CHAPTER 37 Mental health

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to:

• Understand the continuum of mental health and mental illness

• Identify factors that influence the development of mental health

• Reflect on the causes and impact of stigma on people with mental illness

• Understand the roles of the mental health nurse and the mental health team

• Gain an overview of the care issues involved when clients experience anxiety, depression, aggressive, self-destructive, hyperactive or confused behaviour

• Develop an awareness of some of the basic legal and ethical issues in the field of mental health nursing

Mental health nursing is a specialised field of nursing. A variety of educational programs is aimed at preparing mental health nurses (MHNs) to work specifically and effectively with clients who have mental health disorders. A nurse who has not undertaken a course specific to mental health nursing may be required to assist in caring for a client with a mental illness. The nurse may be required to work in a psychiatric unit or ward within a general hospital, or to assist in caring for a client who has been admitted to a general medical or surgical ward with a physical illness but has a concurrent mental health problem. It is therefore important that every nurse has a basic understanding of mental health, mental illness and the principles of care related to clients who are experiencing a disturbance in mental wellbeing. It is not the aim of this chapter to provide the reader with comprehensive knowledge and skills to care for clients with mental health disorders. Rather, this chapter aims to introduce nurses to the basic concepts of mental health nursing, some of the theoretical frameworks that underpin psychiatric care and to raise awareness of some legal and ethical issues that confront mental health nurses. The texts and online resources listed at the end of this chapter provide more detailed information.

I would wake up in the morning feeling like I didn’t want to face the day. There was a black cloud hanging over me. I wanted to stay in bed and shut out the world. I felt at these times that I was in an absolute pit of hopelessness and despair about life and I didn’t want to go on. I was a burden to myself and my family. My sister took me to see my doctor and I was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. I didn’t want to be there because I believed no one could help me. After some time the nursing care and antidepressant medication I was prescribed helped me to slowly climb out of my pit of despair. One day I found myself enjoying looking at the autumn leaves falling and I knew that I was getting better. Now I understand that depression is a severe illness and I will look for help when I feel myself slipping back.

CONCEPTS OF MENTAL HEALTH AND MENTAL ILLNESS

Perhaps the most important aspect of understanding mental illness is being able to define the difference between mental illness and mental health. This first section aims to help nurses gain an understanding of mental health and mental illness and the factors that impact on both.

What is mental health?

The concept of mental health is difficult to define, as mental health is much more complex than merely the absence of a mental illness. There are numerous definitions of what constitutes mental health. It has been defined as a state in which people are able to cope with, and adjust to, the recurrent stresses of everyday living in an acceptable way (Watkins 2002). It has also been defined as the ability of people to cope well with stress both internal and external (Antai-Otong 2007). According to Barkway, ‘a person can enjoy mental health regardless of whether or not they are diagnosed with a mental illness if they have a positive sense of self, personal and social support with which to respond to life’s challenges, meaningful relationships with others, access to employment and recreation activities, sufficient financial resources and suitable living arrangements’ (cited in Elder et al 2009:120). For most people the feelings associated with mental health will be present sometimes and not others and will vary in intensity at different times. According to this view, then, mental health is a state that can change frequently and that can fluctuate according to specific circumstances. Touhy & Jett (2009) capture the concept of fluctuation in this definition:

Mental health is like a violin with strings of interaction, behaviour, affect (mood) and intellect. All of this together may produce a pleasant or stimulating melody, or they may be discordant and irritating. The tune constantly changes. No one is entirely mentally unhealthy and no one is fully mentally healthy at all times.

The terms mental health and mental illness are often used interchangeably but they should not be: the difference between the two needs to be clear (Elder et al 2009). The American Psychiatric Association (APA) defines mental illness or mental disorder as an illness or a syndrome with psychological or behavioural manifestations and/or impairment in functioning due to a social, psychological, genetic, physical/chemical or biological disturbance (Shives 2005:12).

Clinical Interest Box 37.1 illustrates some differences between mental health and mental illness.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 37.1 Some differences between mental health and mental illness

(Compiled from Varcarolis et al 2010)

| Signs of mental health | Signs of mental illness |

|---|---|

| Happiness | Major depressive episode |

| Control over behaviour | Control disorder: undersocialised, aggressive |

| Shows repetitive and persistent pattern of aggressive conduct in which the basic rights of others are violated | |

| Appraisal of reality | Schizophrenic disorder |

| Effectiveness in work | Adjustment disorder with work (or academic inhibition) |

| Shows inhibition in work or academic functioning whereas previously there was adequate performance | |

| Healthy self-concept | Dependent personality disorder |

| Satisfying relationships | Borderline personality disorder |

| Effective coping strategies | Substance dependence |

| Repeatedly self-administers substances despite significant substance-related problems (loss of employment, family and social networks) |

Development of mental health

According to Shives (2008) the factors that influence the development of mental health relate to three main areas: inherited characteristics, nurturing during childhood and life circumstances.

Inherited characteristics

It is believed by some theorists that the ability to maintain a mentally healthy and positive outlook on life is in part connected to a person’s genetic make-up, just as inherited defective genes are thought to predispose particular people to illnesses such as schizophrenia and depression.

Nurturing during childhood

Nurturing during childhood relates primarily to the relationships that develop between children, their parents and their siblings. It is thought that positive relationships, those that promote feelings of being loved, secure and accepted, facilitate the development of children into mature and mentally healthy adults. It is thought that negative relationships may result when children experience maternal deprivation, parental rejection, serious sibling rivalry and early communication failures. Such relationships are more likely to result in a poor sense of self-worth and a lower level of mental health (Shives 2008). The quest for a sense of self begins in childhood; children who have positive nurturing experiences are more likely to have a stronger sense of identity than those who have negative nurturing experiences (Watkins 2002).

Life circumstances

Life experiences can influence mental health from birth onwards. Positive life experiences include pleasurable times and success at school and with friends, a good job, financial security and good physical health. Negative experiences include poverty, poor physical health, unemployment and unsuccessful personal relationships (Shives 2008).

Different people will react to childhood experiences and life circumstances in different ways. Some, despite negative circumstances, will develop positive strategies for coping and will not become mentally ill. Generally it is people who have not achieved a strong sense of identity who are more prone to mental illness (Watkins 2002). Perhaps this is most clearly understood when considering the mental health of Indigenous populations. It is not difficult to imagine how the effects of colonisation, the removal of children from their families, the loss of traditional lifestyle and cultural practices and the resulting social disruption may impact negatively on mental wellbeing. It is generally understood that the difficulties involved in belonging and adjusting to two different cultural contexts can make it difficult to establish a strong sense of identity. The difficulties faced by Indigenous people have led to some serious mental health concerns. For example, there are worrying levels of depression, substance misuse, self-harm, harm to others and suicide in Aboriginal people in Australia that are at higher rates than in the non-Indigenous population (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2011).

Nurses working with Indigenous people can better empathise and not negatively judge behavioural signs of mental ill-health if they recognise that it often stems from deep mental anguish and spiritual sorrow relating to the effects of European invasion (Brown 2001).

What is mental illness?

Just as it is difficult to arrive at a precise definition of mental health, so too is it difficult to succinctly define mental illness because it is often related to what a given society considers is normal or acceptable behaviour and, as with mental health, mental illness is a matter of degree.

What society considers normal

People tend to evaluate the behaviour of others based on their own social, cultural, ethical and behavioural standards. Therefore, behaviour that is regarded by one person as acceptable and normal may be perceived by another person as totally unacceptable. In addition, what is accepted as normal in a society may change over time. For example, homosexuality was previously considered a diagnosable clinical mental disorder but is now no longer classified as a mental disorder (Antai-Ojong 2003). When a person’s behaviour is in question it is appropriate to ask ‘Who is qualified to decide whether this behaviour is acceptable or not?’ and ‘What is the meaning and relevance of this behaviour in relation to the context in which it is occurring and to the person’s society, religion and culture?’

In every society and cultural group there are different interpretations of certain behaviours and events. For example, in western psychiatric terms, visual or auditory hallucinations (images or sounds that are seen or heard by an individual but by no one else) are viewed as abnormal and a sign of mental illness, whereas in some cultures these happenings are viewed as experiences of symbolic and spiritual importance and those experiencing them may be revered as visionaries rather than mentally ill (Varcarolis et al 2010).

A matter of degree

Anxiety, fear, anger, sadness and the need to be alone are feelings commonly identified in mental illness but they are normal feelings experienced at different levels of intensity by most people at various times. Depending on the intensity of the emotions, people may not feel as mentally healthy as they do at other times but will not necessarily be classified as mentally ill. It is when the feelings are exaggerated and extend over longer periods of time than deemed normal that the person is likely to seek professional help and be diagnosed as having a mental illness. For example, a diagnosis of a depressive disorder is likely when sadness or feelings of being ‘down in the dumps’ become deep, long-lasting feelings of despair that the person cannot escape from without professional help. Mental illness or mental disorder are therefore terms used to designate changes from normal mental functioning that are sufficient to become, and be diagnosed as, a clinical disorder. Broadly, mental illness can be defined as a state in which an individual exhibits disturbances of emotions, thinking and/or action, but it can be defined in a multitude of ways.

Clinical Interest Box 37.2 provides a range of definitions of mental illness.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 37.2 Definitions of mental illness

• Mental illness is a term that refers to all the different types of mental disorders. These include disorders of thought, mood or behaviour that cause distress and result in a reduced ability to function psychologically, socially, occupationally or interpersonally (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research 2002)

• A disease that causes mild to severe disturbances in thought and/or behaviour, resulting in an inability to cope with life’s ordinary demands and routines (National Mental Health Association (USA) 2012)

• A disorder causing abnormal behaviour more often than in most people (Shives 2005)

• Psychopathology exhibiting frequent irresponsibility, the inability to cope, being at odds with society and an inaccurate perception of reality (Shives 2005)

• The absolute absence or constant presence of a specific behaviour that has social implications regarding its acceptance (Shives 2005)

• The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a classification system for mental illness. In the fourth edition (DSM-IV), mental illness is defined as being a clinically significant behaviour or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in an individual and that is associated with present distress (e.g. painful symptom) or disability (i.e. impairment in one or more areas of functioning) or with a significantly increased risk of suffering death, pain, disability or an important loss of freedom. In addition, this syndrome or pattern must not be merely an expectable culturally sanctioned response to a particular event, for example, the death of a loved one. Whatever its original cause, it must currently be considered a manifestation of a behavioural, psychological or biological dysfunction in the individual. Neither deviant behaviour (e.g. political, religious or sexual) nor conflicts that are primarily between the individual and the society are mental disorders unless the deviance or conflict is a symptom of a dysfunction in the individual, as described above (American Psychiatric Association 2002).

There is no clear line that divides mental health from mental illness; the two grade into one another.

Table 37.1 provides some areas of comparison between the two but it should be noted that, while these are general traits that mentally healthy or mentally ill people tend to share, different types of mental illness manifest with different effects and with different levels of intensity. In addition, mentally healthy people may experience more than one type of mental dysfunction at different periods in their lives.

Table 37.1 Areas of comparison between mental health and mental illness*

| Attribute | The mentally healthy person | The mentally ill person |

|---|---|---|

| Self-concept | ||

| Relationships | Inability to cope with stress can result in disruption, disorganisation, inappropriate responses and unacceptable behaviour that make it difficult to meet the expectations of others in work or social environments. This means that there may be an inability to establish or maintain meaningful relationships. These factors may result in a limited social support network | |

| Outlook on life | Optimistic and positive view, sense of purpose and satisfaction | Tends to a pessimistic negative view of present and future |

| Coping and adaptation | Able to tolerate stress and return to normal functioning after stressful events. Can cope with feelings such as frustration and aggression without becoming overwhelmed | Can feel overwhelmed by even minor levels of stress and may react with maladaptive behaviour |

| Judgment/decision making | Uses sound judgment to make decisions and is able to problem solve | May display poor judgment and avoid problems rather than attempting to solve them |

| Characteristics/traits | Can delay gratifcation | May feel an urgency to have personal wants and needs met immediately and may demand immediate gratifcation |

| Level of functioning | ||

| Perceptions | Able to differentiate between what is imagined and what is real because can test assumptions by considered thought. Can change perceptions in light of new information | May be unable to perceive reality |

* It should be noted that these are general points only. Different types of mental illness manifest with different effects and, while there are traits that mentally healthy people tend to share, many mentally healthy people may experience several areas of dysfunction at different periods in their lives. Mental illness may occur as a temporary inability to cope; it may occur episodically with long periods of mental health in between; or it may occur as a chronic condition that is constantly present.

Signs and symptoms of mental illness

Symptoms of mental illness occur on a continuum and range from minimal to severe (Antai-Ojong 2003). A person usually receives a diagnosis of having a mental illness when the level of mental distress causes them to seek professional help or when others in society perceive that they need professional psychiatric help. It is important to recognise that, in relation to the differences between mental health and mental illness, there is a ‘grey’ area into which all individuals may enter from time to time. Those with a severe and long-term psychiatric disorder may dip back into relative mental health and reality-based living for a while and, similarly, sometimes the stresses of everyday living are so overwhelming that the most well-adjusted ‘normal’ person may experience marked irrational thoughts, feelings and actions. Therefore, as in the case of physical illness such as diabetes, heart disease or cancer, anyone can develop a mental illness. A mental illness is not the fault of the person affected, and the cause may be related to a combination of biological, psychological and sociocultural factors.

Symptoms of mental illness include changes in personal habits, social withdrawal and changes in mood and thinking. While particular symptoms occur with specific disorders, there are warning signs that indicate the presence of a mental health problem. Clinical Interest Box 37.3 provides examples of early warning symptoms of mental illness that may occur in children, adolescents and adults.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 37.3 Warning signs and symptoms of mental illness

People may have one or two of these or other symptoms at any one time. This does not necessarily mean there is cause for alarm, but it is advisable they be assessed professionally. A combination of multiple symptoms is a strong signal that professional assessment and help should be sought as soon as possible.

In younger children

• Decline in standard of performance in school work or activities that does not pick up again over time

• The child is not managing or coping with tasks as expected at their developmental age

• Suggestions from teachers that there may be a learning difficulty, a behavioural problem or a problem making friends

• Persistent crying, waking at night or nightmares

• Persistent disobedience or aggression

• Excessive anxiety (e.g. preoccupation with fears of burglars, barking dogs, parents getting killed)

• Constant fighting with other children, and reports from school of the child being ‘angry or disruptive’

• Refusal to go to bed, inability to sleep or a need to sleep with, or close to, parents

• Decreased interest in playing

• The child tries to stimulate themself in various ways (e.g. hair pulling, rocking of the body, head banging)

• The child constantly says things that indicate low self-esteem (e.g. ‘I’m dumb’, ‘I never do anything right’, ‘No one likes me’, ‘I’m too skinny’, or too fat, too tall, too ugly, etc)

In older children and adolescents

• Frequently asks or hints at the need for help

• Fears or phobias that interfere with normal activities

• Change in sleeping/eating/hygiene habits

• Isolating self from others excessively

• Involved in beating up others

• Inability to cope with problems and usual daily activities

• Excessive complaints about physical aches and pains

• Defiance of authority, truancy, theft and/or acts of vandalism

• Demonstrates ritualistic behaviours (e.g. preparing for bed, a meal or going out) using routines that are exact, precise and never vary

• Provocatively sexual behaviour that is not appropriate

• Participates in mutilating or killing animals

• Persistent and prolonged low mood (a major concern, especially if accompanied by poor appetite or thoughts and talk of death or signs of self-mutilation)

In adults

• Prolonged periods of sadness/low mood and apathy

• Feelings of extreme highs and lows

• Unrealistic or excessive fears

• Marked changes to eating/sleeping/hygiene or other habits

• Strong feelings of anger/outbursts of violent behaviour

• Increasing inability to cope with usual activities of everyday life

• Denial of anything being wrong even in light of obvious problems

• Numerous unexplained physical ailments

• Thoughts/talk about suicide or homicide (professional help needed immediately)

(American Psychiatric Association 2002; National Mental Health Association (USA) 2012)

Who is most at risk of developing a mental illness?

Anyone can develop a mental illness but some groups of people in society are particularly at risk. Clinical Interest Box 37.4 identifies groups of people at greater risk of mental illness.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 37.4 People at risk of mental illness

Anyone can develop a mental illness, but people at particular risk include:

• Adolescents: adolescents face a period of enormous physical, psychological and social change. Some adolescents may not have sufficient resources to cope with the demands placed on them at this challenging stage of life and to complete the developmental tasks necessary to move successfully from adolescence to adulthood. Erik Erikson’s theory of personality development (Erikson & Erikson 1997) is one that is useful to explore in relation to life stages and developmental tasks

• New parents: new parents face a multitude of stressors (things that trigger a stress response) as well as many pleasures connected with a new baby. Stressors may include conflict over the acceptance of the pregnancy, transition from being a couple to being parents, loss of financial income, a baby’s constant demands and anxiety about the infant’s welfare

• Women: women face factors such as a disadvantaged status in society, internal conflict arising from decisions about whether to pursue a career, become a home-maker or try to achieve both, or being subjected to domestic violence or abuse. These are social factors that may possibly predispose some women to mental illness

• Older adults (male and female): older adults may face many stressors, including loss of work role status because of retirement, reduced income, fear of declining physical and mental abilities, relocation, death of a partner and/or friends and siblings of similar age. The effect of these multiple losses may accumulate and leave some older adults at risk of mental illness

• Refugees and migrants: these people may experience a grief reaction on leaving their homeland, friends and family to live in a country where the cultural practices, values and beliefs are different and where they may be considered of low status and worth. It may be difficult for some migrants to work successfully through their grief because of language barriers, the stress from job and financial uncertainty and lack of support from relatives and friends left behind. Some refugees and migrants may experience problems of adjustment, isolation and loneliness, each of which may contribute to mental illness. In some cases refugees have experienced torture and trauma in their country of origin, which creates a high risk of developing a posttraumatic stress disorder (Griffiths et al 2003)

• Physically or intellectually impaired persons: factors such as isolation, lack of meaningful relationships, social restrictions caused by disabilities, poor self-esteem and negative stigmatising community attitudes towards people with disabilities are all aspects of experience that can elevate the risk of mental illness, particularly anxiety and depression (Dewer & Barr 1996)

Many people from all age groups and of different social, educational and cultural backgrounds cope with highly stressful events and accumulative stressors.

Classification of mental disorders

There are more than 200 classified forms of mental illness. These include:

• Cognitive disorders (e.g. dementia, delirium)

• Substance-related disorders (e.g. alcohol abuse or dependence, drug abuse or dependence)

• Anxiety disorders (e.g. phobias, panic disorder, obsessive disorder)

• Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (e.g. paranoid or catatonic-type schizophrenia)

• Mood disorders (e.g. depression, bipolar disorder (mixed mood))

• Personality disorders (e.g. antisocial personality disorder, dependent personality disorder)

Diagnosis

The APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a respected and influential classification system under which a mental illness is determined according to the symptoms experienced and the clinical features of the illness. The International Classification of Disease (ICD) is produced by the World Health Organization and is mainly used In Europe. It also assists with diagnosis and classification. In Australia, New Zealand and the United States the fourth edition of the DSM (DSM-IV-TR) is most commonly used. (DSM-V is due for publication in May 2013.)

There are many categories of classification but mental illness is mainly classified within the following areas:

• Thought disorders, such as schizophrenia, which disrupt the ability to think and perceive things clearly and logically and can impair a person’s perception of reality

• Mood disorders, which affect how a person feels and can result in persistent low mood (depression) or cycles of low mood and euphoria (bipolar disorder)

• Behavioural disorders, which involve people acting in potentially destructive ways, including eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia

• Mixed disorders, which have components of two or more of the other categories (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research 2002).

Diagnosis according to the DSM (IV) has the benefit that clients may feel great relief when they have a diagnosis that helps them make sense of what is happening to them, and a medical diagnosis can guide clinical treatment. But this diagnostic system has a disadvantage in that a diagnosis can also be a label that has negative connotations; for example, a label of schizophrenia or a personality disorder is associated with significant social stigma. Diagnostic labels describe certain types of behaviour but they indicate very little about the nature or causes of the experience.

Mental health nurses develop nursing diagnoses in response to the client’s experience, emotions and behaviours. Nursing care responds holistically to the client’s biological, psychosocial, spiritual and environmental needs and specifically addresses the client’s feelings and behavioural responses to those feelings, many of which are common across several different medically classified conditions. Examples of some nursing diagnoses commonly used in mental health nursing are provided in Clinical Interest Box 37.5.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 37.5 Examples of identification of issues by nurses used in mental health nursing

• Impaired social interaction: insufficient or excess quantity or ineffective quality of social interactions

• Ineffective coping: inability to form a valid appraisal of the stressors, inability to use available resources

• Chronic low self-esteem: long-standing negative feelings about self or own capabilities

• Self-care deficit: impaired ability to perform or complete activities of daily living (e.g. hygiene, toileting, nutrition)

• Imbalanced nutrition, less than body requirements: intake of nourishment insufficient to meet the body’s metabolic needs

• Powerlessness: perception that one’s own actions will not significantly affect an outcome; a perceived lack of control over a current situation

• Disturbed thought processes: disruption in cognitive abilities and activities

• Disturbed sensory perceptions: alteration in the amount or patterning of incoming stimuli accompanied by a diminished/exaggerated/distorted/impaired response to the stimuli (often used for clients who are experiencing delusions, hallucinations or illusions or have impaired awareness of self/environment)

• Impaired verbal communication: diminished, delayed or impaired ability to understand or transmit verbal messages

• Dysfunctional grieving: prolonged unsuccessful use of strategies and responses by which people attempt to work through the process of grieving

• Risk for injury: potential for injury as a result of environmental conditions interacting with the client’s adaptive and defensive resources

• Risk for self-directed violence; risk for other-directed violence: existence of the potential for an individual to be physically, emotionally or sexually harmful to self or others

• Risk for suicide: potential for self-inflicted life-threatening injury

A mental disorder can be categorised as temporary, episodic or chronic/enduring, according to the way it manifests:

• Temporary: a temporary inability to cope; for example, a single experience of depression. The vague definition of ‘a nervous breakdown’ is a common non-medical term for this kind of isolated non-recurring illness

• Episodic: an illness that occurs episodically; for example, recurrent episodes of a disabling condition such as bipolar disorder (once known as manic depression) or schizophrenia. While the condition is disabling when it occurs, the person affected can often enjoy a comparatively normal life for much, if not most, of the time

• Chronic/enduring: a constant disabling and unrelenting illness that is extremely challenging for the affected person and their families to deal with; for example, a chronic type of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder or irreversible dementia can be disabling.

Although use of the terms psychosis and neurosis to describe particular illnesses is no longer favoured, nurses need to be aware of the meanings associated with each as the terms are still used in some contexts. The terms are out of favour because symptoms ascribed to each condition can occur in the other, and this causes confusion. The term psychosis refers to disorders that are so marked and incapacitating that the person who is afflicted is out of touch with reality and lacks insight into the illness and the associated behaviours, which may be unusual or bizarre. Psychosis was the term traditionally used to describe disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, in which the symptoms experienced were quite different to those experienced by other people and included delusions and hallucinations (Elder at al 2009). Clinical Interest Box 37.6 provides explanations and examples of delusions and hallucinations.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 37.6 Delusions and hallucinations*

(Fortinash & Holoday Worret 2007; Shives 2005)

| Delusion: a fixed thought or belief that is not reality based or true, is not consistent with the person’s level of education and development or cultural background, and is not amenable to reason. It is categorised as a thought disorder |

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Somatic delusions (a false belief involving a body part or function) | A young woman believes her body is rotting away from the inside, her heart is made of ice and is gradually melting because she doesn’t deserve to live |

| Nihilistic delusions (false feeling that the self, others or the world is non-existent) | A client refuses to eat, saying there is no need for him to eat because he has no body |

| Delusions of persecution (oversuspiciousness: the person falsely believes themself to be the object of harassment) | A client believes the staff belong to a cult, are watching his every move and are out to get him. He is afraid to go to sleep for fear of what the staff might do to him |

| Delusions of control (false belief that one is being controlled by an external source) | A client believes her feelings, thoughts and actions are being controlled by aliens who send messages to her via the television, instructing her on what to do |

| Delusions of grandeur (exaggerated beliefs about personal importance or powers) | A client believes he is God and controls the universe |

| Delusions of self-depreciation (beliefs of unworthiness) | A client believes she is ugly and sinful, saying, ‘I don’t deserve to be loved—look at me—it shows that I am full of sin’ |

| Hallucinations: sensory perceptions that are not founded on any external stimuli. They may involve any of the five senses. They are most commonly visual or auditory | |

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Visual hallucination | A client tells you that he sees his deceased wife in different areas of his home |

| Auditory hallucination | A 16-year-old client tells you she hears voices in her head saying derogatory things such as, ‘You are worthless, you don’t deserve to live’ |

| Gustatory (taste) hallucination | A middle-aged client with organic brain syndrome complains of a constant metallic taste in his mouth |

| Olfactory hallucination | A 30-year-old client states that she smells ‘rotten garbage’ in her bedroom although no one else can smell anything unusual or unpleasant |

| Tactile hallucination | A middle-aged woman undergoing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal reports feeling ants crawling all over her body although no ants are present |

* Clients can experience delusions and hallucinations together. For example, a client may hear her dead daughter’s voice, see her standing close by and be convinced that she caused her daughter’s death despite of evidence to the contrary that her daughter died as a result of injuries received in a car accident when on holiday with a friend.

Unlike people suffering from a psychotic disorder, those with what used to be termed a neurosis have insight into their condition. For example, a person who has an obsessive-compulsive disorder may experience persistent and intrusive thoughts (obsessions) about personal cleanliness. To decrease the level of anxiety the person may wash their hands hundreds of times a day, even if their hands become red and raw (compulsion to act). When they are extreme, such thoughts and acts may be so unusual and disrupt the person’s life to the degree that to the observer the person is mentally ill. Unlike those experiencing a psychotic disorder, the affected person is aware that the behaviour is abnormal (there is insight into the behaviour and the illness). Despite their condition, people who have what was once classified as a neurosis can often continue to function in society, whereas a person who is psychotic cannot function effectively (Varcarolis et al 2010). Nursing diagnosis should always be developed through the lens of a client-centred approach which respects the client’s social and individual experience of their illness.

Theoretical models and causation of mental illness

Historically the medical profession was prominent in the care of people with mental illness and as a result there has been, and still is, a strong focus on identifying physical causes of mental illness. However, others have looked at psychological, sociocultural, interpersonal and human development factors and there are now many theoretical models used to explain the presence of a mental disorder. Mental health nurses select concepts from the various relevant models that best explain the client’s behaviours, problems and needs. They then draw on these concepts as a basis for client assessment and then for planning, conducting and evaluating care (Varcarolis et al 2010). The following provide very basic examples of a small selection of theoretical models. To work effectively in the area of mental health, however, nurses need a deep and sound understanding of a wide range of models.

The medical or biological model

This model explains mental illness as being caused by physiological malfunction in the body. Physical causes can be separated into acquired and non-acquired factors. Acquired causes include head injury, cerebral infection and substance misuse. Non-acquired causes include genetic transmission, electrical conductivity changes in the brain or alterations to the production and/or activity of neurotransmitters (Elder et al 2009). There is evidence to support biological explanations. For example, studies indicate that depression and schizophrenia may be linked to abnormal neurotransmitter function, and that genetic factors may be linked to both (Elder et al 2009). A medical approach to treating mental illness tends to focus primarily on medication and sometimes includes electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), both of which aim to correct chemical imbalance in the body believed to be caused by abnormal neurotransmitter function in the brain. Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) is a theorist associated with the origins of the medical model.

Psychological and psychodynamic models

The psychoanalytical model, first conceptualised by Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), is possibly the best known model in this group. Freud’s model viewed human personality as developing predominantly within the first 5 years of life and focused mostly on unconscious, non-rational and instinctual parts of human behaviour (Varcarolis et al 2010). Freud attributed disrupted behaviour in the adult to developmental tasks that were not accomplished successfully at earlier developmental stages. For example, within this theoretical framework a mental illness may be linked to a failure during adolescence to move successfully from dependence on parents to independence. Freud’s mode of treatment was psychoanalysis, which aimed to bring unconscious problems to conscious awareness.

Carl Jung (1875–1961), Melanie Klein (1882–1960) and Erik Erikson (1902–1994) are some of the theorists who expanded on Freud’s thinking about the nature of human development and behaviour. Erikson’s theory has provided nurses with a developmental model that encompasses the entire life span. Erikson studied healthy personalities and focused on human strengths as well as weaknesses, emphasising how people who failed to achieve developmental milestones at various life stages could rectify these failures at later stages (Elder et al 2009).

It was Freud who identified the manner in which humans develop and used defence mechanisms to ward off anxiety that might otherwise be overwhelming and incapacitating (Varcarolis et al 2010). Defence mechanisms prevent conscious awareness of threatening feelings and can be a helpful response in adapting to stress, but their overuse can be a sign of maladaptation to stress and an indicator of mental ill-health. They are particularly relevant in understanding stress-vulnerability and stress-adaptation models of health and illness. Stress-vulnerability/adaptation models recognise that throughout life there is a need for everyone to adapt to change, for example, to adjust to school and then work life, to living with a partner or to becoming a parent or a grandparent and then to retirement and perhaps the death of a spouse. The model views that some people find it more difficult than others to adapt to life’s changes and to cope effectively with the stressors that change can bring. When life results in a stressful situation or there is an accumulation of multiple stressors, people who have been unable to develop and establish adequate coping skills and coping resources are at the highest risk of developing a mental illness.

Social and interpersonal models

Social/interpersonal models draw attention to the impact of factors within a person’s social environment on mental wellbeing. The basic concept is that negative social factors such as low status, low levels of support, isolation and poverty contribute to and increase the risk of developing a mental illness such as depression (Elder et al 2009).

Interpersonal models encompass the premise that internal conflict within one’s personality and particular behaviours may be derived from unresolved conflicts within personal relationships, sometimes during early life experiences. This model also encompasses the premise that an individual’s wellbeing is dependent on the amount of stress experienced and the effectiveness of personal coping strategies in dealing with that stress. Karen Horney (1885–1952), Harry Stack Sullivan (1892–1949) and Hildegard Peplau (1909–1999), a nurse theorist, are some of the important theorists who have conducted research related to social and interpersonal factors and mental health.

Cognitive behaviour models

Cognitive behaviour models stem from the assumption that behavioural responses are learned. Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) developed the understanding of learned behaviours when he found that when a bell was repeatedly rung each time dogs were given food the dogs began to salivate just at the sound of the bell. This conditioned reflex was termed classic conditioning and is acknowledged as a form of learning that applies to humans, learning in which a previously neutral stimulus comes to elicit a given response through association. For example, behavioural theorists would suggest that children who observe parents responding to every minor stress with anxiety would soon learn the response and would develop a similar pattern of behaviour (Elder et al 2009). According to the behavioural model, this early learning experience would be considered a significant factor in the cause of an anxiety disorder and limited constructive coping strategies in later life.

BF Skinner (1904–1990) added to behavioural theory by introducing the concept of operant conditioning. Operant conditioning refers to the use of reinforcers to motivate the repetition of particular behaviours. The use of positive reinforcement (the continual rewarding of desired behaviours) forms the basis of behaviour modification therapy used to help motivate clients to change undesirable behaviours. It has been effective for clients with phobias, alcohol addiction and a variety of other conditions (Elder et al 2009).

Aaron Beck was one of the early founders of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), now a common and often very successful form of psychological treatment. It is based on the view that dysfunctional behaviour is linked to dysfunctional thinking, and that thinking processes are shaped by underlying beliefs. For example, the client with depression believes, ‘I am no good at anything, I’m worthless, and nobody likes me’. Cognitive behaviour therapy is based on helping clients recognise, challenge and change dysfunctional thinking. Beck’s work has primarily focused on helping people with depression but he has expanded the use of CBT to include working with people who have complex disorders such as borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia, and there are distinct signs of success (Elder et al 2009).

Mental health, like physical health, is clearly affected by a multitude of factors. Consequently, mental health nurses and psychiatrists are concerned with all the aspects of people’s lives that distinguish them as human beings. The mental health nurse uses knowledge from the psychosocial and biophysical sciences, and theories of stress vulnerability, personality and behaviour, to develop a framework on which to base the art of nursing. The mental health nurse is an integral part of the interdisciplinary team required to meet the needs of clients who have a mental illness.

THE PROVISION OF CARE

The multidisciplinary team

Many people may be involved in assisting a person who is experiencing a disruption or potential disruption to their mental health. Mental healthcare commonly employs an interdisciplinary team approach to care management. The client’s care, according to individual needs, is planned and implemented by a team composed of mental health nurses, psychiatric social workers, counsellors, clinical psychologists, general or specialist medical officers (depending on the client’s physical status) and pharmacists. Additional team members may be required and, depending on individual needs, these may include: a dietitian; an occupational therapist; a recreational, art, music or dance therapist; complementary healthcare therapist; and a chaplain or other spiritual support person. (See Clinical Interest Box 37.7.)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 37.7 Some members of the healthcare team

• The psychiatrist: a physician whose specialty is mental disorders and who is responsible for diagnosis and treatment. A psychiatrist has the legal power to prescribe and to write treatment orders and, as such, is often the team leader

• The mental health nurse: a nurse with experience and expertise in clinical psychiatry, who promotes a holistic approach to care

• The clinical psychologist: a psychologist who has undertaken specialised education in the area of mental health and whose function includes applying and interpreting psychological tests and the implementation of specific therapies such as behaviour modification programs and sexual, marital or family therapy

• The psychiatric social worker: a social worker in the field of mental health, whose function includes assisting the client to prepare a support system that will help maintain their mental health on discharge into the community from an inpatient facility. A social worker may liaise with employers, contacts in day-treatment centres and those providing training and educational programs. The social worker may also assist the client to locate and access sources of financial aid and accommodation

• Occupational, recreational, art, music and dance therapists: according to their specialist areas of expertise, these various therapists assist clients to gain skills that assist them to cope more effectively, to gain or retain employment, to use leisure time in a way that promotes their mental wellbeing and to express their emotions in healthy ways

(Stuart & Laraia 2001; Varcarolis et al 2010)

It should never be forgotten that the most important member of the team is the client, and often clients know what they need to promote their own recovery. Some clients have reflected on the times when they have been at their most vulnerable. For example, some clients who have experienced admissions to acute-care settings have identified that what they need most at times of severe mental distress is somewhere they can feel safe and supported, somewhere they can relax and calm down and someone to be with them who will listen and really hear them (Watkins 2002). While the client may feel the need for medication, it is not appropriate or helpful to implement other therapeutic interventions, such as group therapy, recreational therapy or family therapy, until the client is feeling less distressed and can collaborate in decisions about what sort of interventions will be most helpful. Skilled helping involves actively listening to the client and working collaboratively with the client to achieve a process of recovery. (See Ch 6 for information concerning active listening as a therapeutic measure.) The therapeutic process involves health professionals, including nurses, as facilitators who use their knowledge to help the client become more resourceful and self-reliant. This helping relationship needs to be a participative but never a directive process (Watkins 2002). The model of helping relationships established by Carl Rogers (1961) and the model of skilled helping established by Gerard Egan (1994) are client-centred models of caring on which mental health nurses can reliably base their therapeutic interactions with clients.

Responsibilities of the mental health nurse

Mental health nursing may be described as an interpersonal process in which the nurse uses the presence of self, interpersonal communication skills and a knowledge of physiology, psychology and sociology to help clients in mental distress. A combined understanding of biological processes and psychodynamic processes is essential for the mental health nurse because many people with mental illness have a concurrent physical problem, and the two are often interconnected (Elder et al 2009).

Mental health nurses are very involved in psychiatric inpatient services and in community mental health services. They play a major role in education and health promotion, as well as in the provision of continuing care and counselling for people with mental health problems. For some experienced mental health nurses the role may include conducting specific psychological therapies such as cognitive behaviour therapy, solution focused therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy.

Nursing care aims to help clients cope with the experience of mental illness, prevent relapse and to promote a return to mental health through a successful rehabilitation program. The primary aims of mental health nursing (Watkins 2002) are to help individual clients to:

• Identify and clarify their needs and problems

• Create a better future for themselves (e.g. empower clients by developing self-help strategies)

• Create strategies to enable them to move forward (e.g. clients can become stuck in a particular way of responding to situations).

Rehabilitation is important for people who have been discharged from a psychiatric ward or unit. Some people need minimal support but others represent a population of chronically ill clients who return to hospital periodically over many years and require support in several different areas of their lives. The community mental health nurse and other members of the community mental health team may be involved in:

• Individual and family therapy

• Medical care for concurrent physical problems

• Vocational training and support (Shives 2008).

Recovery and mental illness

The concept of recovery has been apparent for the last few decades and is manifest mainly in policy at various levels such as health services management, practitioners and consumer/survivors of healthcare services (Edward et al 2011). Many consumer/survivors, some of whom were mental health professionals, began to speak about their experiences of mental illness and their individual journey of recovery which led to the development of the consumer-recovery movement (Deegan 1988; Lovejoy 1984). In the United States the consumer-recovery movement was boosted by William Anthony, a rehabilitation expert who challenged the state health system on their vision of recovery that was based on a belief that mental illness was essentially a ‘chronic’ condition with very little hope of getting back to full health (Anthony 2000). According to Anthony (2000), mental health services need to be grounded in the idea that people can recover from mental illness, and that the construction of the service delivery system must be based on this knowledge. From that period of time most western countries adopted an approach to recovery that is based on practices and principles of autonomy and self-determination.

Contemporary mental health nursing care is now based on the recovery principles that refer to the person’s rights to self-determination and inclusion in community life regardless of their diagnosis of mental illness. Recovery principles are based on an approach that hope is central to recovery and that shifting the focus from symptom management and diagnostic labels to one which keeps people well gives their lives value and meaning. Personal and social recovery is the primary focus of contemporary mental health nursing care.

Facilitating development of constructive coping mechanisms

The nurse’s role in stress and stress management has some specific points that need to be highlighted here. To recognise and deal with stress, individuals need to be provided with information about, and helped to recognise:

• Issues and events related to health and illness, and the importance of adhering to sound health practices (e.g. adequate nutrition, sleep, exercise and relaxation) as a way of promoting mental wellbeing

• The dimensions of potential stressors, possible outcomes and the client’s own established positive and negative coping mechanisms and coping resources

• Their existing strengths and develop and maximise their abilities in problem solving, tolerating stress and dealing effectively with interpersonal relationships

• Where and how to gain access to additional coping resources (e.g. vocational training, support groups and counselling).

There is a wide variety of activities that clients may find helpful in promoting coping, but there is no one right or best activity. What works for one person may not work for another. Nurses have a responsibility to provide clients with information and options, but only the client can know what feels appropriate, so the choice of what activities to attempt or to become involved with should ultimately rest with the client. Clinical Interest Box 37.8 provides examples of constructive coping strategies, coping resources and destructive coping mechanisms.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 37.8 Examples of constructive coping strategies, coping resources and destructive coping mechanisms

Coping resources

Destructive coping mechanisms

• Always being submissive to others and so failing to get own needs met

• Excessive use of alcohol and/or other drugs or overeating (seeking comfort in substances)

• Promiscuity (seeking love and acceptance in a way that does not improve self-esteem)

• Overuse of defence mechanisms to cope with unacceptable or ambivalent feelings. Defence mechanisms commonly used in a maladaptive manner (Stuart & Laraia 2001) include:

(Beyond Blue, www.beyondblue.org.au); (Stuart & Laraia 2001; Varcarolis et al 2010)

The nurse’s role in educating the public and reducing stigma

One particularly important facet of the community mental health nurse’s role is educating the public about mental illness to reduce the stigma that for many mentally ill people is the biggest hurdle to overcome (Watkins 2002). There is a general lack of knowledge in the community about what constitutes mental illness and about the prognoses of mental disorders; this ensures that mental illnesses are often surrounded by mystery, misinformation and stigma (Weir & Oei 1996). Despite positive interventions in recent years, people suffering from mental illness remain among the most stigmatised, discriminated against, marginalised, disadvantaged and vulnerable members of society (Johnstone 2001) (see Clinical Scenario Box 37.1).

Clinical Scenario Box 37.1

The stigma of mental illness

John was diagnosed with schizophrenia 2 years ago. Getting a diagnosis was such a relief, because then we knew what had caused such a big change in him. The nurses taught us about the illness and now, because we know what to look for, we pick up the early warning signs. He knows where to get help and most of the time he avoids a relapse.

John’s pretty much in control of his illness now, but the thing that’s upset him and us most is the way some people have treated him. He lost his part-time job in the supermarket and even one of his lecturers at college told him he should consider leaving his engineering course because of it. Even my own sister won’t have him babysit his young cousins anymore. John now feels it is not safe to tell anyone about it. How do you think that makes him feel? If it was diabetes that made him ill I wonder if people would have reacted the same.

Several myths about mental illness create fear of those affected and this fear serves to increase stigmatising behaviours and attitudes. For example, there is a widely held perception that people with mental illness are often out of control, unpredictable and may pose a threat. The truth is that most people with mental illness do not behave in this way; however, severe mental distress is often highlighted in the media, and this links images of dangerous behaviour with mental illness in the minds of the public (Watkins 2002). In addition, single, isolated and often very minor criminal acts committed by mentally ill people tend to be sensationalised by the media, contributing to negative stereotypes (Jewell & Posner 1996). Overall, violence in society associated with mental illness is not significant (Elder et al 2009). The Sane Australia Stigmawatch website monitors misuse, misrepresentation or inappropriate references to mental illness in the media (Elder et al 2009).

The lack of accurate knowledge about mental illness that leads to fear, mistrust and sometimes violence against people living with mental illness and their families can also serve to:

• Lower the morale and self-esteem of people living with mental illness

• Prevent people with mental illness from admitting the problem and seeking professional help

• Prevent people with mental illness from gaining paid employment

• Limit the participation of people with mental illness in community activities and force them into a reclusive lifestyle

• Cause families and friends to turn their backs on the mentally ill person when support is most needed.

The picture is not always as dismal as this. Many mental healthcare users are themselves excellent ambassadors for people with mental illness. By calling themselves consumers or clients they have empowered themselves to become advocates for other people experiencing mental health disorders. Mental healthcare users or consumers now have a vital role to play in participating and planning the delivery of mental health services (Happell & Roper 2003). Consumer advocacy groups now exist in every state and territory of Australia and in New Zealand to promote participation of consumers in planning, implementation and evaluation of mental health services. Accordingly, many consumers live and work within a local community, use the same facilities (e.g. shops, library, cinema, sports centres) as everyone else, are accepted by the people within the community and experience no harassment and attract no hostility from the local residents (Markowitz 2007). All nurses can play a part in highlighting and reducing stigma by:

• Acknowledging the person by using respectful language; for example, never referring to someone as a manic depressive, but rather referring to them as a person with a bipolar disorder

• Discouraging the use of disrespectful language; for example, terms such as schizo, lunatic, crazy, nut case or barmy. The nurse can advocate for people with mental illness by alerting someone to the fact that they are expressing a stigmatising attitude. Many people do this automatically without realising the hurt they are causing and the negative impact on the person with the illness or their family members

• Emphasising the person’s abilities rather than their limitations

• Avoiding representing a successful person with a mental illness as superhuman.

In part it is the way people with mental disturbance were treated in the past that influences current perceptions of mental illness and the associated stigma. The next section provides a brief overview of historical perspectives relevant to understanding societal attitudes today.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES AND MENTAL HEALTHCARE

In the past, when emotions, thoughts or actions were deemed to be abnormal, the terms madness and insanity were linked to those affected. Reasons for the perceived abnormalities were once attributed to a variety of factors such as the influences of magic, witchcraft, possession by the devil or evil spirits, loss of the soul or punishment by the gods. Healing methods included exorcism, magical ritual and incantation (Videbeck 2001). Later it was proposed that an imbalance of ‘body humours’ was responsible—body humours being blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm—and such imbalances were corrected by bloodletting. During the medieval period, beliefs returned again to those connected with magic and demonology but also included beliefs that the moon influenced madness (lunacy). Some of those perceived as mad or lunatics were flogged, tortured and starved and those whose illness resulted in violent behaviour were shackled in prisons or put out to sea as a means of ridding them from society. Fear and lack of knowledge resulted in significant cruelty.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, those with behaviours which were not manageable, who were misunderstood or were simply not acceptable in society were placed in custodial care inside large public mental hospitals or asylums. It can only be imagined how being confined and isolated inside large institutions might have caused feelings of abandonment and rejection. During this period doctors classified the symptoms of mental illness but had limited understanding of the sources of mental anguish (Wilson & Kneisl 1996).

Increased understanding of mental distress was promoted by the psychological, psychosocial and interpersonal theories to explain behaviour espoused by theorists such as Freud, Erikson and Stack Sullivan. The introduction of psychotropic drugs, such as chlorpromazine (Largactil) in the 1950s, helped staff members manage large numbers of clients with challenging behaviours, who were often accommodated in crowded conditions in the large institutions. In the 1990s (the time known as the decade of the brain) biological, scientific and technological concepts combined to expand on earlier understandings of mental illness. As a result, advanced brain-imaging techniques now allow direct viewing of the structure and function of the living brain while it is functioning (Wilson & Kneisl 1996).

In the latter part of the 20th century the negative impact of institutionalisation for people with mental illness was recognised. This recognition was in part the stimulus that shifted public policy to one of deinstitutionalisation and community-based care for people with mental illness. The push towards community-based mental health services also came from the human rights movement and the philosophy of normalisation for people with disabilities of all kinds. (Ch 39 explains more about the principles of normalisation and people with disabilities.) The discovery of psychotropic drugs in the 1950s also contributed to the current predominance of care in the community because these agents helped to modify challenging behaviours (Jewell & Posner 1996).

Mental healthcare today

Mainstreaming of mental healthcare has resulted in the provision of psychiatric care to consumers in general hospitals with an inpatient psychiatric unit, hostels and other residential care facilities and sometimes in forensic centres for the mentally impaired who have committed crimes. However, mental healthcare is primarily provided in the community and in Australia the community setting has become the place where most consumers receive their care.

Nurses may meet with clients in a variety of community settings, including:

Current healthcare policy promotes not admitting people to a treatment centre unless essential, and, when it is necessary for clients to be admitted to treatment centres, they are discharged back into the community as early as possible. Ideally, community-based mental health services provide appropriate networks of supports and resources for those who need it. The aim of service providers is to ensure that there are caring interventions aptly suited to assist each person to rehabilitate successfully and to cope well in society. The policy of community-based care has enabled many of those who once lived in psychiatric institutions to resettle successfully in the community and to be well supported. It is important to remember that the environment in which the consumer is seen affects the therapeutic relationship. In community settings the mental health nurse enters the home of the consumer as a guest, engaging with the consumer on a more relational and contextual basis.

Unfortunately, however, there are other instances in which the deinstitutionalisation process has not been supported with adequate community care. The result of this is that some people who experience mental ill-health have merely been relocated to substandard boarding houses or other semi-institutionalised accommodation, or face homelessness (Grigg et al 2004).

While there are still many problems for mentally ill people and health professionals to contend with and resolve, there is now more cause for optimism in relation to mental illness than in the past. Success rates for the treatment of many common mental disorders such as bipolar disorder, major depression and schizophrenia now equal or exceed the success rates for many other medical disorders (Goldberg 2007).

While this chapter does not aim to inform the nurse about the range of treatments available to assist clients with specific disorders, the next section provides a summary of possible nursing responses to some common emotional and behavioural problems that challenge clients with mental illness. The terminology used in mental healthcare, some of which is contained in the next section, is extensive and different from terms used in other areas of nursing. Some of the more common terminology is defined in Table 37.2.

Table 37.2 Terms associated with mental illness

| Addiction | Physical or emotional dependence, or both, on a substance, such as alcohol or other drugs |

| Affect | Current, observable state of emotion, feeling or mood such as sadness, anger or elation |

| Aggression | Forceful behaviour that may be physical or verbal, as well as subtle manipulation |

| Akathisia | A condition of excessive restlessness that causes a person to move about constantly, fdget or pace. This can be a side effect of certain medications used in psychiatry |

| Anhedonia | Reduced or complete inability to feel pleasure from activities previously enjoyed |

| Amnesia | Loss of memory of events for a period of time that may range from a few hours to many years |

| Anxiety | A feeling of apprehension, dread or unexplained discomfort, associated with a sense of helplessness, arising from internal conflict |

| Apathy | Lack of feeling, emotion, concern or interest |

| Asylum | A place of safety or sanctuary; a refuge from the stresses of life. Historically the term asylum was associated with institutions that provided custodial care for people with a mental illness. Unfortunately, they were often associated not with the real meaning of asylum but with mistreatment and cruelty |

| Autism | Preoccupation with the self and inner experiences; a process of introspective thinking that is often rich in fantasy |

| Behaviour | Any human activity, either physical or mental. Some behaviour can be observed while other behaviour can only be inferred |

| Behaviour modifcation | A method of changing or controlling behaviour through the application of techniques based on the principles of classical conditioning |

| Bipolar disorder | A type of mood disorder that causes alternating periods of low and high moods; a combination of depression and mania |

| Body image | The conscious and unconscious attitudes a person has towards their body (e.g. feelings about size, function and appearance) |

| Catatonia | A state characterised by muscular rigidity and immobility (stuporose type) and which, at times, is interrupted by episodes of extreme agitation (excited type) and is usually associated with schizophrenia |

| Compensation | Process by which a person makes up for a defciency in their self-image by strongly emphasising some feature of themself that they regard as an asset |

| Compulsion | An uncontrollable persistent urge to perform an act repetitively in an attempt to relieve anxiety. Compulsive behaviour often accompanies obsessions and may be directly linked to them |

| Confabulation | The fabrication of experiences or situations recounted in a plausible way to fill in and cover gaps in the memory. Used most often as a defence mechanism and most commonly by people with head injuries, dementia, amnesic disorders or alcoholism, especially those with Korsakoff’s syndrome |

| Confusion | A cluster of abnormalities constituting disturbances of judgment, orientation, memory, affect and cognition |

| Coping mechanisms | Any effort directed towards stress management. They can be unconscious (defence) mechanisms that protect the individual against anxiety, or conscious attempts to solve a problem that is creating stress |

| Deinstitutionalisation | A shift in the location of treatment from large public hospitals to community settings |

| Delusion | A fxed false belief resistant to modifcation. A delusion of grandeur is a false belief that one has great prestige, power or money, which may be manifested in the belief that the individual is a famous person. A delusion of persecution is an individual’s belief that they are in danger, being harassed, are under investigation or are at the mercy of some powerful force. A somatic delusion is a belief that one’s body is changing and responding in an unusual way |

| Dementia | A mental disorder characterised by a gradual onset of usually irreversible cognitive impairments |

| Depression | A mood state that may be mild or short lived or more severe and persistent. The latter, a mood disorder, is characterised by extreme sadness, feelings of hopelessness, low self-worth and little or no conviction that things can ever improve |

| Disorientation | Lack of awareness of the correct time, place or person |

| Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) | A therapeutic procedure in which an electric current is briefly applied to the brain to produce a seizure. This is used in treatment of severe symptoms that do not respond to other measures, most commonly used in the treatment of severe depression |

| Hallucination | A sensory experience that is not the result of an external stimulus; may be visual, auditory, tactile, gustatory or olfactory |

| Hyperactive | Excessively or unusually active |

| Illusion | Misperceptions and misinterpretations of real external stimuli; may be visual or auditory or, less commonly, olfactory or tactile |

| Labile | Subject to frequent or unpredictable changes: the term is commonly used with reference to emotions |

| Mania | A mood characterised by an intense feeling of elation or irritability, often accompanied by increased activity, rapid speech and poor judgment |

| Mood disorder | A group of disorders in which the predominant feature is disturbance in mood |

| Nervous breakdown | A non-medical term sometimes used by the public to describe an episode of overwhelming distress or depression |

| Obsession | A persistent thought, idea or impulse that cannot be eliminated from consciousness by logical effort |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | An anxiety disorder characterised by intense, unwanted and distressing recurrent thoughts (obsessions) and repeated behaviours (compulsions) that are beyond the affected person’s ability to control |

| Panic attack | A period of sudden intense anxiety, often associated with feelings of impending disaster and accompanied by strong physiological symptoms, including shortness of breath, pounding heart or palpitations and dizziness |

| Paranoia | A serious personality distortion in which the person is markedly suspicious and mistrusting of others and may be convinced that they wish to harm them |

| Phobia | An intense fear of some situation, person or object, so that the danger is magnifed out of proportion and may result in a panic attack |

| Psychosis | A state in which a person’s mental capacity to recognise reality, communicate and relate to others is impaired. Delusions and hallucinations are often present |

| Psychotic | A person who is psychotic experiences delusions and hallucinations that cause disorganised thinking, unusual behaviours and a loss of touch with reality |

| Schizophrenia | A complex condition caused by brain dysfunction that results in hallucinations and delusions, distorted thinking and other disturbances |

| Suicidal ideation | Thoughts of suicide with an intention to end one’s life |

| Tardive dyskinesia | A side effect of some antipsychotic medications that manifests with a variety of involuntary muscle movements including those that affect the face, jaw and tongue, the trunk and the extremities of the body. The involuntary movements are irreversible. They are also referred to as extrapyramidal side effects |

CARE OF CLIENTS WITH SPECIFIC EMOTIONAL OR BEHAVIOURAL CHALLENGES

Here we address some of the more common mental states that clients being cared for in non-psychiatric hospital settings may experience. Information is provided on caring for a person who is anxious, depressed, aggressive, displaying self-destructive behaviour, hyperactive, confused or disoriented.

The client experiencing anxiety

Anxiety is an internal feeling usually experienced as an unpleasant or uncomfortable emotion and which is frequently associated with conflicts and frustrations. While a certain mild degree of anxiety can be beneficial when it stimulates motivation and energy, severe anxiety can be devastating and is the basis of many mental health disorders. Anxiety differs from fear in that anxiety attacks the person at a deeper level than fear, and the source of the anxiety may be unknown. Sometimes, in extreme anxiety, a person may experience panic attacks that result in markedly disturbed behaviour. The person may be unable to process what is happening in the environment and may lose touch with reality. During a panic attack behaviour may be erratic, uncoordinated and impulsive. There are three different forms of panic attack: ‘out of the blue’ attacks, which are not brought on by a trigger; situation-bound attacks which are brought on by exposure to a trigger; and situation-predisposed attacks that are comparable to situation-bound but which do not happen every time the person is exposed to a trigger.

Anxiety invades the very centre of a person’s being. Severe anxiety is profound and persistent and can erode and destroy a person’s sense of self-esteem and self-worth that contribute to a sense of being fully human (Varcarolis et al 2010).

Anxiety is experienced in a wide variety of situations and is generally the result of a threat to a person’s self-esteem or physical integrity. Threats to self-esteem include factors such as interpersonal difficulties, change in job status, social or cultural group pressures, a change in role or confusion over one’s identity. Threats to physical integrity include factors such as decreased ability to perform the activities of daily living, for example, as a result of injury or illness, or lack of basic requirements such as food, shelter and clothing. Mild and moderate levels of anxiety can alert the person to the fact that something is wrong and may be the stimulus to take appropriate action. Severe levels of anxiety interfere with problem-solving abilities, so that those affected have difficulty finding effective solutions to problems. For example, someone who experiences panic attacks may use unproductive relief behaviours to avoid the attacks from occurring, such as refraining from leaving the house to avoid the risk of a panic attack when driving the car, at work or at the supermarket. Unproductive relief behaviours perpetuate the cycle of anxiety (Varcarolis et al 2010).

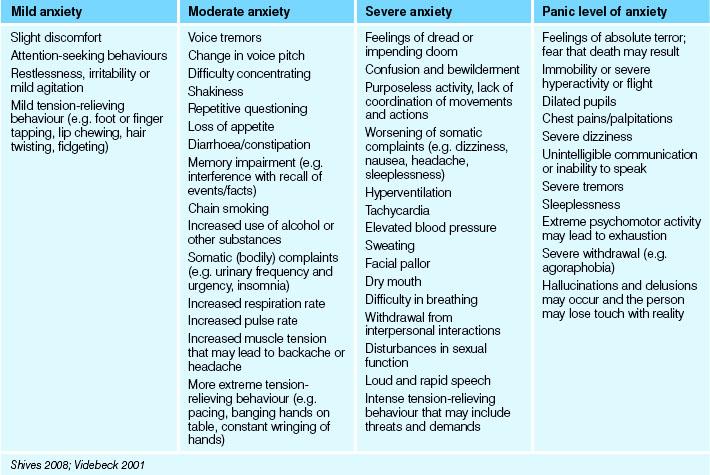

Whether the source is known or unrecognised, anxiety can produce physiological responses, behavioural changes and emotional reactions. The type and extent of response depends on the level of anxiety experienced. Table 37.3 lists some physiological and other responses to different levels of anxiety. Emotional reactions are usually apparent in the person’s descriptions of their experience. For example, they may state that they feel apprehensive, irritable, angry, depressed, helpless, on edge, unable to concentrate or remember things or they may feel detached from events and the environment. The person may experience angry outbursts or a tendency to cry frequently.

Specific treatment and care of a person experiencing anxiety depends on the level of anxiety experienced and the effects on the individual, but generally interventions are directed towards reducing intense anxiety to a more manageable level and helping the person to develop self-help strategies to prevent overwhelming anxiety. Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), for example, helps clients develop strategies for controlling their anxiety and reducing the incidence of panic attacks. Minor tranquillisers such as diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan) and clorazepate (Tranxene) are sometimes prescribed to suppress the client’s feelings of anxiety but, as medications do not cure the condition and there are problems with dependence, long-term use is not advocated (Healy 2002).

• Establishing and maintaining a trusting relationship

• Attempting to identify the cause (stressors) of the anxiety and encouraging the client to take effective action

• Facilitating open and honest communication about the client’s anxiety and/or problems

• Identifying existing coping mechanisms and coping resources

• Discussing with the client ways of resolving conflicts

• Providing information about, and teaching, constructive coping strategies that can help to manage stress.

The most common coping mechanisms taught and encouraged are:

• Skills for establishing and maintaining relationships

• Community living skills (Schwecke 2003).

Care during a panic attack