Chapter 17 Sociocultural considerations and nursing practice

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Understand what is meant by social constructivism and how it applies to the construction of health, knowledge and culture.

• Describe the context of nursing in Australia and New Zealand.

• Discover the processes underlying culture contact and their implications for healthcare.

• Define culture and ethnicity.

• Explore your own culture and ethnicity (including your identity/ies, attitudes, beliefs, behaviours) and how these affect nursing practice.

• Consider the role of power and power imbalances in healthcare and how these relate to social stratification, systemic racism and biases, and structural violence.

• Compare the theoretical principles underlying culturally safe nursing and transcultural nursing.

• Describe basic principles of providing culturally safe nursing care.

This chapter explores the potential influence of various social and historical processes on nursing care and health beliefs and behaviours. It focuses on understanding culture, ethnicity and class as well as related issues of power relations, processes and practices for enhancing appropriate care, and the pitfalls nurses may encounter in providing culturally safe care. Appropriate care is based on one-to-one relationships and is the basis of all nursing care. There are no checklists and no magic formula to ensure nurses cater for the holistic needs of clients. There is, however, a range of strategies that will enhance best practice within culturally diverse environments. Strategies include self-reflection and awareness; reflection on one’s own culture, attitudes, beliefs and profession; understanding the influence of power imbalances; enhancing communication skills; and drawing on the skills of interpreters. The keys to holistic care are developing trust; negotiating knowledge; negotiating outcomes; and understanding the influence of sociohistorical factors influencing health and nursing care.

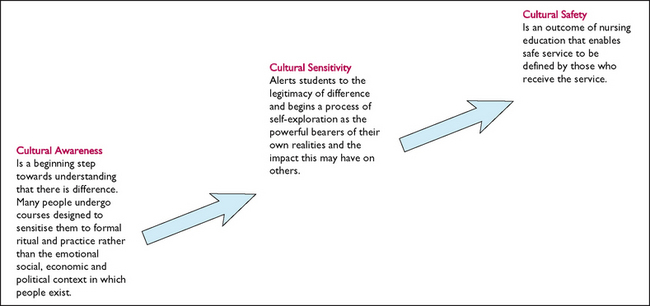

This chapter introduces you to a number of concepts and perspectives that you will need in your professional nursing practice to effectively address the interaction between culture and nursing care. The approach we advocate for is called cultural safety, which is defined as:

the effective nursing of a person/family from another culture, and is determined by that person or family. Culture includes but is not restricted to age or generation; gender; sexual orientation; occupation and socioeconomic status; ethnic origin or migrant experience; religious or spiritual belief; and disability. The nurse delivering the service will have undertaken a process of reflection on [their] own cultural identity and will recognise the impact that [their] personal culture has on [their] professional practice. Unsafe cultural practice is any action which diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and well-being of an individual.

(Nursing Council of New Zealand, 1996:9,1 cited in Taylor and Guerin, 2010:12)

We discuss the approach of cultural safety in more detail later in the chapter, contrasting it with ‘transcultural nursing’—another model of care that is sometimes used to address culture and nursing care but which comes from quite different philosophical assumptions.

Underpinning this chapter and our cultural safety approach is a philosophical commitment to social constructionism. This position refers to the socially constructed nature of reality, where humans come to know the world through experience and together construct reality by negotiating meanings through communication and power relationships. Such a position is in sharp contrast to that underlying a biomedically dominated healthcare system that sees reality as an unproblematic ‘given’ and disregards pertinent issues such as meaning and power in caring for clients. As an example of social constructionism, Rapport and Overing (2007) discuss ‘the body’, a taken-for-granted concept in Western cultures but a concept that is non-existent among some groups in Amazonia. This chapter also discusses other concepts that mainstream health cultures assume have a universal meaning, but which are in fact socially constructed: examples are the concepts of ‘health’ and ‘culture’ which experience shows are constructed in different ways by the diverse clients and workers in healthcare systems.

When clients and nurses are working from different assumptions about the nature of reality, what it means to be healthy, what causes and what might cure illnesses, what illnesses mean and about health priorities, it is easy to see that nursing care will not be at an optimum. This is why this chapter asks you to consider a number of perspectives on nursing care that may be different to those you currently hold. First we give you an overview of the context of nursing in Australia and New Zealand, and then have a closer look at a number of concepts and cultural experiences that you need to understand to provide culturally safe nursing care.

The context of nursing in Australia and New Zealand/Aotearoa

The Australian mainland was a ‘multicultural’ society long before Europeans set foot on the shores of Botany Bay, having already been occupied by Aboriginal groups for upwards of 40,000 years. Up to 500 different Indigenous2 language groups occupied the continent (Berndt and Berndt, 1988) and lived in well-defined socioeconomic, political, land-owning units (Elkin, 1964). In addition, the Torres Strait Islands, gathered under Queensland ownership in 1872 when it annexed all islands within a 60-mile radius of the mainland, constituted further diversity (Nakata, 2004). New Zealand/Aotearoa had a somewhat different beginning. The first settlers to arrive in New Zealand/Aotearoa were Polynesian people, between 250 and 1150 CE (Belich, 1996). By the 12th century there were numerous settlements, mainly along the coastline. These Polynesian settlers became known as Māri, and although dialectal differences developed, the people adhered to common cultural traditions (Rice, 1992). When Europeans decided to not only visit but stay, both Australia and New Zealand/Aotearoa became British colonial societies. However, significant differences marked this process in the two countries.

Australia was colonised in the late 18th century and the Crown claimed the land as terra nullius, meaning unoccupied, and therefore open to annexation without treaty (see Lippmann, 1999; McGraw, 1995; Reynolds, 1987, 1989). This was despite the fact that Macassan traders had been visiting the continent’s shores for trade for several hundred years and Europeans had first visited in the 1600s. As Nakata (2004:155) observes: ‘As inhabitants of a seaway, Islanders in the Torres Strait had long been used to welcoming or defending themselves against visitors and were themselves travellers of considerable distances, both north to Papua New Guinea and south to Cape York Peninsula’ (Haddon, 1935; MacGillivray, 1852; and Jukes 1847, all cited in Nakata, 2004). On the mainland the initial impact of a permanent European presence was far from peaceable. The land was taken by force and the period was characterised by massacres and punitive expeditions against Indigenous groups who fought to defend their land, its resources and their right to ceremonial practices and lore/law. For the original owners, all of these sociocultural aspects are inseparable from country.

The population was further decimated by infectious diseases that came with the colonisers; then came over 200 years of Indigenous dispossession and dislocation made possible by laws and policies applicable only to Indigenous Australians. These laws, and the policies and practices they enabled, were intrinsically racist and aimed at segregating, assimilating and controlling the original owners. This history is generally discussed with reference to the policy eras of dispersion, segregation, integration and assimilation (see the work of Broome, 2001; Cox, 2007; Eckermann and others, 2010; Kidd, 1997; Reynolds, 1987). Essentially, Indigenous Australians were treated by the state as ‘non-human’ and every aspect of their lives, including family organisation, employment, education, recreation and religion, was strictly controlled by some government instrumentality.

Indigenous people and non-Indigenous supporters were not passive in the face of these marginalising processes. The new policy eras of self-management and self-determination were ushered in following a national referendum in 1967, although true self-determination is still not realised some 44 years later. The referendum determined that the First Australians would finally be counted as citizens in the national census and that the Commonwealth government could legislate for the benefit of Indigenous people. These events saw the gradual dismantling of some of the repressive state-based legislation, and the first Aboriginal-community-controlled medical and legal services were established in the 1970s (Willis and Elmer, 2011:184). In 1990 the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) was established. Although subject to much critique and controversy, ATSIC is the closest Australia has come to having a true Indigenous representative body. As Sanders (2004) argues, it improved Indigenous people’s political participation, and enhanced regional representation and social reform. After 14 years it was abolished, having had its health responsibilities removed from it in 1995 (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 2004).

There has been major and extensive effort in relation to both land rights and native title under the new policy eras of self-management and self-determination. The Northern Territory Native Title Act (1976), the Mabo decision in 1992 and the Wik decision in 1996 are just some of the major developments in this area that space does not permit us to cover here (for further information, see Northern Land Council in Online resources). Smith and Morphy (2007) give an extensive overview of these developments in their edited volume on the social effects of native title, from which one could only conclude that their impact on improving the social position of Indigenous Australians is patchy at best. The Close the Gap campaign was launched in 2007 in an attempt to address the seemingly intractable nature of Indigenous disadvantage. This campaign is a collaboration between government, Indigenous and non-Indigenous health organisations, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (since 2008 known as the Australian Human Rights Commission, AHRC) and community leaders; its aim is to close the health and life-expectancy gap between Indigenous and other Australians within a generation. AHRS’s (2011) ‘shadow report’ says that it is still too early to assess progress.

Other notable events include the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC) following agitation by Black Deaths in Custody groups concerned about the over-representation of Indigenous people in jails and watch-houses and their preventable deaths while in custody (Johnston, 1991). Marchetti (2006:453) comments that it was hoped the RCIADIC would ‘transform race relations’ but concludes that its 339 recommendations have had limited impact on the social and economic position of Indigenous Australians and that it was deeply colonising in that it failed to ‘understand or incorporate Indigenous worldviews and values’ (Marchetti, 2006:454). Nonetheless, RCIADIC recommendation 247 says that all healthcare professionals need education on the impacts of forced child removal on Aboriginal people (Johnston, 1991), an effort that continues to the present time and is evident in the very production of this chapter.

It is noteworthy that this RCIADIC recommendation focused on what is perhaps the most enduring blight on Australian history: the genocidal policy and practice of forced child removal, where governments deemed Indigenous people incapable of raising their children and removed them to white families, orphanages and dormitories on missions and reserves. The RCIADIC findings on the impact of child removal informed a national inquiry into the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families (Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission, 1997). The report of that inquiry, commonly called ‘Bringing Them Home’, articulated in detail government practices that led to thousands of non-Indigenous Australians saying sorry to Indigenous Australians for the wounds of the past by signing ‘Sorry Books’, a campaign launched in 2008 (National Sorry Day Committee Inc., n.d.) Eventually these processes led to a national apology to Indigenous Australians from then Prime Minister Rudd in February 2008 (Celermejer and Moses, 2010:35).

The national apology was welcomed by Indigenous Australians and seemed to mark a new era in Australian history. However, as McAuley (2011:1) states: ‘Not only did the Apology make no provision for compensation for the wrongs suffered by those who were taken from their families, but the Rudd and Gillard governments have substantially maintained the controversial Northern Territory National Emergency Response (NTNER), or “intervention”, introduced in the dying days of the Howard government’. The Intervention followed the release of the Northern Territory government’s Board of Inquiry report into the protection of Aboriginal children from sexual abuse (Northern Territory Government, 2007). Its implementation required the suspension of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 and implied that all Aboriginal people were child-abusers, incapable of looking after their money or taking their children to school or for health checks.

This report was used by the Howard government to justify their discourse about a ‘crisis’ and the highly intrusive actions of the Intervention, despite the fact that the report states of child sexual assault that ‘the problems do not just relate to Aboriginal communities. The number of perpetrators is small and there are some communities, it must be thought, where there are no problems at all’ (Northern Territory Government, 2007:6).

The Intervention was not dismantled by the Rudd Labor government, and the Gillard Labor government plans to extend it. The Intervention further marginalised and infuriated Indigenous people, and several Indigenous-led movements such as Roll Back the Intervention and Stop the Intervention) are working to have the Intervention dismantled (see Online resources).

In summary, as nurses it is crucial that you grasp that history has left its mark on Australian identity and attitudes towards the country’s traditional owners, as well as on the life chances of today’s Indigenous Australians whose ancestors [the old people] are revered in social memory (see Cox, 2007, 2009; Saggers and Gray, 1991; Tatz, 2001). Structural inequality was created and firmly entrenched by historical circumstances, and is reinforced by contemporary policies and practices that continue to discriminate against Indigenous people (such as the ‘Intervention’ mentioned above) that hinder their right to self-determination (see Brown and Brown, 2007).

The colonisation process for Māri, the indigenous people of New Zealand/Aotearoa, presented many parallel impacts to those discussed earlier for Australia; however, there are some differences. One of these differences was the British acknowledgement of Māri as indigenous people of the land (tangata whenua). However, despite this acknowledgement the devastatingly negative biological and social effects of colonisation were not lessened (Durie, 1994). Dishonest purchasing of land, land wars and the introduction of diseases for which Māri had little or no immunity had impacts on the population numbers of Māri. Other consequences were impoverishment for many and the breakdown of Māri social structure, culture, language, life chances and health (Kearns and others, 2009). In an attempt to recognise the legal rights of Māri and enable the British to colonise New Zealand/Aotearoa in 1840, representatives of the British Crown and representatives of many of the multiple iwi (tribes) and hapu– (sub-tribes) of New Zealand/Aotearoa signed a treaty called the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti O Waitangi. Although the Treaty of Waitangi conferred on British settlers the right to settle in New Zealand/Aotearoa, it also created a corresponding duty on the Crown to ensure Māri retained their existing property and citizenship rights (Durie, 1994).

Unfortunately, there were discrepancies between the Māri and British translations of the Treaty that were not initially recognised. Kingi (2007:5) states that ‘while the objectives of the Treaty were in part designed as a platform for Māri health development, based on the continued population decline, it proved to be less than successful. In fact, the 1800s was a century characterised by significant and sustained Māri de-population’. This outcome was perhaps related to the fact that the intent and provisions of the Treaty were largely ignored until the 1970s, when a tribunal was eventually formed to ensure that the government and statutory bodies upheld their responsibilities as stated by the Treaty. The introduction of the Waitangi Tribunal Act in 1975 ensured a refocus on reparations to Māri, compelling the government to acknowledge the importance of the Crown’s relationship with Māri (see Online resources).

The Treaty of Waitangi nowadays offers a mechanism for rectifying some of the consequences of colonisation, and provides a set of three principles for all New Zealanders to follow. These principles are outlined in the New Zealand Royal Commission on Social Policy’s (1988) report as partnership, participation and protection (Ministry of Health, 2004). Thus, partnership means working together with iwi, hapu–, Whaānau and Māri communities to develop strategies for Māri health gain and appropriate health and disability services; participation at all levels means involving Māri at all levels of the sector in decision making, planning, development and delivery of health and disability services; and protection and improvement of Māri health status means working to ensure Māri have at least the same level of health as non-Māri, and safeguarding Māri cultural concepts, values and practices. Overall, then, while New Zealand/Aotearoa had a colonial experience different from that of Australia, the process of colonisation still resulted in the loss of economic resources, the creation of structural inequality and widespread institutional racism just as equivalent processes in Australia did for Indigenous people.

Although Australian and New Zealand/Aotearoa societies may be described as multicultural, it is important to acknowledge the status of indigenous people in both societies as the original owners and not gather them under the ‘multicultural’ umbrella as just another ethnicity among many. In Australia, Indigenous peoples constitute 2.5% of the total population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2007a). However, over the past 223 years many immigrants from various parts of the world have made Australia their home. The 2006 Australian Census indicated that 22% of the population was born overseas (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2007b). Further, over the past three years, net overseas migration (NOM) has more than doubled from 146,800 people in 2005–06 to a preliminary NOM estimate of 298,900 people in 2008–09, the highest on record for a financial year (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010a). Initially, immigrants came predominantly from Britain and Ireland and then Europe, but there has been a significant increase in the proportion of immigrants from Asia. The 2006 New Zealand Population Census found that Māri constitute 15% of the total population, 10% of the population is of Asian descent and 23% of the population was born overseas (Ministry of Social Development, 2010).

Despite such cultural diversity in Australia and, to a similar degree, New Zealand/Aotearoa, it should be remembered that cultural diversity does not mean that either country is marked by structural diversity. The dominant language and the underlying philosophies and practices within the mainstream legal, political, educational, agricultural and health institutions in both countries are monocultural—they derive from one source, Britain, and are often referred to by the broad and generic term ‘Western’. This is therefore the context in which nursing practice occurs. In nursing you will encounter client beliefs and values that appear, or indeed are, inconsistent and at odds with practices of Western medicine and nursing philosophies. How nurses respond to clients’ beliefs and behaviours is strongly related to their own beliefs and values, and will determine how effective they are in caring for and promoting clients’ wellness (see Figure 17-1).

FIGURE 17-1 Ethnic and cultural diversity makes healthcare challenging and rewarding.

Images: (clockwise from top left): Dreamstime/Rsusanto, Getty Images/Ingetje Tadros, Shutterstock/Tatiana Morozova, Getty Images/David Kirkland, Shutterstock/Petro Feketa, Shutterstock/zhuda, Shutterstock/Tomasz Markowski, iStockphoto/Ian McDonnell.

It is consequently imperative that nurses understand concepts such as culture, class, ethnicity and biculturalism and the impact of culture contact and culture clash on health and health perceptions, if they intend to provide the best possible healthcare. For a start, let us reconsider culture, class and ethnicity and their influence on people’s life chances and health.

What is culture?

There have been many definitions of culture over the past 150 years, a fascinating discussion of which can be found in Rapport and Overing (2007). Many people assume incorrectly that culture only relates to a person’s ethnicity. Clearly, from our introductory comments on social constructionism, our understanding of culture is that culture does not just exist as an unproblematic, observable entity—culture is constructed by humans in attempts to understand their experience and to give it meaning. It is constructed socially, i.e. in the space between people who live in networks of relationships characterised by power relationships. Cultures are contextual, dynamic, strategic and messy, not static systems practised to an equal degree by everyone who identifies as belonging to a particular culture. Many definitions emphasise notions of culture as learned, shared and complex. However, such definitions of culture, usually summed up by the term ‘worldview’, emphasise idealised cultures (normative culture) rather than the lived experience of everyday life (descriptive culture) which is much more relevant for the interaction between culture and healthcare. Rapport and Overing (2007:113) cite Wagner’s critique of the ‘idea of shared, stable systems of collective representations’ which ‘instead lives a constant flux of continual re-creation’.

Thus everyday lived experience shows that while some aspects of culture may be shared, other aspects are highly contested and heterogeneous. We need only think of the term ‘Australian’ as a cultural identifier to realise how diverse Australians are in terms of attitudes, beliefs, values, practices, religions, languages and so on. Further, individuals can belong to many different cultures simultaneously and therefore have unique cultural needs that won’t be met by a nurse choosing to learn normative ideals (worldviews) of one of the cultures that a client might embrace. The person may alter their behaviour, language, conversational topics and body language depending upon the group they are identifying with at any given time. An example might be a person who identifies as European and Jewish and is a female, heterosexual nurse and from the upper-class. Can you see how this person might behave differently depending on which cultural groups/s she is interacting with at any particular time?

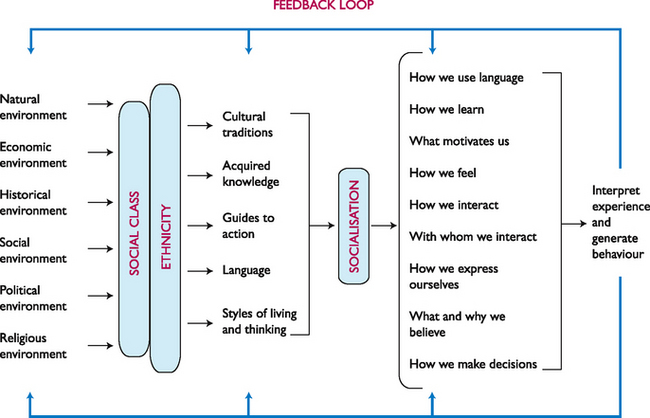

1. What cultural aspect of the person we’ve described above would you focus on? How would you provide care according to this person’s needs? Figure 17-2 sets out diagrammatically some of the many influences that shape cultures and an individual’s cultural identity.

2. Define what culture means to you. Explore more clearly the society to which you belong and the subgroup(s) influencing your actions, beliefs and values. What internal and external environments helped to shape the subgroup(s) with which you identify? Analyse how you prefer to learn, use language and interact, what motivates you, how you make decisions, how you express yourself and how and with whom you prefer to interact.

As indicated in the definition of culture in the opening quote on cultural safety, culture not only encompasses values, beliefs, religion and language but also class, ethnicity, education, employment, gender, sexual orientation and ability, which are affected by social, political, historical and natural environments. All of these factors influence what motivates people to interact, with whom they prefer to interact and in what way. However, another important part of the interaction between culture and health is that not all members of a society have equal access to power and resources: individuals from different social classes are afforded different opportunities—they have access to varying levels of power, are permitted varying levels of input into decision-making processes, and their power to change their life circumstances for the better varies greatly. We explore these issues further below.

The influence of whiteness

In both Australian and New Zealand/Aotearoa healthcare contexts the dominant philosophies stem from biomedicine, the ‘white’ way of doing things. Eckermann and others (2010), in referring to this concept of whiteness, cite Brodkin’s (1999) reference to ‘institutional privilege enjoyed by the dominant society’. That is to say, members of the white (or mainstream) culture are inheritors of unearned, unexamined and unacknowledged privilege. As we discussed earlier in understanding colonisation, the British way of life with its laws, its understandings and beliefs around health and illness, and resultant power and control became the prevailing ethos. Many problems arise from this way of thinking.

Have you ever been in a situation in your nursing education where a way of understanding a health issue from the perspective of the dominant white culture is discussed, and the educator turns to a student of different ethnicity and asks them to explain how this is understood in their ethnic group? What is happening when this occurs?

First of all the educator has not only given privilege to the dominant way of understanding the issue, but has also assumed that the ‘other’ student is representative of all ‘others’.

How would you respond if you were asked to speak for all people from the ethnic group you belong to? Could you do that?

The problem with whiteness is that every way of being is measured against it; whiteness is the privileged norm and therefore everything else is outside of the norm or seen as abnormal. A further problem with whiteness is intolerance of difference (Eckermann and others, 2010). People who do not fit the dominant cultural group are seen as ‘others’, being incompetent and needing help, which then leads to dependence, self-doubt and marginalisation. We return to the issue of ‘otherness’ and ‘othering’ in the section on culture clash and culture conflict, below.

The influence of class

In developed, first-world countries such as Australia and New Zealand/Aotearoa, people are categorised according to educational, social and economic factors into different classes, which are accorded different social status. Just like the culture concept discussed above, ‘class’ is another social construction created by people in the attempt to order, understand and control the world. Such categorisation of people into classes is known as social stratification—the ordering of society into groups or classes that have differential access to power, privilege and status. It is now well known that there are patterns of inequality in health and illness that can be better understood by focusing on the social dimensions of health such as class (see Willis and Elmer, 2011). As stated in Eckermann and others (2010:44), ‘This reality is in conflict with the egalitarian principles and ideologies of liberty and equality underlying most western industrial societies.’ As they go on to point out, it is certainly in conflict with the ideals of ‘mateship’ and ‘a fair go’ that are championed as characteristic of normative Australasian culture and it debunks the myth that Australia and New Zealand/Aotearoa are classless societies.

This myth was exploded by the sociologists Davies and Encel, who show that in Western societies people continue to be classified according to income, education and access to power ‘into upper middle class (including professional, technical and related workers, executive and managerial personnel), lower middle class (clerical and sales workers) and working class (blue-collar workers)’ (1987, cited in Eckermann and others, 2010:45). Each of these classes in society adheres to somewhat different cultural traditions—this is why the influence of class is highlighted as an aspect of culture that influences people’s values, traditions and beliefs. Further, people generally perceive, identify and ascribe a ‘value’ to classes on the basis of tangible as well as intangible criteria.

The impact of stratification is tremendous. Membership of a social class often determines whether an individual will or will not complete intermediate or higher education, avoid chances of becoming delinquent or acquire sufficient income to satisfy basic needs. Class, then, is one aspect of culture and an indicator of differential life chances. Another important aspect of culture is ethnicity. But how is it the same or different to culture?

Ethnicity—what is it?

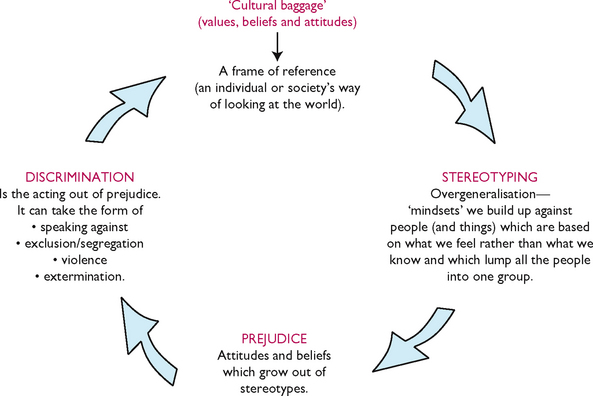

Basically, ethnicity is a label which describes our perceptions of self as identifying with a specific, defined group. Over the years, however, the term has become synonymous with ‘minority’ and has been used largely to eliminate labels such as ‘racial minorities’. Further, scientists (see Templeton, 2002, 2003; Willis and Elmer, 2011) have become aware of how inaccurate the concept ‘race’ is in terms of defining or categorising anyone. They stress how destructively the concept has seeped into people’s perceptions of others and the treatment of those who basically ‘look different’ by individuals and governments under various forms of racism. We discuss these further below. Consequently, ‘ethnicity’ has become the less emotive categorisation. By using such a label—even a neutral one—however, there is a tendency for those belonging to the dominant cultures in Australia and New Zealand/Aotearoa to express the dichotomy of ‘them’ and ‘us’. We are ‘us’—they are the ‘ethnics’. That leads to some confusion, because everyone has ‘ethnicity’. All people (notwithstanding experiences of removal and adoption) can trace specific ancestral roots that form their ethnicity.

Statistics New Zealand (2011a), in explaining ethnicity, states:

Ethnicity refers to the ethnic group or groups that people identify with or feel they belong to. Ethnicity is a measure of cultural affiliation, as opposed to race, ancestry, nationality, or citizenship. Ethnicity is self-perceived and people can affiliate with more than one ethnic group. An ethnic group is made up of people who have some or all of the following characteristics:

A person may therefore identify with some or all of these characteristics and may choose different ethnic affiliations at different times in their life. Thus, while concepts such as ‘ethnicity’ and ‘class’ are useful theoretical constructs, they can be too inclusive and broad to account for group differences and too static to account for change and adaptation. Members of ethnic groups also belong to a variety of classes, because no single ethnic group fits neatly into one specific class. Because class and ethnicity influence group and individual behaviour, it is difficult to unravel the influence of such interactive gross variables. Nevertheless, both class and ethnicity affect people’s life chances—and their health—which is the reason why we have specified ethnicity as yet another filter which affects the way we interpret experience and our reactions to our experiences. Clearly these factors affect both our individual worldview and our lifeworld. We examine these two concepts further below.

Worldviews and the lifeworld

All of us have a worldview. It is the framework we use to interpret and make meaning out of our world, the lens through which we view our experiences, think about the meaning and purpose of our lives and ponder how we got here, how the world came about, what happens after our bodily passing, whether humans are alone in the universe and many other metaphysical and existential matters. Rapport and Overing (2007) note that the term is the English translation of the German concept Weltanschauung, meaning our overall outlook, philosophy or conception of the world or, as Geertz (1973, cited in Rapport and Overing, 2007:432) would have it, ‘a way of thinking about the world and its workings’. Someone’s worldview may have aspects that are shared with others, but it will also have aspects that are unique to them alone, regardless of how they have been influenced by their socialisation in particular cultural and ethnic contexts. Nonetheless, people’s worldviews affect the way they act and think, their beliefs about right and wrong and their emotional reactions to what happens to them, such as getting sick, as well as their perceptions of people and things around them.

1. Talk to some of your peers to find out their worldviews. Are they different to yours?

2. What about your family members?

3. Think about how you have come to have similar or different worldviews.

4. Write down a few ways that the worldviews of clients might affect health.

5. Write down a few ways your worldview might affect your nursing care.

The challenge in nursing is to become aware of the personal cultural biases of one’s thoughts, particularly in relation to health and healthcare. Nurses interact with people throughout various stages of their life cycle, and in caring for them, they deal with a whole range of life events and problems. This is where Husserl’s phenomenological concept of the lifeworld comes into play, as the lifeworld is the everyday world in which people live their lives—‘lifeworld’ refers to the world as it is experienced (Dahlberg and Drew, 1997). From our discussion of class and power above, it is clear that even though people may live in the same society and even share a cultural identity their lifeworlds might be quite different to one another, being comprised of events, problems and circumstances that are not necessarily experienced by members of the same society, culture or even ethnicity.

1. Talk to some of your friends to find out about their lifeworlds. How do they experience their everyday worlds?

2. Is their experience different to yours?

3. What about your family members?

4. Think about how you have come to have similar or different lifeworlds.

5. Write down a few ways that the lifeworld of clients might affect health.

6. Write down a few ways your lifeworld might affect your nursing care.

It follows, then, that how both nurses and clients interpret and explain adverse events and problems is influenced by both their particular worldviews and the lifeworlds that inform their experiences. Nursing within, between and across cultures, therefore, requires nurses to at least achieve some empathy towards the worldviews and lifeworlds of their clients within their social context, since it is only from these that nurses can gain understanding of their clients’ illness and healthcare needs (see Research highlight). To examine this proposition further, we take a closer look now at how people construct their ideas of health.

What is health?

Health behaviours and care practices, be they lay or professional, usually reflect particular values and beliefs regarding health and the causes of illness and disease. Health, as we established earlier, is socially constructed, not a universally agreed condition. People’s understanding and expression of their health is embedded in their culture. Thus, definitions of health often differ not only between cultures but also within any one culture. In Chapter 16, health is defined and discussed at length. Holistic definitions such as that of the World Health Organization are reflected in those of organisations such as the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (see Online resources). In 1982 the precursor to NACCHO, the National Aboriginal and Islander Health Organisation (NAIHO), defined health as ‘not just the physical wellbeing of the individual but the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community’ (cited in Eckermann and others, 2010:64). This viewpoint is supported in New Zealand/Aotearoa, where the focus is on the synergy between people and the wider social, cultural, economic, political and physical environment (Durie, 2001).

Research abstract

Cancer mortality is higher for Indigenous Australians when compared with non-Indigenous Australians. Key issues are poor access to screening, treatment and support services. Research in Western Australia explored experiences of services and the barriers faced. Thirty interviews were undertaken with people from urban (n = 11), rural (n = 9) and remote (n = 7) areas.

Thematic analysis revealed that the participants’ main needs were for practical and emotional support throughout the treatment process. Specific issues include:

• financial aspects—tests, medication, transport, parking, food, accommodation

• problems with travel such as discomfort in entering areas where they had no formal invitation

• displacement from family and dealing with family responsibilities

• lack of information to prepare people for what to expect (new environment, treatment, follow-up, costs)

• lack of appropriate support persons—strong need for more Aboriginal interpreters or Aboriginal Liaison Officers, especially for ongoing support following discharge.

The researchers found that since most of the urban Aboriginal population lives on the fringes of Perth, they faced similar socioeconomic barriers as rural and remote participants which, however, were more extreme for remote participants. For some, not knowing their way around the large cities was likened to ‘landing on the moon’ (Shahid and others, 2011:237).

The study identified an important systemic issue where rules around access to health services was one of several issues that prevented family members accompanying relatives travelling from remote areas.

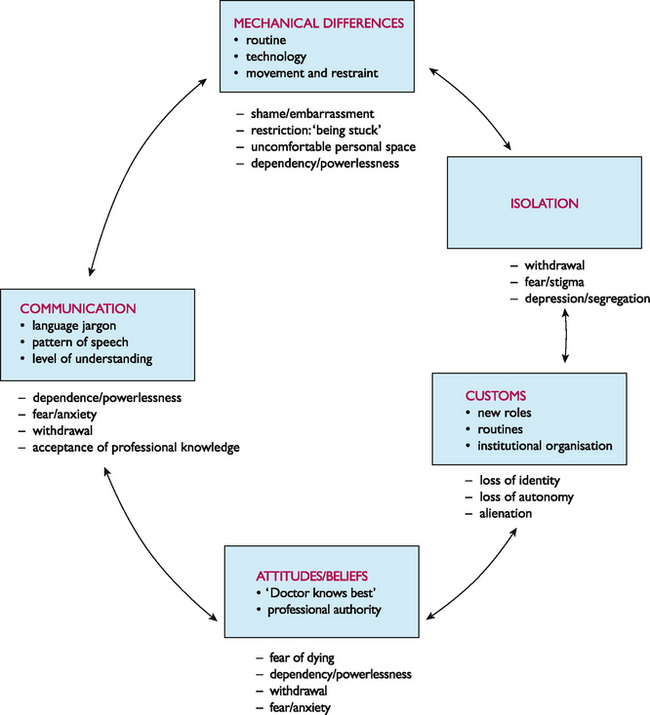

The hospital environment

Participants found the hospital alienating:

• loss of independence and dignity was disempowering

• inflexibility of the system to cope with extended families

• invasion of privacy, shame and discomfort during ward rounds.

‘One participant said her 84-year old grandfather “hated being heavily dependent on strangers’ in hospital as he was a proud independent man who disliked having to ask for things when he needed them; he hated being restricted to bed and detested the food’ (Shahid and others, 2011:238).

Researcher’s recommendations

1. Better management of costs—people avoid treatment if they feel they can’t afford it or bring family for needed support.

2. Improve hospital environments to minimise feelings of alienation and fear—more support persons and interpreters, artwork, places to sit and yarn, access to preferred foods.

3. Reduce the need to travel—have regionally based coordinators to link people to and between services.

In conclusion, it is often not remoteness in itself that is the actual problem. The problem is the lack of treatment infrastructure to meet clients’ needs to ensure they do not feel demeaned and demoralised.

Shahid S, et al. ‘Nowhere to room … nobody told them’: logistical and cultural impediments to Aboriginal peoples’ participation in cancer treatment, Aust Health Rev. 2011;35(2):235–241.http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/AH09835

The implications of these circumstances for nursing practice are that the way we meet clients’ needs is influenced by both our worldviews and our lifeworlds. Despite the awareness that cultural beliefs and life experiences influence how people understand sickness and health, some explanations of health and illness are more powerful than others. In New Zealand/Aotearoa and Australia the biomedical model is the dominant paradigm; it has the most legitimacy, both socially and politically. Within this model, health is defined merely as the absence of disease and the causes (aetiology) of illnesses are based on a decontextualised and mechanistic view of individual humans, rendering their unique worldviews and lifeworlds irrelevant to the medical enterprise. This paradigm is so entrenched and pervasive that it is difficult to provide any comparative analysis or critique (Willis and Elmer, 2011).

Nurses’ comprehension of the construction of health and illness is shaped by their socialisation into the profession and will, consequently, reflect the dominant biomedical ideology. Remember, culture represents a way of perceiving, behaving in and evaluating one’s world. It is learned, grounded in life circumstances and environment, and it is dynamic, forever changing. Just as we are socialised through our family and wider social environment into particular ways of being, perceiving and acting in the world (culture), so are we socialised into our profession through education and the idealised values and behaviours we accept as appropriate to our profession. In relation to health and care, the professional culture of nursing provides the blueprint or guide for determining a definition of health and associated values, beliefs and practices.

Think back now to our discussion on whiteness. Can you see any aspects of the dominant culture in your way of thinking or in your nursing practice? How might these aspects affect a person who is not considered part of that dominant culture?

However, another aspect to how each individual expresses their cultural being is their agency, i.e. humans are not cultural carbon-copies of one another or automatons; each of us acts on and in the world with the added dimension of free will. It is these dynamics that account for the fact that cultures, including professional cultures, can be described in both normative and descriptive terms; in terms of ideal professional values, beliefs and practices and in terms of what particular nurses actually value, believe and practise in the real world of their everyday working life.

Consequently, the worldviews of nurses and how they communicate these is influenced partly by professional socialisation and partly by the personal worldviews and lifeworlds that they bring to their profession. In the process of professional education, nurses acquire a whole range of symbols (medical jargon, linguistic shortcuts and specialist knowledge) that may not be readily understood by their clients. Thus Taylor and Guerin (2010:125–7) suggest that nurses, like other professionals, often assume that their clients share their professional symbols and knowledge, assumptions and beliefs, and that they can speak and understand the same (nursing/medical) language. This assumption can obviously lead to enormous misunderstandings. It is therefore crucial for nurses to reflect on:

• their personal cultural identity

• their assumptions about health and illness and people

• their personal definitions of health

• the client’s definition of health

• whose definitions are legitimised (by law and by society)

When nurses have reflected on these, they need to be clear about the attitudes, values, beliefs, practices and traditions acquired through their personal background and experiences and those of the culture of nursing. They may find that the ideal of treating everyone with respect and dignity might be harder for them to extend to some clients and their families than to others. Contact between people with differing cultural assumptions and circumstances is sometimes marked by suspicion, fear and self-doubt, and both nurses and clients and their families can experience such feelings when confronted with one another. However, being open to the client’s story of their illness, negotiating with them and, if appropriate, with others from within the client’s family, friends or cultural group can help to minimise these consequences. So too can thinking about cultural dynamics in more-complex ways, and we turn below to fuller consideration of these.