Chapter 19 Developmental theories

Biophysical development theories

Cognitive development theories

Erikson’s eight stages of life

Freud’s psychoanalytical model of personality development

Havighurst’s developmental tasks

Kohlberg’s theory of moral development

Physiological theories of ageing

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Describe biophysical developmental theories under the categories of genetic theory, non-genetic cellular theories and the physiological theories of ageing.

• Describe and compare the psychosocial theories proposed by Freud, Erikson and Havighurst.

• Describe Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.

• Discuss how Kohlberg built on Piaget’s stages of moral development.

• Discuss Gilligan’s criticism of Kohlberg’s moral developmental stage theory.

• Apply developmental theories when planning interventions in the care of clients.

This chapter is concerned with explanations of the way we grow and develop throughout our life spans. When we understand the demands on our patients because of the rate and manner of their growth and development, physically, socially and psychologically, we are better placed to help them to achieve their optimal health status and support them during periods of illness. We are also able to provide developmentally and culturally appropriate care for our patients.

Developmental theories have been described that help nurses to use critical-thinking skills when asking how and why people respond as they do. From the diverse set of theories included in this chapter, the complexity of human behaviour is obvious. No one theory successfully describes human growth and development in all of its complexity. Theorists themselves demonstrate their own values and beliefs in their focus and the subjects chosen for their work. They work within a cultural and historical context. It is important to keep this in mind when applying theories. Current trends in developmental research focus more on the dynamics and processes of change and transition, and less on content or a static or still view of life at a particular stage. Keeping abreast of trends in research in psychosocial disciplines is important for nurses if they are to be at the cutting edge of health research and practice innovation.

Growth and development is not a linear process, as most theories suggest they are, but multidimensional. The theories included are meant to be the basis of a meaningful observation of an individual’s pattern of growth and development. All theories require validation through research to become fact. They are, however, valuable guidelines for understanding important human processes that can allow nurses to begin to anticipate human behaviours and responses in specific health situations.

Growth versus development

First, it is important to be aware of the difference between growth and development. Growth refers to the quantitative changes that can be measured and compared with norms, for example taking the height and weight of a paediatric client and comparing the measurements with standardised growth charts. Development implies a progressive and continuous process of change leading to a state of organised and specialised functional capacity, for example a child’s progression from rolling over to crawling to walking. Another example of development is the transition a child makes from the very concrete thinking of a young child to the ability of the adolescent to understand ideas and concepts.

Theories of growth and development

Without necessarily being aware of doing so, we frequently use theories to guide our behaviour in our daily lives. Theories are not just best guesses; they are based on information from our existing knowledge and previous experiences. For example, I have a theory that if I drive my car through a red light there can be three possible outcomes. First, I may have an accident, crashing into another car or pedestrian; second, I may be fined and lose demerit points on my licence; or third, I may be lucky and get away with it without an accident or getting caught. This is a simple theory based on what normally happens in a specific circumstance and the logical possibilities. Such a theory can be used to guide the way we behave, taking into account the likelihood of each outcome so that a favourable one is more likely. In the example above, knowing the chances of each outcome of driving through a red light may guide us to make a sensible and informed decision. Of course there are many other factors that will influence such decisions, such as if we are affected by alcohol, in a great hurry, and so on.

Theories are, therefore, series of logically connected hypotheses based on evidence about particular situations which allow us to explain and predict potential outcomes. The example of the red light is not a very complex situation compared with a theory about the kind of conditions required for a child to develop into a physically, emotionally and socially healthy adult. Complex situations require more-complicated theories with many propositions. Some of these theories are the subject of this chapter. Nurses who have a good understanding of growth and development at different ages can provide invaluable assistance to patients, children and caregivers.

When we try to understand what a person needs to develop into the best adult he or she can be and to maintain that state throughout adulthood, we have a very complex situation with multiple factors feeding into it. To understand the formation of human personality requires not just one but many theories about each aspect of its development. These aspects include personality and physical and cognitive abilities, as well as a person’s ability to make ethical decisions that affect the wellbeing of others. Understanding how people develop psychosocially, physically, cognitively and morally is tremendously important for nurses because we meet people when they are often facing some of the crisis points in their lives. The way they deal with these crises can have ramifications for the rest of their lives. Sensitive and knowledgeable support from healthcare professionals can help people negotiate these crises more effectively.

Theories of human growth and development were developed through systematic observations of people as they went about their daily lives. There are, however, several caveats that we should bear in mind when applying such theories to specific situations. First, while theories are built upon layers of evidence, they apply in many but not absolutely all circumstances. Second, it is very difficult to be certain of developmental predictions because it is often impossible to undertake systematic research to test them, partly because it is not possible to compare results with control groups. Third, it is important to keep in mind that it is not possible for any theorist to observe people from all cultures, so that the theories are necessarily culturally based and their propositions may not be universally applicable. Indeed, attempts to generalise across cultures inevitably give rise to erroneous conclusions. For example, Australia and New Zealand are multicultural societies and as nurses we will care for people from diverse backgrounds which are beyond the experience of the nurses caring for them. Having said this, we know that people are more similar than different, so developmental theories can often provide a useful guide about what to expect at various stages of life—providing they are not applied too rigidly. In this chapter we consider theories about the four major areas of human development: biophysical, psychosocial, cognitive and moral.

Biophysical development

Biophysical development is concerned with the way our bodies change physically over time. In the following sections we look at theories about how children develop as they grow and how adults change as they age.

As infants grow into adults, their physical changes can be measured. Such measurements can then be compared with those that normally occur, known as ‘established norms’. In such a way the progress of a child’s maturation can be monitored. For example, a child who reaches the age of 12 months and is still not able to sit unaided is not progressing in a ‘normal’ manner, as the majority of infants can do this by the age of 6 months. Such a child should be investigated to find out what is preventing normal development.

Gesell’s theory of development

Arnold Gesell (1880–1961) was a psychologist and doctor who initially studied intellectually handicapped children. He soon came to realise that to understand abnormal development, it is necessary to first understand the process of normal development. Gesell (1948) was one of the first to describe biophysical development based on his observations of children and, as a consequence, he developed norms for the typical age at which children reach developmental milestones. Such milestones included motor development, personal hygiene tasks, the expression of emotions, interpersonal relations, and play. These norms are still used as primary sources of information for childhood development.

Gesell’s (1948) observations led him to believe that although each child’s pattern of growth and development is unique, it remains genetically based. Environmental (including cultural) factors can support and modify the pattern, but do not generate it. Through his observations he learned that maturation has a fixed developmental sequence in all humans. For example, most children will learn how to crawl before they learn how to walk, but not every child develops those skills at exactly the same time. Gesell pointed out clearly that the environment does play a part in the development of a child, but it does not have any part in the sequence of development. Gesell believed that a child could not be pushed to develop faster than that child’s unique timetable.

Gesell’s norms have made an enormous contribution to our understanding of child development and provide a base for both parents and professionals to know what to expect of children at various ages. However, it is important to keep in mind that he developed his norms based on observations of children in New Haven, United States. These children may not be typical of other cultures, such as Arabic, Australian Aboriginal or Māri children.

There are many other theories of biophysical development, but each falls into one of three categories: the genetic theories of ageing, non-genetic cellular theories and the physiological theories of ageing (Table 19-1).

TABLE 19-1 BIOPHYSICAL THEORIES OF DEVELOPMENT

| THEORY CATEGORY | SPECIFIC THEORIES |

|---|---|

| Genetic theories—how DNA molecules transfer information that determines function and life span of cells | Programmed cell death |

| Radiation influence on DNA molecule | |

| Error theory of ageing | |

| Non-genetic cellular theories— how changes in the molecules and structural elements impair a cell’s effectiveness | Wear-and-tear theory |

| Cross-linking theory | |

| Free radical theory | |

| Physiological theories of ageing—theories related to the performance of a single organ or impairment of the physiological control mechanisms | Kilojoule intake and effect on ageing |

| Effect of stress on immune system | |

| Effect of stress alone on the body |

Genetic theories of ageing

The genetic theories of ageing try to answer such questions as ‘Why do people with long-lived parents and grandparents live longer than people whose parents die before the age of 50?’ Such differences may be explained by genetic inheritance (such as a tendency towards the production of high cholesterol) or learned behaviours (such as lifestyle) or a combination of both.

Genetic theories explain how DNA molecules transfer information via the formation of proteins, which determines the function and life span of specific cells (Cavanaugh, 1993; Eliopoulos, 1999). This programmed cell death is a function of physiological processes that cause cells to trigger processes in other cells and self-destruct. It is unknown how such processes are triggered. Considerable research is being conducted that explores this theory of ageing (Eliopoulos, 1999).

One DNA theory looks at how exposure to radiation shortens the life span. Laboratory studies have shown that animals have a shortened life span when exposed to non-lethal doses of radiation. It is felt that this can occur in humans, which is supported by the fact that ultraviolet light causes wrinkling of the skin and promotes skin cancer.

The error theory of cellular ageing looks at how errors in the genetic code can occur during the process of transporting DNA information in the production of the protein and enzyme molecules required by the cell (Cavanaugh, 1993; Eliopoulos, 1999). When these errors occur, the altered protein or enzyme synthesis leads to defective cellular structure and function.

Non-genetic cellular theories

Non-genetic cellular theories look at the cellular level (as opposed to that of DNA) and how changes that take place in the molecules and structural elements of cells impair their effectiveness (Cavanaugh, 1993; Eliopoulos, 1999). The wear-and-tear theory works on the premise that our bodies just ‘wear out’. This theory can explain some specific processes of ageing (such as osteoarthritis) that contribute to ageing, but it does not explain general ageing.

Cross-linking theory finds that certain proteins within human cells interact with molecules to form cross-links that alter the physical and chemical properties of the molecules involved. These molecules then no longer function in the same way as they did before. Cross-links accumulate over time. These processes occur in arteries, muscles and skin tissues and account for age-related changes in the body.

The free-radical theory proposes that ageing is due to unstable molecules that are highly reactive chemicals causing cellular damage and thereby impairing the functioning of the organ. The rate of the formation of these free-radicals is accelerated by radiation but inhibited by the presence of antioxidants, lathyrogens, prednisolone and penicillamine. This theory has spurred research in the inhibitory properties of the antioxidants (especially vitamins A, C and E) and how these vitamins counteract the effects of free-radicals, thereby extending life. Research so far has shown insufficient evidence about the usefulness of antioxidants in the treatment of certain conditions such as dementia (Birks and Grimley 2009; Isaac and others, 2008) and motor neuron disease (Orrell and others, 2007).

Physiological theories of ageing

Physiological theories of ageing look at either the breakdown in the performance of a single organ or the impairment of the physiological control mechanisms (Cavanaugh, 1993; Eliopoulos, 1999). Under this category various theories relate to single organs or metabolic processes being tested, such as how many kilojoules one consumes. Reducing kilojoules appears to lower the risk of premature death and slow down the normative age-related changes (Edwards and others, 2010), which is supported by the facts we currently know about the problems caused by obesity, high cholesterol levels and vitamin deficiencies.

The effect of stress, alone or in combination, on the immune system is the basis of two theories of ageing. Some theorists suggest that alterations in the effectiveness of the immune system are responsible for ageing. The body may lose its ability to distinguish its own proteins from foreign ones, and will attack and destroy its own tissues. The second immunological theory proposes that as the body ages it is less able to fight off infection, which is felt to be a factor in the development of chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease (see Chapter 42).

FIGURE 19-1 A retired couple enjoying fishing together.

From Sorrentino S 1999 Assisting with patient care. St Louis, Mosby.

The biophysical theories all attempt to describe the processes of why our bodies mature and age. No one theory explains every aspect of ageing, but each one can add to our understanding. Gesell went as far as to propose that it is our biological body that determines our behavioural development. The psychosocial theories look at the process of development from a very different perspective, and as such add even further to our understanding of ageing processes.

Psychosocial theory

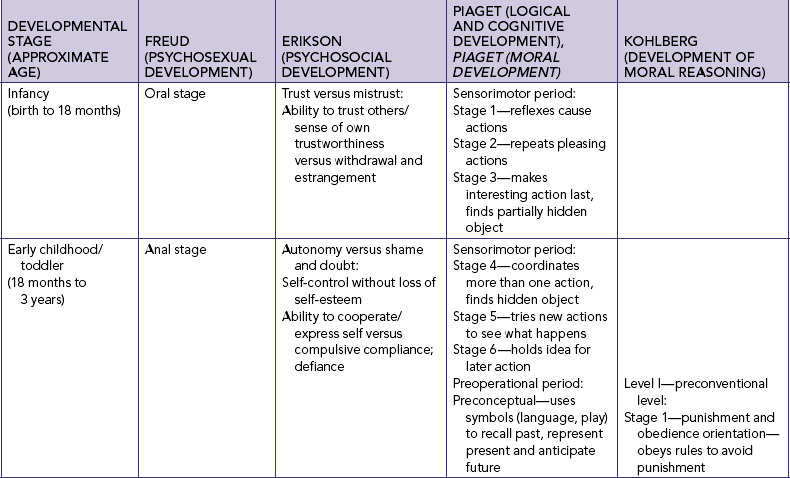

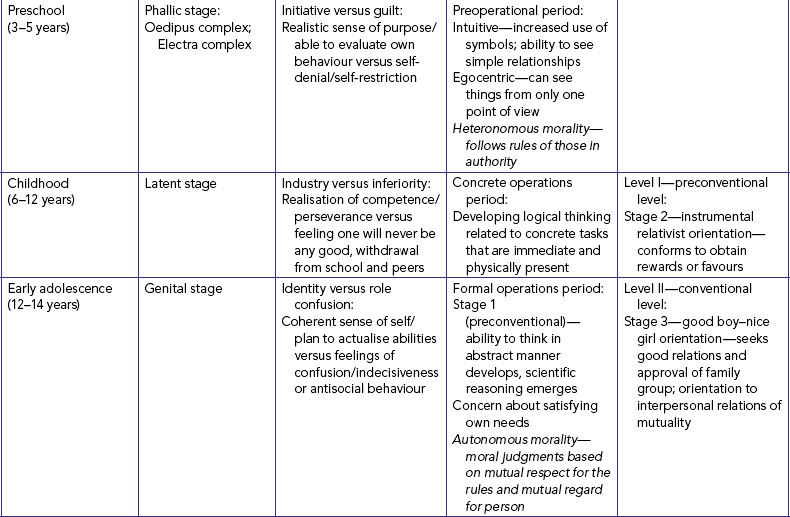

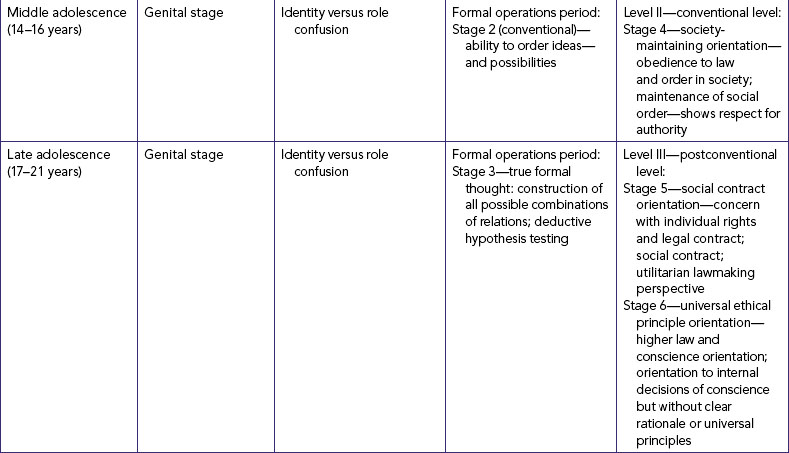

A number of psychologists conducted systematic and careful observations of children and adults and from these they put together various psychosocial theories about the development of human behaviour. Many theorists have devoted their entire lifetime to the development of a consistent understanding of how we become successful human beings. Human behaviour is extremely complex and therefore difficult to capture within one theory, so different theorists have tended to focus on different aspects such as psychosexual, psychological, cognitive and moral development (Table 19-2). Each of these theorists believed that as we grow we progress through a series of sequential stages. As each stage is negotiated, the child’s personality increases in maturity.

Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytical model of psychosexual development

The first person to provide a structured and complex theory of personality development was Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). Freud was a psychologist who practised in Europe. He developed his theory based on systematic observation of his patients and it is still very influential today. Terms such as ‘denial’ and ‘repression’ were introduced by Freud. His work provided the basis for the development of the discipline of psychology.

Freud’s theory is grounded in the belief that two internal biological forces (aggressive and sexual forces) essentially drive psychological change in the child. He defined ‘sexual’ somewhat broadly as anything that produces bodily pleasure (Freud, 1962). Sources of such pleasure develop at different ages—infants, for example, find pleasure mainly in the oral area from sucking. Freud described five stages, each of which he believed to be associated with the development of a sensual pleasurable zone.

Through these stages the components of personality develop. Freud believed that the functions of these components govern adult life. These components are the id, the ego and the superego. The id is the pleasure-seeking aspect of personality and is predominant in infancy. Infants are dominated by the desire to seek pleasure without the constraints of what is realistic or right. The ego represents the reality components mediating conflicts with the world when the person is driven by the id. The ego develops during childhood and helps us to judge reality accurately, to regulate impulses and to make good decisions. The third component, superego, performs inhibiting, restraining and prohibiting actions. Often referred to as the conscience, the superego is initially derived from the standards of outside social forces (parent, teacher). It starts to develop in childhood and continues during adolescence. An adolescent, for example, may be motivated to seek pleasure (id) from spending vast amounts of time in leisure activities. His sense of reality (ego) may constrain him because he recognises that other activities such as learning and homework also need to be done. His developing conscience (superego) may also restrain him because he wishes to contribute to the good of society by, for example, being a volunteer for ‘Clean up Australia Day’ or ‘Keep New Zealand Beautiful’.

Freud believed that the major motivation for behaviour is to achieve pleasure and avoid pain created by these aggressive and sexual forces. Maturational changes occur as these forces come into conflict with the reality of the world.

Freud’s five psychosexual developmental stages

STAGE 1: ORAL (BIRTH TO 12–18 MONTHS)

Initially sucking, oral satisfaction is not only vital to life, but also extremely pleasurable in its own right. The id—basic instinctual impulses to achieve pleasure—is the most primitive part of the personality and originates with the infant and forms the infant’s drive to seek oral pleasure.

Late in this stage, the infant begins to realise that the mother/parent is something separate from self. Disruption in the physical or emotional availability of the parent (e.g. mental disability, chronic illness, substance abuse) could have an impact on the infant’s development.

STAGE 2: ANAL (12–18 MONTHS TO 3 YEARS)

The focus of pleasure changes to the anal zone. Children become increasingly aware of the pleasurable sensations of this body region with interest in the products of their effort. This is the stage when the child is first asked to withhold pleasure to meet parental/societal expectations through the toilet-training process. The ego starts to develop during this stage when the child begins to realise that reality (such as parental expectations) must moderate pleasure-seeking.

STAGE 3: PHALLIC OR OEDIPAL (3–6 YEARS)

It is during this stage that the sexual organ gains prominence. According to Freud, the boy becomes more interested in the penis; the girl becomes aware of the absence of the penis. These are times of exploration and imagination as the child fantasises about the parent as the first love interest. Freud believed that sexual wishes are temporarily driven underground through the action of the developing superego, or conscience, during this stage.

STAGE 4: LATENCY (6–12 YEARS)

This is the stage in which Freud believed that the aggressive and sexual urges are submerged in the unconscious at the end of the oedipal stage, and channelled into productive activities that are socially acceptable. Latency was thought to be a time of minimal sexual interest or activity. Within the educational and social worlds of the child, there is much to learn and accomplish. This is where the child places energy and effort.

STAGE 5: GENITAL (PUBERTY TO ADULTHOOD)

This is Freud’s final stage; he did not formally continue his theory into adulthood. This is a time of turbulence when sexual urges re-emerge to be dealt with. Freud believed that the task of moving from the sexual attachment to the parent to the separation and emotional independence of the adult is difficult to achieve.

The goal of development as seen by Freud was the development of balance between the pleasures of the world and the domination of guilt and shame that comes from indulgence of these pleasures. The fully developed adult would have a strong sense of conscience that allowed the experience of pleasure within a clear appraisal of reality. Although Freud’s theory has been soundly criticised for gender and cultural biases, he gave other theorists a basis for their observations of psychosocial development.

Erik Erikson

Erikson (1902–1994) refined Freud’s theory and expanded it to include three stages of adult development which completed his theory of development across the life span. Erikson was born in Germany of a Jewish mother. When the Nazis came to power, he left for the United States where he spent most of his productive life. He was largely influenced by Freud but placed more emphasis on the social–cultural aspect of personality development rather than the psychosexual.

Erikson described eight stages of life, the first five coinciding with Freud’s stages (see Table 19-2). He believed that development is an evolutionary process based on sequencing biological, psychological and social events, and that social and cultural expectations compel the individual to establish equilibrium related to a specific developmental task at each developmental stage (Erikson, 1963, 1987). Each task is framed as opposing tendencies, such as the adolescent’s need to develop a sense of personal identity at a time when there are many confusing choices. A sense of identity is important for the adolescent to progress to adulthood and form satisfactory intimate relationships with others. Adolescents who are unable to develop a sense of identity tend to remain confused about who they are and how to relate to others. In such a way, each stage builds on the successful resolution of the previous developmental task and predisposes the person to be ready for the next task. Readiness for the task is necessary for success.

It is not necessary that the conflict is resolved entirely in the positive, but rather that on balance the outcome is positive. For example, for the toddler the positive aspect is the development of autonomy but this sense of autonomy must develop within the context of the toddler’s physical limitations. This exemplifies Erikson’s concept of balance.

Erikson’s eight stages of life

TRUST VERSUS MISTRUST (BIRTH TO 1 YEAR)

Starting with oral satisfaction, the infant learns to trust the caregiver. The caregiver is representative of the greater world. Trust is achieved when the infant will let the caregiver out of sight without undue distress. The infant has learned to trust not only others but also self. When infants’ needs are met consistently, they come to regard the world as generally a safe place. Neglect during infancy leads to the child becoming filled with mistrust—a negative feature. However, even the most cared-for infants experience occasional neglect when needs go unmet. The balanced outcome of this stage is that the person achieves a general trust with the ability to understand that all people are not equally trustworthy. In adult life, the person must have some scepticism to avoid being cheated by unsavoury people. Nurses can assist parents in helping their infants to successfully resolve this stage. For example, a parent may need guidance to understand the importance of a safe environment when meeting the child’s need to explore crawling before walking.

AUTONOMY VERSUS SHAME AND DOUBT (1–3 YEARS)

Having developed a sense of trust in the adults in their lives, the growing child is now ready to develop a sense of their own abilities. They now realise, in part through bowel and bladder control experiences, that there is a choice of holding on or letting go and therefore begin to understand that they have a degree of control over their environment. In this way a sense of autonomy starts to develop. Understandably, toddlers may try to exert such control inappropriately over relationships, personal desires and manipulative objects such as toys. At this age children are sometimes willing to share toys, and cooperate some of the time but not all of the time and with some people but not others. Children, however, also learn that parents and society have expectations about these choices. The manner in which autonomy is regulated, with empathetic guidance and support from caregivers, has an impact on the achievement of successful control without loss of self-esteem. Harsh discipline can lead the child to doubt their abilities and feel a sense of shame. Extremely permissive approaches leave the child unable to test the limits of their abilities with the safety of a watchful adult.

Of course Erikson’s ideal of balance is important here, as the child needs to realistically assess their abilities and accept that there are limits to the degree of autonomy that a toddler can realistically achieve. Nurses can help caregivers understand the challenges of this developmental stage. They can model empathetic guidance that indicates support for and understanding of the tasks the child faces at this stage which will help the child develop a balanced sense of autonomy.

INITIATIVE VERSUS GUILT (3–6 YEARS)

This is a time of expanding physical and intellectual abilities (Figure 19-2). Having developed a realistic sense of their basic capabilities, the preschool-aged child can now build on these to make plans, set goals and reach achievements. In so doing, they begin to acquire a sense of initiative and so learn new ways of using their recently acquired skills. This sense of initiative can be observed in the games children play.

FIGURE 19-2 Play is therapeutic at any age and provides a means for release of tension and stress in the environment.

Image: Shutterstock/ZINQ Stock.

While playing, the child may come into conflict with another child which requires a response from an adult. This is the stage when the beginnings of a conscience (or superego) begin to emerge. If adults’ responses are too punitive, the child may be left with a feeling of guilt and initiative may be thwarted. Teaching cooperative behaviours to children can enhance their ability to meet developmental tasks. Informing parents of the changes that the preschooler is facing can help the family support the child’s development (Box 19-1). It is also important to help parents understand that it is still necessary to place limits on children’s initiative so that they can understand what is required of them by society.

INDUSTRY VERSUS INFERIORITY (6–11 YEARS)

Erikson believed that the adult’s attitudes towards work could be traced to successful achievement of this task (Erikson, 1963). School-aged children are eager to apply themselves to learning socially productive skills and tools. They learn to work and play with their peers. Lack of achievement occurs in part because children lack adult capacities; this may create a sense of inadequacy and inferiority for children as they judge their performance against unrealistic standards. Children need to be helped to understand what is reasonable for them to achieve. Take the example of a learning-disabled child struggling to learn to read. Because of a biological difference and the delayed achievement, this child may have difficulty avoiding a sense of inferiority. At this age, children need to be supported to understand where their talents lie and to achieve in those areas.

IDENTITY VERSUS ROLE CONFUSION (PUBERTY)

Dramatic physiological changes associated with sexual and aggressive drives mark this stage. There are also new social demands, opportunities and conflicts that relate to the emergent identity and separation from family. This is the milieu in which identity development begins. Alternatives are tried with the goal of achieving some perspective or direction to answer ‘Who am I?’ and ‘What kind of adult will I become?’ Acquiring a sense of identity is essential for making adult decisions such as choice of vocation or marriage partner. Each adolescent moves in their unique way into society as an interdependent member (Figure 19-3), and peers play a major role in the lives of adolescents (see Research highlight). To continue the example of adolescence, a person who is ready to develop an intimate relationship will be reasonably comfortable with the sort of person he/she is but is sufficiently malleable to be able to merge their identity with another and become a functioning couple.

FIGURE 19-3 Adolescents use being alone as a method of coping with stress. Healthcare professionals need to assess whether this method also indicates an attempt to cope with depression.

Image: Dreamstime/Dmiskv.

Nurses can provide education and anticipatory guidance for the parent about the changes and challenges to the adolescent. Nurses who understand the developing adolescent also recognise that adolescents need to be recruited as partners in their care. They are entitled to be consulted, along with their parents, about their progress and treatment.

You are setting up an adolescent in-hospital unit. Knowing that identity development and self-esteem are critical developmental tasks for adolescents and that most are capable of abstract thinking, how would you ensure that the facilities and features of the built environment are adolescent-focused?

INTIMACY VERSUS ISOLATION (YOUNG ADULT)

Young adults, having developed a sense of identity, deepen their capacity to love others and care for them (Table 19-3). Successful intimate relations require the partners to develop a joint identity. Joint identity is difficult to achieve when the partners do not have a strong sense of who they are. If young persons have not achieved a sense of personal identity, they may experience feelings of isolation from others and the inability to form attachments. Their willingness to share, and mutually regulate their lives with another, marks the completion of this task.

TABLE 19-3 ADULT DEVELOPMENTAL THEORISTS

Young adulthood is the time to become fully participative in the community, enjoying adult freedom and the responsibility that goes with that freedom. Understanding the development needs of young adults will guide nurses in supporting patients in their obligations, which may relate to their education, occupation, partners or offspring.

GENERATIVITY VERSUS STAGNATION (MIDDLE AGE)

Following the successful development of an intimate relationship, the adult can focus on raising the next generation. The ability to sacrifice one’s own needs to care for others is possible with or without the production of offspring. The emphasis on independent achievement so prevalent in Western cultures can create a situation in which adults become too absorbed in their own success and neglect the needs of others. Adults at this stage are frequently at the peak of their careers (with its attendant demands), are often responsible for adolescent children and may also be responsible for ageing parents. Such responsibilities may be a source of stress, but also a source of great satisfaction. Illness that inhibits the discharge of these responsibilities may be a cause of considerable distress.

Research focus

The health of young people is increasingly being researched in Australia and the evidence found contributes methods of helping young people to successfully negotiate adolescence. One method that has become the focus of researchers is the development of helping skills in adolescent peers. These helping skills focus on supporting young people as they cope with their experiences of adolescence.

Abstract

Peer support is used frequently in addressing the health of young people. The Helping Friends program builds on existing peer helping networks in schools to improve the availability, accessibility and appropriateness of social and personal support. It increases young people’s knowledge of and access to referral options (in and out of school) and assists in the development of a safe and supportive school environment. Twenty-two schools in North Queensland, Australia participated in the program with many participating on several occasions. An evaluation of the Helping Friends program using the Social Provision Scale was undertaken to determine whether there was an increase in perceived social support as hypothesised. Results revealed small yet significant increases along subscales of the Social Provision Scale. Pre- and post-measures of helping skills and knowledge of helping topics also revealed a significant increase following students’ participation in training workshops. The results are discussed in terms of the efficacy of peer support programs for addressing the health needs of young people. The findings can be used to guide secondary schools in making decisions on the value of peer support programs and their application in school and out-of-school settings.

Evidence-based practice

• The Helping Friends program has been effective in increasing knowledge of helping behaviour.

• Peer influence is an important consideration in designing programs that target adolescent health.

• Identifying respected friends and enhancing existing skills can reinforce the level of social support within and across peer groups.

Dillon J, Swinbourne A. Helping Friends: a peer support program for senior secondary schools. Aust e-J Adv Ment Health. 6(1), 2007. Online. Available at http://amh.e-contentmanagement.com/archives/vol/6/issue/1/article/3309/helpingfriends 2 Jul 2012.

A 45-year-old male executive of a local corporation enters the emergency department with intense chest pain. Upon evaluation, it is determined that he has severe cardiovascular disease and requires open-heart surgery. His children, aged 13 and 17, and wife accompany him to the hospital. They have a very expensive lifestyle, and he is the sole earner for the family. His son is planning to enrol in an economics degree at university next year. After the client settles in his room, he asks for computer access to complete some work before surgery. How will the nurse help this client to change his lifestyle while understanding his developmental tasks?

INTEGRITY VERSUS DESPAIR (OLD AGE)

As the ageing process creates physical and social losses, the adult may also suffer loss of status and function, such as through retirement or illness. These external struggles are also met with internal struggles, such as the search for meaning in the life they have lived. Meeting these challenges creates the potential for growth and wisdom. Many older people review their lives with a sense of satisfaction, even with the inevitable mistakes. Others see themselves as failures, with marked contempt and disgust and the inevitable despair that comes from the realisation that it is now too late to achieve hoped-for goals.

Nurses are in positions of influence within their communities and can contribute to the valuing of people at all ages and stages. Erikson (1963) stated, ‘Healthy children will not fear life, if their parents have integrity enough not to fear death.’ Erikson did significant research during his academic career with varied cultural traditions and gender groups. He believed his theory to be widely applicable.

Robert Havighurst

Basing his ideas on Erikson’s work and his observation of mainly middle-class Americans, Robert Havighurst (1900–1991) was an educator who identified a series of essential tasks that need to be achieved throughout the life span (see Table 19-3) (Ashburn, 1978). We can see from our own experiences and from observing those of others that we tend to achieve certain goals at specific times of our lives. We learn to walk and talk as babies, to read and write as children, to form sexual partnerships during adolescence and adulthood, and so on. When we accomplish these tasks we develop a sense of mastery and satisfaction and this sets us up to achieve subsequent developmental tasks. Both Havighurst and Erikson provided explanations and structure for our observations.

Havighurst believed that the pressures to achieve these tasks, as well as social pressures, develop from our increasing physical maturity and our personal goals and aspirations. Developmental tasks require the individual to reconcile increasing physical maturity with skills such as walking, talking or eating. Cultural pressure creates the conditions necessary to learn social behaviours and ethical norms. For example, although an adolescent girl may be physically able to accomplish the task of having a child, the preparation and timing for the onset of parenthood can also be considered from a perspective of cultural pressure from both the youth and the adult cultures. The desire to have a child might also grow out of the individual’s personal aspiration to be a parent.

Havighurst believed that there are critical periods when the individual is most receptive to the learning necessary to achieve success in performing these tasks. In a similar way to Erikson, Havighurst believed that effective learning and achievement of tasks during one period leads to success with later tasks. Success leads to happiness and acceptance by society. Failure leads to unhappiness, disapproval by society and difficulty with later tasks. An example might be the struggle that adolescents might experience in preparing for a work career after having failed to develop fundamental skills in reading.

As an educator, Havighurst believed that schools have considerable responsibility for helping a child attain the success necessary to lead to achievement of later adult development. His theory is a structure of both non-recurrent tasks specific to a stage of development, such as learning to walk, and recurrent tasks that re-emerge in new ways, such as learning to get along with age-mates.

His critics, however, believe that Havighurst’s theory is limited in its cultural application because it describes developmental milestones from the perspective of middle-class norms within the American culture. It would be difficult to fit all cultural or ethnic mores within this theoretical framework.

A 76-year-old woman has just been diagnosed with breast cancer. She also has severe cardiovascular disease that limits her choices of treatment. Her oncologist has recommended a series of chemotherapy that her cardiologist believes would be fatal. Her family is urging her to do all that is recommended. The client, who is in good spirits despite her diagnosis, chooses palliative care. Based on her developmental stage, how can you help the family adjust to her choice?