Chapter 35 Sleep

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Compare the characteristics of rest and sleep.

• Explain the effect the 24-hour sleep–wake cycle has on biological function.

• Discuss mechanisms that regulate sleep.

• Describe the stages of a normal sleep cycle.

• Explain the functions of sleep.

• Compare and contrast the sleep requirements of different age groups.

• Identify factors that normally promote and disrupt sleep.

• Discuss characteristics of common sleep disorders.

• Conduct a sleep history for a client.

• Identify nursing diagnoses appropriate for clients with sleep alterations.

• Identify nursing interventions designed to promote normal sleep cycles for clients of all ages.

Rest and sleep are as important to good health as good nutrition and adequate exercise. People need different amounts of sleep and rest. Physical and emotional health depends on the ability to fulfil these basic human needs. Without proper amounts of rest and sleep, the ability to concentrate, make judgments and participate in daily activities decreases and irritability increases.

Identifying and treating clients’ sleep pattern disturbances is an important goal for nurses. To help clients, nurses need to understand the nature of sleep, the factors influencing sleep, and the clients’ sleep habits. Clients require an individualised approach based on their personal habits and patterns of sleep, as well as on the particular problem interrupting their sleep pattern. Nursing interventions can be effective in resolving short- and long-term sleep disturbances.

The essential and unavoidable nature of sleep points to an evolutionary and adaptive role, although other theories of sleep suggest it has major roles in development, healing and restoration, as well as memory consolidation (Craft and others, 2011). Achieving the best possible sleep quality is important for the promotion of good health as well as the recovery from illness. Nurses care for clients who often have pre-existing sleep disturbances and for clients who develop sleep problems as a result of illness or hospitalisation. Sometimes people seek healthcare because they have a sleep problem that may have gone unnoticed for many years. Ill people often require more sleep and rest than healthy people. However, the nature of illness may prevent people from gaining adequate rest and sleep. The institutional environment of a hospital or long-term-care facility and the activities of healthcare personnel make sleep difficult.

Scientific knowledge base

Physiology of sleep

Sleep is a cyclical physiological process that alternates with longer periods of wakefulness. The sleep–wake cycle influences and regulates physiological function and behavioural responses.

Circadian rhythms

People experience cyclical rhythms as part of their everyday life. The most familiar rhythm is the 24-hour day–night cycle known as the diurnal or circadian rhythm (derived from Latin: circa, ‘about’, and dies, ‘day’) The fluctuation and predictability of body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, hormone secretion, sensory acuity and mood depend on the maintenance of the 24-hour circadian cycle.

Circadian rhythms, including daily sleep–wake cycles, are affected by light and temperature and external factors such as social activities and work routines. All people have biological clocks that synchronise their sleep cycles. Sleeping patterns vary and people function best at different times of the day. Taillard and others (2001) described two groups of people: morning ‘larks’ and evening ‘owls’. The morning person prefers to go to bed early and get up early, performing best in the morning. The evening person prefers to go to bed late and get up late, functioning best in the evenings.

Hospitals or extended-care facilities usually do not adapt care to an individual’s sleep–wake cycle preferences. Nursing care based on routines or ritual can cause interruptions in sleep or prevent clients from falling asleep at their usual time. For example, a recent descriptive-exploratory study of bed-bathing practices among registered nurses (RNs) working in four Australian metropolitan intensive-care units (ICUs) found that 30% of bed baths were given between 2.00 and 6.00 a.m., with ‘freshen up’ washes often given at 6.00 a.m. (Coyer and others, 2011). Focus groups revealed that RNs with less than 5 years experience fell into line with the established routines of the ICU, whereas more-experienced RNs had firmly established beliefs about the bed-bath and upheld the practice of their workplace.

If a person’s sleep–wake cycle is altered significantly, a poor quality of sleep can result. Reversals in the sleep–wake cycle, such as falling asleep during the day, can indicate a serious illness. Anxiety, restlessness, irritability and impaired judgment are common symptoms of disturbances in the sleep cycle (Cable, 2005).

The biological rhythm of sleep often becomes synchronised with other body functions. Changes in body temperature, for example, correlate with sleep patterns. Normally, body temperature peaks in the afternoon, decreases gradually and then drops sharply after a person falls asleep. When the sleep–wake cycle is disrupted, other physiological functions may change as well. For example, the person may experience a decreased appetite and lose weight. Failure to maintain the usual sleep–wake cycle can adversely affect a person’s overall health.

Sleep regulation

Sleep involves a sequence of physiological states maintained by highly integrated central nervous system (CNS) activity that is associated with changes in the peripheral nervous, endocrine, cardiovascular, respiratory and muscular systems (McCance and Huether, 2006). Each sequence can be identified by specific physiological responses and patterns of brain activity. Instruments such as the electroencephalogram (EEG), which measures electrical activity in the cerebral cortex, the electromyogram (EMG), which measures muscle tone, and the electro-oculogram (EOG), which measures eye movements, provide information about some structural physiological aspects of sleep.

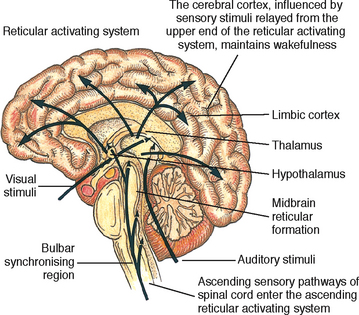

Current theory indicates that sleep is thought to be an active inhibitory process (Guyton and Hall, 2010). The reticular activating system (RAS) is located in the upper brain stem and is responsible for maintaining alertness and wakefulness. The RAS receives visual, auditory, pain and tactile sensory stimuli. Activity from the cerebral cortex (e.g. emotions or thought processes) also stimulates the RAS. Arousal or wakefulness results from activation of the cerebral cortex from sensory input and ascending activation via the RAS (Thibodeau and Patton, 2010)

Sleep may be produced by the release of serotonin from specialised cells in the raphe sleep system of the pons and medulla. This area of the brain is also called the bulbar synchronising region (BSR). Whether a person remains awake or falls asleep depends on a balance of impulses received from higher centres (e.g. thoughts), peripheral sensory receptors (e.g. sound or light stimuli) and the limbic system (e.g. emotions) (Figure 35-1).

FIGURE 35-1 The reticular activating system (RAS) and bulbar synchronising region (BSR) control sensory input, intermittently activating and suppressing the brain’s higher centres to control sleep and wakefulness.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

As people try to fall asleep, they close their eyes and assume relaxed positions. Stimuli to the RAS decline. If the room is dark and quiet, activation of the RAS further declines. At some point the BSR takes over, causing sleep.

Stages of sleep

According to Guyton and Hall (2010), EEG, EMG and EOG electrical signals show that different levels of brain, muscle and eye activity are associated with different stages of sleep. Normal sleep involves two phases: non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (Box 35-1). During NREM, sleep progresses through four stages over a typical 90-minute sleep cycle. The quality of sleep from stage 1 to stage 4 becomes increasingly deep. Lighter sleep is characteristic of stages 1 and 2, and a person is more easily woken. Stages 3 and 4 involve a deeper sleep, called slow-wave sleep, from which it is more difficult to rouse a person. REM sleep is the phase at the end of each 90-minute sleep cycle.

STAGE 4: NREM SLEEP

REM SLEEP

• Vivid, full-colour dreaming may occur.

• Less vivid dreaming may occur in other stages.

• Stage usually begins about 90 minutes after sleep has begun.

• Typified by autonomic response of rapidly moving eyes, fluctuating heart and respiratory rates and increased or fluctuating blood pressure.

• Loss of skeletal muscle tone occurs.

• Gastric secretions increase.

• Very difficult to arouse sleeper.

• Duration of REM sleep increases with each cycle and averages 20 minutes.

NREM = non-rapid eye movement; REM = rapid eye movement.

Sleep cycle

Normally, in an adult the routine sleep pattern begins with a pre-sleep period during which the person is aware only of a gradually developing sleepiness. This period normally lasts 10–30 minutes, but if a person has difficulty falling asleep, it may last an hour or more.

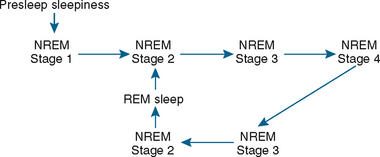

Once asleep, the person usually passes through 4–6 complete sleep cycles per night, each consisting of four stages of NREM sleep and a period of REM sleep (McCance and Huether, 2006). The cyclical pattern usually progresses from stage 1 to stage 4 of NREM, followed by a reversal from stages 4 to 3 to 2 and ending with a period of REM sleep (Figure 35-2). A person usually reaches REM sleep about 90 minutes into the sleep cycle.

FIGURE 35-2 The stages of the adult sleep cycle.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

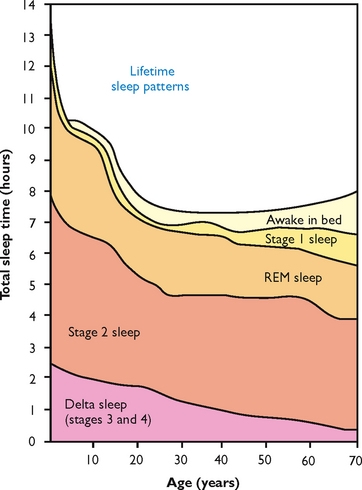

With each successive cycle, stages 3 and 4 shorten and the period of REM lengthens. REM sleep may last up to 60 minutes during the last sleep cycle. Not all people progress consistently through the usual stages of sleep. For example, a sleeper may fluctuate for short intervals between NREM stages 2, 3 and 4 before entering the REM stage. The amount of time spent in each stage varies over the life span (see Figure 35-3). The number of sleep cycles depends on the total amount of time the person spends sleeping.

Functions of sleep

Sleep is believed to contribute to physiological and psychological restoration (McCance and Huether, 2006). According to one theory, sleep is a time of restoration and preparation for the next period of wakefulness. During NREM sleep, biological functions slow. A healthy adult’s normal heart rate throughout the day averages 70–80 beats per minute, or less if the person is in excellent physical condition. However, during sleep the heart rate falls to 60 beats per minute or less. Clearly, restful sleep may be beneficial in preserving cardiac function. Other biological functions that decrease during sleep are respirations, blood pressure and muscle tone (McCance and Huether, 2006).

Sleep appears to be needed to routinely restore biological processes. During deep slow-wave (NREM stage 4) sleep, the body releases human growth hormone for the repair and renewal of epithelial and specialised cells such as brain cells (McCance and Huether, 2006). Another theory about the purpose of sleep is that the body conserves energy during sleep. The skeletal muscles relax progressively, and the absence of muscular contraction preserves chemical energy for cellular processes. Lowering of the basal metabolic rate further conserves the body’s energy supply.

REM sleep appears to be important for cognitive restoration. REM sleep is associated with changes in cerebral blood flow, increased cortical activity, increased oxygen consumption, and adrenaline release. This association may help with memory storage and learning. During sleep, the brain filters stored information about the day’s activities.

The beneficial effects of sleep on behaviour often go unnoticed until a person develops a problem resulting from sleep deprivation. A loss of REM sleep can affect functioning of the CNS, with impacts on thought and behaviour (Guyton and Hall, 2010). Some industrial accidents, such as the 1986 nuclear accident in Chernobyl, have been attributed to human error associated with sleep deprivation. Traffic, home and work-related accidents caused by falling asleep cost millions of dollars a year—driving licence authorities in each state of Australia require notification of any medical conditions that may affect driving before licences are issued, including conditions that cause sleepiness.

Dreams

Although dreams occur during both NREM and REM sleep, the dreams of REM sleep are more vivid and elaborate and are believed to be functionally important to the consolidation of long-term memory. REM dreams may progress in content throughout the night from dreams about current events to emotional dreams of childhood or the past. Personality can influence the quality of dreams. For example, a creative person may have creative dreams, whereas a depressed person may dream of helplessness.

Most people dream about immediate concerns such as an argument with a spouse, plans for a wedding or worries over work. Sometimes a person is unaware of fears represented in bizarre dreams. The ability to describe a dream and interpret its significance may help resolve personal concerns or fears.

Another theory suggests that dreams erase certain fantasies or nonsensical memories. Since most dreams are forgotten, many people have little dream recall and do not believe they dream at all. To remember a dream, a person must consciously think about it on waking. People who recall dreams vividly usually wake just after a period of REM sleep.

Physical illness

Any illness that causes pain, physical discomfort (e.g. difficulty breathing) or mood problems (e.g. anxiety or depression) can result in sleep problems. People with such alterations may have trouble falling or staying asleep. Illnesses also may force people to sleep in positions to which they are unaccustomed. For example, assuming an awkward position when an arm or leg has been immobilised in traction can interfere with sleep.

Respiratory disease often interferes with sleep. Clients with chronic lung disease such as emphysema are short of breath and frequently cannot sleep without two or three pillows to raise their heads. Asthma, bronchitis and allergic rhinitis alter the rhythm of breathing and disturb sleep. A person with a common cold has nasal congestion, sinus drainage and a sore throat, which impair breathing and the ability to relax.

Coronary artery disease often is characterised by episodes of sudden chest pain and irregular heart rates. McCance and Huether (2006) attribute an increase in these symptoms in the early-morning hours to dreams and the cardiovascular stress occurring in REM sleep. Hypertension often causes early-morning waking and fatigue. Hypothyroidism decreases stage 4 sleep, whereas hyperthyroidism causes people to take more time to fall asleep.

Nocturia, urination during the night, disrupts sleep and the sleep cycle. This condition is most common in older adults with reduced bladder tone or people with cardiac disease, diabetes or prostatic disease. After a person wakes repeatedly to urinate, returning to sleep may be difficult.

Older adults often experience restless legs syndrome (RLS), which occurs before sleep onset. People experience recurrent, rhythmical movements of the feet and legs. An itching sensation is felt deep in the muscles. Relief comes only from moving the legs, which prevents relaxation and subsequent sleep. Depending on how severely sleep is disrupted, RLS may be a relatively benign condition. RLS has been found to be associated with lower levels of iron, amongst other clinical comorbidities (Lewis and others, 2011). In contrast, people who have severe leg cramps during the night may have a problem with arterial circulation or spasticity from neurological problems.

Sleep disorders

Sleep disorders are conditions that, if untreated, generally cause disturbed night-time sleep. Many adults in Australia have significant sleep debt from inadequacies in either the quantity or the quality of their night-time sleep, and experience hypersomnolence (excessive sleepiness) on a daily basis (Box 35-2). The dyssomnias are primary disorders that have their origin in different body systems and are subdivided into three major groups. Intrinsic sleep disorders include disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep, i.e. various forms of insomnia, and disorders of excessive sleepiness such as narcolepsy and obstructive sleep apnoea. Extrinsic sleep disorders develop from external factors which, if removed, lead to resolution of the sleep disorder. Circadian rhythm sleep disorders arise from a misalignment between the timing of sleep and what is desired by the individual or as a societal norm. The parasomnias are undesirable behaviours that occur predominantly during sleep: arousal disorders, partial arousals or disorders during transitions in the sleep cycle or from sleep to wakefulness. Many medical and psychiatric sleep disorders are associated with sleep and wake disturbances. These sleep disturbances are divided into those associated with psychiatric, neurological or other medical specialty disorders. The proposed sleep disorders are newly described disturbances for which inadequate information currently exists to substantiate their existence.

BOX 35-2 Classification of sleep disorders

PROPOSED SLEEP DISORDERS

Menstruation-associated sleep disorders

Modified from American Sleep Disorders Association 1990 The international classification of sleep disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. Rochester, Allen Press.

Sleep laboratory studies such as a night-time polysomnogram (PSG) and the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) are often used to diagnose a sleep disorder. A polysomnogram involves the use of EEG, EMG and EOG to monitor stages of sleep and wakefulness during night-time sleep. The MSLT provides objective information about sleepiness and selected aspects of sleep structure by measuring how rapidly individuals fall asleep during at least four napping opportunities spread throughout the day. Sleep-onset REM episodes are also noted, since this abnormality is associated with several sleep disorders.

Insomnia

The American Society of Sleep Medicine defines insomnia as ‘unsatisfactory sleep that impacts on daytime functioning’ (Ramakrishnan and Scheid, 2007). The insomniac complains of excessive daytime sleepiness as well as insufficient quantity and quality of sleep. Often, however, the client gets more sleep than is realised. Insomnia may signal an underlying physical or psychological disorder. Insomnia is perceived more frequently in women (McCance and Huether, 2006).

People may experience transient insomnia as a result of situational stresses such as family, work or school problems, jet lag, illness, or loss of a loved one. Insomnia may recur, but between episodes the person is able to sleep well. However, a temporary case of insomnia due to a stressful situation can lead to chronic difficulty in getting sufficient sleep, perhaps due to the worry and anxiety that develops about getting adequate sleep.

Insomnia is often associated with poor sleep hygiene habits and practices the client uses that are associated with sleep. If the condition continues, the fear of not being able to sleep can be enough to cause wakefulness. During the day, people with chronic insomnia may feel sleepy, fatigued, depressed and anxious.

Because there are many causes of insomnia, management involves several approaches (Ramakrishnan and Scheid, 2007). As appropriate, it is important to treat underlying emotional or medical problems that may be causing the night-time sleep problem. Treatment can also be symptomatic, including improved sleep hygiene measures, biofeedback, cognitive techniques and relaxation techniques. When insomnia develops secondary to inappropriate health behaviours, treatment is directed at changing these behaviours. For example, in drug-dependence insomnia, the person is unable to fall asleep because of excessive use of hypnotic medications. Such a person usually benefits from a gradual withdrawal of the hypnotics.

Sleep apnoea

Sleep apnoea is a disorder characterised by partial or complete upper-airway obstruction causing apnoea for periods of 10 seconds or longer during sleep. There are three types of sleep apnoea: central, obstructive and mixed apnoea, which has both a central and an obstructive component (Berry and others, 2008).

The most common form, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), occurs when muscles or structures of the oral cavity or throat relax during sleep. The upper airway becomes partially or completely blocked, and nasal airflow is diminished (hypopnoea) or stopped (apnoea) for as long as 30 seconds (McCance and Huether, 2006). The person still attempts to breathe because chest and abdominal movement continues, which often results in loud snoring and snorting sounds. When breathing is partially or completely diminished, each successive diaphragmatic movement becomes stronger until the obstruction is relieved. Structural abnormalities such as a deviated septum, nasal polyps, certain jaw configurations or enlarged tonsils predispose a client to obstructive apnoea. The effort to breathe during sleep results in arousals from deep sleep, often to the stage 2 cycle. In serious cases, hundreds of hypopnoea/apnoea episodes can occur every hour, resulting in severe interference with deep sleep.

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is the most common complaint of people with OSA. Those with severe OSA may report taking daytime naps and experiencing a disruption in their daily activities because of sleepiness. Sleep apnoea is a common disorder affecting up to 4% of the population (McCance and Huether, 2006).

OSA causes a serious decline in arterial oxygen level. People are at risk of cardiac dysrhythmia, right heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, anginal attacks, stroke and hypertension. Middle-aged men are usually thought to be more frequently affected. Obesity hypotension syndrome is associated with impaired respiratory mechanics and depressed respiratory control during sleep and with severe morbidity and high mortality (McCance and Huether, 2006).

Central sleep apnoea (CSA) involves dysfunction in the brain’s respiratory control centre. The impulse to breathe temporarily fails, and nasal airflow and chest wall movement cease. The oxygen saturation of the blood falls. The condition is seen in people with brainstem injury, muscular dystrophy and encephalitis and people who breathe normally during the day. Less than 10% of sleep apnoea is predominantly central in origin. People with CSA tend to wake during sleep and therefore complain of insomnia and EDS. Mild and intermittent snoring is also present.

The client with sleep apnoea is often significantly deprived of deep sleep. In addition to complaints of EDS, sleep attacks, fatigue, car accidents and poor work performance are common (McCance and Huether, 2006). In most states in Australia, people who have sleep disorders require medical clearance (i.e. to state that they are responding well to treatment) to retain a driver’s licence (VicRoads, 2012). Treatment includes therapy for underlying cardiac or respiratory complications and emotional problems that arise as a result of the symptoms of this disorder. Management usually begins with lifestyle changes and a weight-loss program. One of the most effective therapies is use of a nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device at night, which requires the client to wear a mask over the nose. Room air is delivered through the mask at a high pressure. The air pressure prevents upper-airway collapse and therefore prevents periods of apnoea. The CPAP device is portable and particularly effective for obstructive apnoea. In cases of severe sleep apnoea, the tonsils, uvula or portions of the soft palate may be surgically removed. However, the majority of patients do not need surgery and CPAP plays a key role in their management.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is a dysfunction of mechanisms that regulate the sleep and wake states. EDS is the most common complaint associated with this disorder. During the day a person may suddenly feel an overwhelming wave of sleepiness and fall asleep. REM sleep can occur within 15 minutes of falling asleep. Cataplexy, or sudden muscle weakness during intense emotions such as anger, sadness or laughter, may occur at any time during the day. If the cataplectic attack is severe, the client may lose voluntary muscle control and fall to the floor. A person with narcolepsy may have dreams that occur as the person is falling asleep and are difficult to distinguish from reality (called hypnagogic hallucinations). Sleep paralysis, or the feeling of being unable to move or talk just before waking or falling asleep, is another symptom of narcolepsy. Some studies suggest a genetic link for narcolepsy (Dauvilliers and others, 2007).

A significant problem for the person with narcolepsy is that the person falls asleep uncontrollably at inappropriate times. Unless this disorder is understood, a sleep attack can easily be mistaken for laziness, lack of interest in activities, or drunkenness. Typically, the symptoms first begin to arise in adolescence and may be confused with the EDS that is thought to commonly occur in teens. Narcoleptics are treated with stimulants that may only partially increase wakefulness and reduce sleep attacks, and medications that suppress cataplexy and the other REM-related symptoms. Brief daytime naps no longer than 20 minutes may help reduce subjective feelings of sleepiness. Factors that increase a narcoleptic’s drowsiness should be avoided (e.g. alcohol, heavy meals, exhausting activities, long-distance driving, long periods of sitting, hot stuffy rooms).

Sleep deprivation

Sleep deprivation is a problem many people experience as a result of a dyssomnia. Causes may include illness (e.g. fever, difficulty breathing, pain), emotional stress, medications, environmental disturbances (e.g. frequent nursing care) and variability in the timing of sleep due to shift work. Healthcare workers may be particularly prone to sleep deprivation due to long work schedules and rotating shifts.

Hospitalisation, especially in ICUs, makes clients particularly vulnerable to the extrinsic and circadian sleep disorders (Dines-Kalinowski, 2002). Sleep deprivation involves decreases in the quantity and quality of sleep and inconsistency in the timing of sleep. When sleep becomes interrupted or fragmented, changes in the normal sequencing of the sleep cycles occur. A cumulative sleep deprivation can develop even in patients who are sedated.

People’s responses to sleep deprivation are highly variable. Clients may experience a variety of physiological and psychological symptoms (Box 35-3). The severity of symptoms is often related to the duration of sleep deprivation. The most effective treatment for sleep deprivation is elimination or correction of factors that disrupt the sleep pattern. Nurses can play an important role in identifying treatable sleep deprivation problems.

Parasomnias

The parasomnias are sleep problems that are more common in children than in adults. Sudden infant death syndrome is, according to McCance and Huether (2006), caused by a number of external and internal predisposing factors, such as apnoea, hypoxia and cardiac arrhythmias related to abnormalities in the autonomic nervous system, and manifest during sleep.

Parasomnias that occur among older children include somnambulism (sleepwalking), night terrors, nightmares, nocturnal enuresis (bed-wetting) and teeth grinding (bruxism) (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009). When adults have these problems, it may indicate more-serious disorders. Specific treatment for these disorders varies. However, in all cases it is important to support clients and maintain their safety. For example, sleepwalkers are unaware of their surroundings and are slow to react, so the risk of falls is great. A nurse should not startle sleepwalkers, but instead gently wake them and lead them back to bed.

Nursing knowledge base

Sleep and rest

When people are at rest they usually feel mentally relaxed, free from anxiety and are physically calm. Rest does not imply inactivity, although people often think of it as settling down in a comfortable chair or lying in bed. When people are at rest they are in a physical and mental state that leaves them feeling refreshed, rejuvenated and ready to resume the activities of the day. All people have their own habits for obtaining rest and can find ways to adjust as well as possible to new environments or conditions that affect the ability to rest. Rest may be gained from reading a book, practising a relaxation exercise, listening to music, taking a long walk or sitting quietly.

Nurses often care for clients on bed rest in a variety of healthcare settings. This treatment confines clients to bed to reduce physical and psychological demands on the body. Such people do not necessarily feel rested. They may still have emotional worries that prevent complete relaxation. For example, concern over physical limitations or a fear of being unable to return to their usual lifestyle may cause such clients to feel stressed and unable to relax.

The usual rest and sleep patterns of people entering a hospital or other healthcare facility can easily be affected by illness or unfamiliar healthcare routines. The extent of change in usual sleep and rest patterns depends on the client’s physiological and psychological states and the physical environment, such as background noise and the work patterns of caregivers. Some critical-care and acute care settings have introduced policies to restrict visiting and allow rest periods for patients in the afternoon to improve sleep. A recent Australian study investigating the effectiveness of a scheduled quiet time intervention in acute wards found it reduced perceived noise by half, and patients were more than twice as likely to be asleep during the quiet-time period compared with patients in the control ward (Gardner and others, 2009).

Normal sleep requirements and patterns

Neonates

The neonate up to the age of 3 months averages about 16 hours of sleep a day. The neonate experiences both REM and non-REM sleep, predominantly with a transitional phase between (McCance and Huether, 2006). The infant born of an unmedicated mother enters the world in a state of wakefulness. Eyes are wide open and sucking is vigorous. After about an hour the newborn becomes quiet and less responsive to internal and external stimuli. A period of sleep lasting from a few minutes up to 2–4 hours follows (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009). The infant then wakes and often becomes overly responsive to stimuli. Hunger, pain, cold or other stimuli often cause crying. For the first week, the neonate sleeps almost constantly. Approximately 50% of this sleep is REM sleep, which stimulates the higher brain centres. This is thought to be essential for development because the neonate is not awake long enough for significant external stimulation.

Infants

Infants usually develop a night-time pattern of sleep by 3 months of age. The infant may take several naps during the day but usually sleeps an average of 9–11 hours during the night for a total daily sleep time of 15 hours. About 30% of sleep time is spent in the REM cycle. Awakening commonly occurs early in the morning, although it is not unusual for an infant to wake during the night. If waking during the night becomes routine, the problem may be with diet because hunger frequently wakes a child. A breastfed infant usually sleeps for shorter periods, with more frequent awakenings, than a bottle-fed infant (McCance and Huether, 2006). A large infant sleeps longer than a smaller one because of greater stomach capacity. Compared with older children, active (REM) sleep makes up a larger proportion of sleep. In contrast with newborns, in whom sleep and wakefulness alternate throughout a 24-hour period, by 3 months of age the longest sleep period is at night.

Toddlers

By the age of 2 years, children usually sleep through the night and take daily naps. Total sleep averages 12 hours a day. Children over 3 years of age often give up daytime naps (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009). It is common for toddlers to wake during the night. The percentage of REM sleep continues to fall. During this period the toddler may be unwilling to go to bed at night. This unwillingness may be due to a need for autonomy or a fear of separation from parents. Toddlers have a need to explore and satisfy their curiosity, which may explain why some of them try to delay bedtime.

Preschoolers

On average, a preschooler sleeps about 12 hours a night (about 20% is REM). By the age of 5 years, the preschooler rarely takes daytime naps (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009). The preschooler usually has difficulty relaxing or quietening down after long, active days. A preschooler also has problems with bedtime fears, waking during the night, or nightmares. Parents are most successful in getting a preschooler to bed by establishing a consistent ritual that includes some quiet activity before bedtime. Ordinarily, experts do not recommend that a child be allowed to sleep with parents. However, in some cultures sharing a bed or room with parents is an accepted sleeping practice. Difficulty going to sleep after an active day, bedtime fears, waking up, nightmares or sleep terrors may appear in this age group (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009).

School-age children

The amount of sleep needed during the school years is individualised because of varying states of activity and levels of health (see Working with diversity). The school-age child enters a wakeful time in life and usually does not require a nap. Sleep times are highly individualised, depending on activity levels, growth, age and the state of health. The 6- or 7-year-old can usually be persuaded to go to bed by encouraging quiet activities. The older child often resists sleeping because of unawareness of fatigue or a need to be independent. Nocturnal bedwetting can continue in this age group until about 8 years of age (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009).

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON CHILDREN

Adenotonsillar disease has been considered to be a normal part of growth and development in children. Recent research has indicated that children with recurrent tonsillitis have impaired quality of life. Compared with healthy children, 11 measures of quality of life including global health, general health perception, bodily pain and discomfort and sleep duration were depressed in the cohort study. Along with the strict guidelines now used for removal of tonsils in children, surgeons will need to assess quality of life.

Nelson R 2002 Adenotonsillar disease has a detrimental effect on children’s quality of life. Lancet 360(9338):1002.

Adolescents

Teens vary in their need for sleep. At a time when sleep needs actually increase, the typical adolescent is subject to a number of changes that often reduce the time spent sleeping (Dahl and Carskadon, 1995). School demands, after-school social activities and part-time jobs may result in compressed time available for sleep. Teens often go to bed later and rise earlier during the secondary-school years. A common societal expectation is that adolescents require less sleep than preadolescents. However, laboratory data indicate that adolescents may have a physiological need for more sleep when compared with preadolescents (Dahl and Carskadon, 1995). Because of lifestyle demands that shorten the time available for sleep and probable physiological need, teens often experience EDS. Performance in school, vulnerability to accidents, and behaviour and mood problems can be the result of EDS due to insufficient sleep. Parents, teachers and teens themselves often lack knowledge about what is adequate sleep, and may need education to improve what can be a significant health problem for teens.

Young adults

Most young adults average 6–8½ hours of sleep a night, but this can vary. Young adults rarely take regular naps. Approximately 20% of sleep time is spent in REM sleep, which remains consistent throughout life. Healthy young adults require adequate sleep to participate in all their daily activities. However, it is common for lifestyle demands to interrupt usual sleep patterns. The stresses of jobs, family relationships and social activities may lead to insomnia (i.e. difficulties initiating and/or maintaining sleep) and the use of medication for sleep. Long-term use of such medications can disrupt sleep patterns and make the insomnia problem worse. Daytime sleepiness contributes to an increased number of accidents, decreased productivity and interpersonal problems in this age group. Full-time employment and single marital status are the most common risk factors for sleep problems in this age group (Breslau and others, 1997). Pregnancy increases the need for sleep and rest. Insomnia is a common problem during the third trimester of pregnancy (London and others, 2003).

Middle-aged adults

During middle adulthood the total time spent sleeping at night begins to decline. The amount of stage 4 sleep begins to fall, a decline that continues with advancing age. Sleep disturbances are often initially diagnosed among people in this age group even when the symptoms of a disorder have been present for several years. Insomnia is particularly common, probably because of the changes and stresses of middle age. Sleep disturbances can be caused by anxiety, depression or certain physical ailments. Women experiencing menopausal symptoms may have insomnia.

Older adults

The total amount of sleep decreases and the quality of sleep appears to deteriorate for many older adults (McCance and Huether, 2006). Episodes of REM sleep tend to shorten. There is a progressive decrease in stages 3 and 4 NREM sleep, and some older adults have almost no stage 4, or deep sleep, at all. Older adults often wake earlier and fall asleep during the daytime, which is thought to affect the quality of their night-time sleep (Ebersole and others, 2004).

Variability in the sleep behaviours of older adults is common. The changes in an older person’s sleep pattern may be due to changes in the CNS that affect the regulation of sleep. Sensory impairment, which is common with ageing, may also reduce an older person’s sensitivity to time cues that maintain circadian rhythms.

Factors affecting sleep

A number of factors affect the quantity and quality of sleep. Often a single factor may not be the only cause of a sleep problem. Physiological, psychological and environmental factors can alter the quality and quantity of sleep.

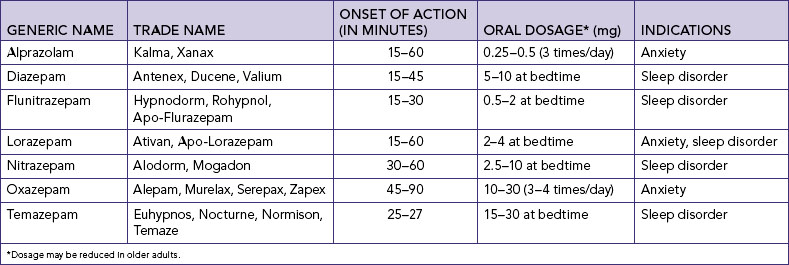

Drugs and substances

Sleepiness and sleep deprivation are common side effects of commonly prescribed medications (Box 35-4). These medications alter sleep and impair daytime alertness (Bryant and others, 2010). Medications prescribed for sleep may cause more problems than benefits. Older adults often take a variety of drugs to control or treat chronic illness, and the combined effects of several drugs can seriously disrupt sleep.

Lifestyle

A person’s daily routine may influence sleep patterns. A person working a rotating shift (e.g. 2 weeks of days followed by a week of nights) often has difficulty adjusting to the altered sleep schedule. The body’s internal clock might be set at 11 p.m., but the work schedule forces sleep at 9 a.m. instead. The person may be able to sleep only 3 or 4 hours because the body’s clock perceives that it is time to be awake and active. Difficulties with maintaining alertness during work time can result in decreased and even hazardous performance. After several weeks of working a night shift, a person’s biological clock usually does adjust. Other alterations in routine that can disrupt sleep patterns include performing unaccustomed heavy work, engaging in late-night social activities and changing evening mealtimes.

Usual sleep patterns and excessive daytime sleepiness

Excessive daytime sleepiness often results in impairment of waking function, poor work or school performance, accidents while driving or using equipment, and behavioural or emotional problems. Feelings of sleepiness are usually most intense on waking from sleep, or just before going to sleep, and about 12 hours after the mid-sleep period.

Sleepiness becomes pathological when it occurs at times when people need or want to be awake. People who experience temporary sleep deprivation as a result of an active social evening or lengthened work schedule usually feel sleepy the next day. However, they may be able to overcome these feelings even though they have difficulty performing tasks and remaining attentive. Chronic lack of sleep is much more serious than temporary sleep deprivation, and can cause serious alterations in the ability to perform daily functions. EDS tends to be most difficult to overcome during sedentary tasks.

Emotional stress

Worry over personal problems or situations can disrupt sleep. Emotional stress causes a person to be tense and often leads to frustration when sleep does not come. Stress may also cause a person to try too hard to fall asleep, to wake frequently during the sleep cycle or to oversleep. Continued stress may cause poor sleep habits.

Environment

The physical environment in which a person sleeps has a significant influence on the ability to fall asleep and remain asleep. Good ventilation is essential for restful sleep. The size, firmness and position of the bed can affect the quality of sleep. Hospital beds are often smaller and harder than those at home. If a person usually sleeps with another individual, sleeping alone can cause wakefulness. On the other hand, sleeping with a restless or snoring bed partner can also disrupt sleep.

Sound also influences sleep. The level of noise needed to wake people depends on the stage of sleep. Low noises are more likely to arouse a person from stage 1 sleep, whereas louder noises wake people in stage 3 or 4 sleep. Some people require silence to fall asleep, whereas others prefer background noise such as soft music or television.

In hospitals and other inpatient facilities, noise creates a problem for clients. Noise in hospitals is usually new or strange, so clients are prone to waking up. This problem is greatest the first night of hospitalisation, when clients often experience increased total wake time, increased awakenings and decreased REM sleep and total sleep time. The level of noise in hospitals can be very high. Normal conversation measures about 50 decibels. Sound becomes noise at 35–40 decibels. People-caused noises (e.g. nursing activities) are sources of increased sound levels. ICUs have high noise levels. Close proximity of clients, noise from confused and ill clients, the ringing of alarm systems and telephones, and disturbances caused by emergencies make the environment unpleasant. Noise is related to subjective quality of sleep.

Light levels may affect the ability to fall asleep. Some people may prefer a dark room, whereas others, such as children or older adults, may prefer keeping a soft light on during sleep. People may have trouble sleeping because of the temperature of a room—a room that is too warm or too cold often causes restlessness.

Exercise and fatigue

A person who is moderately fatigued usually achieves restful sleep, especially if the fatigue is the result of enjoyable work or exercise. Exercise should be completed 2 hours or more before bedtime to allow the body to relax and cool down and maintain a state of fatigue. However, excess fatigue resulting from exhausting or stressful work can make falling asleep difficult. This can be a common problem for primary-school children and adolescents.

Food and kilojoule intake

People sleep better when they are healthy, so following good eating habits is important for proper health and sleep (Hauri and Linde, 1996). Eating a large, heavy and/or spicy meal at night may result in indigestion that interferes with sleep. Caffeine and alcohol consumed in the evening have insomnia-producing effects. A drastic reduction or avoidance of these substances is an important strategy that people can use to improve sleep.

Food allergies may cause insomnia. In infants, night-time waking and crying or colic may be caused by a milk allergy, requiring that breast milk or a non-milk formula be used. Besides milk, some foods that often result in an insomnia-producing allergy among both children and adults include corn, wheat, nuts, chocolate, eggs, seafood, red and yellow food dyes and yeast (Hauri and Linde, 1996). Restoration of normal sleep may take up to 2 weeks when the particular food that is causing the difficulty has been eliminated from the diet.

Weight loss or gain influences sleep patterns. When a person gains weight, sleep periods become longer with fewer interruptions. Weight loss can cause short and fragmented sleep. Certain sleep disorders may be the result of the semi-starvation diets popular in a weight-conscious society. Conversely, some research suggests that sleeping problems may contribute to the development of weight gain (Knutson, 2007).

Critical thinking synthesis

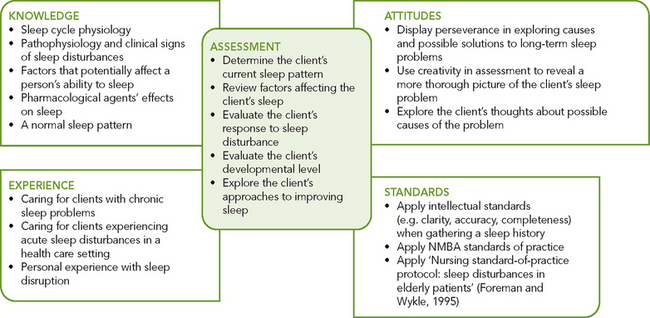

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from clients, critical-thinking attitudes and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require the nurse to anticipate the information necessary, analyse the data and make decisions regarding client care. Critical thinking is always changing. During assessment (Figure 35-4), the nurse must consider all elements that build towards making appropriate nursing diagnoses.

In the case of sleep, the nurse integrates knowledge from nursing and other disciplines, previous experiences, and information gathered from clients to understand the client’s sleep problem and its effect on the client and family. In addition, the use of critical-thinking attitudes such as perseverance, confidence and discipline are needed to find a plan of care to provide successful management of the sleep problem.

Dudley is a 54-year-old truck driver who presents after a recent driving accident at work which he attributes to difficulty with concentrating and excessive daytime sleepiness. Dudley’s wife also convinced him to discuss his sleeping problems. She is always complaining about his loud snoring, and sleeps in a separate room at night. On assessment Dudley is centrally obese with a body mass index (BMI) of 39. He is a non-smoker and drinks about a 6-pack of beer per night.

• CRITICAL THINKING

1. What kind of sleep disorder does Dudley most probably have? What are the implications for his health if it is left untreated?

2. In undertaking a focused sleep assessment, what other assessment data not given in the clinical example above would you want to collect? How would you assess these data—that is, what questions would you ask or what physical assessment would you conduct?

NURSING PROCESS

ASSESSMENT

To promote a normal restful sleep for clients, the nurse assesses their sleep patterns using the nursing history to gather information about factors that usually influence sleep. If the client perceives that sleep is adequate, the nursing history can be brief.

Sleep is a subjective experience. Only the client can report whether it is sufficient and restful. If the client is satisfied with the quantity and quality of sleep received, it may be considered normal. If a client identifies a sleep problem or the nurse suspects it, a more detailed history is needed (Figure 35-4).

Sleep assessment

Most people can provide a reasonably accurate estimate of their sleep patterns, particularly if any changes have occurred. Assessment is aimed at understanding the characteristics of any sleep problem and the client’s usual sleep habits, so that ways of promoting sleep can be incorporated into nursing care. For example, if the nursing history reveals that a client always reads before falling asleep, it makes sense to offer reading material at bedtime.

SOURCES OF SLEEP ASSESSMENT

Usually clients are the best resource for describing a sleep problem and the extent to which a problem represents a change from their usual sleep and waking patterns. It is important to note that age affects the time and requirements for sleeping. For example, in young adolescents it has been found that they sleep 1.5 hours per day less than that recommended by the National Sleep Foundation (Teufel and others, 2007) (see Research highlight).

Often the client knows the cause of sleep problems, such as a noisy environment or worry over a relationship. Additionally, bed partners can provide information on the client’s patterns that may reveal the nature of certain sleep disorders. For example, partners of clients with sleep apnoea often complain that their sleep is disturbed by the client’s snoring. Often the partners must sleep in different beds or rooms to obtain adequate sleep. Nurses should ask bed partners whether the clients have pauses of breathing during sleep and how frequently the apnoeic attacks occur. Some partners mention becoming fearful when clients apparently stop breathing for periods during sleep.

Research focus

Sleep is considered to be physically and psychologically restorative and essential for healing and recovery from illness. The critically ill are in significant need of sleep but at an increased risk of sleep deprivation. Intensive care units (ICUs) provide treatment to critically ill patients which involves intrusive and invasive monitoring and treatments. These, together with the manifestations of illness and the noisy environment, may lead to discomfort, including loss of sleep.

Research abstract

The objective of this literature review was to primarily determine what is already known about the sleep experiences of patients in ICUs and about the quality and duration of sleep experienced by patients in ICUs and the factors affecting their sleep.

Data concerning the quality and interval of sleep along with study design, sample size and critical/intensive care context were extracted, appraised and summarised from a number of nursing and other health and education databases, e.g. PubMed, CINAHL, Psychinfo, the Australian Digital Theses Program and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Findings from the literature review revealed that total sleep time is normal or reduced with significant interruption. Light sleep is prolonged, and deep and rapid eye movement sleep is reduced. The most likely influences on sleep quality were high sound levels, frequent interventions and medications. The data obtained from polysomnography (sleep studies) were supported by patient self-reports. There was considerable variation in data between patients and studies affecting generalisability.

Evidence-based practice

• Intensive care patients’ sleep is significantly disrupted.

• Alternative methods of quantifying sleep for intensive care patients is required‥

• Few large observational or interventional studies have used sleep studies or polysomnography and synchronised recordings of intrinsic and extrinsic disruptive factors. These studies are required in order to improve sleep for intensive care unit patients.

Information about sleep patterns of children should also be sought from parents. However, some parents may not realise that there is a wide variability in the sleeping patterns of infants and may need reassurance if their infant seems to sleep less than others but is otherwise healthy and thriving (Iglowstein and others, 2003). Hunger, excessive warmth and separation anxiety are factors that may contribute to an infant’s difficulty going to sleep or frequent awakening during the night. Often, older children are able to relate fears or worries that inhibit their ability to fall asleep. If children frequently wake in the middle of bad dreams, parents can identify the problem but perhaps do not understand the meaning of the dreams. Parents can also describe the typical behaviour patterns that foster or impair sleep, such as excessive stimulation from active play or visiting friends. With chronic sleep problems, parents can relate the duration of the problem, its progression and children’s responses. Parents of infants may need to keep a 24-hour log of their infant’s waking and sleeping behaviour for several days to determine what may be causing the problem. The infant’s eating pattern and sleeping environment also need to be described, since these may influence sleeping behaviour.

TOOLS FOR ASSESSMENT OF SLEEP

There are several subjective and objective sleep assessment tools available. Subjective sleep assessment tools include the visual analogue scale, and subjective rating scales where clients are asked to place a mark on a horizontal line, marked 0–10 or 0–100, at the point corresponding to their perceptions of the previous night’s sleep (Ebersole and others, 2004; Joanna Briggs Institute, 2004). These scales can be repeatedly administered to show change over time. Such scales are useful for assessing an individual client, but not for comparing clients. Other validated sleep assessment tools are brief and simple enough to be administered in the clinical setting, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) (freely available at http://epworthsleepinessscale.com). Subjective sleep assessment tools are not reliable in all instances. For example, one study involving 82 lucid, orientated clients in a critical-care unit found that no tool produced a close association between the nurses’ and the clients’ assessment of their sleep (Richardson and others, 2007). The validity of sleep assessment tools on cognitively impaired aged-care residents has also been questioned (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2004).

Objective sleep assessment tools include wrist actigraphy and polysomnography. A wrist actigraphy assessment is a monitoring device attached to the client’s non-dominant wrist, which measures body movements at 1- to 5-second intervals. Some wrist actigraphy devices also measure sleep environment factors such as noise and light, as well as recording the client’s sleep patterns. Wrist actigraphy is considered an objective tool which is non-invasive and can be used in the client’s normal sleep environment. Polysomnography records brain and muscle activity associated with the sleep–wake cycle via electrodes attached to the client’s body. Although polysomnography is considered to be the benchmark in objective sleep assessment tools, its main disadvantage is that it can only be used in a sleep laboratory, effectively removing clients from their normal sleep environment (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2004).

SLEEP HISTORY

If clients report that they enjoy adequate sleep, the sleep history can be brief (Box 35-5). A determination of usual bedtime, normal bedtime rituals, preferred environment for sleeping and what time the client usually rises gives the nurse information for planning care conducive to sleep. When suspecting a sleep problem, the nurse assesses the quality and characteristics of sleep in greater depth.

BOX 35-5 COMPONENTS OF A SLEEP HISTORY

• Satisfaction with quality and quantity of sleep

• Description of client’s sleep problem

• Usual sleep pattern prior to sleep problem

• Recent changes in sleep pattern

• Bedtime routines and sleeping environment

• Use of sleep and other prescription medications and over-the-counter drugs

• Pattern of dietary intake and amount of substances (e.g. alcohol, caffeine) that influence sleep

DESCRIPTION OF SLEEPING PROBLEMS

When a client identifies or the nurse suspects a sleep problem, the nursing history must be detailed so that therapeutic care can be provided. Open-ended questions help a client describe a problem more fully. A general description of the problem followed by more-focused questions usually reveals specific characteristics that can be used in planning therapies.

To begin, the nurse needs to understand the nature of the sleep problem, its signs and symptoms, its onset and duration, its severity, any predisposing factors or causes and the overall effect on the client. Assessment questions might include the following:

• Nature of the problem: What type of problem do you have with your sleep? Why do you think your sleep is inadequate? Describe a recent typical night’s sleep. How is this sleep different from what you are used to?

• Signs and symptoms: Do you have difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep or waking up? Have you been told that you snore loudly? Do you have headaches when waking? Does your child wake from nightmares?

• Onset and duration: When did you notice the problem? How long has this problem lasted?

• Severity: How long does it take you to fall asleep? How often during the week do you have trouble falling asleep? How many hours of sleep a night did you get this week? Compare that with what is usual for you. What do you do when you wake during the night or too early in the morning?

• Quality of sleep: Do you wake up refreshed?

• Predisposing factors: What you do just before going to bed? Have you recently had any changes at work or at home? How is your mood, and have you noticed any changes recently? What medications or recreational drugs do you take on a regular basis? Are you taking any new prescription or over-the-counter medications? How long have you been taking medications? Do you eat spicy or greasy foods or drink alcohol or caffeine that could be interfering with your sleep? Do you have a physical illness that might be interfering with your sleep? Does anyone in your family have a history of sleep problems?

• Effect on client: How has the loss of sleep affected you? (Ask a partner or friend whether they have noticed any changes in behaviour since the sleep problem started.) Do you feel excessively sleepy, irritable or have trouble concentrating during waking hours? Do you have trouble staying awake or have you fallen asleep at inappropriate times, such as while driving, sitting quietly in a meeting or watching TV?

Proper questioning helps the nurse determine the type of sleep disturbance and the nature of the problem. Table 35-1 gives examples of other questions to ask when specific sleep disorders are suspected.

TABLE 35-1 QUESTIONS TO ASK TO ASSESS FOR SLEEP DISORDERS

As an adjunct to the sleep history, a client and bed partner may be asked to keep a sleep–wake log for 1–4 weeks (Beck-Little and Weinrich, 1998). The sleep–wake log is completed daily to provide information on day-to-day variations in sleep–wake patterns over extended periods. Entries in the log often include 24-hour information about various waking and sleeping health behaviours such as physical activities, mealtimes, type and amount of intake (alcohol and caffeine), time and length of daytime naps, evening and bedtime routines, the time the client tries to fall asleep, night-time waking and the time of waking up in the morning. A partner can help record the estimated times the client falls asleep or wakes. Although the log is helpful, the client must be motivated to participate in its completion. Ordinarily it is not used with acutely ill clients who have short hospital stays.

USUAL SLEEP PATTERN

Normal sleep is difficult to define because people vary in the quantity and quality of sleep that they perceive as adequate for them. It is important, however, to have clients describe their usual sleep pattern to determine the significance of the changes created by a sleep disorder. Knowing a client’s usual, preferred sleep pattern allows a nurse to try to match sleeping conditions in a healthcare setting with those in the home. To determine the client’s sleep pattern, the nurse asks the following questions:

1. What time do you usually go to bed each night?

2. What time do you usually fall asleep? Do you do anything special to help you fall asleep?

3. How many times do you wake at night? Why?

4. What time do you typically wake up in the morning?

5. What time do you get out of bed for good once you have woken?

6. What is the average number of hours you sleep each night?

The nurse compares these data with the predominant pattern found for other clients of the same age. Based on this comparison, the nurse begins to assess for identifiable patterns such as insomnia.

Clients with sleep problems may show patterns drastically different from their usual one, or the change may be relatively minor. Hospitalised clients usually need or want more sleep as a result of illness. However, some may require less sleep because they are less active. Clients who are ill may think that it is important to try to sleep more than is usual for them, eventually making sleeping difficult.

PHYSICAL ILLNESS

The nurse determines whether the client has any pre-existing health problems that might interfere with sleep. A history of mental health problems may also make a difference. For example, a client with bipolar disorder sleeps more when depressed than when manic. A depressed client often experiences fragmented sleep that is inadequate. Chronic diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic pain problems interfere with sleep. If a client takes medications to aid sleep, the nurse gathers information about the type and amount of medication that is being used. The nurse may also assess daily caffeine intake.

If the client has recently undergone surgery, the nurse can expect the client to experience some disturbance in sleep. Clients may wake frequently during the first night after surgery and receive little deep or REM sleep. Depending on the type of surgery, it may take several days for a normal sleep cycle to return. Lewis and others (2004) indicate that postoperative pain is the most severe in the first 2 days and that appropriate pain control will contribute to the ability of the client to sleep.

CURRENT LIFE EVENTS

The nurse learns whether the client is experiencing any changes in lifestyle that may be disrupting sleep. A person’s occupation may offer a clue to the nature of the sleep problem. Changes in job responsibilities, rotating shifts or long hours can contribute to a sleep disturbance. Questions about social activities, recent travel or mealtime schedules help clarify the sleep assessment.

EMOTIONAL AND MENTAL STATUS

If a client is anxious, excitable or angry, mental preoccupations can seriously disrupt sleep. The client may be experiencing emotional stress related to illness or situational crises such as loss of job or a loved one. Thus the client’s emotions may affect the ability to sleep. Clients with mental illness may need mild sedation for adequate rest. The nurse assesses the effectiveness of the medication and its effect on daytime function.

BEDTIME ROUTINES

The nurse asks what the client does to prepare for sleep. For example, the client may drink a glass of milk, take a sleeping pill, eat a snack or watch television. The nurse assesses habits that are beneficial and those that have been found to disturb sleep. Not all clients are alike. Watching television may promote sleep for one person, whereas another person may be stimulated to stay awake. Sometimes pointing out that a particular habit may be interfering with sleep can help clients find ways to change or eliminate habits that may be disrupting sleep.

The nurse should pay special attention to a child’s bedtime rituals. The parents can report whether it is necessary, for example, to read the child a bedtime story, rock the child to sleep or engage in quiet play. Some young children need a special blanket or stuffed animal when going to sleep.

BEDTIME ENVIRONMENT

The nurse asks the client to describe preferred bedroom conditions. The bedroom may be dark or light, and the door to the room may be open or closed. The client may listen to the radio or watch television, or prefer a quiet environment. In addition, a child may require the company of a parent to fall asleep. The nurse may learn that changes in the home or institutional environment will be necessary to promote sleep. In a healthcare environment there may be environmental distractions that can interfere with sleep, such as a room-mate’s television, an electronic monitor in the hallway, a noisy nurses’ station or another client who cries out at night. The nurse identifies factors that can be reduced or controlled.

BEHAVIOURS OF SLEEP DEPRIVATION

Some clients may be unaware of how their sleep problems affect their behaviour. The nurse observes for behaviours such as irritability, disorientation (similar to a drunken state), frequent yawning and slurred speech. If sleep deprivation has lasted a long time, psychotic behaviour such as delusions and paranoia may develop. For example, a client may report seeing strange objects or colours in the room, or may seem afraid when the nurse enters the room.

Clients hospitalised in ICUs for an extended time may experience sensory overload (Bennun, 2001). Constant environmental stimuli within the ICU, such as strange noises from equipment, the frequent monitoring and care given by nurses, ever-present lights and lack of colour stimulation, confuse clients (Fontaine and others, 2001). Repeated environmental stimuli and the client’s poor physical status lead to sleep deprivation. Nurses can attempt to cluster episodes of care, particularly at night, to reduce the frequency of disturbance and minimise sleep deprivation (Tamburri and others, 2004).

CLIENT EXPECTATIONS

People who suffer from insomnia often focus their pre-sleep thinking on negative thoughts including the inability to sleep, causing a vicious circle of sleeplessness. The nurse must use a skilled and caring approach to assess clients’ sleep needs. It is useful to ask what practices clients currently use and how successful they are. The nurse also asks clients what other ways of promoting sleep they prefer and how they might be implemented. It is important to understand clients’ expectations regarding their sleep pattern.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

Assessment reveals clusters of data that include defining characteristics for a sleep problem that results from disturbed sleep (Ackley and Ladwig, 2011). If a sleep pattern disturbance is identified, the nurse specifies the condition (Box 35-6) (Doenges and others, 2010). By specifying the nature of a sleep disturbance, the nurse can design more-effective interventions. For example, the nurse uses different therapies for clients who are unable to fall asleep from those for clients with sleep apnoea. Box 35-7 demonstrates how to use nursing assessment activities to identify and cluster defining characteristics to make an accurate nursing diagnosis.

BOX 35-7 SAMPLE NURSING DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

| SLEEP DISTURBANCES | ||

|---|---|---|

| ASSESSMENT ACTIVITIES | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS | NURSING DIAGNOSIS |

| Ask client to explain nature of sleep problem. Use prompts to refine assessment. | Client reports difficulty in falling asleep, taking up to an hour. Client reports waking up 2-3 times nightly, with difficulty returning to sleep. | Sleep pattern disturbance, difficulty falling and/or remaining asleep related to worry over job loss. |

| Observe client’s behaviour and ask bed partner if behaviour changes have been noted. | Client admits to not feeling well rested. Partner describes episodes of client being lethargic and irritable. | |

| Determine whether client has had recent lifestyle changes. | Partner reports client recently lost job, has concern over finding new position. | |

Assessment should also identify the related factor or probable cause of the sleep disturbance, such as a noisy environment, a high intake of caffeinated drinks in the evening, or stress involving a marital relationship. These causes become the focus of interventions for minimising or eliminating the problem. For example, if a client is experiencing insomnia as a result of a noisy healthcare environment, the nurse could offer some basic recommendations for helping sleep, such as controlling the noise of hospital equipment, reducing interruptions or keeping doors closed. If the insomnia is related to worry over a threatened marital separation, the nurse’s actions involve introduction of coping strategies and creation of an environment for sleep. If the probable cause or related factors are incorrectly defined, the client may not benefit from care.

Sleep problems may affect clients in other ways. For example, a nurse may find that a client with sleep apnoea has problems with a spouse who is tired and frustrated over the client’s snoring. In addition, the spouse is concerned that the client is breathing improperly and thus is in danger. The nursing diagnosis of ineffective family coping indicates that the nurse must provide support to the client and spouse so that they can understand sleep apnoea and obtain the medical treatment needed.

Dudley is diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) after referral to a sleep study which demonstrated significant periods of apnoea with desaturation to 78%. As part of his medical management, Dudley is prescribed nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

• CRITICAL THINKING

1. What other interventions will you need to plan with Dudley as part of the management of his OSA?

2. What lifestyle modifications will help improve sleep (think about obesity and alcohol consumption in this case)?

3. What relationship and body image concerns relating to CPAP may need to be addressed?

PLANNING

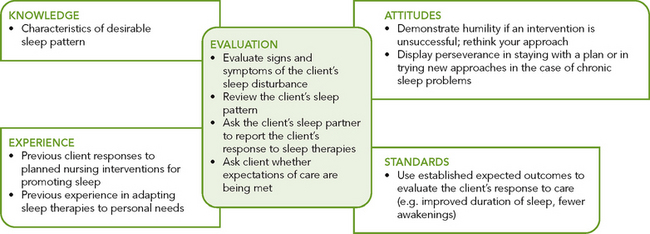

During planning, the nurse again synthesises information from multiple resources (Figure 35-5). Critical thinking ensures that the client’s plan of care integrates all that the nurse knows about the individual, as well as key critical-thinking elements. The nurse develops an individualised plan of care for each nursing diagnosis (see Sample nursing care plan).

Lushington K, Lack L 2002 Non-pharmacological treatment of insomnia. J Psychiatry Relat Sci 39(1):36–49; Rogers AE 1997 Nursing management of sleep disorders, II. Behavioral interventions, ANNA J 24(6):672.

SLEEP ALTERATIONS

ASSESSMENT*

Julie Arnold, a 42-year-old solicitor, is the first client of the morning at the neighbourhood health clinic where you work. When you ask her how she is, she tells you she is having difficulty sleeping. She tells you this started several days after she began feeling pressured at work to complete an important case. On further questioning you find out she is going to bed between 12 and 1 a.m., which is 2 hours later than her normal bedtime and it takes her almost an hour to fall asleep. Julie normally gets 7 hours of sleep a night. Because she is having trouble falling asleep, Julie has been drinking a glass of wine before bedtime. She has 2–3 cups of coffee after dinner to stay awake while working on her case before bedtime. Julie also reports that she wakes up at least once during the night. Julie states, ‘I feel tired when I wake up, and sometimes I have trouble concentrating in the afternoon at work. I have stopped my routine of walking a mile a day.’ As you observe Julie, you notice she has dark circles under her eyes, shifts her position in the chair multiple times and yawns frequently. Julie also says she seems to have less patience with her children at home.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS: Sleep pattern disturbance related to psychological stress from job pressures.

PLANNING

| GOALS | EXPECTED OUTCOMES |

|---|---|

| Client will achieve an improved sense of adequate sleep within 2 weeks. | Client will report waking up less frequently during the night and feeling rested within 2 weeks. |

| Client will achieve a more normal sleep pattern within 2 weeks. | Client will state adherence to a regular bedtime routine within 1 week. |

| Client will fall asleep within 30 minutes of going to bed within 2 weeks. | |

| Client will report sleeping 7 hours nightly within 2 weeks. |

| INTERVENTIONS† | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| Sleep enhancement

• Encourage client to establish a bedtime routine and a regular sleep pattern. • Instruct client to limit caffeine, nicotine and alcohol before bedtime. • Help client identify ways to eliminate stressful concerns about work before bedtime (e.g. taking time before actual sleep time to read a light novel). • Adjust environment; have client control noise, temperature and light in the bedroom. • Encourage client to reinstitute walking routinely during the day, but not 2-3 hours before bedtime. • Instruct client on how to perform muscle relaxation before bedtime. |

A consistent routine promotes sleep (Lushington and Lack, 2002). Caffeine and nicotine are stimulants and cause difficulty in falling asleep. Alcohol lightens and fragments sleep (Rogers, 1997). Excess worry and intense activities before bedtime may stimulate client and prevent sleep (Rogers, 1997). A quiet, comfortable environment fosters sleep (Lushington and Lack, 2002). Exercise can increase activity levels and the need for sleep. Exercise just before bedtime is a stimulant that prevents sleep (Rogers, 1997). Relaxation therapy can help reduce anxiety and block arousing thoughts which interfere with sleep (Lushington and Lack, 2002). |

†Intervention classification labels from McCloskey JC, Bulechek GM 2000 Nursing interventions classification (NIC), ed 3. St Louis, Mosby.

*Defining characteristics are shown in bold type.

Goals and outcomes

The nurse and client set realistic expectations for care. Goals are individualised and realistic with measurable outcomes (e.g. achieving a sleep pattern normal for the client). The success of sleep therapy depends on an approach that fits the client’s lifestyle and the nature of the sleep disorder. The goals of any care plan for a client needing sleep or rest include the following:

• The client obtains a sense of restfulness and renewed energy following sleep.

• The client establishes a healthy sleep pattern.

• The client understands factors that promote or disrupt sleep.

• The client assumes self-care behaviours to eliminate factors contributing to the sleep disturbance.

Outcomes for the goal of establishing a healthy sleep pattern involve evaluating the client’s knowledge of sleep hygiene and ability to implement these practices, and discussion with the client and partner about their effectiveness. It is important for the plan of care to include strategies that are appropriate for the client’s living environment and lifestyle. An effective plan includes outcomes established over a realistic time that focus on the goal of improving the quantity and quality of sleep in the home. This type of plan may require many weeks to accomplish. The nurse works closely with the client and significant others to ensure that any therapies, such as a change in the sleep schedule or changes to the bedroom environment, are realistic and achievable.

Setting priorities

In a healthcare setting the nurse plans treatments or routines so that the client is able to rest. For example, in the ICU, nurses check available electronic monitors to track trends in vital signs without waking a client each hour. Other staff members should be aware of the care plan so that they can cluster activities at certain times to reduce awakenings. In a nursing home, the focus of the plan may involve better planning of rest periods around the activities of the other residents. Often the schedule of one room-mate may not coincide with that of another.

Continuity of care

The nature of the sleep disturbance determines whether referrals to additional healthcare providers are necessary. For example, if a sleep problem is related to a situational crisis or emotional problem, the nurse may refer the client to a mental health nurse or clinical psychologist for counselling. When chronic insomnia is the problem, a medical referral or referral to a sleep centre may be beneficial. If the nurse works in an inpatient setting and the client is to receive a referral for continued care after discharge, offering information about the sleep problem will be useful to the home health nurse.