6 Planning and implementing mainstream midwifery group practices in a tertiary setting

Introduction

This chapter focuses on how we planned and implemented a mainstream Midwifery Group Practice (MGP) in a tertiary setting in an urban city in Australia. We explain the significant influence of local conditions, policy, relationships, and existing health system infrastructure in affording both opportunities and constraints in the implementation of midwifery group practices. As you will have read in Chapter 3, it is important to cultivate an understanding of the local conditions and context in which you plan to set up. We (the authors) are the Divisional Director of Midwifery and Nursing (Chris), and two Joint Midwifery Unit Heads for Midwifery Group Practice (Roz and Anne).

Our story is an Australian one. Some of the issues and messages will ring true for midwives and managers in other countries, and some will not. We suggest you take the aspects of our story that might be useful in your context and adapt these for your local use.

Context

The Women’s and Children’s Hospital (WCH), of the Children, Youth and Women’s Health Service (CYWHS) in Adelaide, is the largest publicly-funded tertiary referral teaching hospital for maternity, neonatal and paediatric services in the state of South Australia. The hospital is located in the city centre of the state capital and provides centralised specialist services for approximately 4600 births per annum. This is more than half of the public health system births for the state. Retrievals and referrals from rural centres are also accommodated. The client mix is culturally and socio-demographically diverse. Prior to implementation of the first two Midwifery Group Practices at WCH in 2004, the hospital had an integrated Birthing Centre with midwifery staff working on a roster basis to provide antenatal and birthing care for approximately 500 self selected women per annum, who met ‘low’ risk pregnancy screening criteria. Operating for 12 years with its own dedicated midwifery staff, the Birthing Centre had its own well-established culture, norms, protocols and relationships within the WCH.

Our model of midwifery group practice

In 2007, four Midwifery Group Practices (comprising 24 full-time equivalent (FTE) midwife positions and 2 unit head positions) provided a caseload model of care to approximately 1000 women and babies per annum across all risk categories, within a defined geographic area, in collaboration with other specialist services as required. The midwifery caseload care encompasses antenatal, labour and birth, and postnatal midwifery services to 4–6 weeks after birth. Women have a named primary midwife, and midwives back each other up within their practices as well as across the practices for on-call work. MGP midwives can order relevant laboratory and diagnostic investigations for their clients, and consult and refer according to the Australian College of Midwives (ACM) ‘National Midwifery Guidelines for Consultation and Referral’ (ACM 2004). Care takes place at home, in the community and in the hospital. MGP is an innovative reconfiguration of midwifery workforce and maternity service delivery in South Australia and the largest ‘all-risk’ model of its type in a tertiary hospital setting in Australia.

The vision

The Women’s and Children’s Hospital was formed from the amalgamation of two hospitals (the Queen Victoria Hospital and the Adelaide Children’s Hospital) in May 1995. A Birthing Centre was included in the new facilities, with support from Commonwealth Alternative Birthing Services funding. Like other Australian Birthing Centres, it was intended for women with low risk pregnancies and midwives worked in a team midwifery model of care, providing antenatal care and care during labour and birth, as well as immediate postnatal care until the women were transferred to the postnatal ward or were discharged home early. Demand for the Birthing Centre care was very high and many women were disappointed with being unable to access this model of care. There were some disadvantages with this service: if a woman developed a risk factor during her pregnancy or labour, she was transferred out of the Birthing Centre and the midwife relinquished care. In addition, the Birthing Centre midwives did not follow the women up at home to provide ongoing postnatal care to the woman and her newborn, in contrast with other comprehensive models of midwifery care.

We recognised and shared concerns about the medicalisation, centralisation and fragmentation of maternity care. We were also familiar with current international evidence and the various reports from around Australia recommending midwifery continuity of care models. Furthermore, we also realised the limitations of the Birthing Centre model and our inability to develop it further.

Another concern was the impending midwifery workforce shortage—we understood that we needed to use our midwives in the most effective way. Midwifery shortages in rural and remote areas were already apparent and urgent and well documented (Barclay et al. 2003) , and we knew that the metropolitan areas would soon be feeling those shortages as well.

In October 1995, Professor Lesley Page’s visit to the WCH inspired a small group of midwives, who made a commitment to develop a model of continuity of midwifery care and carer. A group of committed midwives began to meet in late 1995. None of us could have imagined that it would take 5 years before the proposal was finally written and another 4 years before commencement of our model in January 2004! One of the midwives involved in the early stages of our model (Ali Teate) reminds us of the challenges—the highs and lows—that are faced in achieving implementation of new models of midwifery continuity of care (Box 1).

Box 1 The challenges in the early days from the perspective of a midwife

I worked as a midwife at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital (WCH) in Adelaide between the years of 1993 to 2002. During these years I was very involved at the grassroots level with the setting up of the Midwifery Group Practice (MGP). It was an inspirational and frustrating time as the development of this now very successful group practice took many more years than we first anticipated to be implemented. I believe the commitment and futuristic vision of this core group of clinical midwives was what made this program a success.

The many issues and development hurdles that we experienced over the years with the creation of MGP led us to organise a conference in Adelaide in 1998. Our aim was to rally support and inspiration with fellow midwives around Australia who were interested in developing similar continuity of midwifery care programs and to show case projects where continuity of care was already happening. It was an amazing conference that brought together many different visions of midwifery continuity of care and provided a platform from which many of these visions evolved into reality.

Another important factor that contributed to the successful development of MGP in Adelaide was the Graduate Certificate in Continuity of Midwifery Care conducted by Flinders University of South Australia in partnership with the WCH. The graduate certificate brought together midwives with diverse clinical experiences and philosophical beliefs about midwifery. It was a dynamic mix of midwives who came together to study: from delivery suites, antenatal clinics and birth centres. The participants included managers, new graduates, old graduates and transformed caseload junkies. This mix of midwives enabled the concept of continuity of midwifery care to be disseminated throughout the WCH. In particular, core staff came to understand continuity of care and this assisted with the general acceptance of the model when it was implemented eventually in 2002.

Now that caseload and midwifery group practices are evolving around the country, we need to remember that these programs would not have happened without the vision and determination of many individuals. It is important to understand that these individuals would not have created change if they had not joined together. As we were able to show, communication and collaboration are key factors in getting caseload practice to happen in a sustainable way.

Planning

The planning of our model occurred in many stages. Initially interested midwives and others were invited to attend our meetings, and we brainstormed and debated the various options available to include in our model: low- or all-risk model, number of antenatal visits, use of the Birthing Centre and how to incorporate it, how the midwives would work. We welcomed the participation of consumers and of external midwifery representatives from universities and other organisations. One midwife involved in the planning won a Premier’s Scholarship and travelled to the United Kingdom to visit midwives in a variety of continuity models there. This included a visit to King’s College Hospital in London where such midwifery group practices had been in place for some years. All of this information was incorporated into our planning. Midwives came and went over these years of planning, contributing at different points. Some left the organisation or lost belief that the model would actually be implemented, yet a core group continued to meet and plan.

A proposal to implement a caseload model of care, that we called Midwifery Group Practice (MGP), was presented to the WCH Executive in 2000. Initially it was not accepted and required a further two submissions, incorporating changes, before being approved in 2001.

In Australian public sector hospitals, midwives have traditionally had their employment conditions specified and subsumed within existing Nursing Awards, which differ across eight different states and territories. In South Australia, the framework that was negotiated is based on agreed caseload numbers and other conditions of employment for the midwives such as:

The development of this industrial framework is a significant milestone within the Australian context as it currently enables midwives within public sector employment a salary and working conditions based on caseload midwifery. That is, it accommodates patterns of midwifery work to meet the needs of women and midwives, rather than ‘nursing’ style work based around the service needs of an institution. This enables newly evolving models of care that capitalise on the full use of midwifery skills and women’s requests for improved access to these models (NHMRC 1996, NMAP 2002).

In November 2003, after 2 years of negotiation, an Industrial Agreement between the Australian Nursing Federation (ANF) [the industrial union for nurses and midwives] and the then South Australian Department of Human Services (now the Department of Health) was developed for midwives working in MGP at the WCH. This Industrial Agreement was for an Annualised Salary for these midwives specifically, to enable them to be appropriately reimbursed and to work flexibly around the needs of the women requiring their care. The ratification of this Industrial Agreement through the Industrial Commission led to a further delay of almost a year before the first women entered into the MGP model of care.

The importance of the support of the Australian Nursing Federation (ANF) cannot be underestimated in the development of the Annualised Salary Agreement. Without this Agreement the model would not be as effective, nor would the midwives be able to respond to the needs of the women as they now do. The Annualised Salary Agreement developed for MGP at WCH has now been incorporated into the South Australian Public Sector Enterprise Bargaining Agreement for any public hospital in the state to use in implementing similar models of care.

Box 2 Key features of the MGP Annualised Salary

This was the Midwifery Caseload Practice Agreement in July 2005:

While this 9-year period of development was lengthy, there were advantages to this lead-time. An extensive review of the literature was undertaken and similar models in Australia and internationally were reviewed (Flint 1993, Flint et al. 1989, Homer et al. 2001b, Page et al. 1995, Rowley et al. 1995, Shields et al. 1998, Turnbull et al. 1999, Waldenström 1998, Waldenström & Turnbull 1998). This extended period also allowed time for everyone throughout the organisation to get used to the concept, to discuss it broadly, and to overcome any fears they had about moving in this direction.

Key arguments for implementing the model

There were four key strategic arguments that we consistently presented throughout all the planning and implementation:

Through our planning and researching of midwifery continuity of care projects, we were aware that these had been the subject of much research and had been shown to be safe and cost effective with good clinical outcomes. For this reason, we decided not to implement our model as a pilot or research project but rather as a reorganisation of our service, which would, of course, be evaluated. The aim and objectives of our proposal are in Box 3.

Box 3 Aims and objectives of the MGP

Aim

To restructure midwifery services and introduce a sustainable model of midwifery continuity of care and carer into the WCH, so that midwives work within a revised Industrial Agreement, providing this model of care to women in all risk groups, throughout their pregnancy, labour, birth and early postnatal period, in partnership with medical and other health care providers, as necessary.

Key planning strategies for success

Persistence and determination

It was essential, once we had envisioned our midwifery group practice model and how it would work, that we persisted in our intent to commence such a model. While there were many times when it seemed too hard and some doubted the value of trying to make such change (after all, results in the traditional system were ‘good’—why change?), it was critical that those of us committed to the change continued to support each other. Without this network of support we would never have moved to the point of implementation. After several years of planning, we were more determined than ever to succeed as too much time and effort had been invested to consider letting it go.

Convincing others

To implement such a model, particularly in a tertiary referral centre, there is a significant number of people and stakeholders to convince and get on board. In negotiations or discussions with all interest groups when implementing such models, it is essential to use clear and understandable language. Particularly with non-clinicians, it is essential to translate the principles of the model into very clear concepts using plain language.

Consumers were already engaged and had been supportive for years. The midwives committed to this model of care were on board. Many other senior midwives at WCH, who were not interested in working in the model themselves, had also been involved in the planning, so they were supportive of the model. There was a broad commitment to the service being available for all women, no matter what their risk status.

The medical staff needed a good understanding of how it would work and how it would affect them and their role in supporting it. Senior medical staff, obstetricians and neonatologists, were briefed at every stage of the planning. Sessions were convened for them to discuss how it would work and to keep them up-to-date with developments. Copies of the final proposal were forwarded to them and much informal discussion took place. The fact that the midwives would be working within the same WCH clinical guidelines as everyone else was a key selling point. It was emphasised that we were really only ‘restructuring’ the midwifery workforce.

Administrators and Department of Health staff had to be convinced that the new model was not going to cost more and part of the proposal to implement included a cost analysis. There was an initial cost for some equipment, but in terms of ongoing goods and services costs, the cost was estimated to be similar to the traditional service. If clinical outcomes demonstrated less intervention, then cost savings could be made.

Salary costs as per the Annualised Salary Agreement were planned to be higher than for midwives working rostered shifts, to compensate for the disruption to the midwives’ lives through working flexibly around the needs of the women. However, calculations indicated that midwives in the MGP model would care for significantly more women per year than midwives working in the traditional model on rostered shifts, which would offer cost effectiveness. Numerous calculations were done on potential work patterns of MGP midwives to demonstrate the costs of working under the existing Award of the Enterprise Bargaining Agreement for Nursing (which governed Awards for midwifery work) compared with an annualised midwifery salary. Costings were done on ordinary hours, potential ‘penalty rates’, ‘call back’, ‘on-call’, ‘leave loading’5 and public holiday payments to make comparisons.

During this period of planning and development of the proposal, there were significant changes to the members of the WCH Executive. It was difficult to convince non-midwives of the benefits of these models without a midwife at Executive level, as Executive members were not familiar with the differences in models of care or what they offered to women. They did not understand the need for system change at clinical service delivery level, or the expectations and needs of women to have choice and control of their childbearing experience. Once a midwife with a background in continuity models joined the Executive and re-assured them that it was a sound model, the Executive accepted and supported implementation of MGP.

Implementation

The marketing and communication to key stakeholders usually required for implementation were not really necessary in implementing our model. Planning and discussion about our MGP model of care had taken so long that everyone thought of it as inevitable once the proposal was finally accepted. Although there were further delays after our Executive had reached agreement—particularly around the finalisation of the Annualised Salary Agreement—these delays had two effects: it made everyone more determined to succeed, and we all were aware the implementation was bound to happen sometime.

The model started with 13 FTE midwives and there were no additional staff resources available in the hospital division operating budget. The FTE had to be re-allocated to this model from within the current resources of the maternity service (the Women’s and Babies’ Division) at WCH. One of the issues in the early days of planning that caused delay was the decision to convert the Birthing Centre to the MGP model of care and use the staff resources from the Birthing Centre. There was a concern that if MGP failed we might lose the Birthing Centre, which was our only midwifery-led model and had taken some years in the late 1980s and early 1990s to develop. However we took this risk and made the decision to incorporate the Birthing Centre into MGP. Once that decision was made, it meant that there were 7.3 FTE midwife positions available for MGP and another 5.7 FTE were redistributed from other services within the maternity service of the WCH. Those FTE were reallocated from the Delivery Suite, the Divisional midwifery pool (bank), the Domiciliary Midwifery Service and the Women’s Outpatients Department.

Before moving the midwives from the Birthing Centre into MGP, all of the midwives were asked if they were prepared to move into the MGP model. They were given the option to go into MGP or work in the other departments of the Women’s and Babies’ Division, and all but one chose to work in MGP.

It was a significant challenge to move the required midwifery workforce into the model before the caseload of women (clients of the future MGP) was moved. We wanted the midwives going into MGP to start with a caseload, so the women already booked to the Birthing Centre were allocated to the midwives moving into MGP. We had been booking women to the Birthing Centre to match the numbers required in MGP for some time in preparation for commencement of the new service.

Staffing the model

Recruitment of Midwifery Unit Heads from outside the WCH enabled an initial ‘job-share’ appointment between two midwives to implement the MGP model. One was an Australian midwife (Roz Donnellan-Fernandez) who had a 10-year history of working within a midwifery continuity framework as a private provider in the community with admitting rights, clinical privileges and established practice links to South Australian maternity hospitals, including local regulatory and industrial experience. The second was a midwife from Canada (Anne Nixon) who had experience in pre-legalisation midwifery, direct-entry midwifery education in Canada and New Zealand, the implementation of community midwifery caseload practices in Ontario, and recent project work in identifying frameworks for improving birthing outcomes within Aboriginal communities in South Australia. This arrangement and skill combination was instrumental in providing mutual support for dealing with challenges in the setting-up phase within the institution, and also in capitalising on building cross-sectoral partnerships. Networks were developed for clinical placement opportunities at WCH for midwifery students to work in a midwifery continuity of care model. These students were from the inaugural 3-year Bachelor of Midwifery Program conducted from the two universities in South Australia. The selection process for the midwives happened in two stages. Midwives who were recruited from the Birthing Centre undertook an interview to enable a discussion with the new joint Midwifery Unit Heads. The remaining midwife applicants were interviewed and the preferred candidates selected.

Preparing the organisation, workforce and facing industrial challenges

In addition to local context, the identification of relevant stakeholders, with whom to collaborate and agree the principles and practical strategies that will enable success and sustainability within that context, is an important consideration. Broadly grouped, five key areas have been identified as underpinning the principles and practical strategies for success and sustainability in a Midwifery Group Practice (Donnellan-Fernandez 2006):

Earlier published work by Page et al. (1995), Warwick (1996), Sandall (1997), Brodie (1996) and the previous Handbook written by the editors of this book (Homer et al. 2001a) were useful in guiding some of the planning and practical implementation strategies for setting up the MGPs. A particularly useful resource was the text Effective group practice in midwifery: working with women edited by Lesley Page (1995). Practical caseload experience in the Canadian, New Zealand and British contexts, as well as the Australian independent midwifery context, assisted the Midwifery Unit heads in putting structures, mechanisms and principles for the MGPs into practice. These resources also assisted with creative approaches to change management and strategies for organisational transformation within the context of a tertiary hospital facility.

A few years before the commencement of MGP, a Graduate Certificate in Continuity of Care was established at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital in partnership with Flinders University of South Australia. The course was accessed by a number of core staff, who identified that it enabled them to understand the context and support the development and implementation of the MGP. This course set the scene, provided theoretical background and explored the practicalities for midwives wishing to work in midwifery continuity of care or support others working in this way.

A draft implementation plan with identified milestones and a timeline was agreed between the Divisional Chief of Midwifery at WCH, the MGP Unit heads and the midwives. The long lead-in time for MGP at WCH facilitated communication with established core staff in different units and departments, and was a significant component in supporting clinical credibility and trust.

Interviews and recruitment of the initial midwifery workforce occurred 12 months prior to commencing service delivery, due to ongoing negotiation in the development and formalisation of the Annualised Salary Agreement. This delay necessitated flexible timelines that were adjusted accordingly. One advantage of this delay was the ability to organise several funded study days for the recruited midwives. These days focussed on identified learning needs, which had been solicited by the administration of a ‘self-assessment tool’. The wide range of clinical skills required in a continuity model for MGP midwives spans the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal period to 6 weeks for maternal and infant care. We initiated a process that helped us to group the learning needs of midwives and to respond to those collectively and individually in guided sessions. Team building was also a crucial feature of these early study days, whereby the midwives were facilitated to choose their work partnerships and group configurations, develop workable on-call rosters, finalise the MGP philosophy of care, and articulate group norms, service specifications and informed choice documents based on a shared vision.

Not only did these activities contribute to promoting the service, they helped to build and develop relationships with other staff and units in the hospital, facilitating early recognition and implementation of well-defined midwifery practice parameters such as the Australian College of Midwives National Midwifery Guidelines for Consultation and Referral (2004). These collaborative approaches with other providers and services set the scene for later development of specific skill development programs and tools that have now become a part of established practice in MGP, such as the Well Newborn Assessment Program, Neonatal Resuscitation Skill Program, and a Written Documentation Tool for negotiating care, provider role and responsibilities, and informed consent for ‘management plans in consultation with women’ with complex pregnancies.

Keeping the vision prominent

Having a ‘vision’ for the service that is regularly ‘shared’ with stakeholders is important both as a strategy at set-up, and during implementation and expansion, particularly as difficulties and challenges arise. Making this vision explicit and utilising a variety of communication strategies to keep all stakeholders updated and informed of your progress is necessary. Some of the approaches we used at implementation and over the course of the past three years included:

Some other practical tips are listed in Box 5.

Box 5 Practical tips for establishing the model

In setting up we found it really useful to:

There are also a number of ‘levers’ that are needed to support midwifery continuity of care. In our situation we were able to use these to support our processes (Box 6).

Midwifery workforce considerations

A significant challenge or consideration for continuity models is attracting midwives who have an interest in working across the full scope of midwifery practice and are willing to work in an on-call lifestyle, while assuming a level of autonomy and clinical decision making that has not often been available to midwives in Australia (outside of remote settings and private practice). Our service has been effective in attracting many midwives over the past few years, often from other services where they felt restricted in their role or felt that they had always wanted to work to the full scope of midwifery (as identified in the international definition of the midwife) but had been prevented from doing this by common employment models that kept them working in one fragmented area of midwifery care.

Some midwives, unsure about working in ‘caseload’, have spoken to us about their anxiety or lack of confidence in their ability to work across the full scope of midwifery practice. We have found that commitment to the model of care and enthusiasm are the most important elements, as midwives can generally be encouraged, supported and mentored to gain and consolidate skills in areas they may not have had previous exposure to. Identifying ‘teachers’ and ‘learners’ in relation to differential skill sets within MGP has been a useful strategy in supporting the whole team, and enabled a level of skill sharing for each midwife that has been an important component of labour force support in an all-risk midwifery model.

Midwives working in MGP do not wear uniforms, as much of their work takes place outside of hospital and there is no rationale to ‘identify’ them with a corporate uniform, since they build individual relationships with the women they care for and who are known to them. This has had an interesting effect often commented on by MGP midwives, who have stated that they feel as though they are treated with more respect as a person and a professional, particularly by medical staff, once they are not wearing a generic midwifery uniform.

‘Systems’ support and change management considerations

One area of increased autonomy and clinical decision making is evident in the facilitation of MGP midwives to order and interpret relevant tests (laboratory and diagnostic) for the women they care for. This is a key component of the assumption of responsibility for providing care as an autonomous primary caregiver. From a ‘systems’ perspective, WCH is an institution large enough to have an in-house laboratory, which has enabled our service to facilitate midwives to order routine diagnostic tests without the need for a medical officer to ‘sign for’ the requisitions. Each MGP midwife is issued with an internal WCH Referring Provider Number. This is an interim stop-gap strategy until state and federal legislation reforms enable adequate funding or reimbursement mechanisms that appropriately recognise the comprehensive role of midwives in maternity care in Australia. Unfortunately this strategy to facilitate ordering of tests for public health clients in a tertiary referral centre is currently unavailable to smaller services in rural and regional areas, or settings that commonly rely on diagnostic and laboratory services from private operators.

Additionally, the ACM ‘National Midwifery Consultation and Referral Guidelines’ (2004) underpinned the context for collaborating in the care of clients with medical colleagues. Our service has ‘made a space’ for midwives to exercise appropriate clinical decision making, across the scope of midwifery, consulting and referring as and when appropriate and necessary, based on midwives’ clinical judgement.

As a tertiary referral centre, there is wide range of specialist services available to MGP midwives for consultation (often available by phone or pager), including physicians, neonatologists, haematologists, infectious disease specialists, social workers and perinatal mental health specialists. This has been very helpful in the process of building successful working relationships, supporting midwives to build skills and knowledge, and in demonstrating effective collaborative care in our all-risk model. Achieving success in the tertiary setting builds confidence for expanding this model to other, smaller services across the state.

Clearly defining the role of the MGP midwife via agreed written guidelines with respect to each relevant unit in the hospital, including community agencies, offered its own range of challenges with different groups of providers and services, all of whom, it seemed, had a view about how the midwives and MGP ‘should’ be working! However the opportunity and necessity for ongoing dialogue and regularly scheduled meetings, particularly where roles and responsibilities were in question, often improved relationships with these providers and services, as well as promoted clarity, collegiality and trust around maternal and infant care, where the objectives for implementing comprehensive midwifery services were clearly identified. Instituting and fine-tuning a series of mechanisms over the first years of the operation of MGP to build collegial relationships and demonstrate reflective practice has been a defining feature of the model. Some of these mechanisms include:

Adaptation of the MGP model to respond to feedback and rising ‘system’ challenges has been crucial. Issues, such as accessing test results and case notes off-site, and facilitating strategies for the hospital switchboard to cope with significant increases in on-call paging volume with each MGP expansion, have necessitated some creative approaches and streamlining with regard to on-call rostering. A significant early systems development in the first year of service delivery was identification of a specific role for a ‘MGP bookings midwife’. Women are recruited to MGP through the regular antenatal outpatient midwifery triage process at WCH, where they identify interest or a preference for this model of care. Demand for MGP places constantly exceeds supply so the bookings midwife provides a timely and efficient filter in allocating and communicating with women and MGP midwives on the available places, which are dependent on client and midwife geography, booked annual leave and required caseload numbers. This occurs on a regularly weekly basis and has streamlined bookings since the doubling of MGP volume over three years with the expansion to three group practices in 2005 and four in 2006.

From the beginning of the MGP model, an evaluation team laid the groundwork for a review of the service at 18 months of operation. This process created a publicly credible and useful piece of research to support the ongoing operation of MGP and its further expansion (CYWHS 2005). While Level 1 evidence already supports midwifery continuity of care models, it was strategically and practically important to have a local reflection of the experience of a new model. Qualitative data from this evaluation concerning the experiences of the midwives in MGP contributes important information for midwifery recruitment and retention concerns. We have made a series of presentations of this research to key audiences, including the Minister of Health in South Australia. This was another important strategy for consolidating support for, and recognition of, the positive effects and outcomes of the model. A series of publications stemming from the evaluation are in progress.

Resource and infrastructure needs

It is important that changes in models of care anticipate the changed nature of the service in terms of space use and needs, infrastructure and support, particularly if the model expands in scope or volume. Initially MGP incorporated the two-room space of the previous Birthing Centre as the physical hub of our service. The beginning of MGP unfortunately coincided with a sharp increase of births at the WCH, which grew by nearly 700 in the first year of our operation. Space has been at a premium in the hospital and we have had great difficulty securing appropriate premises, affordable parking, space to conduct clinical visits, or adequate working spaces for midwives who are increasingly expected to have access to computerised systems to order tests and check results. We are committed to midwives working off-site in community settings linked with the hospital, and are continuing to explore options for this. We have had success with MGP midwives working from Child Youth Health sites in some areas of Adelaide, but infrastructure for computer access to clinical reporting systems needs to be improved for this to be fully facilitated as a working reality.

As we have expanded, it has been crucial to implement dedicated clerical support for the service. This has enabled appropriate interactions with clients around flexibility with changes to appointment times, an inevitable reality of caseload models as midwives must make themselves available for clients in labour. Understandably, appropriate administrative support has also been a significant factor in improving morale among the MGP midwives. Additional funding was sought for the clerical support and it was successfully argued that it is more cost effective to employ clerical staff for administrative work than to pay midwives to do non-midwifery work.

It has been important in the process of setting up an innovative service to recognise our roles as change-agents and to understand that we needed to engage with people who might not be able to imagine a change happening to a large, functioning system—or who might resist it. We have relied to a large degree on maintaining a sense of humour and resilience, and on a decision that the Joint Unit Heads made initially to work as a job-share in order to provide support to each other.

How is it progressing?

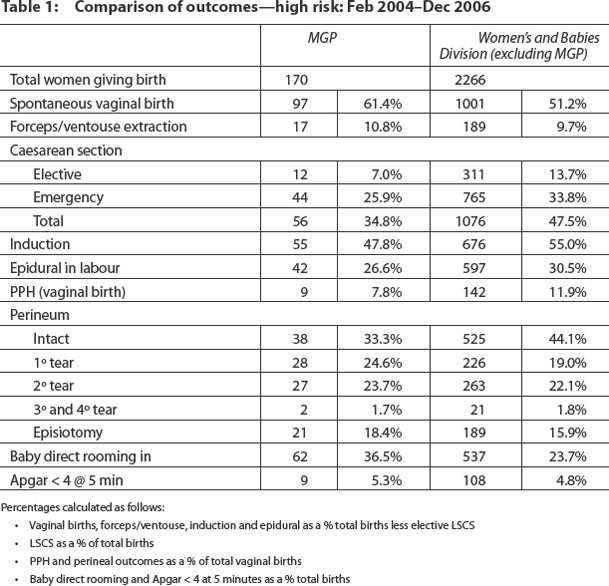

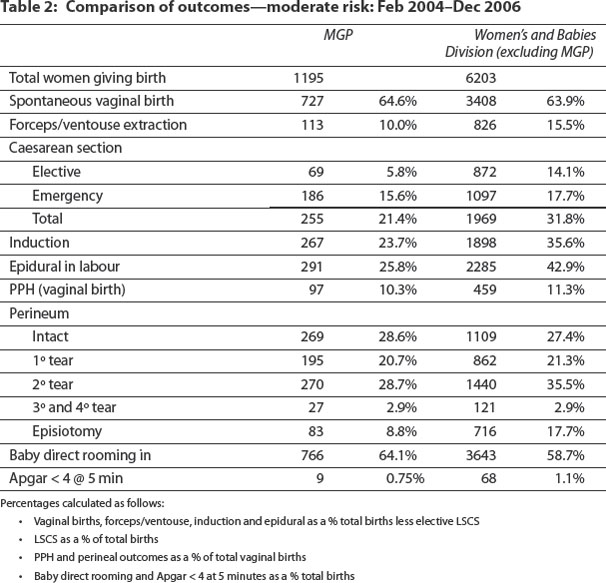

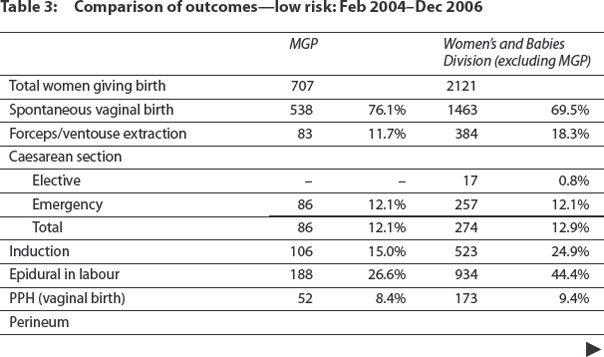

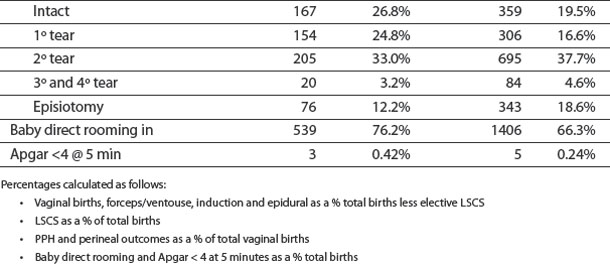

Cumulative clinical outcomes across some commonly accepted obstetric indicators for stratified risk cohorts of women cared for in MGP for the years 2004, 2005 and 2006 are presented in tables in Box 8. Cumulative clinical outcomes for the same obstetric indicators and the same stratified risk cohorts of women cared for in other services in Women’s and Babies’ Division at the WCH have also been identified. While meaningful conclusions based on comparisons of the identified cohorts is not possible in the absence of prospective randomisation of clientele (or statistical testing), the data is robust enough to support the conclusion that MGP service provides clinically effective care with outcomes comparable to that of traditional services. Notably, percentages for some common obstetric interventions, such as induction of labour, epidural analgesia, instrumental birth and lower segment caesarean section, are considerably reduced across all risk cohorts in the MGP outcomes.

Policy opportunities and obligations

Midwifery Group Practice on the scale undertaken at the WCH offers both opportunities and challenges. The current size of the model whereby care is provided for almost 1000 women per year with 24 FTE midwives and 2 FTE unit head positions means this service has a significant mainstream presence that is both robust and visibly making a difference to a large proportion of the hospital’s clientele. It has also been instrumental in providing a place for parallel change that influences birthing services for women on a broader scale than just those women currently receiving MGP services. For example, the opportunity to advance the development of state-wide public health policy guidelines for both water birth and homebirth, in addition to supporting appropriate clinical exposure for Bachelor of Midwifery students, has been possible in the South Australian context.

Box 9 Additional practical considerations with significant operational impact

Size of the model

A large MGP work force has been advantageous in ensuring a good mix of experience and collegial exchange with the larger number of midwives. Large numbers are also useful in that there is more midwife resource available as an additional labour force when midwives ‘run out of hours’ and need to call on colleagues for back up. Large volume has also ensured greater space and scope for Bachelor of Midwifery student clinical placements in their first year and again in their third year. Large is challenging, however, in that greater numbers of midwives means dealing with a larger number of administrative details, equipment and complaints, including added physical space pressures. Additionally, greater staff numbers also means more staff with unexpected, unanticipated needs, including potential for increased vacancies, which in turn requires more intensive human resource management to replace, recruit, relieve and up-skill.

Part-time workers

Midwives with small children or other commitments often prefer part-time employment in the form of 0.5 FTE or 0.75 FTE. The Annualised Salary stipulates time off-call, which is proportionately larger for part-time midwives. Current client volumes require a minimum of three midwives on-call within each group at any given time. This has implications for the groups’ on-call roster and can interrupt the continuity with women (one of the attractions of working in the model), as there is decreased likelihood of being on call when your own clients are in labour and an increased likelihood of caring for your colleagues’ clients and ‘using up your hours’. A lack of continuity can contribute to a lack of satisfaction. The need for flexible childcare arrangements can be challenging with both cost and practical implications due to the unpredictable nature of on-call work patterns.

Emotional effects of small group dynamics

Mutual interdependence is one of the strengths of working in this model and can be rewarding. However, group conflicts can be proportionately distressing. Changes as group members leave (seven maternity leaves have taken place in MGP over 3 years) can be de-stabilising for the whole group, and there is an increased need for support when group members change or leave the practice.

Sick leave and relieving midwife strategies

When midwives are suddenly sick or injured, the burden on their colleagues in a small group is extreme if they are asked to pick up the extra caseload of care. The ability to replace immediately with a fully skilled, confident, competent midwife wishing to work in caseload is limited and continuity for women is interrupted. MGP service continues to orientate midwives to be available as ‘relievers’ when required, but also continues to employ most of them into the model as it has expanded. Recruiting and developing a suitable midwifery labour force pool for sick leave, maternity leave, and long service leave relief is an important strategy for sustainability in a large volume MGP to alleviate avoidable labour force stress and burn-out.

Conclusion

Despite years of planning, which were important in themselves, many issues arose that could not have been predicted. These had to be responded to flexibly and creatively. While the challenge of shifting the culture of a tertiary maternity service can be enormous, it is both possible and very rewarding to create a different way for midwives to work. In essence we have shifted the foundations of maternity care in our organisation so that the focus is towards what our clients want from us—rather than what we think they require. Like others we are making a profound move that sees our services moving from being ‘with institution’ to being ‘with woman’ (Brodie 1996, McCourt et al. 2006).

The next chapter describes various practical strategies for ensuring safety and quality in midwifery continuity of care and in maternity care more generally. This chapter will be useful when designing and implementing your model.

Australian College of Midwives (ACM). National midwifery guidelines for consultation and referral. Canberra: Australian College of Midwives, 2004.

Australian College of Midwives (ACM). Position statement: prescribing rights and diagnostic tests. Australian Midwifery News. 2006;Spring:26-27.

Barclay L, Brodie P, Lane K, Leap N, Reiger K, Tracy S. The AMAP Report. Sydney: Centre for Family Health and Midwifery, UTS; 2003;vols I & II.

Brodie P. Being with women: the experiences of Australian team midwives. Master of Nursing thesis. Sydney: University of Technology, 1996.

Children, Youth and Women’s Health Service (CYWHS). Midwifery Group Practice: an evaluation of clinical effectiveness, quality & sustainability. Adelaide: CYWHS, Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 2005.

Donnellan-Fernandez R 2006 Principles and practical strategies for success and sustainability in Midwifery Group Practice. Paper presented at Australasian Midwifery Expo: In One Voice, 13–15 Sept, Adelaide

Flint C. Midwifery: teams and caseloads. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993.

Flint C, Poulengeris P, Grant A. The ‘Know Your Midwife’ scheme: a randomised trial of continuity of care by a team of midwives. Midwifery. 1989;5(1):11-16.

Homer C, Brodie P, Leap N. Establishing models of continuity of midwifery care in Australia: a resource for midwives and managers. Sydney: Centre for Family Health and Midwifery, University of Technology, 2001.

Homer CSE, Davis GK, Brodie PM, Sheehan A, Barclay LM, Wills J, et al. Collaboration in maternity care: a randomised controlled trial comparing community-based continuity of care with standard care. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2001;108(1):16-22.

McCourt C, Stevens T, Sandall J, Brodie P. Working with women: Developing continuity of care in practice. In Page LA, McCandlish R, editors: The New Midwifery: Science and Sensitivity in Practice, 2nd edn., Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2006.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Options for effective care in childbirth. Canberra: NHMRC, 1996.

National Maternity Action Plan (NMAP). National Maternity Action Plan. Birth Matters. 2002;6:2-22.

Page LA, Bentley RK, Jones B, Marlow D. Transforming the organisation. In: Page LA, editor. Effective group practice in midwifery: working with women. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1995:77-95.

Page L A (ed.) Effective group practice in midwifery: working with women. Blackwell Science, Oxford.

Rowley MJ, Hensley MJ, Brinsmead MW, Wlodarczyk JH. Continuity of care by a midwife team versus routine care during pregnancy and birth: a randomised trial. Medical Journal of Australia. 1995;163(6):289-293.

Sandall J. Midwives’ burnout and continuity of care. British Journal of Midwifery. 1997;5(2):106-111.

Shields N, Turnbull D, Reid M, Holmes A, McGinley M, Smith L. Satisfaction with midwife-managed care in different time periods: a randomsied controlled trial of 1299 women. Midwifery. 1998;14(2):85-93.

Turnbull D, Shields N, McGinley M, Holmes A, Cheyne H, Reid M, et al. Can midwife-managed units improve continuity of care? British Journal of Midwifery. 1999;7(8):499-503.

Waldenström U. Continuity of carer and satisfaction. Midwifery. 1998;14(4):207-213.

Waldenström U, Turnbull D. A systematic review comparing continuity of midwifery care with standard maternity services. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1998;105(11):1160-1170.

Warwick C. Supervision and practice change at King’s. In: Kirkham MJ, editor. Supervision of midwives. London: Books for Midwives; 1996:102-112.