Paranasal Sinuses

The paranasal sinuses are the four paired sets of air-filled cavities of the craniofacial complex composed of the maxillary, frontal, and sphenoid sinuses and the ethmoid air cells. The maxillary sinuses are of particular importance to the dentist because of their proximity to the teeth and their associated structures. Consequently, abnormalities arising from within the maxillary sinuses can cause symptoms that may mimic diseases of odontogenic origin, and conversely, abnormalities that arise in and around the teeth may affect the sinuses or mimic the symptoms of sinus disease.

Part or all of the paranasal sinuses may appear on radiographs made for dental purposes, including maxillary periapical, occlusal, and panoramic radiographs. All the paranasal sinuses can appear on skull radiographs made for orthodontic or orthognathic surgical purposes (see Chapter 12), although not necessarily in the most diagnostic fashion. Therefore, the dentist should have some familiarity with variations to the normal appearances of the sinuses and the more common diseases that may affect them.

Normal Development and Variations

The paranasal sinuses develop as invaginations from the nasal fossae into their respective bones (maxillary, frontal, sphenoid, and ethmoid). Consequently, the mucosal lining of the paranasal sinuses is similar to that found in the nasal cavity, but with slightly fewer mucus glands. In the absence of disease the epithelial cilia move mucus toward their respective communications with the nasal fossae.

The maxillary sinuses (sometimes called the maxillary antra or antra of Highmore) are the first to develop in the second month of intrauterine life. An invagination develops in the lateral wall of the nasal fossa in the middle meatus, and the sinus enlarges laterally into the body of the maxilla. At birth, each sinus is a thin, small slit no more than 8 mm in length in its anteroposterior dimension. With time, the maxilla becomes progressively more pneumatized as the air cavity expands further into the bone both laterally under the orbits toward the zygomatic bone and inferiorly toward the alveolar process. Consequently, it may be very common to see the inferior or “dependent” portion of the air-filled maxillary sinus and floor near, or superimposed over, the roots of the premolar or molar teeth to some degree.

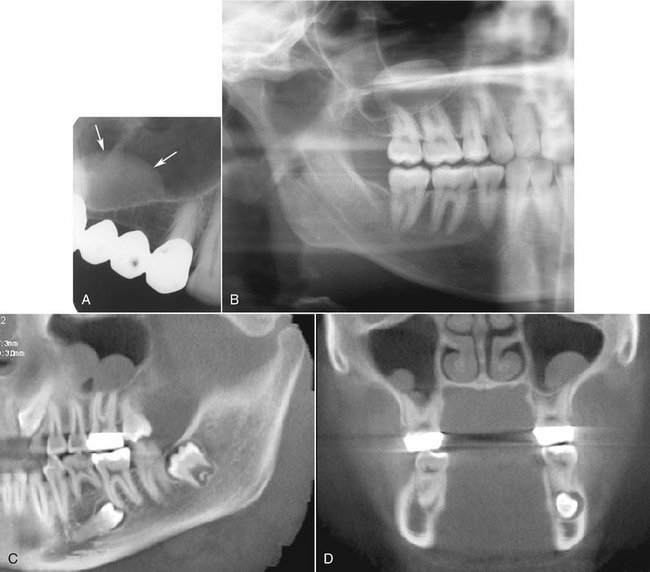

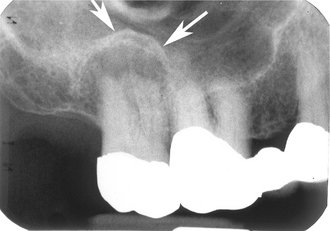

The floor of the maxillary sinus is a thin, radiopaque line on radiographs. Where the alveolar process of the maxilla is not well pneumatized, the floor of the maxillary sinus may not be visible on periapical radiographs (Fig. 27-1, A), or it may be seen superior to the roots of the maxillary premolar and/or molar teeth (Fig. 27-1, B). With greater pneumatization of the alveolar process, the floor of the maxillary sinus may appear to undulate around the roots of the teeth or be superimposed over the roots of the adjacent teeth, giving the appearance that the tooth roots have penetrated the sinus floor (Fig. 27-1, C and D). The very close relationship between the tooth roots and the maxillary sinus is referred to as “draping.” Closer examination of the periapical aspect of the teeth usually reveals intact laminae durae and periodontal ligament spaces around the tooth root apices. In some instances, the appearance of the maxillary sinus may be mistakenly confused with a benign space-occupying lesion (Fig. 27-2).

FIG. 27-1 The range of normal of the position of the maxillary sinus relative to the premolar and molar teeth are shown in periapical images A to D. There is no apparent floor in A, with progressively more pneumatization of the alveolar process in B and C; draping of the maxillary sinus border over the apices of the teeth is particularly evident in D.

FIG. 27-2 A panoramic image of a loculus (arrows) of the left maxillary sinus draping mimicking a benign space-occupying lesion.

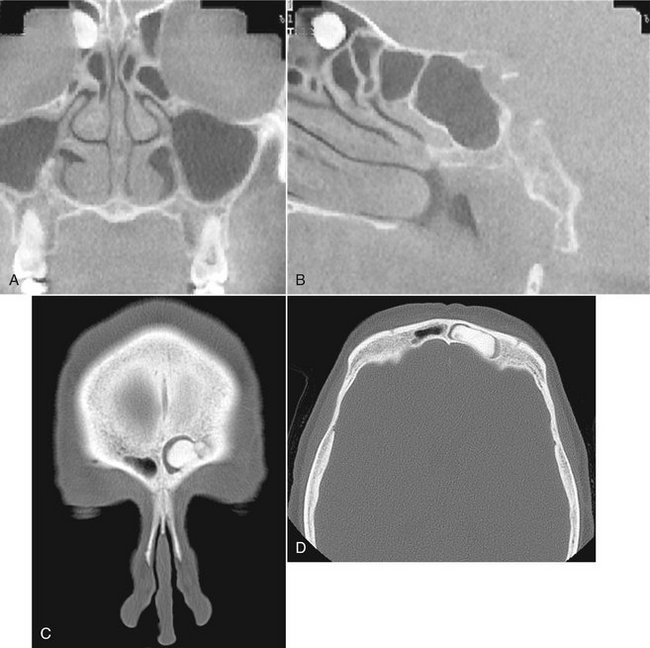

In patients with considerable pneumatization extending into the alveolar process of the maxilla, the lamina dura of a premolar or molar tooth may form a portion of the sinus floor. In addition to the alveolar process, the maxillary pneumatization may extend into the palatal, zygomatic, and frontal processes of the maxilla, which can be appreciated in plain films but are more notable in advanced imaging such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 27-3).

FIG. 27-3 An example of pneumatization of the maxillary sinus into the palatal process of the maxilla (arrow) in this coronal CT image (A) and examples of pneumatization of the zygomatic process of the maxilla in this axial CT image (B); also note the retention pseudocyst in the left maxillary sinus.

Hypoplasia of the maxillary sinuses occurs unilaterally in about 1.7% of patients and bilaterally in 7.2%. In these patients, the radiographic images of the affected sinus may appear more radiopaque than normal because of the relatively large amount of surrounding maxillary bone. The configuration of the maxillary sinus walls frequently helps to distinguish between a hypoplastic sinus and one that is pathologically radiopaque. A Waters view will show an inward bowing of the sinus wall resulting in a smaller than normal air cavity. In contrast, extensive enlargement of the maxillary and other paranasal sinuses is a well-known feature of acromegaly.

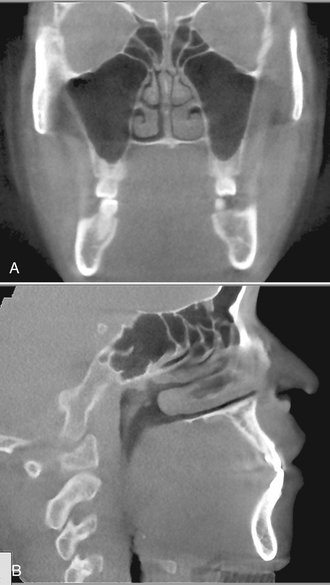

The development of the frontal sinuses does not usually begin until the fifth or sixth year. These sinuses develop either directly as extensions from the nasal fossae or from anterior ethmoid air cells (see Fig. 27-4, B). In about 4% of the population, the frontal sinuses fail to develop. As with the other paranasal sinuses, the right and left frontal sinus cavities develop separately, and as they expand, they approach each other in the midline. In most instances, a thin bony septum may separate the two cavities. In the adult, the frontal sinuses are often asymmetric cavities located above the supraorbital ridges and the nasion; however, in some patients the sinuses may also extend posteriorly over the orbits.

FIG. 27-4 Normal coronal (A) and sagittal (B) cone-beam CT images of the maxillary sinus and ethmoid air cells (A) and the frontal and sphenoid sinuses and ethmoid air cells (B).

The sphenoid sinus begins growth in the fourth fetal month as invaginations from the sphenoethmoidal recesses of the nasal fossae. Located in the body of the sphenoid bone, the right and left sphenoid sinuses are separated by a bony septum and are usually asymmetric in size and shape. The overall size of the sinus is quite variable, and like the maxillary sinuses, the sphenoid sinus may extend beyond the body of the sphenoid bone into the dorsum sella, the clinoid processes, the greater or lesser wings, and the pterygoid processes. The osteum of the sphenoid sinus is a relatively large-diameter opening, which may explain why blockages of the sphenoid sinus osteum are uncommon (see the section on mucoceles later in this chapter).

The ethmoid air cells extend into the ethmoid bones during the fifth fetal month and continue to enlarge until the end of puberty. They consist of multiple interconnected, or sometimes separate, small air-filled chambers that border the medial aspects of the orbital cavities (Fig. 27-4, A and B). The number of air cells varies considerably, with each ethmoid bone containing between 8 and 15 cells. In some cases, the ethmoid air cells may extend into the neighboring maxillary, lacrimal, frontal, sphenoid, and palatine bones.

The function of the paranasal sinuses is controversial. Some of the putative roles that have been ascribed to the sinuses include heating and humidification of inhaled air, helping to reduce cranial weight, and insulation or protection of deeper vital structures. Indeed, the paranasal sinuses may also have no function whatsoever and may be evolutionarily unwanted space.

Diseases Associated with the Paranasal Sinuses

Because the maxillary sinus is of most concern to the dentist, the following text emphasizes diseases related to the maxillary sinus.

DEFINITION

Diseases associated with the maxillary sinuses include both intrinsic diseases (originating primarily from tissues within the sinus) and those that originate outside the sinus (most commonly diseases arising from odontogenic tissues) that either impinge on or infiltrate the sinus. These types of diseases include inflammatory odontogenic disease, odontogenic cysts, benign and malignant odontogenic neoplasms, bone dysplasias, and trauma.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The clinical signs and symptoms of maxillary sinus disease include a feeling of pressure, altered voice characteristics, pain on head movement, percussion sensitivity of the teeth or cheek region, regional dysesthesia, paresthesia or anesthesia, and swelling of the facial structures adjacent to the maxilla.

When the clinical signs indicate that maxillary sinus disease may be related to the alveolar process of the maxilla or teeth, it is reasonable for the dentist to proceed with the initial radiologic investigation. If there are positive findings, the patient should be referred to an oral and maxillofacial radiologist to complete the examination. The application of specific imaging modalities is reviewed in the following section.

APPLIED DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

A periapical radiograph provides a detailed, albeit limited, view of the alveolar recess and floor of the maxillary antrum. If during this examination the dentist suspects an abnormality, a maxillary lateral occlusal projection may be used for a more extensive view of the antrum. The panoramic radiograph depicts both maxillary sinuses, revealing greater internal structure and parts of the inferior, posterior, and anteromedial walls. It is difficult to compare the internal radiopacities of the right and left sinus in the panoramic image because of variations that result from overlapping phantom images of other structures.

Specialized skull views are the next step in the investigation. The standard series of plane radiographic views of the sinuses includes the Waters (occipitomental), lateral, submentovertex, and Caldwell (15-degree posteroanterior) skull views. The Waters projection is optimal for visualization of the maxillary sinuses, especially to compare internal radiopacities, and the frontal sinuses and ethmoid air cells. If the Waters view is made with the mouth open, parts of the sphenoid sinuses may also be visualized. The submentovertex view may be useful in evaluating the lateral and posterior borders of the maxillary sinuses and the ethmoid air cells. The Caldwell view is most useful in evaluating the frontal sinuses and ethmoid air cells. The lateral skull view allows examination of all four pairs of the paranasal sinuses, but with each member of a pair superimposed on the other.

CT and MRI have become increasingly important for evaluation of sinus disease and have virtually replaced plane radiography and conventional tomography for investigations of the paranasal sinuses. Because CT and MRI provide multiple sections through the sinuses in different planes, they may contribute significantly to delineating the extent of disease and the final diagnosis. High-resolution axial and coronal CT and MRI examinations are the most revealing imaging techniques for the paranasal sinuses and the adjacent structures and areas.

CT examination is appropriate to determine the extent of disease in patients who have chronic or recurrent sinusitis. Indeed, coronal CT provides superior visualization of the ostiomeatal complex (the region of the ostium of the maxillary sinus and the ethmoidal ostium) and nasal cavities and for demonstrating any reaction in the surrounding bone to sinus disease. MRI provides superior visualization of the soft tissues, especially the extension of infiltrating neoplasms into the sinuses or surrounding soft tissues, or the differentiation of retained fluid secretions from soft tissue masses in the sinuses.

Intrinsic Diseases of the Paranasal Sinuses

The following are abnormalities that originate from tissues within the sinuses.

INFLAMMATORY DISEASE

Inflammation may result from a variety of causes such as infection, chemical irritation, allergy, introduction of a foreign body, or facial trauma. The radiographic changes associated with inflammation include thickened sinus mucosa, air-fluid levels in the sinuses, polyps, empyema, and retention pseudocysts. Viral infections may, however, not cause any radiographic change in a sinus.

Definition

The mucosal lining of the paranasal sinuses is composed of respiratory epithelium and is normally about 1 mm thick. Normal sinus mucosa is not visualized on radiographs; however, when the mucosa becomes inflamed from either an infectious or allergic process, it may increase in thickness 10 to 15 times, which may be seen radiographically. This inflammatory change is referred to as mucositis.

Clinical Features

The thickness of sinus mucosa in an asymptomatic individual may vary considerably over a relatively short period of time. Consequently, the discovery of thickened mucosa in an individual who is otherwise asymptomatic does not necessarily imply that further investigations are warranted or that treatment is required. Most of the inflammatory episodes that result in thickening of the mucosal lining of the sinuses are unrecognized by the patient and are discovered only incidentally on a radiograph.

Radiographic Features

The image of thickened mucosa is readily detectable in the radiograph as a noncorticated band noticeably more radiopaque than the air-filled sinus, paralleling the bony wall of the sinus (Fig. 27-5).

Definition

Sinusitis is a condition involving generalized inflammation of the paranasal sinus mucosa caused by an allergen, bacteria, or a virus. Sinusitis may cause blockage of drainage through the ostiomeatal complex. Inflammatory changes may lead to ciliary dysfunction and retention of sinus secretions. Perhaps 10% of inflammatory episodes of the maxillary sinuses are extensions of dental infections. The term pansinusitis describes sinusitis affecting all the paranasal sinuses. In children with pansinusitis, the possibility of cystic fibrosis should be considered.

Clinical Features

Acute maxillary sinusitis is often a complication of the common cold, which is accompanied by a clear nasal discharge or pharyngeal drainage. After a few days, the stuffiness and nasal discharge increase, and the patient may complain of pain and tenderness to pressure or swelling over the involved sinus. The pain may also be referred to the premolar and molar teeth on the affected side, and these teeth may also be sensitive to percussion, although this is more commonly seen in bacterial sinusitis. Under these conditions, a green or greenish yellow nasal discharge may also be appreciated. This finding requires that the teeth be ruled out as a possible source of the pain or infection. However, the key signs and symptoms are those of sepsis: fever, chills, malaise, and an elevated leukocyte count. Acute sinusitis is the most common of the sinus conditions that cause pain.

Chronic maxillary sinusitis is typically a sequela of an acute infection that fails to resolve by 3 months. In general, no external signs occur, except during periods of acute exacerbations when increased pain and discomfort are apparent. Chronic sinusitis is often associated with anatomic derangements including deviation of the nasal septum and the presence of concha bullosa (pneumatization of the middle concha) that inhibit the outflow of mucus. Chronic sinusitis is also often associated with allergic rhinitis, asthma, cystic fibrosis, and dental infections.

Radiographic Features

Thickening of sinus mucosa and the accumulation of secretions that accompany sinusitis reduce the air content of the sinus and cause it to become increasingly radiopaque. The most common radiopaque patterns that occur in the Waters view are localized mucosal thickening along the sinus floor, generalized thickening of the mucosal lining around the entire wall of the sinus, and near-complete or complete radiopacification of the sinus (Figs. 27-6 and 27-7). Such changes are best seen in the maxillary sinuses, but the frontal and sphenoid sinuses may be similarly affected. Scrutinizing the area around the maxillary ostium on any of the views from Waters projections to CT images may reveal the presence of thickened mucosal tissue, which may cause blockage of the ostium. Mucosal thickening in just the base of the sinus may not represent sinusitis. Rather, it may represent the more localized thickening that can occur in association with rarefying osteitis from a tooth with a nonvital pulp. This may, however, progress to involve the entire sinus.

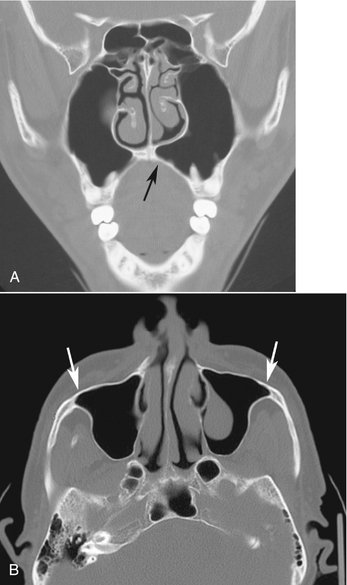

FIG. 27-6 Waters view demonstrating complete radiopacification of the left maxillary and frontal sinuses, and ethmoid air cells. An air-fluid level is visible in the right maxillary sinus (arrows).

FIG. 27-7 Coronal (A) view of the maxillary sinuses showing complete radiopacification of the left sinus and circumferential mucosal thickening of the right sinus, and sagittal (B) CT image of mucositis of the ethmoid air cells.

The image of thickened sinus mucosa on the radiograph may be uniform or polypoid. In the case of an allergic reaction, the mucosa tends to be more lobulated. In contrast, in cases of infection, the thickened mucosal outline tends to be smoother, with its contour following that of the sinus wall. The inability to perceive the delicate walls of the ethmoid air cells is a particularly sensitive sign of ethmoid sinusitis.

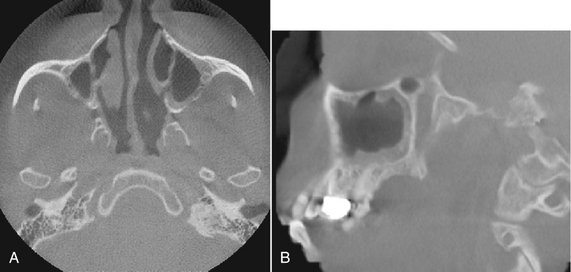

An air-fluid level resulting from the accumulation of secretions may also be present. Because the radiopacities of transudates, exudates, blood, and pathologically altered mucosa are similar, the differentiation among them relies on their shape and distribution. When present, fluid appears radiopaque and occupies the inferior aspect of the sinus. The border between the radiopaque fluid and the relatively radiolucent antrum is horizontal and straight, or with a meniscus (see Fig. 27-6). It is possible to confirm that one is viewing an air-fluid interface by tilting the head and making another radiograph. This changes the orientation of the fluid level, which eliminates any doubt as to its fluid nature. However, when attempting to verify this, sufficient time should be allowed between the first and second exposures for the fluid level to change. If a significant proportion of the fluid is mucous, some minutes may be required before it attains its new level. To demonstrate an air-fluid level, the central ray of the x-ray beam must be horizontal and at the level of the air-fluid interface. Chronic sinusitis may result in persistent radiopacification of the sinus with sclerosis and thickening of the sinus wall (Fig. 27-8). Resorption of the bony border is unusual.

FIG. 27-8 Axial (A) and sagittal (B) cone-beam CT images show peripheral bony thickening of the left maxillary sinus from chronic sinusitis.

The resolution of acute sinusitis becomes apparent on the radiograph as a gradual increase in the radiolucency of the sinus. This can first be recognized when a small clear area appears in the interior of the sinus; the thickened mucous membrane gradually shrinks so that it begins to follow the outline of the bony wall. In time the mucous membrane again becomes radiographically invisible, and the sinus appears normal. In chronic sinusitis the inflammation may stimulate the sinus periosteum to produce bone, resulting in thick sclerotic borders of the maxillary antrum.

Management

The goals of treatment of sinusitis are to control the infection, promote drainage, and relieve pain. Acute sinusitis is usually treated medically with decongestants to reduce mucosal swelling and with antibiotics in the case of a bacterial sinusitis. Chronic sinusitis is primarily a disease of obstruction of the ostia; thus the goal is ventilation and drainage. This is often accomplished through endoscopic surgery to enlarge obstructed ostia or by establishing an alternate path of drainage.

Synonyms

Antral pseudocyst, benign mucous cyst, mucous retention cyst, mucous retention pseudocyst, mesothelial cyst, pseudocyst, interstitial cyst, lymphangiectatic cyst, false cyst, retention cyst of the maxillary sinus, benign cyst of the antrum, benign mucosal cyst of the sinus, serous nonsecretory retention pseudocyst, and mucosal antral cyst

Definition

The term retention pseudocyst is used to describe several related conditions. The actual pathogenesis of these lesions is controversial; however, because their clinical and radiographic features are similar, no attempt is made here to distinguish them. One etiology suggests that blockage of the secretory ducts of seromucous glands in the sinus mucosa may result in a pathologic submucosal accumulation of secretions, resulting in swelling of the tissue. A second theory suggests that the serous nonsecretory retention cyst arises as a result of cystic degeneration within an inflamed, thickened sinus lining. Both types of lesions are called pseudocysts because they are not lined with epithelium.

Clinical Features

Retention pseudocysts may be found in any of the sinuses at any time of the year but occur more often in the early spring or fall. This suggests that they might have to do with changes in seasonal temperatures or with heating or air conditioning in buildings. Most studies have found that the retention pseudocyst is more common in males.

The retention pseudocyst rarely causes any signs or symptoms, and thus the patient is usually unaware of the lesion. It often is noticed as an incidental finding on radiographs made for other purposes. However, when the pseudocyst completely fills the maxillary sinus cavity, it may prolapse (extrude) through the ostium and cause nasal obstruction and postnasal discharge. This may be the only clinical evidence of the presence of the pseudocyst. Because either type of retention pseudocyst may enlarge and fill a sinus cavity, it frequently ruptures as a result of abrupt pressure changes caused by sneezing or blowing of the nose. If this does not happen, the expanding pseudocyst may herniate through the ostium into the nasal cavity, where it subsequently ruptures. The pseudocyst may be present on radiographic examination of the maxillary sinus, perhaps absent only a few days later, only to reappear on subsequent examinations.

The maxillary sinus is the most common site of retention pseudocysts, although they are occasionally found in the frontal or sphenoid sinuses. Antral retention pseudocysts are not related to extractions or associated with periapical disease.

Radiographic Features

Location.: Partial images of retention pseudocysts of the maxillary antrum may appear on maxillary posterior periapical radiographs (Fig. 27-9, A), but they are best demonstrated in extraoral radiographs (Fig. 27-9, B). Although pseudocysts may occur bilaterally, usually only a single pseudocyst develops. Occasionally more than one pseudocyst may form in a single sinus. These pseudocysts usually form on the floor of the sinus (Fig. 27-9, D), although some may form on the lateral walls or the roof (Fig. 27-9, C). Retention pseudocysts may vary in size from that of a fingertip to completely filling the sinus and making it radiopaque.

Periphery and Shape.: Retention pseudocysts usually appear as well-defined, noncorticated, smooth, dome-shaped radiopaque masses. Because the lesion originates within the sinus, no osseous border surrounds it. The base of the lesions may be narrow or more commonly broad.

Internal Structure.: The internal aspect is homogeneous and more radiopaque than the surrounding air of the sinus cavity (see Fig. 27-9, B). The radiopacity of the lesion is caused by the accumulation of fluid and, as such, normal osseous landmarks may often be seen through its image.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: There are no effects on the surrounding structures, and thus it is of note that the sinus floor is intact. When a pseudocyst occurs adjacent to the root of a tooth, the lamina dura surrounding the root is intact and there is a normal width of the periodontal ligament space.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish retention pseudocysts from odontogenic cysts (for example, radicular or dentigerous cysts, or keratocysts), antral polyps, or any rounded neoplastic mass. This can usually be done radiographically and by the patient’s history. Commonly, the floor of the antrum is displaced by the odontogenic cyst, and the border of the cyst becomes coincident with the bony sinus floor. In some instances, periodic fenestrations can be seen through the bony sinus floor or cyst border. The retention pseudocyst is dome shaped but lacks the thin marginal radiopaque line representing the corticated border characteristic of the odontogenic cyst or tumor. The odontogenic cyst is also more rounded or tear drop shaped, and in the case of a radicular cyst, the lamina dura of the involved tooth or teeth is not intact in the apical area.

Antral polyps of infectious or allergic origin may be distinguished radiographically from a retention pseudocyst in that they are more often multiple. They are also commonly associated with a thickened mucous membrane, which is less frequently observed with retention pseudocysts.

Neoplasms may also mimic a retention pseudocyst. If they are benign and originating from outside the sinus, they are separated from the cavity of the sinus by a radiopaque border, similar to the odontogenic cysts. Malignant neoplasms may destroy the osseous border of the sinus, whether they arise from within the sinus or from the alveolar process. The neoplasm is, however, less likely to be as dome shaped as the retention pseudocyst.

Management

Retention pseudocysts in the maxillary sinus usually require no treatment because they customarily resolve spontaneously without any residual effect on the antral mucosa.

Definition

The thickened mucous membrane of a chronically inflamed sinus frequently forms into irregular folds called polyps. Polyposis of the sinus mucosa may develop in an isolated area or in a number of areas throughout the sinus.

Clinical Features

Polyps may cause displacement or destruction of bone. In the ethmoid air cells, polyps may cause destruction of the medial wall of the orbit (lamina papyracea of the ethmoid bone) and a unilateral proptosis.

Radiographic Features

A polyp may be differentiated from a retention pseudocyst on a radiograph by noting that a polyp usually occurs with a thickened mucous membrane lining because the polypoid mass is no more than an accentuation of the mucosal thickening. In the case of a retention pseudocyst, however, the adjacent mucous membrane lining is not usually apparent. If multiple retention pseudocysts are seen within a sinus, the possibility of sinus polyposis should be entertained.

The radiographic image of the bone displacement or destruction associated with polyps may mimic a benign or malignant neoplasm. Because many sinus neoplasms are asymptomatic, examination of a paranasal sinus that reveals bone destruction associated with radiopacification is an indication for biopsy and should not be delayed by initial conservative treatment.

Definition

Antroliths occur within the maxillary sinuses and are the result of deposition of mineral salts such as calcium phosphate, calcium carbonate, and magnesium around a nidus, which may be introduced into the sinus (extrinsic) or could be intrinsic such as masses of stagnant or inspissated mucous or cellular debris in sites of previous inflammation.

Clinical Features

The smaller antroliths are usually asymptomatic and usually are discovered as incidental findings on radiographic examination. If they continue to grow, the patient may have associated sinusitis, blood-stained nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, or facial pain.

Radiographic Features

Location.: Antroliths occur within the maxillary sinus and thus are positioned above the floor of the maxillary antrum in either periapical or panoramic radiographs (Fig. 27-10).

FIG. 27-10 The alternating circular radiopaque and radiolucent pattern of an antrolith is seen on a panoramic image (A) superimposed over the posterior wall of the right maxillary sinus. The coronal multidirectional tomographic image (B) confirms the location of the antrolith within the sinus and, furthermore, shows the antrolith not to be attached to the adjacent sinus wall.

Periphery and Shape.: Antroliths have a well-defined periphery and may have a smooth or irregular shape.

Internal Structure.: The internal aspect may vary in density from a barely perceptible radiopacity to an extremely radiopaque structure. The internal density may be homogenous or heterogeneous, and in some instances alternating layers of radiolucency and radiopacity in the form of laminations may be seen.

Differential Diagnosis

Antroliths may be distinguished from root fragments in the sinus by inspection of the mass for the usual root anatomy such as the presence of a root canal. A displaced root fragment in the sinus may move when radiography is performed with the head in different positions, unless it is lodged between the bone and the sinus lining. Rhinoliths are similar calcifications but are found within the nasal fossae. Posteroanterior and lateral skull views help identify the location of a rhinolith.

Definition

A mucocele is an expanding, destructive lesion that results from a blocked sinus ostium. The blockage may result from intra-antral or intranasal inflammation, polyp, or neoplasm. The entire sinus thus becomes the pathologic cavity. As mucous secretions accumulate and the sinus cavity fills, the increase in intra-antral pressure results in thinning, displacement, and, in some cases, destruction of the sinus walls. When the cavity is filled with pus, it is termed an empyema, pyocele, or mucopyocele.

Clinical Features

A mucocele in the maxillary sinus may exert pressure on the superior alveolar nerves and thus cause radiating pain. The patient may first complain of a sensation of fullness in the cheek, and the area may swell. This swelling may first become apparent over the anteroinferior aspect of the antrum, the area where the wall is thin, or destroyed. If the lesion expands inferiorly, it may cause loosening of the posterior teeth in the area. If the medial wall of the sinus is expanded, the lateral wall of the nasal cavity will deform and the nasal airway may be obstructed. Should it expand into the orbit, it may cause diplopia (double vision) or proptosis (protrusion of the globe of the eye).

Radiographic Features

Location.: About 90% of mucoceles occur in the ethmoid air cells and frontal sinuses and rarely in the maxillary and sphenoid sinuses.

Periphery and Shape.: The normal shape of the sinus is changed into a more circular, “hydraulic” shape as the mucocele enlarges.

Internal Structure.: The internal aspect of the sinus cavity is uniformly radiopaque (Fig. 27-11, A).

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: The shape of the sinus changes as its margins are displaced outward and the bone expands. Septa and the bony walls may be severely thinned. When the mucocele is associated with the maxillary antrum, teeth may be displaced or roots resorbed. In the frontal sinus the usually scalloped border is smoothed by expansion, and the intersinus septum may be displaced (Fig. 27-11, B). The supramedial border of the orbit may be displaced or destroyed. In the ethmoid air cells, displacement of the lamina papyracea may occur, displacing the contents of the orbit. In the sphenoid sinus the expansion may be in a superior direction, suggesting a pituitary neoplasm.

Differential Diagnosis

Although it may not be possible to distinguish between a mucocele in the maxillary antrum and a cyst or neoplasm, any suggestion that the lesion is associated with an occluded ostium should strengthen the likelihood of a mucocele. Blockage of the ostium is usually the result of a previous surgical procedure, although a deviated nasal septum or polyps may be a factor. A large odontogenic cyst displacing the maxillary antral floor may mimic a mucocele. Look for any remnants of the internal aspect of the antrum between the wall of the cyst and the wall of the antrum. CT is the imaging method of choice for making these distinctions.

Neoplasms

Benign neoplasms of the paranasal sinuses other than inflammatory polyps are rare. The radiographic images of such benign neoplasms are nonspecific. Usually the involved portion of the sinus appears radiopaque because of the presence of a mass, and there may be displacement of adjacent sinus borders.

The most common malignant neoplasms of the paranasal sinuses are squamous cell carcinomas and, to a lesser extent, malignant salivary gland neoplasms. Of carcinomas of the paranasal sinuses, 74% originate in the maxillary sinus. Although radiopacification is a feature of both the inflammatory conditions and neoplasms, bone destruction is more common with malignant neoplasms.

BENIGN NEOPLASMS OF THE PARANASAL SINUSES

Definition

The epithelial papilloma is a rare neoplasm of respiratory epithelium that occurs in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. It occurs predominantly in men.

Clinical Features

Unilateral nasal obstruction, nasal discharge, pain, and epistaxis may occur. The patient may have complained of recurring sinusitis for years and a subsequent nasal obstruction on the same side as the sinusitis. The epithelial papilloma, although benign, has a 10% incidence of associated carcinoma.

Radiographic Features

The features may not be specific, and the diagnosis can be made only by histopathologic examination of the tissue.

Definition

The osteoma is the most common of the mesenchymal neoplasms in the paranasal sinuses. For a detailed description, see Chapter 22.

Clinical Features

Osteomas are almost twice as common in males as females and are most common in the second, third, and fourth decades. Most are usually slow growing and asymptomatic and thus are usually detected as an incidental finding in an examination made for another purpose. When symptoms do occur, they are the result of obstruction of the sinus ostium or infundibulum or are the result of erosion or deformity, orbital involvement, or intracranial extension. Those growing in the maxillary sinus may extend into the nose and cause nasal obstruction or a swelling of the side of the nose. They may expand the sinus and produce swelling of the cheek or hard palate. In cases extending to the orbit, the patient may have proptosis. In some cases, external fistulae have occurred. Osteomas of the maxillary sinus have been described after Caldwell-Luc operations.

Radiographic Features

Location.: Although osteomas occasionally develop in the maxillary sinus, they more often occur in the frontal and ethmoidal sinuses. The incidence in the maxillary antrum varies between 3.9% and 28.5% of the incidence in all paranasal sinuses.

Periphery and Shape.: The osteoma is usually lobulated or rounded and has a sharply defined margin (Fig. 27-12).

MALIGNANT NEOPLASMS OF THE PARANASAL SINUSES

Malignant neoplasms of the paranasal sinuses are rare, accounting for less than 1% of all malignancies in the body. Squamous cell carcinoma, comprising 80% to 90% of the cancers in this site, is by far the most common primary malignant neoplasm of the paranasal sinuses. Other primary neoplasms include adenocarcinoma, carcinomas of salivary gland origin, soft and hard tissue sarcomas, melanoma, and malignant lymphoma. Factors that contribute to a poor prognosis for cancer of the paranasal sinuses include the advanced stage of the disease when it is finally diagnosed and the close proximity of vital anatomic structures. The clinical signs and symptoms may masquerade as an inflammatory sinusitis. The early primary lesions may only appear as a soft tissue mass in the sinus before they cause bone destruction. The lesion may become extensive, involving the entire sinus, with radiographic evidence of bone destruction before symptoms become apparent. Therefore any unexplained radiopacity in the maxillary sinus of an individual older than 40 years should be investigated thoroughly.

Definition

Squamous cell carcinoma likely originates from metaplastic epithelium of the sinus mucosal lining.

Clinical Features

The most common symptoms of cancer in the maxillary sinus are facial pain or swelling, nasal obstruction, and a lesion in the oral cavity. The mean age of the patient is 60 years (range, 25 to 89 years). Twice as many men as women are affected. Lymph nodes are involved in about 10% of cases, and the symptoms are present for about 5 months before diagnosis.

The symptoms produced by malignant neoplasms in the maxillary sinus depend on which wall(s) of the sinus is/are involved. The medial wall is usually the first to become eroded, leading to such nasal signs and symptoms as obstruction, discharge, bleeding, and pain. These symptoms may appear trivial, and their significance may not be appreciated. Lesions that arise on the floor of the sinus may first produce dental signs and symptoms, including expansion of the alveolar process, unexplained pain and altered sensation of the teeth, loose teeth, swelling of the palate or alveolar ridge, and ill-fitting dentures. The neoplasm may erode the sinus floor and penetrate into the oral cavity. Such oral manifestations appear in 25% to 35% of patients with cancer in the maxillary sinus. When the lesion penetrates the lateral wall, facial and vestibular swelling becomes apparent and the patient may complain of pain and hyperesthesia of the maxillary teeth. Involvement of the sinus roof and the floor of the orbit cause signs and symptoms related to the eye: diplopia, proptosis, pain, and hyperesthesia or anesthesia and pain over the cheek and upper teeth. Invasion and penetration of the posterior wall lead to invasion of the muscles of mastication, causing painful trismus, obstruction of the eustachian tube causing a stuffy ear, and referred pain and hyperesthesia over the distribution of the second and third divisions of the fifth nerve.

Radiographic Features

Sometimes the radiographic findings, especially in early malignant disease of the paranasal sinuses, are nonspecific. It may not be possible to differentiate the early manifestations in radiographs of the maxillary sinus from the radiopacity of the sinus that develops in sinusitis and polyp formation. Evidence relies on changes seen in the surrounding bone, the sinus walls, and the maxillary alveolar process.

Location.: Most carcinomas occur in the maxillary sinuses, but involvement of the frontal and sphenoid sinuses is also comparatively common.

Internal Structure.: The internal aspect of the maxillary sinus has a soft tissue radiopaque appearance.

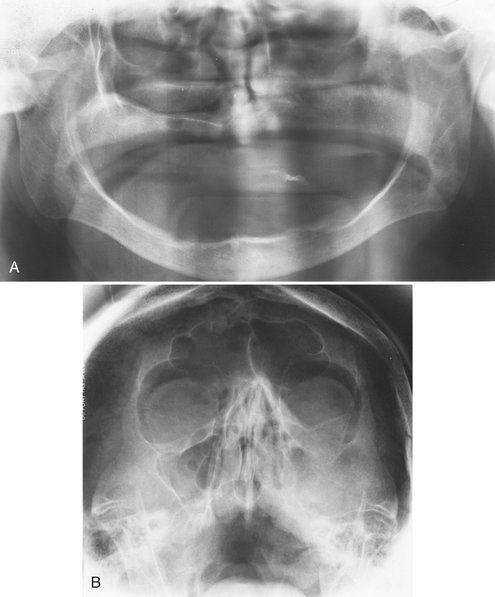

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: As the lesion enlarges, it may destroy sinus walls and in general, cause irregular radiolucent areas in the surrounding bone. A detailed examination of the adjacent alveolar process may reveal bone destruction around the teeth or irregular widening of the periodontal ligament space. Frequently the medial wall of the maxillary sinus is thinned or destroyed, although there may also be destruction of the floor and anterior or posterior walls that may be detected in the panoramic film. The medial wall of the maxillary sinus is best seen on the Caldwell and Waters projections. In addition to loss of the medial wall, it may extend into the nasal cavity.

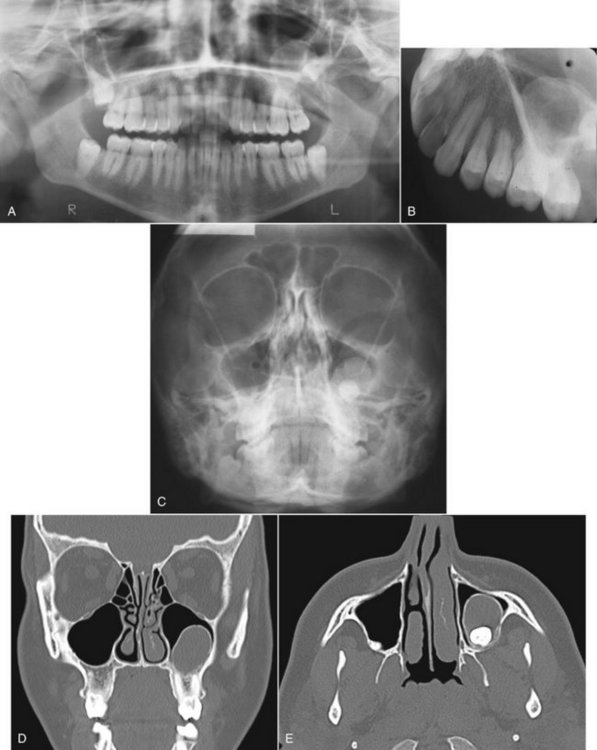

Additional Imaging

If a conventional radiograph of any radiopacified sinus reveals the slightest suggestion of bone destruction, advanced imaging is imperative (Fig. 27-13). On CT, the most characteristic sign of malignancy is invasion into the soft tissue facial planes beyond the sinus walls (Fig. 27-14). Consequently, CT is useful in revealing the extent of paranasal sinus neoplasms, especially when extension into the orbit, infratemporal fossa, or cranial cavity has occurred. MRI examinations are excellent for revealing the extent of soft tissue penetration into adjacent structures and in differentiating mucus accumulation from the soft tissue mass of the neoplasm.

FIG. 27-13 A, This panoramic image of a squamous cell carcinoma shows a loss of definition of the cortex of the left maxillary sinus, nasal floor, and alveolar crest. B, The Waters view of the same patient shows a similar loss of cortical integrity to the lateral wall of the left maxilla and radiopacification of the left maxillary sinus. (Courtesy Dr. K. Dolan.)

FIG. 27-14 A, This axial bone algorithm CT image of a squamous cell carcinoma of the left maxillary sinus shows destruction of the posterolateral wall and the medial wall of the sinus. B, The same axial image slice with soft tissue algorithm demonstrates extension of the malignant tumor into the surrounding soft tissues (arrows).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes all the conditions that may cause radiopacity of the antrum, such as sinusitis, large retention pseudocysts, and odontogenic cysts. It is important to note that bone destruction may also occur in infectious and some benign conditions. Neoplasms should be suspected in any older patient in whom chronic sinusitis develops for the first time without an obvious cause.

Management

Treatment of squamous cell carcinoma in the paranasal sinuses generally combines surgery and radiation therapy. Malignant neoplasms in the paranasal sinuses usually have a poor prognosis because they are usually well advanced by the time of diagnosis. Other factors contributing to the poor prognosis include frequently inaccurate preoperative staging and the complex anatomy of the region.

Synonyms

Invasive fungal sinusitis, inflammatory pseudotumor, fibroinflammatory pseudotumor, plasma cell granuloma, sinonasal fungal disease, mucormycosis, aspergillosis, zygomycosis of the paranasal sinuses, and Rhizopus sinusitis

Definition

Pseudotumor is a descriptive name for a group of apparently related diseases of fungal origin that occur in the paranasal sinuses and in other parts of the head and neck.

Clinical Features

Pseudotumor often occurs after a series of recurrent infections. The symptoms may not be very specific. There may be recurring pain and a mass simulating a neoplasm. The latter may cause erosion of the walls of the involved sinus and proptosis if the orbit is involved. Altered nerve function resulting from involvement of the nerve or occlusion of blood vessels by the mass has also been reported. Although cases have been reported in otherwise healthy individuals, many cases appear in patients who are immunocompromised or who have systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, von Willebrand disease, or myelodysplasia.

Radiographic Features

The radiographic findings in pseudotumor include masses simulating malignant neoplasms that cause erosion of bony walls of the involved sinuses.

Management

The treatment of pseudotumor, which can include debridement of the sinuses and administration of antifungal medication, a Caldwell-Luc surgical approach, and therapy, reflects the differences in the specific lesions included under the term pseudotumor of the sinuses, the exact location of the disease, the organism involved, and the medical status of the patient.

Extrinsic Diseases Involving the Paranasal Sinuses

Dental inflammatory lesions such as periodontal disease or rarefying or sclerosing osteitis may cause a localized mucositis in the adjacent floor of the maxillary antrum. This is a result of the diffusion of inflammatory exudate (mediators) beyond the cortical floor of the antrum and into the periosteum and the mucosal lining of the sinus. The localized type of mucositis related to dental inflammatory disease usually resolves in days or weeks after successful treatment of the underlying cause.

Radiographic Features

The involved mucosa presents as a homogeneous radiopaque, ribbon-shaped shadow that follows the contour of the floor of the maxillary sinus (see Fig. 27-5). The thickened mucosa is usually centered directly above the inflammatory lesion.

Definition

As previously described, the exudate from dental inflammatory lesions can diffuse through the cortical boundary of the antral floor. These products can strip and elevate the periosteal lining of the cortical bone of the floor of the maxillary antrum, stimulating the periosteum to produce an elevated thin layer of new bone adjacent to the root apex of the involved tooth (Fig. 27-15). The presence of one or more halolike layer(s) of new bone indicates inflammation of the periosteum.

Radiographic Features

Although the periosteal tissue is not visible on the radiograph per se, this is referred to as periosteal new bone formation. This new bone may take the form of one or more thin radiopaque lines, or the line may be very thick. This new bone should be centered directly above the inflammatory lesion.

BENIGN ODONTOGENIC CYSTS AND TUMORS

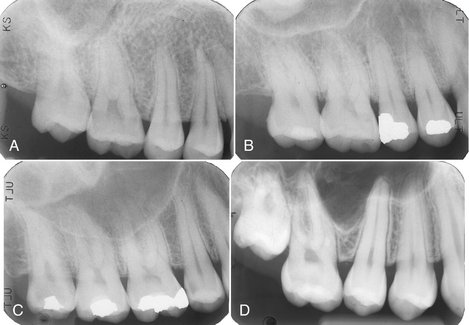

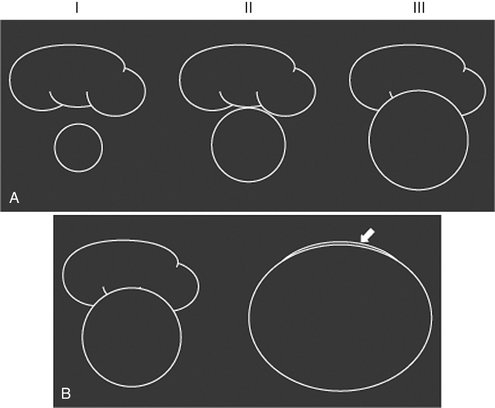

Odontogenic cysts are the most common group of extrinsic lesions that encroach on the maxillary sinuses. The most common are radicular cysts, followed by dentigerous cysts and odontogenic keratocysts (see Chapter 21 for detailed descriptions). As the odontogenic cyst grows, its border becomes indistinguishable from the sinus border. With continued growth, the cyst encroaches on the space of the sinus, displaces its borders, and the air-filled space decreases in volume (Fig. 27-16). A thin radiopaque line divides the contents of the cyst from the sinus cavity. This appearance is in contrast to a retention pseudocyst, which, being inside the sinus, does not have a cortex around its periphery.

FIG. 27-16 A, An odontogenic cyst or tumor develops adjacent to the floor of a sinus (I). As the lesion enlarges, it abuts the maxillary sinus floor (II) and ultimately displaces the floor superiorly as it enlarges (III). The border of the cyst and the border of the sinus are now the same line of bone. B, The lesion, as it continues to enlarge, may encroach on almost all the space of the sinus, leaving a small saddlelike sinus over it (arrow). The appearance may mimic sinusitis.

Radiographic Features

Periphery and Shape.: The invaginating cyst has a curved or oval shape defined by a corticated border.

Internal Structure.: The internal structure of the cyst is homogeneous and radiopaque relative to the air-filled sinus cavity. The degree of radiopacity may appear to be that of bone resulting from the extreme contrast to the radiolucent air within the sinus.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: The cyst may displace the floor of the maxillary antrum. Large dentigerous or odontogenic keratocysts can displace third molars as far as the floor of the orbit. In some cases the cyst may enlarge to the point that it has encroached on almost the entire sinus, and the residual sinus space may appear as a thin crescent of air adjacent to the cyst (see Fig. 27-16, B).

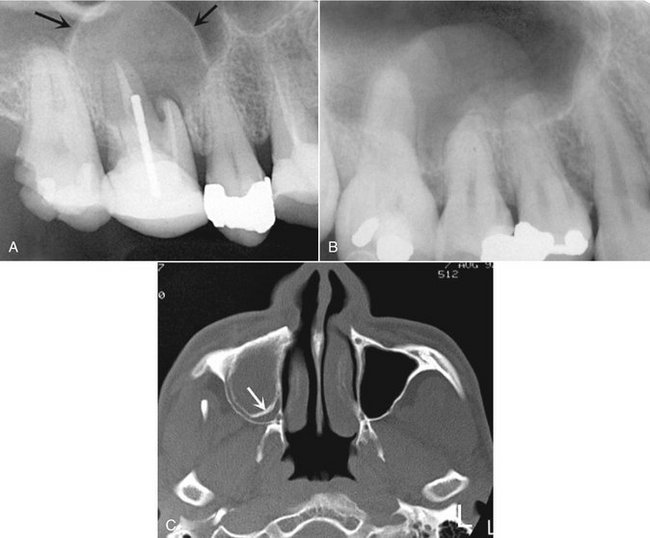

Differential Diagnosis

Odontogenic cysts must be differentiated from the relatively common retention pseudocyst. Although both lesions may have similar shapes, only odontogenic cysts have a cortex at the periphery (Fig. 27-17). If the odontogenic cyst were to become infected, the cortex may be thickened or lost in some areas. In the latter instance, it may become difficult to determine whether the lesion has arisen from outside or from within the sinus. However, in most cases careful scrutiny of the lesion will reveal some remaining cyst cortex. Also, the relationship to neighboring teeth may help to make this decision. This is true for all odontogenic cysts, including radicular cysts, dentigerous cysts, and keratocysts (Fig. 27-18). It is not usually possible to differentiate a dentigerous cyst from an odontogenic keratocyst that has a pericoronal relationship to the third molar. Very large cysts may completely efface the sinus cavity. When this occurs, no radiographic evidence may exist of the air space left, and it may appear as if the cyst is within the sinus. In this case, because of the radiopacity of the cyst, the appearance may resemble sinusitis with radiopacification of the sinus. Evaluation of such conditions is aided by noting that the wall of the cyst is often thicker and more regular than that of a sinus. In addition, the normal vascular markings on the wall of the maxillary sinus are not present on the walls of a cyst. A cyst that occupies the entire sinus usually causes expansion of the medial wall (middle meatus) of the sinus and will alter the sigmoid contour of the posterolateral wall of the sinus as viewed in axial CT images.

FIG. 27-17 A, Periapical image of a small radicular cyst; note the peripheral cortex (arrows) compared with B, a periapical image of a pseudocyst; note the lack of a peripheral cortex. C, Axial CT image of a large radicular cyst; note the peripheral cortex (arrow) inside the outer cortex of the sinus.

FIG. 27-18 A series of images showing displacement of the left maxillary sinus floor as a result of a developing dentigerous cyst associated with the maxillary left third molar. The corticated periphery of the cyst is well seen in the panoramic, occlusal, and Waters images (A, B, and C). The coronal CT image (D) shows the displaced floor of the left maxillary sinus, and the axial image (E) shows the bowing of the posterior sinus wall and the impacted tooth adjacent to it.

An antral loculation may occasionally have a round shape and sometimes appear to have a cortex. However, because the loculation contains air, which is more radiolucent than the fluid within a cyst, the loculation appears more radiolucent than the surrounding antrum.

After the successful treatment of an odontogenic lesion in the maxilla, healing will ensue in the affected area. This may include “collapse” of the bony cavity and remodeling of the sinus floor. The end result is the appearance of an irregularly shaped bone formation along the floor of the sinus.

Generally, benign odontogenic tumors can cause facial deformity, nasal obstruction, and displacement or loosening of teeth. For detailed descriptions of specific tumors, see Chapter 22. The nature of bony barriers in this region of the face, and the relatively good blood supply, are probably also responsible for efficient local spread. Some odontogenic tumors, particularly the ameloblastoma and the myxoma, show a more aggressive pattern of growth in the maxilla and have a close proximity to vital structures in the skull base. Therefore management of such tumors in the maxillae is often more aggressive than in cases involving the mandible.

Radiographic Features

Periphery and Shape.: The enlarging tumor may have a curved, oval, or multilocular shape that may be defined by a thin cortical border as it encroaches on the sinus. More aggressively growing tumors may even lack a portion of the border.

Internal Structure.: The internal structure of the tumor may have coarse or fine septae or regions of dystrophic calcification, depending on the histopathologic nature of the tumor.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: The tumor may displace the floor of the maxillary antrum and cause thinning of the peripheral cortex. As with odontogenic cysts, in some cases the tumor may enlarge to the point where it has almost completely encroached on the sinus air space, and this residual space may appear as a thin saddle over the tumor.

The bony walls of the sinus may be thinned or eroded, and adjacent structures may be displaced. A tooth or part of a tooth may be embedded in the neoplasm.

FIBROUS DYSPLASIA

Fibrous dysplasia may arise adjacent to any of the paranasal sinuses, cause displacement of sinus borders, and result in a smaller sinus on the affected side. For a detailed description of fibrous dysplasia, see Chapter 24.

Clinical Features

The involvement of the facial skeleton with fibrous dysplasia can result in facial asymmetry, nasal obstruction, proptosis, pituitary gland compression, impingement on cranial nerves, or sinus obliteration. Sinus obliteration results when the expanding dysplastic bone encroaches on it. The lesion may displace the roots of teeth and cause teeth to separate or migrate, but it usually does not cause root resorption. Fibrous dysplasia is more common in children and young adults, and growth of the dysplastic bone usually ceases at the age of skeletal maturity.

Radiographic Features

Periphery.: The lesion itself is usually not well defined, tending to blend into the surrounding bone. The external cortex of the bone as well as the sinus floor is intact but displaced.

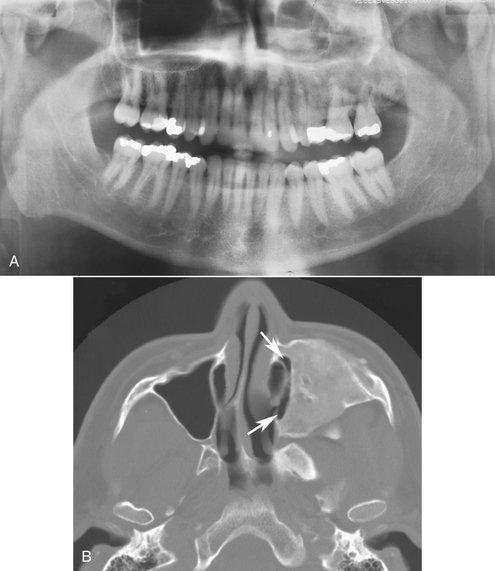

Internal Structure.: The normal radiolucent maxillary antrum may be partially or totally replaced by the increased radiopacity of this lesion. The degree of radiopacity depends on its stage of development and the relative amounts of bone and fibrous tissue present. Usually the radiopaque areas have the characteristic “ground-glass” appearance on extraoral radiographs or an “orange-peel” appearance on intraoral views (Fig. 27-19).

FIG. 27-19 A, Panoramic image of involvement of the left maxillary sinus with fibrous dysplasia; note the radiopacification of the left maxillary sinus compared with the right sinus. B, Axial CT image of the same case revealing almost complete filling of the sinus; a small medial segment remains (arrows). Note the very fine homogeneous bone pattern of the fibrous dysplasia.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of fibrous dysplasia in a relatively young person is usually not difficult. In contrast, Paget’s disease of bone does not usually obliterate the sinus. Ossifying fibroma, which may have an appearance that is similar to that of fibrous dysplasia, may also have a soft tissue capsule and may be more expansile. In some cases, however, the differential diagnosis of ossifying fibroma involving the antrum and fibrous dysplasia can be extremely difficult. The shape of the new bone encroaching on the internal aspect of the antrum often parallels the original shape of the external walls of the antrum in fibrous dysplasia.

DENTAL STRUCTURES DISPLACED INTO THE SINUSES

Tooth roots may be fractured from various forms of trauma, including iatrogenic causes. They may be displaced into the sinus during extraction or subsequent attempts to retrieve them.

Clinical Features

No specific features may be visible if the root was displaced into the sinus recently. However, the dentist may note the absence of the root fragment on examining the extracted tooth and may be unable to locate it anywhere else. Sometimes asking the patient to hold his or her nose while attempting to breathe out through it, similar to a Valsalva maneuver, will cause bubbles to appear within the blood contained within the fresh extraction socket.

If the patient has had the root or tooth in the sinus for a number of days, the presenting symptom may be sinusitis (see the previous discussion on sinusitis).

Radiographic Features

Location.: Premolar or molar teeth or root fragments may be displaced into the sinus because of their proximity. These may be found anywhere within the sinus, but more often they are located near the floor of the sinus because of gravity. Sometimes they may be submucosal, between the osseous wall of the sinus and the periosteum.

Lateral maxillary occlusal views are useful for examining the maxillary sinus for displaced teeth or root fragments. Other radiographs made along a different projection axis, such as a Waters view, may help in the three-dimensional localization.

Periphery and Shape.: No immediate evidence of change may be appreciated in the sinus, even when an oroantral fistula has been created. The disruption of the sinus wall may be difficult or impossible to see on radiographs if it is not in the mesial, distal, or superior (apical) part of the alveolar process.

Internal Structure.: In the early stages, no internal structural changes are present, except that the dental fragment may appear as a radiopaque mass of a size corresponding to the missing tooth or tooth root fragment.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.: The dental fragment usually has no effect on surrounding structures; however, a sinusitis may result (see changes described earlier in this chapter under sinusitis). A break in the floor of the maxillary sinus caused by the displacement of the tooth or fragment into the sinus may be present but difficult to appreciate.

Differential Diagnosis

Bony masses that are exostoses of the sinus wall or floor or septae within the sinus may mimic dental root fragments or even whole teeth. Antroliths may also have a similar appearance. The shape of the radiopacity or the presence of a pulp canal or layer of enamel may help in the differential diagnosis. It may also be possible to displace the tooth fragment by having the patient move the head abruptly between views. If the root tip remains in its socket, it may be superimposed radiographically over the maxillary sinus, but the presence of a lamina dura and periodontal ligament space indicate a position within the alveolar process.

The displaced tooth or root fragment may be subperiosteal, and thus interior to the osseous wall of the sinus, but not within the antral lumen. Alternatively, the root may have been forced out of the socket into the surrounding bone, into the submucosal space, or surrounding anatomic space such as the infratemporal space. Another possibility is for the fragment to be displaced into a cyst that was preoperatively mistaken for a loculus of the sinus cavity. Use of radiographs at different angles should help localize the dental structure.

Management

Management ranges from following up the patient to see whether a small root tip will be removed from the sinus through the ostium by ciliary action to surgically entering the sinus by a Caldwell-Luc procedure to remove the dental structure. Sinusitis may develop and should be managed with the appropriate treatment.

For other trauma involving the paranasal sinuses, see Chapter 29.

NORMAL DEVELOPMENT AND VARIATIONS

Dodd, GD, Jing, BS. Radiology of the nose, paranasal sinus and nasopharynx. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1977.

DuBrul, EL. Sicher’s oral anatomy, ed 7. St. Louis: Mosby; 1980.

Grant, JCB. A method of anatomy. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1958.

Hengerer, AS. Embryonic development of the sinuses. Ear Nose Throat J. 1984;63:134–136.

Karmody, CS, Carter, B, Vincent, ME. Developmental anomalies of the maxillary sinus. Trans Sect Otolaryngol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1977;84:723–728.

Lusted, LB, Keats, TE. Atlas of roentgenographic measurement, ed 3. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1972.

Ritter, FN. The paranasal sinuses: anatomy and surgical technique. St. Louis: Mosby; 1973.

Scuderi, AJ, Harnsberger, HR, Boyer, RS. Pneumatization of the paranasal sinuses: normal features of importance to the accurate interpretation of CT scans and MR images. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:1101–1104.

Shapiro, R. Radiology of the normal skull. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1981.

Som, PM. The paranasal sinuses. In: Bergeron RT, Osborn AG, Som PM, eds. Head and neck imaging: excluding the brain. St. Louis: Mosby, 1984.

Takahashi, R. The formation of the human paranasal sinuses. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl (Stockh). 1984;408:1–28.

Lloyd, GA. Diagnostic imaging of the nose and paranasal sinuses. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103:453–460.

Zinreich, SJ. Imaging of chronic sinusitis in adults: x-ray, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:445–451.

Robinson, K. Roentgenographic manifestations of benign paranasal disease. Ear Nose Throat J. 1984;63:144.

Dolan, K, Smoker, W. Paranasal sinus radiology, Part 4A: maxillary sinuses. Head Neck Surg. 1983;5:345–362.

Killey, HC, Kay, LA. The maxillary sinus and its dental implications. Bristol: John Wright; 1975.

Druce, HM. Diagnosis and medical management of recurrent and chronic sinusitis in adults. In: Gershwin ME, Incaudo GA, eds. Diseases of the sinuses. Ottawa, Canada: Humana Press, 1996.

Fireman, P. Diagnosis of sinusitis in children: emphasis on the history and physical examination. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:433–436.

Incaudo, G, Gershwin, ME, Nagy, SM. The pathophysiology and treatment of sinusitis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 1986;14:423–434.

Kennedy, DW. First-line management of sinusitis: a national problem? Surgical update. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;103:884–886.

Killey, HC, Kay, LA. The maxillary sinus and its dental implications. Bristol: John Wright; 1975.

Palacios, E, Valvassori, G. Computed axial tomography in otorhinolaryngology. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 1978;24:1–8.

Paparella, MM. Mucosal cyst of the maxillary sinus. Arch Otolaryngol. 1963;77:650–670.

Poyton, HG. Maxillary sinuses and the oral radiologist. Dent Radiogr Photogr. 1972;45:43–50.

Reilly, JS. The sinusitis cycle. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;103:856–861.

Shapiro, GG, Rachelefsky, GS. Introduction and definition of sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:417–418.

Zinreich, SJ. Imaging of chronic sinusitis in adults: x-ray, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:445–451.

Ash, JE, Raum, M. An atlas of otolaryngic pathology. New York: American Registry of Pathology; 1956.

Groves, J, Gray, RF. A synopsis of otolaryngology. Bristol: John Wright; 1985.

Potter, GD. Inflammatory disease of the paranasal sinuses. In: Valvassori GE, Potter GD, Hanefee WN, eds. Radiology of the ear, nose and throat. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1982.

Allard, RH, van der Kwast, WA, van der Waal, JI. Mucosal antral cysts: review of the literature and report of a radiographic survey. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;51:2–9.

Dolan, K, Smoker, W. Paranasal sinus radiology, Part 4A: maxillary sinuses. Head Neck Surg. 1983;5:345–362.

Gothberg, K, Little, JW, King, DR, et al. A clinical study of cysts arising from mucosa of the maxillary sinus. Oral Surg. 1976;41:52–58.

Hardy, G. Benign cysts of the antrum. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1939;48:649.

Kadymova, MI. Lymphangiectatic (false) cysts of the maxillary sinuses and their relation with allergy. Vestn Otorhinolaringol. 1966;28:58.

Kaffe, I, Littner, MM, Moskona, D. Mucosal-antral cysts: radiographic appearance and differential diagnosis. Clin Prev Dent. 1988;10:3–6.

McGregor, GW. Formation and histologic structure of cysts of the maxillary sinus. Arch Otolaryngol. 1928;8:505.

Mills, CP. Secretory cysts of the maxillary antrum and their relationship to the development of antrochoanal polypi. J Laryngol Otol. 1959;73:324–334.

Poyton, HG. Oral radiology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1982.

Ruprecht, A, Batniji, S, el-Neweihi, E. Mucous retention cyst of the maxillary sinus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;62:728–731.

Shafer, WG, Hine, MK, Levy, BM. A textbook of oral pathology, ed 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1983.

van Norstrand, AWP, Goodman, WS. Pathologic aspects of mucosal lesions of the maxillary sinus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1976;9:21–34.

Atherino, C, Atherino, T. Maxillary sinus mucopyoceles. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984;110:200.

Jones, JL, Kaufman, PW. Mucopyocele of the maxillary sinus. J Oral Surg. 1981;39:948.

Zizmor, JK, Noyek, AM. The radiologic diagnosis of maxillary sinus disease. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1976;9:93.

Killey, HC, Kay, LA. The maxillary sinus and its dental implications. Bristol: John Wright; 1975.

Poyton, H. Maxillary sinuses and the oral radiologist. Dent Radiogr Photogr. 1972;45:43–50.

Van Alyea, OE. Nasal sinuses. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1951.

MacDonald-Jankowski, DS. The involvement of the maxillary antrum by odontogenic keratocysts. Clin Radiol. 1992;45:31–33.

Goepfert, H, Luna, MA, Lindberg, RD, et al. Malignant salivary gland tumors of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:662–668.

St-Pierre, S, Baker, SR. Squamous cell carcinoma of the maxillary sinus: analysis of 66 cases. Head Neck Surg. 1983;5:508–513.

Rogers, JH, Fredrickson, JM, Noyek, AM. Management of cysts, benign tumors, and bony dysplasia of the maxillary sinus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1976;9:233–247.

Dolan, K, Smoker, W. Paranasal sinus radiology, Part 4B: maxillary sinuses. Head Neck Surg. 1983;5:428–446.

Goodnight, J, Dulguerov, P, Abemayor, E. Calcified mucor fungus ball of the maxillary sinus. Am J Otolaryngol. 1993;14:209–210.

Reuben, BM. Odontoma of the maxillary sinus: a case report. Quintessence Int Dent Dig. 1983;14:287–290.

Samy, LL, Mostofa, H. Osteoma of the nose and paranasal sinuses with a report of twenty-one cases. J Laryngol Otol. 1971;85:449–469.

Hames, RS, Rakoff, SJ. Diseases of the maxillary sinus. J Oral Med. 1972;27:90–95.

Reaume, C, Wesley, RK, Jung, B, et al. Ameloblastoma of the maxillary sinus. J Oral Surg. 1980;38:520–521.

Malignant Neoplasms of the Paranasal Sinuses

Batsakis, JG. Tumors of the head and neck, ed 2. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1979.

St-Pierre, S, Baker, S. Squamous cell carcinoma of the maxillary sinus: analysis of 66 cases. Head Neck Surg. 1983;5:508–513.

Zizmor, J, Noyek, AM. Cysts, benign tumors and malignant tumors of the paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1973;6:487–508.

Batsakis, JG, Rice, DH, Solomon, AR. The pathology of head and neck tumors: squamous and mucous-gland carcinomas of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and larynx: part 6. Head Neck Surg. 1980;2:497–508.

Bridger, M, Beale, F, Bryce, D. Carcinoma of the paranasal sinuses: a review of 158 cases. J Otolaryngol. 1978;7:379–388.

Eddleston, B, Johnson, R. A comparison of conventional radiographic imaging and computed tomography in malignant disease of the paranasal sinuses and the post-nasal space. Clin Radiol. 1983;34:161–172.

Haso, AN. CT of tumors and tumor-like conditions of the paranasal sinuses. Radiol Clin North Am. 1984;22:119–130.

Larheim, TA, Kolbenstvedt, A, Lien, H. Carcinoma of maxillary sinus, palate and maxillary gingiva, occurrence of jaw destruction. Scand J Dent Res. 1984;92:235–240.

Lund, VJ, Howard, DJ, Lloyd, GA. CT evaluation of paranasal sinus tumors for cranio-facial resection. Br J Radiol. 1983;56:439–446.

Mancuso, A, Hanafee, WN, Winter, J, et al. Extensions of paranasal sinus tumors and inflammatory disease: an evaluation by CT and pluri- directional tomography. Neuroradiology. 1978;16:449–453.

St-Pierre, S, Baker, SR. Squamous cell carcinoma of the maxillary sinus: analysis of 66 cases. Head Neck Surg. 1983;5:508–513.

Thomas, GK, Kasper, KA. Ossifying fibroma of the frontal bone. Arch Otolaryngol. 1966;83:43–46.

Tsaknis, PJ, Nelson, JF. The maxillary ameloblastoma: an analysis of 24 cases. J Oral Surg. 1980;38:336–342.

Weber, A, Tadmore, R, Davis, R, et al. Malignant tumors of the sinuses: radiologic evaluation, including CT scanning, with clinical and pathologic correlation. Neuroradiology. 1978;16:443–448.

Butugan, O, Sanchez, TG, Gonçalez, F, et al. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: predisposing factors, diagnosis, therapy, complications and survival. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 1996;117:53.

Del Valle Zapico, A, Rubio Suárez, A, Mellado Encinas, A, et al. Mucormycosis of the sphenoid sinus in an otherwise healthy patient: case report and literature review. J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:471–473.

Ishida, M, Taya, N, Noiri, T, et al. Five cases of mucormycosis in paranasal sinuses. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993;501(Suppl):92–96.

Lee, BL, Holland, GN, Glasgow, BJ. Chiasmal infarction and sudden blindness caused by mucormycosis in AIDS and diabetes mellitus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:895–896.

Muzaffar, M, Hussain, SI, Chughtai, A. Plasma cell granuloma: maxillary sinuses. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:357–358.

Ng, TT, Campbell, CK, Rothera, M, et al. Successful treatment of sinusitis caused by Cunninghamella bertholetiae. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:313–316.

Ozhan, S, Araç, M, Isik, S, et al. Pseudotumor of the maxillary sinus in a patient with von Willebrand’s disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:950–951.

Perolada Valmana, JM, Morera Perez, C, Blanes Julia, M, et al. Mucormycosis of the paranasal sinuses. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 1996;117:51–52.

Som, PM, Brandwein, MS, Maldjian, C, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the maxillary sinus: CT and MR findings in six cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:689–692.

Tkatch, LS, Kusne, S, Eibling, D. Successful treatment of zygomycosis of the paranasal sinuses with surgical debridement and amphotericin B colloidal dispersion. Am J Otolaryngol. 1993;14:249–253.

Utas, C, Unlühizarci, K, Okten, T, et al. Acute renal failure associated with rhinosinuso-orbital mucormycosis infection in a patient with diabetic nephropathy [letter]. Nephron. 1995;71:235.

Zapater, E, Armengot, M, Campos, A, et al. Invasive fungal sinusitis in immunosuppressed patients: report of three cases. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 1996;50:137–142.