Chapter 9 Palliative care

1. Discuss palliative care and a palliative approach.

2. Outline the physical manifestations at the end of life.

3. Outline the common psychological manifestations at the end of life.

4. Explain the process of loss and grief at the end of life.

5. Examine the cultural and spiritual issues related to palliative care.

6. Discuss ethical and legal issues in palliative care.

7. Outline the nursing management for the dying patient.

8. Explore the special needs of family caregivers in palliative care.

9. Discuss the special needs of the nurse who cares for dying patients and their families.

Introduction

Living and dying are part of the life cycle and therefore dying is a normal part of life. However, in some cases dying may be treated as an illness,1 and in Western societies mortality and the death experience can be difficult and awkward topics to discuss and accept. Before the 1960s patients who were not expected to survive were placed in isolated hospital areas, were given less-than-quality care and died without appropriate medical care.

Today, with the increasing number of older people living within the community, many of whom have chronic disease, the terminal phase of illness and dying are not viewed as the taboo topics that they once were.2 The special needs of the dying and those with progressive life-limiting illness are now acknowledged and integrated into care. Death and dying are researched by scientists, healthcare professionals, theologians and laypersons. Dying is a process that involves the dying person and their loved ones on many levels—physical, psychological, spiritual and social. While there are commonalities, each person’s journey towards death is an individual one, requiring from healthcare professionals sensitivity, respect, support and excellence in symptom management.

The term ‘good death’ has been used since the beginning of the modern hospice movement in the 1960s. It refers to a death in which it is deemed that the patient’s needs have been met—that is, symptoms have been well managed and the patient has died peacefully and with dignity in the place of their choosing. This ideal cannot always be met for a variety of reasons. In recent years the ideology of a ‘good death’ has been critiqued because of the potential for labelling patients as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ patients, depending on their adherence to the expectations involved in a ‘good death’.3 The aim of care at the end of life is to support people to die the death congruent with their life and wishes, as far as this is possible. Recognition that this is not always able to be achieved avoids the potential judgement of failure in achieving a ‘good death’.

Palliative care definitions

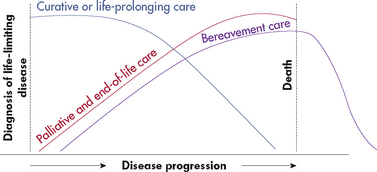

Palliative care is holistic, active care of patients whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment.4 The World Health Organization defines palliative care as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of physical, psychosocial and spiritual suffering. The goals of palliative care are to: (1) provide comfort and supportive care from the time of diagnosis, during the dying process and, for the family, beyond; (2) maximise the quality of the remaining life (see Fig 9-1); and (3) help ensure a dignified death (see Fig 9-2).

Figure 9-2 Integrated model of curative care, palliative and end-of-life-care, and bereavement care.

Palliative care focuses healthcare towards allowing natural death in a pain-controlled and symptom-controlled environment with psychosocial and spiritual support. Both acute and rehabilitative treatment can be a part of this approach in managing symptoms and in ensuring the best possible quality of life for patients. The unit of care is the patient and ‘family’ (as defined by the patient).

The approach used by primary care services and practitioners to provide palliative care is called the palliative approach.5 A key concept of the palliative approach is meeting the holistic needs of patients and caregivers and this needs to be reflected in assessment. Additional concepts are the primary treatment of pain and the provision of physical, psychological, social and spiritual care. Specialist palliative care services provide expert, interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with symptoms or issues requiring specialist input. These services may take primary responsibility for care or act as consultants to the patient’s primary care team.6 Palliative interventions are non-curative interventions implemented for symptom management or the improvement of quality of life. They may be instituted by clinicians who are not specialists in palliative care. Examples are palliative radiotherapy or pain relieving anaesthetic techniques.

End-of-life care is a term sometimes used interchangeably with palliative care. End of life has been defined as the concluding phase of a normal life span, recognising that life can end at any age.7 The time from diagnosis of a life-limiting illness to death varies considerably depending on the person’s diagnosis and extent of disease.

A life-limiting illness is an illness where it is expected that death will be a direct consequence of that illness. This definition is inclusive of illness of both a malignant and a non-malignant nature.4 Patients with life-threatening conditions such as cancer, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and end-stage cardiovascular, respiratory or renal disease may be appropriate for palliative care.8 In addition, patients with disease processes such as Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, motor neuron disease, Parkinson’s disease and liver disease may require palliative care.9

Hospice was the term used before palliative care and these terms are sometimes used interchangeably. Hospice in Australasia usually refers to inpatient units dedicated to offering palliative care. Patients are admitted to a hospice for symptom management when this is difficult to achieve at home, to allow their family caregiver(s) some respite, or for care in the terminal phase of their illness (sometimes termed terminal care). Increasingly, in both Australia and New Zealand hospice services have very active home care programs so that hospice services can be offered on an inpatient or community basis.

Palliative care contexts

Palliative care is provided in a range of settings in the community, such as private homes and aged care facilities. Home care is provided on a part-time, intermittent, on-call, regularly scheduled or continuous basis. Palliative care services are available to provide help to patients and families in their homes and support for primary caregivers. Inpatient palliative care is reserved for acute pain or other symptom management, for respite care when families or caregivers need a break, or for palliative care when this is not possible at home. Inpatient hospice settings have been deinstitutionalised to make the atmosphere as relaxed and home-like as possible (see Fig 9-3). Palliative care programs are organised under a variety of models. Some are hospital-based and others are freestanding or community-based, volunteer-intensive programs. However, regardless of their organisation, all programs emphasise palliative rather than curative care.

Figure 9-3 Inpatient hospice settings have been deinstitutionalised to make the atmosphere as relaxed and home-like as possible.

Much palliative care takes place in aged care facilities. Patients in these facilities have high acuity and high nursing care needs. As opposed to the more acute palliative care and life-limiting illness phases of people with cancer, who have been traditionally thought of as palliative care patients, the illness and dying trajectory of most people receiving palliative aged care is different. These people usually have several comorbidities associated with their advanced age and a slower illness trajectory.10 Their care involves a palliative approach and may or may not require the consultative services of a specialist palliative care team. Excellence in symptom management and the psychosocial and spiritual support of the person and family remain the hallmarks of palliative aged care.11

The palliative care nurse is an integral part of the specialist palliative care team, which is an interdisciplinary team of professionals and volunteers. Palliative care nurses work collaboratively with palliative care doctors, pharmacists, dieticians, physiotherapists, social workers, clergy, pastoral care workers, bereavement counsellors and volunteers to provide care and support to the patient and family members. Palliative care nurses are educated in pain control and symptom management. As with home healthcare, palliative care requires teaching skills, compassion, flexibility and adaptability to patient needs. Currently, the education of specialist nurse practitioners in palliative care is being developed across Australia and New Zealand.

The decision to begin palliative care of a patient can be difficult. Several reasons for this exist. Patients, families and doctors may lack information about palliative and hospice care. Doctors may be reluctant to refer because they sometimes view a patient’s decline as their personal failure, and some patients or family members see it as giving up. Doctors, patients, family members or registered nurses may make referrals to a palliative care service. The patient’s consent to be admitted to the service is paramount.

Physical manifestations at the end of life

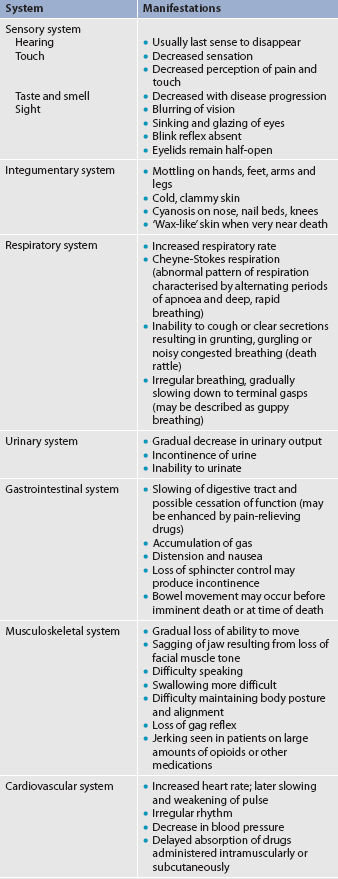

The process of dying varies in length, according to the cause of death. However, there are several common physiological changes close to or at the time of death. Death occurs when all vital organs and systems cease to function. Death is the irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function or the irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem. Trauma and disease processes can affect physical manifestations at the end of life. As death approaches, metabolism is reduced and the body gradually slows down until all organs cease functioning. Generally, respirations cease first. Then the heart stops beating within a few minutes. Physical manifestations of approaching death are listed in Table 9-1.

TABLE 9-1 Physical manifestations of approaching death

Source: Adapted from End-of-life care. Available at www.scribd.com/doc/30927722/End-of-Life-Care.

SENSORY CHANGES

There are alterations in the interpretation of sensory input due to decreased oxygenation and circulation to the brain. Sensory changes can include blurred vision, decreased sense of taste and smell, and decreased pain and touch perception. The blink reflex is eventually lost and the patient appears to stare. The sense of touch decreases first in the lower extremities because of circulatory alterations. Hearing is commonly believed to be the last sense to remain intact at the end of life.

CIRCULATORY AND RESPIRATORY CHANGES

With decreased oxygenation and altered circulation causing metabolic changes, the heart rate slows and weakens and the blood pressure falls progressively. Respirations may be rapid or slow, shallow and irregular. Breath sounds may become wet and noisy, both audibly and on auscultation. Noisy, wet-sounding respirations, termed the death rattle, are due to mouth-breathing, the accumulation of mucus in the airways and the inability of the patient to clear this mucus due to muscle weakness and decreased gag reflex. Cheyne-Stokes respiration is an abnormal pattern of breathing characterised by alternating periods of apnoea and deep, rapid breathing. This type of breathing is usually seen as a person nears death.

The generalised decreased circulation is especially noticeable on the skin. The extremities become pale, mottled and cyanotic. The skin feels cool to touch, first in the feet and legs, then progressing to the hands and arms, and finally progressing to the torso. The skin may feel warm because of an elevated body temperature related to an underlying disease process and changes in hypothalamic function.

LOSS OF MUSCLE TONE

As death becomes imminent, metabolic changes cause the muscular system to weaken gradually, leading to sluggish functional abilities. Facial muscles lose tone, causing the jaw to sag. Decreased muscle coordination leads to difficulty in speaking. Swallowing becomes increasingly difficult and the gag reflex is eventually lost. Gastrointestinal motility and peristalsis diminish, leading to constipation, gas accumulation, distension and nausea. Pain-relieving medications may exacerbate these gastrointestinal manifestations. The ability of the urinary system to function and produce urine decreases. Loss of sphincter control can lead to faecal and urinary incontinence. If the patient’s death is imminent, only comfort measures are instigated—that is, no medical interventions are undertaken at this time. However, if the patient is conscious and/or distressed by these symptoms, comfort measures such as appropriate bowel and urine management can be instigated.

BRAIN DEATH

The diagnosis of death is based on brain death. Brain death occurs when the cerebral cortex and brainstem stop functioning or are irreversibly destroyed. The cerebral cortex, or the higher brain, is responsible for voluntary movement and actions, as well as for cognitive functioning, whereas the brainstem controls the automatic functions of breathing, temperature control and blood pressure.

The Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology recommends diagnostic criteria guidelines for clinical diagnosis of brain death in adults. These criteria for brain death include coma or unresponsiveness, absence of brainstem reflexes, and apnoea.12 Specific assessments by a doctor are required to validate each of these criteria.13,14

In Australia, all jurisdictions except Western Australia have a statutory definition of ‘death’, which states that death involves irreversible cessation of all brain function or irreversible cessation of blood circulation. In Western Australia, although not a statutory definition, for the purposes of removal of human tissue, the legislation provides that removal will not occur until two medical practitioners have certified that all brain function has irreversibly ceased.15 In New Zealand, according to the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS), there is no statutory definition of death.

Currently, legal and medical standards require that all brain function must cease for brain death to be pronounced and life support to be disconnected by the doctor. A diagnosis of brain death is of particular importance when organ donation is an option.

Psychosocial manifestations at the end of life

A variety of feelings and emotions affect the dying patient and family at the end of life. Specific psychosocial manifestations are listed in Box 9-1. Most people struggle from the outset of a diagnosis of an illness that potentially shortens their life. Time may be needed to process the impending death and to deal with their emotional responses. The patient and family often feel overwhelmed, fearful, powerless and fatigued. The patient’s needs and wishes must be respected. Patients need time to ponder their thoughts and express their feelings. Response time to questions may be sluggish because of fatigue, weakness, the effects of medications and confusion. Facilitating good communication between patients and their family and caregivers is an important role for nurses. Research has demonstrated the importance of pre-loss communication between the bereaved and the deceased and its impact on post-loss outcomes.16

BOX 9-1 Psychosocial manifestations of approaching death

Source: Adapted from End-of-life care. Available at www.scribd.com/doc/30927722/End-of-Life-Care.

Grief

Grief is the emotional and behavioural responses to loss. It is an emotional reaction that is necessary to maintain quality in both emotional and physical wellbeing. The grieving process involves a total individual experience associated with thoughts, feelings and behaviours. Grieving related to losses from death and dying is a complex and intense emotional experience. The dying person experiences and grieves multiple losses, such as independence, mobility and societal roles before the finality of death. Those left behind (the bereaved) also go through the process of grief.17 It is important to note that grief for the patient, family and significant others may begin before death occurs. Working through the grief process helps the dying person and their significant others adapt to the loss.

Grief is manifested in a variety of ways and can include shock and disbelief, sadness, guilt, anger, fear and physical symptoms such as tiredness and nausea.18 Every loss is as different as each person is unique. There are no set ways of expressing and working through grief. Individuals experience different aspects of the grieving process at different times. The individual’s cultural, religious or spiritual beliefs and value system influence grief reactions. The intensity of grief is driven by an individual’s personality, the nature of the relationship with the dying person, concurrent life crises, coping resources and the availability of support systems.

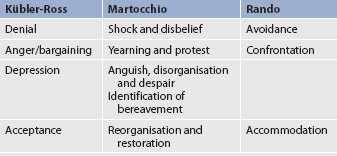

Well-recognised grief researchers and theorists such as Kübler-Ross, Martocchio and Rando have identified stages of grief.19–21 Kübler-Ross identified denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance as the five stages of grieving.19 Martocchio presented five clusters of grief to include: (1) shock and disbelief; (2) yearning and protest; (3) anguish, disorganisation and despair; (4) identification of bereavement; and (5) reorganisation and resolution.20 Rando refined three phases of responses to grieving that were identified as avoidance, confrontation and accommodation.21 A comparison among the three is listed in Table 9-2. Further research into grief has identified the dual-process model of grieving and recognises that bonds with the person who has died continue, albeit in a different form (known as ‘continuing bonds’).22 It is important to recognise, however, that grief is an individual process and may not follow set patterns or stages.

TABLE 9-2 Comparison of stages of grieving

Source: Kübler-Ross E. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan; 1969. Martocchio BC. Grief and bereavement. Healing through hurt. Nurs Clin North Am 1985; 20:327–341. Rando TA. Treatment of complicated mourning. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 1993.

Grief has been described as ‘work’ that grieving people need to work through during the period of bereavement. For example, Worden has identified four tasks of grief as: (1) accepting the reality of the loss; (2) experiencing the pain of grief; (3) adjusting to an environment without the deceased; and (4) withdrawing and reinvesting emotional energy.23 The latter involves remembering the deceased yet being open to new relationships.

Most people experience healthy, uncomplicated grief. The process of resolution in normal grief may take months to years. Complicated grief, while uncommon, can manifest as chronic grief when the intensity does not wane after the first year.17 The grieving person becomes ‘bogged down’ in the grieving process. Grief can manifest as conflicted grief when the bereaved person has not resolved ambivalent feelings towards the deceased. Grief can manifest as absent grief when the bereaved person appears to be coping and carrying on as if nothing has happened.

Grief that is prolonged, unresolved or disruptive may be termed maladaptive or dysfunctional grief. Grief that is delayed or exaggerated may be identified as dysfunctional. Dysfunctional grieving may relate to a real loss or a perceived loss. It may occur when grief is not resolved from a prior experience or when the expression of grief is blocked in some way.17 With dysfunctional grief, feelings and behaviours may become exaggerated and disruptive to a person’s usual lifestyle.

Grief that is helpful or that assists the person in accepting the reality of death is called adaptive grief. Adaptive grief is a healthy response with a wide range of characteristics and expressions. It may be associated with grieving before a death actually occurs or when the reality that death is inevitable is known. In contrast to earlier understandings of bereavement counselling, it is now recognised that, in adaptive grief, the relationship of the bereaved with the person who has died changes, but a continuing bond remains.2,17,23 The grief process takes time, energy and work. Goals for the grieving process include resolving emotions, reflecting on the dying person, expressing feelings of loss and sadness, and valuing what has been shared. Nurses need to be aware of the current theories and research on grieving to enable them to recognise when a person is experiencing uncomplicated or complicated grief. Nurses can assist people through the grieving process or, if necessary, refer them for counselling.

Culturally competent palliative care

People experiencing the inevitability of death are in need of caregivers who are knowledgeable about personal issues and attitudes that affect the end-of-life experience. The attitudes of the dying person, family, significant others and nurses affect the death experience.

Healthcare professionals must be aware of cultural differences as they care for patients and families (see Fig 9-4).24 An adequate understanding of cultural, religious, spiritual and familial influences is beneficial when focusing on the dying person’s and family’s needs, wants and fears. Each person’s responses to the influences from culture, religion, family and spirituality will be unique.

Figure 9-4 Healthcare professionals must be aware of cultural differences as they care for patients and families.

Culture and spiritual and religious beliefs affect a person’s understanding of and reaction to death or loss. Frequently, beliefs and attitudes are interrelated between culture and religion. The Western work ethic generally emphasises independence, self-reliance, hard work and rugged individualism. With these attitudes many people believe that privacy is imperative. Death and dying tend to be private matters shared only with significant others. Often, feelings are repressed or internalised. People who believe in ‘toughing it out’ or ‘being strong’ may not express themselves when they are experiencing a tragic loss.

In multicultural societies such as Australia and New Zealand, knowledge of and sensitivity to cultural beliefs and practices regarding death and dying are important. For example, in some Indigenous Australian groups, it is forbidden to mention the name of an Indigenous person who has died; and in Indigenous Australian and some Mediterranean and Asian cultures, speaking about a person’s dying to that person is taboo. In such cases, it is important to ask the patient or family who is the most appropriate person to speak to about the patient’s illness. This may be a family member or a community elder.25

For Māori, cultural practices of tangi or tangihanga are central to the processes of grieving for someone who has died. The practices and protocols of the tangihanga vary from tribe to tribe but it is common practice that the tupapaku (the body of the person who has died) not be left alone at any time. At one time the tangi was always held on the marae but today it may also be held in private residences or the funeral parlour. More information can be found on the Korero Māori website (see the Resources on p 172). Nurses should seek advice regarding cultural safety for patients and extended family at this time. (Cultural safety is discussed in Ch 2 and in other sections of this textbook.)

Culturally, expressions of pain and other symptoms vary. It is known that ethnic minority groups are often undertreated in terms of pain medication.26 Providing culturally competent care requires greater attention to assessment of non-verbal cues, such as grimaces, body position and decreased or guarded movements.27 Issues related to pain assessment and management are discussed in Chapter 8.

Spiritually appropriate palliative care

Assessment of spiritual needs in palliative care is a key consideration (see Fig 9-5). Spiritual needs do not necessarily equate to religion, so clarifying the difference between these two concepts is important.2 A person may be of no particular faith but have a deep spirituality. Many times at the end of life, people question their beliefs about a higher power, their own journey through life, religion and an afterlife. Research has indicated that once patients are diagnosed with a life-limiting illness, a spiritual journey begins.28 Some may choose to pursue a spiritual path; some may not. Each individual’s choice needs to be respected.29

Deep-seated religious beliefs may surface when the patient has to deal with the diagnosis of their life-limiting illness and related issues. Some patients may experience spiritual distress, with a challenge to and questioning of beliefs and values surrounding the past, present and future. Spiritual distress has been defined as a disruption in one’s beliefs or value system.30 People experiencing spiritual distress may question the meaning of life, be afraid or angry, or express a sense of emptiness.

Some dying patients are secure in their faith about the future. It is common to observe patients relinquishing material values of life and focusing on values that they believe will lead them on to another place. Patients whose spiritual lives appear to be in order usually have a more peaceful death.31

Differences among cultural, religious and spiritual beliefs and values are innumerable. There may be barriers to the implementation of spiritual care, so attention to these barriers and strategies to assist in their removal should be considered.2 Nursing assessments of beliefs and preferences should be completed on an individual basis to avoid stereotyping individuals with particular behaviours and belief systems. A helpful guide to the assessment of spiritual needs identifies questions to be asked around the areas of meaning in life, source of hope, coping strategies in crises and any spiritual or religious practices.2,32 Such questions may include:

• Are there any religious/spiritual activities or practices that have been interrupted because of your illness?

• Do you feel at peace with the changes in your life that have come about because of your illness?

• Has your illness been a hard thing spiritually for you?

• Would you like to speak to someone about any spiritual/religious concerns?33

It can be uncomfortable and challenging to discuss this area with patients. If the nurse finds it difficult to meet a patient’s spiritual needs, it would be appropriate to refer the patient to the relevant religious/spiritual personnel.

Legal and ethical issues affecting palliative care

Patients and families struggle with many decisions during the terminal illness and dying experience. Many people decide that the outcomes related to their care should be based on their own wishes. The decisions may involve the choice for: (1) organ and tissue donation; (2) advance directives (e.g. medical power of attorney, living wills); and (3) resuscitation.

ORGAN AND TISSUE DONATION

People who are legally competent may choose to donate their organs. Any body part or the entire body may be donated. The decision to donate organs or to provide anatomical gifts may be made by a person before death or by immediate family members following death. Family permission must be obtained at the time of donation.

Some people carry donor cards and, in Australia, several states allow organ donation intent to be marked on the driver’s licence. The names of agencies that handle organ donation vary by state. Common names for such an agency are organ bank, organ-sharing network or organ-sharing alliance. The Australian Organ Donor Register is managed through Medicare and is a national register for organ and/or tissue donation for transplantation. Both organ and tissue donations follow specific legal guidelines. Legal requirements and facility policies for organ and tissue donation must be followed. The doctor must be notified immediately when organ donation is intended because some tissues must be used within hours after death.34

In New Zealand, people can indicate their wish to be considered for organ donation by having the word ‘donor’ printed on their driver’s licence and on their record in the driver’s licence database. However, this is not in itself considered informed consent and families are always asked to give consent for organs to be taken after the person’s death.

LEGAL DOCUMENTS USED IN PALLIATIVE CARE

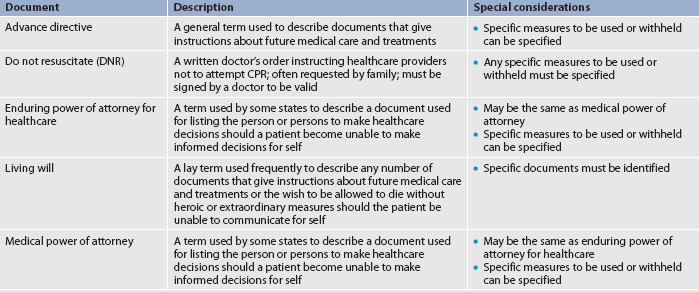

Each state and territory in Australia has its own legislation regarding patients’ wishes for end-of-life care. Advance directives are written statements of a person’s wishes regarding medical care in certain future circumstances. The first advance directive in Australia was known as a living will. It was passed by the South Australian parliament as the Natural Death Act 1983. By virtue of the Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act 1995 (SA), individuals can secure their right to control medical treatment in prescribed circumstances by creating an advance directive and appointing a medical agent under a medical power of attorney.35 Most Australian states and territories now have legislation enabling an advance directive to be completed. Table 9-3 identifies common legal and ethical documents used in palliative care. Copies of state-specific forms can be obtained from state government bookshops or the internet.

In practice, it is impossible to write directives to cover all eventualities. Therefore, appointing a medical power of attorney is considered a more effective tool for expressing patient wishes in a range of circumstances. Common law allows verbal directives to be given to doctors. In the event that the person is not capable of communicating their wishes, the family and doctor often agree on what measures will or will not be taken. The doctor must record the family’s decision.

RESUSCITATION

In the past 30 years cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) has become common practice in healthcare. Patients who suffered respiratory or cardiac arrest have been given CPR unless a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order was given by the doctor. Many times patients and families have had no choice as to whether CPR was used. In recent years, much has been written concerning the right to die and the right to choose whether or not to be resuscitated. Many people believe that the patient or family has the right to decide whether CPR will be used. It is no longer the sole decision of the doctor. The position statement of the Royal College of Nursing Australia for the role of the nurse in palliative care, which is currently under review, states that nurses must play a primary role in the implementation of the law.36 A doctor’s order should be written to include the information concerning the patient’s or family’s wishes for the use of CPR. A DNR or No CPR order allows the person to die with comfort measures only and without the interference of technology.

WITHHOLDING OR WITHDRAWING TREATMENTS

Patients’ express wishes within an advance directive should be clear so that there is no misinterpretation when following their instructions. In legal and ethical debates it is recognised that honouring the refusal of treatment (where the treatment is disproportionately burdensome to the patient, or will not benefit the patient) can be ethically and legally permissible. Additionally, the decision to withhold artificial nutrition and hydration should be made by the patient or surrogate with the healthcare team.37,38

The nurse needs to be aware of legal issues and the wishes of the patient. Advance directives and organ donor information should be located in the medical record and identified on the patient’s record and/or the nursing care plan. All caregivers responsible for the patient need to know the patient’s wishes. Additionally, the nurse is responsible for becoming familiar with state, local and agency procedures in palliative care documentation.

The New Zealand Palliative Care Strategy recommendation states: ‘Enhanced communication between health professionals and their patients/families is preferable to increased use of advanced directives.’39

Standards and guidelines for palliative care practice

Documents regarding standards for palliative care practice and guidelines for palliative care in specific settings have been developed to guide excellence in practice. The document, Standards for providing quality palliative care for all Australians, gives an overview of standards in each domain of practice.5 This latest edition of the (National Palliative Care) Standards was published in 2005 following a program of wide consultation with the palliative and end-of-life care sector. The Guidelines for a palliative approach in residential aged care provide evidence-based guidelines for palliative care in this setting.11 A companion set of evidence-based guidelines, A palliative approach to care for older adults in the community, has also been developed, along with a resource kit on providing culturally appropriate palliative care to Indigenous Australians.25 The Australian National Palliative Care Strategy is currently being updated.40 The basis for palliative care practice in New Zealand is The New Zealand palliative care strategy.39 Practice guidelines for specific topics are also issued by the New Zealand Guidelines Group (see Resources on p 172).

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Situation

A terminally-ill 50-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer has developed severe bone pain that is not adequately controlled by her present dose of intravenous morphine. She moans at rest and verbalises severe pain from any movement to reposition her. Even though she appears to sleep at intervals, she requests pain relief frequently and her family is demanding additional pain medication for her. At the team conference the nurses have discussed the need for more effective pain control but are concerned that additional pain medicine could hasten her death.

Important points for consideration

• Adequate pain relief is an important outcome for all patients but in particular for patients who are terminally ill. The principle of beneficence means that care is provided to benefit patients.

• When the goal of treatment of the terminally ill is providing adequate pain control to alleviate suffering, the goal is based on the principle of non-maleficence: preventing or reducing harm to the patient. The secondary effect of hastening the patient’s death is ethically justified.

• Euthanasia, the deliberate act of hastening death, is not part of palliative care practice (it is illegal throughout Australia and New Zealand).

• Adequate relief of suffering at the end of life is the major goal of palliative care.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: END OF LIFE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: END OF LIFE

Nursing care of patients with life-limiting illness and dying patients is holistic and encompasses all aspects of psychosocial, spiritual and physical needs. Nursing care focuses on the psychosocial manifestations and the grieving process, as well as the physical changes that are associated with dying. The patient and the family need to be the focus of nursing care. Respect, dignity and comfort are important for the patient and the family. In addition, nurses and other care providers must recognise their own needs when dealing with grief and dying.

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Assessment of those with life-limiting illness varies with the patient’s condition and proximity of approaching death. In general, the assessment is limited to essential data. On admission, the nurse documents the specific event or change that brought the patient into the healthcare agency. The patient’s medical diagnoses, medication profile and allergies are recorded. If the patient is alert, a brief review of the body systems should be completed to detect important signs and symptoms. Discomfort, pain, nausea and dyspnoea are carefully assessed so that prompt interventions can be implemented.

The functional assessment of activities of daily living elicits information about the patient’s abilities, food and fluid intake, patterns of sleep and rest, and response to the stress of the life-limiting illness. The nurse should assess the coping abilities of the patient and family, as well as undertaking a sensitive assessment of the patient’s spiritual needs and resources.

Ongoing physical assessment focuses on changes that accompany life-limiting illness, often at the transition stages between phases of the illness, such as from stable to unstable phases or from a deteriorating phase to the terminal phase of a person’s illness. Routine assessment of vital signs is not usually carried out. In the last few days of life as changes occur, assessment and documentation of the patient’s comfort level are important. This assessment is carried out gently and non-invasively. If the patient is conscious, their subjective assessment of level of comfort is the most significant indicator. If unconscious, the nurse needs to learn to read the physical signs of discomfort and distress.

Respiratory status, the character and pattern of respirations, and the characteristics of breath sounds are noted and described, especially if they are changing or are a source of discomfort or distress. Monitoring nutritional and fluid intake may be useful in early phases of a life-limiting illness but it is usually contraindicated in the terminal phase. Urinary output and bowel function provide assessment data for renal and gastrointestinal functioning. Again, these may be useful in early phases of care but measuring urinary output is unnecessary in the terminal phase. Monitoring and gently managing bowel function remains important at the end of life as discomfort, even severe pain, due to constipation secondary to analgesic administration is a common problem. Skin condition must be assessed on an ongoing basis because skin becomes fragile and may easily break down.

It is important to be sensitive and not to impose repeated, unnecessary assessments on the dying patient. Health history data that are available in the chart should be used when available rather than tiring the patient with an interview or intrusive physical assessments. However, it is important to assess the patient’s status to ensure comfort.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Several nursing diagnoses dealing with psychosocial manifestations (see Box 9-2) and physical manifestations (see Box 9-3) are associated with palliative care.

BOX 9-2 Psychosocial manifestations at the end of life

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Planning

Planning

Planning for palliative care entails a holistic approach. Coordination of care must focus on both the patient’s needs and the needs of the family members and significant others. Education, counselling, advocacy and support for the patient and family are priorities. Psychosocially, nursing goals centre on the patient’s abilities to express and share feelings with others. Spiritually, nursing care involves creating a ‘space’ in which patients are able to struggle with spiritual questions safely. These may include issues of hope, strength and meaning in the face of life-threatening illness. In some cases spiritual needs may be expressed through religious language. Nursing care goals during the last stages of life involve comfort measures and meeting patients’ physical needs.

Education of both the patient and family is an important part of the nurse’s planning in palliative care. Families need ongoing information on the disease, the dying process and any care that will be provided. They need information on how to cope with many issues during this period of their lives. Denial and grieving may be barriers to learning and understanding at the end of life for both the patient and family members. Nurses must develop a comprehensive plan to support, educate and evaluate patients and families in palliative care issues.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Nursing interventions for the dying patient focus on comfort and improving quality of life. Psychosocial, spiritual and physical care are interrelated for both the dying patient and family members or significant others.

Psychosocial and spiritual care

Psychosocial and spiritual care

Anxiety and depression

Anxiety and depression

Anxiety is an uneasy feeling caused by a source that is not easily identified. Anxiety is frequently related to fear. Patients often exhibit signs of anxiety and depression during the end-of-life period. Causes of depression and anxiety may include pain that is out of control, psychosocial factors related to the disease process or impending death, altered physiological states and high doses of prescribed medication. Encouragement, support and education can decrease some of the anxiety. Management of anxiety may include both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

Fear

Fear

Fear is a typical feeling associated with dying. The nurse frequently assists the dying person to cope with fears. Fears associated with dying include fear of pain and suffering, fear of loneliness and abandonment and fear of meaninglessness.

• Fear of pain and suffering. There is a tendency to associate death with pain. Common sayings such as ‘on pain of death’ or ‘a violent death’ have influenced the way that death is perceived. A dying person who has lost a loved one to a painful death may expect the same type of experience. Subsequently, many people assume that pain always accompanies death. Physiologically, there is no absolute indication that death is always painful. Psychological pain may occur based on the anxieties and separations related to dying. Patients who do experience physical pain should have pain relieving medications available. The patient and family need assurance that medications will be given promptly when needed and that their side effects can and will be managed. Patients can participate in their own pain relief by discussing pain relief measures and their effects. Most patients want their pain relieved without the side effects of grogginess or sleepiness. Pain relief measures such as medications need not deprive the patient of the ability to interact with others.

• Fear of loneliness and abandonment. Many dying people do not want to be alone and fear loneliness. Many dying patients are afraid that loved ones who are unable to cope with their imminent death will abandon them. Dying patients often want someone whom they know and trust to stay with them (see Fig 9-6). It may be a loved one or a caregiver. The simple presence of someone provides support and comfort. Neither words nor actions are necessary unless the patient requires something. Holding hands, touching and listening are considered to be essential nursing responses. Simply providing companionship allows the dying person a sense of security. Importantly, dying people also need some time alone to complete the psychological and spiritual ‘work’ of dying. Spiritual questions may arise at this time and the nurse can assist with identifying the patient’s spiritual needs and implementing spiritual care.

• Fear of meaninglessness. Fear of meaninglessness leads most people to review their lives. They review their intentions during life, examining actions and expressing regrets about what might have been. Life review helps patients to recognise the value that their lives have held. Patients need to look at positive aspects of their lives. Nurses and family members can help patients to review their lives. The worth of the dying person needs to be expressed. The nurse can assist patients and their families in identifying the positive qualities of the patient’s life. The sharing of thoughts and feelings may provide comfort for the patient. The nurse needs to respect and accept the practices and rituals associated with the patient’s life review while remaining non-judgemental.

Communication

Communication

Therapeutic communication is an important nursing intervention used to assist the dying patient and family (see Fig 9-7). Empathy and active listening are essential communication components in palliative care. Empathy is the identification with and understanding of another’s situation, feelings and/or motives. Listening is an active process required in the development of empathy towards another’s feelings.

Patients and families need to be allowed time to express their feelings and thoughts. Making time to listen and interact in a sensitive way enhances the relationship between the nurse, patient and family. Listening is essential. There may be silence. Frequently, silence is related to the overwhelming feelings experienced at the end of life. Silence can also allow time to gather thoughts. Listening to the silence sends a message of acceptance and comfort.

Unusual communication by the patient may take place at the end of life. Frequently, near the end of life, the patient’s communication may become what is often identified as confused, disoriented or garbled. Patients may speak to or about family members or others who have predeceased them, give instructions to those who will survive them or speak of projects yet to be completed.41 Deathbed visions of people who are deceased are also not uncommon. Active, careful listening allows the identification of specific patterns in the dying person’s communication and decreases the risk of inappropriate labelling of behaviours.

Grief

Grief

Goals for facilitating healthy grieving include patient expression of feelings related to grief, acknowledgment of the impending loss and demonstrations of behaviours that reflect progress in grief resolution.

Priority interventions for grief must focus on providing an environment that allows the patient to express feelings. Open discussion of feelings helps both the patient and family work towards resolution of the grief process. The patient should be free to express feelings of anger, fear or guilt without judgement on the part of the nurse. The patient and family need to know that the grief reaction is normal. Respect for the patient’s privacy and need or desire to talk (or not to talk) is important. Honesty in answering questions and giving information is essential. Families and patients need encouragement to continue their usual activities as much as possible. They need to discuss their activities and maintain some control over their lives. At times it helps to discuss what can and cannot change. Assistance with planning for the future or for the funeral may be needed based on the patient’s or family’s coping abilities.

Anger is a common and normal response to grief. It is important to understand that the grieving person cannot be forced to accept the loss. The surviving family members may feel angry at the dying loved one who is leaving them. There is a need to acknowledge and encourage the expression of feelings but at the same time to realise how difficult it is to come to terms with grief. Nurses are sometimes the target of the anger and must understand what is happening and not react on a personal level.

Feelings of hopelessness and powerlessness are common at the end of life. The nurse needs to encourage realistic hope within the limits of the situation. The patient and the family should be allowed to identify and to deal with what is within their control and to recognise what is beyond their control. Patient-identified goals can be encouraged to restore some sense of power. Decision making about care can also foster a sense of power and control for the patient.

Evaluation of the specific coping skills demonstrated and expressed by the patient or the family will assist in planning care. Outcome criteria for goal achievement include verbalisation of specific feelings, expression that the loss is real and identification of specific progress in the grief work. The criteria are evaluated on the basis of specific behaviours and verbalisations exhibited by the patient or the significant others.

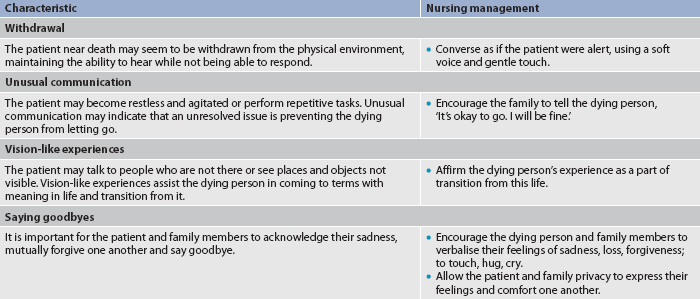

As death approaches, the nurse should encourage the family to respond appropriately to the psychosocial manifestations at the end of life. Table 9-4 outlines the management of psychosocial manifestations near death. People with complicated grief should be referred to a bereavement counsellor or a member of the palliative care team.

Physical care

Physical care

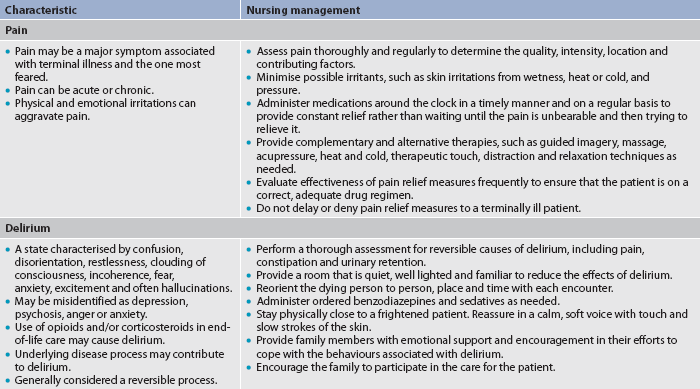

Nursing management related to physical care at the end of life deals with symptom management and caring rather than treatments for curing a particular disease or disorder.41 Meeting the patient’s physiological and safety needs is the priority. Physical care focuses on the needs for oxygen, nutrition, pain relief, mobility, elimination and skin care. People who are dying deserve and require the same physical care as people who are expected to recover. Table 9-5 outlines physical care at the end of life.

After-death care

After-death care

After the patient is pronounced dead, the nurse usually prepares or delegates preparation of the body for immediate viewing by the family with consideration for cultural customs and in accordance with state law, agency policies and procedures. In general, the nurse closes the patient’s eyes (if possible), replaces dentures and washes the body as needed (placing pads under the perineum to absorb urine and faeces), and may remove tubes and dressings. The body should be straightened, leaving the pillow to support the head and prevent pooling of blood and discolouration of the face. The family should be allowed privacy and as much time as they need with the deceased person. In the case of an unexpected or unanticipated death, preparation of the body for viewing or release to a funeral home depends on state law, agency policies and procedures.

Special needs of caregivers in palliative care

SPECIAL NEEDS OF FAMILY CAREGIVERS

The dying process of a loved one can be a long and arduous journey, and being present during this process can be highly stressful. The role of caregiver includes working and communicating with the patient, supporting the patient’s concerns, helping the patient to resolve any unfinished business, working with other family members and friends, and dealing with the caregiver’s own needs and feelings. An understanding of the grieving process as it affects both the patient and family caregivers is of great importance.

Recognising signs and behaviours among family members who may be at risk of abnormal grief reactions is an important nursing intervention. These may include dependency and negative or ambivalent feelings about the dying person, inability to express feelings, concurrent life crises, a history of depression, difficult reactions to previous losses, perceived lack of social or family support, low self-esteem, multiple previous bereavements, alcoholism and/or substance abuse. Family caregivers and other family members need encouragement to continue their usual activities as much as possible. They need to discuss their activities and maintain some control over their lives. At times it helps to discuss what can and cannot change.

Grieving relatives, friends and significant others can provide emotional support for one another. Healthcare providers need to be sensitive to the importance of significant others who are not necessarily relatives. Resources such as community counselling and local support may assist some people in working through their grief. Generally, simply allowing the involved people to express their feelings helps resolve the grief. Caregivers should be encouraged to facilitate the building of a support system of extended family members, friends, faith community, pastoral care and clergy. Caregivers should have access to people whom they can call on at any time to express any feelings they are experiencing. Caregivers and family members should also allow time to be alone.42

Family caregivers need to be encouraged to take care of themselves. Keeping a journal can help the caregiver to express feelings that may be difficult to express verbally. Eating a balanced diet at regular times will provide for the caregiver’s wellbeing. Nourishing the spirit as well as the body is important for the caregiver to consider. Physical contact with others provides emotional support and acknowledgement of the caregiver’s own need for physical comfort. Exercise often relieves stress, and maintaining regular activities and interests is important. The use of humour from time to time in some situations can provide distraction and relieve stress-filled situations.

SPECIAL NEEDS OF NURSES

Many nurses who care for dying patients do so because they are passionate about providing quality palliative care. However, caring for dying patients is intense and emotionally charged. A bond or connection often develops among the patient, family and nurse. Nurses need to be aware of how grief affects them personally. Nurses who are responsible for the care of ill or dying patients are not immune to feelings of loss. It is common for nurses to feel helpless and powerless when dealing with death. Feelings of sorrow, guilt and frustration need to be expressed. Crises and grief result in varying forms of stress for nurses. Palliative care agencies can provide care for their team members with professionally assisted groups, informal discussion sessions and flexible time schedules.

There are also interventions that can help to ease physical and emotional stress for the nurse. The nurse needs to recognise and acknowledge what can and cannot be controlled. Recognising personal feelings allows openness in exchanging feelings with the patient and family. Realising that it is okay to cry with the patient or family during the grief process is essential to the nurse’s wellbeing. Debriefing with a critical friend or healthcare professional may also be helpful.43 Being involved in hobbies and other interests, scheduling time for oneself, maintaining a peer support system and developing a support system beyond the workplace are all of benefit.

Illness and dying are extremely personal events that affect all involved. Providing care for patients and their families at the end of life is a challenging and rewarding experience. Palliative care offers an opportunity to apply the skills and personal commitments that nurses bring to their profession.

1. Ed Garcia is in the terminal stages of bowel cancer. On assessment it is noted that he has rapid, audibly noisy respirations with an associated grunting sound. The correct terminology to use in documenting the assessment data would be to specify that he is experiencing:

2. Sallie Johnson has inoperable pancreatic cancer. Until recently she has been very active in her neighbourhood association. Her husband is concerned because his wife is ‘not herself’. Which common end-of-life psychological manifestation is she demonstrating?

3. Tom has repeatedly asked his mother to donate his deceased father’s belongings to charity but his mother has refused. She sits in the bedroom, crying and talking to her long-dead husband. What type of grief is Tom’s mother experiencing?

4. While Bob Smith is caring for his dying wife, Angie, he states that his wife is a devout Roman Catholic and he is a Baptist. Who is considered the most reliable source for spiritual preferences concerning palliative care for Angie?

5. The family lawyer informed Jim Wilson’s adult children and wife that he did not have an advance directive after he suffered a serious stroke. Who is responsible for identifying palliative care measures to be instituted when patients cannot communicate their specific wishes?

6. The primary purpose of palliative care is to:

7. Alex Alejandro, who has end-stage cardiac disease and is not a candidate for a heart transplant, is medicated with morphine. Recently she has been having chest pain and expressing concern that she may have another heart attack and die in pain. The nurse can decrease the psychosocial impact of physical symptoms of such pain by:

8. When Steve Washington was diagnosed with renal failure, his new wife asked his children from a previous marriage to help with their father’s care. Each of the children refused to help. Rose Washington cared for her husband without help until his death. The behaviours of the children indicate that they may be at risk of abnormal grief reactions related to:

9. Sue Vale has been working full time as a nurse with terminally ill patients for 3 years. She has been experiencing irritability and mixed emotions when expressing sadness since four of her patients died on the same day. To optimise the quality of her nursing care she should examine her own:

1 Puchalski CM. A time for listening and caring. Spirituality and the care of the chronically ill and dying. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

2 Harrington A. Spiritual well-being for older people. In: MacKinlay E, ed. Ageing and spirituality across faiths and cultures. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2010.

3 Hart B, Sainsbury P, Short S. Whose dying? A sociological critique of the ‘good death’. Mortality. 1998;3(1):65–77.

4 Palliative Care Australia (PCA). Palliative care quality resource guide: a toolkit. Canberra: PCA, 2005.

5 Palliative Care Australia (PCA). Standards for providing quality palliative care for all Australians. Canberra: PCA; 2005. Available at www.palliativecare.org.au/Default.aspx?tabid=2016 accessed 10 January 2011.

6 Palliative Care Australia (PCA). A guide to palliative care service development: a population based approach. Canberra: PCA; 2005. Available at www.palliativecare.org.au/Default.aspx?tabid=2016 accessed 10 January 2011.

7 Field M, Cassel C. Approaching death: improving care at the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1997.

8 Ferrell BR, Coyle N. Textbook of palliative nursing, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

9 Kristjanson LJ, Toye C, Dawson S. New dimensions in palliative care: a palliative approach to neurodegenerative diseases and final illness in older people. Med J Aust. 2003;179(6 suppl):S41–S43.

10 Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2387–2392.

11 Department of Health and Ageing (DHA). Guidelines for a palliative approach in residential aged care. Enhanced version. Canberra: Rural Health and Palliative Care Branch, DHA; 2006. Available at www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/ac12to14syn.htm accessed 13 February 2011.

12 American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameters: determining brain death in adults. Available at www.aan.com/professionals/practice/guidelines/pda/Brain_death_adults.pdf. accessed 13 February 2011.

13 Wijdicks EF, Rabinstein AA, Manno EM, et al. Pronouncing brain death: contemporary practice and safety of the apnea test. Neurology. 2008;71:1240.

14 Heran MK, Heran NS, Shemie SD. A review of ancillary tests in evaluating brain death. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35:409.

15 Wallace M. Health care and the law, 3rd edn. Sydney: Lawbook Co., 2001.

16 Metzger PL, Gray MJ. End-of-life communication and adjustment: pre-loss communication as a predictor of bereavement-related outcomes. Death Stud. 2008;32(4):301–325.

17 Kristjanson L, Lobb E, Aoun S, Monterosso L. A systematic review of the literature on complicated grief. Prepared by the WA Centre for Cancer & Palliative Care, Edith Cowan University; 2006. Available at www.caresearch.com.au/caresearch/FindingEvidence/CareSearchReviewCollection/ReviewCollectionGriefLoss/tabid/662/Default.aspx accessed 10 January 2011.

18 Coping with grief and loss. Support for grieving and bereavement. Available at www.helpguide.org/mental/grief_loss.htm. accessed 13 February 2011.

19 Kübler-Ross E. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan, 1969.

20 Martocchio BC. Grief and bereavement. Healing through hurt. Nurs Clin North Am. 1985;20:327–341.

21 Rando TA. Treatment of complicated mourning. Champaign, IL: Research Press, 1993.

22 Stroebe M, Hansson R, Strobe W, Schut H. Handbook of bereavement research: consequences, coping and care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2004.

23 Worden JW. Grief counselling and grief therapy: a handbook for the mental health practitioner, 4th edn. New York: Springer, 2008.

24 Kastenbaum RJ. Death, society, and human experience, 9th edn. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2006.

25 Department of Health and Ageing (DHA). Providing culturally appropriate palliative care to Indigenous Australians. Canberra: Rural Health and Palliative Care Branch, DHA, 2004.

26 Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Medicine. 2003;4:277–294.

27 Giger JN, Davidhizar RE. Transcultural nursing, 5th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2008.

28 Harrington A. Hope rising out of despair: the spiritual journey of patients admitted to a hospice. In: MacKinlay E, ed. Spirituality of later life. On humor and despair. New York: The Haworth Pastoral Press, 2004.

29 Hegarty M. Care of the spirit that transcends religious, ideological and philosophical boundaries. Indian J Palliative Care. 2007;13:42–47.

30 Hospice and Palliative Nurses’ Association. Spiritual distress. Available at www.hpna.org/pdf/TeachingSheet_SpiritualDistress.pdf. accessed 13 February 2011.

31 Highfield ME. Providing spiritual care to patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2000;4:115–120.

32 MacKinlay E. Spiritual growth and care in the fourth age of life. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing, 2006.

33 Spiritual distress in patients: a guideline for health care providers. Available at www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/spirit_assess_long.pdf. accessed 13 February 2011.

34 Roark DC. Overhauling the organ donation system. Am J Nurs. 2000;100:44–48.

35 Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act 1995 (SA). Available at www.legislation.sa.gov.au/lz/c/a/consent%20to%20medical%20treatment%20and%20palliative%20care%20act%201995/current/1995.26.un.pdf. accessed 13 February 2011.

36 Royal College of Nursing Australia. Position statement: the role of the nurse in palliative care. Available at www.rcna.org.au/policy/under_review_cont, 2000. accessed 10 January 2011.

37 Casarett D, Kapo J, Caplan A. Appropriate use of artificial nutrition and hydration. Fundamental principles and recommendations. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(24):2607–2612.

38 Nair B, Kerridge I, Dobson A, et al. Advance care planning in residential care. Aust N Z J Med. 2000;30:339–343.

39 New Zealand Ministry of Health (NZMOH). The New Zealand palliative care strategy. Appendix 1: New Zealand work on palliative care. Wellington: NZMOH; 2001. Available at www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesmh/2951 accessed 10 January 2011.

40 Supporting Australians to live well at the end of life. Draft National Palliative Care Strategy. Available at http://npcsu.communiogroup.com/images/stories/NPCS_2010_Draft_v1.0.pdf, 2010. accessed 10 January 2011.

41 Lynn J, Schuster JL, Kabcenell A. Improving care for the end-of-life. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

42 Lynn J, Harrold J. Handbook for mortals: guidance for people facing serious illness. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

43 Hegarty MM, Breaden KM, Swetenham CM, Grbich C. Learning to work with the ‘unsolvable’. Building capacity for working with refractory suffering. J Palliative Care. 2010;26:287–297.

ACT Palliative Care Society. www.pallcareact.org.au

Asia Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network. www.aphn.org

Australia and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine. www.anzspm.org.au

Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society. www.anzics.com.au

Korero Māori. www.korero.maori.nz

New Zealand Guidelines Group. www.nzgg.org.nz

Palliative Care Association of New South Wales. www.palliativecarensw.org.au

Palliative Care Association of Western Australia. www.palliativecarewa.asn.au

Palliative Care Australia. www.pallcare.org.au

Palliative Care Council of South Australia. www.pallcare.asn.au

Palliative Care Knowledge Network. www.caresearch.com.au/Caresearch/Default.aspx

Palliative Care Nurses Australia. www.pallcare.org.au/Default.aspx?tabid=1262

Palliative Care Queensland. www.palliativecareqld.org.au

Palliative Care Victoria. www.pallcarevic.asn.au

Tasmanian Association for Hospice and Palliative Care. www.tas.palliativecare.org.au