Chapter 3 Health history and physical examination

1. Explain the purpose, components and techniques related to a patient’s health history and physical examination.

2. Obtain a nursing history using a functional health pattern format.

3. Describe the appropriate use and techniques of inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation.

4. Differentiate between a screening physical examination and a focused examination in terms of indications, purpose and components.

5. Record a nursing history and physical examination using a standard format.

Obtaining a patient’s health history and performing a physical examination are activities completed by the nurse during the assessment phase of the nursing process. Information obtained during this phase contributes to a database that identifies the patient’s current and past health state and provides a baseline against which future changes can be evaluated. The purpose of the nursing assessment is to enable the nurse to make a judgement about the patient’s health state.1 Although assessment is identified as the first step of the nursing process, it is performed continuously throughout the nursing process to validate nursing diagnoses, evaluate the patient’s response to nursing interventions and determine the extent to which patient outcomes and goals have been met.

Data collection

Collection of data about the patient is not solely the nurse’s responsibility. The database contains all the health information about a patient. It includes the nursing history and physical examination, the doctor’s history and physical examination, results of laboratory and diagnostic tests, and information contributed by other healthcare professionals. Numerous approaches and formats exist for gathering information about the patient in various healthcare settings. The purpose for which the information is to be used determines the methods of data collection. The nurse and doctor both perform a patient history and physical examination but they use different formats and analyse the data differently because of each discipline’s focus.

MEDICAL FOCUS

A medical history is a standard format designed to collect data to be used primarily by the doctor to determine risk of disease and diagnose a medical condition (see Box 3-1). The medical history is usually collected by a member of the medical team (doctor, resident medical officer or medical student). The doctor’s physical examination and laboratory and diagnostic tests assist in establishing a medical diagnosis and evaluating specific medical therapy. The information collected and reported by the doctor is also used by nurses and other healthcare providers but within the focus of their care. For example, the abnormal results of a neurological examination by a doctor may assist in the diagnosis of a brain lesion but the nurse may use those same results to identify a nursing diagnosis of a risk of falls. The physiotherapist may also use the results to plan therapy involving exercise, splints or ambulatory aids.

NURSING FOCUS

The focus of nursing care is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses to actual or potential health problems. The information obtained from the nursing history and physical examination is used to determine what responses the patient is exhibiting or could potentially exhibit as a result of a health problem. The nurse is interested in the functional capabilities of the patient. In the patient with a medical diagnosis of congestive heart failure, for example, the patient’s response may be anxiety or a lack of energy to carry out normal daily activities. These are human responses to heart failure that can be diagnosed and treated by nurses. During the nursing history interview and physical examination the nurse obtains the necessary data to support the identification of nursing diagnoses (see Fig 3-1).

TYPES OF DATA

The database includes both subjective and objective data. Subjective data are collected by interviewing the patient during the nursing history. This includes information that can only be described or verified by the patient. It is what the patient tells the nurse about himself or herself either as spontaneously offered information or in response to direct questioning. Subjective data are also referred to as symptoms. Knowledgeable others, such as family members and carers, may contribute subjective data about the patient.

Objective data are data that can be observed and measured. These types of data are obtained using inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation during the physical examination. In addition, objective data are provided by other healthcare providers and diagnostic testing. Objective data are also called signs, such as vital signs that can be measured (e.g. temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation and central venous pressure).

Although subjective data are usually obtained by interview and objective data are obtained by physical examination, it is common for the patient to provide subjective data while the nurse is performing the physical examination, and it is also common for the nurse to observe objective signs while interviewing the patient during the history.

APPROACHES TO DATA COLLECTION

Numerous approaches and formats are used to gather information about the patient. The amount and organisation of data collected depend on the needs of the patient, the healthcare setting and the clinical situation. A comprehensive assessment is obtained at the onset of care in a primary care setting and upon admission to a hospital or a long-term care facility. It includes information related to the patient’s health status, health maintenance behaviours, individual coping patterns, support systems, current developmental tasks, cultural assessment and any risk factors or lifestyle changes. For the ill patient, the assessment also includes a description of the health problem, the patient’s perception of the illness, functional ability or patterns of living, and response to the health problem.1

Shorter, more focused assessments are more commonly performed. An episodic or problem-centred assessment is performed when a problem of limited scope is identified. It is used in all healthcare settings and includes a history and examination related to one problem, such as an upper respiratory tract infection, a minor injury or specific abnormal findings in a hospitalised patient. A follow-up assessment is an assessment to evaluate the status of previously identified problems. In an emergency situation, an emergency assessment may be obtained by rapid specific questioning of the patient while performing assessment and maintenance of vital functions.

INTERVIEWING CONSIDERATIONS

The purpose of the patient interview is to obtain subjective data about the patient’s past and present health state. Collection of data assists the nurse and the patient in identifying health problems, as well as patient strengths and resources. The nurse can use the data to identify areas where the patient may be unable to meet personal needs and therefore requires nursing assistance. The patient perceives this encounter as an indication of how the healthcare system will provide assistance.

Effective communication is a key factor in the interview process. Creating a climate of trust and respect is critical to establishing a therapeutic relationship.2 The nurse must communicate acceptance of the patient as an individual by using an open, responsive, non-judgemental approach. Individuals communicate not only through language but also in their manner of dress, gestures and body language. Modes of communication are learned through one’s culture, influencing not only the words, gestures and posture one uses, but also the nature of information that is shared with others (see Ch 2). In addition to understanding the principles of effective communication, each nurse must develop a personal style of relating to patients. Although no single style fits all people, wording specific questions in certain ways will increase the probability of eliciting the needed information. Ease in asking questions, particularly those related to sensitive areas such as sexual functioning and economic status, will come with experience.

The amount of time needed to complete a nursing history may vary with the format used and the experience of the nurse. It may be completed in one or several sessions, depending on the setting and the patient. In the case of an older patient with a low energy level, several short sessions may need to be scheduled. Allowing time for the patient to volunteer information about particular areas of concern enables the nurse to work with the patient to identify existing and potential health problems. When a patient is unable to provide the necessary data (e.g. is unconscious or aphasic), the nurse should ask the person who has assumed responsibility for the patient’s welfare to provide as much information as possible.

Before beginning the nursing history, the nurse should explain to the patient that the purpose of a detailed history is to collect information that will provide a health profile for comprehensive individualised care. It is very important to explain this to all patients regardless of their cultural or socioeconomic background, as most people are not generally used to sharing personal intimate details about themselves and need to know why they are being asked such personal information. The nurse should also assure the patient that all information will be kept confidential. This detailed information is collected during entry into the healthcare system and, subsequently, only updates are needed.

To obtain factual, easily categorised information from patients a direct interview technique can be used. This technique uses questions that are referred to as closed questions because they require brief and specific responses: for example, ‘Have you had surgery before?’ When asking personal and social questions, it is more appropriate to use open questions. Open questions encourage the patient to give their opinions and feelings and to think and reflect about their health concerns.3 When asking questions about sensitive issues such as sexuality, spirituality and alcohol or drug use, the nurse can communicate acceptance or normalcy of behaviours by prefacing questions with phrases such as ‘many people’ or ‘frequently’: for example, ‘Many people with your health condition have sexual concerns; do you have any you would like to discuss?’ This shows the patient that a particular situation may not be unique to them. Another method of putting the patient at ease is to word the question so that an affirmative answer appears expected. An example of this technique is to ask, ‘What do you like to drink at a party?’ or ‘How often do you drink alcohol?’ instead of, ‘Do you drink alcohol?’ Appropriate questioning and communication are fundamental to developing an effective nurse–patient relationship and essential to assist patients in their transitions through health and illness.4

The nurse must judge the reliability of the patient as an historian. Older adults may give a false impression about their mental status because of a prolonged response time or visual and hearing impairment. The complexity and long duration of health problems may also make it difficult for older adults to be accurate, orderly historians.

It is important that the nurse determine the patient’s priority concerns and expectations early in the interview. Often there is a lack of congruency between the priorities of the patient and those of the nurse. For example, the nurse’s priority may be to get a consent form signed, whereas the patient is interested only in getting relief from pain. Until the patient’s priority need is met, the nurse will probably be unsuccessful in meeting the nursing goal.

The amount of information that should be collected on initial contact with the patient is a nursing judgement based on the patient, the problem and the setting. Interviews with older patients, patients with long-term chronic disease and emergency department admissions are examples of situations in which the nurse must use this judgement. The nurse may choose to ask only those questions that are pertinent to a specific problem and to defer the complete history interview until a more appropriate time.

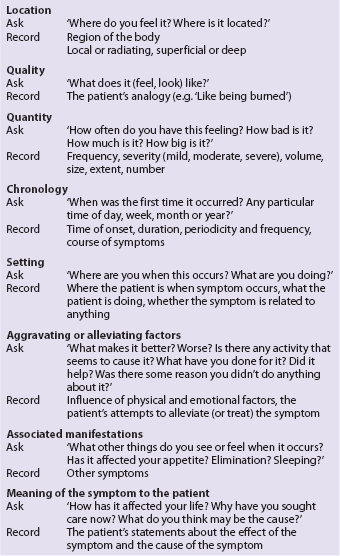

SYMPTOM INVESTIGATION

At any time during assessment the patient may relate a symptom such as pain, fatigue or weakness. Because symptoms are directly experienced by the patient and not observable to the nurse, symptoms must be investigated. A useful way to explore a symptom identified by a patient is to begin with the location of the symptom, then to ask follow-up questions and accurately record the information obtained. Box 3-2 lists eight areas that should be investigated if a symptom is present. The information that is obtained may help determine the cause of the symptom. For example, if a patient states that she has ‘pain in her leg at times’, the nurse might obtain and record the following information:

Has right midcalf pain (location), described as ‘like being stabbed with a knife’ (quality). Pain is so severe that it is not possible for the patient to continue walking (quantity). Onset is abrupt, lasting for 1–2 minutes; it occurs once or twice daily, and it last occurred on 5/5/11 (chronology). Generally occurs at work when climbing stairs after lunch but last occurred when going for a routine morning walk (setting). Pain is alleviated by rest for 2–3 minutes. The patient has been salting her food ‘more heavily’ than she used to, but ‘it doesn’t help’ (alleviating factor). Leg pain is at times accompanied by chest pain that causes some nausea (associated manifestations). The patient has not altered her lifestyle because of the intermittent pain. She thinks it is caused by ‘muscle cramps from lack of salt’ (personal meaning).

Nursing history: subjective data

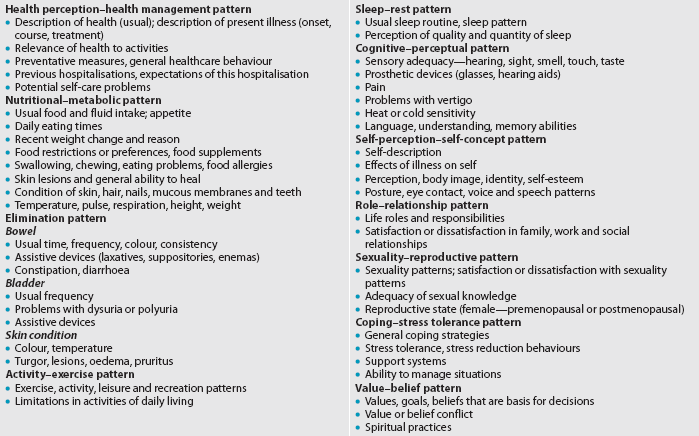

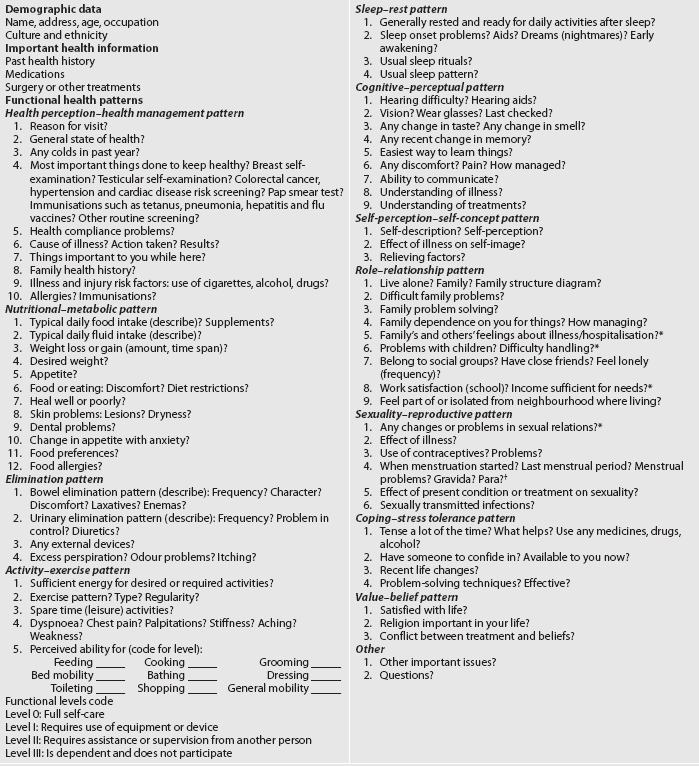

The format used in this text for obtaining a nursing history includes the initial collection of important health information followed by assessment of the patient’s functional health patterns (see Table 3-1). Gordon’s functional health patterns is a method developed by a nurse, Marjory Gordon, as a guide for establishing a comprehensive nursing assessment database.5 The format is designed to promote systematic data collection to determine the presence of problems amenable to nursing diagnosis and treatment. Analysis of the data collected with assessment of each functional health pattern facilitates the nursing diagnosis process. There are many assessment frameworks that can be used and most are based on an underlying theoretical perspective relevant to health and/or nursing. Since Gordon’s functional health patterns provides a clear and systematic basis for data collection, this method is used in this book as an example for nurses developing assessment and care planning skills.

TABLE 3-1 Nursing history: functional health pattern format

Source: Modified from Gordon M. Manual of nursing diagnosis. 12th edn. Boston: Jones & Bartlett; 2010.

IMPORTANT HEALTH INFORMATION

Important health information provides an overview of past and present medical conditions and treatments. Past health history, medications and surgery or other treatments are included in this part of the history.

Past health history

The past health history provides information about the patient’s prior state of health. The patient is specifically asked about major childhood and adult illnesses, injuries, hospitalisations, operations, therapeutic regimens, travel, habits and use of supportive devices. Specific questioning is more effective than simply asking whether the patient has had any illness or health problems in the past.

Medications

It is important to ask specific details related to past or present medications. This includes the use of prescription drugs (including contraceptives), over-the-counter drugs, vitamins, herbal products and dietary supplements. Patients frequently do not consider contraceptives, herbal products and dietary supplements as drugs. However, because they can interact adversely with existing medications, it is important to specifically ask about their use. (See the Complementary & alternative therapies box.) Examples of specific prescription and over-the-counter medications to ask about include corticosteroids, oral contraceptives, antibiotics, diuretics, aspirin, antacids and laxatives. The patient’s medications can also provide clues for the nurse to explore other important health problems—such as mental health issues if a patient discloses that they are taking anti-anxiety, anti-depressant or anti-psychotic medication. Due to the stigma surrounding mental illness, questions about these issues need to be handled extremely sensitively.

Assessment of use of herbal products and dietary supplements

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Why assessment is important

• Herbal products and dietary supplements may have side effects and/or may interact adversely with prescription or over-the-counter medications.

• Patients at high risk for drug–herb interactions include those taking anticoagulant, antihypertensive or immune-regulating therapy and patients undergoing anaesthesia.

• Many patients do not tell the healthcare provider that they are using herbal products and dietary supplements. They may fear that the healthcare professional will disapprove of their use.

• Many herbal preparations contain a variety of ingredients. It is useful if the patient or carer can bring labelled containers to the healthcare site to determine the composition of the products.

The nurse’s role

• Patients typically will share this information with their nurse if they are specifically asked.

• The nurse should create an accepting and non-judgemental attitude when assessing use of or interest in herbal products or dietary supplements.

• It is helpful to use open-ended questions such as, ‘What types of herbs, vitamins or supplements do you take?’ and ‘What effects have you noticed from using them?’ The nurse should also respond to patients with comments that invite an open-minded discussion.

• The nurse should document the use of any herbal product(s) or dietary supplements in the patient database.

Older patients, in particular, should be questioned about drug routines. Changes in absorption, metabolism, reaction to drugs and elimination of drugs, as well as surgery and concurrent disease, make drug-related concerns a serious potential problem for older adults.6

FUNCTIONAL HEALTH PATTERNS

The nurse assesses the patient’s functional health patterns to identify patient strengths in function and to determine whether dysfunctional health patterns and/or potential dysfunctional patterns exist. Dysfunctional health patterns help identify potential risk conditions. Use of Gordon’s functional health patterns framework for assessment assists the nurse in differentiating between areas, allowing independent nursing intervention and areas requiring collaboration or referral. Table 3-2 presents an overview of the content usually included in each functional health pattern.

HEALTH PERCEPTION–HEALTH MANAGEMENT PATTERN

Assessment of the health perception–health management functional health pattern focuses on the patient’s perceived level of health and wellbeing and on personal practices for maintaining health. This includes preventative screening activities, such as breast and testicular examinations; colorectal cancer, hypertension and cardiac risk factor screening; Papanicolaou (Pap smear) test; and immunisations, such as tetanus, pneumonia and flu vaccines.

The questions for this pattern also seek to identify risk factors by obtaining a family history, a history of health habits (e.g. smoking, alcohol, drug use) and exposure to environmental hazards.

There are several ways to identify the patient’s perceived level of health and wellbeing. First, when questioning the patient, the nurse determines the patient’s feelings of effectiveness at staying healthy by asking what helps and what hinders them to do this. Next, the patient is asked to describe their personal health overall and to raise any concerns they have about it. This information should be recorded in the patient’s own words. It is often useful to determine whether the patient considers their health to be excellent, good, fair or poor.

In addition, the patient is asked about their family history of major problems, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, cancer, diabetes mellitus, psychiatric illness and genetic disorders. Information about sexual abuse, violence and drug and alcohol use/abuse should also be obtained and the nurse needs to be able to provide appropriate information about the services that can be provided for people who identify issues in these areas. One of the objectives in this pattern is to identify any measures used by the patient to promote personal health.

If the patient is hospitalised, expectations of this hospitalisation visit should be determined. A personal description of the patient’s understanding of the current health problem, including a description of its onset, course and treatment, should be obtained. Determining what the patient does when they are ill is also important. These questions elicit information about a patient’s knowledge of their health problem, awareness of what should be done and their perceived ability to use appropriate resources to manage the problem. In addition, this information may be used to identify the patient’s learning needs and identify what information may be required in a patient education session.

The nurse also assesses the patient’s intellectual and physical developmental stage in this pattern. This ensures that care appropriate for the developmental capabilities of the patient is planned. Finally, the nurse should inquire about the sorts of healthcare practitioners that the patient visits to maintain their health, such as chiropractor, osteopath, naturopath, local doctor or dietician.

Nutritional–metabolic pattern

The processes of ingestion, digestion, absorption and metabolism are assessed in this pattern. A 24-hour dietary recall should be obtained from the patient. From this information the nurse can evaluate the quantity and quality of foods and fluids consumed. If a problem is identified, the nurse may request that the patient keep a 3-day food diary for a more careful analysis of dietary intake. Food frequency questionnaires based on weekly intake also provide a good way to obtain information from the patient. Metabolism is evaluated by questioning the patient about recent weight gain, weight loss, energy level and skin lesions or dryness.

The impact of psychological factors, such as depression, anxiety and self-concept, on nutrition is assessed. For example, ‘Is your appetite ever affected when you get anxious?’ is a good question to ask; if the patient gives a positive response to this, the nurse can ask a follow-up question, such as ‘Can you tell me more about that?’ Questions that elicit information about sociocultural factors, such as what money is available to spend on food and who prepares the meals, also need to be asked as these things may have an impact on what and when the patient normally eats.

Determining how the patient’s present condition has interfered with their normal eating patterns and appetite is important. If the patient’s present condition has produced symptoms such as nausea, gas or pain, the effect of these symptoms on appetite should be determined. Food allergies and the need for a special or restricted diet should be noted. Additional information about the patient’s nutritional status can be determined by asking specific questions such as ‘How many fruits and vegetables do you eat per day?’ and ‘Give me an example of your usual intake of meat’.

Elimination pattern

The nurse assesses bowel and bladder function in this pattern by asking about the frequency of bowel and bladder activity and by seeking a description of consistency, amount, colour and unusual odour. The patient should be asked whether frequency or pain is associated with defecating or urinating. If laxatives or enemas are used, the frequency, type and results should be noted. If any collecting devices are used, such as catheter or colostomy equipment, the nurse needs to ask about their use and care.

The skin is also assessed in the elimination pattern in terms of its excretory function and so the patient should be asked about the condition of their skin and whether excessive perspiration (sweating), oedema (swelling), pruritus (itchiness) and/or redness is ever a problem.

Activity–exercise pattern

In this pattern the patient’s usual exercise, activity, leisure and recreational regimen is assessed. The patient should be asked about their ability to perform activities of daily living. Table 3-1 includes the grading scale for self-care abilities under the activity–exercise pattern. If the patient is unable to perform activities of daily living, such as going to the toilet unassisted, eating and moving independently, the nurse needs to find out what specific problems cause these limitations. Chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue and weakness are problems that commonly result in an inability to perform some activities of daily living.

Sleep–rest pattern

This pattern describes the patient’s pattern of sleep, rest and relaxation in a 24-hour period. The individual’s perception of the effectiveness of their sleep and relaxation pattern is important. This information can be elicited by asking, ‘Do you feel rested when you wake up?’ Most people take the ability to quickly go to sleep and stay asleep for granted, unless they have a problem with doing either of those things. The patient’s particular routines, position, medications and environmental factors used to foster their ability to sleep need to be determined.

Cognitive–perceptual pattern

Assessment of this pattern involves a description of all senses (vision, hearing, taste, touch and smell) and cognitive functions, such as communication, memory and decision making. The patient should be asked about any sensory deficits that they have that affect their ability to perform activities of daily living, such as poor eyesight. Routine eye care, including the date of the last eye examination, should be elicited. Also, ways in which the patient compensates for any sensory–perceptual problems should be discussed and noted.

Patients should be asked how they communicate best (e.g. by talking things through with others or reading information) and about their understanding of their illness and treatment. This information can then be used by the nurse to plan appropriate patient teaching techniques.

Finally, pain is also assessed in this pattern. (See Ch 8 for details on pain assessment.)

Self-perception–self-concept pattern

This pattern attempts to elicit information that will give the nurse an idea about how the patient sees themselves (i.e. their self-concept). For example, a teenager may see herself as an ‘average teenager’ but a ‘little overweight’. An older person may describe himself as ‘not too bad for a 72-year-old as I can still do the things I want to do’. This is critical to understand the way the patient may interact with others. Included in these questions are attitudes about self, perception of personal abilities, body image and general sense of worth. Here the nurse asks the patient to describe themselves in a general way and then, more specifically, to describe how the health condition affects this perception of themselves. At this point, the nurse must try to put aside any personal judgements about the validity of how a patient perceives themselves and listen particularly to the feelings expressed in these answers. What concerns the patient about a personal situation may differ greatly from what concerns the nurse.

Role–relationship pattern

This pattern describes the roles and relationships that the patient has in their life, including their major responsibilities. It also examines the patient’s self-evaluation of their performance of the expected behaviours related to these roles. Here the nurse asks about the patient’s family, social and work relationships, and networks. The nurse needs to determine whether connections in these relationships are satisfactory or whether strain, unease or conflict is evident. The nurse should note the patient’s feelings about their role in these relationships and the effect the present condition has on their role and the relationship.

Sexuality–reproductive pattern

When asking questions related to this pattern, the nurse needs to assess a range of issues relating to sexuality, sexual activity and reproduction. Specifically, the nurse needs to determine whether there is a lack of knowledge in relation to an aspect of sexuality or reproductive function, whether the patient perceives a problem in the area of sexuality and whether their present health problem or treatment has an impact on this. Assessing this pattern is important because many illnesses, surgical procedures and medications affect sexual activity and perceived sexual attractiveness. When asking these questions the nurse needs to be aware of issues that may interfere with a patient giving absolutely truthful answers, such as the patient’s age, gender, sexual preference and developmental stage. As a result of these issues, obtaining information related to sexuality and sexual activity is often difficult. However, it is important to take a health history of this aspect of people’s lives, as a sense of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with this area can have a major impact on patients’ sense of self and self-esteem. Based on the complexity of the problem, the nurse may be able to provide limited information or refer the patient to a more experienced professional.

Coping–stress tolerance pattern

The questions in this pattern enable the nurse to ask a patient about their general coping patterns and the effectiveness of these in their life. This assessment involves asking the patient to identify what they perceive to be specific stressors or problems that confront them at the moment, to discuss and document any major losses or changes experienced in the previous year, and to discuss with the patient the ways that they think work best for them when dealing with life stressors.

Value–belief pattern

This pattern describes the values, goals and beliefs (including spiritual ones) that guide health-related choices.5 The patient’s ethnic background and the effects of their particular culture and beliefs about health and illness on health practices need to be noted. The patient’s wishes about continuation of religious practices and the use of religious articles should be noted and honoured. The possibility of a conflict in values or beliefs can be determined by asking a question such as, ‘Does the care plan we have put in place for you cause you any conflict in relation to your personal values or beliefs?’

Physical examination: objective data

GENERAL SURVEY

Following the nursing history, a general survey statement is made. The general survey is a statement of the nurse’s general impression of the patient, including observations of their behaviour. This initial survey is considered a scanning procedure and begins with the first encounter that the nurse has with the patient and continues during the health history interview.

Although the nurse may include other data that seem pertinent, the major areas usually included in the general survey statement are: (1) body features; (2) state of consciousness and arousal; (3) speech; (4) body movements; (5) obvious physical signs; (6) nutritional status; and (7) behaviour. Vital signs, height and weight are also often included in the general survey statement. The following is a sample of a general survey statement:

Mr Ho is a 34-year-old Asian man, BP 130/84 mmHg, HR 88 beats/min, RR 18 breaths/min. He has no distinguishing body features or visible marks on his skin. During the interview he was alert but seemed anxious; his speech was rapid and he seemed to have difficulty concentrating; he was constantly wringing his hands and shuffling his feet; he made very little eye contact and sat hunched up. His skin appeared flushed and his hands were clammy.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination is the systematic assessment of the physical and mental status of the patient and the findings are considered objective data. Throughout the physical examination, any positive findings are explored using the same criteria as in the investigation of a symptom during the nursing history (see Box 3-2). A positive finding indicates that the patient has or had the particular problem or sign under discussion. For example, if the patient with jaundice has an enlarged liver, it is a positive finding. Relevant information about this problem should then be gathered.

Negative findings may also be significant. A negative finding is the absence of a sign or symptom usually associated with a problem. For example, peripheral oedema is common with congestive heart failure. If oedema is not present in a patient with congestive heart failure, this should be specifically noted as ‘no peripheral oedema’.

Types

There are two types of physical examination: the screening physical examination and the focused (problem-centred) examination. The screening physical examination is performed for health surveillance and health maintenance purposes. It is an organised, purposeful check of major body systems to detect any possible problems. If a problem is detected in the course of the screening physical examination, a more detailed focused examination of the involved system should be done.

A focused (problem-centred) examination is a more detailed assessment of a particular body system. The patient’s clinical manifestations should alert the nurse to the appropriate focused examination. For example, abdominal pain indicates the need to do a focused examination of the abdomen. Some problems necessitate more than one focused examination. A complaint of headache may indicate the need to do musculoskeletal, neurological, and head and neck examinations.7 Together with these focused nursing examinations, the patient may need further investigations, such as an X-ray or ultrasound.

Techniques

Four major techniques are used in performing the physical examination: inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation. Not all assessment techniques are appropriate for all body parts and systems. The nurse will learn which techniques to use to elicit the most information. The techniques are usually performed in the sequence of inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation. The only exception to this sequence is for the abdominal examination. In this situation the sequence is inspection, auscultation, percussion and palpation, because palpation and percussion of the abdomen before auscultation can alter bowel sounds and produce false findings.

Inspection

Inspection is the visual examination of a part or region of the body to assess normal conditions or deviations from normal. Inspection is more than just looking: the technique is deliberate, systematic and focused. The nurse compares what is seen with the known, generally visible characteristics of the body part being inspected. For example, most 30-year-old men have hair on their legs. Absence of hair may indicate a vascular problem and signal the need for further investigation, or it may be normal for a patient of a particular ethnicity or lifestyle choice.

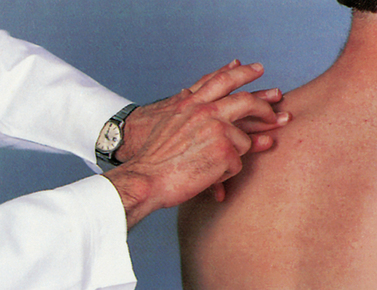

Palpation

Palpation is the examination of the body through the use of touch. The use of light and deep palpation can yield much information related to masses, organ enlargement, tenderness or pain, swelling, muscular spasm or rigidity, variations in voice sounds felt in different parts of the chest and crepitus (which sounds like hair rubbing together, and may be heard when pressing on broken bones rubbing together or when there is air in tissues close to the skin).8 Different parts of the hand are more sensitive for specific assessments. For example, the tips of the fingers are used to palpate lymph nodes, the dorsa of the hands and fingers are used to assess temperature, and the palmar surface is best suited for feeling vibrations (see Fig 3-2).

Percussion

Percussion is an assessment technique involving the production of sound to obtain information about the underlying area. The percussion sound may be produced directly or indirectly. Direct percussion is performed by directly tapping the body with one or two fingers to elicit a sound. Indirect, or mediated, percussion is the more common percussion technique. The middle finger (pleximeter) of the non-dominant hand is placed firmly against the body surface. The tip of the middle finger of the dominant hand (plexor) strikes the distal phalanx or the distal interphalangeal joint of the pleximeter finger (see Fig 3-3). A relaxed wrist and rapid strike produce the best sounds. The sounds and vibrations produced are evaluated relative to the underlying structures. Deviation from an expected sound may indicate a problem. For example, the usual percussion sound in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen is tympany. This means that in a healthy person the nurse would hear a loud, high-pitched sound. Dullness in this area may indicate a problem that should be investigated. (Specific percussion sounds of various body parts and regions are discussed in the appropriate assessment chapters.)

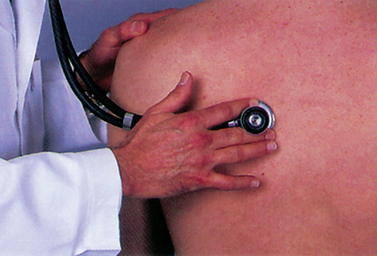

Auscultation

Auscultation is listening to sounds produced by the body to assess normal conditions and deviations from normal. Auscultation is usually indirect, using a stethoscope to clarify sounds by blocking out extraneous sounds (see Fig 3-4). The bell of the stethoscope is more sensitive to low-pitched sounds, whereas the diaphragm of the stethoscope is more sensitive to high-pitched sounds. Auscultation is particularly useful in evaluating sounds from the heart, lungs, abdomen and vascular system. (Specific auscultatory sounds and techniques are discussed in the appropriate assessment chapters.)

Equipment

The equipment needed for the physical examination should be easily accessible during the examination (see Box 3-3). Organising equipment before the examination saves time and energy for the nurse and the patient. Lack of organisation can discourage the patient and lead to lack of trust and confidence in the nurse. (The uses of specific pieces of equipment are discussed in the appropriate assessment chapters.)

Developing a system

The physical examination should be performed systematically and efficiently. Explanations should be given to the patient as the examination proceeds. The factors to be considered are the nurse’s efficiency and the patient’s comfort, safety and privacy. The examiner is less likely to forget a procedure, a step in the sequence or a portion of the body if the same sequence is followed every time. Table 3-3 presents an outline for the screening physical examination that is organised, logical and complete. Adaptations of the physical examination are often useful for older patients, who may have age-related problems such as decreased mobility, limited energy and perceptual changes.9 An outline listing some of the useful adaptations for older adults is found in Box 3-4.

TABLE 3-3 Outline for screening physical examination

Inspect and palpate head for the following:

• Sensory (CN V, light touch, pain)

• Motor (CN VII, shows teeth, purses lips, raises eyebrows)

• Looks up, wrinkles forehead (CN VII)

• Raises shoulders against resistance (CN XI)

Inspect and palpate (occasionally auscultate) neck for the following:

• Skin (vascularity and visible pulsations)

• Midline structure (trachea, thyroid gland, cartilage)

• Lymph nodes (preauricular, postauricular, occipital, mandibular, tonsillar, submental, anterior and posterior cervical, infraclavicular, supraclavicular)

Inspect and palpate eyes for the following:

Position and movement of eyelids (CN VII) S

• Extraocular movements (CN III, IV, VI)

Inspect and palpate ears for the following:

• Auditory acuity (weber’s or Rinne, whispered voice, ticking watch) (CN VIII)

Inspect and palpate nose and sinuses for the following:

• External nose—shape; appearance

• Internal nose—patency of nasal passages; shape; turbinates or polyps; discharge

• Frontal and maxillary sinuses

Inspect and palpate mouth for the following:

• Lips (symmetry, lesions, colour)

• Buccal mucosa (colour, consistency, salivary ducts)

• Teeth (absence, state of repair, colour)

• Tongue for strength (asymmetry, ability to stick out tongue, side to side, fasciculations) (CN XII)

• Assess breasts for configuration, symmetry, dimpling of skin

• Assess nipples for rash, direction, inversion, retraction

• Initiate teaching or review of breast self-examination

• Inspect for PMI, other praecordial pulsations

• Palpate for thrills, lifts, heaves, tenderness over praecordium

• Inspect neck for venous distension, pulsations, waves

• Auscultate for rate and rhythm, character of S1 and S2 in the aortic, pulmonic, Erb’s point, tricuspid, mitral areas; bruits at carotid, epigastrium; breath sounds at RML

• Inspect for scars, shape, symmetry, bulging, muscular position and condition of umbilicus, movements (respiratory, pulsations, presence of peristaltic waves)

• Auscultate for peristalsis, bruits

• Percuss border of liver, four abdominal quadrants

• Palpate to confirm positive findings; check liver (size, surface contour, tenderness); spleen; kidney (size, contour, consistency, tenderness); urinary bladder (distension); femoral pulses; inguinofemoral nodes

11. Genitalia*

• Inspect penis, noting hair distribution, prepuce, glans, urethral meatus, scars, ulcers, eruptions, structural alterations

• Inspect epidermis of perineum, rectum

• Inspect skin of scrotum; palpate for descended testes, masses, pain Female external genitalia

• Inspect hair distribution; mons pubis, labia (minora and majora); urethral meatus; Bartholin’s, urethral, Skene’s glands (may also be palpated, if indicated); introitus

AP, anteroposterior; CN, cranial nerve; CVA, costovertebral angle; PMI, point of maximal impulse; RML, right middle lobe; S1 and S2, heart sounds

*If the nurse has the appropriate training, the speculum and bimanual examination of women and the prostate gland examination of men should be performed after this inspection.

BOX 3-4 Adaptations in physical assessment techniques

GERONTOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES IN ASSESSMENT

General approach

Keep the patient warm and comfortable because loss of subcutaneous fat decreases ability to stay warm. Adapt positioning to physical limitations. Avoid unnecessary changes in position. Perform as many activities as possible in the position of comfort for the patient.

Head and neck

Provide a quiet environment free from distraction because of the patient’s sensory deficits (e.g. decreased vision, touch, hearing).

Extremities

Use non-vigorous movements and reinforcement techniques. Avoid having the patient hop on one foot or perform deep knee bends because of the patient’s limited range of motion of the extremities, decreased reflexes and diminished sense of balance.

Chest

Adapt the examination for changes due to decrease in force of expiration, weakened cough reflex and shortness of breath.

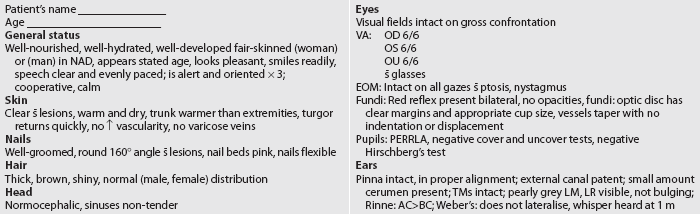

Recording the screening physical examination

Only abnormal findings should be recorded during the actual examination. This prevents needless interruptions during the examination to write lengthy normal findings. At the conclusion of the examination, the nurse should combine the normal and abnormal findings in a carefully recorded physical examination. Table 3-4 is an example of how to record a screening physical examination on a healthy adult. See Table 5-5 and the age-related assessment findings in each assessment chapter for helpful references in recording age-related assessment differences.

TABLE 3-4 Recording a screening physical examination

AC>BC, air conduction greater than bone conduction; BUS, Bartholin’s gland, urethral meatus, Skene’s duct; coord, coordination; EOM, extraocular movements; FN, finger to nose; ICS, intercostal space; LM, landmarks; LR, light reflex; MCL, midclavicular line; NAD, no acute distress; PERRLA, pupils equal, round, reactive to light and accommodation; prop, proprioception; ROM, range of motion;  , without; TM, tympanic membrane; VA, visual acuity.

, without; TM, tympanic membrane; VA, visual acuity.

* Some of these data should be obtained from a pelvic examination if the nurse has the appropriate training.

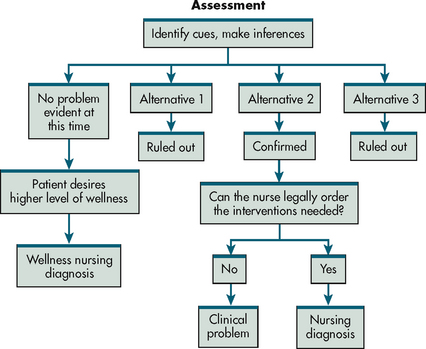

Problem identification and nursing diagnoses

After completing the history and physical examination, the nurse clusters and analyses the data to develop a list of nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems. Figure 3-5 illustrates the problem identification phase of the nursing process. Nursing diagnoses are health-related problems that are managed primarily by nursing care. (Ch 1 explains the process of establishing nursing diagnoses.)

A complete and accurate nursing assessment is the cornerstone of effective nursing care. Once nurses have experience, they will stop thinking about what type of assessment is needed (e.g. screening versus focused examination) and what steps are needed to carry out the assessment and will instinctively know what information is most important and the techniques required to capture those data. However, in the beginning, it helps to be systematic and organised with nursing assessments.

1. The nursing history provides information to assist the nurse primarily in:

2. The nurse would place information relating to the patient’s concern that their illness is threatening their job security in which of the following functional health patterns?

3. To examine the skin of a patient who has a full-thickness burn, the nurse primarily uses the technique of:

4. A focused (problem-centred) examination is performed when:

5. During a screening history and physical examination, the first information the nurse records is the:

1 Jarvis C. Physical examination and health assessment, 5th edn. St Louis: Sunders, 2008.

2 Wilson S, Giddens J. Health assessment for nursing practice, 4th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2009.

3 Changing Minds. Open and closed questions. Available at http://changingminds.org/techniques/questioning/open_closed_questions.htm. accessed 13 March 2011.

4 Stein-Parbury J. Patient and person: interpersonal skills in nursing. Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

5 Gordon M. Manual of nursing diagnosis, 12th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2010.

6 Lehne R. Pharmacology for nursing care, 7th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2010.

7 Seidel HM, Ball JW, Dains JR, Benedict GW. Mosby’s guide to physical examination, 7th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2010.

8 Weber J, Kelley J. Health assessment in nursing, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.

9 Eliopoulos C. Gerontological nursing, 7th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.