large size, the buccal and lingual cortical plates of the mandible have been expanded only slightly, as can be seen in the occlusal film (B). C, A KOT within the body of the mandible; note the lack of expansion and the cyst scalloping between the roots of the teeth.

FIG. 21-16 A, This cropped panoramic image reveals a large keratocystic odontogenic tumor occupying most of the ramus; note the scalloping margin (arrows). B, This axial CT with soft tissue window of the same case showing perforation of the medial cortex and contacting the medial pterygoid muscle (arrow).

Differential Diagnosis

When in a pericoronal position, a KOT may be indistinguishable from a dentigerous cyst. The lesion is likely to be a KOT if the cystic outline is connected to the tooth at a point apical to the cementoenamel junction or if no expansion of the cortical plates has occurred. Also, although KOTs can develop occlusal to developing teeth, often the follicle of the involved tooth is not enlarged as in dentigerous cysts. The typical scalloped margin and multilocular appearance of the KOT may resemble an ameloblastoma, but the latter has a greater propensity to expand. A KOT may show some similarity to an odontogenic myxoma, especially in the characteristics of mild expansion and multilocular appearance. A simple bone cyst often has a scalloped margin and minimal bone expansion, as with the KOT; however, the margins of a simple bone cyst usually are more delicate and often difficult to detect. If several KOTs are found (which occurs in 4% to 5% of cases), these tumors may constitute part of a basal cell nevus syndrome.

Management

If a KOT is suspected, referral to a radiologist for a complete radiologic examination is advisable. Because this tumor has a propensity to recur, an accurate determination of the extent and location of any cortical perforations with soft tissue extension is best achieved with computed tomography (CT). In the case of multiple cysts and the possibility of basal cell nevus syndrome, a thorough radiologic examination that includes CT is required. This allows accurate determination of the number of cysts and other osseous characteristics that confirm the diagnosis.

Surgical treatment may vary and can include resection, curettage, or marsupialization to reduce the size of large lesions before surgical excision. More attention usually is devoted to complete removal of the cystic walls to reduce the chance of recurrence. After surgical treatment, it is important to make periodic posttreatment clinical and radiographic examinations to detect any recurrence. Recurrent lesions usually develop within the first 5 years but may be delayed as long as 10 years.

Definition

The term basal cell nevus syndrome comprises a number of abnormalities such as multiple nevoid basal cell carcinomas of the skin, skeletal abnormalities, central nervous system abnormalities, eye abnormalities, and multiple KOTs. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with variable expressivity.

Clinical Features

Basal cell nevus syndrome starts to appear early in life, usually after 5 years of age and before 30 years of age, with the development of KOTs within the jaws and skin basal cell carcinomas. Typically there are multiple KOTs, usually appearing in multiple quadrants and earlier in life than solitary KOTs do. The recurrence rate of KOTs in this syndrome appears to be higher than with the solitary variety. A thorough radiologic examination including CT imaging is required to detect all the jaw lesions. The skin lesions are small, flattened, flesh-colored or brown papules that can occur anywhere on the body but are especially prominent on the face, neck, and trunk. Occasionally the basal cell carcinomas will form later in life than the jaw lesions or not at all. Skeletal anomalies include bifid rib (most common) and other costal abnormalities such as agenesis, deformity, and synostosis of the ribs, kyphoscoliosis, vertebral fusion, polydactyly, shortening of the metacarpals, temporal and temporoparietal bossing, minor hypertelorism, and mild prognathism. Calcification of the falx cerebri and other parts of the dura occur early in life.

Radiographic Features

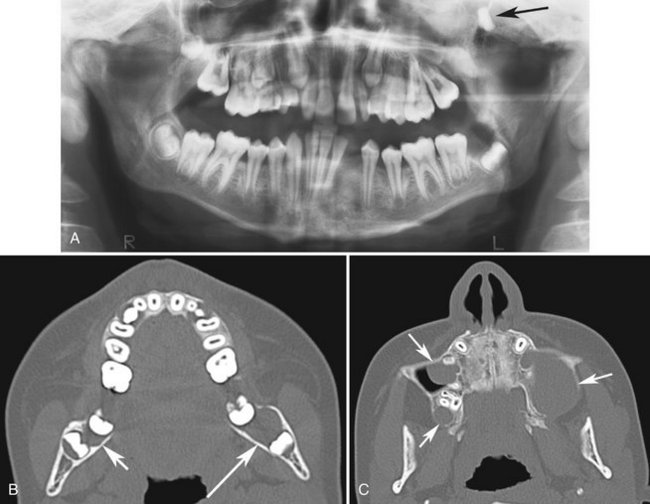

Location.: The location is the same as that of solitary KOTs, as described previously. The multiple KOTs may develop bilaterally and can vary in size from 1 mm to several centimeters in diameter (Fig. 21-17).

FIG. 21-17 A, Panoramic image of a case of basal cell nevus syndrome; note the small Keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KOT) related to the unerupted left mandibular third molar and a large KOT within the left maxilla that has displaced the left maxillary third molar (arrow). B, Axial CT of the same case; note the small mandibular KOT (long arrow) seen in the panoramic image and another small KOT (short arrow) in the right mandible not seen in the panoramic film. C, Another axial CT from the same case revealing the large KOT in the left maxilla and two other KOTs not readily apparent in the panoramic image.

Differential Diagnosis

The presence of a cortical boundary and other cystic characteristics differentiate basal cell nevus syndrome from other abnormalities characterized by multiple radiolucencies (e.g., multiple myeloma). Cherubism appears as bilateral multilocular lesions but usually has significant jaw expansion, which is not characteristic of basal cell nevus syndrome. Also, cherubism pushes posterior teeth in an anterior direction, a distinctive characteristic. Occasionally patients with multiple dentigerous cysts may show some similarities, but dentigerous cysts are more expansile.

Management

The KOTs are treated more aggressively than other solitary KOTs because there appears to be an even greater propensity for recurrence. It is reasonable to examine the patient yearly for new and recurrent cysts. A panoramic film may not be an adequate screening film (see Fig. 21-17) and therefore CT is the modality of preference. Referral for genetic counseling may be appropriate.

Definition

Lateral periodontal cysts are thought to arise from epithelial rests in periodontium lateral to the tooth root. This condition usually is unicystic, but it may appear as a cluster of small cysts, a condition referred to as botryoid odontogenic cysts. It has been postulated that the lateral periodontal cyst is the intrabony counterpart of the gingival cyst in the adult.

Clinical Features

The lesions usually are asymptomatic and less than 1 cm in diameter. The disorder has no apparent sexual predilection, and the age distribution extends from the second to the ninth decades (the mean age is about 50 years). If these cysts become secondarily infected, they will mimic a lateral periodontal abscess.

Radiographic Features

Location.: A total of 50% to 75% of lateral periodontal cysts develop in the mandible, mostly in a region extending from the lateral incisor to the second premolar (Fig. 21-18). Occasionally these cysts appear in the maxilla, especially between the lateral incisor and the cuspid.

Periphery and Shape.: A lateral periodontal cyst appears as a well-defined radiolucency with a prominent cortical boundary and a round or oval shape. Rare large cysts have a more irregular shape.

Differential Diagnosis

Because the location and radiographic appearance of a lateral periodontal cyst are similar in other conditions, the following lesions should be included in the differential diagnosis: a small KOT, mental foramen, small neurofibroma, or a radicular cyst at the foramen of a lateral (accessory) pulp canal. The multiple (botryoid) cysts with a multilocular appearance may resemble a small ameloblastoma.

Management

Lateral periodontal cysts usually do not require sophisticated imaging because of their small size. Excisional biopsy or simple enucleation is the treatment of choice because these cysts do not tend to recur.

Definition

The glandular odontogenic cyst is a rare cyst derived from odontogenic epithelium with a spectrum of characteristics including salivary gland features such as mucus-producing cells. Some authors hypothesize a relationship to a central mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Clinical Features

There is a slight female predominance with a mean age ranging from 46 to 50 years. This cyst has an aggressive behavior and a tendency to recur after surgery.

Radiographic Features

Location.: This cyst occurs more commonly in the mandible and most often in the anterior mandible and in the maxilla, commonly the globulomaxillary region.

Internal Structure.: This cyst has been reported in both unilocular and multilocular appearances (Fig. 21-19).

Differential Diagnosis

This cyst can appear identical to an ameloblastoma and in some cases may be similar to a KOT. It is interesting to note that similar multilocular appearances have been associated with central mucoepidermoid carcinomas.

Treatment

Because of the high rate of recurrence with conservative treatments such as enucleation, more aggressive treatment including resection may be considered. Treated cases should be followed with periodic radiographic examinations to assess for recurrence.

Definition

The World Health Organization now categorizes this entity as a tumor. calcifying cystic odontogenic tumors (CCOTs) are uncommon, slow-growing, benign lesions. They occupy a spectrum ranging from a cyst to an odontogenic tumor, with characteristics of a cyst alone or sometimes those of a solid neoplasm (epithelial proliferation and a tendency to continue growing). This lesion may manufacture calcified tissue identified as dysplastic dentin, and in some instances the lesion is associated with an odontoma. This lesion also sometimes contains a more solid component that gives it an appearance resembling an ameloblastoma, although it does not behave like one.

Clinical Features

CCOTs have a wide age distribution that peaks at 10 to 19 years of age, with a mean age of 36 years. A second incidence peak occurs during the seventh decade. Clinically, the lesion usually appears as a slow-growing, painless swelling of the jaw. Occasionally the patient complains of pain. In some cases the expanding lesion may destroy the cortical plate, and the cystic mass may become palpable as it extends into the soft tissue. The patient may report a discharge from such advanced lesions. Aspiration often yields a viscous, granular, yellow fluid.

Radiographic Features

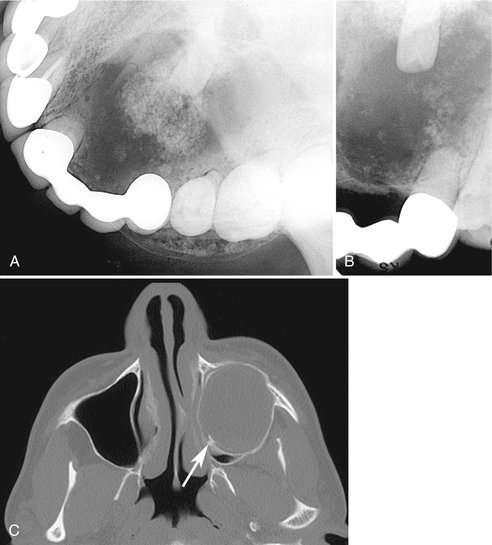

Location.: At least 75% of CCOTs occur in bone, with a nearly equal distribution between the jaws. Most (75%) occur anterior to the first molar, especially associated with cuspids and incisors, where the cyst sometimes manifests as a pericoronal radiolucency.

Periphery and Shape.: The periphery can vary from well defined and corticated with a curved, cystlike shape to ill defined and irregular.

Internal Structure.: The internal aspect can vary in appearance. It may be completely radiolucent; it may show evidence of small foci of calcified material that appear as white flecks or small smooth pebbles; or it may show even larger, solid, amorphous masses (Fig. 21-20). In rare cases the lesion may appear multilocular.

FIG. 21-20 A and B, calcifying cystic odontogenic tumor (CCOT) related to the lateral incisor. Note the well-defined corticated border, internal calcifications, and resorption of part of the root of the central incisor. C, Axial CT image of a large CCOT invaginating into the maxillary sinus; note the small calcifications along the posterior border (arrow).

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: Occasionally (20% to 50% of cases) this tumor is associated with a tooth (most commonly a cuspid) and impedes its eruption. Displacement of teeth and resorption of roots may occur. Perforation of the cortical plate may be seen radiographically with enlarging lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

When no internal calcifications are evident and this lesion has a pericoronal position, it may be indistinguishable from a dentigerous cyst. Other lesions that have internal calcifications to be considered include an adenomatoid odontogenic tumor, ameloblastic fibro-odontoma, and calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor. The common location for the CCOT is not common for either the fibro-odontoma or the calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor. Finally, long-standing cysts may have dystrophic calcification, giving a similar appearance.

Nonodontogenic Cysts

Synonyms

Nasopalatine canal cyst, incisive canal cyst, nasopalatine cyst, median palatine cyst, and median anterior maxillary cyst

Definition

The nasopalatine canal usually contains remnants of the nasopalatine duct, a primitive organ of smell, and the nasopalatine vessels and nerves. Occasionally a cyst forms in the nasopalatine canal when these embryonic epithelial remnants of the nasopalatine duct undergo proliferation and cystic degeneration.

Clinical Features

Nasopalatine duct cysts account for about 10% of jaw cysts. The age distribution is broad, with most cases being discovered in the fourth through sixth decades. The incidence is three times higher in males. Most of these cysts are asymptomatic or cause such minor symptoms that they are tolerated for long periods. The most frequent complaint is a small, well-defined swelling just posterior to the palatine papilla. This swelling usually is fluctuant and blue if the cyst is near the surface. The deeper nasopalatine duct cyst is covered by normal-appearing mucosa unless it is ulcerated from masticatory trauma. If the cyst expands, it may penetrate the labial plate and produce a swelling below the maxillary labial frenum or to one side. The lesion also may bulge into the nasal cavity and distort the nasal septum. Pressure from the cyst on the adjacent nasopalatine nerves that occupy the same canal may cause a burning sensation or numbness over the palatal mucosa. In some cases cystic fluid may drain into the oral cavity through a sinus tract or a remnant of the nasopalatine duct. The patient usually detects the fluid and reports a salty taste.

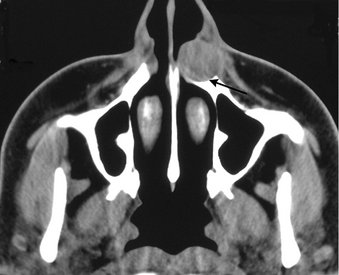

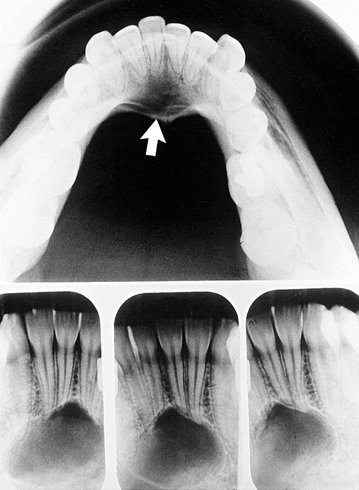

Radiographic Features

Location.: Most nasopalatine duct cysts are found in the nasopalatine foramen or canal. However, if this cyst extends posteriorly to involve the hard palate (Fig. 21-21), it often is referred to as a median palatal cyst (Fig. 21-22). If it expands anteriorly between the central incisors, destroying or expanding the labial plate of bone and causing the teeth to diverge, it sometimes is referred to as a median anterior maxillary cyst. This cyst may not always be positioned symmetrically.

Periphery and Shape.: The periphery usually is well defined and corticated and is circular or oval in shape. The shadow of the nasal spine sometimes is superimposed on the cyst, giving it a heart shape.

Internal Structure.: Most nasopalatine duct cysts are totally radiolucent. Some rare cysts may have internal dystrophic calcifications, which may appear as ill-defined, amorphous, scattered radiopacities.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: Most commonly this cyst causes the roots of the central incisors to diverge, and occasionally root resorption occurs. Seen from a lateral perspective, the cyst may expand the labial cortex and the palatal cortex (Fig. 21-23). The floor of the nasal fossa may be displaced in a superior direction.

Differential Diagnosis

The most common differential diagnosis is a large incisive foramen. A foramen larger than 6 mm may simulate the appearance of a cyst. However, a clinical examination should reveal the expansion characteristic of a cyst and other changes that occur with a space-occupying lesion, such as displacement of teeth. A lateral view of the anterior maxilla, with an occlusal film held outside the mouth and against the cheek, also can help in making the differential diagnosis, as can a cross-sectional (standard) occlusal view. If doubt still exists, comparison with previous images may be useful, or aspiration may be attempted, or another image may be made in 6 months to 1 year to assess any change in size. A radicular cyst or granuloma associated with a central incisor is similar in appearance to an asymmetric nasopalatine cyst. The presence or absence of the lamina dura and enlargement of the periodontal ligament space around the apex of the central incisor indicate an inflammatory lesion. A vitality test of the central incisor may be useful. A second periapical view taken at a different horizontal angulation should show an altered position of the image of a nasopalatine duct cyst, whereas a radicular cyst should remain centered about the apex of the central incisor.

Management

The appropriate treatment for a nasopalatine cyst is enucleation, preferably from the palate to avoid the nasopalatine nerve. If the cyst is large and the danger exists of devitalizing the tooth or creating a naso-oral or antro-oral fistula, the surgeon may elect to marsupialize the cyst.

Definition

The exact origin of nasolabial cysts is unknown. They may be fissural cysts arising from the epithelial rests in fusion lines of the globular, lateral nasal, and maxillary processes. Alternatively, the source of the epithelium may be from the embryonic nasolacrimal duct, which initially lies on the bone surface.

Clinical Features

When this rare lesion is small, it may produce a very subtle, unilateral swelling of the nasolabial fold and may elicit pain or discomfort. When large, it may bulge into the floor of the nasal cavity, causing some obstruction, flaring of the alae, distortion of the nostrils, and fullness of the upper lip. If infected, it may drain into the nasal cavity. It usually is unilateral, but bilateral lesions have occurred. The age of detection ranges from 12 to 75 years, with a mean age of 44 years. About 75% of these lesions occur in females.

Radiographic Features

Location.: Nasolabial cysts are primarily soft tissue lesions located adjacent to the alveolar process above the apices of the incisors. Because this is a soft tissue lesion, plain radiographs may not show any detectable changes. The investigation could include either CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), both of which can provide an image of soft tissues (Fig. 21-24).

Periphery and Shape.: Thin axial CT images with use of the soft tissue algorithm with contrast reveal a circular or oval lesion with slight soft tissue enhancement of the periphery.

Internal Structure.: In CT images with the soft tissue algorithm the internal aspect appears homogeneous and relatively radiolucent compared with the surrounding soft tissues.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: Occasionally a cyst causes erosion of the underlying bone (Fig. 21-25), producing an increased radiolucency of the alveolar process beneath the cyst and apical to the incisors. Also, the usual outline of the inferior border of the nasal fossa may become distorted, resulting in a posterior bowing of this margin.

Differential Diagnosis

The swelling caused by an infected nasolabial cyst may simulate an acute dentoalveolar abscess. It is important to establish the vitality of the adjacent teeth. This cyst may also resemble a nasal furuncle if it pushes upward into the floor of the nasal cavity. A large mucous extravasation cyst or a cystic salivary adenoma should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of an uninfected nasolabial cyst.

Management

The nasolabial cyst should be excised through an intraoral approach. These cysts do not tend to recur.

Definition

Dermoid cysts are a cystic form of a teratoma thought to be derived from trapped embryonic cells that are totipotential. The resulting cysts are lined with epidermis and cutaneous appendages and filled with keratin or sebaceous material (and in rare cases with bone, teeth, muscle, or hair, in which case they are properly called teratomas).

Clinical Features

Dermoid cysts may develop in the soft tissues at any time from birth, but they usually become clinically apparent between 12 and 25 years of age, about equally distributed between the sexes. The swelling, which is slow and painless, can grow to several centimeters in diameter, and when located in the neck or tongue, it may interfere with breathing, speaking, and eating. Depending on how deep the cyst is positioned in the neck, it can deform the submental area. On palpation these cysts may be fluctuant or doughy, according to their contents. Because they usually are in the midline, they do not affect the teeth.

Radiographic Features

Because dermoid cysts are soft tissue cysts, diagnostic imaging is best accomplished by CT or MRI.

Location.: A dermoid cyst is a rare developmental anomaly that may occur anywhere in the body. About 10% or fewer arise in the head and neck, and only 1% to 2% develop in the oral cavity. Of these, about 25% occur in the floor of the mouth and on the tongue. They may be midline or lateral in location.

Periphery and Shape.: The periphery of the lesion usually is well defined by more radiopaque soft tissue of this cyst compared with surrounding soft tissue, as seen in CT scans.

Internal Structure.: Dermoid cysts seldom have any internal mineralized structures when they occur in the oral cavity; therefore they are radiolucent on conventional radiographs. However, a CT scan of the area may reveal a soft tissue multilocular appearance (Fig. 21-26). If teeth or bone form in the cyst, their radiopaque images, with characteristic shapes and densities, are apparent on the radiograph.

Differential Diagnosis

Lesions that are clinically similar to dermoid cysts are ranula (unilateral or bilateral blockage of Wharton’s ducts), thyroglossal duct cysts, cystic hygromas, branchial cleft cysts, cellulitis, tumors (lipoma and liposarcoma), and normal fat masses in the submental area.

Management

Dermoid cysts do not recur after surgical removal.

With time it has become clear that some names used to describe distinct entities are no longer valid. These names include primordial cysts (now recognized largely to be KOTs), median palatal cysts (now recognized as a variant of the nasopalatine duct cyst), and median mandibular and globulomaxillary cysts (because the entrapment of epithelium theory is no longer accepted). Globulomaxillary cysts are now recognized to be radicular or lateral periodontal cysts or KOTs.

Cystlike Lesions

Simple bone cysts (SBCs) are included in this chapter because of their historic classification and because the characteristics and behavior seen in diagnostic imaging are cystic in nature. However, it is important to remember that these lesions are not true cysts.

Synonyms

Traumatic bone cyst, hemorrhagic bone cyst, extravasation cyst, progressive bone cavity, solitary bone cyst, and unicameral bone cyst

Definition

An SBC is a cavity within bone that is lined with connective tissue. It may be empty, or it may contain fluid. However, because it has no epithelial lining, it is not a true cyst. The etiology of SBCs is unknown, although they may be a localized aberration in normal bone remodeling or metabolism. This theory is supported indirectly by the fact that these bony cavities often occur inside lesions of cemento-osseous dysplasia and fibrous dysplasia. No evidence exists to support a traumatic cause.

Clinical Features

SBCs are very common lesions. Most occur in the first two decades of life, with a mean age of 17 years. The lesion shows a male predominance of approximately 2 : 1. Multiple SBCs can develop, especially when the disorder occurs with cemento-osseous dysplasia. The occurrence of SBCs in cemento-osseous dysplasia is seen in an older population, with a mean age of 42 years, and with a female predominance of 4 : 1. SBCs are asymptomatic in most cases, but occasionally pain or tenderness may be present, especially if the cyst has become secondarily infected. Expansion of the mandible or tooth movement is possible but unusual. The teeth in the affected region usually are vital. Most SBCs are discovered only by chance, during radiographic examinations, and for this reason they can become quite large. There is no significant incidence of pathologic fractures. Aspiration usually produces only a few milliliters of straw-colored or serosanguineous fluid.

Radiographic Features

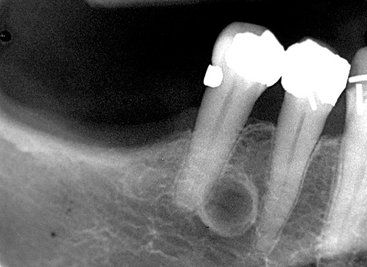

Location.: Almost all SBCs are found in the mandible (Fig. 21-27); in rare cases they develop in the maxilla. The lesion can occur anywhere in the mandible but is seen most often in the ramus and posterior mandible in older patients. SBCs also frequently occur with cemento-osseous and fibrous dysplasia.

FIG. 21-27 A panoramic film demonstrating an SBC (A), an occlusal film (B), and a periapical film (C). The occlusal film shows that no expansion has occurred in the buccal or lingual cortical plates. Except for the superior border, the borders are ill defined and the lesion has scalloped around the teeth and thinned the inferior border of the mandible, but the lamina dura is still present.

Periphery and Shape.: The margin may vary from a well-defined, delicate cortex to an ill-defined border that blends into the surrounding bone. The boundary usually is better defined in the alveolar process around the teeth than in the inferior aspect of the body of the mandible. The shape most often is smooth and curved, like a cyst, with an oval or scalloped border. The lesion often scallops between the roots of the teeth (see Fig. 21-27).

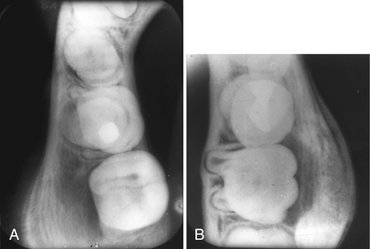

Internal Structure.: The internal structure is totally radiolucent, but occasionally it may appear multilocular, although the lesion does not contain true septa. This appearance is the result of pronounced scalloping of the endosteal surface of either the buccal or lingual plates (Fig. 21-28). The ridges of bone produced by the scalloping give the appearance of septa on a lateral view of the mandible.

FIG. 21-28 A, A simple bone cyst has a multilocular appearance in this lateral oblique view of the mandible. B, The periapical view appears to show internal septa (arrows) because of the scalloping of the endosteal surface of the cortical plates, as seen in the inferior cortex (arrows) in A and of the endosteal surface of the buccal cortex in the occlusal view (C).

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: In most cases these lesions have no effect on the surrounding teeth, although rare cases of tooth displacement and resorption have been documented. Often the lesion involves all the bone around the roots of the teeth but leaves the lamina dura intact or only partly disrupted (Fig. 21-29). Similarly, the sparing of the cortical boundary of the crypt around a developing tooth is characteristic. As previously mentioned, these lesions have a propensity to scallop the endosteal surface of the outer cortex of the mandible. SBCs also have a tendency to grow along the long axis of the bone, causing minimal expansion (Fig. 21-30). However, expansion of the involved bone can occur and is more common with larger lesions (Fig. 21-31).

FIG. 21-29 A simple bone cyst in which the lamina dura is maintained on most root surfaces involved with the lesion except for the mesial surface of the distal root tip of the first molar.

FIG. 21-30 A and B, A simple bone cyst extending from the first bicuspid posteriorly to the base of the ramus and occupying most of the mandible. Considering the extent of the lesion, very little expansion of the buccal or lingual cortical plates has occurred, as can be seen in the axial CT image (B) with bone algorithm.

FIG. 21-31 A simple bone cyst (arrow) positioned in the anterior of the mandible. Note that the superior aspect of the peripheral cortex is better defined than the inferior border and that evidence exists of some expansion of the mandible’s lingual cortex, which in part may due to muscle attachment at the genial tubercles.

Differential Diagnosis

An SBC may have an appearance similar to that of a true cyst, especially a KOT. This is because KOTs tend to grow along bone with very little expansion and often have scalloped borders similar to those of an SBC. However, KOTs usually have a more definite cortical boundary, resorb and displace teeth, and occur in an older age group. Because the SBC may remove bone around teeth without affecting the teeth, there may be a tendency to include a malignant lesion in the differential diagnosis. However, maintenance of some lamina dura and the lack of an invasive periphery and bone destruction should be enough to remove this category of diseases from consideration.

The diagnosis relies primarily on radiographic and surgical observations because the histopathologic aspects are not characteristic. These lesions occasionally heal spontaneously. A biopsy and analysis of a healing cyst may falsely indicate the presence of an ossifying fibroma or fibrous dysplasia because of the formation of new immature bone (Fig. 21-32).

Management

The customary treatment is a conservative opening into the lesion and careful curettage of the lining; this usually initiates bleeding and subsequent healing. Spontaneous healing has been reported. Periodic follow-up radiographic examinations are advisable, especially if the patient declines treatment. These lesions can recur but it is rare.

Shear, M. Cysts of the jaws: recent advances. J Oral Pathol. 1985;14:43–59.

Shear, M. Developmental odontogenic cysts: an update. J Oral Pathol Med. 1994;23:1–11.

Stockdale, CR, Chandler, NP. The nature of the periapical lesion: a review of 1108 cases. J Dent. 1988;16:123–129.

Syrjänen, S, Tammisalo, E, Lilja, R, et al. Radiological interpretation of the periapical cysts and granulomas. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1982;11:89–92.

Toller, PA. Origin and growth of cysts of the jaws. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1967;40:306–336.

Wood, RE, Nortjé, CJ, Padayachee, A, et al. Radicular cysts of primary teeth mimicking premolar dentigerous cysts: report of three cases. ASDC J Dent Child. 1988;55:288–290.

High, AS, Hirschmann, PN. Age changes in residual cysts. J Oral Pathol. 1986;15:524–528.

Schwimmer, AM, Aydin, F, Morrison, SN. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in residual odontogenic cyst: report of a case and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:218–221.

Daley, TD, Wysocki, GP. The small dentigerous cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:77–81.

Lustmann, J, Bodner, L. Dentigerous cysts associated with supernumerary teeth. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;17:100–102.

Main, DM. Follicular cysts of mandibular third molar teeth: radiological evaluation of enlargement. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1989;18:156–159.

Maxymiw, WG, Wood, RE. Carcinoma arising in a dentigerous cyst: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:639–643.

Bohay, RN, Weinberg, S. The paradental cyst of the mandibular permanent first molar: report of a bilateral case. J Dent Child. 1992;59:361–365.

Packota, GV, Hall, JM, Lanigan, DT, et al. Paradental cysts on mandibular first molars in children: report of five cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1990;19:126–132.

Shear, M. Cysts of the oral regions. Bristol, UK: John Wright & Sons; 1976.

Stoneman, DW, Worth, HM. The mandibular infected buccal cyst-molar area. Dent Radiogr Photogr. 1983;56:1–14.

Philipsen, HP, Reichert, PA, Ogawa, I, et al. The inflammatory paradental cyst: a critical review of 342 from a literature survey, including 17 new cases from the author’s files. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:147–155.

Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor

Barnes, L. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics: head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005.

Brannon, RB. The odontogenic keratocyst: a clinicopathological study of 312 cases, I: clinical features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;42:54–72.

Kakarantza-Angelopoulou, E, Nicolatou, O. Odontogenic keratocysts: clinicopathologic study of 87 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:593–599.

Myoung, H, Hong, SP, Hong, SD, et al. Odontogenic keratocyst: review of 256 cases for recurrence and clinicopathologic parameters. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:328–333.

Shear, M. The aggressive nature of the odontogenic keratocyst: is it a benign cystic neoplasm, II: proliferation and genetic studies. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:323–331.

Angelopoulou, E, Angelopoulos, AP. Lateral periodontal cyst: review of the literature and report of a case. J Periodontol. 1990;61:126–131.

Donatsky, O, Hjörting-Hansen, E, Philipsen, HP, et al. Clinical, radiographic, and histologic features of the basal cell nevus syndrome. Int J Oral Surg. 1976;5:19–28.

Evans, DC, Farndon, PA, Burnell, LD, et al. The incidence of Gorlin syndrome in 173 consecutive cases of medulloblastoma. Br J Cancer. 1991;64:959–961.

Gorlin, RJ. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Medicine. 1987;66:98–113.

Shear, M, Pindborg, JJ. Microscopic features of the lateral periodontal cyst. Scand J Dent Res. 1975;83:103–110.

Weathers, DR, Waldron, CA. Unusual multilocular cysts of the jaws (botryoid odontogenic cysts). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;36:235–241.

Wysocki, GP, Brannon, RB, Gardner, DG, et al. Histogenesis of the lateral periodontal cyst and the gingival cyst of the adult. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;50:327–334.

Koppang, HS, Johannessen, S, Haugen, LK, et al. Glandular odontogenic cyst: report of two cases and literature review of 45 previously reported cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:455–462.

Noffke, C, Raubenheimer, EJ. The glandular odontogenic cyst: clinical and radiologic features: review of the literature and report of nine cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:333–338.

Calcifying Cystic Odontogenic Tumor

Johnson, A, III., Fletcher, M, Gold, L, et al. Calcifying odontogenic cyst: a clinicopathologic study of 57 cases with immunohistochemical evaluation for cytokeratin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:679–683.

Moleri, AB, Moreira, LC, Carvalho, JJ. Comparative morphology of 7 new cases of calcifying odontogenic cysts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:689–696.

Yoshiura, K, Tabata, O, Miwa, K, et al. Computed tomographic features of calcifiying odontogenic cysts. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1998;27:12–16.

Elliott, KA, Franzese, CB, Pitman, KT. Diagnosis and surgical management of nasopalatine duct cysts. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1336–1340.

Mraiwa, RJ, Jacobs, R, Van Cleynenbreugel, J, et al. The nasopalatine duct cyst revisited using 2D and 3D CT imaging. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004;33:396–402.

Swanson, KS, Kaugars, GE, Gunsolley, JC. Nasopalatine duct cyst: an analysis of 334 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:268–271.

Choi, JH, Cho, JH, Kang, HJ, et al. Nasolabial cysts: a retrospective analysis of 18 cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002;81:94–96.

Yuen, H, Julian, CY, Samuel, CL. Nasolabial cysts: clinical features, diagnosis and treatment. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:293–297.

Damante, JH, Da, S, Guerra, EN, et al. Spontaneous resolution of simple bone cysts. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:182–186.

Kaugars, GE, Cale, AE. Traumatic bone cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:318–324.

Perdigao, AF, Silva, EC, Sakurai, E, et al. Idiopathic bone cavity: a clinical, radiographic and histological study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41:407–409.

Saito, Y, Hoshina, Y, Nagamine, T, et al. Simple bone cyst: a clinical and histopathologic study of fifteen cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:487–491.

Sapp, PJ, Stark, ML. Self-healing traumatic bone cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:597–602.