CHAPTER 42 Emergency care

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to:

• State the aims and principles of emergency nursing care

• Recognise and overcome the barriers that can keep nurses from acting in an emergency situation

• Identify and act upon emergency situations according to organisation policy and procedure and within legal and professional requirements

• Apply a problem-solving framework in consultation/collaboration with the registered nurse to plan appropriate nursing management strategies

• Identify and respond to the early signs and symptoms of the deteriorating client

• Assist the registered nurse with providing the initial emergency management of the client until medical support arrives

cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

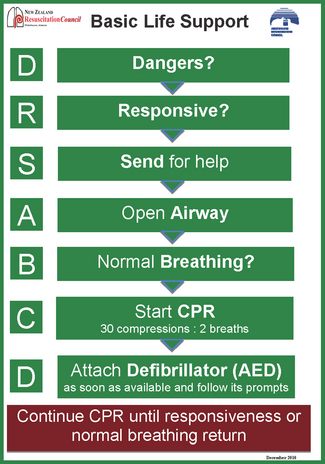

Dangers, Responsive, Send for help, open Airway, normal Breathing, start CPR, attach Defibrillator (DRSABCD)

This chapter provides a form of knowledge support to equip the enrolled nurse with the theoretical concepts and skills required to recognise and respond to emergency situations. The literature reports that the characteristics of clients in Australia and New Zealand and internationally are changing. Acute care hospitals now have an increasing percentage of clients with complex problems who are more likely to be or become seriously ill during their hospital stay (Bright et al 2004; Hillman et al 2001). The clinical condition of a client can change at any time; the key is to recognise and respond in a timely manner. In the healthcare facility the nurse is primarily ‘on the front line’ and usually the one who is the first responder so must be equipped with the skills and knowledge to react appropriately and initiate care until help arrives. The chapter also prepares the enrolled nurse to make sound clinical judgments and work as part of a team to provide the best possible care to the client and family/significant others. There is additional emphasis on the recognition of variations or deterioration in the client’s condition to enable the enrolled nurse to respond appropriately and effectively. Concepts introduced include the use of early warning systems (EWS), when to initiate a medical emergency team call (MET) and calling a medical emergency or code blue. Emergency response intervention including cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and basic life support (BLS) are also addressed. Importantly, effective inter/intraprofessional communication is essential and the mnemonics ISBAR—identification, situation, background, assessment and request—and AMPLE—allergies, medications, previous history, last meal, event—which are the handover tools used by paramedics are used to demonstrate effectiveness when communicating and reporting vital information.

Reflecting on my 25+ years of nursing I have seen many changes and learned many new things. I think the most important lesson I have learned is that in order to care for the ever-changing clinical conditions of our clients, the key components are to know your environment—a bedside safety check must be performed at the start of each shift to ensure all equipment is in good working order; and to know your clients—read their histories and always perform a complete baseline assessment including a full set of vital signs. As a newly graduated critical care nurse I witnessed a nurse attending to a client who had unexpectedly aspirated. The bedside check had not been carried out and the nurse involved found that there was no patent suction so portable suction had to be utilised instead. Luckily the client involved survived the event but the nurse involved learnt a valuable lesson.

INTRODUCTION

Caring for the deteriorating client involves recognition, timely response, client assessment, reporting, management, team work and prioritisation skills. In the clinical ward recognising alterations to the client’s physiological status requires the nurse to have a sound knowledge of physical assessment, vital signs within an acceptable range and when to respond to alterations in the client’s condition (Peberdy et al 2007). Enrolled nurses practise under the direction and delegation of a registered nurse or nurse practitioner to deliver nursing care and, accordingly, the enrolled nurse must work within the policies and procedure guidelines of their organisation. The enrolled nurse has a unique opportunity to contribute to the care of the client with complex medical conditions. Ongoing education based on current evidence allows the enrolled nurse to recognise, communicate and assist the multi-professional healthcare team in providing timely effective care to the client.

Where do emergencies occur?

Emergencies can take place anywhere: the ward area, perioperative unit, radiology and, of course, the emergency department. The outcome of the emergency situation is dictated by numerous factors including recognition and timely response, the experience of attending staff, coordination and communication.

Early recognition and response to a medical emergency

An emergency is a situation requiring immediate action. Recognising an emergency is the first step in responding. What happens next may be determined by the following factors that will help you recognise the at-risk or deteriorating ward client:

• Intuition: ‘gut feelings’ tell you to observe, look closer and question your clients

• Knowing the client: ensure that you read the history, the previous shift notes and perform a baseline assessment of the client

• Pattern recognition: look at the graphical charts and look for subtle changes in trends

• Physiological changes: in most instances these occur gradually. The key is to ensure that a thorough assessment and a full set of vital signs are performed and documented, and that changes, however slight, are reported to senior staff.

Remember that every time you see a client you perform some sort of assessment that may include evaluation. Always think DRSABCD (Dangers, Responsive, Send for help, open Airway, normal Breathing, start CPR, attach Defibrillator). This process allows you, as the enrolled nurse, to continually assess the client in both the long and the short term. Evaluation brings you back to the beginning of the assessment (see Box 42.1).

Box 42.1 Summary of guidelines for responding to an emergency situation

FIRST PERSON PRESENT

2. Check the client for Response and conscious state

3. If the client is unresponsive call for assistance, press the emergency bell to summon help

4. Assess the Airway, clear obstructions and perform airway-opening manoeuvre

5. If available/suitable correctly size and insert an oropharyngeal airway

6. Check for normal breathing. If unresponsive and not breathing normally, commence CPR with 30 chest compressions followed by 2 ventilations

7. Attach a defibrillator as soon as possible and follow its prompts. Ensure that the compressions are not interrupted while attaching the defibrillator

8. Continue CPR until the medical team arrives or signs of life (responsiveness, starts moving and normal breathing returns)

SECOND PERSON PRESENT

1. Dial switchboards and state:

2. Collect the emergency trolley

3. Connect bag-valve mask and attach high flow oxygen

6. Prepare an intravenous infusion

7. Draw up the resuscitation drugs

8. Prepare equipment needed for intubation of the client

9. The nurse unit manager or senior nurse will:

10. Staff shall provide information and support to friends/relatives of the client who are present

Ask yourself the following questions:

All nursing assessments and evaluations must be documented and reported to a senior staff member.

Client assessment

The assessment process consists of:

• Primary survey—airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure and remember ‘don’t forget glucose’

• Secondary survey—a thorough systematic assessment, head to toe

• Recording vital signs—this means temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation and pain level.

Managing deterioration

Initiate treatment by performing the initial stabilisation and calling for help. Making treatment decisions will depend on the enrolled nurse’s scope of practice as this varies from state to state. It may include initiating basic life support (BLS).

Barriers to instigating action

Barriers to instigating action can include:

• Being unsure of what to do: lack of knowledge of signs and symptoms that could signal deterioration

• Being unfamiliar with hospital policies related to calling medical emergency team (MET) or calling a medical emergency (code clue).

• Nurses feeling uncertain about whether they are doing the right thing in calling the medical emergency team

• Checking with other nurses: while seeking confirmation the client deteriorates further

• Waiting for observations to deteriorate: this is a knowledge deficit related to early warning scores (EWS), the parameters of vital signs or a lack of familiarity with the client and their baseline vital signs

• Being unable to communicate: language barriers or unable to articulate concise systematic information, unaware of ISOBAR.

Clinical Interest Box 42.1 outlines the criteria for all MET teams.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 42.1 Calling criteria for medical emergency teams used in Australia

Respiratory rate <5 breaths per minute

Respiratory rate >36 breaths per minute

Pulse rate <40 beats per minute

Pulse rate >140 beats per minute

Systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg

Sudden fall in level of consciousness (fall in Glasgow coma scale of >2 points)

Any client you are seriously worried about that does not fit the above criteria

RECOGNISING AND RESPONDING TO AN EMERGENCY

Primary care

Recognising an emergency is the first step in responding to an emergency, and giving prompt emergency care saves lives. To be able to provide emergency care, you must think and act in a systematic and coordinated manner, continually assessing and adjusting to changes in the client’s status. The first person on the scene recognises and responds to the emergency and delivers first aid (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) 2009).

Secondary care

The next stage involves continual assessment, care management and interventions which may require clinical skills such as cardiac monitoring, ECG interpretation, airway management, fluid resuscitation and haemodynamic monitoring (ACSQHC 2009).

CHANGES IN VITAL SIGNS

Observation charts are the primary tool for recording information about vital signs and other physiological measures, and therefore have a critical role in the identification of clients at risk (Buist et al 2004). Multiple studies provide evidence that there are observable physiological abnormalities that occur prior to events such as cardiac arrest, unexpected admissions to intensive care and unpredicted death (Cioffi et al 2009). Accurate measurements of vital signs are predictors of clinical deterioration or serious adverse events but these vital signs are not always measured, recorded or acted on. Nurmi and colleagues (2005) found that the frequency of documented observations prior to a cardiac arrest varied considerably between clients, and that only their pulse rate and blood pressure were recorded more than once in 24 hours. Abnormalities in vital signs such as blood pressure, level of consciousness, respiratory rate, heart rate and oxygen saturation are common prior to the occurrence of these serious adverse events.

In order to detect changes the enrolled nurse must have a sound knowledge of the normal ranges of these physiological measurements.

Modified early warning scores

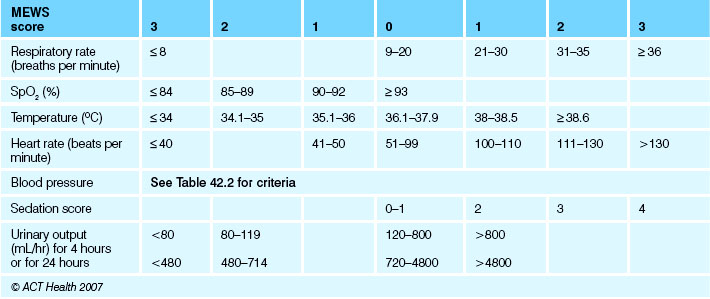

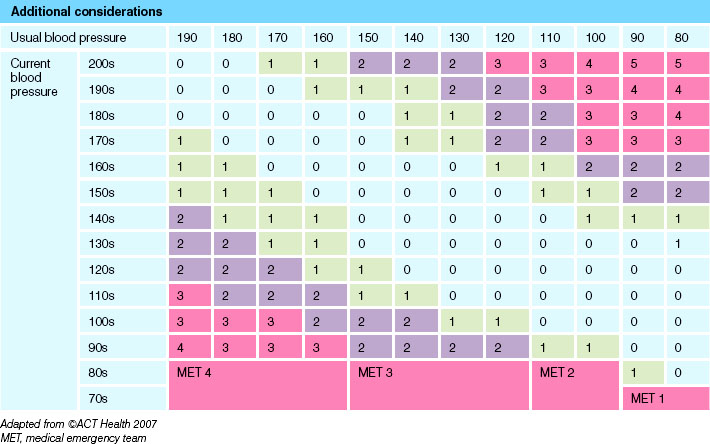

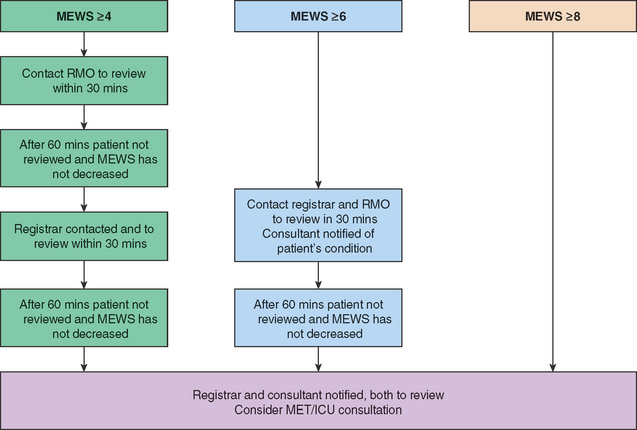

The idea behind modified early warning scores (MEWS) is to improve client outcomes by detecting and acting upon early signs of deterioration in clients (see Tables 42.1 and 42.2 and Fig 42.1). This will be achieved, in part, through the implementation of the MEWS system that:

• Identifies trends and changes in the client observations

• Ensures that timely review of the client occurs and appropriate treatment is provided

• Improves the accuracy of documentation of the client observations (ACT Health 2007).

A MEWS is calculated each time a set of observations is performed (see Clinical Interest Box 42.2). If a trigger score of 4 or greater is reached the activation protocol is initiated. Observations to be recorded include temperature, pulse, blood pressure, oxygen saturations (SpO2), respiratory rate, sedation score and urine output.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 42.2 MEWS

• MEWS does not replace calling the medical emergency team (MET)

• If the client meets the MET criteria a code blue/MET should be called as per hospital MET protocol

• MEWS, EWS systems may vary from one healthcare facility to another

• Ensure you are familiar with the provider’s policies and procedures

Other recommendations of the protocol include that the nurse caring for the client should report clinical changes when clinical deterioration, other than that assessed by the MEWS criteria, occurs or when sound clinical judgment would suggest that notification is in the best interests of the client. If the enrolled nurse is at all uncertain, consultation with a senior staff member should occur.

Systematic approach to assessment

One of the crucial steps in providing emergency care is proper assessment. Without timely and accurate assessment the chances of survival decrease. It is very important that client assessment is conducted in a systematic manner. This is to insure that life-threatening injuries are given immediate intervention to increase the chances of survival. The best way to do that is to start with the following:

A = Airway

The airway must be assessed for signs of obstruction; for example dentures, vomitus or a foreign body. To effectively assess the airway a jaw thrust or chin lift must be performed to allow for good visualisation and to open the airway. The mouth is opened and turned downwards to allow any foreign bodies or fluid to drain using gravity. Visible material can be removed using the fingers. The finger sweep is the accepted method for removing foreign bodies from the airway (ARC & NZRC 2010a).

B = Breathing

Assessment of effective breathing includes: monitoring the rate, depth and sound of the respirations; looking for the rise and fall of the chest; listening for sounds of the client breathing and feeling for the client’s breath on the side of the nurse’s face; observing for any chest deformity. Use of percussion and auscultation may be appropriate.

C = Circulation

In almost all emergencies, consider hypovolaemia to be the main cause. Check capillary refill time, which should be less than 3 seconds; look at colour of hands and fingers; assess limb temperature; count and palpate central pulses (rate, quality, regularity and equality); check blood pressure measurement. An appropriately accredited registered nurse or medical officer will insert an intravenous cannula, take bloods and administer intravenous fluids.

D = Disability

Rule out common causes of unconsciousness such as hypoxia or recent administration of sedative or analgesic drugs; review and treat ABCs, check pupils and check level of consciousness (see Fig 33.7 and Procedural Guideline 33.1).

E = Exposure

Examine client thoroughly; expose the body fully, respecting dignity and minimising any heat loss. Always ensure personal safety. Carry out an initial assessment then reassess. Treat life-threatening problems at each stage before moving on to the next stage. Assess and evaluate effects of any treatment.

BASIC LIFE SUPPORT

Basic life support (BLS) is a temporary measure providing myocardial and cerebral oxygenation until advanced life support (ALS) personnel and equipment are available (Australia & New Zealand Resuscitation Councils 2011). Early detection of a client’s physiological deterioration and prevention of cardiac arrest are now key strategies recognised for client survival rates in hospitals.

BLS includes airway management skills, rescue breathing techniques, external cardiac compressions and use of the automatic external defibrillator (which was designed for those with minimal training) (Australian Resuscitation Council 2011). The Australian Resuscitation Council recommends that all first responding emergency personnel, whether doctors, nurses or non-medical personnel, should be authorised, trained, equipped and directed to operate a defibrillator if their professional responsibilities require them to respond to persons in cardiac arrest.

According to the Australian Resuscitation Council (2011), healthcare facilities have a duty of care to ensure that staff maintain a level of competence that is appropriate to their role and scope of practice. Consequently all staff with direct client contact should have access to regular resuscitation education appropriate to their expected skills and scope of practice and this should be offered on a yearly basis (ARC & NZRC 2010a).

APPLYING THE PRINCIPLES OF EMERGENCY CARE

Indications

Respiratory arrest

Respiratory arrest can result from a number of causes, including stroke, drug overdose, suffocation, foreign body airway obstruction, injuries and myocardial infarction. When primary respiratory arrest occurs, the heart and lungs can continue to oxygenate the blood for several minutes, and oxygen will continue to circulate to the brain and other vital organs. Clients suffering respiratory arrest initially demonstrate signs of circulation. When the arrest occurs or spontaneous respirations are inadequate, establishment of a patent airway and rescue breathing can be lifesaving because it can maintain oxygenation and may prevent cardiac arrest (ARC & NZRC 2010a).

Cardiac arrest

Cardiac arrest in adults occurs both in and out of the hospital environment. The causes are numerous, but the expectations of the community are always the same: that professional nurses are able to provide appropriate methods of resuscitation in these situations (RCNA 2006).

In cardiac arrest, circulation is absent and vital organs are deprived of oxygen.

Cardiac arrest can be accompanied by the following cardiac rhythms:

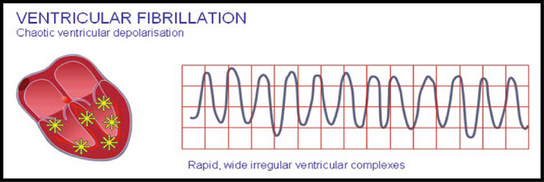

• Ventricular fibrillation (VF)

• Pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT)

• Rhythms associated with Pulseless electrical activity (PEA).

These potentially lethal rhythms will be discussed further later in the chapter.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

CPR is the technique of inflation of the lungs and compression of the heart, used in an attempt to revive a client who has suffered a cardiac arrest. CPR can restart normal heart action after cardiac arrest or maintain artificial circulation to preserve brain function until further treatment is available e.g. defibrillation (ARC & NZRC 2010a).

Remember: the earlier CPR commences the better the chance of perfusion to vital organs.

Defibrillation

Defibrillation is the therapeutic delivery of an unsynchronised electrical current to the myocardium. A defibrillation shock, when applied through the chest, produces simultaneous depolarisation (i.e. a short period of electrical asystole) of a mass of myocardial cells. This may enable resumption of organised cardiac electrical activity (Soar et al 2010).

Defibrillation is indicated for:

• Ventricular fibrillation (VF) (Fig 42.2): presents with chaotic electrical activity, the result of multiple ectopic foci (an area in the heart that initiates abnormal beats) that may occur in both healthy and diseased hearts and are usually associated with irritation of a small area of myocardial tissue. The causes may include medication, electrolyte imbalances, ischaemia originating from the ventricles and emotional stress. There are no organised QRS complexes (ventricular contractions). A client with this rhythm has no cardiac output, which means that the client has no circulating blood volume, therefore no blood circulating to the vital organs (Soar et al 2010). A person who has a VF episode will suddenly collapse or become unconscious, because the brain and muscles have stopped receiving blood from the heart

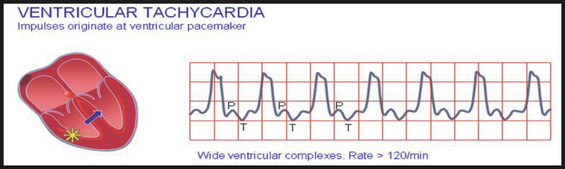

• Ventricular tachycardia (VT) (Fig 42.3): a rhythm of ventricular origin may also be a consequence of a slower conduction in ischaemic ventricular muscle that leads to circular activation (re-entry). The result is activation of the ventricular muscle at a high rate (over 120/min), causing rapid, bizarre and wide QRS-complexes; this arrhythmia is called ventricular tachycardia (Soar et al 2010). Ventricular tachycardia is often a consequence of ischaemia and myocardial infarction. In this arrhythmia the contraction of the ventricular muscle is also irregular and is ineffective at pumping blood. The lack of blood circulation leads to almost immediate loss of consciousness and death within minutes. The ventricular fibrillation may be stopped with an external defibrillator and appropriate medication. Remember: ventricular tachycardia may deteriorate to ventricular fibrillation and non-shockable rhythms are not responsive to defibrillation

• Asystole: characterised by the absence of any electrical activity on the ECG monitor; sometimes referred to as ‘flat line’. Ensure that asystole is not another rhythm that looks like a flat line. Consult with a registered nurse or doctor to rule out any other lethal arrhythmia. Fine ventricular fibrillation can appear to be asystole, and a flat line on a monitor can be due to operator error or equipment failure.

The following are common causes of an isoelectric line (baseline on an ECG) that is not asystole:

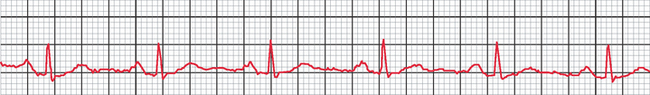

Pulseless electrical activity (PEA) is also known as electromechanical dissociation (EMD). PEA rhythm occurs when any heart rhythm that is observed on the electrocardiogram (ECG) does not produce a pulse. PEA can come in many different forms. Sinus rhythm, tachycardia and bradycardia can all be seen with PEA. Performing a pulse check after a rhythm/monitor check will ensure that you identify PEA in every situation. Pulseless electrical activity usually has an underlying treatable cause. The most common cause in emergency situations is hypovolaemia.

Danger

Prior to commencing BLS personnel should consider safety and the risks involved.

Response

Check for response of a collapsed client by giving a loud, simple command. Stand behind the client’s head and ask the client if they can hear you, or use tactile stimulation of the client to determine if they are conscious or unconscious.

Conscious—responds to verbal commands or by moving.

Unconscious—does not respond to verbal commands, does not move.

Airway

Manoeuvres to reduce the risk of airway obstruction in the unconscious or unresponsive client include:

Clinical Scenario Box 42.1

If you saw the rhythm below after defibrillation, how would you determine if it is pulseless electrical activity?

The mouth should be opened and turned slightly downwards to allow foreign material to drain. Use the finger sweep using a hooking action or give suction if solid material is visible in the oropharynx of an unconscious client. The client may be turned on their side if the airway needs to be cleared.

Breathing

Look, listen and feel for 10 seconds to assess for breathing:

• Look for chest movement including rise and fall of the chest. Is it equal?

• Listen for breath sounds including, wheezing, gurgling. Can you hear breath sounds in all areas of the lungs?

If a client is not breathing normally and is unresponsive, CPR should be commenced with 30 chest compressions followed by 2 breaths, and continued with a ratio of 30:2.

Circulation

If the client is unresponsive and not breathing normally commence CPR.

The person performing chest compressions should:

• Position themselves with knees apart, shoulders above the compression area and elbows straight. Use pressure from body movement rather than the arms to reduce the chance of arm and neck injuries when performing chest compressions (ILCR 2005)

• Note placement for resuscitation—ideally the client is placed supine on a firm surface.

The Australian & New Zealand Resuscitation Council (2010a) recommends that:

• Hands should be placed on the lower half of the sternum with the heel of the hand in line with the nipples in the centre of the chest with the other hand on top

• Compression beyond the lower limit of the sternum should be avoided. Compression applied too high is ineffective and if applied too low may cause regurgitation and/or damage to internal organs.

Rate of compressions

Rescuers should minimise interruptions of chest compressions and maintain a rate of 100 compressions per minute. If rescuer is unable or unwilling to do rescue breathing, then they should only do chest compressions.

To avoid fatigue interfering with the delivery of adequate chest compressions:

• Ensure frequent rotation of personnel participating in CPR (every 2 minutes)

• Continue this management until circulation returns or the decision to stop resuscitation is made by the resuscitation team leader (ARC & NZRC 2010a).

See Table 42.3.

|

Australian Resuscitation Council Guideline 8 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation – Dec 2010. Available from: www.resus.org.au

DEFIBRILLATION WITH THE AUTOMATED EXTERNAL DEFIBRILLATOR

The automated external defibrillator (AED):

• Automatically prompts the user regarding intervention

• Automatically analyses the heart rhythm

• Advises and prompts the user to deliver a shock only if needed.

The AED delivers an electrical charge to the client at either 150 J or 200 J, depending on the brand of defibrillator (see Clinical Interest Box 42.3). Some AEDs have a manual override feature allowing responders with greater skill (e.g. critical care trained staff) to have more control over defibrillation. The AED should be connected to the client once they are determined to be unconscious, not breathing normally and show no signs of life (ARC & NZRC 2010b).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 42.3

The use of AEDs by trained lay and professional responders is recommended to increase survival rates in victims with cardiac arrest. Check local organisation policy regarding AED training, as usually annual training with demonstration of knowledge and skills assessment is a requirement. Please note the ARC & NZRC Guideline 11.4 (2010) states that ‘AED use should not be restricted to trained personnel as the use of AEDs by individuals without prior formal training can be beneficial and may be life saving’.

Preparation of skin prior to pad placement

• Ensure the surface of the client’s skin is dry

• Remove chest hair if required

• Do not delay defibrillation if shaving equipment is not available

Placement of the pads

When applying AED pads (Fig 42.4):

• Remove dressings where pads are placed

• Avoid placing pads over implantable devices, e.g. cardiac pacemaker. If there is an implantable device the defibrillator pad should be placed at least 8 cm from the device

• Do not place AED electrode pads directly on top of a medication patch because the patch may block delivery of energy and cause small burns to the skin. Remove medication patch and wipe the area before attaching the electrode pad

• In large-breasted women the left electrode or paddle may be placed lateral to or underneath the left breast (ARC & NZRC 2010b).

Defibrillator safety

AED instructions

• Always call ‘stand clear’ and visually check all personnel are clear prior to discharging the defibrillator

• Do not discharge paddles into the air

• Do not touch the client during defibrillation

• When a shock is delivered the client will usually jump as a consequence of the electrical energy passing through the body and the operator should take care to avoid flailing arms or legs

• Oxygen masks and nasal cannula should be placed a least 1 m away from the client

• Ensure free-flowing oxygen is moved at least 1 m from discharge

• Ensure the client is not near inflammable fluids, fumes or chemicals that could ignite

• Ensure any fluids or water are not present. Dry the client’s chest if necessary as contact with fluid may conduct a shock (Mcmahon-Parkes et al 2009).

If signs of life—including return of a palpable pulse—are evident, successful resuscitation has occurred (at least temporarily) and post-resuscitation care can begin.

POST-RESUSCITATION CARE

Resuscitation does not stop after the return of a spontaneous circulation. Airway and breathing must be maintained and the blood pressure restored. Hypoxic brain injury, myocardial injury or subsequent organ failure are the predominant causes of morbidity and mortality after cardiac arrests (Nolan et al 2008).

Immediate post-resuscitation care should include an ABCDE assessment with the recording of vital signs, and a 12-lead ECG. The medical officer will order a chest x-ray and a full blood screen and any other specific investigations necessitated by the client’s condition (Spearpoint 2008).

Initial objectives of post-resuscitation care

Initial objectives of post-resuscitation care are to:

• Optimise cardiopulmonary function and systemic perfusion, especially perfusion to the brain

• Continue care in an appropriately equipped critical care unit

• Try to identify the precipitating causes of the arrest

• Institute measures to prevent recurrence

• Institute measures that may improve long-term, neurologically intact survival.

The post-resuscitation client is likely to develop electrolyte abnormalities that may be detrimental to recovery. The following investigations may be requested by medical staff. After successful resuscitation you may be required to assist in the following processes, as guided by the registered nurse:

• Serum electrolytes: hypo/hyperkalaemia and other metabolic disorders including acidosis and disturbances of magnesium, phosphate and calcium (to treat and prevent further cardiac arrhythmias)

• Arterial blood gases: hypocapnia can lead to cerebral ischaemia after cardiac arrest

• Electrocardiogram (ECG): to monitor rhythm and myocardium damage

• Blood glucose levels: strong association between high blood glucose after resuscitation from cardiac arrest and poor neurological outcome (Deakin et al 2010)

• Transfer of the client to the special care unit if appropriate

• Consultation for friends and relatives with medical personnel to discuss the event

• Offer pastoral care or services of social worker

• The client should be examined for resuscitation related injuries, e.g. rib fractures.

Emotional care for client and friends

Nursing skills are important in helping family/significant others to understand and come to terms with a resuscitation event. Similarly, the conscious, recovering client may need help in understanding what has happened to them, the immediate consequences and their future. Nurses are often the providers of skilful, appropriate care and support to clients (Kramer-Johansen et al 2007a).

IN HOSPITAL CODE DOCUMENTATION

Nurses play an important part in ensuring accurate documentation of the account of resuscitation events. When situations arise that compromise client care, nurses must be prepared to initiate and submit critical incident reports. As with all critical situations, resuscitation events require precise recording of events, processes, interventions and care delivered (Spearpoint 2008).

Documentation

The role of documenter/scriber should be assigned to a staff member who is familiar with the data needed and how to obtain it. For example, the documenter may need to request that, as any medication is administered by IV push to the client, the provider announces when it is ‘in’ so that the time documented is accurate. The documenter should have no other role during the resuscitation so that full attention can be given to collecting the data and following the multiple interventions that often occur simultaneously. It has been suggested that the documenter have a designated position at the client’s bed so that all providers will know where to target their information (Jones & Miles 2008).

The rationale for documentation is that it:

• Provides information that can guide continuing care for the client

• Helps to answer questions the family may have about the event

• Assists the institution to know if resuscitation care has been provided according to current standards

• Identifies quality issues so they can be investigated in a timely manner

• Provides aggregate data that can be used to identify variances of concern and as the base for continuous quality improvement efforts

• Provides information to guide resource allocation related to personnel, equipment and supplies used during resuscitations

• Helps to identify learning needs of staff

• Provides the data to answer research questions

• Can reduce the risk of medical litigation (Peberdy et al 2007).

Overcoming barriers to accuracy of in-hospital cardiac arrest documentation

Nurses play an important part in ensuring accurate documentation of the course and nature of resuscitation events. Document the incident management, medications and outcomes (as per hospital procedures and policies). When situations arise that compromise client care, nurses must be prepared to initiate and submit critical incident reports. The nurse team leader or delegate of the ward initiating the code blue event is responsible for ensuring all forms are completed accurately (these will depend on the healthcare facility’s procedures and policies).

Suggestions for documentation

Most hospitals will have a template with guidelines for documentation. The record should include the following:

2. Times of arrest, initiation of CPR, defibrillation and initiation of ALS

3. Doses and routes of administration of drugs

4. Sequential cardiac monitoring with correlation with client’s status, therapy and responses

6. Special procedures such as airway support, chest drains or external cardiac pacing

7. Vital signs and client’s response to any interventions

8. Client’s status and disposition at the end of resuscitation.

Suggested data elements for collection can be divided into three categories of variables:

• Client variables, e.g. age, gender, witness/unwitnessed, location of event, date/time of event, comorbidities, any allergies

• Event variables, e.g. initial rhythm, essential interventions, event times

• Outcome variables, e.g. return of spontaneous circulation (for at least 20 minutes), discharge alive from the hospital, neurological status at discharge, length of stay.

STAFF DEBRIEFING

Debriefing is a process to help people use their abilities to overcome the effects of critical incidents and should be performed within 24 hours post trauma; ideally at the end of the shift. Debriefing allows all personnel involved in the critical event to voice their concerns and reflect on the incident.

MANAGING SPECIFIC EMERGENCY SITUATIONS

Shock

Shock is described as a life-threatening condition a result of an imbalance between oxygen supply and demand, and is characterised by hypoxia and inadequate cellular function that lead to organ failure and potentially death (Justice & Baldisseri 2006). Shock occurs when the circulatory system is no longer able to complete one of its essential functions, such as providing oxygen and nutrients to the cells of the body or removing subsequent waste. The result is inadequate tissue perfusion (Cottingham 2006; Justice & Baldisseri 2006), which triggers a cascade of events. Shock has many causes, including sepsis, cardiac pump failure, hypovolaemia and anaphylaxis (Justice & Baldisseri 2006), and is classified into several types.

Early signs of shock

Compensatory stage

When the client starts to experience a threat to circulation, this threat starts a chain of responses that are intended to maintain a good circulation. These changes are referred to as the compensatory mechanisms as they are designed to compensate for a problem with circulation that has developed. A client who has an effective compensatory response to an insult of circulation can appear quite well; however, the client may be suffering a serious circulatory problem. It is the signs of compensation that alert the nurse to the fact that the client may be in shock (see Clinical Interest Box 42.4). All health professionals caring for clients potentially at risk of shock should aim to identify and correct shock during this compensatory phase (Garretson & Malberti 2007).

Late signs of shock

Decompensatory stage

The period of compensation provides the body with the opportunity to correct itself. In addition to this, this period of compensation provides health professionals with an opportunity to intervene. If this opportunity is not recognised, or the condition causing the shock is severe, the disease can outstrip the body’s ability to compensate and signs of circulatory failure will occur. When this happens, the person is said to have decompensated (see Clinical Interest Box 42.5). Late decompensation is normally easily recognised, as the client deteriorates rapidly (Garretson & Malberti 2007).

Recognising the client in shock

Traditionally, the presence of a low blood pressure was a sign that the client was in shock; however, low blood pressure is a very late sign of shock and, as previously mentioned, it is a sign that the client is starting to deteriorate. Many changes can be seen before a client’s blood pressure becomes low and it is these signs you must watch for if you are to accurately recognise the client in the early stages of shock.

Managing the client in shock

Although the different types of shock require different approaches, the general management of the client in shock should follow the ABC (airway, breathing and circulation) of resuscitation. After securing the airway, probably one of the most important interventions that ward staff can initiate in a spontaneously breathing client is to administer high-concentration oxygen through a non-rebreathe mask (National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence 2007).

Management in all types of shock includes the following:

• Vasoactive medications (a class of medications used to increase the blood pressure)

• Maintaining a patent airway and adequate ventilation

• Promoting restoration of blood volume; administering fluids and blood replacements as ordered

• Administering medications as ordered

• Minimising factors that contribute to shock

• Maintaining continuous assessment of the client

• Providing psychological support: reassuring the client to relieve apprehension and keep family members/significant others informed

It is important to remember to ensure safe administration of ordered fluids and medications, documentation of their administration and evaluation of the effects. Monitor the client for signs of complications and response to treatment. Oxygen is administered to increase the amount of oxygen carried by the available haemoglobin in the blood.

CARDIAC EMERGENCIES

Any number of factors can disrupt the normal cardiac excitation process, resulting in arrhythmic contractions. Such factors include disease, metabolic and electrolyte imbalances, abnormal autonomic influence on the heart, toxicity to other drugs (e.g. digitalis) and myocardial ischaemia and infarction (Myerburg et al 2001).

Angina

Angina occurs when the coronary arteries become seriously narrowed by disease and the supply of oxygenated blood to the heart becomes insufficient for the increased oxygen needed (Patton & Thibodeau 2012).

Manifestations of angina

Clients often describe the pain as constricting, squeezing or suffocating, usually occurring after exercise. Angina can also be brought on by exposure to cold or emotional stress and is often of a short duration.

Initial management

• Call for assistance and reassure the client

• Administer supplemental oxygen if the client is breathless, hypoxaemic or shows signs of heart failure and shock. Application of oxygen also assists with pain relief caused by inadequate oxygen and blood flow through the spasming coronary artery. Pulse oximetry should be used as a guide to administering oxygen therapy (ARC & NZRC 2011).

• Request or assist the registered nurse or doctor with gaining IV access if not already established

• Administer prescribed morphine intravenously to relieve pain. Document effectiveness of pain relief

• Administer dispersible aspirin (instruct the client to chew tablet)

Myocardial infarction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a sudden loss of blood supply to an area of the heart, causing permanent heart damage or death. There are different types of AMI, classified by the location in the heart where the infarct occurs. Blood flow to the myocardium may be obstructed by atherosclerosis or thrombus formation (coronary occlusion). Damage occurs to the heart muscle when blood supply in the coronary arteries is blocked (Patton & Thibodeau 2012).

Manifestations of myocardial infarction

Clients can often confuse the pain with indigestion, as it ranges from discomfort to unbearable. The pain is often described as crushing, squeezing, tightness, aching, constricting or heavy, and is frequently around the central chest area, but may radiate to the back, shoulder, neck, jaw and arm. The client may have cool, pale and clammy skin, an early sign of shock. One of the significant differences between angina and a myocardial infarction is that medication or rest does not relieve it (Zafari et al 2011).

Management of myocardial infarction

Emergency management of myocardial infarction includes:

• Keeping the client still and providing reassurance

• Obtaining information about the client’s condition

• Assisting with gaining patent IV access

• Assisting with prescribed medication

• Retrieving emergency equipment—emergency trolley including AED

• Being prepared to perform CPR if there are no signs of life following the algorithm for BLS.

When stabilised the client will be transferred to one of the following: catheter lab for angiogram or ICU/CCU for further management.

Hypertensive crisis

A hypertensive crisis is a severe, sudden elevation in blood pressure that is accompanied by progressive or impending organ damage including irreversible injury to the brain, heart or kidneys. The brain is particularly vulnerable to the effects of severe hypertension. Extremely high BP—greater than 180/110 mmHg—damages blood vessels; the vessels become inflamed and may leak fluid or blood into the brain, leading to stroke and, along with it, lasting disability (National Heart Foundation of Australia 2008).

Remember: hypertensive crisis is not an isolated BP reading, but a clinical state and it is not necessary for the client to have a systolic BP >180 mmHg.

Clients at risk of experiencing a hypertensive crisis include:

• Clients with primary hypertension—a condition in which the cause of high blood pressure is unknown

• Clients with secondary hypertension—high blood pressure that accompanies conditions such as renal disease, cardiovascular disease and sleep apnoea.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms include headache, dizziness, syncope, numbness, weakness, blurred vision, anginal pain, palpitations, peripheral oedema, fatigue and nose bleed.

Nursing interventions

• Take a set of vital signs including blood pressure measurement on both arms

• Document and report your findings immediately to a senior staff member

• Assist with gaining patent IV access if not already established as the client will require a fast-acting IV antihypertensive medication.

Cardiac monitoring should be in place to monitor the client closely. For this reason the client is in most cases transferred to the intensive care environment for invasive blood pressure monitoring using an arterial line. You may be required to assist the registered nurse to prepare the client for transfer to ICU. Continue to measure, record and report vital signs to ensure that the blood pressure is not reduced too quickly. The aim is to reduce the blood pressure by about 25% in the first hour. This is to ensure that the client physiologically tolerates the reduction in blood pressure—a sudden reduction may compromise the client (Marik & Varon 2007).

Asthma

Clients with asthma will have airways that narrow in response to triggers making it harder for them to breathe.

Three main factors cause the airways to narrow:

• The inside lining of the airways becomes red and swollen (inflammation)

• Extra mucus (sticky fluid) may be produced, which can block up airways

• Muscle around the airways tightens. This is called bronchoconstriction.

In the hospital environment, a client may be exposed to a number of different chemicals and be unaware that this may trigger an asthma attack.

Signs and symptoms

A client experiencing an asthma attack may exhibit wheezing, chronic coughing, shortness of breath, chest tightness and anxiety.

If the attack is life threatening, the person may demonstrate trouble focusing or talking, nasal flaring and cyanosis.

Nursing interventions

• Think DRABC—client may need supplemental oxygen

• You may be asked to perform ongoing observation—remain calm and reassure the client

• Measure and document vital signs with continuous pulse oximetry monitoring

• Alert the RN to any unusual findings of respiratory assessment

• You may be instructed to administer nebulised medications such as Ventolin (salbutamol) and/or Atrovent (ipratropium). Both are used to treat bronchospasm

Seizures

A seizure is a sudden surge of electrical activity in the brain that usually affects how a person feels or acts for a short time. It is an event characterised by a sudden, excessive and disorderly (abnormal) discharge of electrons in the brain that may be accompanied by an abrupt alteration in motor and sensory function and level of consciousness.

Seizures are not a disease in themselves. Instead, they are a symptom of many different disorders that can affect the brain. Some seizures can barely be noticed, while others are totally disabling (Berg & Scheffe 2011).

• Cerebral hypoxia (breath holding, carbon monoxide poisoning, anaesthesia)

• Cerebrovascular accident (infarct or haemorrhage)

• Convulsive or toxic agents (lead, alcohol)

• Alcohol and drug use withdrawal

• Head injury (highest incidence is found in young adults)

• Infection (acute or chronic)

• Metabolic disturbances (diabetes mellitus, electrolyte imbalances)

• Degenerative disorders (senile dementia) (Berg et al 2010).

Signs and symptoms

There are six types of generalised seizures:

1. Grand mal/tonic–clonic (loss of consciousness with generalised body stiffening followed by violent jerking)

2. Absence (a short loss of consciousness with few or no symptoms)

3. Myoclonic (sporadic jerks, usually on both sides of the body)

4. Clonic (repetitive rhythmic jerks involving both sides of the body)

5. Tonic (sudden stiffening of the body)

6. Atonic (sudden general loss of muscle tone which often results in a fall).

Nursing interventions

If you suspect your client is having a seizure, stay with the client, and call for help.

Initial nursing management

• Position the client to avoid aspiration or inadequate oxygenation

• If possible, a soft oral airway can be placed (do not force teeth apart)

• Suction and O2 must be available

• Monitor respiratory function with ongoing pulse oximetry

• Note the time the seizure started, and what body part it is affecting, with the type of movement involved

• Loosen any restricting clothing, protect the client from harming themself with pillows, bed rails. Remove any furniture from the area but do not restrict the movement of their limbs as this may cause musculoskeletal damage

• Place the client in the recovery position if possible as this will assist the tongue to return to its front-forward position and will also allow accumulated saliva to drain from the mouth. Apply supplemental oxygen and have suction ready.

Post-seizure care of the client

• Provide adequate ventilation by maintaining a patent airway

• Suction secretions if necessary to prevent aspiration

• Allow the patient to sleep post seizure

• On awakening, orient the client to what has occurred

• Provide reassurance as this can be a very distressing event

• Assist the registered nurse or medical officer to gain IV access

• Frequent monitoring of neurological status using the Glasgow Coma Scale, including vital signs, must be documented and any changes reported immediately

• Monitor glucose (hyperglycaemia followed by hypoglycaemia is common)

• Treat hyperthermia (occurs often with status epilepticus) aggressively.

Summary

The enrolled nurse requires the skills and knowledge to respond quickly and effectively in a variety of emergency situations, to be an effective member of a team and to work efficiently in a stressful environment. The enrolled nurse, as an integral member of the healthcare team, has a duty of care to deliver care that is holistic, including to the family and significant others. Nurses care for an increasing percentage of clients with complex problems who are likely to be or become seriously ill during their hospital stay. The basic requirement is always thorough client assessment, accurate measurement and recording of vital signs and timely reporting of any changes in the client’s condition, no matter how subtle the changes may appear to be. The effectiveness of handover tools such as ISOBAR ensures that all relevant information is communicated to all parties involved efficiently and effectively.

1. You are working in the medical–surgical ward and are about to finish your morning shift. You decide to do a final check to ensure you have completed all your clients’ charts when you discover one of your clients, Mr Lynch, collapsed on the floor in his room. When you enter the room you notice the following:

2. Mr Lynch’s medical history includes hypercholesterolaemia and hypertension; he had complained earlier in the day that he ‘felt dizzy’ when he got up to go to the toilet. There is no evidence in his progress notes that his concerns have been addressed or investigated. His admission notes state that he was admitted the previous day for stabilisation of his blood pressure. Mr Lynch has not had his vital signs measured since 0600 hrs that morning.

References and Recommended Reading

ACT Health. Policy: Modified Early Warning Scores (Early Recognition of the Deteriorating Patient Project Team). Available: http://health.act.gov.au/c/health?a=dlpubpoldoc&document=756, 2007.

Aldrich R, Duggan A, Lane K, et al. ISBAR revisited: identifying and solving barriers to effective clinical handover in inter-hospital transfer: final project report. Newcastle: Hunter New England Health, 2009.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). Recognising and responding to clinical deterioration: background paper. Available: www.health.gov.au/internet/safety/publishing.nsf/Content/AB9325A491E10CF1CA257483000C9AC4/$File/BackgroundPaper-2009.pdf, 2009.

Australian Resuscitation Council and New Zealand Resuscitation Council. Guideline 8 Cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Available: www.resus.org.au/policy/guidelines/index.asp, 2010.

Australian Resuscitation Council and New Zealand Resuscitation Council. Guideline 11.4 Electrical therapy for adult advanced life support. Available: www.resus.org.au/policy/guidelines/index.asp, 2010.

Australian Resuscitation Council and New Zealand Resuscitation Council. Guideline 11.5 Electrical therapy for advanced life support. Available: www.resus.org.au/policy/guidelines/section_11/electrical_therapy_for_aals.htm, 2010.

Australian Resuscitation Council and New Zealand Resuscitation Council. Guideline 14.2 Acute coronary syndromes: initial medical therapy. Available: www.resus.org.au/policy/guidelines/index.asp, 2011.

Berg AT, Scheffe IE. New concepts in classification of the epilepsies: Entering the 21st century. Epilepsia. 2011;52(6):1058–1062.

Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, et al. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia. 2010;51(4):676–685.

Bright D, Walker W, Bion J. Clinical review: Outreach—a strategy for improving the care of the acutely ill hospitalized client. Critical Care. 2004;8:33–40.

Buist M, Bernard S, Nguyen TV, et al. Association between clinical abnormal observations and subsequent in-hospital mortality: a prospective study. Resuscitation. 2004;62:137–141.

Cioffi J, et al. ‘Clients of concern’ to nurses in acute care settings: a descriptive study. Australian Critical Care. 2009;22(4):178–186.

Cioffi J, Salter C, Wilkes L, et al. Clinicians’ responses to abnormal vital signs in an emergency department. Australian Critical Care. 2006;19:66–72.

Cottingham CA. Resuscitation of traumatic shock: A hemodynamic review. Advanced Journal of Critical Care. 2006;17(3):317–326.

Day BA. Early warning system scores and response times: an audit. Nursing in Critical Care. 2003;8(4):156–164.

Eather B (2006) St George Hospital Modified Early Warning Score Policy

European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation. Section 2. Adult basic life support and use of automated external defibrillators. Available: www.erc.edu/index.php/guidelines_download_2005/en/, 2005.

Fuhrmann L, Lippert A, Perner A, et al. Incidence, staff awareness and mortality of clients at risk on general wards. Resuscitation. 2008;77(3):325–330.

Garretson S, Malberti S. Understanding hypovolaemic, cardiogenic and septic shock. Nursing Standard. 2007;50(21):46–55.

Goldhill DR, McNarry AF. Physiological abnormalities in early warning score are related to mortality in adult clients. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2004;92(6):882–884.

Harrison GA & Jacques T (2006) Summary of GMCT guidelines for in-hospital clinical emergency response systems for medical emergencies. GMCT CERS Working Group. Greater Metropolitan Clinical Taskforce, Sydney

Hillman K, Bristow PJ, Chey T, et al. Antecedents to hospital deaths. Internal Medicine Journal. 2001;31:343–348.

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCR). Part 2: Adult basic life support. Resuscitation. 2005;67:187–201.

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCR). Recommended Guidelines for Monitoring, Reporting and Conducting Research on Medical Emergency Team, Outreach, and Rapid Response Systems: An Utstein-Style Scientific Statement: A Scientific Statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation. 2007;116(21):2481–2500.

Jones PG, Miles L. Overcoming barriers to in-hospital cardiac arrest documentation. Resuscitation. 2008;76(3):369–375.

Justice JR, Baldisseri. Early recognition and treatment of non-traumatic shock in a community hospital. Critical Care. 2006;10(2):307.

Kause J, Smith G, Prytherch D, et al. A comparison of antecedents to cardiac arrests, deaths and emergency intensive care admissions in Australia and New Zealand and the United Kingdom—the ACADEMIA study. Resuscitation. 2004;62:275–282.

Kramer-Johansen J, Edelson DP, Losert H, et al. Uniform reporting of measured quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Resuscitation. 2007;74(3):406–417.

Malmivuo J, Plonsey R. Bioelectromagnetism—Principles and Applications of Bioelectric and Biomagnetic Fields. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Mancini ME, Soar J, Bhanji F, et al. Part 12: Education, implementation, and teams: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Circulation. 2010;122(16 Suppl 2):S539–S581.

Marik PE, Varon J. Hypertensive crises: challenges and management. Chest. 2007;131(6):1949–1962.

Mcmahon-Parkes K, Moule P, Benger J, et al. The views and preferences of resuscitated and non-resuscitated clients towards family-witnessed resuscitation: a qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46(2):220–229.

Mikos K. Monitoring handoffs for standardization. Nurse Manager. 2007;38(12):16–20.

Moule P, Albarran JW. Practical Resuscitation. Recognition and Response. Melbourne: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

Myerburg RJ, Kloosterman EM, Castellanos A, Recognition and treatment of cardiac arrhythmias and conduction disturbances. Fuster V, et al. Hurst’s the Heart, 10th edn., New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001.

National Heart Foundation of Australia. Guide to Management of Hypertension 2008: Updated August 2010. Available: www.heartfoundation.org.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/HypertensionGuidelines2008to2010Update.pdf, 2008.

National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Acutely Ill Clients in Hospital; Recognition of and response to Acute Illness in Adults in Hospital. London: NICE, 2007.

Nolan JP, Soar J. Post resuscitation care—time for a care bundle? Resuscitation. 2008;76:161–162.

Nurmi J, Harjola VP, Nolan J, et al. Observations and warning signs prior to cardiac arrest. Should a medical emergency team intervene earlier? Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2005;49:702–706.

Patton KT, Thibodeau GA. Anatomy and Physiology, 8th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2012.

Peberdy MA, Cretikos M, Abella BS, et al. Recommended guidelines for monitoring, reporting, and conducting research on medical emergency team, outreach, and rapid response systems: an Utstein-style scientific statement: a scientific statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian Resuscitation Council, New Zealand Resuscitation Council) et al. Circulation. 2007;116:2481–2500.

Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58(3):297–308.

Resuscitation Council (UK). Advanced Life Support. Available: www.resus.org.uk, 2011.

Royal College of Nursing Australia (RCNA). The Role of Nurses in the Management of Cardiorespiratory Arrest. Canberra: RCNA, 2006.

Spearpoint K. Resuscitating patients who have a cardiac arrest in hospital. Nursing Standard. 2008;23(14):48–57.

Subbe CP, Kruger M, Rutherford P, et al. Validation of a Modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. Quality Journal of Medicine. 2001;94:521–526.

Sunde K, Jacobs I, Deakin CD, et al. Part 6: Defibrillation: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation. 2010;81(Suppl 1):e71–e85.

Zafari AM, Afonso LC, Aggarwal K, et al. Myocardial infarction. Available: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/155919-overview, 2011.

Australian Resuscitation Council, www.resus.org.au/.

New Zealand Resuscitation Council, www.nzrc.org.nz/.