Developmental Disturbances of Oral and Paraoral Structures

. Developmental Disturbances of Jaws

. Developmental Disturbances of Jaws

. Abnormalities of Dental Arch Relations

. Abnormalities of Dental Arch Relations

. Developmental Disturbances of Lips and Palate

. Developmental Disturbances of Lips and Palate

. Hereditary Intestinal Polyposis Syndrome

. Hereditary Intestinal Polyposis Syndrome

. Developmental Disturbances of Oral Mucosa

. Developmental Disturbances of Oral Mucosa

. Developmental Disturbances of Gingiva

. Developmental Disturbances of Gingiva

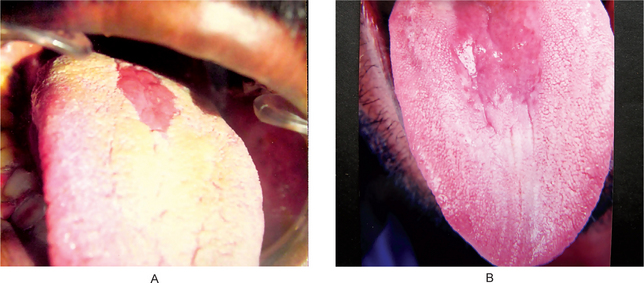

. Developmental Disturbances of Tongue

. Developmental Disturbances of Tongue

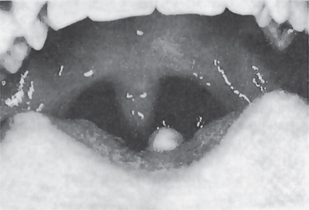

. Developmental Disturbances of Oral Lymphoid Tissue

. Developmental Disturbances of Oral Lymphoid Tissue

. Developmental Disturbances of Salivary Glands

. Developmental Disturbances of Salivary Glands

. Developmental Disturbances in Size of Teeth

. Developmental Disturbances in Size of Teeth

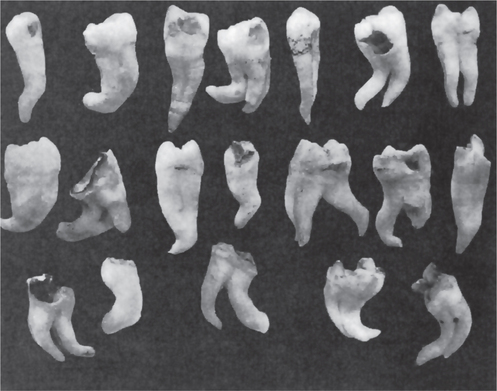

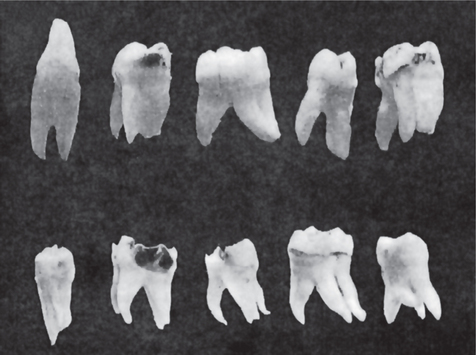

. Developmental Disturbances in Shape of Teeth

. Developmental Disturbances in Shape of Teeth

. Developmental Disturbances in Number of Teeth

. Developmental Disturbances in Number of Teeth

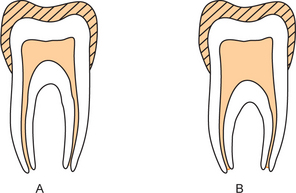

. Developmental Disturbances in Structure of Teeth

. Developmental Disturbances in Structure of Teeth

Craniofacial Anomalies

Craniofacial anomalies (CFA) are a diverse group of deformities in the growth of the head and facial bones. Anomaly is a medical term meaning ‘irregularity’ or ‘different from normal’. These abnormalities are congenital (present at birth) and have numerous variations: some are mild, others are severe and require surgery.

There is no single factor that causes these abnormalities. Instead, there are many factors that may contribute to their development, including the following:

• Combination of genes. A child may receive a particular combination of gene(s) from one or both parents, or there may be a change in the genes at the time of conception, which results in a craniofacial anomaly.

• Environmental. There is no data that shows a direct correlation between any specific drug or chemical exposure causing a craniofacial anomaly. However, any prenatal exposure should be evaluated.

• Folic acid deficiency. Folic acid is a B vitamin found in orange juice, fortified breakfast cereals, enriched grain products, and green, leafy vegetables. Studies have shown that women who do not take sufficient folic acid during pregnancy, or have a diet lacking in folic acid, may have a higher risk of having a baby with certain congenital anomalies, including cleft lip and/or cleft palate.

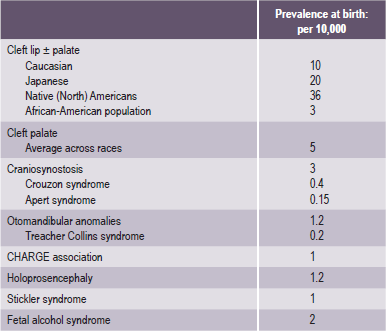

Some of the most common types of craniofacial anomalies (Table 1-1) include:

Table 1-1

Examples of most common craniofacial anomalies

Source: Rovin et al, 1964; Temple, 1989; Cohen et al, 1992; Lewanda et al, 1992; Croen et al, 1996; Derijcle et al, 1996; Sampson et al, 1997; Blate et al, 1998.

• Cleft lip and/or cleft palate. A separation that occurs in the lip or the palate or both. Cleft lip and cleft palate are the most common congenital craniofacial anomalies seen at birth.

Cleft lip. An abnormality in which the lip does not completely form. The degree of the cleft lip can vary greatly, from mild (notching of the lip) to severe (large opening from the lip up through the nose).

Cleft palate. Occurs when the roof of the mouth does not completely close, leaving an opening that can extend into the nasal cavity. The cleft may involve either side of the palate. It can extend from the front of the mouth (hard palate) to the throat (soft palate). The cleft may also include the lip.

• Craniosynostosis. A condition in which the sutures in the skull of an infant close too early, causing problems with normal brain and skull growth. Premature closure of the sutures may also cause the pressure inside the head to increase and the skull or facial bones to change from a normal, symmetrical appearance.

• Hemifacial microsomia. A condition in which the tissues on one side of the face are underdeveloped, affecting primarily the ear (aural), mouth (oral), and jaw (mandibular) areas. Sometimes, both sides of the face can be affected and may involve the skull as well as the face. Hemifacial microsomia is also known as Goldenhar syndrome, brachial arch syndrome, facio-auriculovertebral syndrome (FAV), oculo-auriculovertebral spectrum (OAV), or lateral facial dysplasia.

• Vascular malformation. A birthmark or a growth, present at birth, which is composed of blood vessels that can cause functional or esthetic problems. Vascular malformations may involve multiple body systems. There are several different types of malformations, named after the type of blood vessel that is predominantly affected. Vascular malformations are also known as lymphangiomas, arteriovenous malformations, and vascular gigantism.

• Hemangioma. A type of birthmark; the most common benign (noncancerous) tumor of the skin. Hemangiomas may be present at birth (faint red mark) or appear in the first month after birth. A hemangioma is also known as a port wine stain, strawberry hemangioma, and salmon patch.

• Deformational (or positional) plagiocephaly. A misshapen (asymmetrical) shape of the head (cranium) from repeated pressure to the same area of the head. Plagiocephaly literally means ‘oblique head’ (from the Greek ‘plagio’ for oblique and ‘cephale’ for head).

Collectively they affect a significant proportion of the global society (Table 1-1).

Global Epidemiology

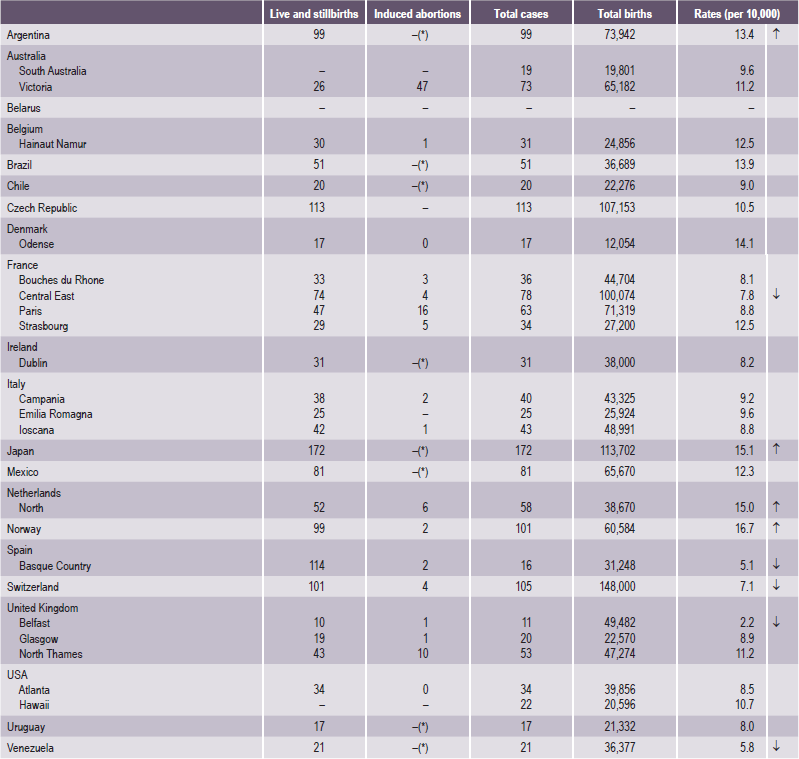

The frequency of occurrence of cleft lip, with or without cleft palate, has been computed on a global scale and is estimated to be 1 in every 800 newborn babies (Tables 1-2 and 1-3). A child is therefore born with a cleft somewhere in the world approximately every two-and-half minutes. Accurate data on the frequency of occurrence of these disorders is relevant for implementing strategies aimed at primary prevention and effective management of these disabled children (Table 1-2). Like anywhere else, the epidemiological data in this situation is also inherently handicapped by:

Table 1-2

Cleft lip with or without cleft palate

Source: WHO (1998), World Atlas of Birth Defects (1st Edition).

*Abortion for birth defect not permitted.

↑= 99% significantly higher than the mean.

↓= 99% significantly lower than the mean.

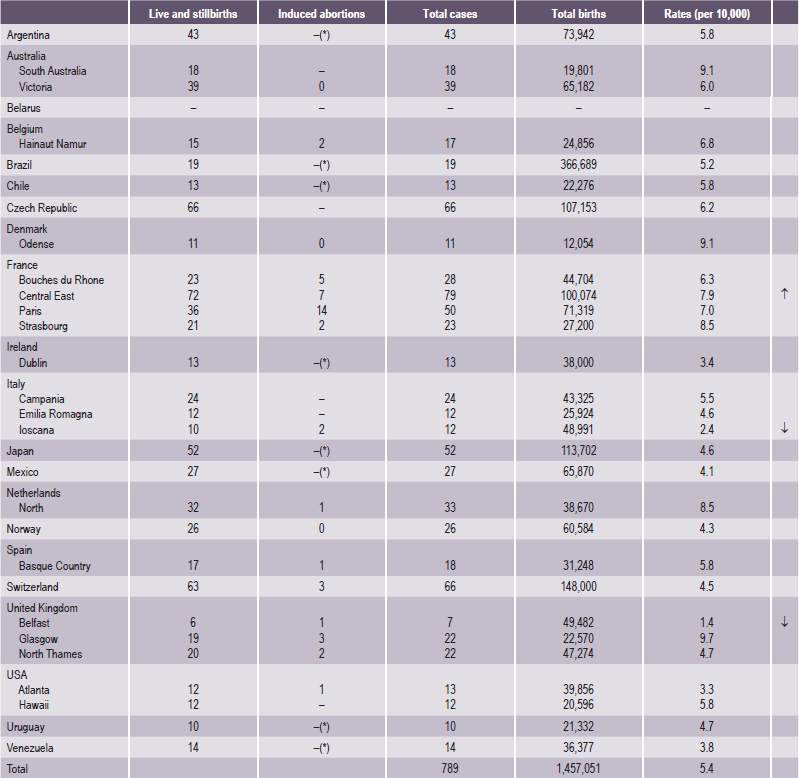

Table 1-3

Cleft palate without cleft lip

Source: WHO (1998), World Atlas of Birth Defects (1st Edition).

*Abortion for birth defect not permitted.

↑= 99% significantly higher than the mean.

↓= 99% significantly lower than the mean.

• The heterogeneity of orofacial clefting,

• The lack of standard criteria for collection of data, and

• In particular, the lack of and/or failure to apply an internationally comparable classification for orofacial clefting.

Defining the affected population is also problematic because, on many occasions, the terminology is so vague that it is not clear whether it denotes all birth, or all live births. The word ‘births’ is again somewhat ambiguous because it usually includes stillbirths, a term which lacks clarity.

Registration of Targeted Craniofacial Anomalies in India

1. Three multicenter studies in India have provided almost similar frequency of CFA: meta-analysis of 25 early studies from 1960–1979, involving 407,025 births, showed:

CL/P = 440 cases, 1.08 per 1,000 births,

CP = 95 cases, 0.23 per 1,000 births.

2. A prospective national study of malformations in 17 centers from all over India from September 1989 to September 1990 involving 47,787 births showed:

CL/P = 64 cases, 1.3 per 1,000 births,

CP = 6 cases, 0.12 per 1,000 births.

3. The latest three-center study, conducted in 1994–1996, involved 94,610 births in Baroda, Delhi and Mumbai, and showed a frequency of:

This was the most rigorously conducted study and it found the number of infants born every year with CLP to be 28,600; this means 78 affected infants are born every day, or three infants with clefts are born every hour (Table 1-4)!

CFA are not lethal but they are disfiguring, and thus cause a tremendous social burden. However, these disorders have an excellent outcome if surgical repair is carried out competently. Recent information regarding the etiology of CFA provides the means to carry out primary or secondary prevention. Maintaining a registry would be very useful as a benefit to the community and in reducing the burden of these anomalies, either by prevention or surgical repair.

Another reason why a registry would be desirable is the changing pattern of morbidity and mortality in India emerging as a result of the achievements in immunization, the success in providing primary health care and the existence of a well-developed health infrastructure. In many university and city hospitals congenital malformations and genetic disorders have become important causes of illness. All these reasons show that starting a registry of these disorders deserves high priority in India.

Existing epidemiological data on CFA

The epidemiological information that exists on CFA anomalies in India needs to be examined to decide what data should be collected for the registry:

• Higher frequency of CL+CP among Indian males is similar to that observed among Caucasians. The ratio is more than that observed in Africans and Japanese.

• The higher prevalence of CL+CP as compared with CL among Indians is like that observed in Africans, and is more than that observed in Caucasians.

• Children born prematurely are more frequently affected in India, as elsewhere.

• About 10.9% of 459 cases of all clefts are syndromic in Chennai. Of these, about 50 % are due to single-gene disorders, about 18% due to chromosomal disorders, and the rest due to undetermined causes.

• Chromosomal studies would be desirable in cases with associated abnormalities.

• Syndromes are more commonly associated with CP than with CL, as elsewhere.

• Lateralization (more clefts on the left side) in India is similar to that observed in other races.

• In one study in India, the intake of drugs was observed in 18% of parents — mostly steroidal compounds (progestogens as tests for pregnancy).

• A greater history of terminated pregnancies has been observed among cases, as compared with controls.

• History of severe vomiting has been observed to be about six times more common among case mothers than among controls.

• There is some difference in the frequency of orofacial clefts in different states in India; however, this needs verification. The state of origin (or mother tongue) of the parents should be recorded.

• Clefts are more commonly found in certain caste groups among Hindus.

• In India CP has less frequency in those with blood group A.

• CL occurs more in those with group O and AB.

• Association of clefts with certain HLA types has been documented in India.

• In a study in Chennai, significantly more consanguinity was observed among couples having children with clefts as compared with controls.

Genetics: Principles And Terminology

Genotype and Phenotype

The science of genetics is concerned with the inheritance of traits, whether normal or abnormal, and with the interaction of genes and the environment. This latter concept is of particular relevance to medical genetics, since the effects of genes can be modified by the environment.

Table 1-5

Genes involved in craniofacial and dental disorders, sorted by acronym gene name

| Acronym | Full name |

| ACTC | Actin, Alpha, Cardiac Muscle |

| APP | Amyloid Beta A4 Precursor Protein (APP) |

| ARVCF | Armadillo Repeat Gene Deleted in VCFS |

| ATP&E | ATPhase, H+ Transporting, Lysosomal, Subunit E |

| CA1 | Carbonic Anhydrase 1 |

| CLTCL1 | Clathrin, Heavy Polypeptide-Like 1 |

| COL01A1 | Collagen, Type I, Alpha-1 |

| COL01A2 | Collagen, Type I, Alpha-2 |

| COL02A1 | Collagen, Type II, Alpha-1 |

| COL04A4 | Collagen, Type IV, Alpha-4 |

| COL04A5 | Collagen, Type IV, Alpha-5 |

| COL05A1 | Collagen, Type V, Alpha-1 |

| COL06A1 | Collagen, Type VI, Alpha-1 |

| COL10A1 | Collagen, Type X, Alpha-1 |

| COMT | Catechol-O-Methyltransferase |

| CYLN2 | Cytoplasmic Linker 2 |

| DCN | Decorin |

| DGSI | DiGeorge Syndrome Critical Region Gene |

| ELN | Elastin |

| FBLN2 | Fibulin 2 |

| FBN1 | Fibrillin 1 |

| FGF8 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 8 |

| FGFR1 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 |

| FGFR2 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| FGFR3 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 3 |

| GNAS1 | Guanine Nucleotide-Binding Protein, Alpha-Stimulating Activity Polypeptide |

| GOLGA1 | Golgi Autoantigen, Golgin Subfamily A, 1 |

| GP1BB | Glycoprotein Ib, Platelet, Beta Polypeptide |

| GPC3 | Glypican 3 |

| GPC4 | Glypican 4 |

| GPR1 | G Protein-Coupled Receptor 1 |

| GTF2I | General Transcription Factor II-I |

| HIP1 | Huntingtin-interacting Protein 1 |

| HIRA | Histone Cell Cycle Regulation Defective, S. Cerevisiae, Homolog of, A |

| HOXD10 | Homeo Box D10 |

| ITGB2 | Integrin, Beta-2 |

| KRT04 | Keratin 4 |

| KRT06A | Keratin 6A |

| KRT06B | Keratin 6B |

| KRT13 | Keratin 13 |

| KRT16 | Keratin 16 |

| KRT17 | Keratin 17 |

| LAMB1 | Laminin, Beta-1 |

| MEOX2 | Mesenchyme Homeo Box 2 |

| MSX1 | MSH, Drosophila, Homeo Box, Homolog of, 1 |

| MSX2 | MSH (Drosophila) Homeo Box Homolog 2 |

| PNUTL1 | Peanut-Like 1 |

| PTHR1 | Parathyroid Hormone Receptor 1 |

| RO60 | Autoantigen Ro/SSA, 60–KD |

| SCZD | Schizophrenia |

| SCZD4 | Schizophrenia 4 |

| SCZD8 | Schizophrenia 8 |

| SRC | V-SRC Avian Sarcoma (Schmidt-Ruppin A-2) Viral Oncogene |

| SRY | Sex-Determining Region Y |

| SSA1 | Sjögren Syndrome Antigen A1 |

| SSB | Sjögren Syndrome Antigen B |

| TNFRSF11B | Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Superfamily, Member 11B |

| TTPA | Tocopherol Transfer Protein, Alpha |

| TWIST | Twist, Drosophila, Homolog of |

| WBSCR1 | Williams-Beuren Syndrome Chromosome Region 1 |

Source: Report of the National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research Genetics Workgroup, Meeting held November 14–16, 1999.

Consideration of the heritability of a particular feature or trait requires a consideration of the relationship between genotype and phenotype. Genotype is defined as the genetic constitution of an individual, and may refer to specified gene loci or to all loci in general. An individual’s phenotype is the final product of a combination of genetic and environmental influences. Phenotype may refer to a specified character or to all the observable characteristics of the individual. The proportion of the phenotypic variance attributable to the genotype is referred to as heritability.

Genetic variation in man may be observed at two levels:

In specific traits, individual genotypes are readily identified and differences are qualitative (discrete), for example, the ABO blood antigen system. Gene frequencies can be estimated and the Mendelian type of analysis can be applied.

In continuous traits such as height, weight or tooth size, differences are characterized quantitatively between individuals. These quantitative traits in man are more elusive to study because they are determined by the alleles of many gene loci, and therefore, the Mendelian type of analysis is not appropriate. They are further modified by environmental conditions which obscure the genetic picture. If the genetic variation of a particular phenotypic trait is dependent on the simultaneous segregation of many genes and affected by environment it is referred to as being subject to multifactorial inheritance. Genetic differences caused by the segregation of many genes is referred to as polygenic variation and the genes concerned are referred to as polygenes. These genes are, of course, subject to the same laws of transmission and have the same general properties as the single genes involved in qualitative traits, but segregation of genes is translated into genetic variations seen in continuous traits through polygenes.

Different types of genetic ‘product’ can be thought of as being different distances from the fundamental level of gene activity. Enzymes, for instance, are almost direct products of gene action, and in most cases where genetic variation of enzyme structure has been demonstrated, it has been shown that a single locus is responsible for the structure of a single enzyme. The structure, and consequently, the activity of an enzyme is therefore usually simply and directly related to allele substitutions at a single locus.

Morphological characters, on the other hand, such as the numerous dimensions used to describe the shape of the face and jaws, are furthest removed from the fundamental genetic level and are the end results of a vast complexity of interacting, hierarchical, biochemical, and developmental processes. Each gene is therefore likely to influence many morphological characters so that a deleterious mutation, although producing a unitary effect at the molecular level, almost always results in a syndrome of morphological abnormalities. When a gene is known to affect a number of different characters in this way its action is said to be pleiotropic. A reverse hierarchy also exists, making each morphological character dependent on many different genes (Mossey, 1999).

Modes of Inheritance

Population genetics deals with the study of the mode of inheritance of traits and the distribution of genes in populations.

All chromosomes exist in pairs so our cells contain two copies of each gene, which may be alike or may differ in their substructure and their product. Different forms of genes at the same locus or position on the chromosome are called alleles. If both copies of the gene are identical, the individual is described as homozygous, while if they differ, the term used is heterozygous.

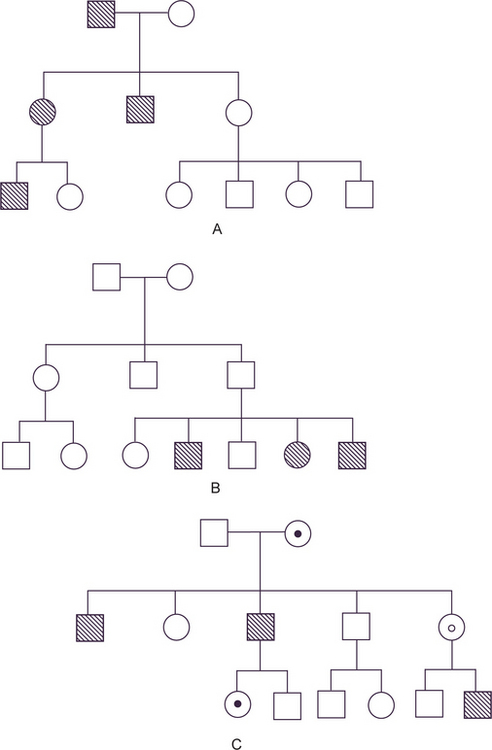

The exception to the rule that cells contain pairs of chromosomes applies to the gametes, sperm and ovum, which contain only single representatives of each pair of chromosomes, and therefore, of each pair of genes. When the two gametes join at fertilization, the new individual produced again has paired genes, one from the father and one from the mother. If a trait or disease manifests itself when the affected person carries only one copy of the gene responsible, along with one normal allele, the mode of inheritance of the trait is called dominant (Fig. 1-1A). If two copies of the defective gene are required for expression of the trait, the mode of inheritance is called recessive (Fig. 1-1B).

Figure 1-1 (A) Autosomal dominant pedigree. (B) Autosomal recessive pedigree. (C) X-linked recessive pedigree. Courtesy of PA Mossey, 1999.

The special case of genes carried on the X chromosome produces yet different pedigrees. Since male-to-male transmission is impossible and since females do not express the disease when they carry only one copy of the diseased gene (since it is modified by the homologous X chromosome), the usual pedigree consists of an affected male with clinically normal parents and children, but with affected brothers, maternal uncles, and other maternal male relatives (Fig. 1-1C). This mode of inheritance is described as X-linked recessive.

It has been long appreciated that many normal traits, such as height, intelligence, and birth weight, have a significant genetic component, as do a number of common diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, schizophrenia, hypertension, and cleft lip and palate. However, the pattern of inheritance of these traits does not follow the simple modes just described. Mathematical analysis of many of these has led to the conclusion that they follow the rules of polygenic inheritance, i.e. determined by a constellation of several genes, some derived from each parent.

The determination of heritability for polygenic or multifactorial characters is difficult, as a feature of continuous variation is that different individuals may occupy the same position on the continuous scale for different reasons. Using mandibular length as an example, micrognathia can occur in chromosomal disorders, such as Turner’s syndrome, in monogenic disorders such as Treacher Collins syndrome or Stickler syndrome, or due to an intrauterine environmental problem, such as fetal alcohol syndrome. Combined with this the concept of etiological heterogeneity encompasses the principle of the same gene defect producing different phenotypic anomalies, and syndromes can be due to defective gene activity in different cells. Conversely, different gene defects or combinations of defective genes can produce a similar phenotypic abnormality. Genetic lethality or reduced reproductive fitness can also complicate the diagnostic picture and genomic imprinting can result in a gene defect ‘skipping’ a generation. These complexities serve to hamper progress in the understanding of polygenic or multifactorial disorders such as orofacial clefting (Mossey, 1999).

Multifactorial Inheritance

In contrast to single-gene inheritance, either autosomal or sex-linked, the pedigree pattern does not afford a diagnosis of multifactorial inheritance. In multifactorial traits, the trait is determined by the interaction of a number of genes at different loci, each with a small, but additive effect, together with environmental factors (i.e., the genes are rendering the individual unduly susceptible to the environmental agents). Many congenital malformations (Table 1-6) and common diseases of adult life are inherited as multifactorial traits and these are categorized as either continuous or discontinuous.

Table 1-6

Extrinsic

Mechanical

Unstretched uterine and abdominal muscles

Small maternal size

Amniotic tear

Unusual implantation site

Uterine leiomyomas

Unicornuate uterus

Bicornuate uterus

Twin fetuses

Intrinsic

Malformational

Spina bifida

Other central nervous system malformations

Bilateral renal agenesis

Severe hypoplastic kidneys

Severe polycystic kidneys

Urethral atresia

Functional

Neurologic disturbances

Muscular disturbances

Connective tissue defects

Source: MM Cohen Jr, The Child with Multiple Birth Defects. Raven Press, New York, 1982, p 10. Cited by RJ Gorlin, MM Cohen, LS Levin. Syndromes of the Head and Neck, 3rd Ed, Oxford University Press; 1990, New York.

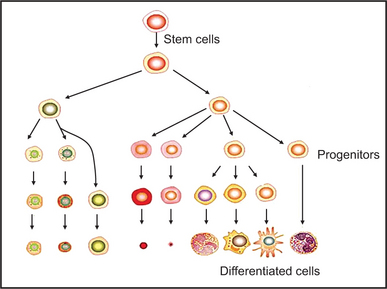

Molecular Genetics in Dental Development

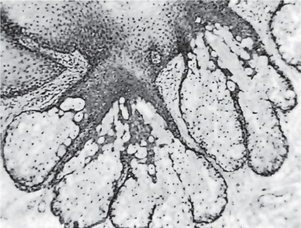

The first sign of tooth development is a local thickening of oral epithelium, which subsequently invaginates into neural crest derived mesenchyme and forms a tooth bud. Subsequent epithelial folding and rapid cell proliferation result in first the cap, and then the bell stage of tooth morphogenesis. During the bell stage, the dentine producing odontoblasts and enamel secreting ameloblasts differentiate. Tooth development, like the development of all epithelial appendages, is regulated by inductive tissue interactions between the epithelium and mesenchyme (Thesleff, 1995).

There is now increasing evidence that a number of different mesenchymal molecules and their receptors act as mediators of the epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during tooth development. Of the bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) 2, 4, and 7 mRNAs shift between the epithelium and mesenchyme in the regulation of tooth morphogenesis (Aberg et al, 1997). The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family have also been localized in epithelial and mesenchymal components of the tooth by immunohistochemistry (Cam et al, 1992); and in dental mesenchyme tooth development and shape is regulated by FGF8 and FGF9 via downstream factors MSX1 and PAX9 (Kettunen and Thesleff, 1998).

Control of Tooth Development

Homeobox genes have particular implications in tooth development. Muscle specific homeobox genes Msx-1 and Msx-2 appear to be involved in epithelial mesenchymal interactions, and are implicated in craniofacial development, and in particular, in the initiation developmental position (Msx-1) and further development (Msx-2) of the tooth buds (MacKenzie et al, 1991; Jowett et al, 1993). Further evidence of the role of Msx-1 comes from gene knock-out experiments which results in disruption of tooth morphogenesis among other defects (Satokata and Maas, 1994). Pax-9 is also transcription factor necessary for tooth morphogenesis (Neubuser et al, 1997). BMPs are members of the growth factor family (TGF) and they function in many aspects of craniofacial development with tissue specific functions. BMPs have been found to have multiple roles not only in bone morphogenesis, (BMP 5, for example, induces endochondral osteogenes is in vivo), but BMP 7 appears to induce dentinogenesis (Thesleff, 1995).

Congenital Deformations Of Head And Neck

These are common, and mostly resolve spontaneously within the first few days of postnatal life. When they do not, further evaluation may be necessary to plan therapeutic interventions that may prevent long-term consequences. Approximately 2% of infants are born with extrinsically caused deformations that usually arise during late fetal life from intrauterine causes. Approximately 30% of deformed infants have two or more deformations. Deformed infants tend to show catch-up growth during the first few postnatal months after release from the intrauterine environment. The common deformations considered under the craniofacial category are nasal, auricular and mandibular deformities.

Teratogenic Agents

Teratogens are agents that may cause birth defects when present in the fetal environment. Included under such a definition are a wide array of drugs, chemicals, and infectious, physical, and metabolic agents that may adversely affect the intrauterine environment of the developing fetus. Such factors may operate by exceedingly heterogeneous pathogenetic mechanisms to produce alterations of form and function as well as embryonic and/or fetal death (Gorlin et al, 1990).

The mechanisms of teratogenesis are selective in terms of the target and effect. Thus, characteristic patterns of abnormalities can be expected to be associated with particular teratogenic agents. However, the extent to which an individual may be adversely affected by exposure to a given teratogen varies widely. This depends on the following four factors:

It is of considerable interest to the dental profession that experimental studies of teratogenic agents have almost invariably revealed a variety of head, neck and oral malformations. Conway and Wagner have compiled a list of the most common malformations of the head and neck as shown in Table 1-7.

Developmental Disturbances of Jaws

Agnathia (Otocephaly, holoprosencephaly agnathia)

Agnathia is a lethal anomaly characterized by hypoplasia or absence of the mandible with abnormally positioned ears having an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. More commonly, only a portion of one jaw is missing. In the case of the maxilla, this may be one maxillary process or even the premaxilla. Partial absence of the mandible is even more common. The entire mandible on one side may be missing, or more frequently, only the condyle or the entire ramus, although bilateral agenesis of the condyles and of the rami also has been reported. In cases of unilateral absence of the mandibular ramus, it is not unusual for the ear to be deformed or absent as well. It is probably due to failure of migration of neural crest mesenchyme into the maxillary prominence at the fourth to fifth week of gestation (postconception). The prevalence is unknown and less than 10 cases are described. The prognosis of this condition is very poor and it is considered to be lethal.

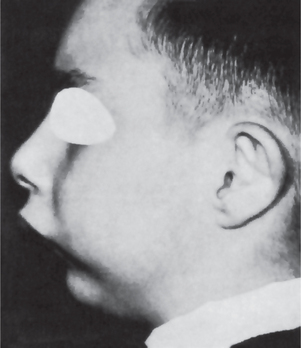

Micrognathia

Micrognathia literally means a small jaw, and either the maxilla or the mandible may be affected. Many cases of apparent micrognathia are not due to an abnormally small jaw in terms of absolute size, but rather to an abnormal positioning or an abnormal relation of one jaw to the other or to the skull, which produces the illusion of micrognathia.

True micrognathia may be classified as either congenital, or acquired. The etiology of the congenital type is unknown, although in many instances it is associated with other congenital abnormalities, including congenital heart disease and the Pierre Robin syndrome (q.v.) This form of the disease has been discussed by Monroe and Ogo. It occasionally follows a hereditary pattern. Micrognathia of the maxilla frequently occurs due to a deficiency in the premaxillary area, and patients with this deformity appear to have the middle third of the face retracted. Although it has been suggested that mouth-breathing is a cause of maxillary micrognathia, it is more likely that the micrognathia may be one of the predisposing factors in mouth-breathing, owing to the associated maldevelopment of the nasal and nasopharyngeal structures.

True mandibular micrognathia of the congenital type is often difficult to explain. Some patients appear clinically to have a severe retrusion of the chin but, by actual measurements, the mandible may be found to be within the normal limits of variation. Such cases may be due to a posterior positioning of the mandible with regard to the skull or to a steep mandibular angle resulting in an apparent retrusion of the jaw. Agenesis of the condyles also results in a true mandibular micrognathia.

The acquired type of micrognathia is of postnatal origin and usually results from a disturbance in the area of the temporomandibular joint. Ankylosis of the joint, for example, may be caused by trauma or by infection of the mastoid, of the middle ear, or of the joint itself. Since the normal growth of the mandible depends to a considerable extent on normally developing condyles as well as on muscle function, it is not difficult to understand how condylar ankylosis may result in a deficient mandible.

The clinical appearance of mandibular micrognathia is characterized by severe retrusion of the chin, a steep mandibular angle, and a deficient chin button (Fig. 1-3).

Micrognathia may be caused by or may be a feature of several conditions (Table 1-8).

Table 1-8

Congenital conditions

• Catel-Manzke syndrome

• Cerebrocostomandibular syndrome

• Cornelia de Lange syndrome

• Femoral hypoplasia—unusual facies syndrome

• Fetal aminopterin-like syndrome

• Miller-Dieker syndrome

• Nager acrofacial dysostosis

• Pierre Robin syndrome

• Schwartz-Jampel-Aberfeld syndrome

• van Bogaert-Hozay syndrome

Intrauterine acquired conditions

• Syphilis, congenital

Chromosomal abnormalities

• 49, XXXXX syndrome

• Chromosome 8 recombinant syndrome

• Cri du chat syndrome 5p

• Trisomy 18

• Turner’s syndrome

• Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome

Mendelian inherited conditions

• CODAS (cerebral, ocular, dental, auricular, skeletal) syndrome

• Diamond-Blackfan anemia

• Noonan’s syndrome

• Opitz-Frias syndrome

Autosomal dominant conditions

• Camptomelic dysplasia

• Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome

• CHARGE syndrome

• DiGeorge’s syndrome

• Micrognathia with peromelia

• Pallister-Hall syndrome

• Treacher Collins-Franceschetti syndrome

• Trichorhinophalangeal syndrome type 1

• Trichorhinophalangeal syndrome type 3

• Wagner vitreoretinal degeneration syndrome

Autosomal recessive conditions

• Bowen-Conradi syndrome

• Carey-Fineman-Ziter syndrome

• Cerebrohepatorenal syndrome

• Cohen syndrome

• Craniomandibular dermatodysostosis

• De la Chapelle dysplasia

• Dubowitz syndrome

• Fetal akinesia-hypokinesia sequence

• Hurst’s microtia-absent patellae-micrognathia syndrome

• Kyphomelic dysplasia

• Lathosterolosis

• Lethal congenital contracture syndrome

• Lethal restrictive dermopathy

• Marden-Walker syndrome

• Orofaciodigital syndrome type 4

• Postaxial acrofacial dysostosis syndrome

• Rothmund-Thomson syndrome

• Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

• ter Haar syndrome

• Toriello-Carey syndrome

• Weissenbacher-Zweymuller syndrome

• Yunis-Varon syndrome

X-linked inherited conditions

• Atkin-Flaitz-Patil syndrome

• Coffin-Lowry syndrome

• Lujan-Fryns syndrome

• Otopalatodigital syndrome type 2

Autoimmune conditions

• Juvenile chronic arthritis

Source: www.diseasesdatabase.com, Health on the Net Foundation, 2005.

Macrognathia

Macrognathia refers to the condition of abnormally large jaws. An increase in size of both jaws is frequently proportional to a generalized increase in size of the entire skeleton, e.g. in pituitary gigantism. More commonly only the jaws are affected, but macrognathia may be associated with certain other conditions, such as:

• Paget’s disease of bone, in which overgrowth of the cranium and maxilla or occasionally the mandible occurs,

• Acromegaly, in which there is progressive enlargement of the mandible owing to hyperpituitarism in the adult, or

• Leontiasis ossea, a form of fibrous dysplasia in which there is enlargement of the maxilla.

Cases of mandibular protrusion or prognathism, uncomplicated by any systemic condition, are a rather common clinical occurrence (Fig. 1-4). The etiology of this protrusion is unknown, although some cases follow hereditary patterns. In many instances the prognathism is due to a disparity in the size of the maxilla in relation to the mandible. In other cases the mandible is measur-ably larger than normal. The angle between the ramus and the body also appears to influence the relation of the mandible to the maxilla, as does the actual height of the ramus. Thus prognathic patients tend to have long rami which form a less steep angle with the body of the mandible. The length of the ramus, in turn, may be associated with the growth of the condyle. It may be reasoned, therefore, that excessive condylar growth predisposes to mandibular prognathism.

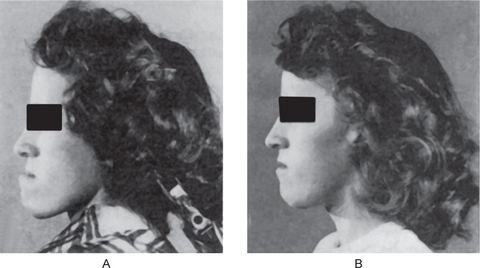

Figure 1-4 Macrognathia (prognathia) of the mandible. (A) The protrusion of the mandible is obvious. (B) The same patient after surgical correction (ostectomy) (Courtesy of Dr G Thaddeus Gregory and Dr J William Adams.

General factors which conceivably would influence and tend to favor mandibular prognathism are as follows:

• Increased height of the ramus

• Increased mandibular body length

• Anterior positioning of the glenoid fossa

• Posterior positioning of the maxilla in relation to the cranium

Surgical correction of such cases is feasible. Ostectomy, or resection of a portion of the mandible to decrease its length, is now an established procedure, and the results are usually excellent from both a functional and a cosmetic standpoint.

Facial Hemihypertrophy (Hyperplasia)

Hemihyperplasia is a rare developmental anomaly characterized by asymmetric overgrowth of one or more body parts. Although the condition is known more commonly as hemihypertrophy, it actually represents a hyperplasia of the tissues rather than a hypertrophy. Hemihyperplasia can be an isolated finding, but it also may be associated with a variety of malformation syndromes (Table 1-9). Almost all cases of isolated hemihyperplasia are sporadic.

Table 1-9

Malformation syndromes associated with hemihyperplasia

• Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

• Neurofi bromatosis

• Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome

• Proteus syndrome

• McCune-Albright syndrome

• Epidermal nevus syndrome

• Triploid/diploid mixoploidy

• Langer-Giedion syndrome

• Multiple exostoses syndrome

• Maffucci’s syndrome

• Ollier syndrome

• Segmental odontomaxillary dysplasia

Source: HE Hoyme et al, 1998.

Hoyme et al (1998) provided an anatomic classification of hemihyperplasia:

• Complex hemihyperplasia is the involvement of half of the body (at least one arm and one leg); affected parts may be contralateral or ipsilateral,

• Simple hemihyperplasia is the involvement of a single limb, and

• Hemifacial hyperplasia is the involvement of one side of the face.

Etiology

The cause is unknown, but the condition has been variously ascribed to vascular or lymphatic abnormalities; CNS disturbances; and chromosomal abnormalities.

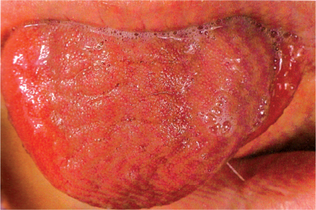

Clinical Features

Patients affected by facial hemihypertrophy exhibit an enlargement which is confined to one side of the body, unilateral macroglossia and premature development, and eruption as well as an increased size of dentition. Familial occurrence has been reported on a few occasions, according to the excellent review of the condition by Rowe, who described four additional cases. Of all reported cases, females are affected somewhat more frequently than males (63% versus 37%), according to the review by Ringrose. There is an almost equal involvement of the right and left sides.

Oral Manifestations

The dentition of the hypertrophic side, according to Rowe, is abnormal in three respects: crown size, root size and shape, and rate of development. Rowe has also pointed out that not all teeth in the enlarged area are necessarily affected in a similar fashion. There is little information about the effects on the deciduous dentition, but the permanent teeth on the affected side are often enlarged, although not exceeding a 50% increase in size. This enlargement may involve any tooth, but seems to occur most frequently in the cuspid, premolars, and first molar. The roots of the teeth are sometimes proportionately enlarged but may be short.

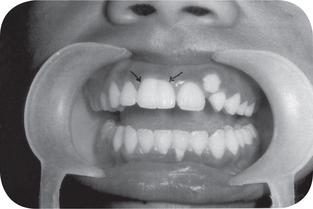

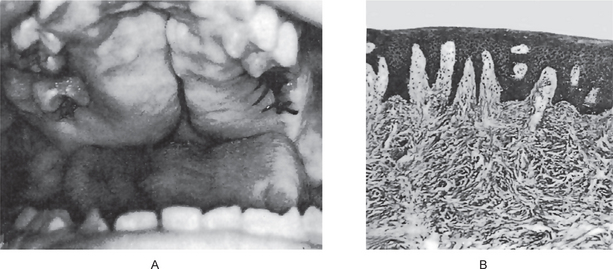

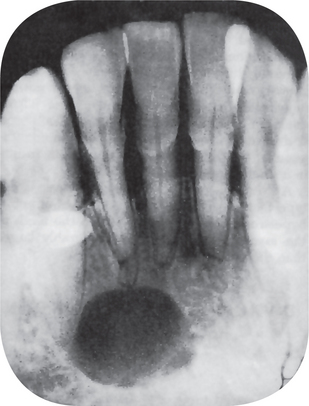

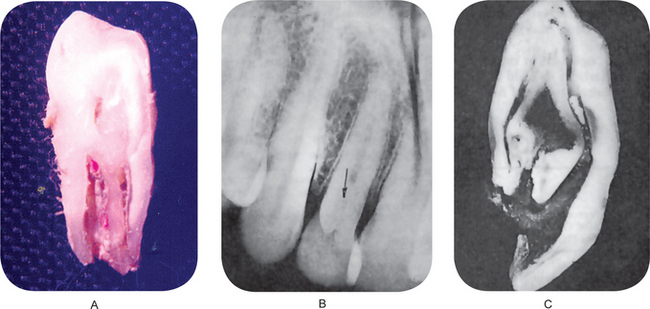

Characteristically, the permanent teeth on the affected side develop more rapidly and erupt before their counterparts on the uninvolved side (Fig. 1-5). Coincident to this phenomenon is premature shedding of the deciduous teeth. The bone of the maxilla and mandible is also enlarged, being wider and thicker, sometimes with an altered trabecular pattern.

Figure 1-5 Facial hemihypertrophy.

The difference in the eruption pattern of the teeth on each side is apparent. The teeth on the affected side, where all deciduous teeth have already been lost, are not appreciably larger than those on the unaffected side (Courtesy of Dr John B Wittgen.

The tongue is commonly involved by the hemihypertrophy and may show a bizarre picture of enlargement of lingual papillae in addition to the general unilateral enlargement and contralateral displacement. In addition, the buccal mucosa frequently appears velvety and may seem to hang in soft, pendulous folds on the affected side.

Histologic Features

Tissue examination has been infrequently reported but is generally uninformative. In those cases reported, true muscular hypertrophy was not found.

Treatment and Prognosis

There is no specific treatment for this condition other than attempts at cosmetic repair. Cosmetic surgery is advised after cessation of growth. Effect on life expectancy is not certain, but in some cases patients have lived a normal life span. Periodic abdominal ultrasound/ MRI is recommended to rule out tumors.

Facial Hemiatrophy (Parry-Romberg syndrome, Romberg-Parry syndrome, progressive facial hemiatrophy, progressive hemifacial atrophy)

Hemifacial atrophy remains almost as much an enigma today as it was when first reported by Romberg in 1846. Hemifacial atrophy, originally described by Parry and Henoch and Romberg consists of slowly progressive atrophy of the soft tissues of essentially half the face, which is characterized by progressive wasting of subcutaneous fat, sometimes accompanied by atrophy of skin, cartilage, bone and muscle. Although the atrophy is usually confined to one side of the face and cranium, it may occasionally spread to the neck and one side of the body and it is accompanied usually by contralateral Jacksonian epilepsy, trigeminal neuralgia, and changes in the eyes and hair. Evidence of a mendelian basis is lacking. Lewkonia and Lowry reported the case of a 16-year-old boy who developed facial changes at age seven and had localized scleroderma on one leg and the trunk. The presence of antinuclear antibodies in his serum suggested that the Parry-Romberg syndrome may be a form of localized scleroderma. Hemifacial atrophy is a form of localized scleroderma and is supported by its concurrence with scleroderma.

Hemifacial atrophy is a rare condition that occurs sporadically although some familial distribution has been found. The majority of cases are sporadic with no definite inheritance being proven in the literature.

Etiology

The etiology has been the subject of considerable debate. Wartenburg considered the primary factor to be a cerebral disturbance leading to increased and unregulated activity of sympathetic nervous system, which in turn produced the localized atrophy through its trophic functions conducted by way of sensory trunks of the trigeminal nerve. Other workers suggested extraction of teeth, local trauma, infection and genetic factors could also be a cause. In a paper published in 1973, Poswillo attributed the development of facial deformities to the disruption of the stapedial artery. Poswillo fed pregnant rats with triazine and pregnant monkeys with thalidomide and showed the consistent maldevelopment of first and second branchial arch structures. Robinson, in 1987, supported Poswillo’s theory by demonstrating carotid flow abnormalities in two and defects related to vascular disruption in a third child with craniofacial microsomia.

Clinical Features

Hemifacial atrophy is a syndrome with diverse presentation. The most common early sign is a painless cleft, the ‘coup de sabre,’ near the midline of the face or forehead. This marks the boundary between normal and atrophic tissue. A bluish hue may appear in the skin overlying atrophic fat.

The affected area extends progressively with the atrophy of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscles, bones, cartilages, alveolar bone and soft palate on that side of the face. In addition to facial wasting that may include the ipsilateral salivary glands and hemiatrophy of the tongue, unilateral involvement of the ear, larynx, esophagus, diaphragm, kidney and brain have been reported.

It starts in the first decade and lasts for about three years before it becomes quiescent. The final deformity varies widely, burning itself out in some patients with minimal atrophy, while in others progressing to marked atrophy.

Neurological disorders are found in 15% of patients, while ocular findings occur in 10–40%, the most common being enophthalmos.

Rarely, one half of the body may be affected. This condition may be accompanied by pigmentation disorders, vitiligo, pigmented facial nevi, contralateral Jacksonian epilepsy, contralateral trigeminal neuralgia and ocular complications.

The disease occurs more frequently in women; female to male ratio is 3 : 2. It has a slight predilection for the left side and appears in the first or second decades of life. It progresses over a period of two and 10 years, and atrophy appears to follow the distribution of one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve. The resulting facial flattening may be mistaken for Bell’s palsy (Fig. 1-6).

Oral Manifestations

Dental abnormalities include incomplete root formation, delayed eruption and severe facial asymmetry, resulting in facial deformation and difficulty with mastication. Hemiatrophy of the lips and the tongue is reported, as are dental effects. Foster has reported that growth of the teeth may be affected just as other tissues are involved. Eruption of teeth on the affected side may also be retarded.

Abnormalities of Dental Arch Relations

In the preceding sections the conditions discussed are those in which there is an actual or apparent abnormal variation in size of one or both jaws. Of far greater importance than a simple disparity in size is the disparity in relation of one jaw to the other and the difficulties in occlusion and function that result.

A great many different types of malocclusion exist, and many classifications have been evolved in an attempt to unify methods of treatment. The classification of Angle, proposed in 1899, is the most universally known and used. That classification, with the approximate percentage occurrence as determined by Angle in a large group of orthodontic patients, is as follows:

Class I. Arches in normal mesiodistal relations 69.0%.

Class II. Mandibular arch distal to normal in its relation to the maxillary arch.

Division 1. Bilaterally distal, protruding maxillary incisors 9.0.

Subdivision. Unilaterally distal, protruding maxillary incisors 3.5.

Division 2. Bilaterally distal, retruding maxillary incisors 4.0.

Subdivision. Unilaterally distal, retruding maxillary incisors 10.0.

Class III. Mandibular arch mesial to normal in its relation to the maxillary arch.

Since these abnormal jaw relations constitute a separate course of study, no further allusion to this subject will be made here.

Developmental Disturbances of Lips And Palate

Congenital Lip and Commissural Pits and Fistulas

Congenital lip pits and fistulas are malformations of the lips, often following a hereditary pattern, that may occur alone or in association with other developmental anomalies such as various oral clefts. Both Taylor and Lane and McConnel and his associates have emphasized that in 75–80% of all cases of congenital labial fistulas, there is an associated cleft lip or cleft palate, or both. The association of pits of the lower lip and cleft lip and/or cleft palate, termed van der Woude’s syndrome, has been reviewed by Cervenka and his associates.

Commissural pits are an entity probably very closely related to lip pits, but occur at the lip commissures, lateral to the typical lip pits. Everett and Wescott have described this entity and noted that it is also frequently hereditary, possibly a dominant characteristic following a Mendelian pattern, and may be associated with other congenital defects.

Etiology

Many theories of the etiology of congenital lip pits have been offered, but none has been universally accepted. Pits may result from notching of the lip at an early stage of development, with fixation of the tissue at the base of the notch, or from failure of complete union of the embryonic lateral sulci of the lip, which persist and ultimately develop into the typical pits.

Commissural pits are also difficult to explain, but they occur at the site of the horizontal facial cleft and may represent defective development of this embryonic fissure.

Clinical Features

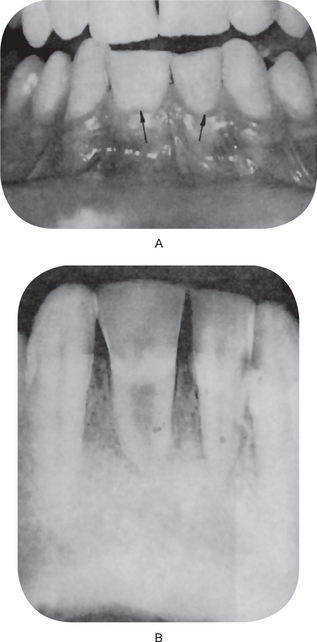

The lip pit or fistula is a unilateral or bilateral depression or pit that occurs on the vermilion surface of either lip but far more commonly on the lower lip (Fig. 1-7A). In some cases a sparse mucous secretion may exude from the base of this pit. The lip sometimes appears swollen, accentuating the appearance of the pits.

Figure 1-7 (A) Congenital lip pits. (B) Congenital commissural pits. Courtesy of Dr Spencer Lilly, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College, Chennai.

Commissural pits appear as unilateral or bilateral pits at the corners of the mouth on the vermilion surface (Fig. 1-7B). An actual fistula may be present from which fluid may be expressed. Whether this tract, either in lip or commissural fistulas, represents a true duct is not clear. Interestingly, in several cases preauricular pits have been reported in association with commissural pits.

van der Woude Syndrome (Cleft lip syndrome, lip pit syndrome, dimpled papillae of the lip)

van der Woude syndrome is an autosomal dominant syndrome typically consisting of a cleft lip or cleft palate and distinctive pits of the lower lips. The degree to which individuals carrying the gene are affected is widely variable, even within families. These variable manifestations include lip pits alone, missing teeth, or isolated cleft lip and palate of varying degrees of severity. Other associated anomalies have also been described.

Etiology

The most prominent and consistent feature of van der Woude syndrome is orofacial anomalies. They are due to an abnormal fusion of the palate and lips, at days 30–50 postconception. The van der Woude syndrome can be caused by deletions in chromosome band 1q32, and linkage analysis has confirmed this chromosomal locus as the disease gene site. The gene has been localized to chromosome band 1q32. Further studies have raised the possibility that the degree of phenotypic expression of a gene defect at this locus may be influenced by a second modifying gene that has been mapped to chromosome band 17p11.

Clinical Features

In general, van der Woude syndrome affects about 1 in 100,000–200,000 people. About 1–2% of patients with cleft lip or palate have van der Woude syndrome. The van der Woude syndrome affects both genders equally and no difference among them have been reported. The severity of the van der Woude syndrome varies widely, even within families. About 25% of individuals with the van der Woude syndrome have no findings or minimal ones, such as missing teeth or trivial indentations in the lower lips. Others have severe clefting of the lip or palate. The hallmark of the van der Woude syndrome is the association of cleft lip and/or palate with distinctive lower lip pits. This combination is seen in about 70% of those who are overtly affected but in less than half of those who carry the gene. The cleft lip and palate may be isolated. They may take any degree of severity and may be unilateral or bilateral. Submucous cleft palate is common and may be easily missed on physical examination. Hypernasal voice and cleft or bifid uvula are clues to this diagnosis. It is possible as well that a bifid uvula is an isolated finding in certain individuals with the van der Woude syndrome. The lower lip pits seen in this syndrome are fairly distinctive (Fig. 1-8). The pits are usually medial, on the vermilion portion of the lower lip. They tend to be centered on small elevations in infancy, but are simple depressions in adults. These pits are often associated with accessory salivary glands that empty into the pits, sometimes leading to embarrassing visible discharge. Occasionally lip pits may be the only manifestation of the syndrome. Affected individuals may have maxillary hypodontia; missing maxillary incisors or missing premolars. Again, this may be the only manifestation of the syndrome. Although infrequently reported, other oral manifestations include syngnathia (congenital adhesion of the jaws); narrow, high, arched palate; and ankyloglossia (short glossal frenulum or tongue-tie).

Extraoral Manifestations

The reported incidence of extraoral manifestations are rare but include limb anomalies, popliteal webs, and brain abnormalities. Accessory nipples, congenital heart defects, and Hirschsprung disease have also been reported. It is uncertain whether these extraoral manifestations are unassociated additional anomalies or infrequently expressed aspects of van der Woude syndrome.

Treatment

Along with a thorough orofacial examination, a thorough general physical examination helps to determine if there are other associated anomalies of the cardiovascular system, genitourinary system, limbs, or other organ systems. Examination and genetic counseling by a pediatric geneticist (dysmorphologist) is suggested for families that may be affected by the van der Woude syndrome. This should include an examination of as many potentially affected family members (probands) as possible. Surgical repair of the cleft lip and palate or other anomalies may be required, when planning surgical intervention, imaging studies of affected areas, such as CT scanning of the oropharynx, may be appropriate. Even among those less severely affected, surgical excision of lip pits is often performed, either to alleviate discomfort or for cosmetic reasons (e.g. improving the appearance of lip pits or reducing mucous discharge).

Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate

The term cleft lip and palate is commonly used to represent two types of malformation, i.e., cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P) and cleft palate (CP). Cleft lip and palate are common congenital malformations. The reported incidence of clefts of the lip and palate varies from 1 in 500 to 1 in 2500 live births depending on geographic origin, racial and ethnic background and socioeconomic status. In general, Asian population have the highest frequencies, often at 1 in 500 or higher, with Caucasian population intermediate, and Africanderived population the lowest at 1 in 2500.

An understanding of the normal human maxillofacial development is necessary before a discussion of cleft lip and palate. During the fourth week of gestation, the maxillary processes emerge from the first branchial arch on each side and the nasal placodes form from the frontal prominence. By the fifth week, all the primordia for the lip and palate are present. The medial, lateral nasal and the frontonasal processes are formed from the nasal placodes and the maxillary processes continue to enlarge. During the seventh week the medial nasal, frontonasal and maxillary processes fuse to form the primary palate, which becomes the medial portion of the upper lip, alveolus and the anterior part of hard palate up to the incisive foramen. When the primary palate is completely formed, the maxillary processes enlarge intraorally to form the palatine processes. During the 8th week of gestation, the palatal shelves fill up the space on both sides of the tongue. During the 9th and 10th weeks, the mandibular arch enlarges and the tongue drops. The palatal shelves transpose horizontally and fuse with each other and with the anterior part of the palate. Palatal fusion occurs anteroposteriorly and the process is completed by the 11th to 12th weeks (Shapiro, 1976).

Failure in the fusion of the nasal and maxillary processes leads to the cleft of the primary palate, which can be unilateral or bilateral. The degree of cleft can vary from a slight notch on the lip to complete cleft of the primary palate. Cleft of the secondary palate is medial. It varies from bifid uvula to complete cleft palate up to the incisive foramen. When it is associated with the primary palate, a complete uni- or bilateral cleft lip and palate is formed.

Etiology

It has been clearly established by Fogh-Andersen and confirmed by numerous other investigators that two separate and distinct entities exist:

Heredity is undoubtedly one of the most important factors to be considered in the etiology of these malformations. However, there is increasing evidence that environmental factors are important as well. According to Fogh-Andersen, slightly less than 40% of the cases of cleft lip with or without cleft palate are genetic in origin, whereas slightly less than 20% of the cases of isolated cleft palate appear to be genetically derived. Most investigations indicate that the inheritance pattern in cleft lip with or without cleft palate is different from that in isolated cleft palate. The mode of transmission of the defect is uncertain. This has been discussed by Bhatia, who pointed out that the possible main modes of transmission are either by a single mutant gene, producing a large effect, or by a number of genes (polygenic inheritance), each producing a small effect which together create this condition. It should be pointed out that cytogenetic studies have failed to reveal visible alterations in chromosomal morphology of the affected individuals.

Bixler more recently has expanded upon this concept and reiterated that there are two forms of clefts. The most common is hereditary, its nature being most probably polygenic (determined by several different genes acting together). In other words, when the total genetic liability of an individual reaches a certain minimum level, the threshold for expression is reached and a cleft occurs. Actually, it is presumed that every individual carries some genetic liability for clefting, but if this is less than the threshold level, there is no cleft. When the individual liabilities of two parents are added together in their offspring, a cleft occurs if the threshold value is exceeded. However, even though this is the most common form of cleft, the threshold value is sufficiently high that it is a low-risk type. The second form of cleft is monogenic or syndromic and is associated with a variety of other congenital anomalies. Since these are monogenic, they are of a high-risk type. Bixler has pointed out that, fortunately, the clefting syndromes are rare and probably make up only 5% of all cleft cases even though, according to Cohen, there are now over 300 clefting syndromes reported in the literature.

Although there is insufficient evidence that nutritional disturbances cause cleft palates in human beings, abnormal dietary regimens have caused developmental clefts in animals. Cleft palate has been experimentally produced in newborn rats by feeding diets either deficient or excessive in vitamin A to maternal rats during pregnancy. Riboflavin-deficient diets fed to pregnant rats have also produced offspring with a high incidence of cleft palate. The administration of cortisone to pregnant rabbits has induced similar clefts in their young.

Strean and Peer reported that physiologic, emotional, or traumatic stress may play a significant role in the etiology of human cleft palate, since stress induces increased function of the adrenal cortex and secretion of hydrocortisone. Their study, based on histories of 228 mothers of children with cleft palate, confirms the experimental findings of cleft palate in animals due to the action of stressor agents or the administration of cortisone. However, Fraser and Warburton have reported data which indicate that neither maternal emotional stress nor the lack of a prenatal nutritional supplement was causally related to the occurrence of cleft lip or cleft palate.

Other factors that have been suggested as possible causes of cleft palate include:

• A defective vascular supply to the area involved

• A mechanical disturbance in which the size of the tongue may prevent the union of parts

• Circulating substances, such as alcohol and certain drugs and toxins

Despite the numerous clinical and experimental investigations, the etiology of cleft palate in the human being is still largely unknown. It must be concluded; however, that heredity is probably the most important single factor.

Clinical Features

Cleft lip with or without palate is more common in males than in females. Males have also been reported to have more severe defects, whereas the isolated cleft palate is more common in females.

Clefts can be divided into nonsyndromic and syndromic forms. Syndromic forms of clefts include those cases that have additional birth defects like lip pits or other malformations, whereas nonsyndromic clefts are those cases wherein the affected individual has no other physical or developmental anomalies and no recognized maternal environmental exposures. At present, most studies suggest that about 70% of cases of cleft lip with or without palate and 50% of isolated cleft palate are nonsyndromic. The remaining syndromic cases can be subdivided into chromosomal anomalies, teratogens and uncategorized syndromes.

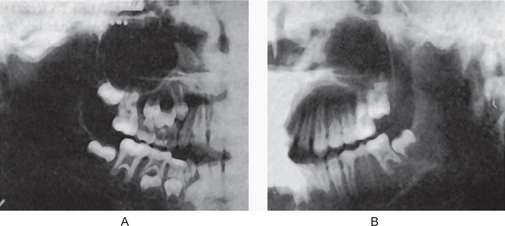

Cleft lip can occur as a unilateral (on the left or right side) or as a bilateral anomaly. The line of cleft always starts on the lateral part of the upper lip and continues through the philtrum to the alveolus between the lateral incisor and the canine tooth. The clefting anterior to the incisive foramen (i.e. lip and alveolus) is also defined as a cleft of primary palate. Cleft lip may occur with a wide range of severity, from a notch located on the left or right side of the lip to the most severe form, bilateral cleft lip and alveolus that separates the philtrum of the upper lip and premaxilla from the rest of the maxillary arch. When cleft lip continues from the incisive foramen further through the palatal suture in the middle of the palate, a cleft lip with palate (either unilateral or bilateral) is present (Figs. 1-9, 1-10). A wide range of severity may be observed. The cleft line may be interrupted by skin or mucosa bridges, hard (bone) bridges, or both, corresponding to a diagnosis of an incomplete cleft. This occurs in unilateral and bilateral CLP.

Figure 1-9 Cleft involving both the hard and the soft palates. Courtesy of Dr R Manikandan, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College, Chennai)

Figure 1-10 Cleft involving the soft palate only. Courtesy of Dr John M Tondra and Harold M Trusler.

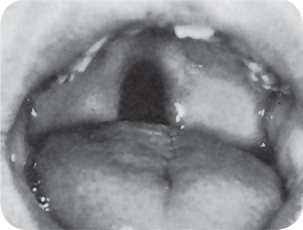

Isolated cleft palate is etiologically and embryologically different from cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Several subtypes of isolated cleft palate can be diagnosed based on severity. The uvula is the place where the minimal form of clefting of the palate is observed (Fig. 1-11). A more severe form is a cleft of the soft palate. A complete cleft palate constitutes a cleft of the hard palate, soft palate, and cleft uvula. The clefting posterior to the incisive foramen is defined as a cleft of secondary palate.

Figure 1-11 Cleft or biid uvula. Courtesy of Dr Manikandan R, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College, Chennai.

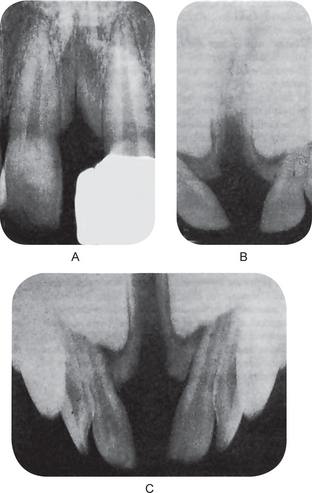

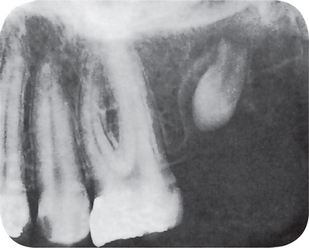

A median maxillary anterior alveolar cleft is a relatively common defect, occurring in approximately 1% of the population, according to Stout and Collett, but this is unrelated to cleft lip or cleft palate. This type of cleft has been discussed by Gier and Fast, who suggested that it might be due to precocious limitation of the growth of the primary ossification centers on either side of the midline at the primary palate, or to their subsequent failure to fuse. In addition, Miller and his coworkers have suggested that at least some cases may represent an incomplete manifestation of the median cleft-face syndrome (hypertelorism, median cleft of the premaxilla and palate, and cranium bifidum occultum). This syndrome has no clinical manifestations and is usually detected only on routine intraoral radiographic examination (Fig. 1-12).

Figure 1-12 Median maxillary anterior alveolar cleft.

All degrees of severity of the cleft may occur (Copyright by the American Dental Association. Reprinted by permission and by courtesy of Dr Arthur S Miller. From AS Miller, JN Greeley and DL Catena: Median maxillary anterior alveolar cleft: report of three cases. J Am Dent Assoc, 79: 896, 1969.

Clinical Significance

Most cases of cleft lip can be surgically repaired with excellent cosmetic and functional results. It is customary to operate before the patient is one month old or when he has regained his original birth weight and is still gaining.

Both the physical and psychologic effects of cleft palate on the patient are of considerable concern. Eating and drinking are difficult because of regurgitation of food and liquid through the nose. The speech problem is also serious and tends to increase the mental trauma suffered by the patient.

Most individuals with CL, CP, or both, require the coordinated care of providers in many fields of medicine and dentistry, as well as those in speech pathology, otolaryngology, audiology, genetics, nursing, mental health, and social medicine.

Treatment

Treatment of CLP anomalies requires years of specialized care. Although successful treatment of the cosmetic and functional aspects of orofacial cleft anomalies is now possible, it is still challenging, lengthy, costly, and dependent on the skills and experience of a medical team. This especially applies to surgical, dental, and speech therapies. Undoubtedly, closure of the CL is the first major procedure that tremendously changes children’s future development and ability to thrive. Variations occur in timing of the first lip surgery; however, the most usual time occurs at approximately three months of age. Pediatricians used to strictly follow a rule of ‘three 10s’ as a necessary requirement for identifying the child’s status as suitable for surgery (i.e. 10 lb, 10 mg/L of hemoglobin, and age 10 weeks). Although pediatricians are presently much more flexible, and some surgeons may well justify a neonatal lip closure, the rule of three 10s is still very useful.

Anatomical differences predispose children with CLP and with isolated CP to ear infections. Therefore, ventilation tubes are placed to ventilate the middle ear and prevent hearing loss secondary to otitis media with effusion (OME). In multidisciplinary teams with significant participation of an otolaryngologist, the tubes are placed at the initial surgery and at the second surgery routinely. The hearing is tested after the first placement when ears are clear with tubes. If no cleft surgery is planned early, placing the tubes by age six months and monitoring hearing with repeated testing is recommended. Complications include eardrum perforation and otorrhea, particularly in patients with open secondary palates in which closure is planned for a later date.

Cheilitis Glandularis (Actinic cheilitis, squamous cell carcinoma)

Cheilitis glandularis (CG) is a clinical diagnosis that refers to an uncommon and poorly understood inflammatory disorder of the lip. The condition is characterized by progressive enlargement and eversion of the lower labial mucosa that results in obliteration of the mucosal-vermilion interface. With externalization and chronic exposure, the delicate labial mucous membrane is secondarily altered by environmental influences, leading to erosion, ulceration, and crusting. Most significantly, susceptibility to actinic damage is increased. Therefore, CG can be considered a potential predisposing factor for the development of actinic cheilitis and squamous cell carcinoma.

Etiology

CG is an unusual clinical manifestation of cheilitis that evolves in response to one or more diverse sources of chronic irritation. Lip enlargement is attributable to inflammation, hyperemia, edema, and fibrosis. Surface keratosis, erosion, and crusting develop consequent to longstanding actinic exposure, unusual repeated manipulations that include self-inflicted biting or other factitial trauma, excessive wetting from compulsive licking, drying (sometimes associated with mouth-breathing, atopy, eczema, and asthma), and any other repeated stimulus that could serve as a chronic aggravating factor.

Clinical Features

In 1870, von Volkman introduced the term cheilitis glandularis. He described a clinically distinct, deeply suppurative, chronic inflammatory condition of the lower lip characterized by mucopurulent exudates from the ductal orifices of the labial minor salivary glands. In 1914, Sutton proposed that the characteristic lip swelling was attributable to a congenital adenomatous enlargement of the labial salivary glands. This remained the prevailing hypothesis until 1984 when Swerlick and Cooper reported five new cases and a retrospective analysis of all cases of CG reported until that time. Their studies revealed no evidence to support the assertion that salivary gland hyperplasia is responsible for CG.

Cheilitis glandularis is a chronic progressive condition. Patients typically present for diagnostic consultation within 3–12 months of onset. Complaints vary according to the nature and the degree of pain, the enlargement and the loss of elasticity of the lip, and the extent of evident surface change. Asymptomatic lip swelling initially occurs with clear viscous secretion expressible from dilated ductal openings on the mucosal surface. Some patients report periods of relative quiescence interrupted by transient or persistent painful episodes associated with suppurative discharge. A burning discomfort or a sensation of rawness referable to the vermilion border may be reported. This is associated with atrophy, speckled leukoplakic change, erosion, or frank ulceration with crusting. CG affects the lower lip almost exclusively. In more suppurative cases, application of gentle pressure can elicit mucopurulent exudate. Prolonged exposure to the external environment results in desiccation and disruption of the labial mucous membrane, predisposing it to inflammatory, infectious, and actinic influences. This is an uncommon condition. CG has been associated with a heightened risk for the development of squamous cell carcinoma. In many cases, dysplastic (premalignant) surface epithelial change is evident, and frank carcinomas have been reported in 18–35% of cases. The disorder appears to favor adult males; however, cases have been reported in both genders. The condition most frequently occurs between the fourth and seventh decades of life; however, the age range is wide. The risk of dysplasia and carcinoma increases with age, especially in fair-skinned individuals with sun-damaged skin. This is because the characteristic eversion of the lower lip results in long-term chronic exposure of the thinner, more vulnerable labial mucosa to actinic influence.

Classification

CG had historically been subclassified into three types, now believed to represent evolving stages in the severity of a single progressive disorder.

• In the simple type, multiple, painless, papular surface lesions with central depressions and dilated canals are seen.

• The superficial (suppurative) type (also referred to as Baelz disease) consists of painless, indurated swelling of the lip with shallow ulceration and crusting.

• CG of the deep suppurative type (CG apostematosa, CG suppurativa profunda, myxadenitis labialis) comprises a deep-seated infection with formation of abscesses, sinus tracts and fistulas, and potential for scarring.

The latter two types of CG have the highest association with dysplasia and carcinoma, respectively.

Histologic Findings

Lip biopsy is indicated to rule out specific granulomatous diseases that predispose to lip enlargement and aid in establishing a definitive diagnosis. A representative incisional biopsy specimen should consist of a wedge (or punch) of lip tissue that includes surface epithelium and is of adequate depth to ensure inclusion of several submucosal salivary glands. The term cheilitis glandularis is a provisional descriptive designation rather than a definitive diagnosis. It refers to a constellation of clinical findings that can reflect a broad scope of possible histologic changes; therefore, no consistent or pathognomonic features of this disorder are seen at the microscopic level. Instead, a diverse array of possible alterations can be seen in both the surface epithelium and the submucosal tissues. These findings best enable the clinician to presumptively determine the etiology and the nature of individual cases.

The minor salivary glands may appear normal under the microscope, or they may exhibit various changes indicative of nonspecific sialadenitis. These changes can include atrophy or distention of acini, ductal ectasia with or without squamous metaplasia, chronic inflammatory infiltration and replacement of glandular parenchyma, and interstitial fibrosis. Suppuration and sinus tracts may be present in cases that involve bacterial infection. Other possible histologic findings include stromal edema, hyperemia, surface hyperkeratosis, erosion, or ulceration.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses of this condition include actinic keratosis, atopic dermatitis, cheilitis granulomatosa (Miescher-Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome), sarcoidosis and squamous cell carcinoma.

Treatment

The approach to treatment is based on diagnostic information obtained from histopathologic analysis, the identification of likely etiologic factors responsible for the condition, and attempts to alleviate or eradicate those causes. In cases with acute or chronic suppuration, bacterial culture and sensitivity testing is indicated for selection of appropriate antibiotic therapy. Given the relatively small number of reported cases of CG, neither sufficient nor reliable data exist with regard to medical approaches to the condition. Therefore, treatment varies accordingly for each patient. In cases where a history of chronic sun exposure exists (especially if the patient is fair skinned or the everted lip surface is chronically eroded, ulcerated, or crusted), biopsy is strongly recommended to rule out actinic cheilitis or carcinoma.

Cheilitis Granulomatosa (Miescher-Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome)

Cheilitis granulomatosa is a chronic swelling of the lip due to granulomatous inflammation. Miescher cheilitis is the term used when the granulomatous changes are confined to the lip. Miescher cheilitis is generally regarded as a monosymptomatic form of the Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, although the possibility remains that these may be two separate diseases. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome is the term used when cheilitis occurs with facial palsy and plicated tongue. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome is occasionally a manifestation of Crohn’s disease or orofacial granulomatosis.

Etiology

The cause is unknown. A genetic predisposition may exist in Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome; siblings have been affected, and a plicated tongue may be present in otherwise unaffected relatives. Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis, and orofacial granulomatosis may present in a similar clinical fashion, and with identical histologic findings. Dietary or other antigens are the most common identified causes of orofacial granulomatosis. Contact antigens are sometimes implicated.

Clinical Features

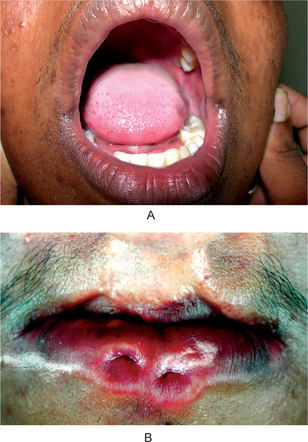

Cheilitis granulomatosa is episodic with nontender swelling and enlargement of one or both lips (Fig. 1-13). Occasionally, similar swellings involve other areas, including the periocular region. The first episode of edema typically subsides completely in hours or days. After recurrent attacks, swelling may persist and slowly increase in degree, eventually becoming permanent. Recurrences can range from days to years. Attacks sometimes are accompanied by fever and mild constitutional symptoms (e.g. headache, visual disturbance).

The earliest manifestation is sudden diffuse or occasionally nodular swellings of the lip or the face involving (in decreasing order of frequency) the upper lip, the lower lip, and one or both cheeks. The forehead, the eyelids, or one side of the scalp may be involved (less common). The upper lip is involved slightly more often than the lower lip, and it may feel soft, firm, or nodular on palpation. Once chronicity is established, the enlarged lip appears cracked and fissured with reddish brown discoloration and scaling. The fissured lip becomes painful and eventually acquires the consistency of firm rubber. Swelling may regress very slowly after some years. Regional lymph nodes are enlarged (usually minimally) in 50% of patients. A fissured or plicated tongue is seen in 20–40% of patients. Its presence from birth (in some patients) may indicate a genetic susceptibility. Patients may lose the sense of taste and have decreased salivary gland secretion. Facial palsy of the lower motor-neuron type occurs in about 30% of patients. Facial palsy may precede attacks of edema by months or years, but it more commonly develops later. Facial palsy is intermittent at first, but it may become permanent. It can be unilateral or bilateral, partial or complete. Other cranial nerves (e.g. olfactory, auditory, glossopharyngeal, hypoglossal) are occasionally affected. Poorly defined association of psychiatric and neurologic features are reported. Autonomic disturbances may occur. In granulomatous cheilitis, normal lip architecture is eventually altered by the presence of lymphedema and noncaseating granulomas in the lamina propria. The frequency is unknown; the condition is rare. Morbidity depends on whether underlying organic disease, such as Crohn’s disease or sarcoidosis, is present. There is no racial and sexual predilection. The age of onset is usually young adulthood.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include insect bites and sarcoidosis. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme test, chest radiography or gallium or positron emission tomography (PET) scanning may be performed to help exclude sarcoidosis. Gastrointestinal tract endoscopy and radiography may be used to help exclude Crohn’s disease.

Histologic Features

The histologic features of cheilitis granulomatosa and the swellings of the syndrome are rather characteristic, consisting of a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate—particularly peri- and para-vascular aggregations of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes—and focal noncaseating granuloma formation with epithelioid cells and Langhans type giant cells. The microscopic findings are suggestive of sarcoidosis, but as yet there is insufficient evidence to relate cheilitis granulomatosa with sarcoid.

Treatment

Patch tests may be used to help exclude reactions to metals, food additives, or other oral antigens. Some cases may be associated with such sensitivities. If found, avoidance of the implicated allergen is recommended. This condition can be conservatively managed by intralesional corticosteroid injections, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, mast cell stabilizers, clofazimine and tetracycline (used for antiinflammatory activity). Surgery and radiation have been reported to be used.

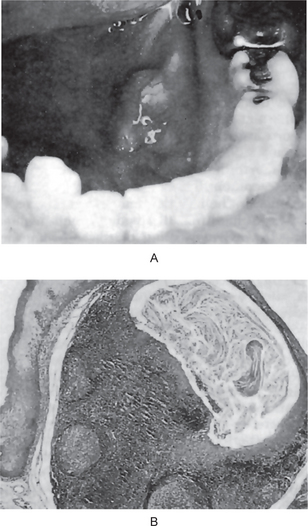

Hereditary Intestinal Polyposis Syndromen

(Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, intestinal hamartomatous polyps in association with mucocutaneous melanocytic macules)

The Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominantly inherited disorder characterized by intestinal hamartomatous polyps in association with mucocutaneous melanocytic macules. A 15-fold elevated relative risk of developing cancer exists in this syndrome over that of the general population; cancer primarily is of the GI tract, including the pancreas and luminal organs, and of the female and male reproductive tracts and the lung. The syndrome was named after Peutz, who noted a relationship between the intestinal polyps and the mucocutaneous macules in 1921, and after Jeghers, who is credited with the definitive descriptive reports in 1944 and later in 1949.

Etiology