CHAPTER 31 Pain management

At the completion of this chapter and with some further reading, students should be able to:

• Describe the physiological basis of pain perception

• Describe the factors influencing an individual’s perception of, and reaction to, pain

• Describe the differences in approach to pain assessment across the life span

• Describe various methods of pain management, including both non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches

• Apply appropriate principles in planning and implementing nursing actions to prevent and to alleviate an individual’s pain

Pain is a hugely subjective phenomenon which has been defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (1979) as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’. However, a timeless definition of pain that has been widely accepted and used by many nurses is that of McCaffery & Pasero (1999), a highly recognised pain care specialist. Her definition encompasses the idea that ‘pain is what the person says it is, and exists when he [sic] says it does’ (cited by Crisp & Taylor 2009). Pain is usually the chief reason why clients seek medical help. Nurses, due to their unique position as direct care workers, should be adequately equipped with cross-cultural, interdisciplinary and age-appropriate skills to assess and manage pain effectively. Thus the focus of this chapter, using a person-centred approach, is on the pathophysiology of pain, barriers to effective pain control and perception, assessment and treatment of pain.

If one of these nurses could experience my pain for just a single day, they might understand that I am not a drug addict.

FUNDAMENTALS OF PAIN

Pain is a phenomenon as simple as it is complex. For instance, individuals realise that sitting down can help relieve pain but prolonged sitting can then result in more pain. The same applies to activities of daily living such as walking, dancing and playing. What is even more baffling is that doing nothing for too long or being isolated can also result in pain. Individuals master ways to balance the environmental stimuli so that they avoid pain, such as by using an air-conditioner to control exposure to hot weather. However, it is impossible to always avoid pain as it is part of our daily living. It is also apparent that pain is multi-factorial in origin because of the various environmental factors associated with it; thus the experience and responses to pain are unpredictable. The unpredictability of the response to pain is also complicated by individual differences in age, personality, culture, previous experience, gender and race. This is why a precise clinical description of pain has eluded clinicians for decades.

Melzack and Casey published a model which describes pain in terms of three hierarchical levels: ‘a sensory-discriminative component (location, intensity and quality), a motivational–affective component (depression and anxiety) and a cognitive-evaluative component (thoughts concerning the cause and significance of the pain)’ (cited in Craft et al 2011). This description recognises that pain perception may not always be associated with diagnosable tissue damage and that it is hugely influenced by psychological and emotional factors. It also recognises that pain as an unpleasant experience does affect the mental status of people. Pain’s sensory-discriminative component constitutes its physiological role as a protective signal, a product of evolution and a warning of actual or impending tissue damage. Avoidance of pain appears to be an instinctive reaction to harmful factors in the environment; for example, a newborn will draw away from a painful stimulus (Craft et al 2011). Throughout the life cycle, people will avoid painful stimuli or take actions to withdraw from such stimuli. The sensation of pain can also warn the individual of emotional or stress-related problems, such as a headache caused by tension or anxiety. The ability to relieve or to control pain depends on an understanding of how it occurs and how it is controlled by the brain.

Although the complex mechanisms of the physiology and psychology of pain are not understood completely, there are several theories of pain. The gate control theory is the leading theory and a discussion of the other theories is beyond the scope of this chapter. The gate control theory of pain suggests that neural mechanisms in the dorsal horns of the spinal cord can act like a gate (Melzack & Wall 1965). This theory proposes that activity in the large diameter nerve fibres can close the gate and block pain impulses, resulting in a decrease or elimination of pain sensation. Therefore, according to this theory, it is possible to block pain impulses travelling to the brain by stimulating the large ‘A’ nerve fibres and ‘closing the gate’. This theory may help to explain the reason why cutaneous stimulation (rubbing a sore spot) or acupuncture can relieve pain, because stimulation of non-painful nerve fibres can ‘confuse’ messages and suppress pain signals.

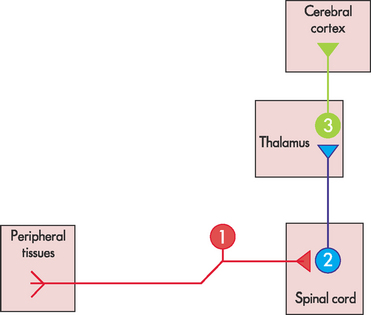

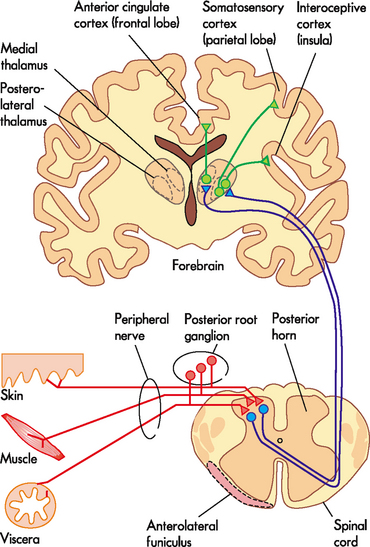

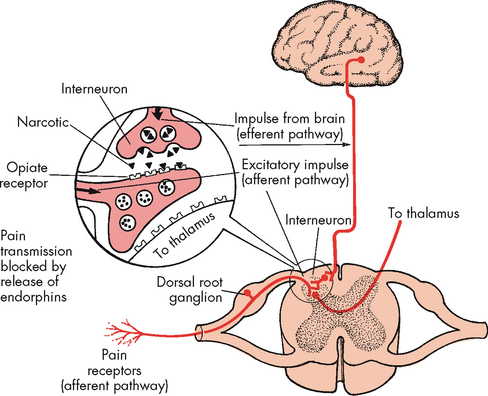

It is acknowledged that pain can be inhibited along the course of transmission (Figs 31.1 and 31.2) and that endorphins play a complex role in closing the gate to pain (Bryant & Knights 2011). Endorphins are naturally occurring substances with opioid qualities, which combine with the same receptors as do morphine and other narcotics to produce the same effect (i.e. analgesia) (Bryant & Knights 2011). They act as neurotransmitters that mediate the transmission of pain information. As a result of pain or stress, an impulse from the brain may trigger the release of endorphins from pain-inhibiting neurons in the dorsal horn, which block transmission of the pain impulse before it reaches the brain (Fig 31.3). Various studies have shown that plasma endorphin levels increase in states of stress, and also that acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) increase endorphin release. Therefore, although incompletely understood, it is known that the body has some internal mechanisms that help to control pain and its perception.

Figure 31.3 Modulation of pain by endorphins

(Huether SE & McCance KL (2008) Understanding Pathophysiology, 4th edn. St Louis: Mosby, Fig 13.3, p. 308)

Classification of pain

In order to manage pain effectively an understanding of the classification of pain is required. Pain can be classified according to the cause or pathology involved in its generation. This results in categories such as nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain, psychogenic pain and phantom pain (Table 31.1). The other classification of pain is based on duration of pain. The two main categories in this classification are acute and chronic pain (Table 31.2).

Table 31.1 Classification of pain based on aetiology or pathology

| Type of pain | Pathophysiology |

|---|---|

| Nociceptive |

This pain is caused by stimulation of nociceptors (peripheral nerve fibres). These peripheral nerve fibres have the capability to be responsive to noxious internal or external stimuli. Nociceptive pain can be classifed as somatic (deep or superfcial) originating from the skin and musculoskeletal system and visceral originating from damaged organs. Nociceptive pain is caused by ischaemia, trauma, chemical irritants and extremes of temperature. When pain receptors are stimulated they send electrical impulses along special pathways to the spinal cord. These pathways may be seen as being similar to a two-lane road, one lane with large diameter fibres for fast message transmission (‘A’ fibres), and one lane with smaller diameter fibres for slower message transmission (‘C’ fibres). ‘A’ fibres have the most insulation, and carry information that refects throbbing and pricking types of pain. Slow pathways (‘C’ fibres) have less insulation, and carry impulses that represent burning pain. Pain receptors in the skin and other tissues are free nerve endings, some of which are the peripheral terminations of small diameter ‘C’ fibres, while others are the slightly larger diameter ‘A’ fibres. When histamine and other naturally occurring chemical substances are released as a result of tissue damage, pain sensations travel along the nerve fibres. Regardless of the type of pain, and whether travelling slowly or quickly, pain impulses are transmitted to the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, where they synapse with certain neurons in the posterior horns of the grey matter. Pain sensations are then transmitted to various areas of the brain by synapses at the thalamus, where they are perceived and interpreted (Fig 31.2) |

| Neuropathic | Pain resulting from the damage or malfunction of nerve fibres in the peripheral and/or central nervous system. The nerve fibres could be located in the periphery or central sections of the nervous system. The resulting pain is often described as burning or pins and needles |

| Psychogenic | Hugely complex pain which is not fully acknowledged or understood. This pain exists in the absence of known pathophysiology and it is associated with mental and emotional behaviours |

| Phantom | Pain sensation resulting from body parts that have been surgically removed |

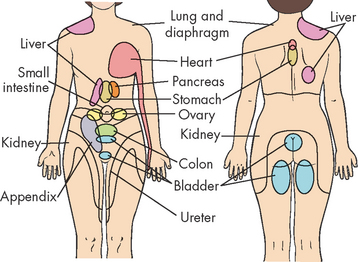

| Referred | Pain which originates from visceral organs but is felt on cutaneous areas suggesting some embryonic origin. A good example is cardiac pain which is also felt in the neck and shoulders (Fig 31.4) |

Table 31.2 Classification of pain based on duration

Berman et al 2012; IASP 2011; National Pain Summit Initiative 2010; WHO 2007

PAIN MANAGEMENT ACROSS THE LIFE SPAN

Pain management is the use of pharmacological or non-pharmacological nursing interventions to comprehensively treat discomfort and improve or restore the quality of life. Pain management involves vigilant monitoring of comfort using a multidisciplinary approach and not the mere administration of prescribed analgesics. The major goal is to eliminate pain and improve the quality of life and function. In palliative care, pain management allows clients to die with dignity.

The nurse, by virtue of spending 24 hours a day with clients, is in a position to make the greatest impact in the diagnosis and treatment of pain. As described previously, pain is a hugely subjective experience, and therefore difficult to diagnose objectively. It is thus vital for nurses to be cognisant of the fact that pain is a lived experience, a product of the continuous conflict between the internal and external stimuli and the whole individual (International Association for the Study of Pain 2011). Therefore, the nurse has an important responsibility to observe the client for visible evidence of pain, listen carefully to the client’s description of pain and implement measures that prevent or treat pain. The nurse also has a responsibility to monitor and report the client’s response to, and the efficacy of, any prescribed pain management. From a medical point of view, the management of pain includes treating the underlying disease to remove or diminish the cause; treating any other symptoms such as nausea or constipation that may increase the perception of pain; and using non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapy. Specific nursing interventions as described later in this chapter include minimising the stimulus that is causing or contributing to the pain, alleviating pain with supportive nursing intervention and assisting the client to cope with pain. It must be recognised that even the simple provision of information and explanation can have a powerful effect in assisting people to feel in control of their pain-management situation.

Barriers to effective pain management

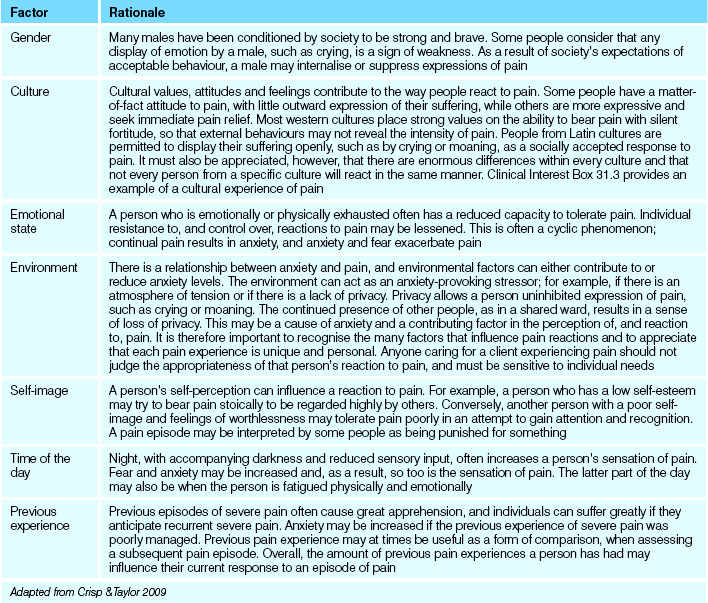

There are multiple barriers to adequate pain management; this places clients at risk for undertreatment. The major problem is that clients have to self-report. Clients recognised to be at risk are those in the extremes of age, that is, children and the elderly. Clients with psychiatric disorders, who are cognitively impaired, have substance abuse problems and clients suffering from chronic pain are also at risk of undertreatment of pain. It is important, therefore, to analyse factors that can influence the perception of pain. The perception of pain is individual and is therefore different for each person. Table 31.3 outlines the factors that can influence the perception of pain across the life span. In addition, a person may perceive pain differently at different times. Clinical Interest Box 31.1 provides some common biases and misconceptions about pain.

Table 31.3 Factors influencing the perception of pain across the life span

| Factor | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Age |

As infants and young children lack the ability to express themselves verbally, their pain, or the degree of pain they experience, may not be recognised or appreciated. Many misconceptions exist in relation to pain in infants, including that infants do not feel pain or are incapable of expressing pain. In addition to the physiological changes, behavioural cues, such as facial activity (including brow bulge, eye squeeze and open lips), crying behaviour and gross motor activity, may indicate pain in the infant. Additionally, many children are taught from an early age that they are expected to be brave and that ‘only babies cry’. As a result, a child who is experiencing pain may endeavour to hide it. Conversely, a child may invent or exaggerate pain as a method of gaining attention. When older children or adolescents experience pain they may think of it in terms of how it will affect their activities and the attainment of goals. As a result of misunderstanding about their body and illness, young clients sometimes harbour distressing fantasies about the signifcance of pain. Consequently, both anxiety and pain are increased. The ability to tolerate pain generally seems to increase with age, and this may be partly due to expectations about what constitutes ‘adult’ behaviour. Many myths also exist, however, in relation to pain experienced by older adults, particularly those with cognitive impairment. This has resulted in an underestimation and undermanagement of pain in people with disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical Interest Box 31.2 provides more information about pain management in clients with Alzheimer’s disease. Common misconceptions include that pain is a natural consequence of growing old, that pain perception decreases with age and that, if the older adult does not report pain, they do not have pain |

| Gender | Many males have been conditioned by society to be strong and brave. Some people consider that any display of emotion by a male, such as crying, is a sign of weakness. As a result of society’s expectations of acceptable behaviour, a male may internalise or suppress expressions of pain |

| Culture | Cultural values, attitudes and feelings contribute to the way people react to pain. Some people have a matter-of-fact attitude to pain, with little outward expression of their suffering, while others are more expressive and seek immediate pain relief. Most western cultures place strong values on the ability to bear pain with silent fortitude, so that external behaviours may not reveal the intensity of pain. People from Latin cultures are permitted to display their suffering openly, such as by crying or moaning, as a socially accepted response to pain. It must also be appreciated, however, that there are enormous differences within every culture and that not every person from a specific culture will react in the same manner. Clinical Interest Box 31.3 provides an example of a cultural experience of pain |

| Emotional state | A person who is emotionally or physically exhausted often has a reduced capacity to tolerate pain. Individual resistance to, and control over, reactions to pain may be lessened. This is often a cyclic phenomenon; continual pain results in anxiety, and anxiety and fear exacerbate pain |

| Environment | There is a relationship between anxiety and pain, and environmental factors can either contribute to or reduce anxiety levels. The environment can act as an anxiety-provoking stressor; for example, if there is an atmosphere of tension or if there is a lack of privacy. Privacy allows a person uninhibited expression of pain, such as crying or moaning. The continued presence of other people, as in a shared ward, results in a sense of loss of privacy. This may be a cause of anxiety and a contributing factor in the perception of, and reaction to, pain. It is therefore important to recognise the many factors that influence pain reactions and to appreciate that each pain experience is unique and personal. Anyone caring for a client experiencing pain should not judge the appropriateness of that person’s reaction to pain, and must be sensitive to individual needs |

| Self-image | A person’s self-perception can influence a reaction to pain. For example, a person who has a low self-esteem may try to bear pain stoically to be regarded highly by others. Conversely, another person with a poor self-image and feelings of worthlessness may tolerate pain poorly in an attempt to gain attention and recognition. A pain episode may be interpreted by some people as being punished for something |

| Time of the day | Night, with accompanying darkness and reduced sensory input, often increases a person’s sensation of pain. Fear and anxiety may be increased and, as a result, so too is the sensation of pain. The latter part of the day may also be when the person is fatigued physically and emotionally |

| Previous experience | Previous episodes of severe pain often cause great apprehension, and individuals can suffer greatly if they anticipate recurrent severe pain. Anxiety may be increased if the previous experience of severe pain was poorly managed. Previous pain experience may at times be useful as a form of comparison, when assessing a subsequent pain episode. Overall, the amount of previous pain experiences a person has had may influence their current response to an episode of pain |

Adapted from Crisp & Taylor 2009

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 31.1 Common biases and misconceptions about pain

The following statements are false:

• Substance abusers and alcoholics overreact to discomforts

• Clients with minor illnesses have less pain than those with severe physical alteration

• Administering analgesics regularly will lead to drug addiction

• The amount of tissue damage in an injury can accurately indicate pain intensity

• Healthcare personnel are the best authorities on the nature of a client’s pain

• Psychogenic pain is not real

• Chronic pain is psychological

As the perception of pain is individual, some will experience pain much earlier than others. Studies have shown that all individuals have a similar sensation threshold but that the ways in which different people react to pain may vary tremendously and many factors may be involved (see Clinical Interest Boxes 31.2 and 31.3). Behavioural manifestations of pain vary according to both the individual and to factors in the environment. The pain threshold is the point at which a stimulus, such as pressure, activates pain receptors and produces a sensation of pain (International Association for the Study of Pain 2011).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 31.2 Pain management in clients with Alzheimer’s disease

No evidence exists that cognitively impaired older adults experience less pain or that their reports of pain are less valid than those people with intact cognitive function. It is probable that clients with dementia and progressive deficits of cognition, particularly those in long-term care facilities, suffer significant unrelieved pain and discomfort. Assessing pain in these clients is challenging but possible. The best approach is to accept the client’s report of pain and treat the pain as it would be treated in a person with intact cognitive function.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 31.3 A cultural experience of pain

Certain religious groups, for example, Muslims, may believe that it is God’s will for them to experience pain. Some clients may be unwilling to accept medication in case it clouds or impairs their senses. Buddhists, for example, may prefer to use meditation techniques to help relieve their pain.

Assessing pain

The assessment process involves obtaining both subjective and objective data (Table 31.4). The data must be comprehensive, covering both the physiological and the behavioural manifestations (Clinical Interest Box 31.4) of pain. The questions must be designed to enable the client to describe the pain in their own words. A nurse should never ignore a client’s statement that they are in pain, and should remember that ‘pain is what the person says it is’. A client can usually sense if the nurse does not believe that they are experiencing pain, and this can increase the sense of helplessness. As a consequence, the client may compensate by under-reporting pain or by anxiously over-reporting. Either reaction aggravates the circle of mistrust–anxiety–more pain. When assessing a client’s pain, the nurse should obtain sufficient and appropriate information through observation, questioning and conducting a physical examination.

| Subjective data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Domain | Assessment questions | Rationale |

| Pain history |

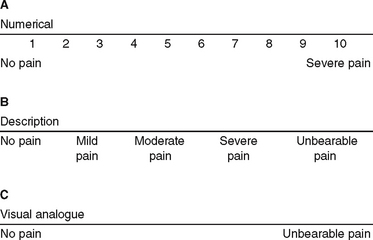

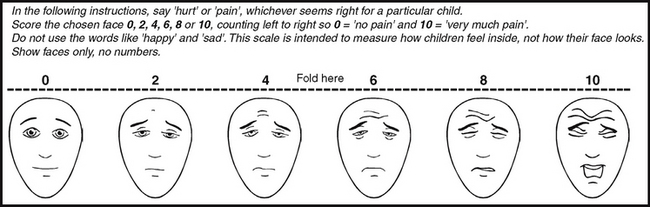

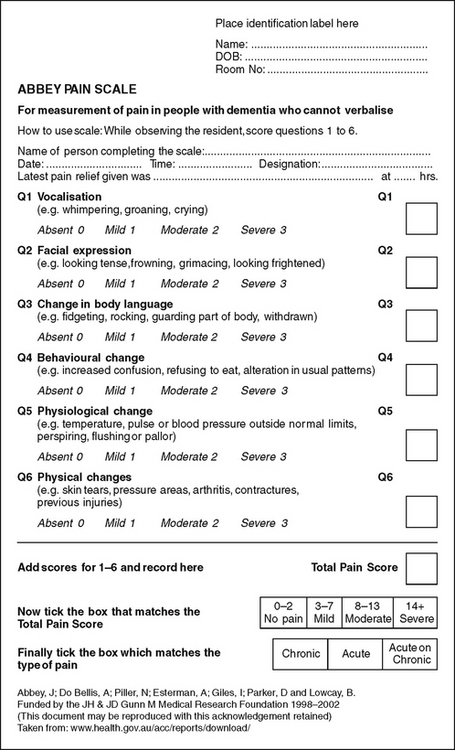

A client may be able to locate a painful area specifically, by describing it or by pointing to the body area involved, such as the tip of the thumb on the left hand, or they may describe the painful area more generally, for example, all over the abdomen. Pain that radiates from its point of origin should also be noted. Information should be obtained regarding the onset of pain; for example, whether it was sudden or gradual. The client should also be asked if the pain increases or decreases at specific times of the day or night; that is, if there is rhythmic variation or pattern in the pain. For example, a client who has arthritis aggravated by inactivity may experience severe joint pain on waking, but the pain may become less severe throughout the day. It is important to establish how long the pain lasts; for example, whether it is continuous or intermittent. Certain physical activities or psychological factors may precipitate pain. For example, chest pain may occur after physical exercise, or abdominal pain may occur after eating. A change of posture may aggravate or relieve pain, and factors such as anxiety or fear may also precipitate pain. It is important to establish factors that aggravate the pain as well as those that modify or bring about pain relief. This is the way the pain is described by the person who is experiencing it, and it is important for the nurse to report and record the client’s own words. Some of the terms that may be used to describe the type and quality of pain are gripping, knife-like, burning, prickling, tingling, dull, aching, cramping, gnawing, constricting, throbbing, vice-like, crushing, stabbing and shooting. The severity of pain is not always evident from a person’s reaction, especially with a chronic pain problem, and must therefore be assessed as the client’s own perception. Several measurement tools, or pain scales (Fig 31.5), have been designed to assist a client to describe the intensity of pain. Healthcare institutions may devise their own measurement tool, or may use a standard tool. One method of assessment is a linear scale from 1–10, on which the client indicates the intensity of their pain, with 0–1 being no pain at all, and 10 representing severe and intense pain. A similar scale using ‘smiley faces’ may be used for children (Fig 31.6). This type of measurement device facilitates both assessment and management of pain in many cases. However, the use of pain-scale assessment tools makes the assumptions that the client has a past experience of pain, that they can understand the scale and verbalise, and that they are not cognitively impaired. With elderly clients, issues such as poor memory, depression and sensory impairment may also make pain assessment diffcult. The Abbey Pain Scale (Fig 31.7) is a measurement of pain in people with dementia who cannot verbalise |

|

| Medication history | These questions give invaluable information which can help with diagnosing the cause of the pain. This information can also shape treatment | |

| Cognitive dimensions | A person’s self-perception can influence a reaction to pain. For example, a person who has a low self-esteem may try to bear pain stoically to be regarded highly by others. Conversely, another person with a poor self-image and feelings of worthlessness may tolerate pain poorly in an attempt to gain attention and recognition. A pain episode may be interpreted by some people as being punished for something | |

| Psychological status | A person who is emotionally or physically exhausted often has a reduced capacity to tolerate pain. Individual resistance to, and control over, reactions to pain may be lessened. This is often a cyclic phenomenon—continual pain results in anxiety, and anxiety and fear exacerbate pain | |

| Social and family history | Assessment should include whether or not the pain interferes with lifestyle or the performance of any activities of daily living; for example, does it affect the ability to eat, move freely or sleep? Are roles and relationships being affected in a significant way by the pain that is being experienced? | |

| Cultural and spiritual influences | Cultural values, attitudes and feelings contribute to the way people react to pain. Some people have a matter-of-fact attitude to pain, with little outward expression of their suffering, while others are more expressive and seek immediate pain relief | |

| Objective data | |

|---|---|

| Domain | Rationale |

| Vital signs | The client’s temperature, pulse, respirations and blood pressure should be measured when pain is first experienced. When acute pain occurs the autonomic response is activated, so that: |

|

These physiological changes are often less observable in a person with chronic pain. Over time the changes are unable to be sustained, and the individual with chronic pain may exhibit a general appearance of not being in pain. The results should be documented, and repeated measurements made to detect any alterations. Any abnormal result or significant variation should be reported immediately |

|

| Physical examination | The client should be observed for signs of increased emotional tension, such as irritability, anxiety, depression, aggression, exhaustion or sleeplessness. When a client experiences pain or a change in the nature of pain already present, the nurse should monitor and assess by making the observations as described. Clinical Interest Box 31.4 outlines some behavioural indicators of the effects of pain. A simple head-to-toe assessment is also warranted to make sure that there are no mechanical objects that may be the cause of pain such as a blocked catheter |

| Investigations | The medical officer may order further investigations which may help diagnose the source of pain |

Adapted from Brown & Edwards 2012 and Crisp & Taylor 2009

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 31.4 Behavioural indicators of effects of pain

Assessment tools

There is a variety of pain assessment tools used for clients across the life span (Figs 31.5, 31.6, 31.7). The aim of these tools is to standardise and objectify assessment. These tools include:

• Numeric rating scale (NRS) (Fig 31.5A)

• Categorical or verbal descriptor scale (VDS) (Fig 31.5B)

• Visual analogue scale (VAS) (Fig 31.5C)

• Faces scale (Fig 31.6)

Figure 31.5 Scales for measuring pain intensity in adults. The individual identifies a point on the scale that corresponds to their perception of the severity of the pain

Revised (Hicks, von Baeyer, Spafford, van Korlaar, Goodenough: Pain (2001); 93(2):173–83. Used with permission from IASPÆ. See www.painsourcebook.ca for instructions on use of the scale)

Figure 31.7 The Abbey Pain Scale

(Abbey J, Do Bellis A, Piller N, Esterman A, Giles I, Parker D, Lowcay B. Funded by the JH & JD Gunn Medical Research Foundation 1998–2002. (This document may be reproduced with this acknowledgement retained.) Taken from: www.health.gov.au/acc/reports/download/

NURSING INTERVENTIONS FOR A CLIENT EXPERIENCING PAIN

The nurse has a responsibility to try to eliminate or minimise the stimulus that is causing pain. The nurse also observes the client who is experiencing pain, reports and documents their observations and implements nursing measures to alleviate pain. Continued assessment and monitoring of the client is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of any prescribed therapy. Particular attention must be paid to clients who cannot clearly articulate their needs or feelings, such as infants and small children and those with cognitive or communicative impairment. Pain management, both of non-pharmacological and pharmacological nature, must still be addressed in these situations, and responses evaluated. The nurse also plays an important role in supporting the client’s significant others, who are usually distressed by the pain experience of their loved one, particularly when the pain is chronic or is a result of terminal illness.

The importance of clear and effective communication between the nurse and the client and significant others cannot be overemphasised. A positive relationship facilitates effective communication, which can affect the client’s response to pain and pain relief. The client should be encouraged to express feelings openly, in an atmosphere of trust. The nurse should learn to listen actively to the client, so that not only the verbal interactions are heard but any nonverbal cues are also detected and acted on. For example, clients may deny pain or state that they are not experiencing much pain, but the body language and tone of voice may indicate otherwise. To promote peace of mind and to reduce anxiety, clients should be provided with information about their illness, including expected pain and its management. Clients should be aware that they have a right to pain relief and that various pain-relieving measures are available. It is important to prevent or reduce the cycle of pain–stress–anxiety–pain. A variety of nursing measures, some very simple, may help to minimise or alleviate pain (Table 31.5).

Table 31.5 Nursing measures to improve client comfort

| Nursing action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Change of position | At times pain can result from, or be increased by, an uncomfortable posture. The client should be assisted into a more comfortable position, with appropriate pillows arranged for support. The addition of a sheepskin underneath the back and buttocks may enhance comfort, and the bedclothes should be arranged to meet individual needs. It is important to ensure that the client’s body is in alignment, and the placement of a pillow under a painful limb may further enhance comfort. Correct positioning should ensure that there is no undue stress on incisions, and no tension applied to any tubing present (surgical drain tube or urinary catheter) |

| Meet general comfort needs | The nurse should ensure that all basic comfort needs are provided for; for example, discomfort and pain can result from a distended bladder. The client may feel more comfortable if the face and hands are washed, hair brushed and teeth cleaned. If not contraindicated, a drink of the client’s choice should be offered. A warm drink in the evening may help to promote settling and sleep. Comfort needs for an infant in pain may include containment (swaddling) to increase feelings of security, and the pacifying effect of non-nutritive sucking |

| Gentle handling | When the client is being assisted to move, the nurse should ensure that any movements are made gently. Pain is usually increased on movement, so clients should be permitted and assisted to move at their own pace. As the client moves, the nurse should ensure that painful areas are supported. An incision can be supported during movement; the client or the nurse may place a hand over the incision to ‘splint’ it, or hugging a pillow may provide support on movement |

| Promote rest and sleep | Pain is very tiring, and fatigue increases reactions to pain; therefore the nurse should ensure that the client receives adequate and effective rest and sleep. Measures should be implemented during the day, as well as during the night, to facilitate rest; for example, the blinds may be drawn, and all care planned so that repeated interruptions and visits to the client are avoided. Relaxation reduces anxiety, can enhance the effect of pain relief and facilitates sleep. The client can be taught and encouraged to practise one of several relaxation techniques, as described earlier. If appropriate, and with client consent, gentle massaging of the neck and back may relieve tension and facilitate relaxation |

| Check dressings and splints | Any dressing, bandage or splint should be checked at regular intervals and, within medical orders, changed or adjusted if necessary. A poorly positioned dressing can irritate a wound, a bandage may be too tight or an inappropriately applied or positioned splint may cause pressure and pain |

| Adapt the environment | The nurse should consider the client’s immediate surroundings and adapt them according to individual needs. While some clients experiencing pain may prefer to rest in a darkened room, others may prefer that their room is bright and cheerful. A client may choose to attempt to distract themselves from their pain by watching television or listening to music, or may prefer to lie quietly. The presence of fresh fowers in the room may be a source of pleasure or irritation, and some clients may find it comforting if there are appropriate paintings on the wall. The nurse should ensure adequate privacy and appropriate ventilation and heating, while adapting the environment to meet individual needs |

| Implement prescribed therapy | The nurse may be responsible for being with the client during therapy, or may be involved in its implementation. Whenever therapy is prescribed, the nurse should implement measures to promote the client’s comfort and safety. The nurse should also monitor the client to assess the effcacy of prescribed therapy, and report and document all observations |

Non-pharmacological therapy

Pain management and control may be achieved by a variety of supportive measures other than medication. Non-drug approaches to pain management may include the use of heat or cold, massage and psychological methods.

Application of heat or cold

Heat applied to the skin causes dilation of the local blood vessels and, as a result, may improve the blood supply to an area, relax muscles and relieve spasm, promote healing and relieve pain. Cold applications may also be used to relieve swelling and pain. Cold has a numbing effect that helps to reduce pain in a body part.

Massage

Massage involves the manipulation of soft tissue and can increase circulation, reduce muscle tension, relax the individual and relieve pain. Cutaneous stimulation often acts to alter the client’s conscious awareness of pain. Aromatherapy and massage using essential oils may also be of benefit in some situations. Soothing touch and gentle rocking motion to promote contact, warmth and closeness may help to relax an infant in pain.

Psychological methods

Various techniques may be used to promote general relaxation of the client, and therefore reduce anxiety and relieve pain. Music and art may be used as a sensory distraction or as a soothing method of reducing stress. Other methods of distraction may be helpful to lessen the individual’s awareness of painful stimuli, such as encouragement of concentration on slow, deep, rhythmic breathing exercises, or even guided imagery, singing, praying or tapping. Several other methods of non-pharmacological pain management may be prescribed or undertaken. While it is not the role of the nurse to implement these, they may form part of the overall treatment plan, so an awareness of them is required.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture, which is a form of traditional Chinese medicine, involves the insertion of fine needles into the skin at selected points on the body. It may be used to manage both acute and chronic pain, and there are several theories about how it relieves pain. Some authorities believe that acupuncture achieves analgesia by stimulating the release of endorphins, while others believe that it stimulates the large diameter nerve fibres that effectively close the gate and block pain impulses (gate control mechanism).

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

A specific technique of peripheral nerve stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), involves the application of electrodes to trigger points on the skin (Fig 31.8). The electrodes are activated by a battery-powered device to produce a tingling or vibrating sensation in the painful area. The impulses block the transmission of pain impulses to the brain. TENS may be indicated for many people, especially those with joint or bone pain. It is normally well tolerated, although skin irritation is sometimes experienced. It should not be used for clients with cardiac pacemakers, as it can interfere with pacemaker function.

Hypnosis

Hypnotic analgesia may be achieved when a person enters a state of self-induced relaxation and concentration. During hypnosis, cognitive thinking is bypassed, allowing the individual to become more susceptible to suggestion. The individual enters a passive trance-like state, which is induced by a trained hypnotist, who may use the repetition of words and gestures. Susceptibility to hypnosis varies from person to person.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is a method that assists a person to become aware of, and subsequently to control, certain autonomic physiological responses, such as blood pressure, muscle tension and heart rate. Through concentration, and with the aid of instruments, the individual can learn to control and modify these processes, which are normally involuntary. The technique of biofeedback is more effective when accompanied by other relaxation techniques.

Placebo therapy

Placebo therapy involves the administration of inactive substances (such as lactose pills or sterile water), and may be effective for certain people in certain situations. It is thought that placebos relieve pain or other symptoms by causing the body to release endorphins, combined with an expectation that the treatment will be effective. The use of placebos involves a degree of recipient deception and poses many ethical and moral problems. Its use in mainstream pain management should generally be limited.

Pain clinics

People who experience chronic pain may be helped by attending a multidisciplinary pain clinic. Pain clinics commonly attempt to reduce use of pain medication, help clients resume normal activities and restore a positive self-image. Management includes a thorough physical and psychological examination before a program is designed for the individual. Approaches to pain management in a pain clinic include psychological counselling, acupuncture, TENS or any of the other methods of pain relief. The individual is taught alternative ways of carrying out the activities of daily living so that associated pain is minimised.

Pharmacological therapy

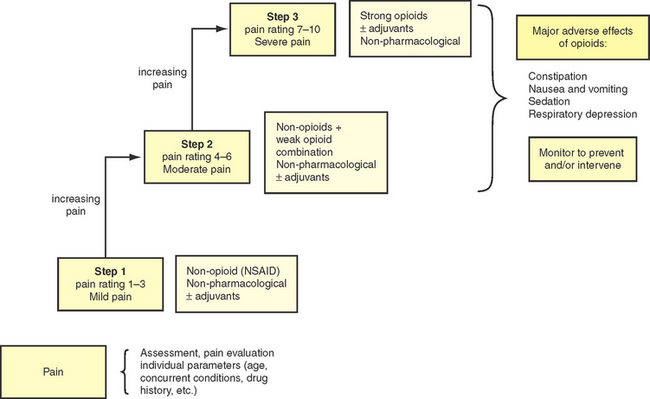

Medications prescribed by a medical officer to relieve pain may be either local or systemic, analgesic or co-analgesic. The nurse’s role in relation to medication administration involves assessment and monitoring of individual client responses to therapeutic treatments ordered. When medications have been prescribed, it may be within the nurse’s scope of practice to administer them. Figure 31.9 is a flow chart for pharmacological management of pain.

Figure 31.9 Flow chart for pharmacological management of pain

(Bryant & Knights 2011. Adapted from Salerno E & Willens JS (1996) Pain Management Handbook St Louis: Mosby)

Nerve block

Peripheral nerve transmission of pain can be interrupted temporarily by the injection of a local anaesthetic, or permanently by injecting a sclerosing agent into the nerve root area. As the latter method can result in destruction of tissue adjacent to the injected area, other pain-relieving methods are usually preferred, with this being an option in cases when other pain-relieving methods have been unsuccessful.

Counter-irritants

Counter-irritants, such as mentholated ointments and heat rubs, applied locally to the skin, can produce an inflammatory response, thereby relieving congestion in underlying tissues and reducing pain from the original source.

Radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy

The pain associated with malignant disease may be relieved by radiation, which shrinks a tumour that is actively causing compression in an area. Chemotherapy (also considered as pharmacological therapy) may sometimes control pain if the tumour is sensitive to the medications used.

Analgesic

Analgesic or pain-relieving medications may be mild, for example, non-narcotics such as acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) or paracetamol; or strong, for example, narcotics such as morphine or pethidine. Analgesics may be administered via a number of routes, including orally, by injection or infusion (intramuscularly, subcutaneously, intravenously or into the epidural space), or in some instances they may be applied topically (via creams or patches onto the skin). The type, dosage and route of analgesic medications given will be prescribed by the medical officer according to the client’s needs. Good pain control, especially in postoperative and chronic pain situations, is achieved by administering appropriate amounts of the most effective medication at regular intervals, thus avoiding the experience of peaks and troughs of pain. In some cases analgesia is ordered on a ‘prn’ (as required) basis, which may be appropriate for intermittent episodes of pain. Clinical Interest Box 31.5 provides a caution related to pain and the older adult.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 31.5 Pain and the older adult

Because of the normal changes of ageing, the older adult may respond differently to analgesics than a younger client. The older adult should be monitored closely for side effects and toxicity.

Analgesics are frequently given intravenously for severe pain, either as a bolus dose (a concentrated dose given in a short period of time) or, preferably, as an infusion, which has the advantage of avoiding repeated injections and establishes a constant blood level of analgesic drug, thus avoiding considerable pain between doses.

Clinical Scenario Box 31.1

Mrs Jones is 65 and, up until admission to hospital, has lived alone. She has had rheumatoid arthritis for the past 25 years, resulting in severely deformed hands. She is unable to walk without assistance and is no longer managing at home, despite full community services. Chronic pain is a major issue for her. Mrs Jones states that ‘the pain is there most of the time but gets worse when I move suddenly’.

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is another method using intravenous opioids and a programmable pump. A dose of drug is delivered each time the client pushes a button, within limitations set by the doctor. This allows the client to choose how often and when to receive the medication, and often enables them to establish a greater sense of control over pain management.

Epidural analgesia is an alternative method of pain control that uses a fine catheter inserted into the epidural space of the spine, again connected to a programmable pump. This method of pain relief is effective in controlling pain while allowing the client to remain alert. It is frequently used in obstetrics, postoperative clients and sometimes in clients with cancer. The primary responsibilities for caring for clients with either narcotic or epidural infusions lie with the registered nurse (RN). However, response to medications and evaluation of pain control measures are within the scope of practice of all nurses. Clinical Interest Box 31.6 outlines nursing measures for a client with an epidural infusion.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 31.6 Nursing care for clients with epidural infusions

| Goal | Actions |

|---|---|

| Prevent catheter displacement | Secure catheter (if not connected to implanted reservoir) carefully to outside skin |

| Maintain catheter function | |

| Prevent infection |

Use strict aseptic technique when caring for catheter (see Ch 29) |

| Monitor for respiratory depression | |

| Prevent undesirable complications | |

| Maintain urinary and bowel function |

Co-analgesic medications, while not true analgesics in the pharmacological sense, act to augment pain relief, either alone or in combination with analgesics. Examples of medications that may be used as co-analgesics are corticosteroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, both of which may act to decrease inflammation and oedema. The use of anti-anxiety drugs or drugs producing muscle relaxation may also be incorporated into a treatment plan. Sometimes a dose of co-analgesic medication together with an analgesic can produce greater pain relief than a higher dose of an analgesic alone. Table 31.6 outlines the nursing considerations for a client receiving specific analgesics and Table 31.7 outlines the actions of analgesics.

Table 31.6 Nursing considerations for a client receiving analgesics

| Medication | Nursing considerations |

|---|---|

| Salicylates | |

| Paracetamol | Nurses should make sure the dosage limits are maintained as paracetamol can cause liver toxicity. Care should be taken not to overdose as there is a variety of pharmaceutical preparations which can contain paracetamol such as Panadeine forte and Di-Gesic |

| NSAIDs | |

| Morphine-related products |

Adapted from Bryant & Knights 2011

Summary

Pain, which is often a protective signal of actual or impending tissue damage, is both an unpleasant physical sensation and an emotional experience. Each episode of pain is unique and subjective and it is important for the nurse to appreciate that ‘pain is what the client says it is’. Pain may be mild or severe, acute or chronic, physical or psychological.

Pain receptors transmit impulses along nerve fibres to the brain, where the impulses are perceived and interpreted. The body has some internal mechanisms that may be activated to help control pain and its perception, such as the gate control mechanism and the endorphin system.

The perception of pain varies with the individual; therefore, some people will experience pain much sooner and more intensely than others. Many factors influence an individual’s reaction to pain, including age, gender, culture, and emotional state, history of pain, self-image, the time of day and the environment. Although each individual’s behavioural reaction to pain is different, the physiological responses to acute pain are the same.

The nurse has a responsibility to assess a client’s pain in terms of site, time it occurs, duration, precipitating factors, type, intensity, associated signs and symptoms, body posture, vital signs and emotional manifestations.

The management of pain includes non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapy, and depends on each client’s individual needs. The nurse has a responsibility to eliminate or reduce painful stimuli and to plan and implement supportive nursing measures to help alleviate pain or to assist the client to manage their pain.

1. Discuss the rationale/benefits for use of non-pharmacological pain management strategies for:

2. Discuss the rationale for ensuring that pain assessment is undertaken in a nonjudgmental manner.

3. It has been observed that pain in certain groups, especially children and the elderly, is not always well managed, and that these groups may be among the most under-treated for pain. Why do you think that this may occur? What can the nurse do to improve this situation?

1. What is the purpose of pain?

2. Explain why rubbing/massage can relieve pain.

3. Explain physiologically why clients can become aggressive when they are experiencing pain.

4. Is pain a disease or a symptom of a disease?

5. What is the name given to pain from body parts that have been removed?

6. If clients experience psychogenic pain should we dismiss that as attention seeking?

7. What would be the general psychosocial impact of chronic pain on a middle-aged client?

8. How do age, culture or background and gender affect the client’s perception of pain?

9. What is the pain threshold?

10. How different would be the perception of pain in a client who already suffers from chronic pain?

11. What is the appropriate assessment tool that could be used to assess pain in children?

12. What would be the appropriate assessment tool to use for adult clients who do not speak English?

13. What is the appropriate tool to use to assess pain in a client with dementia?

References and Recommended Reading

Berman A, Snyder S, Kozier B, et al. Kozier and Erb’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 2nd edn. Pearson Australia, Frenchs Forest, NSW, 2012.

Brown D, Edwards H. Lewis’s Medical–Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems, 3rd edn. Sydney: Mosby Elsevier, 2012.

Bryant B, Knights K. Pharmacology for Health Professionals. Sydney: Elsevier, 2011.

Clayton BD, Stock YN, Harroun RD. Basic Pharmacology for Nurses. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2007.

Craft J, Gordon C, Tiziani A. Understanding Pathophysiology. Sydney: Elsevier, 2011.

Crisp J, Taylor C. Potter and Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 2nd edn., Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

deWit SC. Fundamental Concepts and Skills for Nursing, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Elsevier, 2009.

Heath HBM. Potter and Perry’s Foundations in Nursing Theory and Practice. London: Mosby, 1995.

Helmrich S, Yates P, Nash R, et al. Factors influencing nurse’s decisions to use non-pharmacological therapies to manage client’s pain. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;19(1):29–35.

Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, et al. The Face Pain Scale—revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93(2):173–183. Online. Available: www.painsourcebook.ca

International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Derived from Bonica JJ. The need of a taxonomy. Pain. 1979;6(3):247–248.

International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Task Force on Taxonomy Changes in pain terminology list. Online. Available: www.iasp-pain.org/Content/NavigationMenu/GeneralResourceLinks/PainDefinitions/default.htm, 2011.

Karch M. Focus on Nursing Pharmacology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

Lewis S, Heitkemper M, Dirksen S. Medical–Surgical Nursing, 7th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2008.

Marieb E. Human Anatomy and Physiology, 6th edn. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings, 2010.

Max EE. Complementary Therapies for Pain Management: an Evidence-based Approach. Boston, MA: Elsevier/Mosby, 2007.

McCaffery M, Pasero C. Pain Clinical Manual, 2nd edn. Mosby: St Louis, 1999.

McClean W, Higginbotham N. Prevalence of pain among nursing home residents in rural NSW. Medical Journal of Australia. 2002;177(1):17–20.

Melzack R, Casey KL. Sensory, motivational, and central control determinants of pain: A new conceptual model. In: Kenshalo D, ed. The Skin Senses. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1968:423–429.

Melzack R, Wall P. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science Journal (ISC). 1965;150:171–179.

National Pain Summit Initiative. National Pain Strategy: Pain Management for All Australians. Available: www.painaustralia.org.au/images/pain_australia/NPS/National%20Pain%20Strategy%202011.pdf, 2010.

Potter PA, Perry AG. Fundamentals of Nursing, 7th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2008.

Saunders C. Care of clients suffering from terminal illness at St. Joseph’s Hospice, Hackney, London. Nursing Mirror. 1964;14 February:vii–vix.

Waldman SD. Pain management. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Normative Guidelines on Pain Management. Available: www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/delphi_study_pain_guidelines.pdf, 2007.

Australian Pain Management Association, www.painmanagement.org.au/.

Chronic Pain Australia, www.chronicpainaustralia.org.au/.

International Association for the Study of Pain, www.iasp-pain.org//AM/Template.cfm?Section=Home.

Pain assessment tools, www.caresearch.com.au/caresearch/ClinicalPractice/Physical/Pain/AssessmentTools/tabid/748/Default.aspx.

Pain (Journal of the International Association for the Study of Pain). www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/506083/description#description.

The Australian Pain Society, www.apsoc.org.au/.