Tumors of the Salivary Glands

Tumors of the salivary glands constitute a heterogeneous group of lesions of great morphologic variation, and for this reason, present many difficulties in classification. Since these tumors are relatively uncommon, early investigators were handicapped by insufficient material for study. With the publication of several large series of cases, accompanied by serious discussions of the nature of tumors of the salivary glands based upon a cumulative clinical experience of many years, considerable progress has been made in broadening our knowledge of these lesions. Among these studies have been those of Evans and Cruickshank, Thackray and Lucas, and WHO.

Foote and Frazell were among the first investigators to provide a usable classification of salivary gland tumors. Spiro and his associates, Thackray and Sobin, and Batsakis have proposed classifications for practical use that are based on clinical behavior or specific histologic criteria. However, Eversole has proposed a histogenetic classification of salivary gland tumors, implicating two cell types as possible progenitors: the intercalated duct cell and the excretory duct reserve cell. The various types of salivary gland tumors are best distinguished by their histologic patterns. The clinical behavior of these various lesions may be based, as in most tumors, on the type of tumor as well as on the method of treatment utilized.

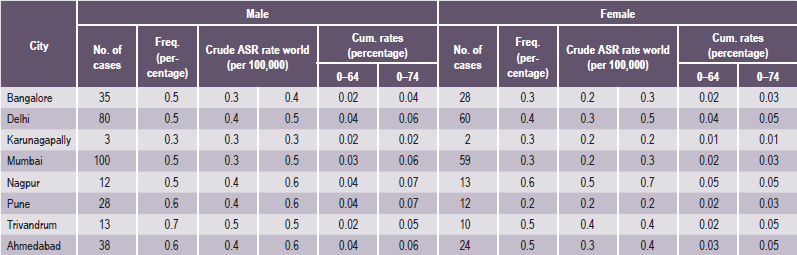

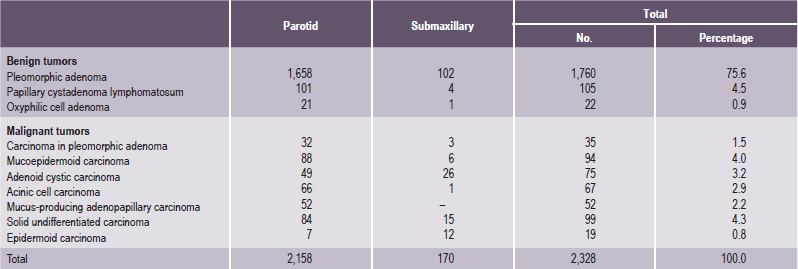

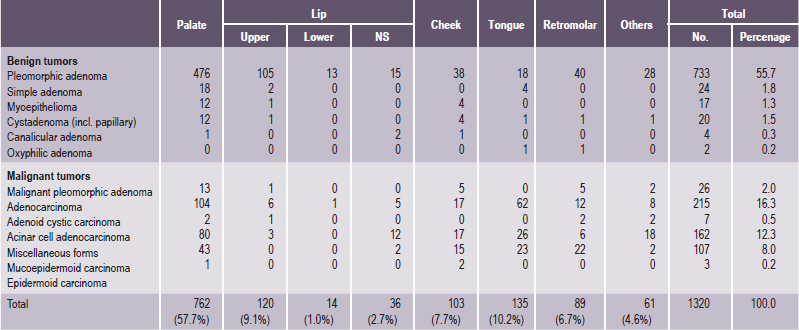

It is important to recognize that neoplasms may arise not only from the major salivary glands, but also from any of the numerous, diffuse, intraoral accessory salivary glands. Thus one may expect to see tumors originating from the glands in the lip, palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth and retromolar area. Salivary gland tumors are much more common on the hard palate than on the soft, probably because there are a greater number of gland aggregates on the hard palate than on the soft palate. With only occasional exceptions, any type of tumor which occurs in a major salivary gland may also arise in an intraoral accessory gland. Thus, in the following discussion, the general features described under each tumor will hold true for both major and minor salivary gland lesions. There appear to be no truly specific, recognized tumors native only to the intraoral glands. Annual incidence of salivary gland tumors around the world is stated to be 1–6.5 cases per 100,000 people. Most studies have shown that minor salivary gland tumors are more common in females than males, with a ratio range from 1.2 : 1–1.9 : 1. Eneroth has presented data on over 2,300 tumors of the major salivary glands (Table 3-1), while a complete review of the intraoral minor salivary gland tumors has been published by Chaudhry and his coworkers, with much valuable information obtained from the analysis of over 1,300 cases (Table 3-2).

Table 3-1

Occurrence of major salivary gland tumors

Data from CM Eneroth: Salivary gland tumors in the parotid gland, submandibular gland and the palate region. Cancer, 27: 1415, 1971.

Table 3-2

Occurrence of intraoral accessory salivary gland tumors

Data from AP Chaudhry, RA Vickers, and RJ Gorlin: Intraoral minor salivary gland tumors. Oral Surg, 14: 1194, 1961.

Benign tumors of the salivary gland need no treatment other than surgical removal. Malignant tumors, on the other hand, may require radiation or chemotherapy or both after surgery. Surgery for salivary gland tumors removes all or most of the affected glands, not just the tumor. When performing surgery on these glands, great care is taken to identify and protect the nerves that pass through or near these glands and supply the muscles of the face, mouth and tongue. These nerves are stretched during surgery, which results in a temporary weakness on part of the face in up to 15% of patients. This weakness is temporary and usually disappears in one to three months. Occasionally, malignant tumors invade the nerves that supply part or all of the muscles of the face. When this occurs, a portion of the nerve is surgically removed with the tumor, and a nerve graft is used to rebuild the nerve.

Benign Tumors of the Salivary Glands

Pleomorphic Adenoma (Mixed tumor)

Pleomorphic adenoma is a benign neoplasm consisting of cells exhibiting the ability to differentiate to epithelial (ductal and nonductal) cells and mesenchymal (chondroid, myxoid and osseous) cells. This tumor has been referred to by a great variety of names through the years (e.g. mixed tumor, enclavoma, branchioma, endothelioma, enchondroma), but the term ‘pleomorphic adenoma’ suggested by Willis characterizes closely the unusual histologic pattern of the lesion. It is almost universally agreed that this tumor is not a ‘mixed’ tumor in the true sense of being teratomatous or derived from more than one primary tissue. Its morphologic complexity is the result of the differentiation of the tumor cells, and the fibrous, hyalinized, myxoid, chondroid and even osseous areas are the result of metaplasia or are actually products of the tumor cells per se. Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common salivary gland tumor (Table 3-3).

Table 3-3

Histological classification of salivary gland tumors (WHO 1991)

1. Adenomas

• Pleomorphic adenoma

• Myoepithelioma (myoepithelial adenoma)

• Basal cell adenoma

• Warthin’s tumor (adenolymphoma)

• Oncocytoma (oncocytic adenoma)

• Canalicular adenoma

• Sebaceous adenoma

• Ductal papilloma

▫ Inverted ductal papilloma

▫ Intraductal papilloma

▫ Sialadenoma papilliferum

• Cystadenoma

▫ Papillary cystadenoma

▫ Mucinous cystadenoma

2. Carcinomas

• Acinic cell carcinoma

• Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

• Adenoid cystic carcinoma

• Polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma (terminal duct adenocarcinoma)

• Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma

• Basal cell adenocarcinoma

• Sebaceous carcinoma

• Papillary cystadenocarcinoma

• Mucinous adenocarcinoma

• Oncocytic carcinoma

• Salivary duct carcinoma

• Adenocarcinoma

• Malignant myoepithelioma (myoepithelial carcinoma)

• Carcinoma in pleomorphic adenoma (malignant mixed tumor)

• Squamous cell carcinoma

• Small cell carcinoma

• Undifferentiated carcinoma

• Other carcinomas

3. Nonepithelial tumors

4. Malignant lymphomas

5. Secondary tumors

6. Unclassified tumors

7. Tumor like lesions

• Sialadenosis

• Oncocytosis

• Necrotizing sialometaplasia (salivary gland infarction)

• Benign lymphoepithelial lesion

• Salivary gland cysts

• Chronic sclerosing sialadenitis of submandibular gland (Küttner tumor)

• Cystic lymphoid hyperplasia in AIDS

Adapted from: Seifert G. Histological typing of salivary gland tumors, 2nd ed. Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1991.

Histogenesis

Numerous theories have been advanced in explaining the histogenesis of this bizarre tumor. Currently, these center around the myoepithelial cell and a reserve cell in the intercalated duct. Ultrastru ctural studies have confirmed the presence of both ductal and myoepithelial cells in pleomorphic adenomas. It follows that possibly either or both may play active roles in the histogenesis of the tumor. Hubner and his associates have postulated that the myoepithelial cell is responsible for the morphologic diversity of the tumor, including the production of the fibrous, mucinous, chondroid and osseous areas. Regezi and Batsakis postulated that the intercalated duct reserve cell can differentiate into ductal and myoepithelial cells and the latter, in turn, can undergo mesenchymal metaplasia, since they inherently have smooth muscle like properties. Further differentiation into other mesenchymal cells then can occur. Batsakis has discussed salivary gland tumorigenesis, and while still implicating the intercalated duct reserve cell as the histogenetic precursor of the pleomorphic adenoma, stated that the role of the myoepithelial cell is still uncertain and that it may be either an active or passive participant histogenetically. Finally, Dardick and his associates have questioned the role of both ductal reserve and myoepithelial cells. They state that a neoplastically altered epithelial cell with the potential for multidirectional differentiation may be histogenetically responsible for the pleomorphic adenoma.

Pleomorphic adenomas have shown consistent cytogenetic abnormalities, chiefly involving the chromosome region 12q13-15. The putative pleomorphic adenoma gene (PLAG1) has been mapped to chromosome 8q12. Many other genes have also been implicated; however, cytogenetic or molecular studies do not as yet have an established role in the diagnosis of pleomorphic adenoma.

Clinical Features

Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common tumor of salivary glands. The parotid gland is the most common site of the pleomorphic adenoma; 90% of a group of nearly 1,900 such tumors reported by Eneroth. It may occur in any of the major glands or in the widely distributed intraoral accessory salivary glands; however its occurrence in the sublingual gland is rare. In the parotid this tumor most often presents in the lower pole of the superficial lobe of the gland, about 10% of the tumors arise in the deeper portions of the gland. Approximately 8% of pleomorphic adenomas involve the minor salivary glands, the palate is the most common site (60–65%) of minor salivary gland involvement. It occurs more frequently in females than in males, the ratio approximating 6 : 4. The majority of the lesions are found in patients in the fourth to sixth decades with the average age of occurrence of about 43 years, but they are also relatively common in young adults and have been known to occur in children. The clinical behavior of this tumor in children is similar to that in adults (Table 3-4).

Table 3-4

TNM/AJCC 1997 staging (clinical staging)

TX: primary tumor cannot be assessed

• T0: No evidence of primary tumor

• T1: Tumor 2 cm or less in greatest dimension without extraparenchymal extension*

• T2: Tumor > 2 cm but < 4 cm in greatest dimension without extraparenchymal extension*

• T3: Tumor having extraparenchymal extension* without seventh nerve involvement and/or more than 4 cm but no more than 6 cm in greatest dimension

• T4: Tumor invades base of skull, seventh nerve, and/or exceeds 6 cm in greatest Dimension

• N0: No regional node metastasis

• Nx: Regional nodes cannot be assessed

• N1: Single ipsilateral node, < 3 cm

• N2a: Single ipsilateral node, > 3 cm and < 6 cm

• N2b: Multiple ipsilateral nodes, < 6 cm

• N2c: Contralateral or bilateral nodes, < 6 cm

• N3: Node > 6 cm

• MO: No distant metastasis

• Mx: Metastasis cannot be assessed

Minor salivary gland tumors are staged according to their site of origin.

Microscopic evidence alone does not constitute extraparenchymal extension for classification purpose.

*Extraparenchymal extension is clinical or macroscopic evidence of invasion of skin, soft tissues, bone or nerve.

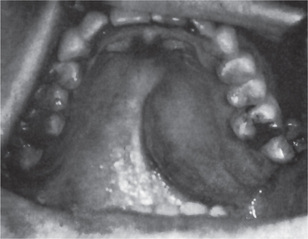

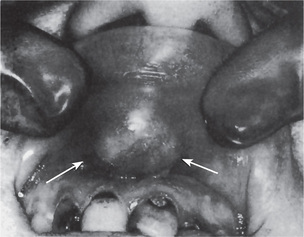

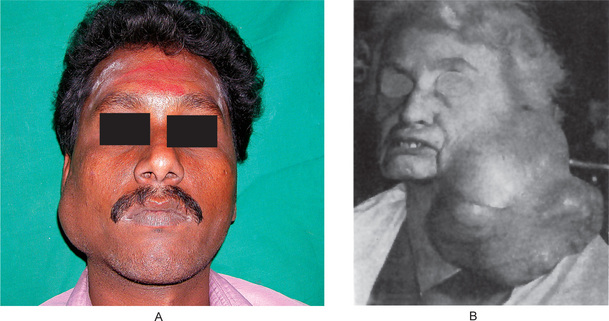

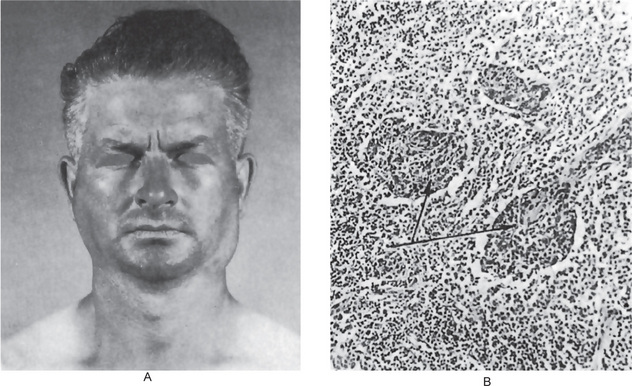

The history presented by the patient is usually that of a small, painless, quiescent nodule which slowly begins to increase in size, sometimes showing intermittent growth (Fig. 3-1). The pleomorphic adenoma, particularly of the parotid gland, is typically a lesion that does not show fixation either to the deeper tissues or to the overlying skin (Fig. 3-2 A). It is usually an irregular nodular lesion which is firm in consistency, although areas of cystic degeneration may sometimes be palpated if they are superficial. The skin seldom ulcerates even though these tumors may reach a fantastic size, lesions having been recorded which weighed several kilograms (Fig. 3-2 B). Pain is not a common symptom of the pleomorphic adenoma, but local discomfort is frequently present. Facial nerve involvement manifested by facial paralysis is rare.

Figure 3-2 Pleomorphic adenoma of parotid gland.

(A) Typical appearance of pleomorphic adenoma of parotid gland. (B) The lesion here is used not to illustrate the usual clinical appearance of a pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland, but to demonstrate the size which these tumors may attain. This lesion was present for eighteen years A, Courtesy of Dr Neelakandan RS, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College, Chennai.

The pleomorphic adenoma of intraoral accessory glands seldom is allowed to attain a size greater than 1–2 cm in diameter. Because this tumor causes the patient difficulties in mastication, talking and breathing, it is detected and treated earlier than tumors of the major glands. The palatal glands are frequently the site of origin of tumors of this type (Fig. 3-3), as are the glands of the lip (Fig. 3-4) and occasionally other sites. Except for size, the intraoral tumor does not differ remarkably from its counterpart in a major gland. The palatal pleomorphic adenoma may appear fixed to the underlying bone, but is not invasive. In other sites the tumor is usually freely movable and easily palpated. Recurrent lesions, however, occur as multiple nodules and are less mobile than the original tumor (Table 3-5).

Histologic Features

The mixed tumors generally appear as an irregular to ovoid mass with well-defined borders. The tumors in major glands have either an incomplete fibrous capsule or are unencapsulated whereas in the minor glands they are unencapsulated. The cut surface may be rubbery, fleshy, mucoid or glistening with a homogeneous tan or white color. Areas of hemorrhage and infarction may be noted occasionally.

Morphologic diversity is the most characteristic feature of this neoplasm. Microscopically, benign mixed tumors are characterized by variable, diverse, structural histologic patterns, seldom do individual cases resemble each other, considerable variation is also seen within a single tumor. Pleomorphic adenomas demonstrate combinations of glandular epithelium and mesenchyme like tissue and the proportion of each component varies widely among individual tumors. Foote and Frazell (1954) categorized the tumor into the following types:

Table 3-6

Typical features of benign and malignant salivary gland tumors

| Benign salivary gland tumors | Malignant salivary gland tumors |

| • Slow growing | • Sometimes fast growing |

| • Soft or rubbery consistency | • Sometimes hard consistency |

| • 85% of parotid tumors are benign | • 45% of minor glands are malignant |

| • Do not ulcerate | • May ulcerate and invade bone |

| • No associated nerve signs | • May cause cranial nerve palsies (e.g. parotid tumor causes facial palsy, adenoid cystic carcinoma can cause multiple nerve lesions especially of lingual, facial or hypoglossal nerves) |

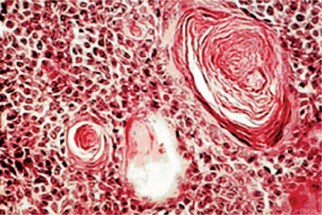

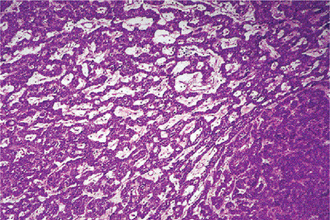

The epithelial component forms ducts and small cysts that may contain an eosinophilic coagulum, the epithelium may also occur as small cellular nests, sheets of cells, anastomosing cords and foci of keratinizing squamous or spindle cells. Myoepithelial cells are a major component of pleomorphic adenoma. They have a variable morphology, sometimes appearing as angular or spindled, while some cells are more rounded with eccentric nuclei and hyalinized eosinophilic cytoplasm resembling plasma cells (earlier referred to as hyaline cells) (Fig. 3-5). Myoepithelial-cells are also responsible for the characteristic mesenchyme like changes; these changes are brought about by extensive accumulation of mucoid material around individual myoepithelial cells giving a myxoid appearance. Vacuolar degeneration of these myoepithelial cells then results in a cartilaginous appearance (Fig. 3-6). Foci of hyalinization, bone and even fat can be noted in the connective tissue stroma of many tumors. When the pleomorphic pattern of the stroma is absent, and the tumor is highly cellular, it is often referred to as a ‘cellular adenoma’. When myoepithelial proliferation predominates, the diagnosis of ‘myoepithelioma’ (q.v.) is generally made.

Treatment and Prognosis

The accepted treatment for this tumor is surgical excision. The intraoral lesions can be treated somewhat more conservatively by extracapsular excision. Since these tumors are radioresistant, the use of radiation therapy is of little benefit and is therefore contraindicated.

Rarely, a malignant tumor may arise within this tumor, a phenomenon known as carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. There is a second class of tumors which are called metastasizing benign mixed tumors. These tumors have a histologically benign appearance but usually have a history of multiple local recurrences. Metastases occur several years after the initial diagnosis and may occur to the lungs, regional lymph nodes, skin, and bone. The usual clinical course is good but there are cases which have an aggressive clinical course leading to death in 22% of cases. Fortunately this last category of tumors is very rare.

Myoepithelioma: (Myoepithelial adenoma)

The term myoepithelioma was first used by Sheldon in 1943. The myoepithelioma is an uncommon salivary gland tumor which accounts for less than 1% of all major and minor salivary tumors. Nonetheless, it is important in that the component cell constitutes a prominent place in salivary gland neoplasia. Many authorities, including Batsakis, consider the myoepithelioma to be a ‘one-sided’ variant at the opposite end of the spectrum from the pleomorphic adenoma.

Clinical Features

There are no clinical features which can serve to separate the myoepithelioma from the more common pleomorphic adenoma. It occurs in adults with an equal gender distribution. The parotid gland is most commonly involved and the palate is the most frequent intraoral site of occurrence. Sciubba and Brannon reported lesions in the retromolar glands and the upper lip.

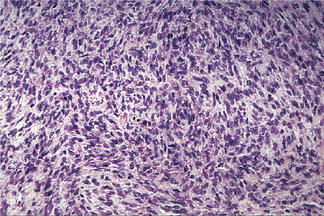

Histologic Features

The tumor is composed exclusively, or almost exclusively, of neoplastic myoepithelial cells. The neoplastic cells are predominantly spindle-shaped or plasma-cytoid. Epithelioid or clear cells may also be present (Figs. 3-7, 3-8). Either a single cell type predominates in a tumor or there may be a combination of cell types. The tumor is often difficult to diagnose definitively at the light microscopic level. Myoep-ithelioma does not contain the characteristic chondromyxoid stroma of pleomorphic adenoma. Myoepithelioma consisting predominantly of spindle cells tends to be more cellular than the tumor consisting of predominantly plasmacytoid cells. Definitive diagnosis lies in the ultrastructural identification of myoepithelial cells. The myoepithelial cell exhibits a basal lamina and fine intracytoplasmic myofilaments. Desmosomes are encountered between adjacent cells.

Basal Cell Adenoma

Basal cell adenoma is a neoplasm of a uniform population of basaloid epithelial cells arranged in solid, trabecular, tubular, or membranous patterns. The basal cell adenoma was first reported as distinct entity by Kleinsasser and Klein in 1967. Batsakis is credited with reporting the first case in the American literature in 1972, and suggested that the intercalated duct or reserve cell is the histogenetic source of the basal cell adenoma.

Clinical Features

Basal cell adenomas tend to occur primarily in the major salivary glands, particularly the parotid gland. In the series reported by Batsakis and associates, 48 of 50 tumors were in the parotid gland and two were in the submaxillary gland. The tumors are usually painless and are characterized by slow growth. They occur chiefly in adults, the average age of the patients is 57.7 years with the peak of incidence seen in the sixth decade. However, the tumor can occur in younger persons, Canalis and his coworkers reported a basal cell adenoma in the submaxillary gland of a newborn male. There is a 2 : 1 female predilection for the occurrence of this tumor. These tumors appear as a firm swelling which may be cystic and compressible. These tumors are clinically indistinguishable from mixed tumors and their greatest dimension is usually less than 3 cm.

Histologic Features

Basal cell adenoma occurs as a single well-defined nodule, the membranous type may be multifocal. Tumors in major salivary gland have a well defined capsule, whereas intraoral tumors are less well defined. The cut surface often is homogeneous with gray to brown in color, and may have cystic areas.

The basal cells that make up this lesion are fairly uniform and regular; two morphologic forms can be seen. One is a small cell with scanty cytoplasm and round deeply basophilic nucleus. The other cell is large with eosinophilic cytoplasm and an ovoid pale staining nucleus. Basal cell adenomas can be divided on the basis of their morphologic appearances into four subtypes:

The most common type of basal cell adenoma is the solid variant. The basaloid cells form islands and cords that have a broad, rounded, lobular pattern. These cells are sharply demarcated from the connective tissue stroma by basement membrane. This feature contrasts with the melting type of growth characteristic of pleomorphic adenoma.

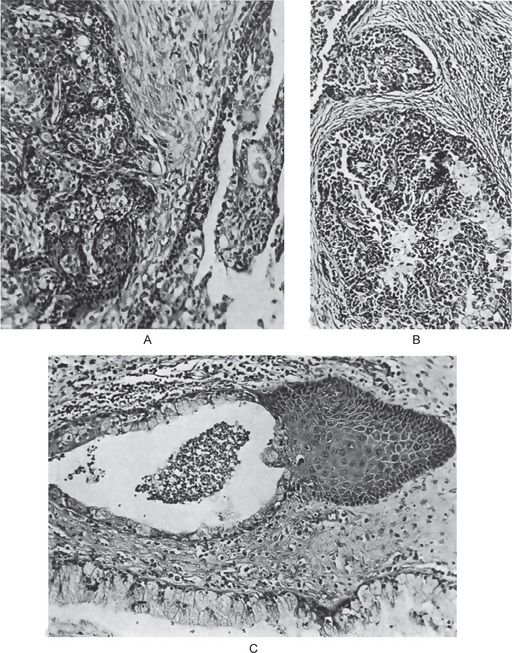

This pattern exhibits multiple small, round duct like structures. These tubules are lined by two distinct layers of cells, with inner cuboidal ductal cells surrounded by an outer layer of basaloid cells. The tubular variant is the least common; however, tubule formation either alone or with basal cell masses, can be found in most basal cell adenomas, at least focally (Fig. 3-9).

This subtype has the same cytologic features as the solid type, but the epithelial islands are narrower and cord like and are interconnected with one another, producing a reticular pattern (Fig. 3-10).

This is a distinct subtype of basal cell adenoma characterized by the presence of abundant, thick, eosinophilic hyaline layer that surrounds and separates the epithelial islands. Electron microscopy has shown that this hyaline material is reduplicated basement membrane. The epithelial islands are arranged in large lobules and appear to mould to the shape of other lobules to resemble a jigsaw puzzle pattern.

Warthin’s Tumor: (Papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum, adenolymphoma)

Warthin’s tumor is the second most common tumor in the salivary glands. This tumor was first recognized by Albrecht in 1910 (quoted by Ellis and Auclair 1991) and later described by Warthin in 1929. This unusual type of salivary gland tumor occurs almost exclusively in the parotid gland, although occasional cases have been reported in the submaxillary gland. The intraoral accessory salivary glands are rarely affected.

Histogenesis

Numerous theories have been advanced to account for the peculiar nature of this tumor. The currently accepted theory is that the tumor arises in salivary gland tissue entrapped within paraparotid or intraparotid lymph nodes during embryogenesis. However, Allegra has suggested that the Warthin’s tumor is most likely a delayed hypersensitivity disease, the lymphocytes being an immune reaction to the salivary ducts which undergo oncocytic change. Hsu and coworkers recently studied the tumor immunohistochemically and have suggested that the lymphoid component of the tumor is an exaggerated secretory immune response.

A strong association between development of this tumor and smoking is documented. The exact mechanism by which smoking may predispose patients to Warthin’s tumor is unclear. However, several studies have shown that a high percentage of Warthin’s tumor patients smoke. Epstein-Barr virus has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of this tumor; however there are many conflicting reports.

Clinical Features

Warthin’s tumor was traditionally considered a disease of men. However, recent reports have identified a substantial percentage of patients who are women. This tumor commonly presents in the sixth and seventh decades and average age of the patients at the time of diagnosis of the lesion was 62 years. The tumor is generally superficial, lying just beneath the parotid capsule or protruding through it. Seldom does the lesion attain a size exceeding 3–4 cm in diameter. It is not painful, is firm to palpation and is clinically indistinguishable from other benign lesions of the parotid gland.

Histologic Features

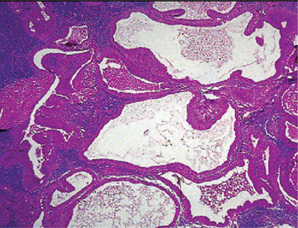

It is a smooth, some what soft parotid mass and is well encapsulated when located in the parotid. The tumor contains variable number of cysts that contains a clear fluid. Areas of focal hemorrhage may also be seen.

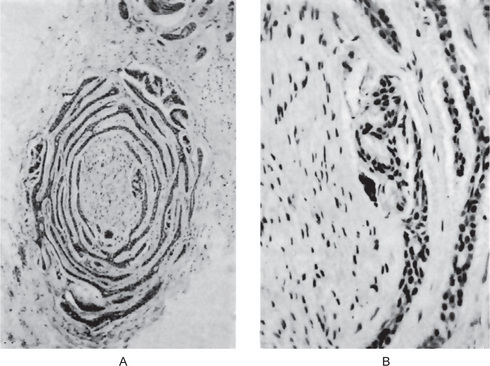

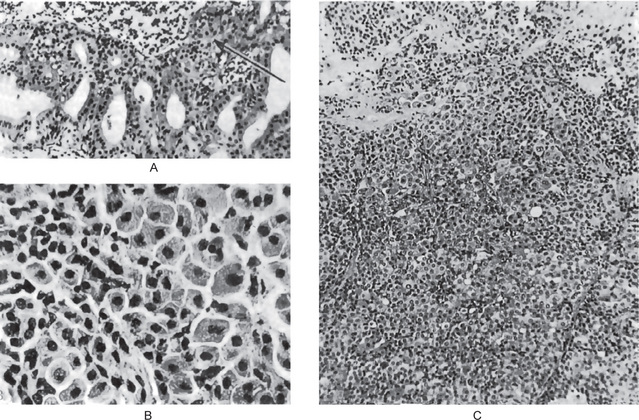

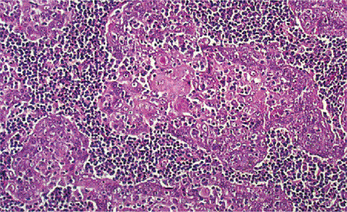

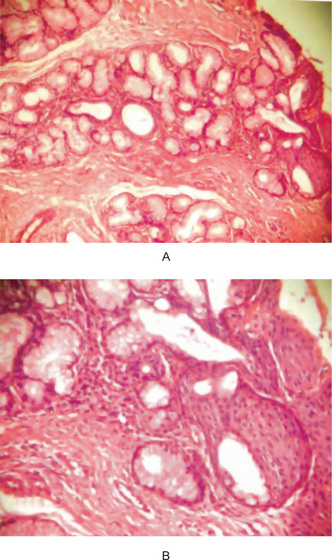

This tumor is made up of two histologic components: epithelial and lymphoid tissue. As the name would indicate, the lesion is essentially an adenoma exhibiting cyst formation, with papillary projections into the cystic spaces and a lymphoid matrix showing germinal centers (Fig. 3-11). The cysts are lined by papillary proliferations of bilayered oncocytic epithelium. The inner layer cells are tall columnar with finely granular and eosinophilic cytoplasm due to presence of mitochondria and slightly hyperchromatic nuclei. The outer layer cells are oncocytic triangular and occasionally fusiform basaloid cells. Focal areas of squamous metaplasia and mucous cell prosoplasia may be seen. There is frequently an eosinophilic coagulum present within the cystic spaces, which appears as a chocolate-colored fluid in the gross specimen. The abundant lymphoid component may represent the normal lymphoid tissue of the lymph node within which the tumor developed or it may actually represent a reactive cellular infiltrate which involves both humoral and cell mediated mechanisms (Fig. 3-12).

Treatment and Prognosis

The accepted treatment of the papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum is surgical excision. This can almost invariably be accomplished without injury to the facial nerve, particularly since the lesion is usually small and superficial. These tumors are well encapsulated and seldom recur after removal.

Malignant transformation is exceedingly rare in either the epithelial or lymphoid component. Cases of mucoepidermoid carcinoma involving Warthin’s tumor of the parotid gland have been reported; however, a direct transition from Warthin’s tumor to mucoepidermoid carcinoma was not identified.

Oncocytoma: (Oncocytic adenoma, oxyphilic adenoma, acidophilic adenoma)

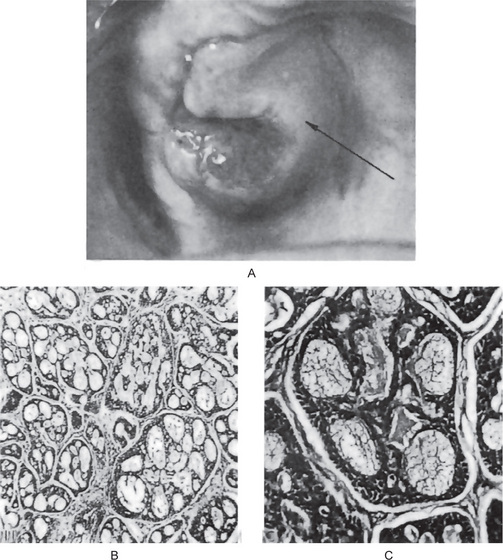

Oncocytoma is a rare benign tumor composed of oncocytes with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and a large number of atypical mitochondria. This rare salivary gland tumor is a small benign lesion, which usually occurs in the parotid gland. Except that it does not generally attain any great size, it does not differ in its clinical characteristics from other benign salivary gland tumors. For this reason, a clinical diagnosis is difficult if not impossible to establish. The name ‘oncocytoma’ is derived from the resemblance of these tumor cells to apparently normal cells which have been termed ‘oncocytes’ and which are found in a great number of locations, including the salivary glands, respiratory tract, breast, thyroid, pancreas, parathyroid, pituitary, testicle, fallopian tube, liver and stomach. These cells are predominantly seen in duct linings of glands in elderly persons, but little is actually known of their mode of development or significance (Fig. 3-13). Electron microscopic studies have shown that the cytoplasm of the oncocyte is choked with mitochondria. Ionizing radiation is the predisposing condition.

Figure 3-13 Oxyphilic adenoma.

(A) Normal oncocytes in accessory salivary gland ducts of elderly patient. (B) High-power photomicrograph. (C) Low-power photomicrograph of oncocytoma.

Clinical Features

The oncocytoma is somewhat more common in women than in men and occurs almost exclusively in elderly persons. Chaudhry and Gorlin, who reviewed the literature, found 29 cases of oncocytoma and added four new cases to those reported. Only occasionally does this tumor arise before the age of 60 years, 80% of cases occurring between the ages of 51 and 80 years. The tumor usually measures 3–5 cm in diameter and appears as a discrete, encapsulated mass which is sometimes nodular. Pain is generally absent.

An interesting condition called diffuse multi nodular oncocytoma or ‘oncocytosis’ of the parotid gland has been described by Schwartz and Feldman. This condition is characterized by nodules of oncocytes which involve the entire gland or large portions of it.

Histologic Features

The oxyphilic adenoma is characterized microscopically by large cells which have an eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell membrane and which tend to be arranged in narrow rows or cords (Fig. 3-13). The oncocytes are arranged in sheets or nests and cords, which form alveolar or organoid pattern. Some degree of cellular atypia, nuclear hyperchromatism and pleomorphism is accepted as compatible with benignancy in oncocytoma. These cells, exhibiting few mitotic figures, are closely packed, and there is little supportive stroma (Fig. 3-14). Lymphoid tissue is frequently present, but does not appear to be an integral part of the lesion. Ultrastructural studies of parotid oncocytomas by Tandler and associates and Kay and Still have shown that the cells are engorged with enlarged and morphologically altered mitochondria.

Figure 3-14 Oncocytoma alveolar pattern.

Illustrated by clusters of oncocytes that are supported by thin, fibrous connective tissue septa and small blood vessels. Note oncocytes have clear cytoplasm that is interspersed with cytoplasmic granularity.

A variant of the oxyphilic adenoma is sometimes seen in intraoral salivary glands, particularly in the buccal mucosa and upper lip. This has been termed, an oncocytic cystadenoma since it is a tumor like nodule composed chiefly of numerous dilated duct like or cyst like structures lined with oncocytes. In recurrent tumors, there may be marked clear cell change and these tumors may be referred to as clear-cell oncocytoma. Treatment and Prognosis. The treatment of choice is surgical excision, and the tumor does not tend to recur. Malignant transformation is uncommon, but malignant oncocytoma is now a well-established entity. Johns and associates reviewed the literature on malignant oncocytomas and reported three additional cases. Other well-documented cases have been those of Lee and Roth, and Gray and his coworkers.

Canalicular Adenoma

Canalicular adenoma is an uncommon neoplasm composed of columnar epithelial cells arranged in a single or double layer forming branching cords in a loose stroma. The bilayer shows an intermittent separation, which forms structures resembling lumen or canaliculi.

Clinical Features

This lesion originates primarily in the intraoral accessory salivary glands, and in the vast majority of cases, it occurs in the upper lip. However, cases are known in which the lesion occurred in the palate, buccal mucosa and lower lip. Only one was noted in the parotid gland in the series reported by Nelson and Jacoway. The tumor occurs in adults far more common in patients of age 34–65 years; this tumor is seen more commonly in females with a ratio of 1.8 : 1. The tumor generally presents as a slowly growing, well-circumscribed, firm nodule which, particularly in the lip, is not fixed and may be moved through the tissue for some distance. Occasionally, two separate and distinct tumors may occur in the upper lip of an individual.

Histologic Features

The canalicular adenoma has a strikingly characteristic picture. It is composed of long columns or cords of cuboidal or columnar cells in a single layer. These single layers of cells are parallel, forming long canals. Some-times rows of cells are closely approximated and appear as a double row of cells showing a ‘party wall’. In some instances, cystic spaces of varying sizes are enclosed by these cords. The cystic spaces are usually filled with an eosinophilic coagulum. The supporting stroma is loose and fibrillar with delicate vascularity (Fig. 3-15). The tumor has, at times, been mistaken for an adenoid cystic carcinoma and care should be taken to prevent this error (Fig. 3-16). As Mader and Nelson have pointed out, the adenoid cystic carcinoma rarely occurs in the upper lip and is seldom freely movable. Occasionally the tumor may be multifocal and foci of tumor cells are found outside the main lesion.

Sebaceous Adenoma

Sebaceous adenoma is a rare benign tumor that accounts for 0.1% of all salivary gland neoplasms and slightly less than 0.5% of all salivary adenomas. The mean age at initial clinical presentation was 58 years (range 22–90 years). This tumor is more common in men. In a series of cases reported by Ellis et al (1991), 12 tumors were located in the parotid gland, 4 in the buccal mucosa, two in the submandibular gland, and three in the area of lower molars or retromolar region. The tumors ranged in size from 0.42–3.0 cm in diameter.

The tumors are commonly encapsulated or sharply circumscribed, and they vary in color from grayish-white to pinkish-white to yellow or yellowish gray. These tumors are composed of sebaceous cell nests with minimal atypia and pleomorphism and no tendency to invade local structures. Many tumors are microcystic or may be composed predominantly of ectatic salivary ducts with focal sebaceous differentiation. The sebaceous glands may vary markedly in size and in tortuosity and are usually embedded in a fibrous stroma. Occasionally tumors demonstrate marked oncocytic metaplasia, and histiocytes and/or foreign body giant cells may be seen focally. Lymphoid follicles, cytologic atypia, cellular necrosis, and mitosis are not observed in sebaceous adenomas.

Conservative excision seems to be the treatment of choice. No recurrences have been reported.

Ductal Papilloma

The term ductal papilloma is used to identify a group of three rare benign papillary salivary gland tumors. They represent adenomas with unique papillary features and arise from the salivary gland duct system. There are three types with unique histopathological features. These are inverted ductal papilloma, intraductal papilloma, and sialadenoma papilliferum.

Inverted Ductal Papilloma

Inverted ductal papilloma was first described by White et al, in 1982. It is a very rare tumor and has been described only in minor salivary glands of adults. The lower lip is the most frequently involved site followed by buccal vestibular mucosa. Inverted ductal papillomas appear to arise from the excretory ducts near the mucosal surface. Clinically, these tumors are seen as submucosal nodules which may have a pit or indentation in the overlying surface mucosa. These tumors do not show any gender predilection.

Histologically, it consists of basaloid and squamous cells arranged in thick, bulbous papillary proliferations that project into the ductal lumen. The lumen of the tumor is often narrow and in some tumors communicates with the exterior of the mucosal surface through a constricted opening.

Intraductal Papilloma

Intraductal papilloma is an ill-defined lesion that often is confused with papillary cystadenoma. It usually occurs in adults, with a mean age of occurrence being 54 years and is common in the minor salivary glands. The lower lip is the most frequently involved site followed by upper lip, palate and buccal mucosa. No gender predilection has been noted. Intraductal papilloma presents clinically as a submucosal swelling. These tumors appear to arise from the excretory ducts at a deeper level than the inverted ductal papilloma.

Microscopically, it exhibits a unicystic dilated structure. The cyst wall is lined by a single or double row of cuboidal and columnar cells, which extend into the cyst lumen as papillary projections having thin fibrovascular cores.

Sialadenoma Papilliferum

Sialadenoma papilliferum most commonly involves the minor salivary gland. This has a more complex histology, with a biphasic growth pattern of exophytic papillary and endophytic components. This tumor usually affects adults, the average age of the patients is 56 years. A male predilection is seen. The clinical presentation is unique as nearly all salivary gland neoplasms manifest as subsurface nodular swellings whereas sialadenoma papilliferum occurs as an exophytic, papillary surface lesion. The clinical impression in most cases is squamous papilloma of the mucosa.

Microscopically, these tumors display both an exophytic and an endophytic proliferation of ductal epithelium. The surface of the lesion is formed of papillary projections of epithelium supported by fibrovascular cores, covered by parakeratotic stratified squamous epithelium. The fibrovascular cores have an inflammatory cell infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils. The ductal epithelium continues downwards into the deeper connective tissues. Multiple ductal lumina are seen, which are lined by a double row of cells consisting of a luminal layer of tall columnar cells resting on a cuboidal basal layer.

Cystadenoma

Cystadenomas of the salivary glands are benign neoplasms in which the epithelium demonstrates adenomatous proliferation that is characterized by formation of multiple cystic structures. Several morphologic variants of cystadenoma have been described of which papillary cystadenoma and mucinous cystadenoma are important. The papillary cystadenoma (PC) is defined as a cystadenoma in which the cystic space is filled with papillary projections. WHO described papillary cystadenoma as “a tumor that closely resembles Warthin’s tumor but without the lymphoid elements, constituting multiple papillary projections and a greater variety of epithelial lining cells.” If mucous cells predominate in the cell population of the lining epithelial cells, the tumor is termed as mucinous cystadenoma.

Clinical Features

Cystadenoma is widely distributed among major and minor salivary glands. Most of the minor salivary gland tumors are seen in lips, buccal mucosa, palate and the tonsillar area. This is more common in females than males (2:1) and occurs in older age, most common in the eighth decade of life. Clinically, it presents as a slow growing painless slightly compressible swelling. Some of the nodules are clinically similar to mucocele.

Histologic Features

Epithelial proliferation (Fig. 3-17) results in various sized cystic structures. The lining of these cystic structures varies from flattened to tall columnar cells, and cuboidal, mucous and oncocytic cells may also be seen. The lining thickness varies from one to three epithelial cells. Limited papillary growth with central connective tissue core is seen. Eosinophilic or slightly hematoxyphilic secretions are seen in the stroma. Dense fibrous connective tissue stroma with scattered inflammatory cells is present.

Malignant Tumors of the Salivary Glands

Acinic Cell Carcinoma: (Acinar cell or serous cell adenoma, adenocarcinoma)

Most salivary gland tumors arise from the epithelium of the duct apparatus, but occasionally lesions seem to show acinar cell differentiation. Acinic cell carcinoma is a malignant epithelial neoplasm in which the neoplastic cells express acinar differentiation. Some authors advocate the existence of both benign and malignant acinic cell neoplasms, whereas others are of the opinion that all acinic cell neoplasms are malignant. Unfortunately, the criteria for distinguishing between benign and malignant acinar cell tumors, if such a distinction exists, have not been clearly established. In an extensive study of acinic cell tumors of the major salivary glands by Abrams and his coworkers, it was concluded that most investigators believe that all tumors of this type have at least a low-grade malignant potential. By conventional use, the term acinic cell carcinoma is defined by cytologic differentiation towards serous acinar cells (as opposed to mucous acinar cells), whose characteristic feature is cytoplasmic PAS-positive zymogen-type secretory granules. In AFIP data of salivary gland neoplasms, acinic cell carcinoma is the third most common malignant salivary gland epithelial neoplasm after mucoepidermoid carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. In this data, acinic cell carcinoma comprised 17% of primary malignant salivary gland tumors or about 6% of all salivary gland neoplasms (cited by Ellis GL, Auclair PL, Gnepp DR, 1991).

Clinical Features

The acinic cell carcinoma closely resembles the pleomorphic adenoma in gross appearance, tending to be encapsulated and lobulated. Although this tumor has been reported occurring chiefly in the parotid, with more than 80% of the cases occurring in the parotid gland, it does occur occasionally in the other major glands and in the accessory intraoral glands (Fig. 3-18). The most common intraoral sites are the lips and buccal mucosa. The acinic cell carcinoma occurs predominantly in persons in middle age or somewhat older, the mean age being 44 years. It has also been encountered in 12% of the patients before the age of 20 years. Women were affected more than men (3 : 2). This tumor presents as a slowly growing, mobile or fixed mass of various durations. Usually asymptomatic but pain or tenderness is seen in over one third of the patients. Facial muscle weakness may be seen. Patients with bilateral synchronous tumors have been reported.

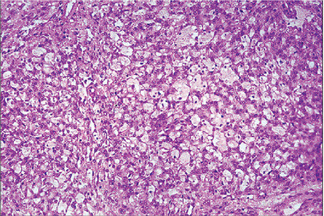

Histologic Features

The acinic cell carcinoma, which is frequently surrounded by a thin capsule, may be composed of cells of varying degrees of differentiation. Well-differentiated cells bear remarkable resemblance to normal acinar cells, whereas less differentiated cells resemble embryonic ducts and immature acinar cells. Abrams and his associates have described four growth patterns: (1) solid, (2) papillary-cystic, (3) follicular, and (4) microcystic. In general, one pattern predominates, although combinations can occur. The most characteristic cell seen has the features of the serous acinar cells, with abundant granular basophilic cytoplasm and a round darkly stained eccentric nucleus. Other cells seen are the intercalated duct like cells, which are smaller and the vacuolated cells which seem to be unique to acinic cell carcinomas among salivary gland neoplasms.

Connective tissue stroma is delicately fibro vascular collagenous tissue. Lymphoid elements are commonly found in parotid acinic cell carcinomas, a feature which is helpful in the diagnosis. Such features are not found in the intraoral tumors. Apparently the acinic cell carcinoma can arise from embryologically entrapped salivary gland tissue in lymph nodes in or near the parotid compartment. Although ‘clear cells,’ have been described in acinic cell carcinomas, they most likely represent cells altered by fixation or they may actually represent the component cells of a clear cell carcinoma (q.v.), a recently recognized entity (Figs. 3-19, 3-20).

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of the acinic cell carcinoma in most cases has been surgical. Perzin and LiVolsi recommend total excision of parotid gland tumors with preservation of the facial nerve unless it is involved. Lymph node dissection is indicated only in the presence of clinical involvement and not as a routine procedure. Radiation therapy has not been shown to be of therapeutic value. Intraoral tumors are treated by surgical excision. Poor prognostic features included pain or fixation; gross invasion; and microscopic features of desmoplasia, atypia, or increased mitotic activity. Neither morphologic pattern nor cell composition was a predictive feature.

Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor, first studied and described as a separate entity by Stewart, Foote and Becker in 1945. As the name implies, the tumor is composed of both mucus-secreting cells and epidermoid-type cells in varying proportions. Columnar and clear cells are also seen, and often demonstrate prominent cystic growth. It is the most common malignant neoplasm observed in the major and minor salivary glands. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma represents 29–34% of malignant tumors originating in both major and minor salivary glands. This carcinoma of the salivary glands accounts for 5% of all salivary gland tumors. The parotid gland is the most common site of occurrence. Intraorally, mucoepidermoid carcinoma shows a strong predilection for the palate.

Clinical Features

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma occurs with a slight female predilection. It occurs primarily in the third or fifth decades of life, with an average age of 47 years, but can occur in virtually all decades. It is the most common malignant salivary gland tumor of children. Prior exposure to ionizing radiation appears to substantially increase the risk of developing mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

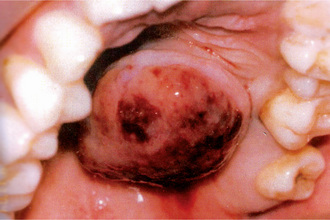

The tumor of low-grade malignancy usually appears as a slowly enlarging, painless mass which simulates the pleomorphic adenoma. Unlike the pleomorphic adenoma; however, the low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma seldom exceeds 5 cm in diameter, is not completely encapsulated and often contains cysts which may be filled with a viscid, mucoid material. In addition to palate intraoral tumors occur on the buccal mucosa, tongue and retromolar areas. Because of their tendency to develop cystic areas, these intraoral lesions may bear close clinical resemblance to the mucous retention phenomenon or mucocele, especially those in the retromolar area (Fig. 3-21).

Figure 3-21 Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of palate. Courtesy of Dr Neelakandan RS, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College, Chennai.

The tumor of high-grade malignancy grows rapidly and does produce pain as an early symptom. Facial nerve paralysis is frequent in parotid tumors. The patient may also complain of trismus, drainage from the ear, dysphagia, numbness of the adjacent areas and ulceration, noted particularly in tumors of the minor salivary glands. The mucoepidermoid carcinoma is not encapsulated, but tends to infiltrate the surrounding tissue, and in a large percentage of cases, it metastasize to regional lymph nodes. Distant metastases to lung, bone, brain and subcutaneous tissues are also common.

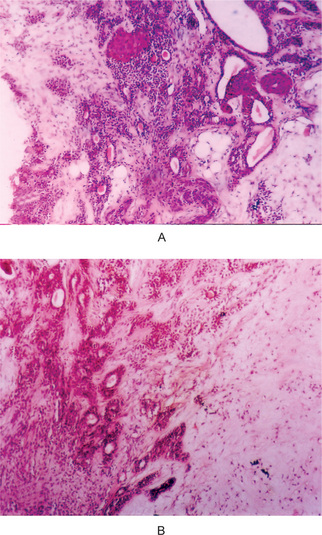

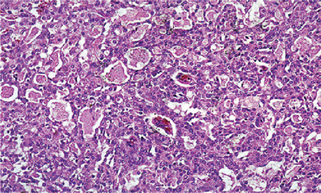

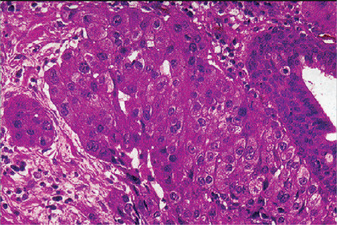

Histologic Features

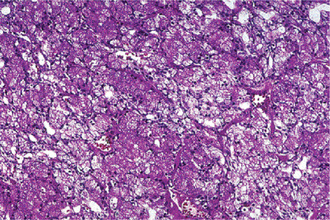

The mucoepidermoid carcinoma is composed of mucous secreting cells, epidermoid type (squamous) cells and intermediate cells. The mucous cells are of various shapes and have abundant, pale, foamy cytoplasm that stains positively for mucin stains. The epidermoid cells have squamoid features, demonstrate a polygonal shape, intercellular bridges and rarely keratinization. A population of cells that is often more important in recognizing mucoepidermoid carcinoma is a group of highly prolific, basaloid cells referred to as the intermediate cells. These cells are larger than basal cells and smaller than the squamous cells and are believed to be the progenitor of epidermoid and mucous cells. Occasionally clusters of clear cells can be present. These clear cells are generally mucin and glycogen free. Epidermoid cells, together with intermediate and mucous cells line cystic spaces or form solid masses or cords. Epidermoid and mucous cells may be arranged in a glandular pattern. The cysts may rupture liberating mucus which may pool in the connective tissue and evoke an inflammatory reaction (Fig. 3-22).

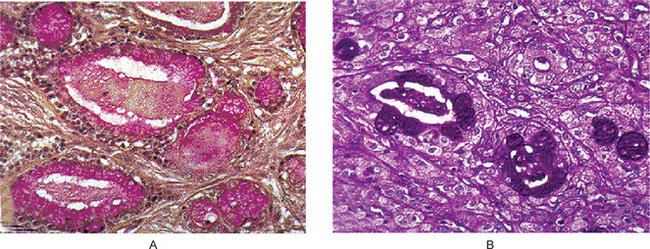

Figure 3-22 Mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

(A, B) Photomicrographs illustrate the association of the pale-staining, mucus-containing cells associated with darker staining epidermoid cells in a moderately high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma. (C) In one duct like structure the lining consists partially of squamous epithelium and partially of mucous cells From F Vellios: Am J Clin Pathol, 25: 147, 1955.

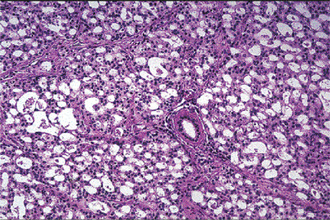

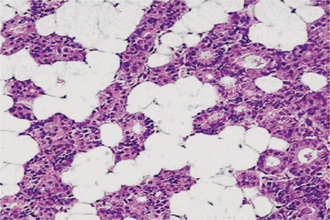

Mucoepidermoid carcinomas are graded as low-grade, intermediate-grade, and high-grade.

Low-grade tumors show well formed glandular structures and prominent mucin filled cystic spaces, minimal cellular atypia and a high proportion of mucous cells (Fig. 3-23).

Figure 3-23 Mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

(A) Mucicarmine stain. (B) PAS stain. The two components of the tumor are large, pale, mucous secreting cells, which typically surround large or small cystic spaces and sheets of epidermoid cells.

Intermediate-grade tumors have solid areas of epidermoid cells or squamous cells with intermediate basaloid cells. Cyst formation is seen but is less prominent than that observed in low-grade tumors. All cell types are present, but intermediate cells predominate.

High-grade tumors consist of cells present as solid nests and cords of intermediate basaloid cells and epidermoid cells. Prominent nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity is noted. Cystic component is usually very less (<20%). Glandular component is rare although occasionally it may predominate. Necrosis and perineural invasion may be present.

Variants of Tumor

Sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Although mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common primary malignancy of the salivary glands, the sclerosing morphologic variant of this tumor is extremely rare, with only six reported cases. As its name suggests, sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma is characterized by an intense central sclerosis that occupies the entirety of an otherwise typical tumor, frequently with an inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, eosinophils, and/ or lymphocytes at its peripheral regions.

The sclerosis associated with these tumors may obscure their typical morphologic features and result in diagnostic difficulties. Tumor infarction and extravasation of mucin resulting in reactive fibrosis are two mechanisms that have been suggested as the cause of this morphologic variant.

Intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma may originate within the jaws. This tumor type is known as central mucoepidermoid carcinoma. It is thought to form by the malignant transformation of the epithelial lining of odontogenic cysts. The tumor presents as an asymptomatic radiolucent lesion and is histologically of low-grade malignancy. The mandible is three times more commonly affected than the maxilla.

Treatment and Prognosis

Conservative excision with preservation of the facial nerve, if possible, is recommended for low- and intermediate-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas of the parotid gland. The affected submandibular gland should be removed entirely. Radical neck dissection is performed in patients with clinical evidence of cervical node metastasis and is considered in any patient with a T3 lesion. Treatment for the minor glands is also primarily surgical. Some investigators have recommended postoperative irradiation only for high-grade malignancies, including high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas of the parotid glands. Few studies have assessed the role of chemotherapy and showed that high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma may show sensitivity similar to that of squamous cell carcinoma. Low-grade lesions had a five-year cure rate of 92%, whereas the intermediate-grade and high-grade lesions had a 49% 5-year cure rate.

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma: (Cylindroma, adenocystic carcinoma, adenocystic basal cell carcinoma, pseudoadenomatous basal cell carcinoma, basaloid mixed tumor)

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (formerly known as ‘cylindroma’) is a slow-growing but aggressive neoplasm with a remarkable capacity for recurrence. It is characterized by proliferation of ductal (luminal) and myoepithelial cells in cribriform, tubular, solid and cystic patterns. In a review of its case files, the AFIP found adenoid cystic carcinoma to be the fifth most common malignant epithelial tumor of the salivary glands after mucoepidermoid carcinoma; adenocarcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma; and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA). However, other series report adenoid cystic carcinoma to be the second most common malignant tumor.

Clinical Features

The salivary glands most commonly involved by this tumor are the parotid, the submaxillary and the accessory glands in the palate and tongue (Fig. 3-24). The adenoid cystic carcinoma occurs most commonly during the fifth and sixth decades of life, but it is by no means rare even in the third decade. It is seen more commonly in females. Many of the patients exhibit clinical manifestations of a typical malignant salivary gland tumor: early local pain, facial nerve paralysis in the case of parotid tumors, fixation to deeper structures and local invasion. Some of the lesions, particularly the intraoral ones, exhibit surface ulceration. There may be clinical resemblance in some cases to the pleomorphic adenoma. Adenoid cystic carcinoma has a marked tendency to spread through perineural spaces and usually invades well beyond the clinically apparent borders.

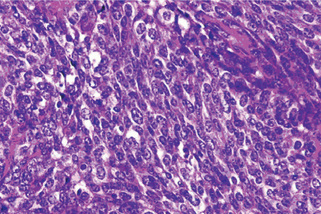

Histologic Features

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is composed of myoepithelial cells and ductal cells which have a varied arrangement. Morphologi cally, three growth patterns have been described: cribriform (classic), tubular, and solid (basaloid). The tumors are categorized according to the predominant pattern. The cribriform pattern shows basaloid epithelial cell nests that form multiple cylindrical cyst like patterns resembling a Swiss cheese or honey comb pattern, which is the most classic and best recognized pattern. The lumina of these spaces contain periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive mucopoly-saccharide secretion. The tubular pattern reveals tubular structures that are lined by stratified cuboidal epithelium. The solid pattern shows solid groups of cuboidal cells with little tendency towards duct or cyst formation. The cribriform pattern is the most common, whereas the solid pattern is the least common. Solid adenoid cystic carcinoma is a high-grade lesion with reported recurrence rates of up to 100% compared with 50–80% for the tubular and cribriform variants.

Variants

Dedifferentiation of adenoid cystic carci noma

Dedifferentiated adenoid cystic carcinomas are a recently defined, rare variant of adenoid cystic carcinoma characterized histologically by two components: conventional low-grade adenoid cystic carcinoma and high-grade ‘dedifferentiated’ carcinoma. Because of frequent recurrence and metastasis, the clinical course is short, similar to that of adenoid cystic carcinomas with a predominant solid growth pattern. Histologically, the low-grade adenoid cystic carcinoma merges gradually into an extensive dedifferentiated component that is composed of solid sheets and cords of anaplastic tumor cells with focal gland formation. Immuno histochemically, the dedifferentiated component (but not the adenoid cystic carcinoma component) shows strong overexpression of p53 protein and cyclin D1, as well as a higher Ki67 index. Molecular studies confirmed the presence of p53 gene mutation selectively in the dedifferentiated component, suggesting a pivotal role of p53 gene alteration in the dedifferentiation process of adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of the adenoid cystic carcinoma is chiefly surgical, although in some cases surgery has been successfully coupled with X-ray radiation. Radiation alone is not recommended. In general, this tumor is a slowly growing lesion which tends to metastasize only late in its course. The cure rate for patients with this disease, though varying somewhat from series to series, is discouragingly low. Factors influencing prognosis are the site of occurrence and the histologic pattern of the tumor (Fig. 3-25). Conley and Dingman (1974) found that there is a marked difference in the clinical behavior of major and minor gland adenoid cystic carcinomas. Only 28% of 78 patients with minor gland tumors were alive with no evidence of disease in a 4–14-year follow-up study. Sixty-four percent of 54 patients with major gland tumors studied over a comparable period were alive and free of disease.

Polymorphous Low-Grade Adenocarcinoma

Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) is a malignant epithelial tumor that is essentially limited in occurrence to minor salivary gland sites and is characterized by bland, uniform nuclear features; diverse but characteristic architecture; infiltrative growth; and perineural infiltration. This is a recently recognized type of salivary gland tumor first described in 1983. Evans and Batsakis first used the term polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma in 1984 to describe this tumor. This tumor includes those entities, which were previously termed as terminal duct carcinoma, lobular carcinoma, papillary carcinoma and trabecular carcinoma.

Clinical Features

In minor gland sites polymorphous lowgrade adenocarcinoma is twice as frequent as adenoid cystic carcinoma, and, among all benign and malignant salivary gland neoplasms, only pleomorphic adenoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma are more common. The average age of patients is reported to be 59 years, with 70% of patients between the ages of 50 and 79 years. The female to male ratio is about 2 : 1. In the AFIP case files, over 60% of tumors occurred in the mucosa of either the soft or hard palates, approximately 16% occurred in the buccal mucosa, and 12% in the upper lip. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma typically presents as a firm, nontender swelling involving the mucosa of the hard and soft palates (often at their junction), the cheek, or the upper lip. Discomfort, bleeding, telangiectasia, or ulceration of the overlying mucosa may occasionally occur.

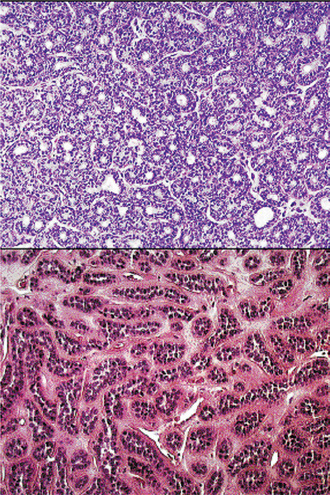

Histologic Features

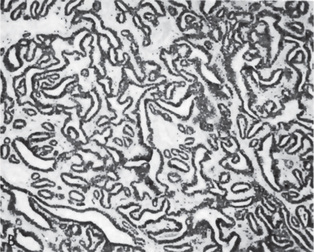

Microscopically polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma is characterized by infiltrative growth with diverse morphology and uniform cytologic features. The tumors are well circumscribed but unencapsulated and infiltrate into adjacent structures. The polymorphic nature of the lesion refers to the variety of growth patterns it assumed which includes solid, ductal, cystic and tubular. In some tumors, a cribriform pattern can be produced, which resembles adenoid cystic carcinoma. The tumor is composed of cuboidal to columnar isomorphic cells that have uniform ovoid to spindle- shaped nuclei. Scant to moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm can be seen. The tumor stroma varies from mucoid to hyaline and in some cases, tumor nests are separated by fibrovascular stroma. Perineural invasion is common that makes this tumor mistaken as adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Treatment

Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma is best treated by conservative wide surgical excision. This neoplasm typically runs a moderately indolent course. Although the tumor can recur, sometimes multiple times over many years, distant metastases have not been reported. The overall prognosis is good. Perineural invasion does not appear to affect the prognosis.

Epithelial-Myoepithelial Carcinoma: (Adenomyoepithelioma, clear cell adenoma, tubular solid adenoma, monomorphic clear cell tumor, glycogen-rich adenoma, glycogen-rich adenocarcinoma)

Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma is an uncommon, biphasic low-grade epithelial neoplasm composed of variable proportions of ductal and large, clear-staining, differentiated myoepithelial cells. It comprises approximately 1% of all epithelial salivary gland neoplasms.

Clinical Features

This is predominantly a tumor of the parotid gland. In the AFIP case files, the mean age of patients is about 60 years and women are more often affected than men. Localized swelling with a history of steady increase in size over a period of time is the common symptom, but occasionally patients experience facial weakness or pain. Nasal obstruction and facial deformity may represent major complaints of patients with maxillary involvement. Some studies have suggested that patients with these tumors are at increased risk for a second primary malignancy—either in the salivary glands or in a separate site (breast and thyroid have been reported).

Histologic Features

The histologic features of this tumor may vary greatly from solid lobules that are separated by bands of hyalinized fibrous tissue to irregular, papillary cystic arrangements with tumor cells which partially or completely fill cystic spaces but most tumors show a multinodular growth pattern with islands of tumor cells separated by dense bands of fibrous connective tissue. The islands of tumor cells are composed of small ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium that is surrounded by clear cells which interface with a thickened, hyaline-like basement membrane. The inner luminal cuboidal cells have finely granular, dense eosinophilic cytoplasm and central or basally located nucleus. The outer, clear myoepithelial cells vary in shape from columnar to ovoid and have a vesicular nucleus located towards the basement membrane.

Basal Cell Adenocarcinoma: (Basaloid salivary carcinoma, carcinoma ex monomorphic adenoma, malignant basal cell adenoma, malignant basal cell tumor, basal cell carcinoma)

Basal cell adenocarcinoma of salivary glands is an uncommon and recently described entity occurring almost exclusively at the major salivary glands. It is a low-grade malignant neoplasm that is cytologically similar to basal cell adenoma, but is infiltrative and has a small potential for metastasis.

Clinical Features

In AFIP case files spanning almost 11 years, basal cell carcinoma comprised 1.6% of all salivary gland neoplasms and 2.9% of salivary gland malignancies. Nearly 90% of tumors occurred in the parotid gland. The average age of patients is reported to be 60 years. Basal cell adenocarcinoma predominantly occurs at the seventh decade without gender preference. The tumors affecting the minor salivary glands occur most frequently at the oral cavity (buccal mucosa, palate) and the upper respiratory tract. Similar to most salivary gland neoplasms, swelling is typically the only sign or symptom experienced. A sudden increase in size may occur in a few patients.

Histologic Features

As seen with basal cell adenoma, basal cell adenocarcinoma can also be histologically divided into four subtypes: (1) solid, (2) ductal, (3) trabecular, and (4) membranous.

The prevalent histologic tumor pattern is represented by solid neoplastic aggregates with a peripheral cell palisading arrangement frequently delineated by basement membrane like material. Few areas with trabecular or membranous arrangement may be seen. The neoplastic clusters are formed by two cell populations: the small dark cell type, which is predominant and a large pale cell type. Generally, the small dark cells are present peripherally to the larger paler cells. The tumor extends into the surrounding tissues by local infiltration as nodules, nests and cords. Perineural and vascular invasion is noticed in a few cases.

Treatment and Prognosis

Basal cell carcinomas are low-grade carcinomas that are infiltrative, locally destructive, and tend to recur. They only occasionally metastasize. Surgical excision with a wide enough margin to ensure complete removal of the tumor is the primary treatment. Regional lymph node dissection is recommended only if there is evidence of metastatic disease. The overall prognosis for patients with this tumor is good.

Sebaceous Carcinoma

Sebaceous carcinoma is a malignant neoplasm consisting chiefly of sebaceous cells, which are arranged in sheets and/or nests with different degrees of pleomorphism, nuclear atypia and invasiveness.

Clinical Features

This tumor shows bimodal age distribution, peak incidence of tumor occurrence is found in the third decade and seventh and eighth decades of life (range 17–93 years). The male and female incidence of occurrence is almost equal. Most of the reported cases have arisen in the parotid gland. The chief complaint is that of painful masses, with varying degrees of facial nerve paralysis, and occasionally, fixation of the skin is present. Tumors range in size from 0.6–8.5 cm in greatest dimension.

Histologic Features

Tumors are well circumscribed or partially encapsulated, with pushing or locally infiltratingmargins. Cellular pleomorphism and cellular atypia are uniformly present and are more prevalent than in sebaceous adenomas. Tumor cells may be arranged in multiple lare focior in sheets and have hyperchromatic nuclei surrounded by abundant clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3-26 A). Areas of cellular necrosis and fibrosis are commonly found. Perineural invasion has been observed in more than 20% of tumors. Vascular invasion is extremely unusual. Rare oncocytes and foreign body giant cells with histiocytes may be observed.

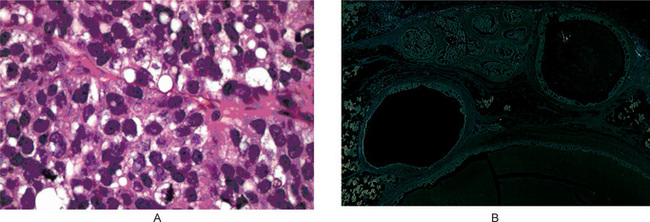

Figure 3-26 Sebaceous cell adenocarcinoma and cystadenocarcinoma.

(A) Sebaceous cell adenocarcinoma. Well differentiated sebaceous carcinoma composed of an area resembling sebaceous adenoma admixed with sheets of carcinoma cells. (B) Cystadenocarcinoma. Cystic neoplasm showing irregular cysts with great variation in size and frequent intraluminal papillary process. Invasion into the parotid parenchyma is noticed (upper field) Courtesy of Christopher DM Fletcher.

Papillary Cystadenocarcinoma: (Cystadenocarcinoma, malignant papillary cystadenoma, mucus-producing adenopapillary [nonepidermoid] carcinoma, low-grade papillary adenocarcinoma of palate, papillary adenocarcinoma)

Cystadenocarcinoma is the malignant counterpart of cystadenoma. It is a rare malignant epithelial tumor characterized histologically by prominent cystic and, frequently, papillary growth but lacking features that characterize cystic variants of several more common salivary gland neoplasms.

Clinical Features

Cystadenocarcinoma is considered to be a low-grade neoplasm. Most of the cases, about 65%, occurred in the major salivary glands (primarily in the parotid). Among the reported cases men and women are found to be affected equally and the average age at presentation is about 59 years. Patients present with a slowly growing asymptomatic mass. Clinically, this neoplasm is rarely associated with pain or facial paralysis.

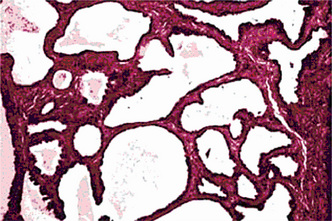

Histologic Features

A cystic growth pattern must dominate the histologic appearance for the diagnosis to be considered (Fig. 3-26 B). These cystic spaces vary in size between tumors as well as within the same tumor. These neoplasms may appear circumscribed or reveal haphazard growth throughout the gland. The lumina often are filled with mucus and hemorrhage and dystrophic calcifications are sometimes evident focally. The lining cells vary from cuboidal to tall columnar, and often a single tumor contains basaloid, oncocytic, clear, and occasionally, mucus cells that form adenomatous or nodular, solid epithelial areas. These solid areas usually occupy the space between the cystic structures. Nuclear hyperchromatism and nuclear variability are subtle, and only rare mitotic figures are present. Nucleoli may be obvious. Encapsulation is incomplete, and infiltration into either salivary gland parenchyma or fibrous or adipose tissue is seen. The tumor may infiltrate either as cyst like structures or as solid islands. Although the vast majority of cystadenocarcinomas are low-grade lesions, moderate/intermediate-grade tumors do exist.

Treatment and Prognosis

No information is currently available that pertains specifically to the prognosis of the salivary gland cystadenocarcinomas. Currently the treatment principles for low-grade cystadenocarcinomas are similar to the principles applied for other low-grade salivary gland adenocarcinomas. These include consideration of the site, the clinical extent of the disease and the histologic grade prior to institution of therapy. Radical neck dissection should be preserved only to deal with obvious metastases.

Mucinous Adenocarcinoma

Mucinous adenocarcinoma is a rare malignant neoplasm characterized by large amount of extracellular epithelial mucin that contains cords, nests, and solitary epithelial cells. The incidence is unknown. Limited data indicate that most, if not all, occur in the major salivary glands with the submandibular gland as the predominant site. These tumors may be associated with dull pain and tenderness. This neoplasm may be considered to be low-grade.

Clinical Features

Clinically, these lesions are soft, spongy masses that may be thought to be cysts.

Histologic Features

The gross specimens are very mucoid, with a slimy texture and they may actually ooze mucoid material. These tumors are circumscribed but not encapsulated. Low magnification reveals islands and cords of tumor cells that appear to be floating within pools of pale staining mucin. The pools of mucin may be divided into irregular lobules by fibrous connective tissue septa that course through the tumor, which is unencapsulated. The tumor cells are moderately large, cuboidal, and polygonal cells with eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm. The nuclei are vesicular, and scattered mitotic figures may be found. The tumor islands are surrounded by pale-staining mucoid substance. The mucoid substance stains with mucicarmine, periodic acid-Schiff, and alcian blue at pH 2.0. Mucicarmine stain also reveals that many tumor cells contain intracytoplasmic mucin.

Oncocytic Carcinoma: (Oncocytic adenocarcinoma)

Oncocytic carcinoma is a rare, predominantly oncocytic neoplasm whose malignant nature is reflected both by its abnormal morphologic features and infiltrative growth. Bauer and Bauer reported the first case in 1953. Although focal oncocytic features are seen in a wide variety of salivary neoplasms, both benign and malignant oncocytic neoplasms are extremely rare.

Clinical Features

Oncocytic carcinoma may be considered to be a high-grade carcinoma. Most cases occur in the parotid gland but recent reports have described tumors that involved the submandibular gland and minor glands of the palate, nasal cavity, and ethmoid and maxillary sinuses. The average age of patients in one series was 63 years. Patients usually develop parotid masses that cause pain or paralysis. The skin overlying the gland is occasionally discolored or wrinkled.

Histologic Features

All types of benign or malignant salivary gland tumors may have foci of oncocytic cells, but the oncocytic component usually contains such a small portion that it is unlikely to be confused with oncocytic carcinoma. Tumors with a significant oncocytic component include Warthin’s tumor, oncocytoma, and oncocytic carcinoma. They are characterized by oncocytes with marked cellular atypia, frequent mitosis, destruction of adjacent structures, perineural or vascular invasion, and distant or regional lymph node metastasis. Histochemical or electron microscopic confirmation of the oncocytic (mitochondrial) nature of the cytoplasm is necessary because cytoplasmic accumulation of smooth endoplasmic reticulum, lysosomes, or secretory granules may have a similar appearance.

Treatment and Prognosis

Oncocytic carcinoma is considered to be a high-grade neoplasm and aggressive initial surgery seems to have a significantly better overall prognosis. Radiation does not appear to favorably alter the biologic behavior of this tumor. Prophylactic neck dissection may be indicated for tumors that are larger than 2 cm in diameter.

Salivary Duct Carcinoma: (Salivary duct adenocarcinoma)

Salivary duct carcinoma is a rare, typically high-grade malignant epithelial neoplasm composed of structures that resemble expanded salivary gland ducts. A low-grade variant exists. Incidence rates vary depending upon the study cited. In the AFIP files, salivary duct carcinomas represent only 0.2% of all epithelial salivary gland neoplasms. More than 85% of cases involve the parotid gland and approximately 75% of patients are men. The peak incidence is reported to be in the seventh and eighth decades of life.

Clinical Features

Parotid swelling is the most common sign. Facial nerve dysfunction or paralysis occurs in over one-fourth of patients and may be the initial manifestation. The high-grade variant of this neoplasm is one of the most aggressive types of salivary gland carcinomas and is typified by local invasion, lymphatic and hematogenous spread with poor prognosis.

Histologic Features

The infiltrative tumor elements are typically composed of clusters of tumor cells that may have small lumina or cribriform arrangements, but solid, irregularly shaped tumor cell aggregates are frequently present. The neoplastic epithelial cells are cuboidal and polygonal with a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm and are accompanied by a dense fibrous connective tissue stroma that may be hyalinized in some areas. Invasion of the nerves and blood vessels is frequent in addition to infiltration of salivary gland lobules and extra-salivary gland tissues, such as fat, muscle, and bone. Mucicarmine and Alcian blue stains are generally negative, except, perhaps, for a small amount of luminal staining. Immuno histochemical and ultrastructural studies have identified ductal cells but no myoepithelial cells.

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinomas of the salivary glands are rare but aggressive tumors.

Clinical Features

They tend to be present in patients over 40 years of age and occur with nearly equal frequency in men and women. About half of these tumors present in the parotid glands, the minor salivary glands, particularly the palate, lip and tongue are the next most commonly affected sites. Clinical presentation again most often involves an enlarging mass. Adenocarcinoma is different from other salivary gland neoplasms in that as many as 25% of patients will complain of pain or facial weakness at presentation.

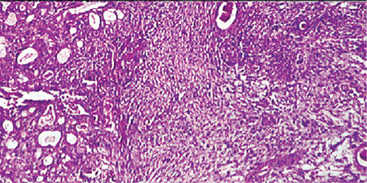

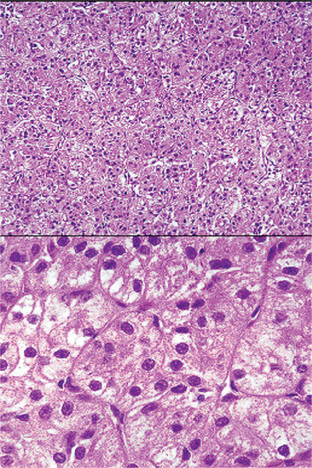

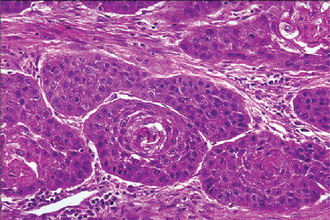

Histologic Features

Gross pathology reveals a firm mass with irregular borders and infiltration into surrounding tissue. It is generally a solid tumor without any cystic spaces. These malignancies can demonstrate a wide range of growth patterns, and for this reason, can be somewhat difficult to classify. However, all adenocarcinomas have in common the formation of glandular structures and they are described as grades I, II or III based upon the degree of cellular differentiation. Grade I lesions have well formed ductal structures while grade III lesions have a more solid growth pattern with few glandular characteristics (Figs. 3-27, 3-28).

Treatment and Prognosis

Because these are more aggressive tumors, treatment for adenocarcinoma is aggressive. Complete local excision is the mainstay of therapy. In the parotid this may include facial nerve sacrifice. In the minor salivary glands, a portion of the maxilla or mandible may have to be resected with the tumor. Postoperative radiation therapy does seem to be of some benefit. Lymph node metastasis is not uncommon and in patients with palpable neck disease neck dissection is warranted. Local recurrence rates vary in the literature but have been cited as high as 51%.

Malignant Myoepithelioma: (Myoepithelial carcinoma)

Ellis GL (1991) defined myoepithelial carcinoma as a malignant epithelial neoplasm whose tumor cells demonstrate cytologic differentiation towards myoepithelial cells and lack ductal or acinar differentiation. Myoepithelial carcinoma is a rare, malignant salivary gland neoplasm in which the tumor cells almost exclusively manifest myoepithelial differentiation. This neoplasm represents the malignant counterpart of benign myoepithelioma. A majority of the tumors occur in the parotid gland. The mean age of patients is reported to be 55 years.

Clinical Features

The majority of patients present with the primary complaint of a painless mass. This is an intermediateto high-grade carcinoma. Histologic grade does not appear to correlate well with clinical behavior; tumors with a low-grade histologic appearance may behave aggressively.

Histologic Features

The cytologic features of individual cells and the general morphologic features resemble tumor cells in benign myoepithelioma and the myoepithelial cells of mixed tumor. The tumor cells may be spindle shaped or plasmacytoid cells (Fig. 3-29). The cell types are often intermixed but usually one or the other cell type predominates. The tumors may be quite cellular and more suggestive of sarcoma than carcinoma. The stroma in other areas of the tumors may be more conspicuous and myxoid. These tumors are distinguished from benign myoepithelial neoplasms by their infiltrative, destructive growth. They usually demonstrate increased mitotic activity and cellular pleomorphism. Some tumor cell should be immunoreactive for cytokeratin, S100 protein, smooth muscle actin, and occasionally, glial fibrillary acidic protein.

Carcinoma in Pleomorphic Adenoma: (Malignant mixed tumor)

Malignant mixed tumors include three distinct clinicopathologic entities: carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, carcinosarcoma, and metastasizing mixed tumor. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma constitutes the vast majority of cases, whereas carcinosarcoma (true malignant mixed tumor) and metastasizing mixed tumor are extremely rare.

Carcinoma ex Pleomorphic Adenoma (Carcinoma exmixed tumor)

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma is the most common of the three salivary neoplasms that are broadly referred to as malignant mixed tumors. It occurs when a carcinoma develops from the epithelial component of a preexisting pleomorphic adenoma. Diagnosis requires the identification of benign tumor in the tissue sample. The incidence or relative frequency of this tumor may vary considerably depending on the study cited. A review of material at the AFIP showed carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma to comprise 8.8% of all mixed tumors and 4.6% of all malignant salivary gland tumors, ranking it as the sixth most common malignant salivary gland tumor after mucoepidermoid carcinoma; adenocarcinoma; acinic cell carcinoma; polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma; and adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Clinical Features

The neoplasm occurs primarily in the major salivary glands. It occurs most often in the parotid, followed by the submandibular gland and palate. It presents in the sixth to eighth decade of life with patients averaging 10 years older than those with pleomorphic adenomas. Presentation is usually a painless mass but some patients will report recent rapid enlargement of a long-standing nodule. Approximately one-third of patients may experience facial paralysis.

Histologic Features

Gross pathology of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma often shows a poorly circumscribed, infiltrative, hard mass. Micro scopically malignant appearing cells are present adjacent to a typical appearing pleomorphic adenoma. The malignant portion of the tumor can take the form of any epithelial malignancy except acinic cell (Fig. 3-30). Most commonly this will be in the form of an undifferentiated carcinoma (30%) or adenocarcinoma (25%). This tumor tends to be more aggressive than other salivary malignancies and about 25% of patients will have lymph node metastasis on presentation.

Treatment and Prognosis