Chapter 43 Community-based nursing focusing on the older person

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Critically discuss the impacts of population ageing for Australian and New Zealand societies.

• Analyse and compare the policy approaches taken by Australian and New Zealand governments in response to the changing patterns of ageing.

• Examine and evaluate models of primary healthcare for the older person across the health continuum.

• Recognise the impact of inequity in community healthcare services for older Indigenous Australians, New Zealand Māori and Pacific peoples and discuss proactive healthcare to minimise their ill-effects.

• Evaluate the impact of formal and informal primary healthcare systems for the older person, their family and society.

• Recognise the complex scope of Australian and New Zealand community nursing care services for an ageing population.

• Identify the key principles and responsibilities of culturally competent community nursing practice in care of the older person.

• Consider future directions of community nursing services for the older person and their family.

Healthcare for older persons is one of the major challenges facing developed countries now and will be even more of a challenge in future decades. In most countries the chronological age of 65 years signals the start of old age, but there is no universally accepted criterion (World Health Organization, 2011). An estimated 20% of the population of developed countries is now over the age of 60 years, and by 2050 that age group is predicted to make up a third of the population in those countries (United Nations Population Fund, 2010). Ageing baby-boomers, declining fertility and ever-improving health treatments and technologies have created a population bulge of older people who are healthier and living longer than their parents did, but often live with a chronic illness. Therefore, healthcare for the older person is integral to nursing care in all clinical settings and especially so in the community, because that is where the vast majority of older people live (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006). Nurses are at the ‘frontline’ of community-based care and their role is of the utmost importance in health promotion, disease prevention and ongoing care for those with chronic illness.

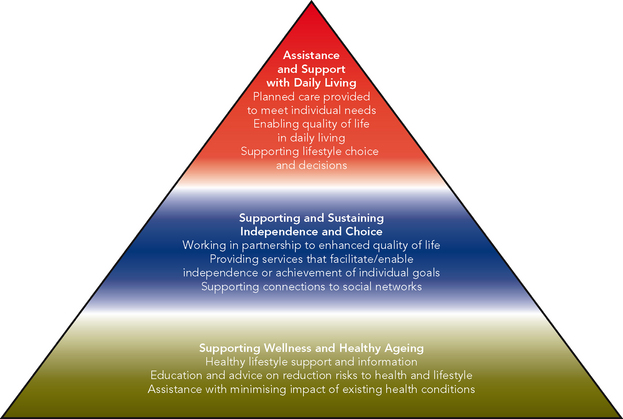

In this chapter, factors that influence the health of older people are explored, including the effects on their lives of health problems and healthcare that supports them to live as well as possible. The chapter also covers an overview of legal, policy, governance and conceptual perspectives of older person health. Healthcare systems and nursing roles and competencies that best support older person health are presented for critique. Models and frameworks will be used throughout the chapter to illustrate aspects of older person health, through triangular diagrams that represent how aspects of care intersect. Community-based care for younger adults and adolescents are covered in Chapter 20 of this textbook.

Health support for older people in Australia and New Zealand

Ageing population profile

Along with many developed countries, Australia and New Zealand have a growing population over the age of 65 years. In the next 15 years, this population will nearly double as the ‘baby-boomer’ generation ages. In Australia in 2009 there were approximately 4.1 million people aged 60 years and older, and this number is expected to rise from the current 13.5% of the total population to 22% (17.1 million) in 10 years’ time (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010). An important consideration for health policy is the steadily increasing number of people aged over 85 years, with numbers expected to peak at 5.8 million during 2010–2015 and not expected to slow until 2020. Women are living longer than men, with the number of women aged 80 years and over predicted to be almost double that of men in 2016.

New Zealand has a younger population than Australia, but a similar rate of growth for people over the age of 65 years (13% of the total population), which is expected to grow much more rapidly by 2031 (22%) and by 2051 (25%) (Statistics New Zealand, 2009). Unlike the steady growth in the small number of older Indigenous Australians (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009a), increases in New Zealand’s older Māori and Pacific peoples will be particularly significant over the next 50 years (Statistics New Zealand, 2009). There is an expected 270% increase in the proportion of Māori aged 65 years and over, and a more than 400% increase in the proportion of Pasifika people aged 65 years and over. Other ethnic minority populations, while relatively young, are also projected to increase significantly.

While the ageing process is experienced and understood by older people, their families and cultural communities in many different ways, most Australians and New Zealanders aged 65 years or over are relatively fit and healthy. However, the burden of morbidity and mortality among Indigenous Australians is significantly worse than that of non-Indigenous Australians and of other ‘Anglo-settler societies’ like New Zealand (Hunter, 2007). The majority of older non-Indigenous Australians are well enough to live independently, with 80% of 60- to 79-year-olds living alone in a private dwelling, compared with 34% of those aged 80 years and over. Only a minority are frail and vulnerable and require high levels of care and disability support, usually during the last few years of their lives or as a result of chronic illness or disability that may have been present for many years. Consequently, the proportion of people, including Indigenous Australians, living in cared accommodation increases with age and illness, rising from 1.1% of all 60- to 79-year-olds to 15% of people aged 80 years and above (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010). Of the small number of older people living in non-private dwellings, the majority (54%) live in some sort of cared accommodation, including nursing homes or aged-care hostels (50%) and hospitals (3.0%).

The ageing of the population has impacts on different community members and systems, mainly the family. Informal care support is provided by families for approximately 80% of people over 65 years of age with a chronic illness. More than one million people over 65 years of age also receive community-based services, usually for chronic illnesses support (Department of Health and Ageing, 2010a). Access Economics (2010) has estimated that around 60% of Australians with dementia are living in the community and the majority of them are supported by 6.2 million informal carers (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011a) (Figure 43-1). Family support in Australia and in New Zealand is supplemented by a mix of government and non-government community-based services, which together help the older person to maintain connections to family and community and exercise choice of services if they require a higher level of care.

FIGURE 43-1 The level of care required by older people varies from individual to individual.

Image: iStockphoto/Guven Demir.

While people are healthier for longer than in past generations, the rapid growth of the number of chronic illnesses that tend to occur in older age will inevitably increase pressure on health funding. A New Zealand Ministry of Health paper (Johnston and Teasdale, 1999) projected that, based on 2000–01 patterns, health expenditure would need to grow by an average of 3.6% per year over the next 50 years to meet increased demand for existing services (Ministry of Social Development, 2001). The actual rate of increase is difficult to predict, however, because of the impact of other factors, such as changes in the availability of informal carers, technological advances, rising expectations for more and better services and changing rates of disability among older populations, which can work to either increase or decrease funding pressures. Australian and New Zealand governments have responded to the challenge of age-related chronic illness by establishing policies to support active, healthy ageing to reduce the prevalence of disability (Department of Health and Ageing, 2011a; Ministry for Social Development, 2001).

• CRITICAL THINKING

Spend a couple of minutes now thinking about how future changes in the age profile of the population might affect the community in which you live.

• What activities do you know of that are popular with active older people?

• Explain what needs to happen for public facilities to meet the needs of a growing older population.

• What effect would there be on general practice services?

• What other health services might be affected by an older but healthier population?

Policy contexts

Australia

There are a number of government ageing strategies that set the context for aged-care policy. The key Australian aged-care policy makers include:

• the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), which has taken a broad strategic approach to the implications of an ageing population, including those related to health

• the National Health and Hospital Reform Commission, which provides an opportunity to examine Australia’s healthcare system and make recommendations to reform this system and provide best possible health outcomes for all

• the Australian Health Ministers Conference, which has taken a range of initiatives in relation to older people and health—in particular the key guiding principles outlined in the National action plan for improving the care of older people across the acute–aged care continuum (Productivity Commission, 2012).

Community-based health services for older Australians are framed by the COAG’s (2008) National Healthcare Agreement (NHA), ‘Intergovernmental agreement on federal financial relations’, which aims to improve health outcomes for all Australians while sustaining the Australian healthcare system. The NHA defines the objectives, outcomes, outputs and performance measures, and clarifies the roles and responsibilities that will guide the Australian and state/territory governments in the delivery of health services across the health continuum (Commonwealth of Australia, 2009). The COAG recognises the significant role of private providers and community organisations in providing a well-coordinated, or care-managed, assessment pathway that is tied to needs-based care planning and service delivery (Swerissen and Taylor, 2008).

The COAG (2008) affirms the agreement of all state and territory governments that the major goals of Australia’s healthcare system must:

• be shaped around the health needs of individual patients, families and their communities

• focus on prevention of disease and the maintenance of health, not simply the treatment of illness

• support an integrated approach to the promotion of healthy lifestyles, prevention of injury and diagnosis and treatment of illness across the continuum of care and

• provide all Australians with timely access to quality health services based on their needs, not ability to pay, regardless of where they live in the country.

Following recent National Health and Hospitals Network (NHHN) reforms, the Australian government now takes full policy and funding responsibility for aged-care services (except in Victoria and Western Australia) to generate greater consistency for low-care to high-care needs across aged care (Council of Australian Governments, 2010). The Australian government funds 68% of aged-care services, and jurisdictional governments contribute 5.4%. Individual clients or their families contribute 26.2% through service fees, which are capped at a maximum of 17.5% of the basic single aged pension, or an additional fee limited to 50% of any income above the basic rate of a single pension for people on higher incomes (Hogan, 2004). While the Australian government allocates funds to state and territory governments for health services, each state and territory takes responsibility for funding and monitoring acute, sub-acute and ambulatory care services for older people in their own jurisdiction. This process differs for some older Indigenous Australians, where Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) contribute to primary healthcare services through Aboriginal-led locally elected boards of management (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011b).

Governance by Aboriginal boards of management supports the rights of Indigenous Australians to attain good quality of life in older age through self-determined community-based health programs. For Australian Indigenous communities, the health of their older members is not just about individual physical wellbeing. Health incorporates all aspects of a person’s life, including control over the physical environment, maintaining personal and community dignity and self-esteem, and justice. Health includes the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community, which is directly associated with the community’s relationship to the land of their ancestors. This is a whole-of-life view and also includes the cyclical concept of life–death–life (Anderson and others, 2006).

Optimal primary healthcare for older Indigenous Australians will, therefore, provide a wide range of health-related community support services to achieve whole-community health. These may cover a variety of services, for example community development work; advocacy for legal, public housing, Centrelink and disability issues; cultural promotion activities; and transport to medical appointments (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011b). Services to rural and remote areas are provided through regional primary health services (RPHSs), which consolidate a range of these existing programs in a flexible way. As an example of flexible community health programs for Indigenous people that will affect the whole community, in December 2011 the Minister for Australian and Torres Strait Islander Health launched toolkits for health workers, including nurses, to tackle the high rates of smoking and chronic disease such as type 2 diabetes and smoking-related deaths in these communities. By June 2013 the ACCHOs will employ up to 172 new people to work with local communities to develop whole-community anti-smoking programs that will have a significant impact on reducing heart and cerebrovascular illness linked to dementia and stroke (Department of Health and Ageing, 2011b).

New Zealand

The ‘Health of Older People Strategy’ is a key plank of the New Zealand Positive Ageing Strategy (Ministry of Social Development, 2001). The strategy focuses on older people’s health and wellbeing through coordinated and responsive health and disability support programs. Development of the strategy was guided by the aims and principles of the New Zealand Health Strategy (Ministry of Health, 2000), New Zealand Disability Strategy (Minister for Disability Issues, 2001) and the Māori Health Strategy He Korowai Oranga (King and Turia, 2002). The Health of Older People Strategy sets out a comprehensive framework for planning, funding and providing services, and includes a work programme for the Ministry of Health to provide a national framework for implementing the strategy and identifies the action steps for district health boards (DHBs) to develop an integrated approach to service provision in their own districts. Implementing the strategy requires the Ministry of Health and DHBs to systematically review and refocus services to better meet the needs of older people now and in the future by reallocating available resources between services.

Services and programs within the jurisdiction of New Zealand’s Positive Ageing Strategy include health promotion, preventive care, specialist medical and psychiatric care, hospital care, rehabilitation, community support services, equipment, respite care and residential care. All health services are older-person focused, the wellness model is promoted, services are coordinated and responsive to needs, the family’s, whānau and carer’s needs are also considered and where appropriate there is information sharing and a smooth transition between services. Planning and funding arrangements support integration. Employing an integrated continuum of care approach means that the older person is able to access needed services at the right time, in the right place and from the right provider (Ministry for Social Development, 2001). These ‘three ‘Rs’ are achieved through close collaboration between health service providers, families, whānau and carers to fulfil the following objectives:

1. Older people, their families and whānau are able to make well-informed choices about options for healthy living, health care and/or disability support needs;

2. Policy and service planning support quality health and disability support programmes integrated around the needs of older people;

3. Funding and service delivery promote timely access to quality integrated health and disability support services for older people, family, whānau and carers;

4. The health and disability support needs of older Māori and their whānau are met by appropriate, integrated health care and disability support services;

5. Population-based health initiatives and programmes promote health and wellbeing in older age;

6. Admission to general hospital services is integrated with any community-based care and support that an older person requires; and

7. Older people with high and complex health and disability support needs have access to flexible, timely and co-ordinated services and living options that take account of family and whānau carer needs.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Take some time now to reflect on the policies and strategies that guide health services for older adults in Australia and New Zealand.

1. What values and beliefs of society are reflected in the intentions of these policies and strategies?

2. How are the interests of older people prioritised and served in your community?

3. To what extent do the health policy documents for older person health in Australia and New Zealand reflect a holistic view of health, especially with regard to Māori and Australian Indigenous peoples?

4. Make a list of the ways that older people are supported in the community in which you live. What facilities are especially user-friendly for them?

5. What improvements do you think could be made to cater better for their needs?

6. What may be some future options for housing for older people?

Healthcare for populations as well as individuals

Older people are members of many different communities—social, cultural, recreational, spiritual and political—and policies to support their health and wellbeing therefore focus on improving the health of individuals, families, communities and systems by modifying the social determinants of health (Box 43-1).

BOX 43-1 THE FEATURES OF A POPULATION HEALTH APPROACH

• A culture across the organisation that places the same emphasis on promoting health and preventing disease as on treating illness

• Investment in activities that influence the determinants of health

• Operational commitment to reducing inequalities

• Inter-sectorial and intra-sectorial collaboration on local initiatives so that there are working partnerships and alliances with a range of community groups

• Genuine community participation

• Support for sustainable community development

• Data collection that is comprehensive and considers ethnicity, deprivation and outcomes

• Workforce development to support this wider population health approach

From Poore M 2004 Would you recognise a population health approach if it passed you in the street? Wellington, Ministry of Health.

There are five characteristics of population health (Keller and others, 2002). First, there is a focus on entire populations (those possessing similar health concerns or characteristics, such as the older person with a chronic illness); second, population-based practice is based on thorough community-involved health assessment to establish priorities and planning; third, population-based care includes the range of the determinants of health: social, economic, spiritual, physical and psychological. The fourth element is that all levels of prevention are employed. Primary prevention improves health before a problem has occurred, and secondary prevention reduces risk factors or early symptoms and continues on to disease management and chronic care. Finally, population-based practice employs interventions for populations, communities, families and individuals, and emphasises population health outcomes to reduce health inequity through the delivery of healthcare that portrays the features of primary health-care. In their community-based practice, nurses work in a variety of ways to provide care for individuals and also for populations (McKillop and others, 2011). The nature of their practice is described later in this chapter.

Population health supports care for people at all life stages and levels of health need. Systems are required for identifying health inequity in a population, planning health improvement initiatives in collaboration with the community and accessing local services that can contribute to health gain. Mechanisms are required to establish cooperative, integrated care, improve access to healthcare, collect and manage health information and monitor health gain indicators against population health targets (Coster and Gribben, 1999), such as the ACCHO governance system for Indigenous people established by the Australian government (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011) and the New Zealand government’s Māori Health Strategy (King and Turia, 2002). Population-based healthcare:

focuses on entire populations, is grounded in community assessment, considers all health determinants, emphasises prevention and intervenes at multiple levels.

Population-based primary healthcare for the older person is provided at three levels simultaneously. The treatment of the biophysical effects of disease, such as type 2 diabetes, characterises a ‘short-term, problem specific, individual-based “downstream” approach’ (Cypress, 2004:249); midstream healthcare includes early risk detection and reduction of the factors giving rise to lifestyle-influenced diabetes through a partnership approach (McKinlay and Marceau, 2000); and upstream actions aim to strengthen the structural determinants affecting a person with a health condition like type 2 diabetes, which can include education, employment, housing, transport, nutrition, income and working conditions (Keller and others, 2004; Kleffel, 1991; Sharpe, 2006). A population health approach is fundamental to the ‘new’ primary healthcare.

Primary healthcare

Modern-day primary healthcare has its origins in the global primary healthcare strategy conceived by nations attending the WHO conference at Alma-Ata in South Eastern Russia in 1978, where they collectively called for ‘Health for all by the year 2000’ and vowed to embrace the principles of the Declaration of Alma-Ata:

1. health as a basic human right

2. inequity as politically, socially and economically unacceptable; and

3. health as a reflection of the social and economic conditions affecting people’s lives (World Health Organization, 1978).

These three principles heralded a turnaround from the view of health as a biological state, directed at individuals, experienced and modified by individuals and separated from the socioeconomic and political environment in which people reside. While the year 2000 is long gone and universal health remains an aspiration, the Declaration of Alma-Ata was a turning point for primary healthcare towards more actively addressing persistent inequity, injustice and general lack of fairness in the delivery of healthcare (Salmond, 2008).

A fundamental shift in the provision of primary healthcare was required to reach the goals agreed to at Alma-Ata, a shift that continues today (McKillop and others, 2012). Nurse leaders in New Zealand have defined primary healthcare nursing as:

practical and research-based. Employing socially and culturally acceptable practices, nurses make care accessible to people in the places they live and work. Primary health care nurses aim to reduce inequity in the health status of the population, in particular for Māori, Pacific and other underserved populations. A population health approach is required, alongside work to assist individuals to make decisions about their own health and independence.

Traditionally, primary healthcare has been delivered in Australia and New Zealand from general practice clinics originally set up for illness treatment rather than wellness support. When a health service is geared for treatment of sporadic, one-off illness episodes or for regular chronic illness management, health promotion and assessment of illness risk are more likely to be neglected (McKillop and others, 2012). More recently, health policy and funding have targeted healthcare along the continuum from health promotion to illness care, but changes in the way primary healthcare is organised are required to enable new approaches to primary healthcare.

An example of a new approach to primary healthcare is the program of the Australian government to help improve the health and wellbeing of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011b). While comprehensive primary healthcare includes access to nurses, Aboriginal Health Workers and other healthcare professionals, it also includes access to social and emotional wellbeing services. These programs help individuals to reunite with their kinship networks, and include the ‘Bringing Them Home’ and ‘Link Up’ programs and counselling services associated with family and community reconnection. The ‘Bringing Them Home’ and ‘Link Up’ counsellors help individuals (many of whom are now over 55 years of age), families and communities affected by past practices of the forced removal of children from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families to reunite with their families, culture and community, and to restore their social and emotional wellbeing. The focus of the Bringing Them Home counsellor program provides counselling and related services to individuals and families, while the Link Up services support people in tracing, locating and reuniting with their families. Access to these particular primary healthcare services is critical for preventing ill-health, effectively managing stress-related chronic disease and improving health outcomes to close the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011b). Comparisons between ‘old’ and ‘new’ primary healthcare are presented in Table 43-1.

TABLE 43-1 THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN ‘OLD’ AND ‘NEW’ PRIMARY HEALTHCARE

| OLD PRIMARY HEALTHCARE | NEW PRIMARY HEALTHCARE |

|---|---|

| Focuses on individuals | Looks at health of populations as well |

| Provider focused | Community and people-focused |

| Emphasis on treatment | Education and prevention important too |

| Doctors are principal providers | Teamwork—nursing and community outreach crucial |

| Fee-for-service | Needs-based funding for population care |

| Service delivery is monocultural | Attention paid to cultural competence |

| Providers tend to work alone | Connected to other health and non-health agencies |

From Ministry of Health 2001 Implementing the primary health strategy. Wellington, Ministry of Health.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Using the new primary healthcare column in Table 43-1, identify at least one example of how each of these aspects of healthcare would be played out in community-based care for older person health.

Community and people-focused healthcare

Community engagement is a prerequisite for consumer and community involvement in the planning and delivery of healthcare for older people. There are various layers of healthcare governance, and each should include community representatives so that the voices of service users and/or their advocates are included in health decisions (Coney, 2004). As previously identified, the concept of ‘community’ has many meanings. Five core elements were derived from a narrative review of 154 definitions of community: its location, sharing common interests and perspectives, joint action as a source of cohesion and identity, a foundation of social ties and that some diversity is expected and accepted since all people are unique (McQueen and others, 2001).

The location of a community is not just where older people live, but also other places that they come together; for example, where they socialise. Rural people are more likely to have greater restrictions to accessing healthcare from home, especially for those living in remote and inhospitable locations. The realities of rural and remote Aboriginal health are distinguished by ‘hardship, sufferance and invisibility’ (Hunter, 2007), referring to the high levels of unrecognised and untreated illness and to the lack of understanding of the extreme difficulties that Indigenous people experience in seeking culturally sensitive healthcare in rural and remote locations. Therefore, where the older person lives and the availability of health infrastructure in that location will influence the way that nurses are able to engage with different rural communities. To provide an effective community health service, nurses will need to gain a good understanding of the shared interests and health perspectives of particular communities when planning and delivering relevant and acceptable health services (McQueen and others, 2001).

Integrated community health services

As previously discussed, the purpose and focus of primary healthcare involves not only care for individuals with health problems, but also health promotion and preventative care. In their health promotion and preventative care work, and in light of ever-increasing rationing of health resources, nurses are challenged to provide older people and their families with the most appropriate education and support to improve the social determinants of health (Sharpe and O’Sullivan, 2006). Effective primary healthcare involves expanded nursing services, community outreach and multidisciplinary team collaboration to provide healthcare across the continuum of care, as identified in the Australian and New Zealand aged care policies (Finlayson and others, 2008; Ministry of Health, 2001, 2003; Productivity Commission, 2012; Wagner and others, 2001).

Primary healthcare providers that are well integrated with each other and other social services can provide a seamless service for their clients (Sheridan, 2005). Nurses need to work with other services to improve access to support to improve the social determinants of health, including housing, education and a range of other social services. Not least, care that is integrated across primary and secondary services can avoid gaps and overlaps in health services. A recent discussion document published by the Australian Primary Health Care Advisory Council (PHCAC) suggests that future primary healthcare organisations, whatever form they take, ‘will need to define together what the glue will be that will hold them together’ (PHCAC, 2009:4). Exploring the implementation of the PHCAC guidelines may reveal the ‘glue’ that integrates services. The way that services are arranged and connected with each other is represented in the model of healthcare on which they are constructed.

Therefore, appropriate community-based nursing will be individualised to suit the client and their family, have a population health focus (Sheridan, 2005) and rely on continuing relationships with other health services (Wagner and others, 2001). This approach requires a reorienting of health services across the health continuum, not just in the primary healthcare sector (Bodenheimer and others, 2002a). Six interlinked components are essential to the effective integration of care (Wagner and others, 2001; Bodenheimer and others, 2002b):

• community resources—mobilising community resources to meet the needs of people with long-term conditions

• healthcare organisation—creating a culture, organisation, and mechanisms that promote safe, high-quality care

• self-management support—empowering and preparing people to manage their health and healthcare

• delivery system design—delivering effective, efficient care and self-management support

• decision support—promoting care that is consistent with research evidence and patient preferences

• clinical information systems—organising patient and population data to facilitate efficient and effective care (Wagner, 1998).

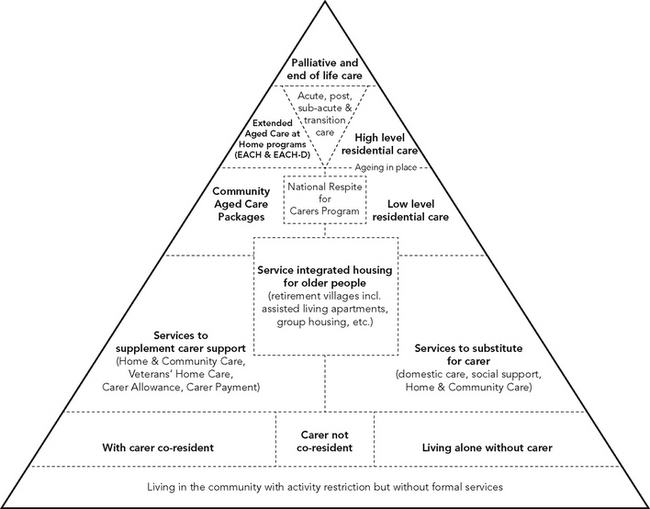

Community-based services for older Australians and New Zealanders

The six components listed above are essential to an effective integrated healthcare system for older people and their families. For example, over one million older Australians and their family carers access government-subsidised integrated community-based services from the following programs (Figure 43-2).

FIGURE 43-2 Services to support older people across the continuum of care.

From Productivity Commission 2011 Caring for older Australians: overview. Inquiry report no. 53. Canberra: Productivity Commission, p. XXIV. © Commonwealth of Australia, Productivity Commission. Reproduced with permission.

AUSTRALIAN AGED-CARE SERVICES

The Home and Community Care (HACC) program is the largest program; it is funded by the states and territories (40%) and the Australian government (60%) under the Home and Community Care Act 1985. Funding is allocated largely based on demand and services are provided at the discretion of providers. HACC services include transport, nursing, home maintenance, counselling and personal care (Department of Health and Ageing, 2009) and the HACC program delivers services to people with a range of disabilities, regardless of whether that disability is related to an acquired condition or injury, and also supports Indigenous health by improving access to community services in rural and remote Australia (Department of Health and Ageing, 2010).

Community Aged Care Packages (CACPs) target older people living in the community with care needs equivalent to those of low-level residential care; it provides the greatest number of operational packages, estimated at around 45,654 in 2010. A range of support services is provided, such as personal care, domestic assistance and social support, transport to appointments, food services and gardening. Approval from an Aged Care Assessment Team (ACAT) is required before services can be obtained (Department of Health and Ageing, 2009).

Extended Aged Care at Home (EACH) packages target older people living at home with care needs equivalent to those of high-level residential care, estimated to provide around 5770 packages in 2010. Approval by an ACAT is also required to receive an EACH package. In addition to the services offered by CACPs, an EACH client may be able to receive nursing care, allied health care and rehabilitation services. EACH-D extends the EACH package with service approaches and strategies to meet the specific needs of care recipients with dementia. In 2010 an estimated 2901 EACH-D packages were offered (Department of Health and Ageing, 2009).

In 2010 the Australian Government trialled 1200 consumer-directed aged-care places in Australia (Department of Health and Ageing, 2011a). Service providers offer consumers the choice of consumer-directed CACPs, EACHs and EACH-Ds to individual consumers based on a needs assessment, with budgets administered on their behalf by an approved provider for an agreed percentage of the allocated budget. The care recipient has the same level of entitlements as those specified under the individual packaged care programs, but holds greater responsibility for the delivery of services. One of the most important objectives of consumer-directed community care is that care recipients have genuine flexibility in program arrangements, such that services can be tailored to the care recipient’s individual circumstances (Department of Health and Ageing, 2011a).

Under the Aged Care Act 1997, the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) uses planning ratios to manage the supply of residential care places and the number of packages offered under the CACP, EACH and EACH-D programs. An average of 23.1 packages per 1000 Australians aged 70 years and over was provided in 2009, with a maximum fee of $8.05 per client per day. The 2011 planning ratio is 113 places per 1000 people aged 70 years and over (Department of Health and Ageing, 2011a), allocated to 44 high-care (residential) places, 44 low-care (residential) places and 25 community-care places which comprise 21 CACPs and 4 EACH or EACH-D packages. Package costs are projected to increase from $A11.1 billion in 2010 to $A59.6 billion in 2050 (equivalent to 451% growth). Of this, the public budget will expend $A44.0 billion while the private sector will expend $A15.6 billion (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011a). Expenditure on HACC clients, community-care packages and operational residential-care places will increase to $A94.2 billion in 2050, around 749%, with public budget estimates being $A69.5 billion and private sector expenditure being $A24.7 billion (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011a).

NEW ZEALAND AGED-CARE SERVICES

New Zealand’s DHBs fund services that support older people to remain in their own homes for as long as they want and are able to. Home support services give older people the ability to make choices in later life about where they want to live, and to receive the support they need to do that. The Ministry of Health is responsible for the development of home and community support services for older people. A continuum-of-care approach is taken for older people’s support services, which emphasises home- and community-based services (Ministry of Social Development, 2001). All older people wishing to access publicly funded support services have their needs assessed by a Needs Assessment Service Coordination (NASC) agency contracted to each of the DHBs.

Older people are also supported through church-based services such as:

• Enliven—service offered by Presbyterian support organisations throughout New Zealand that enables older New Zealanders to stay in their own homes and to remain in control of their own destiny

• Wesley Community Action—a Methodist organisation with experience in working alongside older people in the community to help maintain their independence and quality of life

• Selwyn Centres—parish-based drop-in centres for older people hosted by the Anglican Selwyn Foundation. They offer older people in their communities a morning program which includes gentle exercise, social time and activities, for a nominal fee.

Aged residential-care services are available for older people (usually aged 65 years and over) who need more support than can be made available to them in their own homes. Options include a range of residential home-care facilities and specialist hospital facilities. In addition, a range of services and resources are provided by Age Concern, the Alzheimer’s Society, Arthritis New Zealand, the Cancer Society, Diabetes New Zealand, the Hearing Association, Hospice New Zealand, the Mental Health Foundation, the National Heart Foundation, the National Foundation for the Deaf, the Parkinsonism Society of New Zealand, the Public Health Association, the Royal New Zealand Foundation for the Blind and the Stroke Foundation.

Strengths-based approach

Both Australian and New Zealand aged-care services support a primary-health-care, strengths-based approach that strives to meet older people’s holistic needs by:

• being consumer-directed, allowing older people and their families choice and control over their lives

• being easy to navigate, by helping older people and families know what care and support is available and how to access those services

• promoting independence and wellness in older people and their continuing contribution to society

• ensuring access to person-centred services that can change as the older person’s needs change

• treating older people with dignity and respect

• assisting informal carers and family to perform their caring role

• being affordable for older people requiring care and for society more generally and

• providing incentives to ensure the efficient use of resources devoted to the caring role and broadly equitable contributions between generations.

Supporting the older person with chronic illness

Ageing is a natural part of life and there is great diversity in the health and wellbeing of older people. Two thirds of older Australians who report having ‘good’, ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ health attribute their health status to continued participation in the wider community and to lifestyle choice (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010). The 2009–10 Family Characteristics Survey (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011) found that while the number of Australian grandparent families has decreased since 2003, there remained 17,000 grandparent families in which the grandparents were guardians or main carers of resident children aged 0–17 years, and approximately 43% of people over 65 years of age were actively involved in caring roles and/or volunteer work outside their home (Figure 43-5). As well, at least half of all Australians aged over 65 years (54%; 2.9 million older people) engage in some sporting or exercise program on a regular basis, and regularly walk for fitness (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009b). On the other hand, in vulnerable populations like Australian Aborigines, social disadvantage and ill-health over the lifespan can lead to younger-onset chronic illness (Council of Australian Governments, 2010).

FIGURE 43-5 Older people are commonly engaged in carer roles within the family.

Image: Shutterstock/Yuri Arcurs.

‘Chronic disease’ is an umbrella term used to describe a diverse array of medical conditions, both communicable and non-communicable, that are most prevalent in people over 65 years of age. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW, 2006) and the ‘National Chronic Disease Strategy’ (National Health Priority Action Council, 2005) have broadly described chronic diseases as being:

• complex and multi-factorial in causation

• gradual in onset with variation in symptoms experienced, from acute or sudden onset of symptoms through to symptom-free periods

• persistent and long-term in nature, leading to gradual deterioration of health more prevalent with older age; but, like asthma and renal disease, can occur throughout the lifespan

• compromising to an individual’s quality of life through physical limitations and disability

• not immediately life-threatening but eventually leads to premature mortality.

The AIHW (2006) has reported that 77% of the population has at least one chronic condition and that 80% of the burden of disease and injury is attributable to chronic diseases. In 2007, deaths due to these illnesses/conditions accounted for 77% of all underlying causes of death and were either associated with, or the underlying cause of, 90% of deaths (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010). Data on 9156 patients attending general medical practitioners in 2009 (Family Medicine Research Centre, 2010) revealed that the incidence of chronic disease is on the rise, involving one or more of the following conditions: vascular, musculoskeletal, psychological, asthma, upper gastrointestinal diseases, cardiac, diabetes, cerebrovascular and malignant neoplasms. Australia’s national health priority areas focus on chronic diseases and conditions that are generally occurring in older age: arthritis and musculoskeletal conditions, cancer, cardiovascular health, diabetes mellitus, injury prevention and control, mental health including dementia and obesity.

The leading cause of chronic-illness-related deaths in Australia and New Zealand alike is cardiovascular disease (40%). The proportion of deaths attributed to stroke has decreased from 9.6% of deaths in 1998 to 8.3% of deaths in 2007, although there was no such decrease among Indigenous people. Diabetes is the underlying cause of 6.7% of deaths in Indigenous people, compared with 2.7% of deaths of non-Indigenous people (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010). Trachea and lung cancer together remain the third leading cause of death in Australia, increasing from 5.3% of deaths in 1998 to 5.5% in 2007 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010). Deaths due to dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, which account for 88% of chronic mental health disorders, has moved from seventh leading cause in 1998 to fourth leading cause in 2007 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010). Within the next 20 years, dementia will account for the highest number of chronic diseases in people over 65 years of age (Alzheimer’s Australia, 2011). Chronic illness is the main cause of disability, which rises steadily with age.

In 2009, 48% of older Australians reported having a disability: 36% of people aged 60–64 years, 48% aged 70–74 years and 88% aged 90 years and over (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009b). In the 60- to 79-years age group the disability rate is higher among those living alone (49%) than it is for those living with others (40%). For people aged 80 years and above, the disability rates for living alone and with others is the same (68%). For older people living in a non-private dwelling, nearly four-fifths (79%) had a reported disability, with those living in cared accommodation being much more likely to have a disability (97%) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009b). Thirty-seven per cent of older people (48% for people aged over 85 years) report the need for assistance with at least one activity, including property maintenance (21%), healthcare (19%) and household chores (16%), because of a chronic-illness-related disability.

Impact of chronic illness

Age alone is not the key factor in determining the need for health-care services, but rather ill-health and/or a change in functional capacity. It is predicted that nearly two thirds of the Australian and New Zealand governments’ health expenditures will be consumed by people 65 years and older by 2050, generally peaking in the last two years of life (Access Economics, 2010; National Health Board, 2011). In acute care services alone, people aged 65 years and over accounted for 38% of all hospital admissions and for 51% of all inpatient days in 2007, with those aged over 85 years being more than five times as likely to be admitted to hospital, mainly as a result of chronic illness (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010).

Increasing rates of chronic disease in Australia and New Zealand are placing increasing pressure on health expenditure as well as reduced future labour force participation rates and productivity. Diabetes, for example, is projected to increase from around 5% of the total burden of disease in 2003 to 9% by 2023, primarily due to increasing obesity rates (Access Economics, 2010). Current data on the management of chronic diseases indicate that the current health system works best for individuals with specific, time-limited health needs (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009b). Those with more-complex needs who require ongoing services and management involving collaboration between health, community and aged-care sectors tend to fare worse. Older people with a chronic illness need access to services to maintain their independence, function and wellbeing over the longer term. This increases their chances of remaining at home longer and of avoiding premature admission to residential care and/or re-admission to hospital (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009b). For older people with a mental illness and/or dementia, it is essential to have access to appropriate mental health and psychogeriatric services to assist in their recovery/stability and to eliminate or minimise the need for acute health services, primarily through stronger, better-resourced community-based healthcare (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010).

The future challenges associated with community nursing care for people with chronic illness across all developed countries relate to:

• the significant increase in the number of people aged 85 years and over with one or more chronic illnesses over the next few decades (United Nations Population Fund, 2010)

• the growing number of older people who require complex care for a chronic illness, including dementia, as well as palliative care

• the relative decline in the availability of informal carers, reducing the ability of some older people to receive home-based care

• the increasing cultural and social diversity among older people in their preferences and expectations, including a greater desire for independent living and culturally relevant care

• the declining community and aged-care workforce, and ‘age-induced’ tightening of the overall labour market, alongside the expected relative decline in family support and informal carers and strong demand for healthcare workers from other parts of the health system

• the growing disparity in available and culturally sensitive health services for rural, remote and urban aged populations, especially for Indigenous older people.

Evidence-based chronic illness models

When considering the best fit of health service support for older persons with a chronic illness, Leutz (1999) divided these people into three groups:

• the majority of people with mild to moderate but stable conditions and having high capacity for self-direction and/or strong informal networks who require a select few routine care services

• those with a moderate level of need

• the small percentage of older people with long-term, severe, unstable conditions who frequently require urgent intervention from various sectors and who have limited capacity for self-direction.

Leutz (1999) argued that the first group would likely be served sufficiently by relatively simple systematic linkage of different systems, as long as healthcare providers are aware of and understand how to access the range of services offered by other providers. The group with moderate health support needs would also operate mainly through existing health and social systems, but require additional explicit structures and processes to maintain their health and prevent disability. This would require mechanisms for routinely sharing client information and collaborative discharge planning, case management and coordinated care across various sectors. It is the group with long-term, severe, unstable conditions that is likely to benefit most from a high level of service integration of different service domains. A fully integrated system would assume responsibility for all services, resources and funding, which might be subsumed in one managed structure (Leutz, 1999).

Kaiser Permanente, a US health-maintenance organisation for older people with chronic illnesses, is a good example of a successfully integrated primary healthcare system which successfully provides three different levels of community health services at different levels of need, such as those described by Leutz (1999) (Bodenheimer and others, 2002b). Another influential chronic illness primary healthcare model, also originating in the United States, is the Evercare model, the primary aim of which is to combine preventative and responsive healthcare for older people at high risk of health deterioration, mainly through case management (Boaden and others, 2006). The program uses risk-stratification tools to assess the level of care required and to inform the development of an individualised care plan for older people living in the community, coordinated and monitored by an advanced practice nurse acting as a case manager. The Chronic Care Model (Wagner and others, 1999, 2001) aims to provide a comprehensive framework for the organisation of healthcare for people with chronic conditions via four interacting system components: self-management support, delivery system design, decision support and clinical information systems. The cornerstone of the productive interactions between the healthcare staff and the person in effectively managing the chronic illness is having an ‘informed activated patient’ and a ‘prepared proactive health team’. The role of nurses in chronic care is pivotal to helping people navigate the health service ‘informed and activated’.

The Chronic Care Model (Wagner and others, 1999, 2001) has been influential in informing chronic-care policies in a number of countries (Glasgow and others, 2001). In Australia, the New South Wales Department of Health has embraced the model spearheaded by the Greater Metropolitan Clinical Taskforce (GMCT) Aged Care Health Network, a multi-disciplinary peak-body advisory group to the Director-General of New South Wales on matters relating to the healthcare of older people. One of the goals of the GMCT is to make illness prevention ‘everybody’s business’ by strengthening primary healthcare and continuing care in the community, building community-based health partners to improve the healthcare opportunities and experiences for older people and their families and promoting and evaluating evidence-based chronic illness care models in all health settings.

These well-coordinated, community-based health services are older-person and wellness focused and responsive to older people’s needs.

The changing scope of community nursing practice

The older person is now the core business of the whole healthcare system for those with rapid-response needs, short-term care needs and chronic disease long-term care needs. Consequently, to meet these different healthcare needs the range of services provided and/or coordinated in the community include telehealth; social enterprise; disability care; aged and dementia care and rehabilitation; chronic disease management; personal care and support; palliative care and respite; and specialist consultancies (Commonwealth of Australia, 2009; Ministry of Health, 2001). With the reduced capacity of the acute care sector to meet demand for beds for older people with a chronic illness, and to reduce risks associated with hospitalisation, Australian and New Zealand governments fund subacute and post-acute in-home projects for this population group (Ministry of Health, 2001; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011a). Palliative care in the community is also subsidised for those wishing to die at home, which not only improves care options but also provides palliative-care career pathways for community nurses (Kralik and Van Loon, 2011; Ministry of Health, 2001).

Since the majority of older people choose to ‘age in place’ at home in the community (Department of Health and Ageing, 2010; Ministry of Social Development, 2001), the major work of community nurses is the care of older people with one or more chronic illnesses. Community nurses need to employ different strategies to support older people within a range of new services being offered by government and non-government agencies (Ellis and others, 2010). In 2009/10 the Australian government’s budget extended access to the MBS and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for nurse practitioners (NPs), and while NPs comprise only a small proportion of the total community-based nursing workforce, this initiative represents a significant step forwards in recognising the knowledge, skills and expertise that nursing brings to the provision of primary healthcare services (Commonwealth of Australia, 2009).

The scope of community nursing is expanding to take account of the nursing context; the nurse’s professional education, qualifications and competency levels; client health needs; and service provider policies (Kralik and Van Loon, 2011). Nevertheless, the community nursing role remains weighted towards health and wellness of communities based on primary healthcare principles, which focus on strengthening community reserves (Griffiths, 2008) and accommodating the complex factors associated with the older person’s and family’s life transitions (Heath and Phair, 2009). Figure 43-6 illustrates some of the work that community nurses engage in: health-promoting activities that enable the older person to optimise health, wellbeing and independence in later life; curative and rehabilitative dimensions that focus on functional and psychological recovery from illness or injury; facilitating self-care and enabling effective management of chronic conditions; providing care for those who become frail and have limited self-care capacity; and palliative and end-of-life care (Tolson and others, 2011). In each of these roles the community nurse, the older person and their carer/support network work as a team, being focused on the older person’s needs and self-determined goals, not the nurse’s goals (National Ageing Research Institute, 2006; Omeri and Malcolm, 2004).

Advanced community nursing

The vignettes below identify the range of services provided by NPs, ones which rely on a great deal of initiative as well as collaboration with other healthcare providers, and culturally sensitive partnerships with health consumers and the community, to provide the very best healthcare services possible with limited resources.

Vignette 1—a nurse practitioner in rural New Zealand

I see my role first and foremost to empower people in my community to have the best health possible. The most important support for this work comes from developing and maintaining good relationships with others, because they are essential to all aspects of my role—including community outreach clinics, home visits, connecting with people at community meeting places, preschools, seeing patients at medical clinics and as part of a multidisciplinary team. I provide primary healthcare to the whole community with a special focus on reducing health inequity and, as a Māori NP, I have a special connection to our Māori population and familiarity with how traditional values and beliefs influence our lives.

I don’t really have a typical day as such, but here is what one day might involve. I would usually begin at 8am or earlier, depending on how far I have to travel to my first appointment. Before heading off I have lab results to review and follow-up actions from previous patient visits. Usually the morning then involves providing outreach clinics at a medical centre, schools, preschools, community centres, marae [Māori meeting houses] or home visits. I have to be very well prepared for my day ahead to allow for travelling long distances, coping with bad weather that can cause flooding and road damage and being flexible enough to respond to a whole range of health needs I could encounter at any time. My afternoons typically involve more outreach visits into rural communities providing screening for health risks, support for self-management of chronic illness and wellness support for community groups. If I’m not doing outreach, I’ll be holding clinics at a medical centre where I see patients, usually individually, for ongoing chronic illness support or with acute health problems. Also, I meet with nurses either one-to-one for clinical supervision [mentoring] or case management discussions and consult regularly with GPs for case reviews, advice and clinical supervision. All of this work depends on good communication, established networks and careful planning ahead.

My skills and knowledge have to be broad-based because of the wide age range of people I see, some with multiple health problems and needs. My clinical judgment relies on competent assessment of health needs for individuals and communities, efficient laboratory diagnostic services, access to good evidence for practice and effective collegial relationships, including other healthcare providers, social services and pharmacists. Most of all, though, it is engagement with my community that enables me to empower people to make health gains and to build strong networks across the region that keeps me informed of opportunities to work with groups and individuals and to know how best to support them.

Vignette 2—an aged-care nurse practitioner in urban Australia

I have been working as a Nurse Practitioner, Aged Care (Cognition) within the metropolitan region for the ARV Retirement Villages for the last three years. ARV has approximately 5000 clients spread across all regions of central and wider Sydney, living in the general community receiving ‘care packages’, in independent living units or within 19 residential aged-care facilities. My initial brief was to develop an organisational strategy that would address the growing incidence of dementia. The key elements included raising awareness of dementia, reducing the stigma, highlighting risk factors, promoting better health strategies, achieving early identification, supporting care and enhancing staff skills. In order to do this we established our service, known as BrightMinds©, which initially consisted of two pilot sites. Since starting, the service has grown and is now an organisational-wide strategy, with an additional clinical nurse consultant (CNC) and clinical nurse specialist (CNS) to assist with service delivery.

My usual day includes not only team support, which can be direct, online or over the phone, but also direct clinical consultations. Our services are frequently called upon by people experiencing difficulty with memory as well as by their families, friends, staff, community groups and other healthcare professionals. A clinical consultation includes compiling a detailed health and lifestyle history, reviewing pathology and medication and completing cognitive testing. Dependent on the outcome, liaising with the GP and often a specialist is required to facilitate access to first-line treatment, which usually includes acetyl cholinesterase inhibitors. As an NP working in cognition I am constantly searching for underlying causes of cognitive decline, and it is rewarding to find a reversible delirium or a treatable depression, and know you have made a difference. When it is dementia I can still help, sometimes with practical tips, carer support or advice regarding treatment regimens. Most weeks involve presenting to a forum or group to discuss recent advances in research, novel treatment options or behavioural interventions. It is an exciting role that is continuing to grow and offers new and exciting opportunities, particularly in the field of research. Hopefully, we will have a major breakthrough soon, and our team is ready and prepared for paving the way.

Competencies for community nursing

Competencies for community nursing occur at three levels: the healthcare system; the health organisation and services; and the client and family carer/support network (Australian Nursing Federation, 2009). The dual role of providing primary healthcare (health education, disease prevention, health promotion) and providing clinical care recognises the interconnected relationship between the nurse, the person and their sociocultural and living environment. Community nursing recognises this symbiotic relationship in which the person takes ownership of a lifestyle aimed at minimising disease risk and maintaining or improving health outcomes, but is affected by the physical, political, social and cultural environment, or community, in which they live.

Promoting health behaviours can sometimes require the community nurse to help the person and their carer to overcome barriers arising from the person’s social situation, such as low social opportunities and emotional support and poor access to some health services, education, employment, income, food supplies and social services (National Ageing Research Institute, 2006). This was identified as a major issue when providing community nursing services to Australian Indigenous people. It is, therefore, essential that the community nurse is culturally sensitive to the client’s and family’s unique needs and circumstances, and is culturally competent in all dealings with individuals and groups requiring community nursing support.

Cultural competence

As population mobility has increased the cultural diversity of populations worldwide, healthcare services have been more aware of the need to employ culturally competent staff (Betancourt and others, 2005; Callister, 2005; Carrillo and others, 1999). Nurses work with people who hold a variety of beliefs about health, illness and treatment and who will also have different thresholds for seeking healthcare (Betancourt and others, 2005; Leishman, 2004). Even though health outcomes research has been sparse in this respect, education for cultural competence in healthcare staff is expected to reduce health disparities and improve healthcare effectiveness (Betancourt and others, 2005; Callister, 2005; Carrillo and others, 1999). From a Māori client’s point of view, healthcare that has been designed to be culturally appropriate, affordable and accessible gains a high level of client satisfaction (Maniapoto and Gribben, 2003). Cultural competence is vitally important in primary healthcare and has special meaning in New Zealand in light of the Treaty of Waitangi and health inequity for Māori.

Primary healthcare involves effective and meaningful relationships between clients/families and clinicians that are reliant on cultural competence. Healthcare is judged by the client as culturally safe in terms of their own experience. Nurses are at the frontline of primary healthcare where cultural safety is pivotal to clients’ experience of healthcare (Wilson and Grant, 2008). The Treaty of Waitangi acknowledges the special status of Māori in New Zealand and is embedded into health law, whereby culturally safe care is required and consistent with the principles of partnership, participation and protection. The application of partnership, participation and protection in healthcare requires the knowledge, skills and attitudes of cultural safety. Cultural safety denounces the uncritical aggregation of clients of similar cultures into groups with common values, customs, beliefs and behaviours (Carrillo and others, 1999). Culturally safe nursing practice is informed by an analysis of the politics inherent in the systematic mechanisms of marginalisation, poverty and inequity for different community groups (Ramsden, 2002).

Providing culturally safe healthcare is particularly relevant for the many individuals who access the Australian primary healthcare system, which services more than 200 different cultural and language health populations (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010), and for the growing number of international refugees living in Australia. This is an area requiring considerable improvement in the broad spectrum of Australian health services. Culturally competent nursing care is similarly essential in the care of older Indigenous Australians, given the unique needs and circumstances of the many hundreds of Indigenous nations, with their own languages, cultural mores and community structures. Developing nursing services that are attuned to local Indigenous circumstances and customs will demand more than simply enabling access to the full spectrum of health interventions; it requires nurses to work effectively with an expanded Indigenous workforce. Culturally sensitive Indigenous nursing services require broad, health-affirming approaches that are attuned to the circumstances and priorities of each community, initiatives that support empowerment at individual, family and community levels, and the willingness of nurses to recognise and challenge underlying social disadvantage and injustice experienced by their indigenous clients and families (Hunter, 2007).

Nursing competencies for integrated care

Wolff and Boult (2005) have identified nine components that constitute a comprehensive system of community care service, one that is ideally suited to the community nurse role. This system includes client and carer evaluation, individual care planning, evidence-based decision making, consumer empowerment through joint decision making, promotion of healthy lifestyles, coordination across multiple conditions, coordination across provider settings, carer support and education and facilitating consumer access to health resources. In order to fulfil this comprehensive role, community nurses must arm themselves with the right sets of knowledge and skills.

Community nurses must be able to coordinate services at the micro level (nurses, other healthcare staff and client/carer), meso level (services and organisations) and macro level (healthcare system) (Davies and others, 2006). Across these levels, the nurse must focus on processes to facilitate coordination (e.g. communication strategies, support for service providers and consumers) and focus on building structures for coordinating activities (e.g. shared information systems, referral proforma, care plans and decision support systems) (Rosenthal and others, 2006). A proven strategy for improving client and carer outcomes involves strengthening the relationships between the community service, GP services and acute care services, and employing a shared client care plan and records tools to actively support coordination (Davies and others, 2006).

Consequently, as previously identified the community nurse must recognise the broader context of health from one that focuses on the biological cause of illness, by enabling the older person and their family/support networks to become actively involved in a range of health maintenance processes. This requires the nurse to have excellent assessment skills and a high capacity for communicating knowledge across the healthcare continuum. This will be especially important when having to negotiate competing value systems in provision of professional, equitable and ethical care to members of different generations, multiple cultures and broadly ranging socioeconomic backgrounds (National Ageing Research Institute, 2006).

Having a good knowledge of the available range of community-based services and developing effective partnerships with healthcare consumers and service providers is required for a number of key community nursing roles: referral procedures; brokering services for older persons and carers; providing short- and long-term case management; and working with the older person and their carer to develop care plans aimed at self-management. Partner services will include mental health, ageing, palliative and disability services; continence, wound and stoma care services; drug, alcohol and sexual health services; carer respite and community support services; and specialist treatment services (Kralik and Van Loon, 2011).

At the individual client level, the community nurse requires a good working knowledge of the unique healthcare changes occurring in the older person and the impact of these on the person’s physical, psychological and social functioning, in order to provide safe and effective care. In the first instance the nurse must learn to recognise and pay attention to the key features of altered clinical presentation that can occur in the older person, such as the disease, multiple pathology, frailty, geriatric syndromes and cascading responses to physical, social or emotional factors that can lead to severe illness or even death (National Ageing Research Institute, 2006). Common, potentially serious and debilitating conditions in older age such as delirium, falls, pain, urinary incontinence and constipation, low body mass index and sensory impairment are examples of geriatric syndromes that lead to poor outcomes (Tolson and others, 2011). These syndromes are indicative of a change in health status but frequently do not represent the specific disease condition/s causing that change.

For this reason the community nurse requires an advanced knowledge to identify the ‘atypical’ signs of illness that are complicated by multiple pathology in the older person and even conditions that are relatively minor but debilitating, such as painful feet. Unless the community nurse pays attention to these early signs of illness, they can have a cumulative effect on the older person’s overall condition, to the extent that the person can rapidly lose functional and cognitive capacity (Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council, 2005). As well, the community nurse must acknowledge that for each separate condition the older person might be prescribed different medicines. The resulting polypharmacy can lead to toxic drug reactions and interactions, which can lead to further loss of functional and cognitive capacity (Tolson and others, 2011). Given the complex factors involved in chronic illness management, the community nurse will need to help the older person to build up their self-efficacy (confidence) for self-management (Lorig and others, 2001). This can be facilitated by providing education and supervision in self-management support and treatments, helping the person to set self-care goals and helping them to gain support from others with similar chronic illnesses through links to support and self-help groups (Bodenheimer and others, 2002a; Wertenberger and others, 2006).

In this respect the community nurse must provide strong leadership in pursuing a strengths-based approach to their practice, where the emphasis is on fostering confidence in self-management; building trust and positive relationships between the person, their support network and the nurse; facilitating the older person’s and their carer’s access to relevant services; and using evidence to inform the health consumer, rather than to control (National Ageing Research Institute, 2006). The leadership qualities of an effective community nurse cover four main domains: personal values and character traits; responses and actions befitting a respected leader; high-level tacit and applied knowledge; and client-/colleague-centred professional behaviour (Kralik and Van Loon, 2011). Such leadership qualities are values-based, visionary, creative and inspiring (Stanley, 2006).

Quality community nursing services for older people

Challenges for community nurses

The challenge for community nurses is how to support positive healthcare outcomes for older people within a resource-pressured healthcare system. Community nurses need to reconceptualise the way they provide care for older people who generally have one or more chronic illnesses and high health service needs and expectations. As previously identified, policies aimed at shorter hospital episodes of care, including an increasing number of day-surgery procedures, means that at discharge older people require greater and more-complex care from community nurses (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011a). In addition, some treatment and nursing care that has traditionally been provided in a hospital setting for people with a chronic illness is increasingly being provided in the community (e.g. dialysis and chemotherapy). Other factors over the last two decades, such as changes to mental health services, have increased the demand on community nursing services to support people with complex health needs (Commonwealth of Australia, 2009).

Growing knowledge of what constitutes best-practice care, at both the consumer and the healthcare provider level, combined with new technologies which can change the way services are provided, have meant that expectations regarding health and the healthcare system have risen. Consumer demand is having more impact than ever on the community healthcare sector (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011a; Ministry of Health, 2001). Australian and New Zealand governments are grappling with how best to address these growing consumer needs and demands.

Given the projected health expenditure trends associated with population ageing, an important goal for healthcare reform in both countries is the long-term financial sustainability of a comprehensive primary healthcare system. One noticeable impact on community healthcare services is the ageing of the healthcare workforce, including nurses, and an exponential rise in retirement numbers in recent years. The average age of people employed in healthcare occupations in 2006 was 45 years, three years older than other people in the workforce (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010). Combined with rising consumer need and expectations, the loss of experienced nurses from the workforce leads to growing pressure on existing services, and leaves more healthcare consumers with gaps in care.

Older people with one or more chronic illnesses can miss out on necessary community care in a complex and fragmented healthcare system where access depends on the availability of services, the geographical location of suitable services and an individual’s level of health insurance cover and ability to pay for services (Commonwealth of Australia, 2009; Ministry of Health, 2003). In some respects, fragmentation in health service provision occurs because of the variety of funding mechanisms and lack of integration, coordination and collaboration between different healthcare systems, including community nursing and acute care nursing services. As well, the traditional organisation of community-based healthcare, which separates general practice medical care and more-specialised health services, does not always meet healthcare consumer needs. Diabetes, for example, has been identified as a typical condition that requires the services of a wide range of healthcare practitioners, such as GPs, nurses, diabetes educators and specialist health staff such as podiatrists, endocrinologists, dietitians, nephrologists, neurologists, pharmacists and cardiologists. All these services are needed to ensure the best health outcomes possible for the person with diabetes; however, the person may not have access to all these services, especially in rural and remote areas, and health service providers may not be aware of the scope and range of services the person is accessing (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011a).