Chapter 20 Conception to adolescence

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Identify basic principles of growth and development.

• Discuss factors influencing growth and development.

• Discuss physiological and psychosocial health concerns during transition from fetus to neonate.

• Describe characteristics of physical growth of the fetal child and from birth to adolescence.

• Describe cognitive and psychosocial development from birth to adolescence.

• Describe the interactions that occur between parent and child.

• Describe variables influencing how children learn about and perceive their health status.

• Explain the role of play in the development of the child.

• Identify factors that contribute to self-esteem in young people.

• Describe the influence of the school environment on the development of the child.

• Plan culturally appropriate health promotion activities for children of all backgrounds.

• Discuss ways in which the nurse can help parents meet their children’s developmental needs.

Understanding children and their growth and development is essential to promoting, maintaining and restoring health. There are recognised patterns or stages of developmental change that occur throughout infancy, childhood and adolescence. Although there are recognisable age-related patterns with associated capabilities, it is important to keep in mind that there is a wide range in the times at which individuals will meet these capabilities. The ranges that are set out are guides only, rather than a prescription. Having a clear understanding of patterns of developmental change helps the nurse to plan, deliver and support age-appropriate and individualised care.

Nursing practice based on principles of growth and development is organised and directed at helping children and their families respond to changing internal and external conditions. This chapter discusses principles and concepts of growth and development and their application to health promotion from conception to adolescence.

Growth and development

Human growth and development are orderly, predictable processes beginning with conception and continuing until death (see Chapter 22). The pace and behaviour of this progression are highly individual. For example, children learn to walk before they can run, but one child may walk at 10 months while another may not walk until 15 months of age.

The ability to progress through each developmental phase influences the holistic health of the individual. The success or failure experienced within a phase may affect the ability to complete subsequent phases. If an individual experiences repeated developmental failures, problems may result. However, if the individual experiences repeated successes, capabilities that maintain and promote health result. A child not learning to walk by 18 or 20 months, for example, demonstrates delayed gross motor ability that slows exploration and manipulation of the environment. A child walking by 10 months is able to explore and find stimulation in the environment, thereby enhancing learning.

Definitions

Growth and development are synchronous processes that are interdependent in the healthy individual. Growth, development, maturation and differentiation depend on a sequence of endocrine, genetic, constitutional, environmental and nutritional influences (Glasper and Richardson, 2010). A person experiences growth or quantitative change, and developmental or qualitative change.

Physical growth

Physical growth is the quantitative, or measurable, aspect of an individual’s increase in physical measurements. Measurable growth indicators include changes in height, weight, teeth, skeletal structures and sexual characteristics. For example, children generally double their birthweight by 5 months of age and their birth height by 36 months.

Development

Development occurs gradually over time. The processes of development are cumulative, as a function of increasing age and mastery of small skills. They are reflected in behaviours that enable the individual to be self-regulating. For instance, an observable change for preschoolers is participating in telephone conversations with their parents. Before achieving this capability, they must develop a small vocabulary, learn to put words together in phrases and sentences and develop a cognitive understanding of object permanence (that a person or object out of sight still exists).

Maturation

Maturation is the process of ageing. The individual begins to adapt and show capability in new situations. Maturation can be described as a more qualitative type of change. It involves an individual’s biological ability, physiological condition and desire to learn more-mature behaviour. To mature, the individual may have to relinquish previous behaviour and learning, integrate new patterns into existing behaviour, or both. Maturation influences the sequence and timing of the changes associated with growth and development. For example, the infant relinquishes crawling for walking because walking permits more-extensive investigation of the environment and more learning. However, the infant cannot walk until the biological ability and structures to perform the action (i.e. increased muscle cells and tone) have developed.

Differentiation

Differentiation is the process by which cells and structures become modified and develop more-refined characteristics. It is a simple-to-complex development of activities and functions. Embryonic cells begin as vague and undifferentiated and develop into complex, highly diversified cells, tissues and organs.

Stages of growth and development

Human growth and development are continuous and intricate, complex processes that are often divided into stages organised by age groups, such as from conception to adolescence (Box 20-1). Although this chronological division is arbitrary, it is based on the timing and sequence of developmental tasks that the child must accomplish to progress to another stage.

BOX 20-1 DEVELOPMENTAL AGE PERIODS

PRENATAL PERIOD: CONCEPTION TO BIRTH

Germinal: Conception to approximately 2 weeks

A rapid growth rate and total dependency make this one of the most crucial periods in the developmental process. The relationship between maternal health and certain manifestations in the newborn emphasises the importance of adequate prenatal care to the health and wellbeing of the infant.

INFANCY PERIOD: BIRTH TO 12 OR 18 MONTHS

Infancy: 1 to approximately 12 months

The infancy period is one of rapid motor, cognitive and social development. Through mutuality with the caregiver (parent), the infant establishes a basic trust in the world and the foundation for future interpersonal relationships. The critical first month of life, although part of the infancy period, is often differentiated from the remainder because of the major physical adjustments to extrauterine existence and the psychological adjustment of the parent.

EARLY CHILDHOOD: 1 TO 6 YEARS

This period, which extends from the time the children attain upright locomotion until they enter school, is characterised by intense activity and discovery. It is a time of marked physical and personality development. Motor development advances steadily. Children at this age acquire language and wider social relationships, learn role standards, gain self-control and mastery, develop increasing awareness of dependence and independence and begin to develop a self-concept.

MIDDLE CHILDHOOD: 6 TO 11 OR 12 YEARS

Frequently referred to as the ‘school age’, this period of development is one in which the child is directed away from the family group and is centred around the wider world of peer relationships. There is steady advancement in physical, mental and social development with emphasis on developing skill competencies. Social cooperation and early moral development take on more importance, with relevance for later life stages. This is a critical period in the development of a self-concept.

LATER CHILDHOOD: 11 TO 19 YEARS

Adolescence: 13 to approximately 18 years

The period of rapid maturation and change known as adolescence is considered to be a transitional period that begins at the onset of puberty and extends to the point of entry into the adult world—usually at the end of secondary school. Biological and personality maturation are accompanied by physical and emotional turmoil, and there is redefining of the self-concept. In the late adolescent period the child begins to internalise all previously learned values and to focus on an individual rather than a group identity.

Adapted from Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D 2011 Wong’s Nursing care of infants and children, ed 9. St Louis, Mosby.

Critical periods of development

Stages of growth and development involve the concept of critical periods of development. A critical period is a specific span of time during which the environment has its greatest impact on the individual. During these critical periods, some form of sensory stimulation is necessary for developmental progression. Without stimulation, task completion is difficult or unattainable. For example, the toddler who has not been encouraged to learn to walk during a set time may have difficulty learning to walk at another time. Therefore, developmental progression depends on the timing and degree of stimulation as well as on the readiness to be stimulated by the environment. A stimulus provided too early may not be useful. For example, an 18-month-old child cannot learn to write, regardless of the intensity of the stimuli.

Major factors influencing growth and development

The human being is a complex, open system influenced by natural forces from within and from the environment, as shown in Table 20-1. Interaction between these forces affects development.

TABLE 20-1 MAJOR FACTORS INFLUENCING GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

Selecting a developmental framework for nursing

Providing developmentally appropriate nursing care is easier when planning is based on a theoretical framework (see Chapter 19). An organised, systematic approach ensures that the child’s needs are assessed and met by the plan of care. If nursing care is delivered only as a series of isolated actions, some of the child’s developmental needs may be overlooked. A developmental approach encourages organised care directed at the child’s current level of functioning to motivate self-direction and health promotion. For example, nurses might encourage toddlers to feed themselves to advance their developing independence and thus promote their sense of autonomy. Or, understanding an adolescent’s need to be independent should prompt the nurse to establish a contract about the care plan and its implementation.

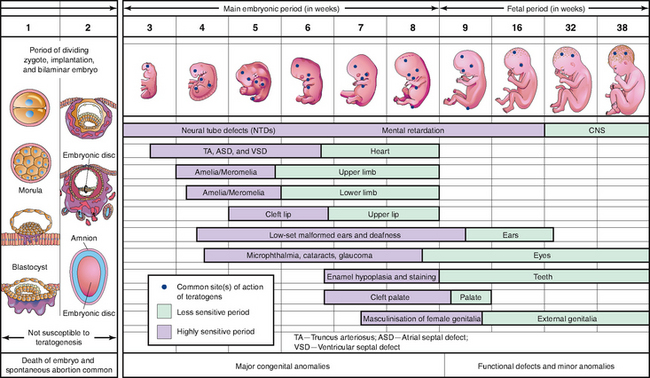

Conception

From the moment of conception, human development proceeds at a predictable and rapid rate. Intrauterine health problems are caused by both genetic and environmental factors. During the prenatal period, the embryo grows from a single cell to a complex, physiological being. All major organ systems develop in-utero, with some functioning before birth (Figure 20-1). The psychosocial being also begins to emerge during gestation. You might be interested to know that Als (1986) formulated a model, called the Model of Synactive Organization Behavioral Development, by examining the complex relationships between growth and development observed in the behaviours of preterm infants. It is not within the scope of this chapter to explore Als’s (1986) model in detail; it is, however, important to note that the application of this model in clinical practice has a fundamental emphasis on planning, delivering and supporting age-appropriate and individualised care, which is the message you will read about throughout this chapter.

FIGURE 20-1 Critical periods in human development (mauve denotes highly sensitive periods when major birth defects may be produced).

From Moore KL, Persaud TVN 2003 The developing human: clinically oriented embryology, ed 7. Philadelphia, Saunders.

Intrauterine life

The following information about intrauterine life provides a basic overview of the timeline of events and major issues for you to consider. After you have read through this section you might like to browse the internet, as there are many interesting websites that have great interactive graphics showing all aspects of conception, fetal growth and development, birthing and the newborn’s transition to extrauterine life.

To begin, it must be acknowledged that women were calculating their due date based on the cycles of the moon and successfully giving birth for many thousands of years before modern medicine intervened. That being said, intrauterine life that reaches full term lasts 10 lunar or 9 calendar months, which equates to 40 weeks or 280 days. The length of pregnancy is calculated using Nägele’s rule, which counts back 3 months from the last menstrual period (LMP) then adds 7 days. Interestingly, with the almost routine ultrasound dating of recent times, research has shown that Nägele’s rule is three days short, prompting some to suggest the rule be amended (Grigg, 2010).

Only one sperm penetrates the ovum. Fertilisation of the ovum takes place in the outer third of the fallopian tube and occurs within 24 hours of the ovum’s release. Once fertilisation takes place, the material from both cell nuclei unites. The organism then has its full genetic complement in one pair of sex chromosomes and 22 pairs of autosomal chromosomes. The ovum and the sperm each contribute one chromosome to each pair. It is through this mechanism that genetically programmed diseases (such as Down syndrome) and genetically determined characteristics (such as eye colour) are transmitted from parent to child.

The fertilised ovum, or zygote, passes through the fallopian tube to the uterus within 3–4 days. During this time the zygote continues to divide. Within 3 days a solid ball of cells, the morula, has formed. The morula continues to develop and forms a central cavity, or blastocyst. Even at this early stage of development, cells begin to differentiate in structure and function. Cells at one end of the blastocyst develop into the embryo, and those at the opposite end form the placenta. Between days 6 and 10, enzymes are secreted that allow the blastocyst to burrow into the endometrium and become completely covered. This portion of the process is known as implantation. Chorionic villi, finger-like projections, develop to obtain oxygen and nutrition from the maternal blood supply and dispose of carbon dioxide and waste products.

Before implantation, the embryo is relatively protected from the external environment, but with implantation it becomes more vulnerable to the larger maternal environment via exchange of materials through the placenta. The placenta produces essential hormones that help maintain the pregnancy. Because the placenta is extremely porous, noxious materials such as viruses and drugs can also pass from mother to child. The effect of noxious agents on the unborn child depends on the developmental stage in which exposure takes place, with the embryonic stage being the most crucial. The embryonic stage lasts from day 15 until approximately 8 weeks after conception; this is a crucial stage in the development of organ systems and the main external features. Following the embryonic stage, the developing child is known as a fetus. The period of gestation is often divided into three periods called trimesters.

First trimester

During the first trimester (the first three calendar months), the uterus continues to be a pelvic organ. After implantation, fetal cells continue to differentiate and develop into essential organ systems. These processes of cellular change (differentiation) and staged organ change (development) occur at different rates and times, and each organ is extremely vulnerable to environmental assault. Interference with growth can cause the congenital absence of an organ system or extensive structural or functional alterations. Because several organ systems develop at the same time, disruption of one system often occurs with disruption of others. Figure 20-1 shows the approximate times of critical differentiation for some of the major organ systems and their overlapping of development. Towards the end of the first trimester, it is possible to elicit fetal heart tones (FHTs) by fetoscope or ultrasound.

HEALTH PROMOTION

Health promotion is an important aspect of nursing/midwifery care at this time, as there are many agents, referred to as teratogens, capable of producing adverse effects in the fetus. Some teratogens produce defects only if the fetus is exposed to the agent when the vulnerable organ is developing. The nurse or midwife provides education to the mother about avoiding exposure to teratogenic agents. One such teratogen is the rubella or German measles virus, which can cause spontaneous abortion, stillbirth or birth defects of the eyes, ears and heart, mainly when exposure is in the first trimester.

Many drugs are teratogenic during rapid organ growth (organogenesis) in the first trimester. Past and present use of home remedies, herbs, and prescription, over-the-counter and illegal drugs must be carefully assessed. Barbiturates, anticoagulants, antimicrobials, alcohol, cancer chemotherapeutics and hydantoin anticonvulsants are only a few of the chemical agents associated with fetal abnormalities, and many other agents are still under investigation. The benefits of any drug needed to maintain the mother’s health must be weighed against potential harm to the fetus. Abuse of drugs such as cocaine, LSD, heroin, ecstasy or amphetamines may result in significant fetal compromise (Homer, 2006). Smoking has been shown to reduce birthweight and increase the incidence of fetal and neonatal death (Homer, 2006). Infants exposed prenatally to alcohol can develop fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), fetal alcohol effect (FAE) or an alcohol-related birth defect (ARBD) (Homer, 2006). Caffeine does cross the placenta, and while a small intake has been found to have no ill effect in a well and healthy woman (Kuczkowski, 2009), the pregnant mother should be encouraged to limit her intake and discuss the potential effects with her doctor, nurse or midwife. With this knowledge, the nurse or midwife can explore lifestyle changes that can help a pregnant woman protect the health of her fetus.

The diet of a woman both before and during pregnancy has a significant effect on the development of the fetus in-utero. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that mothers who eat well have fewer complications of pregnancy and childbirth and bear healthier babies than those with poor nutritional intake (Elias, 2006). An adequate folic acid intake is recommended for any woman contemplating pregnancy (see Box 20-2). As there are consequences of maternal malnutrition for both maternal wellbeing and fetal development, attention to assessment of women’s nutritional status during pregnancy is important.

BOX 20-2 CLIENT TEACHING ABOUT FOLIC ACID FOR WOMEN CONTEMPLATING PREGNANCY

OBJECTIVES

1. Clients with no family history of neural tube defects will consume 0.5 mg of folic acid every day for 1 month prior to conception and for the first 3 months of pregnancy.

2. Clients with a family history of neural tube defects will increase that dose to 5 mg.

3. Clients on anticonvulsants should take folic acid supplements only under the supervision and monitoring of a specialist doctor.

TEACHING STRATEGIES

• Educate females of childbearing age about the benefits of folic acid to the developing fetus.

• Discuss the need for women to have an adequate daily intake of folic acid because the moment of conception is not always known. Folic acid is a water-soluble vitamin and is readily excreted in the urine.

• Encourage consumption of the appropriate amount of folic acid daily. This amount may be consumed in food sources; however, adolescents are usually deficient. Deficiency is not related to socioeconomic status.

• Discuss foods rich in folic acid, such as green leafy vegetables, liver, kidney and asparagus. More-limited amounts may be found in milk, poultry and eggs.

Adapted from: Public Health Association of Australia Inc 2006 Periconceptual folate and the prevention of neural tube defects. Online. Available at www.phaa.net.au/documents/policy/policy_child_neural_tube.pdf, 6 Dec 2011; New South Wales Department of Health 2005 Folic acid and neural tube defects, Doc. no. PD2005_066. Sydney, NSW Department of Health. Online. Available at www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/PD/2005/pdf/PD2005_066.pdf 6 Dec 2011.

Second trimester

Maternal physical changes during the second trimester (from the end of month 3 to the end of month 6) are concerned with the uterus becoming an abdominal organ as the fetus grows in size. Measurement of the height of the uterus, above the symphysis pubis, is one indicator of fetal growth. The height of the uterus can also indicate approximate gestational age and high-risk situations. The fundus, or top of the uterus, typically measures 1 cm for each week of gestation up to 36 weeks; a 16-week gestation should measure 16 cm above the top of the symphysis pubis. Between 16 and 20 weeks, the mother begins to feel fetal movement. This feeling of life is referred to as quickening.

Fetal physical changes involve some organ systems continuing basic development while the functional capabilities of others are refined. By the end of the sixth month, most organ systems are complete and can function. The fetus is therefore considered viable, or capable of life outside the uterus, if given intensive environmental support. The fetus weighs about 0.7 kg and is approximately 30 cm long. Fingers and toes are differentiated, rudimentary kidneys function and the sex of the fetus can be determined. The fetus is covered with vernix caseosa, a cheese-like substance coating the skin. Lanugo, or fine hair, covers most of the body. These substances protect the thin, fragile skin and decrease in amount as the pregnancy nears its completion; thus infants born before 38 weeks of gestation have more of these protective coverings than full-term infants.

HEALTH PROMOTION

Health promotion in the second trimester continues the education program established in the first trimester, but with a greater emphasis on how the fetus is growing. The fetal heartbeat becomes audible to stethoscope auscultation, and the mother becomes aware of fetal movement. Both events are highly significant to the parents because they provide tangible evidence of the pregnancy and reassure them that the fetus is alive.

During this period women often focus on planning for the birth, personal safety, and health and appearance. Nurses and midwives can help women as they make these preparations, during prenatal visits and in prenatal classes. This is often a good time for education about gestational events and appropriate maternal rest, nutrition, dental care, physical activity, posture and employment. It is also a good time to help the woman prepare for life at home with a new baby by discussing infant cares such as breastfeeding, settling and sleep, as well as changing family dynamics.

Because of dramatic changes occurring in the renal system, it is possible for a mother to have an asymptomatic urinary tract infection. Urinary tract infections greatly increase the risk of preterm labour; therefore, voiding habits and issues should be discussed with the mother during this time.

Childbirth is always a significant and challenging event for women. It is important for women to understand how midwives and medical staff will help their labour and birth and to comprehend the potential complications and the physical signs and symptoms that may indicate complications. Understanding these challenges helps women to take appropriate actions in response to any change in their health status.

Preterm birth is a further difficult aspect of pregnancy. Advances in medical knowledge and treatments mean that it is now possible for 500 g babies of 24–26 weeks of gestation to survive; however, there may be significant risk of morbidity. Prematurity is identified as any infant born before 37 weeks of gestation. Causes for prematurity are poorly understood, and may be the result of maternal, fetal or placental problems. Maternal risk factors include physiological stresses such as renal and cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, or uterine and cervical abnormalities. Mothers with mental health problems or those living in poverty and receiving poor prenatal care are also at risk of experiencing a preterm birth. Multiple pregnancies and fetal infections are two of the potential fetal factors for prematurity. Placental factors include abruptio placentae and placenta praevia (Griffiths and Thorogood, 2006). Tocolysis, using the beta-adrenergic receptor agents ritodrine hydrochloride, salbutamol and terbutaline sulfate, may be implemented to temporarily inhibit labour in the case of preterm labour. Although after 34 weeks of gestation the fetus is viable, and with the high standards of neonatal care in Australia, it is reasonable to allow labour to progress (Thorogood and Donaldson, 2006).

Third trimester

Physical changes during the last 3 months of intrauterine life involve the fetus growing to approximately 50 cm in length. Subcutaneous fat is stored, and weight increases to between 3.2 and 3.4 kg. The skin thickens, lanugo begins to disappear and the fetal body becomes rounder and fuller.

A tremendous spurt in brain growth begins during this trimester and lasts well into the first few years of life. The central nervous system has established its total number of neurons and connections between neurons, and myelination of nerve fibres progresses at a rapid rate.

At the end of the third trimester, the healthy fetus is physically able to make the transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life. The cardiac system can change its circulation to end bypassing of the lungs. The lungs are capable of maintaining the inflated state for gas exchange. The primitive temperature maintenance systems, reflexes and sensory organs are ready for use.

HEALTH PROMOTION

As far as health promotion is concerned, exposure to noxious agents and the absence of essential nutrients can cause damage to the central nervous system and result in alteration of high-level cognitive functions. The nurse/midwife can increase the mother’s awareness of these dangers through counselling, and can help her evaluate the quality of her nutritional intake. Thoughts of delivering a healthy baby are foremost in the mother’s mind as she focuses on preparing her mind and body for the delivery. Parents often seek information regarding the childbirth process and breastfeeding from childbirth education groups. Depending on the mother’s location, many different types of childbirth education groups are available. Some groups are for first-time parents and may focus on the adolescent or the older (35 years or more) mother. Other classes may focus on the repeat mother who needs a refresher course, the caesarean section mother or the mother who wants to attempt a vaginal birth after a caesarean section (VBAC). Because some areas may have limited access to childbirth classes, parents should be encouraged to investigate local classes early.

The majority of babies are born in hospitals. In recent years, many hospitals have attempted to become more family-centred, welcoming birth partners and helpers and providing spaces with home-like furnishings. A very small percentage of mothers choose to deliver at home. Control over the birth process seems to be the most attractive factor for mothers who do not believe they will have choices in a hospital setting. Another advantage is that the entire family, or other people close to the family, can be part of the event. Most home births occur with low-risk pregnancies. A registered and experienced midwife supports home births. An open relationship with medical and hospital maternity services is necessary should hospitalisation and obstetric intervention become necessary.

Caesarean section rates have increased dramatically over recent years, with the percentage of privately insured women leading this trend (NSW Department of Health, 2011). There is little evidence to suggest that higher intervention rates in normal childbirth lead to lower perinatal morbidity and mortality. There is, however, growing concern about the implications of this trend for maternal and infant outcomes, and its impact on future service provision; with an anticipated exponential growth in caesarean section rates in subsequent pregnancies. In Australia there is now a coordinated movement to increase the choices of childbearing women through the provision of midwifery-led services; midwifery-led services have been in place in New Zealand for many years. For more information on the models of midwifery care in Australia you might like to consult the text Midwifery: preparation for practice (Pairman and others, 2010).

Relationships between prenatal events and cognitive development are difficult to establish. However, periods of diminished oxygen (anoxia) during fetal life are known to cause deficits in later cognitive functioning, and inadequate prenatal nutrition has been associated with lower brain weight. The large volume of research on developmental outcomes in low-birthweight (LBW) and very-low-birthweight (VLBW) infants indicates that these infants have an increased risk of learning disorders, school failures, temperament problems, neurological and motor impairment and developmental delays. Many additional factors affect an infant’s temperament. Such factors include prenatal exposure to drugs, maternal analgesia during labour, and length of gestation. The Cochrane Collaboration will be able to provide you with a vast amount of information on developmental outcomes for LBW and VLBW infants (see Online resources).

Little information is available about the relationship between prenatal factors and the child’s psychosocial development. Some authorities believe that nutritional deficiencies of the fetus can significantly influence later psychosocial development. This is especially true if maternal malnutrition occurs during the period of rapid brain growth, because a permanent reduction in brain cells may occur (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009).

Transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life

The transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life requires rapid changes in the newborn. The nurse/midwife assesses the newborn’s ability to make these changes and plans for appropriate interventions. Gestational age and development, exposure to depressant drugs before or during labour, and the newborn’s own behavioural style influence adjustment to the external environment. Initial assessment therefore encompasses a variety of physical and psychosocial elements. The nurse/midwife also provides opportunities for the parents and child to develop close physical and emotional attachment.

Physical changes

An immediate assessment of the newborn’s condition is performed to determine the physiological functioning of the major organ systems. The most extreme physiological change occurs when the newborn leaves the in-utero circulation and develops independent respiratory functioning. Nursing/midwifery care is directed at maintaining an open airway, stabilising and maintaining body temperature and protecting the newborn from infection.

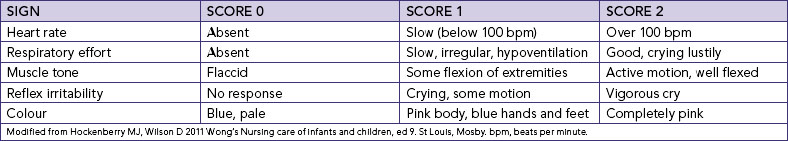

The most widely used assessment tool is the Apgar score. Heart rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, reflex irritability and colour are rated to determine overall status. The Apgar assessment is generally conducted at 1 and 5 minutes after birth, and may be repeated until the newborn’s condition stabilises. Table 20-2 outlines the scoring criteria of physiological functioning. A total score of 0–3 signifies severe distress, a score of 4–6 represents moderate difficulty and a score of 7–10 indicates little difficulty in adjusting to extrauterine life. The nurse/midwife can use the Apgar score to determine areas requiring further assessment and careful observation. In addition, the nurse/midwife monitors the newborn’s body temperature and other vital signs until these stabilise.

Psychosocial changes

After immediate physical evaluation and application of identification bracelets, the nurse/midwife promotes the parents’ and newborn’s need for close physical contact. Early parent–child interaction encourages parent–child attachment. Physical factors (e.g. fatigue, hunger and health) and emotional factors (e.g. happiness and need for affection and touch) are assessed.

Most healthy newborns are awake and alert for the first half-hour after birth. This is an opportune time for parent–child interaction to begin. Close body contact, often including breastfeeding, is a satisfying way for most families to start. If immediate contact is not possible, the nurse/midwife incorporates it into the care plan as early as possible, which may mean bringing the newborn to an ill parent or bringing the parents to an ill or premature child.

Attachment is a complex and ongoing process of interactions that is important for an infant’s sense of security. John Bowlby’s (1969) research is a cornerstone upon which many others have continued to build. It occurs when parents and newborn elicit reciprocal and complementary behaviour. Attachment behaviours include attentiveness and physical contact. Newborn behaviour involves maintenance of contact with the parent. Preterm, ill newborns and ill mothers have more difficulty with attachment if separation is prolonged. The attachment process is further complicated if parents are unable to care for the usual infant needs. You will find more information about attachment in the Cochrane Collaboration (see Online resources). Facilitating attachment behaviours and interactions is a priority in postnatal care. Midwives and child health nurses need to plan carefully to optimise close contact, and pay particular attention where health issues of either infant or mother may impede this contact.

Other health considerations during newborn transition

Airway patency

This is best ensured by removing nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal secretions with suction or a bulb syringe. However, if the newborn has a lusty cry immediately after birth, they may clear these secretions themselves. Because hypothermia increases oxygen needs, the newborn’s body temperature must be stabilised and maintained. The newborn may be placed directly on the mother’s abdomen and covered in warm blankets; be dried and wrapped in warm blankets, being sure to keep the head well covered; or be placed unclothed in an infant warmer with a temperature probe in place. For newborns unable to sustain adequate body temperature, isolettes and incubators, which supply radiant heat, are preferred.

Prevention of infection

This is a major concern in the care of the newborn, whose immune system is immature. Standard precautions need to be applied in all childbirth and perinatal settings (see Chapter 29). Of these, good hand-washing technique is the most important factor in protecting the newborn and nurse from infection. Cover gowns do not need to be worn while providing care for the healthy newborn once the blood and amniotic fluid have been removed from the infant’s skin.

The newborn

The neonatal period is classified as the first 28 days of life. During this stage the newborn’s physical functioning is mostly reflexive, with stabilisation of major organ systems the body’s main task. Behaviour greatly influences interaction between the newborn, the environment and caregivers. For example, the average 2-week-old smiles spontaneously and is able to note their mother’s face. The impact of these reflexive behaviours is generally a surge of maternal feelings of love that prompt the mother to cuddle the baby. Nurses/midwives can apply their knowledge of this stage of growth and development to promote newborn and parental health. If the nurse understands, for example, that the newborn’s cry is generally a reflexive response to an unmet need (such as hunger), they can help parents identify ways to meet those needs, such as feeding their baby on demand rather than according to a rigid schedule.

Physical changes

A comprehensive nursing assessment is performed as soon as the newborn’s physiological functioning is stable, generally within a few hours after birth. At this time the nurse measures height, weight, head circumference, temperature, pulse and respirations and observes general appearance, body functions, sensory capabilities, reflexes and responsiveness.

The average newborn weighs 3400 g, is 50 cm in length and has a head circumference of 35 cm. Up to 10% of birthweight is lost in the first few days of life, mainly through fluid losses by respiration, urination, defecation and low fluid intake. Birthweight is usually regained by the second week of life, and a gradual pattern of increase in weight, height and head circumference is evident. During the first month, these increases average 115–230 g in weight per week, 0.6–2.5 cm in length and 2 cm in head circumference (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009).

The newborn’s heart rate ranges from 120 to 160 beats per minute. The average blood pressure is 74/46 mmHg. The newborn’s respiratory movements are mainly abdominal, and vary in rate and rhythm with an average rate of 30–50 breaths per minute. The axillary temperature ranges from 36°C to 37.5°C and generally stabilises within 24 hours of birth (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009).

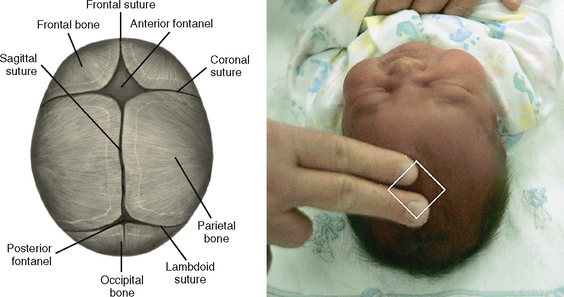

Normal physical characteristics include the continued presence of lanugo on the skin of the back; cyanosis of the hands and feet for the first 24 hours; and a soft, protuberant abdomen. Skin colour varies according to racial and genetic heritage and gradually changes during infancy. Moulding, or overlapping of the soft skull bones, allows the fetal head to adjust to various diameters of the maternal pelvis and is a common occurrence with vaginal births. The bones readjust within a few days, producing a rounded appearance. The sutures and fontanels are usually palpable at birth. The diamond shape of the anterior fontanel and the triangular shape of the posterior fontanel between the unfused bones of the skull are shown in Figure 20-2.

FIGURE 20-2 Fontanels and suture lines.

From Hockenberry MJ and Wilson D 2011 Wong’s Nursing care of infants and children, ed 9. St Louis, Mosby.

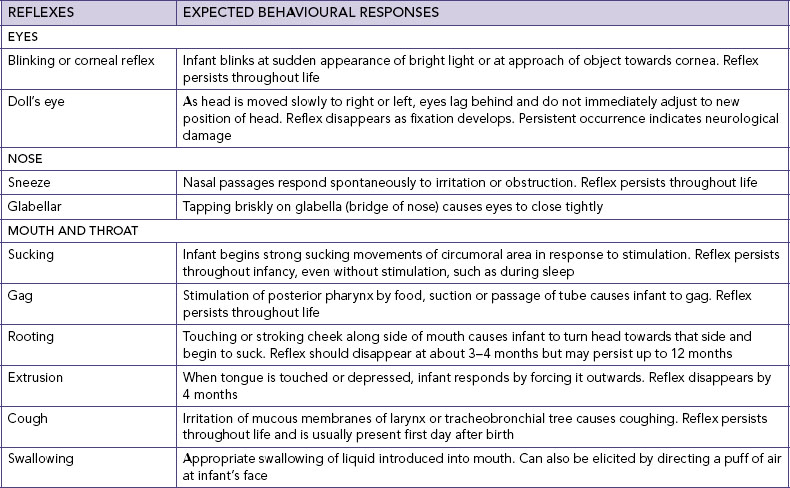

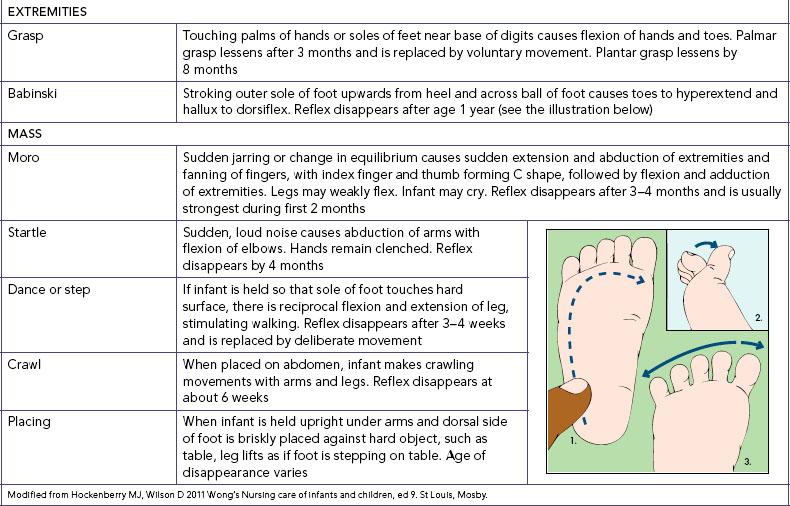

Neurological function is assessed by observing the newborn’s level of activity, alertness, irritability, responsiveness to stimuli, and the presence and strength of reflexes. Normal reflexes include blinking in response to bright lights and jerking in response to sudden, loud noises. Table 20-3 describes other commonly evaluated reflexes. An absence of any of the reflexes indicates prematurity, possible trauma, or central nervous system complications. Because the newborn depends largely on reflexes for response to environment, assessment of these characteristic responses is vital.

TABLE 20-3 ASSESSMENT OF COMMON LOCALISED REFLEXES IN THE NEWBORN

Normal behavioural characteristics of the newborn include periods of sucking, crying, sleeping and activity. Movements are generally sporadic, but they are symmetrical and involve all four extremities. The relatively flexed fetal position of intrauterine life continues as the newborn attempts to maintain an enclosed, secure feeling. Newborns normally watch the caregiver’s face, reflexively smile, and respond to sensory stimuli, particularly the primary caregiver’s face, voice and touch. Als’s (1986) seminal work in this area, as mentioned earlier, has prompted a global shift in the nursing care practices of neonatal intensive units that involves modifying the neonate’s environment to promote optimum physical, cognitive and psychosocial development. This change in practice is referred to as ‘developmental care’ and you can find out more about it by looking up a recent meta-analysis in the Cochrane Collaboration (see Online resources).

The first hour of the unmedicated newborn’s life is spent mainly in a quiet, alert state with wide-open eyes and vigorous sucking activity. Then neonates sleep almost continuously for the next 2–3 days to recover from the exhausting birth process. Thereafter, sleep periods vary from 20 minutes to 6 hours, with little day–night differentiation (Figure 20-3). Infant behaviour is characterised by five distinct states that are highly influenced by environmental stimuli. It is important for parents to understand these states (summarised in Table 20-4) and their implications for parental interaction.

FIGURE 20-3 Newborn sleep periods have little day–night differentiation.

Image: Shutterstock/Dhoxax.

The sleep position and environment for infants has been the subject of intense scrutiny over the previous 20 years, motivated in part by the puzzle of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), the unexpected and (after postmortem examination) unexplained death of an infant. Research over time has led to a rigorous public campaign for a safe sleeping position for infants. This involves the placement of infants on their backs, without loose covers or pillows that may cover their heads, and in a smoke-free environment (National SIDS Council of Australia, 2007).

There is an unfortunate tendency to ‘manage’ the sleep patterns and environments of young infants, often involving separating babies from their carers and widely spacing breastfeeds. Sleep physiology develops throughout infancy and childhood. This means that sleep patterns take considerable time to develop. Sleep–arousal patterns occur in the child’s social context but infants take time to distinguish day and night and develop consistent patterns of wakefulness and sleepiness, most taking the best part of 12 months (Stores, 2001). The widely normalised models of infant sleep patterns which suggest the establishment of all-night sleep by 3 months of age were developed using solitary-sleeping and largely formula-fed infants. The sleep–arousal patterns these suggest may not be relevant, appropriate or healthy for the majority of infants today. During nursing assessment of sleep issues, the nurse needs to investigate the parents’ expectations as well as the settling and feeding practices that are used in individual households. It may be necessary to support a change in adult expectations about sleep habits and environments rather than promote infant management strategies.

Cognitive changes

Early cognitive development begins with innate behaviour, reflexes, and sensory functions. Newborns initiate reflex activities and learn behaviours and desires. For example, newborns learn to turn to the nipple and that crying results in a parental response of feeding, nappy changing and cuddling.

Sensory functions contribute to cognitive development in the newborn. At birth, children can focus on objects about 20–25 cm from their faces and can perceive forms. A preference for the human face is apparent. Auditory and vestibular systems function from birth. These sensory capabilities allow newborns to elicit stimuli rather than simply receive them. Parents need to understand the importance of providing sensory stimulation, such as talking to their babies and holding them to see their faces. This allows infants to seek or take in stimuli, thereby enhancing learning and promoting cognitive development.

It is debatable whether infant crying is the precursor of refined language. However, crying elicits a response, and caregivers can distinguish cry patterns. Crying therefore has significance to newborns and parents. For newborns, crying is a means of providing cues to parents. Some babies cry because their nappies are wet or they are hungry or want to be held. Others cry just to make noise or because they need a change in position or activity. Crying may frustrate the parents if they cannot see an apparent cause. With the nurse’s help, parents can learn to recognise an infant’s cry patterns and take appropriate action when necessary.

Psychosocial changes

During the first month of life, parents and newborns normally develop a strong bond that grows into a deep attachment. Interactions during routine care enhance or detract from the attachment process. Feeding, hygiene and comfort measures consume much of an infant’s waking time. These interactive experiences provide a foundation for the formation of deep attachments. Newborns are active participants in this process.

If parents or children experience health complications after birth, attachment may be compromised. An infant’s behavioural cues may be weak or absent, and caregiving may be less mutually satisfying. Tired, ill parents have difficulty interpreting and responding to their infants. Children who have congenital anomalies are often too weak to be responsive to parental cues, and require special supportive nursing care. For example, infants born with heart defects may tire easily during feedings. They may rest frequently after several bursts of sucking and fall asleep after taking 30–45 mL. Infants may wake up after 1½ hours, crying because they are hungry again. Mothers, not understanding that the crying is a physiologically dictated sequence of events, may think that the infants are being fussy or that they themselves are inadequate. Both infants and mothers derive decreasing pleasure from feeding experiences. In this case, attachment is not enhanced and may even be reduced unless nursing intervention breaks the sequence of events.

Other health considerations for newborns

Hyperbilirubinaemia

Hyperbilirubinaemia is an excessive amount of accumulated bilirubin in the blood and is characterised by a yellow colouring of the skin, or jaundice. The accumulation occurs when the infant’s body is unable to balance the destruction of red blood cells (RBCs) and the use or excretion of by-products. The balance can be upset by prematurity, breastfeeding, excess production of bilirubin, certain disease states or a disturbance in the liver. Because bilirubin is highly toxic to neurons, an infant with levels greater than 18 mg/100 mL is at risk of brain damage. Phototherapy is used to help break down the bilirubin for easier excretion. Special care must be given to properly shielding the infant’s eyes to protect exposure to the light. Because excretion of the extra bilirubin can cause watery stools, adequate fluid balance in the infant must be maintained.

Inborn errors of metabolism

The nurse coordinates screening tests and other laboratory tests as indicated by the newborn’s state of health. Blood tests can be used to determine inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs). This term applies to genetic disorders caused by the absence or deficiency of a substance, usually an enzyme, essential to cellular metabolism that results in abnormal protein, carbohydrate or fat metabolism. Although IEMs are rare, they account for a significant proportion of health problems in children. Neonatal screening can detect phenylketonuria (PKU), hypothyroidism and galactosaemia, and thus allow appropriate treatment that can prevent permanent mental retardation and other health problems.

Circumcision

Newborn male circumcision is no longer practised on a routine basis in Australia or New Zealand, with the exception of some specific religious and cultural groups. Current rates are about 10–20% compared with 90% in the 1950s (Royal Australasian College of Physicians, 2010). Circumcision remains a controversial issue: an issue that is argued in terms of human rights as well as potential risks and benefits. While some of the risks and benefits sound extreme, their incidence is relatively rare (Royal Australasian College of Physicians, 2010). The most commonly recognised medical indications for circumcision include: reduction of urinary tract infections, particularly in the first year of life; reduction in the risk of cancer of the penis in later life; and some evidence that there is a decreased risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases. On the other side of the debate, arguments against circumcision include: complications associated with the procedure, which may include bleeding, infection and damage to the head of the penis; pain associated with the procedure; and reduction in sexual pleasure later in life. Care should be taken to ensure that parents making the decision to circumcise their son (or not) are directed to the most up-to-date and unbiased information available, and are given the opportunity to discuss this with appropriate professionals (Royal Australasian College of Physicians, 2010).

The infant

Infancy is the period from 1 month to 1 year of age. This period is characterised by rapid physical growth and psychosocial development during which the infant increasingly interacts with their environment and moves from an innate reflexive behavioural pattern to one that is more purposeful. These vast growth and psychosocial changes means that it is vital for nurses to understand normal developmental milestones relative to physiological parameters and why parental involvement is a necessary consideration when undertaking a comprehensive nursing assessment.

Physical changes

An infant’s steady and proportional growth is more important than absolute growth values. There are norm-referenced percentile charts for age, gender, feeding type and growth, which you will find in a variety of texts, journals and health websites. If you are unsure about what these charts look like, take the time to access your local state health website or visit a local community health centre. Measurements of weight, length and head circumference recorded over time are the best way to monitor growth. Deviations across any of the recorded measurements will alert the nurse to a potential growth problem that may require further consultation and medical intervention.

Overall infant size increases rapidly during the first year of life, with birthweight doubling in approximately 5 months and trebling by 12 months (Glasper and Richardson, 2010). Height increases by an average of 2.5 cm during each of the first 6 months and 1.25 cm during the next 6 months. This 50% increase in birth height occurs mainly in the trunk, with the chest diameter approximating that of the head by the first birthday (Berk, 2007). The fontanels become smaller, with the posterior fontanel closing at approximately 2 months of age and the anterior closing between 12 and 18 months of age.

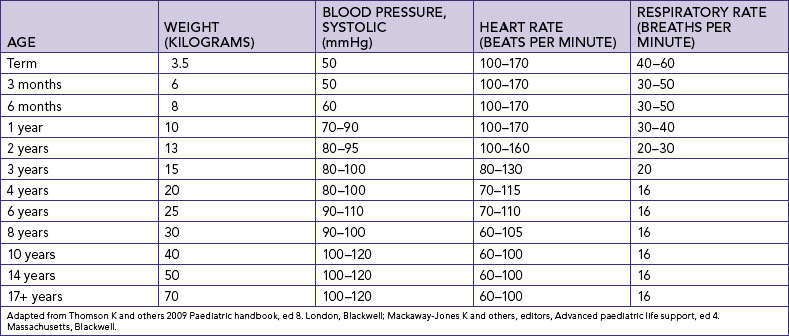

In addition to size, there is variation in physiological functioning during the first year; the average expected values for heart rate, respiratory rate and blood pressure are shown in Table 20-5. Patterns of body function, such as predictable sleep, elimination and feeding routines, also stabilise over time (see Working with diversity).

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON CULTURAL CARE

Although the biophysical aspects of sleep architecture and function are universal, sleep patterns, habits and rituals are culturally constructed. For example, the tendency to encourage infants and young children to sleep alone, away from other family members, is a relatively new Western social practice, bringing with it its own problems and challenges for early childhood development, secure attachment and wellbeing. In contrast, in some Asian groups, close sleep for infants is believed to be essential as a protective mechanism from a range of physical and spiritual harms. In societies where extended family homes and smaller houses are the norm, closer sleeping arrangements for infants and children are the norm. This means that what is considered normal or problematic sleep habits in infants and young children may vary from family to family.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

• Assess expectations, beliefs and values and sleep routines with families.

• Assess child’s sleep patterns including total hours of nocturnal sleep, patterns of wakefulness, alertness during the day, numbers of naps taken

• Assess bedtime rituals and habits

• Assess sleep issues and plan interventions from the perspective of what is normal for the specific family

Adapted from Yelland J and others: 1994 Explanatory models of maternal and infant health and sudden infant death syndrome among Asian-born mothers. In: Rice P, editor, Asian mothers, Australian birth. Pregnancy, childbirth and childrearing: the Asian experience in an English speaking country. Melbourne, Ausmed; Mosko S and others 1996 Infant sleep architecture and possible implications for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Sleep 19(9):677–84; Stores G 2001 A clinical guide to sleep disorders in children and adolescents. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Changes in size and in physiological function lead to an increased capacity for bodily movements. In infancy, initial movements are reflexive and spontaneous. As the central nervous system matures there is a consequential development of voluntary movement. Gross motor skills develop in a cephalocaudal and proximodistal pattern; that is, head control develops before trunk control, which in turn is established before leg control (Thies and Travers, 2006). Table 20-6 identifies milestones in gross motor and fine motor development; please take the time to review this table as it will give you a better understanding of how infant milestones progress over time. A nurse caring for infants and their families needs a good understanding of these fundamental physical changes, as delays in achievement of expected milestones may indicate a degree of developmental delay that could have lifelong implications for care interventions.

TABLE 20-6 GROSS AND FINE MOTOR DEVELOPMENT 0–12 MONTHS

| AGE | GROSS MOTOR SKILLS | FINE MOTOR SKILLS |

|---|---|---|

| 1 month | ||

| 2 months | ||

| 3 months | ||

| 4 months | ||

| 5 months | ||

| 6 months | ||

| 7 months | ||

| 8 months | ||

| 9 months | ||

| 10 months | ||

| 11 months | ||

| 12 months |

Adapted from Berk LE 2007 Development through the lifespan, ed 4. Boston, Allyn & Bacon; Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D 2009 Wong’s Essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

Cognitive changes

An infant learns by experiencing and manipulating the environment around them. Developing motor skills and increasing mobility expand that environment and expose the infant to a greater number of sensory stimuli, which in turn enhance cognitive development. Take a moment to return to Chapter 19 and refresh your memory about how one particular theorist describes the phases of cognitive development during infancy.

It is quite amazing to think that a newborn infant has a well-developed sense of smell, and that by 1 month of age has sufficient cognitive capacity and visual acuity to see, fix and follow the path of a moving object. Over the ensuing months, sensory development concerned with visual acuity, hearing and eye–hand coordination continue along their respective developmental pathways. Rudimentary colour vision is usually present by 2 months of age. By 6 months of age the infant can see many colours, localise and discriminate sounds as well as grasp objects in their path, which makes the environment around them a much more interesting place to explore.

Given the important role sensory stimulation plays in cognitive development, appropriate opportunities must be provided when an infant is ill or hospitalised and not in their usual environment. For example, an ill or hospitalised infant may experience a change in their usual temperament or lack the energy to interact with their environment, which has the potential to slow cognitive development. In this situation simple verbal interaction, eye contact and having an expressive face is an essential component of nursing care.

You may find it helpful for your future clinical practice to develop your own list of age-appropriate strategies that would enhance the cognitive development of a hospitalised infant. Take a moment now to develop your list.

The final cognitive change necessary to mention here is the development of speech. Speech is an important aspect of cognition that develops during the first year. Infants proceed from crying, cooing and laughing to imitating sounds, comprehending the meaning of simple commands, and repeating words with knowledge of their meaning. Table 20-7 outlines milestones of language development.

TABLE 20-7 MILESTONES OF LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN FIRST TWO YEARS

| AGE | LANGUAGE ABILITY |

|---|---|

| 1 month | Responds to voice and sounds |

| 3–4 months | Coos (oo-oo), turns towards voice and sound |

| 6–9 months | Babbles, sing-song speech, copies waving goodbye, takes turn when playing games, responds to own name |

| 9–12 months | Two parts babbling (e.g. da da), copies sounds (e.g. broom, broom for car), uses sound patterns, waves and claps hands on request |

| 12–18 months | Expresses wants through gesture and facial expression, points to objects when named, begins to use single words (naming people and objects, verbs and negatives), uses one word for many meanings, attempts to imitate new words and familiar songs |

| 18 months to 2 years | Uses two words together, vocabulary approximately 25 words, listens to a short story, understands simple commands |

Adapted from Owens RE 2007 Language development: an introduction, ed 7. New York, Allyn & Bacon.

Psychosocial changes

In Chapter 19 you explored Erikson’s psychosocial development theory. Erikson describes infancy as the period of trust versus mistrust. During this period the major emphasis is on positive parental or carer contact and nurturing of the infant, particularly in terms of visual contact and touch. If an infant has their needs for warmth, love and security met, they will develop optimism, trust, confidence and security within the world around them as they progress through childhood. Conversely, if an infant does not experience trust, they may develop insecurity, worthlessness and a general mistrust of the world in their childhood years. Development of trust occurs when parental or carer contact is constant and reliable.

During their first year, infants begin to differentiate themselves from others as separate beings capable of acting on their own. Initially, infants are unaware of the boundaries of self, but through repeated interactive and social experiences within the environment, they learn where the self ends and the external world begins. As infants determine their physical boundaries, they begin to respond to others (Figure 20-4). Infants begin to smile responsively rather than reflexively by 2–3 months of age. Similarly, they can recognise differences in people when their sensory and cognitive capabilities improve, so that by 8 months of age most infants can differentiate a stranger from a familiar person and respond differently to the two. Thus, close attachment to the primary caregivers, in most cases the parents, is usually established by this age and infants seek out these people for support and comfort during times of stress. When an infant is hospitalised, they may have difficulty establishing physical boundaries because of repeated bodily intrusions that may often have associated painful sensations. Therefore, an important nursing care consideration is to limit negative experiences where possible and ensure that pleasurable interventions such as play are included in daily care activities to support early psychosocial development.

FIGURE 20-4 Smiling at and talking to an infant encourages the infant to respond, which increases interaction with parent or caregiver.

Image: Shutterstock.

Play is an important component in promoting psychosocial development as well as the structure and chemistry within the brain. Lester and Russell (2008) propose that play is indeed influential in a child’s ability to thrive in both social and physical environs and is necessary to enhance physical and emotional functioning of the child and indeed adult. Play during infancy enables the child to engage with all that exists within their surroundings (Youell, 2008). Play provides opportunities for the infant to develop many motor skills. Much of infant play is exploratory as they use their senses to observe and examine their own body and objects of interest in their surroundings. Activities such as infants placing their toes in their mouth provide them with pleasure and information about their own body, and help form their early self-concept. Tickling, singing and talking to young infants, games such as ‘peek-a-boo’ or songs using fingers and toes are ideal for early play. The gurgles and smiles that occur during this early play promote the development of play language before the introduction of language and toys (Youell, 2008). As the infant gets older and develops motor control, play becomes more manipulative. Adults can facilitate infant learning by planning activities that promote the development of milestones and providing toys that are safe for infants to explore with the mouth and manipulate with the hands, such as rattles, wooden blocks, plastic stacking rings and squeezable stuffed animals. Infants most often engage in solitary (one-sided) play but do enjoy watching others, particularly the antics of their siblings. Infants thrive on being played with and stimulated through interaction with others.

Other health considerations during infancy

When providing nursing care to infants, it is essential to take into consideration the many factors that may have an impact on normal growth and development. The nurse has a responsibility to educate parents and other caregivers about health promotion behaviour that will positively affect perception of health and self. The following discussion outlines some of these considerations. When you have finished reading this section, you might like to conduct some additional research and explore other areas.

Accidental injury

Accidental injury is a major cause of hospitalisation and death in childhood. Box 20-3 lists the main types of injuries that can occur and possible prevention strategies based on major developmental accomplishments. When caring for an infant in hospital, the needs must be mindful of injury prevention.

BOX 20-3 Injury prevention during infancy

AGE: BIRTH TO 4 MONTHS

INJURY PREVENTION

• Not as great a danger to this age group, but should begin practising safeguarding early (see under Age: 4–7 months)

• Never shake baby powder directly on infant; place powder in hand and then on infant’s skin; store container closed and out of infant’s reach

• Hold infant for feeding; do not prop bottle

• Keep all plastic bags stored out of infant’s reach; discard large plastic garment bags after tying in a knot

• Do not cover mattress with plastic

• Use a firm mattress and loose blankets; no pillows

• Make sure cot design follows state regulations and mattress fits snugly—cot slats 6 cm apart

• Position cot away from other furniture and away from radiators

• Do not tie dummy on a string around infant’s neck

• Never leave infant alone in bath

• Do not leave infant under 12 months alone on adult or youth mattress

• When in doubt as to where to place child, use the floor

• Restrain child in infant seat and never leave child unattended while the seat is resting on a raised surface

• Not as great a danger to this age group, but should begin practising safeguards early (see under Age: 4–7 months)

• Install smoke detectors in home

• Use caution when warming formula in microwave oven; always check temperature of liquid before feeding

• Do not pour hot liquids when infant is close by, such as sitting on lap

• Beware of cigarette ash that may fall on infant

• Do not leave infant in the sun for more than a few minutes; keep exposed areas covered

• Wash flame-retardant clothes according to label directions

• Do not leave child in parked car

• Check surface heat of car restraint before placing child in seat

AGE: 4–7 MONTHS

INJURY PREVENTION

• Keep buttons, beads, syringe caps and other small objects out of infant’s reach

• Keep floor free of any small objects

• Do not feed infant hard lollies, nuts, food with pits or seeds or whole or circular pieces of meat

• Exercise caution when giving teething biscuits, because large chunks may be broken off and aspirated

• Do not feed infant while child is lying down

• Inspect toys for removable parts

• Keep baby powder, if used, out of reach

• Avoid storing large quantities of cleaning fluid, paints, pesticides, and other toxic substances

• Discard used containers of poisonous substances

• Do not store toxic substances in food containers

• Discard used button-sized batteries; store new batteries in safe area

• Know telephone number of Poisons Information Centre (listed in front of telephone directory)

• Keep all latex balloons out of reach

• Remove all cot toys that are strung across cot or playpen when child begins to push up on hands or knees or is 5 months old

• Make sure that paint for furniture or toys does not contain lead

• Place toxic substances on a high shelf or in locked cabinet

AGE: 8–12 MONTHS

INJURY PREVENTION

• Keep lint and small objects off floor and furniture, and out of reach of children

• Take care in feeding solid food to ensure that very small pieces are given

• Do not use beanbag toys or allow child to play with dried beans

• Keep doors of ovens, dishwashers, refrigerators, and front-loading washing machines and dryers closed at all times

• If storing an unused appliance, such as a refrigerator, remove the door

• Supervise contact with inflated balloons; immediately discard popped balloons and keep uninflated balloons out of reach

• Always supervise when near any source of water, such as cleaning buckets, drainage areas, toilets

• Fence stairways at top and bottom if child has access to either end

• Dress infant in safe shoes and clothing (soles that do not ‘catch’ on floor, tied shoelaces, pant legs that do not touch floor)

• Avoid walkers, especially near stairs

• Ensure that furniture is sturdy enough for child to pull self to standing position and cruise

• Administer medications as a drug, not as lollies

• Do not administer medications unless so prescribed by a practitioner

• Replace medications and poisons immediately after use; replace caps properly if a child-protector cap is used

• Place guards in front of or around any heating appliance, fireplace or furnace

• Keep electrical wires hidden or out of reach

• Place plastic guards over electrical outlets; place furniture in front of outlets

• Keep hanging tablecloths out of reach (child may pull down hot liquids or heavy or sharp objects)

Modified from Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D 2009 Wong’s Essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.* Home care instructions for care of the choking infant are available in Wong DL 2000 Wong and Whaley’s Clinical manual of pediatric nursing, ed 5. St Louis, Mosby.

Take the time to reflect on your experiences of being in a hospital ward and make a list of the dangers an infant might face, and then think of some strategies to prevent harm. One example would be ensuring the infant is placed in a suitable sleeping environment—a cot which complies with Australian safety standards (Kids Health, 2010). See Online resources at the end of this chapter for more information.

Death in infancy

Death in infancy may occur from a variety of conditions such as congenital abnormalities, morbidity associated with extreme prematurity, infection and respiratory problems or for reasons that are unclear such as SIDS (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009), which accounted for 5% of infant deaths in 2004 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006). To reiterate, there are factors known to increase the risk of SIDS, such as sleeping on the abdomen and side, the use of soft sleeping surfaces and/or loose bedding, overheating through overdressing or wrapping, smoking and sharing of beds (Hunt and Hauck, 2006). Nurses caring for infants must be cognisant of these SIDS risk factors and have a responsibility to impart this knowledge to parents or primary caregivers. The SIDS Foundation of Australia has a very informative website of frequently asked questions (FAQs) by parents and caregivers that would be worthwhile for you to visit (see Online resources).

Immunisation

Fortunately, infant deaths from vaccine-preventable disease are relatively few in number (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006). As infants and children require a number of immunisations in the first few years of life to protect against serious infections of childhood, parental education about the most up-to-date schedule is important. Nurses caring for infants and children need to know about the schedule of immunisations as well as the importance of an immunised community so that they can provide parents with information and answer queries regarding the protection of their infant’s or child’s health through immunisation. The most up-to-date information on immunisation schedules is provided on the relevant government’s website (see Online resources for Australia and New Zealand). Most parental concerns relate to potential side effects and possible risks of vaccination. As with all medications, some contraindications exist. In general, no vaccines should be given during a severe febrile illness. This precaution avoids adding possible side effects to an ill child. The side effects could be misinterpreted as additional symptoms from the illness, or illness symptoms could be misinterpreted as vaccination side effects.

Maltreatment

Child maltreatment includes intentional physical abuse or neglect, emotional abuse or neglect, and sexual abuse. Infancy is one of the highest periods of reported episodes of abuse, with neglect being the most common complaint (Lamont, 2011). Neglect is the failure to provide for the infant’s or child’s basic needs which include food, shelter, hygiene and medical attention (Beckett, 2003). It is mandatory for all healthcare workers and education professionals to report suspected cases of child abuse to the relevant child protection agency (Lamont, 2011). As a nurse working with infants and children, it is vital you are aware of signs that could be the result of maltreatment (see Box 20-4) or could be mistaken for maltreatment (see Box 20-5). As a nurse working with children, you may be involved with cases of suspected or confirmed maltreatment.

BOX 20-4 CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF POTENTIAL CHILD MALTREATMENT

PHYSICAL NEGLECT

EMOTIONAL ABUSE AND NEGLECT

SUGGESTIVE BEHAVIOURS

• Self-stimulatory behaviours such as biting, rocking, sucking

• During infancy, lack of social smile and stranger anxiety

• Antisocial behaviour, such as destructiveness, stealing, cruelty

• Extremes of behaviour, such as overcompliant and passive or aggressive and demanding

• Lags in emotional and intellectual development, especially language

PHYSICAL ABUSE

SUGGESTIVE PHYSICAL FINDINGS

• Bruises and welts on face, lips, mouth, back, buttocks, thighs or areas of torso

• Regular patterns descriptive of object used, such as belt buckle, hand, wire hanger, chain, wooden spoon, squeeze or pinch marks

• Burns, injuries, fractures, lacerations or bruises in various stages of healing on soles of feet, palms of hands, back or buttocks

• Patterns descriptive of object used, such as round cigar or cigarette burns, ‘glove-like’ sharply demarcated areas from immersion in scalding water, rope burns on wrists or ankles from being bound, burns in the shape of an iron, radiator or electric stove burner

• Absence of ‘splash’ marks and presence of symmetric burns

• Whiplash from shaking the child

• Unusual symptoms, such as abdominal swelling, pain and vomiting from punching

• Descriptive marks such as from human bites or pulling out of hair

• Unexplained repeated poisoning or unexplained sudden illness

SUGGESTIVE BEHAVIOURS

• Wariness of physical contact with adults

• Apparent fear of parents or of going home

• Lying very still while surveying environment

• Inappropriate reaction to injury, such as failure to cry from pain

• Lack of reaction to frightening events

• Apprehensiveness when hearing other children cry

• Indiscriminate friendliness and displays of affection

SEXUAL ABUSE

SUGGESTIVE PHYSICAL FINDINGS

• Bruises, bleeding, lacerations or irritation of external genitalia, anus, mouth or throat

• Torn, stained or bloody underclothing

• Pain on urination or pain, swelling and itching of genital area

• Sexually transmitted disease, non-specific vaginitis or venereal warts

• Difficulty in walking or sitting

• Unusual odour in the genital area

SUGGESTIVE BEHAVIOURS

• Sudden emergence of sexually related problems, including excessive or public masturbation, age-inappropriate sexual play, promiscuity or overtly seductive behaviour

• Withdrawn behaviour, excessive daydreaming

• Preoccupation with fantasies, especially in play

• Poor relationships with peers

• Sudden changes, such as anxiety, loss or gain of weight, clinging behaviour

• In incestuous relationships, excessive anger at mother for not protecting daughter

• Regressive behaviour, such as bed-wetting or thumb-sucking

• Sudden onset of phobias or fears, particularly fears of the dark, men, strangers or particular settings or situations (e.g. undue fear of leaving the house or staying at the day-care centre or the babysitter’s house)

• Substance abuse, particularly of alcohol or mood-elevating drugs

• Profound and rapid personality changes, especially extreme depression, hostility and aggression (often accompanied by social withdrawal)

From Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D 2009 Wong’s Essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

*in older child

BOX 20-5 CONDITIONS THAT CAN BE MISTAKEN FOR SEXUAL ABUSE

• Accidental straddle injuries

• Accidental impaling injuries

• Non-specific vulvovaginitis and proctitis

• Group A beta-streptococcal vaginitis and proctitis

• Lower extremity girdle paralysis as in myelomeningocele

• Defects that cause chronic constipation, Hirschsprung’s disease, anteriorly displaced anus

Modified from Brouder AE, Montelone JA 1994 Child maltreatment: a clinical guideline and reference. St Louis, GW Medical.

Take some time to reflect on your legal and ethical responsibilities in cases of suspected maltreatment. Also be aware of any personal feelings that may come to the fore when you consider such situations. Make a note of what your responsibilities are in relation to mandatory child protection reporting.

Nutrition and feeding practices

The quality and quantity of nutrition together with family culture, food preferences and food allergies all influence an infant’s growth and development. Nurses caring for infants and children appreciate that no one diet is effective for all children or for any particular age group.

For any infant, nutritional wellbeing is protected and nurtured through breastfeeding. The Dietary guidelines for children and adolescents in Australia incorporating the infant feeding guidelines for health workers (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2003) recommends ‘exclusive’ breastfeeding (the consumption of breast milk only) for the first 6 months of age. From 6 to 12 months of age the continuance of breastfeeding with appropriate complementary foods is recommended. In Australia during 2004–05, it was found that while 86% of infants were breastfed at 1 month of age, that figure had declined to 51% by 6 months of age (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009). From 6 months of age, breast milk can provide at least half the daily nutrient requirements or more, depending on the amount of breastfeeding each day and complementary foods ingested. Children who continue to breastfeed into their second year may obtain up to a third of their daily nutrient requirements from breast milk. Thus, it is important for nurses to promote breastfeeding and be capable of assisting breastfeeding mothers and families. You may wish to undertake further reading on the physical and psychosocial advantages of breastfeeding for both infant and mother. The dietary guidelines mentioned above can be downloaded without charge from the National Health and Medical Research Council website (see Online resources).

Nurses are well placed to influence and support infant feeding practices. The goal of feeding support is threefold:

In order to work with a mother to establish and maintain the best infant feeding practices, nurses need to assess the mother’s goals and knowledge, her lifestyle commitments and her values and beliefs, as well as the influences on her thinking regarding feeding, received from family, friends and a wide range of lay and professional resources available. Once specific education and training has taken place, nurses are in a position to assess breastfeeding technique in order to ensure good attachment and drainage of the breast during nutritive sucking. These nurses can advise women on expressing and breast-milk storage techniques. In Australia, as in many other countries globally, the study of lactation and assisting mothers to breastfeed is a specialised area of nursing/midwifery practice. You can find out more about breastfeeding for healthcare workers at the websites of the World Health Organization or, within Australia, that of the Australian Breastfeeding Association (see Online resources).