Scientific knowledge base

Medications administered to clients are used, almost exclusively, to prevent, diagnose or treat disease. Nurses need to be familiar with the actions and effects of medications they administer to clients. Moreover, to administer medications safely and accurately to clients, nurses draw on an understanding of physiology, pharmacology including pharmacokinetics (the movement of drugs in the human body), pharmacodynamics (the biochemical and physiological effect of drugs), human growth and development, human anatomy and physiology, nutrition and mathematics.

Application of pharmacology in nursing practice

Names

A medication may have as many as three different names—the chemical name, a generic (non-proprietary) name and a trade name. A medication’s chemical name provides an exact description of the medication’s composition and molecular structure; chemical names are rarely used in clinical practice. An example of a chemical name is 7-chloro-1,3-dihydro-1-methyl-5-phenyl-3H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one. The generic name, for example, diazepam, is given by the manufacturer that first develops the medication. The generic name (written with a lowercase initial letter) is the name listed in official publications such as the British Pharmacopoeia and the MIMS Annual. The trade name, brand name or proprietary name (written with an uppercase initial letter) is the name under which a manufacturer markets a medication. The trade name has the symbol® at the upper right of the name on the packaging, indicating that the manufacturer has registered the medication’s name (e.g. Valium®). A drug may have several trade names. The following illustrates the three-name system:

Manufacturers choose trade names that are easy to pronounce, spell and remember so that the general public will recognise them and ask for specific brands. Many different companies may produce the same medication. Hospitals and clinic pharmacies dispense medications using the generic name to avoid confusion. The nurse finds medications under a variety of different names, however, and must be careful to obtain the exact name and spelling for a particular medication and check all trade names against the generic name to be sure the correct drug is given.

Nurses also need to be aware that some trade brands of the same generic medication may be able to be substituted safely (referred to as ‘brand name substitution’); for example, Febridol (trade name) can usually be substituted for Panadol (trade name) when a client is ordered paracetamol (generic name). However, in some situations not all trade brands of the same generic drug are equal, and so the prescriber/pharmacist should be consulted before a nurse substitutes trade brands. For example, when a client is prescribed the medication warfarin (generic name) it is important that Coumadin (trade name) is not substituted for Marevan (trade name), as they may not be bioequivalent (i.e. warfarin 5 mg of Coumadin may not be the same as warfarin 5 mg of Marevan).

Classification

Nurses must recognise the category or class to which medications with similar characteristics are allocated. Medication classification indicates the effect of the medication on a body system, the symptoms the medication relieves or the medication’s desired effect. For example, clients who have type 2 diabetes often take oral hypoglycaemic agents to help control their blood glucose levels. Usually, each class contains more than one medication that can be prescribed for the type of health problem. For example, there are more than five different types of oral hypoglycaemic agents. The physical and chemical composition of medications within a class may be slightly different. For example, two of the oral hypoglycaemic agents, a sulfonylurea and a biguanide, have different functions and are often prescribed together. A sulfonylurea stimulates the release of insulin from the pancreas, whereas a biguanide decreases the rate of hepatic glucose production. A prescriber chooses a particular oral hypoglycaemic medication based on how it works with the client’s symptoms or the client characteristics, cost, efficacy and dosing frequency. The prescriber may also choose based upon their own experience with the medication in other clients.

A medication may also be part of more than one class. For example, aspirin is an analgesic, an antipyretic, an anti-inflammatory and an anti-platelet medication. Often, the dose administered determines the class or action of the medication. An example of this is where a client may be prescribed antidepressants for neuropathic pain or the use of antihypertensive medicines for the treatment of heart failure.

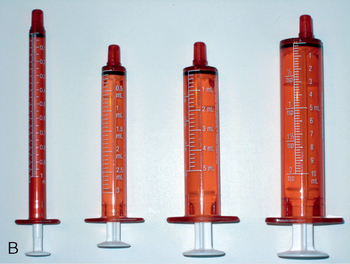

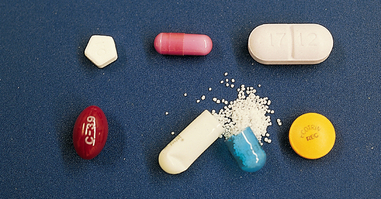

Medications are available in a variety of forms or preparations (see Figure 31-1 and Box 31-1). The form of the medication determines its route of administration and speed of absorption. The composition of a medication is designed to enhance its absorption and metabolism. When administering a medication, the nurse must be certain to use the proper form that is appropriate to the client’s condition (e.g. syrup if swallowing tablets is difficult).

FIGURE 31-1 Forms of oral medications. Top row: Uniquely shaped tablet, capsule, scored tablet. Bottom row: Gelatin-coated liquid, extended-release capsule, enteric-coated capsule.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2004 Fundamentals of nursing, ed 6. St Louis, Mosby.

Caplet: solid dosage form for oral use; shaped like capsule and coated for ease of swallowing.

Capsule: solid dosage form for oral use; medication in powder, liquid or oil form and encased in gelatin shell; capsule coloured to aid in product identification.

Elixir: clear fluid containing water and/or alcohol; designed for oral use; usually has sweetener added.

Enteric-coated tablet: tablet for oral use coated with materials that do not dissolve in the stomach; coatings dissolve in the intestine, where medication is absorbed.

Extract: concentrated medication form made by removing active portion of medication from its other components (e.g. fluid extract is medication made into solution from vegetable source).

Glycerite: solution of medication combined with glycerin for external use; contains at least 50% glycerin.

Intraocular disk: a small flexible oval consisting of two soft outer layers and a middle layer containing medication; when moistened by ocular fluid, releases medication for up to 1 week.

Liniment: preparation usually containing alcohol, oil or soapy emollient that is applied to skin.

Lotion: medication in liquid suspension applied externally to protect skin.

Ointment (salve): semisolid, externally applied preparation, usually containing one or more medications.

Paste: semisolid preparation, thicker and stiffer than ointment; absorbed through skin more slowly than ointment.

Pessary: solid dosage form mixed with gelatin and shaped into form of pellet for insertion into the vagina; melts when it reaches body temperature, releasing medication for absorption.

Pill: solid dosage form containing one or more medications, in globule, ovoid or oblong shape; true pills are rarely used because they have been replaced by tablets.

Solution: liquid preparation that may be used orally, parenterally or externally; can also be instilled into body organ or cavity (e.g. bladder irrigations); contains water with one or more dissolved compounds; must be sterile for parenteral use.

Suppository: solid dosage form mixed with gelatin and shaped into form of pellet for insertion into the rectum; melts when it reaches body temperature, releasing medication for absorption.

Suspension: finely divided drug particles dispersed in liquid medium; when suspension is left standing, particles settle to bottom of container; commonly an oral medication and not given intravenously.

Syrup: medication dissolved in concentrated sugar solution; may contain flavouring to make medication more palatable.

Tablet: powdered dosage form compressed into hard disks or cylinders; in addition to primary medication, contains binders (adhesive to allow powder to stick together), disintegrators (to promote tablet dissolution), lubricants (for ease of manufacturing) and fillers (for convenient tablet size).

Tincture: alcohol or water–alcohol medication solution.

Transdermal disk or patch: medication contained within semipermeable membrane disk or patch, which allows medications to be absorbed through the skin slowly over long period.

Troche (lozenge): flat, round dosage form containing medication, flavouring, sugar and mucilage; dissolves in the mouth to release medication.

Medication legislation and standards

The role of Australian governments in regulation of the pharmaceutical industry is to protect the health of the public by ensuring that medications are safe and effective. Control is exercised at three levels. The Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (amendments made 2003; see www.tga.gov.au) regulates all drugs developed in or imported into Australia. It controls medication manufacture, sales and distribution, medication testing, naming and labelling, and the regulation of controlled substances. Advertising of some poisons to the public is also regulated by this Act.

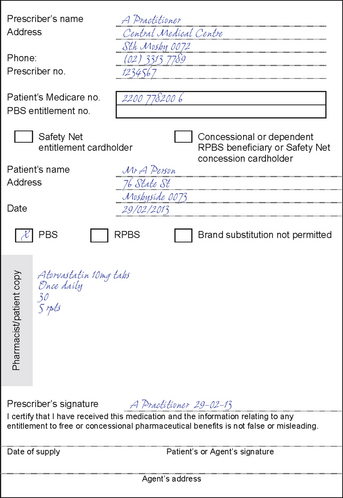

The National Health Act 1953 applies to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme that provides subsidised drugs to Australian residents. It also limits the amount of drugs supplied, and the number of times and frequency the supply can be repeated. Not all drugs are available at subsidised rates. Administration of medications by nurses is subject to further control by various regulations; some of the most important are listed in Box 31-2.

BOX 31-2 DRUG USE CONTROL IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND

AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY

Drugs of Dependence Regulation 2009

Poisons (including drugs) are listed in schedules (Box 31-3) that detail their availability to the public. For example, drugs listed in Schedule 4 are restricted to medical, dental or veterinary prescription (also includes NP prescription in some states). Official publications, such as the British Pharmacopoeia, set standards for medication strength, quality, purity, packaging, safety, labelling and dose form.

BOX 31-3 STANDARD FOR THE UNIFORM SCHEDULING OF DRUGS AND POISONS IN AUSTRALIA

SCHEDULE 2

Pharmacy Medicine—substances, the safe use of which may require advice from a pharmacist and which should be available from a pharmacy or, where a pharmacy service is not available, from a licensed person.

SCHEDULE 3

Pharmacist Only Medicine—substances, the safe use of which requires professional advice but which should be available to the public from a pharmacist without a prescription.

SCHEDULE 4

Prescription Only Medicine—substances, the use or supply of which should be by or on the order of persons permitted by state or territory legislation to prescribe and should be available from a pharmacist on prescription.

SCHEDULE 5

Caution—substances with a low potential for causing harm, the extent of which can be reduced through the use of appropriate packaging with simple warnings and safety directions on the label.

SCHEDULE 6

Poison—substances with a moderate potential for causing harm, the extent of which can be reduced through the use of distinctive packaging with strong warnings and safety directions on the label.

SCHEDULE 7

Dangerous Poison—substances with a high potential for causing harm at low exposure and which require special precautions during manufacture, handling or use. These poisons should be available only to specialised or authorised users who have the skills necessary to handle them safely. Special regulations restricting their availability, possession, storage or use may apply.

SCHEDULE 8

Controlled Drug—substances which should be available for use but require restriction of manufacture, supply, distribution, possession and use to reduce abuse, misuse and physical or psychological dependence.

SCHEDULE 9

Prohibited Substance—substances which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of commonwealth and/or state or territory health authorities.

From Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration 2012 Poisons Standard 2012 (reviewed annually). Canberra, Australian Government. Online. Available at www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2012L01200 6 Jul 2012.

HEALTHCARE INSTITUTIONS AND MEDICATION LAWS

Healthcare institutions establish individual policies that must meet national, state and local government laws and regulations. The size of an institution, the type of service it provides and the type of professional personnel employed all influence policy development. Institutional policies are often more restrictive than government controls. An institution is concerned mainly with preventing health problems that may result from medication use. For example, a common institutional policy is the automatic discontinuation of antibiotic therapy after a set number of days. Although the prescriber may reorder the antibiotic, this policy helps to control unnecessarily prolonged medication therapy.

MEDICATION REGULATIONS AND NURSING PRACTICE

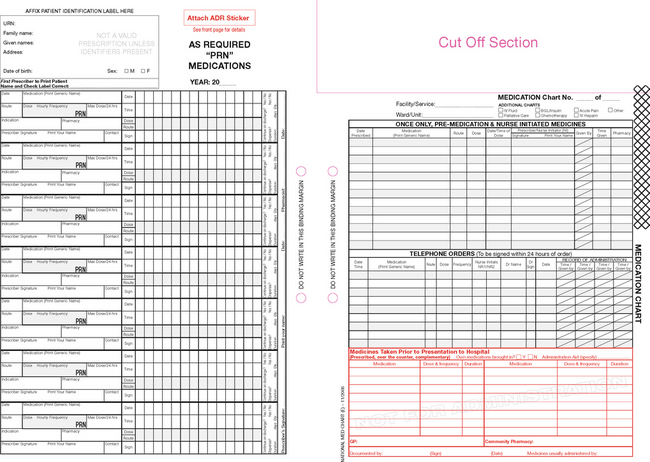

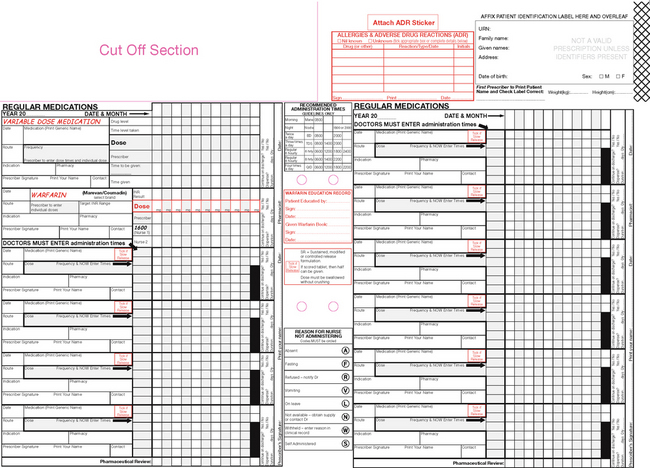

The nurse is responsible for following legal provisions when administering controlled substances or opioids (e.g. as listed under Schedule 8 of the Australian Poison Classification Schedule), which are carefully controlled through national and state guidelines (see Chapters 10 and 11. Violations of the relevant Acts are punishable by fines or imprisonment and may lead to loss of nursing registration. Hospitals and other healthcare institutions have policies for the proper storage and distribution of controlled drugs (Box 31-4).

BOX 31-4 GUIDELINES FOR SAFE ADMINISTRATION OF CONTROLLED DRUGS

• Store all controlled drugs in a locked, secured cabinet (computerised locked cabinets are available).

• A registered nurse carries a set of keys (or a special computer entry code) for the controlled drug cabinet.

• During an institution’s change of shift, the nurse going off duty counts all controlled drugs with the nurse coming on duty. Both nurses sign the controlled drug record to indicate that the count is correct.

• Discrepancies in drug counts are reported immediately.

• A special inventory record is used each time a controlled drug is dispensed.

• The record is used to document the client’s name, date, time of drug administration, name of drug, dose and signature of nurse dispensing the drug.

• The form provides an accurate ongoing count of controlled drugs used and remaining.

• If only one part of a premeasured dose of a controlled drug is administered, a second nurse witnesses disposal of the unused portion and documents such on the record form.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Many healthcare professionals believe that the law dictates that two nurses need to double-check controlled substances from the medication safe to the bedside, but this is not the case. There are a number of hospitals and clinical agencies that have a single-check policy, requiring the nurse to be both competent and accountable for their checking of these medicines.

What can a nurse do when single-checking medicines to ensure that medicines are administered safely?

Pharmacokinetics as the basis of medication actions

To be therapeutically useful, medications must be taken into the body, be absorbed and distributed to cells, tissues or a specific organ and alter the body’s physiological functions. Pharmacokinetics is the study of how medications enter the body, reach their site of action in sufficient concentration and are metabolised and excreted from the body. Pharmacodynamics is the study of how a drug acts in the body to exert its action and side effects. The nurse uses knowledge of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics when timing medication administration, selecting the route of administration, judging the client’s risk of alterations in medication action and observing the client’s response.

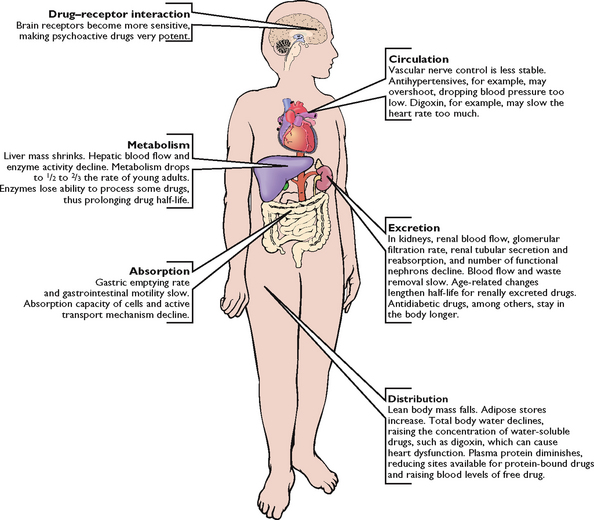

Absorption

Absorption refers to passage of medication molecules into the blood from the site of administration. Factors influencing medication absorption are the route of administration, ability of the medication to dissolve, blood flow to the site of administration, body surface area, pH and lipid solubility of the medication.

ROUTE OF ADMINISTRATION

Medications can be administered by various routes. Each route has a different rate of absorption, as discussed in more depth later in the chapter.

ABILITY OF THE MEDICATION TO DISSOLVE

The ability of an oral medication to dissolve depends largely on its form or preparation. Solutions and suspensions, being already in a liquid state, are often absorbed more readily than tablets or capsules. The pH of a medication often determines whether absorption occurs via the gastric mucosa or the small intestine. Absorption can be delayed by the use of enteric-coated tablets, which are not dissolved in the acidic environment of the stomach, ensuring that the drug is absorbed in the alkaline environment of the small intestine. The degree of gastric motility determines the length of time the medication is in contact with the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa and so will alter both the speed and the amount of medication absorbed.

BLOOD FLOW TO THE AREA OF ABSORPTION

When tissue contains many blood vessels, medications are absorbed more rapidly. This occurs because blood is constantly moving in these vessels. This facilitates movement of the drug around the body.

BODY SURFACE AREA

When a medication is in contact with a large surface area, it will be absorbed at a faster rate as there are more sites where the drug can absorb. This explains why the majority of medications are absorbed in the small intestine rather than in the stomach, as the surface area of the small intestine is much greater than that of the stomach.

LIPID SOLUBILITY OF A MEDICATION

Highly lipid-soluble medications are absorbed more easily as they more readily cross the cell membrane. This is because the cell membrane is made of a lipid layer and will thus allow lipid-soluble medications to pass more readily than non-lipid-soluble medications.

PRESENCE OF FOOD

Food will delay the passage of the medication through the GI system, and so absorption may be impaired. Some oral medications are therefore absorbed more easily when administered between or before meals. In some cases, medications administered together may interfere with each other and impair the absorption of one or both.

Nurses use knowledge of factors that may alter or impair absorption of prescribed medications to ensure all medications are administered correctly for their clients. This information is based on an understanding of drug pharmacokinetics, the nursing history, physical examination and daily interactions with clients. The nurse consults and collaborates with the healthcare team to ensure the best therapeutic effect is achievable. Before administering any unfamiliar medication, pharmacology texts, E-MIMS, package inserts and the pharmacist or prescriber should be consulted. This identifies medication actions, interactions, medication–nutrient interactions or indications, contraindications, or indications that a drug should not be given because of the client’s current medical condition (e.g. oral medication if the client is nauseated or vomiting). The nurse may also use this knowledge in explaining to clients that enteric-coated medicines (protective coating) may not be crushed/halved as this would render the medicine unprotected in the GI tract.

Distribution

After a medication is absorbed, it is distributed in the body to tissues and organs and ultimately to its specific site of action. The rate and extent of distribution depend on the physical and chemical properties of medications and the physiology of the person taking the medication.

BLOOD CIRCULATION

Once a medication enters the bloodstream it is carried throughout the tissue and organs of the body. The speed of drug distribution depends on the vascularity of the various tissues and organs. Distribution will be enhanced in tissues with extensive blood supply (e.g. heart, liver and kidneys), and slower in less-well-perfused tissue (e.g. skin and fat). When conditions limit blood flow (e.g. hypovolaemic shock, peripheral vascular disease or solid tumours which have a poor blood supply), then distribution is inhibited.

MEMBRANE PERMEABILITY

To be distributed to an organ, a medication must pass through all of the biological membranes of that organ or tissue. Some membranes serve as protective barriers to the passage of medications. For example, the blood–brain barrier allows only fat-soluble medications to pass into the brain and cerebral spinal fluid. A disruption in the biological membrane barrier by disease or trauma allows drugs to cross the protective barrier. This situation may be used to advantage when treating infection of the central nervous system, but may also give rise to serious adverse effects. Older clients, for example, may experience adverse effects such as confusion as a result of the change in the permeability of the blood–brain barrier, and consequently easier passage of fat-soluble and water-soluble medications.

The placental membrane is an example of a non-selective barrier to medications. Fat-soluble and non-fat-soluble agents may cross the placenta and produce fetal deformities, respiratory depression and, in cases of maternal opioid abuse, withdrawal symptoms in the newborn. For example, if a mother is administered an opioid late in labour, then this may cross the placental membrane resulting in a sedated newborn with respiratory depression.

PROTEIN BINDING

The degree to which medications bind to serum proteins (in the blood), such as albumin or globulin, affects medication distribution. Most medications bind to these proteins to some extent. When medications bind to these proteins, they cannot exert any pharmacological activity. Protein binding can therefore be regarded as a drug storage mechanism. The unbound or ‘free’ medication is the active form of the medication. Older adults have decreased levels of albumin in the bloodstream, probably caused by change in liver function; the same is true for clients with liver disease or malnutrition. Because of the potential for more unbound medication, the older adult may be at risk of an increase in medication activity or toxicity, or both. There are commonly one or two protein-binding sites for a particular medication. When two drugs with the same common binding sites are given together, they will compete and the concentration of free drugs will alter.

Metabolism

Many drugs are metabolised into a less active or inactive form that is more easily excreted, either at the site of action or before the medication reaches its destination (hence the need for increased doses in some cases). This biotransformation occurs under the influence of enzymes that detoxify, degrade (break down) and remove biologically active chemicals. Most biotransformation occurs within the liver, although the lungs, kidneys, blood and intestines also metabolise medications. The liver is especially important, because its specialised structure oxidises and transforms many toxic substances and degrades many harmful chemicals before they become distributed to the tissues. If a decrease in liver function occurs, a medication may be eliminated more slowly, resulting in an accumulation of the medication and increasing a client’s risk of medication toxicity. For example, a small sedative dose of a barbiturate may cause a client with liver disease to lapse into a coma.

Excretion

After medications are metabolised, they exit the body through the kidneys, liver, bowel, lungs and exocrine glands.

The kidneys are the main organs for medication excretion. Some medications escape extensive metabolism and exit unchanged in the urine. Other medications must undergo biotransformation in the liver before being excreted by the kidneys. If renal function declines, then a client is at risk of medication toxicity. If the kidneys cannot adequately excrete a medication, it may be necessary to reduce the dose. Maintenance of an adequate fluid intake (50 mL/kg/day) promotes proper elimination of medications for the average adult.

The GI tract is another route for medication excretion. Many medications enter the hepatic circulation to be broken down by the liver and excreted into the bile. After chemicals enter the intestines through the biliary tract, the intestines may reabsorb them. Factors increasing peristalsis (e.g. laxatives and enemas) accelerate medication excretion through the faeces, whereas factors that slow peristalsis (e.g. inactivity and improper diet) may prolong a medication’s effects.

Gaseous and volatile compounds, such as anaesthetic gases and alcohol, exit through the lungs. Deep-breathing and coughing helps the postoperative client eliminate anaesthetic gases more rapidly. The exocrine glands excrete lipid-soluble medications. Good hygiene to promote cleanliness and skin integrity can prevent skin irritation when medications exit through sweat glands.

Nurses and mothers should check the safety of medications used while breastfeeding, as medications excreted through the mammary glands increase risk that a nursing infant will ingest the chemicals.

Types of medication action

Medications vary considerably in the way they act and the types of action. Factors other than characteristics of the medication also influence medication actions. These include therapeutic effects, adverse effects, idiosyncratic reactions, toxic reactions and allergic reactions.

Therapeutic effects

The therapeutic effect is the expected or predictable physiological response a medication causes. Each medication has a desired therapeutic effect for which it is prescribed. For example, glyceryl trinitrate (Anginine) is used to reduce the cardiac workload and increase myocardial oxygen supply. A single medication may have many therapeutic effects. For example, morphine is an opioid analgesic, a vasodilator and releases antidiuretic hormone. The nurse must know the therapeutic effect of each prescribed medication so they can monitor the response of the medication and teach the client about the medication’s intended effect.

Adverse effects

Adverse effects are generally unexpected effects of the medication. These may be related to the pharmacological effect, the way an individual takes the medication or the individual’s response to the medication. When adverse responses to medications occur, the prescriber may modify the therapy or discontinue the medication. These effects may be called ‘side effects’ by consumers and non-healthcare professionals; however, it is important to note that these are unwanted effects rather than ‘allergic effects’. For example, a client may say they are ‘allergic’ to codeine as it makes them constipated. This is an adverse effect (i.e. unwanted effect), but it is not an allergic reaction.

IDIOSYNCRATIC REACTIONS

Idiosyncratic reactions are adverse effects to which the client under- or over-reacts, or has a reaction which is different from that expected. For example, a child receiving an antihistamine (e.g. Benadryl) may become extremely agitated or excited instead of drowsy. Other effects may range from a mild skin rash to a life-threatening reaction. Although it is impossible to assess clients for idiosyncratic responses when they first take a medication, the nurse must always assess the client’s response to a drug if it has been previously prescribed. For example, if a client is ordered penicillin (an antibiotic), the nurse must ask if the client has taken the drug before and, if so, what was the outcome (i.e. did they have any reaction?), because many people have allergic reactions to this group of medicines. Healthcare providers are encouraged to report adverse effects to the authorities so that information can be used in predicting and preventing adverse drug effects. The risk of adverse drug effects increases with multiple drug regimens (polypharmacy).

• CRITICAL THINKING

Polypharmacy is defined as the concurrent use of 5 or more medicines by a client at one time. These may be prescription, over-the-counter or complementary medicines. The risk of dangerous adverse effects and interactions increases when more than one medicine is used, as the drugs may interact with each other and produce toxic effects. The problem is that polypharmacy is often necessary for clients with chronic health conditions and sometimes it is important to use medicines to treat symptoms caused by other drugs the client is taking. For example, a client who requires a diuretic (e.g. furosemide) for heart failure may then require a potassium supplement in response to the excess loss of potassium through diuresis. Polypharmacy can make it difficult to take a medication history from a client (who may have trouble remembering all the different medicines they have used), and it can be costly for the client. Nurses should be aware of the risks of polypharmacy and should actively work to try to implement quality use of medicines (i.e. assessing the use of medicines and their appropriateness) for their clients.

What would you do if a client you are admitting spoke of taking many medicines for various health complaints? Is it enough to document these alone, or what else could you do?

TOXIC REACTIONS

Predictable adverse effects of a medication are known as toxic reactions, which are related to the pharmacological properties of the medication. Toxic effects may develop after prolonged intake of a medication or when a medication accumulates in the blood because of impaired metabolism or excretion. Lethal effects depend on the medication’s action. For example, toxic levels of digoxin (an anti-arrhythmic medicine used to slow down heart rate) may cause severe bradycardia and death. Antidotes are available to treat specific types of medication toxicity; for example, naloxone (Narcan) is used to reverse the effects of opioid toxicity.

ALLERGIC REACTIONS

Allergic reactions are an unpredictable response to a medication, and may represent as many as 24% of reported adverse drug reactions (Lazarou and others, 1998). A client can become immunologically sensitised to the initial dose of a medication. With repeated administration, the client develops an allergic response to the medication, its chemical preservatives or a metabolite. The medication or chemical acts as an antigen, triggering the release of the body’s antibodies. Allergic symptoms vary from mild (Box 31-5) to severe, depending on the individual and the medication. Antibiotics cause a high incidence of allergic reactions.

BOX 31-5 MILD ALLERGIC REACTIONS

Urticaria: raised, irregularly shaped skin eruptions with varying sizes and shapes; eruptions have reddened margins and pale centres.

Rash: small, raised vesicles that are usually reddened; often distributed over entire body.

Pruritus: itching of skin; accompanies most rashes.

Rhinitis: inflammation of mucous membranes lining nose; causes swelling and clear, watery discharge.

Severe or anaphylactic reactions are characterised by sudden constriction of bronchiolar muscles, oedema of the pharynx and larynx, severe wheezing and shortness of breath. The client may also become severely hypotensive, necessitating emergency resuscitation measures. Adrenaline, antihistamines and bronchodilators may be used to treat anaphylactic reactions. A client with a known history of a medication allergy should avoid re-exposure and wear an identification bracelet or medal (Figure 31-2) which alerts nurses, medical staff and emergency personnel to the allergy.

Medication interactions

When one medication modifies the action of another medication, a medication interaction occurs. These interactions are common in people taking several medications. A medication may increase or diminish the action of other medications, and may alter the way another medication is absorbed, metabolised or eliminated from the body. When two medications have a synergistic effect, i.e. work together, the effect of the two medications combined is greater than the effect of the medications when given separately. For example, alcohol is a central nervous system depressant that has a synergistic effect on antihistamines, antidepressants, barbiturates and opioid analgesics, making the client more sedated and lowering blood pressure/consciousness further.

A medication interaction is not always undesirable. Often the prescriber orders a combination of medications to create an interaction that will have a beneficial effect on the client’s condition. For example, where hypertension cannot be controlled with one medication, the client typically receives several medications that act together to control the blood pressure (e.g. diuretics and vasodilators). Multimodal analgesia is another good example of this (see Chapter 41).

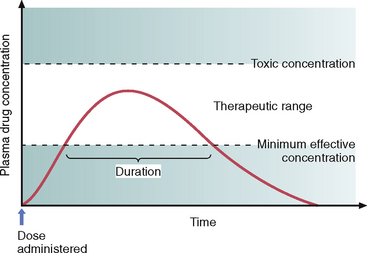

Medication dose responses

After a medication is administered, it undergoes absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion. The quantity and distribution of a medication in different body compartments change constantly. When a medication is prescribed, the goal is to maintain a constant and safe therapeutic serum level and take into account peaks, troughs, duration of action and plateaus (Box 31-6). Repeated doses are required to achieve this constant therapeutic plasma concentration of a medication because a part of a medication is always being excreted. The highest serum concentration (peak concentration) of the medication occurs when the rate of administration equals the rate of excretion. After peaking, the serum medication concentration falls progressively. With intravenous administration, the peak concentration occurs quickly but the serum level also begins to fall immediately (Figure 31-3).

BOX 31-6 TERMS ASSOCIATED WITH MEDICATION ACTIONS

Duration of action: time during which the medication is present in concentration great enough to produce a response.

Half-life: time taken for the plasma concentration of a drug to fall to half of its original value.

Onset: time it takes after a medication is administered for it to produce a response.

Peak: time it takes for a medication to reach its highest effective concentration.

Plateau: blood serum concentration of a medication reached and maintained after repeated fixed doses.

Trough: minimum blood serum concentration of medication reached just before the next scheduled dose.

FIGURE 31-3 The therapeutic range of a medication occurs between the minimum effective concentration and the toxic concentration.

From Lehne RA 2010 Pharmacology for nursing care, ed 7. St. Louis, Saunders.

All medications have a serum half-life, which is the time it takes for excretion processes to lower the serum medication concentration by half. This half-life is different for each medication. To maintain a therapeutic plateau, the client must receive regular fixed doses, the timing of which is based on the serum half-life. For example, analgesia is most effective when given on a regular around-the-clock basis, rather than a prn (as needed) basis in response to a client’s report of pain. In this way, an almost constant level of analgesia is maintained. After an initial loading dose, the client receives each successive dose when the previous dose reaches its half-life.

The client and nurse must follow regular dosage schedules and adhere to prescribed doses and dosage intervals. The prescriber, or the agency in which the nurse is employed, sets dosage schedules. When teaching clients about dosage schedules, the nurse should use language that is familiar to the client, for example ‘Take a dose in the morning and again in the evening’. Knowledge of the time of medication action also helps the nurse and client to anticipate a medication’s effect and the time of a therapeutic response. For example, when administering oral furosemide (Lasix), the nurse is aware a diuresis should occur in 1–2 hours; whereas when administering IV furosemide, a diuresis is expected in 20 minutes.

Routes of administration

The route prescribed for administering a medication depends on the medication’s properties and desired effect and on the client’s physical and mental condition (Table 31-1). A nurse collaborates with the medical practitioner in determining the best route for a client’s medication, as in the following clinical example.

TABLE 31-1 FACTORS INFLUENCING CHOICE OF ADMINISTRATION ROUTES

| ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES OR CONTRAINDICATIONS |

|---|---|

| ORAL, BUCCAL, SUBLINGUAL ROUTES | |

|

These routes are avoided when client has alterations in gastrointestinal function (e.g. nausea, vomiting), reduced motility (after general anaesthesia or bowel inflammation) and surgical resection of part of gastrointestinal tract Some medications are destroyed by gastric secretions. Oral administration is contraindicated in clients unable to swallow (e.g. clients with neuromuscular disorders, oesophageal strictures, mouth lesions) Oral medications cannot be given when client has gastric suction and are contraindicated in clients before some tests or surgery Unconscious or confused client is unable or unwilling to swallow or hold medication under tongue Oral medications may irritate lining of gastrointestinal tract, discolour teeth or have unpleasant taste |

|

| SUBCUTANEOUS (SUBCUT), INTRAMUSCULAR (IM), INTRAVENOUS (IV), INTRADERMAL (ID) ROUTES | |

|

Routes provide means of administration when oral medications are contraindicated More-rapid absorption occurs than with topical or oral routes IV infusion provides medication delivery when client is critically ill or long-term therapy is required. If peripheral perfusion is poor, IV route is preferred over injections |

There is risk of introducing infection, and some medications are expensive. Clients must experience repeated needle-sticks. The subcut, IM and ID routes are avoided in clients with bleeding tendencies There is risk of tissue damage with subcut injections IM and IV routes are dangerous because of rapid absorption These routes cause considerable anxiety in many clients, especially children |

| SKIN | |

| Topical | |

| Clients with skin abrasions are at risk of rapid medication absorption and systemic effects | |

| Transdermal | |

| Transdermal applications provide prolonged systemic effects, with limited side effects | Application leaves oily or pasty substance on skin and may soil clothing |

| MUCOUS MEMBRANES* | |

|

Mucous membranes are highly sensitive to some medication concentrations Insertion of rectal and vaginal medication often causes embarrassment Client with ruptured eardrum cannot receive irrigations Rectal suppositories are contraindicated if client has had rectal surgery or if active rectal bleeding is present |

|

| INHALATION | |

| Some local agents can cause serious systemic effects | |

*Includes eyes, ears, nose, vagina, rectum, buccal and sublingual routes.

Mr Jensen has progressively deteriorated over your shift. His oral temperature is 39.5°C. He complains of nausea and is unable to tolerate oral fluids. You check Mr Jensen’s medical administration record, which reads ‘Paracetamol 1 g orally PRN for temperature above 38.5°C’. On the basis of your assessment that Mr Jensen is nauseous, you consider that he will not be able to tolerate an oral dose of paracetamol. You decide to contact the medical officer to request an order for intravenous paracetamol instead. This enables the nurse to administer the drug to decrease fever without increasing the client’s symptoms of nausea.

Oral routes

ORAL ADMINISTRATION

The oral route is the easiest and the most commonly used. Medications are given by mouth and swallowed with fluid. Oral medications usually have a slower onset of action and a more prolonged effect than parenteral (injected) medications, and their effect may be more unpredictable than other routes as many factors can affect GI absorption. Oral medicines enter the hepatic circulation once absorbed from the GI tract, and then travel to the liver where they need to ‘clear’ the liver before travelling on throughout the body. Some drugs are nearly totally destroyed by the liver (i.e. there is nothing left to travel throughout the body to act on their target cells) and so these medicines cannot be given orally (e.g. glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) or insulin). This situation is called the ‘first-pass effect’. Clients generally prefer the oral route, which is suitable for tablet or liquid forms of medications.

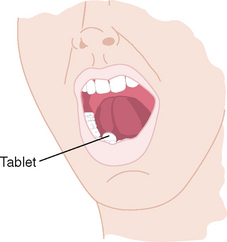

SUBLINGUAL ADMINISTRATION

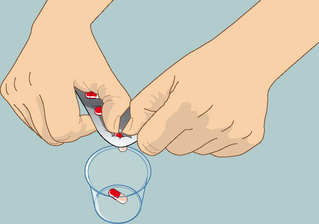

Some medications are designed to be readily absorbed after being placed under the tongue to dissolve (Figure 31-4). A medication given by the sublingual (subling) route should not be swallowed, as the desired effect will not be achieved (i.e. it will not be absorbed into the bloodstream under the tongue where it can work immediately, but will travel to the stomach where it will be destroyed by the acidic environment or by the extensive liver metabolism). Glyceryl trinitrate is commonly given this way, by tablet or spray. The client should not take a drink until the medication is completely dissolved.

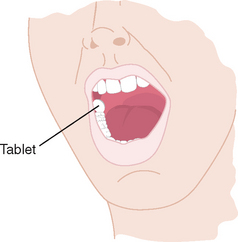

BUCCAL ADMINISTRATION

Administration of a medication by the buccal route involves placing the solid medication in the mouth against the mucous membranes of the cheek, where it stays until it dissolves (Figure 31-5). Clients should be taught to alternate cheeks with each dose to avoid mucosal irritation. Clients are also warned not to chew or swallow the medication or to take it with any liquids, for the same reason as the sublingual route above. A buccal medication acts locally on the mucosa or systemically as it is swallowed in a person’s saliva.

Parenteral routes

PARENTERAL ADMINISTRATION

Parenteral administration involves injecting a medication into body tissues. The major sites of injection are:

• subcutaneous (subcut): injection into tissues just below the dermis of the skin

• intramuscular (IM): injection into a muscle

• intravenous (IV): injection into a vein

• intradermal (ID): injection into the dermis immediately below the epidermis

• scalp vein: used in infants as scalp veins are more prominent and less difficult to locate than peripheral veins.

Some medications are administered into body cavities other than the types listed above. Institutions vary regarding whether nurses are responsible for the administration of medications through these advanced techniques. The nurse often remains responsible for monitoring the integrity of advanced systems of medication delivery, for understanding the therapeutic value of the medication and for evaluating the client’s response to it, even when they do not administer the medication.

EPIDURAL

A common body cavity route is into the epidural space via a catheter placed by an anaesthetist. The epidural route is most commonly used for the administration of analgesia peri- and postoperatively (see Chapter 41). Nurses working in specialised areas (e.g. acute pain nurses, recovery room nurses) may administer drugs in bolus form (a small dose) or by continuous infusion.

INTRATHECAL

Intrathecal drugs are administered by an anaesthetist through a catheter placed into the subarachnoid space or into one of the ventricles of the brain. Intrathecal administration is often associated with long-term drug administration through surgically implanted catheters.

INTRAPERITONEAL

In the intraperitoneal technique, drugs (chemotherapeutics and antibiotics) are administered into the peritoneal cavity where they are absorbed into the circulation. One method of dialysis also uses the peritoneal route for the removal of fluid, electrolytes and waste products.

INTRAPLEURAL

In the intrapleural method, drugs are administered by a medical practitioner either directly through the chest wall or through a chest tube. Chemotherapeutics are the most common medications administered via this method. Medical staff also instil drugs that help resolve persistent pleural effusion to promote adhesion between the visceral and parietal pleura (pleurodesis).

INTRA-ARTERIAL

Intra-arterial infusions are administered directly into the arteries, and are used in clients with arterial clots. The nurse manages a continuous infusion of fibrinolytic (clot-dissolving) agents. The nurse must carefully monitor the integrity of this infusion to prevent inadvertent disconnection of the system and subsequent bleeding. It is important to note that nurses are not usually required to administer medicines intra-arterially and that inadvertent administration via this route will often result in severe tissue damage and amputation (in the cases of intra-arterial injections into limbs).

Topical administration

Medications applied to the skin and mucous membranes generally have local effects.

SKIN

Topical medications are applied to the skin by painting or spreading them over an area, applying moist dressings, soaking body parts in a solution or giving medicated baths. Systemic effects can occur if a client’s skin is thin, if the medication concentration is high or if contact with the skin is prolonged. Some medications (e.g. GTN and oestrogens) have systemic effects (i.e. work throughout the body, not just in the area where the medicine is applied) when applied topically by a transdermal disc or patch. The disc secures the medicated ointment to the skin. These topical applications may be applied for as little as 24 hours or as long as 7 days.

MUCOUS MEMBRANES

Medications can be applied to mucous membranes in a variety of ways:

• application of a liquid or ointment (e.g. eye drops, gargling, swabbing the throat)

• insertion of a medication into a body cavity (e.g. rectal suppository, vaginal pessary or medicated packing)

• instillation of fluid into a body cavity (e.g. ear drops, nose drops, or bladder and rectal instillation where fluid is retained)

• irrigation of a body cavity (e.g. flushing eye, ear, vagina, bladder or rectum with medicated fluid where fluid is not retained)

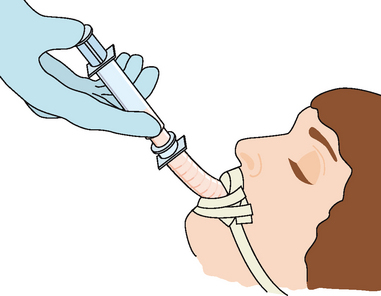

INHALATION

The deeper passages of the respiratory tract provide a large surface area for medication absorption. Medications can be administered through the nasal passages, oral passage or endotracheal tubes via the client’s mouth or nose into the trachea (Figure 31-6). Medications administered by the inhalation route are readily absorbed into the bloodstream and work rapidly (they have local as well as systemic effects) because of the rich vascular alveolar–capillary network present in the pulmonary tissue.