CHAPTER 6 Communication

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to

• Identify the components of the communication process

• State the factors that influence effective communication

• Identify the factors that act as barriers to effective communication

• Identify ways to overcome barriers to communication

• State how culture impacts on communication

• Demonstrate techniques for monitoring how culture impacts on their communication

• Identify and implement communication processes that facilitate patient safety and quality care

Communication is an interactive process involving the verbal or non-verbal transference of information between people. Effective communication is essential to the provision of safe, quality care in nursing and vital to the development of a therapeutic relationship between nurse and client. This chapter has a particular emphasis on the crucial communication issues affecting the delivery of safe healthcare to clients and the importance of health team communication in relation to patient safety.

Some nurses rush into my room and do what they have to do then leave. They avoid looking at me so I don’t feel I can ask them anything. But one of the nurses she looks at me and always asks ‘Is there anything I can do for you?’ This makes me feel that I can ask her to help me; the others make me feel like I am a bother.

Communication has been identified as an essential component for quality healthcare and patient safety (The Joint Commission 2010). Effective communication involves the ability to interact with people at a variety of levels and in a range of situations.

Effective communication in the health care environment requires knowledge, skill and empathy. It encompasses knowing when to speak, what to say and how to say it, as well as having the confidence and ability to check that the message has been correctly received.

Effective communication is important in all areas of everyday life; the quality of relationships between people depends on it (Anderson 2009). With nurses accounting for about 45% of the health workforce (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2010) the need for nurses to be able to communicate effectively with everyone in the healthcare environment, and with clients, becomes critical (Berman et al 2012). The ability of nurses to communicate effectively is an essential factor in ensuring the client’s experience in a healthcare encounter is of the highest value and causes no inadvertent harm (Enlow et al 2010). Nurses need to be skilful in what they do for clients but at the same time they need to communicate with them in ways that are supportive and helpful, and promote feelings of trust (Institute of Medicine 2011).

All these aspects become of the utmost importance when the literature identifies that 10% of all clients admitted to healthcare facilities will suffer an adverse event (Richardson & Storr 2010). The Institute of Medicine (IOM), in their groundbreaking report, To err is human (Kohn et al 2000), claimed that 40–50% of medical errors are directly attributable to communication issues, and these statistics have been frequently re-quoted in the literature over the last decade (Queensland Health 2012; Schuster et al 2010). The IOM report was the catalyst for a new focus on patient safety in the last decade and although it is difficult to prove causation, an emerging body of literature suggests that quality of care depends to a large degree on nurses (Institute of Medicine 2011).

The focus of this chapter is on nurse interactions with clients and other members of the healthcare team. Utilising the skills involved in effective communication will enhance relationships between clients and health professionals, leading to improved quality of care and client safety.

COMPONENTS OF THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

All communication is a two-way process in which messages are conveyed by verbal and/or non-verbal means by one person, and received by another (Berman et al 2012). All behaviour conveys some message and is therefore a form of communication. For example, even a client refusing to speak or acknowledge the presence of a nurse conveys a message that the nurse will attempt to interpret (decode). Non-verbal communication includes the messages sent by facial expression, gestures, body posture and appearance, and those that are written (Pullen 2007).

Communication is an ongoing dynamic series of events in which meaning is generated and transmitted. Communication occurs when a person responds to a message and assigns meaning to it. Meanings are subconscious thoughts that are created to develop a sense of understanding (Schuster 2010). During interactions people respond to messages they receive and create meanings for those messages. If the intended meaning of a message is misunderstood by the recipient, communication has not occurred effectively (The Joint Commission 2010; Maguire & Pitceathly 2002).

Communication takes place at many different levels and to ensure high quality and safe delivery of healthcare nurses need competence in all of them. Communication may occur at the interpersonal, small-group, organisational, public and mass communication levels and each will be expanded on later in this chapter (Ellis 2009).

LEVELS OF COMMUNICATION

The most basic level at which communication occurs is the intrapersonal level.

Intrapersonal communication is a process that occurs within individuals. For example, if a person looks outside and sees that it is raining and thinks ‘I had better bring the washing in’, the person is communicating intrapersonally. Interpersonal communication is communication that occurs between two people, whereas small group communication involves three or more persons, such as during clinical handover on a hospital ward. Organisational communication refers to a system of disseminating or transferring information within an organisation. Public communication involves communication with large groups of people; for example, when a speaker addresses an audience. Mass communication occurs when a small group of people send messages to a large, anonymous audience through the use of some specialised media, such as film or newspapers. As at some stage nurses will engage in most of these levels of communication they are required to have a high level of communication skills (Bach & Grant 2009).

ELEMENTS OF THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

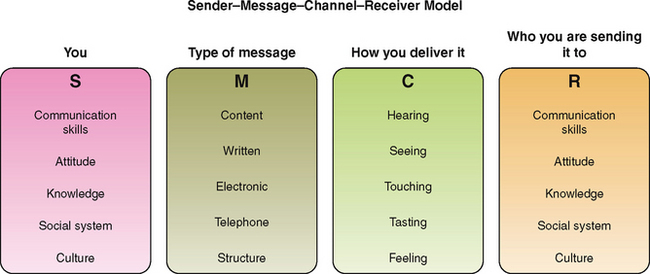

Communication is a multidimensional and complex process in which ideas, thoughts, values, knowledge or feelings are shared and interpreted (The Joint Commission 2010). During the process people simultaneously send and receive numerous messages at many different levels. To simplify understanding of this complex process, a mathematician working in communications on the 1940s developed a linear model of communication known as the SMCR model (Schuster 2010). Figure 6.1 is an example of one such model. It depicts the basic elements of communication and shows that communication is a linear process between sender and receiver. The process of communication involves:

This model depicts the sender as the individual who initiates the communication. The receiver is the person to whom the message is transmitted. The role of sender and receiver may alternate between participants at any time during the period messages are being transmitted.

The message is the information that is transmitted by the sender, and the channel is the means by which the message is conveyed (Bach & Grant 2009).

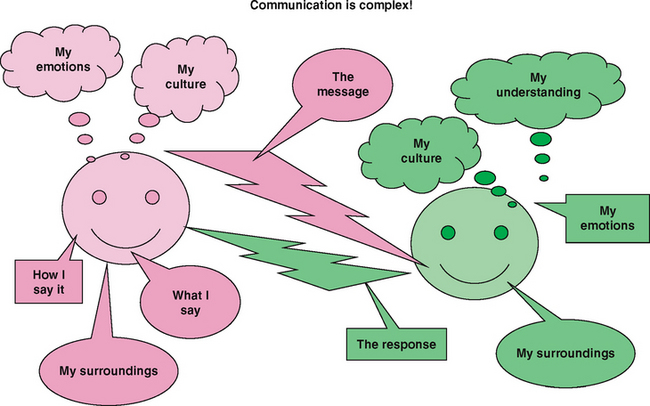

Communication between two human beings is far more complex than this in reality and is influenced by many and varied external and internal processes (Thomas et al 2009). Communication between two people may comprise both verbal and non-verbal information for example, through the visual, auditory, olfactory or tactile routes. The sender’s facial expressions and body gestures visually convey a message to the receiver; for example, a facial grimace or tense body posture sends a visual message to the nurse that the client may be in pain. The spoken word is conveyed via the auditory channel and touching a person while communicating uses the tactile channel. A nurse can convey a message of caring and compassion to a distressed client by a simple touch of the hand. The olfactory route is particularly important in nursing. Distinct odours can indicate a variety of conditions, including incontinence, the onset of a urinary tract or other infection and sometimes more serious events such as a smell of acetone on a client’s breath which can indicate a serious lack of insulin in the body (diabetic ketoacidosis).

Feedback helps the sender recognise whether the meaning of the message conveyed has been perceived as intended. The receiver’s verbal and non-verbal responses convey feedback to the sender to reveal the receiver’s understanding of the message. Feedback helps to clarify communication as it guides people in adjusting the messages they send to one another. Effective communicators continuously seek feedback from the people with whom they are communicating, to determine whether the information they are transmitting is being received and understood as intended (that there are no misinterpretations of the meaning of the messages) (Schuster 2010).

When communication occurs and information is transmitted from one person to another, two processes must take place: encoding and decoding. Encoding refers to the cognitive processes that occur in the mind of the person who sends the message. These thoughts must be translated into a code, such as verbal language, to be transmitted to the person who is to receive the message. Decoding refers to the cognitive processes used by the receiver of the message to make sense of what is seen or heard. Generally the sender and the receiver encode and decode messages in a cyclic pattern while communication is taking place (Schuster 2010).

Even during a simple act of interpersonal communication between two people, many factors influence how effectively messages are conveyed and understood (Berman et al 2012). These factors are frequently referred to as the variables; they relate to anything that influences or interferes with how the sender transmits a message, how the recipient perceives (interprets) the meaning of the message and the route or channel of communication

Variables are the factors that influence the quality and effectiveness of the communication. They include factors such as the setting in which communication takes place, the presence of distractions such as background noise, and the language, perceptions, values, knowledge, cultural background, role and emotions of each person taking part in the communication. Variables can enhance the effectiveness of communication between people but they are often barriers. A setting that does not provide adequate privacy may be a significant barrier when a nurse and client are attempting to communicate about the client’s personal concerns. Therefore in reality communication is more a transactional exchange as shown by Figure 6.2 which depicts the complexity of variables involved in the communication process (Bach & Grant 2009).

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

Perception

Perception is a process by which the meanings of messages are interpreted. The way messages are perceived is related to a combination of a person’s social and cultural influences, gender, educational background and knowledge, and past experiences (Schuster 2010). This complex mix of influences means that no two people are likely to perceive the same message in exactly the same way. Some of the strongest influences on the way messages are sent and their meanings perceived are the attitudes, values and beliefs that individuals hold (Van Der Molen & Gramsbergen-Hoogland 2005). Clinical Interest Box 6.1 demonstrates communication in process.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 6.1 The communication process in action

Mrs Ling has been in hospital for several days and is about to be discharged home. Before she is discharged, the nurse must make certain that she understands she has to attend an appointment with the medical officer in 2 weeks time. The nurse (the sender) thinks about the best way to pass on the information (the message), and decides (encodes) to write the time and date of the appointment on a card, in addition to telling Mrs Ling. Thus, both spoken and written words (auditory and visual channels) are used to transmit the message. Mrs Ling (receiver) listens to the nurse and looks at the appointment card. Because the words used are familiar to her, she is able to understand (decode) the information. She confirms she has understood the message by asking, ‘So I need to come back here and see the medical officer again at 11 o’clock on Tuesday 2nd October?’ (feedback to the nurse).

Attitudes, values and beliefs

Attitude is the way one person behaves towards another. A person’s attitude can be positive, or negative and unpleasant. An unpleasant attitude in the workplace makes other people feel uncomfortable and it is detrimental to the wellbeing of clients (Pullen 2007). Attitude can be influenced by what is happening in a person’s life. For example, a fight with a friend may create feelings of anger or distress. Such feelings can be reflected in a negative, even hostile, attitude towards others, which can change the way messages are transmitted and received. Nurses have a professional responsibility to maintain a positive attitude towards clients at all times, so every effort must be made to put personal concerns and feelings aside when communicating with clients, relatives and other health professionals in the workplace (Thomas et al 2009).

Attitude towards others is also related to the values and beliefs that a person holds about the ideas or practices of other people in society, and they are not always consciously recognised. For example, cultural values commonly lie outside conscious awareness and are often simply taken for granted as being the right values (Ellis 2009). It is natural for people’s values and beliefs to differ within and across social and cultural groups. Nurses will encounter many situations in which their own cultural values and beliefs differ from those of clients (see Ch 8). Tolerance and understanding of differences in views and cultural practices helps to facilitate therapeutic relationships between nurses and their clients (Pullen 2009). For example, a nurse who holds strong values and beliefs about no sex without marriage will need to demonstrate acceptance that personal views are not shared when caring for a pregnant, single, female client. If the nurse is unable to accept this and put personal views to one side, it will be difficult to communicate with the client in a therapeutic manner (Pullen 2009).

While a nurse’s personal values can create interference in therapeutic relationships if they are imposed on clients or used in judgment, they can also serve to enhance therapeutic effects. For example, a nurse who holds beliefs that all people have positive qualities and that every individual is a worthwhile person will find that such beliefs enhance the establishment of effective therapeutic relationships (Schuster 2010).

Differences in knowledge

When the level of knowledge between two people is different, communication can be difficult. For example, an individual’s level of knowledge may be so far above that of the person being spoken to that the meaning of the message may be lost entirely (Ellis 2009). The nurse must take care to express messages in words and phrases that will be understood. For example, a nurse who is familiar with nursing or medical language, especially jargon, may forget that a client may not be, and if words or phrases are used that are not part of the client’s vocabulary the message may be misinterpreted. The use of specific language that is familiar to members of a subculture or profession may confuse, frighten or alienate people who are not part of that subculture or profession. For example, not every male client will know what the nurse means when asked, ‘Do you need a bottle?’ The word bottle is nursing jargon used to describe a portable male urinal but it could easily be perceived as meaning something entirely different.

Past experiences

Past experiences can have a powerful effect on a person’s perceptions of the meaning of messages. For example, a client who has had a previous traumatic and painful experience in hospital may discount, distrust or disbelieve messages from the nurse that pain after surgery will be controlled. The nurse can help by talking with the client about the past experience and explaining fully every measure that will be implemented to ensure adequate pain relief (Schuster 2010).

Emotions

Emotions strongly influence how a person relates to other people, and the power of emotion in communication should not be underestimated (Schuster 2010). Nurses must also be aware that if they become too emotionally involved with the suffering experienced by a client, they may be unable to effectively meet that client’s needs. This aspect is one of the most difficult situations faced by nurses, as on the one hand nurses must become emotionally involved to assist clients, while on the other hand personal emotions cannot be allowed to adversely affect client care (Bach & Grant 2009). All nurses need to be aware of their emotions, and many find it helpful to talk with other experienced nurses about what they are feeling and experiencing.

It is also important to realise that, if people cultivate ‘emotional distance’ in an interpersonal interaction, they prevent any deep sharing of meaning and may even arouse animosity. For example, if a client feels that a nurse is treating them as an ‘interesting case’ or a ‘problem’ rather than as a person, they are likely to feel resentful, and therapeutic communication is not likely to occur.

It is not unusual for clients to be anxious or upset, and strong emotions interfere with the ability to absorb the information in messages such as those given by medical officers or nurses. There would be little point, for example, in a medical officer informing a client about treatment plans immediately after telling her that her breast biopsy revealed a malignant breast tumour. It would not be surprising if the client’s anxiety level increased to such an extent on hearing the diagnosis that it prevented her from absorbing any of the following information about the proposed treatment. The nurse can help in this situation by ensuring the information is repeated when the client is less anxious or distressed and by providing the information in written form for the client to absorb more effectively at a later time (Schuster 2010).

Relationships and roles

The style and type of communication that occurs between people depends on the quality and type of relationship that exists between them. Individuals communicate in ways that they perceive are appropriate to particular relationships and the roles they have within them. For example, a woman might communicate passively and non-assertively with the medical officer and the nurse but may be assertive with her husband, dominating with her children and bossy towards her colleagues at work (Timmins & McCabe 2005).

There are numerous types of interpersonal relationships, including those between friends, acquaintances, work colleagues, family members and partners. It is usually only when there is enough trust in a relationship that totally honest communication occurs, when ideas, judgments and emotions can be revealed without fear of reprisal, humiliation or rejection.

The nurse–client relationship is unique: trust in the nurse needs to develop quickly and trust is essential if the relationship is to be therapeutic. Clients in hospital may not say what they are thinking or feeling if there is a lack of trust in the nurse; often this means that the client has a fear of being judged. A therapeutic relationship means demonstrating unconditional acceptance of all clients, without judging (Bach & Grant 2009). The nurse accepts the client as a worthwhile person even if the client’s behaviour is challenging. As a nurse’s communication skills develop they become increasingly effective and therapeutic, but even when they have been learned and practised they may still be difficult to apply in some particularly challenging situations (Ellis 2009).

Environmental setting

Effective communication is more likely to occur if it takes place within a setting that is conducive to listening and concentrating (Ellis 2009). An area that is at a comfortable temperature, private and free from noise and other distractions is suitable, whereas an area where there is noise or a lack of comfort or privacy may create tension and confusion, making effective communication difficult. For example, background noise and the movements of other people in the environment may distract the listener, and even missing one or two vital words in a sentence can result in the meaning of a whole sentence being lost.

Ideally clients should be able to communicate with health professionals and other people in a private room, but this is sometimes difficult to achieve in busy healthcare facilities. Nurses should, whenever possible, talk with clients about personal issues in a private area. Clients can be accompanied to an interview room or even a quiet garden area to gain privacy. The very least that nurses can do if the client does not have a single room is to close the curtains surrounding the bed, speak quietly and avoid discussing personal details while visitors are in the area.

Two other factors, physical discomfort and pressure of time, are particularly important in nurse–client interactions because they can seriously interfere with the quality of therapeutic communication (Schuster 2010).

Physical discomfort

Communication is likely to be less effective if one or both participants are experiencing fatigue, pain or other physical discomfort (Ellis 2009). Like its emotional counterpart, physical discomfort can distract a person so that it is not possible to concentrate on what is being said. The nurse who is about to engage in a therapeutic dialogue with a client is advised to ensure that the client is free of pain, lying or sitting in a comfortable position and not needing to go to the toilet. It is also important to consider that some medications, including those administered for pain relief, can affect a client’s memory and the ability to concentrate or to think clearly.

Pressure of time

Because most people have many pressures on their time, the urge to speed up communication is increasing. Nurses need to overcome feelings of urgency to complete other tasks while communicating with clients (Bach & Grant 2009). This is not always easy, but even a few minutes of attentive listening can be very therapeutic for a client. Not all interactions with clients need to be lengthy but it does take time to explain, to listen, to reduce fears or anxieties and to assimilate facts. A client who is sensitive to the nurse’s need to get on with other things is unlikely to raise any issues of concern that need to be talked about. It is one of the major challenges in contemporary nursing practice to prioritise tasks and manage time so that the psychological as well as the physical needs of clients are met.

The route or channel of communication

The meaning in a message is at greater risk of being misconstrued if the channel of communication is not the most appropriate. For example, the oral route may not effectively communicate a long and involved message—it may be better transmitted in written form. It is sometimes difficult to relay messages of caring and concern with words; a gentle touch can be more eloquent than the spoken or written word in many situations (Ellis 2009).

Clinical Interest Box 6.2 provides examples of communicating effectively with clients.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 6.2 Guidelines to facilitate effective communication

• Be clear about the message to be conveyed, and how and why it will be conveyed

• Use the most appropriate medium (channel) for conveying a message

• Use language that is appropriate for the recipient’s level of intellectual understanding, emotional status and culture

• Choose the right timing and length of message for each occasion

• Use specific skills to gain and interpret feedback from the other person

• Use active listening skills to listen for what is said

• Use keen observation skills to determine what is not being said; for example, be aware of non-verbal communication

• Observe for clues and contradictions in the verbal and non-verbal messages from the other person

• Encourage and wait for questions, and answer them clearly and honestly

• Ask appropriate questions and actively listen to the response

• Be sensitive to individual differences in communication behaviour and, as far as possible, adjust the style of communicating to accommodate these differences

• Identify and minimise the barriers to effective communication.

FORMS OF COMMUNICATION

Communication is the process of sharing information and understanding, using verbal and non-verbal methods. Verbal communication involves the use of words and the way they are delivered. Words can be written or spoken (vocal). Non-verbal communication involves facial expressions, body posture and gestures, touch and the use of space (Ellis 2009).

Vocal communication

In addition to the words used, vocal communication involves the tone and pitch of the voice, the rate and volume of speech and the use of pauses, all of which provide information about the speaker’s message.

The words

Messages are only understood if the words used are familiar to the sender and the receiver. Nurses in Australia and New Zealand often care for clients for whom English is not a first language, and it may be necessary to get help from an interpreter (Crisp & Taylor 2009). Even within a cultural or sub-cultural group the meaning of many words can be ambiguous and one word can have two meanings in the same culture, so that remarks can easily be misunderstood. For example, a 5-year-old client was being prepared for a surgical operation and the nurse told him he would be going to the theatre in 2 hours time. Imagine his distress when he arrived in the operating room to have his tonsils removed, when he thought that he was being taken to see a film!

Sounds

In addition to words, sounds made by the voice can deliver very strong messages about a person. Sounds can convey pain (groans, moans), distress and sadness (crying, sobs), boredom or despair (sighs), excitement or fear (screeches and screams) or a range of other emotions. The meaning of a sound can easily be misinterpreted, as most sounds can express more than one emotion. A moan might not always express pain—it may be a moan of pleasure or disappointment. The nurse must always validate the meaning of a sound with the client; for example, the nurse might ask, ‘That sounds like you have pain, Mrs Jacobs. Do you have pain?’

Tone and pitch

The tone and pitch of the voice can have a powerful effect, sometimes more so than words (Schuster 2010). No matter what words are being said, a loud aggressive voice will send a strong message. A nurse’s tone and pitch of voice and the inflections used add meaning to words. Tone and pitch of voice can display anger, apathy, disgust, enthusiasm, excitement and other emotions. An individual can often determine more about another person from the way in which the words are spoken than from the actual words used. Loud, rapid, forcefully spoken words can intimidate and communicate aggression, a patronising tone can communicate condescension or contempt and expressionless speech can communicate lack of interest. A client and nurse can discern much about each other from their respective voices. Of particular importance, the tone and pitch of clients’ voices can convey messages about their emotional feelings and energy levels.

Rate and volume

Rate and volume of speech are best kept at a moderate level. Speaking too fast, too slowly or too loudly is not conducive to comfortable conversation, and messages may be lost or misinterpreted. Nurses frequently care for clients with hearing and cognitive impairments; such clients need to be consulted and assessed to determine the most successful rate and volume of speech to facilitate therapeutic communication.

The use of pauses

Pauses can provide time for clients to think about what they want to say, but pauses that are too long may seem awkward or uncomfortable (Pullen 2009). In normal conversation the style of communication that individuals use is generally not thought about consciously. When engaged in therapeutic relationships, nurses need to consciously evaluate the way they communicate and develop a conscious awareness of the tone, pitch, rate and volume at which they speak. Other basic aspects of vocal communication that are helpful to be aware of are the need to:

• Be brief: short pieces of information make understanding easier—the fewer words the less the risk of misinterpretation

• Keep the messages clear, simple and direct: complicated information leads to confusion and unnecessary words detract from clarity; for example, additions such as, ‘you know’, ‘OK’, ‘and that’ or ‘um’ are best avoided

• Enunciate words clearly: make messages clearly heard; mumbling makes them incoherent

• Use examples to clarify meaning: an example often makes it easier for the message to be understood. For example, the nurse might clarify, ‘By aids to help you at home I mean things like a seat that fits across the bath, grip rails in the bathroom for you to hold onto and perhaps a ramp instead of steps at your back door.’

• Time the delivery of the message appropriately: timing is important when giving information of any sort. Trying to tell a client about what will happen in surgery just as the pathology nurse is taking a blood sample would demonstrate poor timing, as the client’s concentration would not be totally focused on the message.

Non-verbal communication

In nearly every interaction, words are accompanied by simultaneous non-verbal messages that the sender may not be consciously aware of. Non-verbal communication refers to messages transmitted without using words. They include those transmitted via:

• Personal appearance (Ellis 2009).

It is generally accepted that non-verbal messages form the most significant component of communication (Schuster 2010). Research conducted by Professor Albert Mehrabian in 1972 first identified that in conversations messages transmitted and received are about 7% words, 38% tone and pitch of voice and 55% non-verbal clues. These percentages have not been contradicted by any other research, neither has the proposition, identified by Mehrabian in 1972, that most non-verbal messages are about emotions and that they are mostly automatic. Thus they are so more reliable than words because they are not as easy to fake (Mehrabian 1972). Hence the saying ‘actions speak louder than words’.

During interpersonal communication with clients it is essential for the nurse to look as well as listen. Concentrating only on words means that much of what could be discerned is being missed. Non-verbal communication comes from many sources and it is easy to miss something significant. For example, while watching a person’s foot tapping, a significant hand gesture or eye movement may not be noticed. Generally, non-verbal messages are not received in isolation and they are interpreted subconsciously but nurses need to develop the skills of consciously considering verbal and non-verbal messages, together and in context, and validating the meanings perceived in the messages (Ellis 2009).

Facial expressions

Facial expressions convey emotional states, and so a great deal of information can be obtained about clients’ feelings by observing their facial expressions (Ellis 2009). For example, a frown or an eyebrow raised in disbelief reveals something of how a client is reacting to what is being said. Some specific facial expressions of emotion seem to be universal across cultures. They are those that convey surprise, fear, disgust, anger, happiness and sadness. Facial expressions provide the nurse with continual non-verbal feedback from most clients, but some people have expressionless mask-like faces that reveal little or nothing of what they are thinking or feeling. This may be a client’s usual demeanour but sometimes it is due to the effects of an illness such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s dementia or severe depression. In such cases the nurse must detect the client’s mood from other clues such as body posture, activity level and appetite, or simply by asking how the client is feeling.

Clients are often very sensitive to the facial expressions of the nurse and it is imperative that, even though it is sometimes difficult to control, nurses make every effort not to facially express feelings of shock, alarm, repulsion or any other negative emotion in front of the client (Schuster 2010). Imagine the effect on a client with a stoma, an amputation or serious burns who detects repulsion on the face of a nurse. Additionally, nurses need to develop awareness of the effect their facial expressions may have on clients during procedures and interactions of any sort. For example, a nurse frowning in concentration while dressing a wound may be interpreted by the client as the nurse being worried and concerned about the look of the wound.

Body movements and gestures (body language)

The way individuals move, walk, sit or stand communicates information about their mood, attitude, state of mental and physical health, and self-esteem (Bach & Grant 2009). An upright posture together with decisive, quick and purposeful movements communicates a sense of wellbeing and self-confidence. A slumped posture, hesitant movements and a slow shuffling or stumbling gait may indicate depression, physical illness or impairment or that a person is drug affected or fatigued.

Some basic communication gestures convey the same message in almost every culture. For example, nodding the head is almost universally used to indicate ‘yes’, or affirmation.

Conversely, a specific gesture may be meaningless or assume a different meaning in another culture. Even within one culture a meaning may be different according to whether the gesture is made in certain ways. In most European countries the V sign means victory when gestured with the palm facing away from the body and a rude ‘shove it’ when the palm is facing towards the body of the person gesticulating (Haynes 2002). See Chapter 8 for more information on cultural differences.

Although body language can communicate much about how a client is feeling, it is a mistake to interpret a single movement, gesture or facial expression in isolation. For example, a person with arms folded across the chest and stomping about might simply be protecting himself from the cold, but if this was accompanied by sobbing, shouting or a facial grimace it may indicate severe pain, distress or anger. All non-verbal clues need to be observed together when considering what is really happening.

When a person’s actions or gestures do not match spoken words, the messages are said to be incongruent (Schuster 2010). This means that the body movements or gestures are conveying one message, while the verbal words are conveying a different message. When a client conveys incongruent messages it is important that the nurse tries to clarify what is happening even though it may at first feel awkward doing so. Clinical Interest Box 6.3 provides an example of how a nurse can explore incongruence between verbal and non-verbal messages.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 6.3 Recognising verbal and non-verbal communications

Andrew, 40, was admitted to hospital for overnight observations after being concussed in a motor vehicle accident the day before. The nurse was concerned because, although there seemed to be no problems from his concussion, she had observed Andrew limping and grimacing when he was walking around. When she asked if he had any pain he said no. The nurse began exploring the incongruent messages being received by saying, ‘I am concerned about you because even though you say you have no pain you seem to have trouble walking’. After talking with Andrew for only a short while he admitted he had considerable pain in his foot, but did not want to tell anyone because he could not afford any more time in hospital and thought it was probably only bruising that would get better without treatment. X-rays revealed that Andrew had broken two bones in his foot, which, without correct treatment, could have resulted in permanent disability.

Eye behaviour

Eye contact is one of the most crucial aspects of communication. How often people make eye contact or how long they hold a gaze can make a vital difference to the quality of an interaction. Eye contact and behaviour can convey openness and sincerity, and an individual’s emotional state and level of interest in a person or what is being said, and a failure to make eye contact can reduce the effectiveness of communication (Schuster 2010).

Causes for failing to make eye contact include:

The norms about what eye contact means, how often it should occur and with whom, differ in varying degrees from culture to culture, generation to generation. According to their cultural norms, people try to balance their eye contact somewhere between staring and avoiding all contact. Some of the differences in eye behaviour include:

• Gazing at the neck rather than at the face when conversing

• High intensity of gaze (that others may find offensive)

• Use of prolonged eye contact to gauge trustworthiness

• Avoiding eye contact as a sign of respect

• Eye contact can make other people feel awkward, so they may look the other way during conversations (Williams 2008).

Nurses therefore need to consider cultural differences when using eye contact with clients (Bach & Grant 2009).

Looking down on a client from a higher position can be intimidating. When clients are in bed it is preferable for the nurse, or any other health professional, to sit down and make eye contact at eye level because communicating at eye level indicates equality in a relationship. Conversely, rising to the same eye level as a person who is angry, bossy or intimidating in any way, may reduce feelings of vulnerability because it helps to establish a more equal sense of power (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Touch

Touch (tactile communication) is one of the most powerful and personal forms of expression. A person’s first comfort in life comes from touch, and so, frequently, does their last, as touch may communicate with a dying person when words cannot. There is no way to practise nursing without touching and, in nursing, touch may be the most important of all non-verbal communications. Touch occurs in everyday procedures such as taking vital signs and assisting clients with showers or baths. It also occurs at times of joy, fear, stress and loss. How nurses use touch in client care conveys a great deal about the way they feel towards their clients and their illnesses.

In nursing, touch can be used therapeutically to transmit positive feelings of understanding, compassion or reassurance. To be effective, tactile communication must be used at the appropriate time and place. Not all people like to be touched and all individuals consider a certain amount of space around them as private. Touch can be seen as an invasion of that privacy unless it is desired. Touch must be used at the right time and in the right way, otherwise the message may be misinterpreted. Nurses always need to assess and be sensitive to how comfortable the client is with being touched (Schuster 2010).

Space

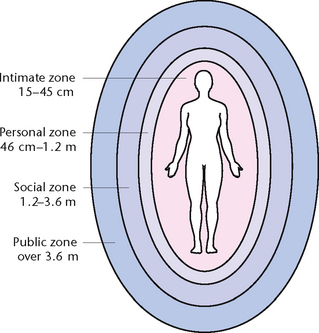

The concept of ‘space’ is important in communication, as it determines the distance a person usually keeps between themself and other people. The individuals involved, and the context or situation, dictate acceptable distance zones. People surround themselves with their own ‘informal’ personal space, which is invisible and mobile, and nurses need to be aware not to impinge on another person’s personal space (Schuster 2010). There are four categories of space or zone (Fig 6.3).

The intimate zone (between 15 cm and 45 cm from the body surface) is the most important to a person, who guards it as if it were personal property. Usually only those who are emotionally close to the person are permitted to enter this zone, such as spouses, partners or lovers, parents, children, close friends and relatives. The personal zone (between 46 cm and 1.2 m) is about the distance individuals keep between them at friendly gatherings and social functions. The social zone (between 1.2 m and 3.6 m) is the distance individuals keep between themselves and strangers or people who are not well known to them. The public zone (over 3.6 m) is a comfortable distance at which an individual generally chooses to stand when addressing a large group of people (Schuster 2010).

The nature of nursing practice means that nurses frequently invade a client’s intimate or personal space. Many clients will be uncomfortable with this closeness, and nurses should be sensitive to how each client is responding. Conversely, such necessary closeness when handled sensitively may promote rapport between a nurse and a client.

Personal appearance

Personal appearance has a strong influence on the initial perceptions and first impressions people form about others. Physical characteristics, degree of cleanliness, manner of dress, style of hair and makeup are some of the things that provide the information from which impressions are formed. The adornments that a person wears or carries, such as jewellery, handbag or briefcase, provide additional information, as do the objects with which they decorate their environment. People tend to judge others by their appearance, a habit that can be detrimental, as it can lead to incorrect assumptions. For example, the social or financial status of a person may be incorrectly inferred from the clothing worn (Bach & Grant 2009).

The appearance of clients provides nurses with general impressions of their state of physical and emotional health that are useful, but these impressions need to be validated by verbal information and objective measurements. Clients also form a general impression from the initial appearance of a nurse, and well-groomed nurses are likely to create a favourable impression of professionalism.

ASSERTIVENESS TO ENHANCE COMMUNICATION

Assertiveness is the ability to express one’s feelings and assert one’s rights while respecting the feelings and rights of others. Assertive communication is appropriately direct, open and honest, and clarifies one’s needs to the other person (Ellis 2009). Assertiveness comes naturally to some, but is a skill that can be learned. People who have mastered the skill of assertiveness are able to greatly reduce the level of interpersonal conflict in their lives, thereby reducing a major source of stress.

Sometimes people confuse aggressiveness with assertiveness, seeing that both types of behaviour involve standing up for one’s rights and expressing one’s needs. The key difference between the two styles is that individuals behaving assertively will express themselves in ways that respect the other person. They assume the best about people, respect themselves, and think ‘win–win’ and try to compromise. In contrast, individuals behaving aggressively will tend to employ tactics that are disrespectful, manipulative, demeaning or abusive. They make negative assumptions about the motives of others and think in retaliatory terms, or they don’t think of the other person’s point of view at all. They win at the expense of others, and create unnecessary conflict. Passive individuals don’t know how to adequately communicate their feelings and needs to others. They tend to fear conflict so much that they let their needs go unmet and keep their feelings secret in order to ‘keep the peace’. They let others win while they lose out; the problem with this is that everybody involved loses, at least to an extent (Ellis 2009).

Benefits of assertiveness

Assertiveness affects many areas of life. Assertive people tend to have fewer conflicts in their dealings with others, which translates into much less stress in their lives. They get their needs met (which also means less stressing over unmet needs), and help others get their needs met, too (Schuster 2010). Having stronger, more supportive relationships virtually guarantees that, in a bind, they have people they can count on, which also helps with stress management, and even leads to a healthier body. Contrasting with this, aggressiveness tends to alienate others and create unnecessary stress. Those on the receiving end of aggressive behaviour tend to feel attacked and often avoid the aggressive individual, understandably. Over time, people who behave aggressively tend to have a string of failed relationships and little social support, and they don’t always understand that this is related to their own behaviour. Ironically, they often feel like victims, too.

Passive people aim to avoid conflict by avoiding communication about their needs and feelings, but this behaviour damages relationship in the long run. They may feel like victims, but continue to avoid confrontation, becoming increasingly angry until, when they finally do say something, it comes out aggressively. The other party doesn’t even know there’s a problem until the formerly passive individual virtually explodes. This leads to hard feelings, weaker relationships and more passivity. See Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Assertive behaviour versus aggressive or passive behaviour

| Aggressive | Passive | Assertive |

|---|---|---|

| Raised voice | Looking away from speaker | Eye contact |

| Blaming | Saying yes reluctantly | Nodding and giving feedback to a speaker |

| Pointing | Turning away from speaker | Showing respect for the other speaker |

| Shouting | Hiding under the desk | Explaining clearly why a suggested deadline might not be possible |

| Standing with hands on hips | Wafling | Taking responsibility for one’s own feeling |

| Talking over a speaker | Shufling feet | Acknowledging the other person’s position/feelings |

| Standing over a seated person | Avoiding confrontation | |

| Constantly ‘topping’ a person’s story | ||

| Public criticism | ||

| Standing too close to a person |

THERAPEUTIC COMMUNICATION

Communication is neither innately nor intuitively derived, but is an activity that must be learned (Ellis 2009). Therapeutic communication requires knowledge of the concepts and theories of the communication process, as well as skill in applying them. Therapeutic communication requires practice, time and effort, and a desire to improve. Communication can generally be improved if people increase their understanding of the process of communication; develop heightened self-awareness, particularly in relation to personal attitudes, values and beliefs; and develop increased sensitivity to others (Bach & Grant 2009).

Clinical Interest Box 6.4 provides examples of some techniques for therapeutic communication.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 6.4 Therapeutic communication

Therapeutic communication techniques in nursing are those that:

• Convey respect and acceptance of clients, no matter what situation they are in or illness they have

• Encourage the expression of the views, feelings and ideas of others

• Demonstrate a non-judgmental attitude towards the situations, views, feelings and ideas of others.

They include the skills of assertive communication, active listening, asking questions, providing feedback, paraphrasing, clarifying, reflecting, using silence and summarising.

SKILLS TO FACILITATE THERAPEUTIC COMMUNICATION

Active listening

Active listening is not an automatic ability. It is a skill that develops with practice and perseverance. Active attentive listening is as important to the process of therapeutic communication as speaking and it could be said that the art of therapeutic conversation lies in the ability to listen with perception.

Active listening requires attention and concentration, to hear not only the words but the feelings or meanings that are often hidden behind the words. Active listening involves being tuned in and ready to receive messages (Bach & Grant 2009). Nurses can demonstrate readiness to listen by minimising environmental distractions and adopting a posture of involvement that includes:

• Sitting at a comfortable distance away from the client

• An open relaxed posture (arms not folded and legs not crossed)

Active listening incorporates simultaneously listening for the content, or facts, of the message, and the feelings in or behind the message. Sometimes feelings are expressed openly, for example, ‘I’m really fed up and I am scared that this ulcer on my leg will never heal’, but often feelings are only hinted at, implied or talked around. Sometimes it is the way something is said that reveals how a client is feeling; for example, ‘My doctor was here just now; he said everything is going fine, according to plan’, might be said in a way that reveals the client is happy about the news, or in a way that indicates the client doubts the truth of the news. Sometimes feelings are deliberately concealed or expressed only non-verbally (Williams 2008).

Active listening requires the nurse to:

• Focus on the speaker’s ideas

• Pay close attention to what is said

• Avoid interrupting the other person’s speech or being anxious to butt in

• Avoid thinking about what to say next while listening

Communication strategies that indicate active listening include eye contact, nodding or smiling to encourage the speaker to continue, prompting the speaker by using expressions such as ‘go on’ or ‘then what?’ and asking questions to clarify what has been said.

Asking questions

Nurses ask questions to gain information from clients. The responses provide the data from which care is planned and implemented. The type of questions asked depends on the situation and the type of response required. Some questions call for simple and direct responses, while others are more probing in nature. Types of questions used during nurse–client interactions include those that are closed, open-ended, primary, secondary, summary and reflective (Ellis 2009).

Closed questions

Closed questions are those designed to elicit a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or a very short and factual answer. Closed questions often start with ‘who’, ‘where’ or ‘when’. For example, ‘When did you last see your medical practitioner?’ is a closed question, and the expected response to this question would be merely a date. Closed questions limit options. They are not designed to elicit extensive detail or to discover or explore feelings or attitudes (Ellis 2009).

Open-ended questions

Open-ended questions are designed to evoke a long answer. They enable a person to choose how much or how little information to reveal. Open-ended questions often start with ‘why’, ‘what’ or ‘how’. Open-ended questions are more effective in encouraging a person to elaborate on a topic, as such questions cannot be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ (Williams 2008). This style of questioning invites the person to reveal personal perceptions, views, thoughts and feelings (Ellis 2009). For example, ‘What were your reasons for choosing to move from Alice Springs to Melbourne?’ is an open-ended question. The nurse should always allow the client to fully answer each question before moving on to a follow-up question or changing the topic.

Primary questions

Primary questions are those that introduce new topics or areas, while secondary questions are used to probe for more information. Secondary questions are sometimes referred to as follow-up or focused questions. They aim to get more complete or accurate data. Both primary and secondary questions may be closed or open-ended.

Summary questions

Summary questions summarise a series of questions and answers to make sure that an accurate understanding has taken place, for example, ‘Let me see if I have understood what you have told me. You had a heart attack when you were aged 47, the following year you were diagnosed with diabetes, and now you are having problems keeping your blood sugar levels within the recommended range?’

Reflective questions

Reflective questions are sometimes used to help correct real or suspected inaccuracies, for example, ‘Didn’t you say that you had your heart attack before you were diagnosed as having diabetes?’

‘Why’ questions and leading questions

It may hinder the development of a therapeutic relationship to use questions beginning with ‘Why?’ because they may seem judgmental. For example, ‘Why don’t you want a shower?’ can sound accusatory to a client. It is better to ask, ‘I’m concerned that you don’t feel up to a shower; how are you feeling?’

It is also recommended that the use of leading questions be avoided. Leading questions are rhetorical because they have an implied answer and are often used to confirm what nurses think they know (Williams 2008). For example, clients might find it easier to answer ‘Yes’ to a leading question such as ‘You’re all right, aren’t you?’; while they might feel obliged to answer ‘No’ to the question ‘You don’t need any more pain relief, do you?’ Clients might interpret such leading questions as the nurse not caring or not being interested in how they are really feeling, or not having the time to be concerned.

When clients are admitted it is usual for the nurse to ask a range of questions. Most interviews comprise a mixture of closed and open-ended questions, but nurses need to be sensitive to the fact that overuse of closed questions can seem like an interrogation. Being bombarded with multiple closed questions as a nurse completes an admission form can feel dehumanising because it does not provide an opportunity for clients to talk about issues that might be important and of concern to them. It is often a more relaxed and friendly approach to ask questions less directly. A gentle command could be used instead; for example, ‘Tell me about your health over the last few years’ may elicit most or even all the information needed but gives some control to the client. Skilful questioning, using mostly open techniques, can be a way of beginning a meaningful relationship with a client (Schuster 2010).

Feedback—paraphrasing, clarifying and reflecting

Other techniques that help the communication process are clarifying, paraphrasing and reflecting. All these are methods of providing feedback. Feedback is a very important component of the communication process. If a listener is not providing any feedback, the sender has no way of knowing whether a message has been received or how well it has been understood (Ellis 2009).

Facial expression and body language can provide some feedback from the listener to the sender, or the person who is sending the message can obtain feedback by asking the listener to verbally express their understanding of what was said, or to demonstrate understanding (Schuster 2010). For example, after a nurse has taught a client how to use an aerosol inhaler, the client can be asked to demonstrate understanding by showing the nurse that they can use it effectively. Alternatively, the listener can describe their perceptions of a sent message by using the skills of clarifying, paraphrasing and reflecting, all of which give the sender the opportunity to correct any misperceptions.

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is a technique whereby the listener reiterates what the sender has said in their own words, more briefly whenever possible. Paraphrasing is a means of sending feedback to the sender of the message that lets the person know whether or not the meaning of the message was received as intended. Paraphrasing can be very effective for checking understanding of the content of a message, whereas reflecting works particularly well to reiterate the client’s feelings (Schuster 2010).

Clarification

Clarification is used in situations in which there is a lack of sense about what a client means, to the degree that it makes the use of paraphrasing impossible. Clarifying reinforces that the nurse is trying to gain an understanding, and the nurse should not continue until clarification has been managed (Ellis 2009). The nurse must be careful not to put blame for lack of clarification onto the client; for example, saying, ‘You’re not being very clear about how this happened’ would be unhelpful, might alienate the client and would not facilitate a therapeutic relationship. It would be better for the nurse to take responsibility and say, ‘I’m having some trouble following what you mean’.

When needing to clarify it is possible to ask a direct question such as ‘What do you mean?’, but this is best avoided because it may sound critical and accusatory to clients. Whatever way clarification is sought the tone and pitch of voice, facial expression and body language used can make a difference to how the client feels about not being understood.

Reflecting

Reflecting is another skill that can be used to check that a message received has been correctly interpreted (Williams 2008). Reflection is the mirroring of feelings the nurse believes have been expressed by clients. The feelings are reflected by the nurse’s words as a way to check that perception of a client’s feelings is correct. For example, a client may say ‘Just look at me, I’ve lost so much weight since I’ve been in hospital’. The nurse might reflect back the feelings perceived by using a reflective question, ‘You’re anxious about how much weight you have lost?’. The client may confirm with a ‘yes’ or correct a misperception by saying, ‘Oh no, I feel good—I’ve been trying to get to this weight for years.’

Reflecting feelings is especially important in nursing because it conveys that the nurse recognises and accepts a client’s emotions as a valid part of the illness experience (Williams 2008). For example, a client may say, ‘This hip of mine doesn’t seem any better now than before the operation’. The nurse may reflect, ‘You seem pretty frustrated (anxious/worried) about your lack of progress’. This validates the client’s feelings and at the same time provides permission for the client to talk more about what is being experienced. Reflected feelings should be stated tentatively, no assumptions should be made about what a client is feeling unless stated directly, and often they are only implied or hinted at. It is quite difficult to select the right words to describe a feeling and the intensity of it. The nurse should not proceed with dialogue about a client’s feelings until the client has verified that the nurse’s perception of what the client is feeling is correct. Care is also needed not to underestimate or overestimate the intensity of the feelings that a client is experiencing (Stein-Parbury 2009).

It is often helpful and therapeutic for a client to be able to share what they are feeling with the nurse. But not all clients want to talk about what they are feeling. They may prefer to keep those feelings under control or share them with someone else—a partner, close family member, friend or priest, for example. The nurse must respond sensitively to the messages given out by clients when they initiate discussion of feelings, and clients should never feel coerced into talking about feelings they prefer to keep contained.

The use of silence

Silence, used correctly as a communication tool, can be as effective and as supportive as words (Williams 2008). There are instances where words seem inadequate when a person wishes to convey thoughts and feelings to another person. In such instances, it may be most helpful simply to sit quietly with the person and share the silence. Just to be with another person at moments of grief, sorrow, conflict or joy may be more helpful than trying to fill the silence with useless words or clichés.

In some situations silence is not productive and can cause discomfort. Silence can be used to indicate approval or disapproval of a situation, or it may be used to punish or hurt another person. In such instances silence causes barriers to communication and may cause a person to feel inferior or rejected. There are times in nursing when silence is not therapeutic. During interviews with clients there may be times when the nurse cannot think how to respond to what a client has said. It is understandably difficult to know how to respond when a client says something such as ‘I don’t want this baby’ or ‘I know I’m going to die’ or ‘my life will never be the same now’. If what is called ‘a stumped silence’ ensues after personal information or strong views or feelings have been revealed, the client may feel awkward and perceive that the nurse is expressing negative judgment or disapproval. Rather than have an uncomfortable stumped silence it is better to use the skill of paraphrasing or reflecting feelings, touching gently or saying something such as ‘I wish I knew what to say to help’. Nurses need to develop awareness of stumped silences and practise communication strategies that help avoid them, and ways to use silence therapeutically.

Summarising

Summarising is a way of briefly highlighting the key aspects of a conversation. It is a skill most often used before terminating an interaction or nurse–client interview. In addition to clarifying, paraphrasing and reflecting feelings, it is another method of allowing the nurse to check understanding of what has been shared and discussed, and to have that understanding confirmed or corrected by the client. Summarising is a helpful strategy in that it also informs the client that the interaction is coming to a close and provides the opportunity for the client to raise any issues of concern not yet discussed (Schuster 2010).

Summarising is important because it is not uncommon for clients or relatives to present the most significant aspect of what has been happening to them just as the interview is about to end. This is probably because the significant aspects are often those that are embarrassing or that elicit the most intense emotions. These things are not easy to share and, as the nurse summarises, clients realise that the opportunity to do so will soon be gone. The nurse should factor this possibility into the time allocated for interactions. Summarising and permitting the client to raise issues not previously mentioned enables the client and the nurse to feel a sense of satisfactory completion at the end of the interaction (Williams 2008).

Summarising can also be useful at the beginning or midway through an interaction. Sometimes it is helpful for the nurse to summarise the content of a previous interaction, for example, ‘When we last spoke you told me you were anxious about who was looking after your home and your dog while you were in hospital and that you were going to contact your neighbour about keeping an eye on things. How have things worked out?’ This serves to focus the interaction into the area needing further exploration.

Midway through an interaction it may be helpful to summarise before moving on to a new topic; for example: ‘Before we talk about what will happen after your surgery, just let me see if I have things clear. You haven’t had anything to eat or drink since 6 o’clock this morning. You haven’t taken your medication that was due at lunchtime, and you are worried because you were so unwell after your last anaesthetic. The only other thing is that you want me to make sure the anaesthetist is coming so that you can talk to him about that.’

In addition to confirming or correcting the content of the interaction as perceived by the nurse, this can help clients recall what has been said so far and prompt questions they might wish to ask while the issues are fresh in their mind. Whether the summary is at the beginning, midway or at the termination of an interaction, sufficient time should be allowed for the client to expand on a point, clarify misperceptions or add something new (Ellis 2003).

The skills of listening, understanding, exploring, intervening and summarising and the effective use of verbal and non-verbal techniques combined are the basic building blocks on which all successful relationships are based. Nurses adapt these basic skills according to the context in which interactions take place and according to the individual needs of each client. As the ability to adapt communication skills grows with increasing experience, nurses tend to function more strongly from a position of ‘being with’ rather than ‘doing to’ the client (see Clinical Interest Box 6.5).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 6.5 Summarising as an effective communication technique

A community health nurse might summarise an interaction in a client’s home: ‘So, to sum up, your mum has now been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia. As well as looking after your own home and your two children you are currently doing all the shopping, cooking and cleaning for your mum, and there is no-one else who can help. You agree for me to arrange a visit from the Aged Care Assessment Services to see what help is available.’

After waiting for points to be clarified and the summary to be confirmed or corrected, the nurse might then ask, ‘Is there anything else you would like to ask or tell me before I go?’

Conveying empathy

Empathy refers to the ability to recognise and understand the essence or reality of a client’s experience and to relay that understanding to the client. Empathy is considered to be different from sympathy. Sympathy is seen by some as subjectively sharing the feelings of the other person whereas empathy is seen as ‘feeling with’ and knowing the other person’s experience without equating the intense feelings with past personal experience. In nursing, empathy is often viewed as a more desirable response than sympathy, but more research is needed to determine what type of responses are of most comfort to clients (Schuster 2010).

Empathy can be communicated by touch, by direct, clear and accurate statements that reflect understanding of the core of a client’s experience, and by skills such as reflecting feelings. These are the communication aspects of empathy, but how to feel it cannot be learned from textbooks, as it is an intrinsic characteristic. Nurses need self-awareness of their inherent capacity for empathy so that they can strengthen it through practice and learn how to communicate it using a unique personal style rather than a textbook formula (Schuster 2010).

Expressions of empathy foster feelings of trust. If a person is able to demonstrate an understanding of how another person is feeling, rapport is established between them, and this promotes mutual trust. Trust is a belief that a person will respect another’s needs and will behave towards them in a responsible and predictable manner. When people trust each other they feel more comfortable in their relationship, and communication is more effective.

Self-disclosure

Self-disclosure refers to the skill of sharing personal experiences, feelings, thoughts, ideas and views with clients in a way that is comforting. It can be comforting because it communicates understanding of the client’s situation and feelings and reinforces that the experience is not unique (Crisp & Taylor 2009). Self-disclosure should only be used when it is helpful to the client, the purpose is to benefit the client, and the focus will not remain on the nurse after self-disclosure has occurred. For example, the nurse might say, ‘I had a premature baby 2 years ago and was overwhelmed with the constant demands. I was lucky I had a lot of support. What sort of support will you have with your baby?’ Self-disclosure can be used as a means of prompting and encouraging clients to express their own fears, feelings and experiences. It also sends a message that the nurse trusts the client with personal information, which may help the client to feel comfortable enough to reciprocate that trust (Stein-Parbury 2009).

The use of humour

Fun and laughter can be very therapeutic, but humour needs to be used with caution and, initially, tentatively when people are ill or upset and vulnerable, because not all people share or appreciate the same sort of humour. Humour has the potential to:

• Release tension and reduce anxiety

• Reduce depression by stimulating the release of endorphins from the hypothalamus

• Stimulate immune system functioning

• Reduce pain by decreasing serum cortisol levels (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

The use of humour can promote rapport between nurse and client and facilitate communication that is relaxed and comfortable. However, it should be used to benefit the client and never as a mechanism to hide behind when nurses are ill at ease in particular situations.

COMMUNICATING WITH CHILDREN, ADOLESCENTS AND OLDER ADULTS

In addition to the skills previously explained, there are some additional aspects to consider when communicating with children, older adults and clients’ relatives and friends.

Older adults

Older adults may need more time to respond during conversation or to answer questions because they have a large repertoire of experiences to draw on and sorting through them requires time. The process of retrieving a memory of an event and the words needed to express themselves may be slower than in previous years. This may be due to memory impairment associated with normal ageing. It may be mild, and many older people adapt to this change, but at times of stress, tiredness or when situations are demanding, the slowed ability to recall events and words may be much more noticeable. The nurse needs to be patient and allow older clients adequate time to respond. If sure of a word the client is searching to remember, it may help, after waiting a few moments, to provide it.

Older adults sometimes find it takes longer to absorb new knowledge, especially if the information does not connect to familiar concepts. Older and younger clients alike find it more difficult to absorb information while anxiety levels are high. Giving new information to older clients while they are ill, upset or anxious is likely to mean that they will be unable to recall it (Ebersole et al 2008). Nurses also need to consider that many older clients will have age-related changes to hearing and vision that also impact on communication.

Children

Ability with language and the processing of concepts and thoughts differs according to a child’s age and developmental level. The nurse needs to adapt the style of communication according to these differences. Table 6.2 presents some basic guidelines for communicating effectively with children.

Table 6.2 Guidelines for communicating effectively with children

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Address parents first at the initial meeting, then the child | It is courteous to address the parents and the child at the start of the interview, but the focus should then move to communicating directly with the child |

| Put children at ease; for example, by asking their name, stating yours and talking about their friends/toys/pets/school | A child who is relaxed generally communicates quite freely |

| Talk directly to children (do not continually direct remarks or questions to the parents) | Demonstrates respect for the child. Sometimes in their anxiety parents tend to answer for their child; talking directly to the child helps to avoid this and demonstrates respect for the child and the child’s feelings and opinions |

| Talk at eye level | Standing above a child is intimidating |

| Ask children questions that they can answer on their own. If parents are present, the nurse should look to them for confirmation or reply only when necessary | Establishes a relationship with the child and begins to develop trust |

| Explain any procedures or activity to be performed in terms the child can understand. Include the child in the discussion when a plan of care is being explained to the parents | Children are more likely to accept interventions if they know what to expect |

| Talk with a child as you would an adult; for example, be honest, do not disregard any information the child offers. Provide older children with the chance to speak without the parents present | Demonstrates respect for the child |

| Answer a child’s questions honestly whenever possible. For example, if a child asks if a procedure is going to hurt, it is much better to be honest | If a child has been told that a procedure will not hurt, and it does, trust in the nurse will be reduced |

| Respect a child’s confidences. If a child reveals information necessary for a parent to know, explain why this is so and suggest the child tells the parent. Otherwise seek the child’s permission to talk to the parent about the matter | Failing to respect a confidence destroys trust |

Adolescents

As when communicating with anyone, all the skills that enhance effective communication are employed when talking with adolescents. Adolescents may be very sensitive to feelings of being judged or criticised, so it is important to be open minded when listening attentively to their feelings, ideas and opinions. It is helpful for adolescents to have expectations clearly explained and it enhances self-esteem when praise is given appropriately. Chapter 11 provides more information to assist the nurse when interacting with adolescents.

COMMUNICATING WITH CLIENTS’ RELATIVES, FRIENDS AND SIGNIFICANT OTHERS

The loved ones and friends of a sick person will often need support to help them cope with that person’s illness. A person’s illness can be a very disruptive episode in the lives of their significant others. They may need to discuss their concerns and share the frustrations of the illness. Table 6.3 provides some general guidelines for communicating effectively with relatives, friends or others who are emotionally close to a sick client.

Table 6.3 General guidelines for communicating effectively with relatives and friends

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Introduce yourself to the relatives and inform them that you are helping to look after their loved one | It is a common courtesy to greet all visitors regardless of whether or not they need support or information |

| Provide them with opportunities to express any concerns and anxieties | Simply having concerns heard can reduce stress |

| Include them in discussions about the individual’s care when appropriate; for example, only when certain that the client approves | Relatives have often been providing care at home for clients before their admission to hospital and will often continue care after the client is discharged from hospital. It is rude and dismissive of their care work to exclude them from care planning decisions |

| Offer opportunities to assist with care activities as appropriate | Often relatives like to feel useful, needed and involved |

| Answer their questions as appropriate (be aware of confdentiality issues) or refer questions to the nurse in charge | The unknown is often very stressful. Information is important in planning for what is still to come |

| Demonstrate warmth; for example, by touch, close proximity, body posture and facial expressions. This is of particular relevance when relatives are confronted with a loved one who is seriously ill or dying | When a loved one is sick or dying it helps to know others empathise |

BARRIERS THAT INTERFERE WITH THERAPEUTIC COMMUNICATION

Several aspects of communication can impair effective communication, hinder the development of trust in a therapeutic relationship and damage an existing one. In addition to the inappropriate use of humour mentioned earlier, some other communication pitfalls act as barriers to therapeutic relationships that nurses need to be aware of and avoid (Williams 2008). They are not hard to fall into inadvertently, but also they are not hard to avoid once aware of them. Using the basic communication skills previously outlined, together with avoiding the pitfalls, will enhance every relationship and facilitate therapeutic relationships between nurses and clients. Because of the emotional content of many nurse–client interactions, the potential for nurses to inadvertently put up barriers if they are not aware of them is high. Sometimes nurses unknowingly use communication barriers as a way of protecting themselves from uncomfortable feelings. Examples of these include changing the subject inappropriately and offering false reassurances and using clichés. A list of barriers that block effective communication is provided in Clinical Interest Box 6.6.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 6.6 Barriers to effective communication

• Stereotyping, labelling or pre-judging the speaker

• Becoming distracted or daydreaming

• Asking too many probing (perceived as prying) questions

• Listening only to content; not hearing feelings

• Not attending to non-verbal cues

• Finishing the other person’s sentences

Changing the subject inappropriately

People sometimes change the subject when they are uncomfortable with, or unwilling to discuss, a specific topic. For example, a client may say to a nurse, ‘I feel so weak, I don’t think I am going to be around for much longer’. If the nurse feels unable to deal with the feelings the client has raised, they may abruptly switch the conversation to a more comfortable area by saying, ‘You shouldn’t dwell on that. Let’s get you washed—where are your things for the shower?’ The client gets the message, accurate or not, that the nurse is not sensitive to their concerns. The nurse misses the opportunity to be helpful because the client is denied the opportunity to discuss their feelings, and therapeutic communication between the two is blocked.

False reassurance