Ethics in Research

Nursing research requires not only expertise and diligence but also honesty and integrity. Conducting research ethically starts with the identification of the study topic and continues through the publication of the study. Over the years, ethical codes and regulations have been developed to provide guidelines for (1) the selection of the study purpose, design, and subjects; (2) the collection and analysis of data; (3) the interpretation of results; and (4) the presentation and publication of the study. In 2003, an important regulation titled the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was enacted to protect the privacy of an individual’s health information. HIPAA has had an important impact on researchers and institutional review boards (IRBs), who review health care research for conduct in a variety of settings. This chapter provides an overview of this act and the other U.S. and international regulations that have been developed to promote ethical conduct in research worldwide.

An ethical problem that has received increasing attention since the 1980s is research misconduct. Misconduct has occurred during the performance, reporting, and publication of research, and the Office of Research Integrity (ORI) has investigated a number of research institutions in the United States for fraud (ORI, 2007, June 20). Many disciplines, including nursing, have had episodes of scientific misconduct that have affected the quality of research evidence generated.

Ethical research is essential to generate a sound evidence-based practice for nursing, but what does the ethical conduct of research involve? This is a question that has been debated for many years by researchers, politicians, philosophers, lawyers, and even research subjects. The debate continues, probably because of the complexity of human rights issues; the focus of research in new, challenging arenas of technology and genetics; the complex ethical codes and regulations governing research; and the various interpretations of these codes and regulations. Even though the phenomenon of the ethical conduct in research defies precise delineation, the historical events, ethical codes, and regulations presented in this chapter provide guidance for nurse researchers. The chapter also discusses the actions essential for conducting research ethically: (1) protecting the rights of human subjects, (2) balancing benefits and risks in a study, (3) obtaining informed consent from subjects, and (4) submitting a research proposal for institutional review. Current ethical issues related to scientific misconduct and the use of animals in research conclude the chapter.

HISTORICAL EVENTS AFFECTING THE DEVELOPMENT OF ETHICAL CODES AND REGULATIONS

The ethical conduct of research has been a focus since the 1940s because of the mistreatment of human subjects in selected studies. Four experimental projects have been highly publicized for their unethical treatment of subjects: (1) Nazi medical experiments, (2) the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, (3) the Willowbrook study, and (4) the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital study. Although these were biomedical studies and the primary investigators were physicians, there is evidence that nurses were aware of the research, identified potential research subjects, delivered treatments to the subjects, and served as data collectors in these projects. The four projects demonstrate the importance of ethical conduct for anyone reviewing, participating in, and conducting nursing or biomedical research. These four projects and other incidences of unethical treatment of subjects and scientific misconduct in the development, implementation, and reporting of research have influenced the formulation of ethical codes and regulations to direct research today. In addition, the concern for patient privacy with the electronic storage and exchange of health information has resulted in HIPAA privacy regulations (Olsen, 2003).

Nazi Medical Experiments

From 1933 to 1945, the Third Reich in Europe implemented atrocious, unethical activities (Steinfels & Levine, 1976). The programs of the Nazi regime consisted of sterilization, euthanasia, and numerous medical experiments to produce a population of racially pure Germans, or Aryans, who the Nazis maintained were destined to rule the world. The Nazis encouraged population growth among the Aryans (“good Nazis”) and sterilized people they regarded as racial enemies, such as the Jews. They also practiced what they called “euthanasia,” which involved killing various groups of people whom they considered racially impure, such as the insane, deformed, and senile. In addition, numerous medical experiments were conducted on prisoners of war, as well as racially “valueless” persons who had been confined to concentration camps.

The medical experiments involved exposing subjects to high altitudes, freezing temperatures, malaria, poisons, spotted fever (typhus), and untested drugs and operations, usually without any anesthesia (Steinfels & Levine, 1976). For example, in the hypothermia studies, subjects were immersed in bath temperatures ranging from 2° to 12° C. The researchers noted that “immersion in water 5° C is tolerated by clothed men for 40 to 60 minutes, whereas raising the water temperature to 15° C increases the period of tolerance to four to five hours” (Berger, 1990, p. 1436). These medical experiments were conducted to generate knowledge about human beings but the end result often was to destroy certain groups of people. Extensive examination of the records from some of these studies showed that they were poorly designed and conducted. Thus, they generated little if any useful scientific knowledge.

The Nazi experiments violated numerous rights of human research subjects. The selection of subjects was racially based, demonstrating an unfair selection process. The subjects also had no opportunity to refuse participation; they were prisoners who were coerced or forced to participate. Subjects were frequently killed during the experiments or sustained permanent physical, mental, and social damage as a result (Levine, 1986; Steinfels & Levine, 1976). These studies were not conducted by a few isolated scientists and physicians; they were “the product of coordinated policymaking and planning at high governmental, military, and Nazi Party levels, conducted as an integral part of the total war effort” (Nuremberg Code, 1986, p. 425).

Nuremberg Code

The people involved in the Nazi experiments were brought to trial before the Nuremberg Tribunals, which publicized these unethical activities. The mistreatment of human subjects in these studies led to the development of the Nuremberg Code in 1949. This code contains guidelines for (1) subjects’ voluntary consent to participate in research; (2) the right of subjects to withdraw from studies; (3) protection of subjects from physical and mental suffering, injury, disability, and death during studies; and (4) the balance of benefits and risks in a study (Table 9-1). The Nuremberg Code was formulated mainly to direct the conduct of biomedical research; however, the rules it contains are essential to research in other sciences, such as nursing, psychology, and sociology. This code was developed to promote the ethical conduct of research in all countries and can be reviewed online at http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/guidelines/nuremberg.html.

TABLE 9-1

1. The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.

2. The experiment should be such as to yield fruitful results for the good of society, unprocurable by other methods or means of study, and not random and unnecessary in nature.

3. The experiment should be so designed and based on the results of animal experimentation and knowledge of the natural history of the disease or other problem under study that the anticipated results will justify the performance of the experiment.

4. The experiment should be so conducted as to avoid all unnecessary physical and mental suffering and injury.

5. No experiment should be conducted where there is a priori reason to believe that death or disabling injury will occur, except, perhaps, in those experiments where the experimental physicians also serve as subjects.

6. The degree of risk to be taken should never exceed that determined by the humanitarian importance of the problem to be solved by the experiment.

7. Proper preparations should be made and adequate facilities provided to protect the experimental subject against even remote possibilities of injury, disability, or death.

8. The experiment should be conducted only by scientifically qualified persons. The highest degree of skill and care should be required through all stages of the experiment of those who conduct or engage in the experiment.

9. During the course of the experiment the human subject should be at liberty to bring the experiment to an end if he has reached the physical or mental state where continuation of the experiment seems to him to be impossible.

10. During the course of the experiment the scientist in charge must be prepared to terminate the experiment at any stage, if he has probable cause to believe, in the exercise of the good faith, superior skill, and careful judgment required of him, that a continuation of the experiment is likely to result in injury, disability, or death to the experimental subject.

From “The Nuremberg Code,” in Ethics and Regulation of Clinical Research (2nd ed., pp. 425–426), edited by R.J. Levine, 1986, Baltimore–Munich: Urban & Schwarzenberg.

Declaration of Helsinki

The Nuremberg Code provided the basis for the development of the Declaration of Helsinki, which was adopted in 1964 and amended in 1975, 1983, 1989, 1996, 2000, and 2002 by the World Medical Association; it can be viewed online at www.rotrf.org/information/Helsinki_declaration.pdf. The Declaration of Helsinki differentiated therapeutic research from nontherapeutic research. Therapeutic research gives the patient an opportunity to receive an experimental treatment that might have beneficial results. Nontherapeutic research is conducted to generate knowledge for a discipline, and the results from the study might benefit future patients but will probably not benefit those acting as research subjects.

The Declaration of Helsinki requires that (1) greater care be exercised to protect subjects from harm in nontherapeutic research; (2) there be a strong, independent justification for exposing a healthy volunteer to risk of harm just to gain new scientific information; (3) investigators must protect the life, health, privacy, and dignity of research subjects; and (4) extreme care must be taken in making use of placebo-controlled trial and used only in the absence of existing proven therapy (World Medical Association General Assembly, 2002). Thus, this legal document provides an ethical basis for the clinical trials and other research conducted today in the United States and internationally. Clinical trials must focus on improving diagnostic, therapeutic, and prophylactic procedures for patients with selected diseases without exposing subjects to any additional risk of serious or irreversible harm. Most institutions worldwide in which clinical research is conducted have adopted the Declaration of Helsinki. However, neither this document nor the Nuremberg Code has prevented some investigators from conducting unethical research (Beecher, 1966; Nelson-Marten & Rich, 1999; ORI, 2004).

Tuskegee Syphilis Study

In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service (U.S. PHS) initiated a study of syphilis in black men in the small, rural town of Tuskegee, Alabama (Brandt, 1978; Rothman, 1982). The study, which continued for 40 years, was conducted to determine the natural course of syphilis in the adult black male. The research subjects were organized into two groups: one group consisted of 400 men who had untreated syphilis and the other consisted of a control group of 200 men without syphilis. Many of the subjects who consented to participate in the study were not informed about the purpose and procedures of the research. Some individuals were unaware that they were subjects in a study.

By 1936, it was apparent that the men with syphilis developed more complications than the control group. Ten years later, the death rate of the group with syphilis was twice as high as that for the control group. The subjects were examined periodically but were not treated for syphilis, even after penicillin was determined to be an effective treatment for the disease in the 1940s (Levine, 1986). Information about an effective treatment for syphilis was withheld from the subjects, and deliberate steps were taken to keep them from receiving treatment (Brandt, 1978).

Published reports of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study first started appearing in 1936, and additional papers were published every 4 to 6 years. No effort was made to stop the study; in fact, in 1969, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) decided that it should continue. Numerous individuals were involved in conducting this study, including

three generations of doctors serving in the venereal disease division of the U.S. PHS, numerous officials at the Tuskegee Institute and its affiliated hospital, hundreds of doctors in the Macon County and Alabama medical societies, and numerous foundation officials at the Rosenwald Fund and the Milbank Memorial Fund. (Rothman, 1982, p. 5)

In 1972, an account of the study published in the Washington Star sparked public outrage. Only then did the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW) stop the study. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study was investigated and found to be ethically unjustified, but its racial implications were never addressed (Brandt, 1978). There are still many unanswered questions about this study, such as where were the checks and balances in the government and health care systems that should have prevented this unethical study from continuing for 40 years and why was public outrage the only effective means of halting the study?

Willowbrook Study

From the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, Dr. Krugman at Willowbrook, an institution for the mentally retarded, conducted research on hepatitis (Rothman, 1982). The subjects, all children, were “deliberately infected with the hepatitis virus; early subjects were fed extracts of stool from infected individuals and later subjects received injections of more purified virus preparations” (Levine, 1986, p. 70). During the 20-year study, Willowbrook closed its doors to new inmates because of overcrowded conditions. However, the research ward continued to admit new inmates. To gain their child’s admission to the institution, the parents were forced to give permission for the child to be a subject in the study.

From the late 1950s to early 1970s, Krugman’s research team published several articles describing the study protocol and findings. Beecher (1966) cited the Willowbrook study as an example of unethical research. The investigators defended injecting the children with the virus by citing their own belief that most of the children would have acquired the infection after admission to the institution. The investigators also stressed the benefits the subjects received, which were a cleaner environment, better supervision, and a higher nurse-patient ratio on the research ward (Rothman, 1982). Despite the controversy, this unethical study continued until the early 1970s.

Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital Study

Another highly publicized example of unethical research was a study conducted at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in the 1960s. Its purpose was to determine the patients’ rejection responses to live cancer cells. Twenty-two patients were injected with a suspension containing live cancer cells that had been generated from human cancer tissue (Hershey & Miller, 1976; Levine, 1986).

The patients were not informed that they were taking part in research or that the injections they received were live cancer cells. In addition, the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital Institutional Review Board never reviewed the study; even the physicians caring for the patients were unaware that the study was being conducted. The physician directing the research was an employee of the Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, and there was no indication that this institution had reviewed the research project (Hershey & Miller, 1976). The research project had the potential to cause the human subjects serious or irreversible harm and possibly death.

Other Unethical Studies

In 1966, Henry Beecher published a now classic article describing 22 of the 50 examples of unethical or questionably ethical studies that he had identified in the published literature. The examples, which included the Willowbrook and Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital studies, indicated a variety of ethical problems that were relatively widespread. Consent was mentioned in only 2 of the 50 studies, and many of the investigators had unnecessarily risked the health and lives of their subjects. Beecher (1966, p. 1356) believed that many of the abuses in the research were due to “thoughtlessness and carelessness, not a willful disregard of patients’ rights.” These studies reinforce the importance of conscientious institutional review and ethical researcher conduct.

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Regulations

The continued conduct of harmful, unethical research made additional controls necessary. In 1973, the DHEW published its first set of regulations intended to protect human subjects. By May 1974, clinical researchers were presented with strict regulations for research involving humans, with additional regulations to protect persons having limited capacities to consent, such as the ill, mentally impaired, and dying (Levine, 1986).

In the 1970s, researchers went from a few vague regulations to almost overwhelming guidelines. All research involving human subjects had to undergo full institutional review, even nursing studies that involved minimal or no risks to the human subjects. Institutional review improved the protection of human subjects; however, reviewing all studies, without regard for the degree of risk involved, overwhelmed the review process and greatly prolonged the time required for a study to be approved (Levine, 1986).

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research

Because the DHEW regulations far from resolved the issue of protecting human subjects in research, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1978) was formed. This commission was established by the National Research Act (Public Law 93-348) passed in 1974. The goals of the commission were (1) to identify the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of biomedical and behavioral research involving human subjects and (2) to develop guidelines based on these principles.

The commission developed The Belmont Report, which identified three ethical principles as relevant to research involving human subjects: the principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. The principle of respect for persons holds that persons have the right to self-determination and the freedom to participate or not participate in research. The principle of beneficence requires the researcher to do good and “above all, do no harm.” The principle of justice holds that human subjects should be treated fairly. The ethical principles in this report continue to influence the conduct of ethical research in the United States and internationally. This commission developed ethical research guidelines based on these three principles, made recommendations to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (U.S. DHHS), and was dissolved in 1978 (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1978).

In response to the commission’s recommendations, in 1981 the U.S. DHHS developed a set of federal regulations to protect human research subjects, and these regulations were revised over the years (U.S. DHHS, 1981, 1983, 1991, 2001, 2005). The most current 2005 regulations are part of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 45, Part 46, Protection of Human Subjects. These regulations are interpreted by the Office for Human Research Protection (OHRP), an agency within U.S. DHHS, whose functions are described online at www.hhs.gov/ohrp. These regulations provide direction for (1) the protection of human subjects in research, with additional protection for pregnant women, human fetuses, neonates, children, and prisoners; (2) the documentation of informed consent; and (3) the implementation of the institutional review board process (U.S. DHHS, 2005). These regulations apply to all research involving human subjects in the following areas: (1) studies conducted, supported, or otherwise subject to regulations by any federal department or agency; (2) research conducted in educational settings; (3) research involving the use of educational tests, survey procedures, interview procedures, or observation; and (4) research involving the collection or study of existing data, documents, records, pathological specimens, or diagnostic specimens.

Most of the biomedical and behavioral research conducted in the United States is governed by the U.S. DHHS Protection of Human Subjects Regulations (U.S. DHHS, 2005) or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (see www.fda.gov/oc/gcp). The FDA, within the U.S. DHHS, manages the CFR Title 21, Food and Drugs, Part 50, Protection of Human Subjects, and Part 56, Institutional Review Boards. The FDA has additional human subject protection regulations that apply to clinical investigations involving products regulated by the FDA under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and research that supports applications for research or marketing permits for these products. Thus, these regulations apply to studies of drugs for humans, medical devices for human use, biological products for human use, human dietary supplements, and electronic products and can be viewed online at www.fda.gov/oc/gcp/regulations.html. The physician and nurse researchers conducting clinical trials to generate new drugs and refine existing drug treatments must comply with these FDA regulations. These regulations focus on the protection of human subjects’ rights, informed consent (FDA, 2006b), and institutional review boards (FDA, 2006b), with content that is consistent with Title 45, Public Welfare, Part 46, Protection of Human Subjects (U.S. DHHS, 2005).

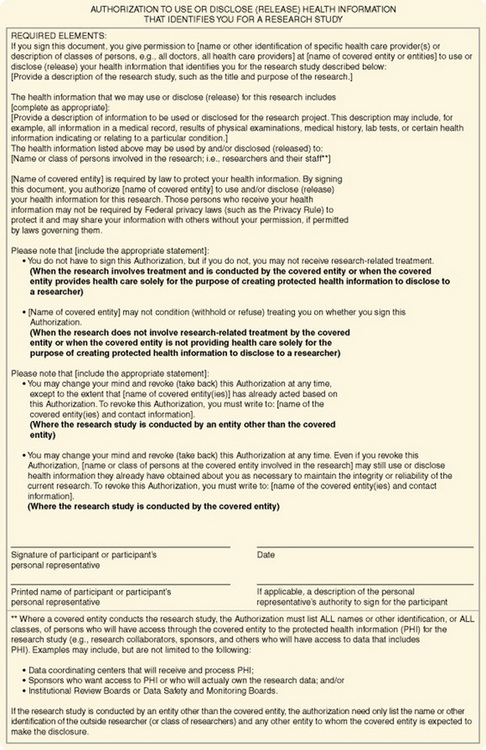

The U.S. DHHS and FDA regulations provide guidelines to protect subjects in federally and privately funded research by ensuring that their privacy and the confidentiality of the information obtained through research. However, with the advent of electronic access and transfer, the public has become concerned about the potential abuses of the health information of individuals in all circumstances, including research projects. Thus, Public Law 104-191, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), was enacted in 1996 and implemented in 2003 to protect an individual’s health information. The U.S. DHHS developed regulations titled the Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information, and compliance with these regulations is known as the Privacy Rule (U.S. DHHS, 2002, 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164). The HIPAA Privacy Rule established the category of protected health information (PHI), which allows covered entities, such as health plans, health care clearinghouses, and health care providers that transmit health information, to use or disclose PHI to others only in certain situations. These situations are discussed later in this chapter.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule affects not only the health care environment but also the research conducted in this environment. An individual must provide his or her signed permission, or authorization, before his or her PHI can be used or disclosed for research purposes. Researchers must modify their current studies and develop their new research projects to comply with the HIPAA Privacy Rule. The U.S. DHHS developed a website, “HIPAA Privacy Rule: Information for Researchers,” to address the impact of this rule on the informed consent and institutional review board processes in research and to answer common questions about the HIPAA (see http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov). The full impact of the privacy rule on the protection of individuals’ privacy and on the conduct of research is yet to be determined (Conner, Smaldone, Bratts, & Stone, 2003; Olsen, 2003); however, you can view the privacy rule enforcement highlights online at www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/enforcement.

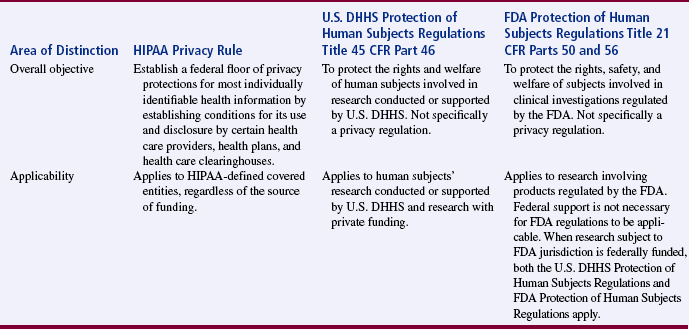

In summary, Table 9-2 was developed to clarify the overall objectives and applicability of the HIPAA Privacy Rule, U.S. DHHS Protection of Human Subjects Regulations Title 45 CFR Part 46, and FDA Protection of Human Subjects Regulations Title 21 CFR Parts 50 and 56 (U.S. DHHS, 2007, February 2, b). The specifics of these regulations are discussed later in this chapter in the sections on protecting human rights, obtaining informed consent, and institutional review.

TABLE 9-2

Clarification of the Focus of Federal Regulations and Impact on Research

From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2007, February 2, b). How do other privacy protections interact with the privacy rule? HIPAA Privacy Rule: Information for researchers. Retrieved October 1, 2007, from http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/pr_05.asp.

PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS

Human rights are claims and demands that have been justified in the eyes of an individual or by the consensus of a group of individuals. Having rights is necessary for the self-respect, dignity, and health of an individual (Sasson & Nelson, 1971). Researchers and reviewers of research have an ethical responsibility to recognize and protect the rights of human research subjects. The human rights that require protection in research are (1) the right to self-determination, (2) the right to privacy, (3) the right to anonymity and confidentiality, (4) the right to fair treatment, and (5) the right to protection from discomfort and harm (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2001; American Psychological Association [APA], 2002). Nurses in other countries have developed similar codes of ethics to protect the rights of their patients and to promote ethical conduct in research (Lin et al., 2007).

Right to Self-Determination

The right to self-determination is based on the ethical principle of respect for persons. This principle holds that because humans are capable of self-determination, or controlling their own destiny, they should be treated as autonomous agents who have the freedom to conduct their lives as they choose without external controls. As a researcher, you treat prospective subjects as autonomous agents by informing them about a proposed study and allowing them to voluntarily choose to participate or not. In addition, subjects have the right to withdraw from a study at any time without a penalty (Levine, 1986). Conducting research ethically requires that research subjects’ right to self-determination not be violated and that persons with diminished autonomy have additional protection during the conduct of studies.

Preventing Violation of Research Subjects’ Right to Self-Determination

A subject’s right to self-determination can be violated through the use of (1) coercion, (2) covert data collection, and (3) deception. Coercion occurs when, one person intentionally presents another with an overt threat of harm or the lure of excessive reward to obtain his or her compliance (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1978). Some subjects are coerced to participate in research because they fear that they will suffer harm or discomfort if they do not participate. For example, some patients believe that their medical or nursing care will be negatively affected if they do not agree to be research subjects. Sometimes students feel forced to participate in research to protect their grades or prevent negative relationships with the faculty conducting the research. Other subjects are coerced to participate in studies because they believe that they cannot refuse the excessive rewards offered, such as large sums of money, specialized health care, special privileges, and jobs. Most nursing studies do not offer excessive rewards to subjects for participating. A few nursing studies have included a small financial reward of $10 to $20 or support for transportation to increase participation, but this usually would not be considered coercive.

An individual’s right to self-determination can also be violated if he or she becomes a research subject without realizing it. Some researchers have exposed persons to experimental treatments without their knowledge, a prime example being the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital study. Most of the patients and their physicians were unaware of the study. The subjects were informed that they were receiving an injection of cells, but the word cancer was omitted (Beecher, 1966). With covert data collection, subjects are unaware that research data are being collected because the investigator develops “descriptions of natural phenomena using information that is provided as a matter of normal activity” (Reynolds, 1979, p. 76). This type of data collection has more commonly been used by psychologists to describe human behavior in a variety of situations, but it has also been used by nursing and other disciplines (APA, 2002). Qualitative researchers have debated this issue, and some believe that certain group and individual behaviors are unobservable within the normal ethical range of research activities, such as the actions of cults or the aggressive or violent behaviors of individuals (Grbich, 1999). However, covert data collection is considered unethical when research deals with sensitive aspects of an individual’s behavior, such as illegal conduct, sexual behavior, or drug use (U.S. DHHS, 2005). With the HIPAA Privacy Rule (U.S. DHHS, 2002), the use of any type of covert data collection would be questionable and illegal if PHI data were being used or disclosed.

The use of deception in research can also violate a subject’s right to self-determination. Deception is the actual misinforming of subjects for research purposes (Kelman, 1967). A classic example of deception is the Milgram (1963) study, in which the subjects thought they were administering electric shocks to another person. The subjects were unaware that the person was really a professional actor who pretended to feel the shocks. Some subjects experienced severe mental tension, almost to the point of collapse, because of their participation in this study. The use of deception still occurs in some health care, social, and psychological investigations, but it is a controversial research activity (Grbich, 1999). If deception is to be used in a study, you must determine that there is no other way to get the essential research data needed and that the subjects will not be harmed. In addition, the subjects must be informed of the deception once the study is completed, and you must provide them with full disclosure of the study that was conducted (U.S. DHHS, 2005).

Protecting Persons with Diminished Autonomy

Some persons have diminished autonomy or are vulnerable and less advantaged because of legal or mental incompetence, terminal illness, or confinement to an institution (Levine, 1986). These persons require additional protection of their right to self-determination, because they have a decreased ability, or an inability, to give informed consent. In addition, these persons are vulnerable to coercion and deception. The U.S. DHHS (2005) has identified certain vulnerable groups of individuals, including pregnant women, human fetuses, neonates, children, mentally incompetent persons, and prisoners, who require additional protection in the conduct of research. Researchers need to justify their use of subjects with diminished autonomy in a study, and the need for justification increases as the subjects’ risk and vulnerability increase. However, in many situations, the knowledge needed to provide evidence-based care to these vulnerable populations can be gained only by studying them.

Legally and Mentally Incompetent Subjects: Neonates and children (minors), the mentally impaired, and unconscious patients are legally or mentally incompetent to give informed consent. These individuals lack the ability to comprehend information about a study and to make decisions regarding participation in or withdrawal from the study. Their vulnerability ranges from minimal to absolute. The use of persons with diminished autonomy as research subjects is more acceptable if (1) the research is therapeutic so that the subjects have the potential to benefit directly from the experimental process, (2) the researcher is willing to use both vulnerable and nonvulnerable individuals as subjects, (3) preclinical and clinical studies have been conducted and provide data for assessing potential risks to subjects, and (4) the risk is minimized and the consent process is strictly followed to secure the rights of the prospective subjects (Levine, 1986; U.S. DHHS, 2005).

Neonates: A neonate is defined as a newborn and is identified as either viable or nonviable on delivery. Viable neonates are able to survive after delivery, if given the benefit of available medical therapy, and can independently maintain a heartbeat and respiration. “A nonviable neonate means that a newborn after delivery, although living, is not viable” (U.S. DHHS, 2005, 45 CFR Section 46.202). Neonates are extremely vulnerable and require extra protection to determine their involvement in research. However, your research may involve viable neonates, neonates of uncertain viability, and nonviable neonates if the following conditions are met: (1) your study is scientifically appropriate and the preclinical and clinical studies have been conducted and provide data for assessing the potential risks to the neonates; (2) your study provides important biomedical knowledge, which cannot be obtained by other means and will not add risk to the neonate; (3) your research has the potential to enhance the probability of survival of the neonate; (4) both parents are fully informed about your research during the consent process; and (5) your research team will have no part in determining the viability of the neonate. In addition, for the “nonviable neonates, the vital functions of the neonate should not be artificially maintained because of the research and the research should not terminate the heartbeat or respiration of the neonate” (U.S. DHHS, 2005, 45 CFR Section 46.205).

Children: The unique vulnerability of children makes the decision to include them as research subjects particularly important. To safeguard their interests and protect them from harm, special ethical and regulatory considerations have been put in place for research involving children (Title 45, CFR 46 Subpart D). However, the laws defining the minor status of a child are statutory and vary from state to state. Often a child’s competency to consent is governed by age, with incompetence being nonrefutable up to age 7 years (Broome, 1999; Thompson, 1987). Thus, a child younger than 7 years is not believed to be mature enough to assent or consent to research. Developmentally by age 7, a child is capable of concrete operations of thought and can give meaningful assent to participate as a subject in studies (Thompson, 1987). With advancing age and maturity, a child should have a stronger role in the consent process.

To obtain informed consent, federal regulations require both “soliciting the assent of the children (when capable) and the permission of their parents or guardians” (U.S. DHHS, 2005, 45 CFR Section 46.408). “Assent means a child’s affirmative agreement to participate in research. Permission to participate in a study means the agreement of parents or guardian to the participation of their child or ward in research” (U.S. DHHS, 2005, 45 CFR Section 46.402). If a child does not assent to participate in the study, he or she should not be included as a subject even if parental permission is obtained.

Using children as research subjects is also influenced by the therapeutic nature of the research and the risks versus the benefits. Thompson (1987) developed a guide for obtaining informed consent that is based on the child’s level of competence, the therapeutic nature of the research, and the risks versus the benefits (Table 9-3). Children who are experiencing a developmental delay, cognitive deficit, emotional disorder, or physical illness must be considered individually (Broome, 1999; Broome & Stieglitz, 1992).

TABLE 9-3

Guide to Obtaining Informed Consent Based on the Relationship between a Child’s Level of Competence, the Therapeutic Nature of the Research, and Risk versus Benefit

MMR, More than minimal risk; MR, minimal risk; LB, low benefit; HB, high benefit.

*A parent’s refusal can be superseded by the principle that a parent has no power to forbid the saving of a child’s life.

†Children making “deliberate objection” would be precluded from participation by most researchers.

‡In cases not involving the privacy rights of a “mature minor.”

§In cases involving the privacy rights of a “mature minor.”

From Thompson, P. J. (1987). Protection of the rights of children as subjects for research. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 2(6): 397.

A child 7 years or older with normal cognitive development can provide assent or dissent to participation in a study, and the process for obtaining the assent should be included in the research proposal. In the assenting process, the child must be given developmentally appropriate information on the study purpose, expectations, and the benefit-risk ratio (discussed later). Videotapes, written materials, demonstrations, diagrams, role-modeling, and peer discussions are methods for communicating study information. The child also needs an opportunity to sign an assent form and to have a copy of this form. An example assent form is presented in Table 9-4. During the study, you must give the child the opportunity to ask questions and to withdraw from the study if he or she desires (Broome, 1999). Assent becomes more complex if the child is bilingual, because the researchers must determine the most appropriate language to use for the consent process for the child and the parents. Holaday, Gonzales, and Mills (2007) included a list of seven questions in their article to assist researchers in determining the language for communication during a study.

TABLE 9-4

Sample Assent Form for Children Ages 6 To 12 Years: Pain Interventions for Children with Cancer

Oral Explanation

I am a nurse who would like to know if relaxation, special ways of breathing, and using your mind to think pleasant things help children like you to feel less afraid and feel less hurt when the doctor has to do a bone marrow aspiration or spinal tap. Today, and the next five times you and your parent come to the clinic, I would like for you to answer some questions about the things in the clinic that scare you. I would also like you to tell me about how much pain you felt during the bone marrow or spinal tap. In addition, I would like to videotape (take pictures of) you and your mom and/or dad during the tests. The second time you visit the clinic I would like to meet with you and teach you special ways to relax, breathe, and use your mind to imagine pleasant things. You can use the special imagining and breathing then during your visits to the clinic. I would ask you and your parent to practice the things I teach you at home between your visits to the clinic. At any time you could change your mind and not be in the study anymore.

To Child

1. I want to learn special ways to relax, breathe, and imagine.

2. I want to answer questions about things children may be afraid of when they come to the clinic.

3. I want to tell you how much pain I feel during the tests I have.

4. I will let you videotape me while the doctor does the tests (bone marrow and spinal taps).

If the child says YES, have him/her put an “X” here. ___

From Broome, M. E. (1999). Consent (assent) for research with pediatric patients. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 15(2): 101.

In addition to the assent of the child, you must obtain permission from the child’s parent or guardian for the child’s participation in a study. In studies of minimal risk, permission from one parent is usually sufficient for the research to be conducted. For research that involves more than minimal risk and has no prospect of direct benefit to the individual subject, “both parents must give their permission unless one parent is deceased, unknown, incompetent, or not reasonably available, or when only one parent has legal responsibility for the care and custody of the child” (U.S. DHHS, 2005, 45 CFR Section 46.408b).

Pregnant Women: Pregnant women require additional protection in research because of the fetus. Federal regulations define pregnancy as encompassing the period of time from implantation until delivery. “A woman is assumed to be pregnant if she exhibits any of the pertinent presumptive signs of pregnancy, such as missed menses, until the results of a pregnancy test are negative or until delivery” (U.S. DHHS, 2005, 45 CFR Section 46.202). Research conducted with pregnant women should have the potential to directly benefit the woman or the fetus. If your investigation is thought to provide a direct benefit only to the fetus, you must obtain the consent of the pregnant woman and father. Studies with “pregnant women should include no inducements to terminate the pregnancy and the researcher should have no part in any decision to terminate a pregnancy” (U.S. DHHS, 2005, 45 CFR Section 46.204).

Adults: Because of mental illness, cognitive impairment, or a comatose state, certain adults are incompetent and incapable of giving informed consent. Persons are said to be incompetent if, in the judgment of a qualified clinician, they have attributes that ordinarily provide the grounds for designating incompetence (Levine, 1986). Incompetence can be temporary (e.g., inebriation), permanent (e.g., advanced senile dementia), or subjective or transitory (e.g., behavior or symptoms of psychosis).

If an individual is judged incompetent and incapable of consent, you must seek approval from the prospective subject and his or her legally authorized representative. A legally authorized representative means an individual or other body authorized under applicable law to consent on behalf of a prospective subject to the subject’s participation in the procedure(s) involved in the research (Levine, 1986). However, individuals can be judged incompetent and can still assent to participate in certain minimal-risk research if they have the ability to understand what they are being asked to do, to make reasonably free choices, and to communicate their choices clearly and unambiguously.

Happ et al. (2007) conducted an ethnographic study to describe family members’ and clinicians’ interactions with intensive care unit (ICU) patients during their weaning from long-term mechanical ventilation (LTMV). Because some of the ICU patients were incompetent to give informed consent, the researchers obtained their assent if possible and their proxies’ or guardians’ permission for participation in the study. The following excerpt from this study will guide you in protecting the rights of persons with diminished autonomy by (1) obtaining institutional review board (IRB) approval for your study, (2) ensuring the privacy of patients during data collection, and (3) obtaining informed consent for all study participants based on their physical and mental capabilities.

A growing number of people have become permanently incompetent from the advanced stages of senile dementia of the Alzheimer type (SDAT). A minimum of 60% of nursing home residents have this condition (Floyd, 1988). Most long-term care settings have no IRB for research, and the families or guardians of patients in such settings are reluctant to give consent for the patients’ participation in research. Nursing research is needed to establish evidence-based interventions for comforting and caring for individuals with SDAT. Thus, there is a need to expand the development of IRBs in long-term care settings and the use of client advocates to assist in the consent process. Levine (1986) identified two approaches that families, guardians, researchers, or institutional review board might use when making decisions on behalf of these incompetent individuals: (1) best interest standard and (2) substituted judgment standard. The best interest standard involves doing what is best for the individual on the basis of balancing risks and benefits. The substituted judgment standard is concerned with determining the course of action that incompetent individuals would take if they were capable of making a choice.

Terminally Ill Subjects: When conducting research on terminally ill subjects, you should determine (1) who will benefit from the research and (2) whether it is ethical to conduct research on individuals who might not benefit from the study (U.S. DHHS, 2005). Participating in research could have greater risks and minimal or no benefits for these subjects. In addition, the dying subject’s condition could affect the study results and lead you to misinterpret the results (Watson, 1982). However, Hinds, Burghen, and Pritchard (2007) stressed the importance of conducting end-of-life studies in pediatric oncology to generate evidence that will improve the care for terminally ill children and adolescents and their families.

Some terminally ill individuals are willing subjects because they believe that participating in research is a way to contribute to society before they die. Others want to take part in research because they believe that the experimental process will benefit them. People with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) often want to participate in AIDS research to gain access to experimental drugs and hospitalized care. However, researchers are concerned because some of these individuals do not comply with the research protocol (Arras, 1990). This is a serious dilemma for researchers studying a population with any type of serious or terminal illness, because they must consider the rights of the subjects and be responsible for conducting high-quality research.

Subjects Confined to Institutions: Hospitalized patients have diminished autonomy because they are ill and are confined in settings that are controlled by health care personnel (Levine, 1986). Some hospitalized patients feel obliged to be research subjects because they want to assist a particular practitioner (nurse or physician) with his or her research. Others feel coerced to participate because they fear that their care will be adversely affected if they refuse. Some of these hospitalized patients are survivors of trauma (such as auto accidents, gunshot wounds, or physical and sexual abuse) who are very vulnerable and often have decreased decision-making capacities (McClain, Laughon, Steeves, & Parker, 2007). When conducting research with these types of patients, you must pay careful attention to the informed consent process and make every effort to protect these subjects from feelings of coercion and harm.

In the past, prisoners have experienced diminished autonomy in research projects because of their confinement. They might feel coerced to participate in research because they fear harm if they refuse or because they desire the benefits of early release, special treatment, or monetary gain. Prisoners have been used for drug studies in which there were no health-related benefits and there was possible harm for the prisoners (Levine, 1986). Current regulations regarding research involving prisoners require that “the risks involved in the research are commensurate with risks that would be accepted by nonprisoner volunteers and procedures for the selection of subjects within the prison are fair to all prisoners and immune from arbitrary intervention by prison authorities or prisoners” (U.S. DHHS, 2005, 45 CFR Section 46.305a).

Protecting subjects’ rights with diminished autonomy in research is regulated in many other countries as well. In Canada, the ethical conduct of research is governed by the Tri-Council Policy Statement on “Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Human Subjects” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, 2005). The Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) (2002) developed international ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects, and the guidelines require protection of vulnerable individuals, groups, communities, and populations during research. In summary, researchers must evaluate each prospective subject’s capacity for self-determination and protect subjects with diminished autonomy during the research process.

Right to Privacy

Privacy is an individual’s right to determine the time, extent, and general circumstances under which personal information will be shared with or withheld from others. This information consists of one’s attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, opinions, and records. An individual’s privacy was initially protected by the Privacy Act of 1974. As a result of this act, data collection methods were to be scrutinized to protect subjects’ privacy, and data cannot be gathered from subjects without their knowledge. Individuals also have the right to access their records and to prevent access by others (U.S. DHHS, 2002, 2005). The intent of this act was to prevent the invasion of privacy that occurs when private information is shared without an individual’s knowledge or against his or her will. Invading an individual’s privacy might cause loss of dignity, friendships, or employment or create feelings of anxiety, guilt, embarrassment, or shame.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule expanded the protection of an individual’s privacy, specifically his or her protected individually identifiable health information, and described the ways in which covered entities can use or disclose this information. Covered entities are the individual’s health care provider, health plan, employer, and health care clearinghouse (public or private entity that processes or facilitates the processing of health information). Individually identifiable health information (IIHI)

is information that is a subset of health information, including demographic information collected from an individual, and: (1) Is created or received by healthcare provider, health plan, or healthcare clearinghouse; and (2) Related to past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual, the provision of health care to an individual, or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to an individual, and that identifies the individual; or with respect to which there is a reasonable basis to believe that the information can be used to identify the individual. (U.S. DHHS, 2002, 45 CFR, Section 160.103)

According to the HIPAA Privacy Rule, the IIHI is protected health information (PHI) that is transmitted by electronic media, maintained in electronic media, or transmitted or maintained in any other form or medium. Thus, the HIPAA privacy regulations affect nursing research in the following ways: (1) accessing data from a covered entity, such as reviewing a patient’s medical record in clinics or hospitals; (2) developing health information, such as the data developed when an intervention is implemented in a study to improve a subject’s health; and (3) disclosing data from a study to a colleague in another institution, such as sharing data from a study to facilitate development of an instrument or scale (Olsen, 2003).

The U.S. DHHS developed guidelines to help researchers, health care organizations, and health care providers determine when they can use and disclose IIHI. IIHI can be used or disclosed to a researcher in the following situations:

• The protected health information has been “de-identified” under the HIPAA Privacy Rule. (De-identifying PHI is defined in the following section.)

• The data are part of a limited data set, and a data use agreement with the researcher(s) is in place.

• The individual who is a potential subject for a study authorizes the researcher to use and disclose his or her PHI.

• A waiver or alteration of the authorization requirement is obtained from an IRB or a privacy board (U.S. DHHS, 2007, February 2, a) (see http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/pr_08.asp).

The first two items are discussed in this section of the text. The authorization process is discussed in the section on obtaining informed consent, and the waiver or alteration of authorization requirement is covered in the section on understanding institutional review.

De-identifying Protected Health Information under the Privacy Rule

Covered entities, such as health care providers and agencies, can allow researchers access to health information if the information has been de-identified. De-identifying health data involves removing the 18 elements that could be used to identify an individual or his or her relatives, employer, or household members. The 18 identifying elements are as follows (U.S. DHHS, 2007 February 2, a):

2. All geographic subdivisions smaller than a state, including street address, city, county, precinct, zip code, and their equivalent geographical codes, except for the initial three digits of a zip code if, according to the current publicly available data from the Bureau of the Census:

a. The geographical unit formed by combining all zip codes with the same three initial digits contains more than 20,000 people

b. The initial three digits of a zip code for all such geographical units containing 20,000 or fewer people are changed to 000

3. All elements of dates (except year) for dates directly related to an individual, including birth date, admission date, discharge date, date of death; and all ages over 89 and all elements of dates (including year) indicative of such age, except that such ages and elements may be aggregated into a single category of age 90 or older

6. Electronic mail (e-mail) addresses

9. Health plan beneficiary numbers

11. Certificate/license numbers

12. Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license plate numbers

13. Device identifiers and serial numbers

14. Web universal resource locators (URLs)

15. Internet protocol (IP) address numbers

16. Biometric identifiers, including fingerprints and voiceprints

17. Full-face photographic images and any comparable images

18. Any other unique identifying number, characteristic, or code, unless otherwise permitted by the Privacy Rule for re-identification

An individual’s health information can also be de-identified using statistical methods. However, the covered entity and you as the researcher must ensure that the individual subject cannot be identified or that there is a very small risk that the subject could be identified from the information used. The statistical method used for de-identification of the health data must be documented, and you must certify that the 18 elements for identification have been removed or revised to ensure that individual is not identified. You must retain this certification information for 6 years.

Limited Data Set and Data Use Agreement

Covered entities (health care provider, health plan, and health care clearinghouse) may use and disclose a limited data set to a researcher for a study without an individual subject’s authorization or an IRB waiver. However, a limited data set is considered protected health information, and the covered entity and the researcher must have a data use agreement. The data use agreement limits how the data set may be used and how it will be protected. The HIPAA Privacy Rule requires the data use agreement to do the following (U.S. DHHS, 2002):

1. Specifies the permitted uses and disclosures of the limited data set.

2. Identifies the researcher who is permitted to use or receive the limited data set.

3. Stipulates that the recipient (researcher) will

a. Not use or disclose the information other than permitted by the agreement.

b. Use appropriate safeguards to prevent the use or disclosure of the information, except as provided for in the agreement.

c. Hold any other person (co-researchers, statisticians, or data collectors) to the standards, restrictions, and conditions stated in the data use agreement with respect to the health information.

d. Not identify the information or contact the individuals whose data are in the limited data set.

Right to Autonomy and Confidentiality

On the basis of the right to privacy, the research subject has the right to anonymity and the right to assume that the data collected will be kept confidential. Anonymity exists if the subject’s identity cannot be linked, even by the researcher, with his or her individual responses (ANA, 2001; Sasson & Nelson, 1971). For studies that use de-identified health information or data from a limited data set, the subjects will be anonymous to the researcher. You will be unable to contact these subjects for additional information.

In most studies, researchers desire to know the identity of their subjects and promise that their identity will be kept anonymous from others. However, in these situations, you must receive authorization from the potential subject to use his or her health information, or you must have a waiver or an alteration of the authorization requirement from the IRB (see section on institutional review later in this chapter). Confidentiality is the researcher’s management of private information shared by a subject that must not be shared with others without the authorization of the subject. Confidentiality is grounded in the following premises:

• Individuals can share personal information to the extent they wish and are entitled to have secrets.

• One can choose with whom to share personal information.

• People who accept information in confidence have an obligation to maintain confidentiality.

• Professionals, such as researchers, have a “duty to maintain confidentiality that goes beyond ordinary loyalty” (Levine, 1986, p. 164; U.S. DHHS, 2005).

Breach of Confidentiality

A breach of confidentiality can occur when a researcher, by accident or direct action, allows an unauthorized person to gain access to the study raw data. Confidentiality can also be breached in the reporting or publication of a study when a subject’s identity is accidentally revealed, violating the subject’s right to anonymity (Ramos, 1989). Breaches of confidentiality can harm subjects psychologically and socially, as well as destroy the trust they had in you. Breaches of confidentiality can be especially harmful to a research subject if they involve (1) religious preferences; (2) sexual practices; (3) employment; (4) racial prejudices; (5) drug use; (6) child abuse; and (7) personal attributes, such as intelligence, honesty, and courage.

Some nurse researchers have encountered health care professionals who believe that they should have access to information about the patients in the hospital and will request to see the data the researchers have collected. Sometimes, family members or close friends would like to see the data collected on specific subjects. Sharing research data in these circumstances is a breach of confidentiality. When requesting permission to conduct a study, you should tell health care professionals, family members, and others in the setting that you will not share the raw data. However, you may elect to share the research report, including a summary of the data and findings from the study, with health care providers, family members, and other interested parties.

Maintaining Confidentiality

Researchers have a responsibility to protect the anonymity of subjects and to maintain the confidentiality of data collected during a study. You can protect anonymity by giving each subject a code number. Keep a master list of the subjects’ names and their code numbers in a locked place; for example, subject Mary Jones might be assigned the code number “001.” All of the instruments and forms that Mary completes and the data you collect about her during the study will be identified with the “001” code number, not her name. The master list of subjects’ names and code numbers is best kept separate from the data collected to protect subjects’ anonymity. You should not staple signed consent forms and authorization documents to instruments or other data collection tools, as this would make it easy for unauthorized persons to readily identify the subjects and their responses. Consent forms are often stored with the master list of subjects’ names and code numbers. When entering the data collected into the computer, use the code numbers for identification. Then lock the original data collection tools in a secure place.

Another way to protect your subjects’ anonymity is to have them generate their own identification codes (Damrosch, 1986). With this approach, each subject generates an individual code from personal information, such as the first letter of a mother’s name, the first letter of a father’s name, the number of brothers, the number of sisters, and middle initial. Thus, the code would be composed of three letters and two numbers, such as “BD21M.” This code would be used on each form that the subject completes. Even you as the researcher would not know the subject’s identity, only the subject’s code. If the data collected are highly sensitive, you might want to use this type of coding system.

The data collected should undergo group analysis so that an individual cannot be identified by his or her responses. If the subjects are divided into groups for data analysis and there is only one subject in a group, combine that subject’s data with that of another group or delete the data. In writing the research report, you should describe the findings in such a way that an individual or a group of individuals cannot be identified by their responses.

Maintaining confidentiality is often more difficult in qualitative research than in quantitative research. The nature of qualitative research requires that the “investigator must be close enough to understand the depth of the question under study, and must present enough direct quotes and detailed description to answer the question” (Ramos, 1989, p. 60). The small number of participants used in a qualitative study and the depth of detail gathered on each participant make it difficult to disguise the participant’s identity. Ford and Reutter (1990) have recommended that to maintain confidentiality, the researcher should (1) use pseudonyms instead of the participants’ names and (2) distort certain details in the participants’ stories while leaving the contents unchanged. You must respect participants’ privacy as they decide how much detail and editing of private information are necessary to publish a study (Munhall, 2001a; Orb, Eisenhauer, & Wynaden, 2001).

Researchers should also take precautions during data collection to maintain confidentiality. The interviews conducted with participants are frequently taped and later transcribed, so the participant’s name should not be mentioned on the tape. They have the right to know whether anyone other than you will be transcribing information from the interview. In addition, participants should be informed on an ongoing basis that they have the right to withhold information. To critique the rigor and credibility of qualitative research, produce an audit trail so that another researcher could examine the data to confirm the study findings. This process might create a dilemma regarding the confidentiality of participants’ data, so you must inform them if other researchers will be examining their data to ensure the credibility of the study findings (Munhall, 2001a; Orb et al., 2001).

Right to Fair Treatment

The right to fair treatment is based on the ethical principle of justice. This principle holds that each person should be treated fairly and should receive what he or she is due or owed. In research, the selection of subjects and their treatment during the course of a study should be fair.

Fair Selection of Subjects

In the past, injustice in subject selection has resulted from social, cultural, racial, and sexual biases in society. For many years, research was conducted on categories of individuals who were thought to be especially suitable as research subjects, such as the poor, charity patients, prisoners, slaves, peasants, dying persons, and others who were considered undesirable (Reynolds, 1979). Researchers often treated these subjects carelessly and had little regard for the harm and discomfort they experienced. The Nazi medical experiments, Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and Willowbrook study all exemplify unfair subject selection and treatment.

The selection of a population and the specific subjects to study should be fair, and the risks and benefits of a study should be fairly distributed on the basis of the subject’s efforts, needs, and rights. Subjects should be selected for reasons directly related to the problem being studied and not for “their easy availability, their compromised position, or their manipulability” (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1978, p. 10).

Another concern with subject selection is that some researchers select certain people as subjects because they like them and want them to receive the specific benefits of a study. Other researchers have been swayed by power or money to make certain individuals subjects so that they can receive potentially beneficial treatments. Random selection of subjects can eliminate some of the researcher bias that might influence subject selection.

A current concern in the conduct of research is finding an adequate number of appropriate subjects to take part in certain studies. As a solution to this problem in the past, some biomedical researchers have offered physicians a finder’s fee for identifying research subjects. For example, investigators studying patients with lung cancer would give a physician a fee for every patient with lung cancer the physician referred to them. However, the HIPAA Privacy Rule requires that individuals give their authorization before PHI can be shared with others. Thus, health care providers cannot recommend individuals for studies without their permission. Researchers can obtain a partial waiver from the IRB or privacy board so that they can obtain PHI necessary to recruit potential subjects (U.S. DHHS, 2002). This makes it more difficult for researchers to find subjects for their studies; however, researchers are encouraged to work closely with their IRBs to facilitate the conduct of quality studies essential for evidence-based practice.

Fair Treatment of Subjects

Researchers and subjects should have a specific agreement about what the subject’s participation involves and what the role of the researcher will be (APA, 2002). While conducting a study, you should treat the subjects fairly and respect that agreement. If the data collection requires appointments with the subjects, be on time for each appointment and terminate the data collection process at the agreed-on time. You should not change the activities or procedures that the subject is to perform unless you obtain the subject’s consent.

The benefits promised the subjects should be provided. For example, if you promise a subject a copy of the study findings, you should deliver your promise when the study is completed. In addition, subjects who participate in studies should receive equal benefits, regardless of age, race, and socioeconomic level. When possible, the sample should be representative of the study population and should include subjects of various ages, ethnic backgrounds, and socioeconomic status (Williams, 2002). Treating subjects fairly often facilitates the data collection process and decreases subjects’ withdrawal from a study (Orb et al., 2001).

Right to Protection from Discomfort and Harm

The right to protection from discomfort and harm is based on the ethical principle of beneficence, which holds that one should do good and, above all, do no harm. According to this principle, members of society should take an active role in preventing discomfort and harm and promoting good in the world around them (Frankena, 1973). Therefore, researchers should conduct their studies to protect subjects from discomfort and harm and try to bring about the greatest possible balance of benefits in comparison with harm.

Discomfort and harm can be physiological, emotional, social, and economic in nature. Reynolds (1979) identified the following five categories of studies, which are based on levels of discomfort and harm: (1) no anticipated effects, (2) temporary discomfort, (3) unusual levels of temporary discomfort, (4) risk of permanent damage, and (5) certainty of permanent damage. Each level is defined in the following discussion.

No Anticipated Effects

In some studies, the subjects expect neither positive nor negative effects. For example, studies that involve reviewing patients’ records, students’ files, pathology reports, or other documents have no anticipated effects on the subjects. In these types of studies, the researcher does not interact directly with the research subjects. Even in these situations, however, there is a potential risk of invading a subject’s privacy. The HIPAA Privacy Rule requires that the agency providing the health information de-identify the 18 essential elements, which could be used to identify an individual, to promote subjects’ privacy during a study.

Temporary Discomfort

Studies that cause temporary discomfort are described as minimal-risk studies, in which the discomfort encountered is similar to what the subject would experience in his or her daily life and ceases with the termination of the study. Many nursing studies require the subjects to complete questionnaires or participate in interviews, which usually involve minimal risk. The physical discomforts might be fatigue, headache, or muscle tension. The emotional and social risks might entail the anxiety or embarrassment associated with responding to certain questions. The economic risks might consist of the time spent participating in the study or travel costs to the study site. Participation in many nursing studies is considered a mere inconvenience for the subject, with no foreseeable risks of harm.

Most clinical nursing studies examining the impact of a treatment involve minimal risk. For example, your study might involve examining the effects of exercise on the blood glucose levels of diabetics. During the study, you ask the subjects to test their blood glucose level one extra time per day. There is discomfort when the blood is drawn and a risk of physical changes that might occur with exercise. The subjects might also experience anxiety and fear in association with the additional blood testing, and the testing is an added expense. The diabetic subjects in this study would experience similar discomforts in their daily lives, and the discomforts would cease with the termination of the study.

Unusual Levels of Temporary Discomfort

In studies that involve unusual levels of temporary discomfort, the subjects commonly experience discomfort both during the study and after its termination. For example, subjects might experience a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), prolonged muscle weakness, joint pain, and dizziness after participating in a study that required them to be confined to bed for 10 days to determine the effects of immobility. Studies that require subjects to experience failure, extreme fear, or threats to their identity or to act in unnatural ways involve unusual levels of temporary discomfort. In some qualitative studies, participants are asked questions that reopen old emotional wounds or involve reliving traumatic events (Ford & Reutter, 1990; Munhall, 2001a). For example, asking participants to describe their rape experience could precipitate feelings of extreme fear, anger, and sadness. In these types of studies, you should be vigilant about assessing the participants’ discomfort and should refer them for appropriate professional intervention as necessary.

Risk of Permanent Damage

In some studies, subjects have the potential to suffer permanent damage; this potential is more common in biomedical research than in nursing research. For example, medical studies of new drugs and surgical procedures have the potential to cause subjects permanent physical damage. However, nurses have investigated topics that have the potential to damage subjects permanently, both emotionally and socially. Studies examining sensitive information, such as sexual behavior, child abuse, or drug use, can be risky for subjects. These types of studies have the potential to cause permanent damage to a subject’s personality or reputation. There are also potential economic risks, such as reduced job performance or loss of employment.

Certainty of Permanent Damage

In some research, such as the Nazi medical experiments and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the subjects experience permanent damage. Conducting research that will permanently damage subjects is highly questionable, regardless of the benefits gained. Frequently, the benefits are for other people but not for the subjects. Studies causing permanent damage to subjects violate the fifth principle of the Nuremberg Code (1986, p. 426), which states, “No experiment should be conducted where there is an a priori reason to believe that death or disabling injury will occur except, perhaps, in those experiments where the experimental physicians (or other health professionals) also serve as subjects.”

BALANCING BENEFITS AND RISKS FOR A STUDY

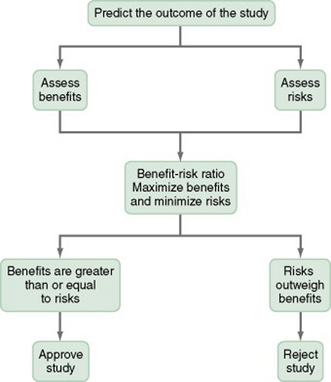

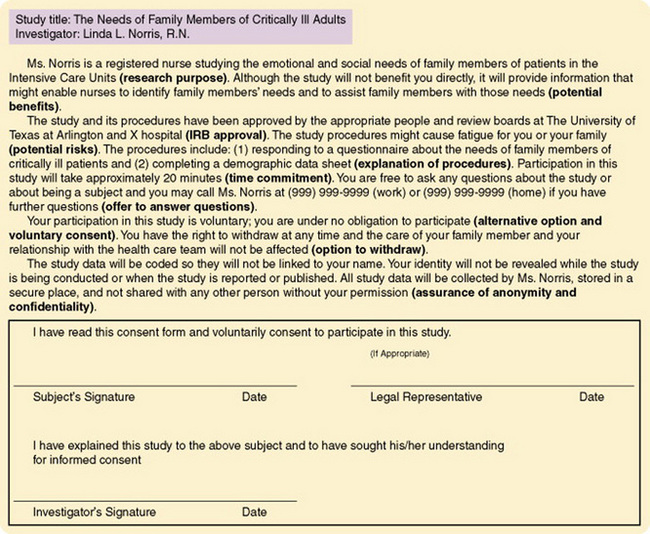

Researchers and reviewers of research must examine the balance of benefits and risks in a study. To determine this balance or benefit-risk ratio, you must (1) predict the outcome of your study, (2) assess the actual and potential benefits and risks on the basis of this outcome, and then (3) maximize the benefits and minimize the risks (see Figure 9-1). The outcome of a study is predicted on the basis of previous research, clinical experience, and theory.

Assessment of Benefits

The probability and magnitude of a study’s potential benefits must be assessed.

A research benefit is defined as something of health-related, psychosocial, or other value to a subject, or something that will contribute to the acquisition of knowledge for evidence-based practice. Money and other compensations for participation in research are not benefits but, rather, are remuneration for research-related inconveniences. (U.S. DHHS, 2005)

In most proposals, the research benefits are described for the individual subjects, subjects’ families, and society. Some optimistic researchers overestimate these benefits.

The type of research conducted, whether therapeutic or nontherapeutic, affects the potential benefits for the subjects. In therapeutic nursing research, the individual subject has the potential to benefit from the procedures, such as skin care, range of motion, touch, and other nursing interventions, that are implemented in the study. The benefits might include improvement in the subject’s physical condition, which could facilitate emotional and social benefits. In addition, the knowledge generated from the research might expand the subjects’ and their families’ understanding of health. The conduct of nontherapeutic nursing research does not benefit the subject directly but is important to generate and refine nursing knowledge for practice. By participating in research, subjects have the potential to increase their understanding of the research process and an opportunity to know the findings from a particular study.

Assessment of Risks

You must assess the type, severity, and number of risks that subjects will experience or might experience by participating in your study. The risks involved depend on the purpose of the study and the procedures used to conduct it. Research risks can be physical, emotional, social, and economic in nature and can range from no risk or mere inconvenience to the risk of permanent damage (Levine, 1986; Reynolds, 1979). Studies can have actual (known) risks and potential risks for subjects. In a study of the effects of prolonged bed rest, for example, an actual risk would be muscle weakness and the potential risk would be a DVT. Some studies have actual or potential risks for the subjects’ families and society. You must determine the likelihood of the risks and take precautions to protect the rights of subjects when implementing your study.

Benefit-Risk Ratio

The benefit-risk ratio is determined on the basis of the maximized benefits and the minimized risks. The researcher attempts to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks by making changes in the study purpose or procedures or both. If the risks entailed by your study cannot be eliminated or further minimized, you need to justify their existence. If the risks outweigh the benefits, you should revise the study or develop a new study. If the benefits equal or outweigh the risks, you can justify conducting the study, and an institutional review board (IRB) will probably approve it (see Figure 9-1).