CHAPTER 35 Reproductive health

At the completion of this chapter and with some further reading, students should be able to:

• Describe the physiology of the male reproductive system

• Describe the physiology of the female reproductive system

• Consider alterations in health status that affect male and female reproductive systems

• Discuss factors that influence reproduction

• Identify factors that may affect sexual and reproductive health

• Discuss major clinical conditions which may affect sexual and reproductive health

• Identify diagnostic tests used to assess reproductive function

• Develop client management strategies for the management of sexual and reproductive disorders

• Identify nursing responsibilities in relation to child sexual abuse

• Understand the physical and social implications of sexually transmitted infections

This chapter looks at the important aspects of reproductive health as it affects individuals throughout the life span. It looks briefly at the normal anatomy and physiology of the male and female reproductive systems and discusses common alterations that impact on reproductive health. The chapter also looks at common diagnostic tests and examinations conducted to assess a client’s health status and the role of the nurse in identifying client needs and implementing a management plan.

After the birth of my son I was tired all the time and every time I looked at myself in the mirror I didn’t like the changes that the pregnancy had made to my body. The intimacy my husband and I had once shared seemed to have disappeared. I didn’t feel attractive and could not seem to be interested in having sex with my husband.

THE MALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

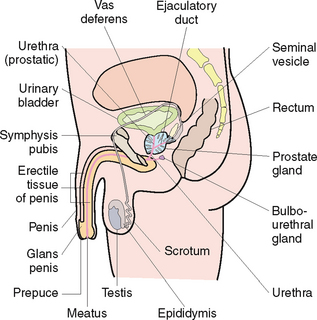

The male reproductive system (Fig 35.1) is comprised of the testis, epididymis, vas deferens, seminal vesicle, prostate gland, penis and urethra. A common conduit exists between the male reproductive system and the urinary system (the penis) which allows for normal passage of fluids of urine and semen into the exterior (Marieb & Hoehn 2010).

Spermatogenesis

Spermatogenesis, the production of sperm cells, is a process occurring in the testes. In early fetal life, the testes remain suspended in the abdomen and descend at birth or soon after, through the inguinal canal into the scrotum, suspended in place by the spermatic cords.

The testes are comprised of both exocrine and endocrine tissue. The exocrine portion is made up of seminiferous tubules which are responsible for the production of male sex cells (spermatozoa). The endocrine portion is responsible for the production of testosterone (Marieb & Hoehn 2010).

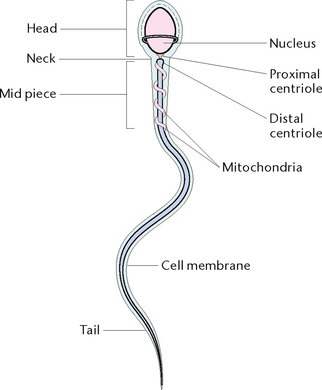

During puberty, cells in the testes called spermatogonia are acted upon by follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) which causes them to undergo cell division and produce sperm. The mature sperm consists of a head, which contains the genetic material of the cell; a mid-piece which comprises the mitochondria; and the tail which helps to propel the cell as it travels through the female reproductive tract (Fig 35.2).

Testosterone production

Testosterone production starts during puberty when it is responsible for the development of secondary sex characteristics such as:

• Pubic, axillary and facial hair

• Enlargement of the testicles, penis, scrotum and prostate gland

• Increase in larynx size resulting in deepening of the voice

• Increased production of sebum by the sebaceous glands (Marieb & Hoehn 2010).

Production of testosterone continues throughout the adult life of the male. Testosterone levels may decrease in older age and as a result of injury, disease, radiation and after surgeries such as a vasectomy.

DISORDERS OF THE MALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

A majority of the disorders affecting the male reproductive system are due to developmental or age-related causes. It is important to consider early corrective surgery for congenital or structural defects of the genitourinary tract if the physical and psychological impact of the defect is to be limited. The nursing interventions required during this time are mainly focused on providing support to both the child and the family during the preoperative and postoperative phase. This can be accomplished by providing adequate time to express concerns and fears as well as educating them about what to expect before and after the procedure. Often the use of appropriately targeted fact sheets is successful in providing this information.

Disorders affecting the male reproductive system are referred to as genitourinary disorders due to the shared anatomical structures of the urinary and reproductive systems. Conditions are usually characterised according to the type of alteration such as:

Disorders of the penis

Hypospadias and epispadias

Both hypospadias and epispadias are congenital defects affecting the urethral opening. In hypospadias the opening occurs on the underside or dorsal side of the penis and in epispadias, the urethral opening occurs on the ventral or upper surface of the penis. Surgery for both defects involves closure of the abnormal opening and extending the urethra to the normal location.

Phimosis and paraphimosis

Phimosis is characterised by narrowing of the prepuce orifice, which prevents the retraction due to an infection, an inflammation or a congenital lesion. The condition predisposes to infection and, if present in the adult, leads to difficulties during sexual intercourse. Where the condition is complicated by a forcible retraction of the prepuce over the glans penis inflammation of the prepuce collar can lead to swelling and constriction, a complication called paraphimosis. The treatment is circumcision.

Balanitis

Balanitis is a common condition characterised by inflammation of the glans penis which can occur at any age. The condition is more common in non-circumcised males who do not wash the whole penis, including retracting the foreskin. It can also develop as a result of an allergic response to chemicals such as latex and soaps or be an indicator of diabetes. While the condition can cause discomfort it is easily managed by finding and treating the cause.

Cancer of the penis

While penile cancer in Australia is rare, with the annual incidence of penile cancer found to be 1 in 250 000 of the population (AIHW & AACR 2007), it is considered to be an ‘emerging problem’ (Micali et al 2006). Research suggests that there is a higher incidence of penile cancer in non-circumcised males and this has led to the use of prophylactic circumcision in reducing the incidence (Micali et al 2006).

Penile cancer usually presents on the skin surface as a painless wart-type growth or ulcer. If left untreated the cancer will infiltrate tissues and cause urinary symptoms. Diagnosis of penile cancer involves biopsy of the lesion to confirm the diagnosis, chest x-ray, CT scan and lymph node biopsy to check for metastases. After confirmation of the diagnosis, management involves surgery and a combination therapy of internal and external radiation and chemotherapy. Surgical procedures can range from circumcision, laser or cryotherapy treatment to partial or total amputation of the penis.

Nursing management of the client before and after diagnosis is based on providing emotional support and ensuring counselling is readily available. Education should be offered to manage the physical and psychological impact on the client related to loss of sexual function and the cosmetic impact of a penile amputation.

Erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction is usually characterised as the inability to achieve and maintain an erection sufficient to permit satisfactory sexual intercourse. It is a common condition with an increased incidence in males as they get older. Causes may be due to psychological, neurological, hormonal, arterial or cavernosal impairment or from a combination of these factors (Table 35.1). The condition can be classified as psychogenic, organic or mixed psychogenic and organic. Psychogenic factors may include performance anxiety, lack of arousability, relationship difficulties or mental health disorders such as depression and schizophrenia.

Table 35.1 Causes of erectile dysfunction

| Cause | Presentation |

|---|---|

| Psychosocial problems | |

| Nerve function interference | |

| Reduced blood fow | Atherosclerosis |

| Medication, alcohol and other drugs’ interference | |

| Metabolic problems interfering with blood vessel function | |

| Urological problems |

Adapted from Factsheet: Causes of erectile dysfunction (impotence), Associate Professor Doug Lording, Andrology Australia, 2010

Sexual dysfunction is essentially not curable; however, treating the underlying cause can allow many males to manage the condition. The three main types of treatment include:

Priapism

This condition is characterised by a persistent and often non-pleasurable erection which may be due to an obstruction of a vein in the penis, or may be a complication of diseases such as sickle cell disease, leukaemia or use of some anaesthetic agents such as papaveretum. Excessive use of drugs used to treat erectile dysfunctions may also lead to priapism which is not able to be resolved through usual methods. A sustained erection leads to a buildup of toxins in the blood often called ‘black blood’ which will lead to anoxia and necrosis of tissue. The blood must be aspirated from the blood vessels in the penis in order for the erection to be resolved.

Clinical Scenario Box 35.1

Leo is an Italian gentleman who has been married for 28 years and experienced a healthy sexual relationship with his wife for the duration of that time. Not long after he turned 52 years old Leo had a mild heart attack which resolved itself within a couple of weeks; however, since the heart attack he has found it takes longer to establish an erection and maintain it long enough to return to normal sexual relations with his wife.

Conditions affecting the testes

Cryptorchidism

Cryptorchidism is a condition occurring more commonly in premature males where one or both of the testes fail to descend into the scrotum at birth. Approximately 5% of boys are born with undescended testicles, most commonly premature babies or those with low birth weight (Andrology Australia 2012). The condition is diagnosed by the absence, on palpation, of one or both of the testes in the scrotum. There is believed to be a link between a diagnosis of cryptorchidism and other health conditions such as hernias, testicular cancer and infertility in later life. The condition may be treated with hormone injections or surgery. Surgical placement of the testes in the scrotum (orchiopexy) is recommended before the second year of age to preserve sperm-forming cells that require a lower temperature than that of the abdomen. If the condition is not treated before puberty there is a risk of atrophy and sterility. The affected testis tends to be smaller and contain more fibrous tissue than the unaffected one.

Carcinoma of the testes

Cancer of the testes is one of the rare forms of cancer with an incidence of approximately 6.8 in every 100 000 men (AIHW 2008). In 2007, Cancer Council Australia reported that 698 men were diagnosed with cancer of the testes; half were less than 33 years old. There has been some research to suggest that the wearing of tight clothing may contribute to testicular cancer. The generally accepted factors related to the cause of testicular tumours (Table 35.2) include:

Table 35.2 Types of testicular tumours

| Germ cell origin (approx. 94%) | Stromal origin (approx. 6%) |

|---|---|

| Choriocarcinoma | Leydig cell tumour |

| Embryonal carcinoma | Sertoli cell tumour |

| Teratoma | Other |

| Seminoma | |

| Mixed tumours | |

| Other |

Early diagnosis and improved treatment modalities such as chemotherapy have contributed to improved outcomes for men diagnosed with the condition; this can be seen in a 5-year survival rate of 96.8% for all age groups under 60 years (AIHW 2008). An early stage indicator is the presence of a smooth painless lump in the scrotum or a dull ache located in the testes or lower abdomen. Other metastatic symptoms include bowel or urinary obstruction and abdominal pain.

If a lump is detected in the testes, the male who seeks medical advice will have the diagnosis confirmed with an initial physical examination, ultrasound of the scrotum and collection of blood for presence of blood serum markers. Elevated levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) will be detected in testicular cancer. Ultrasonography differentiates between a solid and a cystic lesion. Tests to detect potential metastases include chest x-ray and CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis.

Treatment for testicular cancer is dependent on the type and stage of the cancer. Surgical removal of one or both testicles (orchidectomy) is usually performed for all cases of testicular cancer. The testis is then sent to pathology for confirmation of the type and stage of the cancer. Following surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy usually follow surgery to kill any remaining cancer cells which may be located in other parts of the body.

Treatment often leads to infertility, which is a major consideration in the management of the male in the pre-treatment phase. For the male who may still want children, possible sperm banking should be considered. The male should also be reassured that the condition should not affect their virility and should not affect their ability to achieve an erection. The client may be referred to support services outside the hospital and should be educated in testicular self-examination. It is recommended that he carry out periodic examinations, as there is an increased risk of a second tumour occurring. It is important to reassure the client that removal of one testis does not necessarily lead to a loss of sexual function and there are options, both medical and surgical, available to manage cosmetic abnormalities.

Torsion of testis

Torsion of testis is a condition in which the testis becomes twisted around itself. It is more commonly seen in young athletic males after violent movement or trauma. The twisting results in obstruction of venous blood flow which may lead to infarction and, if left untreated, to necrosis and total lack of function.

Hydrocoele

Hydrocoele is a painless collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis of the testis from defective or inadequate reabsorption of fluid normally produced within the testis. The condition is fairly common in male infants where it is the most common cause of testicular swelling. In infants the accumulation of fluid is due to unhindered drainage from the abdomen, whereas in adult males it may be associated with infections, trauma or tumours. The individual may experience a feeling of heaviness or pain associated with increased scrotal size and may feel embarrassed because of the appearance of the scrotum.

Ultrasound and transillumination are diagnostic tests used to differentiate between hydrocoele and other causes such as tumours. If a hydrocoele is present, transillumination will allow transmission of light through the scrotum. Treatment is not usually required unless there is compromised testicular circulation. However, a scrotal support can be worn to increase comfort.

Varicocoele

A varicocoele more commonly affects the left testis and occurs when the valves within the veins prevent blood from draining fully from the testis. This leads to pooling and swelling of the vein above the testis. Varicocoele is often described as a varicose vein of the spermatic cord. The client will usually present describing their symptoms as a ‘pulling’ sensation, dull ache in the scrotum, pain and scrotal swelling. On palpation the scrotum feels like a ‘bag of worms’. If left untreated, the condition can lead to a reduced sperm count, atrophy of the testis and can cause infertility.

Treatment of a varicocoele can be either by surgery—the affected vein is ligated—or an embolisation which can be performed under local anaesthetic. Post procedure the male may require mild analgesics for discomfort and the intermittent use of ice packs to reduce swelling. Wearing a scrotal support can also reduce oedema and discomfort. Strenuous activity should be avoided until after review by the surgeon.

Disorders of the prostate gland

Prostatitis

Prostatitis is an inflammatory or infective condition of the prostate gland which may be bacterial (usually Escherichia coli). It generally develops in association with an obstruction in the urinary tract in elderly males with prostatic hyperplasia, a urinary tract infection (UTI) or a sexually transmitted infection. Clinical manifestations include urinary symptoms of urgency, frequency, nocturia and dysuria. Bacterial prostatitis is characterised by sudden chills and a moderate to high fever. Pain in the perineum, rectum and lower back during ejaculation are other symptoms. Diagnosis is based upon urine, urethral and prostatic fluid cultures. Digital rectal examination frequently reveals a tender swollen prostate.

Treatment of acute bacterial prostatitis is usually with an appropriate antibiotic and analgesic or, where an abscess has formed, the surgical drainage of the pus. Oral antispasmodic agents may provide relief from urinary frequency and urgency. The nurse can support the client with comfort measures such as salt baths to relax the muscles of the pelvic floor. Stool softeners can reduce pressure on the prostate gland and are given as prescribed. Fluids should be encouraged to mechanically flush out the urinary tract. Repeated episodes of prostatitis may lead to scarring and thickening of the prostate.

Prostatic hyperplasia

Prostatic hyperplasia is a widespread condition which increases with age, often occurring after the age of 40 years. Approximately one in seven men between 40 and 49 years are diagnosed with prostate problems and this increases to about one in four men after 70 years of age (Holden et al 2005). In a majority of males the condition is benign, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

The normal ageing process usually causes the prostate gland to increase in weight and bulk (hyperplasia). The hyperplasia can compress the urethra laterally at the neck of the bladder which can impede urinary flow. Symptoms of BPH may be classified as either noticeable or obstructive (Table 35.3). Noticeable changes begin as the prostate becomes progressively more enlarged and include hesitancy, a weak stream, straining to urinate, dribbling after urination, urinary retention and overflow of paradoxical incontinence. Obstructive symptoms may include urgency, frequency and nocturia.

Table 35.3 Symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)

| Irritative symptoms | Obstructive symptoms |

|---|---|

| Hesitancy | Urgency |

| Weak and poorly directed stream of urine | Frequency |

| Straining to urinate | Nocturia |

| Dribbling after urination after voiding or irregular stream | |

| Urinary retention | |

| Overfow or paradoxical incontinence |

Adapted from Factsheet: Prostate Enlargement (BPH), Associate Professor Mark Frydenberg, Andrology Australia, 2010

The cause of BPH is not well known. There has been some research that suggests there is a genetic or familial link. There has also been research which links old age and testosterone to the development of BPH as it is known that the condition occurs in the presence of testosterone.

Diagnosis of the condition is based on the symptoms, digital examination which detects changes in the surface of the prostate and blood tests such as a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test which measures the level of PSA, a glycoprotein produced by the prostate gland. In the presence of BPH, the PSA levels may be raised. Biopsy of the prostate may also be performed. Biopsies are collected during a transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) which may also be used when there is a strong suspicion of prostate cancer.

Treatment options for BPH range from:

No treatment may in many cases be the best option where the symptoms are mild and involves close monitoring of the condition. Drug therapy involves the use of medications to relax the muscles in the prostate gland, bladder neck and urethra (alpha blockers) or the use of medications to block the release of testosterone to help shrink the size of the prostate (alpha reductase inhibitors). Some men may also try natural therapies or surgery if the condition is severe.

The type of surgery will depend on the size of the prostate, location of the enlargement, whether surgery on the bladder is also needed and the client’s age and physical condition. The most common surgical procedure is transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), used in more than 90% of cases. Surgery relieves symptoms quickly, typically doubling the urinary flow within weeks. A fibreoptic scope is passed through the urethra to the prostate. Using either a tiny blade or an electric loop, the surgeon pares away the lining of the urethra and bits of excess prostate tissue to expand the passageway.

After a TURP, the client usually stays in hospital until the prostatic bed stops bleeding and they are able to void normally with minimal haematuria, which may be up to 48 hours. The client should be educated on the importance of remaining well-hydrated after removal of the urinary catheter to ensure they void regularly and do not develop retention due to a micro-clot in the urethral bed. Possible risks of surgery should also be provided to the client prior to surgery, which include:

• Heavy bleeding, wound infection and thrombosis formation

• Urinary tract infections (Andrology Australia 2010d).

Newer approaches to management of the condition which usually have a shorter stay in hospital and recovery include:

• High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU)

• Electrovaporisation (TVP) (Andrology Australia 2010d).

Most of the newer treatment methods are based on destroying, vaporising or dissolving hyperplasia and can be done with little more than a local anaesthetic on an outpatient basis.

Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer occurs mainly in males over the age of 50 years, tends to grow slowly and may have metastasised before it is detected. Initially the man may be asymptomatic. When symptoms appear, they are often similar to those caused by BPH: difficulty urinating, a weak stream, a frequent urge to urinate, nocturia, painful or burning urination and haematuria. Because prostate cancer tends to metastasis to the bone, bone pain, particularly in the back, can be another symptom. The most common type of cancer in Australian men, excluding skin cancer, is prostate cancer, with over 19 000 Australian males diagnosed each year (AIHW 2011). Usually the younger the client the more aggressive the cancer.

Diagnostic tests include digital rectal examination, prostate specific antigen levels, biopsy of the prostate, renal function tests and TRUS. A TRUS involves the insertion of a probe into the rectum and collection of biopsies which are viewed in the laboratory and given a grading using the Gleason Score. Aggressive tumours will be rated between 8 and 10.

Treatment

Prostate cancer may be treated by radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy (palliative) or by open prostatectomy. Surgery for prostatic cancer is often done for palliative reasons because of the late onset of symptoms resulting in the condition being in the late stages on diagnosis and metastases often already being present. Radiotherapy may be performed to reduce the size of the tumour. Alternatively, hormonal therapy may be used in the short term, which also reduces the size and slows the rate of tumour development. It is usually only successful while the tumour relies on hormonal levels to sustain itself; after time it will become independent and growth becomes rapid again.

Prostatectomy

Open prostatectomy may involve either a radical or a partial procedure. A radical prostatectomy is used for clients who are in good health and less than 70 years, with a life expectancy greater than 10 years and with a tumour known to be confined to the prostate gland (MSAC 2006).

The procedure can be performed using either a perineal or retropubic approach. The retropubic approach involves an incision through the lower abdomen to remove the prostate and possibly the pelvic lymph nodes whereas the perineal approach requires an incision through the perineum. The retropubic approach is associated with a larger number of blood transfusions and longer operative times (Frazier et al 2005). By contrast with the perineal approach there is a reported higher level of impotence and incontinence compared to the retropubic approach.

Most prostatectomy procedures are performed using a laparoscopic approach which involves the use of a remotely assisted controller-subordinate system—the da Vinci® surgical system. This procedure is essentially robotic surgery which involves multiple, small incisions into the abdominal wall and the introduction of instruments required to perform the surgery.

Nursing management involves supporting the client prior to surgery and maintenance of hydration and fluid status. An indwelling or suprapubic catheter may be necessary to establish and monitor urinary output. Bowel preparation may include drinking 2–3 L of a cathartic and administration of an evacuant enema. Postoperatively the nurse should maintain bladder irrigation and drainage, and monitor for clots and haemorrhage. Postprocedural and discharge education needs to take physical and psychosocial factors into consideration.

Discharge education

After a radical prostatectomy, an indwelling urinary catheter (IDC) may remain in situ for about 2 weeks, so education of the client should concentrate on care of the catheter including changing or emptying the leg bag and the importance of maintaining a high fluid intake to reduce the risk of clot formation.

Systemic diseases and ageing

Sexual function declines with age even in healthy men. The period between sexual stimulation and erection increases, erections are less turgid and ejaculatory force and volume is less. Conditions such as diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure and cardiovascular disease are believed to be linked to erectile dysfunction.

A thorough medical, sexual and psychosocial assessment should be undertaken. Urinalysis, full blood count and fasting serum glucose, creatinine, cholesterol, triglycerides and testosterone are recommended laboratory tests. Treatment depends upon the cause. It can include a variety of drug therapies, which may be administered orally, transurethrally or by subcutaneous or intracavernous injection.

Surgical procedures

Vasectomy

A vasectomy is a surgical procedure commonly performed on males who have children and do not want to father any more. A study by Sneyd and colleagues (2001) identified the prevalence of vasectomy in New Zealand as 57% of men 40 to 49 years and 15% of those 70 to 74 years. It is estimated that in Australia approximately 300 000 males will undergo this procedure every year which in a majority of cases is permanent. An estimated 3% will, however, undergo reversal surgery.

The procedure can be performed under general anaesthesia; however, a majority will be performed under local anaesthesia in a fertility clinic, day procedure unit or a general practice. The procedure involves a small incision being made either side of the scrotum and the vas deferens being bought to the surface. Either a ligature is placed around the vas deferens to seal off the passage of sperm past the blockage or, in the majority of cases, a small segment of the vas deferens is removed and the ends diathermied to seal the ends.

There is usually no alteration to the male’s ability to maintain a sexual relationship or the effectiveness of their erection. Ejaculation is still possible; however, there should be no sperm in the fluid as it will have been prevented from travelling past the epididymis where it is reabsorbed into the body.

Postoperatively the male may have minor discomfort and swelling related to the procedure which settles after 24 to 48 hours. The wound heals quickly without the need for specialised care. The client should be advised to abstain from unprotected sex until a clear seminal fluid analysis has been completed (between 6 and 12 weeks) which shows no evidence of sperm in the ejaculatory fluid. In a small number of cases the procedure may be unsuccessful and the client may need to undertake further surgery.

Assessment and diagnostic tests

The client may be anxious or embarrassed about the physical examination and discussion of his sexual history. A calm insightful approach is required, as is preservation of the client’s individuality and dignity throughout. Cultural and religious customs such as circumcision should be considered.

Examination of external genitalia

A complete history of the client should be collected prior to any procedure. For the male who presents with a condition affecting their reproductive system, this history should concentrate on the presence of urinary problems and symptoms which suggest alteration in normal sexual function. It may be necessary to conduct a physical assessment of the male genitalia and inguinal canal which may detect or confirm the presence of penile discharge, tenderness, lesions, swelling, lumps or asymmetry.

Testicular examination

Testicular self-examination (TSE) should be performed on a regular basis. The testes are examined for size, shape, symmetry and texture. It is important that both testes are checked at the same time (see Clinical Interest Box 35.1).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 35.1 Client teaching—testicular self-examination

• It is often easier to perform this examination after a warm bath or shower when the skin of the scrotum is relaxed

• It is important to check both testes at the same time

• Use the palm of the hand and support the scrotum (Note: it is not unusual for one testis to be slightly larger than the other)

• It is important to be familiar with the feel of the texture and size of the testis so you are able to detect reportable changes

• Roll one testis gently between the thumb and fingers to feel for lumps or swellings

• Repeat with the other testis. The surface of the testis should feel smooth and firm

• Use the thumb and fingers to feel along the epididymis for any swelling

• Even if you have had testicular cancer or are being treated, it is still important to perform a testicular self-examination as there is about a 5% chance that a testicular cancer may develop in the other testis

(Adapted from Factsheet: Testicular Self-examination, Professor Mark Frydenberg, Andrology Australia, 2012)

Digital rectal examination

Digital examination of the prostate involves the insertion of a gloved finger inside the rectum to palpate the prostate. The examination detects the size, shape and firmness of the prostate through the wall of the rectum.

Prostate-specific antigen test

This test measures the level of PSA which is a protein produced by cells of the prostate gland. A high PSA is suggestive of a condition affecting the prostate but may not necessarily mean the client has prostatic cancer. Approximately one in three men with a PSA between 4 and 10 ng/mL could have prostate cancer (Andrology Australia 2005a). (See Clinical Interest Box 35.2.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 35.2 PSA testing

A five-year study funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council stated in a report released in 2010 that the ‘PSA test was not cost-effective’ and the number of false-positive results returned from the test subjected many men to ‘expensive and unpleasant follow-up diagnostic procedures’.

The president of the Urological Society in Australia stated ‘we know that prostate cancer is a serious problem—there are 20 000 new diagnoses of prostate cancer every year, and over 3300 men will die this year (2010) from prostate cancer’… ‘Screening can reduce prostate cancer by between 31 and 44 per cent.’

Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)

In transrectal ultrasound a small probe that emits and picks up high-frequency sound waves is inserted into the rectum. The reflected waves are detected and a visual image displayed on a monitor. The test does not provide sufficient information to make it a good screening tool by itself but is useful as a follow-up to a suspicious digital rectal examination or PSA test. It is also used to guide biopsies in sampling abnormal areas of the prostate, to estimate the volume of the prostate for calculating PSA density and to situate radiotherapy implants (Andrology Australia 2005a).

Biopsy

Biopsies of the prostate gland are usually performed in combination with the transrectal ultrasound to detect abnormal cells. A needle is inserted through the perineal skin and a quantity of prostate tissue is aspirated. Biopsy specimens of tissue are sent for cytological examination.

Urethral culture

A small swab is inserted 3–5 cm into the urethra to obtain a specimen for microbiological analysis. A preliminary result of findings for this test will usually be available within 24 hours of collection, with a more definitive result after 48 hours.

Semen analysis

A sample of semen is obtained and the sperm examined for motility, morphology, quantity and quality. The test requires the client to provide a fresh sample of ejaculatory fluid which is sent for analysis as soon as possible after collection. Results of semen analysis are usually available within 24 hours.

NURSING INTERVENTIONS IN MALE REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

The man with a condition affecting his reproductive system would be expected to experience concerns about sexual function, fertility, urinary problems and the effects of the condition they are diagnosed with. The nurse should be aware of these concerns and provide supportive services such as counselling in their approach to care, provision of supportive services and the promotion of a healthy lifestyle.

THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

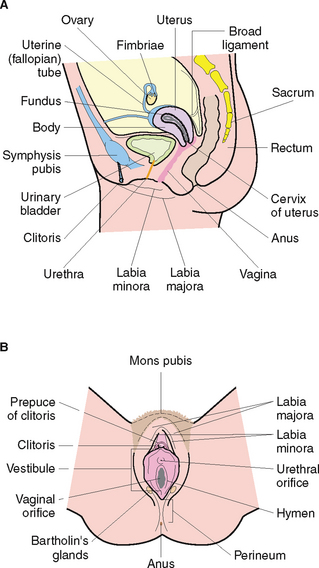

The female reproductive system (Fig 35.3) functions to secrete hormones, produce ova, receive sperm and allow for fertilisation, implantation, development and birth of the baby. The female reproductive system consists of essential and accessory organs. The essential organs, or gonads, are the ovaries. Accessory organs consist of a series of ducts, additional sex glands and external structures (Marieb & Hoehn 2010).

Oogenesis

The ovaries function to produce ova (oogenesis) and hormones. Production of ovarian hormones begins at puberty. Oestrogen influences the development of the female secondary sexual characteristics including changes in the breast, development of pubic and axillary hair, onset of menses and widening of the pelvis. Oestrogen is also responsible for preparing the uterus for the implantation of a fertilised ovum.

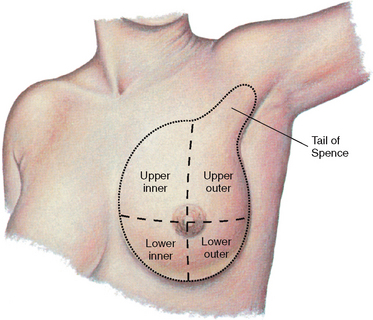

Mammary glands

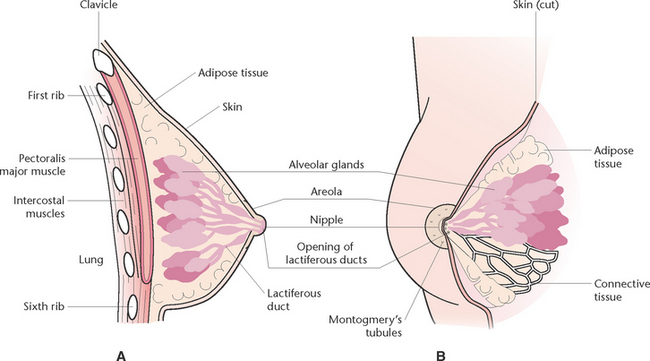

Mammary glands are accessory glands of the reproductive system. The breast is a complex structure composed of a glandular and ductal network, fat, connective tissue, fascia, blood vessels, nerves and lymphatic vessels (Fig 35.4). Each breast contains 15–20 lobes that radiate around the nipple and are separated from each other by adipose tissue. Within the lobes are lobules that contain clusters of milk-producing cells called alveoli. Lactiferous ducts drain the alveoli into openings in the nipple. Breast development at puberty is influenced by ovarian hormones (Marieb & Hoehn 2010).

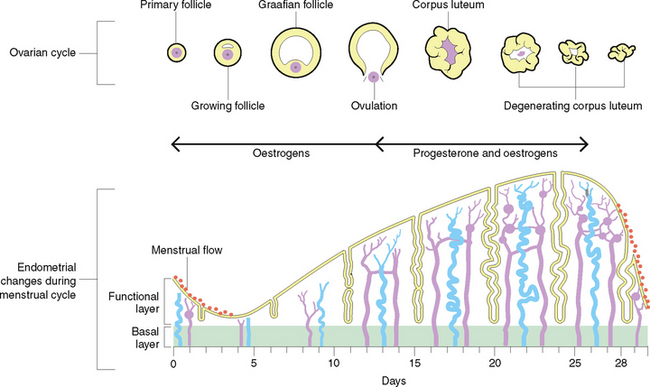

The menstrual cycle

The menstrual cycle consists of a series of cyclic changes occurring at regular intervals, involving the reproductive organs. The average menstrual cycle is about 28 days but may vary from 24 to 35 days (Fig 35.5).

DISORDERS OF THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

Common symptoms

The symptoms most commonly observed in a female with a disorder of the reproductive system include bleeding, pain, vaginal discharge, pruritus, urinary problems and breast changes.

Bleeding

Amenorrhoea is the absence of menstruation. It is normal before puberty, during pregnancy and after menopause. Secondary amenorrhoea generally results from annovulation due to hormonal dysfunction.

Excessive and/or prolonged bleeding (menorrhagia) is associated with erosive lesions, endometrial hyperplasia, bleeding disorders or neoplasms (tumours). Postmenopausal bleeding may result from the administration of oestrogen (hormone replacement therapy (HRT)), from an oestrogen-producing ovarian neoplasm, uterine hyperplasia or carcinoma or vaginitis. Metrorrhagia, or intermenstrual bleeding, can occur at the time of ovulation, or it may be due to factors such as hormonal imbalance or neoplasms.

Pain

Pain may occur as dysmenorrhoea (painful menstruation) which is the most commonly experienced type of pain in women. Pain may be described as intermittent, cramping lower abdominal pain, and it can radiate to the back, thighs and groin. Dysmenorrhoea can be secondary to endometriosis, uterine fibroids or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

Pain may occur in the lower back due to menstruation, infection, inflammation or neoplasm and may be due to conditions such as torsion of an ovarian cyst or a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. If blood from the ruptured fallopian tube tracks to the diaphragm and stimulates the phrenic nerve, shoulder-tip pain may be evident.

Sexual intercourse may result in pain (dyspareunia), which are the result of conditions such as vaginal or vulval infections, endometriosis, neoplasms or PID. Decreased vaginal lubrication may also result in dyspareunia.

Vaginal discharge

Normal vaginal discharge should be clear or white. An offensive odour or changes in the character or amount of discharge may be suggestive of an underlying problem of the vagina or cervix.

Pruritus

Pruritus is an irritating symptom suggestive of inflammation, vaginal infection or possibly contact dermatitis.

Vulval and vaginal changes

The adult vagina is generally very resistant to infections due to the presence of a characteristic normal flora which creates an environment which is unsuitable for the growth of most microorganisms. When the normal balance of the vagina’s pH is disturbed, which may occur with certain medications, diseases and debility, it becomes predisposed to infections.

Vulvovaginitis/vaginitis

Vulvovaginitis is inflammation of the vulva and vagina. Causes of vaginitis include infection, vaginal mucosal atrophy, vulval atrophy, chemical irritants and poor personal hygiene. Yeast infection results from the presence of Candida albicans in mucous membranes and on the skin. Under certain circumstances overgrowth and infection can occur. Predisposing factors include diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and the use of oral contraceptives. Clinical indicators include pruritus and a thick, white vaginal discharge. Haemophilus vaginitis is caused by the bacterium Haemophilus vaginalis. This type of vaginitis is generally mild, with less severe pruritus than occurs in other infections. Genital herpes and infections with Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis, Gardnerella vaginalis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae are sexually transmitted infections (STIs) that are sometimes characterised by vaginitis (Vardaxis 2010).

Candidiasis (thrush)

Candidiasis is caused by an overgrowth of a yeast-like fungal organism called Candida albicans. The condition is characterised by pruritus, vaginal and vulval redness, a thick, white or creamy vaginal discharge and discomfort and pain during sex.

Genital herpes

Genital herpes is an infection caused by the herpes simplex virus and is transmitted through vaginal, oral or anal sex. Genital herpes is characterised by flu-like symptoms and painful blisters in the genital area within 2–14 days of exposure. (See Clinical Scenario Box 35.2.)

Clinical Scenario Box 35.2

Susie is a 22-year-old who provides a history of discomfort and itchy labia, that began approximately 2 weeks ago, and which she thought was thrush and treated non-pharmacologically at home. When it did not settle after a couple of days she purchased an over-the-counter medication. When the itching did not seem to be improving, she decided to consult her doctor who performed an examination and discovered five small lesions on her labia the size of five cent pieces. Susie has recently become sexually active with a new partner but did have a one night stand 3 weeks ago.

Genital warts

Genital warts are caused by particular types of the human papillomavirus and transmitted through vaginal, oral and anal sex. The warts appear on the vulva, clitoris and cervix, inside the vagina and urethra and in or around the anus.

Cancer of the vulva

Cancer of the vulva is a relatively uncommon condition, with approximately 280 cases in Australia per year (National Centre of Gynaecological Cancers 2010). The condition tends to develop from premalignant hyperplasia, and is more common in women over 50 years of age. It is characterised by vulval pruritus, a history of chronic vulvitis and the presence of raised grey–white patches on the vulva.

Disorders of the internal reproductive organs

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is any acute, subacute, recurrent or chronic infection of the uterus and uterine tubes that can extend into the pelvic cavity. Causative organisms of PID include Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. Symptoms of PID may include pain, discharge and pyrexia. Treatment tends to be symptomatic with the use of antibiotics, analgesics and antipyrexics.

Nursing care of the woman with a PID includes education to ensure regular perineal hygiene is observed, regular changing of pads where vaginal discharge is present and counselling about the potential complications of PID which include chronic abdominal pain, ectopic pregnancy and infertility. The impact on fertility may be significant if the woman is planning to have children (see Clinical Scenario Box 35.3).

Clinical Scenario Box 35.3

A 17-year-old girl has been admitted to the ward complaining of lower abdominal pain which has been present for the past 10 days and is increasing. On admission she reveals that she went to a party with a boyfriend 2 weeks ago and engaged in sexual intercourse. She states that while they used a condom, they had initially used no protection. She describes a vaginal discharge which is heavy and has an odour. She has already conducted a home pregnancy test which was negative.

Disorders of the uterus

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a common condition found in approximately 10% to 30% of women between the ages of 20 and 40 years. It is characterised by the presence of functioning endometrium outside the lining of the uterus, usually confined to areas in the pelvic cavity. The cause is unknown, but research suggests that some endometrium is expelled from the uterus into the pelvic cavity at the time of menstruation.

The symptoms of endometriosis are dependent on the location and the extent of the tissue affected. In mild cases the condition may be asymptomatic or there may be only slight discomfort or pain during menstruation. In severe cases there may be dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, menorrhagia, dysuria, diarrhoea or constipation, abdominal distension, premenstrual tension and infertility. The use of the oral contraceptive pill (OCP) has been found to protect against the development of endometriosis. The OCP may also be used to manage the condition by altering the menstrual cycle through hormonal manipulation. The aim is to produce a pseudo-pregnancy, pseudo-menopause or persistent anovulation, thereby creating an environment in which the endometrium does not grow or is not maintained. The ectopic endometrial tissue will not be subject to the normal menstrual cycle stimulation and the pain associated with endometriosis will be diminished.

Surgical treatment is also widely used to treat endometriosis. The conservative option is removal of all obvious ectopic endometrial implants from the abdomen and pelvis. A laparotomy or laparoscopy is performed, with the latter approach having a lower cost and recovery time. Endometrial tissue is destroyed using a variety of techniques, including vaporisation or excision. Surgery to remove all endometrial tissue involves removal of the ovaries and sometimes the uterus. Treatment for endometriosis is aimed at the ectopic implants but the symptoms can be managed directly. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have proved to be of benefit as first-line treatment. Surgical intervention to interrupt neural pathways for pain conduction may be of benefit in selected cases. Doctors have also recommended that women with endometriosis should become pregnant as the altered hormone levels and not having a menstrual cycle for 9 months have in some cases been successful in reducing the symptoms.

Uterine prolapse

The uterus is kept in place by a number of muscles and ligaments which make up the pelvic floor. When these muscles and ligaments become stretched, damaged or weakened through sustained forces brought about by events such as pregnancy and straining, they no longer provide the support to prevent the uterus from falling into the vagina. The collapse can be either a complete collapse where it protrudes outside the body, or partial (Table 35.4).

Table 35.4 Stages of uterine prolapse

| Stage | Results |

|---|---|

| I | Descent of the uterus to any point in the vagina above level of the hymen |

| II | Descent of uterus to level of hymen |

| III | Descent of uterus beyond hymen |

| IV | Total eversion of procendentia |

Causes of a uterine prolapse can include:

• Chronic coughing, constipation and straining

• Spinal cord and other muscle atrophy conditions

• Race (Barsoon 2011).

Depending on the stage of prolapse, women will experience symptoms of the condition ranging from backache, a ‘dragging’ sensation and cervical erosion to bleeding and urinary difficulties. Stress incontinence is a common problem experienced by women and may lead to urinary tract infections. Where the posterior aspect of the urinary bladder protrudes into the uterus (cystocele), there may be a feeling of pelvic pressure and where the rectum herniates into the uterus (rectocele) there is often a feeling of rectal fullness, faecal urgency and incomplete defecation.

Management of the condition may be conservative or surgical. Where the condition is managed conservatively, the woman may be required to perform a series of pelvic floor exercises to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles. Exercises consist of regular tightening then relaxation of muscles surrounding the entrance of the vagina, urethra and anus. Each time the muscle is tightened it is held for 5–10 seconds and then relaxed. The exercise is repeated a number of times and the woman is encouraged to repeat the exercises several times a day. There are devices like balls which can be inserted into the vagina to ensure the exercises are being performed correctly.

Surgical management of uterine prolapse includes procedures such as a hysterectomy using either the vaginal or the abdominal approach and a procedure called a sacrohysterpexy which involves an abdominal incision and insertion of a mesh to reinforce and strengthen the abdominal muscles.

Disorders of the ovaries

Ovarian cysts

Ovarian cysts are extremely common, with a simple cyst accounting for approximately 80% of ovarian swellings. They are usually non-neoplastic with either single or multiple small cysts developing about 10 mm in diameter, although they have been known to grow to about 6–7 cm in diameter. They are filled with a clear fluid which is high in oestrogens. In many cases the cysts remain asymptomatic; however, if they rupture they can cause severe abdominal pain and bleeding. Generally the cysts resolve without the need for treatment but for a small number of women surgery may be required.

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common condition in women and is characterised by irregular menstrual cycles, excessive hair growth and obesity. As the name suggests, PCOS is the presence of multiple, large cysts in the ovary which may cause health complications if left untreated. The condition is believed to occur as a result of increased production of androgens (see Ch 34).

Tumours of the female reproductive system

Ovarian cancer

Tumours affecting the ovaries can vary in their size, diversity and occurrence (see Table 35.5). This is one of the more common of the cancers affecting women.

Table 35.5 Types of uterine cancer

| Type | Clinical behaviour |

|---|---|

| Ovarian | Most common type of uterine cancer. Accounts for 90% of cases |

| Borderline tumours | A group of epithelial tumours which are not as aggressive as other epithelial tumours. They are often referred to as ‘low malignancy potential’ (LMP) tumours. Prognosis is good regardless of when diagnosed |

| Germ cell tumours | Begins in cells that mature into eggs. Accounts for 5% of tumours and more commonly in women under 30 years |

| Sex cord-stromal cell tumours | Begins in ovarian cells that release female hormones. Accounts for 5% of cases and can affect women at any age |

Both germ cell and sex cord-stromal cell tumours respond well to treatment and are often curable. If only one ovary is affected and therefore removed there is a good chance the woman will still be able to have children.

Diagnosis of ovarian cancer is definitively made only after surgery during which biopsies and removal of a frozen section are performed to determine the presence of cancer cells. The woman may have a transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) and blood taken to detect the presence of the tumour marker CA125. It may be possible to detect irregularity on palpation of the abdomen or physical examination if the tumour is large. The use of a TVU, which involves the use of a probe inside the vagina to detect the presence of a tumour, and other imaging tests such as abdominal x-rays, CT scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are occasionally used.

Symptoms of ovarian cancer include:

• Increase in abdominal size or persistent abdominal bloating

• Urgency and frequency of urination

• Difficulty eating or feeling of fullness

• Unexplained weight loss or gain

• Indigestion and nausea (Ovarian Cancer Australia 2010).

Treatment for ovarian cancer may initially involve a laparotomy where biopsies are taken and sent for analysis to confirm diagnosis. On confirmation of diagnosis, the surgeon will remove the affected ovary. Where the tumour has spread to affect other structures, it may be necessary to perform a partial or total hysterectomy.

Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is one of the most common cancers in women and may be one of two types: squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma. Cervical cancer begins as a change in the epithelial covering of the cervix and, if not treated, eventually involves the epithelial layer. Invasive carcinoma extends beyond the surface, involves the body of the cervix and may spread via the lymphatic system to surrounding structures. Clinical signs of cervical cancer do not appear in the early stages. Later manifestations are ‘spotting’ between menstruation, postmenopausal bleeding, bleeding after sexual intercourse or a brown vaginal discharge (National Centre for Gynaecological Cancers 2010).

Since the introduction of the National Cervical Screening Program in 1991 (see Clinical Interest Box 35.3) when the number of new cases of cervical cancer was reported to be 1092, the number of new cases had dropped to 715 cases in 2006 (DoHA 2011).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 35.3 National HPV vaccination program

In April 2007, the Australian government commenced the National HPV Vaccination Program which is offered to girls aged between 12 and 13 years free on an ongoing basis. Initially the program also offered the vaccine free for girls and young women aged between 14 and 26 years.

Young women not in school and under 27 years were provided access to the vaccination through their GP or community immunisation clinics under the catch-up program which ended in December 2009.

The vaccine is given in a series of three injections, spread out over a six month period.

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is not as common as other forms of cancer. The benign form presents as fibroids which grow in the wall of the uterus of women in their forties. They are usually asymptomatic and as the woman enters menopause the fibroids tend to get smaller. If they cause heavy bleeding they may need to be surgically treated. Other presentations may be as endometriosis and endometrial hyperplasia.

The usual management for women who have malignant neoplasms (cancers) is surgical intervention with a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy to eliminate any remaining cancer cells. Management may also involve undergoing a hysterectomy.

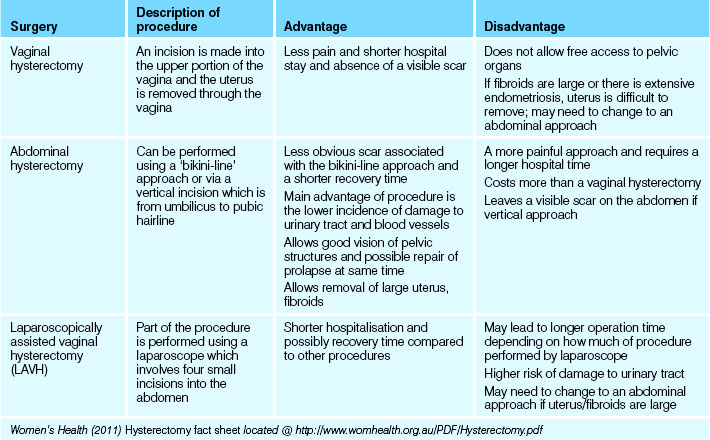

Hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus and may also involve the removal of other structures depending on the extent of infiltration or damage to reproductive organs. Prior to any woman undergoing a hysterectomy, it is important they are aware they will no longer menstruate or be able to conceive a child. For some this prospect may bring relief, while for others it may be distressing. A compassionate approach to nursing care is important.

The main four types of hysterectomy operations (see Table 35.6) performed in Australia are:

• Sub-total or partial hysterectomy: involves removal of fallopian tubes, upper two-thirds of uterus and preservation of cervix. Not commonly performed in Australia

• Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation: involves removal of fallopian tubes, uterus and cervix and preservation of the ovaries. Procedure is often referred to as a ‘total hysterectomy’

• Hysterectomy with oopherectomy: involves removal of fallopian tubes, uterus and cervix and either one or both ovaries

• Radical or Wertheim’s hysterectomy: involves removal of fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, ovaries, nearby lymph nodes and upper portion of the vagina (Women’s Health 2011).

With all types of hysterectomy it is important the woman is fully aware of the procedure that is to be performed and the implications associated with the surgery. There may be issues with feelings of altered self-image, loss of femininity and sexuality. The woman may need counselling to help them work through these feelings. The surgical procedures have a long convalescence postoperatively; the client is unable to return to normal activities for anywhere between 6 weeks and 3 months. It is also important the woman be aware of what to expect in the immediate postoperative phase, such as whether they will have an indwelling catheter, drain tubes or vaginal pack.

A vaginal pack may be inserted after a vaginal hysterectomy and remains in situ for 24 hours. Postoperatively the nurse is required to assess the volume of discharge from the vagina and if there are any difficulties with voiding. If a urinary or suprapubic catheter has been inserted during the operation it may be necessary to commence bladder retraining prior to the removal of the catheter to assist in re-establishing normal bladder sensation and control.

Conditions affecting menstruation

At some time in a woman’s life she is likely to experience some form of benign menstrual problem which will often be painful and debilitating. The main menstrual symptoms include dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, menorrhagia and pain.

Premenstrual syndrome

This is a term used to describe the symptoms experienced by some women in the lead-up to the onset of menstruation. The common symptoms experienced in the 4–7 days before menstruation include transient fluid retention, which may result in oedema in the legs, fingers and abdomen; breast tenderness; headaches and mood swings.

Menopause

Menopause if often described as the ‘change of life’ and signals the end of a woman’s reproductive life. During menopause, eggs are no longer produced by the ovary and the production of oestrogen and progesterone ceases. In most women, menopause will occur between the ages of 45 to 50 years. Premature menopause occurs from 40 years and may occur due to a cessation of ovarian function, after a total hysterectomy or as the result of cancer. A woman is considered to be postmenopausal when 12 consecutive months without a menstrual cycle have elapsed.

The premenopausal woman often describes symptoms such as irregular periods, hot flushes, high sweats, palpitations, vaginal dryness, tiredness, mood swings and crawling sensations of the skin. The woman who believes she is premenopausal can have the diagnosis confirmed with blood tests to determine declining hormone levels. The management of menopause is often determined by the impact of symptoms. Many women try natural therapies such as black cohosh, vitamin E, dong quai, licorice and evening primrose to manage the symptoms. Alternatively, the women may commence hormone replacement therapy (HRT) (see Clinical Scenario Box 35.4).

Clinical Scenario Box 35.4

Anna is a 50-year-old woman who is complaining of increasing ‘sweats and chills’ over the last 4 months. On further questioning she reveals that she has observed increased emotional lability over the past couple of months—crying unexpectedly, feeling depressed and tired all the time. Anna has also noticed her periods have become irregular over the past 12 months. On occasions her periods are heavy, whereas in other months they are very light. She also states that some months she will miss menses. There has also been a loss of sexual drive, with dryness and decreased libido.

Disorders of pregnancy

Spontaneous abortion

Spontaneous abortion is common, with approximately one in four pregnancies resulting in an abortion in the very early stages of a pregnancy. They often occur without the woman being aware of what is occurring. In the event that the abortion is incomplete and products of conceptions are retained in the uterus, there is a high risk of infection and this situation needs to be managed surgically to preserve the integrity of the uterus and to avoid infertility.

Ectopic pregnancy

An ectopic pregnancy occurs where the fertilised ovum implants outside of the uterus. A majority of ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tubes, with only a small number in locations such as the abdominal cavity or ovary. Generally ectopic implantation occurs where the woman has a disorder that slows the passage of the ovum to the uterus such as scarring, endometriosis and tumours. In the initial stages the woman’s pregnancy will show normal signs of conception with amenorrhoea and the hormonal changes; however, as the fetus develops, spotting and cramping may develop and the fallopian tube will rupture, resulting in severe pain and abdominal swelling. Once the tube has ruptured it is considered a surgical emergency if the woman is to survive the rapid blood loss and shock.

Pre-eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia is also referred to as toxaemia and occurs in a small percentage of pregnancies. The condition presents with three characteristic signs: generalised oedema, hypertension and proteinuria. It usually develops about the 20th week of pregnancy. If detected, mild symptoms may be controlled with little risk to fetus or mother; however, in the event that symptoms become unmanageable, the baby may need to be removed by caesarean section.

Breast disorders

The main disorders affecting the breast are:

Mastitis

Mastitis is an inflammatory condition which usually occurs during lactation and breastfeeding, when the infant causes damage to the nipple of the breast allowing entry of bacteria which causes an infection in the ducts of the breast. Most commonly the causative organism is Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus spp. Presentation of the condition includes inflammation, swelling, heat and pain. The infective process may cause abscess formation and cessation of milk flow. Treatment may be symptomatic, for example, use of cold compresses, the use of antibiotics and, where an abscess is present, possible drainage of fluid.

Fibrocystic changes

Fibrosis of the breast is a benign condition caused by hyperplasia of the fibroblasts in breast tissue. Women between 30 and 40 years are more commonly affected and the condition is usually detected as a tender or painful mobile lump often felt just prior to menstruation. The condition is not believed to predispose the woman to cancer.

Cystic changes of the breast occur more commonly in women during the last half of their reproductive life (between 40 and 55 years) and are characterised with single or multiple lumps in the breasts. Each cyst is filled with a thin turgid fluid and, if large, may be visible as a bluish lump under the skin. Each cyst can be drained and the fluid analysed to determine malignancy.

Tumours of the breast

Benign tumours of the breast may include fibroadenoma which is the most common benign breast tumour. The tumour may be very large but rarely gives rise to complications or malignancy. A lumpectomy may be performed to excise and remove the tumours to confirm diagnosis and eliminate the possibility of malignancy.

Carcinoma of the breast usually occurs in women over the age of 50 years, although it may also be diagnosed in younger women. The woman may notice an alteration in the size of the breast, dimpling of the skin, a palpable mass and alteration in the shape, retraction of the nipple, a clear discharge and possibly ulceration. It should be noted that carcinoma of the breast can also occur in males.

Diagnosis of breast carcinoma will initially involve a physical examination of the breast and armpits, a diagnostic mammogram and possibly an ultrasound of the breast tissue. More definitive or invasive tests may be conducted to confirm diagnosis and may include:

Care of the client with a breast disorder

Surgical treatment of breast carcinoma may include a total mastectomy where the entire breast is removed along with lymph nodes from the axilla, or a more conservative approach may be taken—breast-conserving surgery, where the bulk of the breast tissue is conserved. Surgery is usually accompanied by radiotherapy and chemotherapy to eliminate any remaining cancerous cells.

Breast surgery may cause issues with body image, feelings of femininity and sexuality. While reconstructive surgery may be performed, this is often not an option until several months after the mastectomy. Reconstructive surgery involves the formation of a breast mound, nipple and areola. A prosthetic in the woman’s bra may be used in the interim to give the appearance of a normal breast. Hormone therapy may also be indicated to reduce the size of the breast lump prior to attempting a surgical approach.

Preoperative preparation

As with any surgical procedure it is important that the woman is fully aware of the implications of the surgery they are undergoing and is provided with adequate emotional support. It is advisable that the woman be put in contact with a breast support nurse and support networks.

Breast prostheses are available in a range of styles. A soft, lightweight prosthesis is recommended initially while the incision is healing and until tenderness has decreased.

Postoperative care

Physical postoperative care includes providing pain relief, promoting comfort, care of the wound, prevention of complications, exercise instruction and continued emotional support. The woman should be encouraged to perform a series of post-mastectomy exercises to prevent shortening of the muscles and contracture of joints. Gentle exercise also decreases oedema and maintains range of movement in the arm.

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

The performance of a physical examination for any woman is a time of great anxiety and embarrassment. For this reason it should be a priority for every nurse to make the experience as relaxing and comfortable as possible. The presence of a female nurse during the examination by a male practitioner is mandatory in most health facilities. Consideration should also be given to addressing social and cultural requirements when performing a physical examination.

External examinations

Hysterosalpingogram

A hysterosalpingogram (HSG) is an x-ray of the cervical canal, uterine cavity and interior of the fallopian tubes. It usually involves the use of a radio-opaque dye which is injected through the cervix.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography uses high-frequency sound waves to obtain a visualisation of the pelvic organs. It is commonly used to evaluate symptoms of PID or to monitor pregnancy.

Breast examination

A physical examination of the breasts of men and women is referred to as a clinical breast examination. A clinical breast examination involves a thorough physical examination of the whole breast area, including both breasts, nipples, armpits and up to the collarbone. Most of the breast tissue in men (a potential site for malignancy) is located behind the nipple, whereas women have breast tissue throughout the breast.

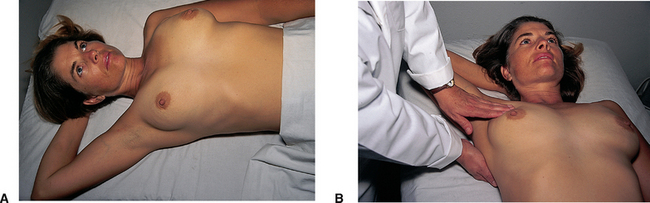

Inspection

Inspect the breasts for size and symmetry. Note breast shape and any masses, flattening, retraction or dimpling. When inspecting the female breast, it may help the client to know what to look for when she inspects her breasts so place a mirror in front of her so that she can see what to look for (Fig 35.6). The nipples are inspected for size, shape, colour, discharge and the direction they point (Crisp & Taylor 2013).

Palpation

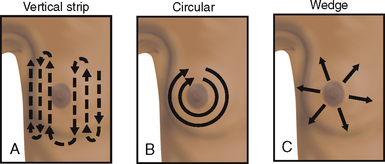

Palpation allows you to determine the condition of underlying breast tissue. Use the pads of the first three fingers to compress breast tissue gently against the chest wall, noting tissue consistency (Fig 35.7). Palpation is performed systematically in one of three ways (Fig 35.8):

1. A back-and-forth technique with the fingers moving up and down each quadrant

2. Clockwise or counterclockwise, forming small circles with the fingers along each quadrant and the tail

3. Palpating from the centre of the breast in a radial fashion, returning to the areola to begin each spoke.

Figure 35.7 A: The woman lies flat with arm abducted and hand under head to help flatten breast tissue evenly over the chest wall B: The nurse palpates each breast systematically

(From Potter PA, Perry AG 2004 Fundamentals of Nursing, ed 6. St Louis, Mosby)

Figure 35.8 Various methods for palpation of the breast. A: Palpate from top to bottom in vertical strips B: Palpate in concentric circles C: Palpate out from the centre in wedge sections

(From Belcher AE (1995) Cancer nursing. St Louis, Mosby)

Until recently, breast self-examination was promoted as an early detection strategy for breast cancer in women. However, there is no evidence that use of specific breast examination techniques makes any difference to the detection of breast cancers. Instead, the Cancer Council Australia (2011) recommends the following guidelines for the early detection of breast cancer:

• Develop breast awareness strategies, which include:

Mammography

The risk of a woman developing breast cancer before the age of 75 years is one in 11 (DoHA 2012). A mammogram is one of the procedures used to detect or confirm the presence of a palpable lump in the breast. The mammogram is an x-ray which is usually provided free for women between the ages of 50 and 69 years as part of the BreastScreen Australia program. It is recommended that the test be done every 2 years. Where there is a familial link to the occurrence of breast cancer it may be recommended to commence screening earlier.

Breast ultrasound

Breast ultrasounds are often scheduled for women under 35 years who have detected a lump in the breast. The ultrasound allows the medical officer to identify whether the lump is fluid filled or solid. In the event of a fluid-filled cyst, the medical officer can perform an ultrasound-guided aspiration of fluid for analysis. The procedure is ideal for the pregnant woman who detects a lump because there is little risk to the growing fetus.

Internal examinations and sampling

Papanicolaou test

The Papanicolaou test (Pap smear) involves the collection of superficial cells from the surface of the cervix which are examined under microscopic analysis to diagnose changes which may be suggestive of cervical cancer. Changes to cervical cells may occur due to acute or chronic inflammatory disease, benign tumours such as polyps and premalignant and malignant carcinoma. To perform the test, the medical officer inserts a vaginal speculum into the vagina and a cytobrush is used to scrape the surface of the cervix and collect cells which are then transferred onto a microscope slide and fixed with ‘cytospray’ before being sent for analysis.

All women over the age of 18 years who have ever had sex should have a Pap smear every 2 years, even if they are no longer sexually active, as cervical cancer can take up to 10 years to develop (DoHA 2011).

Pelvic examination

The pelvic examination is often performed in conjunction with the Pap smear, although where there is clinical indication it may be performed as a diagnostic method to palpate the ovaries and uterus. Initially the medical officer inserts two gloved fingers into the vagina and applies gentle pressure to the lower abdomen. A speculum is then inserted into the vagina to allow visualisation of the vagina and cervix.

Colposcopy

A colposcopy usually occurs during a Pap smear or physical examination when, after the insertion of the speculum, a colposcope is used to magnify and illuminate the cervix. A biopsy of the cervix may be completed during the procedure.

Cervical biopsy

A cervical punch biopsy is the removal of a small column of cervical tissue. The cervix is compared to a clock face and biopsy tissue labelled accordingly. Cone biopsy is the removal of a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix. Possible complications after the procedure are haemorrhage and infertility due to the removal of mucus-producing glands, and the formation of scar tissue (Cancer Australia 2011c).

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopic procedures are used to visualise the organs in the pelvic cavity and reproductive organs. Laparoscopy involves three to four small incisions into the abdomen and the use of probes which allow the surgeon to make a diagnostic examination, take biopsies or possibly to perform surgical procedures.

WOMEN’S HEALTH PROMOTION

There are a number of national health promotion strategies that address target areas of health risks throughout Australia. Information and education is available in many languages through state, territory and federal health departments. Strategies cover the prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), choosing a suitable contraceptive method and screening for cervical, breast and ovarian cancer. The nurse plays an integral part in the promotion of health, education and support of the client. The nurse should reinforce the medical officer’s explanation about any implications for the individual’s lifestyle and ensure that the information is understood. It may also be necessary to provide information about fertility control and prevention of STIs.

The nurse should be aware of the changes that occur to the normal reproductive structures and functions throughout the life span and be able to determine alterations. It is the role of the nurse to actively promote reproductive and sexual health through client teaching, education and health promotion strategies. Client teaching is implemented by educating clients about normal developmental changes that occur throughout the life span.

Health-promotion strategies and programs should be adapted to local needs, taking into account social, cultural and economic structures.

BreastScreen

Breast examination by a healthcare professional is recommended as a health screening component when women present for regular Pap smears.

Pap smear

Cervical cancer is one of the most preventable and curable of all cancers. It is estimated that most cases of squamous cell carcinoma could be prevented if cell changes were detected and treated early. The Pap smear is performed to obtain a scraping of cervical cells and is currently the best available screening tool for preventing the development of cervical cancer.

In 1991 Australia began what is now known as the National Cervical Screening Program (see Clinical Interest Box 35.4). This joint federal–state/territory-funded program recommends and encourages women to have Pap smears every 2 years throughout their lives. States and territories maintain cervical cytology registries. Women automatically go on the register unless they specifically ask to be excluded. Confidential records and results are retained on a database. Reminders are sent to women on the register when Pap tests are overdue (PapScreen Victoria 2011).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 35.4 Client teaching—Pap smears

• All women with a cervix who have ever had sex in their life are at risk of cervical cancer

• Approximately half of new cases of cervical cancer each year are in women under 50 years of age

• Regular PAP smears every 2 years can prevent up to 90% of the most common types of cervical cancer

• Unless the woman has had a total hysterectomy they should be advised to have a Pap smear every 2 years

• If the woman is 70 years or over and has had two normal Pap smears in the last 5 years, they should be advised that they no longer need to have this test

CONTRACEPTION

A variety of contraceptive options are available for both men and women. The option chosen will be dictated by cultural, economic and personal factors and possibly the time available.

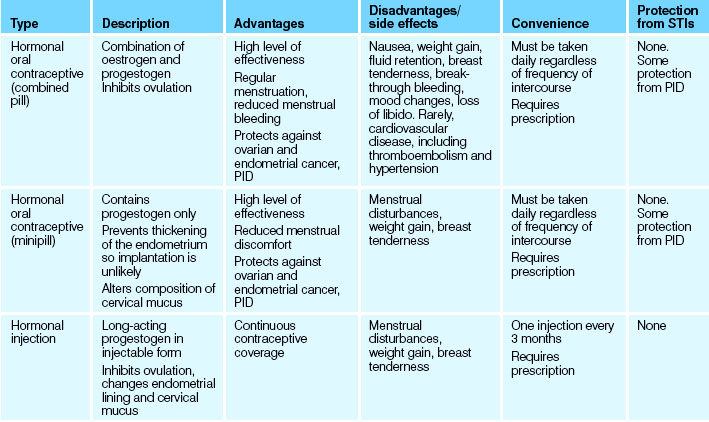

Contraception is used in females to prevent ovulation, fertilisation or the successful implantation and development of a fertilised ovum. Women have a number of options available, but there is limited choice for men—use of a condom or a vasectomy.

For most women, selecting and using a method of contraception is a significant decision. Choices about birth control are possible because of safe and available methods of contraception.

Clinical Interest Box 35.5 outlines the decline in fertility rates over the last 100 years.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 35.5 Reproduction—choices

• Reproduction is influenced by physiological, psychological, social, religious, economic and environmental factors. Choices about family planning are available, including the choice not to have children

• Since 1901 Australia has experienced two long periods of fertility decline: from 1907 to 1934, and from 1962 to the present. Fertility peaked in 1961 when the total fertility rate reached 3.5 babies per woman

• By 1966 the total fertility rate had fallen to 2.9 babies per woman. Changing social attitudes, in particular a change in perception of desired family size, facilitated by the availability of the oral contraceptive pill, led to this decline

• During the 1970s the total fertility rate dropped again, falling to 2.1 babies per woman in 1976, where it has remained. This fall has been linked to the increasing participation of women in education and the labour force, changing attitudes to family size, lifestyle choices and greater access to contraceptive measures and abortion

• The proportion of women remaining childless has increased over time in all age groups. For women aged 25–29 in 1981, 35% were childless, while 59% of women of the same age in 2001 were childless. In 1981, 8% of 40–44-year-old women were childless. By 2001 this increased to 13% of women (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2003)

• In a report released by ABS in 2010, it reveals that in 2006 14% of women between 45 and 49 years had not had any children, which shows a continuation in the trend for women to remain childless (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010)

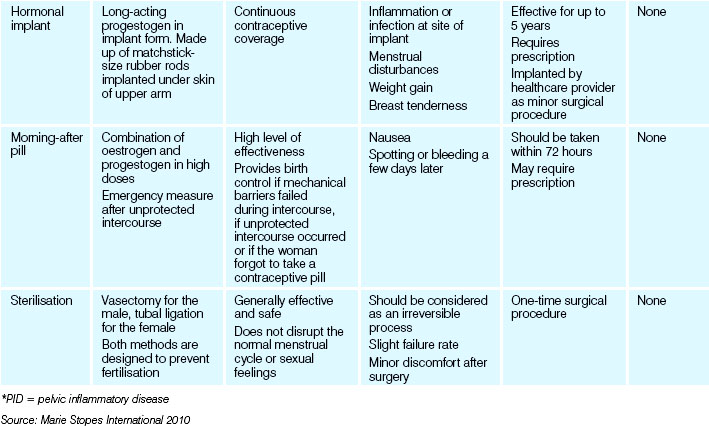

It should be noted that not all methods of contraception are 100% effective. Each method has a number of advantages and disadvantages (see Table 35.7). Birth control methods may be classified as:

DISORDERS OF REPRODUCTION

Infertility

Infertility is defined as the inability of a couple to achieve conception after a year of unprotected intercourse, or the inability to carry pregnancies to a live birth (Fertility Society of Australia 2011). It is estimated that one in six couples suffers infertility, with a number undergoing both surgical and medical treatment or lifestyle changes. In many instances, no cause can be determined.

Male factors

Many factors can affect the production, transport or ejaculation of sperm and the process can be interrupted by a number of causes, many of which have been discussed within this chapter; for example, excessive heat or tight clothing causing an increase in the temperature of the testes and inhibiting sperm production (see Table 35.8). Hormonal dysfunction of the anterior pituitary gland or hypothalamus will affect testicular function. Autoimmune factors may also be implicated. Diseases such as coeliac disease, diabetes mellitus and alcoholism may prevent normal spermatogenesis.

Table 35.8 Known causes of male infertility

| Sperm production problems | |

| Blockage of sperm transport | |

| Sperm antibodies | |

| Sexual problems (erection and ejaculation problems) | |

| Hormonal problems |

Adapted from Factsheet: Male infertility, Professor Rob McLachlan, Andrology Australia, 2010

Female factors

Most female infertility problems are the result of ovulation problems. Stress, diet or rigorous athletic training are lifestyle factors that can affect hormonal balance. Conditions affecting the female reproductive system and which result in infertility in women have been identified; they include structural abnormalities, endometriosis and scarring from PID.

Assessment of infertility