Emerging Trends

An interesting pursuit in tumor biology would be studying the biologic behavior of neoplasms in general and follow the subtle differences that exists with individual tumors. Among the many variables would be consideration of the site, size, histologic grades, etiologic factors and stage of progression of individual neoplasms. This newer approach of carefully monitoring tumors comprise a separate area of ‘biologic staging’, which is currently gaining acceptance in clinical practice (Table 2-10). Another interesting trend currently being investigated is the use of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to determine if surgical margins obtained at the time of surgery that are histopathologically free of tumor contain a small amount of histologically undetectable tumor cells. Specifically, the use of PCR to detect specific p53 mutations identified in the primary tumor in the histopathologically negative surgical margin could be very useful, as these mutations would indicate the presence of residual (histopathologically undetected) tumor cells. It will be very important to establish whether the presence of submicroscopic tumor cells contributes to prognosis and clinical outcome. The recent development of in situ PCR will allow amplification of both DNA and RNA directly in tissue section; this technique should be extremely helpful in the future to localize tumor cells containing altered oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes. An improved understanding of the molecular biology of head and neck cancer may also contribute to future therapeutic improvements. Finally, molecular probes may be used to facilitate the early detection of secondary malignancies.

Table 2-10

Biomarker predictors in oral precancerous and cancerous lesions

| Marker method | Detection | Target |

| Proliferation | ||

| PCNA, Ki67, BrU | IHC | Cycling cells |

| Histone | mRNA ISH | |

| AgNORs | Silver stain | |

| Genetic | ||

| Ploidy | FC | Aneuploid cells |

| Oncogenes | ||

| C-myc | IHC | Cycling cells |

| Tumor suppressor | ||

| p53 mutations | IHC, PCR | Cycling cells |

| Cytokeratin 8/19 | IHC | Anaplasia |

| Blood group antigens | IHC | Anaplasia |

| Integrins/ECM ligands | IHC | Invasion and metastatic potential |

IHC: immunohistochemistry, FC: flowcytometry, PCR: polymerase chain reaction, ISH: in-situ hybridization.

Under the current management, the strategy for head and neck cancer includes specialists from many disciplines and their concerted effort will promote the use of increasingly refined laboratory techniques for improved diagnosis and therapy. A good deal of current laboratory and clinical research is focusing on identifying the relative contributions of certain oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes on carcinogenesis, tumor stage, and clinical outcome. Although abnormalities of some oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes have been identified, their relative contribution and optimal use in diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment remain unknown. The same might be said for the role of Epstein-Barr, hepatitis, and herpes simplex viruses; further clinicolaboratory studies will be needed to define which are clinically relevant and when they should be investigated. Genetic analysis at a molecular/chromosomal level is emerging as a science that may aid in identifying risk and possibly prevention as well. Finally, a reliable and predictable histopathology grading system should be developed to include, in addition to differentiation of tumor cells, such factors as basement membrane protein expression and invasion patterns, perineural invasion, and immunologic responses.

Carcinoma of Lip

Epidermoid carcinoma of the lip is a disease that occurs chiefly in elderly men. Furthermore, the lower lip is involved by this neoplasm far more commonly than the upper lip. Great numbers of cases have been reported in the literature, and the data of Cross, Guralnick and Daland on 563 patients with lip cancer may be cited to illustrate certain typical characteristics. In this large series, it was found that 98% of the patients were men and that the age of these patients at the onset of the disease ranged from 25–91 years, with the greatest incidence between 55 and 75 years and a mean of 62 years of age. Of the total group of lip cancers, 88.3% occurred on the lower lip, 3.3% on the upper lip and 8.3% on the labial commissures. The right and left sides were affected with equal frequency. In 636 cases reviewed by Schreiner, similar findings were reported. In his series 97% of the lesions occurred in men, and 96% were found on the lower lip. Nearly one-third of his cases occurred between the ages of 60 and 70 years.

Etiology

A number of possible etiologic factors have been suggested by the review of the records of many patients. One of the most common of these has been the use of tobacco, chiefly through pipe-smoking. The data of Cross and his coworkers indicate that 64% of their patients with lip cancer were pipe smokers, while a total of 94% habitually used tobacco in some form. These observations are in agreement with the data of Widmann, who, in a review of 363 cases of lip cancer, estimated an incidence of approximately 40% pipe smokers. Schreiner reported that 87% of his lip cancer patients were tobacco users. Although no conclusions may be drawn from such data because of the widespread use of tobacco in the general population, it appears suggestive that the heat, the trauma of the pipe stem and possibly the combustion end-products of tobacco may be of some significance in the etiology of lip cancer.

Syphilis is probably not as significant an etiologic factor in lip cancer as in certain other oral sites, since the incidence of lip cancer has been found to be low in syphilitic patients: 7.2% by Cross and his associates, 8% by Widmann and 3.6% by Schreiner. As indicated previously; however, the data of Wynder and his group indicated that syphilis was of etiologic significance in lip cancer.

Sunlight is generally considered to be important, as discussed previously, because the alterations which occur in skin and lips as a result of prolonged exposure to sun are characterized as preneoplastic. Ju has discussed this problem and constructed a profile of the lip cancer patient.

Poor oral hygiene is an almost universal finding in patients with lip cancer. Cross and his group pointed out that only approximately 8% of their entire series of patients had good or even fair oral hygiene. In addition, some patients indicate a history of trauma before the appearance of a lesion. They report not only a single traumatic experience, such as a cigarette burn or a cut, but also chronic trauma from jagged teeth and so forth. Unfortunately, it is difficult to assess scientifically the role of such factors in the etiology of cancer.

Leukoplakia has often been associated with the development of carcinoma. Since clinical leukoplakia is a fairly common lesion of the lip, it was only natural that the relationship should be investigated. Schreiner found leukoplakia present in only 2.4% of his 636 cases of lip cancer, while Cross and coworkers found leukoplakia associated with carcinoma in 14.5% of the cases in their series. This would indicate that the simultaneous occurrence of the two conditions is probably due to chance and that leukoplakia is not a common predecessor of lip cancer. However, in light of more recent studies dealing with the frequency of preneoplastic and neoplastic transformation in lesions of leukoplakia of the lip (q.v.), the interpretation of the above findings is uncertain.

Clinical Features

There is considerable variation in the clinical appearance of lip cancer, depending chiefly upon the duration of the lesion and the nature of the growth. The tumor usually begins on the vermilion border of the lip to one side of the midline. It often commences as a small area of thickening, induration and ulceration or irregularity of the surface. As the lesion becomes larger it may create a small crater like defect or produce an exophytic, proliferative growth of tumor tissue. Some patients have large fungating masses in a relatively short time, while in other patients the lesion may be only slowly progressive.

Carcinoma of the lip is generally slow to metastasize, and a massive lesion may develop before there is evidence of regional lymph node involvement. Some lesions; however, particularly the more anaplastic ones, may metastasize early. When metastasis does occur, it is usually ipsilateral and involves the submental or submaxillary nodes. Contralateral metastasis may occur, especially if the lesion is near the midline of the lip where there is a cross drainage of the lymphatic vessels.

Histologic Features

Most lip carcinomas are well-differentiated lesions, often classified as grade I carcinoma. This type of cancer tends to metastasize late in the course of the disease. In the series of Widmann, the following approximate distribution of graded lesions was found: grade I, 60%; grade II, 26%; grade III, 13%; grade IV, 2%.

Treatment and Prognosis

Carcinoma of the lip has been treated by either surgical excision or X-ray radiation with approximately equal success, depending to some degree upon the duration and extent of the lesion and the presence of metastases. Interestingly, in the series of Cross the overall cure rate of patients with lip cancer treated by surgery was approximately 81%, while in the series of Widmann the cure rate of patients with the same type of neoplasm treated by X-ray radiation was approximately 83%. This would indicate that either form of therapy, in skilled hands, will produce equally good results.

Many factors may influence the success or failure of treatment of lip carcinoma. The size of the lesion, its duration, the presence or absence of metastatic lymph nodes and the histologic grade of the lesion must all be considered carefully by the therapist in planning his/her approach to the neoplastic problem.

Carcinoma of Tongue

Cancer of the tongue comprises between 25 and 50% of all intraoral cancer. It is less common in women than in men except in certain geographic localities, chiefly the Scandinavian countries, where the incidence of all intraoral carcinoma in women is high because of the high incidence of a preexisting Plummer–Vinson syndrome. In a series of 441 cases of tongue cancer reported by Ash and Millar, 25% occurred in women and 75% in men, with an average age of 63 years. In a series of 330 cases of cancer of the tongue reported by Gibbel, Cross and Ariel the average age of the patient was 53 years, with a range of 32–87 years. Thus it is essentially a disease of the elderly, but it may occur in relatively young persons. To exemplify this latter point, a series of 11 patients less than 30 years of age, four of them less than 20 years, with carcinoma of the tongue has been reported by Byers. This group of patients represented approximately 3% of all patients seen at MD Anderson Hospital with epidermoid carcinoma of the tongue between 1956 and 1973 (418 cases).

Etiology

A number of causes of cancer of the tongue have been suggested, but in our present state of knowledge no precise statements can be made. A definite relation does appear to exist; however, between tongue cancer and certain other disorders. Many investigators have found syphilis, either an active case or at least a past history of it, coexistent with carcinoma of the tongue. In the series of Gibbel et al, 22% of patients with lingual cancer demonstrated a positive complement fixation or Kahn reaction, while in the general admission at their hospital only 5% of the patients had a positive reaction for syphilis. Martin reported that 33% of his patients with cancer of the tongue also had syphilis. The relationship can be explained on the basis of a chronic glossitis produced by the syphilis, chronic irritation long being recognized as carcinogenic under certain circumstances. This explanation implies a local effect of syphilis rather than a generalized or systemic effect. It should be pointed out that some studies do not confirm the theory of a relationship between syphilis and tongue cancer. Wynder has confirmed this relationship, but questioned whether the neoplasm might be related to the arsenic therapy, the treatment of choice before the advent of antibiotics, rather than to the syphilis itself. Meyer and Abbey have also questioned this relationship since they found only 15 patients (6%) who showed positive evidence of a history of syphilis in a survey of 243 cases of primary carcinoma of the tongue.

Leukoplakia is a common lesion of the tongue which has been observed many times to be associated with tongue cancer. Martin noted that 46% of his series of cancer patients had leukoplakia of the tongue, while Gibbel et al, found only a 10% incidence of leukoplakia in his series. It is not unusual to see typical lesions of carcinoma in leukoplakic areas; on the other hand, many lesions of leukoplakia appear to persist for years without malignant transformation, and many cases of carcinoma of the tongue develop without evidence of preexisting leukoplakia.

Other factors which have been thought to contribute to the development of carcinoma of the tongue include poor oral hygiene, chronic trauma and the use of alcohol and tobacco. Poor hygiene and the use of alcohol and tobacco are so prevalent as nearly to preclude the possibility of drawing conclusions about a possible cause and effect relation. A considerable number of cases have been observed in which cancer of the tongue developed at a site exactly corresponding to a source of chronic irritation such as a carious or broken tooth or an ill-fitting denture. The work of Wynder and his group; however, suggests that these findings may be fortuitous.

Clinical Features

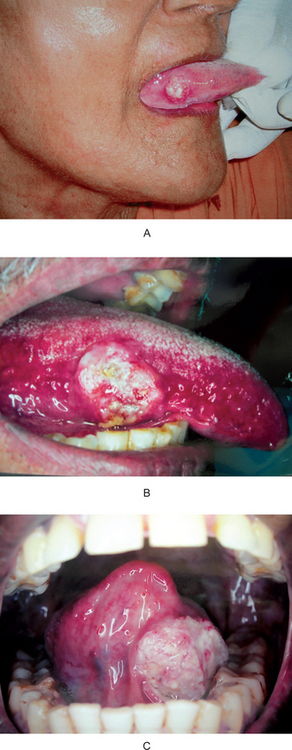

The most common presenting sign of carcinoma of the tongue is a painless mass or ulcer, although in most patients the lesion ultimately becomes painful, especially when it becomes secondarily infected. The tumor may begin as a superficially indurated ulcer with slightly raised borders and may proceed either to develop a fungating, exophytic mass or to infiltrate the deep layers of the tongue, producing fixation and induration without much surface change (Fig. 2-27 A–C).

The typical lesion develops on the lateral border or ventral surface of the tongue. When, in rare cases, carcinoma occurs on the dorsum of the tongue, it is usually in a patient with a past or present history of syphilitic glossitis. In a series of 1,554 cases of carcinoma of the tongue reported by Frazell and Lucas, only 4% occurred on the dorsum. The lesions on the lateral border are rather equally distributed between the base of the tongue, the anterior third and the mid portion, although in the above series 45% of cases occurred on the middle third. Lesions near the base of the tongue are particularly insidious, since they may be asymptomatic until far advanced. Even then the only presenting manifestations may be a sore throat and dysphagia. The specific site of development of these tumors is of great significance, since the lesions on the posterior portion of the tongue are usually of a higher grade of malignancy, metastasize earlier and offer a poorer prognosis, especially because of their inaccessibility for treatment.

Metastases occur with great frequency in cases of tongue cancer. In 302 patients on whom information was available, Gibbel and his group reported that cervical metastases from tongue lesions were present in 69% at the time of admission to the hospital. The metastatic lesions may be ipsilateral, bilateral, or because of the cross lymphatic drainage, contralateral in respect to the tongue lesion.

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of cancer of the tongue is a difficult problem, and even now no specific statements can be made about the efficacy of surgery in comparison to that of X-ray radiation. As in other areas, it will probably be found that the judicious combination of surgery and X-ray will be of greatest benefit to the patient. Many radiotherapists prefer the use of radium needles or radon seeds to X-ray radiation because they are able with these devices to limit the radiation to the tumor, sparing adjacent normal tissue. Metastatic nodes are highly complicating factors, but treating them without controlling the primary lesion is useless.

The prognosis of cancer in this location is not good. Although statistics vary between series, the five-year cure rate is generally conceded to be below 25%. Martin reported a 22% survival in 556 patients with tongue cancer, while Gibbel et al, found only a 14% survival among 213 patients. Frazell and Lucas reported an overall five-year cure rate of 35% on a series of 1,321 patients with tongue cancer.

The most significant factor affecting prognosis of these patients is the presence or absence of cervical metastases. Thus the studies of Gibbel and his associates showed an 81% survival rate if no metastases ever developed, 43% if no metastases were present at the time of hospital admission, and only 4% if metastases were present at the time of admission or developed subsequent to admission. The necessity for early diagnosis thus becomes obvious, and the role of the dentist in recognizing cancerous lesions is, of course, of paramount importance.

Carcinoma of Floor of Mouth

Carcinoma of the floor of the mouth represents approximately 15% of all cases of intraoral cancer and occurs in the same age group as other oral cancers. The average age of the patient was 57 years in the series of Tiecke and Bernier, 67 years in the series of 110 cases reported by Ash and Millar and 63 years in the group of 100 cases reported by Ballard and his associates. In the latter report, 81% of the lesions occurred in men, while 93% of the patients were men in the series of Ash and Millar.

Smoking, especially a pipe or cigar, has been considered by some investigators to be important in the etiology of cancer in this location. In the series of Ballard and his coworkers, 50% of the patients were classified as heavy smokers, 33% as heavy drinkers and 28% as heavy smokers and heavy drinkers. Nevertheless, little evidence has been gathered to suggest an obvious cause-and-effect relation with regard to tobacco or other factors such as alcohol, poor oral hygiene or dental irritation. Leukoplakia does occur in this location and there is evidence to indicate that epithelial dysplasia and malignant transformation in the leukoplakia occur here with greater frequency than in other oral sites.

Clinical Features

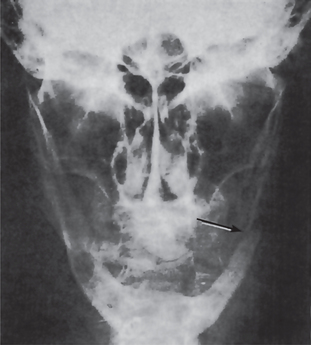

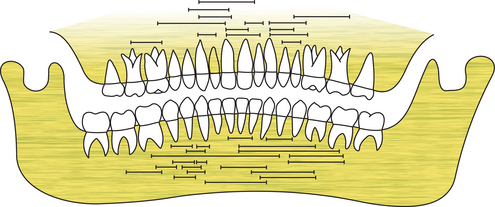

The typical carcinoma in the floor of the mouth is an indurated ulcer of varying size situated on one side of the midline. It may or may not be painful. This neoplasm occurs far more frequently in the anterior portion of the floor than in the posterior area. Because of its location, early extension into the lingual mucosa of the mandible and into the mandible proper as well as into the tongue occurs with considerable frequency (Fig. 2-28). Carcinoma of the floor of the mouth may invade the deeper tissues and may even extend into the submaxillary and sublingual glands. The proximity of this tumor to the tongue, producing some limitation of motion of that organ, often induces a peculiar thickening or slurring of the speech.

Metastases from the floor of the mouth are found most commonly in the submaxillary group of lymph nodes, and since the primary lesion frequently occurs near the midline where a lymphatic cross drainage exists, contralateral metastases are often present. Of 95 cases of carcinoma of the floor of the mouth reviewed by Ash and Millar, 21% presented lymph node involvement at the time of admission, while an additional 23% subsequently developed lymphadenopathy. Thus the total incidence of metastasis was 44%. This corresponds to the incidence of 42% metastatic lymph node involvement in the series reported by Tiecke and Bernier and 58% by Martin and Sugarbaker. Fortunately, distant metastases are rare.

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of cancer of the floor of the mouth is difficult and all too frequently unsuccessful. Large lesions, because of the anatomy of the region, usually are not a surgical problem. Even small tumors are apt to recur after surgical excision. For this reason, X-ray radiation and the use of radium often give far better results than surgery. The problem is complicated, however, if there is concomitant involvement of the mandible.

The prognosis for patients with carcinoma of the floor of the mouth is fair. The net five-year survival of 86 patients with cancer in this location reviewed by Ash and Millar was 43%. All patients in this series were treated by some form of radiation. Martin and Sugarbaker reported a five-year survival rate of 21% in their series of 103 patients.

Carcinoma of Buccal Mucosa

Reported studies of carcinoma of the buccal mucosa reveal exceptional variation in incidence, the widest differences being accounted for by studies from countries other than the United States. In the series of Krolls and Hoffman, cancer of the buccal mucosa comprised 3% of the total cases of intraoral carcinoma. Like most cancers of the oral cavity, cancer of the buccal mucosa is approximately 10 times more common in men than in women and occurs chiefly in elderly persons. In the study of Tiecke and Bernier, the average age at occurrence of carcinoma of the buccal mucosa was 58 years.

Etiology

The etiology of carcinoma of the buccal mucosa is no better understood than that of carcinoma of other areas of the oral cavity. Several factors appear to be of indisputable significance, however; these include the use of chewing tobacco and the habit of chewing betel nut, which is widespread in many countries in the Far East. It is a fairly common clinical observation that carcinoma of the buccal mucosa develops in the area against which a person has habitually carried a quid of chewing tobacco for years while the opposite cheek may be normal, the patient never having rested the tobacco there. Although this is only presumptive evidence of a cause-and-effect relation; it has been recognized so frequently that it appears to be more than a coincidental finding. A special form of neoplasm known as ‘verrucous carcinoma’ (q.v.) occurs almost exclusively in elderly patients with a history of tobacco chewing. Since the betel nut quid contains tobacco as well as other substances, including slaked lime, the high incidence of cancer in persons addicted to its use may be explained on a similar basis.

Leukoplakia is a common predecessor of carcinoma of the buccal mucosa. It is usually of extremely long duration and may or may not necessarily be associated with the use of tobacco. Chronic trauma in the form of cheek biting and dental irritation such as that from jagged teeth does not appear to be associated with the development of carcinoma, although focal areas of leukoplakia sometimes occur when these conditions exist.

Clinical Features

There is considerable variation in the clinical appearance of carcinoma of the buccal mucosa. The lesions develop most frequently along or inferior to a line opposite the plane of occlusion. The anteroposterior position is variable, some cases occurring near the third molar area, others anteriorly towards the commissure.

The lesion is often a painful ulcerative one in which induration and infiltration of deeper tissues are common. Some cases, however, are superficial and appear to be growing outward from the surface rather than invading the tissues. Tumors of this latter type are sometimes called exophytic or verrucous growths.

The incidence of metastases from the usual epidermoid carcinoma of the buccal mucosa varies considerably, but is relatively high. Tiecke and Bernier reported that 45% of the patients in their study exhibited metastases at the time of presentation for treatment. This is similar to the incidence of approximately 50% reported by Richards. The most common sites of metastases are the submaxillary lymph nodes.

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of carcinoma of the buccal mucosa is just as much of a problem as that of cancer in other areas of the oral cavity. In early cases, it is probable that similar results may be obtained by either surgery or X-ray radiation. The combined use of these two forms of treatment undoubtedly also has a place in the therapy of this tumor.

The prognosis of this neoplasm depends upon the presence or absence of metastases. The findings of Modlin and Johnson indicate that the five-year survival rate for patients with cancer of the buccal mucosa approximates 50%, but in another series Martin reported only a 28% survival.

Carcinoma of Gingiva

Carcinoma of the gingiva constitutes an extremely important group of neoplasms. The similarity of early cancerous lesions of the gingiva to common dental infections has frequently led to delay in diagnosis or even to misdiagnosis. Hence institution of treatment has been delayed, and the ultimate prognosis of the patient is poorer.

Martin reported that approximately 10% of all malignant tumors of the oral cavity occur on the gingiva. In the study of Krolls and Hoffman, 11% of the intraoral carcinomas occurred on the gingiva, while Tiecke and Bernier found a similar incidence of 12% in their series. In the group reported by Martin, one patient was only 22 years old, but the average age of the patients was 61 years. This is essentially a disease of elderly persons, since only 2% of the tumors occurred in patients under the age of 40 years. In the same group of patients, 82% were men and only 18% were women. This is similar to the gender distribution found in oral cancer in other locations.

Etiology

The etiology of carcinoma of the gingiva appears to be no more specific or defined than that in other areas of the oral cavity. Syphilis does not appear to be as significant a factor here as it is in carcinoma of the tongue, and the relation to the use of tobacco is indefinite. Since the gingiva, because of calculus formation and collection of microorganisms, is in nearly all persons the site of a chronic irritation and inflammation lasting over a period of many years, one may speculate the possible role of chronic irritation in the development of cancer of the gingiva. Occasionally, cases of gingival carcinoma appear to arise after extraction of a tooth. If such cases are carefully examined, however, it may usually be ascertained that the tooth was extracted because of a gingival lesion or disease or because the tooth was loose. In fact, the tooth was extracted because of the tumor, which, at the time of surgery, went unrecognized or undiagnosed.

An unusual situation arises in some instances after extraction of a tooth in that a carcinoma appears to develop rapidly and proliferate up out of the socket. Those cases which appear to represent such a phenomenon probably are due to carcinoma of the gingiva growing down along the periodontal ligament and then proliferating suddenly after the dental extraction.

Clinical Features

It is generally agreed that carcinoma of the mandibular gingiva is more common than the involvement of the maxillary gingiva, although the distribution of cases varies considerably between different series. In 47 cases reported by Tiecke and Bernier, 81% of the tumors were found on the mandibular gingiva and only 19% on the maxillary gingiva. Martin, however, reported a more equal distribution of 54% on the mandibular gingiva and 46% on the maxillary gingiva. Data on the exact position in the dental arch at which carcinoma is most apt to develop are insufficient to draw valid conclusions.

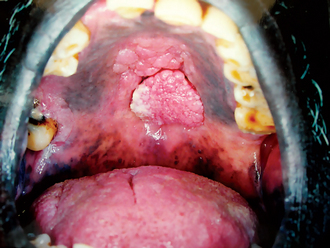

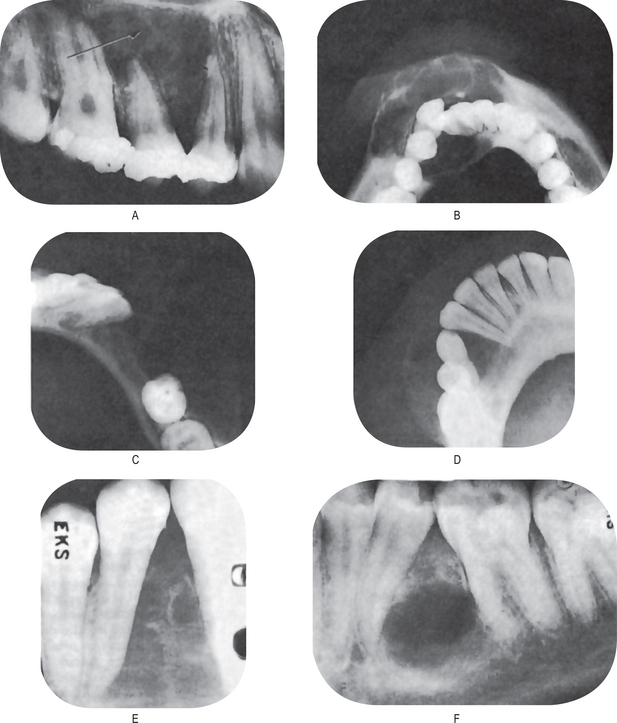

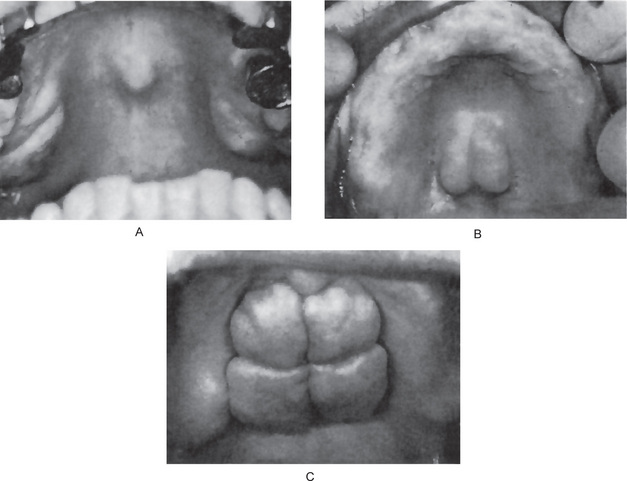

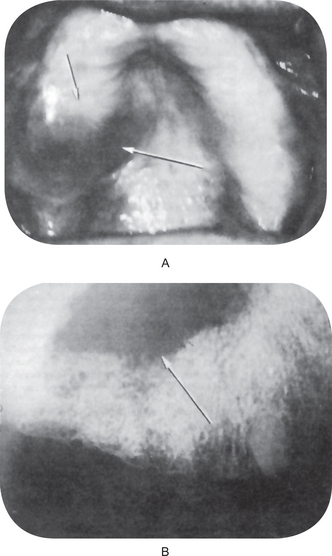

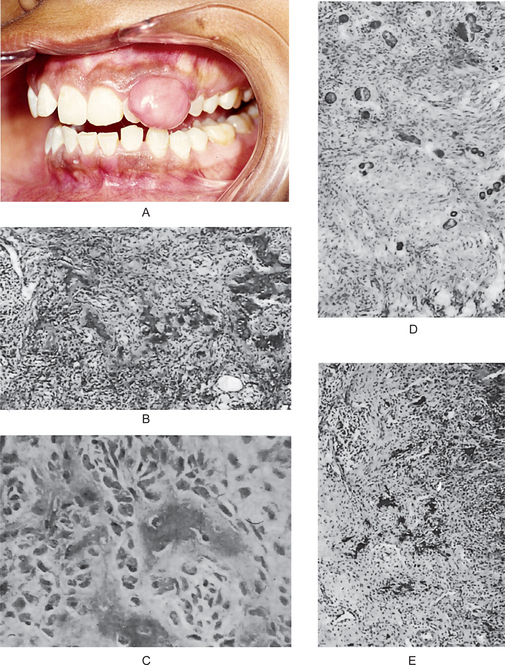

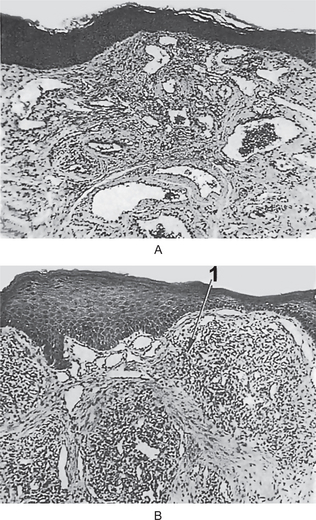

Carcinoma of the gingiva usually is manifested initially as an area of ulceration which may be a purely erosive lesion or may exhibit an exophytic, granular or verrucous type of growth (Fig. 2-29). Many times, carcinoma of the gingiva does not have the clinical appearance of a malignant neoplasm. It may or may not be painful. The tumor arises more commonly in edentulous areas, although it may develop in a site in which teeth are present. The fixed gingiva is more frequently involved primarily than the free gingiva.

Figure 2-29 Carcinoma of the gingiva. The mild overgrowth of the gingiva over the maxillary central incisors in this 25-year-old girl resembled inflammatory gingival hyperplasia. Microscopic examination of the gingivectomy specimen revealed epidermoid carcinoma. This is an unusual clinical appearance, age and location for this neoplasm, but many early cases are difficult to recognize (Courtesy of Harold R Schreiber and Charles A Waldron. J Periodontol, 29: 196, 1958).

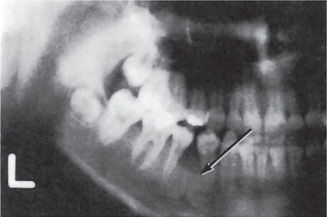

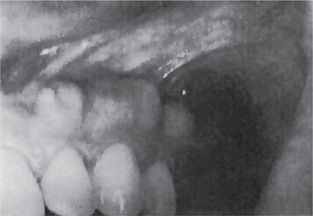

The proximity of the underlying periosteum and bone usually invites early invasion of these structures. Although many cases exhibit irregular invasion and infiltration of the bone, superficial erosion arising apparently as a pressure phenomenon sometimes occurs. In the maxilla, gingival carcinoma often invades into the maxillary sinus, or it may extend onto the palate or into the tonsillar pillar. In the mandible, extension into the floor of the mouth or laterally into the cheek as well as deep into the bone is rather common. Pathologic fracture sometimes occurs in the latter instance (Fig. 2-30).

Figure 2-30 Pathologic fracture of mandible caused by the invasion of epidermoid carcinoma arising on the alveolar ridge.

Metastasis is a common sequela of gingival carcinoma. Cancer of the mandibular gingiva metastasizes more frequently than cancer of the maxillary gingiva. In most series of cases, metastases to either the submaxillary or the cervical nodes eventually occur in over 50% of the patients regardless of whether the involvement is maxillary or mandibular.

Treatment and Prognosis

The use of X-ray radiation for carcinoma of the gingiva is fraught with hazards because of the well-known damaging effect of the X-rays on bone. In general, treatment of carcinoma in this location is a surgical problem.

The prognosis of cancer of the gingiva is not particularly good. In the series of 105 cases reported by Martin, only 26% of the patients were alive and free of the disease five years after treatment. It is of great significance that in this same series there were no five-year survivals if the patient presented lymph node metastases at the time of admission. This again illustrates the great need for early diagnosis of these neoplasms.

Carcinoma of Palate

Epidermoid carcinoma of the palate is not a particularly common lesion of the oral cavity. It exhibits approximately the same percentage of occurrence as carcinoma of the buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth and gingiva. The palate was the primary site of 9% of the intraoral epidermoid carcinomas reported by Krolls and Hoffman. In a study by Tiecke and Bernier, of 38 palatal tumors in which the site was specific, 53% occurred on the soft palate, 34% on the hard palate and 13% on both. Ackerman, however, stated that epidermoid carcinoma of the hard palate is a rare finding. New and Hallberg found an incidence of only 0.5% of cases of epidermoid carcinoma of the hard palate among approximately 5,000 cases of intraoral carcinoma. (Accessory salivary gland tumors of the hard palate appear to be three to four times more common than epidermoid carcinoma).

Clinical Features

Palatal cancer usually manifests itself as a poorly defined, ulcerated, painful lesion on one side of the midline (Fig. 2-31). It frequently crosses the midline, however, and may extend laterally to include the lingual gingiva or posteriorly to involve the tonsillar pillar or even the uvula. The tumor on the hard palate may invade into the bone or occasionally into the nasal cavity, while infiltrating lesions of the soft palate may extend into the nasopharynx.

The epidermoid carcinoma is almost invariably an ulcerated lesion, whereas the tumors of accessory salivary gland origin, even the malignant lesions, are often not ulcerated, but are covered with an intact mucosa. This fact may be of some aid in helping to distinguish clinically between these two types of neoplasms.

Metastases to regional lymph nodes occur in a considerable percentage of cases, but there is little evidence to indicate whether such metastases are more common in carcinoma of the soft palate or in that of the hard palate.

Treatment and Prognosis

Both surgery and X-ray radiation have been used in the treatment of epidermoid carcinoma of the palate. Few large series of cases are available for analysis to aid in determining which form of therapy may be expected to give the greatest survival. Nor are any significant series of purely palatal carcinomas available to aid in the determination of overall survival rate of patients with this lesion. It does appear that the prognosis is somewhat comparable to that of carcinoma of the gingiva.

Carcinoma of Maxillary Sinus

Antral carcinoma is an exceedingly dangerous disease. Although the actual incidence of the disease in respect to intraoral carcinoma cannot be determined, it does appear to be considerably less frequent than any other form of oral cancer. Seelig presented an excellent 10-year survey of the literature and described the chief findings in 624 cases of antral carcinoma; a review of this disease has also been reported by Chaudhry and his associates. Although nothing is known of the etiology of this particular neoplasm, Ackerman stated that chronic sinusitis does not seem to predispose to the development of carcinoma of the maxillary sinus. It might be pointed out here that, although most cases of carcinoma of the maxillary sinus are of the epidermoid type, occasional cases of adenocarcinoma occur, apparently originating from the glands in the wall of the sinus.

Clinical Features

One of the features which contribute to the deadly nature of this disease is that it is often hopelessly advanced before the patient is conscious of its presence. The dentist must be fully aware of the potentialities of this neoplasm and the various ways in which it may manifest itself clinically.

Available studies indicate that carcinoma of the antrum is somewhat more common in men and that, though it is chiefly a disease of elderly persons, occasional cases occur in young adults.

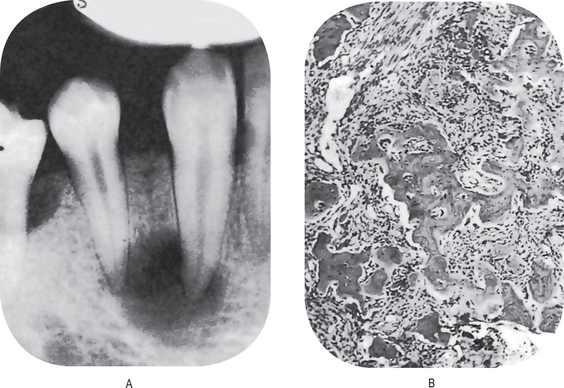

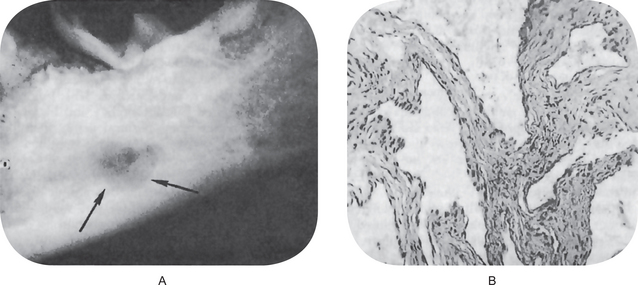

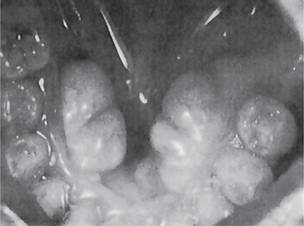

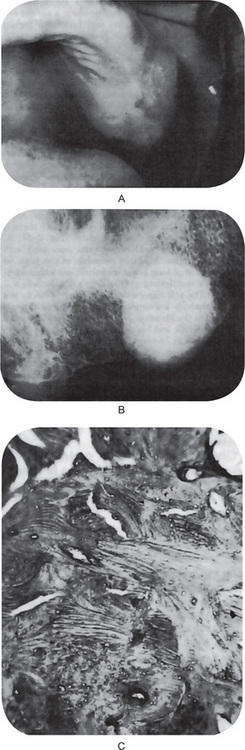

The first clinical sign of antral carcinoma is frequently a swelling or bulging of the maxillary alveolar ridge, palate or mucobuccal fold, loosening or elongation of the maxillary molars or swelling of the face inferior and lateral to the eye (Fig. 2-32). Unilateral nasal stuffiness or discharge is sometimes a primary complaint. In edentulous patients wearing maxillary dentures, loosening of or inability to tolerate the prosthetic appliance may occur before there is any visible clinical evidence of the disease.

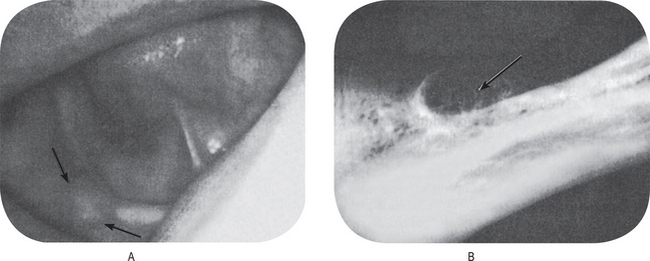

Figure 2-32 Epidermoid carcinoma of the maxillary sinus. (A) The alveolar ridge shows thickening, reddening and deformity, although there is no ulceration of the mucosa. (B) The radiograph reveals raggedness of the maxillary sinus and obvious bony alteration.

The actual spread of the neoplasm which determines the clinical manifestations of the disease is reflected by the extent of involvement of the various walls of the antrum. In some cases, only the floor of the sinus is invaded so that the manifestations of the disease are associated solely with oral structures. If the medial wall of the sinus is involved, nasal obstruction may result. The involvement of the superior wall or roof produces displacement of the eye, while invasion of the lateral wall produces bulging of the check. Ulceration either into the oral cavity or on the skin surface may occur, but only late in the course of the disease.

Metastases usually do not occur until the tumor is far advanced, but when they appear they involve the submaxillary and cervical lymph nodes. The lack of metastasis does not indicate a favorable course, since many patients die from local infiltration alone.

Treatment and Prognosis

Both surgery and X-ray radiation have been used to treat this form of neoplastic disease. If the cancer is confined to the antrum and inferior structures, hemimaxillectomy gives favorable clinical results in some cases. Radiation treatment frequently takes the form of radium needles inserted into the antrum or the tumor mass. This has proved effective in some cases, even though considerable invasion of adjacent structures has occurred.

The overall prognosis of patients with antral carcinoma is not good. In the series of Chaudhry and his associates, only 10% of 49 patients with carcinoma of the antrum lived for more than five years.

Verrucous Carcinoma

A warty variant of squamous cell carcinoma characterized by a predominantly exophytic overgrowth of well-differentiated keratinizing epithelium having minimal atypia and with locally destructive pushing margins at its interface with underlying connective tissue.

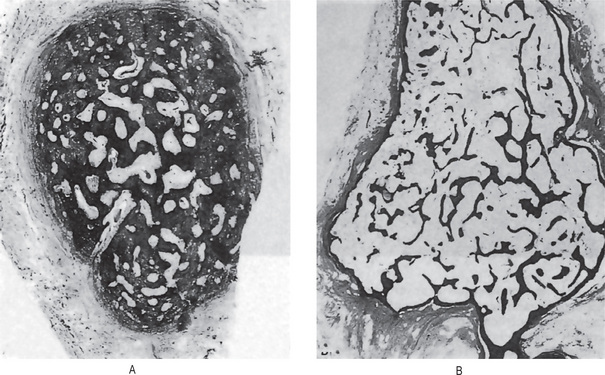

Verrucous carcinoma was originally described as a distinct entity on account of its clinical and microscopic features and its mode of behavior. Well differentiated, hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium is organized into bulbous rete-ridges that exhibit little or no cytological atypia or mitotic activity. There may be a significant endophytic component and the invading margin is usually below the level of the surrounding mucosa. Deep surface invaginations are filled with keratin. The advancing epithelial border is broad and the basement membrane is generally intact. There is usually a heavy inflammatory cell reaction in the adjacent connective tissue. Local destruction of connective tissue occurs in advance of the deep epithelial border. Growth is generally slow and metastatic spread occurs late, if at all. There is a view that verrucous carcinomas may become more aggressive if irradiated.

Although most verrucous carcinomas can be distinguished from squamous cell carcinomas on the basis of their mode of growth, infrequent dysplasia and absence of metastases, there are occasionally foci of conventional squamous cell carcinomas within a verrucous carcinoma. Such lesions should be classified and treated as squamous cell carcinomas. Thorough sectioning of specimens is therefore, necessary to eliminate this possibility. Another hazard in diagnosis occurs when the extremely thick layers of keratin and hyperplastic epithelium are biopsied at insufficient depth to include underlying connective tissue.

The term verrucous hyperplasia describes an exophytic overgrowth of well differentiated keratinizing epithelium that is similar to verrucous carcinoma but without the destructive pushing border at its interface with the underlying connective tissue. Areas of verrucous hyperplasia may be encountered in association with verrucous carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma or proliferative verrucous leukoplakia.

Exophytic papillary lesions that show epithelial dysplasia, possibly even carcinoma in situ, and relatively inconspicuous areas of invasive squamous cell carcinoma separate from the surface epithelium, should be distinguished from verrucous carcinomas and classified as papillary squamous cell carcinomas (Pindborg JJ et al, 1997).

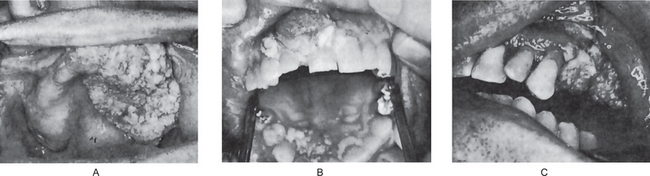

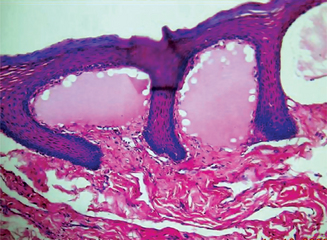

Clinical Features

Verrucous carcinoma is generally seen in elderly patients, the mean age of occurrence being 60–70 years, with nearly 75% of the lesions developing in males, according to a review by Shafer of nearly 300 reported cases. The vast majority of cases occur on the buccal mucosa and gingiva or alveolar ridge, although the palate and floor of the mouth are occasionally involved.

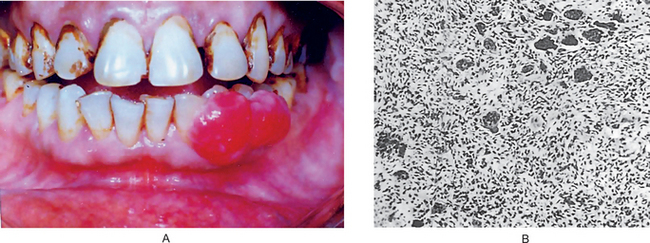

The neoplasm is chiefly exophytic and appears papillary in nature, with a pebbly surface which is sometimes covered by a white leukoplakic film. The lesions commonly have rugae-like folds with deep clefts between them. Lesions of the buccal mucosa may become quite extensive before the involvement of deeper contiguous structures. Lesions on the mandibular ridge or gingiva grow into the overlying soft tissue and rapidly become fixed to the periosteum, gradually invading and destroying the mandible (Fig. 2-33 A–C). Regional lymph nodes are often tender and enlarged, simulating metastatic tumor, but this node involvement is usually inflammatory. Pain and difficulty in mastication are common complaints, but bleeding is rare.

Figure 2-33 Verrucous carcinoma. The exophytic, verrucous nature of the lesion is evident (A and B, Courtesy of Dr Charles A Waldron, and C, of Dr George G Blozis and Dr Mirdza E Neiders).

The term oral florid papillomatosis has been used by dermatologists to describe a lesion with not only a clinical and microscopic appearance similar to verrucous carcinoma but also a similar biologic behavior. For this reason, many authorities now believe that oral florid papillomatosis and verrucous carcinoma represent one and the same disease with no justification for continued use of the former term, since it fails to imply the neoplastic nature of the disease.

It is consistently reported that a very high percentage of patients with this disease are tobacco chewers. A small number of patients give no such history but, instead, use snuff or smoke tobacco heavily. Occasional patients deny the use of tobacco and these usually have ill-fitting dentures.

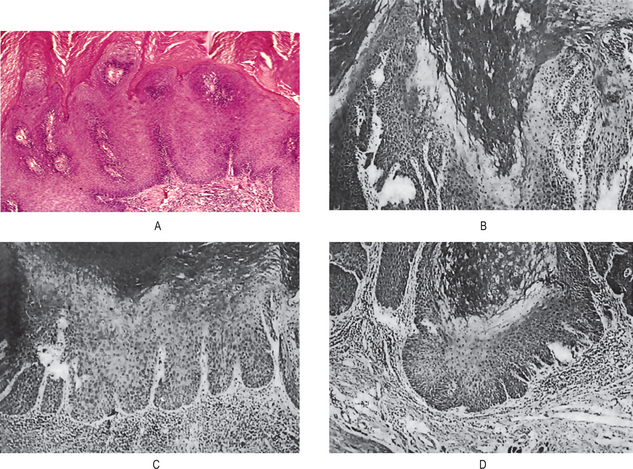

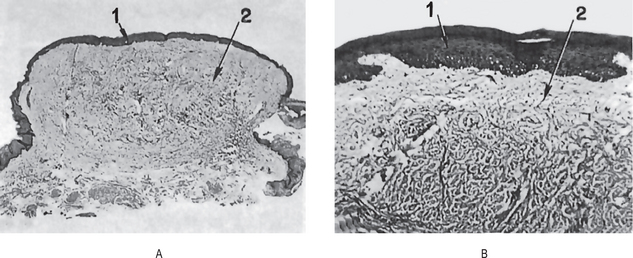

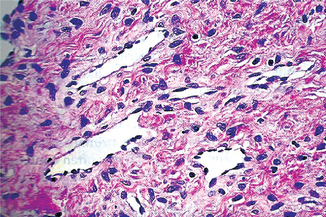

Histologic Features

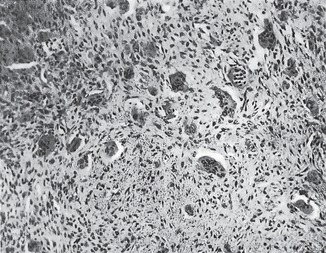

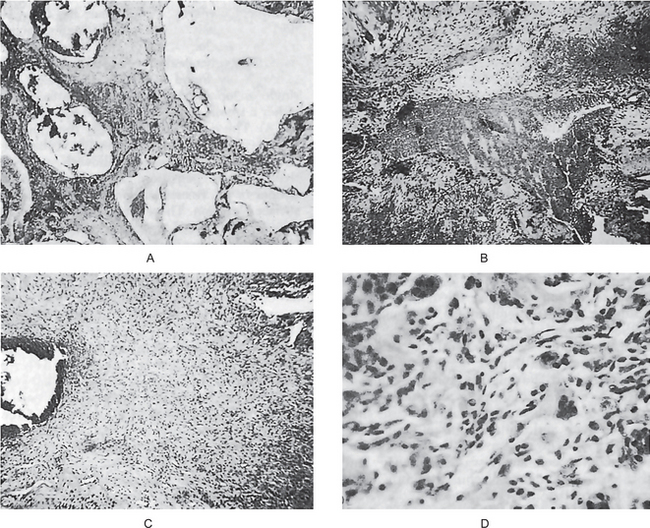

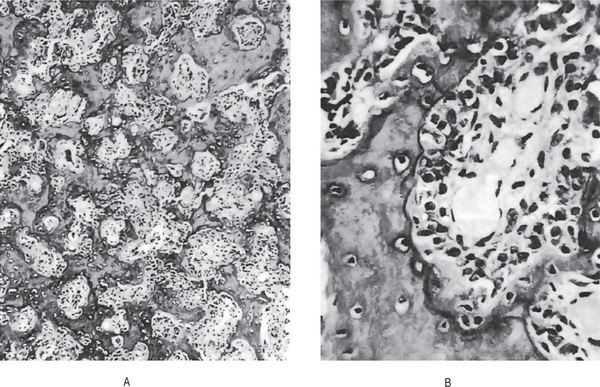

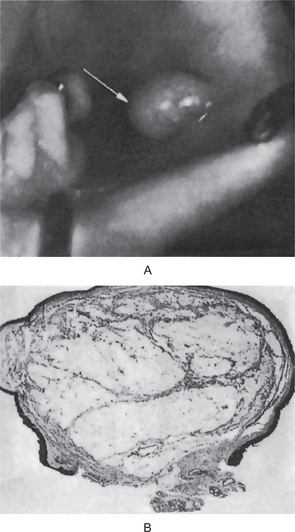

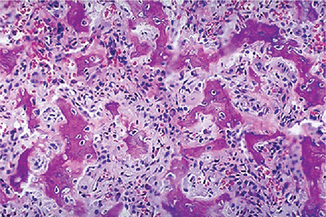

The histologic features may be extremely deceptive, and many cases have been diagnosed originally as simple papillomas or benign epithelial hyperplasia because of the orderly and harmless appearance of the specimen. There is generally marked epithelial proliferation with downgrowth of epithelium into the connective tissue but usually without a pattern of true invasion. The epithelium is well differentiated and shows little mitotic activity, pleomorphism or hyperchromatism. Characteristically, cleft like spaces lined by a thick layer of parakeratin extend from the surface deeply into the lesion. Parakeratin plugging also occurs extending into the epithelium. The parakeratin lining the clefts with the parakeratin plugging is the hallmark of verrucous carcinoma. Even though the lesion may be very extensive, the basement membrane will often appear intact. When the lesions become infected, focal intraepithelial abscesses are often seen. Significant chronic inflammatory cell infiltration in the underlying connective tissue may or may not be present (Fig. 2-34).

Figure 2-34 Verrucous carcinoma. The tumor is exophytic and has a papilliferous surface. It is composed of proliferating sheets and groups of stratified squamous epithelium, which exhibit few cytological features of malignancy. There is a round cell infiltrate in the fibrous tissue stroma. It may turn invasive at a later stage. (A, Courtesy of Dr Hari S, Noorul Islam College of Dental Science, Trivandrum)

Unfortunately, the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma is often difficult even when the biopsy specimen is generous, and the pathologist will sometimes request a second biopsy.

Treatment and Prognosis

Verrucous carcinoma has been treated in several ways in the past, usually by surgery, X-ray radiation or a combination of the two. However, there have been some reports of anaplastic transformation of lesions occurring in patients treated by ionizing radiation. While the radiation appears to be the triggering mechanism, other factors contributing to or related to the transformation are unknown. Even though such an occurrence is uncommon, many investigators believe the treatment should be entirely surgical. Since the lesion is so slow-growing and late to metastasize, many cases can be treated by relatively conservative excision without a mutilating procedure. The prognosis is much better than for the usual type of oral epidermoid carcinoma.

Spindle Cell Carcinoma (Carcinosarcoma, pseudosarcoma, polypoid squamous cell carcinoma, Lane tumor)

A carcinoma within which there are some elements resembling a squamous cell carcinoma that are associated with a spindle cell component.

In a true spindle cell carcinoma, the malignant spindle shaped cells should be demonstrably of epithelial origin and derived from the squamous cell component of the carcinoma. This must be distinguished both from a squamous cell carcinoma that has provoked a reactive fibroblastic stromal proliferation and from a carcinosarcoma in which a squamous cell carcinoma is accompanied by a sarcoma of fibroblastic or other connective tissue cell type. Care should also be taken not to confuse a spindle cell carcinoma with a spindle cell malignant melanoma or with sarcomas of various types. Often the squamous cell carcinoma component in a spindle cell carcinoma is inconspicuous and multiple sections or blocks may be necessary to find it. Most of the neoplasm comprises of thin elongated cells amongst which there may be occasional pleomorphic cells. Mitotic figures, including abnormal forms, are usually not difficult to find. The behavior is similar to that of the more frequent and usual type of squamous cell carcinoma (Pindborg JJ et al, 1997).

Clinical Features

A series of 59 cases of the oral cavity has been reported by Ellis and Corio, who noted a predilection for occurrence in males, although this finding was somewhat biased because of the number of military cases involved. The mean age of occurrence of the lesion was 57 years, with a range of 29–93 years. The lesions developed with the greatest frequency on the lower lip (42%), tongue (20%) and alveolar ridge or gingiva (19%) with the remainder scattered at other sites.

The most common presenting findings were swelling, pain and the presence of a nonhealing ulcer. The initial lesion appeared either with a polypoid, exophytic or endophytic configuration. It is perhaps significant that 13 patients in this series were known to have a history of prior therapeutic radiation to the region where the tumor subsequently developed. The time interval from radiation to diagnosis of the tumor ranged from 1.5–10 years with a mean of about seven years.

Histologic Features

Spindle cell carcinoma is a bimorphic or biphasic tumor which, although almost always ulcerated, will show foci of surface epidermoid carcinoma or epithelial dysplasia of surface mucosa, usually just at the periphery and often quite limited. Proliferation and ‘dropping-off ’ of basal cells to spindle cell elements is a common phenomenon. The tissue patterns making up the bulk of the tumor have been categorized as either fasciculated, myxomatous or streaming. The cells, particularly in the fasciculated form, are elongated with elliptical nuclei, although pleomorphic cells are also common. The number of mitoses may vary from few to many. Giant cells, both benign-appearing of the foreign body type and the bizarre, pleomorphic, atypical cells may be found. Finally, an inflammatory cell infiltrate is often present. Osteoid formation within the tumor component is sometimes seen. Microscopic invasion of subjacent structures is evident, as it is with most epidermoid carcinomas of the oral cavity.

Numerous ultrastructural studies of the spindle cell carcinoma, such as those of Leifer and his associates, have been carried out in clarification of the histogenesis and pathogenesis of this lesion.

Treatment and Prognosis

Surgical removal of the tumor, with or without radical neck dissection, alone or in combination with radiation, or radiation therapy alone all have been used in the treatment of this disease. In the series reported by Ellis and Corio, those treated by surgery had the best survival rate although only nine of 18 patients treated in this fashion were alive and well. Radiation therapy appears ineffective. The presence of metastasis signals a poor prognosis, since 81% of the patients with recorded metastases in this study died of their disease. The value of chemotherapy is not known.

Adenoid Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Adenoacanthoma, pseudoglandular squamous cell carcinoma)

A squamous cell carcinoma containing pseudoglandular spaces or lumina is an interesting tumor of the skin which also occurs with considerable frequency on the lips. It was originally described by Lever in 1947. This variant is produced as a result of acantholysis and degeneration within islands of a squamous cell carcinoma. The result is a pseudoadenocarcinomatous appearance, but there is no evidence of glandular differentiation or of secretory activity or products. There are insufficient reported cases to establish likely behavior.

Clinical Features

Adenoid squamous cell carcinoma is reported to occur as early as 20 years of age, although in the series of Johnson and Helwig, nearly 75% of the patients were 50 years of age or older. In their series, only 2% of the patients were females. Significantly, they found that 93% of the lesions were in the head and neck region.

The lesions on the skin appear as simply elevated nodules that may show crusting, scaling or ulceration. Sometimes there is an elevated or rolled border to the lesion.

A series of 15 cases of adenoid squamous cell carcinoma of the lips (11 lower, three upper, one unstated) has been reported by Jacoway and his associates, while Tomich and Hutton have reported two cases and discussed the lesion in detail. These lip lesions often appear clinically similar to epidermoid carcinoma, being described frequently as ulcerated, hyperkeratotic or exophytic.

There have been four cases of this lesion reported intraorally, two on the gingiva. The latter includes the first case reported from India by Sivapathasundharam B and Rohini S. However three of these lesions behaved in a very aggressive fashion, metastasized in at least two instances and the patient died in all three cases as a result of the tumor. Because of the aggressive nature of the lesions, these intraoral cases may not be identical to those of the skin and lips.

Histologic Features

There is a proliferation of surface dysplastic epithelium into the connective tissue as in the typical epidermoid carcinoma. However, the lateral or deep extensions of this epithelium show the characteristic solid and tubular ductal structures which typify the lesion. These duct like structures are lined by a layer of cuboidal cells and often contain or enclose acantholytic or dyskeratotic cells.

Treatment and Prognosis

The adenoid squamous cell carcinoma is generally treated by surgical excision. On only rare occasions does it metastasize or cause death of the patient. However, recurrence is relatively common (38% in the series of lip lesions reported by Jacoway and his coworkers, although it is possible that some of these may have been second lesions, since multiple adenoid squamous cell carcinomas in the same patient often occur).

Basaloid Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma is a form of carcinoma with a mixed composition of basaloid and squamous cells. This is a form of oral carcinoma in which the basaloid component comprises small cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm that are crowded together into lobulated sheets or strands focally connected to the surface epithelium. Cells at the periphery of the lobules are often palisaded; more centrally there may be cystic spaces, sometimes containing material resembling mucin, and focal squamous differentiation. Mitotic figures, including abnormal forms, and areas of necrosis are commonly seen. There is often hyalinization of the surrounding stroma and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration is variable. Confusion with ameloblastoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma is to be avoided; a focal squamous cell carcinoma component among the basaloid areas is the most important distinguishing feature. Most cases have been described in the larynx, hypopharynx and base of the tongue (Pindborg JJ et al, 1997).

Adenosquamous Carcinoma

A malignant tumor with histological features of both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. This tumor may arise from the ducts of minor salivary glands or from the overlying surface epithelium. The component identified as squamous cell carcinoma may be in situ or invasive, and the adenocarcinomatous component comprises glandular structures lined by basaloid, columnar or mucin-secreting cells. A distinction between adenosquamous carcinoma and high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma may be difficult, though in the former the glandular and squamous components are generally more distinct. Care must also be taken to distinguish adenosquamous carcinoma from adenoid squamous cell carcinoma (Pindborg JJ et al, 1997).

Undifferentiated Carcinoma

Undifferentiated carcinoma is carcinoma that lacks evidence of squamous, glandular or other types of differentiation. Accurate diagnosis is almost certainly dependent upon the use of adjunctive diagnostic techniques.

Lymphoepithelioma and Transitional Cell Carcinoma

There is an unusual group of malignant neoplasms exhibiting many features in common which involves nasopharynx, oropharynx, tongue, tonsil and anatomically associated structures such as the nasal chamber and paranasal sinuses. These tumors arise from the mucosa of these areas, exhibit a relatively specific histologic pattern and react in a rather atypical fashion to X-ray radiation. This group of neoplasms consists of the lymphoepithelioma, transitional cell carcinoma and undifferentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

Regaud, and later Schminke as well as Ewing, described the lymphoepithelioma as a lesion occurring chiefly in the nasopharynx of young or middle-aged persons. It was found to be usually a small lesion which often did not manifest itself clinically before regional lymphadenopathy was apparent. Death of the patient was the frequent outcome of the disease even though the lesion was found to be radiosensitive.

Under the term ‘transitional cell epidermoid carcinoma’, Quick and Cutler reported a series of cases in which the lesions arose chiefly from the tonsil, base of the tongue and nasopharynx. It is in these areas that a transitional type of stratified epithelium is found, the schneiderian membrane. These tumors, then, occurred in areas similar to the sites of the lymphoepithelioma. It was noted, however, that this transitional cell carcinoma was extremely malignant, running a rapid clinical course, metastasizing widely and causing very early death.

Clinical Features

The primary lesion of the lymphoepithe-lioma or transitional cell carcinoma is usually very small, often completely hidden, usually slightly elevated and either frankly ulcerated or presenting a granular, eroded surface. The tumor is indurated and, in some instances, appears as an exophytic or fungating growth. Since the primary lesion usually remains small, the patient may not seek advice until metastasis to the regional lymph nodes has already occurred.

Scofield carried out an excellent study of 214 cases of malignant nasopharyngeal lesions, comprising transitional cell carcinoma, lymphoepithelioma and undifferentiated squamous cell carcinoma. He found that swelling of the regional lymph nodes was the most common presenting symptom of the observed patients, followed by sore throat, nasal obstruction, defective hearing or ear pain, headache, dysphagia, epistaxis and ocular symptoms. Differences in the median age of the patients were found, patients with transitional cell carcinoma averaging 44 years of age, those with lymphoepithelioma averaging only 26 years and those with undifferentiated squamous cell carcinoma, 56 years. Bloom published a review of cancer of the nasopharynx with particular reference to the significance of the histopathology of the lesions.

Histologic Features

The diagnosis of these neoplasms and their differentiation depends solely upon their microscopic structure.

Transitional cell epidermoid carcinoma consists of cells growing in solid sheets or in cords and nests. The individual cells are moderately large, round or polyhedral, and exhibit a lightly basophilic cytoplasm and indistinct cell outlines. The nuclei appear large and round, and they exhibit varying degrees of mitotic activity. Although a slight degree of intercellular bridging may be present, keratinization and pearl formation are completely lacking. The stroma exhibits little or no lymphocytic infiltration.

The lymphoepithelioma is made up of cells growing in a syncytial pattern with the stroma infiltrated by varying numbers of lymphocytes. The individual cells are large and polyhedral with indistinct outlines. The cytoplasm stains lightly eosinophilic. The nuclei appear large, oval and vesicular, and characteristically contain one or two large eosinophilic nucleoli.

Treatment and Prognosis

Because of the general inacces-sibility of the majority of these lesions and their unusual property of being highly radiosensitive, X-ray radiation has been the most commonly accepted treatment. The response of this tumor to radiation is different from that of the epidermoid carcinoma found in these locations. Regional lymph node metastases also respond well to X-ray radiation. The complicating factor lies in the relative inability to treat the widespread metastases in the various organs.

The outlook for patients with these forms of neoplastic disease is poor. Since widespread metastases frequently occur before there is any clinical manifestation of disease, the unfavorable prognosis can be readily understood. In the series of Scofield the probability of five-year survival was calculated. He found that, after onset of symptoms, only 30% of treated patients suffering from transitional cell carcinoma or lymphoepithelioma would be alive in five years, while only 11% with squamous cell carcinoma in these areas would survive.

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

A tumor of the nasopharynx involving squamous epithelium, malignant in nature is widely prevalent in parts of south China (Cantonese) (98 per 100,000 of the population); where it is the commonest tumor in men and the second commonest in women. The tumor is rare in most parts of the world, though pockets occur in north and central Africa, Malaysia, Alaska, and Iceland. The most undifferentiated form of the tumor is always associated with EBV whereas the rarer, more differentiated forms are not consistently so. The evidence that EBV is involved in the pathogenesis is based on detection of multiple copies of the EBV genome can be detected in the malignant cells of 100% of undifferentiated NPC. All the malignant cells express EBNA-1. Furthermore, infectious EBV particles can be recovered from NPC cell lines. And also 100% of sera from undifferentiated NPC patients have high-titer antibodies to EB-viral antigens.

Clinical Features

NPC is a tumor proven to have a genetic background mainly restricted to southern China, with intermediate frequency in some Negro and Mongoloid races and rare in Caucasians. Studies have shown that first-generation immigrants from south China retain the high incidence of the disease, with the later generations showing a decline in incidence. This suggests that environmental as well as genetic factors are involved. NPC is especially associated with certain HLA haplotypes, e.g. HLA A2. More genetic linkage studies demonstrated the presence of NPC susceptibility genes near the MHC locus. Environmental factors are thought to play a role, particularly the consumption of salted fish and foods containing nitrosamines.

The EBV associated undifferentiated type arises mainly in younger patients whereas the more differentiated types occur in older patients and constitute the bulk of the sporadic cases. The tumor most commonly arises in the posterior wall of the nasopharynx in the fossa of Rosenmuller, where it often remains silent and metastasize to the local lymph nodes. The most common presentation of NPC is bilateral enlargement of the glands in the neck. The primary tumor may be very small and difficult to locate. Less frequently, the patient may present with the symptoms of invasion by the primary tumor, e.g. nasal obstruction, postnasal discharge, epistaxis, partial deafness and cranial nerve palsies. If untreated, the disease is rapidly fatal due to the development of laryngeal and pharyngeal obstruction.

Histologic Features

Three types of NPC are recognized on histological appearance:

Serum antibodies to EBV antigens can be used to confirm the diagnosis and monitor the progress of the disease.

Treatment

NPC is difficult to treat surgically because of the early metastasis to regional lymph nodes. The tumor is resistant to chemotherapy, and radiotherapy is the treatment of choice. However, because the tumor usually presents late, the prognosis is poor with a five-year survival rate of 20%. It may be possible to prevent the development of NPC with the use of an EBV vaccine at an early age.

Malignant Melanoma

Malignant melanoma is a neoplasm of epidermal melanocytes. It is one of the more biologically unpredictable and deadly of all human neoplasms. Although it is the third most common cancer of the skin (basal and squamous cell carcinomas are more prevalent), it accounts for only 3% of all such malignancies. However, it results in over 83% of all deaths due to skin cancer in the United States.

Cutaneous melanoma is increasing in incidence. The frequency of its occurrence is closely associated with the constitutive color of the skin, and depends on the geographical zone. Incidence among dark skinned ethnic groups is 1 per 100,000 per year or less, but among light-skinned Caucasians up to 50 and higher in some areas of the world. The highest incidence rates have been reported from Queensland, Australia with 56 new cases per year per 100,000 for men and 43 for women. In contrast, for Africans and Asians the annual incidence rate of malignant melanoma is only 0.2–0.4 per 100,000 population, affecting mainly the palms, soles, and mucous membranes. Cutaneous malignant melanoma is the most rapidly increasing cancer in whites. The annual increase in incidence rates has been estimated to be between 3 and 7%. These estimates suggest a doubling of rates every 10–20 years. These epidemiologic studies have supported the belief that sunlight is an important etiologic factor in cutaneous melanoma.

For many years, it was believed that many melanomas developed in preexisting pigmented nevi, particularly junctional nevi. However, Clark and his colleagues are of the opinion that junctional nevi are not histogenetically related to melanomas. It is quite possible that lesions which were interpreted as junctional nevi were, in fact, premalignant melanocytic dysplasias of some type, thus leading to the erroneous concept of malignant transformation of nevi. In support of this is a study by Jones and his colleagues in which 169 cases diagnosed as junctional nevi were studied retrospectively. Only 74 were actually junctional nevi, whereas 41 were actually melanomas in various phases of growth. The remainder were nevoid and non-nevoid pigmented lesions of various types. Melanomas may develop in or near a previously existing precursor lesion or in healthy-appearing skin. A malignant melanoma developing in healthy skin is said to arise de novo, without evidence of a precursor lesion. Certain lesions are considered to be precursor lesions of melanoma, including the common acquired nevus, dysplastic nevus, congenital nevus, and cellular blue nevus.

The following environmental and genetic factors are described in the etiology of malignant melanoma.

Environmental Factors

The highest incidence of melanoma has been reported from areas with long hours of sunlight throughout most of the year. Studies reported lower risk for melanoma among people who resided in a low ultraviolet environment in childhood compared with those who resided in a high UV environment. Intermittent exposure to high intensity UV seems to be more detrimental than continual exposure in its causation. Exposure in childhood appears to be particularly important. Recreational activity leading to sunburns in adulthood, such as sailing, has also been incriminated as an etiological factor.

Several case-control studies of melanoma risk and tanning lamp use have demonstrated a positive relation, suggesting that longer wave artificial UVA may play a part in the etiology of melanoma in addition to exposure to natural sunlight. The association of melanoma with PUVA (combination of psoralen (P) and long wave ultraviolet radiation (UVA)) therapy has also been reported. This topic is still controversial, though, and further studies are needed.

Several studies have reported that melanoma is more prevalent in those of high socioeconomic status. An explanation of this finding may be the fact that the latter can better afford holidays in areas of high UV intensity, as well as expensive outdoor hobbies like sailing, which increase the risk of melanoma due to intermittent intense sun exposure.

Genetic Factors

Between 2 and 5% of melanoma patients have a positive family history of melanoma in at least one first-degree relative. In approximately 30% of melanoma patients abnormalities on chromosome 9p21 are seen.

In this genetically determined disorder, defective DNA repair mechanisms lead to excessive chronic UV damage and subsequent development of different sun-related skin tumors, including melanoma, in sun-exposed areas.

Risk factors for oral mucosal melanomas are unknown. These melanomas have no apparent relationship to chemical, thermal, or physical events (e.g. smoking, alcohol intake, poor oral hygiene, irritation from teeth, dentures, or other oral appliances) to which the oral mucosa is constantly exposed. Although benign, intraoral melanocytic proliferations (nevi) occur and are potential sources of some oral melanomas; the sequence of events is poorly understood in the oral cavity. Currently, most oral melanomas are thought to arise de novo.

In 1975, Clark and his coworkers presented an interesting concept regarding the developmental biology of cutaneous melanoma. They documented two phases in the growth of melanoma: the radial-growth phase and the vertical-growth phase.

The radial-growth phase is the initial phase of growth of the tumor. During this period, which may last many years, the neoplastic process is confined to the epidermis. Neoplastic cells are shed with normally maturing epithelial cells and although some neoplastic cells may actually penetrate the basement membrane, they are destroyed by a host-cell immunologic response. The vertical-growth phase begins when neoplastic cells populate the underlying dermis. This takes place because of increased virulence of the neoplastic cells, a decreased host-cell response, or a combination of both. Metastasis is possible once the melanoma enters the vertical-growth phase. It is recognized that not all melanomas have both radial-and vertical-growth phases. Nodular melanoma (q.v.) exists only in the vertical-growth phase.

Cutaneous melanoma has been classified into a number of types. However, the most common types are: superficial spreading melanoma; nodular melanoma; lentigo maligna melanoma (Hutchinson’s freckle); and acral lentiginous melanoma.

Clinical Features

Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common cutaneous melanoma in Caucasians. It accounts for nearly 65% of cutaneous melanomas. It exists in a radial-growth phase which has been called premalignant melanosis or pagetoid melanoma in situ. The lesion presents as a tan, brown, black or admixed lesion on sun-exposed skin, especially the back. It also occurs on the skin of the head and neck, chest and abdomen and the extremities. The radial-growth phase may last for several months to several years. The vertical-growth phase is characterized by an increase in size, change in color, nodularity and, at times, ulceration.

Nodular melanoma accounts for approximately 13% of cutaneous melanomas. It apparently has no clinically recognizable radial-growth phase, existing solely in a vertical-growth phase. It presents as a sharply delineated nodule with varying degrees of pigmentation. They may be pink (amelanotic melanoma) or black. They have a predilection for occurrence on the skin of the back and head and neck skin of men. In other cutaneous sites, there is an even gender distribution.

Lentigo maligna melanoma accounts for approximately 10% of cutaneous melanomas. It exists in a radial-growth phase which is known as lentigo maligna or melanotic freckle of Hutchinson. The melanotic freckle has been recognized as a clinicopathologic entity for nearly 100 years. However, the concept that it represents a melanoma in a radial-growth phase is much more recent. The lesion occurs characteristically as a macular lesion on the malar skin of middle-aged and elderly Caucasians. It occurs more often in women than in men. In an extensive series of 85 cases, Wayte and Helwig found an average age of 58 years in men and 55 in women. In a series studied by Clark and his colleagues, the median age was 70 years. Both studies showed a female gender predilection. The lesion can remain in the radial-growth phase for years. In Wayte and Helwig’s study, the average duration in which an accurate history was possible was 14 years. Clark and Mihm have documented a lentigo maligna for 50 years prior to the development of a vertical-growth phase. Nearly 53% of the lesions evolved into lentigo maligna melanoma, the vertical-growth phase of this form of melanoma.

Melanoma may occur as a primary lesion not only on the skin but also in the eye and on mucous membranes. It has also been reported as a primary lesion in the parotid gland, although melanomas in this site are usually metastatic to lymph nodes in the parotid region.

Melanoma developing on the palms and soles, as well as on toes and fingers, represents only 10% of cases in whites, but over 50% of all melanomas on Black and Asian skin. The tumor is characterized by a macular, lentiginous pigmented area around a nodule. Mechanical stress may lead to erosion and ulceration. Subungual melanomas present as pigmentations of the nail bed and are often mistaken for subungual hematomas, and are thus commonly diagnosed at a late stage in development. They are extremely aggressive, with rapid progression from the radial to vertical growth phase.

Mucosal lentiginous melanomas develop from the mucosal epithelium that lines the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems. These lesions account for approximately 3% of the melanomas diagnosed annually and may occur on any mucosal surface, including the conjunctiva, oral cavity, esophagus, vagina, female urethra, penis, and anus. Noncutaneous melanomas are commonly diagnosed in patients of advanced age. When compared to cutaneous melanomas, mucosal lentiginous melanomas appear to have a more aggressive course, although this may be because they are commonly diagnosed at a later stage of disease than the more readily apparent cutaneous melanomas.

Amelanotic melanoma presents as an erythematous or pink, sometimes eroded, nodule. This tumor is often confused for other tumors, and only the histological examination provides the right diagnosis.

The following criteria aid clinical diagnosis of melanoma (ABCDE-rule):

• Asymmetry—in which one half does not match the other half

• Border irregularity—with blurred, notched, or ragged edges

• Color irregularity—pigmentation is not uniform. Brown black, tan, red, white, and blue—can all appear in a melanoma

• Diameter—greater than 6 mm. Growth in itself is also a sign

Oral Manifestations

Malignant melanoma is an uncommon neoplasm of the oral mucosa. Pliskin reviewed the literature on oral melanoma and found that they accounted for 1.6% of over 7,500 reported melanomas. Other authors have reported rates of 0.2–8%. Conley and Pack reported 26 cases of primary oral melanoma and McCaffrey, Neel and Gaffey reported on the 10 cases treated at the Mayo Clinic. Of epidemiologic interest is the fact that melanoma of the oral mucosa is one of the most common sites for the neoplasm in Japanese. Melanomas in Blacks are seldom found in the skin yet occur on mucous membranes and on the plantar skin.

Primary oral melanoma is nearly twice as common in men as in women. The overall age of occurrence is approximately 55 years, with most cases occurring between 40 and 70 years.

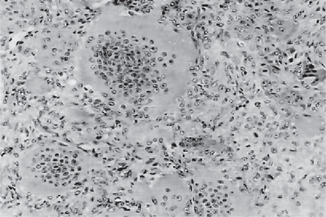

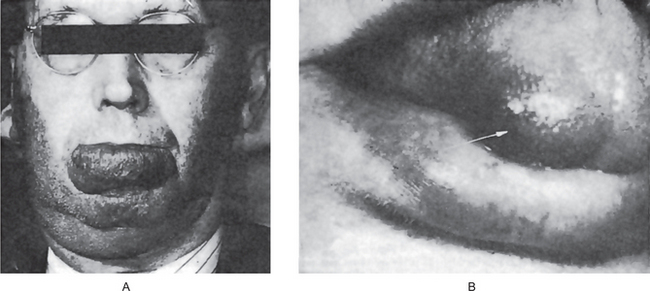

The oral melanoma exhibits a definite predilection for the palate and maxillary gingiva/alveolar ridge. Seventy-seven% of the cases in Pliskin’s review occurred in these two sites. Cases are also recorded on the buccal mucosa, mandibular gingiva, tongue, lips and floor of the mouth. The lesion usually appears as a deeply pigmented area, at times ulcerated and hemorrhagic, which tends to increase progressively in size (Fig. 2-35A–C). Amelanotic melanoma accounts for 5–35% of oral melanomas which appear as a white, mucosa-colored, or red mass.

Figure 2-35 Malignant melanoma. Typical lesions involve the plate (A) and (B), and the alveolar ridge (C) (Courtesy of Sivakumar G, Sivapathasundharam B, Karthiga KS. Malignant melanoma of the oral cavity–case reports and review of literature. Indian J Dent Res, 2004, 15(2): 70–73).

Significantly, focal pigmentation preceding the development of the actual neoplasm frequently occurred several months to several years before clinical symptoms appeared. For this reason it has been suggested that the appearance of melanin pigmentation in the mouth and its increase in size and in depth of color should be viewed seriously.

Although clinicopathologic correlation is well established for cutaneous melanomas, it is unfortunate that such correlation does not exist for oral melanomas. It is now apparent that melanomas of the oral mucosa can exist in radial-and vertical-growth phases but only a few such cases have been reported. Takagi and his coworkers were able to document a preexisting or concurrent melanosis in 62 of 94 cases of oral melanomas which they studied. Regezi, Hayward and Pickens evaluated three cases of oral melanoma in accordance with the established clinicopathologic parameters of cutaneous melanomas. They were able to classify one as a superficial spreading melanoma which had a preexisting melanosis for 11 years. The other two had histologic features consistent with lentigo maligna melanoma. However, since these lesions behaved much more aggressively, they were termed acral-lentiginous melanomas as suggested by Clark and his colleagues and by Reed.

Most dermatopathologists recognize the existence of lentigo maligna (melanotic freckle of Hutchinson) only on sun-damaged skin and do not accept its occurrence intraorally. It follows that lentigo maligna melanoma (melanoma arising in melanotic freckle of Hutchinson) cannot occur on oral mucosa, although such a case has been reported by Robinson and Hukill. In light of present knowledge, such a case would be called acral-lentiginous melanoma because of the clinicopathologic similarity of the oral lesion to those on palmar and plantar skin (Table 2-11).

Table 2-11

Differential diagnosis for melanoma

| Condition | Distinguishing characteristics |

| Seborrheic keratosis | “Stuck-on” appearance, symmetric, often multiple |

| Traumatized or irritated nevus | Returns to normal appearance within 7–14 days |

| Pigmented basal cell carcinoma | Waxy appearance, telangiectasias |

| Lentigo | Prevalent in sun-exposed skin, evenly pigmented, symmetric |

| Blue nevus | Darkly pigmented from dermal melanocytes, no history of change from melanoma |

| Angiokeratoma | Vascular tumors, difficult to distinguish |

| Traumatic hematoma | May mimic melanoma but resolves in 7–14 days |

| Venous lake | Blue, compressible, found on ears and lips |

| Hemangioma | Compressible, stable |

| Dermatofibroma | Firm growths of fibrous histiocytes, ‘button-hole’ when pinched |

| Pigmented actinic keratosis | Sandpapery feel; sun-exposed area |

Source: Beth G Goldstein, and Adam O Goldstein. American Academy of Family Physicians, News and Publications, 2001.

Thus, oral melanomas may be expected to exist in superficial spreading, acral-lentiginous and nodular types. Batsakis and his associates and Hansen and Buchner have recently discussed the current concepts of oral mucosal melanomas relative to their cutaneous counterparts.

Histologic Features

The malignant cells often nest or cluster in groups in an organoid fashion; however, single cells can predominate. The melanoma cells have large nuclei, often with prominent nucleoli, and show nuclear pseudoinclusions due to nuclear membrane irregularity. The abundant cytoplasm may be uniformly eosinophilic or optically clear. Occasionally, the cells become spindled or neurotized in areas. This finding is interpreted as a more aggressive feature, compared with findings of the round or polygonal cell varieties.

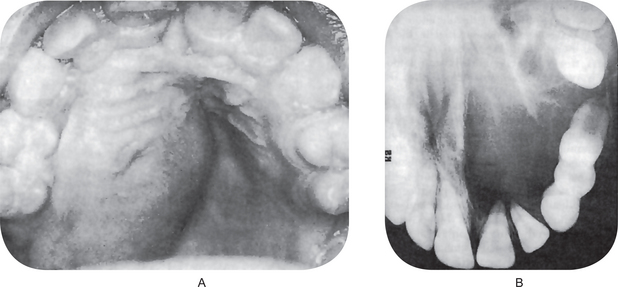

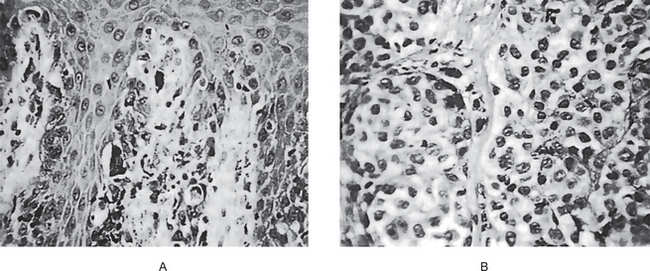

The intraepithelial component (radial-growth phase) of superficial spreading melanoma is characterized by the presence of large, epithelioid melanocytes distributed in a so-called ‘pagetoid’ manner (Figs. 2-36, 2-37 A). This pagetoid spread within the epidermis is sometimes known as ‘buckshot scatter’. As long as the malignant cells are confined to the epithelium, there is no host-cell response in the underlying connective tissue. When melanocytes penetrate basement membrane, a florid host-cell response of lymphocytes develops. Macrophages and melanophages may be present. The tumor cells are often destroyed by this cellular response. The vertical-growth phase is characterized by the proliferation of malignant epithelioid melanocytes in the underlying connective tissues (Fig. 2-37 B). The cells may be arranged singly or in clusters. Melanin pigment is usually scanty.

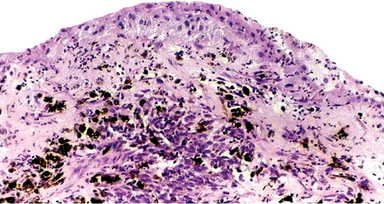

Figure 2-36 Vertical growth phase characterized by malignant melanocytes invading the underlying connective tissue (Courtesy of Dr Hari S, Noorul Islam College of Dental Science, Trivandrum).

Figure 2-37 Malignant melanoma. (A) The radial-growth phase or premalignant melanosis is characterized by atypical melanocytes within the epithelium. (B) The vertical-growth phase is characterized by malignant epithelioid melanocytes invading the underlying connective tissue.

Nodular melanoma also is characterized by large, epithelioid melanocytes within the connective tissue. However, small ovoid and spindle-shaped cells may be present. Melanin pigment is usually but not invariably present. The tumor cells may invade and ulcerate the overlying epithelium and penetrate the deep soft tissues.