Chapter 51 NURSING MANAGEMENT: breast disorders

1. Assess breast tissue by inspection and palpation using appropriate examination techniques.

2. Teach breast health awareness, including rationale, technique and reasons for referral.

3. Describe the types, causes, clinical manifestations, multidisciplinary care and nursing management of common benign breast disorders.

4. Identify the known risk factors for breast cancer.

5. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of breast cancer.

6. Explain the indications for different surgical interventions for breast cancer and possible complications following surgical intervention.

7. Analyse the physical and psychological preoperative and postoperative aspects of nursing management for the patient undergoing a mastectomy.

8. Describe the indications for reconstructive breast surgery; types, potential risks and complications of reconstructive breast surgery; and nursing management after reconstructive breast surgery.

Breast disorders are a significant health concern for women. Although most breast problems are of a benign nature, in a woman’s lifetime there is a 1 in 8 chance in Australia and a 1 in 9 chance in New Zealand that she will be diagnosed with breast cancer.1,2 Whether benign or malignant, intense feelings of shock, fear and denial often accompany the initial discovery of a lump or change in the breast. These feelings can be associated with both the fear of death and the possible loss of a breast. In many cultures and throughout history, the female breast has been regarded as a symbol of beauty, femininity, sexuality and motherhood. The potential loss of a breast, or part of a breast, may be devastating for many women because of the associated significant psychological, social, sexual and body image implications. The most frequently encountered breast disorders in women are fibrocystic changes, fibroadenoma, intraductal papilloma, ductal ectasia and breast cancer. In men, gynaecomastia is the most common breast disorder. Table 51-1 outlines the risk factors for breast cancer.

TABLE 51-1 Risk factors for breast cancer

| Increased risk | Comments |

|---|---|

| Female | Women account for 99% of breast cancer cases. |

| Age 50 or over | The majority of breast cancers are found in postmenopausal women. |

| Family history | Breast cancer in a first-degree relative, particularly when premenopausal or bilateral, increases risk. Gene mutations (BRCA1 or BRCA2) play a role in 5–10% of breast cancer cases. |

| Personal history of breast cancer, colon cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer | Personal history significantly increases the risk of breast cancer, the risk of cancer in the other breast and recurrence. |

| Early menarche (age <12); late menopause (age >55) | A long menstrual history increases the risk of breast cancer. |

| First full-term pregnancy after age 30; nulliparity | Prolonged exposure to unopposed oestrogen increases the risk of breast cancer. |

| Benign breast disease with atypical epithelial hyperplasia | Atypical changes in breast biopsy increase the risk of breast cancer. |

| Obesity after menopause | Fat cells store oestrogen. |

| Exposure to ionising radiation | Radiation damages DNA (e.g. prior treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma). |

Assessment of breast disorders

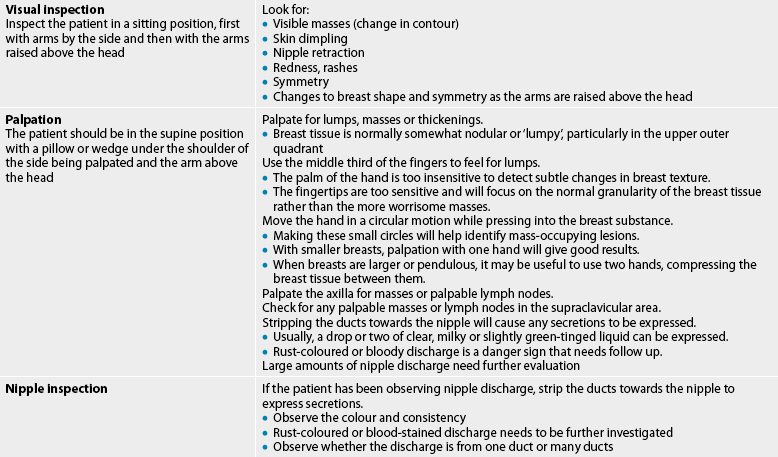

It is critical that breast disorders be detected early, diagnosed accurately and treated promptly. Early detection of breast cancer is associated with increased survival, increased treatment options and improved quality of life. The factors contributing to the early detection of breast cancer and other breast-related problems are breast awareness, screening mammography and clinical breast examination (CBE; see Table 51-2).3–5 The frequency of CBE is determined by the woman’s age, the presence of significant risk factors (see Table 51-1) and her past medical history. CBE offers most benefit to women who are not participating in regular mammographic screening.

Guidelines established in Australia and New Zealand by BreastScreen Australia3 and the Cancer Society of New Zealand4 about breast surveillance practices (their programs are recognised as among the most comprehensive population-based screening programs in the world) include the following:

1. breast awareness, where all women should be aware of how their breast normally feels and looks and report new or unusual changes promptly to their general practitioner

2. screening mammography in line with recommendations

3. CBE by a trained health professional for symptomatic women, for women with a previous history of breast cancer, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and for women who are not having screening mammograms.

National screening programs are available in New Zealand and Australia (see below). The benefits of early detection of breast cancer are well established and the use of screening mammography has significantly improved early and accurate detection of breast malignancies, contributing in part to lower mortality rates.

BREAST EXAMINATION

The health professional conducting CBE (see Table 51-2) is in an ideal position to teach women about their breasts and encourage them to develop skills of breast self-awareness (BSA). The Cancer Society of New Zealand and the National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre of Australia emphasise the importance of breast self-awareness, along with regular screening by mammography and CBE. While there is no ‘correct’ way for a woman to examine her breasts, women should regularly look and feel for breast changes. This should be done while washing or dressing, so that the woman becomes familiar with her breasts and how they change at different times of the month and with age. Women are advised to know what is normal for them, to know what changes to look and feel for, and to report changes without delay. Changes in the breast that should be reported include a persistent new lump or thickening, change in breast size or shape, puckering or dimpling of the skin, changes to one nipple only (such as discharge or inversion), lumpiness in one breast at the end of the menstrual cycle and pain in the breast that is unusual. If a problem is suspected, such as nipple discharge or finding a lump, the woman should see her healthcare provider or contact a comprehensive breast centre as soon as possible so that additional diagnostic studies can be promptly initiated. If the problem is not serious, the woman’s anxiety can be quickly relieved. If a serious problem is suspected or diagnosed, definitive treatment should not be delayed.

Even when a woman practises BSA, she should follow national guidelines for screening mammography. Mammography can identify breast abnormalities that may be cancer before physical symptoms appear. In Australia free screening is offered to women between the ages of 50 and 69 years and in New Zealand it is offered to women between the ages of 45 and 69 years. In Australia, free second-yearly mammograms are also available to the 40–49-year-old age group and are recommended for women with a strong family history of breast cancer, a previous ‘at-risk’ lesion on biopsy or previous breast cancer; women over 70 are also eligible for free breast screening on demand. In New Zealand, however, women aged younger than 45 and older than 70 are not eligible for the free screening program; they need to discuss their individual needs with their healthcare practitioner.6 Women at high risk of breast cancer, such as those with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, should consult their healthcare provider about the optimal age to commence having mammograms and the screening frequency.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

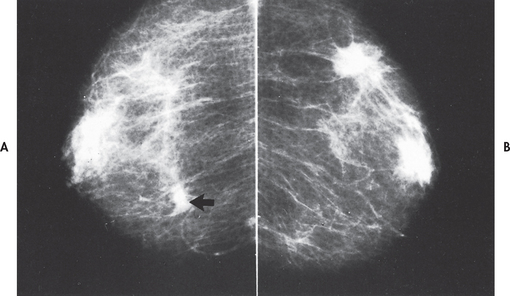

Several techniques can be used to screen for breast disease or provide a diagnosis of a suspicious physical finding. Mammography is used to visualise the internal structure of the breast using low-dose X-rays (see Fig 51-1). This simple, safe procedure can detect tumours and cysts that cannot be felt by palpation and assist in definitive diagnosis of palpable lumps. Improved imaging techniques have reduced the radiation that accompanies mammography.

Figure 51-1 Mammogram showing bilateral invasive ductal carcinoma. A, The larger left mass was palpable. B, The smaller right mass was not palpable.

Calcifications are the most easily recognised mammogram abnormality. These deposits of calcium crystals form in the breast for many reasons, such as inflammation, trauma and ageing. Although most calcifications are benign, they may be associated with invasive or preinvasive cancer.7

Mammography can detect around 85% of breast cancers.6 Some tumours metastasise late in the preclinical course: early detection by mammography allows early treatment, reducing the risk of metastasis of these smaller lesions. A comparison of current and prior mammograms may show early cancer tissue changes. As some breast cancers are not detected on mammography, women should be made aware of the importance of breast self-awareness.

Tumours detectable by physical examination are generally 1 cm or larger. It may take 10 years or longer for a tumour to grow to this size. When a mass or thickening is detected, mammography should be performed to measure the extent of the primary tumour in the affected breast and to detect cancer in the contralateral breast. Suspicious masses should be biopsied even if mammogram findings are unremarkable. In younger women, mammography is less sensitive because of the greater density of breast tissue: ultrasound is recommended as the primary investigation in women younger than 35 years of age.8

Breast ultrasound is a diagnostic procedure that can be used to differentiate a benign tumour from a malignant tumour, and is also useful in the assessment of tumour size. It is particularly useful in women with fibrocystic changes whose breast tissue is very dense. However, ultrasound does not easily detect microcalcifications. Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used for the detection of breast cancer in high-risk women under the age of 50 years.9 Despite recent promotion of thermal imaging as an alternative to mammography, there is no current scientific evidence to support the use of breast thermal imaging for early diagnosis of breast cancer.10

A definitive diagnosis of a suspicious area is made by means of the histological examination of biopsied tissue. Biopsy techniques include fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, core biopsy and open biopsy.

FNA biopsy is performed by inserting a needle into the lesion and aspirating tissue into a syringe; guided by either mammography or breast ultrasound in the case of an impalpable lesion, FNA and cytological evaluation may be helpful in making a diagnosis and planning treatment. It should be done only if an experienced cytologist is available. All suspicious lesions, even if the result is negative, should be followed with a more definitive biopsy procedure (described below). If the aspirated specimen is positive for malignancy, the patient can be given this information at the same visit and begin learning about the treatment options.

Core biopsy is a reliable diagnostic technique for obtaining the histology of an abnormality. As with FNA, mammography or ultrasound is used to locate the impalpable lesion. A wide-bore needle is used to remove a core sample of the lesion. If the lesion is palpable, core tracks can be placed in such a way as to enable surgical excision of the track. This technique has several advantages over an open biopsy, including minimal scarring, the use of local anaesthesia, outpatient procedure, reduced cost and shorter recovery time.

Open biopsy may be indicated if less invasive techniques do not provide definitive diagnosis. Open biopsy is generally performed under general anaesthetic and patients with impalpable lesions will need to undergo a preoperative localisation procedure. Under local anaesthetic, and using mammogram or ultrasound guidance, a hook-wire is inserted into the region of abnormality, to allow the surgeon to identify and excise the appropriate area.

Mastalgia

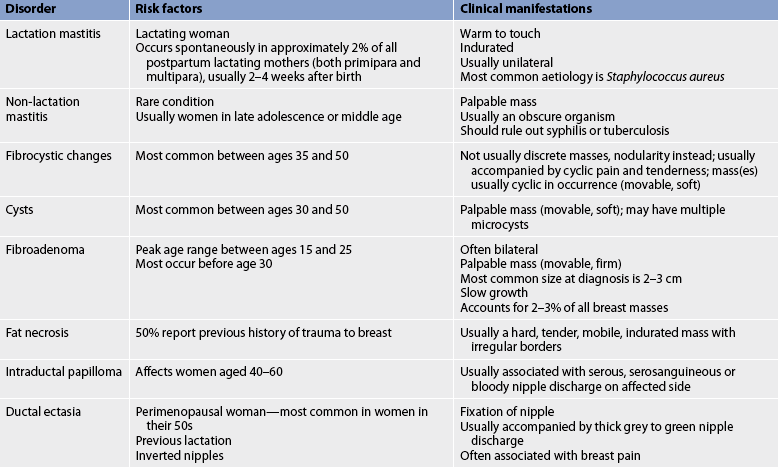

Mastalgia (breast pain) is the most common breast-related complaint in women.11 True breast pain needs to be differentiated from referred chest wall (musculoskeletal pain). The most common form of true mastalgia is cyclic mastalgia, which coincides with the menstrual cycle. It is described as diffuse breast tenderness or heaviness. Breast pain may last 2–3 days or most of the month. The aetiology of the pain is uncertain but is thought to be related to hormonal changes in breast tissue. The symptoms often decrease with menopause. Non-cyclic mastalgia has no relationship to the menstrual cycle and can continue into menopause.11 It may be constant or intermittent throughout the month and last for several years. Symptoms include burning, aching or soreness in the breast. The aetiology of non-cyclical pain may be due to trauma, fat necrosis or duct ectasia. Table 51-3 outlines the different benign disorders of the breast.

Mammography is frequently done to exclude cancer, provide information on the aetiology of mastalgia and reassure women about the benign nature of the condition. Some relief may occur with reducing dietary fat, taking gamma-linolenic acid (evening primrose oil) and the continual wearing of a support bra. Hormonal therapy may be recommended, including oral contraceptives and danazol. While some centres recommend reducing caffeine intake, the evidence is anecdotal and is as yet unproven. The use of vitamins E, A and B complex is controversial and patients should discuss use of vitamins and herbal preparations with their medical practitioner.12

Breast infections

MASTITIS

Mastitis is an inflammatory condition of the breast that occurs most frequently in lactating women. Lactational mastitis manifests as a localised area that is erythematous, painful and tender to palpation. Fever is usually present. The infection develops when organisms, usually staphylococci, gain access to the breast through a cracked nipple. In its early stages, mastitis can be cured with antibiotics. Breastfeeding should continue unless an abscess is forming or a purulent drainage is noted. The mother may wish to use a nipple shield or to hand-express milk from the involved breast until the pain subsides. She should see her doctor promptly to begin a course of antibiotic therapy. Any breast that remains red, tender and not responsive to antibiotics requires follow-up care and evaluation for inflammatory breast cancer.

LACTATIONAL BREAST ABSCESS

If lactational mastitis persists after several days of antibiotic therapy, a lactational breast abscess may have developed. In this condition the skin may become red and oedematous over the involved breast, often with a corresponding palpable mass, and the patient may have an elevated temperature. Antibiotics alone constitute insufficient treatment for a breast abscess. Surgical incision and drainage may be necessary. The drainage is cultured, sensitivities are obtained and therapy with an appropriate antibiotic is begun. Often the woman will find it necessary to express and discard milk from the affected breast until the abscess is resolved. Breastfeeding should not be discontinued as this is the most effective means of emptying the breast.

Fibrocystic changes

Fibrocystic changes in the breast constitute benign conditions characterised by changes in breast tissue (see Table 51-3). The changes include the development of excess fibrous tissue, hyperplasia of the epithelial lining of the mammary ducts, proliferation of mammary ducts and cyst formation. The use of the term fibrocystic disease is incorrect because the cluster of problems is actually an exaggerated response of breast tissue to hormonal influences. It has been suggested that the terms fibrocystic condition or fibrocystic complex be used. Fibrocystic changes are in general benign, although some changes can be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Masses or nodularity can appear in both breasts and are often found in the upper, outer quadrants and usually occur bilaterally. Fibrocystic changes are the most frequently occurring breast disorder.

Manifestations of fibrocystic breast changes include palpable lumps that are usually round, well delineated and freely movable within the breast. Some lumps are fibrous and do not contain cysts. There may be accompanying discomfort ranging from tenderness to pain. The lump is usually observed to increase in size and perhaps in tenderness before menstruation. Cysts may enlarge or shrink rapidly. Nipple discharge associated with fibrocystic breasts is often milky, watery-milky or green.

Fibrocystic changes occur most frequently in women between 35 and 50 years of age but may begin in women as young as 20 years of age. Pain and nodularity often increase over time but tend to subside after menopause unless high doses of oestrogen replacement are used. The cause of these fibrocystic changes is thought to be due to heightened responsiveness of breast parenchyma and stroma to circulating oestrogen and progesterone. There is little evidence about significant risk factors for fibrocystic breast changes. Symptoms related to fibrocystic changes often worsen in the premenstrual phase and subside after menstruation.

Mammography may be helpful in distinguishing fibrocystic changes from breast cancer and in identifying the proliferative breast conditions that place women at higher risk of breast cancer, and women should be advised of their increased risk and the importance of regular mammographic surveillance.13 However, in some women the breast tissue is so dense that it is difficult to obtain a worthwhile mammogram study. In these situations, ultrasound may be useful.

It must be remembered that Indigenous women and those born in non-English speaking countries may need extra support from nurses if they are to be encouraged to attend screening clinics or to report breast changes.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: FIBROCYSTIC CHANGES

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: FIBROCYSTIC CHANGES

With the initial discovery of a discrete mass in the breast by a woman or her healthcare provider, breast imaging, cyst aspiration or surgical biopsy may be indicated. When the problem is thickening or nodularity in the absence of a discreet lump, it is appropriate to wait to note changes as the menstrual cycle changes. In the presence of a discreet mass, FNA may be performed, with core biopsy or excisional biopsy undertaken if no fluid is found on aspiration, if the fluid that is found is haemorrhagic or if a residual mass remains after aspiration. These patients should be referred to a breast surgeon for further management. With large or recurrent cysts, surgical removal may be considered. Excision is performed in a day surgery unit with the patient under local or general anaesthesia.

Biopsies in women with fibrocystic changes may be indicated for those with an increased risk of breast cancer (see Table 51-1). Hyperplastic changes approximating the histological appearance of carcinoma in situ (atypical hyperplasia) and a family history of breast cancer increase the probability of developing breast cancer.

The woman with fibrocystic changes should be encouraged to be breast self-aware and to return regularly for follow-up examinations and routine mammographic screening throughout her life. Severe fibrocystic changes may make palpation of the breast more difficult. Any new lumps or changes in the breasts should be evaluated, and changes in symptoms should be reported and investigated.

Many types of treatment have been suggested for a fibrocystic condition. These include the use of a good support bra, dietary therapy (low-salt diet, restriction of methylxanthines such as coffee and chocolate), vitamin E therapy, analgesics, danazol, diuretics, hormone therapy and antioestrogen therapy.12,13 Although many of these treatments have not been scientifically proven to be beneficial, numerous women report less discomfort with these non-surgical measures. Danazol has been used for patients with severe pain. It decreases follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH), resulting in reduced oestrogen production and subsequent decreased pain and nodularity. However, the androgenic side effects of danazol (acne, oedema, hirsutism) often make this therapy intolerable for many women.

The role of the nurse in the care of the patient with fibrocystic breast changes is primarily one of teaching and empowering. A woman with fibrocystic breasts should be told that she may expect recurrence of the cysts in one or both breasts until menopause and those cysts may enlarge or become painful just before menstruation. Additionally, she should be reassured that cysts do not ‘turn into’ cancer. She should be advised that any new lump that does not respond in a cyclical manner over 1–2 weeks should be investigated promptly by a healthcare provider.

Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenoma is a common cause of discrete benign breast lumps in young women. It generally occurs in women between 15 and 25 years of age and is the most frequent cause of breast masses in women under 25 although they can appear at any age. The possible cause of fibroadenoma may be increased oestrogen sensitivity in a localised area of the breast. Fibroadenomas are usually small, round, well delineated and very mobile. They may be soft but are usually solid, firm and rubbery in consistency. There is no accompanying retraction or nipple discharge. The lump is often painless. The fibroadenoma may appear as a single unilateral mass, although multiple bilateral fibroadenomas have been reported. Growth is slow and often ceases when size reaches 2–3 cm. Size is not affected by menstruation. However, pregnancy can stimulate dramatic growth. Fibroadenomas are rarely associated with cancer.

Phyllodes tumours (sometimes called giant fibroadenomas) are rare tumours of the breast stroma that are usually benign, but may be malignant.14 Management is by local excision of the tumour.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: FIBROADENOMA

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: FIBROADENOMA

Fibroadenomas are easily detected by physical examination and are often visible on mammography. Definitive diagnosis, however, requires biopsy and tissue examination by a pathologist. Treatment of fibroadenomas can include surgical excision, which is not urgent in women under 25 years of age. In women over 35 years of age all new lesions should be investigated using the ‘triple-test’ guidelines.15 (The ‘triple test’ refers to three diagnostic components: medical history and clinical breast examination; mammography and/or ultrasound; and fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology and/or core biopsy. The sensitivity of the ‘triple test’ is greater than any of the individual components alone.) Fibroadenomas are not reduced by radiation and are not affected by hormone therapy.

As an alternative to surgery, tumour removal can be accomplished using cryoablation. In this procedure a cryoprobe is inserted into the tumour using ultrasound guidance. Extremely cold gas is piped into the tumour. The frozen tumour dies and gradually shrinks.

The nurse frequently has the opportunity to counsel young women with fibroadenomas. During this contact the benign nature of the lesion should be stressed and follow-up examinations and breast self-awareness should be encouraged.

Nipple discharge

Nipple discharge may occur spontaneously or as a result of nipple manipulation. A milky secretion is due to inappropriate lactation (termed galactorrhoea) as a result of such problems as drug therapy, endocrine problems and neurological disorders. Nipple discharge may also be idiopathic.

Secretions can also be serous, grossly bloody or brown to green. These may be caused by either benign or malignant disease. Cytology investigation can be undertaken on the secretion to detect specific disease. Diseases associated with nipple discharge include malignancies, cystic disease, intraductal papilloma and ductal ectasia. Treatment depends on identification of the cause. In most cases, nipple discharge is not related to malignancy. If galactorrhoea is accompanied by amenorrhoea, various gynaecological endocrinopathies should be explored.

INTRADUCTAL PAPILLOMA

An intraductal papilloma is a benign, wart-like growth found in the mammary ducts, usually near the nipple. Typically, there is an associated bloody nipple discharge or a mass, or both. Intraductal papillomas usually affect women 40–60 years of age. A single duct or several ducts may be involved. Treatment includes excision of the papilloma and the involved duct.

DUCTAL ECTASIA

Ductal ectasia is a benign breast disease of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women involving the ducts in the subareolar area. It usually involves several bilateral ducts. Nipple discharge is the primary symptom. This discharge can be grey to green and sticky. Ductal ectasia is initially painless but may progress to burning, itching and pain around the nipple, as well as swelling in the areolar area. Inflammatory signs are often present, the nipple may retract and the discharge may become bloody in more advanced disease. Ductal ectasia is not associated with malignancy. If an abscess develops, warm compresses and antibiotics are usually effective treatments. Therapy consists of close follow-up examinations or surgical excision of the involved ducts.

Gynaecomastia

Gynaecomastia, a transient, non-inflammatory enlargement of one or both breasts, is the most common breast problem in men (see Fig 51-2). The condition is usually benign and reversible. Gynaecomastia in itself is not an established risk factor for breast cancer. The most common cause of gynaecomastia is a disturbance of the normal ratio of active androgen to oestrogen in plasma or within the breast itself.

Gynaecomastia may also be a symptom of other problems. It is seen accompanying developmental abnormalities of the male reproductive organs. In addition, it may accompany organic diseases, including testicular tumours, cancer of the adrenal cortex, pituitary adenomas, hyperthyroidism and liver disease.16 Gynaecomastia may occur as a side effect of drug therapy, particularly with administration of oestrogens and androgens, digoxin, isoniazid, ranitidine and spironolactone. Heavy use of alcohol can also cause gynaecomastia.

PUBERTAL GYNAECOMASTIA

Pubertal gynaecomastia, which is caused by increased oestrogen production, is seen most often in boys aged between 13 and 17 years. It is usually limited, although occasionally the localised hyperplasia may measure 2–3 cm in size. Pubertal gynaecomastia is almost always self-limiting and disappears within 4–6 months of onset. Parents and the affected boy should be reassured that in almost all cases this is a normal physiological phenomenon that will disappear spontaneously and will require no treatment. Rarely, unilateral gynaecomastia in the young male may be marked and fail to regress. This is the only indication for surgical intervention.

SENESCENT GYNAECOMASTIA

Senescent gynaecomastia occurs in 40% of older men. A probable cause is the elevation in plasma oestrogen in older adult men due to the increased conversion of androgens to oestrogens in peripheral circulation. Although initially unilateral, the tender, firm, centrally located enlargement may become bilateral. When gynaecomastia is characterised by a discrete, circumscribed mass, it must be diagnosed to differentiate it from the rarer breast cancer in males. Senescent hyperplasia requires no treatment and generally regresses within 6–12 months.

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy among females in Australia and New Zealand and, following lung cancer, is the second most common cancer-related cause of female death.1,17 In Australia, the absolute number of new cases of breast cancer is tending to increase from year to year; however, the increase over the last 10 years is considered to be due to changes in the age and size of the population. Mortality rates are declining by an average of 2.2% per year.18 The incidence of breast cancer in the Australian Indigenous population is lower than in the general population, although mortality rates are the same as in the general population. This lower incidence may be related to protective factors such as having children at a younger age and having more pregnancies, while mortality rates may be related to the fact that Indigenous women are less likely to access screening mammography. In contrast in New Zealand, Māori women have a higher incidence of breast cancer than the general population and a 50% higher mortality rate from breast cancer than non-Māori females.19

Gerontological considerations: age-related breast changes

Loss of subcutaneous fat and structural support and involution of mammary glands often result in pendulous breasts in the postmenopausal woman. The nurse should encourage older women to wear a well-fitting bra. Adequate support can improve physical appearance and reduce pain in the back, shoulders and neck. It can also prevent intertrigo (dermatitis caused by friction between opposing surfaces of skin). Intertrigo should be treated topically with a zinc oxide preparation and the woman should be educated to keep the skin surfaces clean and dry to prevent recurrence. Persistent intertrigo can be treated with an anti-fungal preparation. Surgical lifting of sagging breasts is possible and may be desirable when reconstruction after a mastectomy is performed.

The decrease in glandular tissue in older women makes a breast mass easier to palpate. This decreased density is probably age-related and occurs even with women on hormone replacement therapy. Rib margins may be palpable in the older adult woman and can be confused with a mass. As a woman becomes more familiar with her own breasts and is reassured about her findings, the anxiety about this finding should decrease. Because the incidence of breast cancer increases with age, older women should be encouraged to have 2-yearly mammograms in line with screening guidelines, maintain BSA and report changes without delay to their healthcare provider. Regular CBE is advised if mammography is not being used.

Inflammatory breast cancer is initially treated with chemotherapy, targeted therapies, hormone therapies and radiation therapy. Surgery may be an option if the condition responds well to this neo-adjuvant therapy. Diagnosis and treatment of early breast cancer is now so successful that around 90% of patients diagnosed with a localised breast cancer will be alive in 5 years’ time. Conversely, only 20% of patients diagnosed with advanced-stage breast cancer, with metastases to distant sites, are likely to survive beyond 5 years.20

AETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

Although the aetiology of breast cancer is not yet fully understood, it is believed that breast cancer occurs as a consequence of a combination of individual factors and events, such as inherited genetic susceptibility, exposure to carcinogens, levels of various hormones within the body, the function of the body’s immune system and changes in the molecular structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in breast cells that may occur just by chance. Most of the recognised breast cancer risk factors relate to one or more of these individual factors and events.21 Environmental and lifestyle factors are considered to contribute to breast cancer risk. Some benign breast conditions—for example, atypical ductal hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)—are also associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Additional factors considered to be associated with a moderate to strongly increased risk of breast cancer are female sex, increasing age, affluence and family history.

Ninety-nine per cent of breast cancers occur in women. Increasing age is one of the strongest risk factors for breast cancer. The incidence of breast cancer in women under 25 years of age is very low and increases gradually until age 60. After age 60 the incidence increases dramatically. Positive family history is an important and well-established risk factor, especially if the involved member with breast cancer was premenopausal, had bilateral disease and is a first-degree relative (i.e. mother, sister, daughter). Having any first-degree relative with breast cancer increases a woman’s risk of breast cancer 1.5–3 times, depending on age. Initially, HRT was thought to have no effect or to decrease the incidence of breast cancer; however, the Million Women Study22 found that use of HRT does increase the risk of breast cancer (relative risk: 1.66). The effect was found to be substantially greater for oestrogen–progestogen combinations than for other types of HRT. The risk of breast cancer increased in association with the number of years of use. Ten years’ use of HRT was estimated to result in 5 additional breast cancer cases per 1000 women for those using oestrogen-only preparations, and 19 additional cases per 1000 women for those using progestogen–oestrogen combinations. Given that HRT protects against osteoporosis, each woman and her doctor must carefully weigh the relative risks of these problems.

Hormones are considered to play a part in breast cancer risk, with younger age at menarche, older age at menopause, use of oral contraception or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and level of circulating hormones considered to increase breast cancer risk.21

Personal lifestyle can have a modest influence on a woman’s breast cancer risk, with factors including the following contributing to increased risk: overweight and obesity; alcohol consumption; a personal history of other cancers including ovarian, colorectal, endocrine, thyroid and melanoma; and exposure to ionising radiation before the age of 20 years.21 In contrast, there is evidence that physical exercise can reduce the risk of breast cancer, as can some hormonal factors related to pregnancy.

Identification of risk factors indicates an increased need for careful clinical surveillance of the patient and participation in cancer screening measures. Women at high risk of breast cancer may be eligible for yearly mammograms. The National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre has an online tool to help women assess their risk for breast cancer (see Resources on p 1478).23

It is estimated that 5–10% of women with breast cancer carry germ-line mutations. Between 1 in 300 and 1 in 500 women in New Zealand and Australia may be carriers of clinically significant genetic mutations. Women who have genetic mutations have a 50–85% lifetime chance of developing breast cancer.24 The first genetic alteration to be identified was in the tumour suppressor gene, the BRCA1 gene. This gene is located on chromosome 17 and it inhibits tumour development when functioning normally. The BRCA2 gene, located on chromosome 13, is another tumour suppressor gene, and women with a mutation of this gene have a similar risk of breast cancer to those with a mutation of the BRCA1. The BRCA2 gene is also associated with an increased risk of male breast cancer. Many families affected by breast cancer show an excess of ovarian, colon, prostatic and other cancers attributable to the same inherited mutation. Genetic testing raises complex medical and ethical issues and should be offered with pre- and post-test counselling in conjunction with a specialist genetics service for breast cancer.24

HEALTH DISPARITIES

Incidence

• Approximately 5–10% of breast cancers are related to BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations.

• Women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations have a 50–85% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer.

• BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations are associated with early-onset breast cancer.

• BRCA2 mutations are associated with male breast cancer.

• Family history of both breast and ovarian cancer increases the risk of having a BRCA gene mutation.

In women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, prophylactic bilateral oophorectomy can decrease the risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer.25 In deciding whether to undergo this surgical procedure, women should take into account how long they wish to maintain fertility. In addition, they should receive counselling about the risks and benefits of prophylactic oophorectomy.

A woman who has a high risk of developing breast cancer, related to factors such as family history and prior tissue biopsies, may choose to undergo prophylactic bilateral mastectomy. This surgery may reduce a women’s breast cancer risk by 90%.26

Predisposing risk factors for breast cancer in men include states of hyper-oestrogenism, a family history of breast cancer including known genetic abnormalities and radiation exposure. A thorough examination of the male breast should be a routine part of a physical examination.

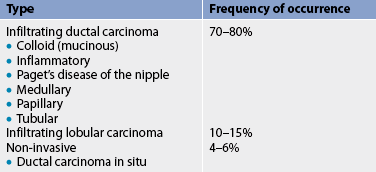

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The main components of the breast are lobules (milk-producing glands) and ducts (milk passages that connect the lobules and the nipple). In general, breast cancer arises from the epithelial lining of the ducts (ductal carcinoma) or from the epithelium of the lobules (lobular carcinoma). Breast cancers may be invasive or in situ. Most breast cancers arise from the ducts and are invasive. Various types of breast cancer have been identified based on histological characteristics, growth patterns and genetic profiles (see Tables 51-4 and 51-5). The different morphologies and molecular profiles determine the clinical behaviour of the disease and response to therapy.

TABLE 51-4 Types of breast cancer by genetic profile

| Type | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Luminal A | ER/PR positive, HER2 negative, lower grade |

| Luminal B | ER/PR positive, HER2 positive, higher grade |

| HER2 | HER2 positive, ER/PR negative |

| Basal-like | ER/PR/HER2 negative, CK6/7 negative |

| Normal-like | Clinical significance of normal-like breast cancers is yet to be determined |

CK, cytokeratin; ER, oestrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; PR, progesterone receptor.

Research, 2009. Available at www.uscap.org/site∼/98th/pdf/companion03h03.pdf, accessed 10 October 2010.

Source: Reis-Fihlo J. Triple negative breast and basal-like breast cancer: one disease or many? Implications for surgical pathologists. Institute of Cancer

The natural history of breast cancer varies considerably from patient to patient. Cancer growth rate can range from slow to rapid. Factors that affect cancer prognosis are tumour size, axillary node involvement (the more nodes involved, the poorer the prognosis), tumour differentiation, DNA content (characteristics of malignant cells), and oestrogen, progesterone and HER2 receptor status.

Non-invasive breast cancer

The increased use of screening mammography has led to more women being diagnosed with non-invasive breast cancer, including ductal carcinoma in situ and lobular carcinoma in situ. DCIS tends to be unilateral and has the potential to progress to invasive breast cancer if left untreated. Therefore, DCIS is currently treated with a combination of surgery and radiation therapy as for invasive cancer, depending on individual circumstances. Many cases of DCIS do not progress; however, it is not possible to predict which cases will develop into breast cancer. It is hypothesised that high-grade DCIS is more likely to progress to invasive cancer than lower grade DCIS.27 Women with a diagnosis of DCIS are at higher risk of developing invasive breast cancer in their lifetime. The use of selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SORMs) and aromatase inhibitors in the 1prevention of breast cancer in women previously diagnosed with DCIS is currently under investigation.28

LCIS is a proliferation of abnormal cells in the breast lobules and is considered to be a marker of increased breast cancer risk. Most women with LCIS do not develop invasive breast cancer. No treatment is required for LCIS, as long as there are no other abnormal findings. Women who have been diagnosed with LCIS need to be breast self-aware and have regular screening mammograms and CBEs by their healthcare practitioner.

Although the management of these two disorders can be controversial, patients with DCIS and LCIS should discuss all treatment options with their doctor or nurse practitioner, including local excision, mastectomy with breast reconstruction, breast-conserving treatment (lumpectomy), radiation therapy and/or SORMs.

Paget’s disease

Paget’s disease of the nipple is a breast malignancy characterised by a persistent lesion of the nipple and areola with or without a palpable mass.29 Itching, burning, bloody nipple discharge with superficial erosion and ulceration may be present. Diagnosis of Paget’s disease of the nipple is confirmed by pathological examination of the erosion. Nipple changes are often misdiagnosed as an infection or dermatitis, which can lead to treatment delays. The treatment of Paget’s disease of the nipple has traditionally involved simple or modified radical mastectomy; however, there is some evidence to support breast conserving therapy with radiation therapy as a treatment choice. Prognosis is good when the cancer remains in the nipple only. Nursing care for the patient with Paget’s disease of the nipple is the same as the care for a patient with breast cancer. (This is different from Paget’s disease of the bone, which is discussed in Ch 63.)

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Breast cancer may be detected as an abnormality in the breast during palpation by the woman or her healthcare practitioner, or via mammogram or ultrasound. It occurs most often in the upper, outer quadrant of the breast because that is the location of most of the glandular tissue (see Fig 51-3). The rate at which the lesion grows varies considerably. Slow-growing lesions are often associated with a lower mortality rate.

If palpable, breast cancer is characteristically hard, irregularly shaped, poorly delineated, non-mobile and non-tender, although more subtle signs such as a thickening may be present. A small percentage of breast cancers cause nipple discharge. The discharge is usually unilateral and may be clear or bloody. Nipple retraction may occur. In large cancers, infiltration, induration and dimpling (pulling in) of the overlying skin may also be noted.

Inflammatory breast cancer is a rare but aggressive and fast-growing variant of breast cancer that presents clinically with erythema, warmth and oedema of the breast. The skin has a thickened appearance that is described as ‘peau d’orange’ or resembling orange peel. The inflammatory changes, which can be mistaken for infection, are caused by cancer blocking lymph channels. Metastases occur widely and early.

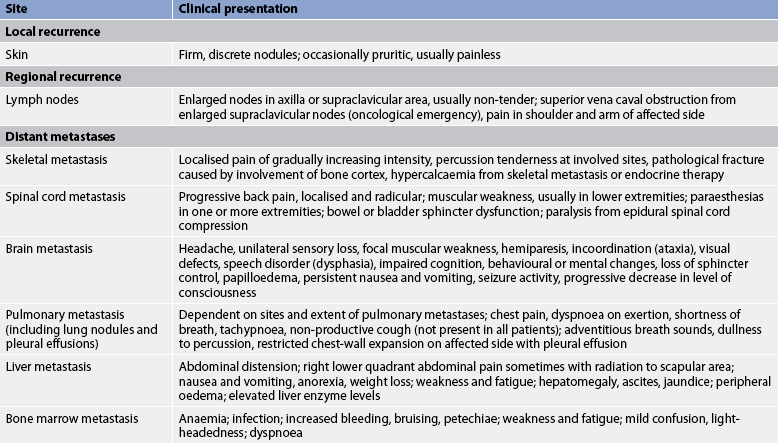

COMPLICATIONS

The main physical complication of breast cancer is recurrence (see Table 51-6). Recurrence may be local or regional (skin or soft tissue near the mastectomy site, axillary or internal mammary lymph nodes) or distant, most commonly involving the bone, lungs, brain and liver.

Widely disseminated or metastatic disease involves the growth of colonies of cancerous breast cells in parts of the body distant from the breast. Metastases primarily occur via the lymphatic vessels, principally those of the axilla. However, the cancer can spread to other parts of the body without invading the axillary nodes, even when the primary breast tumour is small. Even in node-negative breast cancer, there is a possibility of distant metastasis. Computed tomography and nuclear medicine bone scans are used to detect metastatic disease.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

In addition to studies used to diagnose breast cancer (see p 1455), other tests are useful in predicting the risk of recurrence or metastatic breast disease. Prognostic values include axillary lymph node status, tumour size, DNA content analysis (ploidy status), oestrogen and progesterone receptor status, HER2/neu receptor status and cell proliferative indices.

Axillary lymph node involvement is one of the most important prognostic factors in early-stage breast cancer.30 The more nodes involved, the greater the risk of local or distant recurrence. Patients with four or more positive nodes have the greatest risk of recurrence.

Studies are examining improved methods to assess tumour growth in the regional lymph nodes. This information is important when considering possible adjuvant systemic therapy. Tumour size is an important prognostic variable: the larger the tumour, the poorer the prognosis. Ploidy status correlates with tumour aggressiveness. Diploid tumours have been shown to have a significantly lower risk of recurrence than aneuploid tumours. The wide variety of histological types of breast cancer explains the heterogeneity of the disease. In general, the more well differentiated the tumour, the less aggressive it is. Poorly differentiated tumours appear morphologically disorganised and are more aggressive.

A diagnostic test performed on the surgical specimen, useful for both treatment decisions and prediction of prognosis, is oestrogen and progesterone receptor status. Receptor-positive tumours: (1) commonly show histological evidence of being well differentiated; (2) frequently have diploid (more normal) DNA content and low proliferative indices; (3) have a lower chance of recurrence; and (4) are frequently responsive to hormonal therapy. Receptor-negative tumours: (1) are often poorly differentiated histologically; (2) have a high incidence of aneuploidy (abnormally high or low DNA content) and higher proliferative indices; (3) frequently recur; and (4) are usually unresponsive to hormonal therapy.

Another prognostic indicator is the over-expression of the protein HER2/neu (also called c-erb-B2 or neu). Amplification and over-expression of this protein has been associated with a greater risk of recurrence and a poorer prognosis in breast cancer.31 The presence of this genetic marker assists in the selection and sequencing of chemotherapy and in predicting patient response to treatment.

Around 90% of cancers in women with BRCA1 germ-line mutations will have triple-negative cancer. This subset accounts for around 15% of all breast cancers and may be associated with poorer prognosis.31,32

Gene expression profiling is currently available to identify subgroups of node negative, oestrogen-receptor positive patients who will benefit from chemotherapy (Oncotype Dx™) and determine potential for recurrence (Mammoprint™).

Cell-proliferative indices indirectly measure the rate of tumour cell proliferation. The percentage of tumour cells in the S phase of the cell cycle is another important prognostic indicator. Patients with cells that have high S-phase fractions have a higher risk of recurrence and earlier cancer death.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Multidisciplinary care is considered best practice in the management of breast cancer. A wide range of treatment options is available for both the patient and care providers to consider, highlighting the importance of a multidisciplinary team approach to making critical decisions about what treatment to select (see Box 51-1 and Table 51-7). The aim of breast cancer surgery is to eradicate the primary tumour to achieve disease control. Modified radical mastectomy and breast conserving surgery achieve comparable outcomes in disease control.30

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

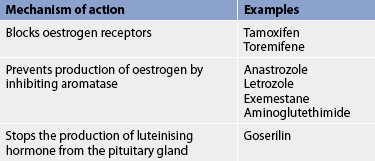

Hormonal therapy (see Table 51-7)

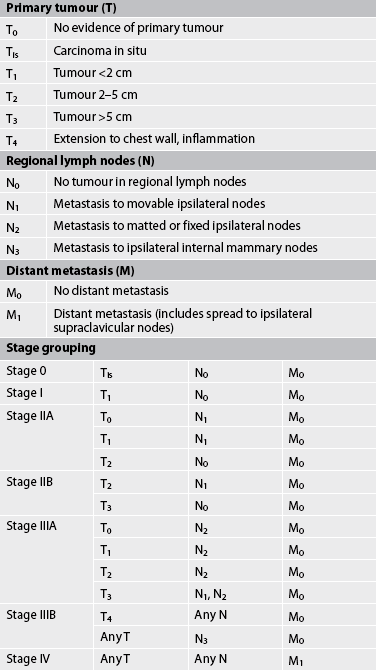

The most widely accepted staging method for breast cancer is the TNM system (see Table 51-8).34 This system uses tumour size (T), nodal involvement (N) and the presence of metastasis (M) to determine the stage of disease. For example, in situ cancers are classified Tis. The stages range from I to IV, with stage I being very small tumours (<2 cm) with no lymph node involvement and no metastasis. Further classification within these stages depends on the size of the tumour and the number of lymph nodes involved. Stage IV indicates the presence of metastatic spread, regardless of tumour size or lymph node involvement. These factors also enter into the staging of breast cancer. The therapeutic regimen is dictated by the clinical stage classification of the cancer and individual patient characteristics. (Side effects and appropriate nursing management of general treatment modalities for cancer are discussed in Ch 15.)

In spite of the advent of new prognostic indicators, such as flow-cytometric determination of DNA content and analysis of cell-cycle phases, the single most powerful prognostic factor related to local recurrence or metastasis after primary therapy is still the presence or absence of malignant cells in axillary lymph nodes.

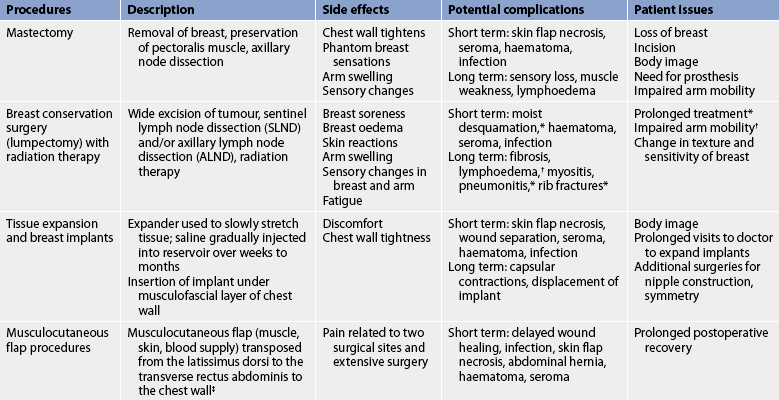

Surgical therapy

Breast conservation surgery with radiation therapy and modified radical mastectomy with or without reconstruction are currently the most common options for resectable breast cancer. Most women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer (tumours < 3cm) are candidates for either treatment choice. The overall survival rate with lumpectomy and radiation is about the same as that with modified radical mastectomy.27

Axillary lymph node dissection

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is the traditional method of examining the lymph nodes. Examination of nodes provides the most powerful prognostic data currently available and helps determine systemic treatment (chemotherapy or hormone therapy, or both). For early breast cancer, axillary lymph node dissection has always involved the removal of level 1 and level 2 lymph nodes, with 10–15 lymph nodes commonly found in the block dissection. However, this technique may not be necessary or appropriate for some women with invasive breast cancers <3 cm in size and with no clinically palpable nodes in the axilla.35

Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) are surgical techniques that help the surgeon to identify the lymph node(s) that drain first from the tumour site (sentinel node).35 A radioisotope and/or blue dye is injected into the affected breast and, intraoperatively, it is determined in which node(s) the radioisotope and/or blue dye is located. A local incision is made and the surgeon dissects the blue-stained sentinel node and/or radioactive lymph node. The node is subsequently analysed histologically. Assessment of this node can be used to determine the presence of macro- or micrometastases in the lymph node. SLND has been associated with lower morbidity rates and greater accuracy compared with complete axillary node dissection.29

The presence of malignant cells in a sentinel node is an indication for axillary dissection, and randomised controlled trials are currently in progress to investigate how best to treat patients with micrometastases in sentinel nodes.

Lymphoedema (accumulation of lymph in soft tissue; see Fig 51-4) can occur as a result of the excision or radiation of lymph nodes.30,35 When the axillary nodes cannot return lymph fluid to the central circulation, the fluid accumulates in the arm, causing obstructive pressure on the veins and venous return. The patient may experience heaviness, pain, impaired motor function in the arm, swelling and paraesthesia of the fingers as a result of lymphoedema. Cellulitis and progressive fibrosis can result from lymphoedema.

Although lymphoedema is not always preventable, it can be controlled somewhat after surgery or radiation. In the postoperative phase, the patient should be positioned so as to minimise compression of the affected limb. The nurse has an important role in providing education about ways to minimise the risk of lymphoedema, including skin care, maintaining physical activity and avoiding constriction of the limb. Nurses should be aware to always avoid taking blood pressure or performing venipuncture on the affected arm of any patient who has undergone an axillary procedure. Frequent and sustained elevation of the arm, performing hand and arm exercises daily and avoiding clothing that constricts the arm are all helpful in reducing lymphoedema.36 Patients with lymphoedema that is not managed by these simple measures should be referred to a physiotherapist or occupational therapist for management.

Breast conservation surgery

Breast conservation surgery (termed lumpectomy, wide local excision or partial mastectomy) involves the removal of the entire tumour along with a margin of normal tissue. Following surgery, radiation therapy is delivered to the entire breast, ending with a boost to the tumour bed. In many instances, chemotherapy may be indicated and given before radiation therapy. Contraindications to breast conservation surgery include breast size too small to yield an acceptable cosmetic result, masses and calcifications that are multifocal (within the same breast quadrant), masses that are multicentric (in more than one quadrant) or diffuse calcifications in more than one quadrant and previous chest radiotherapy. Access to and costs associated with radiotherapy are important considerations in patient preferences for surgery. For example, patients from country areas may need to stay away from home for long periods while having treatment.

One of the main advantages of combined breast conservation surgery and radiation is that it preserves the breast, including the nipple. The goal of the combined surgery and radiation is to maximise the benefits of both cancer treatment and cosmetic outcome while minimising the risks. Disadvantages include the potential to need a second operation to achieve clear surgical margins, and the possible side effects of radiation. Table 51-9 describes treatment options, side effects, complications and patient issues related to the most common surgical procedures currently used to treat breast cancer.

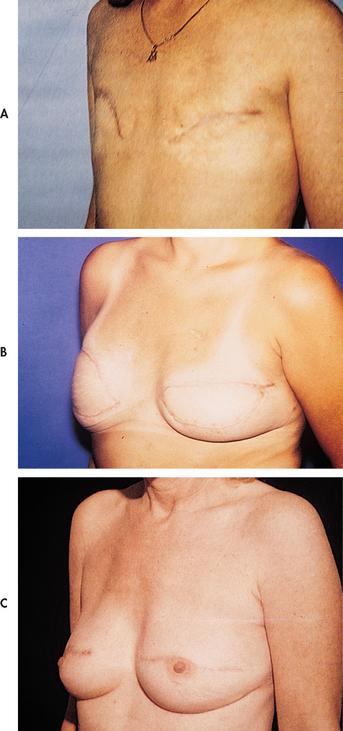

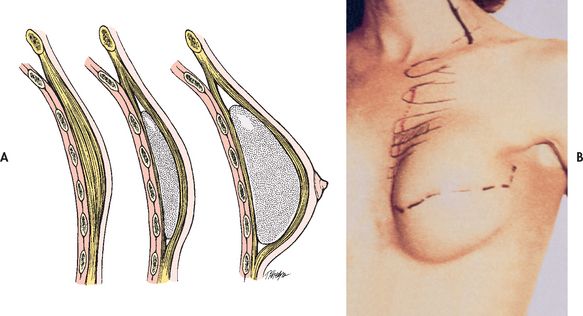

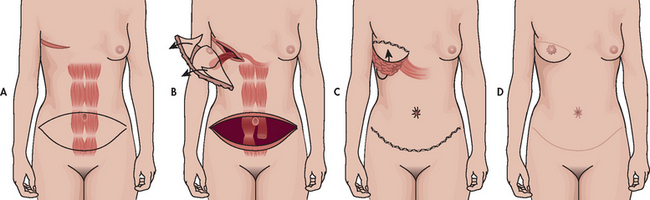

Mastectomy

A mastectomy includes removal of the breast and axillary lymph nodes but preserves the pectoralis major muscle (modified radical mastectomy). This surgery would be selected over breast conservation therapy if the tumour is too large to excise with good margins and attain a reasonable cosmetic result, or if the patient does not wish to undergo radiation therapy. Some patients may select this surgical procedure over lumpectomy when presented with the choice of either procedure.

When a mastectomy is performed, the patient has the option of breast reconstruction. If the patient chooses to have reconstructive surgery, it can be performed immediately following the mastectomy or it can be delayed until postoperative recovery and adjuvant therapy is complete.

Follow-up care

After surgery, the woman must be followed up for the rest of her life at regular intervals. Most women have clinical examinations at a minimum every 3–6 months for 2 years and then annually thereafter. In addition, the woman must continue to look for any changes to both breasts or the remaining breast and the mastectomy site. The most common site of recurrence of breast cancer is at the surgical site. The woman should also have yearly mammography of the breast or breast tissue. The follow-up is also an opportunity to monitor ongoing therapy, psychosocial wellbeing and quality of life.

Postmastectomy pain syndrome

Postmastectomy pain syndrome can occur in patients following a mastectomy or ALND. Common symptoms include chest and upper arm pain, tingling down the arm, numbness, shooting or pricking pain and unbearable itching that persist beyond the normal 3-month healing time. The pain syndrome is caused by a number of factors, including injury to nerves and tissue as a result of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy or secondary neuroma development. The most common theory for its onset is injury to intercostobrachial nerves, which are sensory nerves that exit the chest wall muscles and provide sensation to the shoulders and upper arms.

Treatments include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, topical lignocaine patches, EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics: lignocaine and prilocaine) and antiepileptics drugs (e.g. gabapentin). Other possible treatment modalities include guided imagery training, biofeedback, physiotherapy to prevent ‘frozen shoulder’ syndrome as a result of inadequate movement and psychological counselling with a person trained in the management of chronic pain syndromes.

Adjuvant therapy

The decision to recommend adjuvant (additional) therapy after surgery depends on the stage of the disease (the number of involved nodes and the tumour size), menopausal status and age, cell characteristics, the presence or absence of oestrogen and progesterone receptors and HER2 amplification, and other pre-existing health problems that can complicate treatment. Adjuvant therapies include radiation therapy after breast conservation surgery and systemic therapies, such as chemotherapy and hormonal therapy.30

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy may be used for breast cancer: (1) as an adjuvant to surgery to prevent local recurrence or as the primary treatment to destroy the tumour; (2) to shrink a large tumour to operable size; and (3) as the palliative treatment for pain caused by local recurrence and metastases. Breast conservation surgery for invasive cancer or high-grade DCIS is almost always followed by a recommendation for radiation.

Adjuvant radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is usually performed after local excision of the breast mass. The breast, and in some cases the regional lymph nodes, is radiated daily over the course of approximately 5–6 weeks, although shorter courses of radiation are currently under investigation. An external beam of radiation is used to deliver a total dose of 50 Gy. A ‘boost’ treatment to the full breast may also be given, either before or after therapy has been completed. The boost is a dose of radiation delivered to the area in which the original tumour was located. It can be given by external beam and usually adds 10 treatments to the total number given. Fatigue, skin changes and breast oedema may be temporary side effects of external beam radiation therapy. Radiation of the axilla is also effective in decreasing the incidence of axillary recurrence, although it increases the incidence of lymphoedema. Clinical trials are currently in progress to assess the equivalence of single-fraction intraoperative external beam radiotherapy to adjuvant external beam radiotherapy.

The decision to use radiation therapy after mastectomy is based on the probability of the presence of local residual cancer cells (related to the size of the cancer and the number of involved lymph nodes). Irradiating the area is aimed at local disease control and will not prevent distant metastasis. The site of radiation therapy (lymph nodes or chest wall, or both) depends on the degree of possible spread of the cancer.

Primary radiation therapy

Although an uncommon treatment mode, preoperative radiation therapy can be used to reduce the size of a large tumour mass to operable proportions by destroying the cancer cells. Additionally, because the malignant cells are partially or completely destroyed, the rate of local recurrence decreases.

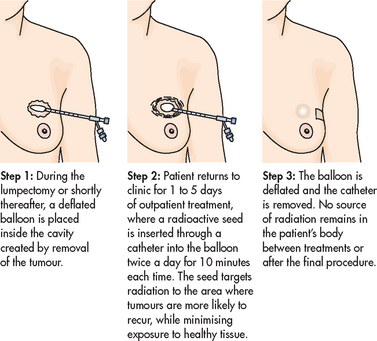

High-dose brachytherapy

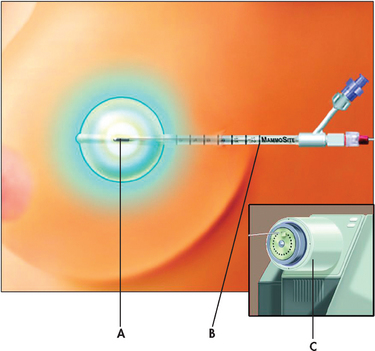

High-dose brachytherapy is a new procedure that is an alternative to traditional radiation treatment for early-stage breast cancer. The technique uses a balloon catheter to insert radioactive seeds into the breast after the tumour is removed (see Figs 51-5 and 51-6). The seeds deliver a concentrated dose of radiation directly to the site where the cancer is most likely to occur. Traditional radiation treatments can take 5–6 weeks. In contrast, high-dose brachytherapy may require only 5 days.

Figure 51-6 High-dose brachytherapy for breast cancer. The MammoSite system involves the insertion of a single balloon catheter (B) at the time of the lumpectomy or shortly thereafter into the tumour resection cavity—the space that is left after the surgeon removes the tumour. A tiny radioactive seed (A) is inserted into the balloon, which is connected to a machine called an afterloader (C), and delivers the radiation therapy.

Palliative radiation therapy

In addition to reducing the primary tumour mass with a resultant decrease in pain or bleeding, radiation therapy is also used to stabilise symptomatic metastatic lesions in such sites as bone, soft-tissue organs, brain and chest. Radiation therapy relieves pain and is often successful in controlling recurrent or metastatic disease for long periods.

Systemic therapy

The goal of systemic therapy is to destroy tumour cells that may have spread undetected to distant sites.49 Systemic therapy as an adjuvant to primary local treatment, in the absence of demonstrable metastases, can decrease the rate of recurrence and increase the length of survival.27 Because of the high risk of recurrent disease, nearly all women with evidence of node involvement, particularly those who are hormone-receptor negative, will have some type of systemic therapy. Certain women, particularly those who are premenopausal, are known to be at higher risk of recurrent or metastatic disease. These women are often recommended for systemic therapy even when no evidence of node involvement is found. Weighing the different risk factors (nodal status, tumour size, tumour grade, and oestrogen, progesterone and HER2 receptor status) to determine the need for adjuvant therapy in a node-negative patient is complex, and multidisciplinary team discussion often precedes a patient referral to a medical oncologist to discuss systemic treatment options.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy refers to the use of cytotoxic drugs to destroy cancer cells. The greatest benefits from chemotherapy have been achieved among premenopausal women with node findings that are positive for malignancy.

In some instances chemotherapy is used preoperatively. Preoperative or neo-adjuvant chemotherapy can decrease the size of the primary tumour, possibly permitting less extensive surgery. Also, it has been shown that preoperative chemotherapy suppresses tumour growth and prolongs survival.

Breast cancer is one of the solid tumours most responsive to chemotherapy. The use of combinations of drugs has been proven superior to the use of a single drug. The benefit of combination treatment results from the use of drugs that have different actions on cell growth and division. The more common combination-therapy protocols are cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin, referred to as AC, with or without the addition of a taxane (paclitaxel or docetaxel); or cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil and epirubicin or doxorubicin, referred to as FEC or FAC, respectively. Taxane-containing regimens are commonly used in women with a high risk of recurrence; the taxanes, including an albumin-bound form (abraxane) and capecitabine, are also used in women whose metastatic breast cancer has not responded to standard chemotherapy.37 Vinorelbine, a relatively new chemotherapeutic drug for treating metastatic breast cancer, is well tolerated with fewer and milder side effects than other chemotherapy drugs.

Because healthy cells are also affected by chemotherapy, a variety of side effects accompany this treatment modality. The incidence and severity of predictable and commonly observed side effects will be influenced by the specific drug combination, drug schedule and dose intensity of the drug or drugs. Usually body organs with rapidly growing cells are the most strongly affected. The most common side effects involve the gastrointestinal tract, bone marrow and hair follicles, resulting in nausea, anorexia, bone marrow suppression and subsequent fatigue, and alopecia (hair loss). Doxorubicin has been associated with cardiotoxicity and patients should be monitored for signs of heart failure. Additional side effects of taxanes include peripheral neuropathy and myalgia/arthralgias.

Cognitive changes during and after chemotherapy, often termed chemo-brain, have been reported in as many as 75% of patients. The greatest impacts are on information and processing speed, attention, memory and executive function. The mechanisms are poorly understood and there is ongoing research into why this occurs and how best to assist patients to manage the changes.38

Hormonal therapy

Oestrogen can promote the growth of breast cancer cells if the cells are oestrogen-receptor positive. Hormonal therapy removes or blocks the source of oestrogen, thus promoting tumour regression. Hormonal therapy can: (1) block or destroy the oestrogen receptors; or (2) suppress oestrogen synthesis by inhibiting aromatase, an enzyme needed for endogenous oestrogen synthesis (see Table 51-7).36 Oestrogen deprivation can be achieved through surgery, radiation therapy or drug therapy. Hormonal therapy is widely used to treat early breast cancer (as an adjuvant to primary therapy) and recurrent or metastatic cancer.

Two advances have increased the use of hormone therapy in breast cancer. First, hormone receptor assays, which are reliable diagnostic tests, have been developed to identify women who are likely to respond to hormone therapy.39 Both oestrogen and progesterone receptor status of the tumour can be determined. The importance of these assays is their ability to predict whether hormonal therapy is a treatment option for women with breast cancer, either at the time of initial therapy or if the cancer recurs. Second, drugs have been developed that can inactivate the hormone-secreting glands as effectively as surgery or radiation. Premenopausal and perimenopausal women are more likely to have tumours that are not hormone dependent, whereas women who are postmenopausal are more likely to have hormone-dependent tumours. Chances of tumour regression are significantly greater in women whose tumours contain oestrogen and progesterone receptors.

Tamoxifen is a SORM that is effective in improving recurrence and mortality risk in early-stage disease, palliation in advanced breast cancer and prevention for high-risk individuals.38 Tamoxifen blocks the oestrogen receptor sites of malignant cells and thus inhibits the growth-stimulating effects of oestrogen. Side effects are minimal but include hot flushes, nausea, vomiting, vaginal discharge and other effects commonly associated with decreased oestrogen. It also increases the risk of blood clots, cataracts and endometrial cancer in postmenopausal women.38,40

Aromatase-inhibitor drugs, which interfere with the enzyme that synthesises endogenous oestrogen, have traditionally been used in the treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women with disease progression. These drugs include anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane and aminoglutethimide. Following the results of large randomised trials, aromatase inhibitors are now available for the treatment of postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer, showing a survival advantage over tamoxifen, with less severe side effects. Aromatase inhibitors do, however, result in more risk of osteoporosis, so that for some women, tamoxifen may still be the drug of choice. Because of their mode of action, aromatase inhibitors are contraindicated for premenopausal women.36

Toremifene, an antioestrogen agent similar to tamoxifen, is also indicated as a first-line treatment for metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor positive or oestrogen-receptor unknown tumours.

Raloxifene, a drug used to prevent bone loss, may reduce the risk of breast cancer without stimulating endometrial growth. Raloxifene acts as an oestrogen antagonist at the hormone-sensitive tissues of breast cancer and bone. (Raloxifene is discussed in the section on osteoporosis in Ch 63.)

Goserelin is a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue that in premenopausal women may be an acceptable alternative to ovarian ablation. It stops the production of luteinising hormone from the pituitary gland, suppressing the ovaries and leading to a reduction in oestrogen levels.

Additional drugs used to suppress hormone-dependent breast tumours include megestrol and fluoxymesterone. Less common hormone-deprivation strategies include bilateral oophorectomy, adrenalectomy and hypophysectomy.

Biological therapy

The use of biological therapy represents an attempt to stimulate the body’s natural defences to recognise and attack cancer cells. Trastuzumab is a monoclonal antibody to HER2/neu, an antigen that often appears on the surface of breast cancer cells. By binding to HER2 protein receptors, trastuzumab interrupts the growth signal, thereby slowing the growth and spread of breast cancer cells. It is used alone or in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy to treat patients with breast cancer whose tumours overexpress the HER2 gene in both adjuvant and metastatic settings.33 Regular monitoring for signs of ventricular dysfunction and heart failure are imperative prior to and during trastuzumab therapy. The drug should be used with caution in women with pre-existing heart disease. Lapatinib may be used in combination with capecitabine for HER2-positive patients with metastatic cancer when the disease has become resistant to trastuzumab.

Biological therapy is an exciting area of research in anti-cancer treatment and it is likely that more targeted therapies will become available in the future.

Bone marrow and stem cell transplantation

Autologous bone marrow or peripheral stem cell transplantation combined with high-dose chemotherapy has been used in the past to treat patients with advanced metastatic breast cancer. However, this form of treatment for women with metastatic breast cancer has proven to be ineffective and is no longer used in Australia.

Future directions in care

Breast cancer is the subject of a wide variety of clinical trials on prevention, diagnosis and treatment, as well as quality-of-life issues for patients during and after treatment. Outcomes of clinical trials will significantly impact on how breast cancer is managed in the future. It is the nurse’s responsibility to be aware of developments that impact on clinical practice. For example, clinical trials are currently examining targeted therapies for triple-negative cancers, antiangiogenesis factors, new chemotherapy agents, delivery methods and duration of radiotherapy, and optimal management of the axilla for node-positive women. Results of recent clinical trials and information about current clinical trials can be found on the US National Cancer Institute’s website (see Resources on p 1478); in addition, outcomes of clinical trials are presented at international clinical oncology conferences, with highlights published in peer-reviewed journals.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: BREAST CANCER

NURSING MANAGEMENT: BREAST CANCER

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Many factors need to be considered when the nurse is assessing a patient with a breast problem. The history of the breast disorder assists in establishing the diagnosis. The presence of nipple discharge, pain, the rate of growth of the lump, breast asymmetry and correlation with the menstrual cycle should all be investigated.

The size and location of the lump or lumps should be carefully documented and the physical characteristics of the lesion—such as consistency, mobility and shape—should be assessed. If nipple discharge is present, the colour and consistency should be noted, as well as whether it occurs from one or both breasts.

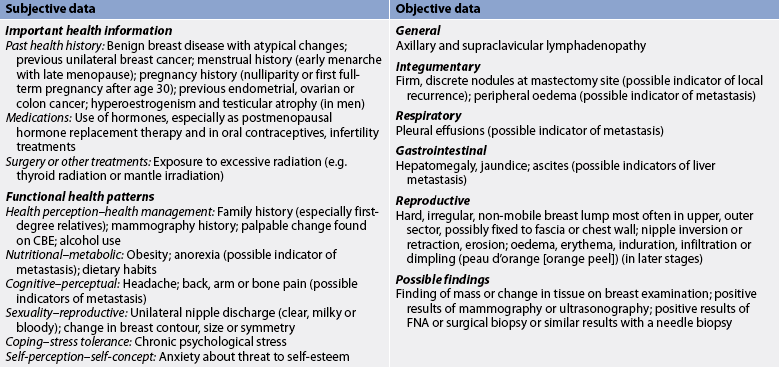

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from an individual suspected of having or diagnosed as having breast cancer are presented in Table 51-10.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses related to the care of the patient diagnosed with breast cancer vary. Following diagnosis and before a treatment plan has been selected, the following diagnoses would apply:

• decisional conflict related to lack of knowledge about treatment options and their effects

• fear related to diagnosis of breast cancer

• disturbed body image related to anticipated physical and emotional effects of treatment modalities.

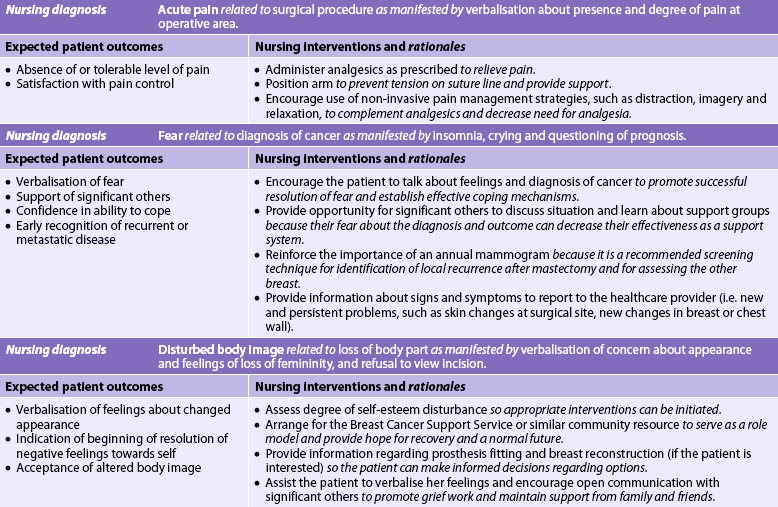

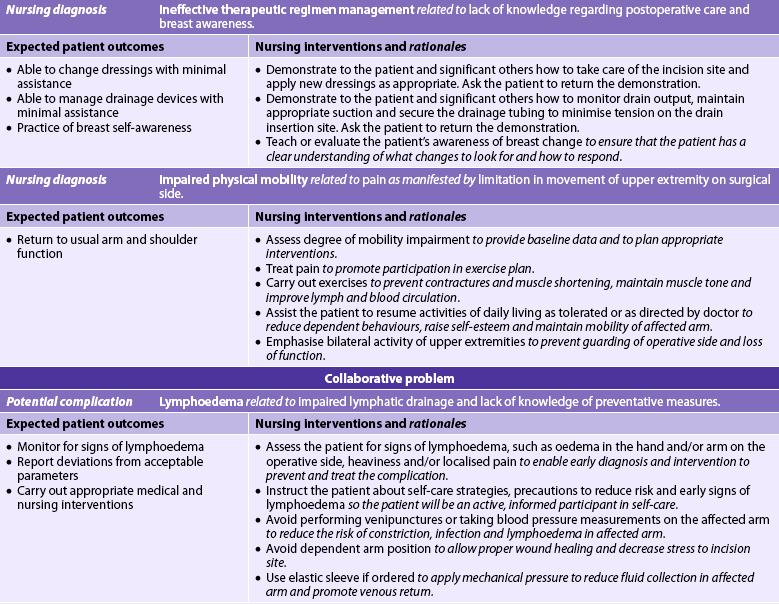

If a mastectomy is planned, the nursing diagnoses may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 51-1.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with breast cancer will: (1) actively participate in the decision-making process related to treatment options; (2) fully comply with the therapeutic plan; (3) manage the side effects of adjuvant therapy; and (4) be satisfied with the support provided by significant others and healthcare providers.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

The time between the diagnosis of breast cancer and the selection of a treatment plan is a difficult period for the woman and her family. Although the primary care provider will have discussed treatment options, the woman may rely on the nurse to clarify and expand on these options. During this time, the woman may be very self-focused, verbalising her conflict and indecision frequently.41 Appropriate nursing interventions during this period include exploring the woman’s usual decision-making patterns, helping her to accurately evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of the options, providing information relevant to the decision and supporting the patient once the decision is made.

During this period the woman may exhibit signs of distress or tension, such as tachycardia, increased muscle tension, sleep disturbances and restlessness, whenever she focuses on the decision to be made. The nurse should assess the woman’s body language and motor activity and affect during periods of high stress and indecision so that appropriate interventions can be carried out.

Regardless of the surgery planned, the patient must be provided with evidence-based information to ensure informed consent. Some patients seek extensive, detailed information, whereas others avoid information.42 Sensitivity to the individual’s need for information is essential. Teaching in the preoperative phase includes instruction in turning, coughing and deep breathing; a review of postoperative exercises; a pain management plan; and an explanation of the recovery period from the time of surgery until discharge.

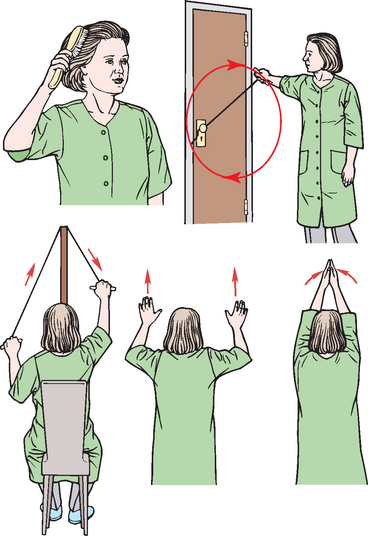

The woman who has breast conservation surgery usually has an uneventful postoperative course with only a moderate amount of pain. If ALND has occurred or if the patient has had a modified radical mastectomy, specific interventions will be needed. Restoring arm function on the affected side after mastectomy and ALND is one of the most important goals of nursing activities. The woman should be placed in a semi-Fowler position with the arm on the affected side elevated on a pillow. Flexing and extending the fingers should begin in the recovery room with progressive increases in activity encouraged. (Information pertaining to arm exercises and care apply to women who have had an ALND, lumpectomy or total mastectomy.) Postoperative arm and shoulder exercises are instituted gradually at the surgeon’s direction (see Fig 51-7). These exercises are designed to prevent contractures and muscle shortening, maintain muscle tone and improve lymph and blood circulation. The difficulty and pain encountered by the woman in performing the previously simple tasks included in the exercise program may cause frustration and depression. The goal of all exercise is a gradual return to full range of motion within 4–6 weeks.

Figure 51-7 Postoperative exercises for a patient with a mastectomy or lumpectomy with axillary lymph node dissection.

Postoperative discomfort can be minimised by administering analgesics about 30 minutes before initiating exercises. When showering is appropriate, the flow of warm water over the involved shoulder often has a soothing effect and reduces joint stiffness. Whenever possible, the same nurse should work with the woman so that progress can be monitored and problems identified.

Measures to prevent or minimise lymphoedema after ALND and sentinel node biopsy (SNB) must be used by the nurse and taught to the patient. The principles of care include maintaining skin integrity and optimising circulation. The patient must understand that the risk of developing lymphoedema remains for the remainder of her life.36 Blood pressure readings, venipunctures and injections should not be carried out on the affected arm, and elastic bandages should not be used in the early postoperative period because they inhibit collateral lymph drainage. The patient must be instructed to protect the arm on the operative side from even minor trauma, such as insect bites or sunburn. If trauma to the arm occurs, the area should be washed thoroughly with soap and water. A topical antibiotic ointment and a bandage or other sterile dressing should be applied. The surgeon must be advised of the trauma and the site of injury must be observed closely for evidence of inflammation and infection.

Management of lymphoedema includes treating any underlying injury or infection. Therapies involve intensive treatments undertaken by trained therapists and maintenance therapies performed by the patient. Intensive therapies include complex physical therapy (CPT), manual lymphatic drainage with or without compression and the use of laser therapy or pneumatic pumps.43 Massage takes the fluids across lymphatic watersheds towards functioning lymph nodes. Patients can be taught to perform their own massage to use in conjunction with exercise and limb compression. Limb compression is achieved through bandaging or the use of a fitted elastic pressure-gradient sleeve during waking hours to maintain maximum volume reduction. Elevation of the arm so that it is level with the heart and isometric exercises may be recommended to reduce fluid volume in the arm. Patients may be advised to wear a compression garment as a preventative measure during air travel.

Psychological care

Psychological care

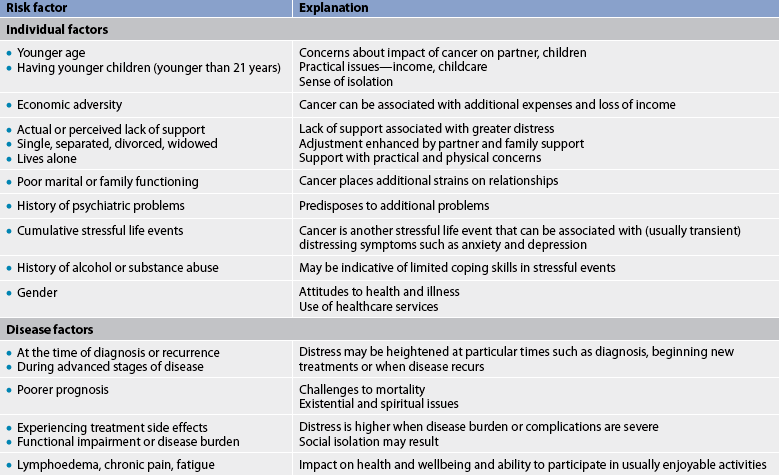

In all interactions with the patient with breast cancer, the nurse must keep in mind the extensive psychological impact of the disease. A range of practical, psychological and emotional challenges may be experienced as the patient adjusts to the diagnosis and treatment. All aspects of care must include sensitivity to the patient’s efforts to cope with a life-threatening disease and the impact that has on the patient’s role and family functioning, employment and financial status.42 An open relationship in which fears and feelings can be expressed is essential. The nurse can help meet the patient’s psychological needs by doing the following:

1. promoting open communication of thoughts and feelings between the patient and her family and the healthcare team