Chapter Twenty-eight The pregnant female

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy and childbirth result in significant physiological changes in the woman. These changes include the growth of the fetus, placenta and uterus, as well as complex endocrine and circulatory changes. The following gives you a brief overview of the changes to structure and function that occur during normal pregnancy.

PREGNANCY AND THE ENDOCRINE PLACENTA

The first day of the menses is day 1 of the menstrual cycle. For the first 14 days of the cycle, one or more follicles in the ovary develops and matures. One follicle grows faster than the others, and on day 14 of the menstrual cycle this dominant follicle ruptures and ovulation occurs. This is dependent on the woman having a 28 day menstrual cycle. Some women have a longer or shorter cycle. If the ovum meets viable sperm, fertilisation occurs somewhere in the oviduct (fallopian tube). The remaining cells in the follicle form the corpus luteum, or ‘yellow body’, which makes important hormones. Chief among these is progesterone, which prevents the sloughing of the endometrial wall, ensuring a rich vascular network into which the fertilised ovum will implant.

The fertilised ovum, now called the blastocyst, continues to divide, differentiate and grow rapidly. Specialised cells in the blastocyst produce human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which stimulates the corpus luteum to continue making progesterone. Between days 20 and 24, the blastocyst implants into the wall of the uterus, which may cause a small amount of vaginal bleeding. A specialised layer of cells around the blastocyst becomes the placenta. The placenta starts to produce progesterone to support the pregnancy at 7 weeks and takes over this function completely from the corpus luteum at about 10 weeks.

The placenta functions as an endocrine organ and produces several hormones. These hormones help in the growth and maintenance of the fetus, and they direct changes in the woman’s body to prepare for birth and lactation. The hCG stimulates the rise in progesterone during pregnancy. Progesterone maintains the endometrium around the fetus, increases the alveoli in the breast and keeps the uterus in a quiescent state. Oestrogen stimulates the duct formation in the breast, increases the weight of the uterus and increases certain receptors in the uterus that are important at birth.

The average length of pregnancy is 280 days from the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP), which is equal to 40 weeks, 10 lunar months or 9 calendar months. Note that this includes the 2 weeks when the follicle was maturing but before conception actually occurred. Pregnancy is divided into three trimesters: (1) the first 12 weeks, (2) from 13 to 27 weeks and (3) from 28 weeks to delivery.

A woman who is pregnant for the first time is called a primigravida. After she delivers, she is called a primipara. The multigravida is a pregnant woman who has previously carried a fetus to the point of viability. She is a multipara after delivery. Any pregnant woman might be called a gravida. Commonly used terminology is G (gravida), P (parity), TOP (termination of pregnancy), MC (miscarriage).

CHANGES DURING NORMAL PREGNANCY

Pregnancy is confirmed by three types of signs and symptoms. Presumptive signs are those the woman experiences, such as amenorrhoea, breast changes, nausea, fatigue and increased urinary frequency. Probable signs are those detected by the examiner, such as an enlarged uterus and changes to the vagina and cervix. Positive signs of pregnancy are those that are direct evidence of the fetus, such as a positive pregnancy test, the auscultation of fetal heart sounds or positive cardiac activity on ultrasound.

First trimester

Conception occurs on approximately the 14th day of the menstrual cycle. The blastocyst (developing fertilised ovum) implants in the uterus 6 to 10 days after conception, sometimes accompanied by a small amount of painless bleeding. This is often called an implantation bleed and may be interpreted as a menstrual period (Cunningham et al, 2010). There is no evidence that implantation causes vaginal bleeding (Pairman et al, 2010). The serum hCG becomes positive after implantation when it is first detectable in maternal serum at approximately 8 to 11 days after conception.

The following menstrual period is missed. At the time of the missed menses, hCG can be detected in the urine. Breast tingling and tenderness begin as the rising oestrogen levels promote mammary growth and development of the ductal system; progesterone stimulates the alveolar system as well as the mammary growth. Chorionic somatomammotropin (also called human placental lactogen or hPL), also produced by the placenta, stimulates breast growth and exerts lactogenic properties (Varney, 2004). Nausea and vomiting will be experienced by 80–85% of women with 52% of these vomiting (Pairman et al, 2010). Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy is not well understood but may involve the hormonal changes of pregnancy, reduced gastric motility, carbohydrate deficiency, an enlarging uterus and psychological factors (Henderson and Macdonald, 2004). Fatigue is common and may be related to the initial fall in metabolic rate that occurs in early pregnancy (Varney, 2004).

Oestrogen, and possibly progesterone, cause hypertrophy of the uterine muscle cells, and uterine blood vessels and lymphatics enlarge. The uterus becomes globular in shape, softens and flexes easily over cervix (Hegar’s sign). This causes compression of the bladder, which results in urinary frequency. Increased vascularity, congestion and oedema cause the cervix to soften (Goodell’s sign) and become bluish purple (Chadwick’s sign).

Early first-trimester blood pressures (BPs) reflect prepregnancy values. In the 7th gestational week, BP begins to drop until mid pregnancy as a result of reduced peripheral vascular resistance. The BP gradually returns to the nonpregnant baseline by term. Systemic vascular resistance decreases from the vasodilatory effect of progesterone and prostaglandins and possibly because of the low resistance of the placental bed (Creasy and Resnick, 2004).

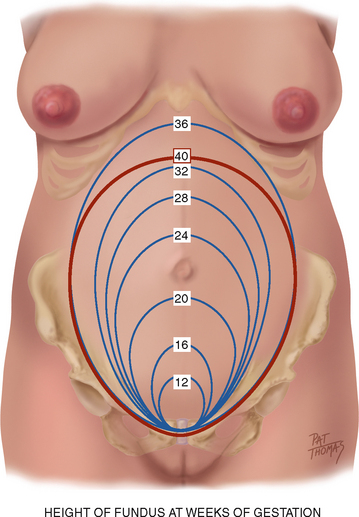

At the end of 9 weeks, the embryonic period ends and the fetal period begins, at which time major structures are present (Varney, 2004). The fetal heart can be heard by Doppler ultrasound between 9 and 12 weeks. The uterus may be palpated just above the symphysis pubis at about 12 weeks. See Figure 28.1 for growth of the uterine fundus during the first trimester.

Second trimester

By weeks 12 to 16, the nausea, vomiting, fatigue and urinary frequency of the first trimester improve. The woman recognises fetal movement (‘quickening’) at approximately 18 to 20 weeks (the multigravida earlier). Breast enlargement continues, the nipples become more erect, the Montgomery’s tubercules enlarge and the veins of the breast may become more visible on the skin surface due to increased blood supply. Colostrum, the precursor of milk, may be expressed from the nipples. Colostrum is yellow in colour, and is higher in minerals, sodium and protein but lower in carbohydrate, fat and vitamins than mature milk. Colostrum also contains antibodies and immune cells, which are protective for the newborn during its first days of life until mature milk production begins (Pairman et al, 2010).

The areola and nipples darken, it is thought, because oestrogen and progesterone have a melanocyte-stimulating effect, and melanocyte-stimulating hormone levels escalate from the second month of pregnancy until delivery. For the same reason, the midline of the abdominal skin becomes pigmented and is called the linea nigra. You may note striae gravidarum (‘stretch marks’) on the breast, abdomen and areas of weight gain.

During the second trimester, systolic BP may be 2 to 8 mmHg lower and diastolic BP 5 to 15 mmHg lower than prepregnancy levels (Cunningham et al, 2010). This drop is most pronounced at 20 weeks and may cause symptoms of dizziness and faintness, particularly after rising quickly. Stomach displacement from the enlarging uterus and altered oesophageal sphincter and gastric tone as a result of progesterone predispose the woman to heartburn. Intestines are also displaced by the growing uterus, and tone and motility are decreased because of the action of progesterone, often causing constipation. The gallbladder, possibly resulting from the action of progesterone on its smooth muscle, empties sluggishly and may become distended. The stasis of bile, together with the increased cholesterol saturation of pregnancy, predisposes some women to gallstone formation.

Progesterone and, to a lesser degree, oestrogen cause increased respiratory effort during pregnancy by increasing tidal volume. Haemoglobin, and therefore oxygen-carrying capacity, also increases. Increased tidal volume causes a slight drop in partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (Paco2), causing the woman to occasionally have dyspnoea (Cunningham et al, 2010).

The high level of oestrogen during pregnancy causes an increase in the major thyroxine transport protein, thyroxine-binding globulin. Several thyroid-stimulating factors of placental origin are produced. The thyroid gland enlarges as a result of hyperplasia and increased vascularity. Thyroid function plays a vital role in maternal–fetal morbidity and mortality. Maternal hypothyroidism, which occurs in about 1% of all pregnancies, increases the risk of intrauterine fetal death, preeclampsia, low birth weight, spontaneous miscarriage and abruptio placentae (Henderson and Macdonald, 2004). Even mild maternal hypothyroidism adversely affects the fetus, leading to lower IQ performance (Haddow et al, 1999).

Cutaneous blood flow is augmented during pregnancy caused by decreased vascular resistance, presumably helping to dissipate heat generated by increased metabolism. Gums may hypertrophy and bleed easily. This condition is called gingivitis or epulis of pregnancy, and it occurs as a result of growth of the capillaries of the gums (Cunningham et al, 2010). For the same reason, nosebleeds may occur more frequently than usual. Pregnant women with periodontal disease, a chronic local oral infection, are at risk for preterm delivery (PTD). Untreated, this may lead to a systemic infection that affects the maternal levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE-2) (Boggess, 2003).

Fetal heart sounds can be heard using a portable Doppler ultrasound at approximately 17 to 19 weeks. The fetal outline is palpable through the abdominal wall at approximately 20 weeks. Figure 28.1 illustrates the growth of the uterine fundus during the second trimester.

Third trimester

Blood volume, which increased rapidly during the second trimester, peaks in the middle of the third trimester at approximately 45% greater than the prepregnancy level and plateaus thereafter. This volume is greater in multiple gestations (Creasy and Resnick, 2004). Erythrocyte mass increases by 20% to 30% (caused by an increase in erythropoiesis, mediated by progesterone, oestrogen and placental chorionic somatomammotropin). However, plasma volume increases slightly more, causing a slight haemodilution and a small drop in haematocrit. BP slowly rises again to approximately the prepregnant level (Cunningham et al, 2010).

Uterine enlargement causes the diaphragm to rise and the shape of the rib cage to widen at the base. Decreased space for lung expansion may cause a sense of shortness of breath. The rising diaphragm displaces the heart up and to the left. Cardiac output, stroke volume and force of contraction are increased. The pulse rate rises 15 to 20 beats per minute (Creasy and Resnick, 2004). Because of the increase in blood volume, a functional systolic murmur can usually be heard in more than 95% of pregnant women (Creasy and Resnick, 2004).

Oedema of the lower extremities may occur as a result of the enlarging fetus impeding venous return, and from lower colloid osmotic pressure. The oedema worsens with dependency, such as prolonged standing. Varicosities, which have a familial tendency, may form or enlarge from progesterone-induced vascular relaxation. Also causing varicosities is the engorgement caused by the weight of the full uterus compressing the inferior vena cava and the vessels of the pelvic area, resulting in venous congestion in the legs, vulva and rectum. Haemorrhoids are varicosities of the rectum that are worsened by constipation, which occurs from relaxation of the large bowel by progesterone.

Progressive lordosis (an inward curvature of the lumbar spine) occurs to compensate for the shifting centre of balance caused by the anteriorly enlarging uterus, predisposing the woman to backaches. Slumping of the shoulders and anterior flexion of the neck from the increasing weight of the breasts may cause aching and numbness of the arms and hands as a result of compression of the median and ulnar nerves in the arm (Varney, 2004), commonly referred to as carpal tunnel syndrome.

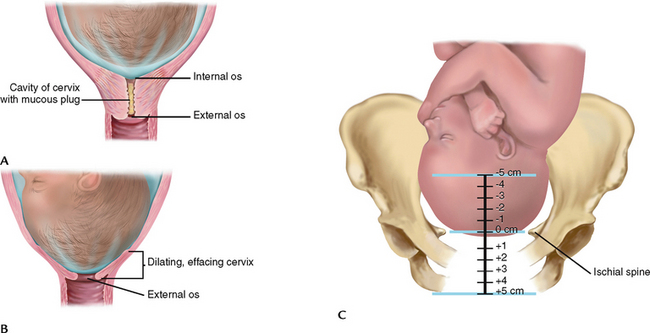

Approximately 2 weeks before going into labour, the primigravida experiences engagement (also called ‘lightening’ or ‘dropping’) when the fetal head moves down into the pelvis. Symptoms include a lower-appearing and smaller-measuring fundus, urinary frequency, increased vaginal secretions from increased pelvic congestion and increased lung capacity. In the multigravida, the fetus may move down at any time in late pregnancy or often not until labour. The cervix, in preparation for labour, begins to thin (efface) and open (dilate). A thick mucous plug (operculum), formed in the cervix as a mechanical barrier during pregnancy, is expelled at variable times before or during labour. Between 37 and 42 weeks, the pregnancy is considered term. After 42 weeks, the pregnancy is considered postterm.

Determining weeks of gestation

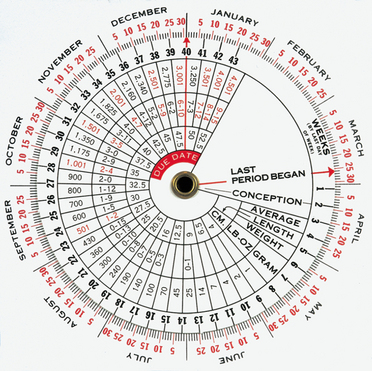

The estimated due date or EDD, being 282 days (NICE guidelines, 2008) from the first day of the LMP, may be calculated by using Nägele’s rule. That is, determine the first day of the last normal menstrual period (normal in timing, length, premenstrual symptoms and amount of flow and cramping). Using the first day of the LMP, add 7 days and 9 months. This date is the EDD. This date can then be used with a pregnancy wheel, on which the EDD arrow is set—then the present date will be pointing to the present week’s gestation (Fig 28.2). The number of weeks of gestation also can be estimated by physical examination (bimanual and pelvic examination), by measurement of the maternal serum hCG, by dating ultrasound (10–14 weeks) and by signs such as the first perceived fetal movement. There will always be variability related to the EDD and women need to be aware of this. Individual variation must be accounted for.

Weight gain in pregnancy

The amount of weight gained by term represents a baby, amniotic fluid, placenta, increased uterine size, increased blood volume, increased extravascular fluid, maternal fat stores and increased breast size. Weight gain during pregnancy reflects both the mother and the fetus and is approximately 62% water gain, 30% fat gain and 8% protein. Approximately 25% of the total gain is attributed to the fetus, 11% to the placenta and amniotic fluid and the remainder to the mother (Blackburn, 2007). There are no Australian or New Zealand national guidelines for healthy weight gain during pregnancy; however, there are guidelines for healthy eating during pregnancy (Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing, 2009). The amount of weight gain that is considered healthy during pregnancy is dependent on the woman’s prepregnancy body mass index.

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

In industrialised countries, the risks for the adolescent who is pregnant are largely psychosocial. The young woman is at risk for the downward cycle of poverty beginning with an incomplete education, failure to limit family size and continuing with failure to establish a vocation and become independent. She may be unprepared emotionally to be a mother. Her social situation may be stressful. She may not have the support of her family, her partner or his family. Medical risks for the pregnant adolescent are generally related to poverty, inadequate nutrition, substance abuse and sometimes sexually transmitted infections (STIs), poor health before pregnancy and emotional and physical abuse from her partner.

While evidence suggests the adolescent is at risk for pregnancy-induced hypertension, preterm birth and perinatal mortality (Henderson and Macdonald, 2004), it is unclear whether these risks are associated with physiological change or social factors. The adolescent, for social reasons, often seeks healthcare later, and early prenatal care has been shown to provide optimal management. In developing countries, maternal mortality for pregnant teenagers is a major concern because of hypertension, embolism, ectopic pregnancy and complications from pregnancy termination where abortion is illegal (Cunningham et al, 2010).

On the other hand, many baby boomers have delayed childbearing, and since the advent of assisted conception, more women older than age 35 years are now becoming pregnant. Women of ‘advanced maternal age’ (after age 35 years) are often more prepared emotionally and financially to parent; however, they are more at risk for infertility and age-related anomalies. Although the birth rate has more than doubled between 1978 and 2000 for women aged 35 to 44 years, fertility declines with advancing maternal age (March of Dimes, 2002). This decline is due in part to a decrease in the number and health of eggs to be ovulated, a decrease in ovulation and other gynaecological conditions such as endometriosis and early onset of menopause.

Once conception has occurred, the woman of advanced maternal age is at increased risk of having a child with congenital abnormalities, particularly Down syndrome. At age 25 years the risk of Down syndrome is 1 in 1250; at age 35 years, a 1 in 400 risk; at age 40 years, a 1 in 100 risk; and at age 45 years, a 1 in 30 risk (March of Dimes, 2002).

There are various screening combinations that be used for detecting trisomy 21 (Down syndrome). Women 35 years and older are offered genetic counselling and prenatal screening such as chorionic villus sampling (CVS), in which a small sample of chorionic villi is removed, either abdominally or transvaginally, to analyse for genetic make-up; this is performed in the first trimester. Amniocentesis, in which a small amount of amniotic fluid is removed to analyse genetic make-up, can be done in the second trimester. A further screen is integrated prenatal risk profile (IPRP), which uses a first-trimester ultrasound between 10 to 12 weeks to measure fetal nuchal translucency (NT), which is an abnormal fluid collection at the nape of the fetal neck.

In the second trimester, maternal serum is analysed for alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and hCG. Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis (CF) is offered to check the inherited genetic disease affecting breathing and digestion. Both parents need to be carriers to pass the condition on to the fetus (a 25% chance (1 in 4) that the child will have CF).

Because the incidence of chronic diseases increases with age, women over age 35 years who are pregnant more often have medical complications such as diabetes, obesity and hypertension (Cunningham et al, 2010). The increased incidence of hypertension causes an increase in placental abruption and preeclampsia. Hypertension, in turn, increases intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). More women of advanced maternal age have placenta previa, placental abruption and uterine rupture. They have more spontaneous abortions, in part because of the increase in genetically abnormal embryos.

Advanced maternal age (≥35 years) is itself considered a risk factor for maternal death. There are still wide variances in maternal deaths between developed and developing countries. Maternal deaths worldwide are due to severe bleeding (mostly postpartum), infection (soon after birth), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and obstructed labour. Indirect causes are diseases that complicate pregnancy such as malaria, anaemia, HIV, poor health at conception and lack of adequate care (World Health Organization (WHO), 2010).

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Some complications of pregnancy occur more frequently in certain groups. Women who live in developing countries may not have the advantages of a skilled attendant for pregnancy and birth, let alone technology. Every minute a woman somewhere dies in pregnancy or childbirth. This adds up to 1000 women dying each day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth. The majority of these deaths occur in developing countries (WHO, 2010).

The number of worldwide maternal deaths is the product of the total number of births and obstetrical risks per birth, where the maternal mortality ratio is a measure of the risk of death once a woman has become pregnant. This ratio is based on the overall probability of becoming pregnant and the probability of dying because of the pregnancy and that of the probability of dying across a woman’s reproductive years. More than half of maternal deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa and approximately one-third in South-East Asia. The maternal mortality ratio in developing countries is 290 per 100 000 births compared with 14 per 100 000 in developed countries (WHO, 2010).

In Australia in 2008 there were 15 011 births registered where one or both of the parents identified as Indigenous (5% of all births). Of these births both parents identified as Indigenous in 32% with the mother only in 41% (Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet, 2010). While the maternal death rates are low in Australia, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) report Maternal deaths in Australia 2003–2005 found that for Indigenous women there were 21.6 deaths per 100 000 births compared with 7.9 deaths per 100 000 for non-Indigenous women (Sullivan, Hall and King, 2008). There are similar low maternal death rates in New Zealand with a ratio of 13.7 deaths per 100 000 births (Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee, 2010).

Pregnancy is a life event with profound psychological and social meaning for the woman and for her family and community. All cultures recognise pregnancy as a unique period in a woman’s life that surrounds special customs and beliefs that have been developed throughout the ages. The spiritual practices and beliefs provide her either with or without support. Understanding what role these beliefs and practices play in the woman’s pregnancy helps the healthcare provider to acknowledge the cultural differences. Pregnancy is intensely personal and involves such charged issues as sexuality, relationships, contraception, nutritional practices, maternal weight gain and abortion. You must be sensitive to these issues. You may begin by inquiring whether the woman or her significant others have any special requests. This communicates your intention to respect cultural differences and preferences. A continuing rapport will help enable the woman to bring up issues as they develop.

A woman’s resistance to an action or a suggestion by the clinician may represent a cultural issue. Such issues may also be thought of differently by the woman and one or more of her significant others, and such situations must be handled with care. Examples of culturally charged issues are dietary practices, sexuality during and after pregnancy, preference for gender of care provider, preference for gender of infant and contraceptive usage. Use your skill to understand such preferences within a cultural context and accept rather than judge the person. Whenever safe and possible, respect such wishes. This enhances the success of the birth in its psychological and social dimensions.

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Pregnancy assessment is most commonly conducted by midwives. However, registered nurses may need to conduct a health assessment if the woman is seeking healthcare for a nonpregnancy-related health issue. During pregnancy an extensive health history is obtained at the first antenatal visit. This provides a comprehensive database for monitoring the progress of the mother’s and baby’s health throughout the pregnancy. It also gives the midwife insight into the mother’s needs and concerns.

| Assessment guidelines and normal findings | Clinical significance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| Using Nägele’s rule, calculate the EDD with this date. With a pregnancy wheel, determine the current number of weeks of gestation. | |

| • Have you ever had surgery of the cervix or uterus? | Cervical surgery may affect the integrity of the cervix during pregnancy. During labour it may impede cervical dilation. Uterine surgery increases risk for uterine rupture during pregnancy and labour. |

| • Do you have any known history of or exposure to genital herpes? | Onset during pregnancy is potentially teratogenic (i.e. causing physical defects in the developing fetus) and an active lesion at delivery precludes vaginal birth. |

| • When was your last Pap smear? Have you ever had an abnormal smear or a colposcopy? | A Pap smear should be done every two years and if the woman has not had one previously one should be done. An abnormal Pap smear in the past may have a negative effect on the pregnancy or delivery depending on whether there was surgery of the cervix involved. |

| • Do you have any history of fibroids or uterine abnormalities? | May increase risk for ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, preterm labour. |

| • Have you ever had gonorrhoea, chlamydia, syphilis, trichomoniasis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)? | STIs increase the risk of premature rupture of membranes, preterm labour, postpartum maternal and fetal infections. |

| • Are you in a relationship with one person? | Establishes the likely risk for STIs. |

| • Were you born preterm ? | Patients who themselves were preterm infants are at increased risk for preterm labour. |

| • Have you had a mammogram, breast biopsy, breast implants, breast reduction lumpectomy or mastectomy? | Approximately 2% to 3% of all breast cancers in women under age 40 years occur concurrently with pregnancy or lactation (Gabbe et al, 2007). Implants or reduction will have an effect on breastfeeding. |

| • Do you have a history of infertility? Have you used assisted reproductive technology? | In the case of donor eggs, the age of the egg donor is used in calculating genetic testing. |

| • How did you experience previous pregnancies and deliveries? Tell me the year of the pregnancy, labour and birth outcome (including spontaneous miscarriages, elective abortions or ectopic pregnancies and postnatal outcomes). | |

| • Tell me how big your babies were, what sex they were and whether they were born alive. | A small infant may indicate prematurity or intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)— complications that are repeatable. A large infant may indicate gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) (also repeatable). Conversely, birth weights of other children may indicate a ‘constitutional size’–e.g. the tendency of a couple to conceive smaller but normal children. Also, the woman’s pelvis has been ‘proven’ to the weight of the largest baby born vaginally. |

| • Have you ever had a caesarean section (CS)? If so, what was the indication? At how many centimetres of dilation, if any, was the surgery performed? What type of uterine incision was made? (Confirming records of this surgery must be obtained.) Have you ever had a vaginal birth after a caesarean section (VBAC)? | The woman who has had surgery on her uterus is at risk for uterine rupture during pregnancy and labour. The vertical, or ‘classical’, incision carries a higher risk of rupture and mandates that all subsequent deliveries be by cesarean section. The ‘low transverse’ or horizontal incision carries a low risk and subsequent deliveries may be vaginal. Note that the direction of the skin scar does not necessarily tell how the uterus was incised. |

| • Did you breastfeed your previous babies? How was that experience for you? How long did you continue to breastfeed with each baby? | The woman’s experience and knowledge base will shape your teaching and support. |

| • Did you have any history of breastfeeding problems such as mastitis? | A poor or painful previous experience increases the need for breastfeeding support after this pregnancy. |

| • What method of contraception did you use most recently and when did you discontinue it? | Recent use of oral contraception or other hormonal contraceptives may cause delayed ovulation and irregular menses– consider when establishing the EDD. An intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD) that is still in place requires removal; it threatens the pregnancy. |

| • Is this pregnancy planned? How do you feel about it? | Even a planned pregnancy represents loss for the woman–perhaps a loss of freedom, compromise of goals, loss of time with other children or partner. The first trimester is known as the ‘trimester of ambivalence’, and encouraging acceptance and expression of these feelings facilitates resolution. |

| • How does the baby’s father feel about the pregnancy? Other family members? | The woman may need assistance in gathering her support group. Inviting significant others to future visits affirms their importance and supports involvement. |

| • Have you experienced any vaginal bleeding? When? How much? What colour? Was it accompanied by any pain? | Vaginal bleeding may indicate threatened abortion, cervicitis or other complications and must be investigated. There may have been an implantation bleed. |

| • Are you experiencing any nausea and/or vomiting? | Nausea and vomiting are symptoms of pregnancy that usually begin between weeks 4 and 5, peak between weeks 8 and 12 and resolve between weeks 14 and 16. |

| • Have you experienced any abdominal pain? When? Where in your abdomen? Accompanied by vaginal bleeding? | The most common causes of abdominal pain in early pregnancy are spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, urinary tract infection (UTI) and round ligament discomfort. Late pregnancy causes are premature labour, placental abruption and HELLP syndrome (see Table 28.2). Also consider other medical and surgical causes for abdominal pain. |

| • Have you experienced any illnesses since being pregnant? Any recent fever(s), unexplained rash or infections? | Helps establish any possible exposures to infectious agents. |

| • Have you had any x-rays? Taken any medications? | Discuss the potential effect of any teratogenic exposure. Refer for expert counselling if necessary. |

| • Have you experienced any visual changes such as the new onset of blurred vision or spots before your eyes? | In the third trimester, this may be a sign of preeclampsia. Evaluate for other signs and symptoms of preeclampsia (see Table 28.2). |

| • Have you experienced any oedema? Where and under what circumstances? | In the third trimester, differentiate the normal weight-dependent oedema of pregnancy from the oedema of preeclampsia. |

| • Have you had any frequency or burning with urination? Any blood in your urine? Do you void in small amounts? Do you have any history of UTIs, pyelonephritis or kidney stones? | Differentiate the normal urinary frequency of the first and third trimesters from UTI, for which pregnant women are at increased risk. Confirm by urinalysis. UTIs increase the rate of preterm labour. |

| • Do you have any vaginal burning or itching? Any foul-smelling or coloured discharge? | Rule out vaginal infection. If symptoms exist, add cultures to the pelvic examination. Discuss partner treatment if necessary. Explain the normal increase in vaginal secretions during pregnancy. |

| • Are you feeling your baby move? | Educate the woman to be aware of fetal movement each day. Tell the woman who has not felt movement to contact the health clinic. |

| • Do you have cats in the home? | Explain toxoplasmosis, a teratogenic disease transmitted through cat faeces. To avoid exposure, another person should empty cat litter at frequent intervals. |

| • Do you plan to breastfeed this baby? | Arrange breastfeeding resources, classes and other support for the woman who is breastfeeding. The support will differ for those who are first-time mothers. |

| • Do you have allergies to medications or foods? If so, what type of reaction? | Alerts health professionals to avoid a prescribing error. |

| • Do you have a history of asthma? | Poor control and frequent exacerbations of asthma during pregnancy may result in maternal hypoxia and decrease in fetal oxygenation. |

| • Have you ever had rubella (German measles)? | This mild childhood disease is highly teratogenic, especially during the first trimester. Instruct the woman who has not had rubella to avoid small children who are ill. Check immunity status in the serum prenatal panel. The nonimmune woman will be offered support during pregnancy and immunisation after delivery. |

| • Have you had chickenpox? | Rarely, varicella causes congenital anomalies. The nonimmune woman should avoid exposure. |

| • Have you had any injury to the back or another weight-bearing part of your body? | The localised and overall weight gain of pregnancy and the joint-softening property of progesterone may cause backache and other joint pain. |

| • Have you been tested for HIV? When? What was the result? Have you ever had a blood transfusion? Used intravenous drugs? Had a sexual partner who had any HIV risk factors? | Address HIV status to promote the health of the woman. An HIV-infected woman needs specialist pregnancy care to reduce the likelihood of transmission to the fetus. Educate the woman who practises high-risk activities. |

| • Do you smoke cigarettes? How many? For how many years? Have you ever tried to quit? Do you drink alcohol? How many times per week? Do you use any street drugs? | Explain the danger of these substances in pregnancy. Smoking increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, prematurity, preterm premature rupture of membranes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, placental abruption and sudden infant death syndrome. Alcohol increases the risk to the fetus of fetal alcohol syndrome (see Table 16.8). Cocaine use during pregnancy is associated with congenital anomalies, a fourfold increased risk for abruptio placentae and the risk of fetal addiction. Narcotic-addicted infants may have developmental delays or behavioural disturbances (Cunningham et al, 2010). Refer to a counselling/support program and periodic toxicology screening. Refer to a smoking cessation program. |

| • Do you take any prescribed, over-the-counter or herbal medications? | Screen all medications (prescribed and over-the-counter) to establish safety during pregnancy. |

| • Do you have a regular exercise program? What do you do? | Regular exercise in pregnancy may reduce risk for pregnancy-induced hypertension. |

| • Does anyone in your family have hypertension? | Increases the risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia. |

| • Does anyone in your family have diabetes? If so, when was the onset and is it diet or medication controlled? | Increases risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. A strong family history might prompt early screening and dietary interventions. |

| • Do you have anxiety, depression or any other mental illness? | Increases risk for postpartum depression (Cunningham et al, 2010). |

| • Does anyone in your family have kidney disease? | Increases risk for renal disease, hypertension and preeclampsia. |

| • Is there a history of multiple pregnancy in your family? | The tendency to ovulate twice in one month is familial, and thus the incidence of multiple pregnancy is increased. |

| • Does anyone in your family, or in the family of the baby’s father, have congenital anomalies? | Some anomalies, such as heart conditions, are familial. Offer genetic counselling if needed. |

| • What is your ethnicity/cultural background? | Establishing ethnicity will indicate any increased risks for known problems such as sickle cell anaemia or thalassaemia. Establishing cultural background allows for culturally sensitive care with mores and customs being respected where possible. |

| • What was your weight before pregnancy? | Baseline needed to evaluate changes. |

| • When did you last see the dentist? Tell me about your oral care routine. | Gums may be puffy and bleed easily during pregnancy, predisposing caries. Poor dental hygiene can lead to preterm delivery, low-birth-weight babies and neonatal death. Encourage careful dental hygiene. Suggest that any dental care be done during the second trimester and to notify the dentist that she is pregnant. |

| • Have you been exposed to tuberculosis (TB) or had a positive PPD or chest x-ray? | Consider TB screening if the woman is at risk. More women with refugee status are seeking pregnancy care and they may be at high risk. |

| • Do you have any cardiovascular disease, such as vascular disease, a heart murmur or disease of a heart valve? | The woman with cardiac disease who becomes pregnant must be monitored carefully for signs of cardiac compromise. Blood volume increases by 40% and the demand on the heart is significantly increased. |

| • Have you ever had anaemia? What kind? When? Was it treated? How? Did it improve? | Pregnancy worsens any preexisting anaemia because iron is used extensively by the fetus. Identify the need for early supplementation. Sickle-cell anaemia may worsen during pregnancy, whereas sickle-cell carriers have more UTIs. Screen the latter periodically for bacteriuria. |

| • Have you had thrombophlebitis, pulmonary embolus (PE) or deep venous thrombosis (DVT)? | Pregnancy itself is a hypercoagulable state because of increases in coagulation factors I, VII, VIII, IX and X. This increases the risk of phlebitis (Cunningham et al, 2010). |

| • Have you had hypertension or kidney disease? | The woman with renal disease or with chronic hypertension is at increased risk for preeclampsia. Know the baseline BP and renal function to evaluate any changes. |

| • Do you have any history of hepatitis B or C? | Confirm this with serum testing. Perinatal transmission usually occurs by the infant being exposed to infected blood and genital secretions during delivery and by cracked and bleeding nipples during feeding. |

| • Do you have a history of thyroid disease? | Uncontrolled hypothyroidism is associated with increased neonatal morbidity resulting from preterm birth and low birth weight. Uncontrolled hypothyroidism is related to delayed mental development in children. |

| • Have you ever had a seizure? | Increased incidence of stillbirths and intrauterine growth restriction is associated with seizure disorders. |

| • Do you have a history of UTIs? | The hormonal changes during pregnancy predispose the woman to UTIs, so a history before pregnancy indicates periodic screening. Pregnancy may also mask the symptoms of UTIs. Further, a serious UTI may cause irritability of the uterus, threatening preterm labour. Educate the woman in measures to prevent UTIs. |

| • Do you feel safe in your relationship or home environment? | Family violence during pregnancy is common. Questioning the safety of the woman is part of prenatal care. Refer to Chapter 5 for a full discussion of screening for family violence and abuse. |

| • Do you have diabetes? Did you have diabetes during a previous pregnancy? | |

| • Do you follow a special diet? | A special diet may put the woman at nutritional risk. Help achieve adequate nutrition within the confines of her diet. |

| • Do you have any food intolerance? | A food intolerance might affect the woman and her fetus’s nutrition, such as lactose intolerance limiting calcium intake. |

| • Do you crave nonfoods such as ice, paint chips, dirt or clay? | Craving for ice and/or dirt is called pica and is associated with anaemia. |

| • What is your occupation? What are the physical demands of your work? Are you exposed to any strong odours, chemicals, radiation or other harmful substances? | Establish any difficulties that the woman may have at work such as possible teratogenic exposures. If there is heavy lifting or long periods of standing then the woman may need to seek alternative arrangements. |

| • Do you consider your food and housing adequate? | If appropriate, refer to state and federal programs to assist with food, housing or other needs. |

| • How do you wear your seat belt when driving? | For maternal and fetal safety, instruct the woman to place the lap belt below the uterus. |

| • Do you have any other questions or concerns? | Encourage the woman to write down questions between visits. |

OBJECTIVE DATA

The extent of the objective part of a health assessment during pregnancy is dependent on the stage of pregnancy. Midwives routinely check the woman’s blood pressure, estimate the fundal height, perform an abdominal examination to determine the fetal position, auscultate the fetal heart rate, check for the development of oedema in the lower limbs and perform a urine test. Other objective tests and examinations are performed according to the presenting symptoms and signs. It is unusual for registered nurses in Australia or New Zealand to perform a comprehensive physical assessment during pregnancy.

Preeclampsia complicates about 8% of pregnancies (Pairman et al, 2010) and is a condition specific to pregnancy that is rarely seen before 20 weeks of gestation except in the presence of a molar (gestational trophoblastic) pregnancy. The aetiology remains unknown, but it is multi-organ disease associated with abnormalities of the coagulation system, disturbed liver function, renal failure, cerebral ischaemia and fetal growth restrictions (Pairman et al, 2010: 805). Predisposing conditions include a family or personal history of preeclampsia, nulliparity, obesity, multifetal gestation, preexisting medical-genetic conditions such as chronic hypertension, renal disease, type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes, factor V Leiden, and thrombophelias such as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (Gabbe et al, 2007). The classic symptoms are elevated BP and proteinuria. Oedema is common in pregnancy; it is the least reliable symptom and is no longer considered a part of the diagnosis of preeclampsia (Gabbe et al, 2007). However, when oedema of the face is of sudden onset and is associated with sudden weight gain, one must consider preeclampsia. Proteinuria is a late development in preeclampsia and is an indicator of the severity of the disease. The BP should be compared with the woman’s first prenatal BP (before 20 weeks gestation). An increase of 15 mmHg diastolic over the baseline or a BP greater than 140 systolic or 90 diastolic is considered hypertension. Hypertension is necessary for the diagnosis of preeclampsia, but preeclampsia may be seen without the oedema or proteinuria. Onset and worsening symptoms may be sudden. Subjective signs may include headaches and visual changes (spots, blurring or flashing lights) caused by cerebral oedema or right upper quadrant/epigastric pain from liver enlargement where it becomes enlarged, necrotic and haemorrhagic. Liver enzyme levels become elevated. Haematocrit usually increases and the platelets drop. Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen elevate. Haemolysis occurs, in part at least, as a result of vasospasm. A serious variant of preeclampsia, the HELLP syndrome, involves Haemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets, and represents an ominous clinical picture. Untreated preeclampsia may progress to eclampsia, which is manifested by generalised tonic-clonic seizures. Eclampsia may develop as late as 10 days postpartum. Before the syndrome becomes clinically manifested, it is affecting the placenta through vasospasm and a series of small infarctions. The placenta’s capacity to deliver oxygen and nutrients may be seriously diminished, and fetal growth may be restricted. |

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

The initial examination for pregnancy may cause some anxiety. The woman may not know for certain whether she is pregnant, and she may be anxious about the findings. Verbally prepare the woman for what will happen during the exam before touching her. It is imperative that you gain informed consent prior to commencing any examination. Always start with the history and then move to the general examination and save the invasive procedure such as pelvic exam for last. By that time the woman will be more comfortable with your gentle, informing manner. Communicate all findings as you go along to demonstrate your respectful affirmation of her control and responsibility in her own health and healthcare and that of her child’s. Ask the woman to empty her bladder before the exam, reserving a specimen for analysis if required. Before the exam, ask the woman to weigh herself on the scales. Provide the woman with a chaperone if desired. Some clinics require an escort or chaperone during examinations. Give the woman a gown and drape. Begin the examination with the woman sitting on the exam table, wearing the gown, her lap covered by a drape. During the breast exam, help her to lie down. She remains recumbent for the abdominal and extremity exam. Use the lithotomy position for the pelvic exam (see Ch 25). Help her to a seated position to check her BP. Recheck after the exam if BP is elevated. |

Equipment needed for pelvic examination as noted in Chapter 25 |

| Procedures and normal findings | Abnormal findings and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| GENERAL SURVEY | |

| Observe the woman’s state of nourishment, and her grooming, posture, mood and affect, which reflect her mental state. Throughout the exam, observe her maturity and ability to attend and learn to plan your teaching of the information she needs to successfully complete a healthy pregnancy. | Poor grooming, a slumped posture and a flat affect may be signs of depression and risk for postpartum depression. Poor grooming may reflect a lack of resources and a need for a social service referral. A lack of attention may indicate some preoccupation with a concern. The woman who has learning difficulties may benefit from written and verbal information, special classes, as well as a support person to accompany her. A flat, unclear affect may indicate depression or the influence of drugs. |

| SKIN | |

| Note the colour of the skin and any scars (particularly those of previous caesarean delivery). Many women have skin changes during pregnancy that may spontaneously resolve after the pregnancy, such as acne or skin tags. Vascular spiders may be present on the upper body. Some women have chloasma, known as the ‘mask of pregnancy’, which is a butterfly-shaped pigmentation of the face. Note the presence of the linea nigra, a hyperpigmented line that begins at the sternal notch and extends down the abdomen through the umbilicus to the pubis (Fig 28.3). Also note striae, or stretch marks, in areas of weight gain, particularly on the abdomen, breasts and thighs. These marks are bright red when they first form, but they will shrink and lighten to a silvery colour (in the lightly pigmented woman) after the pregnancy (see Fig 28.3). | Multiple bruises may suggest physical abuse. Tracks (scars along easily accessed veins) may indicate intravenous drug use. Palmar erythema in the first trimester may indicate hepatitis but thereafter is not clinically significant (Varney, 2004). |

| MOUTH | |

| Mucous membranes should be red and moist. Gum hypertrophy (surface looks smooth and stippling disappears) may occur normally during pregnancy (pregnancy gingivitis). Bleeding gums may be from oestrogen stimulation, which causes increased vascularity and fragility. | |

| NECK | |

| The thyroid may be palpable and feel full but smooth during the normal pregnancy of a euthyroid woman. | Solitary nodules indicate neoplasm; multiple nodules usually indicate inflammation or a multinodular goitre. Significant diffuse enlargement occurs with hyper thyroidism, thyroiditis and hypothyroidism. |

| BREASTS | |

| The breasts are enlarged (Fig 28.4), perhaps with resulting striae and may be very tender. The areolae and nipples enlarge and darken in pigmentation, the nipples become more erect and ‘secondary areolae’ (mottling around the areolae) may develop. The blood vessels of the breast enlarge and may shine blue through a seemingly more translucent than usual chest wall. Montgomery’s tubercles, located around the areola and responsible for skin integrity of the areola, enlarge. Colostrum, a thick yellow fluid, may be expressed from the nipples. | |

The breast tissue feels nodular as the mammary alveoli hypertrophy. Take this opportunity to teach the woman to be breast aware, that is, to identify changes in her breasts. The woman should expect changes in the breast tissue during the pregnancy. (See Ch 27 for instructions for teaching breast awareness.) Recall that some women have an embryological remnant called a supernumerary nipple, which may or may not have breast tissue beneath it. Possibly mistaken previously for a mole, these occur under the arm or in a line directly underneath each nipple on the abdominal wall (see Ch 27). This nipple and breast tissue may show the same changes of pregnancy. Instruct the woman to check these areas as well during breast examination. |

Refer any unusual breast changes for further study. |

| HEART | |

| The pregnant woman often has a functional, soft, blowing, systolic murmur that occurs as a result of increased blood volume. The murmur requires no treatment and will resolve after pregnancy. | Note any other murmur and refer. Valvular disease may necessitate the use of prophylactic antibiotics at delivery. Pregnancy places a large haemodynamic burden on the heart, and the woman with preexisting cardiac disease should be managed closely. |

| LUNGS | |

| The lungs are clear bilaterally to auscultation with no crackles or wheezing. Shortness of breath is common in the third trimester from pressure on the diaphragm from the enlarged uterus. | Women with asthma exacerbations during pregnancy may have expiratory (and possibly inspiratory) wheeze. |

| PERIPHERAL VASCULATURE | |

| The legs may show diffuse, bilateral pitting oedema, particularly if the exam is occurring later in the day when the woman has been on her feet, and in the third trimester. Varicose veins in the legs are common in the third trimester. The Homans’ sign is negative. | Oedema, together with increased BP and proteinuria, is a sign of preeclamp-sia. The pregnant woman is at risk for thrombophlebitis. Carefully evaluate any redness or red, hot, tender swelling to rule out phlebitis. Varicosities increase the risk of thrombophlebitis, and she should not wear restrictive clothing or sit without moving legs for a long period. Varicosities will worsen with the weight and volume of pregnancy, and support hose help to minimise them. |

| NEUROLOGICAL SYSTEM | |

| Using the reflex hammer, check the biceps, patellar and ankle deep tendon reflexes (DTRs). Normally these are 1+ to 2+ and equal bilaterally. | Brisk or greater than 2+ DTRs and clonus may be associated with elevated BP and cerebral oedema in the woman who develops preeclampsia. |

| INSPECT AND PALPATE THE ABDOMEN | |

| Observe the shape and contours of the abdomen to discern signs of fetal position. As the woman lifts her head, you may see the diastasis recti, the separation of the abdominal muscles, which occurs during pregnancy, with the muscles returning together after pregnancy with abdominal exercise. When palpating, note the abdominal muscle tone, which grows more relaxed with each subsequent pregnancy. Note any tenderness. | The uterus is usually nontender. |

| The fundus should be palpable abdominally from 12 weeks gestation on. Use the side of your hand and begin palpating centrally on the abdomen higher than you expect the uterus to be. Palpate down until you feel the fundus (the top of the uterus). This is called fundal palpation and gives you an estimate of the weeks of gestation. Then stand at the woman’s right side facing her head (Fig 28.5). Place the palm of your right hand on the curve of the uterus in the left lower quadrant and your left palm on the curve of the uterus in the right lower quadrant. Moving from hand to hand, allowing the curve of the uterus to guide you, ‘walk’ your hands to where they meet centrally at the fundus. This is called lateral palpation and allows you to identify the position of the fetal back and head. | |

| Note the fundal location by landmarks and fingerbreadths, as described in Figure 28.1. Note that individual women’s variations in location of landmarks and examiner’s variations in fingerwidth makes this measurement inexact. The fundal height measurement should be done with the woman lying flat with her head supported on a single pillow. Measure from the highest point of the fundus to the top of the symphysis pubis. Measure with tape scale downwards (Fig 28.6). After 20 weeks, the number of centimetres should approximate the number of weeks of gestation. | Measurement should be recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm. Compare to the previous measurement. |

| Beginning at 20 weeks, you may feel fetal movement and the fetal head can be ballotted. A gentle, palpation with the fingertips can locate a head that is not only hard when you push it away, but is hard as it bobs or bounces back against your fingers. | |

| If you suspect the woman to be in labour, palpate for uterine contractions. Palpate the uterus over its entire surface to familiarise yourself with its ‘indent-ability’. Then rest your hand lightly on the uterus with fingers opened. When the uterus contracts, it rises and pulls together, drawing your fingers closer together. | |

| During the contraction, notice that the uterus is less ‘indentable’. When the uterus relaxes, your fingers relax open again. In this way, contractions can be monitored for frequency (from the beginning of one contraction to the beginning of the next), length, and quality. Note that a mild contraction feels like the firmness of the tip of your nose; a moderate contraction feels like your chin; and a hard contraction feels like a forehead. (Make allowance for the amount of soft tissue between your fingers and the uterus.) | An abnormal uterine contraction is dystonic in nature; the contraction begins in the lower uterine segment and may delay cervical dilation. |

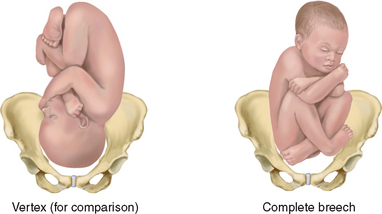

| Leopold’s manoeuvres | |

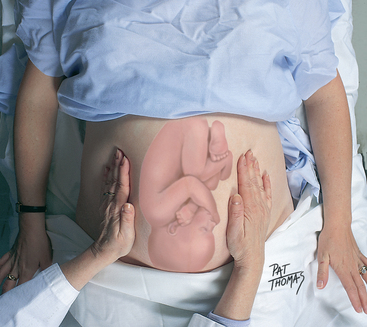

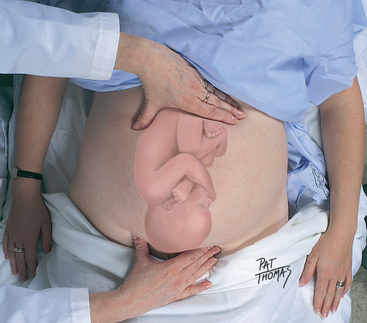

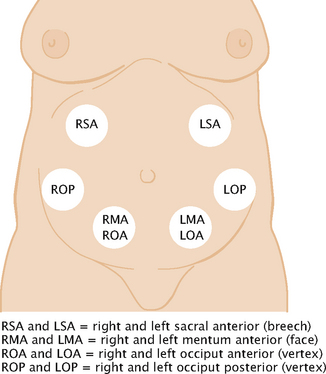

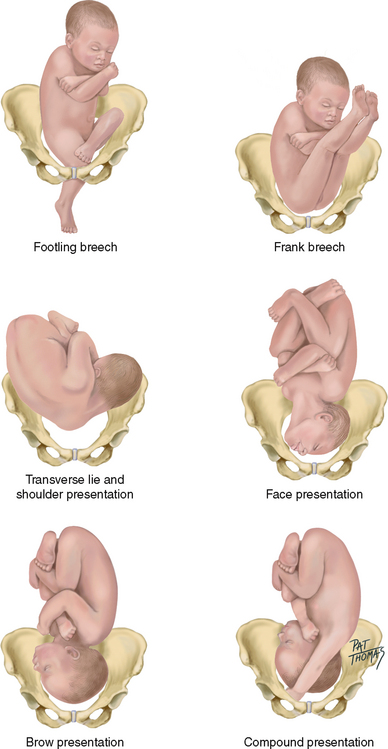

| In the third trimester, perform Leopold’s manoeuvres to determine fetal lie, presentation, attitude, position, variety and engagement. Fetal lie is the orientation of the fetal spine to the maternal spine and may be longitudinal, transverse or oblique. Presentation describes the part of the fetus that is entering the pelvis first. Attitude, the position of fetal parts in relation to each other, may be flexed, military (straight) or extended. Position designates the location of a fetal part to the right or left of the maternal pelvis. Variety is the location of the fetal back to the anterior, lateral or posterior part of the maternal pelvis. Engagement occurs when the widest diameter of the presenting part has descended into the pelvic inlet—specifically, to the imagined plane at the level of the ischial spines. | |

| Leopold’s first manoeuvre is performed by facing the woman’s head and placing your fingertips around the top of the fundus (Fig 28.7). Note its size, consistency and shape. Imagine what fetal part is in the fundus. The breech (bottom) feels large and firm. Moving it between the thumb and fingers of the hand, because it is attached to the fetus at the waist, results in moving it slowly and with difficulty. In contrast, the fetal head feels large, round and hard. When it is ballotted, it feels hard as you push it away and hard again as it bobs back against your fingers in an ‘answer’. Note that the ‘bobbing’ or ‘ballotting’ sensation of the movement occurs because the head is attached at the neck and moves easily. If there is no part in the fundus, the fetus is in the transverse lie. | |

| For Leopold’s second manoeuvre, move your hands to the sides of the uterus (Fig 28.8). Note whether small parts or a long, firm surface are palpable on the woman’s left or right side. The long, firm surface is the back. Note whether the back is anterior, lateral or out of reach (posterior). The small parts, or limbs, indicate a posterior position when they are palpable all over the abdomen. | |

| Leopold’s third manoeuvre, also called Pawlik’s manoeuvre, requires the woman to bend her knees up slightly (Fig 28.9). Grasp the lower abdomen just above the symphysis pubis between the thumb and fingers of one hand, as you did at the fundus during the first manoeuvre, to determine what part of the fetus is there. If the presenting part is beginning to engage, it will feel ‘fixed’. With this manoeuvre alone, it may be difficult to differentiate the shoulder from the vertex. | |

| The fourth manoeuvre assists in determining engagement and, in the vertex presentation, to differentiate shoulder from vertex (Fig 28.10). The woman’s knees are still bent. Facing her feet, place your palms, with fingers pointing towards the feet, on either side of the lower abdomen. Pressing your fingers firmly, move slowly down towards the pelvic inlet. If your fingers meet, the presenting part is not engaged. If your fingers diverge at the pelvic rim meeting a hard prominence on one side, this prominence is the occiput. This indicates the vertex is presenting with a deflexed head (the face presenting). If your fingers meet hard prominences on both sides, the vertex is engaged in either a military or a flexed position. If your fingers come to the pelvic brim diverged but with no prominences palpable, the vertex is ‘dipping’ into the pelvis, or is engaged. In this case, the firm object felt above the symphysis pubis in the third manoeuvre is the shoulder. | |

| See Figure 28.11 for various fetal positions and where to auscultate the fetal heart beats for each. At the end of pregnancy, 96% of fetal presentations are vertex, 3.5% are breech, 0.3% are face and 0.4% are shoulder (Cunningham et al, 2010). | |

| AUSCULTATE THE FETAL HEART BEAT | |

| Fetal heart beats are a positive sign of pregnancy. They can be heard by fetal Doppler from 8 to 10 weeks gestation. The fetal heart rate is best auscultated over the shoulder of the fetus. After identifying the position of the fetus (see Fig 28.11), use the heart sounds to confirm your findings. Count the fetal heart beats for 15 seconds and multiply by four to obtain the rate (Fig 28.12). The normal rate is between 110 and 160 beats per minute. Spontaneous accelerations of fetal heart sounds indicate fetal wellbeing. | If no fetal heart beat is heard, verify fetal cardiac activity with ultrasound. It is important not to alarm the mother and her partner. The inability to hear the fetal heart rate may be due to the position of the fetus or other factors. Further investigate any decelerations of fetal heart rate with an ultrasound. |

| Differentiate the fetal heart sounds from the slower rate of the maternal pulse and the uterine souffle (the soft, swishing sound of the placenta receiving the pulse of maternal arterial blood) by palpating the mother’s pulse while you listen. Also, distinguish fetal heart sounds from the funic souffle (blood rushing through the umbilical arteries at the same rate as the fetal heart beats). The fetal heart sounds are a double sound, like the tick-tock of a watch under a pillow, whereas the funic souffle is a sharp, whistling sound that is heard only 15% of the time (Cunningham et al, 2010). | All the abdominal findings are of interest to the woman. Share them with her. Often she will want to listen to the fetal heart beat with her significant others. For the hearing-impaired pregnant woman, place her hand on the fetal monitor to feel the fetal heart vibrating. |

| PELVIC EXAMINATION | |

| Genitalia | |

| Use the procedure for the pelvic examination described in Chapter 25. Note the following characteristics. The enlargement of the labia minora is common in multiparous women. Labial varicosities may be present. The perineum may be scarred from a previous episiotomy or tear. Note the presence of any haemorrhoids of the rectum. | |

| Bimanual examination | |

| As described in Chapter 25, palpate the uterus between your internal and external hands. Note its position. The pregnant uterus may be rotated towards the right side as it rises out of the pelvis because of the presence of the descending colon on the left. This is called dextrorotation. Irregular enlargement of the uterus may be noted at 8 to 10 weeks and occurs when implantation occurs close to a cornual area of the uterus. This is called Piskacek’s sign. Also you may note Hegar’s sign, when the enlarged uterus bends forward on its softened isthmus between the 4th and 6th weeks of pregnancy. | |

| Note the size and consistency of the uterus. The 6-week gestation uterus may seem only slightly enlarged and softened. The 8-week gestation uterus is approximately the size of an avocado, approximately 7 to 8 cm across the fundus. The 10-week gestation uterus is about the size of a grapefruit and may reach to the pelvic brim, but it is narrow and does not fill the pelvis from side to side; the 12-week gestation uterus will fill the pelvis. After 12 weeks, the uterus is sized from the abdomen. The multigravid uterus may be larger initially, and early sizing of this uterus may be less reliable for dating. | |

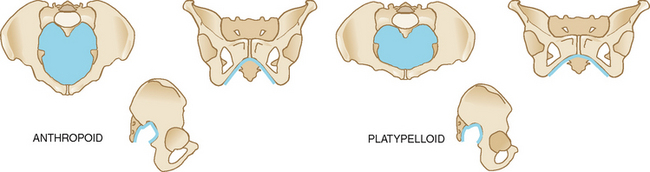

| Softening of the cervix is called Goodell’s sign. When examining the cervix, note its position (anterior, midposition or posterior), degree of effacement (or thinning, expressed in percentages assuming a ≥2-cm long cervix initially), dilation (opening, expressed in centimetres), consistency (soft or firm) and the station of the presenting part (centimetres above or below the ischial plane) (Fig 28.13). | A shortened cervix is <2 cm. |

| To determine tone, ask the woman to squeeze your fingers as they rest in the vagina. Take this opportunity to teach Kegel exercise, the squeezing of the vagina, which the woman can do to prepare for and to recover from birth. For a full description of assessment of pelvic floor muscle strength see Chapter 25. | If the woman has poor pelvic floor muscle tone and/or is experiencing urinary incontinence, suggest that she is referred to a continence nurse advisor or continence physiotherapist for a pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation program. |

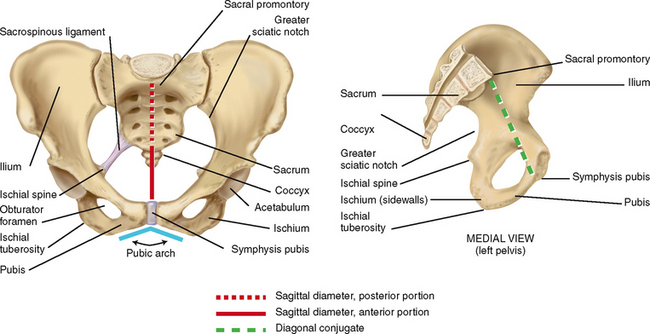

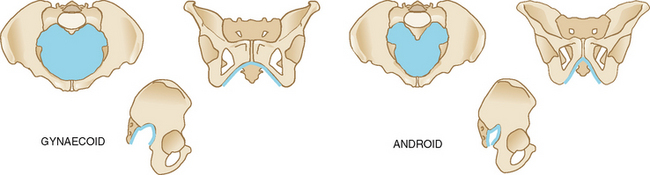

| Bony pelvis assessment | |

| Assess the bones of the pelvis for shape and size. The dimensions may indicate the favourableness of the bony structure for vaginal delivery. However, the relaxation of the pelvic joints, the widening of the pelvis in the squatting position and the capacity of the fetal head to mould to the shape of the pelvis may enable a vaginal birth despite seemingly unfavourable measurements. | |

| To aid in visualising the pelvis, imagine three planes: the pelvic inlet (from the sacral promontory to the upper edge of the pubis), the midpelvis and the pelvic outlet (from the coccyx to the lower edge of the pubis) (Fig 28.14). Assessment of each of these pelvic planes, as described in the following techniques, allows you to estimate the adequacy of the pelvis for vaginal delivery. | |

| There are four general types of pelvis: gynaecoid, anthropoid, android and platypelloid (Table 29.1). You may postpone examination of the bony pelvis until the third trimester when the vagina is more distensible. With your two fingers still in the vagina, note the shape and width of the pubic arch (a 90-degree arch, or 2 fingerbreadths, is desirable). If you are right-handed, move your hand to the woman’s right pelvis. If you are left-handed, move it to the left side of the woman’s pelvis. Assess the inclination and curve of the side walls and the prominence of the ischial spine (refer to Fig 28.14 for location of these landmarks). Move your fingers back and forth between the spines to get an impression of the transverse diameter—10 cm is desirable. Sweep your fingers down the sacrum, noting its shape and inclination (hollow, J-shaped or straight). Assess the coccyx for prominence and mobility. From the sacrum, locate the sacrospinous ligament. Assess the length of the ligament—2½ to 3 fingerbreadths is adequate. Assess the shape and width of the sacrospinous notch. Shift to the other side of the pelvis and assess it for similarity to the first. | |

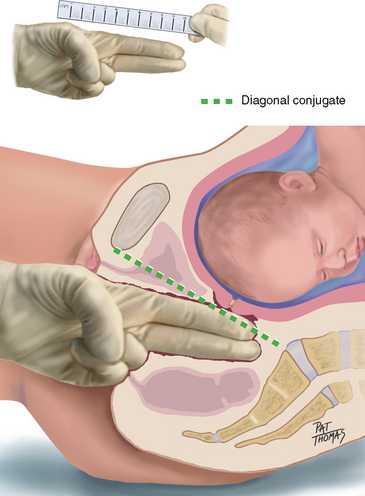

| The pelvic inlet cannot be reached by clinical examination, but you can estimate it by the measure of the diagonal conjugate, which indicates the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic inlet. Having measured the length of the second and third fingers of your examining hand, with your fingers still in the vagina, point these fingers towards the sacral promontory (Fig 28.15). If you cannot reach the promontory, note the measurement as being greater than the centimetres of length of your examining fingers. A measurement of 11.5 to 12.0 cm is desirable. | |

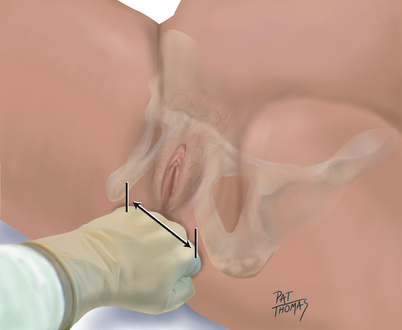

| Remove your fingers from the vagina. Having previously measured the width of your own hand across the knuckles, form your hand into a closed fist and place it across the perineum between the ischial tuberosities. Estimate this diameter, which is the bi-ischial diameter (also known as the intertubous diameter and the transverse diameter of the pelvic outlet). A measurement greater than 8 cm is generally adequate (Fig 28.16). | |

| When describing pelvimetry, note all the above measurements and state the pelvic type. The pelvis may be described as being ‘proven’ to the number of kilograms of the largest vaginally born infant. | |

| Blood pressure | |

| After the exam, take the blood pressure when the woman is the most relaxed, in the upright position. Recheck an elevated pressure. | Chronic hypertension: a documented history of high BP before pregnancy or a persistent elevation of at least 140/90 mmHg on two occasions more than 24 hours apart before the 20th week of gestation (Gabbe et al, 2007). |

| ROUTINE LABORATORY AND RADIOLOGICAL IMAGING STUDIES | |

| At the onset of pregnancy, order routine blood screening which includes a complete blood picture, haemoglobin, blood group, antibodies, rubella titre, syphilis, hepatitis B and C and HIV serology. Some providers screen for herpes simplex virus I and II. Sickle cell screening may be indicated. For some populations, a PPD/TINE test may be indicated to rule out active or exposure to tuberculosis. Maternal serum screening for haemoglobinopathies, vitamin D level and cytomegalovirus may also be indicated. Obtain Pap smear at the initial visit if the woman has not had a pap smear for more than 2 years. | |

| Collect a clean-catch urinalysis at the initial prenatal visit to rule out any infection. | Any abnormalities detected on dipstick urine testing should be referred to a medical practitioner for further investigation. |

| The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2009) recommend that every woman should have a prenatal ultrasound at 18–20 weeks of gestation to determine fetal morphology, placental location and confirm gestation. | The ultrasound may also show fetal gender; however, this is not 100% accurate. |

TABLE 28.1 The four pelvic types

|

| The gynaecoid pelvis | The android pelvis |

|---|---|

| Inlet round or oval. | Inlet heart-shaped. |

| Posterior sagittal diameter of inlet only slightly less than anterior sagittal diameter. | Posterior sagittal diameter of inlet less than the anterior sagittal diameter. |

| Pubic arch wide (90 degrees or more). | Pubic arch narrow (less than 90 degrees). |

| Spines are not prominent, allowing a transverse diameter at spines 10 cm or more. | Spines are prominent, decreasing transverse diameter at spines. |

| Sacrosciatic notch round and wide. | Sacrosciatic notch is narrow and highly arched. |

| Straight side walls. | Side walls converge. |

| Posterior pelvis is round and wide. | Posterior sagittal diameter decreases from inlet to outlet as sacrum inclines forwards. |

| Sacrum is parallel with the symphysis pubis; hollow and concave. | |

| Favours vaginal delivery. | Poor prognosis for vaginal delivery. |

| Seen in 50% of all women. | Seen in 20% of all women. |

|

| The anthropoid pelvis | The platypelloid pelvis |

|---|---|

| Inlet oval in shape. | Inlet shaped like a flattened gynaecoid pelvis. |

| Pubic arch may be somewhat narrow. | Pubic arch wide. |

| Spines usually prominent but not encroaching because of the spaciousness of the posterior segment. | Spines usually prominent but not encroaching because of the already wide interspinous diameter. |

| Sacrosciatic notch average height but wide (about 4 fingerbreadths). | Sacrosciatic notch wide and flat. |

| Side walls somewhat convergent. | Side walls slightly convergent. |

| Sacrum posteriorly inclined, with posterior sagittal diameters long throughout the pelvis. | Sacrum inclined posteriorly and hollow, making a short and shallow pelvis. |

| Seen in 25% of all women. | Occurs in 5% of all women. |

| If pelvis somewhat large, adequate for vaginal delivery because posterior pelvis is generous. | Not conducive to vaginal delivery. |

Data from Varney H: Varney’s midwifery, 3rd edn. Sudbury, MA, 1997, Jones & Bartlett.

Figure 28.13 A, Cervix before labour. B, Cervix begins to efface and dilate. C, Station height of presenting part in relation to ischial spines.

Summary Checklist The pregnant female

1. Collect subjective date, i.e. historical information.

2. Determine EDD and current number of weeks of gestation.

3. Instruct the woman to undress and empty her bladder. Undertake analysis of urine if it is policy.

5. Perform a physical examination, starting with general survey.

6. Inspect skin for colour, pigment changes, scars and altered surface characteristics.

7. Check oral mucous membranes.

9. Inspect breast and note changes. Palpate for abnormalities.

10. Auscultate breath sounds, heart sounds, heart rate and any murmurs.

11. Check lower extremities for oedema, varicosities and reflexes.

12. The abdomen: measure fundal height, perform Leopold’s manoeuvres, auscultate fetal heart sounds.

13. The pelvic exam: note signs of pregnancy, the condition of the cervix and the size and position of the uterus.

DOCUMENTATION AND CRITICAL THINKING

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY

Subjective

Helen T, a 27-year-old woman, gravida 2/para 1, who presents with her husband and daughter for her first prenatal visit. She works full-time as a financial planner. Last normal menstrual period (LNMP) was 4 April of this year (certain of date), with an expected date of delivery (EDD) of 11 January of next year, making her 10 weeks gestation today. Her obstetric history includes a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery (NSVD) 3 years ago of a viable 3.2 kg female infant after a 12-hour labour. She sustained a small perineal tear that did not require suturing. No complications of pregnancy, delivery or the postpartum. She breastfed this daughter, Anna, for 1 year. Present pregnancy was planned, and Helen and her husband are pleased. Helen is experiencing breast tenderness, and nausea on occasion, which resolves with dry biscuits and ginger tea. No past medical or surgical conditions are present. She has no known allergies. Family history is significant only for diet-controlled adult-onset diabetes in two maternal aunts.

Objective

General: Appears well nourished and is carefully groomed.

Skin: Light tan in colour, surface smooth with no lesions.

Mouth: Good dentition and oral hygiene. Oral mucosa pink, no gum hypertrophy.

Chest: Expansion equal, respirations effortless. Lung sounds clear bilaterally with no adventitious sounds.

Heart: Rate 76 bpm, regular rhythm, S1 and S2 are normal, not accentuated or diminished, with soft, blowing systolic murmur Gr ii/vi at 2nd left interspace.

Breasts: Tender, without masses, with supple, everted nipples. Breast awareness discussed.

Abdomen: No masses, bowel sounds present. Uterus nonpalpable.

Extremities: No varicosities, redness or oedema. BP 110/68 in semi-Fowler’s.

Pelvic: Bartholin’s, urethra and Skene’s glands negative for discharge. Vagina: pink with white, creamy, nonodourous discharge. Cervix: pink, closed, multiparous, 2 cm long, firm.

Uterus: 10-week size, consistent with dates, nontender. Fetal heart sounds heard with Doppler, rate 140s.

Pelvis: Pubic arch wide; side walls straight, spines blunt, interspinous diameter >10 cm. Sacrum hollow; coccyx mobile. Sacrospinous ligament 3 fingerbreadths (FBs) wide. Diagonal conjugate >12 cm, bituberous diameter >8 cm.

ABNORMAL FINDINGS FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE

TABLE 28.3 Fetal size inconsistent with dates

| SIZE SMALL FOR DATES | Fundal height measures smaller than expected for gestation or not increasing from previous measurements. |

| Inaccuracy of dates | Conception may have occurred later than originally thought. Reconsider the woman’s menstrual history, sexual history, contraceptive use, early pregnancy testing, early sizing of the uterus, ultrasound results, timing of pregnancy symptoms, including the date of quickening, and the fundal height measurements. If, after this review, the EDD is correct, then further investigation is required. |

| Premature labour | When premature labour (before 37 weeks of gestation) engages the presenting part of the fetus into the pelvis for delivery, the fundus may shorten. In Australia preterm birth occurs in 7.4% of all mothers with slightly higher rates in the Northern Territory (9.5%) (Laws, Li, Sullivan, 2010). In New Zealand the preterm birth rate is 12% (New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2010). Risk indicators for preterm birth include abdominal surgery during the current pregnancy, age of <18 years or >35 years, chronic urinary tract infections, conisation of the cervix, hydramnios, hypertensive disorders, low socioeconomic status, low prepregnancy weight, multiple gestation, woman was herself a preterm infant, poor nutrition, previous preterm delivery, cigarette smoking, strenuous work, substance/drug abuse (especially cocaine and alcohol), incompetent cervix, uterine anomalies and uterine infections (Swenson, 2001). |

| Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) or fetal growth restriction | IUGR, a syndrome where the neonate fails to meet its growth potential, is associated with an increase in fetal and neonatal mortality and morbidity. Its origin may be fetoplacental, as with chromosomal abnormalities, genetic syndromes, congenital malformations, infectious diseases and placental pathology. Or its origin may be maternal, as with decreased uteroplacental blood flow as seen with hypertensive disorders, poor maternal weight gain, poor maternal nutrition and a previous pregnancy with an IUGR infant. Other factors include infectious diseases (rubella, cytomegalovirus); multiple gestation; and environmental toxins such as smoking, maternal drug ingestion and alcohol. |

| Fetal position | Fetal position varies until about 34 weeks, when the vertex should settle into the pelvis and remain there. The fetus occupying a transverse lie, or shoulder presentation, results in the maternal abdomen’s widening from side to side and the fundal height’s diminishing. Fetal malposition may occur with lax maternal abdominal musculature (simply not holding the baby in close), an abnormality in the fetus (e.g. the enlarged head of the hydrocephalic infant), placenta praevia (the placenta being implanted over the cervix, blocking fetal descent) or a restricted maternal pelvis. |

| SIZE LARGE FOR DATES | Fundal height measures larger than expected for dates. |

| Inaccuracy of dates | Review the same findings as listed above. |

| Hydatidiform mole | Also termed gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, it is a result of abnormal proliferation of trophoblastic tissue associated with pregnancy. In 50% of cases, uterine size is excessive; in these cases the gestational age and uterine size do not coincide. |

| Multiple fetuses | The frequency of multiple fetuses increases with advanced maternal age and is enhanced by the increasing use of fertility drugs. The uterus enlarges where the fundal height may be beyond the calculated/expected gestational age. Ultrasound examination confirms the diagnosis. |

| Polyhydramnios | An amniotic fluid volume is a maximum volume pocket above 8.0 cm or an amniotic fluid index (AFI) above the 95th percentile or ≥20 cm. The cause is usually idiopathic but may be due to fetal anomalies, insulin-dependent diabetes, GDM and multiple fetuses (Creasy and Resnick, 2004). |

| Oligohydramnios | Oligohydramnios is a reduction in amniotic fluid volume or an AFI less than 5.0 cm at term. An acceptable AFI is between 10 and 20 (Gabbe et al, 2007). |

| Leiomyoma (myoma or ‘fibroids’) | These are preexisting benign tumours of the uterine wall, which are then stimulated to enlarge by the oestrogen levels of pregnancy. Myomata may be located anywhere in the uterine wall (see Table 25.6). When they grow in the outer uterine wall, the myometrium, they may affect the clinician’s judgment of where the fundus of the uterus should be measured. A myoma may grow just underneath the endometrial surface into the uterine cavity, displacing the fetus or preventing its descent into the pelvis. |

Fetal macrosomia |