Chapter 1 Preparing for the fellowship examination

Fellowship training requirements

Details of eligibility to sit the fellowship examination and other training requirements are listed in the Training and Examination Handbook (available via the ACEM Secretariat) with which all trainees should be familiar. Regulation 4.14 deals with the requirements of the fellowship examination. For the majority of trainees, eligibility to sit the fellowship examination is dependent on being in the final year of training and having satisfied the publication/presentation requirement.

The examination is ‘criterion referenced’ rather than ‘norm referenced’, which means that all candidates who meet the criteria will pass, and only those candidates will pass. It also means that 100% or 0% can pass a particular examination, depending on individual performance. The pass criteria are those expected of a competent emergency medicine special ist. In simple terms, this means that you will pass if you can satisfy the examiners that you can work safely and independently at the level of a consultant.

The format of the fellowship examination

The fellowship examination is currently held twice a year. The exam is divided into two components, written and clinical, and the written component is scheduled approximately two months prior to the clinical component. Only those candidates who pass following marking of the written component will be invited to participate in the clinical component. Candidates who are unsuccessful in the written component are notified by mail at the same time as other candidates receive their invitation to the clinical component.

At all times during the examination you are iden tified only as a number: names are not used. The initial digits indicate the number of the examination and subsequent digits are assigned in a manner so as not to identify candidates in any way. For example, the second examination in 2008 was the 42nd fellowship examination, so candidate numbers ranged from 4201 upwards. For the clinical components, you will be provided with a sticker to wear with your number on it. A marking scale out of 10 is used throughout the examination. A score of five constitutes a pass.

Written component

Written components are conducted in each region (with a maximum of two centres in each region). There are three parts to the written component, conducted in a single day:

The MCQs are marked by computer, while the SAQs and VAQs are each marked by two examiners in turn. The examiners are blinded to each other’s scores until they discuss their marks and agree on the final mark to be submitted. As a result, there is a delay of approx imately four weeks until the final marks are allocated.

To pass the examination overall, candidates must pass at least two of the three written parts. Candidates who fail more than one written part will not be invited to participate in the clinical component.

Clinical component

The three parts of the clinical component are conducted over two days. This is typically held on a Saturday and Sunday in an outpatient/clinic facility, but may vary. Usually the long and short cases are spread over two sites, with candidates and examiners spending the whole day at one site, whereas the structured clinical examination (SCE) is held at a single venue. The current format of the examination has the long case on the first morning, the short cases in the afternoon and the SCE on the second day.

Long case

Each candidate sees a single long case. You have 35 minutes with the patient, five minutes for con soli dation and preparation, and then 20 minutes with a pair of examiners. An agreed mark out of 10 is assigned. If you are allocated to the first portion of the long case section, you will be quarantined until the remaining candidates have finished.

Short cases

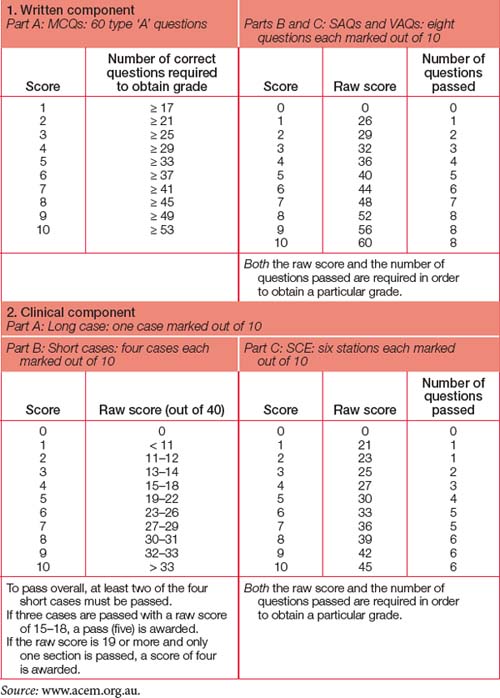

Each candidate sees a total of four short cases — two cases with one pair of examiners and another two cases with a different pair of examiners — with the expectation that at least one of these cases will involve a child. Each of the four examiners will act as the lead for an individual case. Twenty minutes is assigned to each pair of cases, which is roughly to be split between the two cases. After the first 20 minutes on two cases, you will be escorted to a different location (often next door or across the corridor). When the bell is rung five minutes later, you have the second 20 minutes with the second pair of cases and examiners. The examiners award a score out of 10 for each individual short case, and these scores are then consolidated to derive an overall score out of 10. To achieve an overall pass, candidates must pass at least two of the four cases. Consistency is rewarded more than good performance on individual cases (see Table 1.1).

Structured clinical examination (SCE)

The final section of the fellowship examination consists of the SCE with six stations. The usual format is like musical chairs in six adjacent rooms (except in this game everyone gets a seat!). Outside each room is a brief ‘prompt’ such as a brief clinical scenario. For each station, you are allocated three minutes to get to the station and review the ‘prompt’, and seven minutes to spend with a pair of examiners, one of whom will act as lead while the other scribes. Candidates should expect that one station will focus on a difficult communication or administration scenario with an actor involved. Each of the six stations is marked out of 10: to achieve an overall pass, candidates must pass at least four stations and attain a total score of 30 or more. Once again, consistency is rewarded more than good performance at individual stations. Five or more stations must be passed to pass the section overall (see Table 1.1).

Additional clinical cases

Because the clinical component involves real patients, on rare occasions a situation may occur where for the wellbeing of the patient a short or long case has to be terminated prematurely. If this occurs, the Censor-in-Chief or Chair of the Fellowship Examination Committee (FEC) will determine whether the can di date must see an extra case. ‘Spare’ cases (and examiners) are prepared for this eventuality. Usually the supplementary case can be seen immediately, but may be at the end of the session depending on individ ual circumstances. Additional clinical cases are not awarded simply to give borderline candidates another ‘chance’.

Overall result

Details of the marking schedule are provided in Table 1.1. A final possible score of 60 is obtained from the score out of 10 from each of the six sections. To pass overall, you must:

Notification of results

Once you have completed the final clinical compon ent, stay near the venue if you can, as the examiners meet shortly after candidates complete this component. Following this examiners’ meeting, the list of successful candidates is prepared for posting outside the venue and on the College website, and individual envelopes are prepared containing results. The envelopes are handed out at the designated time, usually approximately two hours after the clinical component has been completed. There is no distinction between the envelopes of ‘successful’ and ‘unsuccessful’ candidates: they all look identical, with only the candidate number on the outside. Those results not collected are mailed out to candidates.

The examination and the examiners’ meeting are highly confidential. No one other than the Censor-in-Chief is permitted to discuss any information on any candidate or any other aspect of the examination outside of the examiners’ meeting. Do not ask any examiner how you went. They are not permitted to discuss anything with you.

All candidates and their accompanying persons are then invited to drinks. Successful candidates are presented with a College pin and the winner of the Buchanan Prize is announced. The Buchanan Prize, named in honour of Peter Buchanan, one of the founding Fellows of the College, is awarded to the candidate with the highest score. Where two or more people have the same high score and other predetermined criteria are equal (including the number of sections passed and the number of examination attempts), the prize may be awarded to more than one person.

Who are the examiners?

Examiners are clinicians who have successfully applied to become examiners. They are at least five years post-fellowship and have undergone an introductory process, including observing the primary and fellow ship examinations. Examiners volunteer their time to assist in this important task.

Many examiners tend to be high achievers in other areas as well. You will most likely recognise authors of textbooks or other ‘big names’ in publishing, research or College activities. Do not be intimidated by this. Con sole yourself with the knowledge that not all exam iners passed the fellowship examination on their first attempt! They are there because they want to assist you through the process. They really do want to see you pass — aft er all, it is far more satisfying from their perspective to be awarding pass marks. And remember, there is no requirement for anyone to fail: if everyone achieves the pass standard, then every one passes.

Examiner pairs are usually selected from diff erent regions. Each serves as a ‘check’ for the other to make sure that everything is done properly and that your comments and actions are accurately acknowledged. For the most part, one will lead a given section while the other scribes against predetermined criteria. Given the few examiners who are available at a sitting, it is not always possible to ensure that candidates are assessed by examiners who do not have conflict of interest issues with them. If one examiner is known to you, it is usually (but not always) the other who will lead that section.

Observers will also be present in some sections. They may be prospective examiners, site organisers, Directors of Emergency Medical Training (DEMTs) or other Fellows of the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (FACEMs) who are bulldogs, gaining first-hand experience of the examination process. Non-FACEMs (e.g. advanced trainees) may be involved in the examination process, but they are not allowed to be present in the examination room.

You may occasionally find a scribing third examiner join the active pair. This is a ‘peer support’ examiner. Like the other observers, this person will not examine you and will not interact with you. Select ed from the senior court of examiners, this person is there to provide feedback to the examiners on their per formance as a quality assurance measure. Even the examiners get examined!

Who prepares the exam questions?

All examination questions are prepared in advance. Designated subcommittees of the FEC prepare the MCQ, SAQ, VAQ and SCE scenarios. The examiners have no prior knowledge of the questions and do not have any say in which questions are assigned to them, so you will therefore be marked by ‘peers’, not experts in pre-assigned areas.

The SCEs are workshopped by the examiners at a pre-exam meeting the night before the clinical components commence. This is a finetuning exercise to determine the exact wording of questions, the timing of sections and the prompts that will be used when required and for the examiners to agree on the pass/fail criteria. SCEs are then ‘tested’ on other FACEMs at the meeting before being finalised.

The long and short cases are also unknown to the examiners prior to the event. They see them immediately prior to the examination, taking a history and examining patients without the clinical notes and within the time constraints imposed on the candidates. They agree on the presence or absence of clinical signs that they can find and determine which are crucial for candidates to be able to detect to achieve a pass. The notes are mostly used for the long case to provide investigation results for that individual.

The journey to the fellowship examination

The best time to start preparing for the fellowship examination is as early as possible after you have completed the primary examination. Remember, you are preparing to become a competent emergency physician, not just preparing to pass another examination. Each component of the fellowship examination is an efficient way of demonstrating individual aspects of this. Even though you will be focused on ‘book work’ in the early stages, it is never too early to incorporate the principles of the written and clinical components as part of your everyday activity. This process is like making a deposit into a well-performing bank account, earning compound and better interest the closer you are to sitting the exam.

Obviously, the best way to become comfortable and familiar with doing things the ‘examination’ way is to do them routinely every day. During departmental teaching sessions, every question is a SCE, SAQ and/or VAQ opportunity. Develop a style for approaching these questions. Every case you see is at least a short case and potentially a long case. The short case examination technique is very time efficient. Develop a technique for each organ ‘system’ and use it on each and every patient you see. If the patient appears to have issues that would be well suited for a long case and is not acutely unwell, limit yourself to 35 minutes, spend five minutes collating your thoughts and then present the case to a colleague. If you have a sufficiently cooperative patient and ‘study buddy’ or colleague, ask your colleague to see the patient first, check the notes and then do it as a true ‘mock’ long case.

One of the most effective strategies for learning and consolidating your skills is to teach. Take the opportunity to present regularly in departmental education sessions. The person who gains the most from these sessions is the one standing in front of the group. You research the topic, organise your presentation and develop the skills of addressing questions. When junior staff seek out your advice, you are answering a SCE, SAQ or VAQ. Practise answer ing the actual question asked, not what you want the question to be! When you are asked to review a patient, you have an opportunity to demonstrate to junior staff how to do a short case examination and then present your findings. You can even extend the exercise and provide the answers to the questions an examiner would ask at the completion of the clinical examination.

Do not neglect the administrative aspects. Volun teer to help with departmental management, mentor junior staff , and off er to review guidelines, revise equipment lists and assist with dealing with some complaints. Depending on your department’s structure, you may be able to join senior staff meetings and do some on-call shift s with consultant back-up. These experiences are invaluable in learning the components of being a competent FACEM that you do not get to see on the shop floor.

Read the curriculum and ensure that you gain some first-hand experience on every topic. Answering a question regarding something you have actually done is an order of magnitude easier and less stressful than trying to imagine how you would do it.

Core principles

Your goal is to become a competent emergency physician. To achieve this goal, you should constantly remind yourself of the following basic principles:

Preparing yourself

The journey can be long and often lonely. The major ity of trainees take approximately 12 months from the day of ‘commitment’ to prepare for the fellow ship examination to the final examination. This is a significant period of time that requires much devotion to the task.

We typically advise our trainees that there are three basic components in their lives that they need to consider during the exam preparation phase:

Regardless of intentions, most candidates (with the exception of a few extraordinary individuals) reflect that they can adequately manage only two of these important priorities. Recognising that study is mandatory and work is essential to maintain focus (and generally to meet ongoing financial requirements), there is an inevitable ‘time out’ from social activities.

A particularly insightful partner of an examination candidate described the process as ‘like a pregnancy’. He had anticipated that his partner would change, and would be moody and less attentive as she coped with her exam preparation. All of this would be out of his control. In the end, however, all being well, there would be a present that was well worth the journey. The analogy is apt, and continues to the ‘after’ status. Once the examination is passed, you proceed to a more mature level of function within the medical system. You become one that others look to for guidance.

So you need to explain to your friends, family and loved ones as early as possible why your life may be put on hold. Apologise in advance for behaviour you will never remember. Explain the significance of the fellowship examination for your career and why it is different from all those exams that have come before it.

Juggling responsibilities is not easy for anyone, but the task will be even harder if you forget to look after yourself. Eating healthy foods, taking regular exercise, managing stress and sleeping well are important for all doctors working in Emergency Departments, but are even more essential during the run-up to the fellowship examination.

Where do you start?

The enormity of the task can appear overwhelming when it is viewed as a single entity. Break the task down in to bite-sized chunks and prepare a schedule to work your way through the curriculum. Having reached this stage of your medical career, you know what works best for you. Are you naturally a night owl or an early morning rooster? Develop a realistic schedule that is tailored to your biorhythms and work rosters and try to stick to it. Study complex topics (e.g. reading new chapters or journal articles) when you are at your most receptive and look at easier material (e.g. doing old MCQs) when you are tired. Your confidence will grow as you progress. Watching your ‘to-do’ list shrink as the ‘done’ section expands reinforces your ability to get there. If you are fortunate enough to be in a bigger centre with an established program, join in and keep up.

Which section should you prepare for first?

If you adopt the core principles outlined above, embedding them as part of your everyday practice, you will already be preparing for every section.

In your study program, try to ensure that you are not only progressing through the curriculum topics but also getting experience practising for each exam component. Regularly attempting previous questions or making up your own questions of different types and answering them at the start of a subsequent study session may achieve this. This also serves as revision. As you read new material, it is helpful to consider how the examiners could best examine that topic.

As the written component approaches, most people find they get maximum yield from focusing almost entirely on going over past questions and/or doing a lot of mock exams (obtain questions from mentors or fellow candidates or use your own). Practise writing briskly but legibly and setting out your responses in an organised and timely fashion. Use a stopwatch and get used to having hand cramps and fatigue before the big day.

Using a sporting analogy, it could be said that covering all the syllabus topics is like attaining a high level of general fitness, whereas practising individual sections of the exam is like preparing for individual competitive events. Despite acquiring a low resting heart rate and strong muscles, it is hard to win a long-distance marathon if you have only worked out in a gym and have never pounded the pavement!

Do not neglect the clinical component of the examination. Tackling this component will be substantially harder if you leave it until after you have done the written component. Leaving only 10–12 weeks is not enough time to prepare for the clinical component from a standing start. You see patients every day at work, so why not make your work as productive as can be? Consider every patient you see from this day forward as a short case, a long case or a missed opportunity.

Where can you find the best information?

The College website (www.acem.org.au) is a virtual goldmine of information, including the curriculum, examination reports, numerous guidelines, policies, position statements and other material covering every aspect of FACEM activity. The site also has the contact details for the College Secretariat, which will help you navigate the maze if you get lost. Spend a lot of time at this site.

In addition, the College has other avenues of immense value to you. Most importantly, read the College’s Training and Examination Handbook in its entirety. Every site accredited for training has at least one DEMT who is familiar with training requirements and usually has a fellowship training schedule ready to go, even if no one else is sitting at that particular moment. Further up the ‘ladder’ are regional Censors and Deputy Censors who are always ready to help wherever they can.

There are a number of recommended texts: use those that work best for you. The reference list in Chapter 9 can give you a starting point, as it highlights what most FACEMs find of greatest value. In addition, the source journals listed in the chapter are those that are most read by FACEMs and so should guide you towards what will be foremost in the minds of your examiners, those who will be setting the questions and those who will be assisting you in your preparation.

Critique

Part of the pathway to success involves getting others to ‘assess’ your performance. Without constructive critique, you cannot correct deficiencies and improve. As you start presenting cases, practising written components and responding to probing questions, you will inevitably receive feedback that leaves you feeling deflated and despondent. There is no way to avoid this, so you need to develop a strategy to deal with it. Keep going — as you progress, this will happen less often. And remember, even your most admired FACEM occasionally gets things wrong and does not know all the answers. If they can handle it, so can you.

Study groups

A burden shared is a burden halved. Spending time with others going through the same experience is helpful, and groups of up to about six people can be especially so. You can keep each other on track, share fears and frustrations, test each other with MCQs, and take turns being examiner and candidate practising the written and clinical components. Taking turns being the ‘examiner’ is most fruitful. This gives you the opportunity to provide constructive critique instead of just receiving it all the time. Refining your own technique becomes an easier task after watching others make the same errors or watching something done well. A special benefit of practising in this manner is those magic moments when you get to laugh with each other when someone says or does something really, really silly!

Other specialists

Pairing up is also a good way to seek out useful clinics and consultant rooms in other specialties. Attending clinics or rooms gives you access to patients with good signs that you can present to a specialist in the field. If you examine these patients as short cases and then present them to the specialist concerned, the patients are usually impressed both by your proficiency (a slick examination always impresses) and by the knowledge that the specialist displays while interacting with you. It teaches you what is important for these patients, ensuring that you do indeed know when to refer and how best to investigate. Negotiating a regular presence for senior trainees will train a generation. Everyone wins from this process. Practise this introduction (or similar):

Hi, we’re preparing for our fellowship examination. We were wondering if we could join you in your clinic or rooms. Apart from seeing patients with good signs, we’re especially interested in the details of management. This will allow us to ensure that all our referrals to you are appropriate and worked up properly.

Apart from tweaking the ‘referral’ buttons, the sentiment is genuine. Some of the fellowship examinations between specialties share common ground, and opportunities exist to occasionally join other trainees on their journey or share resources. For example, physician exam trainees always seem to know where patients with the best signs can be located. Intensive care fellowship candidates must undertake vivas that are not dissimilar to SCEs. Such interactions encourage a collegiate atmosphere to fellowship training within institutions and can reduce feelings of isolation.

Preparation courses/opportunities

A number of formal and informal opportunities exist to participate in activities that will assist you in preparing for the fellowship examination. The ACEM Annual Scientific Meeting (late in the year) and Winter Symposium (mid-year) are excellent opportunities to meet other trainees and FACEMs from all regions. Oral and poster presentations can guide you on how to present and how questions can be addressed, and this can be enormously valuable when considering your own presentation/publication requirement.

Generally, each region has at least one local fellowship training program. Most make this accessible to others to join in, so even if you are not working at a site, you will usually be welcome if you provide a positive contribution.

Some regions have developed formal courses, including practice written examinations. Details are available on the College website.

In addition to courses specifically aimed at the fellowship examination, a number of other courses provide valuable learning experiences. The following list is not exhaustive, and you are strongly encouraged to talk to colleagues in emergency medicine and other specialties to determine what else is available.

ALS (advanced life support) course

A variety of course formats exist, with courses run regularly throughout Australasia. Courses approved by the Australian Resuscitation Council (ARC) can be accessed via its website (www.resus.org.au).

APLS (advanced paediatric life support) course

This three-day course addresses all aspects of paedi atric emergency management. Even if you see children regularly, this course is valuable. If you can’t get to the course, get a course manual.

See the course website for more information (www.apls.org.au).

EMST (early management of severe trauma) course

In Australasia, advanced trauma life support (ATLS) courses are designated EMST, which is an historical ‘quirk’. Run by the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS), the same three-day course is run all over the world. ‘Immersion’ in trauma management is very effective. The surgical skills section provides an opportunity to perform procedures not normally accessible elsewhere (venous cut down, DPL, surgical airway). This section alone makes the course worth while. Unfortunately, waiting time for non-surgical trainees can be long.

More details are available under the Skills Training section of the RACS website (www.racs.edu.au).

ACME (advanced complex medical emergencies) course

Simulation training has matured significantly in recent years. A number of senior FACEMs have been involved in the creation and running of this high-intensity course, and more details can be obtained from the College website (www.acem.org.au).

CCrISP (care of the critically ill surgical patient) course

This course runs along a similar three-day format to the EMST course and is compulsory for surgical trainees. Based on MET-type principles of early recognition and management of medical complications, this course has broad application to surgical and medical conditions and has instructors from all the critical care specialties, as well as senior surgeons. A particularly valuable aspect of this course is its strong emphasis on communication skills. More details are available under the Skills Training section of the RACS website (www.racs.edu.au).

EMSB (emergency management of severe burns) course

If trauma appeals to you and/or management of burns is something you need to be more familiar with, this course has it all. The course is run by the Australia and New Zealand Burn Association (ANZBA), and course dates and information can be obtained from the Health Care Professionals section of the ANZBA website (www.anzba.org.au).

Keeping it all together

Preparing for the fellowship examination is a stressful undertaking. As the first exam date draws closer, your stress levels will rise, and you must have a strategy to deal with this. Keeping to your schedule is vital, as is looking after yourself. Many students plan some block time off to study prior to the written component. Remember, however, the significant others in your life and quarantine some time away from work and study to spend with them. Make a plan for regular ‘dates’ with your partner, family and/or friends: go for walks together, have a meal together with no books in sight or whatever else you agree upfront. One hour a week can make all the difference to your relationships and friendships. Never break these dates! Talk about your frustrations together and plan for your life after the exam: make a list of the things you would like to do and the people and places you would like to visit.

Some of our trainees have found enormous benefit from engaging the services of a professional such as a sports psychologist to assist in their preparation for the exam. Candidates whose performance is impaired by significant anxiety and/or those who have experienced an episode of failure may particularly benefit from the practical strategies that such professionals can impart.

Creating the right impression

What you wear for the examination can help create the right impression. Remember, revealing outfits usually have a negative impact. Examiners and the majority of candidates wear suits for the clinical com ponents of the exam. Although such dress is not mandatory, ask yourself whether you really want to stand out from the crowd in this respect. This does create a somewhat artificial situation, as this is not what clinicians typically wear at work, but it is a form of examination ‘tradition’ — better to embrace it than resist it.

Examination attire is not well suited to carrying the tools of the trade. You will be expected to provide your own stethoscope, tendon hammer, cotton wool, sharp pins, torch, tongue depressors, ruler or tape measure, visual acuity chart and red hatpin for testing visual fields. Most candidates prefer to use their own ophthalmoscope and auroscope for familiarity, although this is not essential. Decide early on whether you want to carry them all in your pockets or a bag/briefcase.

A number of candidates carry small toys to placate/distract children. If you decide to do so, choose carefully. Ensure that they are child-safe and avoid ones that make any noise that will make your examination more difficult. If your ploy works, it may be hard to retrieve the items in the time constraints available. Be prepared to gift them.

Whatever choices you make regarding your attire, diagnostic tools and paediatric distracters, decide ahead of the event and practise, practise, practise examining patients in this manner so that you are comfortable and don’t fumble around trying to find things. At least a couple of practice sessions are essential. Use a tiepin/hair tie to ensure your tie/hair doesn’t drape on the patient.

However, the most important component of the impression you create is your attitude. Recall your inten tion to be a competent emergency medicine specialist and be one. Take each question you are asked as a lead to a discussion with a colleague. There will be no traps or hidden agendas. The examiners gen uinely want to hear what you know. Conversely, they don’t want to be argued with. Your responses should be considered, to the point and not waffly. Speak audibly at a pace you are comfortable with. If you are not sure what a question means, politely say so and it will be rephrased. Do not be concerned when the topic changes. Each new question is an opportunity for you to demonstrate your competence in another area and the examiners may be deliberately trying to lead you in order to maximise your overall score on their marking template.

Do not be concerned if the questions become more and more detailed. The examiners may be giving you an opportunity to show just how much you know (to get a higher score). If you get to the point of saying ‘I’m sorry, I don’t know’, they have achieved this. Be comfortable saying this and take extreme care in guess ing answers. Wildly inappropriate answers may sig nificantly detract from your performance, particularly if what you have conjured shows poor judgement.

Travel considerations

Depending on the location of the examination, a long trip and change of time zone may be involved. Plan to arrive in sufficient time to find your way around in daylight (including the route to the venues) and adjust to time zones if necessary. On the day, plan to arrive well in advance of the examination start time. Being held up in traffic watching the clock tick is not a good way to spend the moments immediately before the exam.

Make yourself comfortable in good accommodation away from noise. If you choose to travel with your support person(s), this is especially important. Plan how you will interact with them over the days of the clinical components and ensure this is optimal for your performance. Others with you are welcome to join you at the postexamination drinks.

If you are to be quarantined, make sure you are prepared for this eventuality. We would caution against having detailed discussions about the exam, because talking with other candidates can inadvert ently detract from your confidence. Polite social conversation is acceptable and can help pass an anxious waiting period, but some candidates may prefer to wait quietly alone and this should be respected.

Coping with failure

Excellent preparation is the best way to avoid failing. Spend quality time with your DEMT(s) and heed their perception regarding your readiness for the exam. If they think you need more time to prepare, then maybe you do. Look out for well-meaning individuals who tell you that it can be useful to have a go ‘for experience’ or ‘just in case you get lucky’: this is questionable advice.

Remember, no matter how much time and eff ort you have invested in the study process, no one is immune from the possibility of failing. Accordingly, our advice is to have a strategy in place for dealing with this contingency. When the envelopes are handed out aft er the examiners’ meeting, most unsuccessful candidates tend to slip away quietly, but all are welcome to the drinks session. Different candidates deal with the situation in different ways.

If you are unsuccessful, you will be notified by mail of your marks in each section of the examination. You may also request further feedback from the Censor-in-Chief, who can discuss your performance with you via telephone in the weeks after the exam. Your DEMT(s) should also be able to debrief you and offer confidential counselling and support, as well as help you plan for the future.