9 The challenges of evaluating midwifery continuity of care

Introduction

In this chapter, we describe some of the challenges associated with evaluating midwifery continuity of care. The notion of ‘midwifery care as a complex intervention’ is explored as this informs the way it is evaluated. Midwifery models of care are complex as they consist of a package of interventions. In evaluations we have often tried to reduce the complexity, which may actually leave out the things that are most important. Murray Enkin, one of the original editors of Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth (Chalmers et al. 1989), highlighted this understanding by saying ‘The things that count cannot be counted’. This was a version of a famous quotation by Albert Einstein: ‘Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; and, everything that counts, cannot necessarily be counted’. This chapter deals with these issues and the importance of maintaining the complexity in evaluations by using a framework developed by the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom as a way of thinking through and planning an evaluation. This chapter also includes a brief critique of the evidence around midwifery continuity of care presented in Chapter 2.

There are a number of other resources about research and evaluation that you could also access. This chapter does not try to tell you ‘how to’ do an evaluation in terms of the ‘nuts and bolts’ as there are many books and articles to provide this information. We have included some of these at the end of this chapter.

Midwifery care: a complex intervention

The application of ‘midwifery care’ is a complex intervention, no matter how it is being delivered: core midwifery, caseload, one-to-one, team, lead maternity carer, continuity of care or continuity of carer. The key requirement of studies that attempt to determine if continuity of care works have been to set up ‘a system of care that starts early in pregnancy and provides women with an opportunity to get to know a named midwife who will provide their pregnancy, labour and birth, and post birth care’. The named midwife is usually supported by a number of other midwives. Although few studies have provided much detail of how this was done, what we do know from our own practice and research is that setting up and delivering midwifery continuity of care in existing maternity care systems is not a simple process. However, we (researchers) have imagined that we could simply reduce this complexity to simple statements or definitions like the one above in order to undertake randomised controlled trials (RCT) of continuity of care, to see if it works. We (the researchers–midwifery academics) have often determined the most important outcomes without asking other key stakeholders (such as the women) what they would regard as important or indeed whether they are concerned that the model is ‘effective’, over and above receiving sensitive and safe care. We rarely have considered or reported details about the context in which the RCT is to be conducted nor considered the environment in which the evidence might be implemented. As other chapters in this book have revealed (see Chris Hendry’s work in Chapter 3), the context or location in which it occurs has a powerful influence over the way continuity of midwifery care is understood and delivered. Arguably different contexts may therefore influence the outcomes of care. What does this mean for our current understanding of the effectiveness of the model and how it should be evaluated in the future?

This chapter draws on criticisms of the randomised controlled trial as a method for answering the question: does continuity of midwifery care work? Many trials simply view the model as a ‘black box’. Instead we suggest a more sophisticated form of evaluation for exploring the success or failure of midwifery continuity of care that draws on principles of ‘Realistic Evaluation’ (Pawson & Tilley 2005). The concepts involved in Realistic Evaluation suggest that the black box of what exactly makes up continuity of midwifery care in a particular location, at a particular point in time, may differ markedly from another location and point in time. Understanding these differences will help us to understand more clearly just what it is about the program that works, for whom, and when. Pawson and Tilley (2005) suggest that an integral part of the process of understanding the context (C) and mechanisms (M) involved in any given program will be better informed by developing theories about the relationships between C and M that may influence outcomes (O) (Walsh et al. 2007). These important theories and questions can then be incorporated into a staged framework for conducting randomised trials of complex interventions as described by the Medical Research Council (MRC) of the United Kingdom, and to which we return later in the chapter (Medical Research Council 2000).

We will now explore a number of questions to help you understand that the provision of midwifery continuity of care is a complex intervention, and evaluating the effectiveness of complex interventions is not a simple undertaking. Nevertheless, an evaluation design must be used so that we can make sure what we are providing is effective. Elements of bias need to have been reduced as much as possible, and the design also needs to incorporate the acceptability of the intervention to women and their view on what outcomes they think are important. We examine the concept of the ‘black box’ in research and in practical terms; we ask whether the model works from a number of different viewpoints; and we endeavour to answer the question of just what it is about the black box of continuity of care that is of therapeutic benefit to women. We will examine what we think might be happening and why the RCT alone, without additional methods, is of limited value in helping us to understand what is going on. The chapter concludes with a call for more theoretically driven evaluations of midwifery continuity of care.

Exploring the contents of the ‘black box’

The ‘black box’ is technical jargon for a device or system that is viewed primarily in terms of its input and output characteristics, whose internal working need not be understood by the user (Chambers English Dictionary 1992). For example, a car can be viewed as a black box. Petrol is the input and the movement along the road to a destination is the output. Few of us grapple with trying to understand exactly how the car uses the petrol to create momentum. We simply trust that it will. In the context of this chapter, midwifery continuity of care can be considered a black box since we are not sure just what goes on in the application of continuity of care that influences outcomes for women and their babies, or for which women it works well. In addition, and using the analogy of a therapeutic drug such as penicillin, we do not know what ‘dose’ of the model is required for the best effect.

Recent advances in conceptual clarity around our understanding of the meaning of continuity in health care has revealed it to be much more than a brief managerial phrase to describe a particular way of delivering maternity care. Although we have begun to develop a program of work within the MRC Framework that will inform a complex trial of continuity of midwifery care (Medical Research Council 2000), until the time of writing we have not identified any completed RCTs of continuity of care that have attempted to articulate the ‘therapeutic’ elements hidden within the black box of the model. What needs to be identified is the number of separate elements essential to the effective functioning of continuity of care. In other terms, we need to know what the ‘active ingredients’ are in order to increase the likelihood that such models will be effective.

In order to know what these are, we need to undertake a number of activities including:

We should also want to know about any unintended consequences of disruption of continuity on clinicians and on the relationships that give meaning to the work of being a health care provider. We also need to ensure that the voice of women is heard in this discussion. So let us begin the process of identifying the active ingredients of the model by asking some pertinent questions about the effectiveness of continuity of care from different perspectives.

Does midwifery continuity of care ‘work’ and for whom?

Does it work at all is an interesting question. What do we mean by ‘work’ and from whose perspective are we considering this question? As we identified previously, what we usually mean by ‘work’ in this context depends on the aims and theories that inform us. For example, based on previous evidence, we could hypothesise that continuity of care could increase satisfaction, improve preventive care and health behaviours, reduce hospitalisation, and reduce costs of care (Saultz & Lochner 2005). We might also hypothesise that it could reduce intervention in childbirth, improve access, quality and safety (Cook et al. 2000). In addition, United Kingdom maternity policy states that ‘we want to see women being supported and encouraged to have as normal a pregnancy and birth as possible, with medical interventions recommended to them only if they are of benefit to the woman or her baby’ (Department of Health 2004).

Systematic reviews have been done to combine many randomised controlled trials to consider does it work and for whom does it work. A soon to be published systematic review in the Cochrane Library has compared midwife-led models of care with other models of care for childbearing women and their infants. Secondary objectives in the review were to determine whether the effects of midwife-led care are influenced by: (1) models of midwifery care that provide differing levels of continuity, (2) varying levels of obstetrical risk, and (3) practice setting (community or hospital based) (Hatem et al. 2008).

The main findings are based on ten trials involving more than 10,000 women. In general, findings were consistent by level of risk, practice setting, and organisation of care suggesting that the effectiveness of midwife-led models of care is maintained for women classified as both low and mixed risk and in hospital-based settings (Hatem et al. 2008). Although meta-analysis is powerful, we do need to be careful about heterogeneity in such reviews, and in this case, the effects of different models of care such as team and caseload midwifery were looked at separately. However, what would have been most helpful would be to look at the effect of different levels of continuity (however limited the measurement), and this could not be done because not all trials reported on this key process measure.

In addition, few studies have considered the potential long-term benefits for the health of women and their babies through receiving midwifery continuity of care. One recent publication, Birth Territory and Midwifery Guardianship (Fahy et al. 2008) suggests the benefits may be large. Studies of home visiting by maternal-child health nurses starting in pregnancy provide very powerful evidence of long-term effects on the lives of women and their children (Olds et al. 2004) suggesting therefore that midwifery continuity may have similar effects. Oakley et al. (1996) have also shown that social support in pregnancy had benefits for health and development outcomes of the children, and the physical and psychosocial health of the mothers up to 7 years after birth. To date no systematic studies have examined the relationship between midwifery continuity of care, normal birth and the long-term health consequences.

Does it work for women emotionally?

A personal relationship with a named and known midwife provides the woman with a number of advantages not available to women who negotiate the maze of the maternity care system alone. One woman described the relationship with her midwife and the care she was receiving as ‘… care with a face and a memory and an ever open ear’ (Page 2004). A professional friendship evolved that was based on trust, intimacy, a sense of control over the process and confidence in her midwife. This description appears in one author’s definition of ‘Relational Continuity’ in which there is an ongoing therapeutic relationship between a single practitioner and a ‘patient’ that extends beyond the specific episode of ‘illness’ (Page 2004). While some of the concepts differ (‘woman’ rather than ‘patient’ and ‘wellness’ rather than ‘illness’) the nature of relationship-based midwifery enabled by having a named midwife throughout the childbearing experience appears to have been beneficial for the woman quoted above. Relationship continuity appears to foster increased communication and trust, and a sustained sense of responsibility between the woman and her midwife. In addition, such a relationship provides the woman and her family with the opportunity and power to explain and convey what is important to them to someone they know personally. So it appears that an opportunity to develop relationships with care-providers is valuable to women.

Does it work for women physiologically?

In researching the cross-disciplinary literature concerning approaches to understanding the physiology of mother–baby peri-conceptually, during the many months of pregnancy, labour and birth, and early postnatal period, we have encountered literature that rarely appears when considering the effectiveness of continuity of care (Foureur 2008). There is an intimate and continual relationship between the emotional experiences of childbearing women and the physiological consequences for themselves and their unborn or newly born infant. For example, the Barker hypothesis provides one small glimpse into how the preconception and perinatal environment can have generational consequences for the health of babies, and how damaging experiences during this time can give rise to diseases including diabetes and cardiovascular events in adult life (Barker 1994). Emerging and growing bodies of evidence now reveal that environmental stress at any time during the critically vulnerable periods of childbearing, childbirth and early life can give rise to a range of physiological and psychological consequences that reach far beyond the birth event itself (Talge 2007). One measurably effective way to reduce such stress is to provide women with professional, emotional, and physiologically-aware support at this vulnerable time. Continuity of care from expert midwives is one way this can be done (Fahy et al. 2008). Space prevents an in-depth discussion of these issues here but you are recommended to read further. What is meant by an ‘expert midwife’ in this context is part of the dilemma of not knowing exactly what is/are the active ingredient(s) in the ‘black box’ that is continuity of care.

The treatment characteristics that are a feature of randomised controlled trials of continuity of care include the nature of being in a trial that makes the women feel they are being specially treated. The midwives providing the ‘intervention’ also feel special in that they usually receive very different working conditions and possibly a different rate of pay compared with their core midwifery sisters. The continuity midwives have more opportunities for listening to women and talking with them so they are likely to have very different relationships compared with women and midwives in the regular system. We know that being listened to and being able to share feelings and thoughts with someone who is genuinely interested in you as a person is more likely to result in decreased stress and anxiety, which also has consequences for birth outcomes.

Does it work for midwives?

Too few studies have asked midwives if they enjoy working in this way and want to continue to do so, or carefully assessed the views of health service managers and policy makers. Fewer still have asked doctors whether the model ‘works’ for them. Industrial regulatory authorities (unions) or employment legislation in some countries consider the demands on the midwives’ time to be exploitative with its requirement for being on call 24/7 in many models. Some health service managers, on the other hand, feel that the midwives working in such models have very generous ‘down-time’ that is not afforded their hospital-employed colleagues. Some hospital managers have been overly zealous in their demands for the midwives to account for every minute of their time to ensure that the employer is receiving value for money. Therefore many perspectives need to be considered.

Organising care in this way gives the midwife some advantages in a large medical system, in that knowing the woman personally may give the midwife a new sense of authority in her role and understanding of her responsibilities. Knowing the woman personally motivates the midwife to ‘… challenge dogmas and routines because she can see how this affects the woman’ (Page 2004, p 15). There are other accounts and studies undertaken with midwives working in continuity of care models. The midwives consistently report feeling more valued than when they worked in routine and segmented models of care. In addition, because midwives have more control over how they work, and get a greater sense of achievement through accompanying women through their journey, they are less likely to experience burnout (McCourt et al. 2006, Sandall 1997, 1998).

There is, however, a potential downside in that core midwives may feel less valued in relation to midwives working in the new model. The fanfare with which new models are usually introduced renders the continuity of care midwives as special and different. Naming the existing model of care as ‘routine’ or ‘fragmented’ casts it in a negative light and, by association, has a negative impact on midwives working in the ‘routine’ care system. This may leave the way open for resentment at having to ‘pick up the pieces’ when the woman requires more complex care management or the midwife needs to take a rest during a long labour and wants to hand over the woman to the core midwives for a time.

Since the focus for midwives in continuity of care models is usually on keeping birth normal, exposure to and therefore experience with the skills needed to manage women with complex health needs may decrease. Such midwives may come to rely on their hospital-based core midwifery colleagues for advice and instruction. One author, who describes herself as ‘… a midwife trained in the medical model of physician-led care’ (Carolan & Hodnett 2007), saw the move to continuity of care as ‘exclusionary and alarming’. These authors worried whether the change to midwifery continuity of care created a new belief system in which normal birth was the ideal and any other form of birth was seen as a failure. They were also concerned that the ‘promotion of the midwife–woman relationship’ was seen as all-important and not really what women wanted. So it is important to understand how core midwives feel about their colleagues and how to ensure they are well aware of the critical role they play in enabling sensitive and safe midwifery practice. Few studies have evaluated the impact of continuity of midwifery care on the core midwives.

Increasingly, midwifery continuity of care is being offered to socially excluded women and those with complex pregnancies because they are seen to benefit more. Thus questions are raised about how do midwives working in continuity models develop their knowledge and skills, and what systems of referral and support do they need.

Box 1 describes a model that works for women and for midwives. Denis Walsh has researched free-standing birth centres in the United Kingdom, and here tells the story of the Lichfield Birth Centre.

Box 1 The Lichfield Birth Centre

Within the United Kingdom, free-standing maternity units incorporate a range of organisational models. Some are staffed by core birth centre midwives who provide a 24/7 cover but are not caseloading. They do not go into the community to provide antenatal or postnatal care in women’s homes or in health centres. This variant of birth centre commonly has a postnatal facility. Other free-standing birth centres are staffed by community midwives who do a form of caseloading. These units are only open when women are labouring there when they will be attended by an on-call midwife. There are no postnatal beds and women are transferred home soon after the birth.

The latter model arguably offers more continuity because the community–caseload midwives book women, attend them antenatally, may be present for the birth and undertake postnatal care in women’s homes. The core birth centre midwife model has to find other ways to maximise contact with women, apart from the intrapartum episode and postnatal period within the birth centre.

The Lichfield Birth Centre

The birth centre is situated in the midlands of England and has been a midwifery-led unit since the early 1990s. The midwives introduced during that period a booking and repeat antenatal clinic to provide opportunities to meet and get to know women having their babies at the birth centre. Though all midwives did internal rotation with shifts spread over a 24-hour period, a couple preferred to work only night duty. To enable these midwives to meet some of the women they would be caring for in labour, childbirth education classes were set up that the night duty midwives took their turn of running. Other initiatives introduced to provide opportunities for midwives to meet women booked with the birth centre were drop-in tours and visits.

Though no figures were kept of continuity achieved, the midwives told me that around 50% of the time they were caring for a labouring woman they had met before. One thing not in doubt was the high levels of satisfaction and personal fulfilment experienced by both women and midwives at the centre.

Why it works well

The reason it works well for the midwives is the high degree of autonomy they have over the structuring of their working lives. This not only involves self-rostering but also a high degree of day-to-day flexibility with starting and ending times of shifts. They have a powerful sense of ownership of the facility, having all been involved in fighting a successful campaign to remain open and in redecorating the entire facility. They also have a high degree of clinical autonomy as they are the key decision-makers for each shift. Finally, there is a palpable sense of community among them, fostered by a shared vision of what the birth centre provides and by regular social outings together (Walsh 2006a).

All of the above is encouraged and facilitated by a ‘hands-off’ external management–supervision style that encourages self-regulation and self-management by the midwives of the birth centre.

It came as little surprise to me that women were highly appreciative of the service and rallied together to support the campaign to fight closure. Particular aspects that were valued by the women were:

Strategies for implementation

From the recent history of the facility, which saw the transition from a maternity hospital to a birth centre, a number of lessons can be learnt. First, a clinical leader was appointed to facilitate this transition, and she could be best described as a transformational leader. She developed and disseminated a shared vision for the birth centre that other staff, in time, internalised. She involved key stakeholders like service user groups, general practitioners and all levels of staff in decision making. She led from the front in challenging out-dated practices and introducing an active birth model for labour care, and had clinical credibility in the eyes of the other staff. By trusting and empowering staff, she encouraged a ‘can do’ ethos around change and modernisation. The appointment of new staff as long-term staff retired hastened change as they were selected according to their philosophy and skills.

But above all, the external management structure was prepared to ‘let go’ and free the birth centre staff to develop and evolve as they saw fit. It was a high trust but low control model (Walsh 2006b).

Does it work for doctors?

Here we need to consider the private–public divide in the provision of maternity care. Doctors in private practice, whose income rises or falls depending on the number of women they book, may regard midwifery continuity of care as less than desirable. If large numbers of women choose midwife care rather than medical–obstetric care, then privately practising doctors will lose income. This was the case in New Zealand where general practitioners, who traditionally provided most maternity care until legislated midwife autonomy in 1990, have almost disappeared from the system. Many regret the loss of this aspect of their care of families across the lifespan and the loss of the excitement and joy of attending women in birth. The result is that some doctors present midwifery continuity of care in a negative way which influences the culture in which midwives work. For salaried staff obstetricians in public hospitals, midwifery continuity of care requires a level of trust in the skills of their midwifery colleagues since they feel less ‘in control’. If the culture has a negative view of the model of care, the ability to trust is diminished. Understanding how medical colleagues regard midwifery continuity of care and its effectiveness is an important component of evaluations of the future.

Does it work for the health service?

Most health service managers and policy makers are very interested in short-term cost benefits related to changing models of care delivery. Sometimes the costs of setting up the model are large, and the downside is that existing staff numbers usually suffer since the midwives who move to the new model are drawn from the existing staff complement. It is often not easy to see the benefits in short-term evaluations. Few health service managers or policy makers identify an interest in long-term cost benefits to their organisation or their area or population in general. But if they did, they would be able to identify the impact of large-scale changes in the long-term health of the population as a result of receiving effective continuity of midwifery care. Delivered effectively, this model of care is at the forefront of public health (Foureur 2005). The key issue is making sure that all costs and benefits are included in the economic modelling. For example, public health gains in breastfeeding rates and reduction in smoking; system gains such as reductions in interventions and drug use, reduced length of stay for mother and baby, and reductions in missed appointments. Costs to women should be included such as travel to and childcare time for hospital appointments. Importantly, these economic costs and benefits should be theoretically grounded and modelled at the start of the evaluation, and some economic measures of health status may be usefully included in economic evaluations.

What if it fails to work?

While most systematic reviews of midwifery continuity of care suggest that the model is successful in increasing rates of normal birth, breastfeeding, women’s satisfaction and reduces some costs to health services, there is also some disquiet about potentially increased rates of neonatal mortality (Gottvall et al. 2004). The disquiet has arisen even though all the studies conducted to date do not have sufficient power to establish the impact of the model on neonatal mortality (Fahy & Colyvas 2005, Fahy & Tracy 2006). Most of the arguments on this subject centre on the different locations for care and different way the model of care was delivered in each location, suggesting that such studies cannot be combined in a meta-analysis. Clearly, future studies must ensure that both the experimental model of care and the model of care provided in the comparison arm of any trial are clearly articulated so that appropriate meta-analyses can occur and the question of whether the model has an unanticipated negative consequence on neonatal mortality can be established without doubt. Consistency in the type of outcomes measured is also important so that we can compare like with like. A recent international study has developed a series of core measures to use when evaluating maternity care (Devane et al. 2007). This is a very useful place to start. The context in which the two models of care are delivered may also play a part in facilitating or hindering its success, so contexts must also be described in all their complexity (Box 2).

In addition, it is imperative that future studies examine whether the model of care was implemented as designed. If the model of care is based on theoretical concepts, any failure to deliver the anticipated outcomes may indicate that the model itself is inherently faulty (Rychetnik et al. 2002).

Evaluating complex health interventions: midwifery continuity of care

Midwifery continuity of care is made up of ‘various interconnecting parts’. It is without doubt a complex health intervention. Complex interventions are those that include several components, and the evaluation of complex interventions is difficult because of problems of developing, identifying, documenting, and reproducing the intervention. Other examples of complex interventions are stroke units; community-based programs to prevent heart disease; school-based interventions, for example to reduce smoking or teenage pregnancy; cognitive behavioural therapy for depression; and health promotion interventions to reduce alcohol use. The design and execution of research required to address the additional problems resulting from evaluation of complex interventions are discussed in a longer Medical Research Council (MRC) paper (2000), which has recently been critiqued by Campbell et al. (2007). These authors provide examples of using the MRC model with a number of modifications designed to shorten the amount of time required to undertake the steps outlined below (which the reader is advised to consider). Here we will focus on randomised trials but believe that this approach could be adapted to other study designs when they are more appropriate.

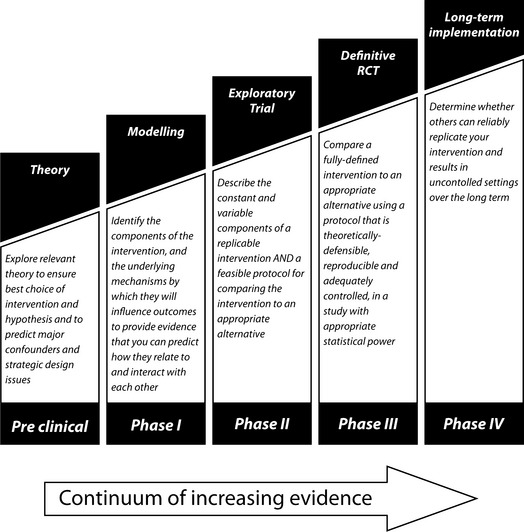

We discuss a phased approach to the development and evaluation of complex interventions that often requires use of both qualitative and quantitative data. The phases in this framework are ‘Pre-Clinical’ or theoretical (Step O in Campbell’s paper), Phase I or modelling, Phase II or exploratory trial, Phase III or main trial, Phase IV or long-term surveillance (Box 3). The purpose of each phase is briefly described below.

Preclinical or theoretical phase

The first step is to identify the evidence that the intervention might have the desired effect, that is to establish it might actually work. This may come from disciplines outside midwifery. Reviews of the theoretical basis for a continuity model intervention could lead to changes in hypothesising how it works, and the best way to deliver it. For example, in early research undertaken by one of us (MF), a theoretical model called ‘The Fear Cascade’ was employed to hypothesise the relationship between continuity of care—which prevents fear from escalating to initiate the ‘fight or flight response’ and subsequent disruption to oxytocin secretion—and outcomes (Foureur 2005, Rowley 1998).

Phase I: defining components of intervention

Phase 1 is to identify the components that are thought to influence outcomes and identify the underlying mechanism of action. It is possible to predict how they will relate to each other and what the consequences might be. Qualitative testing through focus groups, preliminary surveys or case studies can also help define relevant components. Descriptive studies of various modes of delivery may help to delineate variants of a service. For example, continuity schemes vary in purpose. Some are designed to reduce interventions, some to reduce social exclusion, some are hospital based, and some are community based. Qualitative research can also be used to explore how the intervention works and to find potential barriers to change.

Phase II: defining trial and intervention design

Acceptability and feasibility

In phase II the information gathered in phase I is used to develop the optimum intervention and study design. This often involves testing the feasibility of delivering the intervention and acceptability to providers and recipients. Different versions of the intervention may need to be tested or adapted. With the introduction of service innovations it is important to test for evidence of a learning curve, which leads to improved performance of the intervention over time indicating that a run-in period is needed before formal recruitment to the trial. The exploratory trial provides an opportunity to determine the consistency with which the intervention is delivered. Consultations could be audio or video taped to give feedback of performance to providers together with training to promote consistency.

Defining the control intervention

The content of the comparative arm of the main trial will be decided during the preparatory phase. When comparing the intervention to standard practice, this may be as complex as the intervention itself and needs to be mapped out in the same way in order to understand what the intervention is being compared with, and enable later replication or application to other settings.

Designing the main trial

The exploratory phase should ideally be randomised to allow assessment of the size of the effect. This initial assessment will provide a sound basis for calculating sample sizes for the main trial. Other design variables can also be established in an exploratory trial.

Outcomes

The validity and reliability of outcome measures for the main trial will also generally be piloted during the exploratory phase. In addition, the acceptability of collection of outcome measures will be assessed. For example, the acceptability of a long questionnaire, particularly from a control group in a trial.

Phase III: methodological issues for main trial

The main trial will need to address the issues normally posed by randomised controlled trials, such as sample size, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and methods of randomisation, as well as the challenges of complex interventions. Individual randomisation may not always be feasible or appropriate. For example, cluster randomisation is often used for trials of interventions directed at a practice or hospital team. It is often not possible to conceal allocation of treatment from the patient, practitioner and researcher in complex intervention trials. The potential biases of unblinded trials therefore have to be taken into account. Dissimilar levels of patient commitment between intervention and control groups may cause differential dropout, making interpretation of results difficult. Some trial designs try to overcome this by using different models of randomisation such as the Zelen method (Zelen 1979). The findings of trials of complex interventions are more easily generalised if they are performed in the setting in which they are most likely to be implemented. Eligibility criteria must not lead to the exclusion of women who constitute a substantial portion of those to whom the intervention is likely to be offered when implemented. Poor recruitment to a trial can also raise doubts about the extent to which the results can be generalised. Qualitative study of the processes of implementation of interventions in study arms of the main trial can further demonstrate the validity of findings.

Phase IV: promoting effective implementation

The purpose of the final phase is to examine the implementation of the intervention into practice, paying particular attention to the rate of uptake, the stability and consistency of the intervention, any broadening of subject groups, and the possible existence of adverse effects.

Conclusion

Researchers are increasingly focussing on issues concerning context when undertaking research, when interpreting the findings and when considering the application of research findings in practice and in different contexts. Even the intervention itself will have been different in composition and application in each setting. For those embarking on future evaluations of midwifery continuity of care, it is important to think through what the aims of the program are, and how they are intended to benefit women and their babies, to theorise by what processes such outcomes will occur and to measure both process and outcome. It is crucial that researchers have an understanding of how both the interventions and standard practice are being delivered, and make sure that they have a design in place to explore unintended consequences for women and their babies, and the organisation. Researchers need to take a theory-based approach to their evaluation and ask themselves the following questions:

The science of randomisation only considers the possibility of individual and unknown characteristics that may impact on outcomes. Therefore the science concludes that if the individual variation in unknown confounders is randomly distributed between groups receiving or not receiving an intervention, then we can be fairly confident that any change is due to the intervention applied. While this makes us more confident about interpreting an individual trial, it does not help us when we want to apply those research findings to our own context. Few researchers actually publish the fine details of their study—what was the context really like—was there a philosophy that totally supported midwifery continuity of care or was there an element of hostility? Did the researchers choose the midwives who would provide the intervention or were they largely self-selecting?

In order to design the best research, midwifery researchers will need to draw on evidence and work with researchers from other disciplines including economics, epidemiology, psychology and physiology. In addition, they will need to work together to share the development of valid and reliable outcome measures so that the results of studies can be compared across units, across countries and across time.

In the next chapter we provide a description of a number of forms of midwifery continuity of care, just a few examples of the wide variety of models existing. As you read through these examples, think of the complexity and diversity and the challenges to evaluating their acceptability and effectiveness.

Further reading on research and evaluation

Black N, Brazier J, Fitzpatrick R, Reeves B. Health Services Research Methods: a guide to best practice. London: BMJ Books, 1998.

Bowling A, Ebrahim S. Handbook of Health Research Methods. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2005.

Clarke A, Allen P, Anderson S, Black N, Fulop N. Studying the organisation and delivery of health services. London: Routledge, 2004.

de Vaus D. Research Design for Social Research. London: Sage, 2001.

Evans ITH, Clamers I. Testing treatments: better research for health care. London: British Library, 2006.

Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, Black N. Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: Research Methods. London: Sage, 2001.

Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Research. London: Sage, 2004.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage, 1997.

Schneider Z, Whitehead D, Elliott D, Lobiondo-Wood G, Haber J. Nursing & midwifery research: Methods and appraisal for evidence-based practice, 3rd edn. Sydney: Elsevier, 2007.

Tracy S. Ways of looking at evidence and measurement. In: Pairman S, Pincombe J, Thorogood C, Tracy S, editors. Midwifery: Preparation for Practice. Sydney: Elsevier, 2006.

Barker D. Mothers, babies and disease in later life. London: BMJ Publishing, 1994.

Campbell N, Murray E, Darbyshire J, Emery J, Farmer A, Griffiths F, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. British Medical Journal. 2007;334(7591):455-459.

Carolan M, Hodnett E. ‘With woman’ philosophy: examining the evidence, answering the questions. Nursing Inquiry. 2007;14(2):140-152.

Chalmers I, Enkin M, Keirse MJNC. Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Cook R, Render M, Woods D. Gaps in the continuity of care and progress on patient safety. British Medical Journal. 2000;320:791-794.

Department of Health. National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services. London: HMSO, 2004.

Devane D, Begley C, Clarke M, Horey D, Oboyle C. Evaluating maternity care: a core set of outcome measures. Birth. 2007;34(2):164-172.

Fahy K, Colyvas K. Safety of the Stockholm Birth Center Study: A Critical Review. Birth. 2005;32(2):145-150.

Fahy K, Foureur M, Hastie C. Birth Territory and Midwifery Guardianship. Oxford: Elsevier, 2008.

Fahy K, Tracy S. Birth centre trials are unreliable. Letter to the editor. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;185(7):407.

Foureur M. Next steps: public health in midwifery practice. In: Luanaigh PO, Carlson C, editors. Midwifery and Public Health: Future Directions and New Opportunities. London: Elsevier; 2005:221-237.

Foureur M. The Importance of Undisturbed Labour and Birth: Guarding the Birth Territory. In: Fahy K, Foureur M, Hastie C, editors. Birth Territory and Midwifery Guardianship. Oxford: Elsevier, 2008.

Gottvall K, Grunewald C, Waldenström U. Safety of birth centre care: perinatal mortality over a 10-year period. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2004;111(1):71-78.

Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7425):1219-1221.

Hatem M, Hodnett ED, Devane D, Fraser WD, Sandall J, Soltani H. Protocol: Midwifery-led versus other models of care delivery for childbearing women (Under review in 2008). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008.

McCourt C, Stevens T, Sandall J, Brodie P. Working with women: Developing continuity of care in practice. In Page LA, McCandlish R, editors: The New Midwifery: Science and Sensitivity in Practice, 2nd edn., Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2006.

Medical Research Council (MRC). A framework for development and evaluation of RCTs for complex interventions to improve health. London: MRC Health Services and Public Health Research Board, 2000.

Oakley A, Hickey D, Rajan L, Rigby A. Social support in pregnancy: does it have long-term effects? Journal of Reproductive Health & Infant Psychology. 1996;14(1):7-22.

Olds D, Robinson JA, Pettitt L, Luckey DW, Holmberg J, Ng R, et al. Effects of nurse home-visiting on maternal life course and child development: age 6. Follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1550-1559.

Page L. Working with women in childbirth. PhD. Sydney: UTS, 2004.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage, 2005.

Rowley MJ. Evaluation of Team Midwifery Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Australia: University of Newcastle, 1998.

Rychetnik L, Frommer M, Hawe P, Shiell A. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2002;56:119-127.

Sandall J. Midwives’ burnout and continuity of care. British Journal of Midwifery. 1997;5(2):106-111.

Sandall J. Occupational burnout in midwives: new ways of working and the relationship between organisational factors and psychological health and well being. Risk, Decision & Policy. 1998;3(3):213-232.

Saultz J. Defining and measuring interpersonal continuity of care. Annals of Family Medicine. 2003;1(3):134-143.

Saultz J, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(2):159-166.

Talge NM, Neal C. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2007;48(3–4):245-261.

Walsh D. Birth Centres, Community and Social Capital. Midwives Information and Resource Service Midwifery Digest. 2006;16(1):7-15.

Walsh D. Improving Maternity Service. Small is Beautiful: Lessons for Maternity Services from a Birth Centre. Oxford: Radcliffe, 2006.

Walsh D. ‘Nesting’ and ‘Matrescence’: Distinctive features of a free-standing Birth Centre. Midwifery. 2006;22(3):228-239.

Walsh D. Subverting assembly-line birth: Childbirth in a free-standing birth centre. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(6):1330-1340.

Walsh K, Duke J, Foureur M, Macdonald L. Designing an effective evaluation plan: a tool for understanding and planning evaluations for complex nursing contexts. Contemporary Nurse. 2007;25(1):136-146.

Zelen M. A new design for randomized controlled trials. New England Journal of Medicine. 1979;300(22):1242-1245.