Chapter 26 NURSING MANAGEMENT: upper respiratory tract problems

1. Outline the clinical manifestations and nursing management of problems of the nose.

2. Outline the clinical manifestations and nursing management of diseases and disorders of the paranasal sinuses.

3. Outline the clinical manifestations and nursing management of diseases and disorders of the pharynx and larynx.

4. Discuss the nursing management of the patient who requires a tracheostomy.

5. Identify the steps involved in performing tracheostomy care and suctioning an airway.

6. Describe the risk factors and warning symptoms associated with head and neck cancer.

7. Discuss the nursing management of the patient with a laryngectomy.

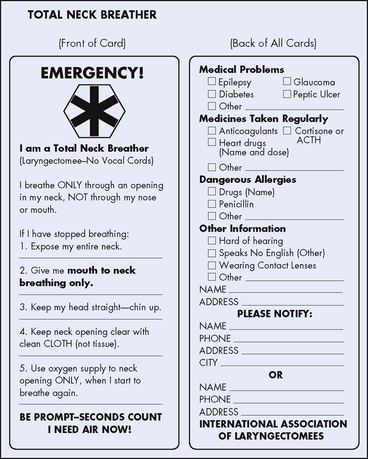

8. Describe the methods used in voice restoration for the patient with temporary or permanent loss of speech.

Deviated nasal septum

Deviated septum is a deflection of the normally straight nasal septum. The top of the cartilaginous ridge of the nose leans to the left or the right, altering air passage. A deviated septum is most commonly caused by trauma or congenital deficit. Symptoms are variable. The patient may acutely experience obstruction of nasal breathing, nasal oedema, dryness of the nasal mucosa with crusting and bleeding (epistaxis). There is conflicting evidence regarding the claim that a severely deviated septum may block drainage of mucus from the sinus cavities, resulting in sinusitis.1 Nasal polyps may also develop at a later stage.

Management of deviated septum includes nasal allergy control as in allergic rhinitis (see p 599). For patients with severe symptoms, a nasal septoplasty is performed to reconstruct and properly align the deviated septum.

Nasal fracture

Nasal fractures are the most common bone injuries in cases of facial trauma.2 They are most often caused by a substantial blow to the middle of the face. Some cases of facial trauma can be prevented by using protective sports equipment and protecting against falls. Complications of the fracture include airway obstruction, epistaxis, meningeal tears, septal haematoma and cosmetic deformity. Nasal fractures are classified as unilateral, bilateral or complex. A unilateral fracture typically produces little or no displacement. Bilateral fractures, the most common fractures, give the nose a flattened look. Powerful frontal blows cause complex fractures, which may also shatter frontal bones. Typically, an assessment reveals deformity of the nose (deviation, misalignment), crepitus, bleeding, ecchymosis and pain. A detailed health history, a history regarding the mechanism of injury and radiological examination are required.

Diagnosis is based on the history and physical examination. Although obvious facial deformity with a nasal fracture is common, often epistaxis may be the only presenting sign. Plain radiographic imaging is rarely indicated when an uncomplicated nasal fracture is suspected. On inspection, the nurse should assess the patient’s ability to breathe through each side of the nose and note the presence of oedema, bleeding or haematoma. There may be ecchymosis under one or both eyes. Ecchymosis involving both eyes is often termed raccoon eyes. If possible, the nose is inspected internally for evidence of septal deviation, haemorrhage or clear drainage, which suggests leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). If clear drainage is observed, a specimen may be sent to the laboratory to determine if it is CSF and, where indicated, referral for neurological assessment. Injury of sufficient force to fracture nasal bones results in considerable swelling of soft tissues. With extensive swelling, it may be difficult to both verify the extent of deformity and repair the fracture until 5–10 days later when the oedema subsides.

The goals of management are to maintain the airway, reduce oedema, prevent complications and provide emotional support. The airway can best be maintained by keeping the patient in an upright position. Ice may be applied to the face and nose to reduce oedema and bleeding. When a fracture is confirmed, the goal of medical management is to realign the fracture using closed or open reduction (septoplasty, rhinoplasty) and assuring that a septal haematoma does not develop, as this increases the patient’s risk for infection. These procedures re-establish cosmetic appearance and proper function of the nose and provide an adequate airway.2,3

Rhinoplasty

Rhinoplasty, a term based on the Greek ‘rhinos’ (nose) and ‘plastikos’ (to shape) is the surgical reconstruction of the nose performed to improve function (reconstruction) or appearance (cosmetic) reasons. A rhinoplasty is indicated when trauma or developmental deformities result in nasal obstruction or cosmetic deficit. Assessment of the patient’s expectations is a critical aspect of preparation prior to rhinoplasty. Any actual or perceived alteration in body image (e.g. a deformed or enlarged nose) can affect self-esteem and interactions with others.3 The patient’s expectations concerning surgical results should be assessed. Computerised photographs made to life-size measurements can be used to simulate appearance after the surgery and may help the patient decide whether to undergo rhinoplasty. Expected results of surgery should be explained frankly and truthfully to avoid disappointment.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Rhinoplasty may be performed as a day procedure or may require an overnight stay in hospital. Improved techniques include the use of fibreoptic endoscopes, which can reduce hospitalisation time. Nasal tissue may be added or removed and the nose may be lengthened or shortened. Implants are sometimes used to reshape the nose. After surgery, nasal packing may be inserted to apply pressure and prevent bleeding or septal haematoma formation. Nasal septal splints (small pieces of plastic or Silastic) may be inserted to help prevent scar tissue formation between the surgical site and lateral nasal wall. An external plastic splint is moulded to fit the new shape of the nose and applied to support the nose. Adhesive surgical strips such as Steri-strips are placed to hold the skin against the septal cartilage. Typically, nasal packing is removed the day after surgery and the splint is removed in 3–5 days.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: NASAL SURGERY

NURSING MANAGEMENT: NASAL SURGERY

Examples of nasal surgery include rhinoplasty, nasoseptoplasty and nasal fracture reduction. Before surgery, the patient should be instructed not to take aspirin-containing drugs or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for 2 weeks to reduce the risk of bleeding. Nursing interventions during the immediate postoperative period include assessment of respiratory status, pain management and observation of the surgical site for haemorrhage and oedema. Education is important because the patient must be able to detect early and late complications at home. Depending on the type and extent of surgery, patients may be advised not to blow their nose for a period. There is an interim period as the oedema and ecchymosis resolve before the final cosmetic effect can be achieved.

Epistaxis

Epistaxis, originating from the Greek for ‘dripping’, is the term for nosebleed. The nose is predisposed to bleeding due to its high vascularity and vulnerable position on the face. Epistaxis may be spontaneous or occur because of trauma and factors that prevent normal clotting, such as drugs (e.g. warfarin, aspirin or any anti-inflammatory) and bleeding disorders. Other predisposing factors include allergies, infection, tumours, alcohol abuse and hypertension. Although conditions such as hypertension do not increase the risk of epistaxis, elevated blood pressure makes bleeding more difficult to control.4

Epistaxis occurs in all age groups, especially in children and older people. Children and young adults have a tendency to develop anterior nasal bleeding, whereas older adults more commonly have posterior nasal bleeding. Anterior bleeding usually stops spontaneously or can be self-treated; posterior bleeding may require medical treatment.4

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: EPISTAXIS

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: EPISTAXIS

Simple first aid measures should be used first to control epistaxis. The nurse should: (1) keep the patient quiet; (2) place the patient in a sitting position, leaning forwards or, if not possible, in a high reclining position so that the head and shoulders are elevated; (3) apply direct pressure by pinching the entire soft lower portion of the nose for 10–15 minutes; (4) apply ice compresses to the nose and have the patient suck on ice; (5) partially insert a small gauze pad into the bleeding nostril and apply digital pressure if bleeding continues; and (6) obtain medical assistance if bleeding does not stop.

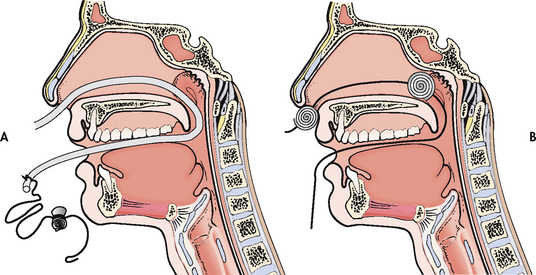

If first aid is not effective, management involves localisation of the bleeding site and application of a vasoconstrictive agent, cauterisation or anterior packing by a healthcare provider. Vasoconstriction can be achieved using small cotton swabs soaked in 1:1000 adrenaline, oxymetazoline or 4% cocaine; these can be wrapped around the tips of a pair of forceps and applied to the bleeding point.5 Anterior packing usually consists of inserting a nasal tampon impregnated with a collagen haemostat and local anaesthetic agent that constricts the bleeding vessels and remains in place for 48–72 hours. The use of diathermy under local anaesthetic, in the emergency department, is becoming more widespread because, if successful, it avoids the complications associated with nasal packing (hypoxia, septicaemia and cardiac arrhythmias) and the cost of admission to hospital.6 Alternatively, inflatable balloons may be used as a nasal pack or gauze rolls may be inserted (see Fig 26-1). Strings attached to the packing are brought to the outside and taped to the cheek for ease of removal. A nasal sling (a folded 50 × 50 mm gauze pad) should be taped over the nostrils to absorb drainage.

Figure 26-1 Method for placing posterior nasal pack. A, The catheter is passed through the bleeding side of the nose and pulled out through the mouth with a haemostat. Strings are tied to the catheter and the pack is pulled up behind the soft palate and into the nasopharynx. B, Nasal pack in position in the posterior nasopharynx. A dental roll at the nose helps maintain correct position.

Nasal packing may alter respiratory status, especially in older adults. Some patients experience hypoventilation (decreasing respiratory rate which increases PaCO2) and hypoxaemia (decrease in PaO2) sufficient to lead to cardiac arrhythmias or respiratory arrest. The nurse should closely monitor respiratory rate, heart rate and rhythm, oxygen saturation (SpO2) and level of consciousness, and observe for signs of bleeding and aspiration. Because of the risk of complications, the patient may be admitted to a monitored unit to permit closer observation.

Packing may be painful because sufficient pressure must be applied to stop the bleeding. Nasal packing predisposes to infection from bacteria normally resident in the nasal cavity (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus). The patient should receive analgesics for pain (e.g. paracetamol with codeine) and be considered for antibiotic prophylaxis. Nasal packing is left in place for a minimum of 3 days. Before removal, the patient should be medicated for pain. After removal, the nostrils may be gently cleaned and lubricated with water-soluble jelly.

Failure of posterior packing to control epistaxis indicates the need for surgery or radiological embolisation of the affected artery. The most common surgical procedure involves ligation of the internal maxillary artery performed through an incision under the upper lip to gain access to the artery.

The patient can be discharged after being taught about home care. The patient should be instructed to avoid vigorous nose blowing, strenuous activity, lifting and straining for 4–6 weeks. The patient should be taught to sneeze with the mouth open and to avoid the use of aspirin-containing products or NSAIDs.

Allergic rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis is the reaction and irritation of the nasal mucosa in response to a specific allergen. Allergic rhinitis is commonly known as hay fever. In the Western world it affects around 20% of the adult population, yet in Australia and New Zealand the prevalence may be as high as 40%. The International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood (ISAAC) described the prevalence and severity of asthma, rhinitis and eczema in children throughout the world and its findings suggest that the prevalence of these respiratory conditions in Australia and New Zealand is among the highest in the world.7

The prevalence of allergic rhinitis is increasing, and its burden is substantial.8 Although the terms ‘seasonal’ and ‘perennial’ are still widely used, the terms ‘intermittent’ and ‘persistent’ are preferred. Intermittent means that the symptoms are present less than 4 days per week or less than 4 weeks per year. Persistent means that the symptoms are present more than 4 days per week and for more than 4 weeks per year. Attacks of seasonal rhinitis usually occur in the spring and autumn and are caused by allergy to pollens from trees, flowers or grasses. The typical attack lasts for several weeks during times when pollen counts are high, disappears and recurs at the same time the following year. Perennial rhinitis is present intermittently or constantly.

Symptoms of allergic rhinitis are usually caused by specific environmental triggers, such as pet hairs, dust mites, moulds or cockroaches, or through living and working in air-conditioned or centrally heated environments. Sensitisation to an allergen occurs with initial allergen exposure, which results in the production of antigen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE). After exposure, mast cells and basophils release histamine, prostaglandins and leukotrienes, which cause the early symptoms of sneezing, itching, rhinorrhoea and moderate congestion. Approximately 2–4 hours after exposure, there is infiltration of inflammatory cells into the nasal tissues, causing and maintaining the inflammatory response.9 Because symptoms of perennial rhinitis resemble those of the common cold, the patient may believe the condition is a continuous or repeated cold.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Manifestations of allergic rhinitis are nasal congestion; sneezing; watery, itchy eyes and nose; altered sense of smell and taste; and thin, watery nasal discharge. The nasal turbinates appear pale, boggy and swollen. The turbinates may fill the air space and press against the nasal septum. The posterior ends of the turbinates can become so enlarged that they obstruct sinus aeration or drainage and result in sinusitis.

With chronic exposure to allergens, the patient’s responses include headache, congestion, pressure, postnasal drip and nasal polyps. The patient may complain of cough, hoarseness or the recurrent need to clear the throat. Congestion may cause snoring.10

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ALLERGIC RHINITIS

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ALLERGIC RHINITIS

Since the range of severity is wide and many sufferers present with severe symptoms, resistance to treatment with usual pharmacotherapy, which includes antihistamines and topical nasal corticosteroids, may occur. For some individuals allergen injection immunotherapy is effective in reducing symptoms and medication requirements.11 Several steps are used in managing allergic rhinitis. The most important step involves identifying and avoiding triggers of allergic reactions (see Box 26-1).

BOX 26-1 How to reduce symptoms of allergic rhinitis

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

Avoidance is the best treatment.

1. Avoid house dust. Use the approach ‘less is best’. Focus on the bedroom. Remove carpeting. Limit furniture. Enclose the pillows, mattress and springs in airtight, vinyl encasements. Limit clothing in the bedroom to items used frequently. Place clothing in airtight, zipper-sealed, vinyl clothes bags. Install an air filter. Close any air-conditioning vents into the room. Use blinds rather than curtains.

2. Avoid house dust mites. Wash bedding in hot water (54°C) weekly. Wear a mask when vacuuming. Double-bag the vacuum cleaner. Install a filter on the outlet port of the vacuum cleaner. Avoid sleeping or lying on upholstered furniture. Remove carpets that are laid on concrete. If possible, have someone else clean the house. Keep house temperature and conditions cool and dry.

3. Avoid mould spores. The three Ds that promote growth of mould spores are darkness, dampness and drafts. Avoid places where humidity is high (e.g. basements, clothes baskets, greenhouses, stables, sheds). Dehumidifiers are rarely helpful. Ventilate closed rooms, open doors and install fans. Consider adding windows to dark rooms. Consider keeping a small light on in wardrobes.

4. Avoid pollens. Stay inside with doors and windows closed during high pollen season. Avoid the use of fans. Install an air-conditioner with a good air filter. Wash filters weekly during high pollen season. Put the car air-conditioner on ‘recirculate’ when driving. Get someone else to tend to your garden. Avoid having plants inside, especially in the bedroom.

5. Avoid pet allergens. Remove pets from the interior of the home. Clean the living area thoroughly. Do not expect instant relief: symptoms usually do not improve significantly for 2 months following pet removal.

6. Avoid smoke. The presence of a smoker will sabotage the best of all possible symptom reduction programs.

The patient should be instructed to keep a diary of times when the allergic reaction occurs and the activities that precipitate the reaction. Steps can then be taken to avoid these triggers.

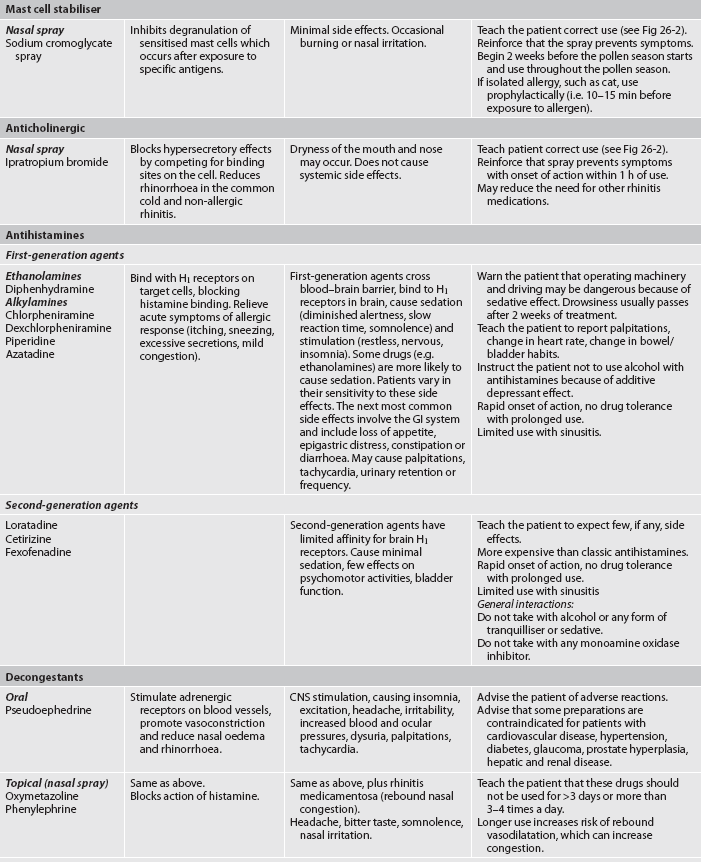

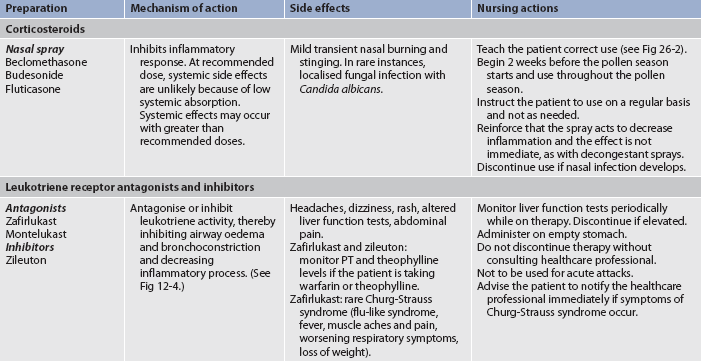

The goal of medication therapy is to reduce inflammation associated with allergic rhinitis and reduce nasal symptoms so that the patient has no adverse effects and can sleep well at night to avoid daytime somnolence.12 This involves the use of antihistamines, intranasal corticosteroids and leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA) to manage symptoms (see Table 26-1). Second-generation (non-sedating) antihistamines are preferred over first-generation antihistamines due to their selectivity and non-sedating effects.

TABLE 26-1 Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis

CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; PT, prothrombin time.

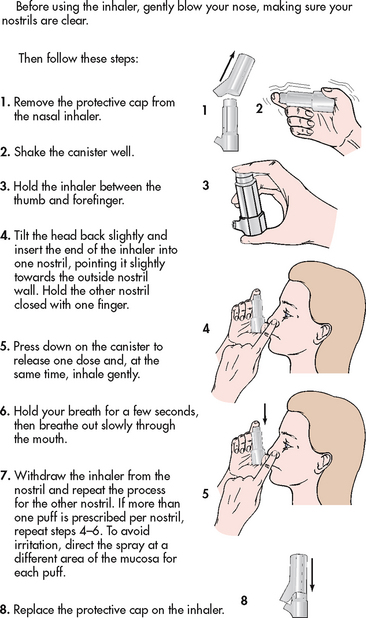

Intranasal corticosteroid or sodium cromoglycate aerosols are effective for seasonal and perennial rhinitis. Nasal corticosteroid sprays are used to decrease inflammation locally with little absorption in the systemic circulation; therefore, systemic side effects are rare. Relief may require combining a nasal corticosteroid spray and an antihistamine. The patient should begin the intranasal corticosteroid 2–3 weeks prior to the allergy season, if possible. Patients using nasal inhalers need careful instruction about proper use (see Fig 26-2). Nasal decongestant sprays can cause a rebound effect from prolonged use.

Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody to IgE that is now in use for the treatment of allergic rhinitis.13 In New Zealand and Australia it is indicated as add-on therapy for adults who have severe allergic asthma. By binding to IgE antibodies, it prevents IgE from attaching to mast cells and thus prevents the release of mediators such as histamine. It blocks the allergic cascade for multiple allergens. (The mechanisms involved in the allergic response are discussed in Ch 13.)

Immunotherapy, which targets a specific antigen, may be used if drugs are not either tolerated or ineffective. Immunotherapy involves controlled exposure to small amounts of a known allergen through frequent (at least weekly) injections, with the goal of decreasing sensitivity.

Acute viral rhinitis

Acute viral rhinitis (common cold or acute coryza) is usually caused by an adenovirus that invades the upper respiratory tract and often accompanies an acute upper respiratory infection (URI). It is the most prevalent infectious disease and is spread by aerosol route emitted from an infected person while breathing, talking, sneezing and coughing or by direct hand contact. This is a major threat to public health internationally because of its ability to both spread and cause epidemics and pandemics of human disease during which incidence of illness and mortality rise dramatically. This virus can survive on inanimate objects for up to 3 days. Frequency of the infection increases in the winter months when people stay indoors and overcrowding is more common. Other factors, such as fatigue, physical and emotional stress and compromised immune status, may increase susceptibility. The patient with acute viral rhinitis typically first experiences tickling, irritation, sneezing or dryness of the nose or nasopharynx, followed by copious nasal secretions, some nasal obstruction, watery eyes, elevated temperature, general malaise and headache. After the early profuse secretions, the nose becomes more obstructed and the discharge is thicker. Within a few days the general symptoms improve, nasal passages reopen and normal breathing is established.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ACUTE VIRAL RHINITIS

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ACUTE VIRAL RHINITIS

Rest, fluids, proper diet, antipyretics and analgesics are recommended. Complications of acute viral rhinitis include pharyngitis, sinusitis, otitis media, tonsillitis and lung infections. Unless symptoms of complications are present, antibiotic therapy is not indicated. Antibiotics have no effect on viruses and, if taken injudiciously, will produce antibiotic-resistant bacteria. If symptoms remain for at least 7 days with no improvement, acute bacterial sinusitis may be present and require treatment with antibiotics.

During the cold season, the patient with a chronic illness or a compromised immune status should be advised to avoid crowded situations and to consider having a flu vaccination. Frequent hand-washing and avoiding hand-to-face contact will help prevent direct spread.

Interventions are directed towards relieving symptoms. The patient should be encouraged to drink increased amounts of fluids to maintain an adequate level of hydration. Antihistamine or decongestant therapy reduces postnasal drip and significantly decreases the severity of cough, nasal obstruction and nasal discharge. The patient should also be taught to recognise the symptoms of secondary bacterial infection, such as a temperature higher than 38°C; purulent nasal exudate; tender, swollen glands; and a sore, red throat. In the patient with pulmonary disease, signs of infection include a change in consistency, colour or volume of the sputum. Because infection can progress rapidly, the patient with chronic respiratory disease may be taught to begin antibiotics for sputum changes, increased shortness of breath and chest tightness.

Influenza

Each year, influenza (flu) causes significant morbidity and mortality rates. In New Zealand, age standardised mortality rates (per 100,000 population) for pneumonia and influenza are 9.9 for the Indigenous population versus 10.3 for the non-Indigenous population.14,15 In Australia, the age standardised mortality rates (per 100,000 population) for pneumonia and influenza are 13.2 for the Indigenous population versus 6.2 for the non-Indigenous population.15,16 In both countries, 3–5 % of deaths each year are influenza-related.14,16 Most deaths occur in people over 60 years of age with underlying heart or lung disease, but could be prevented with vaccination of high-risk groups (see Box 26-2).17

BOX 26-2 Target groups for influenza immunisation

B People under 65 years of age, including children, with:

• cardiovascular disease (ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, rheumatic heart disease, congenital heart disease, cerebrovascular disease)

• chronic respiratory disease (asthma if on regular preventive therapy; other chronic respiratory disease with impaired lung function)

• any cancer, excluding basal and squamous skin cancers if not invasive

• other conditions (autoimmune disease, immune suppression, human immunodeficiency virus), transplant recipients, neuromuscular and central nervous system diseases, haemaglobinopathies, children on long-term aspirin)

Source: www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/influenza-a-h1n1-2010-risk; www.healthinsite.gov.au/topics/Influenza_vaccine.

There are three groups of influenza viruses (A, B and C, although influenza C has little pathogenic potential). In recent years a subtype of influenza A virus, H1N1, has been established in the human population. In 2009 this virus caused around 90% of influenza cases in Australia and New Zealand (for more details, see WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza in the Resources on p 624). Influenza viruses have a remarkable ability to change over time, which accounts for widespread disease and the need for annual vaccination against new strains. Fewer cases of influenza result when a minor change occurs in the virus, because most people have partial immunity.18

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The onset of flu is typically abrupt with systemic symptoms of cough, fever and myalgia often accompanied by a headache and sore throat. Milder symptoms, similar to those of the common cold, may also occur. Physical findings are usually minimal with normal assessment on chest auscultation. Dyspnoea and diffuse crackles are signs of pulmonary complications. In uncomplicated cases, symptoms subside within 7 days. Some patients, particularly older adults, experience weakness or lassitude that persists for weeks. The convalescent phase may be marked by a hyperactive airway and a chronic cough. Important diagnostic factors include the patient’s health history, clinical findings and the presence of other cases of influenza in the community.

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Effects

When taken at the onset of an upper respiratory tract infection, may reduce length and severity of symptoms.

Nursing implications

Echinacea is considered safe when used in recommended doses. May interfere with drugs that suppress the immune system. Caution is advised in patients with conditions affecting the immune system. May lead to liver inflammation. Caution is advised when used with drugs, herbs and supplements that may damage the liver. Unclear evidence related to safety during pregnancy or lactation. Short-term use (10–14 days) is recommended. Should not be taken for more than 8 weeks. Beneficial effects might exist; however, this has not yet been established by independently replicated, rigorous randomised trials.

Source: Ulbricht CE, Basch EM. Natural standard herb and supplement reference. Evidence-Based Clinical Reviews. St Louis: Mosby; 2005. Linde K, Barrett B, Wölkart K et al. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (1):CD000530.

The most common complication of influenza is pneumonia. Patients who develop secondary bacterial pneumonia experience gradual improvement of influenza symptoms, then worsening cough and purulent sputum. Treatment with antibiotics is usually effective if started early.

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Clinical uses

• Heart failure, immunostimulant, infectious diarrhoea, upper respiratory tract infection*

Effects

Commonly used to treat inflamed mucosal tissue. Little scientific evidence is available to determine its effectiveness. Appears safe in recommended doses for short-term use. Commonly combined with echinacea in preparations.

Nursing implications

Should not be used for longer than 2–3 weeks. Use with caution in patients with cardiovascular disease. May increase risk of bleeding. Should not be used concurrently with anticoagulants. Contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation.

Source: Ulbricht CE, Basch EM. Natural standard herb and supplement reference. Evidence-Based Clinical Reviews. St Louis: Mosby; 2005.

*Unclear scientific evidence for its use

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: INFLUENZA

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: INFLUENZA

The nurse should advocate influenza vaccination in high-risk patients during routine surgery visits or, if hospitalised, at the time of discharge (see Box 26-2). The vaccine is 70–90% effective in preventing influenza in adults. To be effective, the vaccine must be given in the autumn before exposure occurs. In Australia and New Zealand, routine vaccination is recommended for older persons and those with chronic disease.17,18 High priority is also given to groups such as healthcare workers who can transmit influenza to high-risk persons. By being vaccinated, healthcare workers can decrease the risk of transmitting influenza to those who have less ability to cope with the effects of this illness. Despite obvious benefits, many people are reluctant to be vaccinated and concerns should be dispelled. Current vaccines are highly purified and reactions are extremely uncommon. Soreness at the injection site is usually the only side effect. The contraindications are a history of Guillain-Barré syndrome and hypersensitivity to eggs because some vaccines are taken from an influenza virus that has been grown in embryonic hens eggs.

The primary goals in management are supportive measures directed towards relief of symptoms and prevention of secondary infection. Unless at high risk or complications develop, the patient with influenza usually requires only symptomatic therapy. Older adults and those with a chronic illness may require hospitalisation. Antivirals can be prescribed for chemoprophylaxis if an influenza outbreak or pandemic occurs. Zanamivir and oseltamivir may be effective against both influenza A and B. These drugs are neuraminidase inhibitors that may prevent the virus from spreading to other cells. For maximum benefit, they should be initiated as soon as possible and ideally within 2 days of the onset of symptoms. They may shorten the course of influenza. Zanamivir is administered using an inhaler. Oseltamivir phosphate is available as an oral capsule. There is some debate regarding the use of both zanamavir and oseltamavir for the reduction of both the symptom duration and severity of influenza.

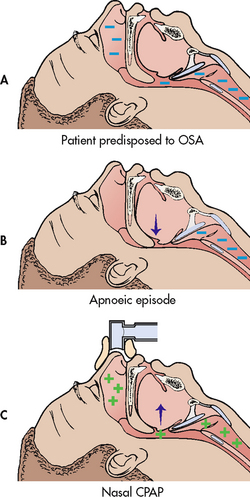

Sinusitis

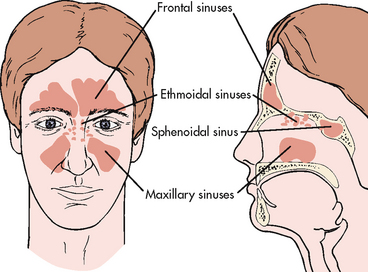

Sinusitis develops when the ostia (exit) from the sinuses is narrowed or blocked by inflammation or hypertrophy (swelling) of the mucosa (see Fig 26-3). The secretions that accumulate behind the obstruction provide a rich medium for growth of bacteria, viruses and fungi, all of which may cause infection. Bacterial sinusitis is most commonly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae or Moraxella catarrhalis.19 Viral sinusitis follows an upper respiratory tract infection in which the virus penetrates the mucous membrane and decreases ciliary transport. Fungal sinusitis is uncommon and is usually seen in patients who are debilitated or immunocompromised.

Acute sinusitis usually results from an upper respiratory tract infection, allergic rhinitis, swimming or dental manipulation, all of which can cause inflammatory changes and retention of secretions. When acute sinusitis follows viral rhinitis, symptoms worsen after 5–7 days and are worse than the original rhinitis. Chronic sinusitis is a persistent infection usually associated with allergies and nasal polyps. Chronic sinusitis generally results from repeated episodes of acute sinusitis that result in irreversible loss of the normal ciliated epithelium lining the sinus cavity.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Acute sinusitis causes significant pain over the affected sinus, purulent nasal drainage, nasal obstruction, congestion, fever and malaise. The patient looks and feels sick. Assessment involves inspection of the nasal mucosa and palpation of the sinus points for pain. Findings that indicate acute sinusitis include a hyperaemic and oedematous mucosa, enlarged turbinates and tenderness over the involved sinuses. The patient may have recurrent headaches that change in intensity with position changes or when secretions drain.

Chronic sinusitis is difficult to diagnose because symptoms may be non-specific. The patient is rarely febrile. Although there may be facial pain, nasal congestion and increased drainage, severe pain and purulent drainage are often absent. Symptoms may mimic those seen with allergies. X-rays of the sinuses or a sinus computed tomography (CT) scan may be performed to confirm the diagnosis. CT scans may show the sinuses to be filled with fluid or the mucous membrane to be thickened. Nasal endoscopy with a flexible scope may be used to examine the sinuses, obtain drainage for culture and restore normal drainage.

Many patients with asthma have sinusitis. The link between these diseases is unclear. Sinusitis may trigger asthma by stimulating reflex bronchospasm. Appropriate treatment of sinusitis often causes a reduction in asthma symptoms.20

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: SINUSITIS

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: SINUSITIS

If allergies are the precipitating cause of sinusitis, the patient needs to be instructed (see Box 26-3) in ways to reduce sinus inflammation and infection, including environmental control of allergies and appropriate drug therapy (see p 599).

BOX 26-3 Acute or chronic sinusitis

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

1. Keep well hydrated by drinking 6–8 glasses of water a day to loosen secretions.

2. Take hot showers twice daily; use a steam inhaler (15-min vaporisation of boiled water), bedside humidifier or nasal saline spray to promote secretion drainage.

3. Report temperature of 38°C, which may indicate infection.

4. Follow prescribed medication regimen:

5. Do not smoke and avoid exposure to smoke. Smoke is an irritant and may worsen symptoms.

6. If allergies predispose to sinusitis, follow instructions regarding environmental control, drug therapy and immunotherapy to reduce the inflammation and prevent sinus infection.

Treatment of acute sinusitis includes antibiotics to treat the infection if it persists longer than 7 days without treatment. Antibiotic therapy, consisting of amoxycillin as the first-line drug of choice, is continued for 10–14 days to prevent the formation of antibiotic-resistant organisms. If symptoms do not resolve, the antibiotic should be changed to a broader-spectrum agent such as sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim or erythromycin. With chronic sinusitis, mixed bacterial flora are often present and infections are difficult to eliminate. Broad-spectrum antibiotics may be used for 4–6 weeks. The use of the following ancillary medications can also relieve symptoms: oral or topical decongestants to promote drainage, nasal corticosteroids to decrease inflammation and antihistamines (see Box 26-3). Patients using topical decongestants must be instructed to use the medication for no longer than 3 days to prevent rebound congestion due to vasodilatation. Classic (first-generation) antihistamines increase the viscosity of mucus and promote continued symptoms, so they should be avoided. Non-sedating (second-generation) antihistamines do not cause this problem, but research does not support their use with infectious sinusitis.21

The patient should be encouraged to increase fluid intake (6–8 glasses daily) and use nasal cleaning techniques. This may include taking a hot shower in the morning and evening followed by blowing the nose thoroughly. Another intervention to cleanse the nasal passages and promote drainage is steam inhalations.

The patient with persistent or recurrent sinus complaints that are not alleviated by medical therapy may require nasal endoscopic surgery to relieve blockage caused by hypertrophy or septal deviation. This is an outpatient procedure usually performed under local anaesthesia.

Polyps

Nasal polyps are mostly benign mucous membrane masses that form slowly in response to repeated inflammation of the sinus or nasal mucosa. Polyps, which appear as bluish, glossy projections in the nares, can exceed the size of a grape. The patient may be anxious, fearing they are malignant. Clinical manifestations include nasal obstruction, nasal discharge (usually clear mucus) and speech distortion. Nasal polyps can be removed endoscopically by laser surgery but recurrence is common. Topical or systemic corticosteroids may slow polyp growth.

Foreign bodies

A variety of foreign bodies may lodge in the upper respiratory tract. Inorganic foreign bodies such as buttons and beads may cause no symptoms, lie undetected and be accidentally discovered on routine examination. Organic foreign bodies such as wood, cotton, beans, peas and paper produce a local inflammatory reaction and nasal discharge, which may become purulent and foul smelling. Foreign bodies should be removed from the nose through the route of entry. Sneezing with the opposite nostril closed may be effective in assisting the removal of foreign bodies. Irrigation of the nose or pushing the object backwards should not be done, because either could cause aspiration and airway obstruction. If sneezing or blowing the nose does not remove the object, the patient should urgently see a healthcare provider.

Acute pharyngitis

Acute pharyngitis is an acute inflammation of the pharyngeal walls. It may include the tonsils, palate and uvula. It can be caused by a viral, bacterial or fungal infection. Viral pharyngitis accounts for approximately 70% of cases. Acute follicular pharyngitis (‘strep throat’) results from beta-haemolytic streptococcal invasion and accounts for an additional 5–15% of episodes in adults.22 Despite the large percentage of cases being viral in aetiology, up to 73% of all patients with pharyngitis are prescribed antibiotics.23 Fungal pharyngitis, especially candidiasis, can develop with prolonged use of antibiotics or inhaled corticosteroids or in immunosuppressed patients, especially those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Symptoms of acute pharyngitis range in severity from complaints of a ‘scratchy throat’ to pain so severe that swallowing is difficult. Both viral and strep infections appear as a red and oedematous pharynx, with or without patchy yellow exudates. Appearance is not always typical. Cultures or a rapid strep antigen test is done to establish the cause and direct appropriate management. Inadequate treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis can result in rheumatic heart disease or glomerulonephritis as a sequel to the infection.

White, irregular patches suggest fungal infection with Candida albicans. In diphtheria, a grey–white false membrane, termed a pseudomembrane, is seen covering the oropharynx, nasopharynx and laryngopharynx and sometimes extends to the trachea.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ACUTE PHARYNGITIS

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ACUTE PHARYNGITIS

The goals of nursing management are infection control, symptom relief and prevention of secondary complications. The patient with proven strep throat is treated with antibiotics. Candida infections are treated with nystatin, an antifungal agent. The preparation should be swished in the mouth as long as possible before it is swallowed and treatment should continue until symptoms are gone. The patient should be encouraged to increase fluid intake. Cool, bland liquids and jelly will not irritate the pharynx; citrus juices can be irritating.

Peritonsillar abscess

Peritonsillar abscess is a complication of acute pharyngitis or acute tonsillitis that occurs when bacterial infection invades one or both tonsils. The tonsils may enlarge sufficiently to threaten airway patency. The patient experiences a high fever, leucocytosis and chills. Intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy is normally required, along with needle aspiration or incision and drainage of the abscess. Occasionally, an emergency tonsillectomy may be performed but more commonly, an elective tonsillectomy may be scheduled after the infection has subsided.

Obstructive sleep apnoea

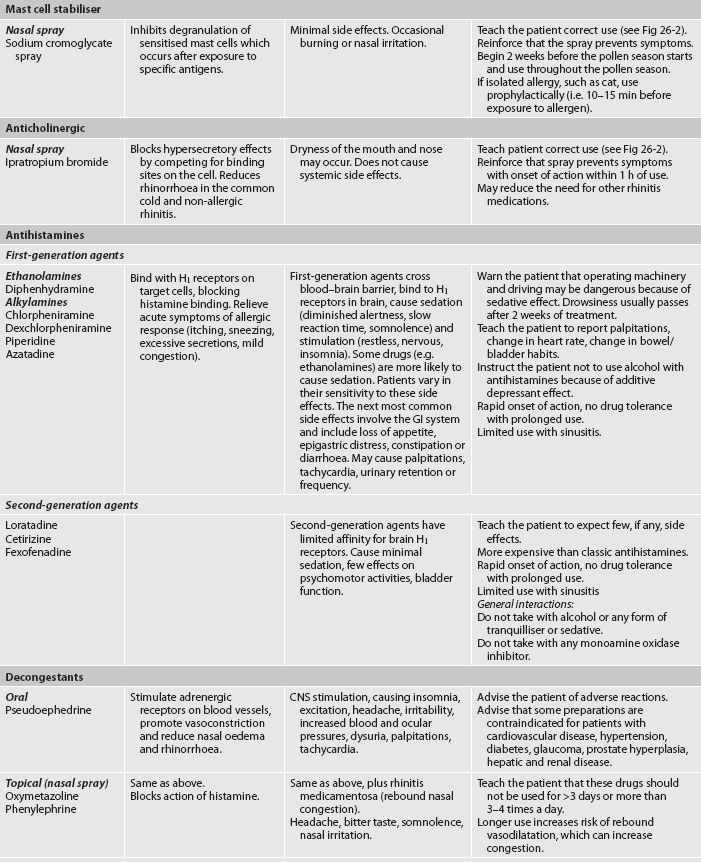

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), also called obstructive sleep apnoea–hypopnoea syndrome (OSAHS), is a condition characterised by partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep, causing apnoea and hypopnoea.24 Apnoea is the cessation of spontaneous respirations for a 10-second period or more. Hypopnoea is abnormally shallow and slow respirations classified as a 10-second event where the ventilation is reduced by at least 50% from baseline. Airflow obstruction occurs when the tongue and the soft palate fall backwards and partially or completely obstruct the pharynx (see Fig 26-4). The obstruction may last from 15 to 90 seconds. During the apnoeic period, the patient experiences severe hypoxaemia (decreased PaO2) and hypercapnia (increased PaCO2). These changes are ventilatory stimulants and cause the patient to awaken partially. The patient has a generalised startle response, snorts and gasps, which causes the tongue and soft palate to move forwards and the airway to open. Apnoea and arousal cycles occur repeatedly, as many as 200–400 times during 6–8 hours of sleep.25 OSA has been recognised as being a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.26

Figure 26-4 How sleep apnoea occurs. A, The patient predisposed to obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) has a small pharyngeal airway. B, During sleep, the pharyngeal muscles relax, allowing the airway to close. Lack of airflow results in repeated apnoeic episodes. C, With nasal continuous positive airway (nCPAP), positive pressure splints the airway open, preventing airflow obstruction.

OSA is a common condition and affects up to 5% of the Australasian population.27 In New Zealand, the prevalence of OSA is estimated to be 4.4% for Māori men, 4.1% for non-Māori men, 2.0% for Māori women and 0.7% for non-Māori women.28 The risk increases with obesity (body mass index [BMI] >28 kg/m2), age greater than 65 years, neck circumference greater than 43 cm and craniofacial abnormalities that affect the upper airway. Obstructive sleep apnoea is more common in men than in women.24

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Clinical manifestations of sleep apnoea include frequent awakening at night, insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness and witnessed apnoeic episodes. The patient’s bed partner may complain about the patient’s loud snoring. The snoring may be so disruptive that both partners cannot sleep in the same room. Other symptoms include morning headaches (from hypercapnia, which causes vasodilation of cerebral blood vessels), personality changes and irritability. Complications that can result from untreated sleep apnoea include hypertension, right heart failure from pulmonary hypertension caused by chronic nocturnal hypoxaemia and cardiac dysrhythmias. Symptoms of sleep apnoea alter many aspects of the patient’s lifestyle. Chronic sleep loss predisposes to diminished ability to concentrate, impaired memory, failure to accomplish daily tasks and interpersonal difficulties. Driving accidents are more common in habitually sleepy persons.29 Family life and the patient’s ability to maintain employment are often compromised. As a result, the patient may experience severe depression. Appropriate referral should be made if problems are identified. Cessation of breathing reported by the bed partner is usually a source of great anxiety because of the fear that breathing may not resume.

Diagnosis of sleep apnoea is made by polysomnography. The patient’s chest and abdominal movement, oral airflow, nasal airflow, SpO2, ocular movement and heart rate and rhythm are monitored. Progression through each sleep stage is determined by monitoring brain waves through electroencephalography (EEG). A diagnosis of sleep apnoea requires documentation of apnoeic events (no airflow with respiratory effort) or hypopnoea (airflow diminished 30–50% with respiratory effort). Generally, more than 10 events an hour with oxygen desaturation below 90% is considered a positive test for OSA. Typically, polysomnography is carried out in a sleep laboratory with sleep technicians monitoring the patient. In some instances, portable sleep studies are conducted in the home setting. Overnight pulse oximetry assessment may be an alternative to determine whether nocturnal oxygen supplementation is indicated.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: SLEEP APNOEA

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: SLEEP APNOEA

Patients with OSA are treated according to the severity of their symptoms.24 Mild sleep apnoea may respond to simple measures. The patient should be instructed to avoid sedatives and alcoholic drinks for 3–4 hours before sleep. Referral to a weight loss program may help because excessive weight exacerbates symptoms. Symptoms resolve in half of the patients with OSA who use an oral appliance during sleep to prevent airflow obstruction. Oral appliances bring the mandible and tongue forwards to enlarge the airway space, thereby preventing airway occlusion. Some individuals find a support group beneficial, where concerns and feelings can be expressed and strategies discussed for resolving problems.

For patients with more severe symptoms, nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) may be used.30 With nCPAP, the patient applies a nasal mask that is attached to a high-flow blower. The blower is adjusted to maintain sufficient positive pressure (5–15 cm H2O) in the airway during inspiration and expiration to prevent airway collapse. Some patients cannot adjust to exhaling against the high pressure and although nCPAP is highly effective, compliance is poor, even if symptoms of sleep apnoea are relieved.1,30 Factors that can influence compliance include ongoing education and follow-up care.

A technologically more sophisticated therapy, bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP), which is capable of delivering a higher pressure during inspiration (when the airway is most likely to be occluded) and a lower pressure during expiration (when the airway is least likely to be occluded), may be helpful and is better tolerated; however, this should be reserved for patients with respiratory failure (see Fig 26-5). Intra-oral devices are appropriate for mild OSA cases or those who cannot tolerate nCPAP; however, their use must be carefully monitored. Drug therapy is contraindicated as a first-line therapy.

Figure 26-5 Management of sleep apnoea often involves sleeping with a nasal mask in place. The pressure supplied by air coming from the compressor opens the oropharynx and nasopharynx. A REMstar Pro with heater humidifier is shown.

Source: Courtesy of Respironics, Inc. and its affiliates.

If other measures fail, sleep apnoea may be managed surgically. The two most common surgical procedures are uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP or UP3) and genioglossal advancement and hyoid myotomy (GAHM). UPPP involves excision of the tonsillar pillars, uvula and posterior soft palate with the goal of removing the obstructing tissue. GAHM involves advancing the attachment of the muscular part of the tongue on the mandible. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty (LAUP) is a surgical procedure than has also been used to treat OSA. Evidence today, however, questions the effectiveness of this type of surgery for people with OSA.31 The patient with enlarged tonsils should be referred to an ear, nose and throat surgeon for surgical consideration. Patients with OSA have increased anaesthetic risk.

Airway obstruction

Any airway obstruction is a potential life-threatening event. Airway obstruction may be complete or partial. Complete airway obstruction is a medical emergency. Partial airway obstruction may occur because of aspiration of food or a foreign body. Partial airway obstruction may result from laryngeal oedema following extubation, laryngeal or tracheal stenosis, central nervous system depression and allergic reactions. Symptoms include: stridor, use of accessory muscles, suprasternal and intercostal retractions, wheezing, restlessness, tachycardia and cyanosis. Prompt assessment and treatment are essential because a partial obstruction may quickly progress to a complete obstruction. First aid interventions to re-establish a patent airway include chest thrusts and back blows.32 Further interventions can include cricothyroidotomy, endotracheal intubation and tracheotomy. Unexplained or recurrent symptoms indicate the need for additional investigations: chest X-ray, bronchoscope and pulmonary function tests.

Tracheostomy

A tracheotomy is a surgical incision into the trachea for the purpose of establishing an airway. A tracheostomy is the stoma (opening) that results from the tracheotomy. Indications for a tracheostomy are to: (1) bypass an upper airway obstruction; (2) facilitate removal of secretions; (3) permit long-term mechanical ventilation; and (4) permit oral intake and speech in the patient who requires long-term mechanical ventilation. Most patients who require mechanical ventilation are initially managed with an endotracheal tube, which can be quickly inserted in an emergency. (Care of the patient with an endotracheal tube is discussed in Ch 65.) Previously, a tracheostomy required surgical dissection and was therefore not typically an emergency procedure. However, a percutaneous tracheostomy, which can be performed emergently at the bedside if necessary, is a valid alternative to a surgically inserted tracheostomy, with reports of less bleeding and fewer postoperative infections.33

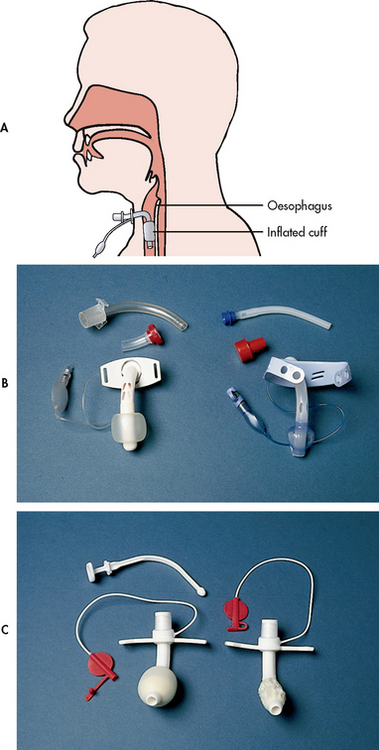

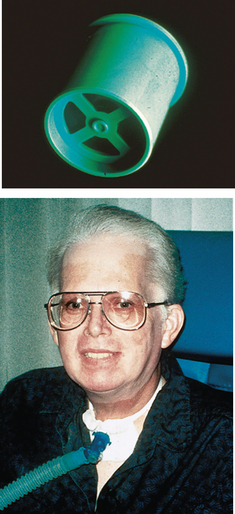

Several advantages make a tracheostomy the better option for long-term care. With tracheostomy there is less risk of long-term damage to the airway, and patient comfort may be increased because there is no tube is present in the mouth. Some patients can eat and talk with a tracheostomy (see Fig 26-6). Because the tracheostomy tube is more secure, patient mobility may be increased.34

Figure 26-6 Types of tracheostomy tubes. A, Tracheostomy tube inserted in airway with inflated cuff. B, Shiley and Portex fenestrated tracheostomy tube with cuff, inner cannula, decannulation plug and pilot balloon. C, Bivona (Fome) tracheostomy tube with foam cuff and obturator (one cuff is deflated on tracheostomy tube). (See Table 26-2 and NCP 26-1 for related nursing management.)

NURSING MANAGEMENT: TRACHEOSTOMY

NURSING MANAGEMENT: TRACHEOSTOMY

Providing tracheostomy care

Providing tracheostomy care

Before the tracheotomy procedure, the purpose of the procedure should be explained to the patient and family. The nurse should also advise that the patient may not be able to speak, depending on the type of tube used.

A variety of tubes is available to meet individual patient needs (see Table 26-2). All tracheostomy tubes contain a face-plate or flange, which rests on the neck between the clavicles and outer cannula. In addition, all tubes have an obturator, which is used when inserting the tube (see Fig 26-6, C). During insertion of the tube, the obturator is placed inside the outer cannula with its rounded tip protruding from the end of the tube to ease insertion. After insertion, the obturator must be removed immediately so that air can flow through the tube. The obturator should be kept in an easily accessible place at the bedside (e.g. taped to the wall) so that it can be used quickly in case of accidental decannulation.35 Some tracheostomy tubes have an inner cannula, which can be removed for cleaning (see Fig 26-6, B). The cleaning procedure removes mucus from the inside of the tube. If humidification is adequate, mucus may not accumulate and a tube without an inner cannula can be used.

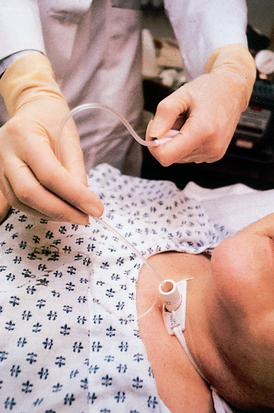

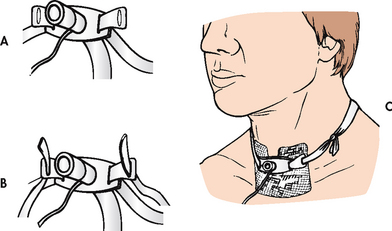

Care of the patient with a tracheostomy involves suctioning the airway to remove secretions35 (see Fig 26-7 and Box 26-4) and cleaning around the stoma. The frequency of suctioning is as determined by direct observation and chest auscultation. In addition, tracheostomy care includes changing tracheostomy ties (see Fig 26-8 and Box 26-5). A two-person technique, one to stabilise the tracheostomy and one to change the ties, is optimal to ensure that the tracheostomy does not become accidentally dislodged during the procedure. If a disposable or non-disposable inner cannula is used, tracheostomy care also involves inner cannula care (see Box 26-5).36

Figure 26-7 Suctioning a tracheostomy. Using aseptic technique, the suction catheter is being withdrawn from the airway while suction is applied. The pilot balloon tubing can be seen lying on the patient’s chest.

BOX 26-4 Procedure for suctioning a tracheostomy tube

1. Assess the need for suctioning 2 hourly. Indications include coarse crackles or rhonchi over large airways, moist cough, an increase in peak inspiratory pressure on mechanical ventilator and restlessness or agitation if accompanied by a decrease in SpO2 or PaO2. Do not suction routinely or if the patient is able to clear secretions with cough.

2. If suctioning is indicated, explain the procedure to the patient.

3. Collect the necessary sterile equipment: suction catheter (no larger than half the lumen of the tracheostomy tube), gloves, water, cup and drape. If a closed tracheal suction system is used, the catheter is enclosed in a plastic sleeve and reused. No additional equipment is needed.

4. Check suction source and regulator. Adjust suction pressure until the dial reads –16 to –20 kPa (−120 to –150 mmHg) pressure with tubing occluded.

5. Assess SpO2, heart rate and rhythm to provide baseline for detecting change during suctioning.

6. Wash hands. Put on goggles and gloves.

7. Use sterile technique to open package, fill cup with water, put on gloves and connect catheter to suction. Designate one hand as contaminated for disconnecting, bagging and operating the suction control. Suction water through the catheter to test the system.

8. Provide preoxygenation by: (1) adjusting the ventilator to deliver 100% O2; (2) using a reservoir-equipped manual resuscitation bag (MRB) connected to 100% O2; or (3) asking the patient to take 3–4 deep breaths while administering O2. The method chosen will depend on the patient’s underlying disease and acuity of illness. The patient who has had a tracheostomy for an extended period of time and is not acutely ill may be able to tolerate suctioning without use of an MRB or the ventilator.

9. Gently insert the catheter without suction to minimise the amount of oxygen removed from the lungs. Insert the catheter the length of the artificial airway. Stop if an obstruction is met.

10. Apply suction intermittently, while withdrawing the catheter in a rotating manner. If secretion volume is large, apply suction continuously.

11. Limit suction time to 10 seconds. Discontinue suctioning if heart rate decreases from baseline by 20 beats/min, increases from baseline by 40 beats/min, an arrhythmia occurs or SpO2 decreases to less than 90%.

12. After each suction pass, assess for preoxygenation with 3–4 breaths by ventilator, MRB or deep breaths with oxygen.

13. Rinse the catheter with sterile water (if in suction kit).

14. Repeat the procedure with a new catheter until the airway is clear. Limit insertions of suction catheter to as few as needed.

15. Return the oxygen concentration to the prior setting.

16. Rinse the catheter and suction the oropharynx or use mouth suction.

17. Dispose of the catheter by wrapping it around the fingers of a gloved hand and pulling the glove over the catheter. Discard equipment in a proper waste container.

18. Auscultate to assess changes in lung sounds. Record time, amount and character of secretions and response to suctioning.

Figure 26-8 Changing tracheostomy ties. A, A slit is cut about 2.5 cm from the end. The slit end is put into the opening of the cannula. B, A loop is made with the other end of the tape. C, The tapes are tied together with a double knot on the side of the neck.

1. Explain the procedure to the patient.

2. Use tracheostomy care kit or collect necessary sterile equipment (e.g. suction catheter, gloves, water, basin, drape, tracheostomy ties, tube brush or pipe cleaners, gauze swabs, sterile water, sodium bicarbonate solution and tracheostomy dressing). Note: Clean rather than sterile technique is used at home.

3. Position the patient in semi-Fowler’s position.

4. Assemble the needed materials on the bedside table next to the patient.

5. Wash hands. Put on goggles and clean gloves.

6. Auscultate chest sounds. If rhonchi or coarse crackles are present, suction the patient if unable to cough up secretions (see Box 26-4). Remove soiled dressing and clean gloves.

7. Open sterile equipment, pour sterile water and hydrogen peroxide in basins and put on sterile gloves.

8. Unlock and remove inner cannula, if present. Many tracheostomy tubes do not have inner cannulae. Care for these tubes includes all steps except for inner cannula care.

9. If a disposable inner cannula is used, replace with a new cannula. If a non-disposable cannula is used:

10. Remove dried secretions from stoma using gauze soaked in sodium bicarbonate solution. Rinse with another gauze swab soaked in sterile water. Gently pat the area around the stoma dry. Be sure to clean under the tracheostomy face-plate, using cotton swabs to reach this area.

11. Maintain the position of the tracheal retention sutures, if present, by taping above and below the stoma.

12. Change the tracheostomy ties. Use the two-person change technique or secure new ties to flanges before removing the old ones. Tie the tracheostomy ties securely with room for one finger between the ties and skin (see Fig 26-8). To prevent accidental tube removal, secure the tracheostomy tube by gently applying pressure to the flange of the tube during the tie changes. Do not change tracheostomy ties for 24 h after the tracheotomy procedure.

13. As an alternative, some patients prefer tracheostomy ties made of Velcro, which are easier to adjust.

14. If drainage is excessive, place dressing around the tube (see Fig 26-8). A tracheostomy dressing or unlined gauze should be used. Do not cut the gauze because threads may be inhaled or may wrap around the tracheostomy tube. Change the dressing frequently. Wet dressings promote infection and stoma irritation.

Both cuffed and uncuffed tracheostomy tubes are available. A tracheostomy tube with an inflated cuff is used if the patient is at risk of aspiration or needs mechanical ventilation. An inflated cuff exerts pressure on tracheal mucosa; it is therefore important to inflate the cuff with the minimum volume of air required to obtain an airway seal. Cuff inflation pressure should not exceed 2.6 kPa (20 mmHg or 25 cm H2O) because higher pressures will compress tracheal capillaries, limiting blood flow and predisposing tracheal necrosis. Cuff pressure measurement devices are manufactured to facilitate pressure checking. An alternative approach, termed the minimal leak technique (MLT), involves inflating the cuff with the minimum amount of air to obtain a seal and then withdrawing 0.1 mL of air. A disadvantage of MLT is the risk of aspiration from secretions leaking around the cuff. MLT should not be used when the tracheostomy was inserted to bypass an upper airway obstruction—for example, in head and neck surgical patients. Some tracheostomy tubes have cuff pressure release valves to minimise the risk of overinflation.

In some patients, cuff deflation may be performed to remove secretions that accumulate above the cuff. Before deflation, the patient should cough up secretions if possible, and the tracheostomy tube and mouth should then be suctioned (see Fig 26-7 and Box 26-4). This prevents secretions from being aspirated during deflation. In addition, the cuff should be deflated during exhalation because the exhaled gas helps propel secretions into the mouth. The patient should cough or be suctioned after cuff deflation. The cuff should be reinflated during inspiration. The volume of air required to inflate the cuff should be monitored daily because this volume may increase if there is tracheal dilation from cuff pressure. The nurse should assess the patient’s ability to protect the airway from aspiration and remain with the patient when the cuff is initially deflated. When the patient can protect their airway from aspiration and does not require mechanical ventilation, an uncuffed tracheostomy tube should be used.

Retention sutures may be placed in the tracheal cartilage when the tracheostomy is performed. The free ends should be taped to the skin in a place and manner that leaves them accessible if the tube is dislodged. Care should be taken not to dislodge the tracheostomy tube during the first few days when the stoma is not mature (healed). Because tube replacement can be difficult, several precautions are required: (1) a replacement tube of equal or smaller size should be kept at the bedside, readily available for emergency reinsertion; (2) tracheostomy tapes should not be changed for at least 24 hours after the insertion procedure; and (3) the first tube change should be performed, usually by a doctor, no sooner than 5–7 days after the tracheostomy.

If the tube is accidentally dislodged, the nurse should immediately attempt to replace it. The retention sutures (if present) are grasped and the opening is spread. A curved haemostat can also be used to spread the opening to facilitate replacing the tube. The obturator is inserted in the replacement tube, lubricated with saline poured over the tip and the tube is inserted in the stoma at a 45° angle to the neck. If insertion is successful, the obturator is removed immediately so that air can flow through the tube. If the tube cannot be replaced, assess the level of respiratory distress. Minor dyspnoea may be alleviated by placing the patient in a semi-Fowler’s position (supine with the head of the bed raised to approximately 30°) and administering oxygen until assistance arrives. Severe dyspnoea may progress to respiratory arrest. If this situation occurs, the stoma should be covered with a sterile dressing and the patient should be ventilated with bag-mask ventilation until help arrives, unless the patient has experienced a total laryngectomy and has complete separation between the upper airway and the trachea.

Initially, tracheostomy patients should receive humidified air to compensate for the loss of the upper airway to warm and moisturise secretions. After the first tube change, the frequency of tube change depends on the type of tube inserted. Tubes with removable inner tubes should be changed approximately once a month, although the inner tube should be cleaned at least 2–3 times each day to prevent obstruction. When a tracheostomy has been in place for several months, the healed tract will be well formed. The patient can then be taught to change the tube using a clean technique at home (see Fig 26-9). Teaching will vary, depending on the patient’s illness and the device selected.

Figure 26-9 Changing the tracheostomy tube at home. When a tracheostomy has been in place for several months, the tract will be well formed. The patient can then be taught to change the tube using a clean technique at home.

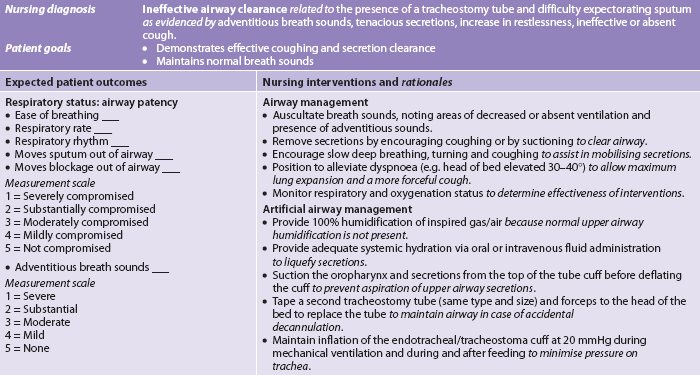

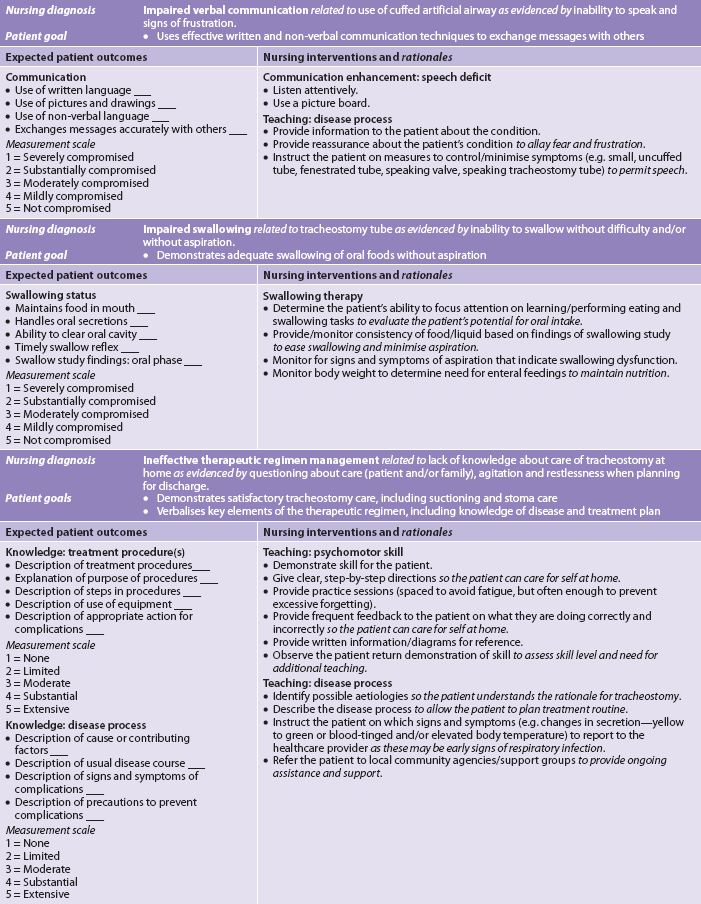

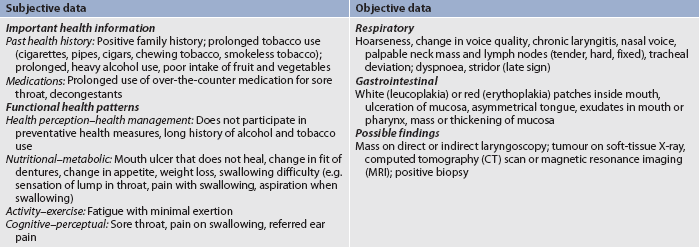

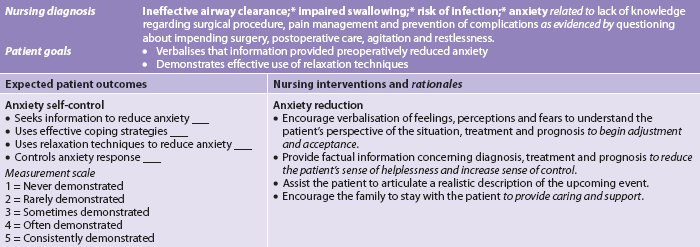

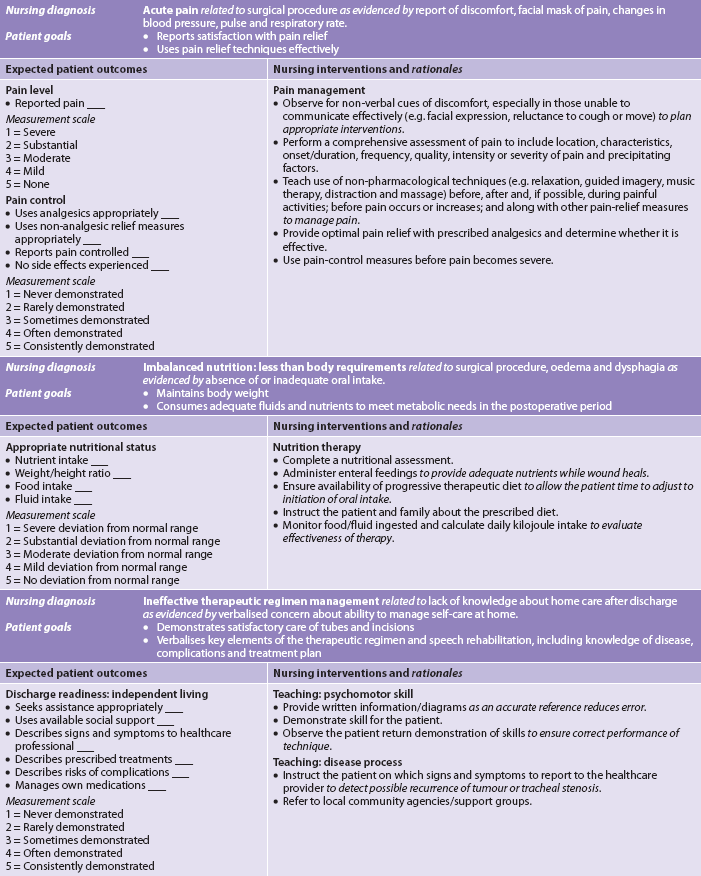

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with a tracheostomy include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 26-1.

Swallowing dysfunction

Swallowing dysfunction

The patient who cannot protect their airway from aspiration requires an inflated cuff. However, an inflated cuff may promote swallowing dysfunction because the cuff interferes with the normal function of the muscles used to swallow. For this reason, it is important to evaluate the risk of aspiration with the cuff deflated. The patient may be able to swallow without aspirating when the cuff is deflated but not when it is inflated. The cuff may then be left deflated or an uncuffed tube substituted (see Fig 26-6).

To evaluate aspiration risk, a formal swallowing evaluation may be done by a speech therapist. Alternatively, the cuff may be deflated and the patient instructed to swallow a small amount of clear liquid, such as grape juice or 30 mL of water that has blue food colouring added. Any coughing and secretions are noted. If needed, the trachea is suctioned to check for the presence of blue-coloured secretions. If there is no indication of aspiration, the patient is judged to have adequate epiglottic function without risk of aspiration.

Speech with a tracheostomy tube

Speech with a tracheostomy tube

A number of techniques enable speech in the patient with a tracheostomy. The spontaneously breathing patient may be able to talk by deflating the cuff, which allows exhaled air to flow upwards over the vocal cords. This can be enhanced by the patient occluding the tube. Frequently, a small uncuffed tube is inserted so that exhaled air can pass freely around the tube. If the patient is on mechanical ventilation, speech may be possible by allowing a constant air leak around the cuff. In addition, some tracheostomy tubes and valves have been designed to facilitate speech. The nurse can be an advocate in promoting use of these specialised devices. Their use can provide great psychological benefit and facilitate self-care for the patient with a tracheostomy.

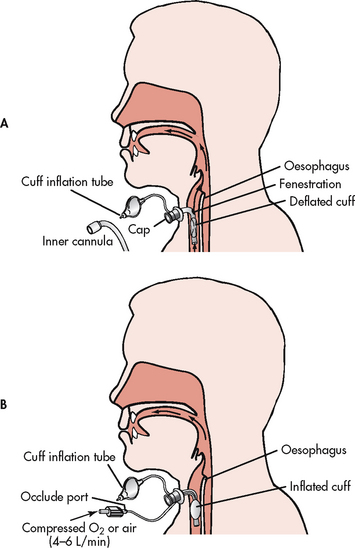

A fenestrated tube has openings on the surface of the outer cannula that permit air from the lungs to flow over the vocal cords (see Fig 26-6, B and Fig 26-10, A). A fenestrated tube allows the patient to breathe spontaneously through the larynx, speak and cough up secretions while the tracheostomy tube remains in place. It can be used by the patient who can swallow without risk of aspiration but requires suctioning for secretion removal. It may also be used by the patient who requires mechanical ventilation for fewer than 24 hours a day (e.g. during sleep).

Figure 26-10 Speaking tracheostomy tubes. A, Fenestrated tracheostomy tube with cuff deflated, inner cannula removed and tracheostomy tube capped to allow air to pass over the vocal cords. B, Speaking tracheostomy tube. One tubing is used for cuff inflation. The second tubing is connected to a source of compressed air or oxygen. When the port on the second tubing is occluded, air flows up over the vocal cords, allowing speech with an inflated cuff. (See Table 26-2 and NCP 26-1 for related nursing management.)

Before the fenestrated tube is used, the patient’s ability to swallow without aspiration is determined (see Table 26-2 and NCP 26-1). If there is no aspiration: (1) the inner cannula is removed; (2) the cuff is deflated; and (3) the decannulation cap is placed in the tube (see Fig 26-10, A). It is important to perform the steps in order because severe respiratory distress may result if the tube is capped before the inner cannula is removed and the cuff deflated. When a fenestrated cannula is first used, the nurse should frequently assess the patient for signs of respiratory distress. If the patient is not able to tolerate the procedure, the cap should be removed, the inner cannula replaced and the cuff reinflated. A disadvantage of fenestrated tubes is the potential for development of tracheal polyps from tracheal tissue granulating into the fenestrated openings.36

A speaking tracheostomy tube has two pigtail tubings. One tubing connects to the cuff and is used for cuff inflation and the second connects to an opening just above the cuff (see Fig 26-10, B). When the second tubing is connected to a low-flow (4–6 L/min) air source, sufficient air moves up over the vocal cords to permit speech. The patient can then speak, although the cuff is inflated.

When a speaking tracheostomy valve is used, an uncuffed tube must be in place or the cuff deflated to allow exhalation (see Fig 26-11). Ability to tolerate cuff deflation without aspiration or respiratory distress must be evaluated in patients using this device. If there is no aspiration, the cuff is deflated and the valve is placed over the tracheostomy tube opening. The speaking valve contains a thin plastic diaphragm that opens on inspiration and closes on expiration. During inspiration, air flows in through the valve. During expiration, the diaphragm prevents exhalation and air flows upwards over the vocal cords and into the mouth.

Figure 26-11 Passy-Muir speaking tracheostomy valve. The valve is placed over the hub of the tracheostomy tube after the cuff is deflated. Two options are available: a white valve for non-ventilated patients and an aqua valve (shown) for ventilated patients. The valve contains a one-way valve that allows air to enter the lungs during inspiration and redirects air upwards over the vocal cords into the mouth during expiration.

If speaking devices are not used, the patient should be provided with paper and pencil or a magic slate. A word (communication) board can usually be obtained from speech therapy or one can be devised with pictures of common needs and an alphabet for spelling words.

Decannulation

Decannulation

When the patient can adequately exchange air and expectorate secretions, the tracheostomy tube can be considered for removal. To decannulate, the nurse needs to explain what will happen to the patient, ensure that suction and oxygen are available, sit the patient in the semi-Fowler’s position, untie the tape securing the tracheostomy, deflate the tube cuff and gently remove the tube from the trachea. The nurse should remain with the patient and observe for signs of respiratory distress. The stoma is cleaned with saline and closed with adhesive tape strips and covered with an occlusive dressing. The dressing must be changed if it gets soiled or wet. The patient should be instructed to splint the stoma with the fingers when coughing, swallowing or speaking.37 Epithelial tissue begins to form in 24–48 hours and the opening will close in several days. Surgical intervention to close the tracheostomy is not usually required.

Laryngeal polyps

Laryngeal polyps are mostly benign mucous membrane masses that form slowly in response to repeated inflammation of the laryngeal mucosa. They may develop on the vocal cords from vocal abuse (e.g. excessive talking, singing) or irritation (e.g. intubation, cigarette smoking). The most common symptom is hoarseness. Polyps may be treated conservatively with voice rest. Surgical removal may be indicated for large polyps, which may cause dyspnoea and stridor. Polyps are usually benign but may be removed because they may later become malignant.

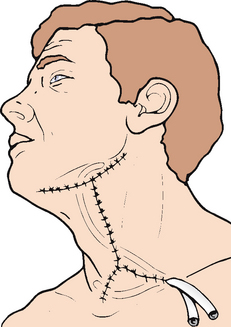

Head and neck cancer

Head and neck cancer arises from mucosal surfaces and is typically squamous cell in origin. This category of tumour includes the paranasal sinuses, the oral cavity and the nasopharynx, oropharynx and larynx. (Cancer of the oral cavity is discussed in Ch 41.) Oral and pharyngeal cancer is not one of the commonly occurring cancers in Australia or New Zealand and ranks as approximately 10th most common by location and associated mortality. The associated disability is great because of the potential loss of voice, disfigurement and social consequences. Most (90%) head and neck cancers occur in individuals 50 years or older after prolonged use of tobacco and alcohol. Other risk factors include consumption of a diet poor in fruits and vegetables and infection by the human papilloma (HPV) virus. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 2:1.38

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Early signs and symptoms of head and neck cancer vary with the tumour location. Cancer of the oral cavity may be a painless growth in the mouth, an ulcer that does not heal or a change in fit of dentures. Pain is a late symptom that may be aggravated by acidic food. Cancers of the oropharynx, hypopharynx and supraglottic larynx rarely produce early symptoms and are usually diagnosed in late stages.39 The patient may complain of persistent unilateral sore throat or otalgia (ear pain). Hoarseness may be a symptom of early laryngeal cancer. If a lump in the neck or hoarseness lasts longer than 2 weeks, a medical evaluation is indicated. Some patients experience what feels like a lump in the throat or a change in voice quality.

Late stages of head and neck cancers have easily detectable signs and symptoms, including pain, dysphasia and decreased mobility of the tongue, airway obstruction and cranial nerve neuropathies. The nurse should thoroughly examine the oral cavity, including the area under the tongue and dentures. The floor of the mouth, tongue and lymph nodes in the neck should be bimanually palpated. There may be thickening of the normally soft and pliable oral mucosa. Leucoplakia (white patch) or erythroplakia (red patch) may be seen and should be noted for later biopsy. Both leucoplakia and carcinoma in situ (localised to a defined area) may precede invasive carcinoma by many years.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

If lesions are suspected, the upper airway may be examined using indirect laryngoscopy, which involves using a laryngeal mirror to visualise the laryngeal area, or a flexible nasopharyngoscope may be used. The larynx and vocal cords are visually inspected for lesions and tissue mobility. A CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be performed to detect local and regional spread. Neoplastic tissue is identifiable because it contains tissue of greater density or because it distorts, displaces or destroys normal anatomical structures. The use of positron emission tomography (PET) scan along with CT has been successful in diagnosing recurring cases of head and neck cancer.40 Typically, multiple biopsy specimens are obtained for cytological examination to determine the extent of the disease.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

The stage of the disease and its management will be determined based on the tumour size (T), the number and location of involved nodes (N) and the extent of metastasis (M). TNM staging classifies disease as stage I to stage IV and guides treatment. Choice of treatment is based on medical history, the extent of the disease, cosmetic considerations, urgency of treatment and patient choice. Approximately one-third of patients with head and neck cancers have highly confined lesions that are stage I or II at diagnosis. Such patients can undergo radiation therapy or surgery with the goal of cure.

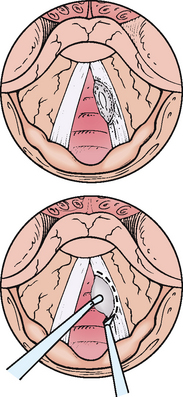

Radiation therapy may be effective in curing early vocal cord lesions. This therapy is usually successful in eliminating the tumour while preserving the quality of the voice. If radiation therapy is not successful or the lesion is too advanced for this therapy, surgery may be performed. A cordectomy (partial removal of one vocal cord) is done when there is a superficial tumour involving one cord (see Fig 26-12). A hemilaryngectomy involves removal of one vocal cord or part of a cord and requires a temporary tracheostomy. A supraglottic laryngectomy involves removing structures above the true cords—the false vocal cords and epiglottis. The patient is left at high risk of aspiration following surgery and requires a temporary tracheostomy. Both hemilaryngectomy and supraglottic laryngectomies allow the voice to be preserved but quality is breathy and hoarse.

Figure 26-12 Excision of laryngeal cancer. This cancer of the right vocal cord meets criteria for resection by transoral cordectomy. The cord is fully mobile and the lesion can be fully exposed. It does not approach or cross the anterior commissure.

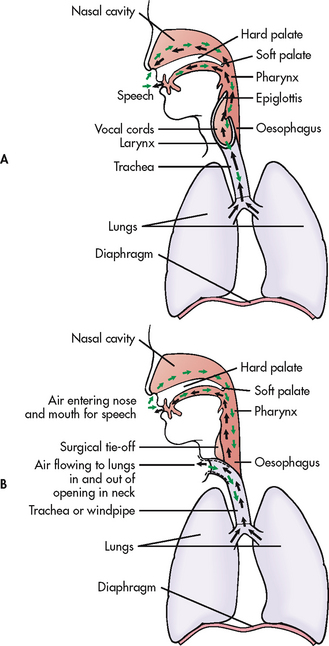

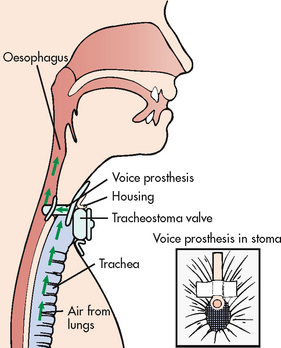

Advanced lesions are treated by a total laryngectomy in which the entire larynx and pre-epiglottic region is removed and a permanent tracheostomy performed. Airflow patterns before and after total laryngectomy are shown in Figure 26-13.

Figure 26-13 A, Normal airflow in and out of the lungs. B, Airflow in and out of the lungs after total laryngectomy. Patients using oesophageal speech trap air in the oesophagus and release it to create sound.

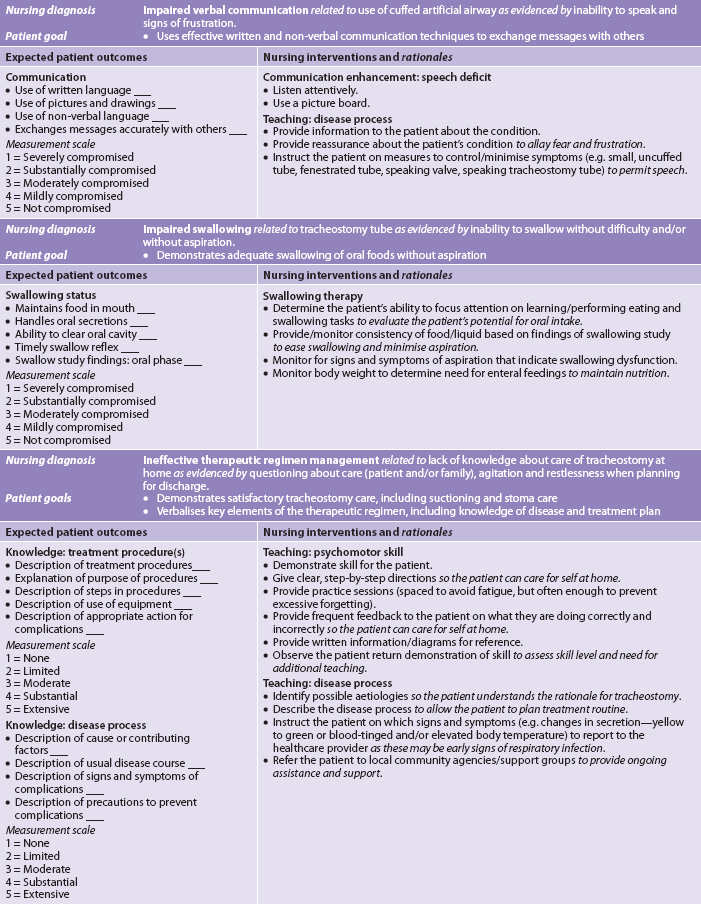

A radical neck dissection frequently accompanies total laryngectomy to decrease the risk of lymphatic spread. Depending on the extent of involvement, extensive dissection and reconstruction may be performed. This procedure involves wide excision of the lymph nodes and their lymphatic channels (see Fig 26-14). The following structures may also be removed or transected: sternocleidomastoid muscle and other closely associated muscles, internal jugular vein, mandible, submaxillary gland, part of the thyroid and parathyroid glands, and the spinal accessory nerve.

A modified neck dissection is performed whenever possible as an alternative to a radical neck dissection. The dissection is modified by sparing as many structures as possible to limit disfigurement and functional loss. A modified neck dissection usually involves dissection of the major cervical lymphatic vessels and lateral cervical space with preservation of nerves and vessels, including the sympathetic and vagus nerves, spinal accessory nerves and internal jugular vein. Neck dissection with vocal cord cancer usually involves one side of the neck. However, if the lesion is midline, a bilateral neck dissection may be performed. When a bilateral neck dissection is performed, it is always modified on at least one side to minimise structural and functional deficits.

The patient may refuse surgical intervention for advanced lesions because of the extent of the procedure or may be judged to be at too great a medical risk to undergo the procedure. In this situation, external radiation therapy may be used as the sole treatment or in combination with chemotherapy.

Brachytherapy, a concentrated and localised method of delivering radiation that involves placing a radioactive source into or near the tumour, may be used to treat head and neck cancer. The goal is to deliver high doses of radiation to the target area while limiting the exposure of surrounding tissues. Thin, hollow, plastic needles are inserted into the tumour area and radioactive iridium seeds are placed in the needles. The seeds emit continuous radiation. Brachytherapy can be used alone or combined with external radiation or surgical intervention. (Radiation therapy and brachytherapy are discussed in Ch 15.)

Nutritional therapy