Developmental Disturbances of the Face and Jaws

Developmental disturbances affect the normal growth and differentiation of craniofacial structures. As a consequence, they are usually first discovered in infancy or childhood. Many of the conditions discussed in this chapter have an unknown etiology. Some are caused by known and recently discovered genetic mutations, whereas others result from environmental factors. These conditions result in a variety of abnormalities of the face and jaws including abnormalities of structure, shape, organization, and function of hard and soft tissues.

Common Developmental Abnormalities

There are a multitude of conditions that affect the morphogenesis of the face and jaws, many of which are rare syndromes. This chapter briefly reviews the more common developmental abnormalities that may be encountered in dental practice.

CLEFT LIP AND PALATE

A failure of fusion of the developmental processes of the face during fetal development may result in a variety of facial clefts. Cleft lip/palate (CL/P) and cleft palate (CP) are the most common developmental craniofacial anomalies. Their incidence varies with geographic location, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. In Caucasian populations the incidence of cleft lip is 1 : 800 to 1 : 1000 live births, and the incidence of cleft palate is approximately 1 : 1000. Cleft lip with or without cleft palate and cleft palate are two different conditions with different etiologies. CL/P results from a failure of fusion of the medial nasal process with the maxillary process. This condition can range in severity from a unilateral cleft lip to bilateral complete clefting through the lip, alveolus, and hard and soft palate in the most severe cases. CP develops from a failure of fusion of the lateral palatal shelves. The minimal manifestation of cleft palate is a submucous cleft. Here, the palate appears to be intact except for notching of the uvula (bifid uvula) or notching in the posterior border of the hard palate detectable by palpation. The most severe presentation is complete clefting of the hard and soft palate. The precise etiology of orofacial clefting is not completely understood. However, most cases of CL/P and CP are considered to be multifactorial with a strong genetic component. CL/P and CP can each be associated with other abnormalities, as part of a genetic malformation syndrome such as 22q.11 deletion syndrome (velocardiofacial syndrome—cleft palate and facial and cardiac abnormalities) or van der Woude syndrome (cleft lip and/or cleft palate and lip pits). Other factors that are implicated in the development of orofacial clefts include nutritional disturbances (prenatal folate deficiency); environmental teratogenic agents (maternal smoking, in utero exposure to anticonvulsants); stress, which results in increased secretion of hydrocortisone; defects of vascular supply to the involved region; and mechanical interference with the fusion of the embryonic processes (cleft palate in Pierre Robin sequence). Clefts involving the lower lip and mandible are extremely rare.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The frequency of CL/P and CP varies with sex and race but in general CL/P is most common in males and CP is more common in females. Both conditions are more common in Asians and Hispanics than blacks or Caucasians. The severity of CL/P varies from a notch in the upper lip to a cleft involving only the lip to extension into the nostril, resulting in deformity of the ala of the nose. As CL/P increases in severity, the cleft will include the alveolar process and palate. Bilateral cleft lip is more frequently associated with CP. CP also varies in severity, ranging from involvement of only the uvula or soft palate to extension all the way through the palate to include the alveolar process in the region of the lateral incisor on one or both sides. With involvement of the alveolar process there is an increase in frequency of dental anomalies in the region of the cleft, including missing, hypoplastic, and supernumerary teeth and enamel hypoplasia. Dental anomalies are also more prevalent in the mandible in these patients. In both CL/P and CP the palatal defects interfere with speech and swallowing. Affected individuals with palatal clefts are also at increased risk for recurrent middle ear infections because of the abnormal anatomy and function of the eustachian tube.

Radiographic Features

The typical appearance is a well-defined vertical radiolucent defect in the alveolar bone, including numerous associated dental anomalies (Figs. 30-1 and 30-2). These may include the absence of the maxillary lateral incisor and the presence of supernumerary teeth in this region. Often the involved teeth are malformed and poorly positioned. In patients with CL/P, there may be a mild delay in the development of maxillary and mandibular teeth and an increased incidence of hypodontia in both arches. The osseous defect may extend to include the floor of the nasal cavity. In patients with a repaired cleft, a well-defined osseous defect may not be apparent but only a vertically short alveolar process at the cleft site.

FIG. 30-1 Cleft lip/palate results in defects in the alveolar ridge and abnormalities of the dentition. A, Bilateral clefts of the maxilla in the lateral incisor regions and defects of the dentition. B, Lateral cephalometric view showing underdevelopment of the maxilla.

FIG. 30-2 Cone-beam computed tomographic images of patient with left unilateral cleft lip/palate. A, Coronal view. Note the discontinuity in the nasal floor visible on the patient’s left side. B, Sagittal view of same patient, showing the maxillary hypoplasia and deficient palatal anatomy. (Images courtesy Dr. Sean Edwards, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.)

Management

Management of CL/P and CP is complex, requiring the coordinated efforts of a multidisciplinary team known as a cleft palate team. This team usually includes a plastic and reconstructive surgeon, an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, an ear, nose, and throat surgeon, an orthodontist, a dentist, a speech therapist, a psychologist, a nutritionist, and a social worker. Clefts of the palate are usually surgically repaired within the first year of life, whereas clefts of the lip are usually repaired within the first 3 months to aid in feeding and maternal-infant bonding. The bone in the cleft site is often augmented with bone grafting before replacement of missing teeth with either fixed or removable prosthodontics or dental implants. Orthodontic treatment is usually necessary to recreate a normal arch form and functional occlusion.

CROUZON SYNDROME

Definition

Crouzon syndrome (CS) is an autosomal dominant skeletal dysplasia characterized by variable expressivity and almost complete penetrance. It is one of many diseases characterized by premature craniosynostosis (closure of cranial sutures). Its incidence is estimated at 1 : 25,000 births. Of these cases, 33% to 56% may arise as a consequence of spontaneous mutations, with the remaining being familial. CS is caused by a mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor II on chromosome 10. Mutations at this site are also responsible for other craniosynostosis syndromes with similar facial features but clinically visible limb abnormalities. In patients with CS the coronal suture usually closes first and eventually all cranial sutures close early. There is also premature fusion of the synchondroses of the cranial base. The subsequent lack of bone growth perpendicular to the synchondroses and cranial coronal sutures produces the characteristic cranial shape and facial features.

Clinical Features

Patients characteristically have brachycephaly (short skull front to back), hypertelorism (increased distance between eyes), and orbital proptosis (protruding eyes) (Fig. 30-3, A and B). In familial cases, the minimal criteria for diagnosis are hypertelorism and orbital proptosis. Patients may become blind as a result of early suture closure and increased intracranial pressure. The nose often appears prominent and pointed because the maxilla is narrow, and short in a vertical and an anteroposterior dimension. The anterior nasal spine is hypoplastic and retruded, failing to provide adequate support to the soft tissue of the nose. The palatal vault is high and the maxillary arch narrow and retruded, resulting in crowding of the dentition.

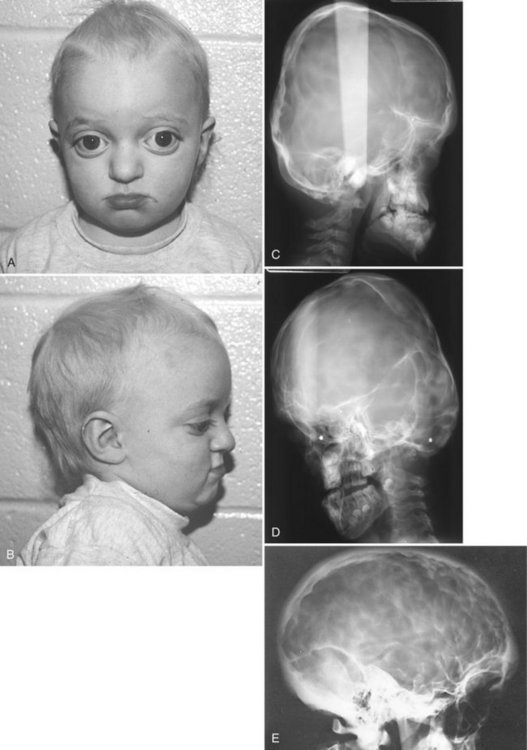

FIG. 30-3 A and B, Characteristic facial features of Crouzon syndrome in this 2-year-old boy include orbital proptosis, hypertelorism, and midfacial hypoplasia. Rarely, they may precede the radiographic features of sutural synostosis. C, Lateral and, D, 45-degree skull views demonstrating the short anterior-posterior dimension of the skull, digital impressions, and hypoplastic maxilla. E, Lateral skull of another patient demonstrating prominent digital markings. (Courtesy Department of Radiology, Baylor University Hospital, Dallas, Tex.)

Radiographic Features

General Radiographic Features.: The earliest radiographic signs of cranial suture synostosis are sclerosis and overlapping edges. Sutures that normally should look radiolucent on the skull film will not be detectable or will show sclerotic changes. Interestingly, on rare occasions the facial features may present before radiographic evidence of sutural synostosis. Premature fusion of the cranial base leads to diminished facial growth. In some cases, prominent cranial markings are noted, which are also seen in normally growing patients, but are more prominent because of an increase in intracranial pressure from the growing brain. These markings may be seen as multiple radiolucencies appearing as depressions (so-called digital impressions) of the inner surface of the cranial vault, which results in a beaten metal appearance (see Fig. 30-3, C to E).

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: The lack of growth in an anteroposterior direction at the cranial base results in maxillary hypoplasia, creating a Class III malocclusion in some patients. The maxillary hypoplasia contributes to the characteristic orbital proptosis because the maxilla forms part of the inferior orbital rim and if severely hypoplastic fails to adequately support the orbital contents. The mandible is typically smaller than normal but appears prognathic in relation to the severely hypoplastic maxilla.

Differential Diagnosis

Premature craniosynostosis, either isolated or part of a genetic syndrome, is a fairly common disorder.

The incidence of CS is reported to range from 1 : 2100 to 1 : 2500 births. Other causes of craniosynostosis must be differentiated from CS, including other syndromic forms of craniosynostosis and nonsyndromic coronal craniosynostosis. The characteristic facial features must be present to suggest CS.

Management

The craniofacial features of CS worsen over time because of the abnormal craniofacial growth. Early diagnosis permits surgical and orthodontic treatment from infancy through adolescence, coordinated by a craniofacial team. The objectives of these treatments are to allow normal brain growth and development by preventing increased intracranial pressure, protect the eyes by providing adequate bony support, and improve facial esthetics and occlusal function. Because of early diagnosis and improvements in medical and dental care, most patients have normal intelligence and can expect a normal life span.

HEMIFACIAL MICROSOMIA

Hemifacial hypoplasia, craniofacial microsomia, lateral facial dysplasia, Goldenhar syndrome, and oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia

Definition

Hemifacial microsomia (HFM) is the second most common developmental craniofacial anomaly after cleft lip and palate, affecting approximately 1 : 56,000 live births. Patients with HFM typically display reduced growth and development of half of the face as a result of abnormal development of the first and second branchial arches. This malformation sequence is usually unilateral but occasionally may involve both sides (craniofacial microsomia). When the whole side of the face is involved, the mandible, maxilla, zygoma, external and middle ear, hyoid bone, parotid gland, vertebrae, fifth and seventh cranial nerves, musculature, and other soft tissues are diminished in size and sometimes fail to develop. Delayed dental eruption and hypodontia on the affected side have also been reported. Most cases occur spontaneously, but familial cases demonstrating autosomal dominant inheritance have been reported. There is a male predominance of 3 : 2 and a right side predominance of 3 : 2. Cases with vertebral abnormalities and epibulbar dermoids have been considered to form a separate category within this condition, known as Goldenhar syndrome or oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia.

Clinical Features

HFM is usually apparent at birth. Patients with this condition have a striking appearance caused by progressive failure of the affected side to grow, which gives the involved side of the face a reduced dimension. In addition, aplasia or hypoplasia of the external ear (microtia) is common, and the ear canal is often missing. In some patients the skull is diminished in size. In about 90% of cases, there is malocclusion on the affected side. The midsagittal plane of the patient’s face is curved toward the affected side. The occlusal plane will often be canted up to the affected side.

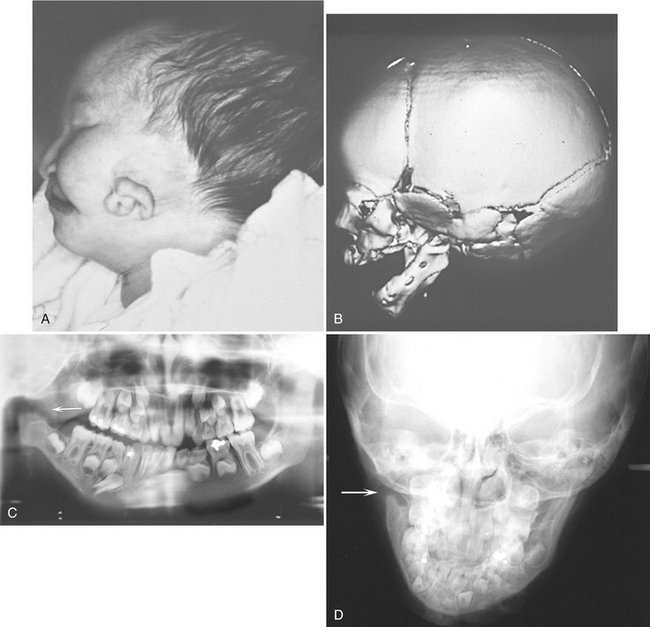

Radiographic Features

The primary radiographic finding is a reduction in the size of the bones on the affected side. This change is clearest in the mandible, which may show a reduction in the size of or, in severe cases, lack of any development of the condyle, coronoid process, or ramus. The body is reduced in size, and a portion of the distal aspect may be missing (Fig. 30-4). The dentition on the affected side may show a reduction in the number or size of the teeth. Computed tomographic (CT) examination shows a reduction in the size of the muscles of mastication and muscles of facial expression and hypoplasia or atresia of the auditory canal and ossicles of the middle ear. The course of the facial nerve is often shown to be abnormal on CT examination of the temporal bone.

FIG. 30-4 A and B, Hemifacial microsomia, showing reduced size and malformation of the left ear and left side of the mandible. A, Clinical photograph of infant with hemifacial microsomia. B, Three-dimensional CT image of the affected side shows the extent of the bony malformation. Note the complete absence of the temporomandibular joint and coronoid process as well as auditory canal atresia. C and D, A panoramic image and a posteroanterior skull view of other cases showing lack of development of ramus, coronoid process, and condyle (arrows). (A and B, courtesy Dr. Arlene Rozzelle, Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit, Mich.)

Differential Diagnosis

The features of hemifacial microsomia are characteristic. Condylar hypoplasia, especially that caused by a fracture at birth or by juvenile arthrosis (Boering’s arthrosis), may be similar, but it does not produce the ear changes (see Chapter 26). Exposure of the face of a child to radiation therapy during growth also may result in underdevelopment of the irradiated tissues. In progressive hemifacial atrophy (Parry-Romberg syndrome), the changes will become more severe over time but are generally not present at birth, and the ears are normal.

Management

The mandibular abnormalities may be corrected by conventional orthognathic surgery or distraction osteogenesis to lengthen the ramus on the affected side. Orthodontic intervention may correct or prevent malocclusion. The ear abnormalities may be repaired by plastic surgery or corrected with maxillofacial prosthetics, and the hearing loss may be partly corrected by hearing aids. In bilateral cases with profound hearing loss (Goldenhar syndrome), cochlear implants may be used to correct severe hearing loss.

TREACHER COLLINS SYNDROME

Definition

Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS) is an autosomal dominant disorder of craniofacial development. It is the most common type of mandibulofacial dysostosis, with an incidence of 1 : 50,000. TCS has variable expressivity and complete penetrance. Approximately half of cases arise as the result of sporadic mutation; the rest are familial. TCS is caused by a mutation in the TCOF1 gene on chromosome 5.

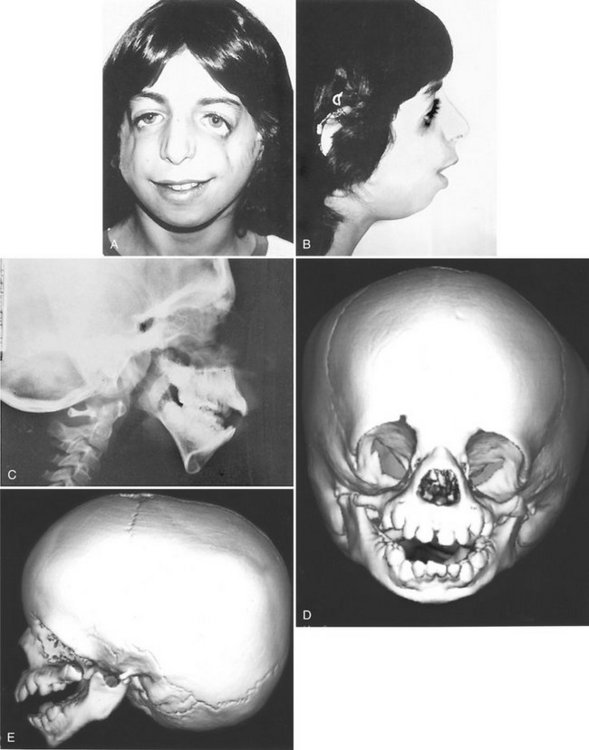

Clinical Features

Individuals with TCS have a wide range of anomalies, depending on the severity of the condition. The most common clinical findings are relative underdevelopment or absence of the zygomatic bones, resulting in a small narrow face; a downward inclination of the palpebral fissures; underdevelopment of the mandible, resulting in a down-turned, wide mouth; malformation of the external ears; absence of the external auditory canal; and occasional facial clefts (Fig. 30-5, A and B). The palate develops with a high arch or cleft in 30% of cases. Hypoplasia of the mandible and a steep mandibular angle results in an Angle Class II anterior open-bite malocclusion. Hypoplasia or atresia of the external ear, auditory canal, and ossicles of the middle ear may result in partial or complete deafness.

FIG. 30-5 A and B, Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS). Note the characteristic facies: downward-sloping palpebral fissures, colobomas of the outer third of the lower lids, depressed cheekbones, receding chin, little if any nasofrontal angle, and a nose that appears relatively large. C, Lateral skull image demonstrating short mandibular rami, steep mandibular angle, and an anterior open bite. The zygomas are poorly formed. D and E, Three-dimensional CT images of young child with TCS show the extent of the bony abnormalities, including the bilateral auditory canal atresia, aplasia of the zygomatic arch, and hypoplasia of the mandibular ramus with characteristic “curved” shape of the mandibular body and pronounced antegonial notching.

Radiographic Features

A striking finding is the hypoplastic or missing zygomatic bones and hypoplasia of the lateral aspects of the orbits. The auditory canal, mastoid air cells, and articular eminence often are smaller than normal or are absent. The maxilla and especially the mandible are hypoplastic, showing accentuation of the antegonial notch and a steep mandibular angle, which gives the impression that the body of the mandible is bending in an inferior and posterior direction (see Fig. 30-5, C to E). The ramus is especially short. The condyles are positioned posteriorly and inferiorly. The maxillary sinuses may be underdeveloped or absent.

Differential Diagnosis

Other disorders that may result in severe hypoplasia of the entire mandible include condylar agenesis, Hallermann-Streiff syndrome, Nager syndrome, and Pierre Robin sequence, which can be a part of several other genetic syndromes.

Management

Comprehensive treatment of TCS is optimally provided by a multidisciplinary craniofacial team. Growth of the facial bones during adolescence results in some cosmetic improvement. Surgical intervention, including bilateral distraction osteogenesis of the mandible, may be used to improve the osseous defects. Treatment of the external ear defects may involve plastic and reconstructive surgery or maxillofacial prosthetics. Hearing aids or cochlear implants may be used to treat the hearing loss, depending on the severity. Coordinated orthodontics and orthognathic surgery are often used to treat the malocclusion and improve function and esthetics.

CLEIDOCRANIAL DYSPLASIA

Definition

Cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) is an autosomal dominant malformation syndrome affecting bones and teeth; it affects both sexes equally. Its prevalence is estimated at 1 : 1,000,000. It can be inherited or arise as a result of sporadic mutation. CCD is caused by a mutation in the Runx2 gene on chromosome 6. This gene codes for anoasteoblast-specific transcription factor. It has variable expressivity and almost complete penetrance.

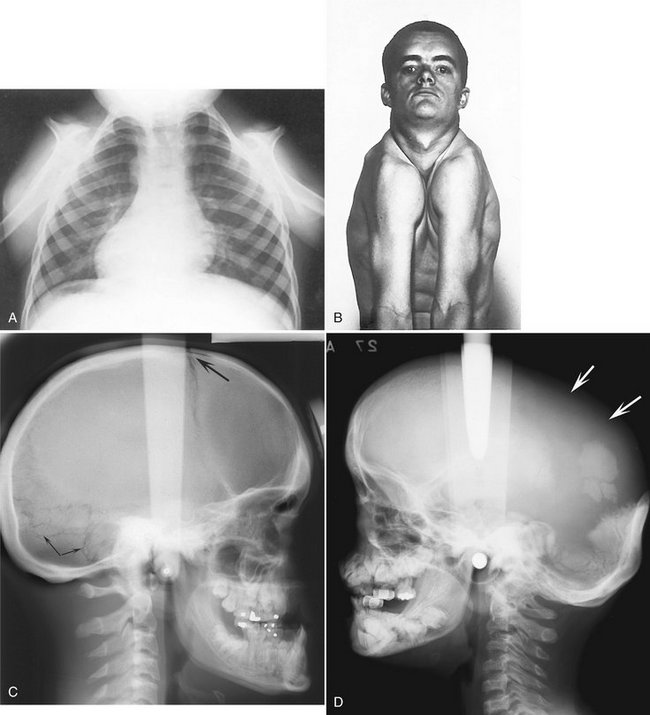

Clinical Features

Although the disease affects the entire skeleton, CCD primarily affects the skull, clavicles, and dentition. Affected individuals have been shown to be of shorter stature than unaffected relatives, but not short enough for this to be considered a form of dwarfism. The face appears small in contrast to the cranium as a result of hypoplasia of the maxilla and a brachycephalic skull (reduced anteroposterior dimension with increased skull width), and the presence of frontal and parietal bossing. The paranasal sinuses may be underdeveloped. There is delayed closure of the cranial sutures and the fontanels may remain patent years beyond the normal time of closure. The bridge of the nose may be broad and depressed, with hypertelorism (excessive distance between the eyes). The complete absence (aplasia) or reduced size (hypoplasia) of the clavicles allows excessive mobility of the shoulder girdle (Fig. 30-6, A and B).

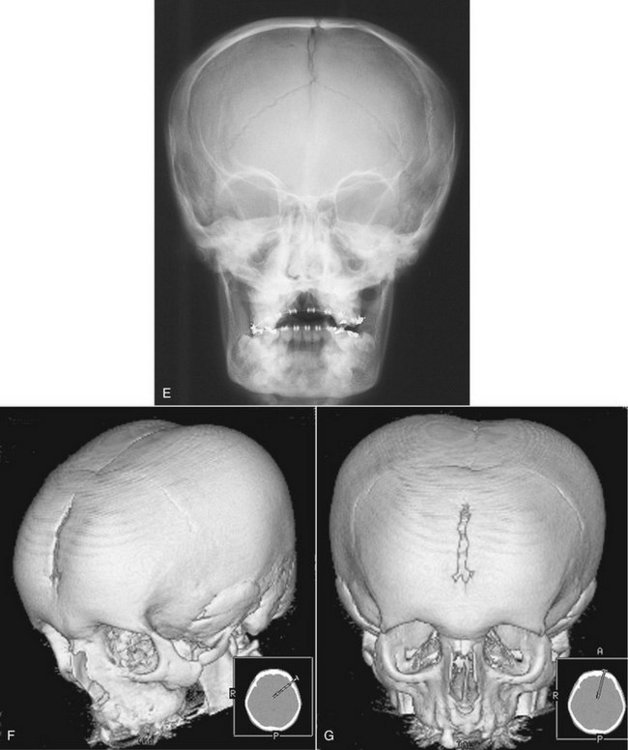

FIG. 30-6 Cleidocranial dysplasia. A, Chest radiograph; note the absence of clavicles. B, The result is excessive mobility of the shoulders. Note also the frontal bossing and underdeveloped maxilla. C, On a lateral radiograph, note the wormian (sutural) bones in the occipital region (arrows) and the open fontanel (large arrow). D, A lateral skull film showing a lack of development of the parietal bones (arrows). E, A posteroanterior skull film. The brachycephaly results in a light bulb–like shape to the silhouette of the skull and mandible. F, Three-dimensional CT reconstruction with oblique orientation shows the typical skull shape; note the parietal and frontal bossing and open metopic suture in this 18-year-old man. G shows the light-bulb shape of the skull and the open metopic suture. (A courtesy Department of Radiology, Baylor University Hospital, Dallas, Tex., F and G courtesy Dr. Sean Edwards, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.)

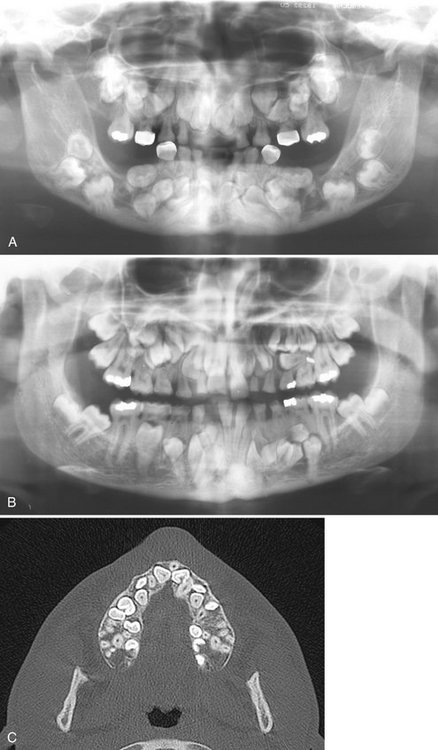

The dental abnormalities produce most of the morbidity associated with CCD and are often the reason for diagnosis in mildly affected individuals. Characteristically, patients with this disease show prolonged retention of the primary dentition and delayed eruption of the permanent dentition. Extraction of primary teeth does not adequately stimulate eruption of underlying permanent teeth. A study of teeth from patients with CCD revealed a paucity or a complete absence of cellular cementum on both erupted and unerupted teeth. Often unerupted supernumerary teeth are present, and considerable crowding and disorganization of the developing permanent dentition may occur. Recently the number of supernumerary teeth has been correlated with a reduction in skeletal height in these patients.

Radiographic Features

General Radiographic Features.: The characteristic skull findings are brachycephaly, delayed or failed closure of the fontanels, open skull sutures, and multiple wormian bones (small, irregular bones in the sutures of the skull that are formed by secondary centers of ossification in the suture lines) (see Fig. 30-6, C to G). In the most severe cases, very little formation of the parietal and frontal bones may occur. Typically the clavicles are underdeveloped to varying degrees and, in approximately 10% of cases, they are completely absent. Other bones also may be affected, including the long bones, vertebral column, pelvis, and bones of the hands and feet.

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: In CCD the maxilla and paranasal sinuses characteristically are underdeveloped, resulting in maxillary micrognathia. The mandible is usually normal size. A patent (open) mandibular symphysis has been reported in 3% of adults and 64% of children. Several investigators have described the alveolar bone overlying unerupted teeth as being denser than usual, with a coarse trabecular pattern in the mandible. This correlates with the histologic findings of decreased resorption and multiple reversal lines. It may account for the delayed eruption in teeth not mechanically obstructed by supernumerary and other unerupted teeth.

Radiographic Features Associated with the Teeth.: Characteristic features include prolonged retention of the primary dentition and multiple unerupted permanent and supernumerary teeth (Fig. 30-7). The number of supernumerary teeth varies; as many as 63 in one individual have been reported. The unerupted teeth develop most commonly in the anterior maxilla and premolar regions of the jaws. Many resemble premolars and these unerupted teeth may develop dentigerous cysts. The supernumerary teeth develop, on average, 4 years later than the corresponding normal teeth. Because of this, it has been proposed that the supernumerary teeth represent a third dentition.

FIG. 30-7 A and B, Panoramic images of cleidocranial dysplasia; note the prolonged retention of the primary dentition and multiple unerupted supernumerary teeth and the lack of normal coronoid notches. C, Axial CT view revealing multiple unerupted teeth, useful in identification and localization of the unerupted teeth. (C courtesy Dr. Sean Edwards, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.)

Differential Diagnosis

CCD may be identified by the family history, excessive mobility of the shoulders, clinical examination of the skull, and pathognomonic radiographic findings of prolonged retention of the primary teeth with multiple unerupted supernumerary teeth. Other conditions associated with multiple unerupted and supernumerary teeth, such as Gardner’s syndrome and pycnodysostosis must be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Management

In CCD dental care should include the removal of primary and supernumerary teeth to improve the possibility of spontaneous eruption of the permanent teeth. The bone overlying the normal permanent teeth should be removed to expose the crown when half of the root is formed to aid their eruption. Autotransplantation of teeth has been shown to be a successful strategy to treat older patients. Ideally patients should be identified early, before the age of 5 years, to take advantage of combined orthodontic/surgical treatment. Prosthodontic rehabilitation with dental implants has been used in some cases. Patients should be monitored for development of distal molars and cysts until late adolescence. Surgical treatment of the bony defects of the skull is often done to address esthetic concerns. In those cases, three-dimensional CT imaging is used to visualize the size and thickness of such defects and plan for harvesting of bone graft material from other parts of the skull (see Fig. 30-6, A to C).

HEMIFACIAL HYPERPLASIA

Definition

Hemifacial hyperplasia is a condition in which half of the face, including the maxilla alone or with the mandible, or in concert with other parts of the body, grows to unusual proportions. The cause of this condition is unknown. Some cases are associated with genetic diseases such as Beckwith-Weidemann syndrome.

Clinical Features

Hemifacial hyperplasia begins at birth and usually continues throughout the growing years. In some cases it may not be recognized at birth, but it becomes more apparent with growth. It often occurs with other abnormalities, including mental deficiency, skin abnormalities, compensatory scoliosis, genitourinary tract anomalies, and various neoplasms, including Wilms’ tumor of the kidney, adrenocortical tumor, and hepatoblastoma (Beckwith-Weidemann syndrome). Females and males are affected with approximately equal frequency. The dentition of affected individuals may show unilateral enlargement, accelerated development, and premature loss of primary teeth. The tongue and alveolar bone enlarge on the involved side.

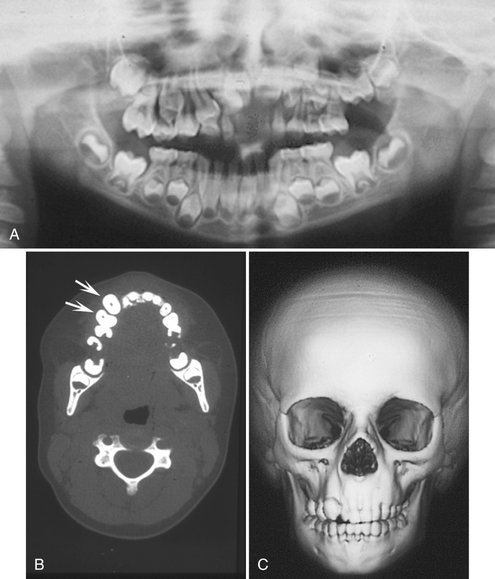

Radiographic Features

Radiographic examination of the skulls of these patients reveals, on the affected side, enlargement of the bones, including the mandible (Fig. 30-8), maxilla, zygoma, and frontal and temporal bones. There have been a few cases reported involving only one side of the maxilla or one side of the mandible.

FIG. 30-8 Hemifacial hyperplasia, revealing enlargement of the right maxilla only. A, Panoramic radiograph shows accelerated dental development limited to the right maxilla in a 5-year-old boy. B, A CT axial image with bone algorithm of the same patient demonstrating enlargement of the maxillary cuspid and first bicuspid (arrows) compared with the contralateral side. C, Three-dimensional CT scan shows the subtle bony enlargement of the right maxilla and the right cuspid.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis should consider hemifacial hypoplasia of the opposite side, arteriovenous aneurysms, hemangioma, and congenital lymphedema. Also, severe condylar hyperplasia that may involve half of the mandible should be considered (see Chapter 26). The presence of enlarged teeth together with rapid eruption of the dentition suggests hemifacial hyperplasia. Cases limited to one side of the maxilla must be differentiated from monostotic fibrous dysplasia and segmental odontomaxillary dysplasia, both of which have characteristic changes in the radiographic appearance of the alveolar bone not present in hemifacial hyperplasia.

Management

There have not been a significant number of cases of hemifacial hyperplasia reported with long-term follow-up to make definitive recommendations for treatment. Although most cases are isolated, a child with suspected hemifacial hyperplasia should be referred to a medical geneticist for diagnosis and early detection of one of several genetic syndromes that can be associated with this condition.

SEGMENTAL ODONTOMAXILLARY DYSPLASIA

Definition

Segmental odontomaxillary dysplasia (SOD) is a developmental abnormality of unknown etiology that affects the posterior alveolar process of one side of one maxilla, including the teeth and attached gingiva.

Clinical Features

The abnormality is always unilateral and results in enlargement of the alveolar process, gingiva, and teeth. Frequently teeth are missing (most commonly the premolars), and some of the teeth that remain are unerupted. Unilateral hypertrichosis and mild facial enlargement have been reported in a few cases. Most cases are detected in childhood because a parent notices the lack of tooth eruption or mild facial asymmetry or the dentist notices missing premolars radiographically.

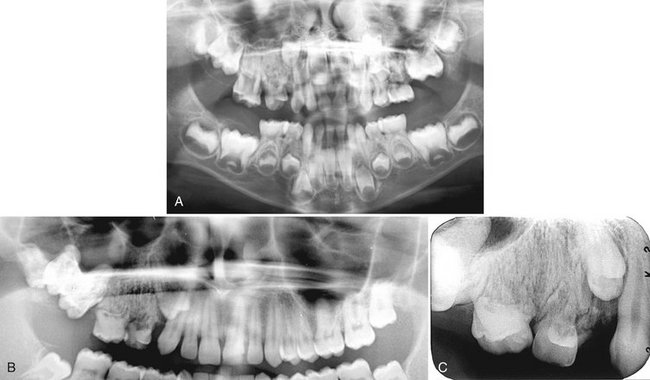

Radiographic Features

The density of the maxillary alveolar process is increased, with a greater number of thick trabeculae that appear to be aligned in a vertical orientation, having an appearance similar to that of some intraosseous hemangiomas (Fig. 30-9). The roots of the deciduous teeth are larger than on the unaffected side and usually are splayed in shape. The crowns of the deciduous teeth and sometimes the permanent teeth are enlarged. Enlargement of pulp chambers and irregular resorption of the roots of deciduous teeth also may be seen. The maxillary sinus does not pneumatize the alveolar process and thus appears smaller than on the contralateral side. There is often delayed eruption of the first and second permanent molars.

FIG. 30-9 A, A panoramic view of segmental odontomaxillary dysplasia. Note the large left maxillary deciduous molars compared with the right side and the lack of formation of the bicuspids, delayed eruption of the first molar, and the dense bone pattern of the left maxillary alveolar process. B and C, A second case demonstrating the coarse trabecular pattern of the right maxillary alveolar process and delayed eruption of the maxillary right first bicuspid and molars.

Differential Diagnosis

Other conditions that must be differentiated from SOD include segmental hemifacial hyperplasia, monostotic fibrous dysplasia, and regional odontodysplasia. Hemifacial hyperplasia is not associated with coarse vertically oriented trabeculae in the bone; monostotic fibrous dysplasia is not typically associated with missing teeth and, unlike SOD, will continue to show disproportionate growth of the affected side; and regional odontodysplasia typically is associated with ghost teeth and is not associated with expansion and alteration in trabecular pattern in the alveolar bone.

LINGUAL SALIVARY GLAND DEPRESSION

Lingual mandibular bone depression, developmental salivary gland defect, Stafne defect, Stafne bone cyst, static bone cavity, and latent bone cyst

Definition

Lingual mandibular bone depressions represent a group of concavities in the lingual surface of the mandible where the depression is lined with an intact outer cortex. Historically, they were referred to as pseudocysts because they resemble cysts radiographically, but they are not true cysts because no epithelial lining is present. The most common location is within the submandibular gland fossa and often close to the inferior border of the mandible. This lingual posterior variant (LP) of these depressions was first described by Stafne in 1942. This well-defined deep depression is thought to result from or be associated with growth of the salivary gland adjacent to the lingual surface of the mandible. Similar defects have also been described in the anterior region near the apical region of the bicuspids, associated with the sublingual glands (lingual anterior variant or LA) and very rarely on the medial surface of the ascending ramus, associated with the parotid gland (medial ramus variant or MR). In LP developmental bone defects investigated surgically, an aberrant lobe of the submandibular gland has been described to extend into the bony depression; however, CT imaging of some of these defects reveals fat tissue and no evidence of gland. The etiology remains unknown, but the condition is a developmental anomaly that has been documented to develop in patients as old as 30 years and as young as 11 years. These defects may continue to slowly grow in size.

Clinical Features

Although lingual mandibular bone depressions appear to be relatively rare, with an incidence of LP of about 0.10% to 0.48%, it is likely that many go unreported. LA incidence is even less at 0.009%. They are asymptomatic and next to impossible to palpate and, generally discovered only incidentally during radiographic examination of the area. In a recent review of a large number of cases, males predominated females at 6.1 : 1, with a peak incidence in the fifth and sixth decades.

Radiographic Features

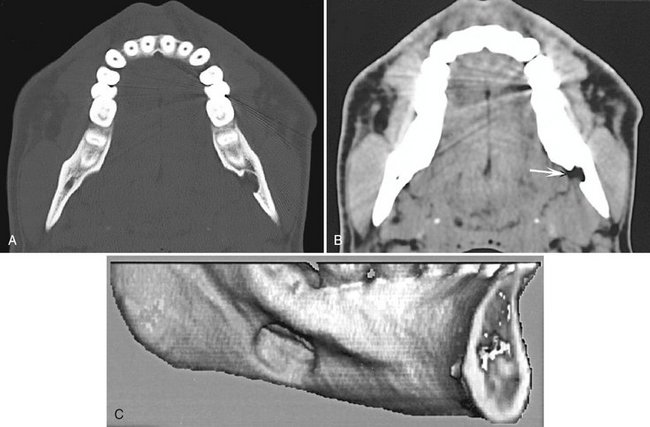

A lingual mandibular bone depression is a well-defined round, ovoid, or, occasionally, lobulated radiolucency that ranges in diameter from 1 to 3 cm (Fig. 30-10). The LP defect is located below the inferior alveolar nerve canal and anterior to the angle of mandible, in the region of the antegonial notch and submandibular gland fossa. Rare LA examples are located in the apical region of the mandibular premolars or cuspids and are related to the sublingual gland fossa, above the mylohyoid muscle. The margins of the radiolucent defect are well defined by a dense sclerotic radiopaque margin of variable width, which is usually thicker on the superior aspect. This appearance is the result of the x rays passing tangentially through the relatively thick walls of the depression. This cortical outline is often less distinct in the LA variant. The LP defect may involve the inferior border of the mandible. CT images reportedly reveal tissue of fat density within the defect (Fig. 30-11), or in some cases there is continuity of the tissue within the defect with the adjacent salivary gland.

FIG. 30-10 A, Lingual mandibular bone depressions of the posterior variant usually are seen as sharply defined radiolucencies beneath the mandibular canal in the region of the submandibular gland fossa. These defects can erode the inferior border of the mandible. B, An unusual variant with a superior position above the inferior alveolar canal. C, An anterior variant within the sublingual gland fossa.

FIG. 30-11 CT scans of lingual mandibular bone depressions, posterior variant. A and B, Axial bone and soft tissue windows of the same case. Note the well-defined defect extending from the medial surface of the mandible and the corresponding soft tissue image, which shows radiolucent tissue within the defect that has the density equivalent of fat tissue (arrow). C, A three-dimensional, reformatted CT image revealing a defect extending from the medial surface of the mandible.

Differential Diagnosis

The appearance and location of the radiographic image of this developmental bone defect are characteristic and easily identified. Lingual mandibular bone depressions can be readily differentiated from odontogenic lesions such as cysts because the epicenter of odontogenic lesions is located above the inferior alveolar canal. However, when the defect is related to the sublingual gland and appears above the canal, odontogenic lesions should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Management

Recognition of the lesion should preclude any treatment or surgical exploration or the need for advanced imaging such as CT. The defect may increase in size with time. There are rare reports of salivary gland neoplasms developing in the soft tissue within the defect. Destruction of the well-defined cortex of the defect may indicate the presence of a neoplasm.

FOCAL OSTEOPOROTIC BONE MARROW

Definition

Focal osteoporotic bone marrow is a radiologic term indicating the presence of radiolucent defects within the cancellous portion of the jaws. Histologic examination reveals normal areas of hematopoietic or fatty marrow. The etiology is unknown but has been postulated to be (1) bone marrow hyperplasia, (2) persistent embryologic marrow remnants, or (3) sites of abnormal healing after extraction, trauma, or local inflammation. This entity is a variation of normal anatomy.

Clinical Features

Focal osteoporotic bone marrow defects are usually clinically asymptomatic and are commonly an incidental radiographic finding. These marrow spaces are more common in middle-aged women.

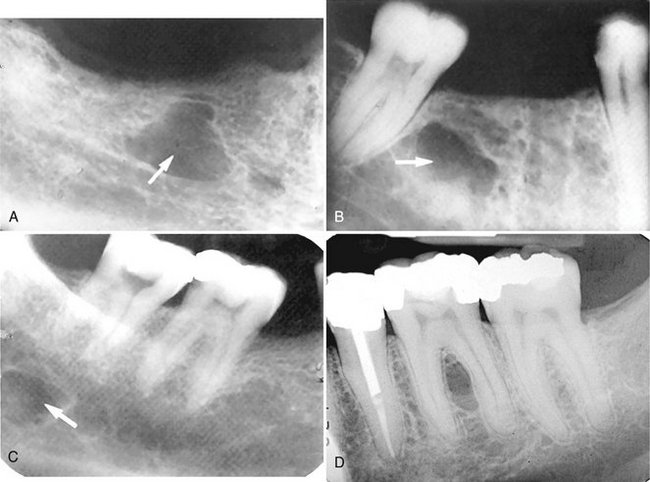

Radiographic Features

A common site for focal osteoporotic bone marrow is the mandibular molar-premolar region. Other sites include the maxillary tuberosity region, mandibular retromolar area, edentulous locations, occasionally the furcation region of mandibular molars, and rarely near the apex of teeth. The radiographic appearance of focal osteoporotic bone marrow space is quite variable. The internal aspect is radiolucent because of the presence of fewer trabeculae in comparison with the surrounding bone. The periphery may be ill defined and blending or may appear to be corticated. The immediate surrounding bone is normal without any sign of a bone reaction (Fig. 30-12).

FIG. 30-12 A through C, Focal osteoporotic bone marrow defect, seen as a radiolucency (arrow). A few internal trabeculae may be present, and the periphery varies from well defined to ill defined. D, An example located in the furcation of a mandibular first molar. The periodontal ligament space and lamina dura are intact.

Differential Diagnosis

A small simple bone cyst may have a similar appearance because there is usually no bone reaction at the periphery of a simple bone cyst. When osteoporotic bone marrow occurs in the furcation region or at the apex of a tooth, the differential diagnosis includes the presence of an inflammatory lesion. If the area is normal bone marrow, the lamina dura should be intact. Very early inflammatory lesions that have not yet stimulated a visible osteoblastic response may appear similar.

Management

No treatment is required for the osteoporotic bone marrow space. Prior radiographs of the region should always be obtained if available. When doubt exists about the true nature of the radiolucency, a longitudinal study with films at 3-month intervals may be prescribed. The marrow space should not increase in size.

Cohen, MM, Jr., McLean, RE. Craniosynostosis: diagnosis, evaluation, and management, ed 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Gorlin, RJ, Cohen, MM, Jr., Hennekam, RCM. Syndromes of the head and neck, ed 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

Neville, BW, Damm, DD, Allen, CM, et al. Oral and maxillofacial pathology, ed 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

Worth, HM. Principles and practice of oral radiologic interpretation. Chicago: Year Book; 1963.

Habel, A, Sell, D, Mars, M. Management of cleft lip and palate. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:360–366.

Harris, EF, Hullings, JG. Delayed dental development in children with isolated cleft lip and palate. Arch Oral Biol. 1990;35:469–473.

Hibbert, SA, Field, JK. Molecular basis of familial cleft lip and palate. Oral Dis. 1996;2:238–241.

Honein, MA, Rasmussen, SA, Reefhuis, J, et al. Maternal and environmental tobacco smoke exposure and the risk of orofacial clefts. Epidemiology. 2007;18:226–233.

Shapira, Y, Lubit, E, Kuftinec, MM. Hypodontia in children with various types of clefts. Angle Orthod. 2000;70:16–21.

Wyszynski, DF, Beaty, TH, Maestri, NE. Genetics of nonsyndromic oral clefts revisited. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1996;33:406–417.

Murdoch-Kinch, CA, Bixler, D, Ward, RE. Cephalometric analysis of families with dominantly inherited Crouzon syndrome: an aid to diagnosis in family studies. Am J Med Genet. 1998;77:405–411.

Tuite, GF, Evanson, J, Chong, WK, et al. The beaten copper cranium: a correlation between intracranial pressure, cranial radiographs, and computed tomographic scans in children with craniosynostosis. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:691–699.

Maruko, E, Hayes, C, Evans, CA, et al. Hypodontia in hemifacial microsomia. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2001;38:15–19.

Monahan, R, Seder, K, Patel, P, et al. Hemifacial microsomia: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:1402–1408.

Sze, RW, Paladin, AM, Lee, S, et al. Hemifacial microsomia in pediatric patients: asymmetric abnormal development of the first and second branchial arches. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1523–1530.

Herman, TE, Siegel, MJ. Special imaging casebook: Treacher Collins syndrome. J Perinatol. 1996;16:413–415.

Posnick, JC. Treacher Collins syndrome: perspectives in evaluation and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:1120–1133.

Golan, I, Baumert, U, Hrala, BP, et al. Dentomaxillofacial variability of cleidocranial dysplasia: clinicoradiological presentation and systematic review. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2003;32:347–354.

McGuire, TP, Gomes, PP, Lam, DK, et al. Cranioplasty for midline metopic suture defects in adults with cleidocranial dysplasia, Oral Surg Oral Med. Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:175–179.

Seow, WK, Hertzberg, J. Dental development and molar root length in children with cleidocranial dysplasia. Pediatr Dent. 1995;17:101–105.

Yoshida, T, Kanegane, H, Osata, M, et al. Functional analysis of RUNX2 mutations in Japanese patients with cleidocranial dysplasia demonstrates novel genotype-phenotype correlations. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:724–738.

Fraumeni, JF, Jr., Geiser, CF, Manning, MD, et al. Wilms’ tumor and congenital hemihypertrophy: report of five new cases and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1967;40:886–899.

Hoyme, HE, Seaver, LH, Procopio, F, et al. Isolated hemihyperplasia (hemihypertrophy): report of a prospective multicenter study of the incidence of neoplasia and review. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:274–278.

Kogon, SL, Jarvis, AM, Daley, TD, et al. Hemifacial hypertrophy affecting the maxillary dentition: report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:549–553.

SEGMENTAL ODONTOMAXILLARY DYSPLASIA

Danforth, RA, Melrose, RJ, Abrams, AM, et al. Segmental odontomaxillary dysplasia: report of eight cases and comparison with hemimaxillofacial dysplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70:81–85.

Miles, DA, Lovas, JL, Cohen, MM, Jr. Hemimaxillofacial dysplasia: a newly recognized disorder of facial asymmetry, hypertrichosis of the facial skin, unilateral enlargement of the maxilla, and hypoplastic teeth in two patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64:445–448.

Packota, GV, Pharaoh, MJ, Petrikowski, CG. Radiographic features of segmental odontomaxillary dysplasia: a study of 12 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82:577–588.

LINGUAL MANDIBULAR BONE DEPRESSION

Parvizi, F, Rout, PG. An ossifying fibroma presenting as Stafne’s idiopathic bone cavity. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1997;26:361–363.

Philipsen, HP, Takata, T, Reichart, PA, et al. Lingual and buccal mandibular bone depressions: a review based on 583 cases from a world-wide literature survey, including 69 new cases from Japan. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:281–290.

FOCAL OSTEOPOROTIC BONE MARROW

Schneider, LC, Mesa, ML, Fraenkel, D. Osteoporotic bone marrow defect: radiographic features and pathogenic factors. Oral Surg. 1988;65:127–129.

Standish, SM, Shafer, WG. Focal osteoporotic bone marrow defects of the jaws. J Oral Surg Anesth Hosp Dent Serv. 1962;20:123–128.