Documentation

Documentation is defined as anything written or printed that is used to furnish evidence or information that is legal or official. Effective documentation reflects the quality of care and provides evidence of each healthcare team member’s accountability in the delivery of that care. Documentation is at the very core of who we are as nurses (Yocum, 2002:59). Nursing documentation comprises all written and/or computerised recordings of relevant data made by nurses to document care given or to communicate information relevant to the care of the particular client (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2002, 2006).

Today, information about clients is conveyed in various ways. However, all records contain the following fundamental information:

• client identification and demographic data

• record of informed consent for treatment and procedures

• nursing diagnoses or problems

• nursing or multidisciplinary care plan

• clinical pathways and any variance from the norm

• record of nursing care, treatment and evaluation

• medical and healthcare professionals’ progress notes

• reports of physical examinations

• reports of diagnostic studies

Purposes of records

A record is a valuable source of data and is used by all members of the healthcare team. Professional documentation promotes (ACT Nursing and Midwifery Board, 2010):

• compliance with professional competency standards

• effective communication of client health information

• an accurate account of patient problems, assessment, care planned and evaluated

• improved early detection of problems and changes in health status

Communication

The record is a means by which healthcare team members communicate contributions to the client’s care, including individual therapies, client education and use of referrals for discharge planning. The plan of care should be clear to anyone reading the chart. When a staff member is caring for a client and refers to a client’s notes, the record should communicate the measures needed to maintain continuity and consistency of care.

Financial reimbursement

The client care record is a document that shows the extent to which healthcare agencies should be reimbursed for services. DRGs have become the basis for establishing reimbursement for client care. Detailed recording helps in establishing codable diagnoses that are used to determine a DRG. The nurse’s contribution to documentation can help clarify the type of treatment a client receives. When client charges exceed the length of stay allowed for a particular DRG, appropriate documentation is essential to justify the additional time and cost.

Education

Students of nursing and other healthcare-related disciplines use these records as educational resources. A client’s record contains a variety of information, including diagnoses, signs and symptoms (clinical features) of disease, successful and unsuccessful therapies, diagnostic findings and client behaviours. An effective way to learn the nature of an illness and the individual client’s response to it is to read the client care record. No two clients have identical records; however, patterns of information can be identified in records of clients who have similar health problems. With this information, students learn the patterns to look for in various health problems and become better able to anticipate the type of care required for a client.

How do you rate your ability to document patient care? What are the learning strategies that you use to improve this skill? Documentation truly is a skill that improves with practice. Some suggestions for improving your documentation can include:

• practice in your university/college setting for the simulated case studies within the course

• having a colleague/fellow student read your documentation and ask you questions about the patient care you have documented

• practising documentation on scrap paper, and having a registered nurse check it before entering it into a patient’s chart

• every time you provide care, while you are undertaking care or immediately after providing care, considering what information needs to be documented—if you are unable to document these immediately, jot them down on scrap paper so you’ll recall them when you document (but always be vigilant of destroying/disposing of your scrap notes appropriately)

• reading through patient charts when you have access to them, noting the entries that give you a clear picture of the patient status/care given and comparing these with unclear entries. What is the difference between them? What lessons can you learn and apply from doing this? This is a form of auditing, and is a great way to learn what to do and what not to do.

Assessment

A client history and baseline nursing assessment is completed when a client is admitted to a nursing care unit. This usually contains biographical data (e.g. age, marital status), method of admission, reason for admission, a brief medical–surgical history (e.g. previous surgeries or illnesses), allergies, current medication (prescribed, over-the-counter and illicit substances), the client’s perceptions about illness or hospitalisation, and a review of health risk factors. A physical assessment of all body systems is either incorporated into the nursing history or included on a separate form.

The record provides data that nurses use to assess, identify, plan and evaluate appropriate interventions for nursing care. Information previously made available by the client should be verified by the nurse to confirm its accuracy.

Before caring for any client, the nurse should refer to the client’s record for information regarding the reason for admission and general health status. The nurse is then able to conduct an individualised assessment of the client, which includes a comprehensive physical assessment, and psychosocial and environmental overview. It is important to note that in some settings the initial client assessment will be undertaken by the nurse; for example, in accident and emergency, in community care and in rural and remote area clinics.

Accurate assessment data generated by each member of the healthcare team provide an overview of the client’s health status. For example, after inspection of a wound, the nurse may conclude that healing is delayed. The record should, if due diligence and accurate recording of findings has occurred, provide much additional information, including the client’s appetite, descriptions of the wound’s previous appearance and laboratory results indicating the presence or absence of infection. Such information can help explain the reasons for and implications of changes in client condition, and should prompt direction and focus of care given by the healthcare team.

Research

Statistical data relating to the frequency of clinical disorders, and complications, the use of specific medical and nursing therapies, recovery from illness and deaths can be gathered from client records. Records are a valuable resource for describing characteristics of the client populations in a healthcare agency. A nurse may use clients’ records during a research study to collect information on certain factors. For example, if a nurse uses a new method of pain control for a group of clients, the records provide data on the clients’ responses to the therapy. Recording entries that describe the type and dose of analgesic medications used and client’s subjective reports of pain relief could be used to evaluate pain-control measures. Nurses may also research records of previously discharged clients to identify nursing care problems. For example, a study to determine the incidence of infection in clients with specific types of intravenous catheters might be performed by means of a chart review. Chart reviews may also be used to research decisions made by health workers or as a measure of their written communication effectiveness. It is important for the nurse to first acknowledge the legal and ethical considerations that apply before using or reproducing any material gathered from client care records in their setting, such as obtaining approval from recognised and appropriate ethics committees and from clients prior to access.

Auditing

A regular review of information in client records provides a basis for evaluation of the quality and appropriateness of care provided in an institution. The ACHS requires hospitals in Australia to establish quality-improvement programs for conducting objective, ongoing reviews of client care. The ACHS imposes standards for information to be included in the client’s record, such as indications that a plan of care is developed with the client as a participant and that discharge planning and client education have occurred. The ACHS requires institutions to establish standards for quality of care. Nurses monitor or review records throughout the year to determine the degree to which quality-improvement standards are met. Deficiencies identified during monitoring are shared with all members of the nursing staff so that corrections in policy or practice can be made. Quality-improvement programs keep nurses informed of standards of nursing practice to maintain excellence in nursing care.

Medical records are also audited to review charges for the client’s care. Auditors from the federal and state governments review records to determine the reimbursement that a client or a healthcare agency receives. Accurate documentation of supplies and equipment that have been used ensures that costs are recovered and that clients receive the care they require.

Legal documentation

Accurate documentation is one of the best defences against legal claims associated with nursing care. The record serves as a description of exactly what happened to a client and who was involved in providing care (Austin, 2006).

Documentation not completed to professional standards places nurses in jeopardy of a negligence claim from the clients in their care. Key areas of documentation that pose a risk of legal action for the nurse are (Forrester and Griffiths, 2005):

• not charting the correct time events occurred

• failing to ensure that information is clear, concise and accurate

Table 14-1 provides guidelines for legally sound documentation. Because a lawsuit may not be filed for years after an incident, documentation may be the crucial evidence protecting the nurse and the facility if legal action is taken (Austin, 2006).

TABLE 14-1 BROAD GUIDELINES FOR RECORDING

| GUIDELINES | RATIONALE | CORRECT ACTION |

|---|---|---|

| Do not erase, apply correction fluid or scratch out errors made while recording | Chart becomes illegible: it may appear as if you were attempting to hide information or deface record | Draw single line through error, write word ‘error’ and initials above it then record note correctly |

| Do not write retaliatory or critical comments about client or care by other healthcare professionals | Statements can be used as evidence for non-professional behaviour or poor quality of care | Enter only objective descriptions of client’s behaviour; client comments should be quoted |

| Correct all errors promptly | Errors in recording can lead to errors in treatment | Avoid rushing to complete charting; be sure information is accurate |

| Record all relevant information | Record must be accurate and reliable | Be certain entry is factual; do not speculate or guess |

| Do not leave blank spaces in nurses’ notes | Another person can add incorrect information in space | Chart consecutively, line by line; if space is left, draw line horizontally through it and sign your name at end |

| Record all entries legibly and in ink | Illegible entries can be misinterpreted, causing errors and lawsuits; ink cannot be erased; records are photocopied and stored on microfilm | Never erase entries or use correction fluid, and never use pencil |

| If order is questioned, record that clarification was sought | If you perform an order known to be incorrect, you are just as liable for prosecution as the doctor is | Do not record ‘doctor made error’. Instead, chart that ‘Dr Smith was called to clarify order for analgesic’ |

| Chart only for yourself | You are accountable for information you enter into chart | Never chart for someone else (exception: if caregiver has left unit for day and calls with information, record accordingly) |

| Avoid using generalised, empty phrases such as ‘status unchanged’ or ‘had good day’ | Specific information about client’s condition or case can be accidentally deleted if information is too generalised | Use complete, concise descriptions of care |

| Begin each entry with date and time, and end with your signature and title | This guideline ensures that the correct sequence of events is recorded; the signature documents who is accountable | Do not wait until end of shift to record important changes that occurred several hours earlier; be sure to sign each entry |

| Use only agency-recognised abbreviations | This reduces the chance of errors as different agencies use different abbreviations | Never use obscure abbreviations |

The law protects information about clients that is gathered by examination, observation, conversation or treatment. Nurses may not discuss a client’s status with other clients or staff uninvolved in the client’s care. Nurses are legally and ethically obligated to keep information about clients’ illnesses and treatments confidential. Only healthcare team members directly involved in care have legitimate access to the records. Clients often request copies of their medical records, and they have the right to read those records. Each institution has policies for controlling the manner in which records are shared. In most situations, clients are required to give written permission for release of medical information. Nurses are responsible for protecting records from all unauthorised readers. This includes hand-over notes, or informal, identifiable notes that nurses make during the day and carry with them to assist in caring for patients.

When nurses and other healthcare professionals have a legitimate reason to use records for data gathering, research or continuing education, appropriate authorisation must be obtained according to agency policy. Nursing students and university teaching staff may be required to present identification indicating that access to the record is authorised. The nurse should know the location of the record at all times. The record is stored by the healthcare agency after treatment ends, and ownership of the record usually resides with the agency.

Guidelines for high-quality documentation and reporting

High-quality documentation and reporting are necessary to enhance efficient, individualised client care. Documentation must have meaning today, tomorrow and in the unforeseen future. One of the difficulties with documentation is that we never know when the document may be required, or under what circumstances (Austin, 2006). High-quality documentation and reporting follow five important guidelines: fact, accuracy, completeness, currency and organisation.

Fact

A record contains descriptive, objective information about what a nurse sees, hears, feels and smells. An objective description is the result of direct observation and measurement. The use of inferences without supporting factual data is not acceptable because they can be misunderstood. The use of words such as ‘appears’, ‘seems’ or ‘apparently’ is not acceptable because they suggest that the nurse did not know the facts. For example, the description ‘The client seems anxious’ does not accurately communicate facts and does not inform another caregiver of the details regarding the behaviours exhibited by the client that led to the use of the word ‘anxious’. The phrase ‘seems anxious’ is a conclusion without supported facts. Documentation needs to clearly explain the nurse’s observations of the client’s behaviours. When recording subjective data, document the client’s exact words within quotation marks. For example, ‘Client states “I feel very nervous and out of control.”’ Any objective findings that are related to the client’s anxiety, such as an increased blood pressure and pulse rate, can also be added.

Accuracy

The use of exact measurements ensures that a record is accurate. The nurse makes descriptions such as ‘Intake, 360 mL of water’ rather than ‘Client drank an adequate amount of fluid’. Measurements are later used as a means to determine whether a client’s condition has changed. Charting that an abdominal wound is ‘5 cm in length without redness, drainage or oedema’ is more accurate than ‘large wound is healing well’. Use of an institution’s accepted abbreviations, symbols and system of measures (e.g. metric) ensures that all staff members will use the same language in their reports and records. Use abbreviations carefully to avoid misinterpretation. To avoid any chance of error, abbreviations are firstly written in their entirety; otherwise terminology can be confusing.

Correct spelling is important and demonstrates a level of competency and attention to detail—misspelling can contribute to serious adverse treatments. Many terms can easily be confused or misinterpreted (e.g. dysphagia or dysphasia), so the nurse needs to understand the impact the documentation can have on client outcomes.

The ACHS EQuIP5 Guideline 1.1.8 (ACHS, 2010) provides an overview of the details care providers must document in the client’s clinical record, including that all entries must be legible, dated and signed with designation. Records need to reflect accountability during the timeframe of the entry. This is best accomplished when nurses chart their own observations and actions. Each entry in a client’s record is identified with the caregiver’s initials or full name and status, such as ‘Julie Smith, RN’. Each time initials are used, the full name and status must also appear on the same page. A nursing student enters full name and educational institution, such as ‘David Jones, SN, UTS’ (SN: student nurse) followed by the university affiliation. The signature holds that the nurse is accountable for information recorded. If information was inadvertently omitted from the record, it is acceptable for nurses to ask colleagues to chart information after they leave work. The entry needs to clearly show what was done and by whom (e.g. ‘At 1630 hours Sam Turner, RN, called and reported that at 1530 hours the client Joseph Podwera was administered the oral contrast solution required for his medical imaging procedure at 1700 hours’).

Should an incorrect entry be made in a client record, the nurse who made the entry must write a subsequent note in the record identifying the error and correcting it. Incorrect information should never be obliterated or made illegible; rather, it must be identified as inaccurate and corrected with a subsequent note that is signed and dated.

Completeness

The information within a recorded entry or a report needs to be complete, containing concise, appropriate and thorough information about a client’s care. Concise data are easy to understand. Clear, succinct recording and reporting give essential information, avoiding unnecessary words and irrelevant detail.

Criteria for thorough communication exist for certain health problems or nursing activities (see Table 14-2). The nurse makes written entries in the client’s medical record, describing nursing care that is administered and the client’s response. An example of a nurse’s thorough note follows:

2000 hours. Client verbalised sharp throbbing pain localised along medial side of right ankle, beginning at approximately 1900 hours after twisting his foot on the stairs. Pain increased with movement 7/10, slightly relieved with elevation 5/10. Pedal pulses equal bilaterally. Right ankle circumference 1 cm larger than left. Ice pack applied. Dr Walker notified at 1920 hours, nil further actions requested. Paracetamol 1 g given for pain at 1920 hours. Client states that pain has reduced to 3/10 at 1955 hours. L Turner, RN.

TABLE 14-2 EXAMPLES OF CRITERIA FOR REPORTING AND RECORDING

| TOPIC | CRITERIA TO REPORT OR RECORD |

|---|---|

| ASSESSMENT | |

| Subjective data | |

| Client behaviour (e.g. anxiety, confusion, hostility) | Onset, behaviours exhibited, precipitating factors |

| Objective data (e.g. rash, swelling, breath sounds) | Onset, location, description or quality of findings, aggravating or relieving factors |

| NURSING INTERVENTIONS AND EVALUATION | |

| Treatments (e.g. enema, bath, dressing change) | Time administered, equipment used (if appropriate), client’s response (objective and subjective changes) compared with previous treatment; e.g. ‘client denied pain during dressing change’ or ‘client reported severe abdominal cramping during enema’ |

| Medication administration | Time administered, preliminary assessment (e.g. pain level, vital signs), client response or effect of medication; e.g. ‘client reports pain level 2 (scale 0–10) 30 minutes after paracetamol was given’, or ‘pruritus and hives developed over lower abdomen 1 hour after penicillin was given’ |

| Client teaching | Information presented, method of instruction (e.g. discussion, demonstration, DVD, booklet), client response, including questions and evidence of understanding such as return demonstration or change in behaviour |

| Discharge planning | Client goals or expected outcomes, progress towards goals, need for referrals |

Currency

Timely entries are essential in the client’s concurrent care (ACHS, 2010). In order to increase accuracy and decrease unnecessary duplication, many healthcare agencies use bedside records, which facilitate immediate documentation of information as it is collected from a client. Activities or findings to communicate at the time of occurrence include the following:

• monitoring of interventions (chest tube observations)

• administration of medications and treatments

• preparation for diagnostic tests or surgery

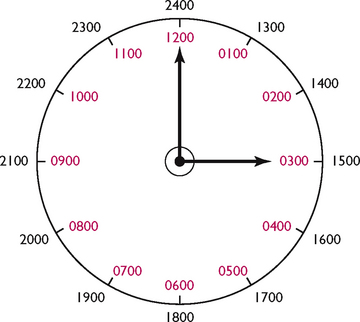

This information is often included in flow-sheets kept at the bedside. Nurses often also keep a worksheet when caring for several clients, making notes as the care occurs to ensure that entries recorded later in the record are accurate, as mentioned when discussing legal requirements affecting patient information. Most healthcare agencies use the 24-hour system, avoiding misinterpretation of a.m. and p.m. times (see Figure 14-1).

Organisation

The nurse communicates information in a logical order. For example, an organised note describes the client’s pain, nurse’s assessment and interventions and the client’s response. To write notes in an organised fashion, the nurse needs to think about the situation and sometimes make notes of what is to be included before beginning to write in the permanent clinical record.

Standards

The ACHS lists the following two criteria as mandatory in their EQuIP5 standards criteria and elements for healthcare standards (ACHS, 2010):

1.1.5 Processes for clinical handover, transfer of care and discharge address the needs of the consumer/patient for ongoing care

1.1.8 The health record ensures comprehensive and accurate information is collaboratively gathered, recorded and used in care delivery.

National competency standards, codes of ethics and professional conduct form practice guidelines and underpin responsibilities for nurses in Australia and New Zealand. All these documents outline broad roles and responsibilities for documentation and reporting (refer to your country’s appropriate standards), and underpin registration and enrolment requirements for nurses. Some organisations also have further detail on how these roles and responsibilities will be enacted by nurses in their organisation.

In Australia, documentation needs to follow ACHS standards and guidelines in order to maintain institutional accreditation and lessen liability. Current standards require that all clients who are admitted to a healthcare institution have an assessment of physical, psychosocial, environmental, self-care, client education and discharge planning needs. In addition, the ACHS stresses the importance of evaluating client outcomes, including the client’s response to treatments, teaching or preventive care. The nursing service department of each healthcare agency selects the method that is used to document client care. The method reflects the philosophy of the nursing department and incorporates the standards of care. Assessment data are recorded to offer to all healthcare team members a database from which to draw conclusions about the client’s problems. Information describing the client’s problems or diagnoses then directs caregivers to choose an appropriate plan of care with nursing therapies. Evaluation of care communicates the client’s status, degree of progress and success in meeting expected outcomes of care.

Types of documentation

Narrative documentation

Narrative documentation is the traditional method for recording nursing care. It is simply the use of a story-like format to document information specific to client conditions and nursing care. Narrative charting, however, has many disadvantages, including the tendency to have repetitious information, be time-consuming and require the reader to sort through much information to locate desired data (Cheevakasemsook and others, 2006).

Problem-oriented medical records

The problem-oriented medical record (POMR) is a method of documentation that places emphasis on the client’s problems. Data are organised by problem or diagnosis. Ideally, each member of the healthcare team contributes to a single list of identified client problems. This assists in coordinating a common plan of care. The POMR has the following major sections: database, problem list, nursing care plan and progress notes.

DATABASE

The database section contains all available assessment information pertaining to the client (e.g. history and physical examination, the nurse’s admission history and ongoing assessment, the dietitian’s assessment, laboratory reports and radiological test results). The database is the foundation for identifying client problems and planning care. The database is revised as new data become available, and accompanies clients through successive hospitalisations or clinic visits.

PROBLEM LIST

After data are analysed, problems are identified and a single list is made. The problems include the client’s physiological, psychological, social, cultural, spiritual, developmental and environmental needs. The problems are listed in chronological order and filed in the front of the client’s record to serve as an organising guide for the client’s care. New problems are added as they are identified. When a problem has been resolved, the date is recorded and it is highlighted or a line is drawn through the problem and its number.

NURSING CARE PLAN

A nursing care plan is developed for each problem by the disciplines involved in the client’s care. Nurses document the plan of care in a variety of formats. Generally, these plans of care include nursing diagnoses/patient problems, expected outcomes and interventions.

PROGRESS NOTES

Healthcare team members monitor and record the client’s problems in the progress notes (see Box 14-3). The information can be expressed in various formats of structured notes. One method is SOAPIE:

S. Subjective data (verbalisations of the client)

O. Objective data (that which the nurse can measure and observe)

A. Assessment (problems identified based on the data)

BOX 14-3 PROGRESS NOTES—EXAMPLES OF DIFFERENT FORMATS

SOAPIE

19/1/2008 Knowledge deficit related to uncertainty regarding surgery

1630 HOURS

S. ‘I’m worried about what it will be like after surgery.’

O. Client asking frequent questions about surgery. Has had no previous experience with surgery. Wife present, acts as a support person.

A. Knowledge deficit regarding surgery related to inexperience. Client also expressing anxiety.

P. Explain routine preoperative preparation, including the purpose of deep-breathing and coughing (DBC) exercises.

I. Provided explanation and teaching booklet on general postoperative care. Demonstrated and explained rationale for DBC exercises.

E. Patient discusses rationale for DBC exercises and general care provided, and demonstrates the exercises correctly.

PIE

P. Knowledge deficit regarding surgery related to inexperience.

I. Explained to client normal preoperative preparations for surgery. Demonstrated DBC exercises. Provided booklet to client on postoperative nursing care.

E. Client demonstrates DBC exercises correctly. Needs review of postoperative nursing care.

FOCUS CHARTING

D. BP in left arm 90/60, client’s skin diaphoretic, client responds to name.

A. Placed client in Trendelenburg’s position, increased IV fluid rate to 100 mL/h per protocol, called Dr Arkin.

R. Client remains responsive, BP in left arm 94/68, 3 min after increasing fluids.

Joseph Page is an 80-year-old admitted with a diagnosis of pneumonia. He complains of general malaise and a frequent productive cough, worse at night. Vital signs are: blood pressure 150/90 mmHg; pulse rate 92 beats per minute; respirations 22 breaths per minute; and temperature 38°C. During your initial assessment he coughs violently for 40–45 seconds without expectorating. His lungs have wheezes and crackles in both bases and are otherwise clear.

In the PIE format, the assessment information is documented on special flow-sheets. The narrative note includes:

The PIE notes are numbered or labelled according to the client’s problems. Resolved problems are dropped from daily documentation after the nurse’s review. Continuing problems are documented daily.

Focus charting or DAR notes include:

D. Data, both subjective and objective

A. Action or nursing intervention

R. Response of the client (i.e. evaluation of effectiveness).

One distinction of focus charting is its movement away from only charting problems, which has a negative connotation. Instead, the notes are structured according to client concerns: a sign or symptom, a condition, a nursing diagnosis, behaviour, a significant event or a change in a client’s condition. Documentation is written in accordance with the nursing process; nurses are encouraged to broaden their thinking to include any client concerns, not just problem areas, and critical thinking is encouraged. Focus charting is easily understood by caregivers and adaptable to most healthcare settings.

Source records

In a source record the client’s chart is organised so that each discipline (e.g. nursing, medicine, social work or physiotherapy) has a separate section in which to record data. One advantage of a source record is that caregivers can easily locate the proper section of the record in which to make entries. Table 14-3 lists the components of a source record. A disadvantage of the source record is that information is not organised by client problems, so that details about a specific problem may be distributed throughout the record. For example, the nurse describes the character of abdominal pain and use of relaxation therapy and analgesic medication in the nurses’ notes. The doctor’s notes describe the progress of the client’s bowel obstruction and the plan for surgery in a separate section of the record. The results of X-ray examinations that show the location of the bowel obstruction are in the test results section of the record. The method by which source records are organised does not show how information from the disciplines is related or how care is coordinated to meet all of the client’s needs.

TABLE 14-3 EXAMPLE OF ORGANISATION OF A TRADITIONAL SOURCE RECORD

| SECTIONS | CONTENTS |

|---|---|

| Admission sheet | Specific demographic data about client: legal name, identification number, sex, age, birth date, marital status, occupation and employer, health insurance, nearest relative to notify in an emergency, religious preference, name of attending doctor, date and time of admission |

| Doctor’s order sheet | Record of doctor’s orders for treatment and medications, with date, time and doctor’s signature |

| Nurse’s admission assessment | Summary of nursing history and physical examination |

| Graphic sheet and flow-sheet | Record of repeated observations and measurements such as vital signs, daily weights and intake and output |

| Medical history and examination | Results of initial examination performed by doctor, including findings, family history, confirmed diagnoses and medical plan of care |

| Nurses’ notes | Narrative record of nursing process: assessment, nursing diagnosis, planning, implementation and evaluation of care |

| Medication records | Accurate documentation of all medications administered to client: date, time, dose, route and nurse’s signature |

| Doctor’s progress notes | Ongoing record of client’s progress and response to medical therapy and review of disease process |

| Healthcare discipline’s records | Entries made into record by all health-related disciplines: radiology, social work and laboratories |

| Discharge summary | Summary of client’s condition, progress, prognosis, rehabilitation and teaching needs at time of dismissal from hospital or healthcare agency |

The nurses’ notes section is where nurses enter a narrative description of nursing care and the client’s response (see Box 14-4).

BOX 14-4 SAMPLE NARRATIVE NOTE

8/6 1100 HOURS

Client states, ‘I’m having a hard time catching my breath.’ Respirations, laboured at 28/min; P, 96; BP, 112/70. Client using intercostal muscles during inhalation. Breath sounds auscultated, crackles over both lower lobes. Chest excursion equal bilaterally. Elevated head of bed to Fowler’s position. Obtained arterial blood gas analysis at 1045 order. Results are pH, 7.34; PCO2, 44 mmHg; PO2, 80 mmHg. Dr Stein called. Applied O2 at 4 L/min per mask as ordered. Remained at bedside to calm client.

The nurse positions Mr Page in a semi-Fowler’s position, encourages increased fluid intake and gives paracetamol 1 g PO as ordered for fever. One hour later the client is resting in bed. Vital signs are: blood pressure 130/86 mmHg, pulse 86 beats per minute, respiration 22 breaths per minute and temperature 37.8°C. The client states he has been able to sleep. His fluid intake has been 200 mL of water.

Use the given information to write a nursing progress note using each of the SOAPIE, PIE and DAR formats.

Charting by exception

Charting by exception is an approach used to streamline documentation. It reduces repetition and time spent in charting. It is a shorthand method for documenting normal findings and routine care based on clearly defined standards of practice and predetermined criteria for nursing assessments and interventions. Clearly defined standards of practice that specify nurses’ responsibilities to clients provide the framework for routine care of all clients. With standards integrated into documentation forms, such as predefined normal assessment findings or predetermined interventions, a nurse need document only significant findings or exceptions to the predefined norms. In other words, the nurse writes a progress note only when the standardised statement on the form is not met. Assessments are standardised on forms so that all caregivers evaluate and document findings consistently.

Because the standard assessments are located in the chart, client data are already present on the permanent record and caregivers have easy access to current data. The assumption with charting by exception is that all standards are met unless otherwise documented. When nurses see entries in the chart, they know that something out of the ordinary has been observed or has occurred. For that reason, when changes in a client’s condition have developed, it is easy to track them.

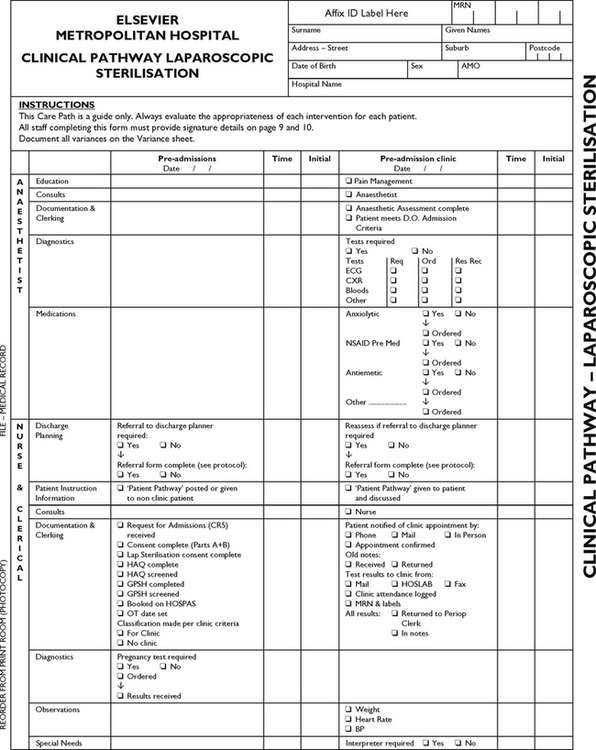

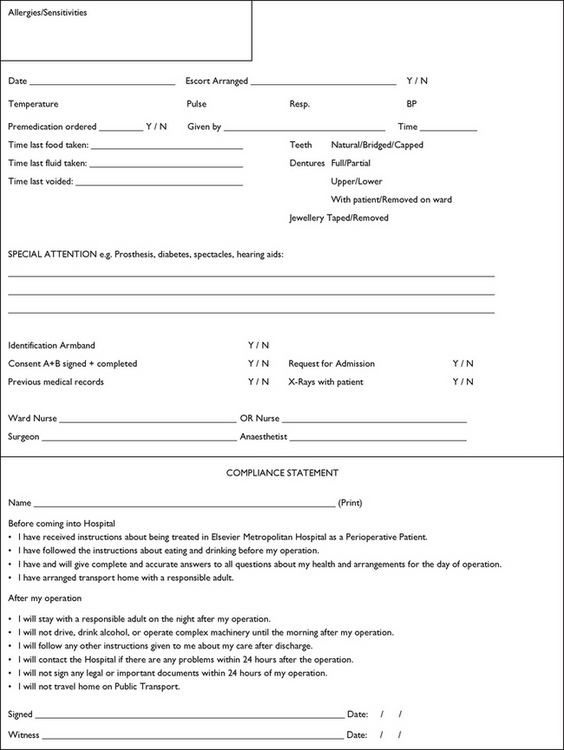

Case management and critical pathways

The case management model of delivering care incorporates a multidisciplinary approach to documenting client care. The standardised plan of care is summarised into critical pathways, for a specific disease or condition. Critical pathways (or clinical pathways, care paths, integrated care pathways or care maps) are multidisciplinary care plans that offer many benefits by focusing on key interventions and expected outcomes within established timeframes. The nurse and other team members such as dietitians, social workers and physiotherapists use the same critical pathway to monitor the client’s progress during each shift.

The aim of critical pathways is to improve the quality of care, client satisfaction and efficiency in the use of resources and to reduce risks (De Bleser and others, 2006). In general, the critical pathway identifies the expected outcomes for each day of care (see Figure 14-2). Any divergence from the stated pathway of care, whether clinical or procedural, is regarded as a variance. Recognition of variances is vital to client outcomes and should be documented in a timely fashion (Sheehan, 2002). A negative variance occurs when the activities on the clinical pathway are not completed as predicted or the client does not meet the expected outcomes. An example of a negative variance is when a client develops pulmonary complications postoperatively, requiring oxygen therapy and monitoring pulse oximetry. A positive variance occurs when a client progresses more rapidly than expected (e.g. use of an indwelling urinary catheter may be discontinued a day early). A variance analysis is necessary to review the data for trends and for developing and implementing an action plan to respond to the identified client problems (see Box 14-5).

FIGURE 14-2 Page 1 of a clinical pathway for laparoscopic sterilisation.

Courtesy Liverpool Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

BOX 14-5 VARIANCE DOCUMENTATION EXAMPLE

A 56-year-old client is on a surgical unit 1 day after cholecystectomy. He is beginning to have an elevated temperature, his breath sounds are decreased bilaterally in the bases of both lobes of the lungs and he is slightly confused. Ordinarily, 1 day after surgery the client should be afebrile with lungs clear. The following is an example of the variance documentation for this client.

23/9/08 1000 HOURS

Breath sounds diminished bilaterally at the bases. T, 38.2; P, 92; R, 24/min; oxygen sat, 84. Daughter states he is ‘confused’ and did not recognise her when she arrived a few minutes ago. Oxygen started at 2 L per standing orders. Will monitor pulse oximetry and vital signs every 15 minutes.

It must also be acknowledged that variance from the clinical pathway may also be related to a client’s comorbidities. These results are unexpected and not accounted for within the normal procedural outcomes, so there will be a reassessment of the use of the pathway as a clinical tool.

Common record-keeping forms

Various forms are available that are specially designed for the type of information nurses generate during their client assessment. The categories within a form are usually derived from institutional standards of practice or guidelines established by accrediting bodies.

Nursing history

A client history form (often referred to as a nursing history) is completed when a client is admitted to a ward. The history form guides the nurse through an assessment of the client’s social and health-related issues. These data then provide the framework for the nurse to develop a comprehensive, holistic approach to planning client care. All care delivered during an admission relies on an accurate initial assessment as the baseline for changes in client progress. Each institution designs a nursing history form differently, based on the standards of practice, philosophy of nursing care and the nursing care delivery system. The data gathered in any initial nursing assessment, however, become the foundation for planning clients’ ongoing management up to and following their discharge.

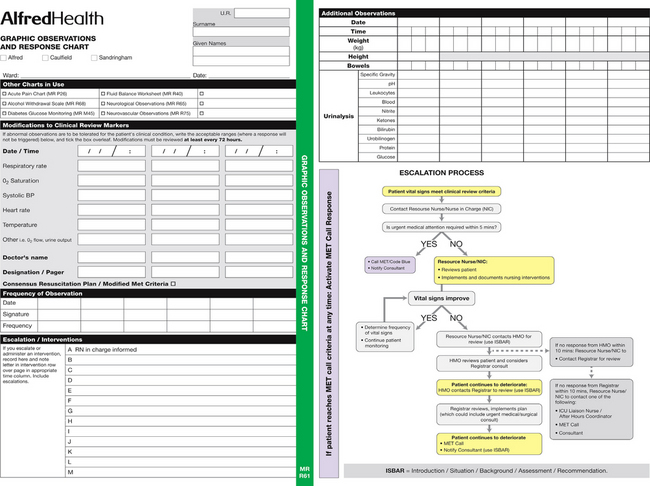

Graphic sheets and flow-sheets

Flow-sheets are forms that allow nurses to assess the client and to document, quickly and effectively, using a coding system, vital signs and routine care, such as bathing, walking, meals and safety and restraint checks (see Figure 14-3). If something on the flow-sheet is unusual or changes significantly, a focus note is needed. For example, if a client’s blood pressure becomes dangerously high, the nurse completes a focus assessment and records this as well as action taken in the progress notes. Flow-sheets provide a quick, easy reference for the healthcare team members in assessing a client’s status. Critical-care and acute-care units commonly use flow-sheets for all types of physiological data (see Box 14-6).

Acuity charting systems or client dependency systems

Staffing patterns can be determined by examining the acuity levels of the clients on a particular nursing unit. The client-to-staff ratios depend on a composite gathering of data in regard to the 24-hour interventions that are necessary for implementing care. Acuity charting requires that staff assign a number scale to interventions, thereby obtaining a numerical level of acuity for each client. For example, an acuity system might rate bathing clients from 1 to 5 (1 is totally dependent, 5 is independent). A client returning from surgery requiring frequent monitoring and extensive care may be listed with an acuity level of 1. On the same continuum, another client awaiting discharge after a successful recovery from surgery has an acuity level of 5.

Standardised care plans

Many institutions have attempted to make documentation easier for nurses with standardised care plans. The plans, based on the institution’s standards of nursing practice, are pre-printed, established guidelines that are used to care for clients who have similar health problems. After a nursing assessment is completed, the nurse identifies the standard care plans that are appropriate for the client. The care plans are placed in the client’s medical record. Modifications can be made in ink to the standardised plans to individualise the therapies. Most standardised care plans also allow the nurse to write in specific goals or desired outcomes of care, as well as the dates by which these outcomes should be achieved.

One advantage of standardised care plans is establishment of clinically sound standards of care for similar groups of clients. These standards can be useful when quality-improvement audits are conducted. Another advantage is education; nurses learn to recognise the accepted requirements of care for clients. The standardised care plans can also improve continuity of care among professional nurses.

The use of standardised care plans is controversial. The major disadvantage is the risk that the standardised plans inhibit nurses’ identification of unique, individualised therapies for clients. When standardised care plans are used in a healthcare facility, the nurse remains responsible for an individualised approach to care. Standardised care plans cannot replace the nurse’s professional judgment and decision making. In addition, care plans need to be updated on a regular basis to ensure that content is current and appropriate.

There is the trend in many hospitals to computerise care plans. With such a system, daily computer-generated care plans are printed and incorporate several nursing diagnoses or problems in a single care plan. Such a system facilitates the process of revision and individualisation of plans. Care facilities using this system will all use slightly different approaches.

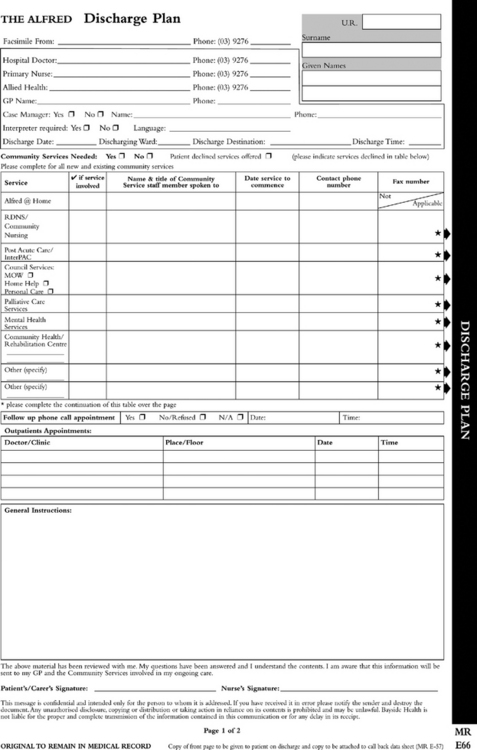

Discharge summary forms

Much emphasis is placed on preparing a client for an efficient, timely discharge from a healthcare institution. A prospective payment system based on DRGs encourages healthcare institutions to be more efficient and to discharge the client as soon as possible. However, it is important to ensure that a client’s discharge results in desirable outcomes.

Ideally, discharge planning begins at admission. Nurses revise the plan as the client’s condition changes. There needs to be evidence of the involvement of the client and family members in the discharge planning process so that the client and family have the necessary information and resources to return home. The planning for discharge may also require the nurse to assess the client’s need of ancillary assistance if the client does not have significant others or an established support system at home. Clients and their significant others also need to be made aware of potential post-discharge complications and any ongoing management they may require, such as follow-up appointments, medication management and emergency numbers.

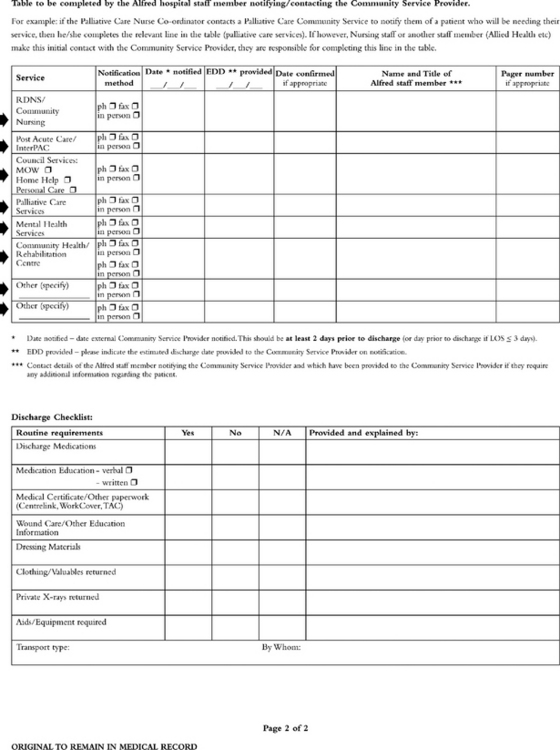

When a client is discharged from institutional care, a discharge summary is prepared by the various members of the healthcare team and given to the client or family, general practitioner, home healthcare, rehabilitation or long-term care agency. Discharge summary forms (see Figure 14-4) make the summary concise and instructive and should be a tool to assist in the ongoing management of the client following discharge.

Several days later, following treatment with intravenous antibiotics, Mr Page is feeling much better and preparations are being made for discharge. He is to take cephalexin 500 mg every 6 hours for the next 10 days, continue to drink extra fluids and get extra rest. Mr Page lives alone. Although he is generally cooperative, he does not like drinking water or taking pills. He is to make an appointment with his doctor for 1 week from today and should call the doctor if he develops symptoms of recurrence.

Write a discharge summary for the nursing care, including any patient education required and discharge instructions for the patient that are concise and instructive.

Home healthcare documentation

Home healthcare continues to grow, with shorter hospitalisations and larger numbers of older adults requiring home healthcare services. Many state governments have specific guidelines for establishing eligibility for home healthcare reimbursement. According to these guidelines, nurse input into the documentation must reflect an accurate assessment and the nurse’s accountability to the client and the taxpayer.

Documentation in the home healthcare system has different implications from those in other areas of nursing. Nurses in this context must have astute assessment skills in order to gather the required information about changes in the client’s healthcare status, as they often work independently and do not have others nearby to validate the patient’s condition or issues that may arise. In addition, documentation systems need to provide the entire healthcare team with the necessary information to be able to work together effectively (see Box 14-7).

BOX 14-7 HOME HEALTHCARE FORMS FOR DOCUMENTATION

The usual forms used to document home care include:

• Referral source information/intake form

• Discipline-specific care plans

• Miscellaneous (conference notes, verbal order forms, telephone calls)

Modified from Iyer PW, Camp NH 1999 Nursing documentation: a nursing process approach. St Louis, Mosby.

Some parts of the record are needed in the home with the client; other information is needed in an office setting. Thus duplication of documentation is necessary, or agency policies are needed regarding what forms nurses need to leave at their office versus what forms need to be taken into the homes. Computerised client records are a way of handling these different needs. With the use of modems and laptop computers, it is becoming possible for the records to be available in multiple locations, which allows greater access to the multidisciplinary needs that are often present in home healthcare.

Long-term healthcare documentation

An increasing number of elderly people require care in long-term healthcare facilities. Since many individuals will live in this setting for the rest of their lives, they are referred to as residents rather than clients. The information provided within nursing documentation has a direct influence on the level of care a resident will receive.

Long-term client care in Australia has particular aspects that make documentation practices somewhat unique (Pelletier and others, 2002). In extended care, government agencies are instrumental in determining the standards and policies for documentation. In addition, the health department in each state or territory governs the frequency of written nursing records of the residents in long-term care facilities. Since residents are often stable, daily documentation may be completed using flow-sheets. Assessments done several times a day in the acute care setting may be required only weekly or monthly in the extended-care setting.

Extended-care agencies are also developing skilled-care units for residents requiring increased levels of care, in response to the demands for shorter hospital stays. Extended-care documentation supports a multidisciplinary approach in the assessment and planning process. Communication among healthcare providers such as nurses, social workers, occupational therapists and dietitians is essential in the regulated documentation process.