Chapter 16 Health and wellness

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Explain the socioecological approach to health.

• Discuss the difference between a biomedical, behavioural and socioecological approach to health.

• Discuss social determinants of health.

• Discuss how nurses can address health inequalities and social injustice.

• Explain and discuss the importance of understanding the concept of culturally safe nursing practice.

• Discuss the ways in which culture can shape health beliefs.

• Describe the ways in which strategies that constitute the Ottawa Charter for health promotion infiltrate proceeding health charters.

• Explain the three levels of preventive care.

• Discuss the key concepts of health literacy.

• Discuss the nurse’s role in promoting health and preventing illness.

• Explain the role of the World Health Organization in promoting health at a global level.

This chapter explores the many ways of understanding health and wellness. We build on the concepts introduced in Part 1, explaining the pivotal role nurses have in healthcare delivery, caring for people, families and communities. We will also challenge the common misunderstanding that people hold similar beliefs about health and wellness, when in reality people’s ideas and expectations about being healthy and well depend on many factors. These vary depending on family of origin; one’s culture; the environments in which people live, work and play; current life circumstances; and a wide range of personal beliefs, including the belief that people have control over their health status. As we introduce concepts in this chapter we would like you to think about how these ideas fit in with your understanding about health and wellness at both a personal and a professional level.

Thinking about health and wellness at a professional level, as a student nurse, doesn’t preclude you from having certain beliefs at a personal level. For example some nurses, despite knowing the health risk of recreational drug use, which includes alcohol and tobacco, choose to use these. To help you think through dilemmas such as these, critical thinking exercises at various points throughout the chapter provide you with an opportunity to stop, consider and critically reflect on the topic we’re discussing. In discovering new knowledge a certain tension can occur, as we tend to be comfortable with what we know, and find new knowledge and ideas challenging. Critical reflection and thinking encourages students to become self-initiating, self-correcting and self-evaluating (Doane and Varcoe, 2005). We have found that these three crucial learning processes enable students to become safe and competent practitioners, while taking care of themselves in the increasingly complex and uncertain world of healthcare. Thinking critically is necessary when constantly faced with new knowledge. Robinson and McCormick (2011) suggests that people who think critically can:

• identify and recognise the significance of a problem

• analyse a problem by taking it apart and examining it

Each step requires you to reason, to think through and come to a valid conclusion based on facts, evidence, experience and observation. Follow these steps, question the topics we explore, discuss these with your fellow students, family and friends, and as you do we hope you will find out what health and wellness beliefs and values are important to you.

We all have our own definition of what it is to be healthy. For some a regular gym workout is essential, for others a vegetarian diet, for others a glass of red wine. Many factors influence our thinking: family, friends and the health messages we receive. Without deliberately reflecting on complex issues such as health, we tend to be influenced and take on the dominant ideas of the society in which we live.

We would like you to think about what ‘being healthy’ means to you.

Just as we all have different ideas about being healthy and well at a personal level, so too do we as healthcare professionals. What is important to consider is how your personal definition of health could shape and possibly hinder the way you practise (Doane and Varcoe, 2005). We will explore these ideas by beginning with an in-depth look at the ways the two terms ‘health’ and ‘wellness’ are defined and used in nursing practice and healthcare.

Health and wellness

Health is defined in a number of ways, and often related to what we expect is healthy for our age, gender, current living situation, clinical history and previous health-related experiences. These in turn are shaped by concepts embedded in Western healthcare systems; illness, disease, diagnoses and treatment. If, however, we take the belief of McMurray and Clendon (2011) that healthy people’s lives are characterised by a sense of balance between their physical, emotional, social and spiritual health, our meaning extends to include what people are capable of, their social situation, their relationships, culture and family life. When completing a health assessment we need to avoid making assumptions; that is, believing something to be true without proof—easily done if we think in group norms or stereotypes.

People over the age of 80 years provide a salient example, as they are mostly portrayed as being either physically or mentally weak and frequently in need of healthcare and nursing care. Only recently we learned about the joy of living from an 82-year-old man, who after the death of his wife of many years came out as a gay man. He is currently planning an extended overseas trip for what he believes will be the last adventure left in him, giving him much satisfaction, happiness and a sense of wellbeing. What we believe and value about health and wellness—our needs, preferences, behaviours and goals—are frequently shaped by family, as are our sense of self, our self-concept and our self-esteem (Lindenmyer and others, 2010). Think back to the first critical thinking exercise: who, or what, helped form and shape your current health beliefs?

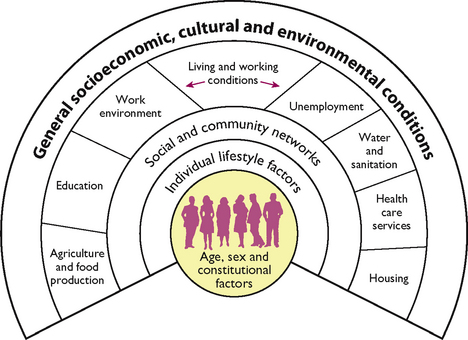

We’re beginning to see that health and wellness encompass far more than physical or mental health, despite many healthcare systems being organised by such categories. Interestingly, the World Health Organization (WHO, 1974:1) acknowledged this with their classic definition of health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. Encompassing health as a product of physical, psychological, cultural, spiritual and social factors, this definition has been critiqued by many as being unrealistic and inflexible. What this definition also neglected to do was to capture the dynamic nature of health (WHO, 1992). Health is not a static entity; rather, it constantly changes depending on the environment in which it occurs. On this basis the WHO revised its definition to include ‘health depends on our ability to understand and manage the interaction between human activities and the physical and biological environment’ (WHO, 1992:409). This broader definition of health, referred to as socioecological, gives a perspective that shifts our thinking from health being about individual responsibility and choice, to health being shaped by and connected to the contexts in which people live (Doane and Varcoe, 2005). Consequently, a person’s health is produced through a reciprocal or mutual exchange with the many environments (physical, social, cultural) in which people interact. Of particular importance is the social environment, as it provides the context through which people interact with all other environments (Figure 16-2).

FIGURE 16-2 Socioecological model of health.

From Dahlgren G, Whitehead M 1991 Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Background document to World Health Organization Strategy Paper for Europe. Stockholm, Institute for Futures Studies. Online. Available at http://ideas.repec.org/p/hhs/ifswps/2007_014.html 30 May 2012.

For example, when people live in a supportive social climate of trust, encouragement and mutual respect, and have education, financial and personal resources and adequate housing, they are well positioned to have some control over their lives and health. Whereas when social conditions are grim, plagued by illness, civil unrest, crime, poverty, unemployment, discrimination or other negative elements, people are less able to achieve health and wellbeing. Therefore, health according to Marmot and Wilkinson (2006) follows a social gradient. In other words, people who live in deprived circumstances have poorer health outcomes and often shorter lives than those who are economically more affluent.

The Black Report, on inequalities in health in Britain (Department of Health and Social Services, 1980), clearly illustrated this by identifying a widening gap in health inequalities between rich and poor communities. Over the decades following the Black Report, three further reports reached similar conclusions, including the latest (dealing with England): Fair society, healthy lives (Marmot, 2010). Little doubt remains today that the relationship between health and social disadvantage has major significance (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010), not only because of economic cost to many, but also because of social injustice caused by health inequalities.

By now you will start to understand why defining health and wellness is far from a simple task! The reports we’ve discussed describe Britain’s and England’s circumstances, but many countries suffer health inequalities, including Australia and New Zealand. In Western societies social issues continue to emerge as the gap between those with and those without economic resources grows.

Social determinants of health

Sir Michael Marmot, a world-renowned researcher and an advocate for reducing inequities in health, has spent many years examining the effects of social determinants of health, and just how the circumstances of people’s lives directly affects their health status. Marmot’s words ‘Social injustice is killing people on a grand scale’—were used to introduce the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) report ‘Closing the gap in a generation’ (CSDH, 2008) (Marmot chaired the Commission). This report promoted health equity through identifying the evidence and impact of the social determinants of health. From this report three principles of action, embedded in the recommendations, emerged:

• improve the conditions of daily life

• tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money and resources

• measure and understand the problem and assess the impact of action (CSDH, 2008).

The ‘Closing the gap in a generation’ report was closely followed by Marmot’s review of health inequities in England, ‘Fair society, healthy lives’ (Marmot, 2010). Marmot had no qualms in either report in stating that health inequalities—the unfair, unnecessary and avoidable differences in health between people within and between countries—develop through the social determinants of health, the circumstances in which people live (CSDH, 2008).

What are the social determinants of health?

Social determinants are the conditions of daily life, those in which people are born, grow, live, work and age; some are genetic, many more are socially constructed, and all are interwoven factors such as gender, genetic inheritance, ethnicity, income, education, housing, employment, access to health services and a sense of control over one’s life situation and environment (WHO, 2011a). One of the foundations of health—a sense of empowerment, of being able to have some control in decision making—occurs by participating in education, employment and the healthcare system. Experiencing inequality in (for example) income can lead to inequity, discrimination and unfairness, making social determinants closely bound up with the concept of social injustice; this, according to Marmot (CSDH, 2008), is for many a matter of life and death. Whereas ‘social justice, the fair distribution of society’s benefits, responsibilities and their consequences’ (Edwards and Davison, 2008:130) was once very much a part of public health interventions, evident in the Alma-Ata declaration (WHO, 1978) and the Ottawa Charter (WHO, 1986), the social justice agenda faded in the latter part of the 20th century (Edwards and Davison, 2008). And yet identifying health inequities, and social determinants of health, is key to tackling social injustice. A more recent commitment to the primary healthcare principle of universal access to healthcare when and where it is needed by the Australian and New Zealand governments (Department of Health and Ageing, 2011; Ministry of Health, 2011) could signal a renewed concern for social justice.

With the resurgence of primary healthcare (PHC) came the recognition that health inequities are not inevitable (Bell and others, 2010). Villeneuve (2008) and Smith (2007), among others, see part of the core business of nursing practice as working towards eliminating health inequities and changing the social conditions that influence health outcomes. Warm, dry, well-insulated homes, for example, give children a greater chance of having little or no respiratory health conditions. Such housing is, however, out of the reach of many people, especially families with limited economic resources. Social determinants are, after all, shaped by the society in which we live, where money, power and resources at a global, national and local level are distributed and in turn influenced by international, national and local policy decisions (Marmot, 2010; Robinson, 2009).

We will look briefly at how these ideas work through the determinant of gender, one that affects us every day of our lives. From the moment of birth, and some would argue before birth, the gender binary—the way society classifies us into two distinct groups, women and men—is enforced in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. Constructed and shaped by the way society expects women and men to behave (McGee, 2009), women in Western societies are expected to be gentle, nurturing and caring; men, on the other hand, are rewarded for being competitive, providing resources and leadership. Despite a few women in Australia and New Zealand holding leadership positions, including prime ministerial roles, in recent times, male hegemony remains the norm in both countries; to the detriment, it could be argued, of both women and men.

Putting aside the amount of unpaid work women complete in the domestic realm, women do much of the voluntary community work in New Zealand, and on average earn 80% of what men earn (Ministry of Women’s Affairs, 2010a). In state sector boards in New Zealand women hold 41.5% of positions, and yet only 9.3% of women are board members in the top 100 companies listed on the New Zealand stock exchange (NZX) (Ministry of Women’s Affairs, 2010b). A similar situation is found in Australia, where women hold only 9% of private board directorships (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2010). Using a socioecological lens, we can see that society shapes our understanding of gender roles through the distribution of power and resources at all levels. We see these ideas played out in the media. Women’s magazines devote pages to women’s health, covering all possible topics including nutrition, cervical cancer, endometriosis, menopause, heart disease—while neglecting the biggest threat to women’s health worldwide, one which knows no boundaries, be it age, ethnicity, socioeconomic standing: the issue of violence (Ratcliff, 2002). The latest Progress of the World’s Women report (UN Women, 2011) reinforces Ratcliff’s contention, as out of 22 developed nations identified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), New Zealand is ranked near the bottom for both domestic violence and maternal mortality. According to the WHO (2011b), in Australia, Canada, the United States and South Africa, 40–70% of female murder victims were killed by their partners. And the real tragedy of violence women experience is that everyone suffers, including children, women and men.

If nurses are serious about improving people’s health outcomes, gender inequality must be addressed; and yet, over the decades nurses have consistently shown a reluctance to address gender either with the people they care for, or for themselves at a professional level (McGee, 2009). Viewing healthcare practices through a medical lens, one that is embedded in nursing practice, tends to neglect the social and spiritual context of people’s lives. When it comes to exploring social and structural determinants, power and inequities, the use of a critical approach or ‘critical lens’ enables us to explore and understand people’s social context (Doane and Varcoe, 2005). When looking at power, culture, political decisions, economic position and social justice, a critical lens enables nurses to focus on and understand the way social determinants significantly affect people’s health status.

We have mentioned the role of the media in constructing gender social roles. Using a critical lens, we would like you to look at the language and images used in populist magazines and think about how these can influence people’s ideas, attitudes and behaviours. Also think about which groups are represented, and how. Are all ethnic groups shown; how visible are older people, or is the focus more on younger generations? Do these images represent the society in which you live?

Understanding how social determinants influence health outcomes is one thing; overcoming health inequalities is quite another. Government support from across the political spectrum and goodwill is needed at all levels. Fair society, healthy lives, Marmot’s (2010) strategic review of health inequalities in England, brings together the thinking of the past decade to set out an agenda of six policy objectives to reduce health inequalities (Box 16-1).

BOX 16-1 SIX POLICY OBJECTIVES TO REDUCE HEALTH INEQUALITIES

• Give every child the best start in life.

• Enable all children, young people and adults to maximise their capabilities and have control over their lives.

• Create fair employment and good work for all.

• Ensure healthy standard of living for all.

• Create and develop healthy and sustainable places and communities.

From Marmot M 2010 Fair society, healthy lives: the Marmot review, executive summary. London, The Marmot Review. Online. Available at www.instituteofhealthequity.org/projects/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review 30 May 2012.

Closer to home, Australia and New Zealand find themselves numbered 5 and 6 respectively out of 23 developed countries for income inequality, very close to the United Kingdom (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010). Income inequality within a country not only disadvantages those with very little resources but also affects all members of unequal societies. Wilkinson and Pickett’s (2010) list of social problems emerging from societies suffering income inequality (outlined in Box 16-2) all relate to health and wellbeing.

BOX 16-2 HEALTH AND SOCIAL PROBLEMS IDENTIFIED IN UNEQUAL SOCIETIES

• Mental illness (including drug and alcohol addictions)

• Life expectancy and infant mortality

From Wilkinson R, Pickett K 2010 The spirit level: why equality is better for everyone. London, Penguin.

Recognising the consequences of inequality in New Zealand, the government has begun to prioritise ways to reduce inequalities in social and economic circumstances, particularly for Māri, the indigenous people of New Zealand, and close neighbours, Pacific Islanders. In doing so the government acknowledges the unique relationship between Māri and the Crown based on New Zealand’s founding document the Treaty of Waitangi. Through this agreement, the government is committed to ensure that accessible and appropriate services are available to those who suffer most from health inequities (Ministry of Health, 2002a): people from lower socioeconomic groups, Māri and Pacific peoples.

Both the New Zealand and the Australian governments acknowledge that their indigenous people, as a result of being socially and economically disadvantaged, have a lower quality of life and die prematurely (Griew and others, 2007; Ministry of Health, 2010a). A range of interventions being taken to improve health outcomes include an increased number of primary healthcare initiatives, specifically targeting those with higher health needs (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010; Ministry of Health, 2002a).

Fundamental to considering the various aspects of health is to become sensitive to the different expectations between nurses and those they help. One person experiencing an acute injury or serious functional disability may consider themselves to be healthy, whereas another might see themselves as extremely unhealthy—indicating that people do not react to ill-health and accidents in the same way. People’s responses to health, ill-health and disability depend on many factors, in particular the social context of each person’s life at a particular point in time.

Taking all these ideas into consideration, how are we going to define health? Contemporary definitions from New Zealand and Australia incorporate, at a rhetorical level, a socioecological perspective as both countries see health as a dynamic concept; one constantly changing. However, an individual focus, embedded in the biomedical model of health which emphasises the presence or absence of disease and risk-related factors, remains dominant in both countries. Nevertheless, these two governments acknowledge the impact of social and economic determinants on health outcomes (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010; Ministry of Health, 2011). We will continue our exploration of a broader socioecological perspective of health a little later in the chapter. In the meantime, we focus briefly on the second key component of this chapter, wellbeing and wellness.

Wellbeing and wellness

Wellbeing, a critical component of health, is a subjective feeling of health, a sense of enjoyment, of happiness, and fulfilment. ‘Wellness’ was first coined by Dunn (1959:789) to explain the relationship people have with their environment to maintain balance and purpose in life; the two terms ‘health’ and ‘wellness’ are often conflated and used interchangeably. Wellness, Dunn (1977) believed, particularly high-level wellness, meant living life at maximum potential and in harmony with the particular circumstances of one’s life. This is not dissimilar to Robinson and McCormick’s (2011:31) contemporary definition of wellness as ‘the process of incorporating behaviours into your daily life to positively impact your health’.

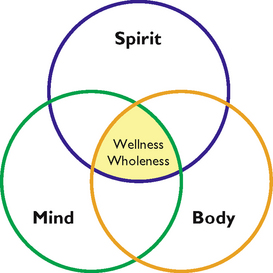

Just as health has many domains, so too does wellness; it includes personal, social, emotional, intellectual, environmental, cultural, spiritual and community wellness (Robinson and McCormick, 2011). The importance of each domain will depend on the circumstances of each person at a particular point in time, aligning well with a socioecological approach. Describing health and wellness as dynamic acknowledges the changing environments within a person (between mind, body and soul); the importance of positive relationships, both personal and professional (Yarwood, 2008); and an active engagement with external environments. Nevertheless, not all people have either the interest or the skills or resources to sustain beneficial relationships and actively seek wellness.

Your personal wellbeing, particularly in your professional life, is extremely important. You will work with people in times of good health and joy, as well as of illness, death, vulnerability, anger, fear or confusion. Part of learning to support people at such times in a constructive and positive manner involves developing strategies for self-coping and self-care (Anderson and Burgess, 2011). One way of doing so is to be prepared.

Think about a time or event when you felt anxious or stressed. What strategies and actions helped or didn’t help in this situation? Now reflect on what you did for yourself when you were upset, and what you did for others. Do we always treat ourselves as we would others?

What determines health and wellbeing?

Much of what we have discussed so far determines health and wellbeing. Nonetheless, there are other components that interact to influence our health status, including biology, family, culture and lifestyle choices.

Biology

From the time of conception, social determinants embed themselves in our biology to affect certain physiological control systems within us all. This set of controls interacts with the developing child’s environment to evolve and adapt to the many environmental stimuli we are exposed to throughout life. These interactions help establish cognitive, social and emotional coping skills, resiliencies and appropriate physiological responses to stressors and circumstances of daily life. Although each factor exerts a separate influence on health, the interaction between two or more and the body’s response will have the most profound impact on health. For example, a child born into an impoverished environment is disadvantaged in comparison to one whose social, physical and cultural environments enable their full potential to be achieved (McMurray and Clendon, 2011). Figure 16-3 illustrates the ways in which an impoverished environment can form a poverty cycle of interrelated elements.

Lifestyle choices

Instrumental in developing health and wellness are the lifestyle choices we make. For some these are made on the basis of personal preference, while for others the choices are limited by life circumstances. All choices are shaped, to some extent, by the context of people’s lives, including family, friends, and culture. For example, those who go out for a morning run may discover a sense of wellbeing in the beauty of a new day, the smells, the scenery and the solitude of the activity. For another, a more social venue like a gym for recreation would be preferred. Conversely, choices to be physically active for people with few economic resources and who live in an unsafe neighbourhood or have no child-minding facilities may well be limited. Therefore, health behaviours may be set and reinforced by previous experiences (either positive or negative), biological responses and life situations. Combined, these factors determine short-term and long-term lifestyle choices, and ways of coping with adversity or illness. Biology may act in a relatively positive or negative way, rendering people more resilient in the face of difficulties or conspiring to leave them in a poorer state of health than others in similar circumstances.

Family

Another key element contributing to health status is family. In the first critical thinking exercise where we asked you to consider your health definition, you may well have found that your family’s values, norms and conditions significantly contributed to your current thinking about health. Gender roles played out and shaped in families strongly influence health status. While traditional gender roles are changing as, for example, more men take on domestic and childcare responsibilities, these frequently remain women’s concerns. Gender can affect a person’s employability, which in turn can determine a family’s financial status. Family structure also influences financial opportunities, as does geographical mobility needed to seek employment, recreation or educational opportunities. Following decades of homogeneity in family structure, social norms have seen major changes in recent decades as traditional family structures are replaced by greater family diversity such as blended, gay and single-parent families (Families Commission, 2008). What is also vital for health and wellbeing in families, according to Hartrick Doane (2003:31), is how people come to experience:

• that they matter and that other people matter

• being loved and loving others

• being valued and how to value others

• a sense of belonging and connection to something more than themselves.

Nevertheless, we know that not all families provide nurturing environments, nor are there capabilities necessary to support all family members to flourish. Family violence and child abuse remain unresolved concerns worldwide, including in Australia and New Zealand and especially amongst indigenous families and those with few economic and social resources (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009; Ministry of Health, 2002b). Violence is one of a number of global social problems that Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) found prevalent in unequal societies, as shown in Box 16-2. What the following clinical thinking exercise does is reminds us of the dangers inherent in making assumptions in nursing practice.

Nico, 28 years old, has a Masters degree in Information Technology and works as a consultant for a large company. He lives in a major city where he owns a two-bedroom apartment, which he now shares with his girlfriend of four years, who is a marketing manager. Despite breaking up several times, their relationship has always been passionate. Last year Nico presented at the local emergency department with a broken nose, and more recently he was admitted after losing consciousness for several minutes following ‘tripping and banging his head on a coffee table’. Nico often appears at work sporting a black eye and various bruises due to ‘just being clumsy’.

Being aware of the gender characteristics society assigns to women and men would be crucial in your approach. What questions would you consider asking Nico and/or his girlfriend, and what strategies could you put in place to support them both?

Tackling these complex issues is fundamental to reducing health inequity. One new initiative in New Zealand is Whaānau Ora, a health service that enables Whaānau/families to build strengths and capabilities, and take responsibility for Whaānau/families with support from coherent, relevant and connected Whaānau services (Ministry of Health, 2010b).

Culture

Once seen as referring to a person’s ethnicity, the concept of culture nowadays, particularly in healthcare, recognises many different cultures, such as the culture of poverty, of age and of sexuality. McMurray and Clendon (2011:1) define culture as ‘the accumulation of beliefs, values, and knowledge that are determined from one generation to another and that determine social behaviour’. Nurses wanting to work effectively with people to preserve and value their cultural identity must first be aware of their own cultural attitudes, patterns of behaviour and language (Nursing Council of New Zealand, 2011). Respecting and protecting another’s culture, known as cultural safety, was first defined to acknowledge the importance of Māri, the indigenous people of New Zealand (see Chapter 17).

Evaluating whether care is culturally safe belongs to the person or family receiving the care, not the nurse (Richardson and Carryer, 2005). Cultural safety is not a matter of knowing about all cultures, but about being sensitive to and respectful of people’s/families’ differences, while recognising the social, physical and economic elements that may have impacts on their health (DeSouza, 2008). For example, despite legislative changes decriminalising homosexuality 20 years ago Neville and Adams (2010) believe a level of homophobia remains in primary healthcare in New Zealand, suggesting that some men may have difficulty receiving culturally safe healthcare.

Health literacy

Key elements in determining health and wellness include having the cognitive and social skills to seek out, understand, interpret, evaluate and use health information and health services (Robinson and McCormick, 2011). Just as we need to stay abreast of changing communication and advances in information technology (IT), so too must we maintain health literacy (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Health-literate people read critically and understand health promotion messages, treatment options, what services are available and healthcare professionals’ instructions, and are more likely to explore and use multiple websites and populist media. However, being health-literate is more than just being able to read health pamphlets and access relevant health services. Also necessary is self-efficacy: the ability to make key decisions about health and wellness, to provide a sense of empowerment, a feeling of personal control over one’s life, of having power to make decisions.

Self-efficacy allows people to engage in and navigate healthcare systems, a key characteristic of health literacy. People with limited reading or comprehension skills are disadvantaged, as health information is mostly presented in a written format. While popular media such as television, the internet and other digital media devices are increasingly being used to broadcast health promotion messages, without additional support many people may not consider that these messages apply to their situation. Inadequate use of health services and poor health outcomes are associated with low health literacy rates (Berkman and others, 2011). Improved access to health information, and the capacity to use it effectively, bestows personal and social benefits, particularly within the context of family. Health-literate parents grow health-literate children, who in turn grow health-literate communities and societies. If we think back to the discussion about social determinants of health, it is clear that without a certain level of education people are disadvantaged when it comes to making health decisions. Helping people to develop health literacy skills is a challenge for nurses, but one that goes hand in hand with assessing people’s health and wellness needs.

To finish this section, we briefly look at assessing people’s health needs. Thoughtful, evidence-based nursing practice is foremost about meeting people’s health needs and preferences within the context of each person’s life. Identifying health needs involves several steps.

First, an examination of various indicators of personal health, such as a health history, vital signs readings, weight, height, diet and physical activity levels. Second, an understanding of health beliefs; a person’s ideas, convictions and attitudes about health and illness based on factual information, misinformation, common sense, cultural beliefs, myths or differing expectations affect health behaviours. Positive health behaviours, such as sufficient sleep, taking exercise and having an adequate, nutritious diet, are about achieving, maintaining or regaining good health and preventing illness. Smoking, drug or alcohol abuse, poor diet, little or no physical activity and/or refusal to take necessary medications—negative health behaviours—are potentially harmful to health. Understanding people’s health beliefs, their attitude towards health behaviours and the extent to which they believe themselves to be healthy and/or capable of meeting their health needs is essential.

The third step is to link people’s information with known health risks for their population group. For example, providing someone suffering a chronic health condition with a clear rationale of the benefits of having a flu vaccination enables them to make a fully informed decision. The final step, a community assessment, explores available resources and barriers to health to determine people’s access to appropriate environmental supports (e.g. recreational facilities, health services for their particular needs). All of this is completed while keeping in mind the social determinants of health.

Having navigated our way through what constitutes health and wellness, we move to exploring nurses’ roles in promoting health and wellness and preventing disease, at both a personal and a population level.

Promoting health and wellness

Effective strategies for promoting health and wellness within the context of people’s lives involve understanding motivating factors and cues to action. For example, a screening questionnaire completed anonymously in the workplace was a motivating cue for adult workers to undergo colorectal cancer screening (Greenwald, 2006). Another intriguing study revealed that 13- to 19-year-olds believed they had little control over fertility in adulthood, consequently failing to see the link between sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and fertility (Trent and others, 2006). The cue for action from these findings was health education programs that not only emphasised the short-term consequences of STIs, but also how STIs could reduce future fertility (Trent and others, 2006). Understanding women’s reasons for stopping a particular contraceptive method (perceived barriers: nausea; difficulty taking at regular times; misconceptions about long-term fertility) in another study led healthcare professionals to suggest alternatives. A cue to action instigated change to a more reliable contraception method, increasing women’s self-efficacy as they considered different methods as part of making a reasoned decision (Brown and others, 2011). Promoting health and wellness at an individual level involves preventing disease, which we will briefly describe before discussing health promotion at a community and population level.

Preventive care

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. (Morgan and Simmons, 2009:174)

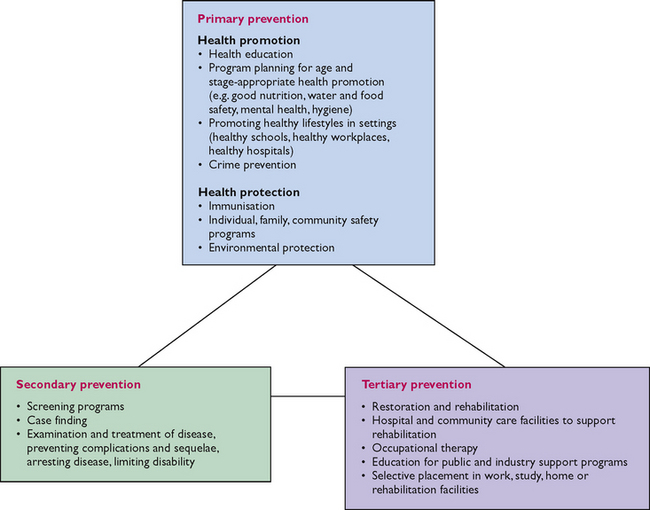

Disease prevention has and continues to be an integral part of nursing practice at an individual level; the three-tiered model of disease prevention outlined in Figure 16-4 guides nursing practice towards an approach where people’s health needs are comprehensively met by:

• considering ways to intervene to keep people healthy—primary level

• intervening to help those ill or injured—secondary level

• working to find ways of restoring and rehabilitating people in ways that reduce a relapse of illness or further injury—tertiary level (Stanhope and Lancaster, 2010).

FIGURE 16-4 Modification of the three levels of prevention.

Data adapted from Leavell H, Clark AE 1965 Preventive medicine for the doctor in his community, ed 3. New York, McGraw-Hill. Reproduced with the permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies.

Primary prevention promotes and maintains people’s health by identifying and removing the causes and determinants of ill-health or injury. Vaccinating children against communicable childhood diseases, encouraging people to exercise regularly and fostering good nutrition from an early age are all examples. Nurses engage secondary prevention strategies to detect health risks as early as possible and screen for early signs of disease. Screening programs, an accepted part of disease prevention from birth to death, include child and school health clinics, ‘well woman’ clinics offering free national cervical and mammography screening programs, and ‘well man’ health clinics offering health assessments in the form of ‘warrant of fitness’ programs (Cassie, 2010).

Whereas primary and secondary strategies aim to prevent disease, tertiary prevention springs into action once disease or injury is obvious, to focus on rehabilitation and recovery by interrupting the progress of the disease and thus reducing disability. Reducing the risk of postoperative problems such as deep vein thrombosis is an example, as is preventing pressure ulcers for people in long-term care.

Undertaking primary, secondary and tertiary prevention strategies requires an understanding of health risk, ‘a factor that raises the probability of adverse health outcomes’ (WHO, 2009) and risk factors. Risk factors are any habit, social or environmental condition that increases a person’s vulnerability to illness or injury, such as violence. They may be genetic and physiological, and can include family, age and gender; or be related to the social, cultural or physical environment, such as housing, income, education and/or relationships. Personal attitudes and behaviour can also be risk factors; some of which can be intentional, e.g. undertaking extreme sports or smoking tobacco, or unintentional, e.g. not eating fruit and vegetables, being physically inactive or living in cold, damp housing.

Common preventable risk factors at a population level are being seen in the context of an increasing burden of disease many countries experience from chronic disease conditions, also referred to as non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, diabetes and cancers (WHO, 2011b). Given that many of these conditions are preventable, nurses’ roles with education, support and encouragement are key to addressing the well-known associated health and economic costs of tobacco use, poor nutrition, alcohol abuse and little or no regular exercise physical (WHO, 2008). Nonetheless, as we have seen throughout this chapter health is far more than risk factors and disease prevention at a personal and a population level. Starfield and others (2008) question the continued focus on prevention and risk factors of specific disease when so many people lack adequate access to basic healthcare. To meet the healthcare needs of all, Starfield and others (2008) argue that prevention must extend to involve political and policy intervention, social relationships and community input. Similar sentiments are expressed by the WHO (2011b) in four essential elements to ease the burden of disease:

• supporting a paradigm shift towards integrated, preventive healthcare

• promoting financing systems and policies that support prevention in healthcare

• equipping patients with needed information, motivation, and skills in prevention and self-management

• making prevention an element of every healthcare interaction.

To illustrate the importance of prevention being a key component of healthcare we need look no further than the burden of disease carried by Australia and New Zealand. Both countries are defined as high-income countries by the World Bank (WHO, 2009) and yet they are burdened with chronic preventable diseases, the leading three being cardiovascular, cerebrovascular disease (such as stroke), diabetes and respiratory cancers. Years of prevention messages such as the importance of physical activity, not smoking and a good diet appear to have failed many. Without an understanding and modification of negative environmental factors, such as heavy advertising of fast foods and alcohol, easy access to alcohol and the increasingly high cost of fruit and vegetables, the burden of disease is unlikely to decrease according the WHO’s (2009) report updating global health risks.

Health promotion at a community and population level

In addition to assisting people with personal health promotion and disease prevention goals, another main area of nursing intervention lies with promoting healthy communities (see Chapter 43). Since the Declaration of Alma-Ata (WHO, 1978), the WHO has taken a pivotal role in promoting health for all. The most widely known model, the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO, 1986), signalled a change in thinking from a predominantly medical to a socioecological approach, acknowledging that health is deeply embedded in what it is to be human and in social structures (Doane and Varcoe, 2005). The WHO identified essential prerequisites for health, which resonate strongly with the social determinants discussed earlier in this chapter (see Box 16-3).

BOX 16-3 PREREQUISITES FOR HEALTH PROMOTION

From World Health Organization (WHO) 1986 The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Geneva, WHO. Online. Available at www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en 8 Sep 2011.

Five major strategies make up the Ottawa Charter, illustrating health promotion activities that assist communities in working towards better health outcomes: healthy public policy, creation of supportive environments, strengthening of community action, development of personal skills and reorientation of health services (Table 16-1).

TABLE 16-1 SUMMARY OF THE FIVE STRATEGIES OF THE OTTAWA CHARTER

| STRATEGY | FEATURES OF STRATEGY |

|---|---|

| Build healthy public policy | |

| Create supportive environments | Conserve and capitalise on physical, social and ecological resources and environments |

| Strengthen community action | Enable community planning and informed choices for better health |

| Develop personal skills | Develop and support individual health skill knowledge and practice |

| Reorient health services |

Healthy public policy

Health public policy ensures that health is uppermost in the mind of all policy makers. Healthcare professionals often see first-hand the health concerns people face every day where they live and work. Consequently, healthcare professionals need to be involved in health issues affecting community, local and national government politics and policy development. Ensuring safe roads, sufficient recreational facilities, green spaces, pollution-free towns and cities, safe and clean working environments and industries, health education curricula, public transport, social welfare and, of course, adequate healthcare facilities provide some examples.

Creation of supportive environments

The inextricable link between people and their environment is recognised in the second strategy to encourage us to support and look out for each other, our communities and the cities in which we live, to ensure equality and a commitment to the poorest members of the community and to reduce specific health issues experienced by minority groups and people with disabilities. To enable people to be healthy, this strategy encourages all people to recognise the importance of conserving and sustaining physical and social resources.

Strengthening of community action

Community ownership and control over their endeavours and destinies are at the heart of the third strategy. Empowering communities to make informed choices for better health involves healthcare professionals adopting the role of support person and facilitator, while providing information and learning opportunities.

Development of personal skills

Providing adequate and appropriate education and opportunities for skill-development guides the fourth strategy to enable people to support their communities in local decision making for effective use of resources to attain health.

Reorientation of health services

To shift the focus from managing illness to promoting health, preventing illness and providing healthy environments, the final strategy calls for an acknowledgement of local and cultural needs. This call challenges healthcare professionals to provide people, families and communities with tools to self-manage their healthcare, reduce reliance on health services and facilitate self-efficacy.

Each of these strategies calls for nurses to be involved in policy development, as only through political processes can meaningful change occur. Nurses’ involvement with people, families and communities places them in the best position to argue for well-thought-out, practical and effective health policy interventions, ones that can work towards eliminating health inequities (Villeneuve, 2008).

Following on from the Ottawa Charter, international health-promotion conferences held at regular intervals have endorsed and developed this charter’s five strategies. Charters emerging from each conference were named after the country in which each conference was held (Box 16-4).

BOX 16-4 TIMELINE OF INTERNATIONAL HEALTH CONFERENCES ON HEALTH PROMOTION

| 1986 | 1st global conference The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion | Ottawa, Canada, 17–21 November |

| 1988 | 2nd global conference Adelaide Recommendations on Healthy Public Policy | Adelaide, Australia, 5–9 April |

| 1991 | 3rd global conference Supportive Environments for Health | Sundsvall, Sweden, 9–15 June |

| 1997 | 4th global conference The Jakarta Declaration: New Players for a New Era—Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century | Jakarta, Indonesia, 21–25 July |

| 2000 | 5th global conference Health Promotion: Bridging the Equity Gap | Mexico City, Mexico, 5–9 June |

| 2005 | 6th global conference The Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World | Bangkok, Thailand, 7–11 August |

| 2009 | 7th global conference Nairobi Charter: Promoting Health and Development—Closing the implementation gap | Nairobi, Kenya, 26–30 October |

The 4th International Conference on Health Promotion, the Jakarta Declaration, directed health promotion towards social responsibility for health. A plea was made to reframe health as an investment in the future, establish partnerships between healthcare professionals and communities to achieve health and advocate for community empowerment (WHO, 1997). By investing in people and their health, communities can help build social capital, a concept that, while difficult to define, involves encouraging community relationships, social cohesion and trust to give people a sense of belonging and connection (Ching-Hsing, 2008). Networks of social ties, often families or communities, are emphasised in social capital, which encompasses people cooperating collectively to achieve common goals such as safe neighbourhoods or providing community facilities (Goodrich and Sampson, 2008). The decline in social capital occurring since the late 1980s (Putman, 2000) has more recently been linked to poorer health outcomes and the widening gap between those with and those without economic and health resources (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010). The Jakarta Declaration identified poverty as the single greatest threat to health, and reinforced the five strategies of the Ottawa Charter to create equal opportunities for health and health promotion at a global level (WHO, 1999).

Underlining the need for a focus on global health promotion, the Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalised World (WHO, 2005) drew attention to social life as a source of health or ill-health globally. This Charter, in underlining the need for interventions to counter social changes affecting working conditions, learning environments, family patterns and the culture and social fabric of communities, took a more socioecological approach to global health. Nurses and all healthcare professionals were urged to understand the importance of good governance, tolerant and trusting societies and fair corporate practices including world trade and financing (WHO, 2005).

The most recent charter, the Nairobi Global Conference on Health Promotion held in Kenya in 2009, being mindful of recent global events affecting the health and development of so many countries, builds on the work of the international health community. Global warming, climate change, terrorism and the ongoing financial crises embroiling many countries were identified as continuing to jeopardise health for many. Ensuring that health promotion remains a key component of each country’s health mandate, along with strong leadership capacity, was identified as crucial to forge ahead with institutionalised health promotion (WHO, 2011c).

Just before we look at how culture influences health promotion, we would like you to think about how the biomedical model—a model that has dominated nursing practice in Western countries with its individual focus on disease, diagnosis and treatment—influences our health beliefs. An increasing diaspora and immigration from Eastern countries finds a wide range of ethnic groups settling in New Zealand and Australia, all with their own cultures including their own health beliefs, values and behaviours.

Keeping in mind the concept of cultural safety that we discussed above, make two lists: one identifying the health values in Western countries, and one listing what you know about Eastern countries’ health practices. For example, ‘karma’ and ‘yin and yang’ are familiar terms in the English language—what do they mean to you? Have you heard the phrase ‘Insha’Allah’ (the will of God)? Consider what this phrase may mean in your nursing practice.

Cultural influences on health promotion

Understanding how culture influences a person’s response to health and illness and their acceptance or not of health-promotion programs and strategies is essential when responding sensitively to people’s health needs. In-depth coverage of the vast range of cultural influences on health-seeking behaviours is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the following discussion aims to give you an insight into key concepts of Chinese and Islam cultures. From a global perspective, China has the largest population at just under 1.5 billion people, who for many generations have migrated around the globe. Islam is the world’s fastest-growing religion with Muslims, followers of Islam, also living in countries across the globe, with increasing numbers choosing to live in Australia and New Zealand.

Western healthcare, with its biomedical orientation, is centred on an individualistic cultural orientation (Chun and others, 2011) promoting independence, reliance on people to take responsibility for their own illness prevention, illness recovery and ongoing disease management. If illness does occur, there is largely a reliance on physical management, often through invasive diagnostic procedures such as diagnostic tests, surgery and pharmaceuticals.

Chinese culture

Whereas Western healthcare has a strong focus on the mind/body split, the Chinese see the mind, body and spirit as being inextricably linked (Kwok and Sullivan, 2007). Health is reliant on the flow of the body’s vitality (qi), balance of opposing forces (yin–yang) and harmony in the main organs (wu-shing) (Ariff and Khoo, 2006). Controlling the flow of energy (qi-gong) with exercise such as meditation and rhythmic exercises including Tai Chi promotes qi and remove any blocks that may occur. Diet and traditional Chinese medicine are used to maintain or regain balance and harmony (Figure 16-5) (Davidson and others, 2003).

Many Chinese people value Western healthcare practices, especially surgical procedures, as a way of managing acute illness (Pang and others, 2003). However, there is a belief that Western medicine is aggressive, can cause side effects and imbalance and does not care for the ‘whole person’, leading to the belief that such care should only be sought in times of serious illness, often after traditional medicines have been tried (Kwok and Sullivan, 2007). Seeking health interventions without symptoms is a difficult concept for many Chinese people to comprehend, a key factor identified in the low uptake of health-screening programs (Goa and others, 2008; Kwok and others, 2010). While Chinese people are generally self-motivated to manage their health, this is set within a social context where there is heavy reliance on family and community support to achieve health and wellness (Chun and others, 2011).

Islamic culture

Unlike Western and Chinese cultures, which are based on geographical traditions and philosophical underpinnings, Islamic influences on health are set within the religious doctrines of Allah (God), as interpreted and set down by the last prophet, Mohammed. Muslims can have what appears to be a conflicting attitude to health by holding both a fatalistic attitude to their health and an expectation to care for the body, which is on loan from Allah and as such must be well cared for (Sheik and Gatrad, 2008). Insha’Allah—if it be the will of God—is the cornerstone belief of Muslims. This leads to a fatalistic approach to health and life (Hjelm and others, 2009), as it is God who determines who will get ill and who will recover, and only God has any control over the time of death. Many Muslims believe that illness of any kind is God’s will and a way of testing their belief in God (Padela and others, 2011).

Together with the need to accept God’s will, the Prophet Mohammed conveyed that ‘There is a cure for every malady save one—that of old age’, charging every Muslim to take responsibility to seek out a remedy for what ails them. The Prophet Mohammed also prophesied ‘that whosoever saves a human life, it is as if they have saved the whole of humankind’, ensuring that Muslims hold medical staff in high regard (Ahmed, 2008). Muslims are more inclined to seek expert help with care rather than be self-caring (Hjelm and others, 2009).

As Muslims see the mind, body and spirit as inextricably linked (Figure 16-6), their definition of symptoms such as ‘aches and pains’ or ‘chest pain’ are more likely to refer to distress, anxiety or depression (Ahmed, 2008). Although there are differences in Muslim and Chinese health beliefs, a three-fold balance between body, mind and soul is fundamental to both. In Western culture, with its individualistic orientation and despite the rhetoric of holistic healthcare, the spirit is generally neglected. Having said that, it is important to remember that stereotyping or making assumptions about people’s health beliefs, attitudes, values and behaviour will only impede a nurse’s ability to create a therapeutic relationship.

Promoting health in Australia and New Zealand

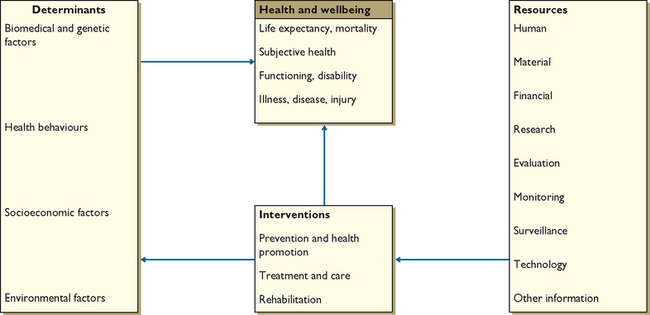

To finish our discussion about health and wellness, we take a brief look at the Australian and New Zealand governments’ conceptual frameworks for promoting the health needs of individuals, population groups and the population as a whole (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010; Ministry of Health, 2000, 2001). Embedded in each government’s health mandate, to a greater or lesser degree, are the Ottawa Charter’s five health-promotion strategies. See if you can identify which strategy the following governmental policies relate to: the state of roads, the level of allowable car exhaust emissions, carbon tax, the compulsory wearing of seatbelts and bicycle helmets and the use of child safety seats. Other political variables embedded in economic strategies include allocating various proportions of the budget to military initiatives, childcare and immunisation programs, the health of refugees or feeding the homeless. Political structures therefore determine health policies, which in turn influence how accessible health services are, and the range of choices available that either encourage or deter people from taking preventive measures or seeking timely treatment for illness. Australia’s conceptual framework elaborates on health determinants, including social determinants and components of health and wellness.

FIGURE 16-7 Conceptual framework for Australia’s health 2010.

Redrawn from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2010 Australia’s health 2010. Cat. no. AUS 122. Canberra, AIHW.

A strong government commitment to individual, social and economic interventions points to a government keen to ensure good health across population groups. The most significant interventions are, therefore, aimed at the social determinants of health, influencing education and income and providing choices for healthy living. A socioecological approach to activities in the healthcare system include efforts to help improve the physical, social and economic environment for those most at risk, those often marginalised and those most in need of support and encouragement. Such efforts involve strategies to help people develop personal skills, to exercise more control over their context, to make healthy choices and to have access to relevant and culturally appropriate services.

Just as the Australian government articulates the importance of improving health through addressing social determinants (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010), so too did the New Zealand Labour government when it launched the Primary Health Care Strategy, a framework to improve the health of all New Zealanders by reducing health inequalities (Ministry of Health, 2001). Using a population approach, the strategy aims to promote health and prevent chronic health conditions by working in conjunction with local communities. Evidence over the last decade has shown that although some aspects of this strategy have been achieved, while medicine remains the dominant healthcare model (Starfield, 2011) a collaborative approach to providing accessible, affordable and relevant healthcare remains challenging.

Whatever conceptual framework guides a healthcare system, economic policy and necessity drive health systems; and the current climate is no exception. Pressing health concerns associated with budgetary constraint are heart disease, obesity, stroke, diabetes and depression—all chronic health conditions, all mushrooming, and among the top six diseases in Australia and New Zealand (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011; Ministry of Health, 2011). Ageing populations are increasing in both countries, suggesting that a growing number of people will be living with more than one chronic condition for many years to come. If these conditions are not effectively prevented and managed, the WHO (2011b) believes, this burden of disease will create significant health and economic consequences for healthcare systems and their respective countries, including Australia and New Zealand.

Currently, most healthcare systems are so busy responding to the acute and urgent healthcare demands of the burden of disease that little time or attention is given to informing people about ways to promote health and prevent disease prevention (WHO, 2011b). With PHC driving healthcare delivery more recently in Australia and New Zealand (Department of Health and Ageing, 2011; Ministry of Health, 2011), opportunities to view health through a socioecological lens will allow people’s life circumstances to be recognised and addressed.

To reduce inequity, which Starfield (2011) believes is embedded in Western healthcare systems, with its focus on disease rather than people, healthcare professionals are urged to explore the context of people’s lives rather than the disease. To do so would take courage and leadership, steps emerging and encouraged from the latest global conference, the Nairobi Call to Action (WHO, 2009).

Several of the ideas we have discussed are brought together in this final clinical thinking exercise for you, as a nursing student, to consider how best a registered nurse could support Mia.

Mia, a 35-year-old mother of two children, is a registered nurse (RN) who works in a local rest home for the elderly. A smoker since leaving school, Mia stopped while pregnant with her first child 10 years ago. Shortly after discovering she was expecting her third child, her husband was diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer. Mia cared for him during his terminal illness, preventing her from working outside the home. Mia started smoking again. As a result of the stress she endured during this difficult time, and throughout her pregnancy, Shanti, her third child, was born 4 weeks early weighing only 2 kg. Now aged 5 years, Shanti has suffered ongoing respiratory problems requiring many hospital admissions. During these admissions, Mia has had to rely on neighbours to care for her two other children as her parents continue to work full-time. While Mia does not smoke when she is with the children, she is aware that her smoking is affecting her health and that of the children but feels unable to stop.

How could you help support Mia to stop smoking? And what other issues does she face? Are there specific nursing roles you can identify?

Far from being an individual pursuit, we have discovered that health and wellness are multifaceted, dynamic and involve each and every one of us, our families and communities. Despite Western societies being better off materially than ever before, social and health issues continue to rise as the gap between those with and those without economic and social resources widens, frequently leading to health inequities and social injustice. These concerns, alongside rapidly rising healthcare costs and burgeoning preventable chronic health conditions, offer nurses challenges well into the foreseeable future. Our understanding of what constitutes a healthy life expands and evolves as research in biology, genetics, nursing, medicine, behavioural and social sciences and public health continues. Increasingly, though, we understand health and wellness to be far more than the absence of disease; both are inextricably linked to the circumstances of people’s lives, their social and economic situation, their ability to access and comprehend health information, their relationships, their ideas and expectations about being healthy and their sense of self. Moreover, ‘positioning health and wellbeing as one of the key features of what constitutes a successful, inclusive and fair society in the 21st century is consistent with our commitment to human rights at national and international levels’ (WHO, 2011a).

KEY CONCEPTS

• A socioecological approach to health and wellness acknowledges the impact of social and economic determinants on health outcomes.

• Health, wellness and wellbeing are not merely the absence of disease and illness.

• A person’s state of health, wellness or illness depends on individual, environmental and cultural factors and the extent to which people are able to participate in health-related decision making.

• Health beliefs, attitudes and practices are influenced by a person’s social and environmental contexts.

• Health promotion activities help support the maintenance of health, prevent illness and restore or enhance health by building healthy public policy, creating supportive environments, strengthening community action, developing personal skills and reorienting healthcare systems.

• Health literacy develops along a continuum from functional, to communicative, to critical, to civic, and involves self-efficacy.

• Nursing practice incorporates health-promotion, wellness and illness-prevention activities in addition to treating illness.

• Illness prevention activities protect against threats to health and help overcome vulnerability to illness.

• Risk factors can threaten health and influence health practices, and are important considerations in illness-prevention activities.

• Improvement in health may involve a change in health attitudes and behaviours and changing social and environmental circumstances.

• Illness behaviour, like health practices, is influenced by many factors, especially social determinants of health, and must be considered by the nurse, in conjunction with people, when planning nursing care.

• Addressing health inequalities and social injustice is increasingly a component of nursing practice.

• Health, wellness and illness affect people and family members in many ways, including changes in behaviour and emotions, family roles, body image and self concept.

• The three levels of preventive care are primary (promoting and maintaining health), secondary (the early detection of disease or risk) and tertiary (preventing or minimising deterioration and complications when disease or disability is already established.

ONLINE RESOURCES

Australian Health Promotion Association, www.healthpromotion.org.au

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, www.aihw.gov.au

Department of Health and Ageing, www.health.gov.au

Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand, www.hauora.co.nz

HealthyPeople.org; site aimed at improving the health of Americans, www.healthypeople.gov kidshealth; providing information for parents and caregivers about children’s health, www.kidshealth.org.nz

New Zealand Ministry of Health Manatu– Haurora, www.moh.govt.nz

Nursing Council of New Zealand, www.nursingcouncil.org.nz

Public Health Association of Australia, www.phaa.net.au

Public Health Association of New Zealand, www.pha.org.nz

World Health Organization, www.who.int/enBangkok Charter, www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/6gchp/bangkok_charter/en Closing the gap in a generation; final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health, www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/en/index.htmlOttawa Charter, www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/enSocial determinants of health, www.who.int/social_determinants

UN Women, www.unwomen.org

Ahmed AA. Health and disease: an Islamic framework. In: Sheikh A, Gatrad AR, eds. Caring for Muslim patients. Oxford: Radcliffe, 2008.

Ariff KM, Khoo SB. Cultural health beliefs in a rural family practice: a Malaysian perspective. Aust J Rural Health. 2006;14:2–8.

Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). Gender equality blueprint. Sydney: AHRC, 2010. Online Available at www.humanrights.gov.au/sex_discrimination/publication/blueprint/index.html 6 Jun 2012.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). A picture of Australia’s children 2009. Canberra: AIHW, 2009. Online Available at www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468252 21 Aug 2011.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Australia’s health 2010, Cat. no. AUS 122. Canberra: AIHW, 2010. Online Available at www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468376&libID=6442468374 12 Aug 2011.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Chronic diseases. Canberra: AIHW, 2011. Online Available at www.aihw.gov.au/chronic-diseases 15 Aug 2011.

Anderson J, Burgess H. Developing emotional intelligence, resilience and skills for maintaining personal wellbeing in students of health and social care. Resource sheet. Lancaster: Mental Health in Higher Education, Lancaster University; and Southampton, Social Policy and Social Work (SWAP), University of Southampton, 2011. Online Available at www.mhhe.heacademy.ac.uk/silo/files/resilience-resource-sheet-for-mhhe-web.pdf 6 Jun 2012.

Bell R, et al. Global health governance: commission on social determinants of health and the imperative for change. J Law Med Ethics. 2010;38(3):470–475.

Berkman ND, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann Internal Med. 2011;155:129–130.

Brown W, et al. Breaking the barrier: the Health Belief Model and patient perceptions regarding contraception. Contraception. 2011;83:453–458.

Cassie F. Men’s health: more than throwing a pill. Nurs Rev. 2010;Nov:7–9.

Ching-Hsing H. A concept analysis of social capital within a health context. Nurs Forum. 2008;43(3):151–159.

Chun KM, et al. So we adapt step by step: acculturation experiences affecting diabetes management and perceived health for Chinese American immigrants. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:256–264.

Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. Online Available at www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/index.html 15 Jul 2011.

Davidson P, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine and heart disease: what does Western medicine and nursing science know about it? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2:171–181.

Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA). Improving primary health care for all Australians. Canberra: DoHA, 2011. Online Available at www.yourhealth.gov.au/internet/yourhealth/publishing.nsf/Content/improving-primary-health-care-for-all-australians-toc#.T8WvuI53EyE 30 May 2012.

Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS). Inequalities in health (the Black Report). London: DHSS, 1980. Online Available at www.sochealth.co.uk/Black/black.htm 29 Aug 2011.

DeSouza R. Wellness for all: the possibilities of cultural safety and cultural competence in New Zealand. J Res Nurs. 2008;13(2):125–135.

Doane G, Varcoe C. Family nursing as relational inquiry: developing health-promoting practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

Dunn HL. High-level wellness for man and society. Am J Public Health. 1959;49:786–792.

Dunn HL. What high-level wellness means. Health Values. 1977;1:9–16.

Edwards NC, Davison C. Social justice and core competencies for public health: improving the fit. Can J Public Health. 2008;99:130–132.

Families Commission. The Kiwi nest: 60 years of change in New Zealand families. Wellington: Families Commission, 2008. Online Available at www.nzfamilies.org.nz/sites/default/files/downloads/kiwi-nest.pdf 19 Dec 2011.

Goa W, et al. Factors affecting uptake of cervical cancer screening among Chinese women in New Zealand. J Gynaecol Obstetr. 2010;103:76–82.

Goodrich CG, Sampson KA. Strengthening rural families: an exploration of industry transformation, community and social capital. Wellington: Families Commission, 2008.

Greenwald B. Promoting community awareness of the need for colorectal cancer screening: a pilot study. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(2):134–141.

Griew R, Tilton E, Steward J, et al. Family centred primary health care. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2007. Online Available at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-oatsih-pubs-phc 6 Jun 2012.

Hartrick Doane G. Through pragmatic eyes: philosophy and the re-sourcing of family nursing. Nurs Philos. 2003;4:25–32.

Hjelm K, et al. Beliefs about health and illness postpartum in women born in Sweden and the Middle East. Midwifery. 2009;25:564–575.

Kwok C, Sullivan G. Health seeking behaviours among Chinese-Australian women: implications for health promotion programmes. Health (London). 2007;11:401–415.

Kwok C, et al. Chinese breast cancer screening beliefs questionnaire: development and psychometric testing with Chinese–Australian women. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:191–200.

Lindenmyer A, et al. ‘The family is part of the treatment really.’ A qualitative exploration of collective health narratives. Health. 2010;15:410–415.

Marmot M. Fair society, healthy lives: the Marmot review, executive summary. London: The Marmot Review, 2010. Online Available at www.instituteofhealthequity.org/projects/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review 30 May 2012.

Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Social determinants of health, ed 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

McGee P. Who says we’re all equal? Gender as an issue for nurses and nursing care. Contemp Nurse. 2009;33:98–101.

McMurray A, Clendon J. Community health and wellness: primary health care in practice. Sydney: Elsevier, 2011.

Ministry of Health. The New Zealand Health Strategy. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2000. Online. Available at www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-health-strategy 19 Dec 2011.

Ministry of Health. The primary health care strategy. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2001. Online Available at www.health.govt.nz/publication/primary-health-care-strategy 19 Dec 2011.

Ministry of Health. He Korowai Oranga: Maori Health Strategy. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2002. Online Available at www.health.govt.nz/publication/he-korowai-oranga-maori-health-strategy 19 Dec 2011.

Ministry of Health. Family violence intervention guidelines: child and partner abuse. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2002. Online Available at www.health.govt.nz/publication/family-violence-intervention-guidelines-child-and-partner-abuse-0 19 Dec 2011.

Ministry of Health. The social report. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2010. Online Available at http://socialreport.msd.govt.nz 21 Jul 2011.

Ministry of Health. Whānau Ora: integrated services delivery. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2010. Online Available at www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/whanau-ora 30 May 2012.

Ministry of Health. Better, sooner, more convenient health care in the community. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2011. Online Available at www.nationalhealthboard.govt.nz/sites/all/files/BSMC%20ebooklet.pdf 19 Dec 2011.

Ministry of Women’s Affairs. Indicators for change 2009: tracking the progress of New Zealand women. Wellington: Ministry of Women’s Affairs, 2010. Online Available at www.mwa.govt.nz/news-and-pubs/publications/indicators-for-change-2009-1/indicators-for-change-2009#figure25 7 Jun 2012.

Ministry of Women’s Affairs. Briefing for incoming Minister. Wellington: Ministry of Women’s Affairs, 2010. Online Available at www.mwa.govt.nz/news-and-pubs/publications/women-in-leadership 7 Jun 2012.

Morgan G, Simmons G. Health cheque. Auckland: Public Interest Publishing, 2009.

Neville S, Adams J. Men’s health and wellbeing—who is missing? Kai Tiaki Nurs N Z. 2010;16:20–21.

Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ). Guidelines for cultural safety, the Treaty of Waitangi and Māori health in nursing education. Wellington, NCNZ. Clinton, MI: Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, 2011. Online Available at www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/index.cfm/1,54,html/Guidelines 14 Aug 2011.

Padela A, et al. Meeting the healthcare needs of American Muslims: challenges and strategies for health care settings, ISPU report. Online. Available at http://ispu.org/pdfs/620_ISPU_Report_Aasim%20Padela_final.pdf, 2011. 7 Jun 2012.

Pang EC, et al. Health seeking behaviours of elderly Chinese Americans: shifts in expectations. Gerontologist. 2003;43:864–887.

Putman RD. Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Ratcliff KS. Women and health: power, technology, inequality and conflict. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2002.

Richardson F, Carryer J. Teaching cultural safety in a New Zealand nursing education programme. J Nurs Educ. 2005;44(5):201–208.

Robinson M. Equity, justice and the social determinants of health, Glob Health Promot. 2009;16(1 Suppl):48–51.. doi: 10.1177/1757975909103751.

Robinson J, McCormick DJ. Concepts in health and wellness. New York: Delmar Cengage Learning, 2011.

Sheikh A, Gatrad AR, eds. Caring for Muslim patients. Oxford: Radcliffe, 2008.

Smith GR. Health disparities: what can nursing do? Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2007;8(4):285–291.

Stanhope M, Lancaster J. Foundations of nursing in the community: community orientated practice, ed 3. St Louis: Mosby, 2010.

Starfield B. The hidden inequity in health care. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10:15.

Starfield B, et al. The concept of prevention: a good idea gone astray? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:580–583.

Trent M, et al. Gender-based differences in fertility beliefs and knowledge among adolescents from high sexually transmitted disease-prevalence communities. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:282–287.

United Nations Women (UN Women). Progress of the world’s women 2011—key points from NZ position. Wellington: UN Women National Committee Aotearoa New Zealand, 2011. Online Available at www.unwomen.org.nz/?p=541 7 Jun 2012.