Chapter Twenty-seven Breasts and regional lymphatics

INTRODUCTION

The breasts, or mammary glands, are present in both females and males, although in the male they are rudimentary throughout life. The female breasts are accessory reproductive organs whose function is to produce milk for nourishing the newborn.

SURFACE ANATOMY

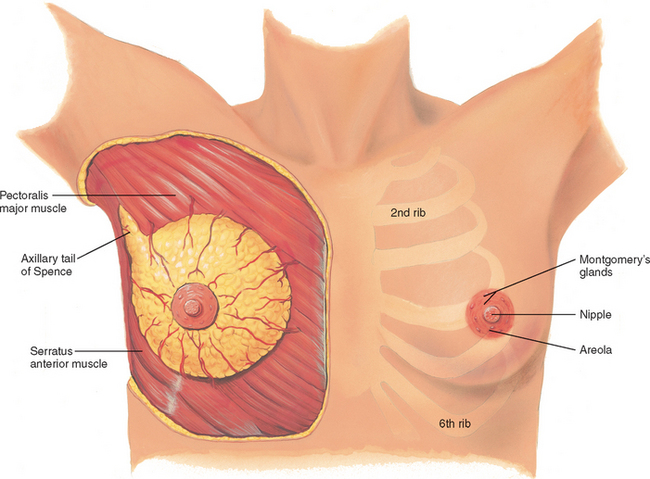

The breasts lie anterior to the pectoralis major and serratus anterior muscles (Fig 27.1). The breasts are located between the second and sixth ribs, extending from the side of the sternum to the midaxillary line. The superior lateral corner of breast tissue, called the axillary tail of Spence, projects up and laterally into the axilla.

The nipple is just below the centre of the breast. It is rough, round and usually protuberant; its surface looks wrinkled and indented with tiny milk duct openings. The areola surrounds the nipple for a 1- to 2-cm radius. In the areola are small elevated sebaceous glands, called Montgomery’s glands. These secrete a protective lipid material during lactation. The areola also has smooth muscle fibres that cause nipple erection when stimulated. Both the nipple and areola are more darkly pigmented than the rest of the breast surface; the colour varies from pink to brown depending on the person’s skin colour and parity.

INTERNAL ANATOMY

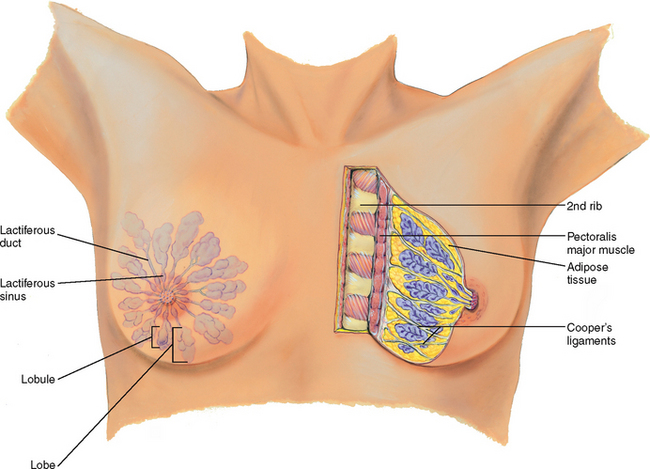

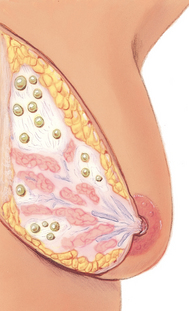

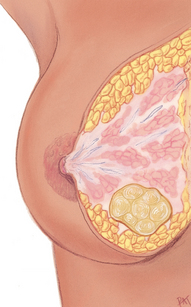

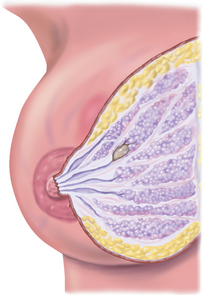

The breast is composed of (1) glandular tissue, (2) fibrous tissue including the suspensory ligaments and (3) adipose tissue (Fig 27.2). The glandular tissue contains 15 to 20 lobes radiating from the nipple, and these are composed of lobules. Within each lobule are clusters of alveoli that produce milk. Each lobe empties into a lactiferous duct. The 15 to 20 lactiferous ducts form a collecting duct system converging towards the nipple. There, the ducts form ampullae, or lactiferous sinuses, behind the nipple, which are reservoirs for storing milk. The suspensory ligaments, or Cooper’s ligaments, are fibrous bands extending vertically from the surface to attach on chest wall muscles. These support the breast tissue. They become contracted in cancer of the breast, producing pits or dimples in the overlying skin.

The lobes are embedded in adipose tissue. These layers of subcutaneous and retromammary fat actually provide most of the bulk of the breast. The relative proportion of glandular, fibrous and fatty tissue varies depending on age, cycle, pregnancy, lactation and general nutritional state.

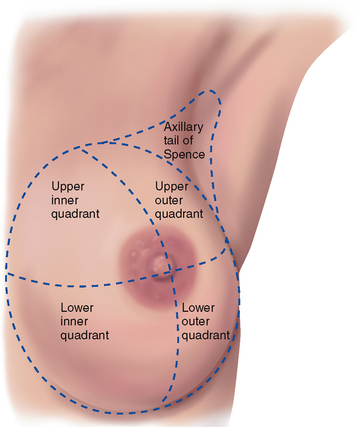

The breast may be divided into four quadrants by imaginary horizontal and vertical lines intersecting at the nipple (Fig 27.3). This makes a convenient map to describe clinical findings. In the upper outer quadrant, note the axillary tail of Spence, the cone-shaped breast tissue that projects up into the axilla, close to the pectoral group of axillary lymph nodes. The upper outer quadrant is the site of most breast tumours.

LYMPHATICS

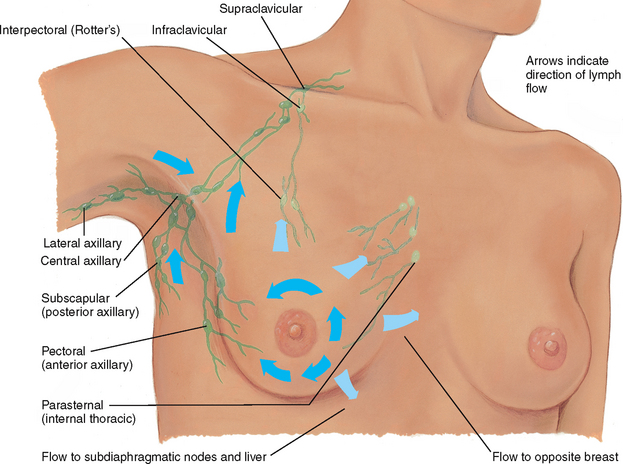

The breast has extensive lymphatic drainage. Most of the lymph, more than 75%, drains into the ipsilateral (same side) axillary nodes. Four groups of axillary nodes are present (Fig 27.4):

1. Central axillary nodes—high up in the middle of the axilla, over the ribs and serratus anterior muscle. These receive lymph from the other three groups of nodes.

2. Pectoral (anterior)—along the lateral edge of the pectoralis major muscle, just inside the anterior axillary fold.

3. Subscapular (posterior)—along the lateral edge of the scapula, deep in the posterior axillary fold.

From the central axillary nodes, drainage flows up to the infraclavicular and supraclavicular nodes.

A smaller amount of lymphatic drainage does not take these channels but flows directly up to the infraclavicular group, deep into the chest or into the abdomen or directly across to the opposite breast.

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

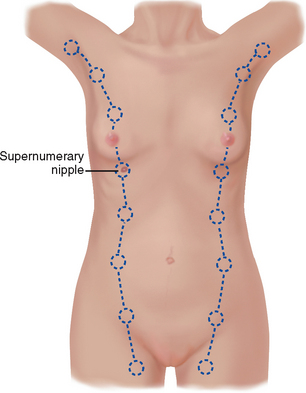

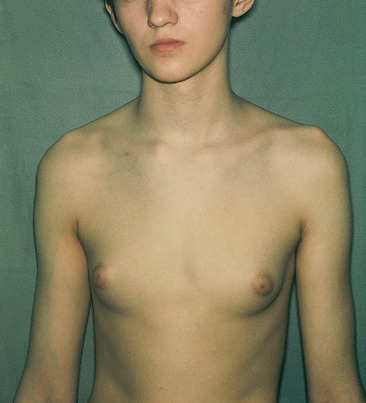

During embryonic life, ventral epidermal ridges, or ‘milk lines’, are present; these curve down from the axilla to the groin bilaterally (Fig 27.5). The breast develops along the ridge over the thorax, and the rest of the ridge usually atrophies. Occasionally a supernumerary nipple (i.e. an extra nipple) persists and is visible somewhere along the track of the mammary ridge (Fig 27.6).

At birth, the only breast structures present are the lactiferous ducts within the nipple. No alveoli have developed. Little change occurs until puberty. However at birth some infants appear to have breast tissue. This is a normal response to maternal hormones and disappears within the first week of life.

The adolescent

At puberty the oestrogen hormones stimulate breast changes. The breasts enlarge, mostly as a result of extensive fat deposition. The duct system also grows and branches, and masses of small, solid cells develop at the duct endings. These are potential alveoli.

Ethnicity and genetic correlates of race appear to be important factors affecting the onset of puberty (Butts and Seifer, 2010). Sociocultural factors (such as childhood obesity) and environmental factors also influence the age of the onset of breast development and onset of menarche (Butts and Seifer, 2010).

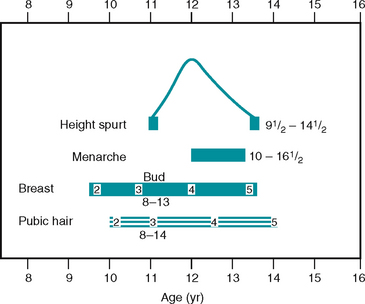

Occasionally, one breast may grow faster than the other, producing a temporary asymmetry. This may cause some distress; reassurance is necessary. Tenderness is also common due the influence of reproductive hormones, particularly oestrogen. Although the age of onset varies widely, the five stages of breast development follow this classic description of sexual maturity rating, or Tanner staging (Table 27.1).

TABLE 27.1 Sexual maturity rating in girls

| Stage | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Full development from stage 2 to stage 5 takes an average of 3 years, although the range is 1.5 to 6 years. During this time, pubic hair develops and axillary hair appears 2 years after the onset of pubic hair. The beginning of breast development precedes menarche (beginning of menstruation) by about 2 years. Menarche occurs in breast development stage 3 or 4, usually just after the peak of the adolescent growth spurt around age 12 years. Note the relationship of these events (Fig 27.7). This aids in assessing the development of adolescent girls and increases their knowledge about their own development.

Breasts of the nonpregnant woman change with the ebb and flow of hormones during the monthly menstrual cycle. Nodularity increases from midcycle up to menstruation. During the 3 to 4 days before menstruation, the breasts feel full, tight, heavy and occasionally sore. The breast volume is smallest on days 4 to 7 of the menstrual cycle.

The pregnant female

During pregnancy, breast changes start during the second month and are an early sign of pregnancy for most women. Pregnancy stimulates the expansion of the ductal system and supporting fatty tissue as well as development of the true secretory alveoli. Thus the breasts enlarge and feel more nodular. The nipples are larger, darker and more erectile. The areolae become larger and grow a darker brown as pregnancy progresses and the tubercles become more prominent. (The brown colour fades after lactation, but the areolae never return to the original colour.) A venous pattern is prominent over the skin surface (see Fig 28.4).

After the fourth month, colostrum may be expressed. This thick yellow fluid is the precursor for milk, containing the same amount of protein and lactose but practically no fat. The breasts produce colostrum for the first few days after delivery. It is rich with antibodies that protect the newborn against infection, so breastfeeding is important. Milk production (lactation) begins 1 to 3 days postpartum. The whitish colour is from emulsified fat and calcium caseinate.

The female over 65 years

After menopause, ovarian secretion of oestrogen and progesterone decreases, which causes the breast glandular tissue to atrophy. This is replaced with fibrous connective tissue. The fat envelope atrophies also, beginning in the middle years and becoming marked in the eighth and ninth decades. These changes decrease breast size and elasticity so the breasts droop and sag, looking flattened and flabby. Drooping is accentuated by the kyphosis in some older women.

The decreased breast size makes inner structures more prominent. A breast lump may have been present for years but is suddenly palpable. Around the nipple the lactiferous ducts are more palpable and feel firm and stringy because of fibrosis and calcification. The axillary hair decreases.

THE MALE BREAST

The male breast is a rudimentary structure consisting of a thin disk of undeveloped tissue underlying the nipple. The areola is well developed, although the nipple is relatively small. During adolescence, it is common for the breast tissue to temporarily enlarge, producing gynaecomastia. This condition is usually unilateral and temporary. Reassurance is necessary for the adolescent male, whose attention is riveted on his body image. Gynaecomastia may reappear in the male over 65 years and may be due to testosterone deficiency.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

The mean age at which non-Indigenous Australian women experience their first menstrual period (menarche) is 12.9 years (Watson et al, 2007) and is comparable to findings from studies undertaken in Europe and the United States of America (Herman-Giddens et al, 1997). To date, there is no specific data on age of onset of menarche in Indigenous Australian women.

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most common cancer that occurs in Australian and New Zealand women. The risk of developing breast cancer to age 85 years is 1 in 9 for Australian women and 1 in 767 for Australian men (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008). There are similar rates of breast cancer in New Zealand (New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2009).

The incidence of breast cancer varies with different cultural groups. Although the incidence of breast cancer is significantly lower in Indigenous Australian women than in non-Indigenous Australian women, Indigenous Australian women have significantly lower 5-year crude survival rates (65% and 82% crude survival, respectively) (AIHW and National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre (NBOCC*), 2009). In New Zealand, although breast cancer occurs with equal frequency in Māori and non-Māori women, Māori women are nearly twice as likely to die from the disease as non-Māori mainly because they tend to present with late stage breast cancer at the time of diagnosis (Cancer Control Council of NZ, 2008).

In Australia, non-Indigenous women are significantly more likely to have had a mammogram through the BreastScreen Australia Program than are Indigenous Australian women. Between 2005 and 2006, the age-standardised participation rate for non-Indigenous women aged 50–69 years was 57% compared with 38% for Indigenous Australian women in the same age range (AIHW/NBOCC*, 2009). Although there is no single main factor influencing Indigenous women’s decisions to use the BreastScreen Australia Program service, there are historical and culturally related influences. Indigenous distrust of non-Indigenous institutions and beliefs about cancer and western medical treatments are identified as contributing factors (Cunningham et al, 2008; Shahid and Thompson, 2009). Similarly, there are a number of cultural and social reasons why Māori and Pacific Islander women tend not to have regular screening mammograms (NZ Breast Cancer Foundation, 2010).

Cultural and social issues associated with diet and exercise are becoming the focus of increasing attention. Mounting interest in the role that lifestyle factors such as diet, exercise and weight have on breast cancer survival and/or comorbidity and mortality has led researchers to evaluate the effects of these factors on the disease. Current findings point to a possible but inconsistent benefit of a prudent, vegetable rich, low-fat/high vegetable eating pattern on disease-free survival (Thompson and Thompson, 2009). Physical activity and weight control are also considered to be lifestyle factors potentially impacting on breast cancer prevention and survival (Kellen et al, 2009). Two or more hours of brisk walking or equivalent per week and a body mass index (BMI) <25 (kg/m2) for postmenopausal breast cancer (NBOCC*, 2009a) are recommended. Despite the potential therapeutic effects of lifestyle factors of diet, alcohol consumption, exercise and weight control on breast cancer prevention, they remain low modifiable breast cancer risk factors (NBOCC*, 2009a).

SUBJECTIVE DATA

In western culture the female breasts signify more than their primary purpose of lactation. Women are surrounded by messages that feminine norms of beauty and desirability are enhanced by and dependent on the size of the breasts and their appearance. More recently, women leaders have tried to refocus this attitude, stressing women’s self-worth as individual human beings, not as stereotyped sexual objects. The intense cultural emphasis is gradually changing, yet the breasts are still crucial to a woman’s self-concept and her perception of her femininity.

Matters pertaining to the breast affect a woman’s body image and generate deep emotional responses. These responses may take strong forms that may be observed as you discuss the woman’s history. One woman may be acutely embarrassed talking about her breasts, as evidenced by lack of eye contact, minimal response, nervous gestures or inappropriate humour. Another woman may talk wryly and disparagingly about the size or development of her breasts. A young adolescent is acutely aware of her own development in relation to her peers. Or, a woman who has found a breast lump may come to you with fear, high anxiety and even panic. Although many breast lumps are benign, women initially assume the worst possible outcome—cancer, disfigurement and death. While you are collecting the subjective data, tune in to cues for these behaviours that call for a straightforward and reasoned attitude.

Because of the physiological relationship between the breasts and lymph glands, any assessment of a woman’s breast must include an assessment of the axillary lymph glands. Subjective assessment enables you to obtain information directly from the patient about signs and symptoms they are experiencing.

Axilla

| Assessment guidelines | Clinical significance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| Breast | |

| Clinical alert: Mastalgia (pain in the breast) may occur with trauma, inflammation, infection and benign breast disease. | |

| • Where is the pain? Localised or all over? Is the painful spot sore to touch? Do you feel a burning or pulling sensation? | |

| • Is the pain cyclic? Any relation to your menstrual period? | Cyclic pain is common with normal breasts (commonly associated with the menstrual cycle), and benign breast (fibro-cystic) disease. Oral contraceptives can also cause breast tenderness. |

| • Is pain related to specific cause? Is the pain brought on by strenuous activity especially involving one arm; a change in activity; touch during sex; part of underwire bra; exercise? | |

| Carefully explore the presence of any lump. A lump present for many years and exhibiting no change may not be serious but still should be explored. Approach any recent change or new lump with suspicion. | |

Clinical alert: Galactorrhoea (lactation not associated with childbirth). Note medications that may cause clear nipple discharge: oral contraceptives, phenothi-azines, diuretics, digitalis, steroids, methyl-dopa, calcium channel blockers. Bloody or blood-tinged discharge is always significant. Any discharge with a lump is significant. |

|

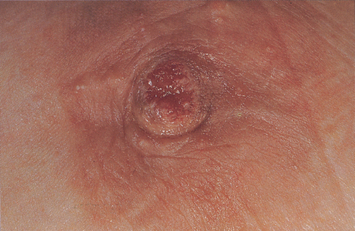

Clinical alert: Paget’s disease of the nipple. Inflammatory malignant neoplasm of the nipple and areola that is usually associated with carcinoma in deeper breast tissue. Paget’s disease starts with a small crust on the nipple apex, then spreads to areola. Eczema (superficial dermatitis) or other dermatitis rarely starts at nipple unless it is due to breastfeeding. It usually starts on the areola or surrounding skin and then spreads to the nipple. |

|

| A lump from an injury is due to local haematoma or oedema and should resolve shortly. Or, trauma may cause a woman to feel the breast and find a lump that really was there before. | |

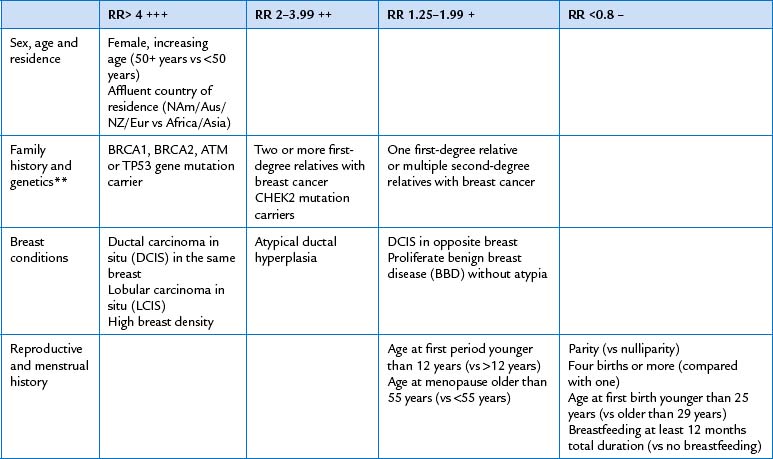

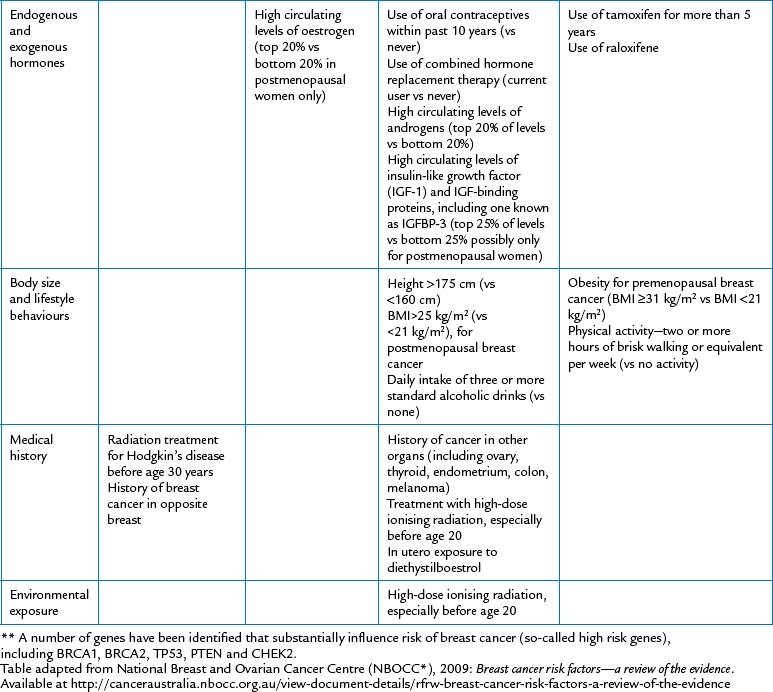

Past breast cancer increases the risk of recurrent cancer (Table 27.2). The presence of benign breast disease makes the breasts more difficult to examine; the general lumpiness conceals a new lump. Breast cancer occurring in certain family members increases risk for this woman (Table 27.2). |

|

Breast Awareness and mammograms are complementary screening measures. In the absence of proof that routine systematic breast self-examination (BSE) is effective, the Cancer Council Australia, National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre (NBOCC*), the National Screening Unit (NSU) in New Zealand, the Cancer Society of New Zealand and the New Zealand Breast Cancer Foundation advocate a less formal Breast Aware approach to encourage women to report unusual breast changes. This approach involves the woman being aware of how her breasts normally look and feel, so that she may be better able to recognise any changes (Cancer Council Australia, 2009; NBOCC*, 2009b; NSU, Cancer Society of New Zealand, New Zealand Breast Cancer Foundation, 2008). No one method a woman uses to check her breasts is recommended over another; however, what is important is that the woman both views and palpates all the breast tissue in both breasts from collarbone to below the bra-line and under the armpit. A suggested Breast Awareness approach is offered by the Cancer Council Australia (http://www.cancer.org.au/File/PolicyPublications/Position_statements/PS-Early_detection_of_breast_cancer_reviewed_May04_updatedJun09.pdf (Cancer Council Australia, 2009)). Inform the woman that if she notices any of the following changes in either of her breasts when performing regular Breast Awareness, she should contact her general practitioner without delay: • A new lump or lumpiness especially if it is in one breast • A change in the size or shape of the breast or nipple • A change in the skin over the breast such as redness or dimpling • An unusual persistent pain, especially if it is in one breast (NBOCC*, 2009b). |

|

| • Ever had mammography, a screening x-ray examination of the breasts? When was the last x-ray? | Screening mammograms are an effective way of detecting early signs of breast cancer in older women, but they are not effective in young women. Younger women’s breasts are very dense and appear like white cotton wool on a mammogram. Free screening mammograms are offered to all women over 40 years of age living in Australia. As women become older their breasts become less dense and so screening mammogram becomes an effective means of revealing cancers too small to be detected by the woman or by the most experienced examiner. Women aged 50–69 years are recommended to have a free screening mammogram every two years. In New Zealand, free screening (BreastScreen Aotearoa) is offered biannually to women aged 45–69 years. In Australia, women aged 70 years and older are also offered free screening mammogram every 2 years (Cancer Council Australia, Position statement, 2009). It is important for women to continue with Breast Awareness practices as interval lumps may become palpable between mammograms. |

| Axilla | |

| Breast tissue extends up into the axilla. Also, the axilla contains many lymph nodes. | |

| Additional history for the preadolescent | |

| Developing breasts are the most obvious sign of puberty and the focus of attention for most girls, especially in comparison to peers. Assess each girl’s perception of her own development, provide teaching and reassurance as indicated. | |

| Additional history for the pregnant female | |

| Breastfeeding provides the perfect food and antibodies for the baby, decreases risk of ear infections, promotes bonding and provides relaxation. | |

| Additional history for the menopausal woman | |

| Decreased oestrogen level causes decreased firmness. Rapid decrease in oestrogen level causes actual shrinkage. | |

| Risk factor profile for breast cancer | |

| Breast cancer is the second most common cause of cancer-related death for Australian women. However, early detection and improved treatment have increased survival rates. The outcomes for women diagnosed with breast cancer have improved significantly. The 5-year survival rate for breast cancer in non-Indigenous Australian women has increased from 73% in the 1980s to 88% in 2000–2006. As reported above, the current 5-year survival rate for Indigenous Australian women is lower and was 65% in 2002–2006 (AIHW/NBOCC*, 2009). Note the risk factors listed in Table 27.2. | Cancer Australia’s guide about risk factors for breast cancer provides a review of epidemiological studies about risk factors for breast cancer. The risk factors are graded according to their relative risk (RR). Modest RR factors are graded between 1.25 and 1.99. Moderate RR are graded as 2.00–3.99. Strong RR is graded as 4+ and factors which are potentially protective as RR<0.8 (NBOCC*, 2009a). The best way to detect a person’s risk for breast cancer is by asking the right history questions. Table 27.2 highlights risk factors for breast cancer, and from these you can fashion your questions. Be aware that most breast cancers occur in women with no identifiable risk factors except sex and age. Just because a woman does not report the cited risk factors does not mean that you or she should fail to consider breast cancer seriously. |

OBJECTIVE DATA

Objective assessment enables you to gather additional information about the patient from a direct physical examination. Irrespective of whether the person has had a clinical breast examination performed for the first time or many times, sensitivity to body image, privacy when performing the examination and awareness of cultural norms and practices should be acknowledged and provided. Remember to ensure that the room in which you perform the examination is warm and well lit. Also, warm your hands before you commence.

| Procedures and normal range of findings | Abnormal findings and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| INSPECT THE BREASTS | |

| General appearance | |

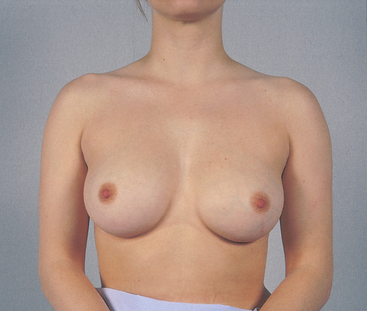

| Note symmetry of size and shape (Fig 27.8). It is common to have a slight asymmetry in size; often the left breast is slightly larger than the right. | A sudden increase in the size of one breast may signify inflammation or new growth. |

| Skin | |

| The skin is normally smooth and of even colour. Note any localised areas of redness, bulging or dimpling. Also, note any skin lesions or focal vascular pattern. A fine blue vascular network is visible normally during pregnancy. Pale linear striae, or stretch marks, often follow pregnancy. | Hyperpigmentation (darkening of the skin). Redness and heat with inflammation. Unilateral dilated superficial veins in a nonpregnant woman. Oedema (see Table 27.3). Normally no oedema is present. Oedema exaggerates the hair follicles, giving a ‘pig-skin’ or ‘orange-peel’ look (also called peau d’orange). |

| Lymphatic drainage areas | |

| Observe the axillary and supraclavicular regions. Note any bulging, discolouration or oedema. | |

| Nipple | |

| The nipples should be symmetrically placed on the same plane on the two breasts. Nipples usually protrude, although some are flat and some are inverted. They tend to stay in their original condition. Distinguish a recently retracted nipple from one that has been inverted for many years or since puberty. Normal nipple inversion may be unilateral or bilateral and usually can be pulled out (i.e. it is not fixed). | Deviation in pointing (see Table 27.3). Recent nipple retraction signifies acquired disease (see Table 27.3). |

| Note any dry scaling, any fissure or ulceration and bleeding or other discharge. | Explore any discharge, especially in the presence of a breast mass. |

| A supernumerary nipple is a normal and common variation (Fig 27.6). An extra nipple along the embryonic ‘milk line’ on the thorax or abdomen is a congenital finding. Usually, it is 5 to 6 cm below the breast near the midline and has no associated glandular tissue. It looks like a mole, although a close look reveals a tiny nipple and areola. It is not significant; merely distinguish it from a mole. | Rarely, additional glandular tissue, called a supernumerary breast, is present. |

| Manoeuvres to screen for retraction | |

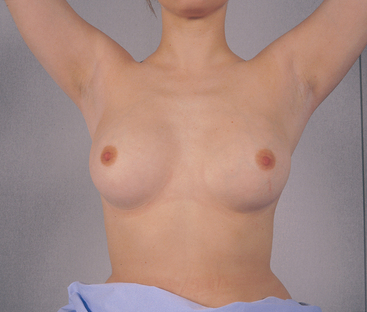

| Direct the woman to change position while you check the breasts for skin retraction signs. First ask her to lift the arms slowly over the head. Both breasts should move up symmetrically (Fig 27.9). | Retraction signs are due to fibrosis in the breast tissue, usually caused by growing neoplasms. The fibrosis shortens with time, causing contrasting signs with the normally loose breast tissue. Note a lag in movement of one breast. |

| Next ask her to push her hands onto her hips (Fig 27.10) and to push her two palms together (Fig 27.11). These maneoeuvres contract the pectoralis major muscle. A slight lifting of both breasts will occur. | Note a dimpling or a pucker, which indicates skin retraction (see Table 27.3). |

| Ask the woman with large pendulous breasts to lean forward while you support her forearms. Note the symmetrical free-forward movement of both breasts (Fig 27.12). | |

| Note fixation to chest wall or skin retraction (see Table 27.3). | |

| INSPECT AND PALPATE THE AXILLAE | |

| Examine the axillae while the woman is sitting. Inspect the skin, noting any rash or infection. Lift the woman’s arm and support it yourself, so that her muscles are loose and relaxed. Use your right hand to palpate the left axilla (Fig 27.13). Reach your fingers high into the axilla. Move them firmly down in four directions: (1) down the chest wall in a line from the middle of the axilla, (2) along the anterior border of the axilla, (3) along the posterior border and (4) along the inner aspect of the upper arm. Move the woman’s arm through range-of-motion to increase the surface area you can reach. | |

| Usually nodes are not palpable, although you may feel a small, soft, nontender node in the central group. Expect some tenderness when palpating high in the axilla. Note any enlarged and tender lymph nodes. | Nodes may enlarge with any local infection of the breast, arm or hand and with breast cancer metastases. |

| PALPATE THE BREASTS | |

| Help the woman to a supine position. Tuck a small pad under the side to be palpated and raise her arm over her head. These manoeuvres will flatten the breast tissue and displace it medially. Any significant lumps will then feel more distinct (Fig 27.14). | |

Use the pads of your first three fingers and make a gentle rotary motion on the breast. Vary your pressure so you are palpating light, medium and deep tissue in each location. Start high in the axilla and palpate down just lateral to the breast. Proceed in overlapping vertical lines ending at the sternal edge. In every pattern, take care to palpate every square inch of the breast and to examine the tail of Spence high into the axilla. Be consistent and thorough in your approach to each woman. |

|

| In nulliparous women, normal breast tissue feels firm, smooth and elastic. After pregnancy, the tissue feels softer and looser. Premenstrual engorgement is normal from increasing progesterone. This consists of a slight enlargement, a tenderness to palpation and a generalised nodularity; the lobes feel prominent and their margins more distinct. | Heat, redness and swelling in non-lactating and nonpostpartum breasts may indicate inflammation. |

| Also, normally you may feel a firm transverse ridge of compressed tissue in the lower quadrants. This is the inframammary ridge, and it is especially noticeable in large breasts. Do not confuse it with an abnormal lump. | |

| After palpating over the four breast quadrants, palpate the nipple (Fig 27.15). Note any induration or subareolar mass. With your thumb and forefinger, gently depress the nipple tissue into the well behind the areola. The tissue should move inwards easily. If the woman reports spontaneous nipple discharge, press the areola inwards with your index finger—repeat from a few different directions. If any discharge appears, note its colour and consistency. | Except in pregnancy and lactation, discharge is abnormal (see Table 27.4). Note the number of discharge droplets and the quadrant(s) producing them. Blot the discharge on a white gauze pad to ascertain its colour. Document and report any discharge to a medical practitioner. |

| For the woman with large pendulous breasts, you may palpate by using a bimanual technique (Fig 27.16). The woman is in a sitting position, leaning forwards. Support the inferior part of the breast with one hand. Use your other hand to palpate the breast tissue against your supporting hand. | |

| If the woman mentions a breast lump that she has discovered herself, examine the unaffected breast first to learn a baseline of normal consistency for this woman. If you do feel a lump or mass, note these characteristics (Fig 27.17): | |

1. Location—using the breast as a clock face, describe the distance in centimetres from the nipple (e.g. ‘7:00, 2 cm from the nipple’). Or diagram the breast in the woman’s record and mark in the location of the lump. 2. Size—judge in centimetres in three dimensions: width x length x thickness. 3. Shape—state whether the lump is oval, round, lobulated or indistinct. 4. Consistency—state whether the lump is soft, firm or hard. 5. Movable—is the lump freely movable, or is it fixed when you try to slide it over the chest wall? 6. Distinctness—is the lump solitary or multiple? 7. Nipple—is it displaced or retracted? 8. Note the skin over the lump—is it erythematous, dimpled or retracted? |

See Tables 27.5 and 27.6 for description of common breast lumps with these characteristics. |

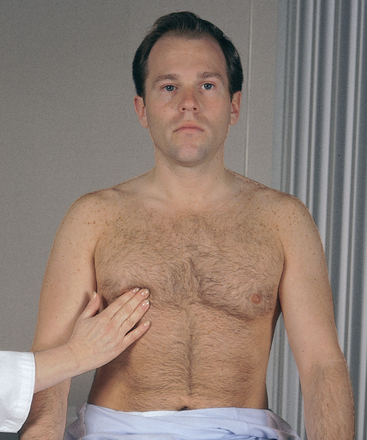

| THE MALE BREAST | |

| Your examination of the male breast can be much more abbreviated, but do not omit it. Combine a breast check technique with that of the anterior thorax. Inspect the chest wall, noting the skin surface and any lumps or swelling. Palpate the nipple area for any lump or tissue enlargement (Fig 27.18). It should feel even, with no nodules. Palpate the axillary lymph nodes. | |

| The normal male breast has a flat disc of undeveloped breast tissue beneath the nipple. The adolescent is acutely aware of his body image. Reassure him that this change is normal, common and temporary. In contrast, an obese male has an increase of fatty, not glandular, tissue. | Gynaecomastia is an enlargement of this breast tissue, making it clinically distinguishable from the other tissues in the chest wall (Fig 27.19). It feels like a smooth, firm, movable disc. This occurs normally during puberty. It usually affects only one breast and is temporary. Gynaecomastia also occurs with use of anabolic steroids, some medications and some disease states. See Table 27.8. |

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS | |

| Infants and children | |

| In the neonate, the breasts may be enlarged and visible due to maternal oestrogen crossing the placenta. They may secrete a clear or white fluid, called ‘witch’s milk’. These signs are not significant and are resolved within a few days to a few weeks. | |

| Note the position of the nipples on the prepubertal child. They should be symmetrical, just lateral to the midclavicular line, between the fourth and fifth ribs. The nipple is flat and the areola is darker pigmented. | Premature thelarche is early breast development with no other hormone-dependent signs (pubic hair, menses). |

| The adolescent | |

| Adolescent breast development usually begins on an average between 8 and 10 years of age. Expect some asymmetry during growth. (Distinguish breast development from extra adipose tissue present in obese children.) Record the stage of development using Tanner’s staging described in Table 27.1. Use the chart to teach the adolescent normal developmental stages and to assure her of her own normal progress. | Note precocious development, occurring before age 8 years. It is usually normal but also occurs with thyroid dysfunction, stilboestrol ingestion or ovarian or adrenal tumour. Note delayed development, occurring with hormonal failure or anorexia nervosa beginning before puberty or with severe malnutrition. |

| With maturing adolescents, palpate the breasts as you would with the adult. The breasts normally feel firm and uniform. Note any mass. | At this age a mass is almost always a benign fibroadenoma or a cyst (see Table 27.4). |

| Discuss Breast Awareness techniques that the young woman can routinely practise. If required, demonstrate how to use finger pads and flats of fingers to feel near the surface and deeper in the breast tissue and under the arm. | |

| The pregnant female | |

| A delicate blue vascular pattern is visible over the breasts. The breasts increase in size, as do the nipples. Jagged linear stretch marks, or striae, may develop if the breasts have a large increase. The nipples also become darker and more erectile. The areolae widen, grow darker and contain the small, scattered, elevated Montgomery’s glands. On palpation, the breasts feel more nodular, and thick yellow colostrum can be expressed after the first trimester. | |

| The lactating female | |

| Colostrum changes to milk production around the third postpartum day. At this time, the breasts may become engorged, appearing enlarged, reddened and shiny and feeling warm and hard. Frequent feeding helps drain the ducts and sinuses and stimulate milk production. | One section of the breast surface appearing red and tender indicates a blocked duct (see Table 27.7). A lactating woman who is experiencing nipple soreness or pain should be referred to a midwife or maternal and child health nurse for advice. |

| The female over 65 years | |

| On inspection, the breasts look pendulous, flattened and sagging. Nipples may be retracted but can be pulled outwards. On palpation, the breasts feel more granular, and the terminal ducts around the nipple feel more prominent and stringy. Thickening of the inframammary ridge at the lower breast is normal, and it feels more prominent with age. | Because atrophy causes shrinkage of normal glandular tissue, cancer detection is somewhat easier. Any palpable lump should be referred. |

| Reinforce the value of Breast Awareness. Women over 50 years old have an increased risk of breast cancer. |

TABLE 27.3 Signs of retraction and inflammation in the breast

|

| Dimpling |

| The shallow dimple (also called a skin tether) shown here is a sign of skin retraction. Cancer causes fibrosis, which contracts the suspensory ligaments. The dimple may be apparent at rest, with compression or with lifting of the arms. Also note the distortion of the areola here as the fibrosis pulls the nipple towards it. |

|

| Oedema (peau d’orange) |

| Lymphatic obstruction produces oedema. This thickens the skin and exaggerates the hair follicles, giving a pig-skin or orange-peel look. This condition suggests cancer. Oedema usually begins in the skin around and beneath the areola, the most dependent area of the breast. Also note nipple infiltration here. |

|

| Deviation in nipple pointing |

| An underlying cancer causes fibrosis in the mammary ducts, which pulls the nipple angle towards it. Here, note the swelling behind the right nipple and that the nipple tilts laterally. |

|

| Fixation |

| Asymmetry, distortion or decreased mobility with the elevated arm manoeuvre. As cancer becomes invasive, the fibrosis fixes the breast to the underlying pectoral muscles. Here, note the right breast is held against the chest wall. |

| Nipple retraction (not illustrated) |

| The retracted nipple looks flatter and broader, like an underlying crater. A recent retraction suggests cancer, which causes fibrosis of the whole duct system and pulls in the nipple. It also may occur with benign lesions such as ectasia of the ducts. Do not confuse retraction with the normal long-standing type of nipple inversion, which has no broadening and is not fixed. |

|

| Benign breast disease (formerly fibrocystic breast disease) |

Multiple tender masses. ‘Fibrocystic disease’ is a meaningless term because it covers too many entities. Actually, six diagnostic categories exist, based on symptoms and physical findings (Love and Lindsey, 2005): • Swelling and tenderness (cyclic discomfort) • Mastalgia (severe pain, both cyclic and noncyclic) • Nodularity (significant lumpiness, both cyclic and noncyclic) • Dominant lumps (including cysts and fibroadenomas) • Nipple discharge (including intraductal papilloma and duct ectasia) • Infections and inflammations (including subareolar abscess, lactational mastitis, breast abscess and Mondor’s disease) |

| About 50% of all women have some form of benign breast disease. Nodularity occurs bilaterally; regular, firm nodules that are mobile, well demarcated and feel rubbery, like small water balloons. Pain may be dull, heavy and cyclic or just before menses as nodules enlarge. Some women have nodularity but no pain and vice versa. Cysts are discrete, fluid-filled sacs. Dominant lumps and nipple discharge must be investigated carefully and may need biopsy to rule out cancer. Nodularity itself is not premalignant but may produce difficulty in detecting other cancerous lumps. |

|

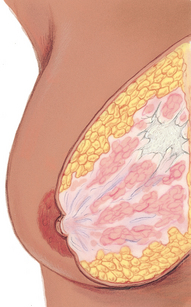

| Cancer |

| Solitary unilateral nontender mass. Single focus in one area, although it may be interspersed with other nodules. Solid, hard, dense and fixed to underlying tissues or skin as cancer becomes invasive. Borders are irregular and poorly delineated. Grows constantly. Often painless, although the person may have pain. Most common in upper outer quadrant. Usually found in women 30 to 80 years of age; increased risk in ages 40 to 44 years and in women older than 50 years. As cancer advances, signs include firm or hard irregular axillary nodes; skin dimpling; nipple retraction, elevation and discharge. |

|

| Fibroadenoma |

| Solitary nontender mass. A category of benign breast disease that deserves mention because of its frequency and characteristic appearance. Solid, firm, rubbery and elastic. Round, oval or lobulated; 1 to 5 cm. Freely movable, slippery; fingers slide it easily through tissue. Most common between 15 and 30 years of age but can occur up to age 55 years. Grows quickly and constantly. Benign, although it must be diagnosed by biopsy. |

TABLE 27.6 Abnormal nipple discharge

TABLE 27.7 Disorders occurring during lactation

|

| Plugged duct |

| A fairly common and not serious condition. One milk duct is clogged. One section of the breast is tender; may be reddened. No infection. It is important to keep breast as empty as possible and milk flowing. The woman should nurse her baby frequently, on affected side first to ensure complete emptying, and manually express any remaining milk. A plugged duct usually resolves in less than 1 day. |

|

| Mastitis |

| An inflammatory mass before abscess formation. Usually occurs in single quadrant. Area is red, swollen, tender, very hot and hard, here forming outwards from areola upper edge, in right breast. Also the woman has a headache, malaise, fever, chills and sweating, increased pulse, flu-like symptoms. May occur during first 4 months of lactation from infection or from stasis from plugged duct. Treat with rest, local heat to area, antibiotics and frequent nursing to keep breast as empty as possible. Must not wean now or the breast will become engorged and the pain will increase. Mother’s antibiotic not harmful to infant. Usually resolves in 2 to 3 days. |

|

| Breast abscess |

| A rare complication of generalised infection (e.g. mastitis) if untreated. A pocket of pus accumulates in one local area. Here extensive nipple oedema, and abscess is ‘pointing’ at 3:00 on areolar margin. Must temporarily discontinue nursing on affected breast; manually express milk and discard. Continue to nurse on unaffected side. Treat with antibiotics, surgical incision and drainage. |

TABLE 27.8 Abnormalities in the male breast

Summary Checklist Breasts and regional lymphatics exam

1. Inspect breasts as the woman sits, raises arms overhead, pushes hands on hips, leans forwards

2. Inspect the supraclavicular and infraclavicular areas

3. Palpate the axillae and regional lymph nodes

4. With woman supine, palpate the breast tissue, including tail of Spence, the nipples and areolae

Promoting a healthy lifestyle Education on Breast Awareness

Finish your own assessment first, and then discuss breast awareness strategies. Remember to reinforce that there are no right or wrong Breast Awareness techniques. If the woman is unsure what she should do, suggest she adopt behaviours that are comfortable to do from time to time. For example, view her breasts in the mirror when dressing or undressing. Feel her breasts while in the shower or bath, lying down or while dressing. It is important that the woman feels all her breast tissue, from the collarbone to below the bra-line, and under the armpit (Cancer Council Australia, 2009). You may be required to demonstrate how to use fingers to feel surface and deeper breast tissue. Encourage the woman to palpate her own breasts while you are there to monitor her technique and provide positive reinforcement.

Stress that Breast Awareness will familiarise the woman with her own breasts and their normal variation. Emphasise the absence of lumps (not the presence of them). However, do encourage her to report any unusual finding promptly to her general practitioner.

While educating, focus on the positive aspects of Breast Awareness. Avoid citing frightening mortality statistics about breast cancer. This may generate excessive fear and denial that actually obstructs a woman’s self-care action. Rather, be selective in your choice of factual material:

• The majority of women will never get breast cancer.

• The great majority of breast lumps are benign.

• Early detection of breast cancer is important; if the cancer is localised to the breast at diagnosis, the survival rate is close to 98%.

Emphasise self-care through knowledge of risk factors and Breast Awareness to increase confidence in detecting abnormalities and early referral for any suspicious findings.

Educational materials are helpful reinforcements. The NBOCC* provide a simple and fun video on breast check techniques (titled ‘Cheeky Check-up’). Encourage the woman to view this material—http://www.cheekycheckup.com.au/—to see how easy it is to be Breast Aware.

Promoting a healthy lifestyle Assessing breast cancer risk

Breast cancer screening tool

During a clinical breast examination, the opportunity often arises to review the individual’s Breast Awareness technique and dates for scheduled screening mammogram. It is also an opportunity to assess the individual’s breast cancer risk, including family history.

The use of breast cancer risk assessment tools in the clinical setting has the potential to improve health substantially by reducing breast cancer incidence through cancer prevention and by more effective early detection programs for high-risk individuals.

Cancer Australia provides a simple-to-use breast and ovarian cancer screening tool. The user-friendly, interactive calculator is intended for use by women who have not had breast or ovarian cancer. The screening tool helps women to gain a good understanding of their level of risk for breast cancer compared to another woman of a similar age group. The tool is available at the NBOCC* website: http://nbocc.org.au/risk/yourrisk.html

DOCUMENTATION AND CRITICAL THINKING

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY

JG is a 32-year-old female high school teacher, married, with no children. She reports good health until finding ‘lump in right breast 2 weeks ago’.

Subjective

2 weeks ago noticed lump in R breast on self-examination. Lump firm, nonmovable area ‘the size of a pea’, in upper outer quadrant of breast, tender on touch only. No skin changes, no nipple discharge, on no medications. Last breast exam by general practitioner 3 months before was reported normal. Did not notice lump previously. No history of breast disease in self or family.

2 days prior saw general practitioner, who confirmed presence of lump and recommended mammogram and breast ultrasound. Last menstrual period 2½ weeks ago. States the last 2 days has been so nervous has been unable to sleep well or to concentrate at work. ‘I just know it’s cancer.’

Objective

Voice trembling and breathless during history. Sitting posture stiff and rigid. B/P 148/78. T 37°C. HR 92/min. Resps 16/min.

Inspection: Breasts symmetrical, nipples everted. No skin lesions, no dimpling, no retraction, no fixation.

Palpation: Left breast firm, no mass, no tenderness, no discharge. Right breast firm, with 2 cm × 2 cm × 1 cm mass at 10 o’clock position, 5 cm from the nipple. Lump is firm, oval, with smooth discrete borders, nonmovable, tender to palpation. No other mass. No discharge. No lymphadenopathy.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008: Cancer in Australia: an overview, 2008. Cat. no. CAN 42, Canberra, 2008, AIHW.

AIHW and National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre (NBOCC*): Breast cancer in Australia: an overview, 2009. Cancer series no. 50. Cat. no. 46. Canberra, 2009, AIHW. Available at http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10852.

Boehmke M, Dickerson S. The diagnosis of breast cancer: transition from health to illness. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1121–1127.

Butts SF, Seifer DB. Racial and ethnic differences in reproductive potential across the life cycle. Fertility and Sterility. 2010;93(3):681–690.

Cancer Control Council of NZ. Mapping progress 11: phase 1 of the Cancer Council. Available at http://www.cancercontrol.org.nz/, 2008.

Cancer Council Australia. Position statement. Early detection of breast cancer. Updated June 2009. Available at http://www.cancer.org.au/File/PolicyPublications/Position_statements/PS-Early_detection_of_breast_cancer_reviewed_May04_updated_Jun09.pdf.

Colditz GA, Rosner B. Cumulative risk of breast cancer to age 70 years according to risk factor status: Data from the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:950–964.

Cunningham J, Rumbold AR, Zhang X, et al, Incidence, aetiology, and outcomes of cancer in Indigenous peoples of Australia. Lancet Oncology. 2008;9:585–595. Available at http://oncology.telancet.com.

Herman-Giddens ME, et al. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the pediatric research in office settings network. Pediatrics. 1997;99:505–512.

Jacobs E, et al. Limited English proficiency and breast and cervical cancer screening in a multiethnic population. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1410–1416.

Kellen E, et al. Lifestyle changes and breast cancer prognosis: a review. Breast Cancer Research Treatment. 2009;114:13–22.

Klein S. Evaluation of palpable breast masses. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1731–1738.

Love S, Lindsey K. Dr. Susan Love’s breast book, 4th edn. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Lifelong Books, 2005.

Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303.

McDonald S, Saslow D, Alciati M. Performance and reporting of clinical breast examination: a review of the literature. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:345–361.

Morrell RM, et al. Breast cancer related lymphedema. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1480–1484.

National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre (NBOCC*): Breast cancer risk factors: a review of the evidence, Surry Hills, NSW, 2009a, NBOCC*. Available at http://nbocc.org.au/view-document-details/rfrw-breast-cancer-risk-factors-a-review-of-the-evidence.

National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre (NBOCC*): Early detection of breast cancer—NBOCC position statement, updated Dec. 2009, Surry Hills, NSW, 2009b, NBOCC*. Available at http://nbocc.org.au/our-organisation/position-statements/early-detection-of-breast-cancer.

National Screening Unit (NSU). Cancer Society of New Zealand, New Zealand Breast Cancer Foundation, 2008: Position statement on breast awareness. Available at http://www.nsu.govt.nz/current-nsu-programmes/559.asp.

New Zealand Breast Cancer Foundation. New Zealand breast cancer facts. Available at http://www.nzbcf.org.nz/, 2010.

New Zealand Ministry of Health (MOH), Cancer new registrations and deaths 2005. MOH, Wellington, 2009. Available at http://moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/cancer-reg-deaths-2005.

Shahid S, Thompson SC. An overview of cancer and beliefs about the disease in Indigenous people of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the US. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2009;32(2):109–118.

Tanner JM. Growth at adolescence, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1962.

Thompson CA, Thompson PA. Dietary patterns, risk and prognosis of breast cancer. Future Oncology. 2009;5(8):1257–1269.

Watson LF, Taft AJ, Lee C. Associations of self-reported violence with age at menarche, first intercourse, and first birth among a national population sample of young Australian women. Women’s Health Issues. 2007;17:281–289.

Wirfält E, et al. Fat from different foods show diverging relations with breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. Nutr Cancer. 2005;53:135–143.

Yamamoto DS, Viale PH. Does every breast lump need to be worked up despite previous diagnoses? Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2006;10:821–823.