Chapter 42 Stress and adaptation

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Discuss the limitations of homeostatic control.

• Compare four models of stress as they relate to nursing practice.

• Describe how adaptation occurs in each of the six dimensions of a person’s functioning.

• Describe two forms of physiological adaptation.

• Describe the three phases of the general adaptation syndrome.

• List and discuss behaviours that are responses to stress.

• List and discuss the most common ego-defence mechanisms that are responses to stress.

• Discuss the effects of prolonged stress on each of the six dimensions of a person’s functioning.

• Describe stress management techniques that nurses can use and help clients to use.

Every person experiences some stress throughout life. Stress can provide the stimulus for change and growth. Some stress is positive and even necessary (Folkman, 2008). However, too much stress can result in poor judgment, physical illness and inability to cope (Schulz and Sherwood, 2008). Several studies have proposed a relationship between stressful life events and a wide variety of physical and psychiatric disorders (Mason and Beavan-Pearson, 2005; Papadiamantopoulou and others, 2010).

Claude Bernard, in 1867, was one of the first physiologists to recognise the consequences of stress. He proposed that changes in the internal and external environments disrupted the functioning of an organism and that it was essential for an organism to adapt to a stressor to survive. In 1920, Walter Cannon studied physiological responses to emotional arousal and emphasised the adaptive functions of the ‘fight-or-flight’ reaction. Cannon also noted that these responses were the result of the influence of the emotional state on the body and that the subsequent responses were adaptive and physiological (Cannon, 1932).

Hans Selye (1946) developed a biochemical model of stress known as the general adaptation syndrome (GAS), which described physiological events during a stress response. Selye also introduced the concept of stressors, which are internal or external stimuli that cause stress (Selye, 1976). Selye’s classic research into stress and stressors has been important for healthcare professionals. Current research in many disciplines focuses on a variety of stress and stress-related concepts.

Subsequent researchers have focused not only on identifying and understanding stress and stressors, but also on how individuals cope with and adapt to stress. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) described stress as a transaction between the individual and the environment, in which the individual makes a cognitive assessment as to whether an event is stressful or not, and whether or not they have the resources to manage or cope with the stressor. Unlike earlier stress research which focused on the negative emotions and outcomes, Folkman (2008) emphasises the co-occurrence of positive and negative emotions and experiences during stressful times.

Scientific knowledge base

Stress and stressors

Everyone experiences stress from time to time and normally a person is able to adapt to long-term stress or cope with short-term stress until it passes. Nevertheless, stress can place heavy demands on a person and if the person is unable to adapt, illness can result.

Stress is any situation in which a non-specific demand requires an individual to respond or take action (Selye, 1976). It involves physiological and psychological responses. Stress can lead to negative thoughts, feelings and behaviours and may threaten emotional and physical wellbeing. It can threaten the way a person normally perceives reality, solves problems and thinks in general; it can threaten a person’s relationships and sense of belonging and lead to coping or maladaptive behaviour. Stress can also threaten a person’s general outlook on life and health status.

A person’s perception or experience of a major change may initiate the stress response. The stimuli preceding or precipitating the change are called stressors. Stressors represent an unmet need and may be physiological, psychological, social, environmental, developmental, spiritual or cultural. Stressors can be classified as internal or external. Internal stressors originate inside a person (e.g. having a fever, living with a chronic illness, experiencing an emotion such as guilt). External stressors originate outside a person (e.g. a marked change in environmental temperature, a change in family or social role, peer pressure, loss).

Physiological adaptation

Physiological adaptation to stress is the body’s ability to maintain a state of relative balance. This adaptive ability is a dynamic form of equilibrium in the body’s internal environment. The internal environment constantly changes, and the body’s adaptive mechanisms continually function to adjust to these changes and thus to maintain equilibrium, or homeostasis.

Homeostasis is maintained by physiological mechanisms that control body functions and monitor body organs. For the most part, these mechanisms are controlled by the nervous and endocrine systems and do not involve conscious behaviour. The body makes adjustments in heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, fluid and electrolyte balances, hormone secretions and level of consciousness—all directed at maintaining adaptation.

Mechanisms of physiological adaptation

When a person becomes aware of an unmet physiological need, such as food or warmth, deliberate actions can meet the need. For the most part, however, adaptation involves adjustments that the body makes automatically to maintain equilibrium. These homeostatic mechanisms are self-regulatory; in other words, they are automatic. In a person with an illness or injury, however, the mechanisms may not be able to maintain and sustain homeostasis.

Physiological mechanisms of adaptation function through negative feedback, a process by which the controlling mechanism senses an abnormal state, such as lowered body temperature, and makes an adaptive response, such as initiating shivering to generate body heat. Three of the major mechanisms used in adapting to a stressor are controlled by the medulla oblongata, the reticular formation and the pituitary gland.

MEDULLA OBLONGATA

The medulla oblongata controls vital functions necessary for survival, including heart rate, blood pressure and respiration. Impulses travelling to and from the medulla oblongata can increase or decrease these vital functions. For example, regulation of the heartbeat is the result of sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous system impulses travelling from the medulla oblongata to the heart. The heart rate increases in response to impulses from sympathetic fibres and decreases with impulses from parasympathetic fibres.

RETICULAR FORMATION

The reticular formation is a small cluster of neurons in the brain stem and spinal cord. It also controls vital functions and continuously monitors the physiological status of the body through connections with sensory and motor tracts. For example, certain cells within the reticular formation can cause a sleeping person to regain consciousness or increase the level of consciousness when a need arises.

PITUITARY GLAND

The pituitary gland, a small gland attached to the hypothalamus, supplies hormones that control vital functions. It produces hormones necessary for adaptation to stress, and regulates the secretion of thyroid, gonadal and parathyroid hormones. Hormone secretion, like other homeostatic mechanisms, is normally regulated by a feedback mechanism that continuously monitors hormone levels in the blood. When hormone levels drop, the pituitary gland receives a message to increase hormone secretion. When hormone levels rise, the pituitary gland decreases hormone production.

Limitations of physiological mechanisms of adaptation

Physiological mechanisms of adaptation work together through complex relationships in the nervous and endocrine systems and other body systems to maintain a relative constancy within the body. In a healthy person, these mechanisms affect physiological balance and the body’s day-to-day needs are met. However, physiological mechanisms of adaptation can provide only short-term control over the body’s equilibrium. They cannot adapt to long-term changes in hormone secretion or vital functions. Thus illness, injury or prolonged stress can decrease the adaptive capacity. Decreased functioning can result in continued but inadequate homeostatic control or breakdown of the feedback mechanism that allows control. Either form of decreased function can result in further illness or death.

In severe stress situations, for example, the pituitary gland supplies the body with the necessary hormones. However, these hormones may be insufficient in quantity to provide the physiological requirements necessary for coping. In such a case the person’s condition deteriorates and functioning declines.

Models of stress

The origins and effects of stress can be examined in terms of biomedical and cognitive–behavioural theoretical models. Stress models are used to identify the stressors for a particular individual and predict that person’s responses to them. Each model emphasises a different aspect of stress. Understanding stress models enables nurses to assist a client to cope with excessive stressors and to recognise and manage unhealthy, non-productive responses to stressors. Thereby these models facilitate the delivery of individualised nursing care.

Response-based model

The response-based model is concerned with specifying the particular response or pattern of responses to a stressor. Walter Cannon was a physiologist and an early stress researcher who first described the fight-or-flight response (a primitive inborn protective mechanism to defend the organism against harm). This is a physical reaction by an organism (including humans) to a perceived threat (Cannon, 1932). Cannon observed that the organism’s endocrine and sympathetic nervous systems were aroused when threatened, preparing the organism to respond to the anticipated danger by either reacting with aggression (fight) or by escaping (flight).

The fight-or-flight response is adaptive when arousal enables the individual to take immediate action—to either address or escape the threat. However, prolonged, unrelenting arousal, for which adaptation does not occur, is potentially harmful and can lead to long-term health consequences. For example, for the client who lives in a domestic violence situation, neither fight nor flight is an adaptive response because a longer-term solution is required.

Selye’s (1976) model of stress defines stress as a non-specific response of the body to any demand made on it. Stress is demonstrated by a specific physiological reaction, the GAS, which is a physiological response of the whole body to stress. It involves the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system. Thus the response of a person to stress is considered purely physiological and not influenced by cognitive processes.

A limitation of the response-based model is that it does not consider individual differences in response patterns. For instance, one individual may see the same stressor, such as starting a new job, as a welcome challenge while another may perceive it as a threat (Barkway, 2009).

Adaptation model

The adaptation model is based on the understanding that people experience anxiety and increased stress when they are unprepared to cope with stressful situations. Using this model can help nurses plan appropriate interventions.

The adaptation model proposes that four factors determine whether a situation is stressful (McAlpine and Mechanic, 2010; Mechanic, 1962). The ability to cope with stress, the first factor, usually depends on the person’s experience with similar stressors, support systems and overall perception of the stressor.

The second factor deals with the practices and norms of the person’s peer group. If the peer group considers it normal to talk about a particular stressor, the client may respond by complaining about it or discussing it. This response may help adaptation to the stress, or the client may respond in this way simply to conform to peer group behaviour.

The third factor is the impact of the social environment in helping a person to adapt to a stressor. For example, a homeless woman with schizophrenia may seek assistance for an acute pelvic infection. The woman may be assessed and intravenous antibiotic therapy instituted. The healthcare professionals involved and the hospital are resources for the client to reduce the severity of a stressor.

The last factor involves the resources that can be used to deal with the stressor. In the example just given, the client needs transport to the hospital and financial arrangements that will provide for her care. Both these factors will influence how she can access the resources to help her cope with the physiological stressor.

Stimulus-based model

The stimulus-based model focuses on disturbing or disruptive events within the environment. The seminal research of Holmes and Rahe (1967) that identified stress as a stimulus has resulted in the development of the Social Readjustment Rating Scale, which measures the effects of major life events on illness. Alternatively, the stimulus may be an accumulation of minor life events or hassles, as described by Kanner and colleagues (1981) in a study which compared the stress from daily hassles and uplifts with the stress produced by major life events. In another study, Ryan (2009) surveyed the academic stressors and coping strategies used by a cohort of 161 college students and found that minor hassles emerged as the most prominent stressor. However, as with the response-based model, the stimulus-based model does not allow for individual differences in perception and response to stressors.

Transaction-based model

The transaction-based (process) model was first proposed by Lazarus and Folkman (1984). The model views the person and environment as being in a dynamic, reciprocal, interactive relationship. The person’s reaction to a stressor is viewed as an individual perceptual response (cognitive appraisal) rooted in psychological and cognitive processes. Distress is experienced when the person perceives an imbalance between demands and resources. The individual’s appraisal is influenced by personal factors such as beliefs, perception of control, and uncertainty.

This model focuses on stress-related processes such as cognitive appraisal and coping (Folkman, 2008). Stress originates from the relationship between the person and the environment. Distress is experienced when the person perceives that the stressor exceeds the resources available to respond to the stressor. Alternatively, coping occurs when the person perceives that their resources are sufficient to deal with the stressor.

Factors influencing response to stressors

The response to any stressor depends on physiological functioning, personality and behavioural characteristics, as well as the nature of the stressor (Box 42-1). Each factor influences the response to a stressor. A person may perceive the intensity or magnitude of a stressor as minimal, moderate or severe—the greater the magnitude of the stressor, the greater the stress response. Similarly, the scope of a stressor can be described as limited, medium or extensive—the greater the scope of a stressor, the greater the response of the client to it (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984).

Adaptation to stressors

Adaptation is the process by which the physiological or psychosocial dimensions change in response to stress. There are many forms of adaptation. Physiological adaptations make physiological homeostasis possible. A similar process of adaptation, however, may occur in the psychosocial and other dimensions. For example, health promotion often focuses on a person’s, family’s or community’s adaptation to stress.

Adaptation is an attempt to maintain optimal functioning. Adaptation involves reflexes, automatic body mechanisms for protection and coping mechanisms, and ideally can lead to adjustment or mastery of a situation (Selye, 1976). A stressor that stimulates adaptation may be short-term, such as a fever, or long-term, such as paralysis of a limb. To function optimally, a person must be able to respond to such stressors and adapt to the required demands or changes. Adaptation requires an active response from the whole person.

Like an individual, a family or group may need to adapt to a stressor. Family adaptation is the process by which a family maintains a balance so that it can fulfil its purposes and tasks, deal with stress and promote the growth of individual members. In a study which investigated the functioning of families in which one partner was employed in the fly-in fly-out workforce (where workers are flown in to an employment site, which is often remote, for a number of days of work before returning to their family for a rest period), effective communication skills, cohesive relationships, an ability to be flexible with change and access to community resources were found to be predictive of family coping (Taylor and Simmonds, 2009).

• CRITICAL THINKING

Sarah Jenkins, who is 10 weeks pregnant, presented with vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain to the accident and emergency department of the hospital where you work. She was accompanied by her partner Neil. Their baby was conceived after they had undergone in-vitro fertilisation treatment for 3 years. Identify potential stressors for the couple.

DIMENSIONS OF ADAPTATION

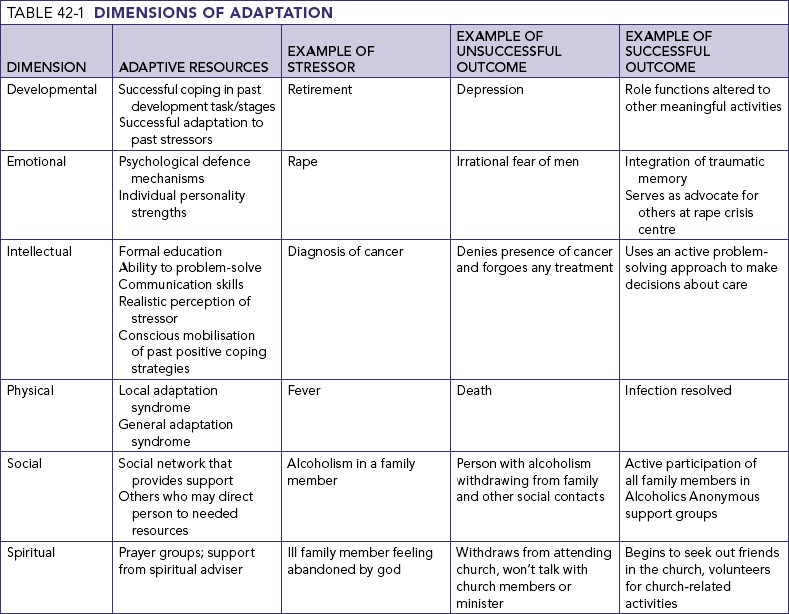

Stress can affect the physical, psychological/emotional, developmental, intellectual, social and spiritual dimensions. Adaptive resources exist in each of these dimensions. Therefore, when assessing a client’s adaptation to stress, a nurse must consider the total person. Table 42-1 highlights adaptive resources found in each dimension and gives examples of positive and negative outcomes of stressors.

Response to stress

The total person is involved in responding and adapting to stress. Most research into stress responses, however, focuses on psychological or emotional and physiological responses, although these dimensions overlap and interact with the other dimensions.

When stress occurs, a person uses physiological and psychological energy to respond and adapt. The amount of energy required and the effectiveness of the attempt to adapt depend on the intensity, scope and duration of the stressor and the number of other stressors occurring at the time. The stress response is adaptive and protective, and the characteristics of this response are the result of integrated neuroendocrine responses (Box 42-2).

BOX 42-2 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STRESS RESPONSE

• Stress response is natural, protective and adaptive.

• There are normal responses to stressors; stressors encountered in everyday circumstances increase catecholamine excretion, which causes an increase in heart rate and blood pressure.

• Physical and emotional stressors trigger similar responses (specificity versus non-specificity). Magnitude and patterns may differ.

• There are limits in ability to compensate.

• Magnitude and duration of stressors may be so great that homeostatic mechanisms for adjustment fail, leading to death.

• Repeated exposure to stimuli results in adaptive changes; that is, tissue levels of the enzyme tyrosine hydrolase increase, which increases capacity for the body to produce adrenaline and noradrenaline.

• There are individual differences in response to same stressors.

Modified from Carrieri-Kohlman V, Lindsey AM, West CM 2003 Pathophysiological phenomena in nursing: human response to illness, ed 3. St Louis, Saunders.

Nursing knowledge base

Nurses are constantly challenged by a variety of stress responses when providing care to clients, and interventions are often required when treating symptoms arising from stress. Interventions must consider physiological underpinnings, psychological issues, developmental and intellectual factors and the person’s social and spiritual world.

Physiological response

The classic research by Selye (1946, 1976) identified the two physiological responses to stress: the local adaptation syndrome (LAS) and the general adaptation syndrome (GAS). The LAS is the response of a body tissue, organ or part to the stress of trauma, illness or other physiological change. The GAS is a defence response of the whole body to stress.

Local adaptation syndrome

The body produces many localised responses to stress. These include blood clotting, wound healing, accommodation of the eye to light, and response to pressure. All forms of the LAS share the following characteristics:

• the response is localised; it does not involve entire body systems

• the response is adaptive, meaning that a stressor is necessary to stimulate it

• the response is short-term; it does not persist indefinitely

• the response is restorative, meaning that the LAS helps restore homeostasis to the body region or part.

Two localised responses, the reflex pain response and the inflammatory response, are described here as examples of the LAS. Nurses encounter these responses in many healthcare settings.

REFLEX PAIN RESPONSE

The reflex pain response is a localised response of the central nervous system to pain (see Chapter 41). It is an adaptive response and protects tissue from further damage. The response involves a sensory receptor, a sensory nerve to the spinal cord, a connector neuron within the spinal cord, a motor nerve from the spinal cord and an effector muscle. Examples are the unconscious, reflex removal of the hand from a hot surface, and a muscle cramp.

INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE

The inflammatory response is stimulated by trauma or infection. This response localises the inflammation, thus preventing its spread, and promotes healing. The inflammatory response may produce localised pain, swelling, heat, redness and changes in functioning. It occurs in three phases.

• The first phase involves changes in cells and the circulatory system. Initially, narrowing of blood vessels occurs at the injury to control bleeding. Then histamine is released at the injury, increasing blood flow to the area and increasing the number of white blood cells to combat infection. Almost simultaneously, kinins are released to increase capillary permeability to permit the flow of proteins, fluid and leucocytes to the injury. At this point the localised blood flow decreases, keeping leucocytes in the area to fight infection.

• The second phase is characterised by release of exudate from the wound. Exudate is a combination of fluid, cells and other substances produced in the area of injury, which may be a cut, laceration or surgical incision. The type and amount of exudate vary from injury to injury and from person to person.

• The last phase is repair of tissue by regeneration or scar formation. Regeneration replaces damaged cells with identical or similar cells. Scar formation replaces original tissue that is not functional.

The inflammatory response alerts the nurse that the body is adapting to a local injury. During adaptation, the inflammatory response protects the body from infection and promotes healing.

General adaptation syndrome

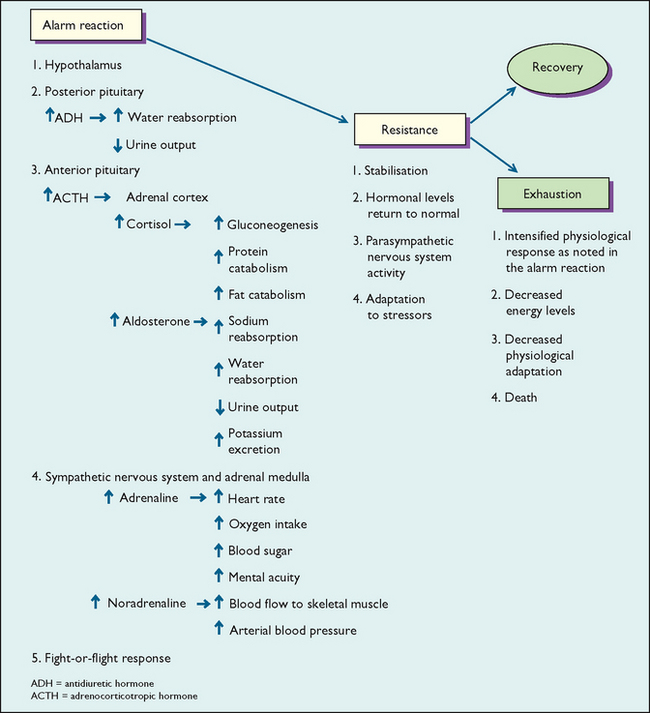

The GAS is a physiological response of the whole body to stress. It involves several body systems, mainly the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system. Some textbooks refer to the GAS as the neuroendocrine response. The GAS consists of the alarm reaction, the resistance stage and the exhaustion stage (Figure 42-1).

ALARM REACTION

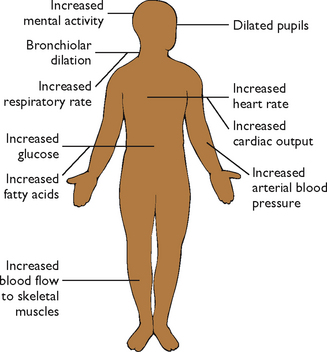

The alarm reaction involves the mobilisation of the defence mechanisms of the body and mind to cope with the stressor. Hormone levels rise to increase blood volume and thereby prepare the person to act. Other hormones are released to increase blood glucose levels to make energy available for adaptation. Increased levels of other hormones—adrenaline and noradrenaline—result in an increased heart rate, increased blood flow to muscles, increased oxygen intake and greater mental alertness.

This extensive hormonal activity prepares the person for the fight-or-flight response. Cardiac output, oxygen intake and respiratory rate increase; the pupils of the eyes dilate to produce a greater visual field; and the heart rate increases for more energy. Other changes occur to prepare the person to act (Figure 42-2). With this increased mental energy and alertness, the person is prepared to fight or flee the stressor.

During the alarm reaction, the person is faced with a specific stressor. The person’s physiological response is extensive, involving major systems of the body, and it may last from a minute to many hours. If the stressor is extreme or remains for a long time, there may be a threat to life. If the stressor is still present after the initial alarm reaction, the person progresses to the second phase of the GAS, resistance.

RESISTANCE STAGE

In the resistance stage the body stabilises, and hormone levels, heart rate, blood pressure and cardiac output return to normal—the person is attempting to adapt to the stressor. If the stress can be resolved, the body repairs damage that may have occurred, i.e. homeostasis is maintained. However, if the stressor remains present, as in continued blood loss, debilitating disease or ongoing severe mental illness, and adaptation fails, the person enters the third phase of the GAS, exhaustion.

EXHAUSTION STAGE

The exhaustion stage occurs when the body can no longer resist stress and when the energy necessary to maintain adaptation is depleted. The physiological response is intensified, but the person’s energy level is compromised and adaptation to the stressor diminishes. The body is unable to defend itself against the impact of the stressor, physiological regulation diminishes and, if the stress continues, death may result.

Psychological response

Psychological adaptive behaviours influence how a person copes with stress. These behaviours are directed at stress management and are acquired through learning and experience as a person identifies acceptable and successful behaviours.

Psychological adaptive behaviours can be constructive or harmful. Constructive behaviours help a person accept the challenge to resolve conflict. Even anxiety can be constructive; for example, it can signal that a threat is present so that a person can take measures to reduce its severity. Harmful behaviours, on the other hand, do not help a person cope with a stressor. Harmful behaviours affect reality orientation, problem-solving abilities, personality and, in severe circumstances, the ability to function. The use of alcohol or drugs, for example, may alleviate immediate distress, but in the longer term hamper a person’s ability to deal with stress.

Psychological adaptive behaviours are also referred to as coping mechanisms. Such mechanisms can be problem focused, involving the use of direct problem-solving techniques to cope with the threats; or emotion focused, involving the use of strategies to manage one’s emotional response to the stressor.

Problem-focused coping behaviours involve using cognitive abilities to reduce stress, solve problems and resolve conflicts. Task-oriented behaviours enable a person to cope realistically with the demands of a stressor. The three general types of task-oriented behaviour are attack behaviour, withdrawal behaviour and compromise (Box 42-3).

BOX 42-3 PSYCHOLOGICAL ADAPTIVE BEHAVIOURS

TASK-ORIENTED BEHAVIOURS (PROBLEM-FOCUSED)

• Taking action to remove or overcome a stressor or to satisfy a need.

• Withdrawal behaviour is removing the self physically or emotionally from the stressor.

• Compromise behaviour is changing the usual method of operating, substituting goals or omitting the satisfaction of needs to meet other needs or to avoid stress.

EXAMPLES OF EGO-DEFENCE MECHANISMS (EMOTION-FOCUSED)

• Compensation is making up for a deficiency in one aspect of self-image by strongly emphasising a feature considered an asset.

• Conversion is unconsciously repressing an anxiety-producing emotional conflict and transforming it into non-organic symptoms.

• Denial is avoiding emotional conflicts by refusing to consciously acknowledge anything that might cause intolerable emotional pain.

• Displacement is transferring emotions, ideas or wishes from a stressful situation to a less-anxiety-producing substitute.

• Identification is patterning behaviour after that of another person and assuming that person’s qualities, characteristics and actions.

• Regression is coping with a stressor through actions and behaviours associated with an earlier developmental period.

Emotion-focused coping behaviours can be intentional, e.g. seeking support from friends, or they may involve the use of unconscious processes like ego-defence mechanisms—the purpose of which is to regulate emotional distress and thus give a person protection from anxiety and stress. Ego-defence mechanisms, first described by Sigmund Freud and later elaborated on by his daughter Anna (Freud, 1966), are unconscious behaviours that offer psychological protection from a stressful event. They are used by everyone and help protect against feelings of distress and anxiety. Occasionally, a defence mechanism can become distorted and is no longer able to help the person adapt to a stressor. There are many ego-defence mechanisms (see Box 42-3). They are often activated by short-term stressors and usually do not result in psychiatric disorders.

Psychological/emotional issues

Individual personality involves a complex relationship among many factors. The emotional reaction to prolonged stress is determined by examining the client’s current lifestyle and stressors, previous experience with stressors, past successful coping mechanisms, role functions, self-concept and hardiness, which is a combination of three personality characteristics thought to militate against stress—sense of control over life events, commitment to meaningful activities, and anticipation of challenge as an opportunity for growth. Hardy individuals adapt more readily to stress because of the more-positive ways they appraise stressful situations (Dolbier and others, 2007).

Developmental factors

Prolonged stress can affect the ability to complete developmental tasks. In any developmental stage, a person normally encounters tasks and engages in behaviours characteristic of the stage (Santrock, 2009). In extreme forms, repeated stress can lead to maturational crisis. For instance, if parents or the environment prevent a young child from developing a sense of autonomy, the child may experience stress, which is indicated by excessive dependence on others or passive inactive behaviour (Erikson, 1963).

Intellectual factors

Studies have shown that repeated stress can have consequences for brain function, especially in short-term memory (Brewin and others, 2007). A person’s ability to acquire new knowledge or skills may also be impaired. This is especially important information for the nurse who is involved in client teaching. The client may not be able to learn new skills or about a disease process until prolonged stressors have been resolved or alternative forms of coping have been found. This means that it may be necessary to provide information to the client on repeated occasions and in writing so that they can refer to it later if necessary.

Social determinants

The social determinants of health include physical environment, family, lifestyle, cultural and political issues. The word ‘family’ means different things to different people (see Chapter 18) and is not static. In Western cultures the nuclear family of the 1950s has been joined by sole-parent families, blended families and families with alternative patterns of relationships. In non-Western cultures. family is viewed as extending beyond the parent/child dyad to also include grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins.

Each individual has their own perception of the role and importance of family. Western cultures have an individualistic perspective, and attribute the responsibility of health, for example, to the individual. Collective cultures, on the other hand, emphasise the role that family and community play in the health of the group members (Sawrikar and Katz, 2008). New Zealand Māori, for example, believe that health is influenced by four domains: mind, spirit, family (extended) and the physical world (Ministry of Health, n.d.). It is therefore important to be cautious when applying theories about stress and health which are derived from Western cultures to people from collectivist societies such as Australian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders, New Zealand Māori, immigrants and refugees.

Furthermore, the family unit itself can be a cause of stress. Sole parents can face the burden of caring for children on their own while working and running a home. Teenage parents, sole parents and homosexual couples with children may face the added stress of discrimination. Economic concerns, homelessness, violence and illness are all factors that can increase the stress within a family. Poor communication habits and maladaptive behaviours among its members can create crises within a family structure and limit adaptation (World Health Organization, 2008).

Lifestyle decisions can be important factors that influence stress. A father may know that smoking can lead to cardiovascular disease or cancer. However, he may continue to smoke because it helps him cope with an unhappy job situation. His children may then ask him to stop smoking. If he is unable or unwilling to quit, he may feel like a failure, thereby precipitating more stress. If he is successful with quitting smoking, then he may feel positive about himself and replace smoking with a daily exercise regimen. His children may also feel affirmed because a parent listened to their concerns.

Each social and cultural group has its own views regarding stress. Education, poverty, spirituality, support systems and accepted coping mechanisms all influence these beliefs (see Chapter 17). Social instability can also play a role in stress and adaptation. For instance, the impact of colonisation on indigenous populations has imposed considerable stress resulting in significantly poorer health outcomes, both physically and mentally (Central Australian Aboriginal Congress, 2011; Ministry of Health, 2011).

Spiritual considerations

Spirituality begins early in life and is influenced by culture, beliefs and life experiences (Chapter 17). Just as the concept of family is unique to each person, spirituality is also highly individual. While the concepts of religion and spirituality are often used interchangeably, they are not the same. Religion is a system of organised beliefs and worship. Spirituality demonstrates a unique capacity for love, joy, caring, compassion and for finding meaning in life’s difficult experiences (Emmons, 2005).

During times of stress, some clients rely on their faith whereas others abandon their practices out of disillusionment and anger. Although spirituality can be a difficult subject for caregivers to approach, it is an essential part of the client’s wellbeing (see Chapter 17).

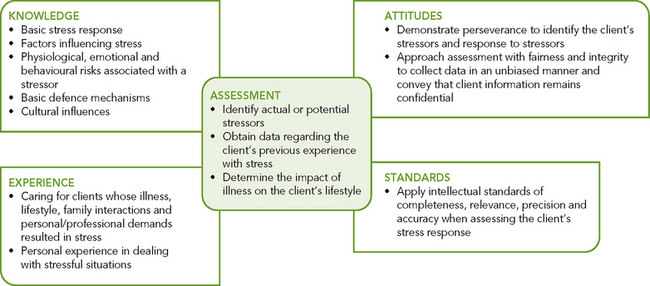

Critical thinking synthesis

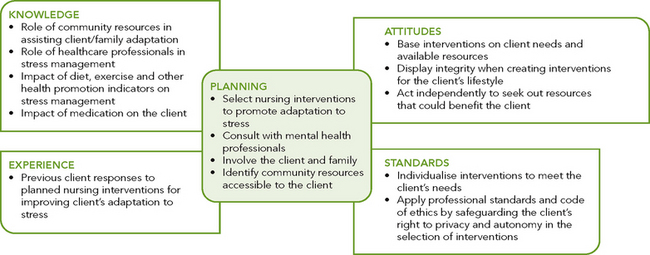

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from clients, critical-thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require the nurse to anticipate the information necessary, analyse the data and make decisions regarding client care. During assessment (Figure 42-3), the nurse considers all elements that build towards making a relevant client assessment and plan appropriate care.

In the case of stress and adaptation, the nurse integrates knowledge from nursing and other disciplines, previous experiences, and information gathered from clients to understand stress and its impact on the client and family. In addition, the use of critical-thinking attitudes such as perseverance is needed to form a plan of care to provide appropriate stress management. To fully understand how stress has affected the client, the nurse gathers complete and accurate data. Physical, emotional, social, cultural and developmental state require assessment using a broad knowledge base to ensure that the client’s needs are accurately identified.

NURSING PROCESS

ASSESSMENT

Each client has unique perceptions and responses to stress. A person’s perception of a stressor is complex and influenced by beliefs and norms, life experiences and patterns, environmental factors, family structure and function, developmental stage, past experiences with stress, and coping mechanisms. Because nurses spend a great deal of time with clients and their families or friends, they are well positioned to critically analyse coping responses. Stress-response behaviours, both verbal and non-verbal, should be assessed. Nurses provide care for clients in various settings and are thus able to assess reactions to stress. The nurse assesses for indicators of stress and coping in all dimensions of adaptation and synthesises that information (see Figure 42-3). The nurse’s knowledge, experience and attitudes are especially important when using critical thinking during the assessment phase of a client’s individual plan of care.

Physiological indicators

Physiological indicators of stress are objective, more readily identified and can be commonly observed or measured (Box 42-4). However, they are not always observed in all clients experiencing stress, and they vary among individuals. Vital signs are usually elevated, and the client may appear restless and unable to concentrate. These indicators can appear at any stage of stress.

BOX 42-4PHYSIOLOGICAL INDICATORS OF STRESS

Increased muscle tension in neck, shoulders, back

Elevated pulse and increased respiration

Abnormal laboratory findings: elevated adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol and catecholamine levels, and hyperglycaemia

Restlessness: difficulty falling asleep or frequent awakening

The duration and intensity of the symptoms are directly related to the perceived duration and intensity of the stressor. Physiological indicators arise from a variety of systems. Therefore the assessment of stress involves collecting data from all systems. The link between psychological stress and disease is often called the mind–body interaction. Research has shown that psychosocial stress in children can adversely affect rates of infection and immune function (Caserta and others, 2008).

During any stage, there may be physical symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or headache. Physical appearance can be changed, posture may be slumped, hygiene and grooming may be poor and style of dress may differ. Prolonged stress has been linked with cardiovascular and gastrointestinal diseases. Some cancers and immunological disorders, migraine headaches, infertility, burnout and irritability are associated with prolonged, unresolved stressors. In addition, stress is known to exacerbate neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and Tourette’s syndrome (Box, 2008; Fitzpatrick and others, 2010).

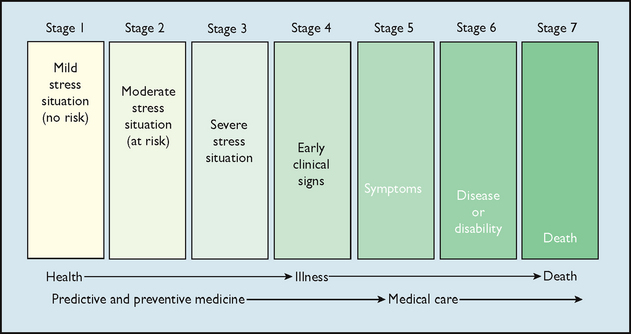

Mild stress situations are stressors that everyone encounters regularly, such as oversleeping, traffic jams, a flat tyre or criticism from a supervisor. Mild stress situations do not usually produce chronic physiological damage. Such situations usually last a few minutes to a few hours. By themselves, these stressors are not significant risks of symptom development. However, multiple mild stressors over a short time can increase risk of illness. The stimulus may be an accumulation of minor life events as described by Kanner and colleagues in a study which compared the stress from ‘daily hassles’ and ‘uplifts’ with the stress produced by major life events (Kanner and others, 1981).

Moderate stress situations last longer, from several hours to days. For example, an unresolved disagreement with a co-worker, a sick child or the prolonged absence of a family member are moderate stress situations. These may create a risk of medical illness or worsening of a chronic illness.

Severe stress situations are chronic situations that may last several weeks to several years, such as continual marital disagreements, prolonged financial difficulties and long-term physical illness. The more frequent and longer the stress situation, the higher the health risk (Caserta and others, 2008; Holmes and Rahe, 1967).

The development of stress-related disease can be examined in terms of the health–illness continuum (Figure 42-4). As a person’s stress increases, stress behaviours increase gradually, which decreases energy and adaptive responses. Identifying the mind–body interaction is crucial for predicting the risk of stress-related illness. A nurse also critically assesses the client’s perception of stressors, because what may seem a mild stress situation to the nurse may be extremely disturbing to the client.

Major life events

The theory that major life events are a stimulus for stress emerged from the research of Holmes and Rahe, who hypothesised that major or frequent changes in one’s life predisposes the individual to illness due to the cumulative effect of the life stressors. This hypothesis was proposed by the researchers after they observed that tuberculosis (TB) infection commonly followed a major life crisis or multiple life crises. They subsequently developed a tool to measure the impact of life changes on health and to predict individual vulnerability to illness—the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) (Holmes and Rahe, 1967; Rahe and others, 2000).

This tool consists of 43 items, of which 17 are rated as desirable (e.g. going on vacation) and 18 are rated as undesirable (e.g. death of a close friend). The remaining 8 are classified as neutral, e.g. ‘major change in responsibilities at work’. Such a change might be the consequence of a promotion, which is desirable; but it could be the result of a restructuring and reduction of staff at a person’s workplace, which would be undesirable as there would be fewer people to undertake the workload.

Items in the SRRS are given a weighting which reflects the magnitude of the stressful stimulus. For example, the death of a spouse was found to be the most stressful life event and was given a score of 100. A total score of 150–299 for the preceding year places the individual at moderate risk for illness, whereas a total score of 300 in the preceding 6 months or more than 500 in the preceding year places the individual at high risk of developing a stress-related illness.

Since its development in the 1960s, the Holmes–Rahe SRRS has been one of the most widely cited tools in stress research. Thirty years later, Scully and colleagues replicated the research to examine the usefulness of the tool as an indicator of health risk and to consider the validity of criticisms raised in the literature in relation to the tool. Their research found that the relative weightings and rank order of the selected life events remained valid, and they concluded that SRRS continues to be ‘a robust instrument for identifying the potential for the occurrences of stress-related outcomes’ (Scully and others, 2000:875).

Psychological indicators

Exposure to a stressor results in physiological and psychological adaptive responses. As stated earlier, psychological adaptive behaviours increase a person’s ability to cope with stressors. The nurse should assess the client for maladaptive behaviours that do not help the person cope with a stressor. Conversion, denial and displacement are examples of maladaptive ego-defence mechanisms. An example of denial is a student addicted to cocaine who says he could quit taking drugs whenever he chooses. To some, the abuse of alcohol or drugs may seem to be an adaptive behaviour. In reality, it increases rather than decreases the stress.

Developmental indicators

Erikson’s psychosocial theory describes the developmental stages that occur through the life span (see Chapter 19). At each stage the individual attempts to resolve a conflict, for example trust versus mistrust in infancy (Erikson, 1963). Failure to achieve the developmental task of a particular stage in the life span hinders psychological growth and produces stress.

Infants or young children generally encounter stressors at home. When nurtured in responsive, empathetic environments, they are able to develop healthy self-esteem and ultimately learn healthy adaptive coping responses (Santrock, 2009). However, the absence of parent figures or their failure to provide the security needed to develop a sense of trust can be stressors. In later life there may be chronic distrust, resulting in withdrawal and disturbed interpersonal relationships (Santrock, 2009).

School-age children normally develop a sense of adequacy. They begin to realise that accumulation of knowledge and mastery of skills can help them accomplish goals, and self-esteem develops through friendships and sharing with peers. At this stage, stress is indicated by the inability or unwillingness to develop friendships.

Adolescents normally develop a strong sense of identity but at the same time need to be accepted by peers. Adolescents with strong social support systems report an increased ability to adjust to stressors, but adolescents without social support systems often report increased psychosocial problems. In a study conducted by Rueger and colleagues (2010), adolescents with poor parental and peer support were found to have more depressive symptoms, anxiety, self-esteem and academic adjustment problems than young people who reported strong family and social support. There are many stressors in this age group, including conflicts involving sexual drive and expected standards of behaviour. Prolonged conflict may present as indecision and confusion, rebellion, depression or anxiety.

Young adults are in transition from youthful experiences to adult responsibilities. They must prepare for careers, living alone, forming intimate relationships and, perhaps, starting families. Conflicts between work, study, relationships and family responsibilities may be a source of stress.

Middle-aged adults are usually involved in family building, creating stable careers and perhaps caring for older parents. They are generally able to control desires and in some cases substitute the needs of partners, children or parents for their own needs. Stress can result, however, if they feel that too many responsibilities have been placed on them. Several studies have looked at the impact of stressors on the family caregiver’s role. Middle-aged adults have been called the ‘sandwich generation’ because they are often responsible for chronically ill parents while raising their own families. Because of the stressors involved, caregivers have reported increases in fatigue, minor illnesses (e.g. colds and influenza), depression and dissatisfaction with family interaction (Gallagher-Thompson and Coon, 2007).

Older adults are commonly faced with adapting to changes in family and perhaps to the death of partners or long-time friends. Older adults must also adjust to changes in physical appearance and physiological functioning (see Working with diversity). Major life changes such as retirement can also be stressful. Some older adults must cope with relocation to some form of institutionalised living. Moving to a nursing home may be made less stressful for an older person if social support is provided by staff and other residents during the transition from home to care (Lee, 2010).

Emotional behavioural indicators

Emotions are sometimes assessed directly or indirectly by observing a client’s behaviour. Stress affects emotional wellbeing in many ways (Box 42-5). Because stress affects each person differently, the nurse should attempt to establish a rapport with the client before assessing the client’s emotional status. The client may or may not be aware of behavioural responses. Non-verbal cues such as anger and inappropriate crying are extremely important. Questions that deal with self-worth, current lifestyle and previous experience with stressors are critical.

BOX 42-5 BEHAVIOURAL AND EMOTIONAL INDICATORS OF STRESS

Increased use of chemical substances

Change in eating habits, sleep and activity pattern

Emotional outbursts and crying

Decreased productivity and quality of job performance

Tendency to make mistakes (i.e. poor judgment)

Diminished attention to detail

Preoccupation (i.e. daydreaming or ‘spacing out’)

Inability to concentrate on tasks

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON OLDER ADULTS

• Ageing is often associated with declines in functional abilities due to the normal ageing process. Although this may be true, evidence suggests that coping and adaptation functions are surprisingly well preserved throughout the entire life span (Young and others, 2009).

• Health problems are common among the elderly and can be a cause of stress.

• Since many older adults are on a fixed income, the cost of medical care can be a huge stressor. The nurse may need to involve other disciplines such as social services to help the client to access services.

• Loneliness and isolation can be a major stressor for the elderly. Studies have suggested that older people’s perceptions of stress are less likely to lead to depression if high social resources are present (Kaasa, 2009).

• Older adults effectively use religious coping in response to medical illness and disasters (Levin and Chatters, 2008).

• Before scheduling a doctor’s appointment or a needed test, explore the transport needs of the older client. Dependency is a large stressor for the elderly, and necessary steps should be taken to avoid this issue.

Kaasa K 2009 Loneliness in old age: psychosocial and health predictors. Norweg J Epidemiol 8(2):195–201; Levin J, Chatters M 2008 Religion, aging, and health: historical perspectives. Current trends and future directions. J Relig Spirituality Aging 20(1/2):153–72; Young Y, Frich KD, Phelan EA 2009 Can successful aging and chronic illness coexist in the same individual? A multidimensional concept of successful aging. J Am Med Dir Assoc 10(2):87–92.

Cognitive indicators

Prolonged stress can manifest itself in the cognitive dimension and have observable indicators. A person’s ability to acquire new knowledge or skills is impaired. A person’s cognitive appraisal of a situation may also be inaccurate and frequently negative. Stress can impede communication between the person and others. A shortened attention span, inability to think clearly and the tendency to focus narrowly may render the person unable to solve problems and resolve conflicts. Therefore, increased dependence on others occurs as the person feels unable to cope with everyday life.

Social determinants

The social determinants approach to understanding health argues that the biomedical model is insufficient to explain health and illness. It proposes that the attributes of a society such as the level of wealth, differences in income, poverty and government policies dealing with these inequalities are important indicators of the health of populations (Parry and Willis, 2009).

FAMILY

It is very important for the nurse to understand that nursing interventions for the client can affect the entire family. That is why assessment of the whole family and its members’ roles is essential. Culture, structure and concept of the family are also important when assessing how a family copes with stress. Major life events should be explored. Job instability, death or illness of a family member and relocation are examples of huge family stressors. The nurse should also assess what the client believes effective emotional support is and if that support is provided by the family structure.

LIFESTYLE

Up until the mid-20th century, infectious diseases were the leading causes of death in Western countries, but since then antibiotics and public-health initiatives such as improved living conditions, access to nutritious food and better sanitation methods have lowered the death rate. Now the leading causes of death are diseases involving lifestyle stressors (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010). There is a variety of lifestyle choices that can create physical and/or psychological stress in a client. Smoking, overeating, insufficient physical activity, drug abuse and chronic sleep deprivation are examples. Regular exercise, adequate rest and a nutritious diet are positive lifestyle choices that can reduce stress. Nurses assess clients for both positive and negative issues in relation to stress. Lifestyle choices such as unprotected sex with multiple partners pose a very large stressor in the form of a range of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Smoking and drug or alcohol consumption during pregnancy can cause stress to the fetus.

SOCIOCULTURAL FACTORS

Assessing stressors and coping resources in the social dimension involves exploring with the client the amount, type and quality of social interactions present. Stressors on the family may create dysfunction that affects the client or the family as a whole (Sawrikar and Katz, 2008). The nurse must also be aware of cultural differences in stress responses or coping mechanisms. For example, an Asian-Australian client may prefer obtaining social support from family members rather than professional assistance (Sawrikar and Katz, 2008), and may not appreciate the importance of regular health screening (Kwok and Sullivan, 2006). See Working with diversity.

SPIRITUAL INDICATORS

Spirituality refers to how the individual understands their place in the world (society and the environment), their relationship with family, friends and others and the meaning they ascribe to their life. People use spiritual resources to adapt to stress in many ways, but stress can also manifest itself in the spiritual dimension. Severe stress may result in anger at a supreme being, or the person may view the stressor as punishment. Stressors such as acute illness or the death of a loved one may threaten a person’s meaning of life and can lead to depression. When providing care to a spiritually affected client, it is important for the nurse to seek an understanding of the meaning of spiritual experience from the person’s perspective.

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON CULTURAL CARE

The contrast between Chinese and Western approaches to health may be a source of stress for Chinese immigrants in Western countries. Western medicine is very technical and has a strong biological base. Chinese culture, including its medicine, is strongly linked to religious and social beliefs. Therefore newly immigrated and first-generation Chinese Australians/New Zealanders may experience conflict and stress seeking Western medicine. Often they will treat minor or chronic illness with Chinese medical services (herbal remedies, acupuncture, massage therapy and skin scraping) and seek Western medical services only for acute or serious problems (Jette and Vertinsky, 2010). Thus, some Chinese immigrants may be acutely ill when they first seek medical attention.

Language difficulties and cultural beliefs can also influence how individuals engage in healthcare. A study by Kwok and Sullivan (2006) found that Chinese Australian women’s views about health, the lifecycle and disease prevention were influenced by cultural traditions and beliefs. The Chinese Australian women in the study were fatalistic about their health and therefore did not perceive risk for breast cancer in the same way that Australian-born women did. Consequently, they were less likely to engage in breast cancer screening programs. The authors concluded that screening programs need to take these cultural differences into consideration and utilise additional strategies to encourage older Australian Chinese women to engage in early screening programs.

Jette S, Vertinsky P 2010 Exercise is medicine: understanding the exercise beliefs and practices of older Chinese women immigrants in British Columbia, Canada. J Aging Stud 25(3):272–84; Kwok C, Sullivan G 2006 Influence of traditional Chinese beliefs on cancer screening behaviour among Chinese-Australian women. J Adv Nurs 54(6):691–9.

Client expectations

It is important to remember that every person perceives and reacts differently to stress. Culture, life experiences and family belief systems all play a part. Pang and Suen (2008) found that nurses rated experiences in the intensive care unit (ICU) to be more stressful than the patients did, and nurses tended to over-emphasise the stressful nature of the ICU. Complete and accurate assessment of the patient and their support networks is essential in tailoring care to the individual’s needs. Asking the patient what is expected regarding what is stressful and how it could be reduced assists in the setting of achievable goals identification of interventions. The very best quit-smoking program does little good if the client does not recognise smoking as a problem. Therefore, in planning patient care nurses need to be aware of their own value system as well as those of the patient.

Developing a nursing care plan

Stress can be observed in multiple ways: physical (e.g. elevated blood pressure), emotional (e.g. sad mood), cognitive (e.g. forgetfulness), social (e.g. feelings of isolation) and spiritual (e.g. feelings of despair). The nursing assessment of these domains must be supported by objective measures and/or subjective descriptors of stress and its consequences.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

A review of assessment data enables the nurse to identify potential or actual stressors and observe the client’s response. Interpretation of the assessment data by using nursing knowledge and experience leads to identification of problems to be addressed. For example, changes in appetite and sleeping patterns and increased frequency of headaches are frequently observed in clients experiencing stress.

PLANNING

Planning nursing care by using critical thinking and incorporating an evidence base ensures that the client’s care is appropriate to achieve the set goals. During planning, the nurse again synthesises information from multiple sources (Figure 42-5).

In developing a care plan for each identified problem, the goals should be individualised and realistic with measurable outcomes. Sensitivity to specific cultural issues and expressions of adaptation will also promote a sense in the client of feeling well cared for. It is important to focus on coping strategies that are both realistic and appropriate to the client’s needs. They should also involve the client and family, if possible, to ensure that their views are considered because research has shown that client, family and nurse perceptions are not always the same (Wåhlin and others, 2009) (see Research highlight).

Stress management techniques are designed to match the client’s actual and potential stressors. The general goals for clients who require stress management include the following:

IMPLEMENTATION

Stress management may be seen as a health-promotion activity or an intervention that modifies a response to illness. The focus depends on the purpose of the nursing interventions based on the client’s needs.

Summary

Experiences of critically ill patients are an important aspect of the quality of care in intensive care units (ICUs). If next-of-kin and staff try to empower the patient, this is probably performed in accordance with their beliefs about what patients experience as empowering. As ICU patients often have difficulties communicating, staff and next-of-kin need to interpret their wishes, but there is limited knowledge about how correct a picture next-of-kin and staff have of the intensive care patient’s experiences.

The aim of this study was to compare ICU patients’ experiences of empowerment with next-of-kin and staff beliefs. Interviews with 11 ICU patients, 12 next-of-kin and 12 staff were conducted and analysed using a content analysis method.

The findings showed that the main content is quite similar between patient experiences, next-of-kin beliefs and staff beliefs, but a number of important differences were identified. Some of these differences were regarding how joy of life and the will to fight were generated, the character of relationships, teamwork, humour, hope and spiritual experiences. Staff and next-of-kin seemed to regard the patient as more unconscious than the patient him/herself did.

CAREGIVER ROLE STRAIN—CASE STUDY: CARL

ASSESSMENT*

When Janet Rich, RN, first goes to Carl’s house, she finds the home in slight disarray. The lawn is overgrown, there are dirty dishes in the sink, and an empty soup can is sitting on the kitchen counter. Carl is standing in the living room folding clothes from a laundry basket, and Evelyn, Carl’s wife, is sitting in a chair watching TV. Evelyn was recently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia. Carl appears very tired and depressed. He continues to fold clothes during the visit, stating, ‘There’s so much to do that I don’t even know where to begin.’ Carl states that he has lost 9 kilograms in the past 6 months and that his appetite has been poor. Until recently, Evelyn has cooked all of their meals. Carl describes being awakened 3–4 times a night to find Evelyn wandering in the house. He states that he has no outside activities and his children live in other states. He does have several close friends who live nearby but denies any knowledge of community resources.

PLANNING

| INTERVENTIONS | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| Caregiver support | |

|

• Help client establish a consistent care routine. • Discuss ways to simplify care routine such as hiring a neighbour’s son to mow the lawn, buying frozen meals, having groceries delivered, having a cleaning service twice a month. • Identify sources of respite care by encouraging client to identify available friends who can help with caregiving. • Explore community resources such as home healthcare, adult day care and meals on wheels with client. • Teach client stress-management techniques. • Set up monthly health checks for client that include vital sign and weight checks. |

Routines can help tasks be simplified and more time-efficient. Creates free time for client and may help decrease feelings of being overwhelmed. Supporting the carer of a person with dementia may delay or prevent the admission of the person to a nursing home (Brown and Abdelhafiz, 2011; Podgorski and King, 2009). Feelings of burden have been found to be lower among caregivers with informal and formal supports (Podgorski and King, 2009) Stress and anxiety can precipitate physical illness (Arranz and others, 2007). |

*Defining characteristics are shown in bold type.

Health and wellness promotion

Lifestyle decisions can have a dramatic impact on the stress experienced in everyday life. Regular exercise, good nutrition combined with a low-fat, high-fibre diet, adequate rest, effective time management, interactions with positive support systems and humour are examples of habits that can positively affect physical and mental health. Nurses are in an excellent position to educate clients and families about the importance of health promotion and the impact it can have on stress reduction. Helping clients and families to understand their particular stress response and its probable causes is a significant step in stress reduction. Attempting to eliminate all stressors is unrealistic. However, the nurse can reduce some stressors and thereby provide the client with a greater sense of control. Several methods that may help in stress reduction are outlined below.

TIME MANAGEMENT

People who use time efficiently generally experience less stress because they feel more in control of their lives. A nurse can help clients set priorities if they are feeling overwhelmed or are immobilised.

Controlling the demands of others is essential for effective time management. Few people are able to meet all requests made by others. It is important to learn to recognise which requests can be realistically met, which need to be negotiated and which ones can be assertively declined. Defining a period of time in which to meet specific goals also reduces a sense of urgency and increases feelings of control.

REGULAR EXERCISE

A regular exercise program improves muscle tone and posture, controls weight, reduces tension and promotes relaxation. In addition, exercise reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease and improves cardiopulmonary functioning. A client with a history of chronic illness, at risk of developing an illness or over the age of 35 years should begin a physical exercise program only after discussing it with a doctor. In general, for a fitness program to have positive physical effects, a person should exercise at least 3 times a week for 30–40 minutes. However, it is now accepted that exercise can be equally useful in smaller slices, for example in periods of 10 minutes at a time, with a goal of accumulating 30–40 minutes each day (Gingerich, 2007; Kahn, 2007).

Everyone should use warm-up exercises before vigorous exercise such as jogging, aerobic dancing or tennis. Warm-up exercises stimulate blood flow to the muscles and increase flexibility. They reduce the risk of damage to the musculoskeletal system during exercise. Similarly, after vigorous exercise, people should do cool-down exercises rather than stopping abruptly. For example, after jogging or aerobic dancing, people should walk around at a moderate pace, gradually slowing and stopping. Cool-down exercises allow the cardiovascular, pulmonary, musculoskeletal and metabolic systems to gradually return to their resting states.

Exercise programs are effective in decreasing the severity of stress-related conditions such as hypertension, obesity, tension headaches, fatigue, mental exhaustion, irritability and depression (Lampinen and others, 2006). Exercise also promotes release of endogenous opioids that create a feeling of wellbeing (Dishman and O’Connor, 2009).

NUTRITION AND DIET

Nutrition and exercise are closely related. Food provides the fuel for activity and increased exercise, which improves circulation and the delivery of nutrients to body tissues. Everyone is encouraged to maintain weight according to standard ranges for sex, age and body build. In addition to avoiding overeating or undereating, people should be aware of the nutritional quality of foods. Too much fat, caffeine, salt or sugar can upset the body’s metabolic functioning; deficiencies in vitamins, minerals and nutrients can also cause metabolic problems. Poor dietary habits can worsen a stress response and make a person irritable, hyperactive and anxious. This impairs the ability to meet personal, family and role responsibilities. Nursing measures for helping a client meet nutritional needs are detailed in Chapter 36.

REST

An established, habitual pattern of sufficient rest and sleep is also important for managing stress. People experiencing stress should be encouraged to allow time for rest and sleep. Sleep not only refreshes the body, but also helps a person become mentally relaxed. A client may need specific help in learning to relax and fall asleep.

SUPPORT SYSTEMS

A support system of family, friends and colleagues who will listen and offer advice and emotional support is beneficial to a person experiencing stress (Barkway, 2009). As a nurse you can use therapeutic communication to assist clients to identify the social resources and support networks available to them. Or, if stress is the result of social isolation or exclusion, nursing strategies are aimed at helping clients develop new social networks.

Acute care

CRISIS INTERVENTION

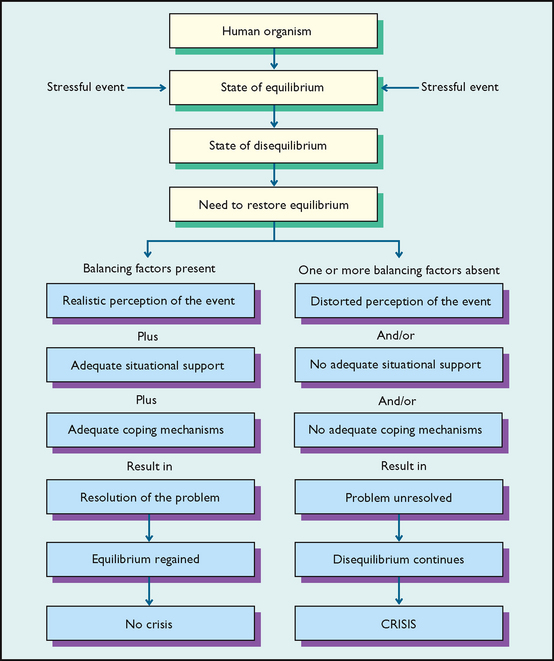

Crisis intervention is a therapeutic technique for helping a client resolve a particular, immediate stress problem. Crisis intervention does not involve an in-depth analysis of a situation, but tackles the immediate, urgent need for stress reduction. The goal is to restore the person to the pre-crisis level of functioning as quickly as possible. A crisis occurs when people encounter problems or stress situations with which they are unable to cope in usual ways. A crisis does not necessarily denote occurrence of a traumatic event. However, even if this happens, it can be an opportunity for personal growth if the crisis is successfully mastered (Chan and Chan, 2006).

Clients and nurses are at risk of two types of crises: situational and developmental. A situational crisis arises suddenly in response to an external event or conflict involving a specific circumstance. Symptoms associated with situational crises are transient, and the episode is usually brief. Situational crises include giving birth, major role changes, acute physical illness, physical or sexual assault, family changes such as remarriage or the death of a family member, and unexpected unemployment.

A developmental crisis occurs when a person is unable to complete the developmental tasks of a psychosocial stage (Erikson, 1963) and is therefore unable to continue developing. A developmental crisis can occur at any point in life if circumstances prevent a person from meeting the challenge of a particular stage.

After determining that a client is experiencing a crisis, the nurse plans and implements specific measures to help resolve it. Aguilera (1998) has developed an approach to intervention that can be used for both situational and developmental crises (Figure 42-6). This approach enables the nurse to understand how a stressful event has led to a state of crisis. Resolution of the crisis depends on the person’s realistic perception of the stressful event, use of adequate coping mechanisms and the availability of social support. If the crisis has arisen because perception of the event is distorted, the nurse helps the client perceive the stressful event realistically. If the crisis has arisen because of a lack of situational support or coping mechanisms, the nurse initiates measures to incorporate regular diet and exercise into the client’s lifestyle and suggests appropriate support groups. The nurse then evaluates the extent to which the client is able to resolve the crisis with these means.

Restorative care

The nurse can help the client make lifestyle choices that are healthy and stress-reducing. Appropriate use of humour, spirituality and stress-management techniques are examples of these choices. Although this material is presented with respect to restorative care, the techniques can be used in all healthcare settings.

Humour as therapy was first popularised in the lay literature by Norman Cousins (1979). The ability to perceive fun and laugh alleviates stress. The physiological hypothesis is that laughter releases endorphins into the circulation and feelings of stress are relieved. Laughter has been shown to increase immune and cardiac system functioning (Bennett and Lengacher, 2009), lower blood pressure, neutralise adrenaline and increase energy and fertility (Hull-Rodgers, 2007). Nurses can initiate therapeutic activities by encouraging clients to relate past humorous anecdotes or developing a ‘humour scrapbook’ (Figure 42-7). It is important, though, to critically examine the client’s receptivity to humour first, to ensure it is never demeaning or ill-timed.

FIGURE 42-7 Sharing a joke or laughing with clients can help reduce stress and support a therapeutic relationship.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

ENHANCING SELF-ESTEEM AND SELF-EFFICACY

Improvement in a client’s self-esteem can help in positive stress-reduction strategies. When clients identify their positive characteristics, it helps them see resources that can be drawn upon to cope with the stressor.

Self-efficacy is the personal belief that one is capable of achieving desired or required outcomes. According to Bandura (2001, 2008), the thoughts and beliefs (self-talk) that the person has about a particular circumstance or event are predictive of the outcome. Positive self-talk enables the person to rehearse a positive outcome, while negative self-talk produces stress and may become a self-fulfilling prophecy—i.e. the anticipated negative outcome will result.

Cognitive restructuring is a cognitive-based intervention that can modify stress responses. This is a technique in which the nurse and client analyse the client’s appraisals of a stressor. If these are unrealistic or focus only on negative outcomes, the client is helped to restructure the thinking to more-realistic, positive patterns (Seligman and others, 2005). This may be accomplished by encouraging the client to consider how realistic their thinking is, and challenging perceptions which are negative. For example, consider a person who is about to sit an exam whose self-talk is ‘If I fail this exam I will let my parents down’. It is likely that the person will be highly anxious, which in turn will reduce their performance. Restructuring the person’s self-talk to ‘I have prepared for the exam and will do my best’ is a more realistic and less stress-producing thought. The nurse can assist the person to restructure negative cognitions by asking: ‘How likely is the negative outcome?’, ‘What else might happen?’ or ‘If the worst does happen, what personal or other resources do you have available to respond to the challenge?’

RELAXATION TECHNIQUES

Progressive relaxation with and without muscle tension and imagery techniques reduce the physiological and emotional components of stress. Relaxation techniques are learned behaviours and require training and practice sessions. When a person is skilled in these techniques, tension is reduced and physiological parameters are changed (Box 42-6).

BOX 42-6 CHANGES RESULTING FROM PRACTISING RELAXATION TECHNIQUES

Lowered blood pressure (baseline)

Decreased cardiac dysrhythmias

Decreased oxygen demands and oxygen consumption

Increased alpha brain waves, which occur when the client is awake, non-attentive and relaxed

Examples of these techniques are guided imagery and visualisation, progressive muscle relaxation, meditation and biofeedback. In clinical practice two or more of these techniques will often be used concurrently. Cutshall and colleagues (2011) found that biofeedback and meditation was effective in helping hospital nurses to reduce stress and anxiety levels. It is important to note that relaxation techniques such as biofeedback and hypnosis should be implemented only by those caregivers who are experienced and trained to provide these services.

SPIRITUALITY

Spiritual activities can also have a positive effect in decreasing stress. Practices such as prayer, meditation or reading religious material may be meaningful resources for a client. According to Levin and Chatters (2008), religious constructs are determinants of numerous psychosocial, health and wellbeing outcomes in older adults who use religious coping in response to medical illness and disasters.

• CRITICAL THINKING

You are a nurse working in the children’s ward of a major metropolitan hospital. Danny Parker is a 7-year-old Indigenous boy from a remote community who is admitted to your ward with the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus. He is accompanied by his mother. This is the first time Danny has ever left his community, which is 500 km away.

Identify potential stressors for Danny and his mother and how they might be alleviated.

Stress management in the workplace

Work has been identified as an emerging occupational hazard, and workplace or job stress is a major contributor. According to the report of the World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, stress at work is associated with a 50% increased risk of coronary heart disease. Furthermore, high job demand, low control, and effort–reward imbalance were found to be risk factors for mental and physical health problems (World Health Organization, 2008).

Most nurses experience stress in their work environments. Stressors can include workload, shift work, institutional policies, conflict with co-workers, dealing with death or dying and loss, conflict within the multi-disciplinary team and inadequate preparation for dealing with the emotional needs of clients and families. Reaction to a job-related stressor depends on the nurse’s personality, health status, previous experiences with stress, and coping mechanisms. Nevertheless, while excessive stress can be harmful, Landa and colleagues’ (2008) study of 180 Spanish nurses found that having high levels of emotional intelligence (a personal perception of one’s ability to identify, assess and manage one’s own emotions and those of others) was protective against stress. The researchers conclude that stress effects could be moderated if healthcare professionals were given suitable training and development.

Job stress often results in a condition called burnout, which is characterised by emotional exhaustion, cynicism and a sense of professional ineffectiveness (Leiter and Maslach, 2009). Burnout may result from prolonged chronic workplace stress which is unresolved (Maslach, 2003). The job or profession no longer has positive rewards, and the person may experience anger or apathy. Pan and colleagues’ (2010) study of Chinese nurses working in an emergency department (ED) found that nurses who were exposed to violence in the ED experienced increased levels of psychological distress and were vulnerable to burnout.

According to Maslach (2003), anyone who works with needy people, and particularly healthcare workers, is at risk of burnout. Hence nurses may benefit from using the same stress-management techniques that they teach clients. Nurses should identify specific stressors at work and strive to eliminate them. It is also helpful to gain social support from other nurses to maintain a caring attitude towards clients (Hurley, 2007). In addition, clinical supervision, a professional development activity, is designed to enable reflection on practice with support from an experienced clinician with specialist training in clinical supervision. Clinical supervision outcomes include reduced stress and burnout (Hyrkäs, 2005; Hyrkäs and others, 2006).

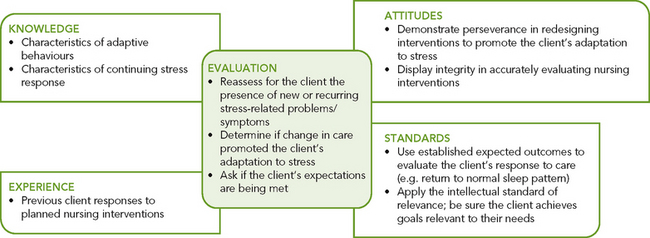

EVALUATION

Client care